Abstract

In this paper, we trace how ‘social procurement’ (SP) translates from policy to practice. Launched as a driver of social innovation and sustainability, SP offers a novel way of strengthening the implementation of active labor market policies locally. Policy tools are not neutral instruments, however; they shape the substance of policy in decisive ways. That is, how tools are used determines what the policy ‘becomes’. Building on a qualitative case study, the analysis shows how local translations enabled new roles, approaches and purchasing practices, and how the practice of purchasing ‘social goods’ largely became a practice of providing competence to private enterprises. The implications of such a shift for local work on active labor market policies, as well as broader implications of attempts to use procurement to attain social sustainability, need to be further explored in future research.

Introduction

Social sustainability is largely promoted in the intersection of markets, organizations, and society. In this context, public procurement is increasingly emphasized by policy-makers as a lever for social reform and a driver of social innovation (Barraket Citation2020; European Union Citation2020; Nijboer, Senden, and Telgen Citation2017). Social procurement is often used as a collective name for this way of using procurement. However, social procurement is not a neutral instrument in the hands of policymakers but rather shapes, as all governance tools do, the substance of policy in a decisive way (van Berkel, Willibrord de Graaf, and Sirovátka Citation2012; Olsson and Öjehag-Pettersson Citation2020). What the social innovations and outcomes will be depend on how the tool is put into use. Studies of social procurement show dynamic processes of multiple actors collaborating, with new (intermediating) roles emerging (Barraket Citation2020; Troje and Gluch Citation2020) and a wide range of local practices being developed (e.g. Brammer and Walker Citation2011; Norbäck and Campos Citation2022). However, the local translation and transformation of social procurement policies into novel local practices and the consequences these entail, are still understudied.

In this paper, we trace how social procurement as a means of promoting employment opportunities for vulnerable groups translates from policy to practice. Public authorities across Europe are called upon to include employment criteria in their procurements as a novel way of implementing active labor market policies (ALMP) by making use of the public purchasing power (European Union Citation2021; Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014). In light of the localized and fragmented governance arrangements that have emerged in the wake of ALMP reforms (van Berkel, Willibrord de Graaf, and Sirovátka Citation2012; Künzel Citation2012; Emilsson Citation2015; Heidenreich and Rice Citation2016), both opportunities and challenges arise locally. The intention of these reforms has been to combine the resources and efforts of multiple actors locally and thereby enable synergies in the provision of individualized and flexible services. An important task for municipal authorities is to attract potential partners to the interactive governance arenas that serve (or aim to serve) as a fertile ground for social innovation (Qvist Citation2016; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2016).

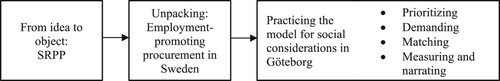

The aim of this paper is to develop knowledge about how social procurement as a tool in ALMP is practiced in local settings. We do this by analyzing the chains of translations through which the idea of social procurement is turned into practices in collaborative local arenas, using the travel-of-ideas framework from organization studies (Czarniawska-Joerges and Joerges Citation1996; Czarniawska and Sevón Citation2005). Viewed as a translation process, the significant question is not whether policies are implemented or ideas diffused, but how policy is transformed as it moves between contexts and what this transformation means for policy processes and outcomes. The paper is informed by a qualitative study of how policies for employment-promoting procurement was translated in a local initiative within the city of Göteborg, Sweden. The initiative aimed to support employment of vulnerable groups by including social criteria in the procurements of the city. By following the actions whereby the tool was made operable, categorized in the analysis as prioritizing, demanding, matching, and measuring/narrating, we show how employment-promoting procurement practices can be developed locally. We further discuss implications in terms of the governance of ALMP and social procurement practice.

In the next section, we describe and conceptualize the idea of social procurement and the particularities of procurement as a context for ALMP. We then present the analytical framework followed by a description of the case and the methods used to collect and analyze the data. In the analytical discussion, we describe and discuss the characteristics of translations at the EU, national, and local levels. Finally, conclusions are drawn and practical and theoretical implications outlined.

Social procurement as governance tool

Public procurement is considered the largest business sector in the world, accounting for on average 13 percent of GDP across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Flynn Citation2018) and steadily increasing. Governments across Europe have striven to make better use of the governing opportunities offered by the comprehensive reform of procurement practices. Using procurement to achieve social outcomes such as employment opportunities for those outside the labor market forms a key part of this ambition. The European Union (EU) procurement directives adopted in 2014 support expanding the ways procurement can be used as a tool in social policy and in a broad range of other policies:

The new rules seek to ensure greater inclusion of common societal goals in the procurement process. These goals include environmental protection, social responsibility, innovation, combating climate change, employment, public health and other social and environmental considerations. (EU Commission Citation2020)

SP is not about purchasing particular social services (e.g. when contracting out employment services) but about introducing social demands into the purchase of all sorts of services or goods (Arrowsmith Citation2010). McCrudden (Citation2004) suggests the term ‘linkage’ to describe this use of procurement. This term, he argues, is broad enough to cover the diverse ways in which social policy is intertwined with procurement. Whereas social aims in this context are additional or secondary goals, the primary goal is to achieve value for money in terms of cost and quality (Arrowsmith Citation2010; Nijboer, Senden, and Telgen Citation2017). A crucial feature of linkage is thus the conditions and restrictions that the procurement logic entails, which clearly affects the development of SP practices.

Guiding market principles

SP presents an arena for dealing with social issues, bringing new actors such as procurers of, for instance, cleaning services or transport planning into the implementation of social policy. Public procurement is commonly referred to as a process consisting of several phases or activities, extending from the identification of a need and the decision to procure it to the follow-up of the cost and quality of delivery (Grandia Citation2018). Both researchers and practitioners emphasize that each phase contains strategic considerations and decisions with far-reaching implications (Guarnieri and Gomes Citation2019) and that a broad range of values need to be balanced throughout the process.

