ABSTRACT

This article introduces supervised machine learning to the study of German strategic culture, analyzing both how German strategic culture has changed and the impact of strategic culture on Germany's military engagement between 1990 and 2017. In contrast with previous qualitative research on strategic culture, supervised machine learning can yield measurable and empirical insights into strategic culture and its effects at any given point in time over a very long period, based on the reproduction of human coding of a very extensive set of security policy documents. The article shows that German strategic culture has changed slowly and in a nonlinear way after the Cold War, and that strategic culture, when controlling for confounding variables and the temporal order, has a measurable impact on Germany's military engagement. The article demonstrates the analytical value of machine learning for future studies of strategic culture.

Since reunification in 1990, Germany's security policy has undergone a significant, and arguably nonlinear, transition, as the country's post-Cold War security policy has shifted back and forth between old ideas of pacifism and new ideas of activism, resisting any smooth development from one stage to the next. On the one hand, Germany has gradually taken on a more active role through Bundeswehr (German Armed Forces) deployments in, for instance, Somalia, the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Congo, Lebanon, Operation Atalanta, Mali, and the Global Coalition against the Islamic State. In Operation Allied Force (OAF) against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, German soldiers were actively involved in combat for the first time since the Second World War. As of October 2021, there are over 2,500 German soldiers deployed in 13 missions around the world, and Germany has accepted a variety of roles in missions led by the European Union (EU), North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the United Nations (UN). On the other hand, despite conducting offensive combat operations in Yugoslavia and later Afghanistan, Germany's preference for non-combat missions such as observer, logistics, training, support, or reconnaissance operations has endured. Furthermore, Germany refused to join operations such as the United States-led invasion of Iraq, the NATO-led intervention into Libya, and the European effort to secure maritime trade in the Strait of Hormuz. Thus, although Germany's security policy has changed since reunification, the country is still seen as reluctant when it comes to the use of force (compared to other European power houses such as Britain and France) with a very mixed record of participation in international military operations (Gaskarth & Oppermann, Citation2021; Hilpert, Citation2014). How can one understand Germany's mixed record of participation in military operations despite its steady growth of influence in the political and economic domains since reunification?

To answer this question, previous research has often utilized the theoretical concept of strategic culture, a concept that originated in the late 1970s (Snyder, Citation1977). The essence of the strategic culture approach is to explain how a country's enduring beliefs about the use of force and/or other strategic matters influence its security policy behavior (Bloomfield, Citation2012; Gray, Citation1981, Citation1999; Johnston, Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Libel, Citation2020). The scholars of German strategic culture have used different, but conceptually somewhat similar, terms to capture the core of the country's culture, such as “civilian power” (Maull, Citation1989), “skepticism” about the utility of force (Duffield, Citation1996; Göler, Citation2012), “anti-militarism” (Berger, Citation1998), or “anti-war” (Zehfuss, Citation2002), “pacifism” (Dalgaard-Nielsen, Citation2005), “reticence” (Hoffmann & Longhurst, Citation1999; Malici, Citation2006), and “passivity and reluctance” (Junk & Daase, Citation2013). There is also agreement among these scholars that Germany's experiences from the Second World War contributed to its unique strategic culture.

According to these researchers, knowledge about the uniqueness of German culture is key to understand Germany's hesitance in pursuing a more active role in security affairs after 1990. This cultural approach differs from realism, which struggles to explain why Germany does not pursue a more active security policy, as the perspective predicts that massive increases in material capabilities lead to a higher degree of involvement in security affairs.Footnote1 It also provides a complement to theories based on domestic politics, which, among other things, suggest that the outcome of domestic political power struggles influences the direction of German security policy (see below) (Haesebrouck & Mello, Citation2020; Rathbun, Citation2006; Wagner, Citation2017; Wagner et al., Citation2018).Footnote2

Although the strategic culture literature has enriched our understanding of German security policy in the post-Cold War era, there is room for further research. More specifically, previous research has not adequately addressed: the nonlinear development of German strategic culture and its shifts between what are here called idealpolitik and realpolitik; and the measurable impact of strategic culture on Germany's military engagement abroad after the Cold War. One reason for the lack of attention to these two issues is arguably that most previous research on strategic culture builds on a qualitative methodology.

The objective of this article is to introduce a new quantitative method, namely Supervised Machine Learning (SML), to study these two gaps in previous knowledge about German security policy, and to demonstrate the analytical value of the method. The article builds on the work of the so-called third generation of strategic culture research, in particular Johnston (Citation1995a, Citation1995b), who developed a falsifiable concept of strategic culture through which one can measure the effect of culture on a dependent variable. The article takes as its point of departure the following two research questions: How did German strategic culture change in terms of shifts between idealpolitik and realpolitik between 1990 and 2017? To what extent did strategic culture have an impact on Germany's military engagement abroad?

In contrast to a qualitative methodology, a quantitative approach can yield measurable and empirical insights into strategic culture and its effects at any given point in time over a very long period, while maintaining analytical depth and high reproducibility. The particular method of SML has seen a precipitous growth in the social sciences in the last decade (Grimmer & Stewart, Citation2013; Katagiri & Min, Citation2019; Kaufman, Citation2020; Scharkow, Citation2013; Wilkerson & Casas, Citation2017). Applied to the stage of data collection, this method allows for the reproduction of human coding of textual material on a very extensive dataset, while maintaining the quality of human analytical skills with high consistency. As SML has not been used before to study strategic culture, the article is also a methodological contribution to the field at large, thus following the age-old appeal from Hudson (Citation1991) to use Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a way of quantifying foreign policy behavior as well as Libel’s (Citation2020) more recent call for a computational approach to strategic culture.

More specifically, the article contributes to previous research on strategic culture in four ways. First, the article tests Johnston's definition of strategic culture by applying it to a large dataset and operationalizing his dichotomous classification of idealpolitik versus realpolitik for a text-based analysis of the German case. Second, the quantitative approach of the article presents a novel way of identifying cultural changes over time and explaining the extent to which strategic culture influences behavior. Third, the article traces German strategic culture for every year of the investigated period, showing in detail how German culture has shifted between idealpolitik and realpolitik. Fourth, the article demonstrates that SML as a method in the social sciences can yield significant insights into large amounts of textual data.

