ABSTRACT

The international cybersecurity regime typifies the rise of informality in modern global governance. Despite the increase in sophisticated cyber operations globally, states do not embrace formal multilateral cooperation to prevent and mitigate them. What explains the preference for informal governance in international cybersecurity, and why have non-binding agreements around “responsible behaviour” proliferated in this domain? In introducing a special issue that highlights various dimensions of informal international cybersecurity governance, this article analyses two major factors that deepen informality: multipolar geopolitics, which has made formal cooperation difficult, and the rise of non-state actors, whose technical standards not only emerge as de facto governance standards, but who have also engaged in cyber diplomacy through informal channels. Drawing on recent scholarship that explains the emergence of informality in global governance, the article calls for greater attention to be paid to the substantive outcomes of informal institutions to understand their stickiness in regimes.

The shadow of informality looms large over modern global governance. In recent years, scholars of international relations have documented a steady but discernible trend towards the decline of formal multilateral organizations and the rise, in their stead, of informal institutions and agreements in various domains of global governance (Roger & Rowan, Citation2023; Vabulas & Snidal, Citation2021; Westerwinter et al., Citation2021). This turn to informality is mainly driven by states’ desire to preserve flexibility with respect to their multilateral commitments and to create or join like-minded coalitions whose membership and agenda is fluid, task-specific (Reykers et al., Citation2023) or open-ended. However, their informal character also makes it challenging to study how these institutions or agreements evolve, and whether they succeed in inducing state compliance. The accountability of such mechanisms, some of which can be secretive in nature (Allen & Benson, Citation2023; Johnston, Citation1998), to domestic and international constituents (Bradley et al., Citation2023) is also an important policy concern.

Westerwinter et al. (Citation2021) define informality as the creation of “rules and norms [through] institutional structures and procedures that are not enshrined in formally constituted organizations” (p. 2). The formal character of an organization depends on two essential criteria: its “legalization through a charter [or] treaty” and functioning via a “permanent secretariat” or headquarters (Vabulas & Snidal, Citation2021). Informal entities do not possess either attribute (Vabulas & Snidal, Citation2021). Another important feature, by implication, is that informal organizations and processes can only produce non-binding guidelines (Abbott & Faude, Citation2021), such as political norms.

While informal international governance is increasingly the subject of empirical and conceptual analysis, a few open questions remain. Firstly, as the above definitions of informality indicate, scholars of international organizations have focused mainly on structural or functional attributes of informal institutions. These attributes are certainly important to identify informality and the reasons why states turn to informal governance in the first place, but insufficient to explain whether or how they then advance and shape the interests of states. Part of the problem lies in treating informality as an adjunct feature of formal governance, that is, as addressing a commitment problem or clarifying a governance agenda associated with a treaty-based multilateral institution (Roger, Citation2020). Yet, as we show through the example of international cybersecurity governance in this article, informality can determine how states interact with each other across a domain of global governance, and shape mutual expectations regarding compliance even in the absence of formal rules or institutions. In other words, informality can be pervasive in nature, and the driver of frameworks, expectations, and interests in a regime.

Secondly, while empirical evidence certainly highlights a systemic shift towards informal global governance, how this shift has manifested in international security regimes has only recently come into more focus (Brosig, Citation2023; Bueger & Edmunds, Citation2021; de Coning et al., Citation2022; Hofmann & Yeo, Citation2023; Reykers et al., Citation2023). Studies of informal governance have tended to focus more on development and climate regimes. While serving as rich illustrations of the move towards informal governance mechanisms such as multistakeholder commissions, ad hoc intergovernmental groups, and loose advocacy coalitions, they do not address whether and why states prefer informality when cooperation around issues of hard, national security interests is at stake. Thirdly, why does informality persist in regimes? It is one thing for states to create informal mechanisms but another to persist with them, or facilitate their proliferation within a regime. This is a question that has been asked (Alter, Citation2022), but to which explanations have not been quite forthcoming. The question is particularly relevant given the policy concerns of accountability and effectiveness of informal governance, and therefore requires further analysis.

These three aspects of informal governance are squarely implicated in the domain of international cybersecurity. In this article, we address how informality has shaped engagement between states and non-state actors on cybersecurity, and why it has persisted for a long period of time. The regime complex of international cybersecurity governance is, at the time of writing, populated almost entirely by informal intergovernmental mechanisms and multistakeholder bodies (Kavanagh, Citation2017; Ruhl et al., Citation2020). These informal institutions have variously articulated non-binding cyber norms, offered their interpretations of how existing rules apply to state behavior in cyberspace, developed Confidence-Building Measures, and implemented capacity-building initiatives to induce compliance with norms and rules. The UN Group of Governmental Experts in cybersecurity (UN GGE), arguably the preeminent entity among these informal groups, has convened in six iterations since 2004—it is the longest running ad hoc group of its kind within the UN system, since expert groups on threats to international security were first set up by the UN General Assembly in 1968 (VERTIC, Citation2017). However, the GGE has no permanent secretariat, and participating “Experts”—usually diplomats nominated by states—are assisted by a joint support team of individuals with substantive expertise and UN experience, alongside staff from the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) and UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) (UN General Assembly, Citation2021).

Over the years, successive UN GGE reports have developed a framework of responsible state behavior in cyberspace, whose centerpiece is a set of eleven, voluntary, non-binding norms that call on states to inter alia, refrain from certain kinds of cyber operations and to prevent their territory from being used for malicious cyber operations that target other states (UN General Assembly, Citation2015). These norms have been adopted by the UN General Assembly, but they are not binding on states. Other informal or semi-formal intergovernmental groups in the regime complex include the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on cybersecurity and UN Ad Hoc Committee on Cybercrime. As of this article highlights, we classify the AHC on cybercrime as a semi-formal institution, in that it can—as with other ad hoc and informal committees of the UN—develop its own rules of deliberation, and its membership is not confined to a pre-determined set of states or stakeholders. Nevertheless, the AHC will contribute to formal governance given that its draft convention, upon endorsement by the UN General Assembly, will bind states based on its rules of ratification. The OEWG’s parallel co-existence and similarity to the UN GGE’s mandate has left its precise objectives unclear (Efrony, Citation2021). The first OEWG was constituted in 2019 and submitted its report in 2021. The team that assisted the 2019–2021 GGE with substantive and administrative expertise also shared its resources with the UN GGE (Tiirmaa-Klaar, Citation2021). That same year, the UN GA established a second OEWG, whose term runs till 2025. The UN Ad Hoc Committee has been formally tasked with developing a convention on cybercrime.

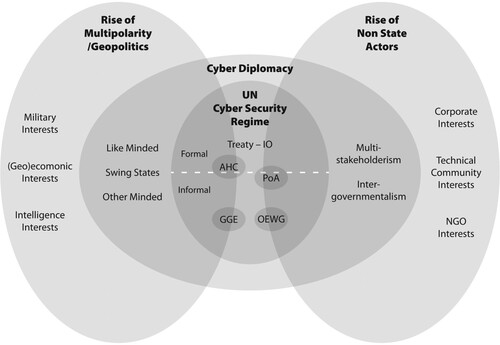

Figure 1. The international cybersecurity regime. Source: concept by the authors, design by Paul Oram Graphic Design.

Additionally, UN member states also approved the creation of a Programme of Action (PoA) after the OEWG concludes in 2025, as a “permanent, action-oriented mechanism” to continue discussing and advancing the framework of responsible state behavior in cyberspace. Despite terming the proposed PoA as a “permanent mechanism,” the UN GA has left its “scope, structure, content and modalities” to the “consensus outcomes” of the 2021–2025 UN OEWG, leaving its precise character uncertain (UN General Assembly, Citation2023). At the time of writing, the PoA is free to determine whether to develop “additional voluntary, non-binding norms or additional legally binding obligations,” further underlining its semi-formal character (UN General Assembly, Citation2023).

