Abstract

South East European countries are pursuing their way towards EU accession which involves the adoption of EU laws, standards, and policy approaches. This process of policy alignment faces a local institutional environment marked by existing institutional asymmetries between formal and informal institutions, often based on institutional voids. In this article, we examine the conditions for introducing the EU’s smart specialization approach to a context marked by institutional voids and asymmetries. We understand the institutional environment of South East European countries as low-coordination economies marked by low degrees of cooperation and trust. In such an environment, a participatory policymaking approach such as smart specialization can serve to mitigate institutional asymmetries but is likely to face major challenges, leading to an institutional smart specialization paradox that is exacerbated by the absence of an ex-ante conditionality. To explore these challenges, we examine institutional voids and asymmetries relevant for innovation policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, based on a series of interviews with firms and intermediary organizations and an inductive research design inspired by grounded theory. Drawing on the results, we offer conclusions and policy recommendations for the upcoming introduction of smart specialization to Bosnia and Herzegovina and other EU enlargement countries.

Introduction

South East Europe has the prospect of further integration into the European Union (EU) as all Western Balkan economies are considered either candidate countries or potential candidates (European Commission Citationn.d.). Part of this process is aligning national laws and regulations with the EU acquis communautaire (Dyker and Radosevic Citation2001). Such a long-term process of institutional change can be expected to face considerable difficulties in an institutional context (Glückler and Bathelt Citation2017; Glückler Citation2020) that suffers from significant inconsistencies and could further exacerbate them. The introduction of the smart specialization approach (S3) known from EU cohesion policy to the Western Balkans offers an example for alignment with EU policies in the field of innovation and competitiveness that can be expected to affect the institutional context in which firms operate but also on which they depend. The introduction of this approach provides an interesting case to study these institutional patterns not only because of its role in the path of the Western Balkans towards EU integration but also due to its fundamentally participatory nature which can possibly serve to reduce institutional asymmetries and ensure a degree of alignment between formal and informal institutions.

In this article, we focus on Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) which exhibits a particularly severe set of institutional difficulties due to its complex and inert political system in an environment marked by dissatisfaction among the population with slow economic and political development (Dzihic and Wieser Citation2008) that may be difficult to achieve under existing and possibly widening institutional asymmetries. The case of BiH elucidates the difficulties EU alignment through the introduction of the S3 approach is likely to encounter considering the prevailing informal institutional environment in BiH.

To understand the institutional voids and asymmetries prevalent in the economy of BiH, this article explores how an upcoming smart specialization process could contribute to reducing institutional asymmetries by leading to innovation and competitiveness policies better adapted to the informal institutional environment and by establishing routines of cooperation among firms, intermediaries, and government.

Our research contributes to the literature by providing a detailed insight into a very complex institutional setting in times of institutional change. We find evidence that significant existing institutional voids and asymmetries exist in BiH but are not sufficiently well understood in the context of EU integration. While we assume that smart specialization can contribute to aligning institutional settings in times of fundamental change, we argue that the process to introduce the approach in particular needs to take path-dependent informal institutions (Gherhes, Vorley, and Williams Citation2018; Martin Citation2000; Martin and Sunley Citation2006) into account and requires careful preparation to confront the institutional challenges involved.

The article starts with a literature review on institutions, institutional voids, and institutional asymmetries before detailing our methodological approach. The article goes on to introduce smart specialization and its role in institutional change before turning to the current institutional context found in Western Balkan economies aligning their legislation and policies to the EU’s acquis communautaire. We synthesize our conceptual considerations into a framework to grasp institutional voids and asymmetries in a low-coordination economy (Benner Citation2019a) and explore them through a series of qualitative interviews in BiH before drawing conclusions for the introduction of smart specialization to the country.

Literature review

In this part, we explain the main theoretical aspects in the focus of this article and identify basic concepts related to institutions, institutional voids and asymmetries, and smart specialization. Drawing on this diverse literature review enables us to highlight the arena for institutional change in South East Europe.

Institutions, institutional voids, and institutional asymmetries

The insight that institutions condition economic development and, more specifically, dynamic processes such as innovation (Essletzbichler and Rigby Citation2007; Glückler and Bathelt Citation2017; Glückler Citation2020), is widely acknowledged (e.g. Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Gertler Citation2010; Martin Citation2000; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013; Citation2020; Rodríguez-Pose and Storper Citation2006), building on Polanyi’s (Citation1944) argument that markets are social systems that are defined by institutions (Gertler Citation2010; Mair and Marti Citation2009; Mair, Marti, and Ventresca Citation2012). However, the precise role of institutions in economic development, or its lack, is not yet firmly understood, and a certain conceptual ambiguity and vagueness seems to be among the causes of this limited understanding (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Martin Citation2000; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013; Citation2020).

Scott (Citation2014, 57) understands institutions as ‘multifaceted, durable social structures’ that include ‘regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive elements’. For Hall and Thelen (Citation2009, 9), institutions are ‘sets of regularized practices with a rule-like quality’. Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014, 346) use a similar but narrow definition of institutions as ‘stable patterns of social practice based on mutual expectations’. One of the simplest definitions, the one by North (Citation1990, 3) who defined institutions simply as ‘rules of the game’, is among the most fitting. These rules bifurcate into formal institutions such as laws and regulations on the one hand and informal institutions, i.e. unwritten rules or social norms governing society, on the other hand (North Citation1990). These informal institutions are endogenous phenomena rooted in the path-dependent evolution of a national or regional economy (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Martin Citation2000; Martin and Sunley Citation2006), possibly even to the degree of ‘institutional hysteresis’ (Setterfield Citation1993; see also Gherhes, Vorley, and Williams Citation2018), and often reproduced through tacit knowledge (North Citation1990).

Formal institutions, at least in theory, are easy to establish and change. For example, new laws, regulations, policies, or strategies can be written and legislated in a fairly short time and do not necessarily exhibit the same degree of inertia than do highly path-dependent and context-specific informal institutions (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Essletzbichler and Rigby Citation2007; Martin Citation2000; Martin and Sunley Citation2006). If formal institutions change abruptly, they can meet a landscape of stable and inert informal institutions since changes in informal institutions take more time to change as they involve changes in values, underlying understandings, and behavior and are likely to be gradual and slow (Estrin and Mickiewicz Citation2011; Gherhes, Vorley, and Williams Citation2018; North Citation1990; Williamson Citation2000). Formal institutions can become habitualized and thus mirrored in informal institutions, but this process is far from inevitable (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014). Formal institutions serve as complements to informal institutions but will almost always be incomplete since no law or contract can stipulate every thinkable way it might be applied (Grossman and Hart Citation1986; Williamson Citation1975; Citation2000). Hence, a formal institution is only as effective as the social norms, or informal institutions, of its environment allow (North Citation1990; Williamson Citation2000). As Glückler and Lenz (Citation2016) argue, the interactions between formal and informal institutions can take different and not perfectly predictable relationships of circumvention, competition, reinforcement, or substitution that affect or even constrain the intended effectiveness of laws or regulations (see also Glückler Citation2020). Further, as Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005) highlight, formal institutions can over time change their function through gradual processes of institutional change such as displacement, layering, drift, conversion, or exhaustion. What becomes clear from this discussion is that formal and informal institutions are related in complex ways and that the institutional context (Glückler and Bathelt Citation2017; Glückler Citation2020) of a national or regional economy can be messy. Therefore, while long-term patterns of sustained economic development may to a considerable degree hinge on the coherence or complementarity of institutions with each other (Boyer Citation2005), the institutional context of transition and emerging economies can be expected to suffer from inconsistencies between institutions that constrain dynamic processes of economic development such as innovation or entrepreneurship (see also Rodríguez-Pose and Storper Citation2006).

