Abstract

This paper brings forth an empirical study of organizational resilience strategies in standard setting. The selection of ETSI (The European Telecommunications Standards Institute) as a case study for this purpose was motivated by ETSI's legal status as an ESO (European Standardization Organization), global impact, and the history of external criticism directed at the organization. Based on theoretical considerations and author's previous empirical research, it was expected that the organizational resilience strategies used by ETSI differ with regards to two dimensions: anticipation of the disturbance (proactive and reactive strategies); and the locus of the strategic effort (internal or external to the organization). A combination of deductive and inductive content analysis was applied to 12 semi-structured interviews with individuals who participate in standard setting activities within ETSI. The conducted analysis confirmed the expected 2 × 2 type of taxonomy determined by anticipation and locus of strategic effort. The identified 29 categories were thus categorized into four clusters of resilience strategies: proactive external (5), proactive internal (9), reactive external (5) and reactive internal (10) strategies. The discussion reflects on the historical organizational challenges, the resilience strategies reported in response to them, and how they might have contributed to continued thriving of ETSI despite organizational challenges.

Introducing the organizational resilience framework

The organizational resilience literature is vast, likely due to the inevitability of changes and challenges caused by new market developments and innovation, as well as internal or external disturbances and crises that organizations face. Within this literature, any event or process that threatens the organizational functioning and/or performance can be considered a disturbance (Williams et al. Citation2017). The ability of organizations to successfully adapt to such disturbances is termed organizational resilience (Mafabi, Munene, and Ahiauzu Citation2015). The disturbances can be of internal or external origin relative to the organization, and the efforts to deal with the disturbance can similarly be focused internally or externally (Annarelli and Nonino Citation2016). In the management literature, resilience as a relevant characteristic of organizations gained traction due to the increased complexity and interconnectedness of dynamic systems that organizations operate with and within, making therefore adaptation to changing conditions a salient need, as shocks and disturbances that organizations encounter become ever more frequent.

Perhaps most notable example of this is the increased interest in resilience engineering, defined as anticipation of unexpected events and minimizing the effects of such shocks and disturbances on the organization – i.e. proactive risk management (Patriarca et al. Citation2018; Woods Citation2006; Citation2015; Woods, Leveson and Hollnagel Citation2017). Moreover, proactive risk management strengthens the organization and proactively contributes to overall resilience (Citation2023). Successful adaptation, however, must also rely on accepting uncertainty, and flexibly dealing with disturbances upon their inevitable occurrence (Vogus and Sutcliffe Citation2007). The mechanisms behind organizational resilience, termed in this article resilience strategies, can therefore be proactive or reactive with regards to their temporal position relative to the disturbance (Weick and Sutcliffe Citation2015).

While the concept of resilience can seem straightforward, there are nuances that make the construct a multidimensional one. For example, three outcomes are possible with regards to organizational resilience, namely survival, recovery and thriving (Ledesma Citation2014). These outcomes differ in terms of the relative level of functioning of the organization before and after the disturbance, whereby survival signifies that organizational functioning is somewhat impaired compared to the pre-disturbance functioning; recovery signifying the level of functioning is restored or maintained to the same degree as before the disturbance; and thriving signifying that the functioning of an organization is improved compared to the pre-disturbance state.

Among the different possible combinations of factors related to resilience (i.e. responding to internal or external disturbances; approaching resilience proactively or reactively; resulting in survival, recovery or thriving), some cases are arguably more consequential and controversial than others. A particular type of organizational resilience stands out in this sense, namely the resilience of organizations that experience disturbances due to internal factors, particularly when internal factors become target of external criticism; and yet, manage to resolve such crises in a way that further increases the success and power of the organization. This particular case of thriving embodies the dual nature of organizational resilience as a normative concept – while it is generally desirable for the organization to resiliently face challenges, this may not always be desirable from a broader, systems theory point of view – one that includes the interconnected systems within which organizations are nested (Von Bertalanffy Citation1972).