The remainder of the article is divided into four sections. The next section reviews previous research on strategic culture, and it elaborates on Johnston's definition of strategic culture and on cultural change, deriving hypotheses for the analysis. After that, the article describes its innovative research design, discussing how it employs SML for the data collection and coding as well as how the data is analyzed. That is followed by the analysis, which examines both the impact of strategic culture on German military engagement and how German strategic culture has changed. The final section summarizes the main findings and elaborates on the study's limitations and contributions.

Strategic culture as a theoretical tool

In 1977, Jack Snyder coined the term strategic culture in a study of Soviet nuclear strategy. According to Snyder (Citation1977), “neither Soviet nor American strategists are culture-free, preconception-free game theorists” (p. v), thereby challenging the dominant perspectives in Strategic Studies at the time. Booth (Citation1979) extended Snyder's critique, claiming that the prevalence of American-centered theories lacked a cultural dimension to understand strategy. Gray (Citation1981) also drew on Snyder's ideas in an account of American strategic culture, arguing that “strategic culture provides the milieu within which strategic ideas and defense policy decisions are debated and decided” (p. 22). These and other scholars represent the first generation of strategic culture research.

In response to critique by Johnston (Citation1995a) regarding the tautological reasoning of the first generation (see below), Gray (Citation1999) elaborated on the ontological foundations of the first generation. He claimed that culture and behavior are two inseparable phenomenon, meaning that it was futile to speak of independent and dependent variables in the way that Johnston did. According to Gray, culture influences a state's behavior, while behavior also shapes the cultural environment in which strategy is made.

The second generation, emerging in the late 1980s, took a critical view toward strategic culture, starting with the assumption that there are differences between what decision-makers say they are doing and the deeper motives for what they are doing. Klein (Citation1988), for instance, focused on the production of legitimacy, arguing that strategic culture establishes “widely available orientations to violence and to the ways in which the state can legitimately use violence against putative enemies” (p. 136). After a period of inactivity, the second generation returned in the 2010s with a focus on using security practices to trace strategic culture (Lock, Citation2010).

When he introduced the third generation, Johnston (Citation1995a) took aim at what he saw as flaws in the previous generations. He criticized, inter alia, the first generation's assumption that culture influences behavior, and vice-versa, for being tautological. On the one hand, by trying to explain behavior only with culture as “independent” variable, the first generation was over-deterministic. In Johnston's view, culture does not always lead to the same behavior, as there might be other factors influencing behavior. On the other hand, he criticized the first generation for being under-deterministic, since the theories were unable to assess the likelihood of a particular behavior. Johnston (Citation1995b) argued instead that “strategic culture, if it exists, is, like culture, an ideational milieu that limits behavioral choices. But, unlike most of the literature on culture, I also assume that from these limits one could derive specific predictions about strategic choice” (p. 36). Moreover, Johnston intended to develop a definition that is falsifiable, thus allowing (and inspiring other) researchers to separate culture from behavior and to study the effect of the former on the latter (Feng & He, Citation2021; Rosa, Citation2014). Johnston (Citation1995b) defines strategic culture as:

an integrated system of symbols (i.e., argumentation structures, languages, analogies, metaphors, etc.) that acts to establish pervasive and long-lasting grand strategic preferences by formulating concepts of the role and efficacy of military force in interstate political affairs, and by clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the strategic preferences seem uniquely realistic and efficacious. (p. 36)

This article follows Johnston's conceptualization of strategic culture for three reasons. First, by introducing a concept that is falsifiable and possible to measure, his definition creates analytical opportunities to test to what extent culture impacted on German security policy. Second, Johnston's approach is committed to competitive theory testing, allowing for the inclusion of confounding variables (see below). Third, Johnston (Citation1995b) assumes that strategic culture “can be uncovered in strategic-cultural objects” (p. 36). This is a precondition for relying on textual material, and enables the analysis of longer periods of time by employing SML.

Johnston (Citation1995b) proposes three cultural elements that carriers of strategic culture (heads of state, ministers, senior civil servants and other elites) hold, according to which one can assess a country's strategic culture: (1) the inevitability of conflict; (2) the efficacy of violence; and (3) the nature of the international system (zero-sum or positive-sum). It is then possible to place strategic culture on a continuum between idealpolitik and realpolitik based on how the carriers score on these elements. Idealpolitik and realpolitik serve as labels for the analyzed texts, based on a coding scheme derived from the elements (see below). Thus, a text labeled as idealpolitik is characterized by a strategic culture that views international politics as a positive-sum game and violence as inefficient to promote interests, and that perceives conflict as avoidable. A realpolitik culture holds the opposite beliefs. While carriers of idealpolitik beliefs tend to prefer accommodationist and cooperative strategies, carriers of realpolitik beliefs tend to prefer confrontational and hard/coercive strategies (Johnston, Citation1995b).

Military engagement is here seen as a function of strategic culture (and other variables), and it is defined in terms of two dimensions: quantity and quality. Quantity is defined as the willingness to use military deployments as a way of solving conflict. Quality is defined as the nature of military deployments, such as observer, training or combat missions. It is here hypothesized that an idealpolitik culture reduces the willingness to contribute troops to military operations (quantity) while also increasing the willingness to engage in non-combat missions (quality). A realpolitik culture increases the willingness to contribute troops to military operations (quantity) while also increasing the willingness to engage in combat missions (quality). Building on these definitions, the following two hypotheses are derived:

H1a: A strategic culture of idealpolitik promotes lower quantity and quality of military operations.

H1b: A strategic culture of realpolitik promotes higher quantity and quality of military operations.

The article applies SML to analyze whether the dominant notion found in previous research that strategic culture changes slowly can be empirically supported in the German case. The dataset can show whether change occurred and at what point in time, based on a very comprehensive source material. Therefore, the following hypothesis is also tested:

H2: Changes in strategic culture are possible but tend to occur slowly.

A quantitative research design

The empirical analysis is based on a research design that transfers qualitative textual material onto a large-N dataset. The essence of this quantitative design is SML, which is a type of AI in computer science, concerned with detecting patterns in data and using those patterns to predict future data. Methodologically, the SML approach distinguishes this article from previous research on strategic culture.

SML “is essentially a form of applied statistics with increased emphasis on the use of computers to statistically estimate complicated functions and a decreased emphasis on proving confidence intervals around these functions” (Goodfellow et al., Citation2016, p. 96). In the process of training a machine learning model, the model is fitted on a set of training data, in this article, hand-coded textual units. The training set is a smaller subset of the whole dataset, large enough to train the SML model without being too large for human coding.

