ABSTRACT

Recent scholarship in security studies has started to explore the causes and consequences of various forms of national restrictions in multinational military operations (MMOs). This article makes a conceptual contribution to this literature by developing a theoretical framework of national restrictions in MMOs that distinguishes between structural, procedural, and operational restrictions. I argue that these types of restrictions are governed by different causal mechanisms. Structural restrictions are relatively stable over time and effect deployment decisions irrespective of other factors. Procedural restrictions, on the other hand, can constitute veto points against deployment only in combination with distinct political preferences. Finally, operational restrictions directly affect the rules of engagement of troop contributing countries. The article illustrates the three types of restrictions and their interaction with empirical examples from a range of countries and sketches their impact on MMO deployment decisions and mandates.

During the Iraq War, Japan’s conservative government under Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi faced severe constitutional obstacles with its aim to make a military contribution to the U.S.-led invasion. In Afghanistan’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission, the German Bundeswehr operated under caveats that prohibited it from joining its coalition partners in the full range of operations by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). When chemical weapons were used in Syria in 2013, the British House of Commons effectively vetoed Prime Minister David Cameron’s proposal for military action. These examples illustrate how national regulations and conventions can affect democratic decision-making on war involvement and the behavior of the armed forces in the field.Footnote1

Recent scholarship in security studies has started to explore the causes and consequences of various forms of national restrictions on the use of force and participation in multinational military operations (MMOs).Footnote2 Works in this vein have surveyed parliamentary accountability and parliamentary war powers (Born & Hänggi, Citation2005; Dieterich, Hummel, & Marschall, Citation2010; Wagner, Peters, & Glahn, Citation2010), constitutional and legal restrictions (Ku & Jacobson, Citation2003; Nolte, Citation2003), as well as national caveats in alliance and coalition operations (Auerswald & Saideman, Citation2014; Frost-Nielsen, Citation2017; Saideman & Auerswald, Citation2012). What is missing, however, is an integrated view of existing constraints and their impact upon security policy. Which kinds of constitutional and political restrictions exist and how, exactly, do these constrain decision-making on military deployments and MMO involvement? Furthermore, to which extent can we observe variation across democracies with regards to their constitutional provisions and parliamentary involvement? Finally, does the initial decision whether to deploy forces relate to the formulation of mandates, as in how a country partakes in an operation?

This article makes a conceptual contribution to the study of MMOs, in line with the aims of this special forum, as outlined in the introduction (Mello & Saideman, Citation2019).Footnote3 Building on arguments developed in my book Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict (Mello, Citation2014), the article develops a conceptual framework of national restrictions that distinguishes between structural, procedural, and operational restrictions in MMOs. I argue that these types of restrictions are governed by different causal mechanisms and that they interact in specific ways. Structural restrictions are relatively stable over time and can exert an effect on deployment decisions irrespective of political or societal context. This is not to say that the underlying legal and institutional structures cannot be changed, but this change usually requires longer timeframes.

Procedural restrictions, on the other hand, can generate veto points against military deployments only in combination with resonating political preferences. As such, they can provide an opportunity for the political opposition and dissenting members of governing parties to voice their disagreement with a planned military operation.Footnote4 Finally, operational restrictions, or national caveats, directly affect a mission’s mandate or a country’s rules of engagement in MMOs. These were most visible during NATO operations in Afghanistan, were coalition members put forth reservations that affected their area of operations, tasks and functions, and military decision-making procedures. While it can be argued that operational restrictions enable countries to take part in MMOs where they would otherwise abstain, it is apparent that caveats pose a hindrance to the effectiveness of MMOs and the achievement of operational goals (cf. Fermann & Frost-Nielsen, Citation2019).

The next section sketches established institutionalist approaches with a focus on conceptions of institutional constraints that have been suggested as explanations for the conflict involvement of democracies. The main part then introduces the paper’s conceptual framework, distinguishing between structural, procedural, and operational restrictions in MMOs. This is followed by a discussion of the interaction of these restrictions and a conclusion with directions for future study.

Institutional constraints on democracy and conflict involvementFootnote5

Studies have long emphasized the centrality of “institutional constraints” as an important part of the explanation for the democratic peace phenomenon and democratic conflict behavior more generally (Dabros & Petersen, Citation2013; Mello, Citation2017). Institutionalist arguments variously stress the intricate nature of democratic processes, leaders’ need to gather public support for decisions on war involvement, and the institutionalization of political competition as reasons why democracies ought to be less war-prone than non-democracies (Gelpi, Citation2017; Maoz & Russett, Citation1993; Reiter & Stam, Citation2002).