The relevance of maintaining a broader perspective on resilience is captured within one of the most influential approaches to resilience – the dynamic system approach of panarchy (Gunderson and Holling Citation2002; Holling Citation2001). This approach recognizes the interdependency of nested social, ecological, and the combined socio-ecological systems. Within the panarchy approach, organizational systems, embedded in larger economic systems, are considered inextricably linked with other systems, such as communities (Berkes and Ross Citation2016; Fraser, Mabee, and Figge Citation2005) and ecological systems (Allen et al. Citation2014; Dorren et al. Citation2004). In line with this approach, organizational resilience must be viewed in a systemic context, deserving as such interdisciplinary academic attention and scrutiny. Returning to the example of an organization that experiences a disturbance due to external criticism (indicating therefore an existing societal concern over the organizational impact and/or processes), organizational resilience exhibited in that context should be carefully examined. In cases of organizational thriving despite criticisms, it is critical to investigate which strategies were used and to what extent did these strategies address the core of the criticism.

Resilience of SDOs and the case of ETSI

The most well-documented example of ETSI thriving despite criticism is the historical development of ETSI's IPR policy, which clearly demonstrates ETSI's organizational resilience (Pocknell and Djavaherian Citation2022). The development of ETSI's IPR policy has been described in the literature as controversial, encountering political opposition from the German Association for Protection of Intellectual Property and the European Commission (EC), who were openly expressing their concerns in the ‘90s (Alexandridis Citation2019). Subsequently, ETSI developed and adopted an IPR policy, which was, however, still criticized for vague definitions of essential patent holders' rights and obligations (Schmidt Citation2013), particularly with regards to its fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms and the essentiality of standards-essential patents (SEPs). ETSI's IPR policy remains as such a source of controversy, as evident from the abundance of FRAND related court cases (Mossoff Citation2023), and academic literature accumulating similar criticism to this day (Brismark et al. Citation2023; Carrier Citation2023; Contreras Citation2023; Karga Giritli Citation2023). ETSI's continued success and global influence despite these criticisms can therefore be understood as an indication of thriving, providing as such an important example of organizational resilience that warrants close academic attention and further motivates the empirical inquiry into ETSI's resilience strategies.

To understand this example, it is crucial to place it within its historical context. ETSI's IPR policy was drafted as a response to the regulatory pressures from the EU, which emerged as a reaction to the recognized potential for monopolization incompatible with antitrust legislation that ETSI's standardization activities were opening the space for (Pocknell and Djavaherian Citation2022). As transparently noted on ETSI's website (Dahmen-Lhuissier Citationn.d.), ETSI was founded in 1988 by the European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT) in response to proposals from the European Commission. In 1990, ETSI signed a joint co-operation agreement with CEN and CENELEC, two existing European Standards Organizations (ESOs). In 1990, ETSI gained the legal status of an ESOs, joining thereby CEN and CENELEC and completing the ESO triad that remains at present. As such, ETSI's organizational origin and evolution, as well as origin and evolution of ETSI's IPR policy, were historically tied with the European Commission.

Such examples of SDO embeddedness in regulatory networks underscore the importance of critically studying resilience of SDOs, considering that even technical telecommunication standardization, such as in the case of ETSI, is political in nature, due to its regulatory and policy goals and outcomes (Gamito Citation2020). This political nature is particularly evident when it comes to harmonized technical standards in the EU, as directed by The New Approach to Technical Harmonization and Standards (EC Citation1985), which through complex combination of soft and hard law instruments achieve increasingly strong binding effects (Colombo and Eliantonio Citation2017). The recent EU standardization strategy (EC Citation2022), revisiting the New Approach (EC Citation1985), reaffirms the reliance on harmonized standards that are often de facto binding. Moreover, even outside of the scope of harmonized standards, due to the interconnected and ubiquitous nature of the ICT industry, voluntary standards can attain a quasi-mandatory status by virtue of network effects (Werle and Iversen Citation2006), achieving thus far reaching impact.

