Abstract

The paper looks at Democratic Innovations in the process of amending subnational constitutional documents. Through qualitative approach, it focuses on two case studies: those of the Italian Provinces of Bolzano and Trento. Between 2015 and 2017 both Provinces conducted two parallel innovative democratic procedures with the aim of reforming the basic law of the Region (the Statute of Autonomy) in a deliberative fashion. The paper intends to analyze the procedures, identify the internal and external factors that had either negative or positive impacts on the processes and situate the analysis in the broader framework of participatory Constitution-making.

1. Introduction and theoretical background

Among all legal sources, the one that needs the greatest legitimation is by its very nature the Constitution (Tofigh Citation2020). Constitution-making is supposed to be the result of a process that rests on a creative movement of the society and that includes a plurality of variously participating actors (Frosini Citation1997). However, by tradition, the very elaboration of the Constitution mainly takes place through the work of a representative body (so-called Constituent Assembly) which is distinct and sometimes considerably separated from the society and therefore an expression of popular sovereignty by means of a repetition of the logic underlying parliamentary representation (Allegretti Citation2013; Casamiglia Citation1999; Ferrajoli Citation2012). This is especially true for Constitutions adopted after WWII while in more recent times the need to go beyond traditional representative structures and to actively include citizens in the processes of Constitution-making has strongly emerged (Saunders Citation2012; Blount Citation2014).

In parallel with this paradigm shift in Constitution-making, the concepts of deliberative democracy have begun to take hold both in academic contexts and in local policymaking, especially through so-called mini-publics. Above all, the works of Habermas and Rawls favored the construction of the abstract model of deliberative democracy (Rawls Citation2005; Habermas Citation1996), which can be defined in first approximation as a theory that aims at strengthening democracy, overcoming individualist and economic conceptions, and at anchoring it to the ideas of debate, confrontation and accountability (Przeworski, Stokes, and Manin Citation2009). Hence, deliberative democrats aspire to develop a democratic ideal based on argumentation and debate that overcomes and replaces the classical model based on the majority principle (Bohman Citation1998; Bächtiger et al. Citation2018). Democracy is generally perceived as an arena in which preferences are determined through methods of aggregation that enable to establish each time which, among a series of predetermined interests, is shared by the largest majority (Chambers Citation2003, 308). Deliberative democracy, on the contrary, enhances the process of exchange of opinions and the formation of the will that precedes the specific act of voting. The compromise, once reached, legitimizes the decisions through its rational justification (Gutmann and Thompson Citation2004, 52; Elster Citation1998).

Following the aspirations of deliberative democracy to produce more legitimate decision-making and the need of Constitution-making to be made more participatory and inclusive, in recent years several attempts have been done to apply deliberative methods and ideals to Constitutional modernization processes, especially in Europe (Reuchamps and Eerola Citation2016; Reuchamps and Suiter Citation2016).

In particular, Iceland was the first in establishing a participatory, citizen-based constituent assembly alongside its regular legislature (Thorarensen Citation2017; Landemore Citation2020). Also, other participatory experiences involving ordinary citizens in drawing up or emending constitutions have occurred (with variable degrees of success or failure) in Ireland (Farrell, Clodagh, and Suiter Citation2017), Romania (Blokker Citation2017), as well as in Chile more recently (Soto Barrientos Citation2017).

Given the rapid proliferation of deliberative practices employed for reforming constitutions, the topic has been analyzed from diverging disciplinary angles and through different methodological and terminological approaches (Kontiadēs and Fotiadou Citation2018; Negretto Citation2020; Oliveira Citation2014; Tofigh Citation2020; Choudhry and Tushnet Citation2020; Levy Citation2018). Some of the studies focus mostly on the theoretical aspects of the interaction between Democratic Innovation (hereinafter: DI)Footnote1 and Constitution-making (Saati Citation2019; Chambers Citation2019; Ginsburg, Blount, and Elkins Citation2008) while others concentrate mainly on real-world practices that employ DI in Constitution-making processes (Choudhry and Tushnet Citation2020; Geissel and Gherghina Citation2016).

All this demonstrates that the focus of the observers has been set mainly on the practices that took place at the central level of government, even if the trend of employing Democratic Innovations (hereinafter: DIs) to deliberate on constitutional and institutional issues also affects the subnational level of government, although with different modes and intensities.

Hence, a gap in the research is to be identified in the scarcity of analyses on participatory Constitution-making at the subnational level of government. In fact, besides the very well-known randomly selected citizens ‘assemblies of British Columbia and Ontario enacted to amend the electoral legislation, which gained a lot of academic attention (Warren and Pearse Citation2008; Rose Citation2007), many other experiences have been relegated to the background. Lesser-known subnational experiences can however provide useful data and information for enriching the field of studies on DIs and Constitution-making.

Given their proximity to citizens, subnational units can function as laboratories of ‘participatory’ experimentationFootnote2 since there is solid evidence that public participation tends to increase as jurisdiction size decreases. In fact, it has been observed that citizens tend to engage more in ‘thicker’ kinds of public participation on the levels of government that are closer to them (Marshfield Citation2011). Furthermore, the observation of practices of DI at the subnational level of government can offer a peculiar perspective on the involvement of under-represented groups in constitutional participatory and deliberative democracy (Larin and Röggla Citation2019; Wheatley Citation2003). This is particularly true for the ethnic and linguistic minorities present in many subnational entities.Footnote3

For the reasons outlined above, this article will shed light on two processes of DI that took place in the two northern Italian Provinces of Trento and Bolzano.

The procedures, the Convenzione sull’autonomia (Convention on the Autonomy; hereinafter Convenzione) and the Consulta per lo Statuto speciale per il Trentino – Alto Adige/Südtirol (Council for the reform of the Special Autonomy Statute of Trentino – Alto Adige South Tyrol; hereinafter: Consulta) – show interesting features from many points of view even if, so far, the attention paid to them in the international scientific panorama has been somewhat marginal. Therefore, this contribution will try to highlight the most relevant aspects of the two processes by placing them in the broader framework of the studies on DIs. In particular, the focus is set on the intersection between the studies on subnational constitutionalism and the phenomenon of deliberative Constitution-making (Levy Citation2019).

The concept of subnational constitutionalism refers to decentralized (federal, quasi-federal and regional) States in which subnational entities (i.e. Provinces, Regions, Länder) are allowed to establish their own institutions, forms of government, public finance systems in their respective constitutional charters under the aegis of the national constitution in order to achieve the best interest of their citizens (Ginsburg and Posner Citation2010; Burgess and Tarr Citation2012). This is the case in Italy, where all twenty regions adopt Statuti regionali, in the form of an ordinary law, as their subnational constitutional charters. Among these, the so-called Statuti speciali of the five autonomous regionsFootnote4 are conferred the rank of constitutional laws, both in form and in substance.

The participatory processes of the two Provinces are of peculiar interest for this special issue: on one hand, for their relevance in the context of DIs, in general, and the field of deliberative Constitution-making, in particular; on the other, for a better and deeper understanding of the play out of democratic innovative practices in minoritarian and multilingual contexts (Gherghina, Mokre, and Miscoiu Citation2020) in which the issue if deliberative democracy has often been neglected (Addis Citation2009). It goes without saying that the study of DI practices in multilingual contexts is extremely relevant especially if we consider that ‘multilingualism is challenge to any deliberative practice, because any linguistically plural society is also a culturally plural society’ (Alber, Röggla, and Ohnewein Citation2018).

Investigations in this field have been partly discouraged by those who have considered mass deliberation in deeply divided societies as impossible or undesirable (O’Leary Citation2005) and multilingualism as a disincentive for deliberation since mutual understanding becomes much more difficult (Fiket, Olsen, and Trenz Citation2014). However, more recently, the literature has begun to seriously address the issue of linguistic diversity in the context of deliberative and participatory democratic practices, given that ‘after all, deliberative democracy relies heavily on talk as the basis for political decision-making’ (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Citation2018, 16). Hence, the presence of different languages (especially in many subnational contexts e.g. Catalonia, Belgium etc.) makes mutual understanding even more difficult and hinders the development of a unified public opinion (Reuchamps, Kravagna, and Biard Citation2014). For this reasons, further study in this specific area is necessary. Thus, this piece will try to move forward in this endeavor by identifying specific aspects that will deepen our understanding of DIs operation in contexts involving (linguistic) minorities.

