ABSTRACT

How do human rights groups prevent the normalization of practices they find troubling? Existing international relations research provides insights into how states resist the new norms human rights activists introduce into the global arena. But it tells us less about how governments themselves promote norms and how activists push back against this advocacy. This article explores this issue by examining the interplay between Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the United States around the emerging norm of targeted killing. It argues that Bin Laden’s death opened a window of opportunity for the potential emergence of a targeted killing norm, with the United States as its norm advocate. To prevent its emergence, HRW deployed some of the same strategies states have used to suppress the emergence of norms they dislike. In illustrating these dynamics, this article helps us better understand why some norms rise, why some fall, and why they might change over time.

On May 3, 2011, the United States killed Osama bin Laden. His death was not only an important symbolic moment in the U.S. war against Al-Qaeda, but his death also had the potential to significantly impact the normative structure of international order. Prior to Bin Laden’s death, global sentiment generally viewed targeted killings as violating states’ normative and material interests supported by foundational international norms, as discussed in the other contributions to this special issue. Yet as Jose (Citation2017) argues, Bin Laden’s death was a watershed moment which helped emerge a targeted killing norm, one which would in new ways curtail protection and sovereignty norms that form the bedrock of international order. This article explores how state and non-state actors responded to this emerging norm’s effect on the global normative structure. Specifically, it offers an in-depth examination of the efforts of Human Rights Watch (HRW), a gatekeeper in the human rights realm (Carpenter, Citation2011), to suppress the targeted killing norm entirely and, later, to suppress an unrestrained version of the norm.

As such, this article expands our limited understanding of norm suppression. While norms scholars have devoted substantial effort elucidating the processes of norm emergence (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013; Finnemore & Sikkink, Citation1998; Florini, Citation1996), we know considerably less about efforts to resist norm emergence. In shedding light on norm suppression, this article also helps us better understand the multiplicity and fluidity of the roles normative actors play as they engage each other in determining the global rules of the game. In particular, it reveals how NGOs do not only promote new ideas but can also resist them, as states might. In other words, this article sheds more light on how NGOs attempt to push would-be norm entrepreneurs to maintain the extant global normative structure rather than change it. Furthermore, this discussion illustrates how norm suppressors attempt to minimize the potentially destabilizing effects an emerging norm may have if it collides with deeply entrenched global norms.

The article proceeds in the following manner. It begins by discussing Finnemore and Sikkink’s (Citation1998) norm life cycle model and the state of knowledge regarding norms. It then moves into an exploration of norm entrepreneurship and norm suppression with an emphasis on the latter. The case study follows next. In it, Senn and Troy’s (Citation2017) definition of targeted killing in this issue is employed: Targeted killing is the intentional use of lethal force or substances against a prominent or culpable person or a small group of persons not in the physical custody of the perpetrator. The targeted killing case study’s main players include the United States as norm entrepreneur, particularly under President Obama, and HRW as the norm suppressor. While the United States under the Bush Administration embraced targeted killings shortly after the September 11, 2001, attacks, it greatly escalated the use of this tactic under the Obama administration. Additionally, while HRW is part of the anti-targeted killing network (Bob, Citation2017; Brunstetter & Jimenez-Bacardi, Citation2015), a specific focus on it helps us understand norm suppression as it long resisted this practice’s normalization. Furthermore, it always aimed to influence the United States (Rodio & Schmitz, Citation2010). This is particularly the case here, not only because the United States is the norm entrepreneur, but also because of its concern of how U.S. behavior may influence other states:

US policy and practice is also setting a very dangerous precedent for other countries. Could China declare an ethnic Uighur activist living in New York a “terrorist” and, if the US were unwilling to extradite that person, lawfully order a lethal strike on US soil? Could Russia lawfully poison to death someone living in London whom they claim is linked to Chechen terrorists? (Mepham, Citation2012)

Second, as a human security network hub, HRW wields enormous productive power to shape whether and how other network members engage in norm suppression, and its adoption of an issue conveys its gravity to nonmembers. As Carpenter (Citation2011) contends, being a network hub

translates into disproportionate influence over the agenda in those networks, since actors both inside and outside the network view hubs’ organizational agendas as proxies for the network agenda, creating contagion effects within networks when hubs adopt new issues, and raising the likelihood that such claims will be taken seriously by external audiences including the media and policymakers. (pp. 73–74)

Overview of the study of norms and their life cycle

As mentioned above, this article’s primary focus is twofold. First, it examines how HRW attempted to completely block U.S. efforts to modify intersubjective agreement on permissible uses of lethal force. Unsuccessful with this suppression effort, HRW then strove to place limits on when and how targeted killings can be conducted. In order to better understand these norm suppression activities, a brief discussion of Finnemore and Sikkink’s (Citation1998) well-known model follows.

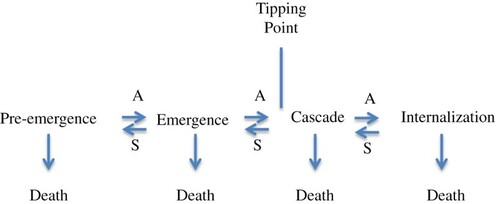

According to this model, the norm life cycle contains three phases: norm emergence, norm cascade, and norm internalization (). Because this article takes the position that a targeted killing norm has not yet emerged, its discussion focuses on the cycle’s early stages. During the initial stage of norm emergence, a practice’s advocates, or norm entrepreneurs, attempt to persuade other actors to adopt the norm. After all, it may well be that the new practice violates an existing norm. Or, actors may have a vested interest in the status quo. In other words, entrepreneurs may have to contend with norm suppressors trying to foil norm emergence. Thus, in order for a practice to progress through the norm life cycle, it is vital that norm entrepreneurs make a convincing case for the practice’s appropriateness and fit within the existing normative environment.

Figure 1. Norm life cycle. Source: Finnemore and Sikkink (Citation1998, p. 896).