Due to such rife influence of ETSI on thereto connected socio-ecological systems, the organizational practices that ensure its resilience deserve careful attention. Moreover, the proliferation of network technologies characterized by unparalleled speed of innovation sets ICT standardization apart because it requires a high degree of flexibility (Jayakar Citation1998). Having to respond to changes in such a fast paced market environment tests organizational resilience frequently, thereby making ETSI a prime case study to provide insight into resilience of SDOs.

Methodology

For the purpose of this study, 30 individuals who are currently in differing capacity involved in standard setting within ETSI were approached between November 2022 and May 2023. Out of 30 approached individuals, 16 accepted the interview, two declined, and 12 did not provide a definitive answer. Out of the 16 individuals who accepted the interview invitation, three were unable to participate due to (personal) scheduling reasons, and one interviewee did not consent to audio recording.Footnote1 Therefore, the empirical basis of this article is content analysis of the transcripts of audio recordings of 12 semi-structuredFootnote2 interviews. Although the sample of interviewees is not large, it is constructed with careful consideration to include interviewees with diverse background with regards to the capacity in which they participate in ETSI (staff or not, longevity of involvement), education (STEM, social science or both) and professional background (technical or governance).

Content analysis applied to the interviews was primarily deductive, based on author's (Stanojević Citation2023) empirical research into resilience strategies of SDOs in the goods manufacturing domain. Additionally, the conducted deductive analysis was supplemented with inductive analysis to ensure registering potential unique strategies that were not recorded in the previous research. The present case study of ETSI is a part of an ongoing grounded theory approach to resilience strategies of SDOs, consisting of three studies covering three broad areas of standardization: goods, telecommunications and finance. The first study was an inductive analysis of interviews with staff of SDOs in the area of goods standardization; the second, i.e. this study, is based on a combination of deductive and inductive content analysis of interviews conducted with ETSI staff, using predefined categories derived from the previous study; and finally, in the third (ongoing) study, data collected from individuals involved in finance standardization are analyzed using mixed methods, based on the findings of the previous two studies. As such, this grounded approach consists of three iterations of data analysis and/or collection, and covers three broad domains of standardization towards a generalizable taxonomy of resilience strategies in standardization.

The previous research differentiated 28 organizational resilience strategies organized in a 2 × 2 taxonomy with regards to locus of effort (external – internal) and anticipation of challenge (proactive – reactive). Building on these findings, the present research uses a mainly deductive approach to content analysis, by coding examples from the interviews according to 28 predefined categories divided into four clusters (proactive internal, proactive external, reactive internal and reactive external). Such deductive approach was supplemented with inductive content analysis to identify any strategies that may appear in addition to the 28 predefined strategies informed by previous research.

Findings

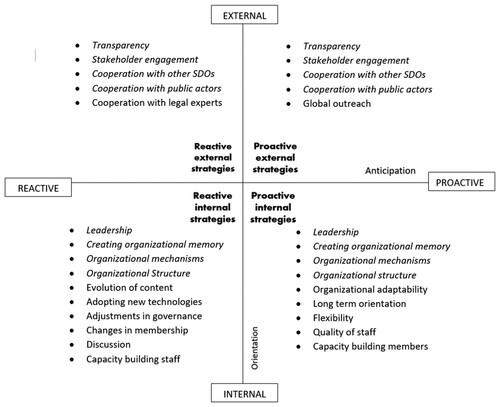

The findings reveal that ETSI's resilience strategies can indeed be sorted according to locus of effort and anticipation of the challenge into four categories (), greatly resembling the taxonomy of resilience strategies derived using data from SDOs in the area of goods standardization (Stanojević Citation2023). Deductive coding resulted in finding examples within ETSI for the vast majority of the 28 previously identified categories, except ETSI interviewees did not report the use of three previously identified strategies, namely greenwashing and lobbying as reactive external strategies, and analysis as a reactive internal strategy. On the other hand, ETSI interviewees reported the use of four additional strategies not mentioned by interviewees reporting on goods standardization, namely increasing transparency and cooperation with legal experts as a reactive external strategy, and the key role of leadership and flexibility as a proactive internal strategy. With these minor differences (which are nevertheless potentially interesting, as they raise more specific research questions for future research into resilience of SDOs), the case study of ETSI identified in total 29 resilience strategies, one more than the study of goods SDOs’ resilience strategies.