The paper will follow a qualitative case-study approach employing this methodology for enlightening the most relevant features of the proceedings of the Consulta and the Convenzione (Gerring Citation2013). Original records of the processes and secondary literature will be the main objects of the study combined with first-hand experience of both experiments gained through direct participation as an external observer of the author, in both participatory processes which took place between 2015 and 2018. A legal analysis will complement the investigation since both processes were regulated in specific laws. Hence, the paper will not only look at how the processes developed but also at the design of the legal framework in which these were positioned, given the high degree of institutionalization characterizing these experiences.

As to the structure, the article first outlines (Section 2) how the autonomy arrangements of the special Region of Trentino – Alto Adige South Tyrol function and highlights differences among the two constitutive entities of the region: Trentino (also referred to as the Province of Trento) and South Tyrol (also referred to as the Province of Bolzano). This permits the understanding of the reasons behind the initiation of the two processes, their procedural peculiarities, similarities and differences. Section 3 tackles the most relevant aspects of the case-studies: the legal acts instituting the Convenzione and Consulta, the two bodies in charge of conducting the participatory processes, the main contents of the processes and examines how the two were designed and how they performed. Section 4 focuses on the specific issue of the involvement of linguistic minorities in the processes (Gherghina, Mokre, and Miscoiu Citation2020) while the concluding section summarizes the main findings, highlights some critical aspects and indicates directions for further research.

2. The autonomy arrangements of Trentino- Alto Adige/ South Tyrol

Italy is an asymmetrical regional State. As anticipated above, the Italian Constitution foresees twenty regions, fifteen of which are ordinary regions while five of them are autonomous. The difference between the two ‘kinds’ of region is to be found mainly in the asymmetry concerning the extensions of powers attributed to them with autonomous regions being those that enjoy the largest portions of legislative, administrative and financial powers (Palermo Citation2015a). Among the five special regions, Trentino – South Tyrol enjoys its own peculiar conditions of autonomy. In fact, it is common to use the expression ‘asymmetry within the asymmetry’ when referring to autonomous regions since all of them enjoy a different degree of autonomy.

Unlike the other four autonomous regions, Trentino Alto Adige is structurally unique. Pursuant to art. 116 of the Italian Constitution, it is made up of two autonomous provinces, (the Province of Trento, commonly known as Trentino, and the Province of Bolzano, commonly known as South Tyrol). The two provinces enjoy and enact most of the autonomous powers. In fact, while the so-called first Statute of Autonomy, adopted in 1948 granted most of the autonomous powers to the region, the second Statute of Autonomy introduced in 1972 meant the transfer of almost all powers from the region to the two provinces. So, the second Statute transformed the two Provinces into the main driver of their special autonomy, leaving the region with very few functions and acting as the container of the two self-governing provinces. The change of balance between regional and provincial powers was due to the peculiar situation of the Province of Bolzano with regard to the presence of linguistic minorities.

As a matter of fact, while Trentino is predominantly Italian-speaking, South Tyrol is characterized by the presence of the cohabitation of three linguistic groups (Italian, German and Ladin) (Carlà Citation2007). According to the 2011 State census, the current distribution of the three linguistic groups is 69.4% German-speakers, 26.1% Italian-speakers, and 4.5% Ladin-speakers in a population of 511,750 (Larin and Röggla Citation2019). South Tyrol has been studied vastly because it represents a unique case in which the management and regulation of the cohabitation of linguistic minorities is concerned (Fraenkel-Haeberle Citation2008; Mazur-Kumric Citation2009; Alber and Palermo Citation2012). The model which regulates cohabitation among the three groups has been defined as consociationalism (Markusse Citation1997; Pallaver Citation2008). In brief, it can be described as a ‘form of government of consensual ethnic power sharing with the core principles of cultural autonomy for each group, language parity and ethnic proportionality’ (Alber, Röggla, and Ohnewein Citation2018, 195).

For the sake of completeness, it should also be noted that even in the Province of Trento, linguistic minorities are present, albeit to a much lesser extent. According to the 2011 Census, 4% of the population in Trentino belongs to a linguistic minority, with Ladin populations representing the majority with a representation of 3.5%. The remaining 0.5% is made up of the linguistic minorities of Mocheni and Cimbirans (Penasa Citation2014).

This divergence is the reason why the historical evolution of the Province of Bolzano differs profoundly from that of Trento with regard to its social and cultural background. In addition, many provisions in the Autonomy Statute refer only to the Province of Bolzano and its minority protection system and do not apply to the Province of Trento. This is why, in the last decades, the relation between the two Provinces has changed by means of an ever-increasing gap between the two, with the Province of Bolzano strongly focused on strengthening its provincial autonomy and the protection of its diversity management system and the Province of Trento more linked to the idea of a region and agreement with the neighboring province.Footnote5

In order to properly understand the scenario in which these DIs have taken place, it has to be considered that – despite most of the legislative, administrative and financial powers being vested in the provinces – the Statute of Autonomy (Statuto di autonomia) still has regional relevance and concerns both the provinces of Trento and Bolzano. This means that the power of initiating the process of revision of the Statute is vested in the Regional Council. The latter is made of the two provincial councils of Trento and Bolzano, acting as a ‘condominium organ having accessorial nature’ reflecting the empty box-structure of the Region (Alber, Röggla, and Ohnewein Citation2018).

In order to ensure the special status of this legal source, the Constitution provides that the statutes of the special regions are adopted by the national parliament with a constitutional law (Palermo Citation2015a). Amending the statutes implies the aggravated constitutional procedure foreseen by the constitution in its art. 138 must be adhered to; but not only since, as mentioned, the power of initiating the revision process is vested with the regional council. However, the regional council does not act autonomously – being the sum of the two provincial councils (35 members each). Hence, the regional council acts accordingly to the propositions put forward by the two provincial councils which have to agree among themselves in order to confer a shared proposal on which to start the reform procedure (Palermo Citation2008).

3. The Convenzione and the Consulta

3.1. Adoption and establishment of the legal acts

It is now possible to understand why, in order to initiate the process of revision of the 1972 Statute of Autonomy, the two provincial councils activated two separate participatory processes – instead of one with regional relevance – that ran almost in parallel between 2015 and 2017 (Cosulich Citation2016).

In 2013, the now-President Arno Kompatscher’s in his first run as president of the Province of Bolzano came up with the idea of a Convenzione as a way to give more legitimacy to the amendment process: one the one side, the strongly felt need of reforming the Statute, and, on the other, a wave of constitutional reform that was going on in Italy at that time (Larin and Röggla Citation2019, 1025). The drive to design a process of this kind is also due to the prominence that experiences such as the participatory constitutional reforms in Iceland (Bergsson and Blokker Citation2013) and Ireland (Suteu Citation2015) had at the time, together with the activation of an online participation process on the constitutional reform at the national level (Palermo Citation2015b, 40–41).Footnote6

Instead, in the Province of Trento, the establishment of the Consulta was due primarily to the previously described way in which the Statute is amended, which provides for the involvement of both Provinces in the drafting of the proposal. In fact, as just seen, the reform of the Statute of Autonomy is of regional competence, meaning that both provincial councils need to agree on one common project of reform which must then be sent to the national parliament where it undergoes the constitutional revision process.

Therefore, the establishment of a South Tyrolean Convenzione entitled with the task of initiating the reform process, left the Province of Trento with no other choice than establishing its own process for gathering opinions and proposals for reforming the Statute (Murphy Citation2018, 92). Otherwise, the Provincial Council of Trento, in order to activate the constitutional process of revision, would have had to agree upon a reform proposal elaborated through a participatory process that involved only the South Tyrolean part of the region. Hence, the Province of Trento also adopted its own law, partially replicating the provisions of the one instituting the Convenzione.