Extensive regulations govern and restrict public procurement processes to ensure fair and efficient market exchanges through high standards of transparency, accountability, and integrity. Especially important are the EU procurement directives (European Union Citation2014a, Citation2014b), which set harmonized rules enabling real competition in which goods and services move freely across Europe in line with the ideas of the internal market. The binding and detailed rules for the procurement process regulating, for example, advertising, requirement setting, and evaluation are shaped by such market principles. Widespread criticism has been directed towards the administrative burden that counteracts precisely the market mechanisms these rules are meant to promote, although the main principles remain. These rules have not been challenged by the reform agenda that seeks to develop a more progressive view of procurement as a policy tool in which the ideas of SP are central (Grandia Citation2018). Although the legal framework has undoubtedly expanded the opportunities for integrating social considerations, the formal procedures are still conditioned by the principles of the internal market. Procurers need to follow the principle of equal treatment, giving all competitors in the EU an equal opportunity to compete for a contract. This principle is, as we show in the following, crucial for how the SP tool takes shape in practice, and for how the idea is spread and received.

Social procurement in policy and practice

SP is by no means a new idea. Early attempts to link social justice issues to procurement were made during the nineteenth century, primarily to promote fair working conditions and wages. Over time, public contracts also became a way to handle sudden rises in unemployment and to address the needs of disabled workers such as ex-servicemen (McCrudden Citation2004). Now, in the 2020s, a broad range of social aims are being advanced with the help of public procurement through a wide variety of techniques.

Regarding which social aims, in 2020 the EU Commission noted that SP could be used as a driver to promote employment opportunities and social inclusion, but also to promote several other goals, such as the following: providing opportunities for social economy enterprises; encouraging decent work; supporting compliance with social and labor rights; promoting accessibility and design for all; respecting human rights and addressing ethical trade issues; and delivering high-quality social, health, education, and cultural services (European Union Citation2020, 5). In addition, other horizontal policies (Arrowsmith Citation2010) could be advanced through procurement, such as gender equality, innovation, and environmental objectives.

Concerning how social aims are advanced in procurement, the list of measures developed is long and includes the following: dialogues with contractors; specifying social contract requirements; applying social award criteria; and reserving contracts for social enterprises (European Union Citation2020, Citation2021; Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014).

These and other techniques are increasingly cited as examples of how to realize the SP idea in policies aimed at governing procurement work in practice (e.g. Nijboer, Senden, and Telgen Citation2017). In addition to national-level policies, a growing number of local authorities are drafting sustainable procurement policies, also signaling ambitions to reform procurement practices. Comparative studies show that the content and level of ambition of these policies vary across nations and local settings (Brammer and Walker Citation2011; Hall, Löfgren, and Peters Citation2016; Nijboer, Senden, and Telgen Citation2017) as well as between ‘types of’ sustainability (Grandia and Voncken Citation2019). Furthermore, a broad range of studies have investigated the extent to which these policies are implemented in procurement practices, i.e. if and when social and environmental considerations are applied in practice. Most of these studies have focused on identifying drivers of and barriers to sustainable procurement (e.g. Hoejmose and Adrien-Kirby Citation2012; Grandia Citation2016; Lerusse and van de Walle Citation2021; Steinfeld Citation2022) to explain what causes variations in implementation.

From these studies we learn that political decisions, top management support, and key actor commitment are of great importance to successful implementation. However, how these procurement policies are put into practice and the consequences for the local context and for realizing the policies to which procurement is linked, in this case ALMP, remain largely understudied. There is a missing link in our knowledge of how SP emerges and takes shape as a tool in labor market integration policy, which is the gap we address here.

The travel-of-ideas metaphor analytical framework

Ideas and policies are necessarily transformed and shaped as they move between contexts (Czarniawska-Joerges and Joerges Citation1996), in contrast to assumptions in traditional top-down perspectives on implementation. In organizational studies, imitation is conceptualized as a basic mechanism for circulating ideas (i.e. manifested in policies) that become rational myths (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977), for example, in the case of SP. Organizations will respond with compliance strategies by adopting these ideas if they perceive benefits from following the rules of the institutional field (Oliver Citation1991). The travel of ideas does not imply the reproduction of exact copies of original ideas; instead, the travel-of-ideas metaphor has developed from a ‘diffusion’ to a ‘translation’ model, in which institutional pressure (or rather, external ideas) is translated, changed, and localized in the new organizational context (Czarniawska-Joerges and Joerges Citation1996 Czarniawska and Sevón Citation2005; Sahlin-Andersson Citation1996). Accordingly, the travel of models and policies cannot be reduced to the simple compliance, assimilation, and appropriation of policies.

SP is one such idea and procurement policies are key manifestations of it. Ideas cannot travel by themselves. When they are dis-embedded from their institutional contexts, abstracted, and simplified, they can travel with their carriers (Czarniawska Citation2002). Policy documents such as directives and strategies are carriers of ideas, materializations that are unpacked and translated to fit new contexts and become local practices.

This analysis is informed by the travel-of-ideas metaphor from organizational studies (Czarniawska-Joerges and Joerges Citation1996), which offers analytical concepts for dealing with the process by which popular ideas are translated into local action and might become institutionalized. The travel-of-ideas metaphor describes a chain of translations involving various actors who carry or use an idea and thereby contribute to its continuous transformation. What is finally re-embedded is not the idea or technology as such, but rather accounts and materializations of it (Sahlin and Wedlin Citation2008) in different local versions in different local contexts. Translation implies transformations that intentionally or unintentionally conform to specific interests (Zapata Campos and Zapata Citation2014). As mentioned above, the significant question is how a policy is translated locally, or how it is shaped by local actors to better fit local needs and knowledge.

The analysis follows the translation process, organizing the empirical material into three themes reflecting the steps of the travel-of-ideas framework. The advantage of this analytical framework is that rather than merely showing that transformations occur during the process, it enables analytical discussion of what these translations and transformations mean for labor market integration and for SP as a policy tool in this context.

Methodology

The analysis is informed by a case study (Flyvbjerg Citation2006) of an initiative in the City of Göteborg. The initiative aimed to develop a local model – Social considerations in procurement – for incorporating social criteria into procurement, with a particular focus on employment requirements for individuals outside the labor market. Göteborg is Sweden’s second largest city, with a population of approximately 590,000. From an international perspective, the Swedish municipalities (there are 290) are unusually independent (Sellers, Lidström, and Bae Citation2020). This independence means that not only are they responsible for designing and implementing welfare services, they also have the ability to set their own tax rates and are thereby responsible for the funding. As regards ALMP, Swedish local governments have far-reaching responsibility for developing and facilitating individualized services in collaboration with other local (public, private and civil-society) actors. Their role entails implementing national policies but also, to a growing degree, enabling and supporting novel initiatives from below. Attempts to develop the use of social procurement form part of these developments locally, with Göteborg seen as a forerunner (Diedrich and Hellgren Citation2018).