Figure 1. The taxonomy of resilience strategies used by ETSI.

Note: italic – strategies that appear both proactively and reactively.

As seen in , resilience strategies are divided into four categories according to locus of effort (internal or external to the organization) and anticipation of the challenge or disturbance (proactive or reactive relative to the disturbance). While sorting the strategies into external (10) and internal (19) was clear-cut, sorting them into proactive and reactive was relatively less straight-forward. For example, some strategies (italic in , e.g. transparency, leadership) were utilized proactively – i.e. continuously and preventatively; and reactively – i.e. in response to a disturbance or crisis. While this will be further addressed in the Discussion, here it suffices to note that temporal context, as reported by the interviewees, was the determining factor for coding strategies as reactive (15) or proactive (14), and literature was consulted where the data was inconclusive. Specifically, challenges and disturbances mentioned by the interviewees included receiving criticism from the EC about industry overrepresentation in ETSI; antitrust lawsuit filed by TruePosition Inc.Footnote3; the EC expressing concerns about ETSI's IPR policy; changes in the innovation and market landscape (e.g. AI, open source software), etc.

Discussion

The previous section presents an overview of the identified 29 strategies ( and ) and the antecedents (disturbances) that lead to the use of 15 identified reactive strategies. The discussion section reflects on the outcomes of these resilience strategies – in particular, how these strategies relate to organizational outcomes (thriving) and socio-ecological outcomes. Before discussing individual resilience strategies and their potential relationship with organizational outcomes in more detail, let us first consider the political nature of standardization, as an important notion for understanding the relationship between resilience strategies, organizational thriving and socio-ecological outcomes.

Table 1. The frequency of examples and interviewees per resilience strategy.

Table 2. Overview of ETSI's resilience strategies and examples.

Is standardization political?

According to one of the interviewees, standardization is, even in technical domains such as telecommunications, a deeply political process, particularly in terms of geopolitics and political economy. The same interviewee emphasizes that technology is not value-neutral, reflecting the insights of growing literature concerning the social and ethical implications of technological innovation (see for example Hare Citation2022; Miller Citation2021). Another interviewee reveals the political character of telecommunications by mentioning citizens’ health concerns regarding new infrastructure and the associated public concerns and resistance. This interviewee dismisses citizens’ health concerns as irrelevant, despite acknowledging their existence and extent. Therefore, inferring from the fact that none of the interviewees indicated public health concerns as a challenge for the organization, it seems that serious consideration of these concerns is absent from debates within ETSI. As such, the political nature of standardization provides a lens through which resilience of ETSI can be understood, particularly when analyzing what is considered a disturbance, and how certain resilience strategies lead to thriving in the particular political context ETSI operates within.

Public concerns, be it related to health implications of telecommunication standardization or the dominant influence of industry in ETSI's, ought to be taken seriously. The interviews indicate that despite both of these external criticisms, ETSI continues to thrive. However, while the criticism regarding the industry's influence, which came from the EC, was identified by interviewees as a disturbance and dealt with using several strategies (as outlined in the Findings section), health concerns, which came from the public, were not identified by the interviewees as a disturbance and no resilience strategies were reported in relation to it. Analyzing how interviewees perceive disturbances opens a window towards a broader definition of resilience strategies. Perhaps dismissal as a reaction to externalities not considered disturbances can also lead to resilience, and can also be used strategically to avoid or postpone addressing controversial issues. In the case of ETSI, it appears that criticism coming from the EC was perceived as a disturbance to an extent sufficient for ETSI to employ several resilience strategies, while criticism coming from citizens was more easily dismissed. Future research could look into the characteristics of external criticism that determine the use of dismissal as opposed to one of 15 identified reactive resilience strategies, as well as how the choice between dismissal and reactive strategies affects outcomes, i.e. the probability of thriving.

How does ETSI choose effective resilience strategies?