Meanwhile, prominent, informal multistakeholder initiatives such as the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC) and the Paris Call on Trust and Security in Cyberspace (the Paris Call) have not only shaped international cybersecurity governance through their own pronouncements, but also advanced the work of the aforementioned intergovernmental groups by clarifying key cybersecurity concepts or norms from their reports. Then there are private initiatives led by think-tanks or academic institutions such as the Tallinn Manuals and the Oxford Process that attempt to clarify the scope of existing obligations of states in cyberspace. Comprising primarily of reputed academics, the pronouncements of these informal initiatives are also not binding, but their findings have been consequential, in that states have often referred to, or aligned their own legal positions with those of these initiatives. Such private initiatives have become influential also because states chose expressly to reject formal channels of law ascertainment in cyberspace, such as through the International Law Commission.

While it may not be accurate to suggest that the pervasive informality of the international cybersecurity regime is typical of contemporary security governance, it is not in question that security regimes have also witnessed significant informalization in the last two decades. Contact groups (Middle East Quartet, Contact Group on Piracy), club-like entities for export controls (Proliferation Security Initiative), informal security collectives (Quad, AUKUS), and ad hoc task forces (G5 Sahel Joint Force, Takuba Task Force) have all emerged as prominent informal mechanisms of cooperation (Reykers et al., Citation2023). The key difference in the case of international cybersecurity, as discussed initially, is that informality does not exist simply to augment formal cooperation—or in some cases, circumvent challenges associated with existing mechanisms—but it has driven the development of the regime itself. Early indications point towards similar trends in other regimes that implicate digital technologies, notably the regimes around the responsible use of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems and Artificial Intelligence (Bode et al., Citation2023).

This special issue of Contemporary Security Policy highlights various facets of informality in international cybersecurity governance, while investigating its causes and remarkable persistence. In other words, what explains the origins of informal governance in international cybersecurity, why has it been sticky, and what are the consequences of such informality for both state and non-state actors? The introduction to the special issue serves three objectives. First, it evaluates existing explanations of informal global governance in the context of international cybersecurity. Specifically, it highlights informality as being driven by two major shifts: the rise of multipolar geopolitics coinciding with a general decline of formal multilateral cooperation, and concurrently, the increased ability of private actors to engage in cyber diplomacy, and shape facts on the ground through their ownership and management of critical Internet resources. Having reviewed the state of play with respect to geopolitics and multistakeholder diplomacy, the article subsequently presents a conceptual mapping of the international cybersecurity regime, highlighting both key actors involved and their roles within this regime (). Contributions to the special issue, which this article subsequently introduces, review both these aspects in more detail. Finally, this article delves into a relatively under-explored theme in scholarship on informality: why states persist with non-binding agreements and frameworks. The way in which informal institutions have conducted their business is essential to understanding their endurance and proliferation within the international cybersecurity regime, this article argues, drawing specifically on International Relations/International Law (IR/IL) scholarship that focuses on the practices of formal and informal institutions.

Explaining institutional creation and endurance: Existing accounts and gaps in scholarship

The preponderant explanation for institutional emergence and survival in international relations has, for more than three decades, revolved around functionalist theories: multilateral institutions arise because they facilitate interstate cooperation in an anarchical system by reducing transaction costs and decreasing uncertainty (Adler & Haas, Citation1992; Goldstein & Keohane, Citation1993; Keohane, Citation1984; Young, Citation1989). As scholars have pointed out, this theoretical framework was well suited to explain formal cooperation at a time of ostensible unipolarity (Stone, Citation2013). However, the rise of new military and economic (state and non-state) centers of power, disagreement between states on fundamental principles that should form the basis for cooperation, and a growing wave of nationalism sweeping through established democracies has led over the last two decades to a crisis in multilateralism (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni & Hofmann, Citation2020; Schuette & Dijkstra, Citation2023). This crisis does not portend the “death of the treaty” (Trachtman, Citation2014)—if anything, the Covid-19 pandemic appears to have triggered a renewed interest among states in treaty-making—but the reality is that informal governance is on the rise. Shifts in power distribution among states have increased uncertainty and enhanced security dilemmas, especially while the international legitimacy of the rising powers is still being established (Jervis, Citation1976; Schweller & Pu, Citation2011). In the absence of a stable multilateral dynamic (Martin, Citation1992, p. 791), global governance has moved towards informal institutions, characterized by non-binding outcomes, fluid boundaries, overlapping agendas, and multistakeholder involvement.

Acknowledging this development, both international relations and international law scholars have in the last decade advanced various explanations for the rising popularity of informal governance. In IR scholarship, this literature can be broadly classified into two themes: first, analyses of the form and function of informal institutions (for a review, see Roger et al., Citation2023; Westerwinter et al., Citation2021) and second, of “regime complexes” where informal institutions sit alongside formal governance mechanisms (Alter & Raustiala, Citation2018). Both strands of scholarship offer crucial insights into the origins of informality in global governance. Nevertheless, some blind spots remain. The literature on informal institutions has tended to focus on what they are rather than what they do (Cooper et al., Citation2022). In other words, while these frameworks advance explanations about the design of informal institutions, they seldom shine light on how their outcomes advance global governance in specific domains. In particular, this literature has only begun to address why informality persists (Manulak & Snidal, Citation2021; Roger, Citation2020): informality’s stickiness in regimes arguably has as much to do with compliance by states and non-state actors as it does as it does with the flexibility or task-specific character associated with informal institutions.

Similarly, the regime complex literature has embraced an institutionalist logic (Drezner, Citation2009), prompting scholars to focus more on organizational form than substantive governance outcomes or decision-making processes (Alter, Citation2022). This literature addresses issue linkages (Clark, Citation2021; Hofmann & Yeo, Citation2023) and overlapping mandates of institutions within regimes (Drieschova et al., Citation2020; Margulis, Citation2021) but as Alter (Citation2022) argues, is yet to offer explanations around how powerful interests or institutional environments impose normative parameters around what a regime complex can and cannot address. Realist (Glaser, Citation2019; Mearsheimer, Citation2019), constructivist (Adler & Pouliot, Citation2011; Finnemore & Jurkovich, Citation2020; Scholte, Citation2020), and even rationalist-institutionalist accounts (Abbott et al., Citation2016; Lake, Citation2021) of the last decade have addressed various aspects of global governance that align closely with the literature both on informal governance and regime complexity, and could potentially fill in the gaps.

On the other hand, international law scholarship is concerned primarily with the compliance end of the stick. As with IR, there has been a renewed interest among legal theorists in the last decade to address what is interchangeably called “soft” (Shelton, Citation2009) or “informal” international law (Pauwelyn et al., Citation2012). There is today a robust body of theory that examines the relationship between non-binding norms and principles and public international law from doctrinal (Klabbers, Citation2012), rational-choice (Guzman & Meyer, Citation2016), sociological (Garth, Citation2018), behavioral (Broude & Shereshevsky, Citation2021) and cognitive (Bianchi & Hirsch, Citation2021) perspectives, among others. Complementing this scholarship is the International Law (IL)/IR literature that offers a much-needed focus on institutions as well as material and ideational factors that shape regimes (Chayes & Chayes, Citation1998; Dunoff & Pollack, Citation2012; Goldstein et al., Citation2000). While the focus of IL/IR literature has, over the previous decade, been mostly on legal or binding norms within those regimes, that is changing, with scholars highlighting the persistence of informal governance mechanisms and norms (Finnemore & Hollis, Citation2016; Johnstone & Ratner, Citation2021).