It is worth pointing out that, although SML is a subcategory of AI, the label “intelligent” is misleading, as it does not resemble human intelligence in any way. Furthermore, a distinction should be made toward other forms of machine learning such as neural networks, which would not be technically possible on such small datasets. In contrast to those approaches, the method employed here does not decide on what to learn, or adjusts itself based on feedback. Instead, it is a model that is trained once, based on the human coded training dataset, and can then be applied to as many new documents as needed. Once trained, however, it does not continue to learn. The article applies an ensemble classifier, which includes different algorithms that complement each other in predicting the class of every single text unit, that is, whether the unit is of idealpolitik or realpolitik content.

Before turning to how this extensive dataset was created and how the textual data was transformed into numerical data, the article's conceptualization of strategic culture needs some further clarification. First, the article assumes that strategic culture is monolithic, implying that a single culture can be identified for a given country. While there can be sub-cultures, illustrated by the fact that support for military operations in Germany varies considerably depending on political party (Rathbun, Citation2006; Wagner, Citation2017),Footnote3 the “key hypothesis is that strategic culture generates recognizable patterns and expectations of behavior across time” (Biehl et al., Citation2013, p. 12). Including sub-cultures would inevitably undermine the aim of the article, as the possibility of different equal cultures existing at the same time would make it very difficult to differentiate between their respective influence on the aforementioned recognizable and expected behavior over time (see below).

Second, the carriers of strategic culture must be specified. While some scholars limit their focus to key decision-makers in the cabinet or to political elites, others follow a broader definition, which also includes the media (Kim, Citation2014). This article takes the latter approach. The media may have a considerable impact on security policy, as it can reproduce and shape the beliefs of the public and the elites (Entman, Citation2004), or increase/decrease public support for the implementation of changes in security policy (Kim, Citation2014, p. 279). Moreover, the media produces argumentative textual material that presents how the political elite views German strategic culture.

Third, the objects of analysis need to be defined. Johnston (Citation1995b) argues that the objects could include “the writings, debates, thoughts, and words of strategists, military leaders, and ‘national security elites,’ however defined” (p. 39).Footnote4 Thus, following Johnston, and adapting the analysis to the political system of Germany, the article includes security policy statements from the Federal Government, Parliament (Bundestag) and the media.

Government statements were retrieved through the government-published Bulletin, which includes speeches and remarks made by members of the Federal Government. Parliamentary documents were accessed from the Bundestag online database, which contains everything that was published by Parliament during the investigated period, including plenary protocols, resolutions, motions and parliamentary questions. As both government statements and the government's answers to parliamentary questions are published by Parliament, it is not possible to distinguish between statements from the government and the opposition parties. It is conceivable that partisanship correlates with strategic culture and/or behavior (Haesebrouck & Mello, Citation2020; Rathbun, Citation2006; Wagner, Citation2017; Wagner et al., Citation2018). However, this does not affect the nature of the comments analyzed. It is assumed that a realpolitik comment from a conservative party shapes strategic culture as much and in the same way as a realpolitik comment from a left-leaning party.

The media articles were retrieved from the respective outlet's online archive, and span all types of articles. The newspapers are significant in reach, covering different political views. It did occur that a politician's statement included from the Bulletin also was quoted in a media article. However, if a statement is repeated, it is most likely important, and can be viewed as a strong expression of strategic culture. An overview of the different sources and the number of documents, units and hand-coded units is provided in .Footnote5

Table 1. Number of documents, units, and hand-coded units.

Although very comprehensive, the material does not include every piece of writing that shaped German strategic culture during the investigated period. However, it does include all official statements made by those who had formal positions in the security policy decision-making process and a large collection of material written by some of the most prominent commentators of the political scenery at the time.

Coding strategic culture

In preparation for the coding, the “documents” were split into “units” of no more than 500 words (see ). This step is necessary for the SML classification (see below), because otherwise longer texts would be underrepresented in the data produced. The coding itself is not affected by this step. To create the labels (idealpolitik or realpolitik) for every unit, each unit of the training dataset was manually coded (“hand-coded units”) according to a coding scheme.

The scheme is based on Johnston's three elements of strategic culture (see above). With the help of these three dichotomous elements, Johnston defines strategic culture on the continuum between idealpolitik and realpolitik. The definition of strategic culture as a continuum is suitable, as it corresponds to the dichotomy of using or not using military deployments, as captured by the dependent variable. Furthermore, a continuum provides opportunities to capture the phenomenon in varying degrees, which corresponds to different intensities of military deployment. However, Johnston's elements are too abstract to be applied to the textual material. A more fine-grained approach was needed to capture the statements in the textual material, which Johnston's approach cannot identify with the same accuracy. The schemes offered by Giegerich (Citation2006), Göler (Citation2010), and Meyer (Citation2005) offer a more detailed differentiation between different cultural characteristics.

While this article follows the idea of including more characteristics into the scheme, it also recognizes that more than two values for each characteristic overload the scheme with information. The use of dichotomous characteristics has two advantages. First, it allows the calculation of an overall score on the continuum without running into the problem of weighting the characteristics’ intensities. Second, an SML model generally performs better when it classifies the input as one of two intensities, instead of several intensities. As a result, a scheme with seven characteristics was developed, which is detailed enough to capture the statements, while every characteristic can only take two values associated with either idealpolitik or realpolitik. The coding scheme is shown in .

Table 2. Coding scheme for strategic culture.

The first characteristic describes the end toward which the country's security policy ought to be geared: humanity/peace or the national interest. The second captures the difference between a reactive defense and proactive interventions when it comes to the nature of military missions. The third refers to the source of international legitimacy: UN or allies. The fourth captures the source of domestic legitimacy for security policy: Parliament or executive autonomy in security matters (Government). The fifth distinguishes between the views of force as an efficient or inefficient means in international politics. The sixth captures the self-conception as expressed in the texts. An idealpolitik self-conception refers to a non-intervention principle, whereas the opposite favors the use of military force. The last characteristic is applied to statements that exhibit views of the nature of international relations as either a positive- or zero-sum game. The former includes arguments for closer cooperation, and the latter involves functional arguments that for example assume that one's security is a function of an adversary's potential to endanger one's country.

During the manual coding, each (hand-coded) unit was investigated in search for statements related to the coding scheme. Every statement was coded only once, although it was mentioned twice in the same unit. Each of the codes corresponds to either a realpolitik statement, for which the value of 1 was added to the score of the unit. For every idealpolitik statement, the value of 1 was subtracted from the score. The score was then divided by the total number of statements, resulting in a total score for every unit ranging from −1.0 to +1.0. Examples from the coding of each characteristic are provided in .

