Abstract

Nomadic pastoralism is of vital importance for grasslands worldwide. As one of the largest, widely intact, temperate grasslands in the world, the eastern Mongolian steppe looks back on a millennia-old tradition of nomadic pastoralism. Thus, this type of use of the ecosystem plays an important role in providing and maintaining ecosystem functions, e.g. seed dispersal, nutrient distribution and composition of plant communities. In addition, the nomadic way of life has important cultural and social functions. Global change processes like urbanisation, globalisation, digitalisation and climate change confront societies worldwide with the need for substantial sustainability transformations. While pastoralists are also strongly affected by these changes, their experiences and way of life, which have been evolving and adapting for millennia, can prove very helpful in addressing the transformation challenges. With this paper, we aim to reflect a new form of nomadic pastoralism for Mongolia in the twenty-first century. Implementing a transdisciplinary research process, we conducted a series of stakeholder workshops, surveys and co-writing periods, involving pastoralists, local and national authorities, economic and conservation actors, as well as scientific project partners from a wide range of disciplines. In doing so, we developed exploratory scenarios of contrasting plausible futures of the Mongolian steppe.

1. Introduction

The eastern Mongolian steppe has a millennia-old history of (semi-)nomadic pastoralism (Honeychurch Citation2014) that has significantly shaped the local social-ecological system (SES). Throughout this time, the SES has undergone a number of changes and it is not only due to the ever-improving data that since the twentieth century the political drivers of change have led to several fundamental changes (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2017). Both, the socialist state and the transformation to a democratic political and a capitalist economic system led to severe turbulence in a system that has adapted to permanent fluctuations caused by ever-changing climatic, ecological and sociopolitical conditions (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2019). The turn of the twenty-first century does not seem to put an end to this period of profound change: Urbanisation and globalisation (Fan, Chen, and John Citation2016; Chen et al. Citation2018) as well as climate change (Ahlborn et al. Citation2020; Mijiddorj et al. Citation2020) will not miss their strong influence on either environmental or social structures and processes. This profound change, however, calls into question the continued existence of nomadic pastoralism, which, as part of the traditional way of living, is under pressure (Neve et al. Citation2017). The main question is how to preserve the steppe ecosystem and its sustainable use through forms of traditional pastoralism. Due to the pastoralists close connection with the ecosystem, they shape their own and the cultural identity of the whole country (Kassam, Liao, and Dong Citation2016). Moreover, while the exact impact of pastoralists on the steppe ecosystem, especially in terms of the grazing effect, is contested (Munkhzul et al. Citation2021), they definitely play an important role in the processes of the ecosystem (e.g. seed dispersal, competition between trees and grasses, outbreaks of wildfire). Taking this part out of the equation will have consequences on ecosystem functions and biodiversity that are difficult to predict (Pachzelt et al. Citation2015; Pfeiffer et al. Citation2018). Thus, efforts should ensure that a new form of nomadic pastoralism, adapted to the twenty-first century, remains an attractive option, despite the possible lure of an urban lifestyle.

Notions of ‘Anthropocene’ and ‘Planetary boundaries’ illustrate the importance of the aforementioned global drivers and, at the same time, the urgency of sustainability transformations (Pichler et al. Citation2017). The case of pastoralism in grasslands worldwide and in Mongolia in particular are prime examples for analysing transformations in SES, due to a number of reasons: (i) Grasslands cover substantial parts of the land surface on Earth; (ii) They exhibit close linkages between societal and natural processes, (iii) high levels of environmental volatility and of adaptability of people and nature together with (iv) a great diversity of livelihood strategies and, finally, (v) traditional ecological or indigenous knowledge still plays an important role (Reid, Fernández-Giménez, and Galvin Citation2014). As it has developed and permanently adapted against the background of local conditions, indigenous knowledge often gives rise to a sustainable relation to nature (Jamsranjav et al. Citation2019; Mistry and Berardi Citation2016) and is therefore of great importance for sustainability transformations (Lam et al. Citation2020; Matias Citation2021).

Against this background, with our study, we aim to develop future scenarios for societal transformations (Hichert et al. Citation2021). The transdisciplinary developments of future scenarios can help to open the range of imaginable and possible futures by stimulating ‘reflexivity, creative thinking, and raising awareness about the future of the social-ecological system’ (Oteros-Rozas et al. Citation2015). By integrating diverse expertise from local (herders) to national (governmental organisations) and international stakeholders (non-governmental organisations) and types of knowledge (practical and scientific knowledge) the exploratory scenarios help us to create orientation knowledge. Orientation knowledge is essential to assess the opportunities and constraints of future developments (see Jahn, Bergmann, and Keil Citation2012) as an important prerequisite for sustainability transitions (Wiek, Binder, and Scholz Citation2006). While the Mongolian government focussed on favourable progressions by formulating a comprehensive vision for Mongolia’s development in the next 30 years (Government of Mongolia Citation2021), we aim to shed light to a range of possible developments. Furthermore, we align our scenarios with the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) (O’Neill et al. Citation2017) to provide a link to work in climate science, whose results regarding the impact of climate change will be of high relevance for Mongolia.

After describing the status quo of the SES as the starting point for future developments (Section 2), we introduce our methodological approach (Section 3) to identify key transformation factors used to formulate differing future scenarios (both described in Section 4). Finally, we discuss the potential of our results to serve as a ‘roadmap for the future’ (Section 5) and conclude with an outlook on the potential of a renewed form of nomadic pastoralism and of transdisciplinary scenario building (Section 6).

2. The social-ecological system of the eastern Mongolian steppe

The eastern Mongolian steppe ecosystem is one of the last remaining intact steppe ecosystems in the world, in which the dominant human activity (in particular nomadic pastoralism) is largely in accordance with ecosystem processes, as both have co-evolved for millennia (Batsaikhan et al. Citation2014; Reid, Fernández-Giménez, and Galvin Citation2014). However, due to increasing disturbances and fragmentation, particularly as a result of the industrial development (Dashpurev, Bendix, and Lehnert Citation2020; Nandintsetseg et al. Citation2019), the system is under threat. Conceptualising the region as an SES, where ecological and social structures and processes are closely interrelated (Becker Citation2012), helps to describe and better understand the current problem and analyse its key mechanisms (Hummel, Jahn, and Schramm Citation2011).

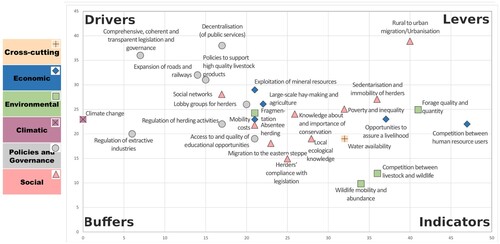

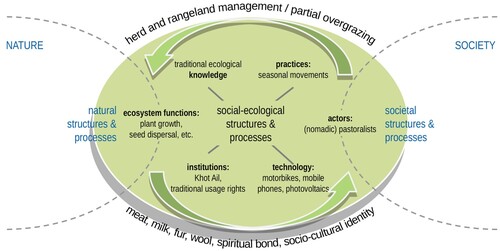

In our study, we focus on (semi)nomadic pastoralists as main (human) actors of this SES (), who historically played the key role and who still play a decisive role in shaping the steppe ecosystem today by managing livestock herds and rangeland (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2017). Through this type of use, which can also have undesirable effects such as local overgrazing (Tuvshintogtokh and Ariungerel Citation2013), pastoralists use ecosystem functions such as plant growth and seed dispersal to obtain essential resources for their animals. The benefits they receive for their subsistence, for economic activities and on a socio-cultural level are manifested both in products such as meat, milk, hides, wool, but also in spiritual bonds and identity formation. Besides these ecosystem services, disservices can also occur, for example as drought, (livestock) diseases and extreme winters (dzuds). This basic interplay between society and nature is determined by social-ecological structures and processes that can be characterised by four hybrid dimensions, all of them are shaped by the interaction of social and natural conditions (Liehr et al. Citation2017). The pastoralists knowledge of, for instance, grazing grounds, water sources, weather forecasts and symptoms of livestock diseases are a form of traditional ecological knowledge (Soma and Schlecht Citation2018). Of course, this knowledge is not purely traditional and static, but is continually evolving and is expressed in everyday practices, such as seasonal movements (Jamsranjav et al. Citation2019). In this context, formal and informal institutions such as the cooperative encampments of several households – the so-called Khot Ails – and land property and land use rights also play a crucial role (Murphy Citation2015; Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2015). Finally, technologies such as mobile phones, motorbikes and small photovoltaic systems are shaping the daily lives and management strategies of pastoralists in the eastern Mongolian steppe (People in Need, Mercy Corps, and The Food Economy Group Citation2018).