The target group for social procurement initiatives is unemployed individuals on public income support; however, the composition of this group differs between local governments. In Göteborg, the target group includes about 10,000 individuals, with youths, foreign-born and individuals with disabilities overrepresented. In Göteborg, 26.3% of the residents of Göteborg are foreign born (City of Göteborg Citation2020). In 2017 when we began the study, the number of newly arrived people as a result of the Syrian war was high on the agenda in the ALMP work locally.

The case: social considerations in procurement in Göteborg

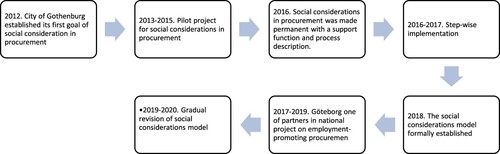

The initiative started as a pilot project in 2013 and gradually developed into the social considerations model (see for a timeline). Its aim was to facilitate the implementation of employment criteria in city administrations and companies responsible for procurements in their respective areas.

The model consists of a process description and a support function for decisions in individual procurements. It includes support for decisions on whether or not it is possible and appropriate to set employment requirements, how these requirements should be formulated, and how matching with persons from the target group should be applied.

By following the stages of the procurement process, the model introduces a number of actions and choices concerning social issues that must be taken. The support function largely organizes these employment-promoting activities in close collaboration with the responsible procurement units. This collaboration is done through support during procurement processes, for example, regarding when and how employment requirements could (and should) be set, as well as through helping contractors match potential employees to assignments during the contract period. The support function is situated within the Purchasing and Procurement Administration (the city’s strategic resource for procurement issues), which, in collaboration with the Labour Market Administration, develops the model and promotes its implementation by city administrations and companies through a broad set of communication practices.

The Göteborg initiative is considered to be at the forefront by national agencies and practitioners involved in developing SP practices, and is a source of inspiration for other local actors. As such, the model is of particular interest to study since its reach is well beyond the City of Göteborg.

Data collection and analysis

The study is part of several interconnected research projects in which we study how ALMP is organized locally, in Göteborg and in other Swedish municipalities. The study is enriched by the knowledge developed from these interconnected studies, which have helped us develop an in-depth understanding of the case as well as fruitful contrasts between ALMP in different localities (Ridder, Hoon, and Baluch A Citation2012). This paper builds on the material that focuses particularly on the development of the Göteborg model.

The data comprise open-ended face-to-face interviews (Kvale Citation1996), web-based text and models, and documents. The interviews were conducted at both the national level (i.e. at the National Agency for Public Procurement and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions) and the local level with city officers. Fourteen interviews with 20 persons were conducted between 2017 and 2020. When we initiated the study, the model was quite new as a permanent operation; it had been run as a project from 2013 to 2015. In 2017, the work was about further establishing roles and relationships and disseminating information about employment requirements in the city’s own procuring units. Over time, the model became well known and methods were successively developed. The conditions changed during 2019 and 2020 with a significantly smaller number of newly arrived people and lower unemployment rates, which changed the composition of the target group. Changes in the application of the model resulted, which we could follow up on in interviews in the latter part of the study. In this way we could see the dynamics and continuous adaptation in the local context.

The interviewees were chosen based on their centrality in working with social considerations. We started with project initiators and members of the support function, and later included actors which we understood were central or could offer important perspectives. Actors outside the City of Göteborg were also included since local practices were shown to be highly intertwined with actors and activities in other sites.

All interviewees (i.e. procurers, project leaders, and coordinators) were involved in creating and implementing employment requirements for procurement in national authorities and organizations and in the City of Göteborg. One interviewee is a project leader in Newham, London, whose local model functioned as an inspiration for the development of the Göteborg model, which demonstrates a typical way that social innovations are spread between local contexts. Since we wanted to follow up on how projects and work practices develop over time, some people were interviewed more than once. Most interviews lasted 45 minutes to an hour, were conducted in the interviewees’ offices, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. We usually began by asking the interviewees to tell us how they began to work with SP, how they got to know about SP in their organization, and how they have worked with SP since. The interviews were, as we mention above, open-ended meaning that the interview process is flexible and conversational in character where we as researchers seek knowledge from the person we talk to, based on their experiences and understanding of their position in a process. The interviewees were therefore chosen for her or his specific knowledge and subjective attitudes on the subject of research. Thus, the questions and in what order they were asked, varied for each interviewee and were followed up differently depending on the answers (Kvale Citation1996). We have, in the interview conversations, talked around certain themes rather than following a strict interview guide (see Appendices for interview themes and an overview of the interviews).

We have also analyzed text material such as the following: two web-based models, the Göteborg model and a national model for employment requirements; policy documents at both the national and city levels (e.g. national investigations, political goals, and strategies); various informational material about the ambitions, models, and ways forward (e.g. websites, folders, and PowerPoint presentations). Furthermore, since work was organized in projects, there are applications and descriptions that illustrate goals, intended effects, and plans for implementation.

All material was used in a complementary and non-hierarchical manner. Our research strategy began inductively with collecting and coding data on the department of procurement in Göteborg, then snowballing until we could reconstruct the multi-layered translation of SP in Göteborg. In the initial coding and analysis, we applied the travel-of-ideas metaphor and sorted our data into categories. As the categories, or phases, of the process became clearer to us, we continued by completing data collection and refining our analysis more abductively, following these phases (Charmaz Citation2017). Below is our description of the process we followed in tracing the translation of the policy to practice, with the last step – Putting the model into practice – structured after the phases prioritizing, demanding, matching, and measuring and narrating.

Promoting labor market integration through procurement: from policy to practice

In this section, we describe and discuss employment-promoting procurement, in particular, the actions by which it translates to local-level policies and practices, using the Göteborg social considerations initiative as an illustration. The section follows the chain of translations, as visualized in .