Table 3. Examples of the coding scheme for strategic culture.

Data classification

The manual coding produced the training data set that was subsequently used to fit the SML model. In line with standard practice, the text units were pre-processed by stemming words, thus converting for example “go,” “goes,” “went,” and “gone” into “go” (Katagiri & Min, Citation2019, p. 163). Infrequent words and stop-words (such as “and,” “or” etc.) were also removed (Wilkerson & Casas, Citation2017, p. 531). The result is a unit-token (distinct pre-processed words) matrix that lists the frequency of each token split by units (Grimmer & Stewart, Citation2013, p. 272). Furthermore, each row is matched with the labels that were created during the manual coding. For each unit, the label is considered to be 1 if the score was positive, −1 if negative, and 0 if the score was zero. The token frequencies were subsequently used as predictors to train the SML model. An ensemble classifier proved to be the best for predicting the classification for the remaining text units.Footnote6 The model was then applied to the unlabeled dataset, thus predicting the classification for the whole dataset.

By including the probability with which the classifier made the decision, a continuous score from −1.0 to +1.0 was produced for every document. In the next step, units that were coded as 0 were removed, because they did not add substantially to the character of German strategic culture, by being concerned with, for example, technical details about defense procurement. This step removed a large chunk of the units, both within the training and the real dataset. The final count of the text units included was 1976, which resulted in a continuous classification of German strategic culture at any given year between 1990 and 2017.

SML has three distinct advantages. First, human coding risks inconsistencies in coding of larger datasets. The coding by an SML model is not tainted by personal preferences, and can minimize biases. Second, an automated process may detect patterns that contradict the common understanding that a human might miss. Third, once trained on the dataset, the model is scalable if applied to similar sources. Therefore, it can include a much larger and growing dataset during the research process that would be practically impossible with human coding, thus offering a novel way of tracing strategic culture.

Operationalizing military engagement

The dependent variable, strategic behavior in terms of military engagement abroad, is operationalized as the annual aggregate of German military missions, deployed personnel, and financial resources spent on the missions. Each value was calculated for each year between 1990 and 2017. Military missions refer to the number of military missions that was initiated or renewed during a particular year and that required the consent of Parliament.Footnote7 The number of deployed personnel was the highest number of troops that was deployed to the mission. The maximum number of allowed troops according to the mission mandate was deliberately not chosen as an indicator, as, for some missions, it reflects a much higher count than was actually deployed.Footnote8 The financial resources refer to the mission-specific costs that were specified in the mandate. This excludes figures such as wages or procurement costs for material, which are covered in the defense budget.

To calculate one score representing all three aspects, the difference between the maximum and minimum, divided by the maximum, was calculated as a weight for each aspect. Thereafter, each list of values was normalized between 0.0 and 1.0. Thus, the highest number of, for example, deployed personnel will be 1 and the lowest 0. Before adding the three normalized values together, each was multiplied by the previously calculated weights. Finally, all three values were added, resulting in a score between 0 and 3 for German strategic behavior in terms of military engagement between 1990 and 2017.Footnote9 This should not be interpreted as equating higher military engagement with more strategic behavior, or lower military engagement with less strategic behavior. The score is only used to quantitatively separate high versus low degrees of military engagement, meaning that decisions to not participate in military operations can be equally strategic to decisions to participate.

Assessing the hypotheses and the confounding variables

Hypotheses 1a and 1b were examined using linear regression, to assess the correlation between strategic culture and strategic behavior in terms of military engagement abroad. The units of analysis were divided by year, based on the assumption that monthly developments are of less interest.Footnote10 Linear regression was chosen for its ability to include multiple variables. Thus, in addition to strategic culture, the article tests five confounding variables.

First, it can be assumed that fluctuations in the number of international missions can have an impact on German strategic behavior, as an increased number of international conflicts likely leads to an increased number of German military missions. In addition, due to Germany's historical reluctance to engage in military missions without international legitimization, it could be expected that Germany would coordinate with its allies in the EU and NATO. This is based on the decision made by the Federal Constitutional Court in 1994, which established that Germany cannot use military force abroad outside of a system of collective security such as the UN, EU, or NATO. Hence, by including international missions, the analysis tests whether an increase in German missions is related to an overall increase of conflicts, rather than to a change in strategic culture. The number of initiated UN, EU, and NATO missions for every year serves this purpose, corresponding to three different variables. If the number of missions increased, the variable is coded as 1, while, if it did not, it is coded as 0.

Second, the number of German casualties for every year is also included as a confounding variable. Mueller (Citation1973) elaborated on the argument that democracies are sensitive to casualties. Thus, if a country suffers an increased number of casualties, it is less likely to engage proactively abroad. Scholars have pointed to the “body bag syndrome” in both the Vietnam War (Gartner et al., Citation1997) and the Iraq War (Bahador & Walker, Citation2013). In operational terms, this variable refers to the number of German soldiers that died while being deployed in a Bundeswehr mission (Federal Ministry of Defense, Citation2019).

Third, scholars have also claimed that the timing of the next election matter for the country's external relations, and that liberal democratic governments are less likely to engage in military operations in the period before elections (Gaubatz, Citation1999; Williams, Citation2013). Therefore, the analysis tests whether imminent elections have an influence on the dependent variable. Each year in which a federal election was held was marked as a dummy variable. As German Federal Elections are commonly held in the fall, and the unit of analysis is one year, marking the respective year captures the election campaign most accurately.

Hypothesis 2 was evaluated using Pearson's coefficient to measure the correlation between time and possible changes in strategic culture. What the collected data can offer are indications about the character of strategic culture in Germany in one year in relation to another year. As the hypothesis is assuming a directional association between time and change, from idealpolitik to gradually more realpolitik, a one-tailed test of significance was chosen. Slow cultural changes happen over a number of years, shifting back and forth between its old and new character during these years in a nonlinear way. Rapid changes happen within a year (or less), setting an entirely new course for the state, and resisting any returns to its old habitual pattern (linear development).