Figure 1. SES of the eastern Mongolian steppe (modified after: Mehring et al. Citation2017 and Mehring et al. Citation2018b).

2.1 Volatility of the SES

Although the main processes of the SES are relatively steady, there are of course dynamics over space and time on the societal (e.g. herding practices) as well as on the natural side (e.g. vegetation dynamics), both of which influence each other (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2018; Lamchin et al. Citation2015; John et al. Citation2016). The overall trend of a moderate level of pressure on the ecosystem is reflected in observations of increasing values of canopy cover and aboveground biomass over the past 20 years (John et al. Citation2018) and can partly be explained by a continued net out-migration from the eastern provinces (aimags) mainly to Ulaanbaatar (Chen et al. Citation2018): While the number of migrants to the eastern region, which comprises the aimags Dornod, Suukhbaatar and Khentii, was on a low level during most of the first decade of the twenty-first century, it increased again in the second decade (National Statistics Office of Mongolia Citation2021a). In comparison, the number of people leaving the eastern region remained at a very stable level, declining slowly only in the second half of the this decade (National Statistics Office of Mongolia Citation2021a). Although some studies assume a concurrent decline in livestock numbers and thus grazing pressure (Chen et al. Citation2018; John et al. Citation2018), official national statistics show a constant increase in livestock numbers over the entire period (National Statistics Office of Mongolia Citation2021b). Therefore, despite the decreasing population density, the livestock numbers speak against a general relief of the ecosystem and rather for a concentration of grazing pressure in certain areas (Mehring et al. Citation2018a). Overall, we must assume that vegetation and soil respond in a complex manner to the spatially and temporally varying grazing pressure (Wang and Wesche Citation2016) and while the impact on vegetation cover and biomass appears to be low (at least at higher spatial and temporal scales), changes in composition and richness of plant communities are apparent (Jamiyansharav et al. Citation2018; Khishigbayar et al. Citation2015).

If we return our focus to the structures and processes of the SES, we see volatilities in all four dimensions. With regard to knowledge, for example, the strong influence of the aforementioned migration movements becomes apparent. As pastoralism becomes less attractive and adequate, it is often no longer the main occupation for the younger generation. With the migration of parts of this population group from rural areas and the increase in absentee herders, traditional ecological knowledge is being lost among the former and changed among the latter (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, herders report that the (intergenerational) acquisition of traditional knowledge for questions of weather forecasting or the veterinary use of herbs is still important. In contrast, (intragenerational) exchange on issues related to herd management and pasture rotation is of increasing importance because the knowledge of the older generation can no longer be reliably applied under changing conditions. In addition, the younger generation is taking new approaches in some problem situations, for example when they are searching less for the right pasture for the animals and more for the right livestock breed for the pasture. Absentee herding, the (additional) keeping of other peoples’ animals also influences everyday practices, which often thus go beyond mere subsistence. Moreover, depending on the local conditions, practices like hunting, fishing, agriculture and gathering of wild plants complements herding activities (Honeychurch Citation2015). Obviously, these outlined developments also bring change to informal institutions and regulations. However, also legislation is subject to change, which for instance has led to ‘two major laws – the Law on Land (1994) and the Law on Allocation of Land to Mongolian Citizens for Ownership (2002) – [which in turn] have been […] promoting rural-to-urban migration’ (Chen et al. Citation2018, 9). In terms of technology, the popularity of smart phones, the expansion of network coverage and the associated access to information, knowledge and social contacts are currently of particular importance (Chen et al. Citation2018; Matias et al. Citation2020).

Thus we can state that the millennia-old tradition of Mongolian nomadic pastoralism is always accompanied by a high degree of flexibility and adaptability (Konagaya and Maekawa Citation2013), which in view of the potential ‘game changers’ of globalisation, urbanisation and climate change may be more in demand than ever before (Fernández-Giménez, Batjav, and Baival Citation2012).

Given these circumstances, it is important not only to look at the risks and the problems to be avoided, but more importantly at the opportunities and options for progression. ‘[T]he overarching aim of scenario development is to ‘work’ with and ‘learn’ from reflecting on the future in order to make better decisions and choices in the present’ (Hichert et al. Citation2021, 165), because imagining a better future alone will have no effect unless it stimulates to actively tackle shaping tasks in the present (Jahn et al. Citation2020). However, in order to achieve this it is important to include those stakeholders that possess a certain influence, power and will to shape the process, usually because they will be affected by the outcomes themselves (Oteros-Rozas et al. Citation2015). In the following, we describe the methodological procedure to involve these actors and diverse types of knowledge.

3. Methodology

Being embedded in the transdisciplinary research project ‘MORE STEP’ (‘Mobility at risk: Sustaining the Mongolian Steppe Ecosystem’), the scenario development can itself be conceived as a transdisciplinary process. Starting from a societal problem, this is related to existing scientific knowledge and transformed into a shared problem in order to create new knowledge that can be fed back into both the societal and the scientific discourse (Jahn, Bergmann, and Keil Citation2012). In this case, this means that the search for a nomadic pastoralism of the twenty-first century is backed by existing (scientific) system knowledge and diverging scenario storylines are created by integrating different forms of scientific and non-scientific knowledge. These storylines serve as (new) orientation knowledge to feed back into society in order to inspire integrative, transformative processes. Besides, the key factors that shape possible future developments as drivers, levers or indicators are identified and, at the same time, structure the outline of the different scenarios. The scientific practice can draw from the storylines and the identified key factors to translate them into inputs for different computational models. However, in the context of this work, the focus is on the description and analysis of the scenarios and key factors.

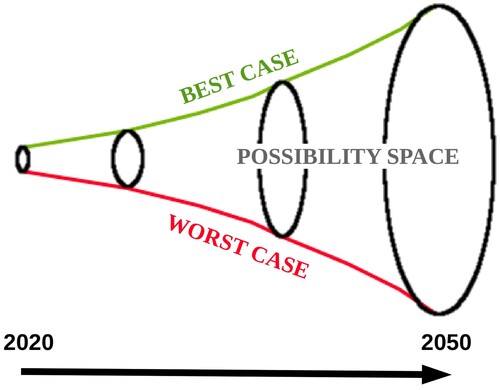

The entire scenario development was implemented as a transdisciplinary process in the course of the research project, with a series of workshops at national level and regional workshops at provincial level. In a first workshop in 2017 stakeholders were identified and classified according to their relevance for and own interest into the project (Mehring et al. Citation2018b). The second stakeholder workshop in the series at state level was held in Ulaanbaatar in 2019. This workshop aimed at identifying decisive factors for future scenarios and at making first steps to develop a shared vision of a desirable future to guide further action towards social-ecological transformations (Matias et al. Citation2020). In diverse small groups, the participants of the stakeholder workshop (see for a list of stakeholders involved) discussed and outlined a potential worst case state and a potential best case state of the system in 30 years from now. These served to sketch the range of possible developments as in the image of an inverted passage through a funnel (Kosow and Gaßner Citation2008). Following this picture, the best and worst cases move further and further away from each other over time (). At the same time, the uncertainties increase as the opening of the funnel widens and the possibility space for all scenarios between these extremes expands. The key factors we identified can actively steer future development and serve to analytically determine the relative position within this possibility space.

Figure 2. Best case (upper/green line) and worst case (lower/red line) scenarios form a funnel with a widening possibility range from 2020 to 2050.

Table 1. List of participating stakeholders in the second workshop and of disciplinary backgrounds of the project consortium

Working in an inter- and transdisciplinary research team (see for scientific and practical expertise coming together in the team) that also includes practice partners from Mongolia, we subsequently evaluated and discussed the scenarios in the team. Each project partner was asked to answer a questionnaire with mainly open-ended questions, in which they had to estimate the effect of the key factors, identified in the first stakeholder workshop, on the main subject of their field. In addition, with the questionnaire we aimed to delve deeper into the details of the worst and best-case scenarios as well as a third scenario, which is oriented towards a realistic development from the expert's point of view.