From idea to object: SRPP

In line with the intention to strengthen the social dimension of European cooperation, the EU has for several years actively promoted the increased use of procurement in driving social and employment policies. Socially Responsible Public Procurement (SRPP) is the term commonly used at the EU level for this. However, aligned with the turn towards sustainability, SRPP is increasingly combined with Green Public Procurement (GPP) under the common label Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP). These terms and abbreviations abound in the discourse, signaling their conceptual status.

Several EU institutions are key players in constructing, disseminating, and translating these concepts further, into soft law, legal opinions, and funding, all crucial for the development of local practice. The EU Commission actively works to facilitate the uptake of social criteria, for example, through the guide Buying Social (EU Citation2021), which demonstrates the benefits of SRPP and explains, from a legal perspective, how social issues can be addressed in different phases of the procurement process. The Commission also arranges workshops and seminars, initiates studies, and publishes support material. The European Social Fund (ESF) stands behind a large number of SRPP projects, and through funding criteria, application procedures, and feedback requirements it helps shape the development of local practice (as well as making it project based). Furthermore, the Court of Justice of the European Union clarified, in a series of landmark cases, the limits in law to integrating social considerations into procurement.

Several early local initiatives in the UK, the Netherlands, and France came to be seen as precursors. While they aimed at meeting local employment and social needs, the Commission helped to decontextualize and translate them into the general concept of SRPP. This concept, which forms a script for action (albeit vague) is continuously updated as local practice develops. Bilateral cooperation between national and local authorities across the EU, which the Commission aims to facilitate, is thus an engine driving the travel of the idea.

The SRPP concept promoted by the Commission includes various examples of what social considerations might be and of different practical approaches (European Union Citation2020; Citation2021). As presented, SRPP requires both policy and practice. The concept thus offers suggestions for how to create an organizational strategy for the implementation of SRPP as well as suggestions for actions to take at various stages of the procurement process. For instance, it is suggested that procuring actors should consider at preparatory stages whether social objectives ‘fit the procurement’, what type of considerations fit, and how these should be expressed in tender documents and contracts. In Buying Social, these and other decisions are outlined and summarized in boxes, clarifying what is and is not permitted. For example:

For example, if an award criterion focuses on how the wellbeing of elderly people will be improved under a contract, bidders may rely in part on a policy which defines their approach to engaging with service users and training staff. It would not be appropriate however to award marks based on activities which bidders carry out under other contracts. (European Union Citation2021, 72)

Unpacking: employment-promoting procurement in Sweden

The EU-level packaging provides a number of arguments as to why procurement should be used as a means in ALMP, but it does not contain much guidance for local action. Rather, it iterates that there is no one-size-fits-all strategy, but that local practice must be based on local circumstances. Inspired by this approach, municipalities (in Sweden and elsewhere) have developed local models for how to utilize the procurement procedures and contractual arrangements to create employment opportunities for individuals who face barriers in the labor market. As such, these local models are brought forward as a promising part of localized ALMP work. In assessing the appropriateness, EU-level carriers emphasize local market characteristics, for example, the degree of competition and maturity of the industry. National- and local-level actors in Sweden instead emphasize labor market characteristics, such as recruitment needs and existing competencies in the target groups. This difference regarding what the important local conditions are reflects a clear and crucial shift in perspective as the general concept meets the context in which it is to be applied.

In Sweden, the promotion of employment opportunities through procurement is high on the political agenda, with the national government having pursued an extensive reform to pave the way for a new approach to and use of procurement. The establishment of the National Agency for Public Procurement in 2015 forms part of this new approach, as does the adoption of a national procurement policy in 2016. The intention has been to release procurement from an overly narrow legal framing and make it into ‘a strategic tool for doing good business’ (National Procurement Strategy Citation2016, 8). The expression ‘good business’ aims to capture the broad set of values that contracting authorities should take into account. Regarding labor market integration, two overarching methods are mentioned in the policy: using social clauses and enabling idea-driven organizations or social enterprises to compete for public contracts.

Through its assignment to drive the development of procurement work, the National Agency for Public Procurement recently launched the national model ‘Employment promotion in public procurement’, which serves to disseminate knowledge and guide practice. The model consists of web-based support with a checklist of questions to ask during the procurement process about matters ranging from planning, mapping, and analysis to implementation and management. As described, setting employment requirements is a ‘complex process’ that involves many roles. However, as pointed out in a folder summarizing the model, ‘That it is complex does not have to mean that it is difficult’ (The National Agency for Public Procurement Citation2019, p. 3).

Through its combination of rhetorical and practical elements, the model largely reflects the EU-level concept, although in slightly more concrete terms. When unpacking the EU concept, some dimensions are downplayed while others are highlighted in view of local interests and settings. The EU internal market principles are downplayed; instead, well-functioning local markets and labor markets are at the center. Also, the rather complicated legal balancing act described by the EU institutions is replaced by a framework in which it is not difficult to incorporate social considerations and opportunities outweigh the risks. Furthermore, the benefits to the business community are emphasized. It is a win-win-win situation, it is argued, in which not only individuals (through being integrated into labor markets) and society (through reduced unemployment and increased inclusion) are winners, but also the business community (through skills supply and an opportunity to grow).

In sum, while labor market issues become more obvious as the general concept of SRPP is unpacked, those issues converge on skills matching and supply rather than integration and social inclusion. As we will show in the following, this shift in perspective is decisive for further translations.

Putting the model into practice for social considerations in Göteborg

The social considerations project in Göteborg clearly takes support and inspiration from contemporary changes in procurement regulations and international cooperation, though it is described as largely built from below. Early initiative was taken by a group of committed civil servants in one vulnerable city district, which resulted in a feasibility study funded by the ESF, during which study visits to the Newham district of London were carried out. Their model served as inspiration for the development of the Göteborg local model. The Göteborg model is explicitly linked to the local political goal of creating an inclusive and socially sustainable city and to the desire that procurement should increasingly be used in this endeavor. In 2014, a stipulation was given to the entire city organization and all city companies that ‘50 percent of all service procurement should include social considerations’ (City of Göteborg Citation2015, 5). It was the mission of the support function established by the project to realize this goal.

Four categories of activities are particularly crucial for the model and the outcomes of its use. They are: prioritizing, by which multiple opportunities regarding contracts and individuals are narrowed down; demanding, i.e. setting requirements that form the basis of the model; matching, by which jobs and individuals are brought together; and measuring and narrating, which are central to the communication practices and guide further action. In what follows, we describe these four activities more thoroughly.