Current research on institutional contexts in transition and emerging economies ranges from a discussion of formal institutions in transition economies and their influence on businesses (Rodrigues Citation2013; Puffer, McCarthy, and Boisot Citation2009; Meyer and Peng Citation2005) and few studies addressing informal institutions in transition economies (e.g. Chakrabarty Citation2009) to the analysis of institutional voids, i.e. areas where institutions are missing or deficient (Alshbili, Elamer, and Moustafa Citation2021; Doh et al. Citation2017; Heeks et al. Citation2021; Khanna Citation2002; Khanna and Palepu Citation1997; Citation2000; Ma, Yao, and Xi Citation2007; Mair, Marti, and Ventresca Citation2012; Mair and Marti Citation2009; Rodrigues Citation2013; Schrammel Citation2013). Under institutional voids, ‘institutional arrangements that support markets are absent, weak, or fail to accomplish the role expected’ (Mair and Marti Citation2009, 419). There is a body of literature that discusses how to bridge these missing institutions (Konstantynova and Lehmann Citation2017; Lehmann and Benner Citation2015; Schrammel Citation2014). While institutional voids can relate to formal institutions as is the case, for example, when contract enforcement mechanisms are deficient (Lehmann and Benner Citation2015), voids on the level of informal institutions can include low trust and reputation and limited cooperation routines that are characteristic for what Benner (Citation2019a, 1794) calls ‘low-coordination economies’ in contrast to ‘high-coordination economies’. These two types differ in their institutional and organizational thickness (Amin and Thrift Citation1994; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020; Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017; see also Martin Citation2000) as high-coordination economies are rife with corporatist forms of economic coordination guided by efficient intermediary organizations and a considerable degree of trust and cooperation, while low-coordination economies lack these features and are marked by hierarchical policymaking and distrust, notably between the public and private sector (Benner Citation2019a).

Going further, institutional voids cannot be viewed in isolation because of their role in the wider institutional context. Institutions are not simply ‘missing’ but if weak or deficient may not match with other parts of the institutional context, thus constraining institutional coherence or complementarity (Boyer Citation2005). These mismatches have been conceptualized as ‘institutional asymmetries’ (Williams, Vorley, and Williams Citation2017). Under such an asymmetry between formal and informal institutions, relationships of competition or substitution and possibly circumvention (Glückler and Lenz Citation2016) are likely. Consequently, institutional asymmetries can act as an incentive for actors such as entrepreneurs or innovators to engage in informal practices (Williams and Franic Citation2016; Williams, Horodnic, and Windebank Citation2015) such as envelope wages (Williams and Horodnic Citation2015a; Citation2015b; Citation2016b) and informal payments for health services (Horodnic and Williams Citation2018; Williams and Horodnic Citation2017; Citation2018).

A number of studies discuss how institutional asymmetries affect transition economies (Williams and Vorley Citation2015a; Williams et al. Citation2017) and other regions in Europe (Williams and Vorley Citation2015b; Gherhes, Vorley, and Williams Citation2018). For example, Williams and Vorley (Citation2015a) demonstrate that in Bulgaria, the change of informal institutions trails the rapid implementation of new formal institutions. As these studies focus on discussing ‘supportive’ institutional environments for entrepreneurship, they tend to characterize the informal institutions as hindering or ‘unsupportive’ (e.g. Williams and Vorley Citation2015a, 841).

In a more neutral understanding of institutional environments based on North (Citation1990) and Williamson (Citation2000) and acknowledging the existence of institutional inertia (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Essletzbichler and Rigby Citation2007; Martin Citation2000; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013), informal institutions can be seen as important elements of the fairly stable context in which economic action is embedded (Granovetter Citation1985; see also Martin Citation2000). Hence, instead of regarding informal institutions as ‘unsupportive’, the formal institutional environment may simply not suit the specific local context (see also Glückler and Lenz Citation2016). Consequently, when moving to policy design and implementation, questions of institutional (in)consistency and change have to be addressed on the level of formal institutions and possibilities for ‘institutional leapfrogging’ on the level of informal institutions have to be examined (Benner Citation2019a). By stimulating changes on the level of informal institutions in collective processes of public-private cooperation and through actors building patterns of trust, reputation, and cooperation (Benner Citation2019a), institutional leapfrogging can reduce institutional asymmetries by fostering informal institutions that match the assumptions formal institutions are based on. Another way to reduce institutional asymmetries is by explicitly designing policies aimed at changing informal institutions in the long term to the degree possible (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013). Both ways of reducing institutional asymmetries, including by bridging institutional voids, are relevant under the smart specialization approach applied under the EU cohesion policy (Benner Citation2019a).

Smart specialization and institutional asymmetries

In line with the global discourse on the ‘knowledge-based economy’ (OECD Citation1996), high attention is paid to policies that aim at promoting innovation (Pfotenhauer, Juhl, and Aarden Citation2019). In what Schot and Steinmueller (Citation2018) understand as the second frame of innovation policy focusing on national or regional innovation systems, developing tailor-made innovation policies that do not follow a ‘one size fits all’ logic has been suggested (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2005).

The smart specialization approach (Foray and Van Ark Citation2007; Foray, David, and Hall Citation2009; Foray et al. Citation2012), often abbreviated ‘S3’, is among the policy approaches meant to stimulate the development of tailor-made innovation policies. Given that the EU made the approach mandatory for innovation funding through its cohesion policy under an ex-ante conditionalityFootnote1 from 2014 on (Radosevic Citation2017), the approach represents ‘the biggest ongoing innovation policy experiment in the EU, if not in the world’ (Radosevic Citation2017, 30). Under smart specialization, regions or (smaller) countries are expected to focus cohesion policy funds on a limited number of priorities through a smart specialization strategy (Gianelle et al. Citation2020). Somewhat contrary to the term smart specialization, the approach actually seeks economic diversification (Asheim Citation2019; Foray Citation2019; Hassink and Gong Citation2019). A smart specialization strategy and, hence, the definition of priorities is meant to occur in a collective process called entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) and the EU’s smart specialization guide provides an elaborate toolbox for how to do so (Foray et al. Citation2012). In this process, a wide range of actors from across the economy such as government representatives, firms, associations and chambers of commerce participate and set priorities according to their growth potential (Foray Citation2012; Citation2017; Foray, David, and Hall Citation2009; Foray et al. Citation2012; Gianelle et al. Citation2020; McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015; Radosevic Citation2017).

The idea of a collective EDP derives from the debate on new industrial policies and particularly from Hausmann and Rodrik’s (Citation2003) idea of self-discovery (Foray Citation2017; Gianelle et al. Citation2020; Martínez-López and Palazuelos-Martínez Citation2019; Radosevic Citation2017). Probably even more than the eventual strategy, the EDP is the centerpiece of smart specialization. Evidence from EU regions and countries shows that the process itself can lead to improvements in governance (Kroll Citation2015) and in informal institutions such as trust, reputation, and a spirit of cooperation through institutional leapfrogging (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c; see also Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020). However, the process faces obstacles such as limited administrative capacities, top-down policymaking legacies, problems in intra-governmental coordination, or low trust between the private and public sectors (Capello and Kroll Citation2016; Karo, Kattel, and Cepilovs Citation2017; Kroll Citation2015; Kyriakou Citation2016; Papamichail, Rosiello, and Wield Citation2019; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020). However, higher-level formal institutions such as the ex-ante conditionality seem to help in getting the process started and in stimulating institutional leapfrogging in low-coordination economies (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c).