German strategic culture and military engagement

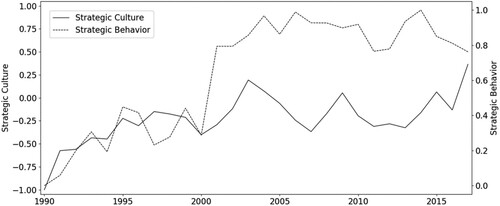

The SML approach produced a dataset tracing the development of German strategic culture and strategic behavior between 1990 and 2017. These results are shown in . For every year, the observations were grouped, and the mean was calculated. Every mean score below zero indicates that more statements from German ministers, politicians and the media were made containing an idealpolitik strategic culture in that year, compared to a realpolitik strategic culture. Any score over zero represents the opposite situation, in which more statements were made containing a realpolitik strategic culture. These scores are displayed on the left side in . Strategic behavior in terms of military engagement is plotted on a scale normalized between 0 and +1.0, displayed on the right side.

As can be seen in , the graph for strategic culture shows a positive trend toward a higher score for strategic culture as time progresses, meaning that German strategic culture becomes gradually more oriented toward realpolitik but without fully discarding its old roots of idealpolitik. The score of −1.0 in 1990 can be explained by the low number of observations in 1990. Overall, strategic culture is characterized more by idealpolitik in the 1990s, while it is characterized more by realpolitik in the early 2000s and after 2015. From 2005 to 2015 we can characterize the culture as rather balanced between the two opposites.

The developments in strategic behavior match expectations based on historical events. While Germany participated in some military missions in the 1990s, especially in the former Yugoslavia, military engagement only gradually increased, as the intensity of the missions was relatively low, with the exception of OAF. Following the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001, the ensuing anti-terror missions are mirrored strongly in the data. The temporary spike when Germany launched its most intense military missions is followed by a decrease before the curve gradually rises again in the mid-2010s. This can be attributed to the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan, and to the increasing intensity as exemplified by the Good-Friday battle or the German-ordered airstrike targeting a fuel tanker in Kunduz. Another example of how the graph matches expectations based on historical events can be identified in the penultimate spike. In 2015, Germany decided to contribute to the anti-IS coalition with support staff and reconnaissance jets (but never actively engaged in combat). The decision came after terrorist attacks in Europe and the threat of a genocide against the Yazidi minority in Iraq. The observation that developments in strategic culture and strategic behavior correspond well with both historical event data and previous research on German strategic culture greatly enhances the confidence in the results of the SML procedure.

Cultural influences on German strategic behavior

Hypotheses 1a and 1b suggest a relationship between strategic culture and strategic behavior in terms of the quantity and quality of military operations. The results of the multiple linear regression are reported in .

Table 4. Results from the linear regression.

As can be seen in the results of Model 1 (in ), strategic culture has a positive and statistically significant effect on strategic behavior when testing for all selected confounding variables. Therefore, an increase in the score for strategic culture (that is, a move toward more realpolitik) is correlated with an increase in the score for strategic behavior (that is, an increased quantity and quality of military operations). As noted above, an increase in the score for strategic behavior should not be interpreted as if Germany's behavior becomes more strategic. This finding provides support to Hypotheses 1a and 1b, and the overall model can explain approximately 35% of the variation in strategic behavior.

The confounding variable of “casualties” has a statistically significant and (surprisingly) positive impact on German strategic behavior, implying that there are no evidence for a “body bag syndrome.” However, it must be noted that the total number of battle-related deaths in Germany since 1990 is only 106. In international comparison, Germany has a relatively low number of casualties.

Model 1 also shows that the number of “UN missions” has a statistically significant effect on Germany's strategic behavior. However, the correlation is negative, meaning that an increase in UN missions leads to a decrease in the score for strategic behavior. One possible explanation for this is, as Germany's strategic culture grew more toward realpolitik, the number of UN missions that Germany participated in decreased, because the majority of German contributions were not UN missions but rather EU or NATO missions. A mission that is executed by the EU or NATO is most often based on a UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution. One example is the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan, which was based on UNSC Resolution 1386. The statistically significant positive correlation between an increase in “EU missions” and German strategic behavior further supports this conclusion. As Germany's strategic culture changed more toward realpolitik, EU missions may have become increasingly influential on German strategic behavior. It is reasonable to assume that, as an influential member of the EU, German strategic behavior is shaped by EU missions, as Germany has an important role in the initiation of operations. Finally, the confounding variables of “Elections” and “NATO missions” had no statistically significant effect on strategic behavior.

A problem with Model 1 is its temporal component. While it takes into account covariation, it cannot establish causality, as it does not ensure that cause (culture) comes before effect (behavior). Furthermore, the article assumes that the relationship between culture and behavior can be understood as a falsifiable concept through which the former affects the latter. Therefore, by using lagged independent variables, Model 2 (in ) accounts for the temporal component. The value at t−1 for strategic culture was paired with the value at t for strategic behavior. This ensures that cause comes before effect, and that the model can measure how, for example, the strategic culture in 2014 impacted on the strategic behavior in 2015. If the assumption that culture affects behavior cannot be empirically sustained, Model 2 would show no statistical significance.

The good news is that Model 2 shows that strategic culture has a statistically significant and positive impact on strategic behavior. Furthermore, the overall model fit increases to approximately 45%, indicating that, if culture is understood as preceding behavior, it has greater explanatory value. Finally, it is interesting to consider the impact of elections. Although not statistically significant, the coefficient changes from negative to positive. This indicates that election years experience a decrease in strategic culture (that is, a move toward more idealpolitik), while strategic culture scores higher in years preceding elections. While not statistically significant, it supports the claim that the government assumes the electorate to reward more peaceful narratives.

The Model 2 results also show that culture and behavior covariate when controlling for confounding variables and the temporal order. Thus, under the specified premises, the analysis provides support to Hypotheses 1a and 1b, and the results suggest a causal relationship between culture and behavior. In conclusion, the claim that strategic culture has a measurable impact on strategic behavior can be sustained. One should, however, note that strategic culture is only one of several factors influencing Germany's strategic behavior.

Changing culture of idealpolitik

Hypothesis 2 suggests that changes in strategic culture are possible but that they tend to occur slowly. In support of this hypothesis, the analysis shows that German strategic culture has shifted gradually from idealpolitik toward more realpolitik between 1990 and 2017, and that this process of change has been slow. The Pearson's test reported a correlation coefficient of 0.136 significance at the 99% confidence interval. The coefficient is also positive, which indicates that, as time progressed, the score for strategic culture increased, representing a shift toward realpolitik. However, it is important to note that strategic culture shifted toward, and did not fully change into, realpolitik. As was shown in , strategic culture shifts toward a balance between the two, with a slight overall preponderance of idealpolitik for the entire period.

