Abstract

This primarily conceptual contribution introduces a sociological framework for tracing the effects and the sources of stability or instability of societal nature relations to the thoughts, feelings and doings of actually existing people. Drawing on critical debates on societal nature relations, we argue that modern capitalist societalization is inherently expansionary, that the rapid expansion of human economic activity over the past two centuries was only possible based on fossil resources, and that therefore, moving to a post-fossil world will require reinventing the very essence of what “society” is. To investigate the implications of such a fundamental overhaul at the level of how socialized people relate to socialized nature, we build on the relational sociology of Pierre Bourdieu to suggest the framework of a space of social relationships with nature. We describe the iterative process in which we arrived at this conception, moving back and forth between theoretical considerations and hermeneutic analysis of qualitative material from case studies of bio-based economic activities in four European regions. From the iterative process, we synthesize four elementary forms of social relationship with nature (“natural capital”, “nature as partner”, “natural heritage” and nature as “the environment”) and provide an illustrative corner case for each. From the systematic differences that emerge, we then draw out two principal axes of a spatial representation partly homologous with Bourdieu’s social space: a vertical axis indicating the degree of active involvement in and access to the means of abstract-expansionary societalization, and a horizontal representing the form of that involvement, along a continuum from dualist, instrumental and appropriative to holist, mutual or caring relationships with nature. In conclusion, we propose further research to apply and develop this relational framework across local or national contexts and scales as a means to analyze tensions and conflicts around transformations of the societal nature relations.

1. Introduction

In this paper, we want to make a sociological contribution to the ongoing debates around human-nature relationships and their relevance to overcoming the present socio-ecological crisis. “Sociological” is to be taken seriously here, in that we call for an analysis of these relationships based on a theoretically substantial notion of society. From a sociological perspective, human-nature relationships are always socially mediated: they are rapports between socialized individuals and socialized nature under specific social conditions, in short: social relationships with nature. This notion, recently suggested by Eversberg (Citation2021b), is intended as a sociological complement to the theoretical concept of “societal nature relations” as developed by social ecologists in the tradition of the Frankfurt school (Jahn Citation1991; Görg Citation1999; Becker and Jahn Citation2006). It aims to provide an approach for tracing the effects as well as the sources of stability or instability of societal nature relations to the thoughts, feelings and doings of actually existing people. If the term “societal nature relations” refers to the organization of the social metabolism corresponding to a specific societal formation or mode of societalization (Vergesellschaftung), social relationships with nature are the mental and practical manifestations of the ways in which individuals and groups are positioned within and toward that organization, and contribute to maintaining or altering it. Coming to analytical terms with these is crucial because modern, and especially capitalist, processes of societalization are the cause of ecological crisis, following an inherent dynamic of expansion (Dörre, Lessenich, and Rosa Citation2015) that proceeds in indifference to the concrete bounds of nature. It is a core concern of the literature on societal nature relations to explore the conditions and trajectories of social-ecological transformations, i.e. reconfigurations of these relations (U. Brand and Görg Citation2001; U. Brand Citation2016; Krausmann and Fischer-Kowalski Citation2010). By focusing on the subjective and practical level of these transformations, we aim to add greater sociological depth to these efforts, both in the analytical sense of understanding the various levels at which they unfold and in the normative terms of exposing the opportunities of and challenges to the much-needed transformation towards a post-fossil society.

This article documents our attempt to come up with a framework for systematic sociological analysis of social relationships with nature. It emerges from our ongoing qualitative research on the role of mentalities and practices in local transformations involving bio-based economic activities in four European regions. In drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s relational sociology and conceiving of social relationships with nature as comprehensive patterns of mentally and practically relating to nature, we intend to make the thinking around societal nature relations amenable to empirical research on how these patterns vary among people in modern capitalist social environments, and on the roles they play in socio-ecological change. Rather than just a description of different social relationships with nature, this requires an overall account of the social field of ways of relating to nature that renders visible how their variations tie in to those broader processes. To provide this account, we draw on the insights of the societal nature relations literature on the expansionary character of modern societalization. This provides a starting point for a socio-ecological adaptation of Bourdieu’s conception of social space, the space of social relationships with nature. This conception presents an analytic for the very different ways in which individuals and social groups are mentally and practically involved in the structure of societal nature relations, as well as a heuristic for understanding how they contribute to reproducing or altering it, i.e. for further empirical exploration of the social preconditions for and barriers to transformations of societal nature relations, as well as the possible changes of mental and practical habits resulting from them.

We proceed in three steps: Section 2 briefly introduces the debates on societal nature relations as our theoretical entry point and explains the problematic of expansionary societalization as a driving force of ecological crisis. Section 3 suggests the notion of social relationships with nature as a necessary sociological complement that can be investigated using the tools of Bourdieu’s relational sociology, namely his concepts of the incorporated social, of socially structured practice, and his conception of the social as a space. Section 4 presents our construction of the space of social relationships with nature and details how we arrived at it based on these theoretical sources and our qualitative research on four case studies of bio-based economic activities. In section 5 we conclude with some considerations on how to further empirically and conceptually develop this framework.

2. Societal nature relations and the problem of expansionary societalization

An adequate understanding of the relationships between people and nature must take into account the mediation of these relationships by a third instance: society. Counter to common sense notions, society is not the sum of all individuals and social groups, or of their actions. In theoretical terms, it is more adequately conceived as a structured totality of relations between people, other people and extra-human nature, and since those relations only exist through their constant practical (re)production, ought to be seen as the dynamic outcome of processes of “societalization” (Vergesellschaftung). The latter term and its theoretical implications have been a staple in German-language sociology since Marx (Citation1967), Simmel (Citation1908) and Weber (Citation1922), and have shaped the thought of social theorists until the present day (Schmidt Citation2020). Yet, among the classics, the role of nature in these processes has been a central concern only in the works of the first-generation Frankfurt School on the dialectical character of modernity and the intimate intertwinedness of social dominance and ecological destruction as its twin results (Horkheimer and Adorno Citation2002; Horkheimer Citation2004): Since around 1990, German-speaking research groups have built on this tradition to develop a sophisticated concept of societal nature relations (Gesellschaftliche Naturverhältnisse), to remedy the disregard for nature in social theory and its inability to adequately come to terms with phenomena of ecological crisis. The mostly theoretical work of the early years (Jahn Citation1991; Jahn and Wehling Citation1998; Görg Citation1999) found its continuation in analyses of how societal nature relations are reorganized in contested processes of socio-political regulation (Görg Citation2003; Wissen Citation2011; U. Brand and Görg Citation2001; Görg and Brand Citation2003; Wullweber Citation2004), and of how that regulation plays out in fields such as mobility, agriculture or housing (Becker and Jahn Citation2006). Others have drawn out the concept’s gendered implications (Gottschlich, Mölders, and Padmanbhan Citation2017; Bauhardt Citation2015), or used it to scrutinize transformations of the societal metabolism (Krausmann and Fischer-Kowalski Citation2010; Haberl et al. Citation2016). Societal nature relations is thus a core concept of Social Ecology work that explores the interlinkages between society and nature, but, in highlighting the historicity of its object, its openness to change and the importance of power relations and political struggles to such change, it is also a powerful analytical tool for research in Political Ecology (U. Brand and Wissen Citation2013; Wissen Citation2014).