Since Finnemore and Sikkink introduced the norm life cycle, a number of scholars have modified and refined this exemplary model. For instance, second-wave scholars and scholars examining compliance with external norms have moved away from the static, “norms as things” perspective espoused by their peers to embrace a “norms as processes” approach (Krook & True, Citation2012). While both approaches explain change in global political behavior, in the former, the focus is on the dynamics of new rules adoption. It focuses less on whether and how a particular norm’s content itself changes as it journeys through the life cycle, often assuming it remains fixed once a norm entrepreneur adopts it. For a norms-as-processes approach, changes in normative content are an important issue for inquiry. Rather than viewing that content as stable, it explores its fluidity and actors’ agency in challenging a norm’s prescriptions and parameters (Wiener, Citation2004). Each stage of the norm life cycle is rife with internal challenges, not just the norm emergence phase. Thus, changes in content can occur within even deeply internalized, well-entrenched norms (Liese, Citation2009). This article employs the norms-as-processes approach.

Additionally, scholars have added stages to the norm life cycle. These include norm death (McKeown, Citation2009) and, most relevant to the current discussion, the pre-emergence stage (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013). In this stage, “there are no shared assessments about the universal applicability of a practice for actors within a given identity” (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013, p. 6). In incorporating this stage into the life cycle, we are able to grasp the very early moments of a potential norm’s life. A practice then enters the norm emergence phase when it acquires supporters apart from its norm entrepreneurs.

Furthermore, recent work has expanded scholarly attention beyond the predominant “good” norm bias in norms research. Finnemore and Sikkink (Citation1998) employ a neutral definition of norms: Norms are “standard[s] of appropriate behavior for actors with a given identity” (p. 891). Norms exist if some community views their content as legitimate. Finnemore and Sikkink (Citation1998, p. 892) acknowledge this can include such practices as genocide and slavery. Yet, the overwhelming focus in the extant norms literature is on progressive norms, such as human rights norms or norms constraining state behavior (Jose, Citation2017). A growing body of work examines norms which enable states to use violence or which may violate human rights (Heller & Kahl, Citation2013; O’Driscoll, Citation2008). This article’s focus on targeted killing puts it into this camp.

Norms scholars have also paid increasingly more attention to the entrepreneurship of state actors. Early norms work generally conceived of norm entrepreneurs as individuals, nongovernmental organizations, and international organizations. Yet, states can be norm entrepreneurs as well. As Wunderlich (Citation2013) explains, “[o]nly in the last decade has research shifted its attention to states as norm entrepreneurs; prior to that, states were predominately depicted as norm receivers” (p. 33, emphasis in original). And this research reveals that states can be effective entrepreneurs, especially in the realm of state security given their relative expertise (Heller, Kahl, & Pisoiu, Citation2012). As is discussed below, in the case of an emerging targeted killing norm, the United States played an important role in laying out a case for why and how targeted killings could be an appropriate way to use lethal force in armed conflicts. In other words, it pushed the international community to alter the global normative structure regulating when and where states can kill.

Relatedly, more recent work has examined human rights organizations, such as HRW, as norm suppressors. As mentioned above, the norm life cycle model traditionally conceptualized these entities as norm entrepreneurs attempting to convince states to adopt their pet norm. In this model, sometimes states resisted these advocacy efforts. Yet, newer research has shown that non-state and state actors can play multiple roles in the norms story (Sanders, Citation2016). Which role they take can vary, depending on such factors as the issue itself, context, and timing, among others (Scott & Bloomfield, Citation2017, p. 236). In fact, the extant research has insufficiently focused on norm suppression more generally. It has expended more energy explaining what accounts for successful norm entrepreneurship and less on resistance to norm entrepreneurship (Bloomfield, Citation2015; Bloomfield & Scott, Citation2017; Sanders, Citation2016).

A modified depiction reflecting these advances might look like this, with norm entrepreneurship (A) by state and non-state actors enabling a practice’s progress and norm suppression (S) by state and non-state actors contributing to its regress and/or death. This advocacy and suppression together comprise the contestation that occurs in each stage of the norm life cycle, potentially altering normative content ().

How actors encourage and suppress norm emergence

Norms possess intersubjective agreement over their existence and content. Intersubjective agreement connotes a shared understanding of desirable and acceptable behavior (Kratochwil & Ruggie, Citation1986). The crucial point behind generating intersubjective agreement is to get actors to accept similar conceptions of what the logic of appropriateness requires in a given situation. The processes of norm entrepreneurship and norm suppression also center on intersubjective agreement. Norm suppressors focus on maintaining intersubjective agreement on the status quo; norm entrepreneurs seek to change it to enable new ideas to emerge.

Norm contestation captures this clash between norm entrepreneurs trying to change intersubjective agreement and norm suppressors trying to preserve it. While contestation over what is considered appropriate behavior occurs during every stage of the norm life cycle, its early stages are particularly rife with contestation since intersubjective agreement has yet to form or is unstable (Badescu & Weiss, Citation2010). It is during these stages that actors begin to determine a potential norm’s content and whether and how it fits in the existing normative infrastructure. These issues constitute different kinds of contestation: internal versus external contestation and applicatory versus justificatory contestation. Internal contestation “involves the consensus-finding process related to a potential new norm’s meaning” (Jose, Citation2017, p. 6). It can ultimately produce three types of changes which cumulatively improve a practice’s chances of solidifying intersubjective agreement, helping a practice emerge as a norm (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013, p. 5). One type of change involves identifying the material goals the norm can help achieve. This change speaks to the logic of consequences, rational analyses of the costs and benefits produced by specific acts (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013). The second type of change appeals to actors’ normative sensibilities. It aims to produce positive assessments of the norm’s content and employs the logic of appropriateness, ethical assessments of particular acts based on identity and other ideational factors (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013). A third type of change outlines what would be considered norm compliance by detailing what appropriate behavior looks like (Ben-Josef Hirsch, Citation2013).

External contestation deals with discussions about how well a new norm would fit with the extant normative environment (Florini, Citation1996). Norms do not arise in a vacuum. Potential norms have to compete with myriad other norms for attention and their existence. The likelihood a potential norm survives external contestation increases if it contains the following three traits: It achieves prominence; it coheres with existing norms; and its existence is necessitated by significant environmental changes (Florini, Citation1996).