Prioritizing is a key activity through which a series of clarifications of the elements of the model are made that enable further action. First, in the Göteborg model, three prioritized target groups were identified, namely migrants, youths and persons with disabilities, and individuals (in these groups) were to receive income support. The decision to focus on these groups was based mainly on social arguments such as strengthening equality across the city and counteracting unemployment among individuals at risk of social exclusion. These arguments largely reflected social discourse and local sustainability objectives. Socioeconomic arguments based on levels of municipal costs for income support were also presented. An estimate repeatedly cited was that about 3000 of the 10,000 individuals who were long-term dependent on income support were ‘basically immediately job ready’, which made them ‘an appropriate recruitment base’ (City of Göteborg Citation2015, 7). The web-based support to contractors states:

For example, it could be a person who, due to a foreign name, has not been given the opportunity to be interviewed. We may find the person you are looking for but one who does not reach you via traditional applications. (City of Göteborg Citation2020)

Second, criteria were developed for prioritizing which procurements were suitable for social considerations. One such criterion was that the contracts needed to be sufficiently large, as the larger size would provide more employment opportunities and safeguard suppliers from the extra ‘burden’ of social requirements. Additionally, there should be recruitment needs in the industry, something that was seen as beneficial for employment possibilities even after the contract period. Taking recruitment needs into account was also seen to promote good relations with market actors. Another criterion was the availability of job-ready individuals with the types of skills needed for the potential employment, a requirement for the matching work to be effective. However, it was also a contractual issue, since the purchaser is bound by the contract as much as the provider. It is not feasible to set employment requirements and then not deliver any candidates, as one interviewee explained.

The construction sector has been shown to score high on these criteria, a finding also encountered in the use of the tool in other countries. One interviewee reflected on this:

The people who get these jobs are mostly men. It is a problem … we have started trying to look at educations that are not in construction. In construction, we work very systematically to encourage people [to enter] into the construction industry and inspire them with a small course and so on. Can you do that with any other industry? (Interview, procurement officer)

Demanding is another key activity. In fact, making demands constitutes the core of the model, which distinguishes it from other activation-promoting tools. The possibility of using the contract as a basis for employment issues is seen by most as a great opportunity. The contract both works as a ‘door-opener’ and strengthens the position of the local authority in dialogues with private enterprises about issues relating to social considerations. At the same time, demanding is perceived as double edged. The collaborative and dialogue-based tradition within labor market integration is strong, and there was no intention of challenging it either: ‘If we want companies to get involved socially, for instance, by employing someone far outside the labor market, we will succeed only through good relationships’.

One way in which this dilemma of demanding within collaboration was handled is through the somewhat creative contractual solution of setting requirements for dialogue. This solution was not unique; it is mentioned in the Commission guide as one of several measures available. In Göteborg, requirements for dialogue meant that the contractor is required to discuss, on one or more occasions during the contract period, employment opportunities with city representatives. Such dialogue depends on a number of circumstances, such as the will of the contractor, which undeniably makes the outcome more uncertain. However, it is seen as a promising technique by the actors involved. One interviewee said: ‘Employment requirements must be set, then if there are dialogue requirements, so be it. But it’s like this, it’s about us’. It’s also a way to inform suppliers: ‘This is how the city works’ (Interview, procurement officer).

Although requirements for dialogue were among the opportunities available to procurement officers, early in the process the project group can decide that the focus should be on ‘strict demands’, i.e. requirements to employ people, not ‘only’ to have dialogues about future employment opportunities. It was also decided that the demands should refer to real employment opportunities, rather than to trainee or internship positions. This decision was prompted in part by the fear of displacement effects in the labor market, but was also due to the focus on job-ready individuals. There is no good reason, it was argued, to offer an internship to someone whose problem is that s/he has not been reached through regular applications because of having a foreign name.

Several key decisions on when and what demands were to be set depended on the prioritization of the target group of 3000 job-ready individuals. Developing matching services rather than integration measures is consistent with this priority. A stronger economy and declining unemployment over time has brought about changes in the target group, with candidates now being available. In a situation such as this, there is a question about how the techniques developed can meet the needs of other individuals, for example, those further from the labor market. Increased use of dialogue requirements is thus actualized, as are traineeships and internships. The rhetoric of skills supply is downplayed while the argument that enterprises should make a social contribution – perhaps even strengthening their corporate social responsibility profile – remains.

The third activity is matching, referring to various actions taken to connect potential jobs with potential candidates, partly by calibrating the two so that they fit. For instance, education could be used to calibrate individuals to fit the needs of a contractor, and assignments could be specified so that actual competences in the target group could be identified. These activities are portrayed and handled within the model as fairly uncomplicated, unlike the usual multifaceted processes of integration. The aim, as described by one interviewee, is to more or less copy the procedures of regular recruitment processes, but with the difference that the candidates are selected by city administrators.

The matching activities involve several actors: the contractor, who describes the assignment and competence needed, arranges the recruitment process and chooses among the candidates; the individual job candidate who is to take part in the recruitment process, whatever its elements; and the matching function in the city administration, which acts to identify candidates and support both them and the contractor during the recruitment process. Although city administrators can help firms apply for financial employment support, this help should not be the starting point, as stressed by one interviewee:

If the person who suits you happens to have the right to certain things, we can definitely take advantage of it. But companies cannot say ‘we want to hire a person entitled to employment support’. No, we do not work that way. (Interview, labor market administration officer)

Matching activities also occur at an overall level via choices as to which sectors and procurements to focus on. In this case, matching is a kind of strategic and analytical undertaking that takes both the needs and competences of the target group and the recruitment needs of local businesses into account. It is also a process of trial and error. One interviewee described early attempts to approach the cleaning industry that failed since the working conditions were too poor. In this case, employment requirements did not show a path forward.

A fourth category of activities is measuring and narrating, which contribute greatly to making the model operable. A problem cited by several interviewees is that follow-up at the individual level is difficult since individuals who no longer receive income support are also not (or do not want to be) cases for city administrators. The only indicator of outcomes in terms of labor market integration and future employment is thus whether or not the individuals return and apply for income support. What happens to those who do not is unknown, though a reasonable guess is that they are employed and supporting themselves.