Drawing on the institutional functions of the EDP, is seems plausible to assume that the EDP provides an opportunity to overcome institutional asymmetries. If policymakers and other public-sector actors who shape the formal institutions guiding economic development and private-sector firms who shape informal institutions engage in a joint prioritization process, we might expect the process to achieve some convergence between formal and informal institutions. This proposition is based on several considerations (see also Benner Citation2019a):

First, the eventual smart specialization strategy summarizing the results of the EDP in terms of priorities and intervention areas can lead to changes in formal institutions if and where necessary, thus possibly bridging institutional voids.

Second, changes in informal institutions such as the build-up of trust, reputation, or cooperation routines during the EDP may conform to the policy goals defined in the smart specialization strategy and to policies foreseen in the strategy, e.g. support to university-industry collaboration or cluster promotion.

Third, firms articulating their needs in terms of the formal institutional environment can increase policy attention to addressing these needs under the umbrella of the smart specialization strategy and eventual implementation.

However, the preconditions and outcomes of the EDP are likely to vary between high-coordination and low-coordination economies. Still, even under the unfavorable conditions found in low-coordination economies, the EDP can lead to institutional leapfrogging through cooperation during the EDP and intermediary organizations functioning as ‘relational brokers’ (Benner Citation2019a, 1807). Institutional leapfrogging can fill institutional voids on the level of informal institutions in what Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014) describe as upward causation of institutional change (see also Glückler and Lenz Citation2016). Still, there is a quandary for low-coordination economies because by definition they are lacking institutional and organizational thickness and only few intermediary organizations will be capable of assuming a brokerage role effectively (Benner Citation2019a).

South East Europe as an arena for institutional change

Among South East European countries, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania and Slovenia have become EU member states and the six Western Balkan economies are moving closer to the EU as candidate countries or potential candidates for accession (European Commission Citationn.d.). Part of this process is integrating laws and regulations of the EU’s acquis communautaire (Dyker and Radosevic Citation2001) into Western Balkan economies’ own national legal framework. These laws and regulations aligned with the acquis communautaire are formal institutions of the institutional framework in a country and, to the degree that they are newly established, can bridge institutional voids. Even though accession countries have a certain degree of leeway in how precisely to align their legal framework with the EU’s acquis communautaire, how well these newly created or modified formal institutions match pre-existing informal institutions defines whether long-term institutional asymmetries are closed or new ones are created.

Given the evidence for institutional voids (e.g. Lehmann and Benner Citation2015; Schrammel Citation2013) and institutional asymmetries (e.g. Williams and Vorley Citation2015a; Williams and Krasniqi Citation2018; Williams, Vorley, and Williams Citation2017) in South East Europe, it seems reasonable to assume that the institutional context for innovation found in South East European countries characterizes them as low-coordination economies, as the cases of Slovenia and Croatia show (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c).

Currently, the smart specialization approach is introduced to the Western Balkans with technical assistance from the European Commission, with Montenegro having been the first Western Balkan economy with a smart specialization strategy (Benner Citation2019b; Matusiak and Kleibrink Citation2018; Radovanovic and Benner Citation2019). While the ex-ante conditionality does not apply to non-EU member states, candidates for EU accession are still encouraged to introduce the approach in view of eventual EU accession. For example, the Commission’s 2020 progress report for Bosnia and Herzegovina explicitly calls for the country to ‘develop and adopt a smart specialisation strategy’ (European Commission Citation2020, 96). Given the multiplicity of sectoral strategies and policies relevant for innovation in the Western Balkans (Radovanovic and Benner Citation2019), it seems plausible to assume a certain degree of complexity and inconsistency in the formal institutional environment that a smart specialization exercise could address, as well as low degrees of trust, reputation, and cooperation that can be expected from the experiences Croatia and Slovenia made during their smart specialization processes (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c). Taken together, these insights imply that the introduction of smart specialization to the Western Balkans faces institutional asymmetries. At the same time, the approach could unfold its possible effects in shaping the institutional context (Benner Citation2019a; Kroll Citation2015; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020). Since in the Western Balkans the smart specialization approach is implemented not under the framework of EU cohesion policy but as a national-level exercise of innovation policy, smart specialization strategies could play a considerable role in defining the formal institutional setup for promoting innovation and entrepreneurship. Hence, smart specialization strategies in the Western Balkans could contribute to bridging institutional asymmetries by better adapting the formal institutional environment in relevant fields to the informal institutional environment, but to what degree this will be achievable is an open question. According to Benner (Citation2019a), the EDP can lead to changes in the informal institutional environment through institutional leapfrogging but these changes are gradual and fragile and suffer from a certain circularity because building up trust and cooperation are both a prerequisite and a possible outcome of the EDP. The higher-level formal institution of the ex-ante conditionality and the informal institution of credibility it unfolds provides a solution to this circular dilemma (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c) that does not apply to the Western Balkans prior to EU accession. Since Eastern European transition economies with their legacies of hierarchical policymaking and distrust between the public and private sectors face peculiar difficulties in implementing the approach (Karo, Kattel, and Cepilovs Citation2017), how to overcome the fundamental institutional asymmetry apparent in the circularity under the absence of an ex-ante conditionality is a crucial but open question.

Conceptual framework

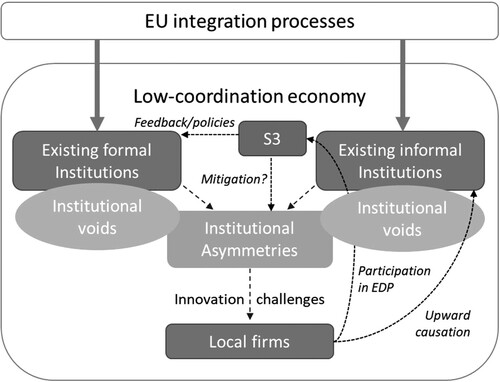

Our conceptual framework focuses on the peculiar case of a low-coordination economy marked by institutional and organizational thickness (Amin and Thrift Citation1994; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020; Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017), distrust, and weaknesses in cooperation patterns and the tissue of intermediary organizations (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c). We propose that transition economies aspiring to join the EU as candidate countries or potential candidates are well represented by the stylized type of a low-coordination economy and thus are likely to exhibit significant institutional voids and asymmetries (e.g. Lehmann and Benner Citation2015; Schrammel Citation2014; Williams and Krasniqi Citation2018). Adding to pre-existing institutional voids, the EU integration process with its gradual alignment of national legislation to the acquis communautaire (Dyker and Radosevic Citation2001) can deepen institutional asymmetries or create new ones, leading to specific challenges for local firms. illustrates our conceptual framework.

As shows, S3 with its EDP might play a double role. First, by including local firms the EDP provides a participatory forum for firms to provide feedback about the innovation-related challenges emanating from institutional asymmetries to the policymaking process. Second, S3 could lead to a mitigation of institutional asymmetries by defining suitable policies in the resulting smart specialization strategy. Such policies could include, for instance, entrepreneurship education, capacity building or training measures to affect informal institutions (see also Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013; Citation2020), networking or cluster schemes to build trust, or strengthening intermediary organizations to broker trust between actors (Benner Citation2019a). Further and beyond the smart specialization strategy itself, firms’ feedback during the EDP could increase policymakers’ awareness for modifications on the level of formal institutions such as laws or regulations to counter the challenges to innovation firms face. As Benner (Citation2019a) shows, firms’ participation in the EDP can lead to the emergence of trust and reputation in cooperation through upward causation and, thus, institutional leapfrogging, though whether S3 does lead to a mitigation of institutional asymmetries is not certain and depends on policymakers’ awareness for institutional patterns and problems.