The processes of internal and external contestation may also spur other types of contestation, namely, applicatory and justificatory contestation. Applicatory contestation is “contestation [which] regularly provokes specifications with regard to the type of situation to which a norm applies and how it needs to be applied” (Deitelhoff & Zimmerman, Citation2013, p. 5). During applicatory contestation, actors try to reach consensus on the scenarios in which the norm-associated behavior may be permitted and how it should be conducted. Because the focus is on clarifying when the norm is triggered, rather than challenging the need for its existence (as is the case with justificatory contestation), Deithelhoff and Zimmerman argue that applicatory contestation can effectively strengthen the norm. This type of contestation may occur during the processes of internal contestation as actors debate what is considered norm compliance. Recent heated discussions about whether Russia engaged in a permissible humanitarian intervention in Crimea serve as an example of applicatory contestation. Justificatory contestation entails deliberations on whether the norm should exist at all and why actors should follow the norm (Deitelhoff & Zimmerman, Citation2013, p. 5) and could thus ultimately weaken the norm. Global deliberations on whether norms permitting the use of fully autonomous weapons systems should emerge exemplify this type of contestation.

If norm entrepreneurs can consolidate support for their practice during these contestation processes, the practice solidifies its status as a norm. Norm suppressors will try to prevent this outcome by undermining activist efforts and shoring up support for established norms which may clash with the new norm. If successful, the new norm will fail to fully emerge or may emerge in a modified form.

Promoting new norms

The success and failure of both norm advocacy and norm suppression rest on a number of factors. These include the power of the actors involved, the context in which norm advocacy and norm suppression occur, and the frames they employ. These factors affect how contestation plays out. Contestation erupts when norm entrepreneurs kick off the norm life cycle with their advocacy. One of the ultimate purposes of this norm entrepreneurship is to generate intersubjective agreement regarding the new practice. As noted above, the presence of preliminary intersubjective agreement enables a practice to advance from the pre-emergence phase of the norm life cycle to its emergence phase.

A norm entrepreneur’s success in acquiring intersubjective agreement for his or her norm partially rests on effective framing. Framing is the act of “call[ing] attention to issues or even ‘creat[ing]’ issues by using language that names, interprets, and dramatizes them” (Finnemore & Sikkink, Citation1998, p. 897) and is important because it “enable[s] the [entrepreneur’s audience] to consider new kinds of appropriate behavior which differ from those firmly established” (Jose, Citation2017, p. 4; Risse & Sikkink, Citation1999). They comprise the communicative trail which helps us observe norms. Norm entrepreneurs possess a variety of tools to assist them in developing persuasive frames, including emotions, symbols, and logical arguments (Risse & Sikkink, Citation1999). If effective, these tools can enable norm entrepreneurs to generate shared acceptance of their practice’s appropriateness in a given situation.

Suppressing norms

Norm entrepreneurs are not the only actors relying on frames to advance their position. Those looking to prevent a practice’s emergence as a norm rely on them as well (Bob, Citation2017). Norm suppressors’ goal for internal and external contestation is to create intersubjective agreement against the new practice and undermine any shared agreement about its appropriateness. Furthermore, when a new norm threatens an established one, the older norm’s supporters will attempt to reestablish and strengthen allegiances to it (Symons & Altman, Citation2015, p. 68). They aim to dispute norm entrepreneurs’ claims of the new norm’s material and normative benefits and its fit with existing norms. And if they cannot completely prevent norm emergence, norm suppressors will try to ensure a modified version of the norm emerges, one which more closely aligns with established norms.

Norm blockers possess a number of tools to engage in norm suppression and defend the normative status quo. Bloomfield (Citation2015) differentiates between two different toolkits, strategic resistance and tactical resistance: “‘tactical’ is more suggestive of specific moves or actions in discrete institutional contexts while ‘strategy’ suggests the overall pattern and purpose that these more-discrete moves or actions are directed towards” (p. 13). Because tactical resistance tools are typically deployed in institutional settings inaccessible to HRW (such as the UN Security Council where a norm resister might exercise a veto), this article focuses on its strategic resistance.

Bloomfield (Citation2015) places strategic resistance tools into two categories. One category comprises defending the status quo by rejecting entrepreneurs’ claims that it leads to “morally problematic outcomes” (p. 14). Often, this deals with conflicts over whether the global environment has changed enough to necessitate new norms or modification of old norms. Another category of suppressive tools includes those that undermine the potential new norm (Bloomfield, Citation2015). Here, norm suppressors can question the merits of the new norm, whether it can coexist harmoniously with pre-existing norms, or even cast doubts on the motivations of the norm entrepreneurs.

Within these categories, the specific actions norm suppressors take manifest in a variety of forms. They may stall and muddle advocacy efforts, as was the case with conservative opponents of women’s rights coalitions (Chappell, Citation2006). They can also engage in public campaigning, lobbying, and strategic litigation to block norms. Supporters of the torture ban utilized all these tools to stop efforts by the United States to promote a new torture norm or modify existing prohibitions against torture (Sanders, Citation2016). HRW is particularly adept at “naming and shaming” (Vennesson & Rajkovic, Citation2012). Resisters can also band together to block advocacy efforts by more powerful players as Brazil and its partners did when trying to suppress the emergence of development norms promoted by developed countries (Abdenur, Citation2014).

The success of these suppression activities also relies on effective framing. According to Tocci and Manners (Citation2008, p. 326), frames employed by a powerful actor are particularly resonant. Power does not have to be exclusively grounded in material assets. Actors with significant amounts of productive power, power which “concerns discourse, the social processes and the systems of knowledge through which meaning is produced, fixed, lived, experienced, and transformed” (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005, p. 55), can also meaningfully influence a norm’s emergence or suppression. Sources of productive power include being a network hub and possessing significant amounts of symbolic capital or knowledge (Senn & Elhardt, Citation2014). An organization like HRW, which as a network hub possessing a long-standing reputation of credible human rights expertise, arguably wields a great deal of productive power within the realm of human rights. Consequently, it could effectively counter the norm advocacy of a powerful state like the United States, or, at the very least, ensure that its norm emerges in modified form.