However, although institutionalist arguments tend to focus on the democratic peace and regime-type differences, they also imply that the existing institutional variation among democracies ought to have an effect on their external conflict behavior. Maoz and Russett (Citation1993) mention this in passing, when they state that

[p]residential systems should be less constrained [emphasis added] than parliamentary systems, in which the government is far more dependent on the support it gets from the legislature. Coalition governments or minority cabinets are far more constrained [emphasis added] than are governments controlled by a single party. (p. 626)

It follows that differences across democratic subtypes and in the number of veto opportunities should, in principle, affect the likelihood of war involvement. Yet, taken as a whole, the democratic peace literature has neglected this source of variation.Footnote6

Electoral rules and sources of executive authority

Two distinguishing institutional characteristics of democracies are the structure of the electoral system and the sources of executive authority. The first criterion is known to have a mediated influence on the party system because majoritarian electoral rules favor two-party systems while proportional representation fosters multiparty systems (Duverger, Citation1951). Because of the link between electoral rules and the party system, differences in the former tend to affect the very nature of political competition in a country, ranging from a “winner takes all” mentality in two-party systems to more compromise-oriented politics in multiparty systems. The second criterion yields the distinction between presidential and parliamentary democracies, which has been of central concern in comparative politics (Lijphart, Citation1992). Whereas presidents obtain their political authority through direct elections and separate from the legislature, executives in parliamentary democracies are dependent upon legislative confidence. In sum, based on the proportionality of the electoral system and the balance of executive-legislative relations, the classical subtypes of democracy can be derived (Collier & Levitsky, Citation1997).

Security studies have examined various institutional settings in relation to conflict behavior. While the theoretical assumption is widely-shared that presidential democracies should be less constrained and thus more war-prone than parliamentary democracies, quantitative studies report no significant results for the parliamentary-presidential distinction (Leblang & Chan, Citation2003; Reiter & Tillman, Citation2002). Yet they find proportional representation systems to be less likely to get involved in war (Leblang & Chan, Citation2003) and that increased electoral participation reduces the likelihood of conflict initiation (Reiter & Tillman, Citation2002). As to the effects of cabinet structure in parliamentary democracies, no consensus has been reached. Some argue that coalition governments should be more restrained in their conflict behavior than single-party governments (Auerswald, Citation1999), while others find that coalition governments are more likely to reciprocate disputes than single-party governments (Prins & Sprecher, Citation1999). Still others find no evidence for differences in the conflict initiation propensity between single-party and coalition governments but indication that minority governments are less likely to initiate conflicts (Palmer, Regan, & London, Citation2004).

Veto players and veto points

Veto player and veto point approaches analyze political and institutional configurations that constrain democracies in their policy-making ability. This allows for comparisons that span across the presidential-parliamentary or majoritarian-consensus divide. Institutional veto points are conceived as “political arenas” where policy proposals can be overturned. Whether a political arena constitutes a veto point hinges foremost on its constitutional right to veto. Additionally, intra-party cohesion and the partisan composition of the executive and legislature need to be considered (Immergut, Citation1990). Veto points can arise along the chain of decision-making, beginning with the executive arena, where a government coalition partner could block a policy proposal that runs against her party’s preferences. Likewise, an unstable majority in the legislative arena can threaten the adoption of legislation when party discipline is low. Finally, unpopular policies can be overturned in the electoral arena if instruments of direct democracy, such as referenda, are a part of the political system.

Veto players are defined as the “individual and collective actors whose agreement is necessary for a change in the status quo” and be further divided into institutional and partisan veto players, where the former are constitutionally created and the latter refer to actors that are “generated by the political game” (Tsebelis, Citation2002, p. 19). A central premise of veto player theory is that increases in the number of veto players tend to preserve the status quo (Tsebelis, Citation2002, p. 25). Yet, since preferences are also taken into account, not all veto players are equally significant. On a one-dimensional scale of policy preferences, veto players whose preferred policy is located between others’ ideal points are “absorbed,” since these have no independent effect on policy stability (Tsebelis, Citation2002, pp. 28–29).

Because of their analytical reach and parsimony, veto point and veto player approaches have seen wide application in comparative politics (Ganghof & Bräuninger, Citation2006; König, Tsebelis, & Debus, Citation2010) and foreign policy analysis (Oppermann & Brummer, Citation2017). Security-related scholars, however, have been slow to adopt these frameworks. This could be, quite simply, because there is less legislative activity in security policy when compared to public policy. Another explanation could be that governments enjoy greater autonomy in foreign affairs, which corresponds to a far lower number of veto players when compared to domestic policy.

That being said, some have applied veto concepts to security issues. For instance, Reiter and Tillman (Citation2002) explore the effects of various constraints on conflict initiation. But while their article refers to veto players (p. 813), it does not assess these directly. Instead, a variable is introduced that measures whether international treaties need to be ratified by the legislature, which is taken as an indicator of legislative “foreign policy-making power” (p. 819). Reiter and Tillman (p. 822) find that among countries with such legislative power, conflict initiation does indeed become less likely, which resonates with the traditional view of institutional constraints. The study by Choi (Citation2010) aims to test Tsebelis’s theory by investigating the effect of veto players on executive conflict behavior. Using an indicator of institutional constraints that resembles the veto player approach, the study finds that “rising legislative constraints decrease the likelihood of conflict” (p. 463).