In response to EC criticizing the dominant role of the industry in ETSI, the use of several resilience strategies was reported, namely discussion, leadership, cooperation with public actors (i.e. EC), creating organizational memory, and increased transparency. Other disturbances that elicited a response consisting of several reactive resilience strategies also involved the EC, namely criticism of the IPR policy (EC Citation1992) and the new standardization strategy (EC Citation2022). However, when discussing ETSI's response to the new (EC Citation2022) standardization strategy, the interviewees reveal ETSI's confidence in its position and the ability to thrive despite criticism. One interviewee notes, in a critical tone, that the general attitude within ETSI towards the new standardization strategy questioning its legitimacy is one of denial. In line with this attitude, another interviewee compares the pressure EC (Citation2022) currently applies on ETSI to adapt to the new standardization strategy to other moments throughout history where EC criticized ETSI, and ETSI continued thriving. The interviewee concludes that the EC is not likely to take away ETSI's ESO status regardless of how well ETSI implements the required adjustments in governance. However, interviewees report that ETSI has staff appointed specifically to working on implementing the new standardization strategy and maintaining cooperation with the Commission in this particular context.

The literature reveals ETSI had at several points over time received criticism regarding insufficiently diverse stakeholder representation (Colombo and Eliantonio Citation2017; Kallestrup Citation2017; Werle and Iversen Citation2006), as problematized also by the Commission and SME associations (EC Citation2022) and several forthcoming contributions to this special issue (Bekkers and Lazaj Citation2024; Kanevskaia, Delimatsis, and Bijlmakers Citation2024; Delimatsis and Verghese Citation2024), which describe this as a legitimacy issue. Some of the interviewees acknowledge such external criticisms regarding stakeholder representation. However, interestingly, stakeholder engagement was not mentioned as a strategy used to respond to such criticism – rather, it was mentioned in response to innovation and market evolution. Furthermore, even when stakeholder engagement is mentioned as a strategy, several interviewees additionally mention a caveat, whereby although the membership is nominally open to any and every one, it does not come without a fee. Therefore, due to the resources needed for membership and travel costs, non-traditional stakeholders, such as SMEs (as specified in several interviews), can often not afford to participate in standard setting within ETSI.

While it has long been documented that SMEs are, due to their comparative disadvantage in resources and expertise, less likely to affect standardization at the EU level (Egan Citation1996), the current empirical data appears to show not much has changed. This informs the systems view on resilience – while the resilience strategies utilized do seem to achieve the resilience of ETSI itself, they are not necessarily beneficial with regards to related systems, as voiced in various accounts of concern over, for example, the participation of SMEs (EC, Citation2023). As such, the normative notion of organizational resilience should be carefully considered in the context of each particular organization and its relationship with socio-ecological systems.

These accounts substantiate the input legitimacy concerns directed at ETSI (Kallestrup Citation2017), pointing to considerations of economic barriers to participation, that differ between groups of stakeholders. They also provide an answer to the question posed in the introduction, namely to what extent do resilience strategies used address the core of the issue when SDOs are faced with external criticism for internal processes. It is evident from the case study of ETSI that, at least in some cases, the strategies used entail addressing the criticism superficially, pro forma – for example, by opening up membership to a variety of stakeholders – while in practice the participation of underrepresented stakeholders stays limited due to practical constrains, and standardization taking place within ETSI stays predominately focused on the interests of big industrial players. Considering the continued success and growth of ETSI indicated by the interviewees, it appears that superficially addressing the criticism can, at least in the long run, coexist with thriving. This possibility opens up fascinating avenues for new research that could link characteristics of external criticism (i.e. source; potential repercussions) with organizational responses (dismissal; pro forma reactive resilience strategies; resilience strategies that target the core of the criticism), and finally link these combinations to outcomes (survival; recovery; thriving). However, the data available for the current study does not allow modeling these pathways, as interviewees were not specifically asked to reflect on the outcomes of a particular strategy. Therefore, conclusions about outcomes of discussed strategies are based on the historical accounts of ETSI's functioning, and are as such correlational and tentative.

Multi-purpose strategies?