The temporal context is also as important for norm suppression activities as it is for norm entrepreneurship. For norm emergence, specific events can serve as windows of opportunities, “salient events [which] upset the existing international order, [and] which may render normative commitments obsolete and pave the way for the establishment of new or the remodeling of existing norms” (Wunderlich, Citation2013, p. 30). During these windows of opportunity, a particular audience is more receptive to changing its intersubjective agreement about what is considered appropriate behavior. As the case study illustrates, for HRW, the strike on a wedding procession in Yemen, allegedly killing many civilians, served as a focusing event to secure intersubjective agreement on the emergence of a circumscribed targeted killing norm. Thus, normative change is not only possible due to structural factors, but also by norm entrepreneurs’ and norm suppressors’ exercise of agency (Bloomfield, Citation2015).

What some of the burgeoning literature on norm suppression (Bob, Citation2017) reveal is that norm resistors, whether they are states or non-state actors, act quite similarly, especially if they are defending long-standing norms. State and non-state norm suppressors rely on effective framing to persuade their audience of their position’s merits. They also exploit windows of opportunity to galvanize support, whether it be to embrace a new norm, to reject it, or to restrict it. This action plan bears striking similarities to that employed by both state and non-state norm entrepreneurs, as captured in Bob’s (Citation2017) typology of tactics deployed during these normative “conflicts.”

The case of targeted killing as an illustration of norm suppression

United States as a norm entrepreneur before Bin Laden’s death

Targeted killings are not ipso facto illegal under international humanitarian law (IHL), the body of law which regulates armed conflict. They can be legally conducted during armed conflict under particular circumstances, as Senn and Troy’s (Citation2017) definition of targeted killings suggests. And they are not necessarily a new phenomenon as evidenced by the long history of assassinations (Thomas, Citation2000). Yet, until Bin Laden’s death, intersubjective agreement supported a well-established assassination taboo, both outside of and during armed conflict. As Thomas notes (Citation2000), “[e]ven the lawful targeting of leaders during wartime, which is not properly considered assassination at all, has been rare because of the strength of the norm against assassination itself” (p. 114). The assassination taboo’s existence is one source of the controversy over U.S. and Israeli targeted killings prior to Bin Laden’s death. This is because the legal arguments these states made required the global community to accept modifications to deeply entrenched legal concepts (as discussed below). This is the reason this article classifies targeted killing as a new, emerging norm: The acceptance of Laden’s death seemed to signal an acceptance of what was once forbidden.

Perhaps due to the departures from dominant understandings of IHL needed to argue for their legality, the United States initially denied it conducted targeted killings, refused to comment on them (CNN Wire Staff, Citation2010), or let other states claim responsibility for them (see Senn & Troy, Citation2017). However, HRW and others exerted enormous pressure on the United States to admit it engaged in targeted killings and to provide explanations for how these deaths did not violate existing interpretations of IHL rules. In doing so, it was pushing the United States to maintain prevailing IHL understandings. For instance, in a 2010 letter to President Obama, HRW stated, “We write to ask that your administration provide greater clarity about its legal rationale for targeted killings, including the use of Unmanned Combat Aircraft Systems (drones), and the procedural safeguards it is taking to minimize harm to civilians” (Roth, Citation2010).

Eventually, the United States found it difficult to remain silent and acknowledged its targeted killing operations, illustrating some of the effects of the productive power held by actors like HRW. In doing so, the United States also explained how the practice complied with IHL (see also Senn & Troy, Citation2017). It argued that these strikes adhered to IHL’s obligations to engage in militarily necessary and proportionate attacks which distinguished between civilians and belligerents. In fact, it argued that the advantages of targeted killings lay in the reduced collateral damage they caused compared to other forms of lethal force. For example, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director Leon Panetta said in 2009, “[Drone] operations have been very effective because they have been very precise in terms of the targeting and it involved a minimum of collateral damage” (as cited in Shami, Citation2009). Harold Koh, the State Department’s legal advisor at the time of Bin Laden’s death, declared in 2010, “targeting particular individuals serves to narrow the focus when force is employed and to avoid broader harm to civilians and civilian objects” (Koh, Citation2010). Yet by doing so, the United States rhetorically entrapped itself: It “become entrapped by [its] arguments and obliged to behave as if [it] had taken them seriously” (Schimmelfennig, Citation2001, p. 65), opening it up for HRW’s attacks when civilians died during its targeted killing operations.

Invoking IHL underscored another important element of the United States’ justifications for the permissibility of its targeted killings: that its actions should fall within the realm of armed conflict rather than a law enforcement paradigm which contained more stringent laws regarding the use of lethal force. For instance, Koh said in Citation2010, “as a matter of international law, the United States is in an armed conflict with Al-Qaeda, as well as the Taliban and associated forces, in response to the horrific 9/11 attacks … ” (Koh, Citation2011). Koh claimed this war with Al-Qaeda differed significantly from other, more traditional wars: “this is a conflict with an organized terrorist enemy that does not have conventional forces, but that plans and executes its attacks against us and our allies while hiding among civilian populations” (Koh, Citation2010).

These two lines of argumentation, that its war with Al-Qaeda is unique and that its targeted killings complied with the fundamental purposes of IHL, formed the foundation for this norm entrepreneur’s claim for the norm’s acceptability. As such, the United States tried to shape internal and external contestation by utilizing frames that incorporated both the logic of appropriateness and the logic of consequences, and which attempted to convince the international community that targeted killings do not necessarily clash with existing norms. In doing so, it hoped to push global opinion toward accepting a targeted killing norm. And it did so not by challenging these IHL concepts’ necessity (justificatory contestation), but by claiming they needed to be reinterpreted to reflect the new kind of war it was waging against Al-Qaeda (applicatory contestation). As Beth Van Schaack (Citation2012), the Obama Administration’s former Deputy to U.S. Ambassador-At-Large for War Crimes Issues in the State Department’s Office of Global Criminal Justice claims, “the necessary arguments often do not enjoy textual support in the relevant treaties or reflect consistent state practice or opinio juris. Nor are there authoritative judicial pronouncements that provide validation. … ” (p. 3). Yet, as the following section shows, HRW pushed back. And because of HRW’s lengthy commitment to norm suppression, we can observe the various options it pursued.