In fact, the first step the two Provinces undertook in order to set up the processes consisted of adopting a legal act each institutionalizing the procedure needing to be followed.Footnote7 These laws are a particularly relevant aspect of the establishment and functioning of the two experiences, especially in the wake of the studies that deal with the institutionalization of DIs (Smith Citation2018; Ravazzi Citation2016; Offe Citation2011; Warren Citation2014; Hartz-Karp and Briand Citation2009; Lewanski Citation2013).

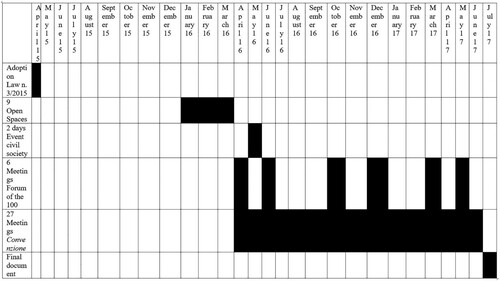

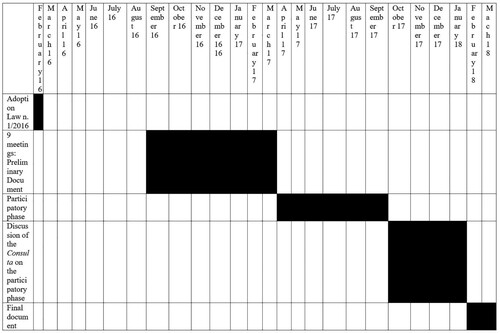

The two acts entered into force in a relatively short span of time, with the Province of Bolzano adopting them in April of 2015 (Law n. 3/2015) followed by the Province of Trento in February of 2016 (Law n. 1/2016). The objective explicitly stated in both acts was to establish a broad process of participation to encourage the involvement of citizens in the elaboration of the contents of the reform of the Special Statute (Happacher Citation2017). Both acts accord a central role to a specifically designed body, the Convenzione in Bolzano and the Consulta in Trento, entrusted with initiating the procedure, managing the participation of the society and summarizing the outcomes in a final document to be handed out to both provincial councils.

3.2. Bodies’ composition

As far as the composition is concerned, the Convenzione is configured as an auxiliary body of the Provincial Council and it is made of thirty-three members. These represent different categories of society: ordinary citizens (8, drawn from the forum of the 100, see below), entrepreneurs (2), municipalities (4), trade unions (2), political representatives (12), legal experts (5).

The law states that the composition of the body must guarantee the proportional representation of the linguistic groups (reflecting the percentages of the last official population census) and a balanced gender representation. Moreover, in order to represent all three linguistic groups in the composition of the Presidency, three people were elected, each belonging to a different linguistic group (German, Italian and Ladin) (Rosini Citation2015, 7).

Similarly, the Consulta, is shaped as an independent consultative body. The law foresees that is made up of twenty-five members, representing: provincial councilors (9), organized civil society (7), lawyers (2), local entities (4), trade unions (3) all selected according to a rather articulated procedure and finally nominated by the president of the province.

Both bodies’ membership represents a mix of politicians and stakeholders that reflects a corporatist model, much more than a citizen’s assembly model (Poggio and Simonati Citation2018). Moreover, both laws provide that the members of the Convenzione and the Consulta work on a voluntary basis without foreseeing any sort of remuneration.

It is however to be noted that the law of the Province of Bolzano also foresees a second body, the ‘Forum of the 100’. The latter is meant to act as a permanent link between ordinary citizens and the Convenzione. It is designed as a sui generis ‘citizens’ assembly’ in resemblance of what the literature defines as a ‘mini-public’(Smith Citation2012; Elstub and Escobar Citation2017) and is made up of 100 provincial residents. In order to be chosen, all interested residents register and make themselves available to take upon this task. 1829 people registered, and 100 of them were selected to be members of the forum through stratified random sampling in a way that would represent the age, gender, and linguistic group proportions of the province as precisely as possible (Larin and Röggla Citation2019). In the first meeting, eight members of the Forum were elected in order to also be members of the Convenzione, roughly following the proportion of each linguistic group.

The number of members composing the Convenzione – 33 – is not completely new in the deliberative democracy panorama. 33 is in fact the number of politicians that compose the Constitutional convention established in Ireland in 2012 in order to amend the Constitution. Those 33 members were augmented by 66 randomly selected citizens and together formed the convention, comprising a total of 99 participants (Farrell, Suiter, and Harris Citation2018). This figure also shows us that the size of the Forum of the 100 has a certain resemblance to Irish constitutional convention.

The inspiration taken from the most renowned DIs is also revealed when looking at the composition of the bodies, especially at the Forum of the 100. In fact, particularly in the case of the province of Bolzano, one can identify a desire to replicate models already experimented in other countries, such as the citizens assemblies of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and British Columbia (Snider Citation2008; Rose Citation2007). This inspiration is evident in particular from the choice to employ a mini-public of randomly selected citizens to support the work of the body composed of political representatives, experts and organized civil society. By placing a mini-public alongside a body of specifically selected members which represent institutions and other interest groups, it is also possible to uncover the mediation of the political will of the provincial council with that of the academics involved in designing the processes. The latter were more ready to experiment with forms of deliberative democracy based on the random selection of participants. The same did not happen in the elaboration of the Consulta – instead designed as an assembly representing only specific societal interests and not replicating more innovative logics.

Moreover, the law states that consensus has to be reached for the Convenzione to adopt its decisions. It can be assumed that the legislator was inspired by the most classical theories on deliberative democracy when drafting this provision, overlooking the fact that in more recent times deliberativists have questioned the viability and effectiveness of this method (Martí Citation2017). Nevertheless, institutionalization in a law of the principle of consensus, remains noteworthy. It is still to be seen, and will be in the next sections, how this actually functioned in practice. On the contrary, the law on the Consulta did not provide for a specific decisional mechanism to be applied.

3.3. Time frame of the processes

The law on the Convenzione sketches out the phases to be followed by a process that should not endure for longer than 12 months. An initial phase in which an introductory document is elaborated; a phase of proposal hearings presented by civil society in the participatory process and a proactive phase, in which a document containing proposals to the Council regarding the revision of the Statute of autonomy is elaborated.

The law on the Consulta does something similar, even if in a more detailed way. It states that within 120 days from its first session, the Consulta shall prepare a preliminary document with the criteria and main guidelines to be followed when drafting the reform proposals. This preliminary document must be then submitted to a participatory process that can last for a maximum of 180 days. Finally, the Consulta has 60 days to draft and finalize the final document (Murphy Citation2018, 95).

Also, the laws did not contain any measure referring to the consequences of the two processes on policy making.

The legal design is interesting because, while the two legal acts define in great detail some specific aspects of the processes – such as the number and duration of the sessions to be held each month (two three-hour sessions per month for the Convenzione and two four-hour sessions per month for the Consulta) – they leave many other aspects open to interpretation, particularly with regard to the ways in which citizens have to be involved in the participatory phases of the procedures. It was left to the Consulta and Convenzione to decide how to structure them. The transparency of the legal acts with regard to the ways in which citizens might be involved in the processes can be traced back to the idea, put forward by many – especially Italian – scholars, that participation cannot be reduced to procedures meticulously regulated in a law (Allegretti Citation2006; Valastro Citation2011). This would limit the creative potential of DIs, which need to incorporate room for maneuver in order to operate at their best. This conception derives in particular, from observation of the experience of the region of Tuscany where, for more than a decade now, a law that organically regulates participatory democracy has been in force (Brunazzo Citation2017). This law, which is believed to be the first law globally to abstractly regulate DIs, deals with various aspects of DIs but does not regulate the way in which to involve citizens (Lewansky Citation2013). Undoubtedly, the legislators of the Provinces of Trento and Bolzano were inspired by this experience of leaving the decision on how to involve citizens open.

3.4. Process design and implementation of the Convenzione

With regard to the process design and process implementation, we encounter fundamental differences between the two case studies.