In qualitative terms, the increasing degree of realpolitik means that the carriers of German strategic culture have emphasized the national interest, the proactive part of military operations, allies and the Government as sources of legitimacy, and the utility of force, an interventionist outlook and the zero-sum character of the international system more forcefully, compared to the early 1990s. However, three observations are worth pointing out. First, the development toward more realpolitik was not linear but considerably volatile on its upwards trajectory, thus matching a slow cultural change.Footnote11 Second, after reaching an approximately balanced strategic culture in 2001, the score fluctuates, but overall does not return to previous idealpolitik levels. This leads to the conclusion that once Germany's strategic culture became more balanced in the early 2000s, the development toward realpolitik slowed down. Third, after 2001, the score for strategic behavior in terms of military engagement grew more strongly than the score for strategic culture. This can be traced back to the high number of troops deployed to Afghanistan, in comparison to deployments in the 1990s. It is important to note that the two plots are on different scales. Whereas the score for strategic behavior is normalized, the score for strategic culture is not. Therefore, only the former inevitably reaches both extremes.

The graph (in ) also makes a strong case for linking cultural change to external events. While the strategic culture turned more toward idealpolitik around the turn of the century, it became significantly more realpolitik after the arguably biggest external shock to the security policy of the reunified Germany, that is, the terrorist attacks on 11 September. In addition, the strong empirical link indicating that strategic culture is shaped by events, and that it impacts on strategic behavior, give support to this article's theoretical assumption of strategic culture as an independent variable and falsifiable concept. The fact that the score only grows by a small amount in 2001 can be traced back to the terrorist attacks having been carried out in September. Therefore, the resulting cultural change only accounts for approximately one fourth of the overall score in 2001. As expected, the score grows further in 2002.

However, when considering the high score for strategic culture in 2003, one can question the impact strategic culture has on behavior, because Germany did not participate in the American-led coalition in Iraq, starting in March 2003. However, this neglects the fact that the score is barely positive and, therefore, the number of statements for either idealpolitik or realpolitik are relatively balanced. Furthermore, in contrast to the Afghanistan deployment, the coalition in Iraq did not have a UNSC mandate. In line with the coding scheme, a military deployment without a UNSC mandate is a realpolitik characteristic. Thus, it seems reasonable to assume that Germany did not join the coalition in Iraq, because its strategic culture cannot be characterized as truly realpolitik in 2003.

Conclusion

This article has presented a quantitative analysis of how German strategic culture changed in terms of shifts between idealpolitik and realpolitik between 1990 and 2017, and of the extent to which strategic culture influenced Germany's military engagement abroad. In contrast to previous research on strategic culture, these questions were approached using SML to classify an extensive set of textual data. The results showed that SML can successfully confirm previous research on German strategic culture and add new aspects of understanding, meaning that SML has demonstrated its analytical value.

The study supports the finding in previous research that German strategic culture has changed gradually after the Cold War but not to the extent that it has abandoned its previous hesitance to the use of force. Thus, we can observe both change and continuity in German strategic culture, which corresponds well with much of the recent previous research on the topic, in which the continued German reluctance to use force is a common theme (Gaskarth & Oppermann, Citation2021; Hilpert, Citation2014; Longhurst, Citation2018). The article adds to our understanding by demonstrating that the country's strategic culture has changed in a nonlinear fashion, shifting back and forth between idealpolitik and realpolitik, reaching a rather balanced state between the two from 2001. Thus, the overall character of German strategic culture has changed slowly, although the degree of realpolitik in 2017 is significantly higher than in the early 1990s.

The study also supports the finding in previous research that German strategic culture matters for its strategic behavior. The article adds to our understanding by showing that, when controlling for confounding variables and the temporal order using quantitative method, strategic culture has a measurable impact on Germany's military engagement. Thus, in contrast with previous research, the article has demonstrated that culture has a statistically significant and positive impact on German strategic behavior. Furthermore, strategic culture is only one of several factors influencing Germany's military engagement abroad.

When interpreting these results, one should consider three caveats. First, the article does not claim to have included every piece of writing that represent German strategic culture. Moreover, it does not claim to having included every possible confounding variable. However, the results of the statistical analysis, such as the R2 Score, indicate that the data represents a rather good fit.

Second, the hypotheses were only tested on German strategic culture and military engagement, implying that the empirical reach of the results are limited. Countries with a different history will have other cultural characteristics. Nevertheless, the coding scheme is designed to capture different strategic cultures, thus allowing itself to be applied to other countries (see below).

Third, while the SML algorithm proved to be accurate and consistent in reproducing human coding, there are human abilities it cannot imitate. Although SML can replicate coded statements, it is, however, limited in both its ability to consider which arguments have (deliberately) not been presented in a statement, and its capacity to take into account new arguments. In addition, the SML model is consistent once trained, however, it maintains any biases inherited from human coding. Moreover, language as an expression of political views can in some cases be complex, making it difficult for a SML model to understand, for example, tone.

Despite these limitations, the article contributes to the study of strategic culture in four ways. First, by testing Johnston's conceptualization of strategic culture on the German case, the article shows that strategic culture and its effects can be identified, measured and quantified. Second, the measurements indicate that strategic culture can be empirically traced through a large number of data points, producing a detailed account over time. The article is a novel attempt to measure strategic culture statistically for every year during a longer period of time.

Third, the article has demonstrated that SML can yield significant advantages to the study of strategic culture. Most importantly, SML classification allows the combination of human coding and large-N studies without abandoning analytic depth or suffering from too few observations. Furthermore, SML ensures that all observations are labeled according to the exact same criteria, a condition that a human simply cannot guarantee. Overall, the article supports any future applications of SML to the study of strategic culture. However, if applied to a different country, the SML model needs to be retrained on a new dataset. In such cases, the researcher can use the realpolitik versus idealpolitik distinction, which arguably has great applicability for liberal democratic states, or some other descriptive theory on strategic culture.

Fourth, the article has demonstrated that SML facilitates the study of cultural change, opening the black box of presumed continuity between two points in time. However, further cross-country comparative research is needed to corroborate this claim beyond the case of Germany. By doing so, one can critically enhance the theoretical understanding of strategic cultural change. In addition, cross-country research would be able to place cultural change in context, allowing for more precise conclusions regarding the speed of change.