Norm suppression prior to Bin Laden’s killing

As alluded to above, prior to Bin Laden’s death, there was strong global opposition to targeted killings:

[t]argeted killing … has raised profound anxieties in legal, policy, and advocacy communities in the United States and abroad, including among UN officials and special rapporteurs, highranking diplomats and lawyers of foreign and defense ministries of important states and allies, civil liberties and human rights advocacy groups … , and important commentators in academic international law and the press and media. (Anderson, Citation2011, p. 1; see also Bob, Citation2017, p. 76)

Recently, a number of legal objections have been raised against U.S. targeting practices … some have suggested that the very act of targeting a particular leader of an enemy force in an armed conflict must violate the laws of war … some have [also] argued that the use of lethal force against specific individuals fails to provide adequate process and thus constitutes unlawful extrajudicial killing … . (Koh, Citation2010)

HRW also questioned the U.S. claim that targeted killings, especially those conducted with drones, could minimize collateral damage compared to other methods of lethal force. In 2009, Marc Garlasco, a former senior military expert with HRW, told the New York Times that, regarding CIA targeted killings in Pakistan, “When you’re operating under very short time frames, like the C.I.A. is in Pakistan, you are exponentially increasing the risk of killing noncombatants” (as cited in Schmitt & Drew, Citation2009). Additionally, in its 2010 letter, HRW asserted,

The US government … has not explained how it designates targets as militants or measures proportionality in areas such as northwest Pakistan, where the CIA has reportedly conducted more than 120 drone strikes that have killed more than 800 people, including an unknown number of civilians. (Roth, Citation2010)

Norm suppression after Bin Laden’s death

As mentioned above, Bin Laden’s death served as a window of opportunity for the United States to further advance its case for the acceptance of targeted killings (Bob, Citation2017; Jose, Citation2017). The United States used similar frames in arguing that his death was justified as it did with prior targeted killings. It claimed his death occurred during an armed conflict and conformed with IHL’s obligations for discriminate and militarily necessary uses of lethal force. Thus, it did not offer substantively different arguments for the legality of this targeted killing compared to prior ones. What did change were the reactions to these frames. Prior to Bin Laden’s death, many members of the global community voiced their opposition to targeted killings. Yet, upon news of his death, immediate global reactions could be characterized as jubilant or silent, despite the fact that the legality of his death could be easily questioned (Jose, Citation2017).

Regarding HRW, Executive Director Kenneth Roth released the following short statement just after the United States announced it killed Bin Laden:

At a time when citizens around the world have engaged in peaceful demonstrations in the name of freedom and democracy, Bin Laden’s death is a reminder of the thousands of innocents who suffer when terrorist groups seek political change through brutal means. (HRW, Citation2011a)

Some media reports have erroneously suggested that Human Rights Watch has condemned the killing of Osama bin Laden. Human Rights Watch has said that we do not have enough information about the killing to draw conclusions about whether it was lawful or not. Human Rights Watch calls on the US government to provide that information.

Bin Laden publicly took responsibility for several mass killings of civilians. The inability to bring Bin Laden to trial for crimes against humanity means that an important avenue for justice has been lost, but that is quite different from determining whether the killing was legal … The US government should provide all the relevant facts about Osama bin Laden’s death to clarify whether it was justified under international law. (HRW, Citation2011b)

Personally, I am very much relieved by the news that justice has been done to such a mastermind of international terrorism. I would like to commend the work and the determined and principled commitment of many people in the world who have been struggling to eradicate international terrorism. (UN Department of Public Information, Citation2011)

Since the death of Osama Bin Laden, this trend [of killing rather than capturing terrorism suspects] has been strongly influencing international responses to terrorism as well as that in the US … This trend towards killing instead of capturing following the death of Bin Laden is seen in the targeted killings of Anwar al-Awlaqi, Samir Khan, Ibrahim al-Bana and Al Abdul-Rahman al-Awlaqi.

Subsequent efforts to regulate the practice, rather than ban it, suggest the practice has now progressed from the pre-emergence phase into the emergence phase (Jose, Citation2017).

Despite its seemingly forward normative journey, HRW did not abandon its efforts to rein in the practice so that a more limited version of the norm might emerge. As mentioned above, because of the life cycle’s dynamism, normative content might undergo substantial modification as the norm proceeds through the cycle’s various stages. In fact, it appears that HRW adopted a more active and assertive approach to shaping the norm after Bin Laden’s death than before, given the increase and more adversarial tone in its advocacy activities. It appears that, like many other members of the international community, HRW accepted that a targeted killing norm may emerge. As such, HRW has now focused its suppression efforts on preventing the rise of a norm which offers states great latitude in killing individuals, the version of the norm promoted by the United States. Accepting that a targeted killing norm may emerge, HRW has concentrated on ensuring it requires transparency and accountability and prioritizes civilians. In doing so, it aims to preserve the right to life and IHL norms restricting belligerents’ abilities to kill their opponents, as well as sovereignty norms. Its hope was to maintain as much of the status quo as possible in the face of this norm’s emergence. As the following discussion illustrates, Bloomfield’s (Citation2015) norm blocking categories also aptly apply to HRW’s attempts to limit what a new targeted killing norm might enable.