In Bolzano, the works of the Convenzione of 33 and the Forum of 100, were preceded by a phase of broad involvement of the population. Nine meetings employing the Open Space TechnologyFootnote8 were held in all main cities and towns of South Tyrol, together with events specifically addressed to civil society organizations. The meetings followed a general guiding question: ‘South Tyrol: what future for our territory?’ chosen by the presidency of the provincial council. At the beginning of each meeting, it was explained in detail by the facilitators in charge of conducting it, in both the German and Italian language, how the process was supposed to work (Alber, Röggla, and Ohnewein Citation2018, 211–212). The whole process was organized by the Eurac Research experts and was facilitated by neutral, externally contracted, moderators.

The goal of these events was to collect different visions, facilitate dialogs and survey citizen opinions in order to better define the topics on which the Convenzione should have worked. Altogether, about two thousand people participated in the meetings that took place between January and March 2016. The proposed topics, freely chosen by the participants, among others touched upon the foundation of the protection of minorities, the school system, the system of proportional ethnicity, legislative and administrative autonomy, and the peoples right to self-determination. The results were collected in minutes then transcribed and summarized according to qualitative criteria and published on the official website of the process.Footnote9

Each meeting had a different demographic composition, but in general terms the Italian linguistic group was underrepresented. On the contrary, the South Tyrolean (German speaking) ‘patriotic association’ known as the Schützen, put significant effort into organizing its members’ participation, attending almost all events and providing many talking points (Röggla Citation2018).

In May 2016, after the Open Spaces, a specific event was organized for the civil society organizations. Participation was open to all associations of the Province, upon previous registration. In the end, more than 50 organizations subscribed and took part in the four workshops, mainly representing (again) the German-speaking group.

It is important to note how the self-selection bias – widely discussed in the literature on deliberative democracy (Harmen and Michels Citation2021; Elstub and Escobar Citation2017; Setälä Citation2017; Jacobs and Kaufmann Citation2021), – is more than apparent here. This is due to the open-invitation recruitment method employed for both the Open Spaces and the event for organized civil society. The more evident outcome of this bias is in fact the overrepresentation of the German-speaking group in both events that managed to partly undermine the legitimacy of the conclusion reached during the deliberations. This is why, the Forum of the 100 followed the deliberative mini-publics model (as, for example, employed by the most prominent case of the G1000 in Belgium) in order, on the one hand, to face the problem of scale by involving small but diverse groups of citizens selected by lot, so that everyone had an equal probability of participating and, on the other, to keep to a minimum the self-selection bias that gives undue influence to small sections of the population (Elstub and Escobar Citation2017).

All outcomes of the deliberations of the Open Spaces and of the organized civil society event, were summarized in a document that, together with the outcomes of the open spaces, formed the material that was delivered to the Convenzione and the Forum of the 100.

The Forum of the 100 met six times and elaborated its proposals, which were then forwarded to the Convenzione as further input for reflection. The works of the latter were organized into eight thematic working groups. The sessions of each single working group were closed to the general public in order to guarantee neutrality in their debates. Instead, the plenary sessions were public.

The Convenzione of the 33 met twenty-seven times over a period of just one year (April 2016–June 2017) and drew up a document that summarizes as comprehensively as possible, the prospects of South Tyrolean society with regard to the reform of its autonomy. All sessions were recorded and transmitted in real time via the internet. The Convenzione also made use of the possibility of hearing experts when examining particularly complex issues. In addition, one of the sessions of the Convenzione provided for a hearing of the Forum of the 100 to discuss its results. The Convenzione did little to comply with the procedure outlined by law. Instead of formulating an introductory and final document on the basis of the discussions, the works began with a general introduction on the actual content of the provincial autonomy. The introduction was delivered by two of the legal experts who were members of the Convenzione and who thus acquired a general consultative role that partly overlapped their role as members body. The general introductory discussion offered ideas for the topics that were then the subject of the individual working meetings.

Among the identified macro-themes were the role of the region, the protection of minorities and the role of the province within the European Union. Mostly debated topics were the division of competencies between the State and Provinces and the mechanisms to guarantee the special autonomy. While there was broad convergence on the expansion of legislative powers to further strengthen provincial autonomy on other topics, such as self-determination and the schooling system, it was much harder to find an agreement among the 33 members (Happacher Citation2017).

In fact, according to the consensus principle, no formal voting was foreseen since members should have consensually agreed on the proposals put forward. This also applied to the forum of the 100 that also had to shape its recommendations according to consensus. However, while in the forum this methodology worked pretty smoothly, the same did not apply to the Convenzione of the 33 where this provision ignited long and controversial debates, making it very hard for the members to come up with shared views and opinions (Alber, Röggla, and Ohnewein Citation2018, 216). Hence, the practical and compromised solution reached in order to move on with the debates, has been defined as ‘softened consensus’, which allowed dissenting ‘minority reports’ to be submitted along with the final proposal to the Provincial Council on issues where no consensus could be found (Larin and Röggla Citation2019, 1027). This solution was also made lawful through an amendment to the law on the Convenzione.

The final document of the Convenzione was drawn up in July 2017 by three of the five legal experts on behalf of the Convenzione itself and based on the complete minutes of the proceedings. Its discussion in the plenary session generated four minority reports ().

3.5. Process design and implementation of the Consulta

With regard to the experience of the Province of Trento, according to art. 3 of the law, to a certain extent, the Consulta had to organize the participatory process in the forms that it deemed most appropriate, while conversely, some indications among which: the publication on institutional websites of the preliminary document, accompanied by a report; and the organization of public debates, also at local level, that had to be articulated in three moments – information, presentation of the preliminary document and discussion had to be followed. These sweeping indications determined the possibility of the Consulta to shape the process with a certain freedom for its members, even if it had to consider necessary temporal and financial limitations.

The Consulta, after nine sessions of discussion, elaborated and published its preliminary document which was divided into eight thematic (Cosulich Citation2018).

The members of the Consulta decided to carry out the participatory process both digitally and in person. The online process was brought to the attention of citizens through the provincial e-democracy platform ‘Iopartecipo’.Footnote10 Here the discussion was divided into the same thematic areas addressed in the preliminary document. All comments and questions were published online and remained available throughout the whole process. On the other side, in addition to the online platforms, a calendar of meetings on the territory and other initiatives (hearings, workshops on linguistic minorities and on autonomy) with the aim of presenting the preliminary document and encouraging an open confrontation with citizens, were organized throughout the territory of the Province of Trento to ensure a wider participation. All proposals, observations and comments that emerged during the meetings and the other initiatives were summarized and also published on the online platform (Murphy Citation2018).

Summarizing, the participatory phase lasted a total of 6 months, from 14th of March 2017 (with the presentation of the preliminary document to the Provincial Students’ Council) until 30th of September 2017. 690 people participated in the 18 territorial meetings, the three workshops on linguistic minorities and the workshop on autonomy. 168 of them intervened by taking the word: some to ask questions, or for information on the path of reform of the Statute; express appreciation or perplexity; others to comment on the thematic areas proposed in the preliminary document, share ideas and make observations.

At the end of the participatory phase, 258 contributions were collected in the platform ‘ioPartecipo’, of which: 27 proposals, 11 comments and 29 recommendations were suggested in the online platform; eight contributions arrived via email; 162 proposals advanced during the territorial meetings; 21 received documents. Most of the contributions focused on three thematic areas – fundamentals of autonomy, autonomous provinces and region, linguistic minorities. All contributions were analyzed by the Consulta after closing the participatory phase, to assess whether, and to what extent, to integrate the suggestions and proposals in the final document. The Consulta discussed the contributions of the participatory phase between October 2017 and January 2018: six working sessions in which all thematic areas were discussed in depth – starting from an introductory report that took into account the contributions collected in the participatory phase. At the end of the participatory process, the Consulta reviewed all the thematic areas, comparing the indications received with those of the preliminary document. The Consulta has since specified, developed and integrated the evaluations and proposals in the final document, which was unanimously approved in March 2018 (Alber and Woelk Citation2018) ().