Despite advances in the extension of veto approaches to conflict studies, empirical research has neglected differences in the issue-specific authority of veto players, which varies substantially across political systems and policy areas. Moreover, most of the established and widely-used measures of institutional constraints seem to be remote from actual processes of decision-making in security policy. However, some of these shortcomings are addressed by recent work on parliamentary war powers, constitutional restrictions, and national caveats–studies that specifically investigate legislative veto rights, legal constraints in the field of security and military deployment policy, and political restrictions on military operations.

National restrictions in multinational military operations

Against the backdrop of institutionalist arguments, I suggest a conceptualization of national restrictions in MMOs that distinguishes between three types of constraints: (1) structural restrictions, which circumscribe the legal and/or political requirements of a military operation, (2) procedural restrictions, which focus on the involvement of veto players, namely the legislature, in the formal decision-making process, and (3) operational restrictions, as in national caveats, that are reflected in a mission’s mandate and/or its rules of engagement and which constrain the behavior of the armed forces in the field.

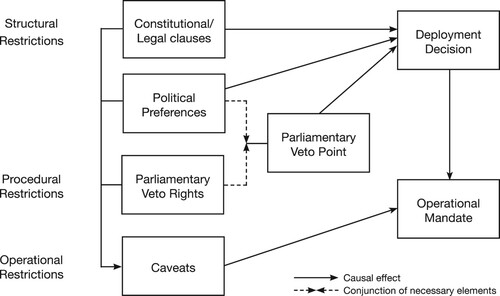

Before moving on, it is important to note the existing variance concerning the origins of national restrictions–which can be rooted in policy tradition or have a legal foundation. Many countries that harbor restrictions on the use of military force have placed these in their constitutional documents. However, in some states political practice suggests that certain restrictions on the use of the armed forces are taken into account once deployments are considered by government, even when there is no strict legal requirement to do so. With regards to the assumed causal effect of each type of restriction, however, I assume that there is no substantial difference between constitutional and “mere” political restrictions if the latter are firmly embedded in a country’s political culture. displays the suggested types and areas of restrictions and their expected causal effects, as discussed below.

Table 1. Types of national restrictions in multinational military operations.

Structural restrictions

As their name implies, structural restrictions on the use of military force refer to the most rigid forms of institutional constraints in contemporary democracies. In fact, these constitutional or political boundaries often establish a “structural veto” against military engagements, irrespective of the momentary distribution of preferences in government or among the public (Mello, Citation2014, p. 35).

What sort of constraints do structural restrictions entail? Drawing on established categories in law and security studies (Ku & Jacobson, Citation2003; Nolte, Citation2003), I distinguish three main areas of structural restrictions. The first area refers to legal provisions that restrict or prohibit military involvement in reference to public international law. A weak restriction in this area could, for instance, formally bind the armed forces to act in accordance with the rules proscribed by public international law of war (jus ad bellum). While this would under regular circumstances not constrain military involvement in any meaningful way, it can pose a constraint when missions are conducted in a gray area of international law or when operations are outright illegal. Restrictions of this kind can be found, for instance, in Belgium (d’Argent, Citation2003). However, a much stronger form of restriction in this area could require a United Nations (UN) mandate, understood as explicit UN Security Council authorization before a deployment can be considered by a country’s government.Footnote7 This is the case in Finland and Ireland, among several other countries (Wagner et al., Citation2010).

The second area of constraints circumscribes the use of force outside specific organizational frameworks. This means that unless particular international organizations are involved in a military operation, such as the UN or regional organizations such as NATO or the European Union (EU) through its Common Foreign and Security Policy, the respective country would not be allowed to deploy forces to participate in an engagement. A firm restriction in this area would also rule out any participation in ad hoc coalitions or “coalitions of the willing” as in Iraq 2003 or the fight against the Islamic State since 2015. For example, Austria prohibits participation in military operations outside UN, OSCE or EU frameworks, whereas Denmark opts out of EU operations and Germany requires military involvement of the Bundeswehr to happen inside multilateral organizational frameworks.

Finally, some constitutional documents define a set of permissible tasks for a country’s armed forces. These restrictions can prohibit, for instance, offensive military operations, such as the use of force beyond self-defense. Depending on the specific circumstances of a conflict, this restriction could either ban any involvement in an operation or limit the functions and tasks that can be assumed during the mission. Examples include Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland, all of which prohibit offensive operations, whereas the German constitution restricts the use of force to defensive purposes (Nolte, Citation2003; Shibata, Citation2003; Wagner et al., Citation2010).

How do structural restrictions influence executive decisions on the use of force? Whether certain restrictions function as a veto against a deployment depends foremost on the political circumstances of the case at hand. For instance, if we examine the wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, or Libya, we can see how some countries’ restrictions turned into a structural veto against military participation. These conflicts displayed dissimilar characteristics in terms of their legality, legitimacy, and the involved multilateral organizational frameworks. Whereas NATO’s Kosovo campaign “Allied Force” was highly controversial and received no authorization from the UN, it was also widely considered a legitimate recourse to the use of military force at the time.