In light of the political goal of applying social considerations in 50 percent of service procurements, it is unproblematic to measure success as the number of employment requirements set and individuals matched, criteria that are continuously measured and reported. The 2019 report on social considerations states that 218 individuals from Göteborg obtained employment through social considerations in procurement with the city’s suppliers (City of Göteborg Citation2019). Of these, 140 are reported to be ‘deviations’. Deviations, one interviewee explained, refer to procurements in which employment requirements have been used, but the model has not been applied. Deviations are thus deviations from the model itself but where the goal (setting requirements) is still achieved. By the introduction of a routine to measure and report these situations, the success story of the approach was further enhanced.

Another essential part of the narrative is the socioeconomic benefit. Setting employment requirements in procurement is socioeconomically profitable, it is argued. This argument is supported by calculations of socioeconomic effects that form part of the final project reporting. Also, it is strongly supported by national-level developments in which a web-based calculator has been produced for estimating socioeconomic benefits.

If measurements of outcomes were absent, there is ample anecdotal evidence of success. Anecdotes are seen as important input to the further development of the model and essential to communicating the model’s benefits. The project is successful in that it has already been ‘rolled out’ and, over time, has become increasingly accepted among managers and procurement officers in at least some of the city’s administrations and some companies. The intensive initial work to anchor the idea has gradually eased. The Göteborg model is also seen as successful by national-level actors, for example, the National Agency for Public Procurement and the Swedish Association of Local Governments and Regions. This recognition of success has contributed greatly to spreading the idea that Göteborg is a forerunner in SP. While the work of creating the model could be seen as a process of picking up and unpacking various objects and concepts (e.g. the SP concept and the Newham local model), it has itself become an object that can travel further on its own.

Conclusions

This paper set out to explore the translations through which the idea of SP is turned into employment-promoting practices in local arenas and what this process of translation means in terms of governance and for the organizations involved. The point of departure was that policy tools are not neutral instruments but they shape the substance of policy in decisive ways. In other words, the ways by which a policy is translated into practice are crucial for what the policy ‘becomes’. In our case, we critically explored how the idea of promoting employment of vulnerable groups through public demand and purchasing power was translated into local practices in which social inclusion was turned into a value (and into criteria) in procurements for a wide range of goods and services. As our analysis reveals, through the various translations of the idea of purchasing ‘social goods’ (Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014) largely became a practice of providing competence to private enterprises. How did that happen and does it matter?

Our analysis shows that a broad set of actions contributed to making the local SP model operable. Through prioritizing, demanding, and matching, the actors involved established a target group, decided on criteria for appropriate procurements, transformed demands into contractual requirements, and connected (potential) jobs to (potential) employees. Facilitating these actions were extensive practices of measuring success and communicating the narrative of the untapped potential of procurement as an employment-promoting tool as well as supporting the local business community. These actions largely contributed to spread and anchor novel practices within and beyond the city organization. In doing so, the SP model has successfully been anchored and a new arena for labor market inclusion of vulnerable groups has been created.

The long-term consequences of using this new arena, for the municipality and the unemployed, is beyond the scope of this study. However, SP entail a different role for the municipality that entail both opportunities and risks. As an idea, SP clearly diverges from most ALMP tools used locally in that it equips public authorities with a governing capacity that enables them to contractually force actors to enter local partnerships. At the same time, they uphold the collaborative spaces created to support problem-solving from below (Skelcher, Mathur, and Smith Citation2005; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2016). While this balancing act of handling the mixed modes of governance characteristic of local ALMP policy is documented in previous research (Qvist Citation2016; Heidenreich and Rice Citation2016; Barraket Citation2020; Norbäck and Campos Citation2022), SP clearly introduces new actors, roles, and relations into the local arena where contractual enforcement becomes as much a risk as an opportunity. From a policy perspective, there is the risk that the tool might counteract the governance logic by reverting to top–down command, undermining the self-regulatory capacity of collaborative partnerships (Sørensen and Torfing Citation2016) and, as a consequence, inhibit other arena and interactions that benefit the situation of unemployed. At the same time, from a procurement perspective, there is the risk that SP might oppose the market logic by introducing elements that potentially hinder competition. This paper shows that actors, through local translation, managed to navigate between these risks, in our case, mainly with the help of the competence provision narrative which all local actors gravitated towards and could gather around.

SP frames procurement as an instrument by which social policies (whatever these are) can be implemented and as such is portrayed as neutral in relation to policy content. This framing clearly strengthens the applicability of the idea and enables a collective imagination about a better future (Völker, Kovacic, and Roger Strand Citation2020). However, as shown in this paper and in previous studies of the governance of ALMP, operational and technical aspects accommodate highly political issues (Swinkels and van Meijl Citation2020; van Berkel, Willibrord de Graaf, and Sirovátka Citation2012; Ek Österberg et al. Citation2022). By focusing on the process of translation, these political aspects are brought to the fore. For instance, how the process causes certain groups of the unemployed to be prioritized over others. As shown, the internal market principles are unconditional – a particularity of procurement as a context for ALMP measures that should be taken into account (Olsson and Öjehag-Pettersson Citation2020). Whereas local ALMP practices start in local needs, goals and initiatives, public procurement is based on the principle of eliminating barriers to competition and the rights of all European enterprises. The SP tool thus entails the paradox that local needs are to be met using techniques aimed at forcing local authorities to look beyond the local. Although using public contracts to support social inclusion is a promising idea, the administrative apparatus required to make this possible therefore warrants consideration by scholars as well as policy makers. As shown in the paper, for employment requirements to actually have an effect of the situation of the unemployed in most need of support, the requirements must not only be made. These must also result in actual employments, while persons who are most in need of support are selected for the employments. Following-up on only requirements-setting should therefore be complemented with follow-ups of which jobs are created and for whom.

We built our conclusions on the single case (Flyvbjerg Citation2006) of the social procurement model in Göteborg, which of course limits generalizability. The characteristics of the practices observed in the study should be understood in relation to its context. Some of the practices are likely to be valid in other local contexts and for models elsewhere, but the significance of the particularities of the Swedish and Göteborg setting for the results of the study needs to be explored in further studies.