We draw on insights from the aforementioned literature on institutional governance and compliance to explain the origins and persistence of informality in international cybersecurity governance. Unlike the well-known work of Nye (Citation2014) who focused on the “Regime Complex for Managing Global Cyber Activities,” mapping the formal and informal international organizations and governance structures that between them “governed” the global online environment, this paper takes a narrower view and focuses on the international cybersecurity governance regime, with the UN processes on cybersecurity and cybercrime at its core. Articles in the special issue contribute to putting pieces of this puzzle together, highlighting how multipolarity is shaping the cybersecurity regime (Barrinha & Turner, Citation2024; Raymond & Sherman, Citation2024) and the influential role of non-state actors shape governance narratives with their commercial and technical capabilities, as well as expertise (Shires, Citation2024; Wolff, Citation2024).

The birth of the cybersecurity regime: Competing state interests

The emergence of international cybersecurity governance mechanisms was undergirded by a cocktail of national self-interests—themselves the product of competing military, intelligence, and economic interests—and rising geopolitical tensions. As Barrinha and Turner (Citation2024) demonstrate in their contribution to this issue, strategic narratives put forward by major states in the cybersecurity regime have shaped its dynamics. At a fundamental level, there exists a contradiction between the two internet governance paradigms favored by the major powers: the first prioritizing sovereign control over information and territorial digital resources, and a second that seeks a strong role for states in securing digital infrastructure, but favors limited restrictions to communicate or transact on the internet (Barrinha & Renard, Citation2020). The tension between both priorities has not only made the creation of a formal cybersecurity treaty challenging, but attempts to reconcile competing interests within an overarching governance framework have contributed to the informal character of the overall regime. Based on their interests, influential states in cybersecurity governance can be classified into three groups.

The first group are the so-called, and self-labeled, “like-minded” states, led by the United States and European countries. This group has traditionally rejected formal treaties, speaks of “cybersecurity” rather than “information security,” and focuses on protecting the internet as an infrastructure. In the early years, the United States saw itself as a superior force in the cyber-domain and did not want to curtail its operational freedom and strategic advantages there or to foreclose the possibility of developing new offensive cyber-capabilities through binding rules (Arquila, Citation2021).

The second group comprise what we term the “other-minded” states, led by Russia and China, whose postures are mostly oppositional to the like-minded group. These states coalesce around the notion of cyber-sovereignty and stress the importance of information security, i.e., control of content, in the interest of domestic regime stability and continuity. These states are dissatisfied with the international order and exhibit various strands of revisionist tendencies, which we detail later in this section. The other-minded states have long sought a binding international cybersecurity treaty—primarily to constrain US and allied capabilities in this domain—and prefer for the UN to be the forum to negotiate this instrument. This goal has proven elusive for over two decades. Yet, far from withdrawing from multilateral cyber-governance efforts altogether, they have been proactive in creating new negotiation fora, setting agendas for interstate bargaining on cyber-issues and proposing new legal regimes.

The third group, the “swing states,” are a grouping only by default, as their characteristic is that they are not aligned with either of the other two groups. As a result, they are courted by both other groups and have rising powers in their ranks—like India, Brazil, and South Africa. These groupings, which are at best informal, all function against a background of rising geopolitical tensions which are fueled by military, economic, and intelligence developments in cyberspace and cyber conflict.

Rising geopolitical tensions and the shift towards a multipolar world have manifested themselves prominently in cyberspace. The fact that cyberspace became a new military domain of operations for many countries (Smeets, Citation2022) and a realm for routine intelligence activity (Rovner, Citation2023), has bred skepticism among states in UN negotiations regarding each other’s genuine intentions to foster rules of responsible state cyber behavior. While most states and academics do not find the term “cyberwar” analytically useful anymore (Rid, Citation2013), cyber conflict is widely accepted as part and parcel of modern statecraft. Discussions at the UN about the applicability of international law to cyber operations below the threshold of armed conflict, the militarization of cyberspace, and around standards of proof in the attribution of cyber incidents are all informed and constrained by complex operational realities—which include doctrinal innovations such as the American strategy of “defend forward” and “persistent engagement” (US Cyber Command, Citation2018), as well as by a lack of consensus about how to best classify cyber operations (as a phenomenon requiring new descriptors or as an intelligence contest), and what their legal and normative status is (Chesney & Smeets, Citation2023). The behavior of intelligence agencies—to which diplomats traditionally turn a blind eye—functions as the proverbial elephant in the UN rooms of negotiation, constraining big states, which want to maintain some strategic ambiguity, as well as small states, which heed the wishes of powerful allies (Broeders, Citation2023).

In recent years, the digital economy has also become an integral part of great power competition, especially between the US and China. These geo-economic tensions surface under political and policy frames such as “de-coupling” and the “Sino-US tech war” (Inkster, Citation2021) and also manifest in informal US pressure on allies on the Huawei presence in key 5G infrastructure and the informal coalition between the US, Japan, and the Netherlands to limit the transfer of semiconductor technology to China. Through its Belt and Road program, and especially the Digital Silk Road track, China in turn extends its global influence in the technology sphere. All of these developments influence and constrain debates at the UN.

How have interactions between the like-minded and other-minded states shaped governance regimes? On a general level, the emergence of a multipolar world, with China and Russia as major centers of power, has displaced the sole leadership of the United States in international institutions and negotiations, and given way to competing interests (Gibbons & Herzog, Citation2022, p. 51). Already in 2011, Schweller and Pu (Citation2011) argued that the world was entering a “delegitimation phase” which would see rising powers like China engage in discourses and practices of resistance, including supporting the creation of new international institutions, bolstering regional multilateralism, voting against the United States in existing institutions, and setting the agenda in negotiations (pp. 53–54).

With respect to cybersecurity governance, this tussle between both groups of states seeded informality in the regime. When in 1998 Russia started the UN debate on the weaponization of cyberspace and sought for regulation of “information weapons,” the like-minded group did not engage on the issue of a treaty for reasons already highlighted above. In addition, they saw Moscow’s framing of “information security” as an attempt to clamp down on free speech and the expression of human rights on the Internet (Maurer, Citation2020). Repeated Russian proposals at the UN General Assembly for a treaty were eventually negotiated down to an informal forum to simply “examine relevant international concepts” pertaining to ICT security (UN General Assembly, Citation2003).

The UN Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE) process convened six groups between 2004 and 2021. It gained maturity particularly around the time of widespread cyber-attacks in Estonia and Georgia and several cyber-incidents targeting the banking and energy sectors in the United States and Europe (Tiirmaa-Klaar, Citation2021). Four UN GGEs produced reports that were adopted by consensus within the group, and subsequently endorsed by the UN General Assembly. GGE reports are not binding on states, but have advanced international cybersecurity governance by developing what is commonly referred to as the “framework of responsible state behaviour” (Global Partners Digital, Citation2019). The core of this framework is a set of eleven non-binding “norms” relating to the protection of specific infrastructure or certain responsibilities of states in cyberspace, accompanied by text on Confidence Building Measures (CBMs), capacity building, and international cooperation. The GGE has also sought more recently to clarify the application of existing international law to state behavior in cyberspace (Broeders et al., Citation2022).