By using the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina which we understand as a low-coordination transition economy in the process of gradual EU integration, the remainder of this article inductively explores existing institutional voids and asymmetries relevant for innovation. The broad research question pursued is how smart specialization can contribute to mitigating institutional voids and asymmetries and how these voids and asymmetries impact the smart specialization process itself.

The case of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is an instructive case because of its complex political system with its implications for economic development. According to the 1995 Dayton peace agreement, the country is divided into two political entities along ethnic lines, the Bosnian-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the primarily Serb Republic of Srpska (with the multi-ethnic Brcko district as de facto third entity), and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into ten cantons, resulting in three levels of largely autonomous government in a small country with less than four million inhabitants (see also Belloni and Strazzari Citation2014; Divjak and Pugh Citation2008; Fagan and Dimitrova Citation2019; Padurariu Citation2014).

Bosnia and Herzegovina scores lower than neighboring countries such as Montenegro, North Macedonia, or Serbia on many dimensions measured by the OECD’s competitiveness outlook (OECD Citation2018). The World Bank’s ‘Doing Business’ report ranks Bosnia and Herzegovina 90th (of 190) worldwide, below its neighbors North Macedonia (17th), Serbia (44th), Montenegro (50th), Kosovo (57th), and Albania (82nd) (World Bank Citation2020).Footnote2 While these international benchmarking reports refer mostly to the formal institutional environment, the informal institutional environment is much more difficult to assess. This is why the case study addresses institutional asymmetries in BiH through exploratory qualitative research, starting from our proposition that BiH is a low-coordination economy with potentially significant institutional asymmetries.

As a potential candidate for EU accession (European Commission Citationn.d.), BiH is in the process of gradually preparing its accession process through formal institutional alignment with the EU’s legal and political frameworks. BiH is among the Western Balkan economies currently implementing the smart specialization approach under the European Commission’s smart specialization framework for enlargement and neighborhood countries (Matusiak and Kleibrink Citation2018; Radovanovic and Benner Citation2019). At the time of writing, the process was still in its initial steps (European Commission Citation2019; Citation2020).

The innovation policy context in BiH is marked by several partly overlapping initiatives, owing to the country’s three-level architecture of government, but also a number of sectoral strategies such as science, innovation, education, or information and communications technologies strategies, as the extensive policy mapping in the Western Balkans by Radovanovic and Benner (Citation2019) elucidates. Apart from these formal strategies, further policy practices relevant to innovation are likely to be found on all three levels of government, as are private-sector and donor-funded initiatives. Hence, a high complexity in the formal institutional environment becomes apparent that makes the prevalence of institutional asymmetries likely. These institutional asymmetries are what our exploratory research design aims at elucidating, as our methodology explains.

Methodology

Methodological considerations

We followed a qualitative approach similar to Gherhes, Vorley, and Williams (Citation2018) and Williams and Vorley (Citation2015a), based on semi-structured interviews. Even though qualitative research is often considered to lack generalizability (Silverman Citation2011; Doz Citation2011), existing institutional literature (e.g. Glückler Citation2020) shows that a qualitative approach provides a richer picture of the context and deeper insights into existing institutional asymmetries (Reay and Jones Citation2016).

Our empirical methodology was inspired by a grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967) but with significant adaptations. Responding to calls for researchers to reflect on the ontological and epistemological foundations of their study (e.g. Charmaz Citation1990; Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021; Howard-Payne Citation2016), we adopt a position of critical realism by assuming that the patterns we observe in the data bring us closer to understanding reality (Howard-Payne Citation2016; Sayer Citation1992; Citation2000). This perspective is consistent with grounded theory that is not set on a specific epistemology (Charmaz Citation2006) and seems sensible to us when studying institutions which we view as social structures that enable causal relationships in processes of social action. Still, our approach is sensitive to questions of interpretation and meaning which have a place in a critical-realist perspective (Sayer Citation1992; Citation2000).

We generally followed Charmaz’s (Citation2006) constructivist grounded theory approach, although with modifications. This approach seemed suitable to us because of its pragmatism and flexibility (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014) though our critical-realist perspective somewhat modifies its ontological and epistemological assumptions. We agree that grounded theory is a rather open process and abstain from Glaser’s positivistic understanding of relatively fixed guidelines on the grounded theory approach (Charmaz Citation1990; Citation2006). Furthermore, we agree with Glaser (Citation1992) and perceived axial coding, as suggested by Strauss and Corbin (Citation1990), as too rigid and imposing a structure and concepts on the data too early in the process. Nevertheless, we agree with Charmaz (Citation1990; Citation2006) that focused coding does not have to result in just one single category and that a researcher cannot start with a blank slate.

Our analysis relies on open, focused, and theoretical coding (Charmaz Citation1990; Citation2006), the latter by two independent researchers and following a constant comparative approach. We diverged from Charmaz’s (Citation2006) suggestion of extensive memoing and analyzing stages of the memos. We found memoing constraining as we could relate many statements individually to existing literature or concepts. In this sense, our research is driven more by critical realism (Sayer Citation1992; Citation2000) and pragmatism (Morgan Citation2014) than by Charmaz’s constructivist approach. Further, we did not strictly follow line-by-line coding (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021) that we found too limiting in some examples because we followed a context-sensitive approach (Gong and Hassink Citation2020; Morgan Citation2014) and context is often expressed in more elaborate statements than line-by-line coding allows.

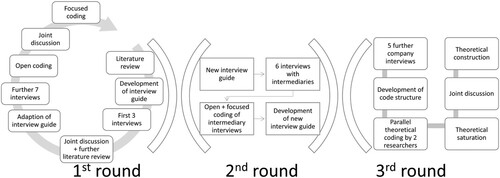

Despite our approach being based on pre-existing institutional theory, our research question narrowed down during open coding, similar to the approach followed by Howard-Payne (Citation2016), thus leaving room for emerging patterns in the sense advocated by Glaser and Holton (Citation2004). This openness enabled us to adapt our approach more towards grounded theory than we had originally planned. We had initially intended to follow a deductive approach by conducting a literature review, developing an interview guide, discussing and revising the interview guide, and planning a series of interviews. However, after the first couple of interviews it became evident that a purely linear and deductive approach was not suitable as too many unexpected issues came up in the interviews. Hence, we adopted a circular approach with constant interplay between data and literature. This circularity allowed for a continuous reflection on data and deeper understanding (Flick Citation2014). In the end we conducted three different rounds of interviews as laid out in .

Data collection and analysis

As displayed in , we collected data in three interview rounds. Most of the interviews were based on theoretical sampling while some subsequent interviews were based on ‘snowball’ sampling (Flick Citation2014, 162). The non-probability approach of theoretical sampling is an essential component of grounded theory and allows researchers to choose data that is perceived as most relevant to further inform on categories and codes (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967; Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014). For these reasons, our fist interview was not a representative of a firm but an EU integration expert who provided rich information on formal and informal constraints in BiH. Interviews two and three where based on snowball sampling which led to a halt in our interview process and made us realize that we needed to take a more open approach then initially expected. Interviews four to ten were based on theoretical sampling as we changed to conducting them in the local language to be able to rule out language and translation deficits. For each round of interviews we prepared a semi-structured interview guideline, respectively, with a number of questions that were used to guide the interviews where needed and served to prompt rich answers by interviewees while keeping the necessary openness (Flick Citation2014; Helfferich Citation2019).