3.6. The consequences of the two processes on decision-making

The consequences and the effects that DIs exert on law and policymaking is a largely debated issue. It is in fact very hard to distinguish the impact of a procedure of DI from the influence that a myriad of other factors can play on a specific policy outcome (Font, Pasadas del Amo, and Smith Citation2016).

Insofar as consequences of both processes are concerned, we have to acknowledge that the final documents did not impact the decision-making process in any way. In fact, after having elaborated the final documents and delivered them to each respective provincial council, there has been no further political activity with regard to the revision of the Statute. To this regard, the objectives set by both laws were only partially achieved. If both processes managed to fulfill all legal requirements and produce a final document containing a concrete proposal for the Autonomy Statute, neither of them was able to generate the propulsion for starting the reform process.

Both processes have been strongly criticized in different respects. First of all, the critics were concerned about the lack of cooperation between the two provincial bodies, given the need of a regional agreement on a common proposal in order to start the parliamentary constitutional process for reforming the Statute. The works of Consulta and the works of the Convenzione were generally perceived as parallel paths with no real possibility of agreeing on a shared final document. To this extent, both laws provided for moments of convergence between the two bodies, even if specific indications on how and how frequently these should have occurred were not included. The two bodies only met twice (in January and May 2017) and in fact, did not manage to initiate any kind of long-term cooperation or to provide for valid coordination mechanisms for the elaboration of a shared final document.

4. What room for linguistic minorities?

We can now investigate if and how the presence of linguistic minorities was taken into account in the design of the process and assess how this issue was addressed in the final documents. Two dimensions can be considered and are of relevance for the purposes of this special issue. One is how substantially different linguistic groups deliberate together on topics which directly affect the fundamentals of the protection of their rights. The second is procedural in nature, concerning how much the structure of the process is designed for giving equal opportunities in terms of participation to all linguistic groups. As already stated, the different composition of the population in terms of linguistic minorities in Trento and Bolzano has to be considered when exploring these two aspects.

4.1. The relation between linguistic groups in the participatory debates

Regarding the first dimension – i.e. the content of the debates – we note that in the initial participatory phase of the process held in the Province of Bolzano, the topic of the relations between linguistic groups was addressed in each of the nine open spaces. As this is a particularly sensitive and controversial issue, opinions were very diverse and it was certainly difficult to find a univocal view addressing how the current proportional system of protection of linguistic minorities works, and if and how it should be revised in a reformed Statute of Autonomy. In fact, it is possible to observe that in the open space, there were two main trends of opinions. One was more inclined to loosen the measures on minority protection, for example, by suggesting the introduction of bilingual schools; while another underlined the necessity to maintain the system as it is. These two tendencies are also reflected, even if with some contradictions, in the final document drafted by the Convenzione. As reported by Larin and Röggla (Citation2019) the final document states that measures that focus on what we call ‘relations between linguistic groups’ were not discussed because the Convenzione of the 33 felt that there was no need for further reform, with the exception of improving the protection and representation of Ladin-speakers.

However, the authors highlight that this is a strange, incorrect claim, as the final document itself demonstrates that discussions were held on topics such as reforming public service linguistic proportionality, introducing multilingual schools and generally ‘loosening’ minority protections. Thus, they go on, affirming that:

This divergence highlights one of the most important results of the Convenzione process, the public demonstration that German- and Italian-speakers are generally concerned with different aspects of the autonomy arrangement. German-speakers are focused on ‘relations between institutions’, and Italian speakers are focused on ‘relations between linguistic groups’. Most members of both groups agree that provincial autonomy is beneficial, and many supports its expansion. But most German-speakers have no interest in changing the measures that regulate relations between linguistic groups, which is the principal concern of most Italian-speakers, who feel that these measures unfairly disadvantage them and should be either scaled back or abolished, now that they have served their purpose. (Larin and Röggla Citation2019, 1029)

The Consulta in the Province of Trento discussed the situation of its Ladin minority in-depth, suggesting that their level of protection which aims at having a similar level of protection as the Ladin-speakers in neighboring South Tyrol should be augmented. In this regard, the trans-provincial character of the Ladin minority could be acknowledged in order to harmonize the regional minority protection framework. In addition, according to the Consulta, the Statute of Autonomy should be modified to grant more visibility to all minorities by explicitly recognizing their cultural and linguistic value in the Statute of Autonomy (Alber, Röggla, and Ohnewein Citation2018, 219).

4.2. The linguistic divide in the process design

About the second dimension, we want to detect how the territorial division among different linguistic groups – in particular in the Province of Bolzano – was taken into consideration in the procedural design process.

In fact, this is a particularly interesting issue since the methodological organization of participatory setting in contexts in which citizens speak different languages, is a question often neglected in studies on DIs (Addis Citation2018). While the more theoretical facets of deliberative democracy in divided societies have been investigated (Dryzek Citation2016), the way in which DIs should be translated in practice in such contexts, has remained on the background. However, the multilingual question applies not only to situations such as that of the Province of Bolzano, which is characterized by national linguistic minorities, but also to every contemporary society that is nowadays confronted with so-called ‘new minorities’, making it a pivotal issue for the successful functioning of DIs in almost all contexts. Since DIs are intended to make policy making more inclusive and legitimate, it is urgent to develop practical solutions that allow different groups to deliberate together. In fact, DIs are able to express their legitimizing potential fully only if those who deliberate ‘truly enter as equals, whether they are able to express their visions of the common good on equal terms, and whether the forms and practices that govern deliberative assemblies advance or undermine their goals’ (Lupia and Norton Citation2017, 64). Language is without doubt one of the enabling factors.

In the case of the Province of Bolzano, the basic linguistic rule applied in order to allow all participants to actively contribute to the debates in the open space participatory phase was that of the mother tongue, which means that each participant could express themselves in their respective mother tongue (being it Italian or GermanFootnote11) and other participants could reply in theirs. However, since not all citizens are bilingual, translators were available if needed. Making use of one-to-one translators complicated things in two ways. On the one side, the flow of the debate was slowed down since the translation represented a break in the discussion. This is an evident a down-side since deliberation should occur freely and fluently without any external factors influencing it. On the other hand, the logistic and economic effort to offer all participants the possibility of relying on translators for facilitating discussions is very big. If we imagine a process involving a larger number of participants and/or more than two potential languages to be translated, we easily understand how this could become a hard to ignore logistic obstacle. Moreover, having had the chance to directly observe the open spaces’ debates in action, it was clear that discussion groups were formed according to the same linguistic group. If on one side Open Space Technology offers freedom in terms of topics and discussions, on the other it does not provide for organizing and controlling mechanisms on how citizens decide to gather and has the drawback of potentially fostering the maintenance of social biases such as the division of the society in its basic cultural-linguistic components.

The Convenzione and the Forum of the 100 also worked by applying the ‘Mother tongue rule’ with translators available at all gatherings. The diverse linguistic composition of South Tyrolean society is also reflected in the composition of the two bodies that match the linguistic group proportions of the province as closely as possible.

In the case of the Province of Trento, we are faced with a much more uniform society. As previously stated, the presence of linguistic minorities is very low and the population is predominantly Italian speaking. This is probably the reason why the Consulta did not foresee any specific measure to encourage the involvement of minority groups in its process. Thus, this is a further sign of a lack of attention and reflection in the elaboration phase of the participatory phase of the process. This is also confirmed by the fact that the strengthening of the protection of the Ladin minority was one of the themes at the center of the Consulta’s work, as seen above.

5. Concluding remarks

The two cases studied in this paper provide the opportunity to briefly address some final issues that have characterized them and that may be useful for future DI processes and research.

Firstly, it is important to acknowledge the central role that experts had in both the Convenzione and the Consulta processes. In both experiences, the high technicality of the topics dealt with, and the strong political and technical component, has somehow lowered the impact of the civic voice in the opinions expressed in the final documents. In fact, the strong presence of academics and experts in the debates made it difficult for ordinary citizens to intervene on equal terms. The topic of the interaction among lay citizens and experts in deliberative and participatory democracy has recently gained academic attention (Lightbody and Roberts Citation2019; Fischer Citation2009), in particular considering that on broad political questions, such as the reform of a Constitutional document (as in this case the autonomy Statute), the opinions of citizens and experts might differ profoundly (Elstub and McLaverty Citation2014, 67). In the processes outlined here, the (legal) experts played a pivotal part in influencing the positions taken in the concluding documents, in part due to the residual role attributed to the citizens – especially in the experience of the Province of Trento as recognized by the Consulta itself in the final document where it is acknowledged the lack of an adequate reflection on the tools to be used for the participatory process in order to encourage a collective debate on the future of the autonomy. (89 and 90 of the final documentFootnote12). The lesson to be learned here is that the balance between the position of the experts and the lay citizenry, has to be carefully taken into account when designing the procedural aspects of the processes, particularly when deliberating on highly political and sensitive issues.

It has also been seen that both processes, as the results of their works, developed articulated documents containing concrete proposals for the reform of the Statute of Autonomy. Nonetheless, the regional council did not follow up on the reform process and did not initiate any kind of political debate about the contents of the proposals. This has been considered as a clear sign of failure, even though it is very hard to measure to what extent the decision of the Regional council to not continue on the path of the reform of the Statute, can be attributed to reasons specifically related to processes, rather than to other external political factors. However, if we consider this issue from a more general perspective, we notice that it affects many other DI processes. In fact, their outcomes frequently struggle to transform the constitutional status quo (Papadopoulos and Warin Citation2007) into real institutional reform and to trigger actual change. Hence, the potential of these practices remains more than often unexpressed, demonstrating that the complexity of our societies nowadays also poses significant obstacles to the effective realization of the ideal model of participatory Constitution-making at the subnational level of government.

Furthermore, the case-studied addressed in this paper show that DIs taking place at the subnational level of government need to be taken into account in the context of the studies on deliberative Constitution-making given the power granted to many constituent units of reforming and emending subnational constitutional documents. By doing so, this field of research would be enriched with new case studies, capable of showing also singular aspects, sometimes peculiar to subnational contexts such as the presence of minority groups. In fact, the latter deeply complicates the management and organization of deliberative processes. Moreover, in this particular case, the task of the subjects involved to deliberate exactly on issues related to linguistic-identity questions has certainly not facilitated the progress of the process. This complexity, however, should not lead to see the presence of minority groups as an obstacle, but should spur future research to focus on aspects related to the designing and structuring of participatory and deliberative processes in these specific contexts. In fact, if DIs are tools designed to make democratic decisions more transparent, legitimate, inclusive, and plural, social diversity must be reflected as much as possible throughout the whole process.

Finally, it is also important to consider the aspect of the institutionalization of DIs and their transposition into legal norms. The cases analyzed in this article have shown how careless legislation regarding participatory processes can lead to unexpected and unwanted outcomes. This is another issue on which it will be desirable to focus future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martina Trettel

Martina Trettel, PhD in Constitutional and European Legal Studies, is a Senior Researcher at the Eurac Research Institute for Comparative Federalism (Bolzano, Italy) and lecturer at the Universities of Verona and Trento. Her main research interests are Democratic Innovations and Participatory Democracy, Federal and Regional Studies and Comparative Constitutional Justice.

Notes

1 This paper refers to the term Democratic Innovation as intended by Elstub and Escobar (Citation2019, 28).

2 As suggested in the famous sentence New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 311 (192) of the Supreme Court: “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country”.

3 For instance the Spanish autonomous Community of Catalunya established in 2004 an innovative democratic process of participation in order to revise and amend the Statute of Autonomy (Alonso Perelló Citation2006).

4 Valle d’Aosta, Trentino-Alto Adige-South Tyrol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Sicily and Sardinia.

5 Despite the differences, the two provinces show also many similarities making the two procedures comparable. In particular, similarities concern demography, geography and wealth, having both a similar number of inhabitants (around 500.000), a mostly alpine territory and a GDP per capita higher than the national average. In fact, they are first (Bolzano) and fourth (Trento) in the ranking of Italian regions by GDP per capita according to the studies conducted by the South Tyrol’s and Trentino’s statistical institutes (ISPAT and ASTAT).

6 For all information relating to the participatory consultation procedure see: http://www.riformecostituzionali.partecipa.gov.it/assets/PARTECIPA_Rapporto_Finale.pdf.

7 The laws are available in Italian language at the following links: http://lexbrowser.provinz.bz.it/doc/it/201949/legge_provinciale_23_aprile_2015_n_3.aspx?view=1; https://www.consiglio.provincia.tn.it/leggi-e-archivi/codice-provinciale/Pages/legge.aspx?uid=28211.

8 In an open space meeting, there is neither an agenda nor a guest list. Every participant can join or leave the open space at any time. The participants come forward with discussion topics following an overarching leading question. The results of the working groups are documented by the participants and can include general or controversial considerations as well as concrete recommendations. There is total freedom with regard to the role of participants: everyone can introduce a topic, chair a discussion round, contribute to the discussion or just observe (Owen Citation1997).

9 All available at this link: http://www.convenzione.bz.it/it/files.html.

11 Ladin was not foreseen as a specific language since all Ladin speakers are bilingual, meaning that they are able to speak at least German or Italian in addition to Ladin. This is due to the Ladin schooling system which is trilingual.

12 Available here: https://www.riformastatuto.tn.it/DOCUMENTO-CONCLUSIVO-DELLA-CONSULTA in Italian language.

References

- Addis, Adeno. 2009. “Deliberative Democracy in Severely Fractured Societies.” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 16 (1): 59–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/gls.2009.16.1.59.

- Addis, Adeno. 2018. “Constitutionalizing Deliberative Democracy in Multilingual Societies.” Berkeley Journal of International Law 25: 117–164.

- Alber, Elisabeth, and Francesco Palermo. 2012. “Creating, Studying and Experimenting with Bilingual law in South Tyrol: Lost in Interpretation?” In Bilingual Higher Education in the Legal Context: Group Rights, State Policies and Globalisation, edited by Xabier Arzoz. Vol. 2: Studies in International Minority and Group Rights 287–309. Leiden: Brill.

- Alber, Elisabeth, Marc Röggla, and Vera Ohnewein. 2018. “‘Autonomy Convention’ and ‘Consulta’: Deliberative Democracy in Subnational Minority Contexts.” European Yearbook of Minority Issues Online 15 (01): 194–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/22116117_01501010.

- Alber, Elisabeth, and Jens Woelk. 2018. “„Autonomie(reform) 2.0“: Parallele Verfahren partizipativer Demokratiezur Reform des Autonomiestatuts der Region Trentino-Südtirol.” In Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2018: Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa, edited by Europäischen Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung Tübingen, 1 Auflage, 172–188. Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 19. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

- Allegretti, Umberto. 2006. “Basi giuridiche della democrazia partecipativa in Italia: alcuni orientamenti.” Democrazia e diritto 3: 151–166.

- Allegretti, Umberto. 2013. “Recenti costituzioni ‘partecipate’: Islanda, Ecuador, Bolivia.” Quaderni costituzionali 3: 689–708.

- Alonso Perelló, Lluis D.L. 2006. El proceso participativo para la reforma del Estatuto de Autonomía de Cataluña. Colección Participación Ciudadana 1. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya, Department de Relacions Institucionals i Participació.

- Bächtiger, André, John S. Dryzek, Jane J. Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren. 2018. The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford Handbooks Online: Political Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bergsson, Baldvin T., and Paul Blokker. 2013. “The Constitutional Experiment in Iceland.” In Verfassungsgebung in Konsolidierten Demokratien: Neubeginn Oder Verfall Eines Systems?, edited by Kalman Pocza, 1–16. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Blokker, Paul. 2017. “The Romanian Constitution and Civic Engagement.” ICL Journal 11 (3): 437–455.

- Blount, Justin. 2014. “Participation in Constitutional Design.” In Comparative Constitutional law, edited by Rosalind Dixon and Tom Ginsburg, 38–56. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bohman, James. 1998. “The Coming Age of Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Political Philosophy 6 (4): 400–425.

- Brunazzo, Marco. 2017. “Istituzionalizzare la partecipazione? Le leggi sulla partecipazione in Italia.” Le Istituzioni del Federalismo 3: 837–864.

- Burgess, Michael, and Alan G. Tarr. 2012. “Introduction: Sub-National Constitutionalism and Constitutional Development.” In Constitutional Dynamics in Federal Systems: Sub-National Perspectives, edited by Michael Burgess and G. A. Tarr, 1–39. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Caluwaerts, Didier, and Min Reuchamps. 2018. The Legitimacy of Citizen-led Deliberative Democracy: The G1000 in Belgium, edited by Didier Caluwaerts and Min Reuchamps, 1st ed. Democratization Studies. London: Routledge.

- Carlà, Andrea. 2007. “Living Apart in the Same Room: Analysis of the Management of Linguistic Diversity in Bolzano.” Ethnopolitics 6 (2): 285–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17449050701345041.

- Casamiglia, Alberto. 1999. “Constitucionalismo y democracia.” In Democracia deliberativa y derechos humanos, edited by Harold Hongju Koh and Ronald Slye, 165–172. Barcelona: Gedisa.

- Chambers, Simone. 2003. “Deliberative Democratic Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 6: 307–326.

- Chambers, Simone. 2019. “Democracy and Constitutional Reform: Deliberative Versus Populist Constitutionalism.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 45 (9-10): 1116–1131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453719872294.

- Choudhry, Sujit, and Mark Tushnet. 2020. “Participatory Constitution-Making: Introduction.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 18 (1): 173–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moaa014.

- Cosulich, Matteo. 2016. “Uno Statuto per due Province. Considerazioni in margine all’avvio del procedimento di revisione dello Statuto speciale della Regione Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol.” Amministrazione in Cammino, 1–11.

- Cosulich, Matteo. 2018. “La Consulta per lo Statuto Speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol: una visione largamente condivisa del futuro dell’autonomia Trentina.” Osservatorio sulle fonti 3: 1–16.

- Dryzek, John S. 2016. “Deliberative Democracy in Divided Societies.” Political Theory 33 (2): 218–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591704268372.

- Elster, Jon, ed. 1998. Deliberative democracy. Vol. 1. Cambridge Studies in the Theory of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175005.

- Elstub, Stephen, and Oliver Escobar. 2017. “Forms of Mini-Publics: An Introduction to Deliberative Innovations in Democratic Practice.” Research and Development Note – New Democracy 4. https://www.newdemocracy.com.au/2017/05/08/forms-of-mini-publics/.

- Elstub, Stephen, and Oliver Escobar. 2019. “Defining and Typologising Democratic Innovations.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by Stephen Elstub and Oliver Escobar, 11–31. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Elstub, Stephen, and Peter McLaverty. 2014. Deliberative Democracy: Issues and Cases, edited by Stephen Elstub and Peter McLaverty. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Farrell, David M., Harris Clodagh, and Jane Suiter. 2017. “Bringing People into the Heart of Constitutional Design: The Irish Constitutional Convention of 2012–14.” In Participatory Constitutional Change, edited by Contiades Xenophon, and Alkmene Fotiadou, 120–136. London: Routledge.

- Farrell, David M., Jane Suiter, and Clodagh Harris. 2018. “‘Systematizing’ Constitutional Deliberation: The 2016–18 Citizens’ Assembly in Ireland.” Irish Political Studies 34 (1): 113–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2018.1534832.

- Ferrajoli, Luigi. 2012. “La democrazia costituzionale.” Revus, Journal for Constitutional Theory and Philosophy of Law 18: 69–12.

- Fiket, Irena, Espen D. H. Olsen, and Hans-Jörg Trenz. 2014. “Confronting European Diversity: Deliberation in a Transnational and Pluri-Lingual Setting.” Javnost – The Public 21 (2): 57–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2014.11009145.

- Fischer, Frank. 2009. Democracy and Expertise: Reorienting Policy Inquiry, edited by Frank Fischer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Font, Joan, Sara Pasadas del Amo, and Graham Smith. 2016. “Tracing the Impact of Proposals from Participatory Processes: Methodological Challenges and Substantive Lessons.” Journal of Public Deliberation 12 (1): 1–25.

- Fraenkel-Haeberle, Cristina. 2008. “Linguistic Rights and the Use of Language.” In Tolerance Through Law: Self Governance and Group Rights in South Tyrol, edited by Jens Woelk, Francesco Palermo, and Joseph Marko, 259–276. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Frosini, Tommaso E. 1997. Sovranità popolare e costituzionalismo. Milano: Giuffrè.

- Geissel, Brigitte, and Sergiu Gherghina. 2016. “Constitutional Deliberative Democracy and Democratic Innovations.” In Constitutional Deliberative Democracy in Europe, edited by Min Reuchamps and Jane Suiter, 75–92. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Gerring, John. 2013. The Case Study: What It Is and What It Does. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science: Oxford University Press.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, Monika Mokre, and Sergiu Miscoiu. 2020. “Introduction: Democratic Deliberation and Under-Represented Groups.” Political Studies Review 11 (1): 159–163.

- Ginsburg, Tom, Justin Blount, and Zachary Elkins. 2008. “The Citizen as Founder: Public Participation in Constitutional Approval.” Temple Law Review 81 (2): 361–382.

- Ginsburg, Tom, and Eric Posner. 2010. “Subconstitutionalism.” Stanford Law Review 62: 1583–1628.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis F. Thompson. 2004. Why deliberative democracy? Princeton paperbacks. Princeton: Princeton University Press. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10284143.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Translated by Jürgen Habermas, Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge, MA:. MIT Press.

- Happacher, Esther. 2017. “La convenzione per l’autonomia: spunti per un’autonomia dinamica e partecipata dell’Alto Adige/Südtirol.” Osservatorio sulle fonti 3: 1–14.

- Harmen, Binnema, and Ank Michels. 2021. “Does Democratic Innovation Reduce Bias? The G1000 as a New Form of Local Citizen Participation.” International Journal of Public Administration 44: 1–11.

- Hartz-Karp, Janette, and Michael Briand. 2009. “Institutionalizing Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Public Affairs 9: 125–141.

- Jacobs, Daan, and Wesley Kaufmann. 2021. “The Right Kind of Participation? The Effect of a Deliberative Mini-Public on the Perceived Legitimacy of Public Decision-Making.” Public Management Review 23 (1): 91–111.

- Kontiadēs, Xenophōn I., and Alkmene Fotiadou, eds. 2018. Participatory Constitutional Change: The People as Amenders of the Constitution. First issued in paperback. Comparative Constitutional Change. London: Routledge.

- Landemore, Hélène. 2020. “When Public Participation Matters: The 2010–2013 Icelandic Constitutional Process.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 18 (1): 179–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moaa004.

- Larin, Stephen J., and Marc Röggla. 2019. “Participatory Consociationalism? No, but South Tyrol’s Autonomy Convention is Evidence That Power-Sharing Can Transform Conflicts.” Nations and Nationalism 25 (3): 1018–1041. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12478.

- Levy, Ron, ed. 2018. The Cambridge Handbook of Deliberative Constitutionalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108289474.

- Levy, Ron. 2019. “Democratic Innovation in Constitutional Reform.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by Stephen Elstub and Oliver Escobar, 339–353. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lewanski, Rodolfo. 2013. “The Challenges of Institutionalizing Deliberative Democracy: The ‘Tuscany Laboratory’.” Journal of Public Deliberation 9 (1): 1–18.

- Lewansky, Rodolfo. 2013. “Institutionalizing Deliberative Democracy: the ‘Tuscany Laboratory’.” Journal of Public Deliberation 9 (1): 1–18.

- Lightbody, Ruth, and Jennifer J. Roberts. 2019. “Experts: The Politics of Evidence and Expertise in Democratic Innovation.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by Stephen Elstub and Oliver Escobar, 225–240. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Anne Norton. 2017. “Inequality is Always in the Room: Language & Power in Deliberative Democracy.” Daedalus 146 (3): 64–76.