The creation of the GGE, which reflected thus a modus vivendi between the United States and Russia at the UN, supports partially the mainstream view in the literature on informal governance that states seek informal arrangements both for reasons of flexibility and as “low-cost institutions” to avoid binding commitments (Abbott & Faude, Citation2021). The creation of this informal group could also be considered as a way to kickstart cooperation within the then “empty institutionalized space” of cybersecurity governance (Westerwinter et al., Citation2021). Further, it bolsters recent claims made by international organizations scholars that informal governance arrangements are increasingly preferred in domains of “high politics” such as international security (Vabulas & Snidal, Citation2021).

However, these explanations do not quite address why Russia and China, both of whom have consistently sought cybersecurity treaties, engaged with the UN GGE if its guidelines were non-binding. If these other-minded states pursued a treaty primarily to impose constraints on the United States’ operational freedom in cyberspace, why did they support an informal mechanism? Russia has also advocated strongly for a cybercrime convention, which has served to bolster its relationship with China as well as garnering the support of a number of countries associated with the Non-Aligned Movement (UN General Assembly 3rd Committee, Citation2019). Neither Russia nor China are signatories to the Budapest Convention, the only global treaty on cybercrime at the time of writing. Indeed, in the domain of cybercrime, their efforts may be bearing fruition as an Ad Hoc Committee has entered, at the time of writing, the final stages of negotiating a global treaty.

One explanation is that Russia’s participation in informal cybersecurity governance is consistent with its longstanding, doctrinal view that the nature of multilateral commitments matters less in comparison to the overarching objective of promoting multipolarity in the post-Cold War world (Ambrosio, Citation2001; Stronski & Sokolsky, Citation2020). This strategy is evident in Moscow’s heavy reliance on informal agreements and summitry in the last two decades, which has also translated into its cyber diplomacy, especially at the regional level (Chernenko, Citation2018). As Kurowska puts it succinctly, Russia does not see norms as informal components of a broader regime around acceptable state behavior in cyberspace. Norms “regulate conduct” between states because they are negotiated by international institutions, who are ultimately “equalizers of liberal hegemony” (Kurowska, Citation2020, p. 93). The former lead Russian negotiator at the UN GGE has even argued that GGE norms are to be treated like formal rules, because “wine [was] judged by the drink, not the bottle it [was] poured into” (cited in Paltiel, Citation2022). The more (informal) institutions and norms there exist, goes the argument, the better the goal of multipolarity is served.

China, on the other hand, has been labeled a “bridging revisionist,” a state that seeks to produce radical changes to existing institutional order through a “rule-based revolution” (Goddard, Citation2018, pp. 765, 793). International institutions help Beijing to transform world order by enhancing its capacity to mobilize allies, generating more leverage in trade relationships, and augmenting its normative appeal (Goddard, Citation2022, p. 30). In cyber institutions, it has indeed focused on these normative aspects, generating support from third states for its conceptualization of “cyber-sovereignty,” centered on transferring more power to sovereign states in internet governance (Bozhkov, Citation2020, p. 16). Certainly, China finds common cause with Russia in seeking to prevent the US unilaterally set benchmarks for responsible state behavior—for instance, through its attribution of cyber-attacks to certain actors (Chuanying, Citation2022)—but appreciates more that informal norms are as important substantively as binding rules in shaping the framework of future governance in this regime (Huang, Citation2012).

The third group of states, the swing states, including emerging economies like India, Indonesia, and South Africa, are able to choose which side they support in individual negotiations and play the powers off against each other (Basu et al., Citation2021; Maurer & Morgus, Citation2014). For swing states, such inconsistent behavior is not without risks: it can undermine their international credibility and, in the long-term, damage their abilities to form alliances (Öniş & Kutlay, Citation2017). However, there is also not always a reason to choose sides. The fact that the UN General Assembly voted for both a new UN GGE and for an OEWG can be interpreted as the desire of many states to not rock the boat with either camp. This third group of states therefore plays a delicate game of balancing short-term interests with long-term strategies, involving predictions of how global international order will evolve and how new technologies will affect their own interests.

Non-state actors, multistakeholder cyber diplomacy, and informal governance

The role of non-state actors in modern global governance is hardly a new topic of analysis. There is a robust and growing literature on multistakeholder governance frameworks (Andonova, Citation2017; Scholte, Citation2020)—especially in the field of environmental (Pattberg & Widerberg, Citation2015), financial (Büthe & Mattli, Citation2011), health (Berman & Pauwelyn, Citation2022) and internet governance (DeNardis, Citation2014; Mueller, Citation2010)—as well as regime complexity induced by the participation of non-state actors in these frameworks (Barnett et al., Citation2021). On issues pertaining to international security, such scholarship is more recent still (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2009; Reykers et al., Citation2023), and only beginning to see theoretical and empirical advancements, notably in the field of private military and security services, maritime security (Bueger, Citation2018) and, pertinently to this paper, in physical cybersecurity infrastructure (Bueger & Liebetrau, Citation2023). The research agenda of this literature is framed largely around the composition of private actors in a regime, various plausible configurations of multistakeholder arrangements and functional reasons for those configurations to manifest within a regime. These are critical questions, essential to understanding the popularity of multistakeholder entities and, more broadly, public-private partnerships in global governance.

We can discern two broad categories of non-state actors who contribute to international cybersecurity governance: those that engage actively in cyber diplomacy via multistakeholder and intergovernmental institutions, and another set of actors who do not prefer such engagement and opt instead to pursue the development of a de facto governance regime largely through technical standards. To be sure, the first group is also involved in the development of technical standards, but it engages in diplomacy to ensure that global governance outcomes are closely aligned or at least not inimical to the development of those standards.

Standard-setting and informal cybersecurity governance

The commercial and operational needs of private actors who own or manage critical internet resources have long influenced international cybersecurity governance. The “Crypto Wars” of the 1990s provide an early instance of companies and civil society coalitions bandying together against the imposition by the US government of export controls to “slow the [global] deployment” of encryption technology (Landau, Citation2022, p. 26). Debates on US export controls took place alongside discussions on the Budapest Convention, the only formal instrument to regulate international cybercrime. As James Shires notes in this special issue, several US experts who helped create the Budapest Convention hailed from a law enforcement background, but were “technically-minded” (Shires, Citation2024) and did not support attempts to regulate encryption through this instrument (Council of Europe, Citation2022).

The influence of non-state actors over formal discussions on cybercrime spilled over into the informal international cybersecurity regime almost a decade later. In 2013, when signatories to the Wassenaar Arrangement—a non-binding export control regime for sensitive technologies—included a broadly phrased restriction on the export of “intrusion software,” companies and security researchers were able to successfully convince states that the catch-all definition impeded legitimate needs such as patching, sandboxing, and penetration testing (Bratus et al., Citation2014; Hinck, Citation2018). As a result, exemptions were introduced four years later to the definition of “intrusion software” which acknowledged the legitimate needs of cybersecurity research.

Then there is the influence of technical standards relating to internet governance, aspects of which overlap with cybersecurity concerns raised by states and non-state actors (Mueller, Citation2017). The technical community has been resistant to the notion that internet standards which underpin the security of the Domain Name System and, more broadly, network architecture and protocols, should be the remit of international cybersecurity negotiations. The 2012 World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT-12) was a watershed moment in this debate and saw a number of states proposing to bring internet routing, naming and certain protocol development functions under the ambit of the legally binding International Telecommunication Regulations (ITRs) with profound consequences for the security of national and global digital networks. In large measure due to resistance from technology companies and internet standards bodies, almost all of these proposals were watered down, and most like-minded countries did not sign the 2012 ITRs (Internet Society, Citation2012; Kiss, Citation2012).