Based on a content analysis of the completed questionnaires and the outcomes of the second stakeholder workshop (Matias et al. Citation2020), the results of the workshop were expanded to identify the most important factors for the scenarios and to classify them in thematic fields (see Section 4.2). These thematic fields comprise the ‘classic’ sustainability dimensions social, environmental and economic as well as policies and governance. Further fields were defined in the course of the analysis. The subsequent methodological steps served to find a clustering of these factors that goes beyond a thematic differentiation, but rather helps to reveal the factors’ importance for the system development. For this purpose, we applied a variant of the impact matrix of the sensitivity model by Vester (Citation1988). We paired all factors with each other and estimated the influence of the vertically listed factors on the horizontally listed factors in the matrix on a scale from 0 (no influence) to 3 (strong influence), based on the questionnaires. In addition, we added algebraic signs to the scale values in order to distinguish between a negative and a positive influence. The summed absolute values per matrix row indicate the relative strength of influence of the factors on other factors (active sum) and the summed absolute values per column indicate the relative strength of influences experienced by the factors (passive sum) (Huang et al. Citation2009). With these two values (active and passive sum), the factors can be located in a two-dimensional coordinate system whose corners represent ideal-typical systemic roles. Factors with low active and passive sum ‘buffer’ the system, a high active sum and low passive sum are active ‘drivers’, the reverse case represents reactive system ‘indicators’ and a high active and high passive sum indicates critical factors that are important ‘levers’ in the system (Huang et al. Citation2009). The grouping according to the thematic fields and the concentration on the factors with prominent systemic roles finally provided the structure and orientation for the formulation of the scenario storylines.

Classifying this methodological procedure on the basis of the frequently used scenario typology by Börjeson and colleagues (Citation2006), we see a combination of different types in the synopsis of the individual methodological steps. Defining the guard rails for the possible futures with a best-case and a worst-case scenario is closest to the category of ‘normative scenarios’. In contrast, the subsequent expert assessment of a realistic future development quite precisely describes the question ‘What will happen, on the condition that the likely development unfolds?’ (Börjeson et al. Citation2006, 726) and thus corresponds to the scenario type ‘forecast’ of the category of ‘predictive scenarios’. Finally, the expert assessment of the key factors can be assigned to the third category ‘exploratory scenarios’ (Börjeson et al. Citation2006).

4. Future scenarios and their main drivers

4.1. The stakeholders’ perspective

During the workshops it became clear that the participants developed a common picture on many points, but that at the same time valuation and prioritisation of topics and problem areas differed between the groups. National governmental agencies usually focussed on the question on how to protect land and preserving its uniqueness by regulating livestock numbers and access to pastures, designating areas for nature conservation and by the introducing and licencing of grazing reserves.

Local authorities showed a strong interest in improving herders’ livelihoods by providing access to key infrastructure like health service and education and by supporting young families with restocking programmes for their herds so that they do not leave for the city. In order to realise such projects they demand financial support from the national government.

Workshops participants from academia and NGOs demonstrated the greatest interest in reducing the grazing pressure on pasture and favoured ideas like providing trainings to herders, introducing new animal breeds, creating and connecting nature reserves and motivating herders to organise in (pasture user) groups for a better coordination of pasture use.

Although participating herders agreed to most of these ideas, it became apparent that their focus differed a lot. This did not primarily concern the thematic focus, but the tension between conception and practice, and between long-term strategy and pragmatic short-term solutions. Because they regularly have to make decisions that affect the survival of their animals and their family, ‘simple’ solutions such as increasing the size of the herd are often the only realistic option. Furthermore, preventing the spread of livestock diseases was one of the most important issues for them. There was also no fundamental disagreement on the importance of nature conservation, but many herders take the position that their use of grassland also has a conserving function. Thus, additional measures would only be necessary when it comes to compensation for industrial activities and mining, for example.

The joint assessment of key factors for future development was the main result of the 2019 stakeholder workshop (see Matias et al. Citation2020) and was the first step of the scenario development process. Key factors that workshop participants rated as most decisive for a positive and desirable future belonged to the fields ‘legislation and governance’ and ‘education’. Important factors to foster a positive change in these fields are, on the one hand, a comprehensive legislation, good and transparent governance, effective law enforcement and a (particularly infrastructural) decentralisation. On the other hand, far-reaching educational reform and capacity building in different sectors are considered important. In addition, better market access for pastoralists, the promotion of high-quality livestock products, more consistent regulation of the mining sector and climate- and environment-friendly changes in the energy and transport sectors are factors that affect further fields.

Key factors that, according to the workshop participants, would forward unfavourable future developments are primarily those that increase the pressure on natural resources. Climate change, a lack of public control over the extraction of fossil resources and overpopulation of livestock are such factors that could lead to pasture and soil degradation, desertification, more frequent and more fatal disasters and livestock diseases and a substantial loss of biodiversity. Less frequently but still mentioned were a poor governance with increasing administrative burdens, lacking transparency and law implementation and an inhibited development in the social, educational and health system.

4.2. Key transformational factors

This stakeholder perspective is a combination of the different perspectives of pasture user groups, representatives of pastoralists, international organisations, conservation practitioners, community (soum) and province (aimag) governors, representatives of national government agencies and further interest groups. In contrast, we sharpened the disciplinary perspectives of ecology, conservation science, cultural geography, economics, political science and other disciplines by engaging the research team. A first result of this synopsis is a list of 28 key factors, which we divided into six thematic fields (). Four of these fields, ‘policies and governance’, ‘social’, ‘environmental and ‘economic’, with 4–9 assignments each, contain a whole range of factors, while the other two categories only contain one additional factor each. These additional factors are climate change (field ‘climate’) and water availability, which plays an important role for wildlife, nomadic pastoralists and their livestock and, as it is determined by climatic factors as well as the construction and maintenance of wells and access to them, is categorised as a ‘cross-cutting’ factor.

Table 2. Key factors of future developments and their thematic fields.

The relative influences that these factors exert on each other can be seen in , which shows the results of applying the impact matrix. Factors of the thematic fields ‘policies and governance’ and ‘climatic’ form a cluster in the upper left corner of the matrix that indicates an active role for these ‘drivers’, which strongly influence other system factors, but are hardly influenced by them. It is worth noting that among these drivers are also those factors that both stakeholders and scientists identified as most decisive in shaping the system’s development. In exactly the opposite relationship to the other factors are the so-called ‘indicators’ (lower right corner), in which primarily the environmental factors appear. The remaining factors – that is, above all the ‘economic’ and ‘social’ ones – cluster in the centre of the matrix, which leads to an unclear classification, but factors belonging to these fields, such as ‘rural to urban migration/urbanisation’, ‘sedentarisation’ and ‘competition between resource users’, tend towards the upper right corner of the matrix. In this position are probably the most critical factors, ‘levers’ that are strongly interlinked with other key factors in the system as they both exert and experience strong influence. All three factors mentioned have the highest passive sums of the analysis with values > 35. Migration stands out further because, along with ‘decentralisation (of public services)’ and ‘comprehensive, coherent and transparent legislation and governance’, it is also one of the three factors with the highest active sums (> 35).

4.3. Scenario storylines

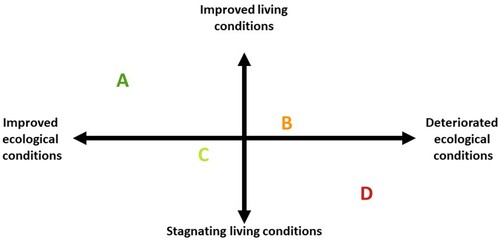

As described above, the best and worst-case scenarios span the range of possibilities for future scenarios, while an exact development along the path of one of these two scenarios is not very likely. We initially attempted to approach this possibility space by formulating a realistic scenario together with the project partners, based on a forecasting of observable trends to conflate them in a coherent storyline. However, in the course of the process, it turned out that it was best to split this third scenario into two, as one storyline concentrated more on people’s living conditions while the other concentrated on ecological conditions. This brought to light some developments that made it very difficult to unite the two directions: Certain (at least short- to medium-term) improvements in human living conditions can increase pressure on the ecosystem and, conversely, nature conservation measures can limit (particularly) opportunities for economic development. Despite these existing trade-offs, this does not mean that there is a fundamental contradiction between social and ecological developments. In fact, as shown above, the two are closely linked and not only do ecological processes form a basis for social development, but human activity – especially nomadic pastoralism – also forms an important element in the ecosystem. Consequently, we used the conceptual juxtaposition of nature and society in the SES (cf. ) to define two scenario axes, which allow us to map the final scenario storylines (). Even though these axes represent a clear simplification of the scenarios, they nevertheless reflect the two core themes that are not least the basic motivation of the entire research project. The horizontal axis spans from left to right between improved to deteriorated ecological conditions, while the vertical axis ranges from stagnating (bottom) to improved living conditions (top). Within this cross, the four scenarios are located as follows. The best case (A) and worst case (D) scenarios are close to the extremes, where favourable (upper left corner) and unfavourable (lower right corner) meet. Scenario B, entitled as ‘Progress in a degrading environment’, is located in the upper right quadrant with improved living conditions and deteriorated ecological conditions and scenario C, entitled as ‘Stagnation in a regenerating environment’, is located in the lower left quadrant with stagnating living conditions and improved ecological conditions. However, both scenarios C and B do not simply combine the states of the best and worst case scenarios according to their positions. Instead, the aforementioned interdependence of human living conditions and ecological conditions leads to the scenarios converging to the two axes, because the unfavourable development of one dimension hampers the favourable development of the other.

Figure 4. Structure of the scenario axes with the horizontal axis ‘ecological conditions’ and the vertical axis ‘living conditions’ and the position of scenarios A–D.

In the following, we use the six thematic fields of the key factors to describe the four scenarios in their alternative storylines for the developments of the eastern Mongolian steppe over the next 30 years. also provides a summary of the scenarios by key points.

Table 3. Summary of the four scenario storylines for the development of the SES of the eastern Mongolian steppe until 2050.

4.3.1. ‘Best case’

Climate: In the best-case scenario the impacts of climate change are relatively moderate, although seasonally late rainfall (and thus less useful for plant growth) and an increased spatial and temporal variability may occur. In addition, the frequency and intensity of extreme events (droughts and dzuds) increases, but more importantly, society will develop adaptation and coping strategies.

Water availability: Because of a good management of water sources the accessibility of water sources improves for the benefit of humans, livestock and wildlife.

Economic: On the economic side, there are new income opportunities due to a decentralisation of public services, the establishment of strong value chains for (high quality) livestock products and new agricultural products. At the same time, pastoralists are supported through government assistance to access national, regional and global markets.

Environmental: The smart rangeland management promotes an increase of forage quality, quantity, and soil organic carbon. Since fragmentation of the landscape appears only to a very small extend and conservation measures are effective, the gazelle population stabilises and partly even grows.

Policies and Government: A coherent and transparent legislation among departments and political-administrative levels is created, which has a whole range of positive effects, like a comprehensive education reform that reaches across all educational sectors and provinces. Fostering rural development and decentralisation of public services and infrastructure leads to a moderate expansion of roads and railways that ensures connectivity but minimises ecosystem fragmentation. Politics succeed in effectively regulating extractive industries and returning profits from this sector to the population. Meanwhile, nomadic pastoralists form lobby groups to support an improved political representation and enable effective policies to regulate herding activities (e.g. law on pasture, taxes, and pasture rotation). An accessible and user-friendly information system on the status of natural resources and platforms to negotiate between different resource users are operated and actively used. The conservation policy achieves land-use policies and species habitat protection that proves to be effective outside of protected areas.

Social: At the social level, there is a certain balance between urbanisation and migration to the eastern steppe. The pastoralists seasonal mobility remains important and at a relatively constant level, while a new form of nomadism of the twenty-first century is evolved that helps to maintain herding culture. At the same time, life in the steppe becomes more comfortable due to advances in communication access, cooking, heating and storage facilities. Social networks increasingly establish via social media and are drivers to spread knowledge about health, conservation and sustainability. In this nomadism of the twenty-first century, local ecological knowledge is reproduced and further developed. Transparent and balanced governmental regulations targeted at the prevention of poverty and inequality are complied with by the people. Overall, absentee herding is mainly an additional business for a small number of herders.

4.3.2. ‘Progress in a degrading environment’

Climate: The impacts of a (compared to the best-case scenario more) severe climate change limit the effectiveness of adaptation and coping strategies. Less reliable and often late rainfalls together with more frequent and intense extreme events result in a high loss of livestock.

Water availability: Modern wells are improved and newly built to ensure sufficient water for humans and livestock while natural water sources slowly dry up to the detriment of wildlife.

Economic: Former nomadic pastoralists find new income opportunities in new industries (e.g. mining and agriculture). These intensive industries and large-scale hay-making show severe impacts on the landscape, which increases the mobility costs for nomadic pastoralists. There is improved access to the national market in the countryside, while the market for high-quality livestock products slowly evolves. All of this results in a fierce competition between resource users.

Environmental: A wide spread decrease of soil and forage quality and quantity can be observed. Only in a few regions, the abandonment of grazing activities leads to some increase of vegetation cover and a change in species composition, In general, competition for grassland resources is in favour of livestock and to the disadvantage of wildlife. Both developments, strong fragmentation and the increasing competition for forage lead to an impoverishment of the gazelle population.

Policies and Governance: The government aims for a transparent legislation, but policies still lack coherency among departments and political-administrative levels. Educational reforms are initiated on all levels, but still concentrate on larger cities and especially Ulaanbaatar, due to a moderate degree of decentralisation of public services. Still, the access to education in soum and aimag centres is improved and the strong expansion of roads and railways ensures connectivity, while causing significant ecosystem fragmentation. The regulation of extractive industries is only partly effective, but an increasing percentage of the profits remain in Mongolia. In order to be involved in political decisions, lobby groups for nomadic herders slowly develop. Taxes and policies that the government puts in place to limit livestock numbers lack enforcement and some first attempts to support the value chain of high-quality livestock products emerge. An information system on the status of natural resources is established, but can only be used by governmental agencies. Conservation measures are still restricted to protected areas and developed plans for species and habitat management lack enforcement.

Social: The continuing urbanisation trends co-occur with migration of pastoralists from central and western regions to the eastern steppe. The general tendency of sedentarisation accelerates, while remaining nomadic pastoralists follow a variety of different livelihood strategies. Depending on the possibility of investments, they can realise a strategy that favours quality of livestock over quantity and for many livestock owners absentee herding plays an important role. In general, life in the steppe becomes more comfortable due to advances in communication access, cooking, heating and storage facilities. At family level, the new job opportunities in agglomerations and big industries ensure sufficient income but bring changes to society and culture, including a significant loss of traditional ecological knowledge. Overall, compliance is still relatively low, with slow progress in enforcement.

4.3.3. ‘Stagnation in a regenerating environment’

Climate: In this scenario, moderate impacts of climate change meet a society that is still lacking adequate adaptation and coping strategies.

Water availability: Wells are badly maintained and partly privatised, so that in many areas poorer households depend to a greater degree on natural water sources.

Economic: Nomadic pastoralists face higher costs and less income due to a decayed infrastructure, weakening social bonds and falling prizes for livestock products. In the countryside, intensive industries establish to a moderate degree, still the competition between resource users and degradation increase the mobility costs for pastoralists.

Environmental: The decrease of soil, forage quality and quantity is moderate and mostly appears locally, while in some places vegetation cover even increases. Overall, there is less pressure on grassland resources and a moderate fragmentation of the landscape result in relatively stable gazelle populations in major parts of the eastern steppe.

Policies and Governance: The legislation still lacks coherency among departments and political-administrative levels. Educational opportunities (especially for higher education) and other public services only exist in major cities and above all in Ulaanbaatar. The expansion of roads and railways remains moderate, but a lot of traffic on major streets and fencing of railways still cause fragmentation. The regulation of extractive industries remain ineffective and profits still mainly go abroad. Nomadic pastoralists do not have a political voice on the national level and regulations are either not in place or not enforced. In consequence, competition between resource users usually leads to the disadvantage of poorer pastoralists. Similarly, species and habitat management plans are established but lack enforcement, so effective conservation measures are still restricted to protected areas.

Social: Social developments reflect growing inequality: Urbanisation takes place along a social divide, with poorer households left in the steppe. Overall, the number of (nomadic) pastoralists decreases, but those remaining have quite constant seasonal mobility patterns. Life in the steppe remains difficult and is made even more difficult by the loss of social ties (including the break-up of Khot Ails due to increased migration). Industry offers mostly low-paid jobs to a small number of people, and the lower class is also growing in the cities. The pastoralists that stay in the steppe can preserve a lot of the traditional local ecological knowledge and cultural values. Official honours and awards that encourage large livestock numbers stay in place. Absentee herding plays an important role, especially as an additional business for herders. Compliance to regulations is relatively low due to a lack of enforcement.

4.3.4. ‘Worst case’

Climate: In the worst-case scenario severe consequences of climate change are exacerbated by non-existing adaptation and coping strategies. Less reliable and often late rainfalls together with more frequent and intense extreme events result in very high livestock losses, that threaten people’s existence.

Water availability: Wells are badly maintained or privatised, while a growing number of natural water sources slowly dry up. Only wealthier pastoralists have a save water supply, while poorer households and their livestock compete with wildlife over the remaining natural water sources. Locally and temporarily, there are shortages of drinking water.

Economic: A decaying infrastructure, degradation, weakening social bonds and falling prizes for livestock products lead to higher costs with simultaneously declining income. Large companies heavily exploit mineral resources and large scale hay making spreads within the Eastern steppe. The profits of both mainly go abroad. Advanced agricultural technologies allow (short-term) profits in marginal environments but exhaust the ecosystem.

Environmental: The ecological consequences are a reduced quantity and quality of forage, a decreasing share of palatable plant species and a lower crude protein content of forage. The decline in vegetation cover leads to increasing soil erosion and, through this positive feedback, locally to desertification. An intense fragmentation of the landscape and the increasing competition for forage significantly impoverishes the gazelle population.

Policies and Governance: At the political level, one dimensional and non-transparent policies prevail. Many aspirations, like educational reforms and decentralisation, stagnate. Large companies (including extractive industries) drive the expansion of roads and railways and a lack of regulation means that profits mainly go abroad. Industrialised meat production with high livestock numbers can continue to grow, while nomadic pastoralists still have no political voice. As a result, laws limiting livestock are not enacted and competition between resource users is to the detriment of poor pastoralists. Similarly, species and habitat management plans are not established and conservation measures are still restricted to few protected areas.

Social: In social terms, a strong urbanisation is evident, although poor pastoralists stay in the eastern steppe, where further pastoralists from central and western Mongolia arrive. Their seasonal mobility decreases in terms of distances and frequency. For these people the life in the steppe remains hard and weakening social bonds (i.a. Khot Ail) and increasing extreme events make it even harder. Companies offer mostly low-paid jobs to a small number of people, and the lower class in the cities is growing. While the traditional image of nomadic pastoralism remains culturally significant, traditional ecological knowledge is in danger of being forgotten. At the same time, pastoralists are forced to increase their livestock and work as absentee herders to secure their livelihoods. All of this leads to a strong resistance against policies and their implementation.

5. Discussion: A roadmap for the future?

In order to critically assess the results, it is important to say that not all stakeholders’ perspectives were equally brought to the stakeholder workshops. First of all, herders from eastern provinces could not participate in workshops at state level due to time-consuming travels of several days. Secondly as mentioned above, the topic of livestock diseases, which was mainly brought up by the herder representatives, received less attention in the further process due to the low reception of the other participants. Although this may be justified in the overall balance with the other topics in this particular case, it nevertheless illustrates that despite the moderators’ efforts to balance the discussions, some voices were more dominant than others. Reasons for this imbalance include differences in experience with workshop formats, social hierarchy and habitus. Unfortunately, our efforts to redress this imbalance were partially thwarted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The planned follow-up workshops at provincial level, which would have allowed for a stronger involvement of nomadic pastoralists from all eastern aimags in the process, could not take place. Thus, we had to rely more on the many years of experience of our Mongolian project partners in field work with herders.

In the following, we discuss the possible options for application that result from our findings. While the results first and foremost describe a possibility space, they also provide a basis for the identification of necessary transformation steps. Although we cannot pre-empt the societal negotiation processes, we sketch out examples of the role that the identified key transformation factors can play in transformation efforts.

5.1. Exploring the possibility space

With reference to work done within the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the overall scenario development process, if seen as a tool for policy making, can be understood as an intermediate step between exploratory and target-seeking scenarios (IPBES Citation2016). In a sense of agenda setting (IPBES Citation2016), the ‘best case’ (A) and ‘worst case’ (D) scenarios span the possibility space and the two scenarios ‘Progress in a degrading environment’ (B) and ‘Stagnation in a regenerating environment’ (C) partially fill this wide possibility. In doing so, they help to make future options more tangible and by comparing them, it is possible to identify critical points, from where developments diverge from a possibly sustainable path, which, incidentally, does not necessarily have to be the ‘best case’ scenario.

By using the two scenario axes ‘living conditions’ and ‘ecological conditions’, we defined a certain variability among the scenarios that provokes certain trade-offs between social and ecological progress, but our analysis also revealed the strong interdependencies between both axes. With regard to the horizontal axis of ‘ecological conditions’, the expected impact of climate change played an important role. Including climate change and society’s ability to cope and adapt allows us to link our scenarios to the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) that focus on the socio-economic challenges for climate change mitigation and for adaptation (O’Neill et al. Citation2017). These two factors span the axes for the SSP scenarios. SSP 1, ‘Sustainability – Taking the Green Road’, comprise relatively low challenges on both axes and can be compared to our ‘best case’ scenario A. The SSP scenario with intermediate challenges, SSP 2 (‘Middle of the Road’) resembles scenario B and SSP 3 (‘Inequality – A Road Divided’) with relatively bigger challenges for adaptation but fewer challenges for mitigation resembles scenario C. Finally SSP3, ‘Regional Rivalry – A Rocky Road’, as the scenario with the biggest challenges to both, mitigation and adaptation, compares to the ‘worst case’ scenario D. Obviously, our scenarios and the SSPs are not interchangeable, mainly because of the different geographic foci. Describing possible future conditions for the entire earth on basis of large world regions, the SSPs are not intended to show subnational developments (O’Neill et al. Citation2017), unlike our scenarios that concentrate on eastern Mongolia.

5.2. Designing transformation processes

At this point, our results do not yet provide a societal target definition, but a framework that can be used in the further process. This would mean to use the scenarios to define targets by identifying priorities and subordinate goals (IPBES Citation2016). Another cornerstone to identify such a target is the ‘Vision 2050’ of the Mongolian government, which describes individual measures and their sequence in great detail (Government of Mongolia Citation2021). Similar to our scenario A, this vision basically describes a best case, from whose ideal target image divergences must necessarily be accepted. Depending on the direction of a path’s divergence from the best case, ecological and/or social progress may fall by the wayside. Scenario B and C both imply some of these divergences, but at the same time they also contain favourable aspects that are worth thriving for. Since both scenarios were assessed as essentially realistic, the factors that distinguish them are of particular interest in finding strategies to stay on a sustainable path. Most apparent, climate change is one of these factors whose actual impacts are still uncertain. In any case, coping and adaptation measures will be required at the individual and governmental level, because climate change is a factor that for the SES in question can be considered as an external factor, which means that it cannot be directly influenced. Particularly in the case of national adaptation strategies, the question of setting priorities arises – even in the case of relatively moderate climate change impacts. As our scenario storylines show, at the latest in the case of severe impacts it may be difficult to preserve the living conditions of the people and ecological functions at the same time. The distribution of financial, planning and management resources to implement necessary measures is, moreover, not only a question of political will, but also of the availability of qualified personnel and expertise, and thus a question of whether certain measures in the educational sector were already taken decades ago. The ‘worst-case’ scenario also illustrates that, for instance, a reduction in grazing pressure due to increased rural-urban migration does not necessarily have positive effects on the ecosystem. Not only does livestock provide ecosystem functions through grazing and seed dispersal, but the disappearance of herders, in the absence of political regulation, opens the way for large-scale industries such as mining, intensive agriculture and haymaking. The ecological consequences can be devastating, not only because of the construction of fences.

5.3. Monitoring key transformation factors along the way

This makes clear that system factors and measures to influence them have to be considered and monitored in their interdependencies. The categorisation of the key transformation factors into driver, lever and indicator can help in this regard. If, for instance, employment and social policy is neglected in urban areas, the rural urban migration might (partly) reverse when people see the return to pastoralism as a fallback option. The importance of coherence between policy fields, is also evident in those points where developments in one field facilitate or impede the enforcement of measures in another field. For example, restrictive measures in nature conservation and pasture management have significantly stronger consequences for pastoralists when population and animal densities are relatively high, while bans on the use of protected areas affect pastoralists significantly less when sufficient alternative options exist.

Furthermore, it is important to point out that a scenario like ‘Progress in a degrading environment’ does not automatically turn into the ‘best case’ scenario, if climate change impacts do not turn out to be as severe as assumed. Many more factors need to be considered to actually steer scenario B towards the ‘best case’ scenario. Two important factors are policies to support high quality livestock products and the regulation of extractive industries. Falling prices for livestock products and rising costs can result in pastoralists relying on ever higher numbers of livestock to make a living – a development that can also be observed in many other countries. The consequences an unregulated extractive industry can have on the environment, regardless of climate change, have already been discussed above and can also be seen in many other countries. If we look at the other key factors identified earlier, the complexity of the situation under consideration becomes even clearer. While access to and quality of educational opportunities have already been mentioned in terms of their importance to facilitate the implementation of policies, they also show their central role here, corresponding to the central position in . Education is not only of high relevance for processes of urbanisation and sedentarisation, both of which having strong influence on population and livestock densities, but it is driven itself also by further key factors. Decentralisation of public services, for instance, determines whether young people need to go to Ulaanbaatar for higher education or if they can graduate also in other places. Although national legislation is decisive for many of these factors, it remains of central importance to observe the developments in a locally differentiated manner. The reason for this is that complex systems are not only highly volatile in time, but also in space, and local particularities prohibit relying on supposed ‘one-size-fits-all solutions’.

While processes like urbanisation and migration can often be observed relatively easily and continuously over time, the impact matrix () reminds us of other indicators, for which a continuous monitoring would be helpful to keep track of the system development. These factors are forage quality and quantity, competition between livestock and wildlife and mobility and abundance of wildlife.

6. Outlook: towards a nomadic pastoralism for the twenty-first century

Popular discourse in the media foretells the end of nomadism, but overlooks Mongolia’s long history of shifting livelihood strategies (Honeychurch Citation2010) and the persistence of mobile pastoralism in marginal environments around the globe, defying predicted extinction. (Reid, Fernández-Giménez, and Galvin Citation2014). (Chen et al. Citation2018, 13)

In terms of fundamental and rapid change, the past two years have been extremely remarkable. The COVID-19 pandemic has often been described as a catalyst for change, especially in relation to or through the digitalisation of important areas of society, such as education (Heng Citation2021; Komljenovic Citation2020), work life (Davies Citation2021) and medicine (Thulesius Citation2020). Although, the coverage with mobile internet access is still lacking in the steppe, it is safe to say that digitalisation and remote access to public services will play an important role in any kind of Mongolian nomadic pastoralism in the twenty-first century. While remote schooling and ‘eHealth’ are likely to find wider application, it remains to be seen whether traditional gers (Mongolian yurts) will also become home offices in the future. Moreover, digitalisation can also enable social and cultural participation by maintaining contacts with friends and relatives and making (also international) cultural events accessible from the steppes. However, digitalisation is far from being a panacea for all necessary or desirable developments, and it does not make the long winter nights on the steppe any warmer either. Also, education, health care and cultural events are not necessarily free, even if they are accessed remotely. Therefore, other questions, such as the following, are probably equally important: How can a sales market for high-quality animal products be developed? How can processed and thus higher-priced products be created and marketed in cooperative structures? Or, how can specialisation in individual types of livestock, products or production steps be organised collectively? Can entirely new forms of work and economy develop, such as community supported agriculture or job sharing, which also allow for life plans in which people only temporarily follow a ‘classic’ nomadic lifestyle?

With the outlined scenarios, we were able to shed some light on the possibility space of the next 30 years. Probably, a basic agreement could be reached in society that a desirable and at the same time realisable future is somewhere in the space where scenarios B and C converge on scenario A. The discussions in our stakeholder workshops suggest that there is broad agreement on the basic knowledge and also that many values, such as the basic appreciation of nomadic pastoralism, are widely shared (Jahn, Bergmann, and Keil Citation2012). Thus, further joint visioning processes can help to refine the orientation knowledge aggregated in the scenarios. Once a basic agreement on the goals has been reached, transformation knowledge is needed to implement transformative processes in practice (Jahn, Bergmann, and Keil Citation2012). First ideas of such transformation knowledge can be seen in our analysis of the key transformation factors. Nevertheless, in individual decisions it will always be necessary to trade-off between different partial objectives, but at the same time, many problems also result in the possibility of finding synergies. If these synergies can be put first without neglecting the trade-offs, there is a good chance that concrete and productive opportunities will emerge that can be harnessed to shape a sustainable future of the eastern Mongolian steppe with a vivid nomadic pastoralism for the twenty-first century.

We have described the particularities of the Mongolian steppe, with its relatively low degree of degradation and fragmentation, combined with the still high importance of traditional ways of life. If a sustainable transformation to a socially, culturally and ecologically viable path can be found under these, in global comparison, relatively favourable conditions, this example can also spread to other grasslands in the world. Given the impact of global drivers like globalisation and climate change, grasslands in Africa, South and Central America often face comparable challenges and although traditional ways of life have often been pushed back, they have not been completely forgotten (Coppock et al. Citation2017). Of course, this cannot mean to find a solution that is directly transferable, but rather that comparable participatory and transdisciplinary processes should be initiated. Based on the experiences of this work, the power relations between stakeholders and the hampered access to participatory formats of rural population should be considered in particular. One answer to this can be to work with different (decentralised) formats and in different group constellations. The development and refinement of scenarios can be a productive way to bring together the necessary breadth of perspectives. Supported by a research team with diverse disciplinary and cultural backgrounds, such a transdisciplinary approach has great potential.

Moreover, we see particular potential in the strong involvement of indigenous groups, who in many places have demonstrated their ability to make a sustainable living in and with nature. At a time when many scientific (see Ferreira et al. Citation2020) and political actors, such as the EU (see Maes and Jacobs Citation2017), are calling for a return to nature-based solutions for necessary societal transformations, we cannot do without the experience of these experts in nature-based solutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all workshop participants from 2017 and 2019 for their active participation in the workshops and for providing valuable input. The authors further thank Usukhjargal Dorj for moderating the workshop session on scenario development in 2019 and all colleagues in the MORE STEP consortium for their much appreciated contributions to the scenario development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lukas Drees

Lukas Drees is a research scientist and PhD student in the research unit Water Resources and Land Use at ISOE – Institute for Social-Ecological Research in Frankfurt/Main, Germany. He has been working in different transdisciplinary teams and projects on water availability, integrated water resources management and the climate-migration nexus. His research focuses on integrated social-ecological modelling of human decision-making and associated land-use changes. In his work, he concentrates on methods to integrate social and natural scientific data across different spatial scales and interactive methods for scenario development.

Stefan Liehr

Stefan Liehr is head of the research unit Water Resources and Land Use at ISOE – Institute for Social-Ecological Research in Frankfurt/Main, Germany. He has long-term experience in working in international cooperation of inter- and transdisciplinary teams on sustainable management of water and land resources. Working on integrated modelling, scenario development, water demand analysis and impact assessments, his research focuses on understanding interactions and feedback mechanisms between societal actors and ecosystems in the light of the concept of social-ecological systems.

Batjav Batbuyan

Batjav Batbuyan is director of the Centre for Nomadic Pastoralism Studies, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. He has been involved in several interdisciplinary studies that looked on changes in pastoral management systems and analysed socioeconomic patterns of development in Mongolia. With more than 30 years of expertise in working on nomadic pastoralism, his research focuses on issues related to sustainable rural development approaches, which include infrastructure development in rural Mongolia, poverty, pastoral land tenure, and community-based natural resources management.

Oskar Marg

Oskar Marg is a research scientist in the research unit Transdisciplinary Methods and Concepts at ISOE – Institute for Social-Ecological Research in Frankfurt/Main, Germany, since 2016. He has a background in social sciences with a focus on environmental and knowledge sociology. Oskar Marg has many years of experience working in and on transdisciplinary research. His work focuses on the integration of diverse knowledge, effects of transdisciplinary research on science and society, and accompanying research of transdisciplinary projects.

Marion Mehring

Marion Mehring is head of the research unit Biodiversity and People at ISOE - Institute for Social-Ecological Research in Frankfurt/Main, Germany. With a regional focus on Asia, she has long-term experience in working in inter-and transdisciplinary teams, facilitating stakeholder dialogues and (quantitative and qualitative) social-empirical research. Her research focuses on social-ecological biodiversity research, the sustainable use of ecosystem services, perception and valuation of biodiversity and ecosystem services and disservices, as well as concepts of social-ecological systems.

References

- Ahlborn, Julian, Henrik von Wehrden, Birgit Lang, Christine Römermann, Munkhzul Oyunbileg, Batlai Oyuntsetseg, and Karsten Wesche. 2020. “Climate – Grazing Interactions in Mongolian Rangelands: Effects of Grazing Change Along a Large-Scale Environmental Gradient.” Journal of Arid Environments 173 (October 2019): Article 104043. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2019.104043.

- Batsaikhan, Nyamsuren, Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar, Bazaar Chimed, Oidov Enkhtuya, Davaa Galbrakh, Oyunsaikhan Ganbaatar, Badamjav Lkhagvasuren, et al. 2014. “Conserving the World’s Finest Grassland Amidst Ambitious National Development.” Conservation Biology 28 (6): 1736–1739. doi:10.1111/cobi.12297.

- Becker, Egon. 2012. “Social-Ecological Systems as Epistemic Objects.” In Human-Nature Interactions in the Anthropocene: Potentials of Social-Ecological Systems Analysis, edited by Marion Glaser, Gesche Krause, Beate M. W. Ratter, and Martin Welp, 37–59. London: Routledge.

- Börjeson, Lena, Mattias Höjer, Karl-Henrik Dreborg, Tomas Ekvall, and Göran Finnveden. 2006. “Scenario Types and Techniques: Towards a User’s Guide.” Futures 38 (7): 723–739. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2005.12.002.

- Chen, Jiquan, Ranjeet John, Ge Sun, Peilei Fan, Geoffrey M. Henebry, María E. Fernández-Giménez, Yaoqi Zhang, et al. 2018. “Prospects for the Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems (SES) on the Mongolian Plateau: Five Critical Issues.” Environmental Research Letters 13: Article 123004. IOP Publishing. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aaf27b.

- Coppock, D Layne, Maria Fernández-Giménez, Pierre Hiernaux, Elisabeth Huber-Sannwald, Catherine Schloeder, Corinne Valdivia, José Tulio Arredondo, Michael Jacobs, Cecilia Turin, and Matthew Turner. 2017. “Rangeland Systems in Developing Nations: Conceptual Advances and Societal Implications’.” In Rangeland Systems, edited by David D. Briske, 569–642. Cham: Springer Series on Environmental Management.

- Dashpurev, Batnyambuu, Jörg Bendix, and Lukas W. Lehnert. 2020. “Monitoring Oil Exploitation Infrastructure and Dirt Roads with Object-Based Image Analysis and Random Forest in the Eastern Mongolian Steppe.” Remote Sensing 12 (1): 144. doi:10.3390/rs12010144.

- Davies, Amanda. 2021. “COVID-19 and ICT-Supported Remote Working: Opportunities for Rural Economies.” World 2 (1): 139–152. doi:10.3390/world2010010.

- Fan, Peilei, Jiquan Chen, and Ranjeet John. 2016. “Urbanization and Environmental Change During the Economic Transition on the Mongolian Plateau: Hohhot and Ulaanbaatar.” Environmental Research 144 (509): 96–112. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2015.09.020.

- Fernández-Giménez, María E., Arren Allegretti, Jay Angerer, Batkhishig Baival, Batbuyan Batjav, Steven Fassnacht, Chantsallkham Jamsranjav, et al. 2019. “Sustaining Interdisciplinary Collaboration Across Continents and Cultures: Lessons from the Mongolian Rangelands and Resilience Project.” In Collaboration Across Boundaries for Social-Ecological Systems Science, 185–225. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-13827-1_6.

- Fernández-Giménez, María E., Ginger R.H. Allington, Jay Angerer, Robin S. Reid, Chantsallkham Jamsranjav, Tungalag Ulambayar, Kelly Hondula, et al. 2018. “Using an Integrated Social-Ecological Analysis to Detect Effects of Household Herding Practices on Indicators of Rangeland Resilience in Mongolia.” Environmental Research Letters 13 (7): Article 075010. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aacf6f.

- Fernández-Giménez, María E., Batkhishig Baival, Steven R. Fassnacht, and David Wilson. 2015. “Building Resilience of Mongolian Rangelands.” In Proceedings of Building Resilience of Mongolian Rangelands: A Trans-Disciplinary Research Conference. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

- Fernández-Giménez, María E., Batbuyan Batjav, and Batkhishig Baival. 2012. Lessons from the Dzud : Adaptation and Resilience in Mongolian Pastoral Social-Ecological Systems. Colorado State University & The Center for Nomadic Pastoralism Studies.

- Fernández-Giménez, María E., Niah H. Venable, Jay Angerer, Steven R. Fassnacht, Robin S. Reid, and J. Khishigbayar. 2017. “Exploring Linked Ecological and Cultural Tipping Points in Mongolia.” Anthropocene 17: 46–69. March. Elsevier B.V. doi:10.1016/j.ancene.2017.01.003.

- Ferreira, Vera, Ana Barreira, Luís Loures, Dulce Antunes, and Thomas Panagopoulos. 2020. “Stakeholders’ Engagement on Nature-Based Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review’.” Sustainability 12 (2): 640. doi:10.3390/su12020640.

- Government of Mongolia. 2021. Vision-2050. Introduction to Mongolia’s long-term development policy document. Ulaanbaatar. https://vision2050.gov.mn/file/AlsiinkharaaEnglish1020.pdf.

- Heng, Kimkong. 2021. COVID-19: A Catalyst for the Digital Transformation of Cambodian Education. 87. Vol. 2021. Perspective. http://hdl.handle.net/11540/13876.

- Hichert, Tanja, Reinette Biggs, Alta de Vos, and Garry Peterson. 2021. “Scenario Development.” In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods for Social-Ecological Systems, edited by Reinette Biggs, Alta de Vos, Rika Preiser, Hayley Clements, Kristine Maciejewski, and Maja Schlüter, 163–175. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003021339-11.

- Honeychurch, William. 2010. “Pastoral Nomadic Voices: A Mongolian Archaeology for the Future.” World Archaeology 42 (3): 405–417. doi:10.1080/00438243.2010.497389.

- Honeychurch, William. 2014. “Alternative Complexities: The Archaeology of Pastoral Nomadic States.” Journal of Archaeological Research 22 (4): 277–326. doi:10.1007/s10814-014-9073-9.

- Honeychurch, William. 2015. Inner Asia and the Spatial Politics of Empire. Inner Asia and the Spatial Politics of Empire. New York: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-1815-7.

- Huang, Shu-Li, Chia-Tsung Yeh, William W. Budd, and Li-Ling Chen. 2009. “A Sensitivity Model (SM) Approach to Analyze Urban Development in Taiwan Based on Sustainability Indicators.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 29 (2): 116–125. Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2008.03.003.

- Hummel, Diana, Thomas Jahn, and Engelbert Schramm. 2011. Social-Ecological Analysis of Climate Induced Changes in Biodiversity – Outline of a Research Concept. Knowledge Flow Paper No. 11. Frankfurt am Main: LOEWE Biodiversität und Klima Forschungszentrum BiKF.

- IPBES. 2016. The Methodological Assessment Report on Scenarios and Models of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Summary for Policymakers, edited by Herausgegeben von S. Ferrier, K. N. Ninan, P. Leadley, R. Alkemade, L. A. Acosta, H. R. Akçakaya, and L. Brotons, u. a. Bonn: Elsevier B.V. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3235428.

- Jahn, Thomas, Matthias Bergmann, and Florian Keil. 2012. “Transdisciplinarity: Between Mainstreaming and Marginalization.” Ecological Economics 79 (July): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.04.017.

- Jahn, Thomas, Diana Hummel, Lukas Drees, Stefan Liehr, Alexandra Lux, Marion Mehring, Immanuel Stieß, Carolin Völker, Martina Winker, and Martin Zimmermann. 2020. “Sozial-Ökologische Gestaltung Im Anthropozän.” GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 29 (2): 93–97. doi:10.14512/gaia.29.2.6.

- Jamiyansharav, Khishigbayar, María E. Fernández-Giménez, Jay P. Angerer, Baasandorj Yadamsuren, and Zumberelmaa Dash. 2018. “Plant Community Change in Three Mongolian Steppe Ecosystems 1994–2013: Applications to State-and-Transition Models.” Ecosphere 9: 3. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2145.

- Jamsranjav, Chantsallkham, María E. Fernández-Giménez, Robin S. Reid, and B. Adya. 2019. “Opportunities to Integrate Herders’ Indicators Into Formal Rangeland Monitoring: An Example from Mongolia.” Ecological Applications 29 (5): 1–20. doi:10.1002/eap.1899.

- John, Ranjeet, Jiquan Chen, Vincenzo Giannico, Hogeun Park, Jingfeng Xiao, Gabriela Shirkey, Zutao Ouyang, Changliang Shao, Raffaele Lafortezza, and Jiaguo Qi. 2018. “Grassland Canopy Cover and Aboveground Biomass in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia: Spatiotemporal Estimates and Controlling Factors.” Remote Sensing of Environment 213 (July 2017): 34–48. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2018.05.002.

- John, Ranjeet, Jiquan Chen, Youngwook Kim, Zu tao Ou-yang, Jingfeng Xiao, Hoguen Park, Changliang Shao, et al. 2016. “Differentiating Anthropogenic Modification and Precipitation-Driven Change on Vegetation Productivity on the Mongolian Plateau.” Landscape Ecology 31 (3): 547–566. Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/s10980-015-0261-x.

- Kassam, Karim-Aly S., Chuan Liao, and Shikui Dong. 2016. “Sociocultural and Ecological Systems of Pastoralism in Inner Asia: Cases from Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia in China and the Pamirs of Badakhshan, Afghanistan.” In Building Resilience of Human-Natural Systems of Pastoralism in the Developing World, edited by Shikui Dong, Karim-Aly S. Kassam, Jean François Tourrand, and Randall B. Boone, 137–175. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30732-9_4.

- Khishigbayar, J., María E. Fernández-Giménez, Jay P. Angerer, R. S. Reid, J. Chantsallkham, Ya Baasandorj, and D. Zumberelmaa. 2015. “Mongolian Rangelands at a Tipping Point? Biomass and Cover are Stable but Composition Shifts and Richness Declines After 20 Years of Grazing and Increasing Temperatures.” Journal of Arid Environments 115 (April 2015): 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2015.01.007.

- Komljenovic, Janja. 2020. “The Future of Value in Digitalised Higher Education: Why Data Privacy Should Not Be Our Biggest Concern.” Higher Education (November): Article 0123456789 . Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00639-7.

- Konagaya, Yuki, and Ai Maekawa. 2013. “Characteristics and Transformation of the Pastoral System in Mongolia.” In The Mongolian Ecosystem Network, edited by Norio Yamamura, Noboru Fujita, and Ai Maekawa, 9–21. Tokyo: Springer Japan. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-54052-6_2.

- Kosow, Hannah, and Robert Gaßner. 2008. Methoden Der Zukunfts- Und Szenarioanalyse. WerkstattBericht. Vol. 103. Berlin: IZT. https://www.izt.de/fileadmin/downloads/pdf/IZT_WB103.pdf.

- Lam, David P. M., Elvira Hinz, Daniel J. Lang, Maria Tengö, Henrik von Wehrden, und Berta Martín-López. 2020. “Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Sustainability Transformations Research: A Literature Review.” Ecology and Society 25 (1), art3. doi:10.5751/ES-11305-250103.

- Lamchin, Munkhnasan, Taejin Park, Jong-Yeol Lee, and Woo-Kyun Lee. 2015. “Monitoring of Vegetation Dynamics in the Mongolia Using MODIS NDVIs and Their Relationship to Rainfall by Natural Zone.” Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing 43 (2): 325–337. doi:10.1007/s12524-014-0366-8.

- Liehr, Stefan, Julia Röhrig, Marion Mehring, and Thomas Kluge. 2017. “How the Social-Ecological Systems Concept Can Guide Transdisciplinary Research and Implementation: Addressing Water Challenges in Central Northern Namibia.” Sustainability 9 (7): 1109. doi:10.3390/su9071109.

- Maes, Joachim, and Sander Jacobs. 2017. “Nature-Based Solutions for Europe’s Sustainable Development’.” Conservation Letters 10 (1): 121–124. doi:10.1111/conl.12216.

- Matias, Denise Margaret S. 2021. “Indigenous Livelihood Portfolio as a Framework for an Ecological Post-COVID-19 Society.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 123 (May): 12–13 Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.04.018.

- Matias, Denise Margaret, Lukas Drees, Ulan Kasymov, Dejid Nandintsetseg, Batjav Batbuyan, Tserendeleg Dashpurev, Usukhjargal Dorj, et al. 2020. Mobility at Risk: Sustaining the Mongolian Steppe Ecosystem – Developing a Vision. Stakeholder Involvement and Identification of Drivers and Pathways towards Sustainable Development. ISOE-Materialien Soziale Ökologie. Vol. 62. Frankfurt am Main. http://www.isoe-publikationen.de/fileadmin/redaktion/ISOE-Reihen/msoe/msoe-62-isoe-2020.pdf.

- Mehring, Marion, Batjav Batbuyan, Sanjaa Bolortsetseg, Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar, Tserendeleg Dashpurev, Lukas Drees, Shiilegdamba Enkhtuvshin, Gonchigsumlaa Ganzorig, et al. 2018a. Keep on Moving - How to Facilitate Nomadic Pastoralism in Mongolia in the Light of Current Societal Transformation Processes. 7. ISOE Policy Brief. ISOE Policy Brief. Frankfurt am Main. http://www.isoe-publikationen.de/fileadmin/redaktion/ISOE-Reihen/pb/isoe-policy-brief-7-2018.pdf.

- Mehring, Marion, Batjav Batbuyan, Sanjaa Bolortsetseg, Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar, Tserendeleg Dashpurev, Lukas Drees, Shiilegdamba Enkhtuvshin, Gungaa Munkhbolor, et al. 2018b. Mobility at Risk: Sustaining the Mongolian Steppe Ecosystem – Societal Transformation Processes. Stakeholder Analysis and Identification of Drivers and Potential Solution Pathways. 52. ISOE-Materialien Soziale Ökologie. Vol. 52. Frankfurt am Main. http://www.isoe-publikationen.de/fileadmin/redaktion/ISOE-Reihen/msoe/msoe-52-isoe-2018.pdf.

- Mehring, Marion, Barbara Bernard, Diana Hummel, Stefan Liehr, and Alexandra Lux. 2017. “Halting Biodiversity Loss: How Social–Ecological Biodiversity Research Makes a Difference.” International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 13 (1): 172–180. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.1080/21513732.2017.1289246.

- Mijiddorj, Tserennadmid Nadia, Justine Shanti Alexander, Gustaf Samelius, Charudutt Mishra, and Bazartseren Boldgiv. 2020. “Traditional Livelihoods Under a Changing Climate: Herder Perceptions of Climate Change and Its Consequences in South Gobi, Mongolia.” Climatic Change 162 (3): 1065–1079.. Climatic Change. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02851-x.

- Mistry, Jayalaxshmi, und Andrea Berardi. 2016. “Bridging Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge.” Science 352 ( (6291): 1274–1275. doi:10.1126/science.aaf1160.

- Munkhzul, Oyunbileg, Khurelpurev Oyundelger, Naidan Narantuya, Indree Tuvshintogtokh, Batlai Oyuntsetseg, Karsten Wesche, and Yun Jäschke. 2021. “Grazing Effects on Mongolian Steppe Vegetation—A Systematic Review of Local Literature.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9 (October): 1–13. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.703220.