One example of HRW’s effort to suppress an unrestrained targeted killing norm is its attempt to end the CIA’s participation. It has done so by naming and shaming the United States. In a letter directed to President Obama in the year of Bin Laden’s death, HRW charged, “[b]ecause the US government routinely neither confirms nor denies the CIA’s well-known participation in targeted killings in northern Pakistan and elsewhere, there is no transparency in its operations” (Roth, Citation2011). It went on to demand:

so long as the US government cannot demonstrate a readiness to hold the CIA to international legal requirements for accountability and redress, the use of drones in targeted killings should be exclusively within the command responsibility of the US armed forces. (Roth, Citation2011)

Given the very close security and intelligence ties between the UK and the US and the regular exchange of intelligence material, could you also clarify your government’s policy on the sharing of intelligence with the US on terrorism suspects, which might then be used to carry out drone attacks? What procedures does the UK follow to ensure that information provided by the UK to the US is not used in a way that would contravene the UK’s international human rights and humanitarian law obligations? (Mepham, Citation2012)

HRW also tried to block U.S. efforts to expand critical IHL concepts. One concept regards permissible targets. In a piece published in 2013, Executive Director Roth wrote,

even when there is an armed conflict, the laws of war … allow targeting only combatants. The act of associating with alleged militants is apparently crucial to the administration’s selection of many “signature” strikes, i.e. attacks on people whose identities are not known but who are deemed to be combatants by virtue of their behavior. But this is not enough to demonstrate the direct participation in hostilities that distinguishes someone who can be targeted in an armed conflict from a civilian in a mere support role—a driver, cook, doctor, or financier. Such civilians cannot be targeted under international law. (Roth, Citation2013a)

In addition, being an armed man in a war zone—another apparent attribute justifying a “signature” strike—is not enough to make someone a combatant in societies where men routinely bear arms. In cases of doubt, the laws of war—for example, Article 50(1) of the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions—require presuming that people are not combatants. (Roth, Citation2013a)

The al-Qaeda threat to the United States, while still real, no longer meets [international law’s standards for war]. At most, al-Qaeda these days can mount sporadic, isolated attacks, carried out by autonomous or loosely affiliated cells. Some attacks may cause considerable loss of life, but they are nothing like the military operations that define an armed conflict under international law. (Roth, Citation2013b)

Additionally, HRW tried to suppress the emergence of a broad-based norm by positing that international human rights law, which imposes greater restrictions on the use of lethal force than IHL, also applies to targeted killings. In a 2012 statement, it asserted,

in situations away from a recognized battlefield, the more appropriate standard is found in international human rights law. It permits the use of force only as a last resort to stop an imminent threat to life, not simply because someone is “part of” a violent organization or may have committed acts of violence in the past. (HRW, Citation2012)

Not only did HRW attempt to limit the targeted killing norm by preventing the CIA from further engaging in the practice, obstructing the United States’ attempt to expand critical concepts in international law, and insisting that international human rights law also governed the practice, but it also tried to illustrate how an unrestrained norm could actually harm U.S. security interests: “Strikes that kill civilians also play into the hands of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which by some accounts has tripled in size, to some 1,000 members, since 2009” (Tayler, Citation2013).

HRW has also repeatedly tried to hold the United States to its standards on targeted killing operations, which it claims are consistent with IHL. HRW has published numerous reports, statements, and articles and given Congressional testimonies demanding the United States investigate allegations of illegal civilian deaths caused by its targeted strikes, including six joint letters with fellow members of the anti-targeted killing network such as Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union, Center for Civilians in Conflict, and Human Rights First. HRW has demanded the United States explain how it complies with the distinction principle and how it addresses any violations which may occur. For instance, after a 2013 attack on a wedding procession in Yemen, HRW insisted that,

The United States and Yemen should investigate airstrikes in Yemen causing civilian deaths and ensure accountability and appropriate redress for unlawful attacks, Human Rights Watch said today. A December 12, 2013 drone strike may have killed up to 12 civilians just days before the fourth anniversary of a December 17, 2009 US cruise missile attack that killed 41 villagers that the US has never publicly acknowledged or investigated. (HRW, Citation2013)

Conclusion

This article sought to explore broadly how actors engage in norm suppression. HRW’s efforts to initially suppress a targeted killing norm and then to suppress a broad version of it illustrate both of Bloomfield’s categories of norm resistance. HRW rejected the United States’ claims that the new type of war with Al-Qaeda necessitated new norms or modifications of existing norms. It challenged U.S. efforts to expand the categories of permissible targets in IHL and the definition of armed conflict itself. Once the practice moved into the norm emergence phase, HRW stepped up its activities. It became more vocal and confrontational with the norm entrepreneur after Bin Laden’s death. It questioned whether targeted killings made both civilians and states themselves safer. It even began to publicly question the United States’ commitment to the rule of law and transparency. In doing so, it attempted to whittle away some of the intersubjective agreement which emerged after Bin Laden’s death in support of targeted killings and renew commitments to deeply entrenched norms protecting life.

And it appears that HRW’s productive power, fueled by its reputation for credible expertise and its elevated position in the human rights network, has had some impact. For instance, the United States has directly responded to norm suppressors’ concerns about transparency and accountability. In a 2016 White House press statement, the United States stated, “Today, the Administration is taking additional steps to institutionalize and enhance best practices regarding U.S. counterterrorism operations and other U.S. operations involving the use of force, as well as to provide greater transparency and accountability regarding these operations” (White House, Citation2016). And in a bid for more transparency, the United States released in 2016 aggregate casualty data on civilian casualties. President Obama also signed an executive order requiring future presidents to annually release these figures.

Currently, HRW’s activities can be described as engaging in applicatory contestation. HRW and its partners are attempting to determine what compliance entails should a targeted killing norm emerge. This explains the heightened focus on transparency and accountability. If both norm entrepreneurs and norm suppressors can agree on this element of internal contestation, the norm may progress to institutionalization, likely in the form of an international treaty. But as the revised life cycle model suggests, the practice may also fail to fully emerge if this process cannot generate sufficient intersubjective agreement.

What this discussion reveals is that norm suppression is not an activity exclusively practiced by states. Those typically considered norm entrepreneurs, human rights NGOs, can also be norm suppressors. And as norm suppressors, NGOs behave quite similarly to states. Additionally, this article reveals that norm suppression occurs similarly in both the pre-emergence and emergence phases of the norm life cycle.