Hence, in this case the most salient restriction would be in international law, though permissive tasks could restrict the extent to which a country took part in the operation. For example, the governments of Germany and Norway decided to contribute aircraft to Operation Allied Force (OAF) in support of NATO air strikes, but their planes were not equipped to strike targets. Instead, German Tornados carried anti-radiation missiles to suppress Serbian air defenses, whereas Norway ruled out ground attacks for their F16 fighter planes. This shows how structural restrictions can lead to operational restrictions, which enabled the respective countries to participate–yet stand back from offensive operations.

To take another example, the Iraq war was initiated by an ad hoc coalition of states without a Security Council mandate; it violated international law and lacked legitimacy in world opinion. Here, any structural restriction could constitute a veto against involvement. Finally, the Afghanistan war was based on the legal principle of individual and collective self-defense, manifest in Article 51 of the UN Charter, but it had neither an explicit UN authorization nor a formal involvement of NATO during the initial stages of the operation. This implies that a strict requirement of UN authorization or mandatory international organization involvement could have posed a veto against the operation in a country with the respective restrictions.

Procedural restrictions

When comparing decisions on the use of force across countries, it becomes apparent that some executives face no legislative constraints in sending the military abroad, whereas others are bound by constitutional requirements or government practice to seek parliamentary approval before authorizing troop deployments. The concept of “parliamentary war powers” refers to the concrete authority of the legislature in the field of military deployment policy (Peters & Wagner, Citation2011). In distinction from the previously discussed restrictions, mandatory parliamentary involvement in decision-making on the use of force poses a procedural restriction on democratic governments’ participation in MMOs.Footnote8

In recent years, a literature has emerged on parliamentary veto rights in the context of democratic accountability and as an institutional explanation for democracies’ (non-)involvement in military operations. These studies have provided an important specification of foreign policy processes, identifying sources of variation among democracies that have long been ignored in research on democracy and the use of force (Born & Hänggi, Citation2005; Dieterich et al., Citation2010; Wagner et al., Citation2010). Parliamentary veto rights are analytically closer and therefore more salient for political decisions than abstract measures of institutional constraints that merely differentiate between constitutional systems. Moreover, these veto rights are also distinct from the constitutional right to declare war, which is obsolete at best at a time where armed conflict is prevalent but formal declarations of war are virtually extinct.

Empirically, researchers are only beginning to explore the concrete involvement of legislatures in decision-making on security policy. Studies demonstrate, however, that the extent of legislative involvement in military deployment decisions can reduce war participation (Dieterich, Hummel, & Marschall, Citation2015; Kesgin & Kaarbo, Citation2010). In their study of Europeans’ involvement in the Iraq War, Dieterich et al. (Citation2015) formulate a “parliamentary peace” hypothesis, according to which countries with wide-ranging parliamentary war powers abstain from military participation under the precondition of a war-averse public. Recently, Wagner (Citation2018) tested this argument on a broader empirical basis and found modest evidence in favor of a parliamentary peace.

The key question for the presence of parliamentary war powers is whether the legislature holds a veto right over government decisions on military deployments. In its strongest form this right gives parliament an ex ante veto over all types of military operations. In their survey of 49 democracies, Wagner et al. (Citation2010, p. 22) identify 21 countries with a parliamentary ex ante veto right, though four of these eventually curbed parliamentary involvement. Examples include Denmark, Finland, Germany, and Sweden, among many others. By contrast, an ex post veto grants the legislature the right to end ongoing operations through a parliamentary vote.

However, the latter is a much weaker form of influence, because the material and reputational costs for repealing a decision are substantial and make it unlikely that members of parliament are willing to use this power except under severe circumstances. This is akin to “audience costs” that leaders need to take into account before backing down on a public commitment (Fearon, Citation1994). For instance, the contested U.S. War Powers Resolution essentially grants Congress an ex post veto right (Grimmett, Citation2010). A similar clause can be found in the Czech Republic, where parliamentary veto rights were substantially reduced through a constitutional amendment in 2000, leaving in place a retrospective oversight clause (Wagner et al., Citation2010, p. 46). Finally, at the low end of parliamentary war powers are informational rights that give the legislature no binding veto but a right to be informed regularly by the executive and to initiate hearings and parliamentary debate (Dieterich et al., Citation2010; Wagner et al., Citation2010).

Under which conditions do procedural restrictions such as parliamentary veto rights affect government decision-making? Whether parliament constitutes a veto point to executive decisions on military deployments, as in a political arena where government proposals can be blocked, depends foremost upon the presence of either a formal constitutional right that enables legislators to overturn executive decisions or a firmly embedded policy tradition of seeking legislative authorization for military deployments.Footnote9 Furthermore, party discipline, the preference distribution in parliament, and public opinion need to be taken into account. By contrast, structural restrictions establish a veto point against military deployments irrespective of the preference distribution in parliament or public support for military participation (Mello, Citation2014).