Another avenue for future research is to use SML and an accompanying statistical analysis with aggregated scores from the different sources, thus enabling one to trace the relative influence of each source on strategic culture. This could highlight for example the role of Parliament or the media in shaping strategic culture. Doing so would greatly enhance the understanding of the carriers of strategic culture as well as their different impact across countries. Overall, the article makes a strong case for considering AI in future studies of strategic culture and, more broadly, in foreign policy analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback on this article. The dataset used in this article is available from https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SQMJ6K

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Tappe

Jonathan Tappe holds a MSc in War Studies from the Swedish Defense University. This is his first published article, based on his Master's thesis Between Idealpolitik and Realpolitik: A Machine Learning Approach to the Study of German Strategic Culture.

Fredrik Doeser

Fredrik Doeser is Associate Professor in War Studies at the Swedish Defense University. He has recently published articles in Defense Studies, Foreign Policy Analysis, and Journal of Strategic Studies.

Notes

1 While for example Mearsheimer (Citation1990) wrote explicitly about the German case, similar predictions could be derived from the theories of Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz.

2 For instance, Rathbun (Citation2006) suggests that German pacifism is a myth, since there never was any parliamentary consensus on a principled opposition to the use of force in the 1990s.

3 Military operations are often contested along the left/right spectrum, with support growing as we move further to the right.

4 The article is based on the assumption that the words decision-makers say are related to the strategic cultural beliefs they have, and that these beliefs are related to their behavior. This implies that the article cannot capture cases in which decision-makers deliberately use aspects of their country's strategic culture to legitimize a particular behavior, made for reasons other than strategic culture (Schmitt, Citation2012).

5 The precise meaning of the terms “documents,” “units,” and “hand-coded units” is provided below.

6 For a more detailed description of the classification process, contact the corresponding author.

7 An alternative approach would have been to distinguish between missions that are initiated and those that are renewed, as the former, representing a deviation from the status quo, might be qualitatively different from the latter. Another alternative would have been to differentiate between EU, NATO, and UN operations, or to include specific mission-related caveats. However, such differences are difficult to capture in a quantitative study spanning almost 30 years. For a complete list of all German military missions that were included in the analysis and how they were coded, contact the corresponding author.

8 For example, the maximum number of troops for the German contribution to UN African Union Hybrid Operation in Darfur was 50. However, the highest number of deployed troops was only seven.

9 For access to the complete dataset and the Python scripts for the data processing and machine learning tasks, contact the corresponding author.

10 Although a monthly split of the data would have been possible, years were chosen as the unit to reduce bias in the data. Comparing for example August to April would be difficult as the former is during a time where most political institutions have a minimum in activity due to the summer break. This leads to a low amount of data being available and thus possibly more inaccurate numbers. Choosing years as the unit therefore masks some development, such as 11 September, but it balances out annual fluctuations.

11 In contrast, a rapid change would have been straight upwards toward more realpolitik without at times shifting back to more idealpolitik.

References

- Bahador, B., & Walker, S. (2013). Did the Iraq War have a body bag effect? American Review of Politics, 33(2), 247–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15763/issn.2374-7781.2012.33.0.247-270

- Berger, T. U. (1998). Cultures of antimilitarism: National security in Germany and Japan. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bertram, C. (1992, May 29). Das Korps der guten Hoffnung. Die Zeit. https://www.zeit.de/1992/23/das-korps-der-guten-hoffnung?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.se%2F

- Biehl, H., Giegerich, B., & Jonas, A. (2013). Introduction. In H. Biehl, B. Giegerich, & A. Jonas (Eds.), Strategic cultures in Europe: Security and defence policy across the continent (pp. 7–17). Springer.

- Bloomfield, A. (2012). Time to move On: Reconceptualizing the strategic culture debate. Contemporary Security Policy, 33(3), 437–461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2012.727679

- Booth, K. (1979). Strategy and ethnocentrism. Holmes & Meier.

- Booth, K. (1990). The concept of strategic culture affirmed. In C. G. Jacobsen (Ed.), Strategic power USA/USSR (pp. 121–128). Martin’s Press.

- Brössler, D. (2017, February 16). Amerika droht Nato-Partnern. Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/transatlantisches-verteidigungsbuendnis-amerika-droht-nato-partnern-1.3380772

- Burns, A., & Eltham, B. (2014). Australia’s strategic culture: Constraints and opportunities in security policymaking. Contemporary Security Policy, 35(1), 187–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2014.927672

- Dağdelen, S. (2016, November 30). Rede im Deutschen Bundestag. Plenarprotokoll des Deutschen Bundestages, 18(205). https://dserver.bundestag.de/btp/18/18205.pdf

- Dalgaard-Nielsen, A. (2005). The test of strategic culture: Germany, pacifism and pre-emptive strikes. Security Dialogue, 36(3), 339–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010605057020

- Duffield, J. S. (1996). World power forsaken: Political culture, international institutions, and German security policy after unification. Stanford University Press.

- Entman, R. (2004). Framing news, public opinion, and U.S. foreign policy. University of Chicago Press.

- Federal Ministry of Defense. (2019, October 21). FüSK III, Todesfälle in der Bundeswehr im Auslandseinsatz und in anerkannten Missionen. https://www.bundeswehr.de/de/ueber-die-bundeswehr/gedenken-tote-bundeswehr/todesfaelle-bundeswehr

- Feng, H., & He, K. (2021). A dynamic strategic culture model and China’s behaviour in the South China Sea. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 34(4), 510–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1642301

- Gartner, S., Segura, G., & Wilkening, M. (1997). All politics are local: Local losses and individual attitudes toward the Vietnam War. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(5), 669–694. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002797041005004

- Gaskarth, J., & Oppermann, K. (2021). Clashing traditions: German foreign policy in a new era. International Studies Perspectives, 22(1), 84–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekz017

- Gaubatz, K. T. (1999). Elections and war: The electoral incentive in the democratic politics of war and peace. Stanford University Press.

- Giegerich, B. (2006). European security and strategic culture: National responses to the EU’s security and defence policy. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Glotz, P. (1993, March 8). Der Mannbarkeits-Test. Der Spiegel. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/der-mannbarkeits-test-a-75db5846-0002-0001-0000-000013682019

- Göler, D. (2010). Die Strategische Kultur der Bundesrepublik. In A. Dörfler-Dierken & G. Portugall (Eds.), Friedensethik und Sicherheitspolitik (pp. 185–199). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Göler, D. (2012). Die Europäische Union in der Libyen-Krise: Die “responsibility to protect” als Herausforderung für die Strategischen Kulturen in Europa. Nomos, 35(1), 3–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24223976

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep learning. MIT Press.

- Gray, C. S. (1981). National style in strategy: The American example. International Security, 6(2), 21–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2538645

- Gray, C. S. (1999). Strategic culture as context: The first generation of theory strikes back. Review of International Studies, 25(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210599000492

- Grimmer, J., & Stewart, B. (2013). Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis, 21(3), 267–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028

- Haesebrouck, T., & Mello, P. (2020). Patterns of political ideology and security policy. Foreign Policy Analysis, 16(4), 565–586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/oraa006

- Hilpert, C. (2014). Strategic culture change and the challenge for security policy: Germany and the Bundeswehr’s deployment to Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Himpsl, R. (2011, June 7). Eine Frage des Interesses: Experten diskutieren in Neubiberg über die Zukunft Afghanistans. Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/muenchen/landkreismuenchen/konzertmitschnitt-eh-leyla-reragu-1.4579680

- Hoffmann, A., & Longhurst, K. (1999). German strategic culture in action. Contemporary Security Policy, 20(2), 31–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13523269908404220

- Hudson, V. M. (Ed.). (1991). Artificial intelligence and international politics. Routledge.

- Johnston, A. I. (1995a). Thinking about strategic culture. International Security, 19(4), 32–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2539119

- Johnston, A. I. (1995b). Cultural realism: Strategic culture and grand strategy in Chinese history. Princeton University Press.

- Jung, F. J. (2009, June 18). Rede des Bundesministers der Verteidigung, Dr. Franz Josef Jung, zur Zukunftsfähigkeit der Bundeswehr vor dem Deutschen Bundestag. Bulletin der Bundesregierung.

- Junk, J., & Daase, C. (2013). Germany. In H. Biehl, B. Giegerich, & A. Jonas (Eds.), Strategic cultures in Europe: Security and defence policies across the continent (pp. 139–152). Springer.

- Katagiri, A., & Min, E. (2019). The credibility of public and private signals: A document-based approach. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 156–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000643

- Kaufman, A. (2020). Measuring the content of presidential policy making: Applying text analysis to executive branch directives. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 50(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12629

- Kim, J. (2014). Strategic culture of the Republic of Korea. Contemporary Security Policy, 35(2), 270–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2014.927675

- Klein, B. S. (1988). Hegemony and strategic culture: American power projection and alliance defence politics. Review of International Studies, 14(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S026021050011335X

- Libel, T. (2016). Explaining the security paradigm shift: Strategic culture, epistemic communities, and Israel’s changing national security policy. Defence Studies, 16(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2016.1165595

- Libel, T. (2020). Rethinking strategic culture: A computational (social science) discursive-institutionalist approach. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(5), 686–709. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2018.1545645

- Lock, E. (2010). Refining strategic culture: Return of the second generation. Review of International Studies, 36(4), 685–708. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210510000276

- Longhurst, K. (2018). Germany and the use of force. Manchester University Press.

- Malici, A. (2006). Germans as Venutians: The culture of German foreign policy behavior. Foreign Policy Analysis, 2(1), 37–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2005.00019.x

- Maull, H. W. (1989). Germany and Japan: The new civilian powers. Foreign Affairs, 69(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/20044603

- McCraw, D. (2011). Change and continuity in strategic culture: The cases of Australia and New Zealand. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 65(1), 167–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2011.550102

- Mearsheimer, J. J. (1990). Back to the future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War. International Security, 15(1), 5–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2538981

- Merkel, A. (2008, March 11). Rede auf der 41. Kommandeurtagung der Bundeswehr. Bulletin der Bundesregierung.

- Meyer, C. O. (2005). Convergence towards a European strategic culture? A constructivist framework for explaining changing norms. European Journal of International Relations, 11(4), 523–549. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105057899

- Mueller, J. E. (1973). War, presidents, and the public opinion. John Wiley & Sons.

- Rathbun, B. C. (2006). The myth of German pacifism. German Politics and Society, 24(2), 68–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3167/104503006780681885

- Rosa, P. (2014). The accommodationist state: Strategic culture and Italy’s military behaviour. International Relations, 28(1), 88–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117813486821

- Scharkow, M. (2013). Thematic content analysis using supervised machine learning: An empirical evaluation using German online news. Quality & Quantity, 47(2), 761–773. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9545-7

- Scharping, R. (1999, September 23). Rede an der Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr in Hamburg. Bulletin der Bundesregierung, 99(56). https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/975954/772862/9326d2cc64a715fa62c67873712d01c2/56-99scharping-data-pdf?download=1

- Schemel, H. (2010, November 23). Kämpfen für Rohstoffe: Muss die Bundeswehr Ressourcen und Handelswege sichern? Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/kampf-um-rohstoffe-europa-fordert-china-bei-seltenen-erden-heraus-1.1296936

- Schmitt, O. (2012). Strategic users of culture: German decisions for military action. Contemporary Security Policy, 33(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2012.659586

- Schröder, G. (2005, June 7). Rede beim Festakt zum 50. Jahrestag der Gründung der Bundeswehr in Berlin. Bulletin der Bundesregierung.

- Snyder, J. L. (1977). The Soviet strategic culture: Implications for limited nuclear operations. RAND.

- Süddeutsche Zeitung. (1995, November 18). Neue NATO, alte Nöte. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/muenchen/landkreismuenchen/konzertmitschnitt-eh-leyla-reragu-1.4579680

- Süddeutsche Zeitung. (2009, September 11). Merkel soll Afghanistan zur Chefsache machen. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/bundeswehrverband-merkel-soll-afghanistan-zur-chefsache-machen-1.26364

- Wagner, W. (2017). The Bundestag as a champion of parliamentary control of military missions. Sicherheit und Frieden, 35(2), 60–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5771/0175-274X-2017-2-60

- Wagner, W., Herranz-Surrallés, A., Kaarbo, J., & Ostermann, F. (2018). Party politics at the water’s edge: Contestation of military operations in Europe. European Political Science Review, 10(4), 537–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000097

- Weigel, A. (2003, June 18). Rede im Deutschen Bundestag. Plenarprotokoll des Deutschen Bundestages, 15(51). https://dserver.bundestag.de/btp/15/15051.pdf

- Wilkerson, J., & Casas, A. (2017). Large-Scale computerized text analysis in political science: Opportunities and challenges. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1), 529–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052615-025542

- Williams, L. (2013). Flexible election timing and international conflict. International Studies Quarterly, 57(4), 449–461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12054

- Zehfuss, M. (2002). Constructivism in international relations: The politics of reality. Cambridge University Press.