The notion of societal nature relations implies much more than the rather banal statement that any form of human social organization depends on its biophysical environment and needs to deal with that dependency in some way. Variegated as this research has become, its common starting point may be seen in the insight that humans only became capable of distinguishing between “society” and “nature” as two distinct entities at a certain a point in history, namely once they had accumulated sufficient knowledge, technological and institutional capacity as to afford the degree of mastery over their conditions of existence that allowed them to perceive of themselves as logically independent of those conditions (Horkheimer and Adorno Citation2002, 1–34). Traditional social worlds, such as the Kabyle cosmology analyzed by Bourdieu (Citation1990, 200–270), were neither capable nor in need of making a distinction between the social and the natural elements of their world, nor could people living in such circumstances perceive themselves as individuals. “Society” in the modern sense is, therefore, better conceived as a concatenation of interrelated processes of societalization – including the emergence and expansion of capitalist production and markets, the progress of scientific knowledge and technology, and the genesis of the state –, in which “society” is constituted as an entity that unfolds according to its own abstract logic and without regard for any limits that the concrete boundedness of humans and non-human nature may imply. Both nature and human individuals are shaped by and subject to the growing demands imposed by these processes – societalization can only continue along its expansive trajectory by increasing the exploitation of both, ultimately undermining its own biophysical and subjective foundations. Seen in this light, ecological crisis is not a contingent state of affairs, and de-fossilization presents a challenge to the core logic of societalization itself. This is because for around 200 years, modern capitalist societalization has been fossilist in both material-energetic and structural terms: The ubiquity and force of the processes of practical abstraction that pervade every aspect of the social and biospheric today would have been impossible to establish without colossal, permanently increasing inputs of abstract fossil energy that could be appropriated, transformed and used at will. The readiness of its availability was a necessary substratum for unprecedented waves of commercial, industrial, military and agricultural expansion, from the so-called industrial revolution (Barca Citation2011) through late nineteenth century imperialism (Luxemburg Citation1913; Malm Citation2018) to the “Great Acceleration” of the twentieth century’s latter half (Steffen et al. Citation2015) and the “Green Revolution” (Cleaver Citation1972) that powered it. Throughout the fossil age of expansion, coal, oil and gas have helped make the physical (Elhacham et al. Citation2020; Krausmann et al. Citation2017), political-institutional (Mitchell Citation2011) and mental (Welzer Citation2011) makeup of the contemporary world amenable to a degree of control through abstract societal logics that was unthinkable to earlier eras and remains unexplored in many of its dimensions.

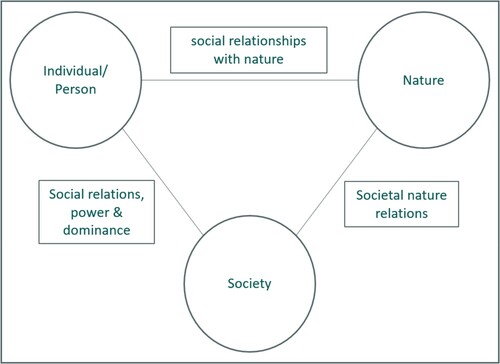

Since society is not simply the sum of all people, exploring the relationships between people and nature requires taking it into account as a reality in its own right. This implies considering a triangle of relations between people, nature and society (Frankfurt Institute for Social Research Citation1972, 41; Hornborg Citation2001, 193, see ), in which both of the former can only interact as socialized entities and under given societal conditions. The implication is that societal expansion, the subjection of nature and social domination are one and the same process: “The history of man's efforts to subjugate nature is also the history of man's subjugation by man” (Horkheimer Citation2004, 72). The expansive dynamics of processes of societalization that have become (seemingly) “emancipated” from their human and natural limitations through technologies of knowledge, power and subjectivation necessarily introduce and deepen hierarchical divisions among people, (Biesecker and Hofmeister Citation2010), within which the hierarchically subordinate (women, caregivers, the colonized and dispossessed) are typically demoted and devalued by symbolic and practical association with the “natural” (Graeber Citation2007a, 22; cf. Bourdieu Citation1984, 40, 196, 479, 490–491).

Figure 1. The triangular relationship between individuals, nature and society (own representation, drawing on Frankfurt Institute for Social Research (Citation1972, 41) and Hornborg (Citation2001, 193)).

A theory of societal nature relations is therefore not a supplement to theories of social power and dominance, but a broader framework that these need to be embedded in. Within that framework, the “individual”-”nature” side of the triangular relationship has so far received relatively little attention. While Horkheimer, Adorno and Marcuse pondered this connection and considered the “remembrance of nature within the subject” as a central task of Critical Theory (Schmid Noerr Citation1990), the empirical implications of this formula have remained largely unexplored (but see Berghöfer, Rozzi, and Jax Citation2010). While societal nature relations in the narrower sense (the triangle’s “society”-”nature” side) can be investigated at an abstract macro level, concern with how specific socialized people relate to socialized nature requires an approach that is sensitive to structured variation, more akin to Adorno’s work with the Berkeley group on the forms of relationship with society that characterized authoritarian individuals (Adorno et al. Citation1950). Evidently, the empirical ways of how socialized individuals relate to socialized nature, or people’s social relationships with nature, will differ depending on which sides of the multiple hierarchical separations introduced by expansionist societalization they find themselves on, how they got there and what they experienced along the way.

3. Social relationships with nature: coming to terms with variation

How can the socially structured variation in people’s relationships be investigated empirically, at the level of concrete individuals and groups (rather than abstract structures), but with a view to its societal relevance, i.e. taking all three sides of the “individuals – nature – society” triangle into account? In this section, we will first provide a very brief overview of existing research on human-nature relationships to show that this is an unsolved challenge (2.1.), and then go on to suggest an ecologically updated reading of Pierre Bourdieu’s relational sociology as our approach to solving it (2.2.).

3.1. Approaches to human-nature relationships

The broadest strand of existing research on human-nature relationships relies on empirical observation or “measurement” of how individuals or social groups relate to nature. Mostly from a methodologically individualist perspective, it defines and operationalizes concepts such as nature-related “values” (Inglehart Citation1982; Klain et al. Citation2017; Stern and Dietz Citation1994), “attitudes” (Diekmann and Preisendörfer Citation2003; Franzen and Meyer Citation2004), “perceptions” (Knight Citation2016; Shafer Citation1969) or “environmental awareness” (Iosifidi Citation2016; Knight Citation2016) and their and their causal links with different social characteristics as well as with “behavior” (Preisendörfer and Diekmann Citation2021). Such research produces methodically solid accounts of different perceptions, attitudes and practices in relation to nature that are present in specific “societies” and how they change over time, but since “societies” from this perspective are usually conceived as the sum of individuals, it has little to say about the relevance of such differences and changes to processes at a societal level as we understand them.

A second strand of relevant research tries to grasp structured patterns of difference in relating to nature in the form of typologies, identifying and distinguishing a variety of different types or “models” of relationship. This is often achieved by clustering or grouping from survey data those individuals that exhibit similar nature-related “worldviews” and “lifestyles” (Hedlund-de Witt, de Boer, and Boersema Citation2014; Hedlund-de Witt Citation2012) or forms and degrees of environmental consciousness (BMUV and UBA Citation2020; Kuthe et al. Citation2019), but there are also studies that build such types based on qualitative data (Breit and Eckensberger Citation1998; Poferl, Schilling, and Brand Citation1997) or on a conceptual basis (Muradian and Pascual Citation2018). While these are generally instructive, and the latter two kinds often also theoretically well-informed, the types they identify are usually additively presented side-by-side, leaving open the question of how they relate to each other and to a larger societal whole.

This latter category somewhat overlaps with a third tradition, rooted in ethnographic work on conceptions of and interactions with the extra-human in non-modern or non-western social contexts (e.g. Descola Citation2013; Douglas Citation1999; cf. Hornborg Citation2001, 197), which is clearly at odds with the methodological individualism of the measurement approaches, focusing instead on the broader cosmologies and relational networks that human-nature relations are part of. These are qualitatively observed and distinguished as differing experience-based ways of dealing with the extra-human by different groups in ethnographic work (e.g. Berghöfer, Rozzi, and Jax Citation2010; Tittor Citation2020). While this perspective is typically deployed in settings with clear-cut distinctions between the different mutually related groups, society as a necessary third element to the relationships is a core concern (Hornborg Citation2001, 191–210).

3.2. Bourdieu: the incorporated socio-ecological and the socio-ecological space

The sociology of Pierre Bourdieu seems an apt starting point for the task at hand because, after having applied the latter perspective in his early work, he later went on to apply the anthropological concern with comprehensive cosmologies and relational patterns to complex modern societies.

In 1950s Algeria, Bourdieu studied the traditional Kabyle cosmology, an elaborate symbolic system built around the logical parallelism between the cycles of the day, year and human lifespan, closely tying the ritual practices of the community to the circular astronomical, meteorological as well as (human and non-human) biological temporalities of nature. The “communal” nature relations were thus instituted as both an integral part of the collectively shared imaginary of the rural population and as a template for the ordering of their everyday practices. Not caught up in the processes of expansionary societalization, and at the low degree of mastery over nature that this implied, the Kabyles had fully integrated their dependency on nature into the way they collectively imagined their social relations.

The core insight of Bourdieu’s sociology that was already present in this observation is the importance of what he came to call the “incorporated social”: The realization that social worlds gain their stability not only from the infrastructures and institutions they materialize in, but also from their practical incorporation, their habituation as the “normal”, accustomed state of affairs, in the course of lived experience. As “embodied history, internalized as a second nature and so forgotten as history” (Bourdieu Citation1990, 56), this embodied form of the incorporated social, or habitus, encompasses the “whole of the inner and outer posture” (Vester et al. Citation2001, 24) of a person, consisting of a set of schemes of perception, evaluation and action (dispositions) that are both acquired and deployed in practical interaction with the social and natural world, and that orient action toward meaningful outcomes without a need for conscious reflection.

What the Kabyles’ collective nature relations also testified to was the crucial role of social practice as the site of mediation between the incorporated and objectified states of the social. This is a second core element of Bourdieu’s “theory of practice” (Bourdieu Citation1977): Practices are both instances of the “externalization of internality”, the actualization of dispositions in engagement with a set of external conditions, and of the “internalization of externality”, the shaping of those dispositions by habituating experience (Bourdieu Citation1977, 72). This dialectical mediating function of practices is crucial for understanding processes of both social reproduction and change.

In his later work on the role of education and culture in the reproduction of class in 1960s France, Bourdieu brought these basic insights to bear for the analysis of a modern capitalist society. For this purpose, he needed two more key concepts: capital and field, which together allowed for a spatial conception of modern sociality. In contrast to the unitary structure of practice organized by traditional cosmologies, which allowed little variation in habitus, he found that the structure of modern social worlds is better conceived as a space, structured by the distribution of different species of (cultural/educational, social, economic, symbolic) capital. Plotting the distribution of control over such capitals as “shares in the social” affording differential degrees of social power, a vertical axis representing the social hierarchy of status and influence and a horizontal axis displaying the relative investment in material property (right pole) or knowledge and education (left pole) and corresponding continua from distinctive to necessity-oriented (vertical) and from conventional-hierarchical to progressive-egalitarian logics of social relationships (horizontal) emerged (Bourdieu Citation1984, 126–131). As an order of inequality and differentiation, this spatial organization, held in motion by dynamics of competition for and accumulation of capitals, was thus shown to bring about systematically different forms of habitus in people, adapted to the different locations in the unequal space they occupied(Bourdieu Citation1984, 126–131, 175–208).Footnote1

It may be clear from what has been said that Bourdieu’s concepts are compatible with a substantial notion of society, i.e. suited to examining the “individuals-society” side of the triangle. However, Bourdieu was critical of what he perceived as the deductive logic of “grand theories”, instead championing a “genetic” approach of reconstructing the mental and practical foundations of the “structures” they are concerned with (Bourdieu Citation2014, 113). Still, the main concepts of his socio-structural analysis were adapted from classical sociological theory: although empirically constructed, the conception of social space as presented in his book Distinction (Bourdieu Citation1984) was consistent with theoretical assumptions about ongoing societalization processes that were present as guiding concepts in Bourdieu’s mind: Implicit in the notion of capital, somewhat obliquely borrowed from Marx, was the assumption of a structure of power and hierarchy based on property, and the distinctions between fields and “species of capital” imported an idea of modernization as increasing differentiation, division of labour and levels of knowledge going back to Durkheim (cf. Vester et al. Citation2001, chap. 2). Yet, in this phase there were no such guiding assumptions that could have sustained Bourdieu’s earlier awareness of the connection between social dominance and control over nature (Bourdieu Citation1962, 129–134), now that he was confronted with a situation in which the societal nature relations were much more strongly mediated. This itself is telling: in a phase of rapid expansion, the steadily increasing availability of abstract fossil energy had made society’s dependence on nature practically invisible, so much so that even a sociological observer deploying an anthropological optic sharpened in detailed analysis of a traditional socio-natural order did not feel the need to reflect it in his guiding assumptions. As a result, Bourdieu’s sociology of distinction, cultural taste and field-specific power struggles itself operated within the epistemological confines of a carbon-based industrial society (Mitchell Citation2011) during the phase of naturalized intensified expansion now termed the “Great Acceleration” (Steffen et al. Citation2015). Focusing on the internal dynamics of what has been termed “externalization societies” (Lessenich Citation2019), it left aside the accelerating exploitation of nature and the globally unequal social relations that formed the basis of their functioning.

Ultimately, Bourdieu’s social space provided an image of the totality of social relations of power and dominance, but it could not account for the way these relate to the role(s) of nature. Now, while the idea of the incorporation of the social as mediated in practice and the spatial conception of social worlds appear highly valuable for our intentions, this requires finding a way to “bring nature back in”, to come up with an analytic of the incorporated socio-ecological and of socio-ecological practices as situated in a space of social relationships with nature.

It has often been said that Distinction’s empirical account of the social space needs to be historicized, but that this does not diminish the validity of Bourdieu’s concepts. We agree inasmuch as the basic conceptions of the incorporated social and of the relational structure of the social as a space can indeed be fruitfully applied to a range of other contexts – as is being done by a whole community of researchers working in this tradition (e.g. Savage et al. Citation2014; Denord et al. Citation2011; Lebaron Citation2008; Flemmen, Jarness, and Rosenlund Citation2017; Bernhard and Schmidt-Wellenburg Citation2012). Indeed, these studies have proved most convincing and insightful when their authors found that honouring Bourdieu’s critical intentions and scientific ethos required them to re-tool and further develop his concepts, rather than simply applying them. In this vein, Lahire (Citation2010) forcefully makes the case for a more flexible understanding of habitus, and Bennett et al. (Citation2009) have demonstrated the potential of a more nuanced understanding of social inequality and cultural capital. Efforts to (re)integrate the social relevance of nature into Bourdieu’s conceptual framework, however, are extremely scant and have, to the best of our knowledge, hardly evolved beyond initial considerations on “environmental capital” (Karol and Gale Citation2004; Pini and Previte Citation2013) or on whether “view on nature” can be conceived as a field (Høyen Citation2013). Efforts to use Bourdieu’s concepts for exploring the social dynamics of ecological conflict and transformation, e.g. by discussing “ecological distinction” (Neckel Citation2018) and the relevance of habitus (Koch Citation2020; Haluza-DeLay Citation2008; Carfagna et al. Citation2014; Collins Citation2018) or practice and field dynamics (Gäbler Citation2015) mostly apply the concepts “as is”, thus remaining confined to the narrower social aspects of what are socio-ecological issues.

What insights Bourdieu’s concepts and methods can yield depends both on the type and scope of the data that they are applied to and on the theory of society that guides the choice of those data. “Bringing nature back in” thus requires two things: Building on background assumptions from a theoretical context that considers the role of nature as a constitutive element in all societalization processes, and generating or choosing the empirical basis on which to build a spatial representation of the socio-ecological in a way that will allow us to use those assumptions as a guideline in interpreting the findings. There is no purely inductive relational sociology, and explicitly spelling out the sensitizing concepts one starts from can serve to de-mystify sociological knowledge creation and render it more transparent and controllable.

4. The space of social relationships with nature

Our intention was to come up with a spatial representation of social relationships with nature by re-thinking Bourdieuian space starting from Critical Theory’s reasoning around societal nature relations, rather than from his implicit Marxian, Weberian and Durkheimian assumptions. This was not as deductive an endeavour as this may sound: We arrived at this spatial representation in an iterative process of moving back and forth between deductive (theory-based) and inductive (empirically informed) steps, drawing on both quantitative (survey) and qualitative (interview) data on socio-ecological issues, perceptions, attitudes and practices in relation to nature at various stages.

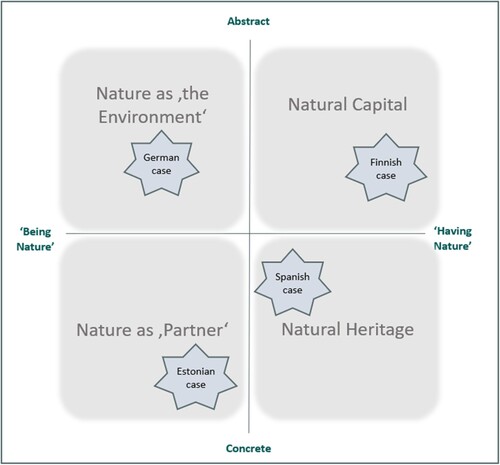

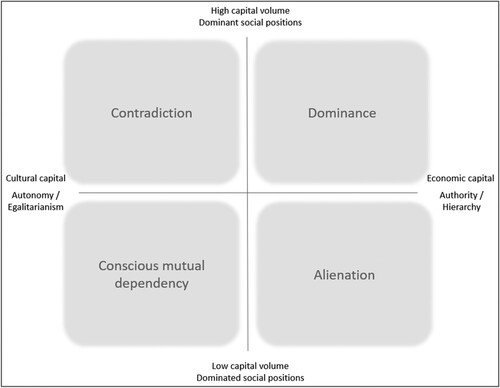

One earlier stage was Eversberg’s (Citation2021b) effort to understand the relations among ten different types of socio-ecological mentality identified in a cluster analysis of data from Germany’s 2016 Environmental Consciousness survey (BMUB and UBA Citation2017; see Eversberg Citation2020b) by locating them within Bourdieu’s social space, and then condensing the patterns found into four elementary forms of relation with nature, as seen in . This work lent sociological support to the assertion that social domination and domination of nature are intimately connected: it demonstrated that people in socially powerful positions tend to aspire to acting on nature in highly assertive, but mediated ways, be it to cater to one’s own desires or to “save the planet”, while those in precarious, subordinate positions tend to perceive themselves as dependent on nature or perceive it as an alien, threatening force. That approach has been interpreted as an attempt to derive relationships with nature from the dynamics of power and “modernization” represented by Bourdieu’s two principal axes (Spash Citation2021). Although this charge misconceives the analytical procedures deployed, it is a valid point that a spatial representation that was itself constructed in disregard of nature is ultimately insufficient for gaining a non-reductionist, relational understanding of the incorporated and practically performed socio-ecological.

Figure 2. Four elementary forms of social relation with nature within Bourdieu’s social space, adapted from Eversberg (Citation2021b).

Therefore, we found that the next stage required us to construct a spatial representation that reflects the relevance of nature in its very principle of construction. To achieve this, we found that we had to turn the sequence of analytical steps applied in that previous work around (4.1.), first exploring the socially structured variations in dispositions and practices present in our qualitative material to identify four elementary forms of people in our research field relating to nature (4.2.), and then systematically relating these in light of our theoretical knowledge about societal nature relations to redefine the two principal spatial axes so as to more adequately and comprehensively account for socio-ecological relations (4.3.).

4.1. Data and procedure

The conceptual work documented here is part of our research group’s larger research effort on the mental and practical preconditions and consequences of post-fossil transformations, and particularly of the kinds of transitions toward bio-based resources and processes discussed under the rubrum of “bioeconomy” (European Commission Citation2018; Bugge, Hansen, and Klitkou Citation2016; Hausknost et al. Citation2017).Footnote2 Empirically, our work at this stage drew on four qualitative case studies, which were selected to cover the broadest possible spectrum of bio-based sectors, approaches to bioeconomy and regional contexts within Europe: Forestry in Finland, semi-subsistence agriculture in Estonia, bioenergy villages in Germany and olive cultivation in Spain. Each case study is supported by in-depth fieldwork comprising dozens of semi-structured problem-centered interviews with local actors, observation and document analysis.

Starting from these examples, we aimed to reconstruct the structured variations in how people are involved in these practices of societalizing nature, and in how that involvement in turn shaped their subjectivities to gain an understanding of how changes in these mutual relations, i.e. social-ecological transformations, may occur. In regular meetings, we explored this by analyzing sections of interview transcripts according to the method of habitus hermeneutics (Bremer and Teiwes-Kügler Citation2013, Citation2014; Lange-Vester and Teiwes-Kügler Citation2013).

In parallel to the empirical work, we discussed a broad range of relevant theoretical literature. Apart from the work discussed in the previous two sections, this included anthropological research on conceptions of social and socio-natural relations (Douglas Citation1999; Descola Citation2013; Graeber Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Hornborg Citation2001), on (re)productivity and “caring for nature/s” (Biesecker and Hofmeister Citation2010; Hofmeister and Mölders Citation2021), on different imaginaries and visions of bioeconomy (Hausknost et al. Citation2017; Bugge, Hansen, and Klitkou Citation2016; McCormick and Kautto Citation2013), as well as on ecological mentalities (Poferl, Schilling, and Brand Citation1997; K.-W. Brand, Poferl, and Schilling Citation1998; Eversberg Citation2020b). Confronting the empirical material with what we knew from these literatures, we sought to identify structuring oppositions that regularly reappear in people’s own references to nature and in those they ascribed to others. Following the example of earlier applications of habitus hermeneutics (Bremer and Teiwes-Kügler Citation2020), we eventually narrowed these down to twelve pairs of elementary categories () as a guideline for the work of hermeneutical interpretation and of examining similarities and differences between the cases discussed. At current, we have not arrived at a full-fledged qualitative typology, but could as a first step distinguish four elementary forms of social relationship with nature, which we describe in the following subsection, providing an illustrative corner case for each.

Table 1. Elementary categories for hermeneutic interpretation of nature-related dispositions.

To come up with the spatial representation itself, we had to account for how these practices and dispositions are positioned within and toward the totality of the prevailing societal nature relations. For this purpose, we reflected on the differences between the elementary forms in light of our theoretical knowledge about societal nature relations, and drew out the conceptual implications to redefine the meaning of the two principal axes of Bourdieu’s social space, so as to account for socio-ecological, rather than narrowly social, relations. The outcome of this synthesizing step is presented in subsection 4.3.

4.2. Four elementary forms

Proceeding “in reverse” with the research strategy applied by Eversberg (Citation2021b), the first step was to explore the structuring oppositions within the empirical material, using the elementary categories, to tentatively identify four elementary forms of relationship with nature, the differences between which seemed to us to bear systematic relevance, without expecting the kind of coherence that would be required if one were to call these forms (ideal) types. The distinctions we came up with, informed by theoretical knowledge as well as by comparison between empirical cases, must thus not be mistaken as a fourfold typology, but rather as a rough initial attempt to describe basic configurations or “zones” organized by the structuring forces of what we assumed to be a continuous space of relations. The four elementary forms that we identified in this step are called “natural capital” (4.2.1.), “nature as partner” (4.2.2.), “natural heritage” (4.2.3.), and “nature as environment” (4.2.4.). Below, we give a brief outline of the typical patterns of dispositions and practices characterizing each. For purposes of illustration, we provide a short summary of one example case from our qualitative research as a box accompanying each section. While these corner cases can be allocated to one of the “zones” when considered in relation to the others, their descriptions also point to ambiguities and incoherences. This underlines the point that this is not a typology, that the differences are fluid and continuous, and that empirical cases cannot be expected to reflect the logic of a “zone” of the space in anything like a pure form.

4.2.1 Natural capital

On the one hand, social relationships with nature of the kind we call “natural capital” are characterized by privileged access to means of relating to nature in highly mediated, abstract ways: scientific knowledge, technological manipulation, economic valuation. On the other, these means are used according to an instrumental, economic rationality, to constitute nature as an abstract “resource” or commodity that can be owned and traded. Human persons can legitimately acquire nature as property, logically subsuming it to themselves and gaining full sovereignty over it in a relation of hierarchical dominium (Graeber Citation2007a). In a society dominated by market exchange, this tends to generalize into an economistic vision of nature as something to be legitimately exploited and put to use as efficiently as possible. Ultimately, as competition and rising standards of living to keep up with put owners under pressure to continuously intensify that exploitation, nature can turn from a mere resource into a capital (in the Marxian sense), asserting a factual agency of its own. This, in turn, translates into a responsibility of the owner to “put to work” this natural capital, to optimally use and increase it through investment – which again relies on abstract knowledge, technological intervention and economic calculation – to push the limits to the benefits it can deliver. Since living nature can only provide more “dead nature” to trade in if the investment increases its vitality, owners whose practice is not simply one of “using up” can normally imagine their resource management as a form of “care” and a contribution to “sustainability”, reflected in an aesthetic of “cultured”, orderly nature. Behind this lies a perception of living concrete nature as a mere limit or hurdle to human purpose, a resistance to be overcome in order to provide ever more economic value to society. This elementary form strongly resembles the dominant vision of official bioeconomy discourse, which has been termed “sustainable capital” (Hausknost et al. Citation2017; Birch, Levidow, and Papaioannou Citation2010).

Box 1: A Finnish example

“I think that this whole cluster has sort of created so much good because, at some stage, part of the people in the world say, they need board products and they need tissue products in order to, you know, to live. So, I think that they should be done the best way. And I think we pretty much know how to do them.”

The example case from Finland combines a range of specificities of Finnish forest relations with more broadly characteristic aspects of a social relationship with nature in line with the dominant bioeconomy narrative of “sustainable capital” (Birch, Levidow, and Papaioannou Citation2010; Hausknost et al. Citation2017): Forests are a resource that one’s own and the nation’s income are built on, their value is an instrumental one for humans that needs to be realized through practices of extraction and economic valorization. Our interviewee works in the management of a technologically advanced pulp factory that belongs to one of the three major pulp and paper companies in Finland and is regarded a showcase project of the country’s bioeconomy. She graduated in chemistry in the early 1980s and, after having studied and worked abroad for some time, has built her life’s career in the industry. Although she lives in the rural area where the factory is located, she presents herself as a cosmopolitan person and emphasizes her fondness of travelling and high culture activities such as the opera. Her biography appears as a tale of personal and familial progress, departing from her origins in rural Northeastern Finland, where her family have owned forest for generations. Against this background, she is familiar with concrete nature (dark forests, wild animals), knows her way around and does not mind bad weather. Also, she condemns people who (consciously) harm forests by littering. Together with her sibling, she holds the 120 hectares of forest inherited from their parents and actively manages it for logging, providing an additional source of income that she takes for granted. Nonetheless, she is convinced that as an owner it is in her best interest to take “good care of the forest”, and calls for greater appreciation of this caring service, which she claims for other Finnish forest owners and even the forestry industry as well:

“It's important that people should not have fear or agony for, that, that we are, as company or as individuals or as forest owners, that we are sort of treating our forest badly. Because we are not doing. I don't think we are doing. I truly believe that we are not doing that.”

To her, property is the way to take care of the forest, in the best interest of both people and nature. This disposition seems to at least partly stem from early experience: Even as a child, she and her parents never went into the forest just for fun, but they always had something to do there – it was work in a way. In this way, she experienced the forest as a site of enjoyment and of feeling at home, but also as a source of subsistence. What troubles her is that the young, urban generation, “those who live down there [in Helsinki, the capital]” no longer make this experience like “us who live up here [in the countryside]”, and thus cannot fully understand the connection with nature that she ascribes to ownership. That connection, however, she is determined to defend, and although she does see a need for state regulation to protect the environment, she insists on the right of property owners to exercise full authority over the nature they own:

“But still they are individual forest owners and they make their own decisions. Like myself.” … “And it's fair play, because I think nobody can say that what I am supposed to do with my own property so to say.”

This is clearly an expression of a liberal mentality that conceives of the owner as an abstract legal person to whom their property is logically subsumed, and who is entitled to exercising sovereignty over that property in the same way as over their own body (Eversberg Citation2021a; Graeber Citation2007a). Embedded within this mentality of abstraction is a self-proclaimed ethic of responsible or caring use of nature that is rooted in her own concrete experience, but which is not proclaimed a condition for the abstract sovereignty of the property owner. Rather, it is simply assumed as being generally shared as a common decency of individual and corporate actors.

This way, the apparent conflict between the owners’ private discretion over the forests’ use, their economic interests, and concerns for conservation and climate and biodiversity protection remains unaddressed. Rather, economic management is “naturalized” by defining as beautiful a forest that undergoes regular cleaning and becomes like a natural forest through human cutting, planting and fertilizing interventions. Still, she rejects the notion of the forest as a plantation, referring to the uniformity of eucalyptus plantations as an “artificial” antithesis to the “natural” Finnish forest. To her, there is no contradiction between the “naturalness” of a forest and its intense economic use.

Although she emphasizes her connection to concrete nature that she enjoys in her free time, her work in the company puts her into an abstract and mediated relationship with nature through her background in natural sciences, the highly processed character of the wood-based commodities (like pulp) the company deals in, and the schemes of economic calculation she has long learned to deploy as a manager. This involvedness in the logic and practices of making nature available to ever-increasing societal demand in both her professional role and as a private owner makes her want to believe in untapped growth opportunities: While conceding that the producibility of the Finnish forest is almost up, she still doubts that there is not room for expansion of the forest industry. Caught between the knowledge about concrete limits and the abstract logic of expansion, she stresses the need for a balance and a realistic way of planning and calculation, hoping that more high-tech forest bioeconomy projects can help achieve that. To back up this optimism, she stresses how much everything has improved and that progress has been made, e.g. in reducing pollution from paper mills. To continue along that path, she highlights a chance and responsibility to tell and teach and to advise these kinds of technology. She is proud of what the Finnish forest industry has achieved and sees further technological progress as the path to both economic success and sustainability.

4.2.2. Nature as partner

“Partnership” describes a variety of forms of reciprocal relationships with concrete nature. Practices are such that people do not experience themselves as autonomous, sovereign individual agents, but as a party to a relationship of mutual dependency. Perceiving such reciprocity requires a conception of a greater whole that the parties to the relationship are lastingly part of, and as parts of which they depend on each other. That greater whole is usually conceived as “nature” in a higher sense, inverting the hierarchical relationship with abstract nature that characterizes “natural capital”: Instead of subsuming nature to oneself as property, one perceives oneself as subsumed to nature. That greater nature (sometimes couched in terms like “pachamama” or “creation”) is not conceived in the abstract terms of society, but in the concrete imagery of community or family, within which humans’ responsibility is to contribute to the thriving of the whole to which they owe the gift of life. Nature is thus assigned an intrinsic value, because family members must not be treated instrumentally. Dispositions for such relationships are often rooted in concrete experiences in the labour of fostering and caring for human and non-human nature, i.e. of actively empowering the natural (including the human) other. The experience of embeddedness in a greater whole, usually intensely practical, tends to be incorporated in dispositions of a certain humbleness. Such relationships are often (but not always) framed in spiritual or religious terms, be it in holistic indigenous cosmologies or, more common in European contexts, in religious imagery of the “integrity of creation”. In line with a bioeconomy vision of “eco-retreat” (Hausknost et al. Citation2017), its impulse is usually to defend these communal, mutual and/or caring relationships against the eroding forces of expansionary societalization, particularly the generalization of capitalist valuation and markets.

Box 2: An Estonian example

The 52-year-old gardener interviewed in an Eastern Estonian town works in the local library and has had her own garden only for 11 years. It is located in a cooperative several kilometres outside the town, a distance she normally travels by bike. Originating from Central Asia and having studied oil refinement in Leningrad during Soviet times, she had been relocated to Estonia after her studies to work as a laboratory assistant. She has faced a multitude of difficulties in her life, including a war in her youth, the raising of four children (one of them handicapped) and the navigation of her family and household through the political turmoil, uncertainties and economic hardship of the 1990s, on which she reports in a calm and humble, but also somewhat hopeless fashion. While she could not work due to her child’s handicap, her husband went to Norway to earn money, eventually allowing them to acquire the garden. Two of her sons have moved to Germany to find work, and the third one also mostly works abroad. When we approached her for a spontaneous interview, she was initially very timid, worrying that she would have nothing valuable to tell.

Having a garden is important to her primarily because it increases the family’s economic resilience (Pungas Citation2019) in times of difficulty: Here it was impossible, there was no such money. I didn’t work, my child was disabled, so I couldn’t work. And the fruits were very expensive for the children. Having faced uncertainties time and again, the garden allows her to maintain a self-image as an active agent in spite of difficulties: We had to do it for the children, to learn how to do it [growing food]. To help the family, to help the husband. There is such Russian proverb: “A garden is a woman’s income”. But the agency it affords is not ascribed only to herself, but also to the garden itself, which, as a “steward”, provides reassurance, acting as anchor and comfort with regard to the future: If there was some sort of a collapse, I would have had somewhere to go. In this sense, her concrete experience with the garden conveys a sense of partnership: partners support and watch out for each other, and it is clear to her that this entails giving as well as taking. Mutual respect and care (work) are the basis to this specific relationship with nature, and regular, sometimes physically challenging labour at the dacha is a prerequisite for maintaining it. Furthermore, this is often accompanied by feelings of immediate concern and direct responsibility – for instance when planning the logistics of regularly watering the plants on hot summer days or asking neighbours to do so. The relationship thus follows a logic of mutuality: If you care for nature/soil, the nature/soil will also care for you. This logic is internalized as common sense on a cognitive level, but also experienced as a personal dependency emotionally: I’m working here [in the garden] – and if I stop working, I will get ill. I will wither. But now, I am busy, I am moving around, I have emotions, there is something new.

Despite these experiences of mutual dependency, her perspective both on the garden and on nature in the abstract can be said to remain mostly anthropocentric: human (or societal) needs are the priority. For instance, when asked about her opinion on the local oil shale industry – a major polluter, but also the most important employer – her preference for societal over natural concerns is clear: My son wants to go to study, but for what specialty? What profession is in demand? If he is an electrician and has to go study to become a power engineer, where will the latter go in the future in Estonia if there will be no shale oil? In light of the experienced uncertainty, the socio-economic security that the industry can provide while operating outweigh the abstract environmental benefits of its phasing out.

This contrasts with the mutuality and partnership she experiences with her garden. While the concrete nature that she can maintain an immediate practical partnership with is accessible to her as an object of concern, the “nature” that may be threatened by the pollution and the climate effects of the shale industry is an abstract object of knowledge that she cannot affectively relate to – or at least much less so than to her son as the concrete person that may be negatively impacted by its phaseout. At the same time, this does not prevent her from idealizing nature when evoked as an image of pristineness and beauty: Yes, it is on the emotional [level], you rejoice that there is such creation, that all of it has been created, that it is all so beautiful.

4.2.3. Natural heritage

Relationships with nature as “heritage” are similar to those of “partnership” in that they are framed in the concrete logic of community, but differ insofar as nature is subsumed and hierarchically subordinated to the human community, rather than the other way around. People have a connection with a very specific nature, namely their nature – the concrete beings or ecosystems that the community’s subsistence depends on –, but they are not part of it. Nature is perceived as robust and resilient, a stubborn adversary that humans constantly have to fight against, hem in and constrain, making survival a constant struggle: The ground is hard, weeds grow everywhere, animals eat everything unless you build a fence. In its own way, this “harnessing” of nature is also a practice of care: a hierarchical, paternalistic form of “caring for” a cultivated, appropriated concrete nature, the flipside of which is the exclusion, suppression, even extermination of the “wild” and uncontrolled. Nature is worked on to ensure people’s survival, and treated as an object made amenable to that purpose, not an “other” with its own subjective rights – a living force, but not a subject. People are responsible for protecting the concrete nature their community has appropriated, but not as a due to that nature itself, but to their ancestors and children. This ethic of conservation is at odds with abstract, expansionary societalization: natural heritage is concrete, as the source of your livelihood that you are to pass on to the next generation, and treating it as an object of speculation to optimize for increased added value would endanger the collective subsistence. The economic logic of “working the land” or “living from nature” is instrumental, but based on use rather than exchange value, an instrumentalism of necessity rather than expansionary aspiration. However, it is vulnerable to colonization by the logic of “natural capital”: Technology promises to alleviate the hardship of maintaining the heritage, and with investment in tractors and machinery often comes the dependency on abstract market exchange, credit, and the need to enter an expansive trajectory (Bourdieu Citation2008). Thus made dependent on the mechanisms of societalization that destroy the heritage, the resentment against the “uniting” (Bourdieu Citation2008, Citation2003) forces of economization is easily redirected into opposition against the political dimensions of these processes (bureaucracy, taxation, dominance of urban elites).

As an extended part of the family and its history, natural heritage also needs to be defended like a family member. In extreme forms, this blends into nationalist and fascist ideologies of “blood and soil”, which draw heavily on people identifying with their respective homelands and considering them “their own”. Despite the ecological rhetoric sometimes used, the soil and the land in these visions are subsumed – as a “national heritage” – to the imagined community of the “people” that receives its greatness from precisely that subsumption. Beyond their practical function as means of subsistence, the concrete, distinctive features of the landscapes that a “people” have appropriated are ascribed a symbolic value that is not intrinsic to nature itself, but valued precisely as the product of the act of appropriation. In fascist mentalities, the notion of nature as adversary is also radicalized into the imaginary of a constant war for scarce means of survival, in which not only wild nature, but also those “uncivilized” others that racist patterns of perception associate with them appear as threats to the community that must be rooted out. The right to exist and thrive is ascribed to the ability to fight and win against nature, through which a people “moves up” in the natural order. Accordingly, hierarchy and domination are perceived as generally justified, as dictated by nature itself.

Box 3: A Spanish example

“The monoculture, if you do it well, is good, like, I have my olive grove, but I maintain a biodiversity of plants that don’t bother me. I don’t think there are bad plants, I think there are plants that interest you more and others that you care less about […].”

This citation is from a farmer from Southern Spain, talking about his relation to his olive grove. He cares about the grove’s concrete nature in much the same way he cares about the house he inhabits: Passed down from his great-grandfather, it has value, but that value stems from the family’s earlier investments and primarily lies in its usefulness to him and the family. Although he feels a deep connection with the grove, this is essentially instrumental: Investing time and money to preserve the cultivated nature of the grove means protecting the family and its history: the relation follows the hierarchical logic of property, but the subject to whom it is subsumed is not the individual, but the group whose subsistence it has to guarantee. Passed down as a tradition within the group, the practice of monocultures is considered a threat to biodiversity, but an accustomed right: because the human community is the frame of reference, its needs are what counts, and biodiversity is accepted only as long as it does not put these in question.

Having grown up in Madrid (but spent all vacations in the countryside) and moved back into his great-grandfather’s house only after losing his job in the crisis of 2008, aware, but most of the time removed from the hardships of life in rural Southern Spain. While many villages and farms there still had no running water or electricity during his childhood, the contrast between this and the experience of living in the comfort of the capital coined his view of life in proximity to concrete nature. It is therefore not surprising that he summarizes his childhood memories of the family’s rural home region in the one word poverty. From his view, families’ existence as olive cultivators was a permanent struggle for survival, and the whole region’s economy an economy of survival.

Describing himself as a very busy worker and comparing his old job as an engineer with his new life as a farmer, he returns to this motive: At times, life appears quiet, when there is no harvest season and nothing to prepare for the next harvest. But one mistake can ruin a year’s whole income. This is due to the dependency on the concrete: Whereas in his previous job, mistakes he made in his abstract knowledge work could be fixed within a day, faulty decisions about the grove can have grave consequences for at least a year. Therefore, careful planning and meticulous execution of each step is essential, lest one endanger the family’s economic existence.

Quite contrary to what the experience of an engineer might dispose one to do, this need for diligence forbids risky investments in new technologies, and bars a cultivator like him from viewing the grove as a capital. Growing olives on a slope and using traditional forms of cultivation, he is very critical of big firms and landowners who use the land to maximize profit, because he fears that their practices of highly mechanized and fertilized cultivation are likely to become unproductive due to intensifying water scarcity, eventually leading to the abandonment and desertification of the land.

“[…] and it will stay a product of survival for the good of nature, for sure, because people will have it as a forest. So, the best solution the olive grove has is climate change, because [with it] there will be no more business and it will begin to be … come back to being a crop.”

Interestingly, thus, the “economy of survival” seems to be a good thing to him, which he hopes can be reinstated as the standard way of doing things following a future collapse of big business: Climate change (a societal, not a natural process) could be the “solution” because it speeds up the process of olives becoming, once again, a crop that ensures survival instead of generating a profit. For this to happen, the subsumption of concrete olive cultivation to the purposes of abstract economic growth must end. The agency that could achieve this, however, is located in the impersonal consequences of an anonymous process: By framing things this way, he puts himself in a sort of precarious position with little to no power to change things. Therefore, a global and long-term phenomenon such as climate change is, in his mind, the best hope of change. This disposition may originate in his experience of economic precarity in the 2008 crisis, combined with the inherited ethic of “survival”: Having personally felt that the city’s promises of abstract expansion were unkept, the “traditional” orientations of the rural family reemerge as a guideline for a harder, but more predictable and “honest” way.

In this particular case, the distinctions from both “natural capital” and “nature as partner” are rather subtle. The olive grower cannot operate outside a logic of economic calculation, because fluctuations in world market prices also affect the way that farming is perceived, albeit on a far smaller scale than in the Finnish case. The difference is the degree of abstractness and concretion: While in the Finnish case, the sentiment and attitude toward the forest are pervaded by a logic of investment, here the olive grove is perhaps better described as a “passive” stock, an insurance, rather than an “active” capital. There is also a degree of proximity to “nature as partner” in terms of a basic respect for species that are not immediately “useful”, and an acceptance of some degree of “wildness” alongside the cultivated nature. The case is thus located at a considerable distance from the authoritarian and nationalist versions of such mentalities (as evidenced by his critique of the market, rather than the state, as a force of abstraction).

4.2.4. Nature as environment

In this fourth elementary form, high degrees of education and the command of abstract scientific knowledge allow for a global perspective on nature as a fragile, endangered “planet” (Chakrabarty Citation2020) or “biosphere”, of which humanity and its economic activity are a part. People relating to nature this way are actively aware of discourses surrounding “sustainability” and tend to think about nature from the perspective of abstract society rather than concrete community. Seen from a global perspective, people appear as dependent on nature, and need to adapt to its boundaries to survive, but that adaptation must happen at the societal level, through structural changes guided by systemic knowledge, or the scientific design of “sustainable” nature relations. Political action appears as a social responsibility for the preservation of "the planet" or “the environment” as everybody’s basis of life.

To the lens of science, to the reliance on measurements showing nature to be fragile and endangered, correspond aesthetic dispositions that, from an equally “detached” vantage point, aestheticize nature as an authentic “wilderness” to be conserved. While people do make practical experiences with concrete nature, these are typically not ones of everyday interaction and direct economic dependency, but of extraordinary intensity and enjoyment in situations of leisure and adventure (cf. Bourdieu Citation1984, 219–220). These activities are an expression of a structural contradiction (Eversberg Citation2021b): Possessing the cognitive means to grasp the ecological crisis as a societal problem strongly correlates with the material status that allows for the resource-intensive travel and invasive sports activities that enable “authentic” experiences of idealized nature, and that (often commodified) experience itself generates a consciousness of being both a “lover of nature” and in practical control of its forces (as a climber, mountainbiker, surfer …), as one is used to being in control of others in social life. On this double-edged experience can grow the desire to believe that society, too, can achieve the feat of having nature’s cake and eating it, and thus an affinity to promises that adaptation to nature can be achieved through strategies of “green growth”.

Box 4: A German example

“And since I, um, had always been involved in the issue of let’s say, the whole world in its interconnections, um perhaps also a little bit in, well, came from the environmental movement a bit, and, um, that of course was in some sense a starting point for me to say: what do you do with this village?”

The mayor of an East German bioenergy village is a trained teacher and has studied and taught Russian as well as history during socialist times. As a member of the environmental movement and an unruly pedagogue, he entertained a conflictual relationship with the GDR authorities, which led to his being relocated to a Thuringian village in the 1980s. He quickly gained a foothold there and was elected for mayor shortly after unification. To understand what he was doing, he then studied administration. In the course of three decades, he has been dedicated to making the then run-down municipality an attractive place to live. To this end, he has sought to establish the village as a family – and environmentally friendly community and to foster residents’ active participation in municipal life. Seeking out ever new “projects” for the community to rally around and mobilizing funding to palpably improve local quality of life, he has played the key role in turning the village into a prospering place that has attracted many young families, and built significant trust and well-functioning networks in regional and state-level politics as well as with local business. His education and the experience of helping topple an authoritarian regime as well as his increasing social capital have provided him with a consciousness of being able to actively shape his environment, and he has been determined to use this to live up to his eco-social ideals. Although he hardly talks about nature at all in the interview, the holistic view hinted at in the above quote, based on a broad knowledge of the sciences and humanities, forms a self-evident backdrop to his thinking. His political view that ecology, democratization and social justice go hand in hand and that the local contributes to a change sought globally is one expression of this disposition toward systemic or “wholesome” thinking that also seems to guide his way of dealing with local issues, problems and interests. He constantly seeks to relate different actors’ concerns as well as those of nature in the concrete and the abstract to larger contexts and to seek integrated solutions that can bring together the seemingly disparate in a common, uniting project.

The most outstanding example of this is the establishment of a cooperative for local energy production in the early 2000s, branding the municipality as one of the first “bioenergy villages” in Eastern Germany. Far from just a “technical” project to supply residents with locally and sustainably generated energy, the idea of forming a cooperative to build and manage a bioenergy plant that would be fed with manure and agricultural residues from the neighbouring agricultural cooperative and provide heat and power to households was, to him, directed at a comprehensive social-ecological transformation of the community, encompassing the physical makeup of its infrastructure, its institutional forms and informal relations. As a collective project, it was conceived to address a host of different concerns at the same time: sustainable energy provision, democratization of infrastructure, community building, local value generation, stabilization of the local agricultural cooperative, raising tax revenue for the municipality, putting local waste streams to use, etc. Economic considerations, though important for the viability of the project, are but one among a long list of criteria for the cooperative’s decisions, and have been overruled time and again by other concerns deemed more important.

But the relevance he ascribes to the project extends beyond the concrete realm of the community, and to the societal level: Considering energy supply a public responsibility, and disappointed about the federal government’s strategy of privatization and liberalization, he wanted to contribute to a counter-movement of communities taking the issue into their own hands and cooperatively organizing their own energy supply based on locally available renewable resources. As a model community demonstrating the feasibility of a sustainable and democratic alternative, he hopes to not only incite others to follow suit, but also to help push for national-level regulation favouring this kind of arrangement as a standard model of energy provision. Also, he sees cooperative projects of this kind as a means to counter the democratic deficit that he perceives in eastern Germany. Although the community plays a central role in his thinking as a subject of local responsibility and democratic autonomy, it is part of a thoroughly political strategy ultimately aiming at societal change. For him, the local community can be an important site of implementing change in the societal nature relations, but this must ultimately be part of a multi-level political strategy, rather than an uncoordinated bottom-up process. In other words, he translates his holist cosmology into concepts for redesigning social and socio-natural relations which are articulated as a reflexive political strategy rather than an immediately practical ethos.

What frustrates him most is that his visions and his broad-minded thinking, though supported by many, haven’t been adopted by the community as a whole. He expresses outright incomprehension toward the “peasant thinking” of some whom he perceives to be fixated on their own property and livelihood only, disregarding the interdependencies with others he is so keen to stress. But even among those that participate in the collective effort, he is constantly concerned that their motivation may wane and that they could retreat into the private sphere: “What I’m kind of missing in hindsight, is, as I said, to carry, carry forward that, that idea of the cooperative, also for, for other projects, right?” Still, he believes that the best way to win people over for the kind of societal transformation he envisions is to enable them to participate in the experience of having collectively achieved something, even if their motives were much more prosaic than his own:

“But they took part in the process, that’s what I consider really, really important, and um, you mustn’t overstretch it, and you can’t ask too much of everybody and say, hey, now this is, um, and now you all have to become do-gooders and saviours of the world, that won’t work anyway”

Yet despite this acceptance of people’s particular motives for participating in what he pursues from a universalist point of view, he does not resign to a “pragmatism” that simply takes things as they are: disgruntled about the continuing dominance of the automobile in rural mobility, he has not only established a “citizens’ bus” operated by volunteers to connect the village to the next larger town, but is currently working to establish a car sharing model for the municipality. If I can't prevent them from going on cruises, he at least wants to work to provide alternatives that make a different mode of living practically possible.

4.3. The basic structure of the space

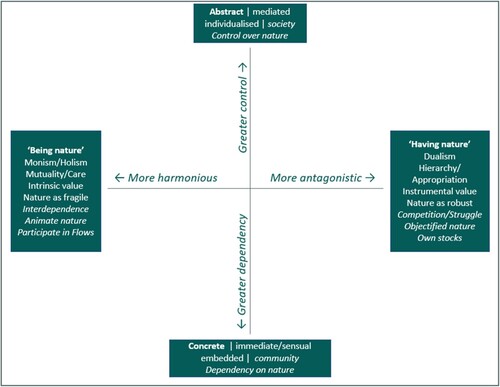

To finally come up with a spatial representation of the societal dynamics that structure social relationships with nature, it was necessary to again relate these four elementary forms to each other within the broader theoretical context. The task was to find oppositions of a higher order that would allow us to trace their differences and complementarities to the ordering principles of the incorporated and practically performed socio-ecological as structured by a fossil-based, capitalist, expansionary mode of societalization. In line with the Bourdieuian tradition, which assumes the distribution of different capitals to be homologous to that of different logics of social relationships (Bourdieu Citation1984; Vester et al. Citation2001), we expected a similar correspondence between positions within and toward the societal nature relations and incorporated logics of relating to nature. However, coming to terms with the positional structure of socio-ecological space required one important reconsideration concerning Bourdieu’s notion of capital. To account for distributive inequalities within social relations while also remaining sensitive to the role of extra-human nature, we found that we needed to reconstruct the distribution not simply of reified “means of power” that could be possessed, but – in accordance with Marx’s notion of capital as a relation – of control over socially accumulated stocks of “dead labour” and “dead nature” as well as of access to the flows of living labour and nature harnessed by societalization processes, in its homologous relations with socio-ecologically typical patterns of dispositions and practices. Following this conceptual adjustment, we expected the space of social relationships with nature to in some respects be homologous with Bourdieu’s social space, but heterologous in others. In this vein, we found that the four elementary forms of relationship with nature could be grouped in 2 × 2 pairs according to their similarities and differences along two axes that gain their meaning not only from this grouping exercise, but also from the theoretical frameworks we drew on as guiding concepts. Therefore, despite the seemingly simplistic juxtaposition of these four forms in , we insist that this is not to be read as a fourfold system of “drawers” to put people into, but merely as a way of identifying the principal continua that account for the regularities of socio-ecological structure.

At this point, we can no longer dodge the question of what that “nature” is that people relate to. As the whole point of societalization processes is to supplant concrete existence with a second, abstract existence, our understanding of nature needs to account for that dual character. The concrete nature that we observe our research subjects relating to is the extra-human substances and objects involved in their economic activities (forests, gardens, manure and agricultural residues, olive trees …), whose specific properties are crucial to their livelihood and are the object of sensual and practical experience. Abstract nature is constituted by the conceptual representations, scientific measures and economic valuations produced in processes of societalization, which serve to make nature, as “that which is not amenable to change by way of communicative acts” (Dath and Kirchner Citation2012), fungible to society. To relate to nature in an abstract mode is to draw on these mediated forms of vision as an incorporated disposition, and to engage in practices enabled by that scientifically, technologically and economically mediated fungibility.

Empirically, concrete and abstract ways of relating to nature are intertwined and inseparable from each other, and the way they mix is one core distinguishing feature of social relationships with nature. Now, comparing our four elementary forms of relationship with nature, it is rather evident that relating to nature as “the environment” and as “natural capital” are predominantly abstract, “societal” ways of doing so, while “nature as partner” and “natural heritage” are situated at the level of concrete community. Building on our above argument that the distribution we need to understand is that of access to the means of societal abstraction, we find this to be largely homologous with the vertical dimension of social space. As being socially powerful means to have greater means of mediation at one’s disposal, powerful social agents also typically act at greater distance from sensory-motor interaction with nature, and are more accustomed to thinking about nature (and society) in abstract, scientific or economic, terms. The privileged access to the accumulated knowledge, institutional capacities and technological infrastructures of society is typically internalized as the habit of taking for granted an extraordinarily high “world reach” (Rosa Citation2019). Conversely, practices that come with more direct sensory and physical experiences with concrete nature and dispositions toward the concrete relational patterns of community, are socially devalued and therefore typical to subordinate social positions.