The study has generated further questions to be addressed in future research. First, as local dynamics influence the process and its outcome, more cases should be compared and contrasted if we are to improve our understanding and formulate theory and more robust policies. Second, all local governments are parts of networks. As these networks comprise multiple actors, all with their own logics and views regarding the SP processes, further studies that include more actors would shed light on the process from a broader perspective. Third, a study focusing the consequences for the unemployed should be a priority.

Ethical approval

Approval for this research has been tried by the The ethical committee of Göteborg (Regionala etiksprövningsnämden i Göteborg) who in decision 913-18 November 2018 decided that the research did not need ethical approval.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Ek Österberg

Emma Ek Österberg is associate professor at the School of Public Administration, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her research interests concern governing and organizing of welfare policies, auditing, marketization and public procurement.

Patrik Zapata

Patrik Zapata is a professor of Public Administration at the School of Public Administration, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. His research interests concern the management of cities, sustainable organizing, waste management, labour market integration and language in organizations.

References

- Arrowsmith, Sue. 2010. “Horizontal Policies in Public Procurement: A Taxonomy.” Journal of Public Procurement 10 (2): 149–186. doi:10.1108/JOPP-10-02-2010-B001.

- Barraket, Jo. 2020. “The Role of Intermediaries in Social Innovation. The Case of Social Procurement in Australia.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 11 (2): 194–214. doi:10.1080/19420676.2019.1624272.

- Brammer, Stephen, and Helen Walker. 2011. “Sustainable Procurement in the Public Sector: An International Comparative Study.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 31 (4): 452–476. doi:10.1108/01443571111119551.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2017. “Constructivist Grounded Theory.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (3): 299–300. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1262612.

- City of Göteborg. 2015. “Social Considerations in Public Procurement”. Project Report and Proposals for Working Model and Organization.

- City of Göteborg. 2019. “Social Considerations, Full Year Report”.

- City of Göteborg. 2020. “Vad innebär kraven för dig som arbetsgivare”[This is what the Demands Mean for You as an Employer]. Webpage:https://socialhansyn.se/om-pilotprojektet/for-leverantorer/hur-gar-det-till-i-praktiken/).

- Czarniawska-Joerges, Barbara, and Bernward Joerges. 1996. “The Travel of Ideas.” In In: Translating Organizational Change, edited by Barbara Czarniawska and Guje Sevón, 13–48. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2002. A Tale of Three Cities. Or the Globalization of City Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Czarniawska, Barbara, and Guje Sevón. (Eds). 2005. Global Ideas: How Ideas, Objects and Practices Travel in the Global Economy. Copenhagen: CBS Press.

- Diedrich, Andreas, and Hanna Hellgren. 2018. “Organizing Labour Market Integration of Foreign-Born Persons in the Gothenburg Metropolitan Area.” Gothenburg Research Institute GRI-Rapport 2018: 3–38.

- Ek Österberg, Emma, Nanna Gillberg, Maria Norbäck, Patrik Zapata, and María José Zapata Campos. 2022. “Local Governments as Employer, Procurer, and Entrepreneur in Labour Market Integration.” School of Public Administration Working Paper Series 2022 (35): 3–37.

- Emilsson, Henrik. 2015. “A National Turn of Local Integration Policy: Multi-Level Governance Dynamics in Denmark and Sweden.” Comparative Migration Studies 3: 7. doi:10.1186/s40878-015-0008-5.

- EU. 2014a. “Directive 2014/25/EU, of the European Parliament and of the Council: ‘On Procurement and repealing.’” 2004/18/EC.

- EU. 2014b. “Directive 2014/25/EU, of the European Parliament and of the Council: ‘On Procurement by Entities Operating in the Water, Energy, Transport and Postal Services Sectors and Repealing.’” 2004/17/EC.

- EU Commission. 2020. Website, “EU Public Procurement Directives”. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/eu_public_directives_en.htm, retrieved 2020-08-27.

- European Union. 2020. ‘Making Socially Responsible Procurement Work’: 71 Good Cases.

- European Union. 2021. ‘Buying Social. A Guide to Taking Account of Social Considerations in Public Procurement. 2nd ed.. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Flynn, Anthony. 2018. “Measuring Procurement Performance in Europe.” Journal of Public Procurement 18 (1): 2–13. doi:10.1108/JOPP-03-2018-001.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Furneaux, Craig, and Jo Barraket. 2014. “Purchasing Social Good(s): A Definition and Typology of Social Procurement.” Public Money & Management 34 (4): 265–272. doi:10.1080/09540962.2014.920199.

- Grandia, Jolien. 2016. “Finding the Missing Link: Examining the Mediating Role of Sustainable Public Procurement Behaviour.” Journal of Cleaner Production 124: 183–190. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.102.

- Grandia, Jolien. 2018. “Public Procurement in Europe.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Public Administration and Management in Europe, edited by Edoardo Ongaro and Sandra van Thiel, 363–380. London: Springer.

- Grandia, Jolien, and Dylan Voncken. 2019. “Sustainable Public Procurement: The Impact of Ability, Motivation and Opportunity on the Implementation of Different Types of Sustainable Public Procurement.” Sustainability 11(19): 5215. doi:10.3390/su11195215.

- Guarnieri, Patricia, and Ricardo Gomes. 2019. “Can Public Procurement be Strategic? A Future Agenda Proposition.” Journal of Public Procure 19: 295–321. doi:10.1108/JOPP-09-2018-0032.

- Hall, Patrik, Karl Löfgren, and Gregory Peters. 2016. “Greening the Street-Level Procurer: Challenges in the Strongly Decentralized Swedish System.” Journal of Consumer Policy 39: 467–483. doi:10.1007/s10603-015-9282-8.

- Heidenreich, Martin, and Deborah Rice. 2016. “Integrating Social and Employment Policies in Europe.” In Active Inclusion and Challenges for Local Welfare Governance”, edited by Martin Heidenreich and Deborah Rice. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Hoejmose, Stefan U., and Adam J. Adrien-Kirby. 2012. “Socially and Environmentally Responsible Procurement: A Literature Review and Future Research Agenda of a Managerial Issue in the 21st Century.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 18 (4): 232–242. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2012.06.002.

- Künzel, Sebastian. 2012. “The Local Dimension of Active Inclusion Policy.” Journal of European Social Policy 22 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1177/0958928711425270.