After the first ten interviews we openly coded the material in several rounds followed by a joint discussion that inspired the focused coding (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014). Based on these coding rounds, we felt the need to engage in another round of interviews. These were theoretically sampled again, based on our wish to understand the innovation policy context from the perspective of intermediaries (including policy experts). These interviews were coded in a constant mixture of open and focused coding, based on the experience of the first round. After these two rounds, we felt more confident about our understanding of the context and, hence, were able to engage in theoretical coding with codes not driven by the data but influenced by ‘ideas and perspectives that researchers import to the research process as analytic tools and lenses from (…) a range of theories’ (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014, 159). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this final round of interviews was delayed and started in May 2020. During coding of the third round of interviews, 115 codes were generated and assigned to 324 segments. We had frequent discussions to compare and refine coding categories and schemes to ensure consistency. All interviews were coded by two independently working researchers, based on the code structure. To check intercoder reliability, Cohen's kappa (Landis and Koch Citation1977) was calculated in selective coding during the third round of interviews. The result for Cohen’s kappa was higher than 0.889, implying no significant differences between coders.

To collect data, we focused primarily on the canton of Sarajevo as far as feasible. Given the complex institutional context in BiH, focusing on one canton seemed sensible, although particularly in the case of intermediaries such a narrow spatial focus was not always possible to achieve. The research is based on a heterogeneous sample of interviewees coming from different sectors (information technologies, marketing, trade, tourism, production, consultancy, intermediary organizations) and included policy actors and cluster/network managers to allow us to capture a complex reality and to draw valid conclusions. lists the interviews conducted for all three rounds.

Table 1. List of interviews (source: authors’ elaboration).

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. The first three interviews were conducted by a German researcher with living and working experience in Bosnia and Herzegovina (T.L.). Further interviews were conducted by a researcher based in Sarajevo (A.K.). The second-round interviews were conducted by a third researcher (M.B.) who has a deep understanding of intermediaries, EU policy alignment, and innovation policy in the Western Balkans. The cooperation between several researchers from different backgrounds ensured a more transparent and discussion-based approach to our data (Sinkovics, Penz, and Ghauri Citation2008).

The data was coded with the help of a standard qualitative data analysis software, MaxQDA (Kuckartz and Rädiker Citation2019). The use of computer assisted qualitative data analysis software helps to make the data analysis process more structured and formalized and thus enhances reliability (Sinkovics, Penz, and Ghauri Citation2008). Our codes for the first and second round of interviews included attribute codes, descriptive coding, in-vivo coding, and partly also concept coding (for high- and low coordination) (Saldaña Citation2015).

displays the code structure of the first round of interviews after open and focused coding through MaxQDA’s code-matrix bowser. The size of the squares demonstrates the amount of codings in a document relative to all codings. Hence, serves as a first impression of the importance and possible bias between interviews within the codes. demonstrates that we received information on the general informal and formal institutional environment from the first interview with an EU integration expert. Furthermore, shows that several codes were addressed in almost all interviews, such as ‘importance of reputation/trust’, ‘low coordination’ and ‘not able to name asymmetry’. These findings are further explained in the results section.

Quality criteria and limitations

Qualitative research has been widely criticized for its lack of rigid procedures and its lack of generalizability (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021; Eisenhardt Citation1991; Eisenhardt, Graebner, and Sonenshein Citation2016; Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Acknowledging that criticism, we do not intend to claim generalizability but rather focus on contributing to theory development on participatory innovation policy processes in environments marked by institutional voids and asymmetries. We follow Charmaz and Thornberg’s (Citation2021) understanding that flexibility and method diversity are essential characteristics of grounded theory as well as the four quality criteria of credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness proposed by Charmaz (Citation2006) and Charmaz and Thornberg (Citation2021).

Credibility relates to the sufficiency of data and reflexivity of the researcher on his/her process (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021). While sufficiency of data is often a matter of judgment, we focused on getting a clear understanding of the larger picture by carrying out three independent interview rounds addressing different subquestions. Theoretical sampling was very helpful for doing so, and our approach achieved theoretical saturation for all three individual interview rounds. One limitation is that we applied theoretical coding only to our interviews from the last round. As the interview guide was adapted intensively from the first round to the third one, informed by the results of the second round which used a completely different and very open interview guide adapted to intermediary organizations, we did not consider it helpful to impose the theoretical codes on the previous interview rounds. We ensured reflexivity of our approach and our understanding by continuous discussions among us which were enriched by our different institutional environments and our different disciplinary and methodological backgrounds. Originality refers to developing new concepts but also to resonance (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021). We believe that our approach meets these criteria as we provide new insights to an underresearched topic and our research diverges from our own original concepts. Usefulness addresses the benefit of the research to policy development and practical applications (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021). We ensure usefulness not just through the background of one author in policy advice but also by providing clear policy recommendations.

ResultsFootnote3

Overall institutional setup

In our interviews, we found clear evidence for a lack of economic coordination based on inefficient intermediary organizations and a considerable amount of distrust in political actors. All first-round interviews pointed in this direction that was confirmed in second and third-round interviews. Statements on distrust and the inefficiency of intermediary organizations often concerned intermediaries that are perceived as connected to government such as chambers of commerce which are seen as slow, uncompetitive, not understanding of firms’ needs, and not offering adequate return on membership fees. This points towards a low-coordination economy. Several business-driven intermediaries, in contrast, were considered beneficial.

The fractioned setup of BiH, based on the Dayton peace agreement, was an ongoing topic in all three interview rounds. The various levels of government feature different policies, responsibilities, and administrative structures with a considerable degree of inconsistency. As one interviewee put it, firms face ‘different regulations at municipal, cantonal, entity, state level that make it difficult for companies to operate’ up to the point that ‘when you import a product under all laws of BiH, and then drive it to a canton, then you have some additional regulations at the cantonal level or fees and levies that make it difficult’ (A7, para 13). In this complex governance structure, formal institutions are contradictory and redundant but at the same time, when referring to unified higher-level coordination, missing or incomplete. An example raised was the absence of a central, state-level innovation agency. In essence, what this picture suggests is a complicated mosaic of institutional voids.

Institutional voids

The interviews revealed difficulties in access to human resources. While this was not an issue in our first round of interviews, four out of six intermediaries in the second round focused on these difficulties. Some of them relate to brain drain but most are based on outdated or not updated curricula which are a commonly described institutional void in transition economies (Schrammel Citation2014). During the third round of interviews, one company representative mentioned the qualified workforce in BiH as their success factor but three out of five interviewees stated access to human capital as their main challenge.

Although on the level of formal policies, steps to establish institutional and regulatory frameworks for access to finance were taken in BiH (OECD Citation2018), interviewees agreed that capital is still insufficiently available. A particular problem was identified in accessing alternative financing mechanisms that are crucial for bridging funding gaps and in finding appropriate financing models for individual business projects that seem to be almost non-existent in BiH. This institutional void is consistent with the literature that stresses constraints for startup formation and entrepreneurship in terms of access to sources of external finance (Beck and Demirguc-Kunt Citation2006) and the availability of venture capital (Schwab Citation2019).

Institutional asymmetries

During the first round of interviews, identifying institutional asymmetries was challenging. When asked about laws and regulations interviewees perceived as detached from informal norms and traditions, most of them could not name any, even though many stated that this phenomenon does clearly exist. Some interviewees mentioned they perceive some laws as copy-pasted from foreign legal systems and not sufficiently adapted to the local context. Interviewees did not name an example of copy–paste laws relevant for innovation policy. Rather, a smoking ban was named as an example for a law that is not sufficiently adapted to local context. Thus, the results confirm one of our initial expectations albeit on a general level.

When looking deeper into the challenges interviewees mention, it is possible to identify issues that have been discussed in the context of institutional asymmetries in the literature and that surfaced more clearly during the second and third round of interviews.

Half of the first ten interviewees intensively discussed what we originally labeled as ‘unbeneficial tax system’. Most of the comments refer to the value-added tax (VAT) that is perceived as too high or unfair. Intermediary organizations elaborated on this issue as well and referred to high taxes on salaries and resulting low competitiveness. Consistent with Williams and Horodnic (Citation2015b), there seems to be a tendency to envelop wages in BiH which is mostly related to high taxes on salaries and inflexible labor laws. Thus, what sounded like a general complaint of an institutional void in the beginning turned out to be an institutional asymmetry as one interviewee related these complaints to a ‘socialist relic’ (A1, para 58) in terms of the perceived purpose of taxation. This insight is reminiscent of Ostapenko and Williams (Citation2016) and Williams and Horodnic (Citation2016a) who used ‘tax moral’ as a proxy to analyze institutional asymmetry. We can relate our findings to the fact that there is an institutional asymmetry in firms’ perceptions of the role and function of the tax system and its rules and regulations. Interestingly though, the high tax burden was not an issue in our last round of interviews. One company representative even considered the tax system in BiH good.

Another dominant issue was the non-implementation of laws that was sometimes discussed under the theme of unclear laws. We consider this issue an institutional asymmetry because a law exists on paper but is not put into practice, presumably because conflicts with other formal or informal institutions. Many interviewees relate this asymmetry either to an unwillingness of political actors or even to possible corruption and clientelism.

Several informal institutions exist that seem to be very prevalent. Many interviewees report on corruption and a gift mentality as well as clientelism and the importance of political connections on all levels of society. One interviewee ascribed corruption and clientelism to the party system. Interestingly, interviewees tend to see these practices as culturally engrained. Another aspect that appeared in all three interview rounds is what could be grouped under the theme of conservative, passive, and non-entrepreneurial mentalities in society that entrepreneurs are complaining about. Interviewees described low social engagement of other actors, a reactive mentality of state actors, and a general mentality not to question authorities but in somehow contradictory ways, as these two quotes demonstrate:

In our society, I think people, maybe now it is changing, but there is a big conception that somebody will do it for me. And by somebody usually that is government. (A1, para 48)

Culturally, people in our country think of ways to protect themselves from the state rather than how to develop their own state. (A5, para 27)

During the last round of interviews, these patterns emerged further by interviewees referring to conservatism related to innovation:

Our people are too traditional and sometimes it's hard to implement some new ideas, to innovate in our market. (B5, para 12)

People (…) do not embrace change, and innovation is all about change. We are very crude in our way of thinking about the new processes. (B3, para 14)

Some interviewees related these informal institutions to the socialist history of BiH which implies path dependence whereas others related them more to institutional voids in the education system. The former is in line with Williams and Vorley (Citation2015a) who related institutional asymmetries as mismatch of formal and informal institutions in the field of entrepreneurship in Bulgaria to the country’s socialist past.

Innovation policy context

Concerning the context for innovation policy, first-round interviewees perceived the competitive and innovative environment in BiH as primarily unbeneficial. Several company representatives stated that innovation policy does not exist at all in the country or were very skeptical about implementation. This was one of the main reasons that we opted for interviews with intermediary organizations in the second round to get a clearer picture of the state of innovation policy. Here, four out of six interviewees stated that innovation policy does not exist in BiH and the interviewer had to mention existing policies. Most interviewees mentioned that due to the complex institutional setup of BiH, even though innovation policies exist on some levels there is no unified state-wide approach to innovation policy. Some interviewees mentioned that policies exist but are not properly implemented, for example by stating that ‘BiH’s innovation and competitiveness policies are formal in nature and do not result in concrete measures in this direction’ (A5, para 36) which hints at an institutional asymmetry between formal policies and actual implementation practices. Other interviewees referred to the limited funding for innovation and to a lack of innovation understanding. In the third round of interviews, we explored this issue in more depth. Four out of five interviewees stated that they are in a beneficial location for innovation compared to other cities which is arguably due to the fact that their company headquarters are in larger cities with better access to funding and networks. Alternatively, when compared to South East Europe or the EU and when considering the perceived non-existence of innovation policy, respondents believed that BiH does not have a highly beneficial innovation environment. This finding is in line with low R&D investment and innovation capacity in BiH (Schwab Citation2019). We could not confirm the lack of innovation understanding assumed by some intermediaries as all company representatives could define and name innovations, even though the majority of them related them to product rather then process innovations. Most company representatives during the third round stated a lack of human resources as a main innovation challenge, referring to skilled staff. This constraint relates to the institutional void in education described above. Some interviewees stated a lack of financial support as an innovation barrier.

Participatory policy approaches

When we focused on participatory policymaking approaches to assess the institutional environment for smart specialization, nine out of ten first-round interviewees either had no experience with participatory approaches or if they had been invited to participatory meetings did not perceive these meetings as participatory as in the case of one company representative who reported ‘not [having] seen any concrete result of these discussions, that something has really been done’ (A10, para 33). One interviewee hinted at the low participation in existing participatory policymaking on urban planning being related to a lack of ownership related to the passive mentalities discussed above. Some interviewees related their dissatisfaction with participatory policymaking approaches to the complex institutional setup of BiH with its dispersion of responsibilities which leads to several unconnected policy fora. All five company representatives during the final interview round were skeptical towards participatory policymaking approaches by stating that they were either not invited or did not feel their opinions were heard, thus confirming the results of the first round of interviews. In contrast, half of the intermediary interviewees perceived that the policymaking approach has recently become more participatory. Hence, there seems to be an institutional asymmetry between participatory policymaking approaches that do in some instances exist and informal institutional patterns such as dissatisfaction, distrust, a lack of credibility of participatory policymaking fora, and passive attitudes.

Discussion

The general picture emanating from our interviews confirms our proposition that BiH qualifies as a low-coordination economy marked by low degrees of institutional and organizational thickness observed through a lack of mutual trust and cooperation, and weak intermediary organizations, at least apart from private-sector intermediary initiatives (Amin and Thrift Citation1994; Benner Citation2019a; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020; Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017).

The results on existing institutional voids in BiH are in line with previous research on South East Europe (Estrin and Mickiewicz Citation2011; Konstantynova and Lehmann Citation2017; Lehmann and Jungwirth Citation2019; Schrammel Citation2014). In particular, the difficulties related to the availability of qualified human and financial capital are consistent with previous research on institutional voids in South East Europe that suggest access to human capital as a major institutional void due to outdated curricula and rigid educational policies, and difficult access to financial capital due to conservative lending strategies and missing venture capital infrastructures (Estrin and Mickiewicz Citation2011; Schrammel Citation2014).