With regards to the taxonomy itself, some particularities of the anticipation dimensions ought to be considered. The above mentioned stakeholder engagement is reported both as a proactive and a reactive strategy. As the example of dual proactive and reactive application of stakeholder engagement goes to show, the lines between the categories can be blurred. Not only can certain strategies (i.e. strategies marked italic in ) generally be used both proactively and reactively – moreover, the concrete strategy that was used as a response to a certain crisis can at the same time proactively tackle an upcoming crisis. This is evident in the case of adjusting organizational mechanisms by setting up remote network testing, which was a strategy employed in response to practical difficulties of moving large pieces of equipment, but was reportedly proactive in providing the infrastructure for an upcoming crisis, when traveling was restricted due to lockdowns. This example, thus, represents both a reactive and proactive case of adjustments in mechanisms of standards development as a resilience strategy. In this example, the proactive effect of reactive strategies is emphasized by the interviewee, but such an extended effect of reactive strategies is likely more common.

A different case of overlap between proactive and reactive strategies are the strategies mentioned in relation to dealing with ETSI IPR policy. Namely, from the narratives of some interviewees it appears that ETSI approached drafting IPR policy proactively, which would imply the associated resilience strategies were proactive too, while other interviewees frame these occurrences reactively, in response to regulatory pressures. According to Pocknell and Djavaherian (Citation2022), however, IPR policy was drafted in response to the open letter issued by the European Commission in 1992 (EC Citation1992). Moreover, in this communication the Commission notes that other SDOs, such as ISO, IEC, CEN and CENELEC have already had IPR policies at the time, representing an external incentive. Therefore, the literature review helped to make sense of at times ambiguous or contradictory narratives in the interviews. In case of the IPR policy, based on the literature review, IPR related resilience strategies were classified as reactive for the purpose of content analysis.

Conclusion

The literature pertaining to ETSI's historical development, as reviewed in this article, had already indicated (although implicitly) that ETSI is a resilient and thriving organization. Building on that literature, this article explicitly recognizes and analyses the organizational resilience of ETSI's. The novel contribution of this article is twofold: first, this research provides a taxonomy of ETSI's resilience strategies, which corresponds to a great extent to the taxonomy of resilience strategies used by SDOs in the area of goods manufacturing (Stanojević Citation2023). Resilience strategies can be divided according to anticipation of the organizational challenge and locus of effort into four categories: proactive external, proactive internal, reactive external and reactive internal. In this particular case study, 29 strategies were identified (five proactive external, nine proactive internal, five reactive external and ten reactive internal). Although the specific strategies may vary on a case to case basis, the two-dimensional 2 × 2 taxonomy is expected to hold when applied to resilience strategies of other SDOs and organizations in general, constituting therefore a theoretical contribution to the broader field of management science.

Second, this case study provides further insight into the historical and current ETSI developments that have thus far not been assessed from the organizational and management science perspective (such as drafting of the IPR policy and ETSI's response to public criticism and concerns about its legitimacy). While the existing literature does provide legal analysis of such developments (Colombo and Eliantonio Citation2017; Eliantonio and Volpato Citation2024; Gamito Citation2020), this article offers a critical and empirically informed view through the lens of organizational resilience, substantiating the existing concerns around ETSI's legitimacy. It offers a perspective that includes interconnected socio-ecological systems within which organizations are embedded, the resilience of which, at least in some cases, may be a tradeoff to organizational resilience. As such, this article advances a holistic view of organizational resilience, the normative desirability of which depends on the dynamic interactions of the organization as a system with thereto related socio-ecological systems.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antonia Stanojević

Antonia Stanojević is an interdisciplinary social science researcher. Overall, her research analyses power dynamics at different levels (interpersonal, organizational, intergroup and transnational) and emphasizes the interconnectedness of these levels. Currently, she applies the described approach to governance of socio-technical change.

Notes

1 Although informative, this interview was omitted from the analysis due to absence of the transcript

2 The interview guide can be found in the Appendix, although the questions asked differed significantly on a case-to-case basis.