- Kvale, Steinar. 1996. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitive Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lerusse, Amandine, and Steven van de Walle. 2021. “Local Politicians’ Preferences in Public Procurement: Ideological or Strategic Reasoning?” Local Government Studies, 1–24. doi:10.1080/03003930.2020.1864332.

- McCrudden, Christopher. 2004. “Using Public Procurement to Achieve Social Outcomes.” Natural Resources Forum 28: 257–267. doi:10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00099.x.

- Meyer, John W, and Brian Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363. doi:10.1086/226550.

- The National Agency for Public Procurement. 2019. National Model for Employment Requirements in Public Procurement. Stockholm: Information folder.

- National Procurement Strategy. 2016. The Swedish Government, Ministry of Finance.

- Nijboer, Kimberly, Shirin Senden, and Jan Telgen. 2017. “Cross-country Learning in Public Procurement: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Public Procurement 17 (4): 449–482. doi:10.1108/JOPP-17-04-2017-B001.

- Norbäck, Maria, and María José Zapata Campos. 2022. “The Market Made us do it: Public Procurement and Collaborative Labour Market Inclusion Governance from Below.” Social Policy & Administration 56: 632–647. doi:10.1111/spol.12787.

- Oliver, Christine. 1991. “Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes.” The Academy of Management Review 16 (1): 145–179. doi:10.2307/258610.

- Olsson, David, and Andreas Öjehag-Pettersson. 2020. “Buying a Sustainable Society: The Case of Public Procurement in Sweden.” Local Environment 25 (9): 681–696. doi:10.1080/13549839.2020.1820471.

- Qvist, Martin. 2016. “Activation Reform and Inter-Agency Co-Operation – Local Consequences of Mixed Modes of Governance in Sweden.” Social Policy and Administration 50 (1): 19–38. doi:10.1111/spol.12124.

- Ridder, Hans-Gerd, Christina Hoon, and Alina Mccandless Baluch A. 2012. “Entering a Dialogue: Positioning Case Study Findings Towards Theory.” British Journal of Management 25 (2): 373–387. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12000.

- Sahlin-Andersson, Kerstin. 1996. “Imitating by Editing Success: The Construction of Organizational Fields.” In Translating Organizational Change, edited by B. Czarniawska and B. Joerges, 69–92. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Sahlin, Kerstin, and Linda Wedlin. 2008. “Circulating Ideas: Imitation, Translation and Editing.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, Sage Publications, edited by R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, and R. Suddaby, 218. London: Sage.

- Sellers, Jefferey M, Anders Lidström, and Yooil Bae. 2020. Multilevel Democracy: How Local Institutions and Civil Society Shape the Modern State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Skelcher, Chris, Navdeep Mathur, and Mike Smith. 2005. “The Public Governance of Collaborative Spaces: Discourse, Design and Democracy.” Public Administration 83 (3): 573–596.

- Sørensen, Eva, and Jacob Torfing. 2016. “Metagoverning Collaborative Innovation in Governance Networks.” American Journal of Public Administration 47 (7): 719–736. doi:10.1177/02750740166431.

- Steinfeld, Joshua M. 2022. “Leadership and Stewardship in Public Procurement: Roles and Responsibilities, Skills and Abilities.” Journal of Public Procurement 22 (3): 205–221. doi:10.1108/JOPP-04-2021-0024.

- Swinkels, Michiel, and Toon van Meijl. 2020. “Performing as a Professional: Shaping Migrant Integration Policy in Adverse Times.” Culture and Organization 26 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1080/14759551.2018.1475480.

- Troje, Daniella, and Pernilla Gluch. 2020. “Populating the Social Realm: New Roles Arising from Social Procurement.” Construction Management and Economics 38 (1): 55–70. doi:10.1080/01446193.2019.1597273.

- van Berkel, Rik, Rikand Willibrord de Graaf, and Tomáš Sirovátka. 2012. “Governance of the Activation Policies in Europe: Introduction.” The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 32 (5/6): 260–272. doi:10.1108/01443331211236943.

- Völker, Tom, Zora Kovacic, and Roger Strand. 2020. “Indicator Development as a Site of Collective Imagination? The Case of European Commission Policies on the Circular Economy.” Culture and Organization 26 (2): 103–120. doi:10.1080/14759551.2019.1699092.

- Zapata Campos, María José, and Patrik Zapata. 2014. “Translating Development aid Into City Management: The Barrio Acahualinca Integrated Development Programme in Managua, Nicaragua.” Public Administration and Development 33 (2): 101–112. doi:10.1002/pad.1628.

Appendices

Appendix 1: interview themes

Broad frame for questions to interviewees that work with the social considerations model in Göteborg. The questions were adapted and deepened depending on the role of the interviewee (examples of questions in italics).

START: How did it start, from your perspective? Who, when, why? The history of social procurement, and/or the social considerations model.

ROLE: What is your role? Now, before? Other roles?

ACTIONS: What do you do in that role? Work practices, routines. Exemplify

PARTNERS: Collaborating partners. Individuals, organizations. Who, when, how, why? How often?

MODEL: The social considerations model, how does it work when in use? Describe the process. Who initiates, who gets involved and how? Target groups? Criteria, contracts, collaboration, follow-up?

IMPLEMENTATION/ANCHORING WITHIN THE CITY ORGANIZATION: Is the model welcomed, resisted, why, by whom? Similarities and difference in how the model is seen? Development over time?

IMPLEMENTATION/ANCHORING OUTSIDE THE CITY ORGANIZATON: Among contractors, trade unions, business community, others? Is it welcomed, resisted, why, by whom, similarities and difference in how the model is seen? Development over time?

FOLLOW-UP: On requirement setting, outcomes, target groups? Describe the process for follow-up? Formal and informal follow-up. Does it work well? Challenges?

EFFECTS: What effects have you seen, from your point of view? In terms of job opportunities (for whom), activation, other effects?

SYNERGIES: Are there other actors or processes involved, synergies?

SCALING-UP, LEARNING: Who do you learn from, and who learns from you? Study visits, networks?

SUCCESS FACTORS: What drivers and barriers to success do you see? What would you like to change?

DEVELOPMENT: How do you think the model and its use will be one year from now? Decisive decisions to come?

Is there anything to add, that we have not asked?