Over the years, the delivery of internet services has consolidated and centralized significantly: the lion’s share of global routing and resolution done today is through a cluster of private companies (Radu & Hausding, Citation2020). Similarly, cloud services relied upon by public and private services are increasingly done by a small group of service providers such as Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, Cloudflare, VMWare, Alibaba Cloud and others (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Citation2022). These actors set security policies and terms of use that have emerged as de facto standards for application layer- and end-user cybersecurity. Formal intergovernmental cooperation is not foreclosed by the presence of various such standards, but challenges in harmonizing the policies of multinational companies are likely to sustain informality in this domain. States are much more likely to encourage private and public actors to build cybersecurity capacity or develop CBMs that correspond to existing corporate policies—and in some cases, articulate norms to guide their future development—than create rules that impose obligations on those actors.

Cybersecurity standards developed by private actors are not limited to technical ones. As Josephine Wolff (Citation2024) notes in this special issue, insurance companies are playing a quiet but influential role in shaping cybersecurity norms around conflict. Insurers like Lloyd’s, writes Wolff, have excluded state-backed and wartime cyber operations from their coverage. Since policy precision is important to determining coverage, the Lloyd’s Market Association (LMA) has even defined through its working groups what constitutes a “cyber operation,” what it means for such an operation to be “carried out as part of a war,” and what impact those operations must have to be excluded from coverage. The LMA’s clauses also suggest that attribution statements by states of cyber operations have to be considered by insurers and insured entities in determining what is a “state-backed” activity, and thus excluded from coverage. These benchmarks may not be binding, as Wolff notes, but they certainly have serious commercial consequences attached to them. Insurance policies could prompt states to address or even adopt said standards to mitigate political risk or capital flight from their digital economies.

The issue of attributing cyber operations highlights also the impact of a set of private actors who operate in the gray zone of cyber diplomacy, namely, those entities that make attribution claims or verify those by states, but who are themselves not involved in the frontlines of governance discussions or negotiations. Attribution statements and reports offered by cybersecurity companies such as Crowdstrike, Mandiant, and Recorded Future—driven largely by technical analysis and threat patterns—have been influential in shaping geopolitical narratives and indeed, discussions on norms. The US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) routinely issues attribution and advisory statements based at least partly on data obtained by these companies; for example, in 2022, CISA’s assessment of malware used in the Russian invasion of Ukraine was based on reporting by Microsoft and SentinelOne (CISA, Citation2022). While the most prominent actors in this space are arguably based in the US, UK, or Europe, other states have begun to acknowledge the legitimacy gains of multistakeholder attribution. For instance, the Chinese company Qihoo 360 was a partner in an attribution statement put out by China in 2022, pointing fingers at the US National Security Agency for targeting a reputed technical university in the country (Zhang & Creemers, Citation2023).

Finally, some technology companies have also expressed their willingness to operate in geopolitically unstable environments and even in belligerent territory, notwithstanding the commercial and security risks associated with such operations. Already in the early stages of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Microsoft detected a new wiper malware—named “FoxBlade”—and instantly alerted Ukrainian authorities, Washington D.C., and other NATO allies to coordinate with them in limiting its impact (Sanger et al., Citation2022). Since then, private companies have been integral to Ukraine’s digital war effort. Amazon, Cloudflare, Google, and Microsoft have migrated government data and operations into distributed cloud servers, helped protect government networks through automated solutions, and shared their telemetry promptly to stem the impact of wiper attacks (Pell, Citation2022).

The rise of multistakeholder cyber diplomacy

The second manner in which private actors have contributed to international cybersecurity governance is through their involvement in multistakeholder and intergovernmental cyber-diplomatic processes. At the UN GGE and OEWG, as well as prominent multistakeholder initiatives such as the GCSC and Paris Call Working Groups, technology companies, NGOs and cybersecurity experts have emerged as influential interlocutors.

The Global Conference on Cyber Space (GCCS) in London in 2011—which kickstarted the “London Process” discussions on cybersecurity governance—arguably offered the first global, multistakeholder forum for private actors to weigh in on international cybersecurity. Both in terms of its substantive agenda as well as timing, the GCCS coincided with the work of the first successful UN GGE (2009–10), introducing private actors to UN negotiations on international cybersecurity. Most importantly, the GCCS signaled to private actors that informal governance was the way forward in this domain. The communique of the London conference read (London Conference on Cyberspace: Chair’s Statement, Citation2011): “There was no appetite at this stage to expend effort on legally-binding international instruments.” In 2012 the GCCS moved to Budapest, where it introduced private actors to geopolitical currents, and to the complexity and highly fragmented character of the cybersecurity regime (Kleinwachter, Citation2012).

As previous sections have noted, the 2012–13 UN GGE report recognized the application of international law to state behavior in this domain, while leaving its precise contours open. Prior to the final stages of the UN GGE negotiations, Microsoft attempted to influence the group’s outcomes through its own report titled “Five Principles for Shaping Cybersecurity Norms” (Microsoft, Citation2013). Extensively quoting the GGE’s own work and other initiatives, Microsoft sought to highlight certain principles as relevant to responsible state behavior. These principles—for e.g., risk reduction, transparency, collaboration, etc.—were primarily business-centric, but the report also drew on existing legal principles to defend them. Interestingly, the report also endorsed informality in international cybersecurity governance, by drawing on analogies from other informal agreements.

Unlike the historical evolution of international norms, the development of “cybersecurity norms” should engage the private sector, which creates and operates most of the infrastructure that underpins the Internet. While it is true that only nation states can create actual legal norms, a challenging aspect of the cybersecurity discussion is that a significant portion of the infrastructure of the Internet resides in the private sector.[…] The private sector influenced such agreements as the Missile Technology Control Regime, Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering efforts, and the norms promoted by the International Civil Aviation Organization for civil air travel. (Microsoft, Citation2013, p. 7)

While private and multistakeholder initiatives were always active in the cybersecurity regime, the failure of the fifth UN GGE catalyzed their creation, and rise to prominence. The group’s inability to produce a consensus report prompted the Netherlands and French governments to promote, with the support of private actors such as Microsoft, Internet Society, and other companies and NGOs, the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace and Paris Call initiatives respectively. The work of both initiatives have been analyzed extensively (Ruhl et al., Citation2020). These multistakeholder initiatives were designed less to supplant the UN negotiations than to advance the governance agenda in the interim. As ‘placeholder’ initiatives, they continued to articulate new norms of responsible state behavior, deepening regime informality.

Similarly, multistakeholder initiatives have mushroomed in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, with states, companies, and NGOs taking advantage of the rapid adoption of online meetings to bring together stakeholders from diverse geographies. At least three multistakeholder or private initiatives directly addressed the substantive agenda of the sixth UN GGE and 2019–2021 OEWG: “Let’s Talk Cyber,” an initiative supported by Australia, Canada, EU Cyber Direct, and Microsoft, among others, with an express goal to gather inputs from a broader set of stakeholders for the UN OEWG report (Let’s Talk Cyber, Citation2023); “Community Talks on Cyber Diplomacy,” a series of interactive seminars organized by the Russian cybersecurity company Kaspersky also to address topics before the OEWG (Community Talks on Cyber Diplomacy, Citation2021); and finally, the Working Groups of the Paris Call, which were jointly chaired by companies, technical experts, and NGOs and set up to clarify or elaborate the norms articulated in 2018 by the Call itself (Paris Call, Citation2021).

In some cases, these initiatives have modestly influenced UN negotiations towards greater private participation. The start of the second UN OEWG (2021–2025) saw non-state actors petitioning the group’s Chair for more “meaningful participation.” Through an open letter, more than 100 civil society organizations and individuals sought transparency in how decisions to include NGOs that were not already accredited with the UN Economic and Social Council were made by the OEWG (Multi-Stakeholder Letter for OEWG Chair on Modalities, Citation2022). In the first OEWG, any state could object to the participation of an NGO as an observer, and offer no reasons for its decision. After much debate, the chair of the OEWG in 2022 issued new “modalities” of participation that requested states to “utilize the non-objection mechanism judiciously, bearing in mind the spirit of inclusivity.” States were asked to offer on “a voluntary basis, […] the general nature of [their] objections” (Gafoor, Citation2022). The “Let’s Talk Cyber” community of NGOs not only played an important role in marshaling support for the letter, but also kept stakeholders informed about decisions by specific states to reject the participation of private actors (Ravaioli, Citation2021). States still can veto private participation in the OEWG, but multistakeholder diplomacy has made them more accountable through a naming and shaming process (Johnstone et al., Citation2023).

The increased influence of non-state actors on international cybersecurity governance presents states with opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, it is evident that some private companies and civil society organizations have embraced informal governance with enthusiasm—in the next section, we identify some reasons why this has been the case—and packaged their proposals to states also in the form of non-binding norms. For states invested in the UN negotiations’ success, the engagement of private actors with epistemic authority, popular appeal, and expertise lends legitimacy to those informal discussions (Buchanan & Keohane, Citation2006; Zürn, Citation2018). This is especially true for the UN GGE, whose small size and exclusive membership has invited criticism. At least in the short term, perceived legitimacy is important for UN negotiations to sustain interest and attract resources from among various actors involved in cybersecurity governance (Bes et al., Citation2019).

The issue of legitimacy is only one element of the “governor’s dilemma” that states face with respect to multistakeholder involvement in international cybersecurity governance (Abbott et al., Citation2020). On the one hand, states have an incentive to promote the participation of competent actors in cybersecurity regime creation—especially private companies who have first-hand knowledge of cybersecurity issues—when private interests align with their own economic or military concerns. This includes not only the like-minded countries who are admittedly more enthusiastic about private involvement in the regime but also the other-minded states Russia and China who have to varying degrees orchestrated their own multistakeholder initiatives (Sukumar, Citation2023). On the other, the instrumental use or reliance of private diplomacy by states has sharp limits. Co-opting private diplomacy to suit their agenda or promoting only a certain constituency of private actors (say, from the Global North) can diminish the legitimacy of states’ efforts at promoting multistakeholder governance (Jongen & Scholte, Citation2021; Taggart & Abraham, Citation2023).

It is also likely that highly competent NGOs and companies capable of projecting their interests effectively and articulately may not always listen to states, including ones in which they are based or incorporated. Microsoft’s cyber diplomacy, which has been extensively analyzed (Hurel & Cruz Lobato, Citation2020), illustrates well the “competence-control” dilemma (Abbott et al., Citation2020). Having started out as a player who advocated “principles for cybersecurity norms” in 2013—aligning therefore with the like-minded group’s position that existing law was sufficient to govern state behavior—the company called for a “Digital Geneva Convention” in 2017 (Smith, Citation2017). The timing of the declaration was as significant as Microsoft’s apparent contradiction of a key tenet of US cyber diplomacy: the UN GGE negotiations in 2017 were politically fraught, occurring as they did in the backdrop of Russian cyber-enabled interference in the 2016 US presidential elections. Microsoft’s declaration reflected its view that “new and binding rules,” per contra informal governance, were required given the “rise in nation-state cyber-attacks” over the years. While the US disagrees with this stance, it has gradually reconciled with Microsoft over the years, signing the Microsoft- and France-orchestrated Paris Call in 2021 and including the company in its delegation to the 2019–2021 UN OEWG. This dilemma faced by the world’s pre-eminent cyber-power—whether to facilitate or oppose the cyber diplomacy of a leading technology company invested in cybersecurity—is likely to be shared by other states as well.

Mapping the international cybersecurity governance regime

In , we offer a conceptual mapping of the international cybersecurity regime that highlights the main actors by their roles and functions. Most, if not all, actors involved in the regime have already been reviewed in the preceding sections. The regime is organized around three semi-overlapping tiers, distributed across two wings. These wings represent the banner shifts responsible for the forward movement and evolution of the informal cybersecurity regime: geopolitics and the increasing influence of non-state actors in cyberspace, often through their influence on the cyber diplomatic corps. The core of the regime are the UN negotiations. The GGE and OEWG are classified as informal institutions, while the AHC, as noted previously, is characterized as semi-formal owing to its clear mandate as the source for a future cybercrime treaty. The PoA is also in the realm of semi-formality given that it is envisaged as a permanent mechanism by UN member states, but whose outcomes may or may not be formal in nature.

The two wings of the regime interact with the circle of “cyber diplomacy,” which in turn shapes the discussions in the UN negotiations. Through the diplomatic circle, actors from the outer wings attempt to secure their interests, while being outside of formal diplomatic negotiations. Within the geopolitical wing, there is an outer tier of actors who stay mostly outside the realm of cyber diplomacy, but in practice exert substantial influence on the negotiations. Military cyber operations and new doctrine, the increased geo-economic competition in the digital domain, and cyber operations below the threshold of armed conflict, which are often the domain of intelligence agencies, all shape the playing field for the diplomatic corps in the negotiations—sometimes because diplomats need to take the military, economic and intelligence interests of their own country into account and sometimes because state behavior simply shapes the context of the negotiations.

The middle tier within this wing comprises informal groups of “like-minded,” “other-minded,” and swing states which engage in cyber diplomacy, and coordinate positions and strategies, albeit to very different degrees. Non-state actors, represented in the middle tier of the other wing, engage with diplomats through multistakeholder forums, where they are influential participants and active interlocutors, or intergovernmental forums where their participation is usually limited to observation or written inputs. States also differ substantially in the degree in which they welcome or reject non-state participation. In this middle tier of “cyber diplomacy,” the wings meet and sometimes intersect. For example, the like-minded states are generally in favor of multistakeholderism and engage more seriously with non-state actors, while the “other-minded” states have a strong preference to engage with strictly intergovernmental forums.

Finally, the outer tier of non-state actors include several constituencies that have significant power in shaping cybersecurity governance—corporations, the technical standards community, and NGOs/ coalitions—often by creating the facts on the ground that states will have to contend with. Some actors out of these constituencies are actively engaged with the discussion, while others either seek to remain away from governance discussions for fear of capture or altogether mistrust states.

The persistence of informality in the cybersecurity governance regime

The preceding sections of this paper sought to identify reasons why nation-states and private actors turned to informal mechanisms to advance international cybersecurity governance. We noted how geopolitical tensions have stymied prospects for an international cybersecurity treaty, but that the like-minded and other-minded countries in particular have instrumental reasons to pursue informal dialogue at the UN. On the other hand, non-state actors have always been influential by dint of their ability to develop and set cybersecurity standards that serve as informal governance benchmarks in areas such as attribution and risk assessment. The previous section detailed how some private actors have begun to engage cyber diplomatic processes with a view to influence state positions. The informality of intergovernmental mechanisms has been advantageous to them because NGOs or companies can not only offer substantive governance proposals (which can be difficult in closed, formal treaty negotiations) to processes such as the UN GGE and OEWG, but also orchestrate private and multistakeholder coalitions of their own that, as highlights, become important components of the overall regime. The informal and non-hierarchical nature of cybersecurity regime implies, at least in principle, that a powerful, multistakeholder initiative, say with global technology companies and major cyber-powers, could be as influential as the UN GGE or OEWG.

Nevertheless, the entry of state and non-state actors into the informal cybersecurity regime is one thing, but their persisting with this regime is an altogether different matter. Simply put, why have powerful states persisted with the UN GGE and OEWG, or even orchestrated informal initiatives of their own? As this paper has already highlighted, the GGE is the longest running initiative of its kind in the history of UN expert groups. Why do civil society coalitions and companies—even Microsoft, which has called for a formal instrument in this domain, has been actively involved in cyber diplomacy—persist with their engagement, knowing well that states could renege on voluntary commitments any time? Indeed, anecdotal evidence would suggest that cyber operations have grown in severity and sophistication over the years, calling into question the effectiveness of UN or multistakeholder negotiations.

To study the persistence of informality in international cybersecurity governance, it is necessary to train one’s attention towards what these institutions do, as opposed to what they are. As emphasized earlier in this article, IR/IL scholarship of the previous decade has explored how the practices of global governance institutions—formal and informal—have shaped their agendas and generated shared understandings about key principles, norms, and rules (Adler-Nissen, Citation2014; Drieschova et al., Citation2022; Pouliot, Citation2008, Citation2021; Raymond, Citation2021). This scholarship shines light on how practices and governance mechanisms that are driven by such practices become sticky over time because they reflect and reinforce core strategic, economic or normative considerations relevant to various actors.

In the international cybersecurity domain, the persistence of informality is arguably owed to the reliance by states and non-state actors on a preferred tool of informal governance: norms of “responsible behaviour.”

Although these norms are described as “voluntary” or “non-binding” by the UN GGE and other institutions represented in , they are closely tied to international law. Cyber norms often borrow the vocabulary of international law (Delerue et al., Citation2020), implying they are not simply informal guidelines but also interpretations of existing rules as applicable to state behavior cyberspace (Johnstone & Sukumar, Citationforthcoming). This unique and somewhat self-contradictory formulation of norms is not accidental. Both like-minded and other-minded states have an interest in ensuring that informal norms hew closely to formal principles. The like-minded countries, consistent with their position that existing international law is sufficient to govern cyber operations, have in particular pushed for norms to adopt legal language. On the other hand, Russia and China may not be keen to affirm the applicability of existing law, but using formal language enhances the status of norms and UN GGE negotiations, and offers them flexibility to selectively assert certain (favorable) rules as applicable and adapted for cybersecurity governance.

Practices of the UN GGE have accordingly reflected the porous boundaries between informal norms and binding rules. All UN GGE reports since 2013 have contained a single section clubbing “norms, rules and principles” together (Lotrionte, Citation2022). UN negotiators frequently invoke the corpus of norms contained in these reports as the “acquis” of the GGE (Tiirmaa-Klaar, Citation2021) that should not be reopened or modified, suggesting that they have some precedential value, even if they do not legally bind the conduct of states. Through such practices that shape the “everyday” negotiations of the GGE, states signal to other actors in the regime that norms are not to be seen simply in isolation or in contrast to “hard” rules, but as tools in a “multi-level persuasion” strategy (Ratner, Citation2021). Norms not only reflect aspirational guidelines that states should follow in cyberspace, but also signal their “view of the contours of the law” (Ratner, Citation2021, p. 121).

Regional organizations where like-minded and other-minded states play an active role as well as private actors have articulated norms in a similar manner and tied them closely to international law. For instance, China, which has long sought norms around cyber-sovereignty at the UN GGE and other intergovernmental forums such as the BRICS and SCO (Creemers, Citation2020), was instrumental in the Asian-African Legal Consultative Organization setting up a working group on international law in cyberspace dedicated primarily to ascertain the contours of cyber-sovereignty (Gao, Citation2022). The other-minded countries have also resisted any attempt to disrupt longstanding practices that conflate norms and law. China and Russia rejected proposals by states to position a standalone section on existing international law in the 2019–2021 UN GGE and OEWG reports above the section on “norms, rules and principles” (China, Citation2021). Such practices linking informal and formal governance have also been adopted by multistakeholder initiatives. Certainly, it is possible that the fluid nature of cyber diplomacy, as represented in , has contributed to the adoption of UN practices by these initiatives.

“Multistakeholderism” is distinct from “intergovernmentalism” as a form of diplomacy, but several individuals have essayed key roles in both kinds of forums. Cyber-diplomats from various foreign ministries—considered the “pioneers” of UN GGE, and more generally, intergovernmental cybersecurity negotiations (Barrinha & Renard, Citation2017)—have gone on subsequently to occupy influential positions in think-tanks involved in Track 1.5 dialogues, multistakeholder commissions, and technology companies. These include diplomats from politically influential states like the US, Estonia, the Netherlands, Denmark, South Africa, Australia, and India. Their approach towards conflating (informal) norms and (formal) rules may have shaped the work of private initiatives as well. For instance, the GCSC (Citation2018) established detailed procedures of consultation, recruitment and outreach to ensure that international lawyers could help draft and vet some of the Commission’s nine, “voluntary” norms.

The Paris Call Working Group reports that clarify the scope of norms articulated by this multistakeholder initiative interspersed their commentaries on norms with legal-like memos on international law, implying that at least some of the norms have a connection to binding rules (Working Group 4, 2021). Some of these working groups also invited international lawyers to brief and contribute to their inputs (ICT4Peace, Citation2021). In sum, the UN GGE set a template for a bidirectional dialogue between “non-binding” norms and international law whereby norms would draw from existing rules, but also signal the modification of those rules through their context-specific application to state behavior in cyberspace. Other informal institutions in the cybersecurity regime followed suit, instituting their own practices that reinforced this ambiguous status of informal governance vis-à-vis formal rules.

Understanding the micro-mechanisms by which other institutions emulate the UN GGE’s approach to articulating norms is an agenda for future research. Caserta and Madsen (Citation2016) argue, for instance, that institutions involved in making and adjudicating rules are sites of “situated and bounded rationality” (p. 932) Over time, these institutions find ways to articulate “legal language with an inherent viability” (p. 932) that is sensitive to the relations between its various constituencies. Sometimes, these practices can be adopted in a tacit or subconscious manner (Pouliot, Citation2008)—“the UN GGE articulate norms in this manner, therefore we should too”—while in other instances, intergovernmental and multistakeholder institutions may be mimicking the UN GGE to conform to “social expectations” or be seen as influential and responsible actors (Goodman & Jinks, Citation2004). Given their inherent flexibility and non-binding, cyber-norms also become pilot tools for states and non-state actors to associate certain social expectations with interpretations of existing law (Brunnee & Toope, Citation2010). Where legal meaning sticks to certain norms, compliance is likely to be higher in the future, even if the precise character of those norms, strictly speaking, is informal. Arguably, this is what cyber-insurance companies are doing when they draft commercial clauses on cybersecurity that uses international law terminology. Obviously, commercial insurance policies not bind states, but their legal formulation invites the latter to pay attention to commercial and political risk implications (Wolff, Citation2024). All of these are theoretical avenues that invite empirical investigation, but requires research on informal institutions to go beyond structural aspects and engage with their substantive outcomes.