When relating our results to the literature on the country’s political and historical context, our finding of BiH being a low-coordination economy characterized by significant institutional voids and asymmetries fits into a picture marked by wider governance-related problems. In particular, this finding is in line with Fagan and Dimitrova (Citation2019) who discuss challenges related to the institutionalization of legal reforms and associate them with the institutional complexity of BiH and specific personal interests of individual actors, and with Padurariu (Citation2014) who describes the long-lasting journey of the implementation of a police reform. Divjak and Pugh (Citation2008) relate corruption in BiH to institutional asymmetries due to the complex setup of the Dayton peace agreement. Belloni and Strazzari (Citation2014) argue that corruption and clientelism are partly rooted in the history of war and the international pressure for transition. Still, the results are generally in line with the findings Williams et al. (Citation2017) report about clientelism and corruption in Montenegro.

The EU integration process that leads to the gradual alignment of national laws and regulations with the acquis communautaire could further increase the institutional asymmetries identified. In particular, the legislation of laws aligned with the acquis communautaire could lead to an even more complex formal institutional environment due to the multi-level structure of BiH and absent or inconsistent implementation of laws. In such a context, introducing EU approaches to innovation policy such as S3 risks adding yet another layer of formal policies without achieving the streamlining that seems urgently needed.

Taken together, our specific results on institutional voids and asymmetries relevant for firm competitiveness and innovation and their relation to wider governance-related problems refer back to the quandary of S3 that can be expected to be even more severe than in other South East European countries. On the one hand, the introduction of a participatory policymaking approach such as S3 with its concomitant institutional dynamics seems urgently needed. On the other hand, the institutional reasons why such an approach is needed are precisely what makes its introduction so difficult and challenging. Following Benner (Citation2019a), this quandary boils down to an institutional smart specialization paradox. Similar paradoxes are well known from the literature. The institutional smart specialization paradox is reminiscent of the ‘regional innovation paradox’ about regions that need effective innovation policies but whose capabilities may be too weak to implement them satisfactorily (Oughton, Landabaso, and Morgan Citation2002; see also Gianelle et al. Citation2020). Similarly, lagging regions might find it most difficult to promote radical diversification through smart specialization for institutional reasons, particularly if they exhibit low-coordination features (Benner Citation2020c). In terms of process, Capello and Kroll (Citation2016, 1399) highlight a governance-related ‘EDP paradox’ that regions or countries that need a more active government role in the EDP exhibit weak governance capabilities to exert this role. Rauch (Citation2009) mentions that participatory rural development approaches in developing countries presuppose institutional conditions which leads to a similar paradox because these institutional conditions should be built in these processes themselves. The institutional smart specialization paradox touches these issues but is understood here as specifically related to institutional voids and asymmetries. This paradox is underscored by evidence from the EU that the EDP faces particularly significant challenges in regions with weak institutional environments (e.g. Capello and Kroll Citation2016; Karo, Kattel, and Cepilovs Citation2017; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020).

Thus, our conceptual framework needs to be complemented by one critical finding. Our results clearly imply that besides the role of S3 in possibly mitigating institutional asymmetries through institutionally contextualized strategies and through institutional leapfrogging during the EDP (which our results cannot confirm since S3 has not been introduced in BiH so far), there is a clear gap between the institutional prerequisites that facilitate S3 and the institutional context found in BiH, as the low credibility of and satisfaction with participatory policymaking and innovation policies that emerged during our interviews demonstrate. Introducing S3 without sensitivity to these institutional prerequisites thus runs the risk of creating a large institutional asymmetry on the meta level. While Croatia and Slovenia seemed to have overcome this institutional asymmetry, at least in part, by leapfrogging underscored by the ex-ante conditionality under EU cohesion policy (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c), such a way to bridge the meta-institutional void by providing credibility to the process and convincing firms that S3 actually offers an opportunity to overcome existing institutional voids and asymmetries is not apparent in BiH.

Conclusions and policy implications

In this article, we inductively explored the institutional context of BiH by identifying institutional voids and asymmetries. The results sketch a picture of a low-coordination economy fraught with considerable institutional inconsistencies that make effective innovation policy very difficult, conforming to warnings in similar contexts found elsewhere (e.g. Williams and Vorley Citation2015a).

According to our conceptual framework, the introduction of S3 with its EDP can contribute to mitigating institutional asymmetries. First, S3 can facilitate the formulation of policies able to change formal institutions and to fill institutional voids. Second, S3 can provide private-sector feedback to policymakers on existing institutional asymmetries to policymaking on the level of formal institutions. Third, the EDP enables institutional leapfrogging through upward causation of change on the level of informal institutions. While these propositions are informed by previous research notably on the neighboring low-coordination economies of Croatia and Slovenia (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c), they cannot be verified for the case of BiH before the introduction of S3 to the country during the coming years. What we did attempt in the present article is examining the institutional environment the introduction of the S3 approach will face in BiH. On the basis of the institutional smart specialization paradox, we can draw some conclusions for the introduction of S3 that might help policymakers design the process.

The absence of a bridge for the meta-institutional asymmetry between the formal introduction of S3 and incongruous informal institutional patterns such as distrust towards previous participatory policymaking formats and a lack of credibility of innovation policy in BiH severely calls into question the chances of S3 implementation. It is well possible that participating in the S3 exercise eventually builds trust at least among those actors who lack experience with participatory policymaking processes but are positive or neutral about them which would call for starting the process. Nonetheless, the critical question is if a sufficient number of these actors can be mobilized. In such an institutional environment, mobilization problems loom large and can eventually threaten the process with failure (Benner Citation2020a; Grillo Citation2017; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020). While in EU member states, the ex-ante conditionality under EU cohesion policy and subsequent funding for strategy implementation represents such a bridge by lending the process credibility (Benner Citation2019a; Citation2020c), a different mechanism will have to be designed in EU enlargement countries such as BiH. Linking co-funding for projects under the EU’s Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) to S3 could provide such a bridge and benefit from the macro context of the EU integration process.

Nevertheless, a commitment by government on all levels will be crucial to keep the credibility afforded by such an IPA conditionality. As the literature on smart specialization within the EU (e.g. Benner Citation2020b; Capello and Kroll Citation2016; Gianelle et al. Citation2020; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020) demonstrates, preparing for implementation will most likely be the even greater challenge than organizing the EDP. Setting up effective administrative structures, building their capacities and allocating a sufficient budget for them is definitely desirable, but to do so in time seems to be an unrealistic goal. Alternatively, in BiH the only viable way to implement the smart specialization approach and to seize its potential to reduce institutional asymmetries might be to draw even more strongly than other regions or countries on those few intermediary organizations that enjoy a good reputation and the trust of private-sector firms. Private industry-level associations could play this role, first by taking a strong role during the EDP (e.g. by leading working groups) and second by contributing to implementation. While budget constraints may limit the possibilities to fund projects implementing the eventual smart specialization strategy, implementation could focus to a large degree on collaborative ventures under the leadership of these intermediary organizations, while the government could focus on a limited number of modifications in formal institutions (notably laws and regulations) identified as critical during the EDP. Instead of steering the allocation of project funding, as is the case in EU member states under EU cohesion policy, S3 in BiH could thus focus more on reducing institutional asymmetries by building on private-sector dynamics and reducing the administrative complexity for firms in the priority domains defined by the strategy. However, doing so will most likely require strengthening the capacities of weak intermediary organizations, confirming the call for S3 to pay more attention to capacity building that has repeatedly been addressed in the literature (e.g. Benner Citation2020b; Gianelle et al. Citation2020; Karo, Kattel, and Cepilovs Citation2017; Papamichail, Rosiello, and Wield Citation2019).