3 In this lawsuit, TruePosition alleged that Ericsson, Alcatel and Qualcomm essentially hijacked ETSI and conspired to include their technologies in the standards at the expense of competitors.

References

- Alexandridis, Stylianos. 2019. “ETSI: A Case Study in Standard Setting and Capture.” PhD diss., Queen Mary University of London.

- Allen, Craig R., David G. Angeler, Ahjond S. Garmestani, Lance H. Gunderson, and Crawford S. Holling. 2014. “Panarchy: Theory and Application.” Ecosystems 17 (4): 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9744-2.

- Annarelli, Alessandro, and Fabio Nonino. 2016. “Strategic and Operational Management of Organizational Resilience: Current State of Research and Future Directions.” Omega 62: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2015.08.004.

- Bekkers, Rudi, and Elona Lazaj. 2024. “Voting or Consensus? An Empirical Study of Decision-Making in the European Standards Body ETSI.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research (forthcoming).

- Berkes, Fikret, and Helen Ross. 2016. “Panarchy and Community Resilience: Sustainability Science and Policy Implications.” Environmental Science & Policy 61: 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.04.004.

- Brismark, Gustav, Mattia Fogliacco, Carter Eltzroth, Matteo Sabattini, and Richard Vary. 2023. “Overview Of SEPs, FRAND Licensing And Patent Pools.” FRAND Licensing and Patent Pools (January 30, 2023). les Nouvelles-Journal of the Licensing Executives Society 58 (1): 57–62.

- Carrier, Michael A. 2023. “Why Is FRAND Hard?” Utah Law Review 2023: 931.

- Colombo, Carlo, and Mariolina Eliantonio. 2017. “Harmonized Technical Standards as Part of EU law: Juridification with a Number of Unresolved Legitimacy Concerns?.” Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 24 (2): 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X17709753.

- Contreras, Jorge L. 2023. “A Research Agenda for Standards-Essential Patents.” Forthcoming in A Research Agenda for Patent Law (Enrico Bonadio & Noam Shemtov, eds., Edward Elgar, 2024), University of Utah College of Law Research Paper 531.

- Dahmen-Lhuissier, Sabine. n.d. “Our History,” ETSI, n.d. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.etsi.org/about/14-about/1468-our-history.

- Delimatsis, Panagiotis. 2023. The Evolution of Transnational Rule-Makers through Crises. Cambridge University Press.

- Delimatsis, Panagiotis, and Zuno Verghese. 2024. ““To Antipolis, My Sisters!”: ETSI as a forum of Contestation, Collaboration and Orchestration.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research (forthcoming).

- Dorren, Luuk K. A., Frédéric Berger, Anton C. Imeson, Bernhard Maier, and Freddy Rey. 2004. “Integrity, Stability and Management of Protection Forests in the European Alps.” Forest Ecology and Management 195 (1-2): 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.02.057.

- Egan, Michelle P. 1996. “Regulating European Markets: Mismatch, Reform and Agency.” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh.

- European Comission. 2023. “FIT FOR FUTURE Platform Opinion on the Functioning of European Standardisation Regulation.” https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/final_opinion_2023_4_european_standardisation.pdf.

- European Commission. 1985. “Completing the Internal Market. White Paper from the Commission to the European Council,” COM(85)310.

- European Commission. 1992. “COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS AND STANDARDIZATION.” COM(92)445.

- European Commission. 2022. “Communication on an EU Strategy on Standardisation - Setting Global Standards in Support of a Resilient, Green and Digital EU Single Market.” COM(2022)31.

- European Commission. 2022. “REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL on the Implementation of the Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012 from 2016 to 2020.”

- Fraser, Evan D. G., Warren Mabee, and Frank Figge. 2005. “A Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability of Food Systems to Future Shocks.” Futures 37 (6): 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2004.10.011.

- Gamito, Marta Cantero. 2020. “The Legitimacy of Standardisation as a Regulatory Technique in Telecommunications.” In The Legitimacy of Standardisation as a Regulatory Technique, edited by Mariolina Eliantonio, and Caroline Cauffman, 222–242. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Gunderson, Lance H., and Crawford Stanley Holling, eds. 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Hare, Stephanie. 2022. Technology is not Neutral: A Short Guide to Technology Ethics. London: London Publishing Partnership.