- Markusse, Jan D. 1997. “Power-sharing and ‘Consociational Democracy’ in South Tyrol.” GeoJournal 43 (1): 77–89.

- Marshfield, Jonathan L. 2011. “Models of Subnational Constitutionalism.” Penn State Law Review 115 (4): 1152–1198.

- Martí, José L. 2017. “Pluralism and Consensus in Deliberative Democracy.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 20 (5): 556–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2017.1328089.

- Mazur-Kumric, Nives. 2009. “Legal Status of the German Language Group in the Italian Province of South Tyrol.” Pravani Vjesnik 25 (3/4): 25–44.

- Murphy, Jennifer. 2018. “Il gemello “diverso”: la Consulta per la riforma dello Statuto in Trentino.” Politika 2018: Südtiroler Jahrbuch für Politik 1: 88–96.

- Negretto, Gabriel. 2020. “Constitution-making and Liberal Democracy: The Role of Citizens and Representative Elites.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 18 (1): 206–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moaa003.

- Offe, Claus. 2011. “Crisis and Innovation of Liberal Democracy: Can Deliberation be Institutionalized.” Czech Sociological Review 47 (3): 447–472.

- O’Leary, Brendan. 2005. “Debating Consociational Politics: Normative and Explanatory Arguments.” In From Power Sharing to Democracy: Post-Conflict Institutions in Ethnically Divided Societies, edited by S. J. R. Noel, 3–43. Vol. 2. Studies in Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict. Montréal: McGill University Press.

- Oliveira, Waidd F. d. 2014. Constituição e democracia participativa: A questão dos orçamentos públicos e os conselhos de direitos e garantias. Belo Horizonte: D’Plácido Editora.

- Owen, Harrison H. 1997. Expanding Our Now. The Story of Open Space Technology. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=793704.

- Palermo, Francesco. 2008. “Implementation and Amendment of the Autonomy Statute.” In Tolerance Through Law: Self Governance and Group Rights in South Tyrol, edited by Jens Woelk, Francesco Palermo, and Joseph Marko, 143–160. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Palermo, Francesco. 2015a. “Autonomy and Asymmetry in the Italian Legal System: The Case of the Autonomous Province Bolzano/Bozen.” In Principles and Practices of Fiscal Autonomy: Experiences, Debates and Prospects, edited by Giancarlo Pola, 227–241. Federalism Studies. Surrey: Ashgate.

- Palermo, Francesco. 2015b. “Participation, Federalism and Pluralism: Challenges to Decision-Making and Responses by Constitutionalism.” In Citizen Participation in Multi-Level Democracies, edited by Cristina Fraenkel-Haeberle, Sabine Kropp, Francesco Palermo, and Karl-Peter Sommermann, 31–47. Studies in Territorial and Cultural Diversity Governance. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

- Pallaver, Günther. 2008. “South Tyrol’s Consociational Democracy: Between Political Claim and Social Reality.” In Tolerance Through Law: Self Governance and Group Rights in South Tyrol, edited by Jens Woelk, Francesco Palermo, and Joseph Marko, 303–327. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Papadopoulos, Yannis, and Philippe Warin. 2007. “Are Innovative, Participatory and Deliberative Procedures in Policy Making Democratic and Effective?” European Journal of Political Research 46: 445–472.

- Penasa, Simone. 2014. “From Protection to Empowerment Through Participation: The Case of Trentino – A Laboratory for Small Groups.” Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe 13 (2): 30–53.

- Poggio, Barbara, and Anna Simonati. 2018. “La Consulta trentina per la riforma dello Statuto regionale ed il processo partecipativo.” Politika 2018: Südtiroler Jahrbuch für Politik 1: 149–160.

- Przeworski, Adam, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin. 2009. Democracy, Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge Studies in the Theory of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ravazzi, Stefania. 2016. “When a Government Attempts to Institutionalize and Regulate Deliberative Democracy: The how and why from a Process-Tracing Perspective.” Critical Policy Studies 11 (1): 79–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2016.1159139.

- Rawls, John. 2005. Political Liberalism. Expanded ed. Columbia Classics in Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Reuchamps, Min, and Aleksi Eerola. 2016. “Constitutional Modernisation and Deliberative Democracy: A Political Science Assessment of Four Cases.” Revue interdisciplinaire d’études juridiques 77 (2): 319–366.

- Reuchamps, Min, Marine Kravagna, and Benjamin Biard. 2014. “Avant-propos.” Revue internationale de politique comparée 21 (4): 7–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/ripc.214.0007.

- Reuchamps, Min, and Jane Suiter. 2016. “A Constitutional Turn for Deliberative Democracy in Europe?” In Constitutional Deliberative Democracy in Europe, edited by Min Reuchamps and Jane Suiter, 1–13. ECPR – Studies in European Political Science. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Röggla, Marc. 2018. “Der Autonomiekonvent und die Rolle der Medien: Die Dauerbrenner der Berichterstattung und deren Auswirkungen auf den Prozess.” 115–134.

- Rose, Jonathan. 2007. “The Ontario Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform.” Canadian Parliamentary Review 30 (3): 9–16.

- Rosini, Monica. 2015. “Il processo di adeguamento degli Statuti speciali si rimette in moto? La convenzione sull’Alto Adige/ Südtirol.” Osservatorio Sulle Fonti 2: 1–11.

- Saati, Abrak. 2019. Participatory Constitution-Making as a Transnational Legal Norm: Why Does It “Stick” in Some Contexts and Not in Others? Constitution-Making and Transnational Legal Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saunders, Cheryl. 2012. “Constitution-making in the 21st Century.” International Review of Law 4: 1–18.

- Setälä, Maija. 2017. “Connecting Deliberative Mini-Publics to Representative Decision Making.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (4): 846–863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12207.

- Smith, Graham. 2012. “Deliberative Democracy and Mini-Publics.” In Evaluating Democratic Innovations: Curing the Democratic Malaise?, edited by Brigitte Geissel and Kenneth Newton, 90–111. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, Graham. 2018. “The Institutionalization of Deliberative Democracy: Democratic Innovations and the Deliberative System.” Journal of Zhejiang University 4 (2): 5–18.

- Snider, J. H. 2008. “Designing Deliberative Democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly.” Journal of Public Deliberation 4 (1): Article 11.

- Soto Barrientos, Francisco. 2017. Los “diálogos ciudadanos”: Chile ante el giro deliberativo. Primera edición. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas. Política. Santiago Chile: LOM ediciones.

- Suteu, Silvia. 2015. “Constitutional Conventions in the Digital Era: Lessons from Iceland and Ireland.” Boston College International and Comparative Law Review 3 (2): 251–276.

- Thorarensen, Björg. 2017. “The People’s Contribution to Constitutional Changes. Writing, Advising or Approving? – Lessons from Iceland.” In Contiades and Fotiadou, 103–119.

- Tofigh, Maboudi. 2020. “Participation, Inclusion, and the Democratic Content of Constitutions.” Studies in Comparative International Development 55 (1): 48–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-019-09298-x.

- Valastro, Alessandra. 2011. “La democrazia partecipativa come metodo di governo: diritti, responsabilità, garanzie.” In Per governare insieme, il federalismo come metodo di governo: Verso nuove forme della democrazia, edited by Gregorio Arena and Fulvio Cortese, 159–188. Vol. 94. Diparmento di scienza giuridiche, Università di Trento. Milano: CEDAM.

- Warren, Mark E. ed. 2014. “Institutionalizing Deliberative Democracy.” In Deliberation, Participation and Democracy: Can the People Govern?, edited by Shawn W. Rosenberg, 272–288. [Place of publication not identified]: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Warren, Mark, and Hilary Pearse. 2008. Designing Deliberative Democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly. Theories of Institutional Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wheatley, S. 2003. “Deliberative Democracy and Minorities.” European Journal of International Law 14 (3): 507–527. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/14.3.507.