This article is able to demonstrate these processes because it considers the practice of targeted killing capable of becoming a norm. In doing so, it embraces a broader conceptualization of norms to include so-called bad norms, norms which may violate human rights. If we can accept that norms can contain illiberal content, the enormous explanatory scope of the norm life cycle model becomes apparent. Doing so then greatly expands the potential research agenda for norms scholars to include such salient issues like the current global rise in right-wing populism. For instance, broadening essential concepts better enables the study of failed norm emergence and the comparative strengths and weakness of non-state and state entrepreneurs and suppressors. Additionally, because the article’s focus on HRW limits its findings, future research could be conducted with a broader lens. For instance, by building on this article’s examination of a hub and on the flourishing work on the anti-targeted killing network, we can illuminate the in-network selection method for strategies (including non-rhetorical strategies) and internal debates to help us better comprehend norm suppression. It can also help us refine our understanding in related areas, such as the defining features of democracies, how various regime types operate in the global arena, and our understandings of nonmaterial power. Third, and most relevant to this special issue, it can also help us understand the potential destabilizing effects the emergence of these kinds of norms can have on the international order, particularly as they collide with other norms, such as the norms protecting the right to life and sovereignty norms.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the editors of this special issue for the opportunity to contribute and their valuable feedback on my article. I also wish to thank Charli Carpenter, Christoph Stefes, Lucy McGuffey, and the anonymous reviewers for their insights which greatly helped shape my ideas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Betcy Jose is an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Denver. She studies global norms, civilians in war, and international humanitarian law. Her work can be found in International Studies Review, Oxford Research Encyclopedia on Politics, Global Networks, Critical Studies on Terrorism, Foreign Affairs, al-Jazeera, Duck of Minerva, and World Politics Review.

ORCID

Betcy Jose http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9529-0757

Reference list

- Abdenur, A. E. (2014). Emerging powers as normative agents: Brazil and China within the UN development system. Third World Quarterly, 35, 1876–1893. doi:10.1080/01436597.2014.971605 doi: 10.1080/01436597.2014.971605

- Anderson, K. (2011). Targeted killing and drone warfare: How we came to debate whether there is a “legal geography of War.” In P. Berkowitz (Ed.), Future challenges in national security and law (pp. 1–18). Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

- Badescu, C. G., & Weiss, T. G. (2010). Misrepresenting R2P and advancing norms: An alternative spiral? International Studies Perspectives, 11, 354–374. doi:10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00412.x doi: 10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00412.x

- Barnett, M., & Duvall, R. (2005). Power in international politics. International Organization, 59, 471–475. doi:10+10170S0020818305050010 doi: 10.1017/S0020818305050010

- Ben-Josef Hirsch, M. (2013). Ideational change and the emergence of the international norm of truth and reconciliation commissions. European Journal of International Relations, 20, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/1354066113484344

- Bin Laden killing “may set precedent” MPs are told. (2011, May 17). BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/uk-politics-13424843

- Bloomfield, A. (2015). Norm antipreneurs and theorizing resistance to normative change. Review of International Studies, 42, 310–333. doi:10.1017/S026021051500025X doi: 10.1017/S026021051500025X

- Bloomfield, A., & Scott, S. V. (2017). Norm antipreneurs in world politics. In A. Bloomfield & S. V. Scott (Eds.), Norm antipreneurs and the politics of resistance to global normative change (pp. 1–19). London: Routledge.

- Bob, C. (2017). Rival networks and the conflict over assassination/targeted killing. In A. Bloomfield & S. V. Scott (Eds.), Norm antipreneurs and the politics of resistance to global normative change (pp. 72–88). London: Routledge.

- Brunstetter, D. R., & Jimenez-Bacardi, A. (2015). Clashing over drones: The legal and normative gap between the United States and the human rights community. The International Journal of Human Rights, 19, 176–198. doi:10.1080/13642987.2014.991214 doi: 10.1080/13642987.2014.991214

- Carpenter, C. (2011). Vetting the advocacy agenda: Network centrality and the paradox of weapons norms. International Organization, 65, 69–102. doi:10.1017/S0020818310000329 doi: 10.1017/S0020818310000329

- Chappell, L. (2006). Contesting women’s rights: Charting the emergence of a transnational conservative counter-network. Global Society, 20, 491–520. doi:10.1080/13600820600929853 doi: 10.1080/13600820600929853

- CNN Wire Staff. (2010, April 28). House subcommittee hearing questions legality of drone attacks. CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2010/POLITICS/04/28/drone.attack.hearing/

- Deitelhoff, N., & Zimmerman, L. (2013). Things we lost in the fire: How different types of contestation affect the validity of international norms (PRIF Working Paper No. 18) (pp. 1–17). Frankfurt: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt.

- Downie, J. (2011, May 2). Killing Osama bin Laden. New Republic. Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/87802/osama-bin-laden-kill-legal-justification-executive-order

- Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52, 887–917. doi:10.1162/002081898550789 doi: 10.1162/002081898550789

- Florini, A. (1996). The evolution of international norms. International Studies Quarterly, 40, 363–389. doi:10.2307/2600716 doi: 10.2307/2600716

- Govern, K. (2011, October 25). Expedited justice: Gaddafi’s death and the rise of targeted killings. JURIST Blog. Retrieved from http://jurist.org/forum/2011/10/kevin-govern-gaddafikilling.php

- Heller, R., & Kahl, M. (2013). Tracing and understanding “bad” norm dynamics in counterterrorism: The current debates in IR research. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 6, 414–428. doi: 10.1080/17539153.2013.836305

- Heller, R., Kahl, M., & Pisoiu, D. (2012). The “dark” side of normative argumentation—the case of counterterrorism policy. Global Constitutionalism, 1, 278–312. doi: 10.1017/S2045381711000049

- HRW. (2011a, May 2). Osama bin Laden’s death. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/05/02/osama-bin-ladens-death

- HRW. (2011b). Killing of Osama bin Laden. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/05/04/killing-osama-bin-laden

- HRW. (2012). US: “Targeted killing” policy disregards human rights law. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/05/01/us-targeted-killing-policy-disregards-human-rights-law

- HRW. (2013). US/Yemen: Investigate civilian deaths from airstrikes. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/17/us/yemen-investigate-civilian-deaths-airstrikes