- Holling, Crawford Stanley. 2001. “Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems.” Ecosystems 4 (5): 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5.

- Jayakar, Krishna. 1998. “Globalization and the Legitimacy of International Telecommunications Standard-Setting Organizations.” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 5 (2): 711–738.

- Kallestrup, Morten. 2017. “Stakeholder Participation in European Standardization: A Mapping and an Assessment of Three Categories of Regulation.” Legal Issues of Economic Integration 44 (4): 381–393.

- Kanevskaia, Olia, Panagiotis Delimatsis, and Stephanie Bijlmakers. 2024. “The European Telecommunication Standards Institute (ETSI): In Search for Legitimacy and Resilience Of European Standardisation.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research (forthcoming).

- Karga Giritli, Nazli Cansin. 2023. “Improving the SEP Licensing Framework by Revising SSOs’ IPR Policies.” PhD diss., University of Glasgow.

- Ledesma, Janet. 2014. “Conceptual Frameworks and Research Models on Resilience in Leadership.” Sage Open 4 (3): 1–8.

- Mafabi, Samuel, John C. Munene, and Augustine Ahiauzu. 2015. “Creative Climate and Organisational Resilience: The Mediating Role of Innovation.” International Journal of Organizational Analysis 23 (4): 564–587. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-07-2012-0596.

- Miller, Boaz. 2021. ““Is Technology Value-Neutral?” Science, Technology, & Human Values 46 (1): 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919900965.

- Mossoff, Adam. 2023. “Patent Injunctions and FRAND Commitment: A Case Study in the ETSI Intellectual Property Rights Policy.” Berkeley Tech. LJ 38: 487–513.

- Patriarca, Riccardo, Johan Bergström, Giulio Di Gravio, and Francesco Costantino. 2018. “Resilience Engineering: Current Status of the Research and Future Challenges.” Safety Science 102: 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.10.005.

- Pocknell, Robert, and David Djavaherian. 2022. “The History of the ETSI IPR Policy: Using the Historical Record to Inform Application of the ETSI FRAND Obligation.” Rutgers UL Rev 75: 977.

- Schmidt, Otto. 2013. “Updates.” Computer Law Review International 14 (6 ): 188–191.

- Stanojević, Antonia. 2023. “How Do They Do it? An Empirically Based Taxonomy of Standards Development Organizations’ Resilience Strategies.” TILEC discussion paper No. 2024-03. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4662341.

- Vogus, Timothy J., and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. 2007. “Organizational Resilience: Towards a Theory and Research Agenda.” In 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 3418–3422. Montreal: IEEE.

- Volpato, Annalisa, and Mariolina Eliantonio. 2024. “The participation of civil society in ETSI from the perspective of throughput legitimacy.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 1–17.

- Von Bertalanffy, Ludwig. 1972. “The History and Status of General Systems Theory.” Academy of Management Journal 15 (4): 407–426. https://doi.org/10.2307/255139.

- Weick, Karl E., and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. 2015. Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Werle, Raymund, and Eric J. Iversen. 2006. ““Promoting Legitimacy in Technical Standardization.” Science Technology & Innovation Studies 2 (1): 19–39.

- Williams, Trenton A., Daniel A. Gruber, Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, Dean A. Shepherd, and Eric Yanfei Zhao. 2017. “Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams.” Academy of Management Annals 11 (2): 733–769. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0134.

- Woods, David. 2006. “Engineering Organizational Resilience to Enhance Safety: A Progress Report on the Emerging Field of Resilience Engineering.” In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 50, 2237–2241. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Woods, David. 2015. “Four Concepts for Resilience and the Implications for the Future of Resilience Engineering.” Reliability Engineering & System Safety 141: 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2015.03.018.

- Woods, David, Nancy Leveson, and Erik Hollnagel. 2017. Resilience Engineering : Concepts and Precepts. Boca Raton: CRC Press.