Operational restrictions

Operational restrictions, also referred to as national caveats, are provisions that directly affect the mandate or rules of engagement of a country’s contingent of forces in MMOs. A central concern of political and military decision-makers is that caveats can pose a hindrance to the effectiveness of MMOs and might ultimately undermine operational goals, especially for coalitions of many different countries where each national contingent brings along its own reservations and rules of engagement (Auerswald & Saideman, Citation2014; Frost-Nielsen, Citation2017; Ringsmose, Citation2010; Saideman & Auerswald, Citation2012). Coordination problems of this kind already haunted NATO operations in Kosovo where influential member states disagreed about military strategy, starting with the question whether to consider a ground intervention, to the selection of targets for strike missions, and the proper timing of a bombing pause–all of which threatened to undermine the military effort (Clark, Citation2001).

However, the topic of national caveats became truly salient after NATO took over the ISAF mission in August 2003. Newspaper reports and press statements by NATO officials soon suggested that alliance efficiency in Afghanistan was stifled primarily because of a plethora of national caveats.Footnote10 On November 11, 2004 at a Council on Foreign Relations briefing in New York, NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer addressed the issue of national caveats and placed these in the context of parliamentary war powers. His statement supports the notion that national caveats originate primarily from parliamentary interference, whereas countries without procedural restrictions are assumed to have fewer caveats:

I think we have bettered the alliance in the meantime. The national caveats have been lifted to a certain extent, but national caveats are a big problem in NATO. … National governments limit the scope of activities of their forces, and that’s a problem in Afghanistan, … it was a problem in Kosovo as well, as you well know. So my fight is a permanent fight against national caveats and in favor of lifting as many caveats as we can.

But given the fact that many countries have fairly heavy parliamentary procedures before their soldiers are going to be sent abroad, unlike the United States or unlike Great Britain or France, but take my country, the Netherlands, there’s a very heavy–I was a member of Parliament for 16 years–a very heavy parliamentary procedure before soldiers can be sent abroad, and from time to time, parliaments place the caveats. Now, you can say governments should fight those parliamentary caveats. That’s right. But I know from experience that that is not always easy. (CFR, Citation2004)

Although the prevalence of national restrictions in MMOs both raises intricate theoretical questions and contains obvious policy implications, it has so far received little attention in academic studies. Exceptions include an article by Saideman and Auerswald (Citation2012), later turned into a book-length study on NATO’s involvement in Afghanistan (Auerswald & Saideman, Citation2014), and a recent article by Frost-Nielsen (Citation2017). Examining ISAF contributions and operational restrictions across a range of NATO member states, Saideman and Auerswald (Citation2012) find substantial variance in caveats, which they explain on the basis of differences in political institutions, but also as a function of individual preferences, namely whether decision-makers focus their attention on outcomes or on behavior.

Emphasis on the former means that individuals’ primary aim is mission success, irrespective of the means necessary to achieve this. Behavior-oriented leaders, on the other hand, concentrate on military conduct in the field, seeking to avoid an overstepping of boundaries or outright misconduct, for which they could be held accountable (Citation2012, p. 71). With regards to institutions, the authors suggest that Lijphart’s (Citation1999) conceptualization of consensus and majoritarian democracies can be extended to help explain the presence or absence of these caveats. Accordingly, Auerswald and Saideman (Citation2014, pp. 69–82) argue that coalition governments tend to impose greater restrictions on the armed forces once deployed, while presidential or majoritarian parliamentary governments tend to give the military more discretion over operational decisions in the field.

Frost-Nielsen (Citation2017) provides a comparison of Danish, Dutch, and Norwegian contributions to NATO’s intervention in Libya in 2011 and the respective caveats that some of these countries imposed. His study suggests explanations for these caveats on the basis of domestic political bargaining, alliance considerations, and risk-aversion on the side of executive leaders (pp. 374–378). While each theoretical model is able to account for at least one of the cases, Frost-Nielsen (p. 392) argues that domestic factors help to explain whether or not caveats are imposed, while external pressure accounts for the kind of caveats implemented .

The interaction of structural, procedural, and operational restrictions

models the interaction of structural, procedural, and operational restrictions and their impact on deployments decisions on MMOs and their operational mandate. This can be conceived of as a sequence. Structural restrictions, understood as constitutional or legal clauses with implications on the use of military force, directly affect a country’s deployment decision–whether or not to participate in the first place, but also whether certain tasks are prohibited. In cases where no structural veto becomes manifest, decisions become a matter of political preferences and procedural restrictions. If a country holds parliamentary veto rights and the overall distribution of preferences in parliament opposes a military engagement, then this will create a veto point against MMO involvement.

On the other hand, if a deployment decision is supported by a majority of MPs, then parliamentary veto rights will not stop the country from a military engagement, even in cases of public opposition. Finally, once a concrete deployment decision has been made, operational restrictions can affect a country’s terms of military participation and rules of engagement. Caveats are subject to political preferences and they can be the resultant of structural and procedural restrictions, as indicated by the arrow on the left side.