An open question is whether the national level is the most appropriate scale to roll out S3 in BiH, a country with strong sub-national entities. The scalar confusion of S3 (see also Capello and Kroll Citation2016), an approach that has become a pillar of the EU’s cohesion policy explicitly designed for regional development, has been criticized in the literature (Benner Citation2020b). Even considering the small size of BiH, implementing an approach of regional innovation policy on the national scale raises institutional questions that may render the mitigation of institutional asymmetries even more difficult. In particular, the specific case of BiH calls for complex processes of policy alignment between the cantons, entities, and state. The results of our empirical study suggest that the lack of multilevel policy alignment causes major institutional asymmetries in innovation policy. While the EDP could provide a forum for achieving policy alignment, doing so may prove a considerable challenge because the complexity of the task will be highest on the national level. At the same time, the feedback mechanism provided by the EDP and its contribution to mitigating institutional asymmetries might depend on mobilizing firms to participate in small-scale, regional, or even local-level formats. Even if S3 is implemented on the national level, organizing the EDP on the regional scale and consolidating the results into a national strategy inspired by Hungary’s example (Nemzeti Innovációs Hivatal Citation2014) might offer a workable compromise.

This article contributes to better understanding the role of informal institutions in economic development and notably the interaction of formal and informal institutions in policymaking processes and thus addresses existing gaps in institutional research (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2020). Specifically, our study contributes to institutional theory by clarifying the paradoxical role of participatory policymaking approaches in low-coordination economies. Given the upcoming introduction of S3 in BiH, further research will be important to further elucidate the possibilities and challenges of S3 in mitigating institutional asymmetries and, hence, to check the validity of the assumptions on which our conceptual framework is based. In particular, it will be important to examine how S3 actually contributes to mitigating institutional asymmetries, including by closing institutional voids through institutional leapfrogging, in such a complex political-institutional setup as in BiH. While other Western Balkan economies such as Albania or Kosovo can be expected to exhibit a similar low-coordination context with considerable institutional voids and asymmetries, BiH offers a particularly tricky case that calls for additional efforts in preparation, capacity building, training, and awareness raising in both the public and private sector. Pursuing applied research on how to design these supporting measures and policy evaluation to analyze their effectiveness could provide valuable lessons beyond the specific case of BiH. Further research on those other contexts will be useful to come up with a more comprehensive and systematic understanding of how to adapt a policy method to a different context. Further research on these questions can help us better understand how institutional change in low-coordination economies works. Given the ongoing processes of EU integration of enlargement countries in the Western Balkans and Turkey, doing so is highly relevant because it touches far more wide-ranging questions of institutional convergence or heterogeneity in an enlarged EU. We think there is much to learn about the interactions between EU alignment and the local institutional environment, and doing so will provide important lessons for how to overcome some of the institutional obstacles to EU accession that enlargement countries face.

Contributions of authors

T.L.: theory development, interviews, coding, analysis, writing, revision; M.B.: theory development, interviews, writing, revision; A.K.: interviews, coding, analysis, writing, revision

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to two student assistants at HTW Berlin for transcribing interviews, to Dimitrios Kyriakou for comments on the draft, to the Editor, Hans-Liudger Dienel, to the Associate Editor, Marco Wedel, and to three anonymous reviewers for their suggestions. Of course, all remaining errors and omissions are the authors’ alone, as are the opinions expressed.

Disclosure statement

In previous professional positions, M. Benner was involved in supporting the introduction of the smart specialization approach to the Western Balkans, including to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tine Lehmann

Tine Lehmann is a Professor at the University of Applied Sciences (HTW) Berlin, Germany. She has worked for an international development cooperation project and lived in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Her research focuses on institutional environments in transition economies and the specific constraints they hold for businesses.

Maximilian Benner

Maximilian Benner is a senior post-doctoral researcher in economic geography at the Department of Geography and Regional Research at the University of Vienna, Austria, with a focus on regional development in EU enlargement and neighborhood countries. Previously, he worked at the European Commission and as a consultant in international cooperation. His research focuses on institutional and evolutionary economic geography with a focus on the Western Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Amra Kapo

Amra Kapo is an Associate Professor at the Department of Management and Information Technology at the School of Economics and Business, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. She is also engaged as a researcher in various projects funded by state institutions or by the European Commission (for example, IPA-funded projects). She co-authored several scientific papers and book chapters with a focus on management information systems, e-learning, innovation, continuous learning, and decision support systems.

Notes

1 In the new EU financial period starting in 2021, ex-ante conditionalities are transformed into enabling conditions (Benner Citation2020b; Larosse, Corpakis, and Tuffs Citation2020).

2 The recent criticism against the 'Doing Business' reports and their discontinuation (World Bank Citation2021) should be noted. Still, given the relative scarcity of comparative data related to the institutional environment in the Western Balkans, the ranking might be useful at least as a rough approximation.

3 Where quotes are taken from interviews not conducted in English, translations were made by one author.

References

- Alshbili, I., A. A. Elamer, and M. W. Moustafa. 2021. “Social and Environmental Reporting, Sustainable Development and Institutional Voids: Evidence from a Developing Country.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28 (2): 881–895. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2096.

- Amin, A., and N. J. Thrift. 1994. “Living in the Global.” In Globalization, Institutions, and Regional Development in Europe, edited by A. Amin, and N. J. Thrift, 1–22. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Asheim, B. T. 2019. “Smart Specialisation, Innovation Policy and Regional Innovation Systems: What About new Path Development in Less Innovative Regions?” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32 (1): 8–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1491001.

- Bathelt, H., and J. Glückler. 2014. “Institutional Change in Economic Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (3): 340–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823.

- Beck, T., and A. Demirguc-Kunt. 2006. “Small and Medium-Size Enterprises: Access to Finance as a Growth Constraint.” Journal of Banking and Finance 30 (11): 2931–2943. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.009.

- Belloni, R., and F. Strazzari. 2014. “Corruption in Post-Conflict Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo: A Deal among Friends.” Third World Quarterly 35 (5): 855–871. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.921434.

- Benner, M. 2019a. “Smart Specialization and Institutional Context: The Role of Institutional Discovery, Change and Leapfrogging.” European Planning Studies 27 (9): 1791–1810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1643826.

- Benner, M. 2019b. “Tourism in the Context of Smart Specialization: The Example of Montenegro.” Current Issues in Tourism 23 (21): 2624–2630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1687663.

- Benner, M. 2020a. “Mitigating Human Agency in Regional Development: The Behavioral Side of Policy Processes.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 7 (1): 164–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1760732.

- Benner, M. 2020b. “Six Additional Questions About Smart Specialization: Implications for Regional Innovation Policy 4.0.” European Planning Studies 28 (8): 1667–1684. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1764506.

- Benner, M. 2020c. “The Spatial Evolution-Institution Link and its Challenges for Regional Policy.” European Planning Studies 28 (12): 2428–2446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1698520.

- Boyer, R. 2005. “Coherence, Diversity, and the Evolution of Capitalisms – the Institutional Complementarity Hypothesis.” Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review 2 (1): 43–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.14441/eier.2.43.

- Capello, R., and H. Kroll. 2016. “From Theory to Practice in Smart Specialization Strategy: Emerging Limits and Possible Future Trajectories.” European Planning Studies 24 (8): 1393–1406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1156058.

- Chakrabarty, S. 2009. “The Influence of National Culture and Institutional Voids on Family Ownership of Large Firms: A Country Level Empirical Study.” Journal of International Management 15 (1): 32–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2008.06.002.

- Charmaz, K. 1990. “‘Discovering’chronic Illness: Using Grounded Theory.” Social Science & Medicine 30 (11): 1161–1172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90256-R.