Studying the manner in which the UN GGE has advanced governance outcomes is also key to understanding the “focality” of UN negotiations in the regime. In informal regimes, several initiatives tend to “layer” around focal institutions at a “quick pace” given the flexibility of commitments (Hofmann & Yeo, Citation2023). But why do some emerge as focal points, if they do not bind the behavior of states in the first place? Any observer of the cybersecurity governance regime will come to the inescapable conclusion that the GGE is the pre-eminent forum around which such layering has occurred. An apparent explanation is that the presence of the Security Council’s five permanent members lends UN negotiations more legitimacy and effectiveness than others in the regime. While this may be true, the GGE’s failure in 2017 to arrive at a consensus report seems to have made little difference to its focality. Prominent state and non-state actors have continued their attempts to share future GGE agendas, particularly by advocating norms of their own that are grounded in international law (Broeders, Citation2021; Oxford Process Compendium, Citation2022). The UN GGE’s aligning of informal norms to existing rules has not only prompted other institutions to follow suit, but arguably enhanced its centrality to the overall regime. The cybersecurity governance regime illustrates how informal regimes that appear flat and non-hierarchical may nevertheless have strong focal points. Investigations into focality also need to cover inter-organizational relationships and their tools of governance (Gatti, Citation2023; Margulis, Citation2021).

Articles in the special issue

Articles in this issue touch upon various properties, actors, and institutions of the international cybersecurity regime, addressing in particular the two major themes that this article has highlighted as drivers of informality: the role of geopolitics and the diplomacy/ engagement of private actors in shaping the overall regime.

James Shires (Citation2024) highlights the role of an influential epistemic community of technical/ cybercrime experts in shaping the Budapest Convention (BC). In the cybersecurity context, technical standards and expertise have contributed to informality, but in the domain of cybercrime, as Shires points out, experts helped seed a formal governance regime. Many of these experts cut their teeth in government and/or non-profit sector, especially the US experts, some of whom were involved in the Internet’s early development. Formalizing the cybercrime regime involved making some compromises, in order to accommodate such expertise—specifically, the BC narrowed down definitions of computer crimes, excluded content crimes, and rejected regulation of encryption. The consequence of excluding content crimes from the BC, he argues, has been that regional organizations have included it in their own (formal) instruments. The result is that the cybercrime regime is today heavily fragmented, and this splintering of formal rules has complicated the quest for a universal cybercrime convention currently being negotiated in the UN.

Andre Barrinha and Rebecca Turner (Citation2024) explore whether the “compartmentalization” of the cybersecurity regime (into international cybersecurity, cybercrime, internet governance, development, etc.) corresponds to how states view it. Informal regimes allow for discursive flexibility—“strategic narratives”—allowing states to project themselves differently in different settings. For example, the like-minded can take a strong position on sovereignty in the UN GGE, but differentiate themselves from Russian and Chinese positions on the issue—China and Russia seek expansive control of internet resources, actors, and digital content on their territory—by resisting such proposals in the AHC negotiations. Conversely, discursive flexibility allows for states to emphasize different dimensions of the same concept/ strategy, argue the authors: for example, in the case of capacity building. In the OEWG, the EU has emphasized building capacity to implement cyber-norms—which includes monitoring territorial networks for malicious activity—but in the AHC, the EU’s focus is on building capacity to protect human rights, which mitigates somewhat concerns around rights violations through surveillance. Russian use of strategic narratives is evident in its position on multistakeholderism in the AHC per contra OEWG. In the OEWG, it opposes the involvement of non-state actors in the articulation of norms of responsible state behavior, but in the AHC, “Russia seems more eager to engage with non-state actors in the cyber-crime domain” (Barrinha & Turner, Citation2024). Finally, discursive flexibility allows swing states to pick and choose allies depending on issue areas discussed in various platforms, they note, facilitating a “multi-alignment” strategy.

Mark Raymond and Justin Sherman (Citation2024) study the emergence of “authoritarian multilateralism” (AML) in cybersecurity governance, which they frame as the exploitation of “existing procedural rules in multilateral institutions [by China and Russia] in ways that nudge them away from liberal multilateralism.” As the definition itself suggests, informal governance has facilitated the rise of AML. AML is different from liberal multilateralism in two ways. First, AML “tends to make broader allowances for great power privileges and special rights,” a feature the authors argue has fell out of fashion after 1945. Second, AML is characterized by a “rejection of the modern liberal notions of the moral purpose of the state [and] global governance,” including but not limited to the protection of human rights (Raymond & Sherman, Citation2024). “Social practices of rule-making and interpretation [are] central sites for power politics,” argue the authors, and not how the flexibility and fragmentation of the international cybersecurity regime provide ample opportunities for proponents of AML to advance their interests.

Josephine Wolff’s article (Citation2024) illustrates how insurance carriers have been setting de facto standards of governance around “allowable state-sponsored cyber-operations” through their policies. “Instead of pursuing formal engagement with a broad set of governments, [carriers] have begun to carve out specific types of state-backed cyber-activity that they will not cover under their standalone cyber-insurance policies,” argues Wolff. By defining what is acceptable risk and what’s not, these carriers force governments to act, either by protecting vulnerable infrastructure or underwriting cyber-risk themselves. Two possible outcomes from this scenario may be that first, cyber-insurance standards become templates for formal cooperation around the prevention and mitigation of state-sponsored attacks, and two, cyber-insurance carriers begin to play an active role in attribution of such cyber operations, a function usually considered the remit of the state. (She notes these are early days for either development to materialize). Wolff also notes that perceptions of risk evolve on account of cyber-insurance carriers engaged in standard-setting. Even if no cyber-operation thus far can be considered as having posed a systemic risk to the internet, insurance carriers through their policies can contribute to developing such notions at a commercial-operational level, and therefore at a political level.

Conclusion

As much as one tries to make sense of informality in cybersecurity governance, some developments are simply too complex or multifaceted to offer parsimonious explanations. The creation of the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on cybersecurity is one such instance. States reconvened at the UNGA in 2018 to establish the sixth GGE, but ended up voting also for a four-year OEWG whose substantive mandate overlapped almost exactly with the GGE (Broeders, Citation2021). Even veteran practitioners of cyber diplomacy have candidly acknowledged the creation of parallel processes as “nerve-wracking for states who wanted clear guidance from the UN” (Tiirmaa-Klaar, Citation2021, p. 9). At the time, it appeared states were voting for two informal processes simply because they could.

Another plausible explanation, whose various dimensions this article has sought to explore, is the persistence of informality in the regime. States and non-state actors certainly have incentives to enter the cybersecurity regime—the presence of informal institutions makes it possible for newer entrants to identify issue linkages and engage in forum shopping (Hofmann & Pawlak, Citation2023)—but we pointed out that informality has stuck to the overall regime, because of its close association with formal rules. Whether for strategic reasons or through the tacit reproduction of certain institutional practices, norms of responsible have become intertwined with discussions on international law. States could thus enhance the status of the framework of responsible behavior by endowing norms with legal vocabulary, while non-state actors have found this approach useful to initiate discussions on rules, for which they may not have many opportunities in formal negotiations. The 2019–2021 OEWG, as its report makes clear, has continued this approach to articulating norms. The parallel UN processes and their almost identical reports emphasize how states have become used to having “non-discussion” on lawful behavior in the guise of informal cooperation.

The persistence of informality is not necessarily a desirable outcome. There is much demand from states for a regular institutional dialogue and greater clarity on the “framework of responsible state behaviour” in cyberspace. The inclusion of the wider UN membership within the OEWG, allowed for a smaller coalition of 40 states, spearheaded by France and Egypt, to propose a Programme of Action on international cybersecurity. The PoA—which was approved by the UN GA in 2022, but whose terms and timeline are unclear at the time of writing—will be the first permanent mechanism within the cybersecurity regime. However, the PoA is likely to focus only on solidifying “political commitments” that have already been made at the UN (Géry & Delerue, Citation2020). In this regard, it is similar to the PoA on Small Arms and Light Weapons, a conference that has produced political and non-binding frameworks such as the International Tracing Instrument.