Conclusion

Multinational military operations have become the dominant form of Western democracies’ involvement in military conflict. As pointed out by commentators and political decision-makers, some of these alliance and coalition operations are widely-affected by national restrictions. In line with the goals outlined for this special forum (Mello & Saideman, Citation2019), this article made a conceptual contribution to the emerging literature on the causes and consequences of various forms of national restrictions. I developed a conceptual framework that distinguishes between structural, procedural, and operational restrictions, arguing that these are governed by different causal mechanisms. Whereas structural restrictions are relatively stable over time and irrespective of political positions, procedural restrictions can generate a veto point against military deployments in combination with distinct political preferences. Finally, operational restrictions directly affect the mission’s mandate and a country’s rule of engagement.

The conceptual framework advanced in this article seeks to bring into dialogue and make a step towards unifying heretofore separate streams of the literature to improve our understanding of democracies’ involvement in MMOs and democratic foreign and security policy, more generally. This includes studies on legislative accountability, parliamentary veto rights, and parliamentary war powers (Born & Hänggi, Citation2005; Dieterich et al., Citation2010, Citation2015; Peters & Wagner, Citation2011; Wagner et al., Citation2010), constitutional and legal writings (Ku & Jacobson, Citation2003; Nolte, Citation2003), and works concerned with the actual conduct of democracies as coalition partners in MMOs (Auerswald & Saideman, Citation2014; Frost-Nielsen, Citation2017; Massie, Citation2016b; Schmitt, Citation2018; von Hlatky, Citation2013).

Clearly, there is a need for further systematic-comparative work to broaden the basis of our understanding of the politics of MMOs. For example, recent empirical studies indicate that parliamentary veto power has only a modest effect on conflict participation (Wagner, Citation2018) and that parliamentary involvement can yield unintended consequences that run counter to normative aims (Lagassé & Mello, Citation2018). Moreover, several Central and Eastern European states adapted their constitutional frameworks during their NATO accession. This prompts the question whether legal changes affected these countries’ subsequent conflict behavior. Finally, work on national caveats should systematically explore the interaction between structural and procedural restrictions, on the one hand, and the imposition of caveats, on the other hand. These examples indicate ample opportunities for future research.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Hylke Dijkstra, Kai Oppermann, Steve Saideman, the anonymous reviewers, as well as audiences at the 56th and 59th ISA conferences in New Orleans and San Francisco for their valuable and constructive comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Patrick A. Mello is Interim Franz Haniel Professor at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy at the University of Erfurt, Germany. He is also a Research and Teaching Associate at the Chair of European and Global Governance at the Technical University of Munich. His research focuses on international security, foreign policy analysis, and qualitative research methods, especially fuzzy-set QCA. He is the author of Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and his articles have appeared in the European Journal of International Relations, West European Politics, the British Journal of Politics and International Relations, the Journal of International Relations and Development, and others.

ORCID

Patrick A. Mello http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0751-5109

Notes

1. On these cases, see respectively, Miyagi (Citation2009), Auerswald and Saideman (Citation2014, Ch. 6), and Kaarbo and Kenealy (Citation2016).

2. There is a burgeoning literature on contributions to MMOs focusing on coalition formation and U.S. decision-making (Kreps, Citation2008), the behavior of traditional U.S. allies (Davidson, Citation2011; Massie, Citation2016a; von Hlatky, Citation2013), or small coalition partners (Reykers & Fonck, Citation2015; Schmitt, Citation2018). Others have highlighted the policy-making process on security and defense matters in the European Union (Dijkstra, Citation2013; Schade, Citation2018) or provided comparative analyses of specific military operations, as in Libya (Haesebrouck, Citation2017) or the coalition against the Islamic State (Saideman, Citation2016).

3. For an in-depth treatment of operational restrictions, see in this issue Fermann and Frost-Nielsen (Citation2019).

4. As mentioned above, the British veto against military action in Syria in 2013 is one of the most widely-studied examples of this phenomenon (e.g., Gaskarth, Citation2016; Kaarbo & Kenealy, Citation2016; Lagassé, Citation2017; Strong, Citation2015).

5. This section draws on material developed in Mello (Citation2014).

6. Notable exceptions that “unpack” democracy include the studies by Auerswald (Citation1999), Elman (Citation2000), and more recently by Dieterich et al. (Citation2015). Another comparative perspective on democracies is provided in Geis, Müller, and Schörnig (Citation2013), who focus on liberal democratic norms to explain war involvement and abstention.

7. Arguably, the requirement of a UN mandate also introduces a procedural restriction because it necessitates working through the UN organization. I thank a reviewer for alerting me to this point.

8. Parliaments comprise the key procedural restriction on military deployment decisions. In other policy areas these would be complemented by courts and public referenda, as a reviewer rightly commented. On a broader scale, these restrictions can be understood as ratification requirements under the conceptual umbrella of “two-level games” (Conceição-Heldt & Mello, Citation2018).

9. On the emergence of such a policy tradition in the United Kingdom, see McCormack (Citation2016) and Strong (Citation2018).

10. For instance, see Borchgrave (Citation2009).

References list

- Auerswald, D. P. (1999). Inward bound: Domestic institutions and military conflicts. International Organization, 53, 469–504. doi:10.1162/002081899550968.