- Jose, B. (2017). Bin Laden’s targeted killing and emerging norms. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 10, 44–66. doi: 10.1080/17539153.2016.1221662

- Koh, H. H. (2010, March 25). The Obama administration and international law. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/s/l/releases/remarks/139119.htm

- Koh, H. H. (2011, May 19). The lawfulness of the U.S. operation against Osama bin Laden. Opinio Juris. Retrieved from http://opiniojuris.org/2011/05/19/the-lawfulness-of-the-usoperation-against-osama-bin-laden/

- Kratochwil, F., & Ruggie, J. G. (1986). International organization: A state of the art on an art of the state. International Organization, 40, 753–775. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300027363

- Krook, M. L., & True, J. (2012). Rethinking the life cycles of international norms: The United Nations and the global promotion of gender equality. European Journal of International Relations, 18, 103–127. doi: 10.1177/1354066110380963

- Liese, A. (2009). Exceptional necessity: How liberal democracies contest the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment when countering terrorism. Journal of International Law and International Relations, 5(1), 17–47. Retrieved from http://jilir.org/docs/issues/volume_5-1/5-1_2_LIESE_FINAL.pdf

- McKeown, R. (2009). Norm regress: US revisionism and the slow death of the torture norm. International Relations, 23, 5–25. doi: 10.1177/0047117808100607

- Mepham, D. (2012, July 16). Letter to UK Prime Minister, David Cameron on targeted killings. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/16/letter-uk-prime-minister-david-cameron-targetted-killings

- O’Driscoll, C. (2008). New thinking in the just war tradition: Theorizing the war on terror. In A. J. Bellamy, R. Bleiker, S. E. Davies, & R. Devetak (Eds.), Security and the war on terror (pp. 93–105). London: Routledge.

- Risse, T., & Sikkink, K. (1999). The socialization of international human rights norms into domestic practices: Introduction. In T. Risse, S. C. Ropp, & K. Sikkink (Eds.), The power of human rights: International norms and domestic change (pp. 1–38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodio, E. B., & Schmitz, H. B. (2010). Beyond norms and interests: Understanding the evolution of transnational human rights activism. The Journal of Human Rights, 14, 442–459. doi: 10.1080/13642980802535575

- Roth, K. (2010). Letter to Obama on targeted killings and drones. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2010/12/07/letter-obama-targeted-killings-and-drones

- Roth, K. (2011). Letter to President Obama: Targeted killings by the US government. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/12/16/letter-president-obama-targeted-killings-us-government

- Roth, K. (2013a, March 11). What rules should govern US drone attacks? Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/03/11/what-rules-should-govern-us-drone-attacks

- Roth, K. (2013b, August 3). The war against al-Qaeda is over. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/03/war-against-al-qaeda-over

- Sanders, R. (2016). Norm proxy war and resistance through outsourcing: The dynamics of transnational human rights contestation. Human Rights Review, 17, 165–191. doi: 10.1007/s12142-016-0399-1

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2001). The community trap: Liberal norms, rhetorical action, and eastern enlargement of the European Union. International Organization, 55, 47–80. doi: 10.1162/002081801551414

- Schmitt, E., & Drew, C. (2009, April 9). More drone attacks in Pakistan. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/07/world/asia/07drone.html

- Scott, S. V., & Bloomfield, A. (2017). Norm entrepreneurs and antipreneurs: Chalk and cheese, or two faces of the same coin? In A. Bloomfield & S. V. Scott (Eds.), Norm antipreneurs and the politics of resistance to global normative change (pp. 231–250). London: Routledge.

- Senn, M., & Elhardt, C. (2014). Bourdieu and the bomb: Power, language, and the doxic battle over the value of nuclear weapons. European Journal of International Relations, 20, 316–340. doi: 10.1177/1354066113476117

- Senn, M., & Troy, J. (2017). The transformation of targeted killing and international order. Contemporary Security Policy, 38, 175–211. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2017.1336604

- Shami, H. (2009, July 21). No longer a debate about targeted killings. CBS News. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/news/no-longer-a-debate-about-targeted-killings/

- Symons, J., & Altman, D. (2015). International norm polarization: Sexuality as a subject of human rights protection. International Theory, 7, 61–95. doi: 10.1017/S1752971914000384

- Tayler, L. (2013, August 29). Overlooked debacle overseas: U.S. drone strikes are ratcheting up. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/29/overlooked-debacle-overseas-us-drone-strikes-are-ratcheting

- Thomas, W. (2000). Norms and security: The case of international assassination. International Security, 25(1), 105–133. doi: 10.1162/016228800560408

- Tocci, N., & Manners, I. (2008). Comparing normativity in foreign policy: China, India, the EU, the US and Russia. In N. Tocci (Ed.), Who is a normative foreign policy actor? The European Union and its global partners (pp. 300–329). Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

- UN Department of Public Information. (2011, May 2). Secretary-General, calling Osama Bin Laden’s death “watershed moment,” pledges continuing United Nations leadership in global anti-terrorism campaign [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/sgsm13535.doc.htm

- Van Schaack, B. (2012). The killing of Osama Bin Laden and Anwar Al-Aulaqi: Unchartered legal territory. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1995605

- Vennesson, P., & Rajkovic, N. M. (2012). The transnational politics of warfare accountability: Human rights watch versus the Israel defense forces. International Relations, 26, 409–429. doi: 10.1177/0047117812445450

- White House, Office of the Press Secretary. (2016). FACT SHEET: Executive order on the US policy on pre & post-strike measures to address civilian casualties in the US operations involving the use of force & the DNI release of aggregate data on strike outside area of active hostilities [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/07/01/fact-sheet-executive-order-us-policy-pre-post-strike-measures-address

- Wiener, A. (2004). Contested compliance: Interventions on the normative structure of world politics. European Journal of International Relations, 10, 189–234. doi: 10.1177/1354066104042934

- Wunderlich, C. (2013). Theoretical approaches in norm dynamics. In H. Mueller & C. Wunderlich (Eds.), Norm dynamics in multilateral arms control: Interests, conflicts, justice (pp. 20–47). Athens: University of Georgia Press.