- Auerswald, D. P., & Saideman, S. M. (2014). NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting together, fighting alone. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Borchgrave, A. D. (2009, July 15). ‘Caveats’ neuter NATO allies. The Washington Times.

- Born, H., & Hänggi, H. (2005). The use of force under international auspices: Strengthening parliamentary accountability. Geneva: Centre for the Democratic Control of the Armed Forces.

- CFR. (2004). Conversation with Jaap de Hoop Scheffer (November 11, 2004). Washington, DC: Council on Foreign Relations.

- Choi, S.-W. (2010). Legislative constraints: A path to peace? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54, 438–470. doi: 10.1177/0022002709357889

- Clark, W. K. (2001). Waging modern war: Bosnia, Kosovo, and the future of combat. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

- Collier, D., & Levitsky, S. (1997). Democracy with adjectives: Conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Politics, 49, 430–451. doi: 10.1353/wp.1997.0009

- Conceição-Heldt, E. d., & Mello, P. A. (2018). Two-level games in foreign policy analysis. In C. G. Thies (Ed.), Oxford encyclopedia of foreign policy analysis (pp. 770–789). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- d’Argent, P. (2003). Military Law in Belgium. In G. Nolte (Ed.), European military law systems (pp. 183–231). Berlin: Gruyter.

- Dabros, M. S., & Petersen, M. W. (2013). Not created equal: Institutional constraints and the democratic peace. International Politics Reviews, 1(1), 27–36. doi: 10.1057/ipr.2013.5

- Davidson, J. W. (2011). America's allies and war: Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dieterich, S., Hummel, H., & Marschall, S. (2010). Parliamentary War powers: A survey of 25 European parliaments. Geneva: Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces.

- Dieterich, S., Hummel, H., & Marschall, S. (2015). Bringing democracy back in: The democratic peace, parliamentary war powers and European participation in the 2003 Iraq war. Cooperation and Conflict, 50, 87–106. doi: 10.1177/0010836714545687

- Dijkstra, H. (2013). Policy-Making in EU security and defense: An institutional perspective. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Duverger, M. (1951). Les partis politiques. Paris: Librairie Armand Colin.

- Elman, M. F. (2000). Unpacking democracy: Presidentialism, parliamentarism, and theories of democratic peace. Security Studies, 9(4), 91–126. doi:10.1080/ 09636410008429414

- Fearon, J. D. (1994). Domestic political audiences and the escalation of international disputes. American Political Science Review, 88, 577–592. doi: 10.2307/2944796

- Fermann, G., & Frost-Nielsen, P. M. (2019). Conceptualizing caveats for political research: Defining and measuring national reservations on the use of force during multinational military operations. Contemporary Security Policy, 40, 56–69. doi:10.1080/13523260.2018.1523976.

- Frost-Nielsen, P. M. (2017). Conditional commitments: Why states use caveats to reserve their efforts in military coalition operations. Contemporary Security Policy, 38, 371–397. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2017.1300364

- Ganghof, S., & Bräuninger, T. (2006). Government status and legislative behaviour. Party Politics, 12, 521–539. doi: 10.1177/1354068806064732

- Gaskarth, J. (2016). The fiasco of the 2013 Syria votes: Decline and denial in British foreign policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 23, 718–734. doi:10.1080/ 13501763.2015.1127279

- Geis, A., Müller, H., & Schörnig, N. (Eds.). (2013). The militant face of democracy: Liberal forces for good. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gelpi, C. (2017). Democracies in conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61, 1925–1949. doi: 10.1177/0022002717721386

- Grimmett, R. F. (2010). War powers resolution: Presidential compliance: RL33532. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

- Haesebrouck, T. (2017). NATO burden sharing in Libya. A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61, 2235–2261. doi: 10.1177/0022002715626248

- Immergut, E. M. (1990). Institutions, veto points, and policy results: A comparative analysis of health care. Journal of Public Policy, 10, 391–416. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00006061

- Kaarbo, J., & Kenealy, D. (2016). No, prime minister: Explaining the house of commons’ vote on intervention in Syria. European Security, 25, 28–48. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2015.1067615

- Kesgin, B., & Kaarbo, J. (2010). When and how parliaments influence foreign policy: The case of Turkey's Iraq decision. International Studies Perspectives, 11, 19–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-3585.2009.00390.x

- König, T., Tsebelis, G., & Debus, M. (Eds.). (2010). Reform processes and policy change: Veto players and decision-making in modern democracies. New York, NY: Springer.

- Kreps, S. E. (2008). When does the mission determine the coalition? The logic of multilateral intervention and the case of Afghanistan. Security Studies, 17, 531–567. doi: 10.1080/09636410802319610

- Ku, C., & Jacobson, H. K. (Eds.). (2003). Democratic accountability and the use of force in international Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lagassé, P. (2017). Parliament and the war prerogative in the United Kingdom and Canada: Explaining variations in institutional change and legislative control. Parliamentary Affairs, 70, 280–300.

- Lagassé, P., & Mello, P. A. (2018). The unintended consequences of parliamentary involvement: Elite collusion and Afghanistan deployments in Canada and Germany. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20, 135–157. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsw029

- Leblang, D., & Chan, S. (2003). Explaining wars fought by established democracies: Do institutional constraints matter? Political Research Quarterly, 56, 385–400. doi: 10.2307/3219800

- Lijphart, A. (Ed.). (1992). Parliamentary versus presidential government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Maoz, Z., & Russett, B. M. (1993). Normative and structural causes of democratic peace, 1946-1986. American Political Science Review, 87, 624–638. doi: 10.2307/2938740

- Massie, J. (2016a). Public contestation and policy resistance: Canada’s oversized military commitment to Afghanistan. Foreign Policy Analysis, 12, 47–65. doi:10.1111/ fpa.12047

- Massie, J. (2016b). Why democratic allies defect prematurely: Canadian and Dutch unilateral pullouts from the War in Afghanistan. Democracy and Security, 12, 85–113. doi: 10.1080/17419166.2016.1160222

- McCormack, T. (2016). The emerging parliamentary convention on British military action and warfare by remote control. The RUSI Journal, 161(2), 22–29. doi: 10.1080/03071847.2016.1174479

- Mello, P. A. (2014). Democratic participation in armed conflict: Military involvement in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mello, P. A. (2017). Democratic peace theory. In P. I. Joseph (Ed.), The sage encyclopedia of war: Social science perspectives (pp. 472–476). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mello, P. A., & Saideman, S. M. (2019). The politics of multinational military operations. Contemporary Security Policy, 40, 30–37. doi:10.1080/13523260.2018.1522737.

- Miyagi, Y. (2009). Foreign policy making under Koizumi: Norms and Japan’s role in the 2003 Iraq war. Foreign Policy Analysis, 5, 349–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-8594.2009.00097.x

- NATO-PA. (2006). Lessons learned from NATO's current operations.

- Nolte, G. (Ed.). (2003). European military law systems. Berlin: Gruyter.

- Oppermann, K., & Brummer, K. (2017). Veto player approaches in foreign policy analysis. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 1–26. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.9780190228013.9780190228386

- Palmer, G., Regan, P. M., & London, T. R. (2004). What’s stopping you?: The sources of political constraints on international conflict behavior in parliamentary democracies. International Interactions, 30, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/725289044

- Peters, D., & Wagner, W. (2011). Between military efficiency and democratic legitimacy: Mapping parliamentary war powers in contemporary democracies, 1989-2004. Parliamentary Affairs, 64, 175–192. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsq041

- Prins, B. C., & Sprecher, C. (1999). Institutional constraints, political opposition, and interstate dispute escalation: Evidence from parliamentary systems, 1946-89. Journal of Peace Research, 36, 271–287. doi: 10.1177/0022343399036003002

- Reiter, D., & Stam, A. C. (2002). Democracies at war. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Reiter, D., & Tillman, E. R. (2002). Public, legislative, and executive constraints on the democratic initiation of conflict. The Journal of Politics, 64, 810–826. doi:10.1111/ 0022-3816.00147

- Reykers, Y., & Fonck, D. (2015). Who Is controlling whom? An analysis of the Belgian federal parliament's executive oversight capacities towards the military interventions in Libya (2011) and Iraq (2014-2015). Studia Diplomatica, 68(2), 91–110.

- Ringsmose, J. (2010). NATO burden-sharing redux: Continuity and change after the cold war. Contemporary Security Policy, 31, 319–338. doi:10.1080/ 13523260.2010.491391

- Saideman, S. M. (2016). The ambivalent coalition: Doing the least one can do against the Islamic state. Contemporary Security Policy, 37, 289–305. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2016.1183414

- Saideman, S. M., & Auerswald, D. P. (2012). Comparing caveats: Understanding the sources of national restrictions upon NATO’s mission in Afghanistan. International Studies Quarterly, 56, 67–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00700.x

- Schade, D. (2018). Limiting or liberating? The influence of parliaments on military deployments in multinational settings. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20, 84–103. doi: 10.1177/1369148117746918

- Schmitt, O. (2018). Allies that count: Junior partners in coalition warfare. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Shibata, A. (2003). Japan: Moderate commitment within legal strictures. In C. Ku & H. K. Jacobson (Eds.), Democratic accountability and the use of force in international Law (pp. 207–230). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strong, J. (2015). Why parliament now decides on war: Tracing the growth of the parliamentary prerogative through Syria, Libya and Iraq. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 17, 604–622. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.12055

- Strong, J. (2018). The war powers of the British parliament: What has been established and what remains unclear? British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20, 19–34. doi: 10.1177/1369148117745767

- Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto players: How political institutions work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- von Hlatky, S. (2013). American allies in times of war: The great asymmetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wagner, W. (2018). Is there a parliamentary peace? Parliamentary veto power and military interventions from Kosovo to Daesh. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20, 121–134. doi: 10.1177/1369148117745859

- Wagner, W., Peters, D., & Glahn, C. (2010). Parliamentary war powers around the world, 1989–2004. A new dataset. Geneva: Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces.