ABSTRACT

We bring nuance to the understanding of cleavages among states over the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). We measure the positions of the participants to the 2022 and 2023 TPNW Meetings of State Parties, employing text-as-data approaches. Our results show that the participants can be placed along a single axis, roughly associated with whether they view nuclear disarmament in an “old” way as primarily a security problem or in a “new” way as a humanitarian and emancipatory issue. We find that membership in a nuclear weapon-free zone—particularly in Latin America and Africa—has a statistically significant effect on state positions. We therefore debunk the idea that parties to the nuclear ban treaty are a coherent single block. Our article provides a new, quantitative way of measuring the positions of states vis-à-vis the TPNW and contributes to the emerging scholarship on the treaty.

Although opposed by the world’s most powerful states, and championed by but a motley crew of small and middle powers and non-governmental organizations, the Treaty on the Prohibition of the Nuclear Weapons (TPNW; United Nations, Citation2017) not only entered into force, but also held two Meetings of State Parties (MSP)—the first one in Vienna in June 2022, and the second in New York in November 2023. This normalization of the diplomatic process behind the “nuclear ban treaty” can be seen as the culmination of a decade-long endeavor to ban nuclear weapons on humanitarian grounds.Footnote1

The TPNW offers a novel approach to nuclear disarmament. Driven by the dissatisfaction with the discussions which led to arms control and arms limitations, but not to disarmament as such, it aims at banning nuclear weapons due to their sheer destructiveness and associated humanitarian effects (Borrie, Citation2014; Gibbons, Citation2018; Potter, Citation2017). The states that negotiated and later signed and ratified the TPNW were, primarily, concerned about the slow pace of nuclear disarmament which the nuclear weapons states committed to in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) (Considine, Citation2019).

This disappointment with the pace of nuclear disarmament, combined with the rise of the TPNW, has fed into an existing narrative of the “unraveling” or “collapse” of the NPT. Such arguments have been made frequently by academics (Doyle, Citation2017; Knopf, Citation2022; Pretorius & Sauer, Citation2021)Footnote2, activists (Acheson & Fihn, Citation2013), and policy-makers alike (Dhanapala & Duarte, Citation2015; Pilat, Citation2020)—even though counterfactual and quantitative empirical research has doubted such claims (Barnum & Lo, Citation2020; Bollfrass & Herzog, Citation2022; Horovitz, Citation2015).

Supporters and opponents of the TPNW like to lump the state parties into a single block which enjoys a certain coherence of views. For instance, Ambassador Alexander Kmentt, a leading force behind the treaty, makes a distinction between the “TPNW logic” and the “deterrence logic” (Reaching Critical Will, Citation2023, p. 7). Supporters of the treaty only capture formal steps such as participation in the meetings, as well as the treaty’s signature and ratification (Norwegian People’s Aid, Citation2024). However, the early reports from the conferences by expert observers cast doubts over such generalizations (Gibbons & Herzog, Citation2022; Kwong, Citation2022). Yet, until now, we lack a better measure of how states view the treaty. In this article, our goal is two-fold: to measure the variation of state views on the TPNW, and to explain such variation. To do so, we draw on the scholarship exploring how participation in international institutions influences state preferences. We expect that members in regional institutions focused on nuclear disarmament shape the positioning on the TPNW. Nuclear-weapon-free zones (NWFZs) are such institutions. Based on the existing scholarship, we expect that members of the same NWFZ will show a greater coherence of views on the nuclear ban treaty. Our results indicate that there are substantial differences in positions vis-à-vis the treaty among states participating in the TPNW MSPs, both with regards to state parties and observers. We reveal an “old” and a “new” way of thinking about nuclear disarmament, with the former focusing on security aspects and the latter on humanitarian aspects. Importantly, our findings demonstrate that participation in NWFZs shapes how states think about the TPNW. This effect is particularly strong in the case of more established and institutionalized NWFZs based on the treaties of Tlatelolco, covering Latin America (signed in 1967), and Pelindaba, covering Africa (signed in 1996).

We use Wordfish, an unsupervised text scaling method, to extract positions on the TPNW from the statements made during the MSPs in Vienna and New York (2022 and 2023).Footnote3 The major advantage of Wordfish is that it enables the locating of actors on an ideological dimension without any prior knowledge about the dimension itself (Slapin & Proksch, Citation2008). Our quantitative measure of state positions on the TPNW is not only fully replicable, but also mitigates potential biases involved in hand-coded measurements. This makes the measure a valuable contribution to the existing scholarship on the treaty. In addition, the article provides possible fertile ground for future analysis. As the TPNW is here to stay, and nuclear disarmament is becoming salient among policy practitioners as well as the general public, scholars and practitioners alike will be interested in understanding how the treaty regime changes and how the alignments of states within the treaty change. Our article offers a tool for that.

The remainder of the article continues as follows. In the first two sections, we review the existing scholarship on the TPNW and regional socialization, respectively. We then present the measure of state preferences on the treaty. Successively, we use this measure to test the impact of regional socialization against a series of alternative hypotheses. Finally, we discuss these findings in light of the existing literature, and then conclude.

Studying the TPNW

The TPNW grew out of the Humanitarian Initiative (HI), an initiative which was started by a number of middle powers in the mid-2010s to highlight the catastrophic humanitarian impact which the use of nuclear weapons would have. However, after the 2015 NPT Review Conference, the HI evolved from a mere initiative to an actual effort to ban nuclear weapons. This shift alienated many Western middle powers (such as the original sponsor, Norway), but strengthened the resolve of other states (Gibbons, Citation2018). It also led to a diplomatic process, at the end of which the TPNW was negotiated from 27 to 31 March 2017 and between 15 June to 7 July 2017 at the United Nations, by over 130 states but with the absence of all of the countries actually possessing nuclear weapons, and almost all of their allies (the Netherlands being the only exception).

The TPNW is, in many ways, very different from the NPT. It bans nuclear weapons comprehensively, thus not making a difference between nuclear weapons states and others. It prohibits the possession of the weapons, not only their proliferation. As opposed to the NPT, which was largely negotiated as a superpower deal (Brands, Citation2007; Coe & Vaynman, Citation2015; Popp, Citation2017), the TPNW was mainly negotiated by small and middle powers (Kmentt, Citation2021). While civil society organizations were not present when the NPT was negotiated, they were absolutely essential for the success of the nuclear ban treaty (Gibbons, Citation2018; Ritchie & Egeland, Citation2018). Because the treaty directly targets states possessing nuclear weapons, it is not a surprise that the nuclear weapons states according to the NPT have repeatedly attacked the treaty (UK Government, Citation2018). However, it has also received mostly negative responses from the allies of the United States in Europe and Asia, because the treaty targets also nuclear umbrellas.

Despite its relative recency, there has been no shortage of academic work on the TPNW. Much of the academic literature on the treaty is related to earlier scholarship on the HI, making the two bodies of work very closely connected. In his database of TPNW and HI writings, Nick Ritchie counts no fewer than 371 journal articles, 16 journal special issues, 145 books and book chapters, 174 NGO reports, and 96 event videos.Footnote4

Although it is too early to make a definitive systematic classification of the scholarship, one can tentatively observe two waves of academic work on the TPNW. These groups have emerged in a sequential manner (that is why we call them waves), but they continue to exist and develop simultaneously. With these caveats, the two waves can be largely summarized as (1) studying the HI, the humanitarian turn in nuclear disarmament and the emergence of the TPNW; and (2) perspectives on the TPNW as an existing instrument.

In the first wave, much of the work traced the emergence of the TPNW, primarily as a process driven by the small and medium powers dissatisfied with the pace of global nuclear disarmament (Potter, Citation2017; Ritchie, Citation2019; Ritchie & Egeland, Citation2018). The process itself was strongly supported by a coalition between civil society organizations and diplomats, and focused on redefining the debate on nuclear weapons from strategic questions to their humanitarian impact (Acheson, Citation2021; Fihn, Citation2017; Gibbons, Citation2018; Kmentt, Citation2021). In the process, the TPNW has contributed to the emancipation of hitherto silenced voices, including the victims of nuclear testing, the survivors of nuclear weapons use, and those whose livelihoods were destroyed in mining the materials for nuclear weapons.Footnote5

In this wave, there were also a few critical voices raising concerns about the humanitarian turn and the TPNW. Some critics argued that the treaty carries the potential to further the fissures within the NPT regime (Müller & Wunderlich, Citation2020; Williams, Citation2018), others stated that the TPNW had no realistic potential to deliver on nuclear disarmament (Egeland, Citation2019; Onderco, Citation2017), yet others claimed that the normative claim expressed by its supporters was weak (Vilmer, Citation2022), or that it was tone deaf to the contemporary security challenges (Gibbons & Herzog, Citation2023). The response to such criticism often argues that the NPT regime is either doing a fine business creating fissures itself (and does not need the TPNW’s help in doing so; see Knopf, Citation2022; Rublee & Wunderlich, Citation2022); that the ban treaty is not supposed to deliver on disarmament but rather to stigmatize the bomb (Ritchie, Citation2014); or that the return of conflict and contentious politics is not bad per se (Egeland, Citation2021). Some supporters also argued that finding the right approach to nuclear disarmament requires engaging with “ridiculous ideas” (Belcher, Citation2020, p. 325).Footnote6

More recently, a second wave developed, with multiple scholars examining how various actors approached the TPNW. Some, such as Egel & Ward (Citation2022) studied what prompted particularly the middle power to negotiate the treaty. Mathy (Citation2023) investigated the patterns of signature of the treaty and Futter and Samuel (Citationforthcoming) studied the preferences of states in the formation of the treaty. Scholars have also suggested that among European NATO members, despite their decision not to join the treaty, there are real and significant differences in approaches to the treaty (Meier & Vieluf, Citation2021; Onderco & Farrés Jiménez, Citation2021). In the recent Special Issue (SI) of the Peace Review (Bandarra & Martuscelli, Citation2024), scholars explored the perceptions of the TPNW across different global regions, including in Western Europe (Herrera, Citation2024; Sauer, Citation2024); the Balkans (Stefanović & Kostić Šulejić, Citation2024), South Asia (Mir & Nazir, Citation2024), the Middle East (Hassid, Citation2024), and Latin America (Duarte, Citation2024; Wittmann, Citation2024).

Similarly, the (somewhat slow) pace of the ratification of the treaty suggests that the treaty arouses different responses even among states who do not possess nuclear weapons or are not under nuclear umbrellas (Onderco, Citation2020). Even among the public, support for the treaty is not unanimous. Existing academic studies conducted in the United States (Herzog et al., Citation2021) and in the Netherlands (Onderco et al., Citation2021) showed divided publics which are often not eager to join the treaty immediately. However, this contrasts with the dynamic in Japan where the public is strongly in favor of the TPNW and almost impervious to policy arguments that oppose joining the TPNW (Baron et al., Citation2020).

While the SI of the Peace Review has started to address some of the global perspectives on the TPNW, the existing work is still nascent. Only a handful of the contributions in this SI, for instance, engaged with the behavior of states during the TPNW’s Meetings of State Parties (MSP). Part of the reason for this oversight is the fact that the first meeting of state parties to the TPNW took place only in June 2022 and the second one only in December 2023. Reports from the first MSP highlighted that the issue of how to react to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine divided the member states (Gibbons & Herzog, Citation2022; Kwong, Citation2022), but there is little known about other factors which animated the meeting.

For all of their contributions, the existing studies of state positions have suffered from the same flaw that Scott Sagan (Citation2011) identified in the broad nuclear debate almost fifteen years ago—the dominance of small-N studies leaving us with but a few generalizable lessons. Similarly, the dominance of qualitative studies means that the replicability of the findings is uncertain. In this article, we aim to offer a reliable and valid measure of state preferences which shall lead to findings generalizable beyond a few countries, by looking at the speeches made during the first two TPNW MSPs.

Regional institutions, state preferences and NWFZs

International relations scholarship has long recognized that participation in international institutions carries the potential to influence state preferences. While the foundational work in this field was carried out by constructivist scholarship (Checkel, Citation2005; Johnston, Citation2001; Kacowicz, Citation1998) and liberal internationalists (Ikenberry & Kupchan, Citation1990), more recent rationalist work has confirmed these findings, by showing that participation in various forms of international treaties has influence on state behavior (this literature is too numerous to review here in full, but some of the foundational work can be found in Bearce & Bondanella, Citation2007; Chelotti et al., Citation2022; Fuhrmann & Lupu, Citation2016; Gavras et al., Citation2022; Goodman & Jinks, Citation2013; Greenhill, Citation2010; Von Stein, Citation2005). As these scholars have demonstrated, international institutions can have a socialization effect on states. Through repeated interactions with partners, and through extended engagement, states develop a similar outlook on the world (for a detailed explanation of different potential pathways, see Checkel, Citation2016).

This work began by drawing on examples within Europe (Checkel, Citation2016 makes a similar argument and provides an overview) but was later expanded to include work on other regions of the world, including Southeast Asia (Acharya, Citation1997; Acharya & Johnston, Citation2007). Within the study of the European Union, the notion of “Europeanization” explicitly engages the socialization element and argues that even without institutional requirements or obligations, socialization tends to bring states together in how they look at the world (Hill & Wong, Citation2012; Wong & Hill, Citation2012). This work has also demonstrated that after joining the European Union, the preferences of states regarding issues not governed by the EU might change (Egel & Obermeier, Citation2022). As Johnston (Citation2003) argues, one of the major assumptions in this literature has been, for a long time, that socialization in Europe was linked to institutionalization. Whether it can happen without strong institutions was an open question. Subsequent scholarship, whether qualitative or quantitative (Checkel, Citation2005; Chelotti et al., Citation2022; Gavras et al., Citation2022; Gheciu, Citation2005), assumed that formal international organizations are required to create a socialization effect (Johnston, Citation2003). Later scholarship, particularly drawing on examples from South Asia, challenged this assumption, and instead posited that a high level of institutionalization is not strictly required for socialization (Acharya, Citation2011).

We borrow this perspective to study state preferences on the TPNW, and in particular to understand how participation in regional institutions influences them. We do not study how socialization in regional institutions occurs, but test the effect of socialization. To make our argument, we leverage on a particular instance of regional institutions in the nuclear field, the nuclear weapons-free-zones (NWFZs). NWFZs are by definition regional, and usually include countries which share certain foreign policy goals—such as prevention of nuclear proliferation in their region (for a recent comprehensive overview, see Lacovsky, Citation2021). Beyond the immediate goals, NWFZs are often established by states in pursuit of larger foreign policy goals. As Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh calls it, they represent an “obedient rebellion” against the existing structures of the international system (Mpofu-Walsh, Citation2020, p. 65ff). In practice, states often pursue them because they want to exclude or restrict hegemons in their region (Mpofu-Walsh, Citation2022; Rodriguez & Mendenhall, Citation2022).

At present, NWFZs cover the global commons (outer space, the seabed and Antarctica), as well as six inhabited areas: Latin America (Treaty of Tlatelolco), the South Pacific (Treaty of Rarotonga), Africa (Treaty of Pelindaba), Southeast Asia (Treaty of Bangkok), Central Asia (Treaty of Semei) and Mongolia. NWFZs might but do not have to be institutionalized. For instance, the Latin American NWFZ is institutionalized in the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL), which has all of the features of a formal international organization. Similarly, the African Commission on Nuclear Energy (AFCONE) serves to oversee the implementation of the Treaty of Pelindaba (Nuclear Threat Initiative, Citation2023a). By contrast, the Bangkok Treaty does not provide for any institutional setup, in line with the norms of informality prevailing in the region (Nuclear Threat Initiative, Citation2023b), though the ASEAN rotating presidency negotiates on behalf of the parties with the external actors (see, for instance, an example in Sarmiento & Jegho, Citation2023). The Treaty of Semei established no formal institutional structures. The Treaty of Rarotonga uses the services of the South Pacific Bureau for Economic Cooperation and can convene an ad-hoc Consultative Committee (South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty, Citation1985).

It is therefore expectable that participation in NWFZs influences the state preferences on nuclear disarmament more broadly. We do not expect that membership in the same NWFZ eradicates any differences among states, but we do expect that the states who are members of the same zone tend to exhibit more similar views.Footnote7 Furthermore, we expect that this effect is stronger in zones which are institutionalized.

The TPNW is a good candidate where we might observe the effect of socialization on states, and of their preferences on nuclear weapons. Even before the treaty was negotiated, one analyst saw it as “an informal unification of the five existing nuclear-weapon-free zones” (Brixey-Williams, Citation2017). It is sometimes portrayed by its proponents as “globaliz[ing] what nuclear-weapon-free zone treaties have done regionally” (Don't Bank on the Bomb, Citation2023). As one analyst argued, “[the TPNW] is popular in all the regions where nuclear weapons have been already rejected” (Maitre, Citation2022, p. 2). Regional patterns more broadly are relevant for the TPNW too. As Mathy (Citation2023) confirms, there is a strong regional dynamic when it comes to ratification of the TPNW; but that the normative concerns are trumped by security considerations. Yet, we expect that the state parties to the treaty have sufficiently varied preferences that they might differ by region, reflecting different regional dynamics, but also different security perceptions.

Measuring positions on the TPNW

We employ Wordfish, a text scaling algorithm, to extract the positions of countries on the TPNW as expressed during the meeting (Slapin & Proksch, Citation2008). In general, scaling methods are designed to infer the relative positions of political actors on a latent dimension on the basis of some manifested behavior. When texts are used as the source of data for scaling (rather than votes, for example), we assume that the choice of some words and not others is revealing about the stance of the actors.

Wordfish is an unsupervised method of Text as Data as it does not require any substantial input from the researcher.Footnote8 In fact, it presumes that the occurrence of the words across documents is drawn from a Poisson distribution, combining a parameter capturing the importance of a word distinguishing between documents with another one representing the latent dimension, conditioned by document and feature fixed effects. To put it simply, Wordfish autonomously identifies the latent dimension and locates actors on it depending on how words are used across texts: the more a word is used in a heterogenous manner, the more it contributes to discriminate between the positions of the actors. On this aspect, Wordfish distinguishes itself from supervised scaling methods such as Wordscores that require the researcher to define the dimension through the selection of reference texts (Laver et al., Citation2003).Footnote9

We decided to use Wordfish over Wordscores to extract positions on the TPNW as the literature suggests that there is little disagreement among participants to the treaty, and consequently, we could not rely on any established reference to establish the polarities of the dimension. Indeed, our aim consists of investigating the presence of a cleavage regarding the treaty. Wordfish enables us to pursue it without having to impose any form of prior expectation about the nature of the cleavage and who is on one side and who is on the other. One limitation of such methods lies in locating actors on only one dimension, thereby reducing the complexity and nuances of conflicts between them. This might be a problem in contexts where the ideological cleavage is multifaceted. However, this is not our cases as scholarship argues that the TPNW is essentially driven by a single issue: banning nuclear weapons on humanitarian grounds (Docherty, Citation2018; Ruzicka, Citation2019).

As a first step in our analysis, we collected all the country statements made during the first and the second TPNW MSPs (the first MSP took place in Vienna on 21–23 June 2022; the second MSP took place in New York on 27 November to 1 December 2023). We downloaded most of the texts from the official United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) webpage and translated them into English when statements were originally made in other languages. The remaining speeches for which the text was unavailable were retrieved by transcribing the video recording of the meeting (available only in English using the official UN translation). In total, we collected 130 statements: 62 from the first MSP, and 68 from the second MSP, 124 of them made by states. The remaining six statements were made by representatives of two international organizations (the aforementioned AFCONE and OPANAL) and two nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) and Mayors for Peace).

We then pre-processed the documents, by removing numbers and punctuation, transforming all letters to lowercase, deleting very common words in the English language such as articles and prepositions (known as “stopwords”). Moreover, we generated single tokens for a series of relevant multiple-word concepts such as “nuclear weapons” and “nuclear deterrence.” In a number of such cases like “Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons” and “Non-Proliferation Treaty,” we also merged the full name and the respective acronym into a single token. Finally, we dropped all those words that do not occur in at least 10 percent of the documents.Footnote10 The aim of these procedures is to reduce the amount of non-informative or redundant features in the matrix and increase the homogeneity of the documents. In fact, if on one hand Wordfish requires a certain extent of ideological polarization across texts, on the other hand its performance tends to worsen when the level of linguistic heterogeneity becomes too high (Egerod & Klemmensen, Citation2020). The reason is that the algorithm struggles to reconcile all of the different topics into a single dimension and distinguishes documents in clusters associated with such topics. In our specific context, it was relevant for instance to remove as many words as possible associated with individual speakers such as names of respective states or capitals that may bias our analysis. To sum up, such pre-processing steps were conceived in order to better uncover a latent dimension reflecting the disagreements among actors over the treaty.Footnote11

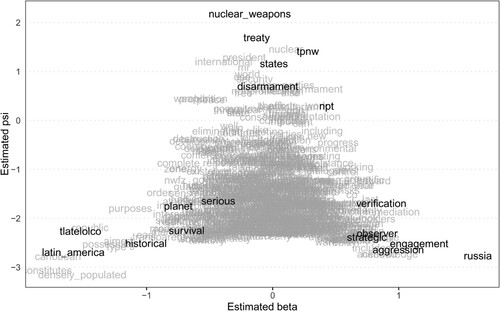

As a first step in our analysis, we validate the latent dimension identified by Wordfish, by looking at the most (and least) discriminating words and their meanings with respect to the debate over the TPNW. reports all the words considered in the estimation of relative positions according to their values attributed by the algorithm on two parameters: the value for the psi parameter, measuring the homogeneity of word occurrence across documents, and the value for the beta parameter, measuring the heterogeneity of word occurrence across documents. To simplify, words with a larger psi parameter are the most used throughout all documents, while words with more negative or positive beta parameters are the ones most used in a cluster of documents but not in another one.Footnote12 Given that the algorithm assumes that most polarizing words are also used heterogeneously across documents, words with more extreme (negative or positive) beta values tend to have smaller psi values and vice versa. The more extreme the beta parameter attributed to a word is, the more that word contributes to discriminate the position of one actor on one side or another.

At the peak of this Eiffel-Tower-shaped plot, with large psi scores, and close to zero beta scores, “nuclear_weapons” and “treaty” and “tpnw” figure prominently. All delegations spoke of nuclear weapons and the treaty, and hence their presence is not surprising. Words such as “states” and “disarma(ment)” predictably are also attributed a large psi score. We find two main clusters among the words with the lowest beta scores, contributing to placing actors on the negative side of the latent dimension. One relates to the Treaty of Tlatelolco (“tlatelolco,” “latin_america”), which is to be expected given the profound impact that the Treaty of Tlatelolco had on nuclear identities in Latin America, as the first treaty establishing a nuclear free zone in a populated area (Rodriguez & Mendenhall, Citation2022). The other one relates to humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons, and particularly links to perceiving the nuclear weapons in a global context (“planet,” “serious,” “survival”). There is also the word “historical,” which links the debates to the past harm done. The presence of “russia” and “aggression” among words with the highest beta scores highlights the importance of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the TPNW MSPs. Scholars have by now indicated how the dispute over whether the conference should condemn the Russian invasion or not dominated the discussions in the meeting back rooms (Gibbons & Herzog, Citation2022; Kwong, Citation2022). We see this also in our corpus. Of 70 mentions of Russia between the two MSPs, 23 were made by Germany and 10 by Norway, two observers in the conference. By contrast, in Africa, only two countries mentioned Russia in the MSP setting (and one of which, Equatorial Guinea, only by enumerating the list of nuclear weapons states). In Latin America, only Ecuador, Guatemala and Costa Rica ever mentioned Russia; and Costa Rica only in the context of the CTBT de-ratification. Most of the mentions of Russia came from European countries, clearly underscoring the security dimension of nuclear disarmament.

However, we also show that the Russian war in Ukraine was not the only polarizing issue. Other top discriminating words on the positive end of the dimensions suggest the connection of the TPNW with other elements of the nuclear regime, including the NPT (“npt”), the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons (“verification”) or constructive engagement with these elements (“engagement”). The participation of non-members (“observer”) was also somewhat polarizing. The word “strategic,” linked to the traditional understanding of weapons as serving a role in security, is also associated with positive beta values.

We interpret this scale as measuring the gap between a “new” and an “old” way of understanding nuclear disarmament—the “old” way of seeing it as a security issue and a part of the existing diplomatic structure; and the “new” way of seeing it through the prism of humanitarian costs and the emancipation of peoples. The TPNW is a strong example of this “new” way of thinking about nuclear disarmament.

Some of the terms are found in unexpected, counterintuitive places. This is because for the method, who says what matters. The word “Russia” which we discussed previously, is a good example. Another example could be found in the word “remediation.” One could expect the word “remediation” to be associated with the “new” understanding of nuclear disarmament, as attention to the victims of nuclear testing is at the core of the humanitarian perspective. However, in our model, it is found on the positive (“old”) side of the axis because in the TPNW setting, European countries speak more about this issue than other regions (with the exception of the countries which were themselves victims of testing, such as Kiribati, Kazakhstan, or Samoa). For instance, Germany in 2023 alone mentioned remediation as many times as all African or Latin American countries at both conferences combined. The fact that Germany uses this word the most frequently of all states makes the word load with the “old” way of thinking about disarmament, because Germany also uses other words which associate with the “old” dimension. This is a feature of the method—it occasionally offers counter-intuitive findings, because sometimes the pattern of speeches by states is counterintuitive.

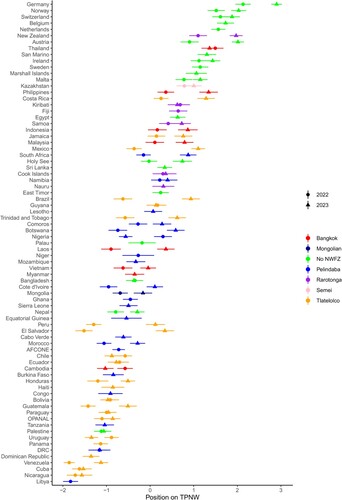

We now examine the positions generated by these scores, assessing their validity against prior knowledge about cleavages over the TPNW and, more generally, nuclear disarmament. describes the positions of the participants at the MSPs as extracted with Wordfish and their respective measures of uncertainty.Footnote13 Countries have differently colored markers, based on which NWFZ they ratified (or none) and different shapes according to the MSP in which the statement was made.Footnote14

On the right-most end, we see countries which tend to see nuclear disarmament in a more conservative light. If we see the TPNW as a reformulation of nuclear disarmament from a security problem to a humanitarian problem (Bolton & Minor, Citation2016), then the more “conservative” end is the one which still sees nuclear disarmament as a security problem, and therefore pays more attention to issues such as verification, or the broader security environment (hence the mentions of “Russia” in the context of the war in Ukraine). On this end, associated with a more conservative approach to nuclear disarmament, we see countries which are either NATO members (the Netherlands, Germany, and Norway), Sweden, a country which at the time was an applicant for NATO membership, and Switzerland, a country which helped negotiate the TPNW but ultimately placed cooperation with NATO countries above TPNW membership (Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Citation2018). Importantly, all five of these countries would consider themselves as important voices in the nuclear disarmament debate, and all of them contribute to diverse initiatives to advance nuclear disarmament—just not the TPNW. They all attended the MSP as observers, not as members. These findings highlight that participation of countries like Germany does bring a different perspective into the TPNW debate, and the message which these countries bring to this forum is different from that brought by others. At this side of the spectrum, albeit with slightly less positive scores, we also observe Ireland and Austria, two member states of the European Union (EU), as well as New Zealand and Thailand, regional champions of nuclear disarmament.

At the other end of the scale, the one linked to a more innovative and humanitarian approach to the treaty, we find countries such as Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba, which are united by their “revolutionary” (and anti-American) views. In the middle, we observe countries such as the Holy See, and South Africa (the traditional bridge-builder in the nuclear realm). In fact, South Africa’s statement to the conference echoed strongly the statement delivered by Alfred Nzo at the 1995 NPT Review and Extension conference (Nzo, Citation1995), where South Africa played a key bridge-building role (Onderco, Citation2021). We also observe Kazakhstan here, a country which gave up the nuclear weapons it inherited from the Soviet Union and where the population still continues to suffer from the consequences of nuclear testing (Kassenova, Citation2022), but which is also part of many frameworks seen critically in the Global South, such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group, and the Additional Protocol. In addition, shows that, between the first and the second MSP, most countries moved toward the positive end of the scale, associated with the “older” understanding of nuclear disarmament. However, it is worth pointing out that the difference of the mean position of all participants at the two meetings is not statistically significant. To sum up, our findings show that even among the parties to the TPNW MSP, there is a variation in how they view nuclear disarmament. When organized along a line, we can interpret this line as a spectrum between a “new” and “old” approach to nuclear disarmament, with the former focusing on humanitarian aspects and emancipation, and the latter focusing on security problems and diplomatic structures.Footnote15

To reiterate again, Wordfish uncovers latent dimensions, which therefore did not allow us to formulate a directional hypothesis prior to the estimation of the dimension(s). However, armed with the knowledge that the positions of states can be roughly placed on the “new” vs “old” way of approaching nuclear disarmament, we can return to the theory, and formulate an expectation on how membership in NWFZs influences state positions. As states within NWFZs are not directly threatened by nuclear weapons but more indirectly through the potential catastrophic humanitarian impact of nuclear use (and often have to cope with the humanitarian impact of nuclear testing), we would expect that their preferences would more strongly lean toward the “new” way of viewing nuclear disarmament. This effect would be stronger among the more institutionalized NWFZs.

Assessing the impact of NWFZs on positions on the TPNW

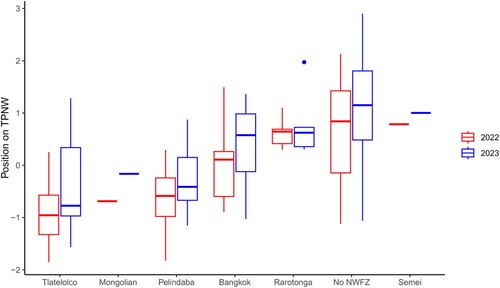

We continue our analysis by looking at the variations among the individual NWFZs, to see if there are differences among them. We first explore these differences through descriptive statistics. shows the distribution of positions grouped by NWFZ and year, summarized in boxplots in ascending order by mean position of each NWFZ.Footnote16

We start with the Latin American countries in the Treaty of Tlatelolco. We observe that they are firmly located on the more “negative” end of the scale, demonstrating clear affiliation with the “new” approach to nuclear disarmament. The fact that the words associated with the Treaty of Tlatelolco are among the most discriminating highlights peculiar regional dynamics. However, between 2022 and 2023, we observe growing heterogeneity between the countries in the region, demonstrated by the increasing standard deviation. Interestingly enough, Brazil and Mexico, two of the most prominent regional actors on nuclear issues which took part in the conference (Argentina, the third relevant one, did not) are further to the right from the regional group, closer to the traditional understanding of nuclear disarmament. This might be linked to the ambition of these countries to fulfil a bridge-building role.

We observe the opposite trend in the Treaty of Pelindaba, which established the NWFZ in Africa. The variation among the members remained largely the same. While the average position among the African countries is slightly more moved toward the “old” understanding, it still demonstrates a higher affinity toward the “new” understanding of nuclear disarmament. Again, the two most prominent members of this group, South Africa and Nigeria, are closer to the “old” understanding of nuclear disarmament when compared to the rest of the group, which again might be linked to their ambition to play a role beyond the region.

The same applies to the Southeast Asian countries in the Treaty of Bangkok. These countries are on average closer to the “old” understanding of nuclear disarmament, and variation among them, measured by standard deviation, slightly decreased between the two meetings. The situation is very similar in the case of the parties to the Treaty of Rarotonga, establishing the South Pacific NWFZ. New Zealand was a clear outlier from the median regional position in 2022, and as highlighted by , especially in 2023.

When it comes to Mongolia and Kazakhstan (as the only representatives of the Mongolian and Central Asian NWFZs), their positions shifted toward the “positive” end in 2022. Mongolia, however, remained in a range which is relatively common for Asian countries, whereas Kazakhstan was closer to Western countries.Footnote17 Obviously, the largest and most diverse group of countries are those outside any NWFZs. This group is very heterogeneous, because it includes countries like Germany and the Netherlands, but also Egypt (which never ratified the Treaty of Pelindaba). It became even more heterogeneous in 2023 when compared to 2022. As already suggested, it is the one group comprising the countries with the most positive values, standing for a more conservative view of disarmament.

We then test the impact of membership in an NWFZ against a series of other factors that are expected to drive the position of states on the TPNW through inferential statistics. To do so, we remove from our data all the non-state actors. We focus only on positions at the 2022 MSP as data about many of our independent variables for the year 2023 are unavailable at the moment of writing. Because of missing data in one or more of our dependent variables, the following states are further removed from the analysis: Cuba, Venezuela, the Holy See, the Comoros, Libya, Laos, Vietnam, Kiribati, Palau, Samoa, Palestineand the Cook Islands.

reports the results of two linear regression models. The dependent variable is the same across Models 1 and 2: state positions on the TPNW across the ideological dimension identified through Wordfish, contrasting a more innovative and humanitarian approach to disarmament and a more conservative and security-focused one, ranging from smaller to larger values. What it changes across the two models is the operationalization of our independent variable: state membership in an NWFZ. In Model 1, we test the difference between all states that are members of an NWFZ and states that are not member of any NWFZ, employing a dichotomous variable. In Model 2, we test instead the difference between being a member of one of the existing NWFZs and not being a member of any NWFZ, using this latter category as a reference in the regression models.

Table 1. Testing the impact of NWFZs against alternative hypotheses.

In both models, we control for the effect of five variables, testing the corresponding number of alternative hypotheses. First, we include in the models the agreement score between the state and the United States, based on all resolution votes at the 77th session of the United Nation General Assembly (UNGA) as measured by Voeten (Citation2020) to assess the effect of diplomatic closeness to the US on the position on the TPNW. The larger the score, the stronger the agreement with the US, ranging from 0 to 1. We hypothesize that the distance from the United States is relevant because much of the pressure exercised by the activists and states alike was targeted toward the allies under the US nuclear umbrella (Maitre, Citation2022; Ritchie & Kmentt, Citation2021). Furthermore, the United States has been at the forefront of opposing the TPNW, often rallying closer allies as well as more distant countries to oppose the treaty. Second, we add a variable measuring the share of military expenditure over GDP, using data from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, to test the effect of militarism. We multiplied the share by 100 to enhance interpretability of the coefficients. We assume that more militaristic states will have a more conservative approach to disarmament and vice versa. Third, we control for the effect of a country’s economic power by including a measure of its GDP, expressed in constant billions of dollars. Because of their status and higher extent of responsibility in the international community, we expect larger and more powerful states to adopt a more cautious stance on the TPNW. Fourth, we added a dichotomous variable distinguishing states that have been engaged in at least one intra-state armed conflict in 2022, as reported by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) Armed Conflict dataset.Footnote18 As noted by Risse (Citation2024), involvement in intra-state conflict negatively affects the cooperation of a state on disarmament. Finally, we control for the regime type, using V-Dem’s electoral democracy index, ranging from 0 to 1. More democratic countries have larger scores in this variable and vice versa.Footnote19

Model 1 suggests that being part of an NWFZ has a significant impact on the positions of states on the TPNW, even controlling for all the just mentioned factors. The negative sign in the coefficient for the dichotomous variable indicates that NWFZ countries tend to lean toward a more humanitarian view of global disarmament. This further corroborates what we found in our earlier descriptive analysis. Model 2 refines this claim, by showing that only membership in certain NWFZs pushes states to have such a position. Tlatelolco and, to a lesser extent, Pelindaba, countries are the only ones that significantly differ from the non-NWFZ countries in that sense.

The existing literature has already emphasized the uniqueness of Latin America for global nuclear disarmament, because the NWFZ has clearly shaped how states there view nuclear disarmament more broadly. This negative effect is stronger compared to other zones. While analyzing the raw values of the scores did not enable us to seize this difference neatly, multivariate regression undoubtedly indicates how Latin American countries stand out. This is also in line with the findings which Latin American diplomats recently wrote about, highlighting the TPNW as another of the contributions of Latin America to global nuclear disarmament (Duarte, Citation2024).

However, we also show that a similar dynamic is at play in Africa. The dynamics and effects of the Treaty of Pelindaba are much less known. One possible explanation for this effect is the strong anti-colonial (and relatedly, anti-apartheid) dynamic which shaped how states view nuclear disarmament in Africa. As many African countries were exploited by colonial powers in the pursuit of nuclear weapons (either through exploitation of raw materials or nuclear testing), this has influenced their self-perception (see also Hecht, Citation2014). Future work should explore the socializing effects of the Pelindaba Treaty in more detail. However, the finding that the two most institutionalized NWFZs have the strongest effect on state positions fits very well with our expectations.

Actually, membership in other NWFZs such as Bangkok, Rarotonga, and Semei seems to foster states toward a more conservative position on the Treaty with respect to states that are not member of any NWFZ. However, it is worth noting that only Semei has a slightly significant impact in this direction. As far as the control variables, we observe no statistically significant effect of closeness to the United States, military expenditure, or involvement in armed conflict. Economic size and level of democracy have a significantly positive effect, but only in Models 1 and 2 respectively: larger and more democratic states seem to have on average a more security-focused approach to the TPNW. In any case, the fact that none of the control variables has a consistently significant impact on our dependent variable further reinforces our finding about the relevance of NWFZs as an explanatory factor for the positions of states on the treaty.

Discussion and conclusion

Existing perspectives on how states view and position themselves vis-à-vis the TPNW lacked the necessary nuance to distinguish between different views of state parties. In this article, we remedy this shortcoming by developing a reliable and valid measure of state positions, and then explaining such positions as being influenced by membership in NWFZs. We arrived at our measure by extracting positions vis-à-vis the TPNW applying Wordfish, an unsupervised scaling method of text, to statements made during the TPNW’s first and second MSP. Our analysis demonstrates that the participants in the TPNW meetings were not a homogeneous mass and that there is substantive variation in how states position themselves toward the treaty.

We also find that participation in NWFZs is an important factor in explaining the position of states toward the treaty, particularly when it comes to Latin America and Africa. These two regions stand out from other NWFZs by having institutionalized zones, which are also tied by strong regional identities. Latin American and African participants leaned toward what we labeled as the “new” way of seeing nuclear disarmament, more focused on humanitarian issues. This leaning is in line with the particular nuclear identity developed in Latin America (Rodriguez & Mendenhall, Citation2022), but finding that it is also present in Africa is novel. Such a link was not obvious in other parts of the world. Although this does not stem directly from our theory, one result which we do find is that membership in other international organizations where nuclear weapons are salient might also influence state preferences. Our findings indicate that membership in NATO might be of similar importance to membership in NWFZs. What makes NATO more salient than, for instance, the NPT, is the increased salience of nuclear weapons for the deterrence posture of the alliance after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the institutionalized focus on nuclear deterrence (with NATO proclaiming itself a “nuclear alliance” in its 2010 Strategic Concept, and maintaining that identity since, see NATO, Citation2010). In doing so, we contribute to the broader literature on socialization in international institutions.

In conclusion, this article makes three contributions. Firstly, it breaks new ground in disarmament text analysis. In particular, we provide an empirical, quantitative assessment of the views of states on the TPNW which is not dependent on in-depth studies of individual countries. As Sagan (Citation2011) argues, in the NPT setting, single-country case studies can be subject to selection bias. Barnum and Lo (Citation2020) reiterate this point in their study of the positions of states toward the NPT. We offer an original application of text-as-data methods to nuclear disarmament, and more broadly, international security. By doing so, this article contributes to a better understanding of the contemporary debates on nuclear disarmament by bringing much-needed nuance to understanding state positions. Rather than portraying debates in stark, black-and-white terms, we argue that more nuance is to be found. Regional considerations, particularly membership in NWFZs, is a very relevant factor shaping how states view nuclear disarmament. Membership in institutionalized NWFZs seems to be particularly relevant in this context. Our findings have important consequences for civil society activists, diplomats, and scholars alike, who often like to portray the debates on nuclear disarmament in somewhat simplistic terms. Of course, the strongest critics of the TPNW did not take part in the MSPs. However, even among the countries that did take part, we find much variation.

Secondly, employing an automated text analysis method, we provide a contribution to the existing scholarship on the TPNW in particular, and nuclear weapons in general. Admittedly, we look only at the positions of states who took part in the meetings, and hence cannot analyze the positions of all countries in the world. Partially because of this limitation, we can also not analyze a larger number of hypotheses. However, our article is to date the largest analysis of state views on the TPNW.

Thirdly, beyond the immediate study of the TPNW, our article also contributes more broadly to scholarship studying the latent distribution of state preferences in international politics (Barnum & Lo, Citation2020; Montal et al., Citation2020). It does so by bringing empirical precision to the measuring of the views of states on the TPNW across a large sample of states—both members and non-members. It is therefore of interest to general international relations scholarship, with particular relevance to the study of international security. Our study shows that states relate to one another in diplomatic, highly institutionalized settings, offers a demonstration of a method to study such relations, and contributes to broader work on international institutions.

Future studies can further the use of quantitative tools to understand the dynamics of the TPNW, or develop rigorous mixed-method designs to study the dynamics of nuclear disarmament. Future work could also more thoroughly engage the study of the socialization dynamics in NWFZs, perhaps studying how they affect state positions on nuclear preferences over a longer period of time. Last but not least, given that the state parties in Vienna decided to develop new structures in support of the TPNW’s mission, future research might find data analytical tools useful for understanding the dynamics within the treaty.

Acknowledgements

We thank CSP’s excellent reviewers and editors, as well as Rebecca Davis Gibbons, Stephen Herzog, and Espen Mathy for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Nick Ritchie traces the idea of banning nuclear weapons on humanitarian grounds to two articles (Mian, Citation2009; Lewis, Citation2009).

2 Smetana and O’Mahoney (Citation2022) cite no fewer than nineteen academic articles published in recent years decrying the collapse of the NPT.

3 Replication files are available upon request from the authors and on https://doi.org/10.25397/eur.26147659.

4 https://tinyurl.com/TPNWdatabase (status as of 26 June 2024).

5 See also the recent article by Stärk and Kühn (Citation2022), linking the TPNW to nuclear justice.

6 While Belcher does not define the term, she uses it to describe ideas which are unconventional and run against the establishment.

7 Rodriguez and Mendenhall (Citation2022) discuss how states maintain different preferences even when they are members of the same NWFZ. We are grateful to R2 for making sure that this difference gets emphasized.

8 For an overview of the methods of Text as Data, see Benoit (Citation2020). For an assessment of the potentialities and challenges of these methods in the study of International Relations, see Vignoli (Citation2023).

9 For a comparison between Wordfish and Wordscores, see Egerod and Klemmensen (Citation2020).

10 We used the R Package Quanteda for performing the pre-processing and the extraction of positions through Wordfish (Benoit et al., Citation2018).

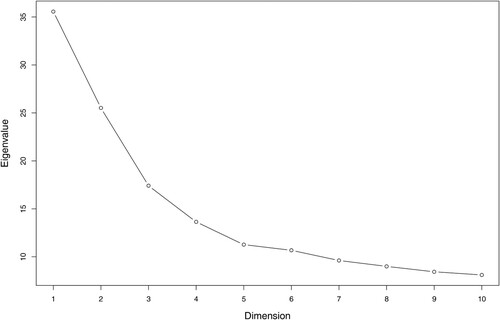

11 We performed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of this matrix to check for its dimensionality. The Scree Plot reported in Figure A1 in the Appendix shows the presence of one dominant dimension in our data, as the extent of variance to explain drastically diminishes moving from one to two dimensions. This provides solid empirical justification for employing a method that locates actors across a single dimension.

12 The only minimal form of input required by Wordfish on the researcher consists in identifying two documents to set the direction of the dimension: i.e., to tell the algorithm what is negative and what is positive. We picked the statements made by the Cook Islands and Germany at the first MSP as parameters for the negative and positive side of the dimension respectively, since we expected them to articulate very different point of views on disarmament. It must be pointed out that this selection serves only to suggest to Wordfish the direction of the dimension but does not determine the final positions. This is demonstrated for instance by the fact that these two statements do not present the two most negative and positive scores respectively. If we inverted the two parameters, we would obtain the same positions just with opposite signs, thereby not generating any bias in our results.

13 The positions for the NGOs Mayors for Peace and ICAN are not reported as these participants cannot be associated with (non) membership in any NWFZ. They both received positive scores: ICAN 0.850 in 2022 and 0.714 in 2023, Mayors for Peace 0.423 in 2022. We conducted a series of robustness checks on these estimates. We re-estimated these positions using different thresholds for removing uncommon words, keeping only those present in at least 20 and 5 percent of the total number of documents instead of 10 percent. In both cases, the resulting estimates strongly and significantly correlate with the ones shown in the article (r = 0.92 and r = 0.94, respectively). Furthermore, we conducted a pooled analysis aggregating speeches from both debates by an actor. Again, the resulting estimates are strongly and significantly correlated with the one shown in (r = 0.9).

14 Confidence intervals are rather wide as a consequence of the limited number of features contained in the matrix. However, differences in the positions of states across the latent dimension are still significant in many cases.

15 To further validate our dimension, we assessed the relationships between the estimates corresponding to statements made during the first MSP and Voeten’s country ideal points on nuclear issues as extracted from votes at the United Nations General Assembly. The correlation is strong and significant (0.72***), despite the limited number of observations (53). The ideal point for the year 2023 (session 78) is not yet available.

16 For the mean and standard deviation of each group see in the Appendix.

17 Unequal distribution of participants to the TPNW MSP among different NWFZs remains a challenge for this study. However, we lacked comparable data for countries that did not decide to join the treaty and/or participate in the meetings. Future research should deal with this issue by updating this study with statements made during future meetings or using a different source of data to estimate state positions on the TPNW.

18 We did not include the number of intra-state armed conflicts as only six states experienced at least one intra-state conflict and Nigeria was the one involved in the largest number of intra-state dyads with three of them. We did not include a corresponding measure of inter-state conflict as none of the states analyzed was involved in an inter-state conflict in 2022.

19 For a full description of the independent and dependent variables included in the models, see in the Appendix.

Reference list

- Acharya, A. (1997). Ideas, identity, and institution-building: From the ‘ASEAN way’ to the ‘Asia-Pacific way'? The Pacific Review, 10(3), 319–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512749708719226

- Acharya, A. (2011, Jun). Asian regional institutions and the possibilities for socializing the behavior of states. Working Papers on Regional Economic Integration 82, Asian Development Bank. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ris/adbrei/0082.html.

- Acharya, A., & Johnston, A. I. (2007). Comparing regional institutions: An introduction. In A. Acharya, & A. I. Johnston (Eds.), Crafting cooperation: Regional international institutions in comparative perspective (pp. 1–31). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491436

- Acheson, R. (2021). Banning the bomb, smashing the patriarchy. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Acheson, R., & Fihn, B. (2013). Preventing collapse: The NPT and a ban on nuclear weapons. Reaching Critical Will. http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/npt-ban.pdf.

- Bandarra, L., & Martuscelli, P. N. (2024). Moving forward to a world free of nuclear weapons (?): How regional issues shape global non-proliferation and disarmament politics. Peace Review, 36(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2347425

- Barnum, M., & Lo, J. (2020). Is the NPT unraveling? Evidence from text analysis of review conference statements. Journal of Peace Research, 57(6), 740–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320960523

- Baron, J., Gibbons, R. D., & Herzog, S. (2020). Japanese public opinion, political persuasion, and the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 3(2), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2020.1834961

- Bearce, D. H., & Bondanella, S. (2007). Intergovernmental organizations, socialization, and member-state interest convergence. International Organization, 61(4), 703–733. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070245

- Belcher, E. (2020). Transforming our nuclear future with ridiculous ideas. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76(6), 325–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1846420

- Benoit, K. (2020). Text as data: An overview. In L. Curini, & R. Franzese (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research methods in political science and international relations (pp. 461–497). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526486387.n29

- Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Bollfrass, A. K., & Herzog, S. (2022). The war in Ukraine and global nuclear order. Survival, 64(4), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2022.2103255

- Bolton, M., & Minor, E. (2016). The discursive turn arrives in turtle bay: The international campaign to abolish nuclear weapons’ operationalization of critical IR theories. Global Policy, 7(3), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12343

- Borrie, J. (2014). Humanitarian reframing of nuclear weapons and the logic of a ban. International Affairs, 90(3), 625–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12130

- Brands, H. (2007). Non-proliferation and the dynamics of the middle cold war: The superpowers, the MLF, and the NPT. Cold War History, 7(3), 389–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682740701474857

- Brixey-Williams, S. (2017). The ban treaty: A big nuclear-weapon-free zone? Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2017/06/the-ban-treaty-a-big-nuclear-weapon-free-zone/.

- Checkel, J. T. (2005). International institutions and socialization in Europe: Introduction and framework. International Organization, 59(4), 801–826. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050289

- Checkel, J. T. (2016). Regional identities and communities. In T. A. Börzel, & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism (pp. 559–578). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199682300.013.25

- Chelotti, N., Dasandi, N., & Jankin Mikhaylov, S. (2022). Do intergovernmental organizations have a socialization effect on member state preferences? Evidence from the UN general debate. International Studies Quarterly, 66(1), sqab069. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab069

- Coe, A. J., & Vaynman, J. (2015). Collusion and the nuclear nonproliferation regime. The Journal of Politics, 77(4), 983–997. https://doi.org/10.1086/682080

- Considine, L. (2019). Contests of legitimacy and value: The treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons and the logic of prohibition. International Affairs, 95(5), 1075–1092. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz103

- Dhanapala, J., & Duarte, S. (2015). Is there a future for the NPT? Arms Control Today, 45(6), 8–10.

- Docherty, B. (2018). A ‘light for all humanity’: The treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons and the progress of humanitarian disarmament. Global Change, Peace & Security, 30(2), 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2018.1472075

- Don't Bank on the Bomb. (2023). Why divest? A focus on governments. https://www.dontbankonthebomb.com/take-action-for-divestment/governments/.

- Doyle, T. (2017). A moral argument for the mass defection of non-nuclear-weapon states from the nuclear nonproliferation treaty regime. Global Governance, 23(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02301002

- Duarte, S. (2024). The contribution of Latin America and the Caribbean to multilateral nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament. Peace Review, 36(2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2331724

- Egel, N., & Obermeier, N. (2022). A friend like me: The effect of international organization membership on state preferences. The Journal of Politics, 85(1), 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1086/722348

- Egel, N., & Ward, S. (2022). Hierarchy, revisionism, and subordinate actors: The TPNW and the subversion of the nuclear order. European Journal of International Relations, 28(4), 751–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661221112611

- Egeland, K. (2019). Arms, influence and the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. Survival, 61(3), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1614786

- Egeland, K. (2021). Nuclear weapons and adversarial politics: Bursting the abolitionist “consensus”. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 4(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2021.1922801

- Egerod, B. C. K., & Klemmensen, R. (2020). Scaling political positions from text: Assumptions, methods and pitfalls. In L. Curini, & R. Franzese (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research methods in political science and international relations (pp. 498–521). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526486387.n30

- Fihn, B. (2017). The logic of banning nuclear weapons. Survival, 59(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2017.1282671

- Fuhrmann, M., & Lupu, Y. (2016). Do arms control treaties work? Assessing the effectiveness of the nuclear nonproliferation treaty. International Studies Quarterly, 60(3), 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw013

- Futter, A., & Samuel, O. (forthcoming). Accommodating nutopia: The nuclear ban treaty and the developmental interests of Global South countries. Review of International Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210523000396

- Gavras, K., Mader, M., & Schoen, H. (2022). Convergence of European security and defense preferences? A quantitative text analysis of strategy papers, 1994–2018. European Union Politics, 23(4), 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165221103026

- Gheciu, A. (2005). Security institutions as agents of socialization? NATO and the ‘New Europe’. International Organization, 59(4), 973–1012. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818305050332

- Gibbons, R. D. (2018). The humanitarian turn in nuclear disarmament and the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. The Nonproliferation Review, 25(1-2), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2018.1486960

- Gibbons, R. D., & Herzog, S. (2022). The first TPNW meeting and the future of the nuclear ban treaty. Arms Control Today, 52(7), 12–17.

- Gibbons, R. D., & Herzog, S. (2023). Nuclear disarmament and Russia’s War on Ukraine: The ascendance and uncertain future of the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. In R. D. Gibbons, S. Herzog, W. Wan, & D. Horschig (Eds.), The altered nuclear order in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war (pp. 1–36). American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

- Goodman, R., & Jinks, D. (2013). Socializing states: Promoting human rights through international law. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199300990.001.0001

- Greenhill, B. (2010). The company you keep: International socialization and the diffusion of human rights norms. International Studies Quarterly, 54(1), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00580.x

- Hassid, N. (2024). The challenges and avenues for banning nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Peace Review, 36(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2328544

- Hecht, G. (2014). Being nuclear: Africans and the global uranium trade. MIT Press.

- Herrera, M. (2024). The European Union and the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons: Let’s agree that we disagree. Peace Review, 36(2), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2328547

- Herzog, S., Baron, J., & Gibbons, R. D. (2021). Antinormative messaging, group cues, and the nuclear ban treaty. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1086/714924

- Hill, C., & Wong, R. (2012). Many actors, one path? The meaning of Europeanization in the context of foreign policy. In R. Wong, & C. Hill (Eds.), National and European foreign policy: Towards Europeanization (pp. 210–231). Routledge.

- Horovitz, L. (2015). Beyond pessimism: Why the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons will not collapse. Journal of Strategic Studies, 38(1-2), 126–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2014.917971

- Ikenberry, G. J., & Kupchan, C. A. (1990). Socialization and hegemonic power. International Organization, 44(3), 283–315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830003530X

- Johnston, A. I. (2001). Treating international institutions as social environments. International Studies Quarterly, 45(4), 487–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00212

- Johnston, A. I. (2003). Socialization in international institutions. In G. J. Ikenberry, & M. Mastanduno (Eds.), International relations theory and the Asia-Pacific (pp. 107–152). Columbia University Press.

- Kacowicz, A. M. (1998). Zones of peace in the Third World: South America and West Africa in comparative perspective. State University of New York Press. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.36-5948

- Kassenova, T. (2022). Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan gave up the bomb. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503629936

- Kmentt, A. (2021). The treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons: How it was achieved and why it matters. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003080879

- Knopf, J. W. (2022). Not by NPT alone: The future of the global nuclear order. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(1), 186–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2021.1983243

- Kwong, J. (2022). How disagreements over Russia’s nuclear threats could derail the NPT Review Conference. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2022/07/how-disagreements-over-russias-nuclear-threats-could-derail-the-npt-review-conference/#post-heading.

- Lacovsky, E. (2021). Nuclear weapons free zones: A comparative perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003119661

- Laver, M., Benoit, K., & Garry, J. (2003). Extracting policy positions from political texts using words as data. American Political Science Review, 97(2), 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000698

- Lewis, P. M. (2009). A new approach to nuclear disarmament: Learning from International Humanitarian Law Success (ICNND Paper No. 13). International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament.

- Maitre, E. (2022). Implementing prohibition: An overview of the meeting of states parties to the TPNW and possible ways forward. Recherches & Documents n°08/2022 https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/recherches-et-.

- Mathy, E. (2023). Why do states commit to the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons? The Nonproliferation Review, 29(1-3), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2023.2175994

- Meier, O., & Vieluf, M. (2021). From division to constructive engagement: Europe and the TPNW. Arms Control Today, 51(10), 6.

- Mian, Z. (2009). Beyond the security debate: The moral and legal dimensions of abolition. In G. Perkovich, & J. M. Acton (Eds.), Abolishing nuclear weapons: A debate (pp. 295–305). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Mir, M. A., & Nazir, T. (2024). South Asian perspectives on the nuclear weapons ban: Challenges and prospects for disarmament. Peace Review, 36(2), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2328541

- Montal, F., Potz-Nielsen, C., & Sumner, J. L. (2020). What states want: Estimating ideal points from international investment treaty content. Journal of Peace Research, 57(6), 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320959130

- Mpofu-Walsh, S. (2020). Obedient rebellion: Nuclear-weapon-free zones and global nuclear order, 1967–2017 [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. Oxford University.

- Mpofu-Walsh, S. (2022). Obedient rebellion: Conceiving the African nuclear weapon-free zone. International Affairs, 98(1), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab208

- Müller, H., & Wunderlich, C. (2020). Nuclear disarmament without the nuclear-weapon states: The nuclear weapon ban treaty. Daedalus, 149(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01796

- NATO. (2010). Active engagement, modern defence. NATO 2010 Strategic Concept. https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_publications/20120214_strategic-concept-2010-eng.pdf.

- Norwegian People's Aid. (2024). Nuclear weapons ban monitor. https://banmonitor.org/.

- Nuclear Threat Initiative. (2023a). Pelindaba treaty. https://www.nti.org/education-center/treaties-and-regimes/african-nuclear-weapon-free-zone-anwfz-treaty-pelindaba-treaty/.

- Nuclear Threat Initiative. (2023b). Bangkok treaty. https://www.nti.org/education-center/treaties-and-regimes/southeast-asian-nuclear-weapon-free-zone-seanwfz-treaty-bangkok-treaty/.

- Nzo, A. (1995). The statement by the foreign minister of the Republic of South Africa, Mr Alfred Nzo. The 1995 review and extension conference of the parties to the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. Department of International Relations and Cooperation Archives (Pretoria).

- Onderco, M. (2017). Why nuclear weapon ban treaty is unlikely to fulfil its promise. Global Affairs, 3(4-5), 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2017.1409082

- Onderco, M. (2020). Nuclear ban treaty: Sand or grease for the NPT? In T. Sauer, J. Kustermans, & B. Segaert (Eds.), Non-nuclear peace: The ban treaty and beyond (pp. 131–148). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26688-2_7

- Onderco, M. (2021). Networked nonproliferation: Making the NPT permanent. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.11126/stanford/9781503628922.001.0001

- Onderco, M., & Farrés Jiménez, A. (2021). A comparison of national reviews of the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. EUNPDC Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Papers No.76. https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/eunpdc_no_76.pdf.

- Onderco, M., Smetana, M., van der Meer, S., & Etienne, T. W. (2021). When do the Dutch want to join the nuclear ban treaty? Findings of a public opinion survey in the Netherlands. The Nonproliferation Review, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2021.1978156

- Pilat, J. F. (2020). A World Without the NPT Redux. UNIDIR.

- Popp, R. (2017). The long road to the NPT: From superpower collusion to global compromise. In R. Popp, L. Horovitz, & A. Wenger (Eds.), Negotiating the nuclear non-proliferation treaty: Origins of the nuclear order (pp. 9–36). Routledge.

- Potter, W. C. (2017). Disarmament diplomacy and the nuclear ban treaty. Survival, 59(4), 75–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2017.1349786

- Pretorius, J., & Sauer, T. (2021). Ditch the NPT. Survival, 63(4), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1956197

- Reaching Critical Will. (2023). Nuclear ban daily, Vol. 4, No. 2 (28 November 2023). Civil society perspectives on the Second Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons 27 November–1 December 2023. https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/nuclear-weapon-ban/2msp/reports/nbd4.2.pdf.

- Risse, T. (2024). External threats and state support for arms control. Journal of Peace Research, 61(2), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433221123359

- Ritchie, N. (2014). Waiting for Kant: Devaluing and delegitimizing nuclear weapons. International Affairs, 90(3), 601–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12129

- Ritchie, N. (2019). A hegemonic nuclear order: Understanding the Ban Treaty and the power politics of nuclear weapons. Contemporary Security Policy, 40(4), 409–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1571852

- Ritchie, N., & Egeland, K. (2018). The diplomacy of resistance: Power, hegemony and nuclear disarmament. Global Change, Peace & Security, 30(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2018.1467393

- Ritchie, N., & Kmentt, A. (2021). Universalising the TPNW: Challenges and opportunities. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 4(1), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2021.1935673

- Rodriguez, J. L., & Mendenhall, E. (2022). Nuclear weapon-free zones and the issue of maritime transit in Latin America. International Affairs, 98(3), 819–836. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiac055

- Rublee, M. R., & Wunderlich, C. (2022). The vitality of the NPT after 50. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2022.2037969

- Ruzicka, J. (2019). The next great hope: The humanitarian approach to nuclear weapons. Journal of International Political Theory, 15(3), 386–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755088218785922

- Sagan, S. D. (2011). The causes of nuclear weapons proliferation. Annual Review of Political Science, 14(1), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052209-131042

- Sarmiento, P., & Jegho, L. (2023). ASEAN stepping up push for treaty on nuclear weapon-free zone. China Daily Hong Kong. https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/327613.

- Sauer, T. (2024). The impact of the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons: The crucial role of the European NATO allies. Peace Review, 36(2), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2337881

- Slapin, J. B., & Proksch, S.-O. (2008). A scaling model for estimating time-series party positions from texts. American Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 705–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00338.x

- Smetana, M., & O'Mahoney, J. (2022). NPT as an antifragile system: How contestation improves the nonproliferation regime. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(1), 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2021.1978761

- South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty. (1985). https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/South-Pacific-Nuclear-Zone-Treaty-Raratonga-Treaty-1.pdf.

- Stärk, F., & Kühn, U. (2022). Nuclear injustice: How Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows the staggering human cost of deterrence. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2022/10/nuclear-injustice-how-russias-invasion-of-ukraine-shows-the-staggering-human-cost-of-deterrence/.

- Stefanović, A, Šulejić, Kostić. (2024). Southeast European Countries and a Nuclear Weapons Ban. Peace Review, 36(2), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2024.2340093

- Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. (2018). Report of the Working Group to analyse the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/eda/en/documents/aussenpolitik/sicherheitspolitik/2018-bericht-arbeitsgruppe-uno-TPNW_en.pdf.

- UK Government. (2018). P5 Joint statement on the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/p5-joint-statement-on-the-treaty-on-the-non-proliferation-of-nuclear-weapons.

- United Nations. (2017). Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. United Nations Treaty Series vol. 3379. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/2017/07/20170707%2003-42%20PM/Ch_XXVI_9.pdf.

- Vignoli, V. (2023). Text as data. In P. A. Mello, & F. Ostermann (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of foreign policy methods (pp. 536–550). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003139850-40

- Vilmer, J.-B. J. (2022). The forever-emerging norm of banning nuclear weapons. Journal of Strategic Studies, 45(3), 478–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1770732

- Voeten, E. (2020). United-nations-general-assembly-votes-and-ideal-points. GitHub. https://github.com/evoeten/United-Nations-General-Assembly-Votes-and-Ideal-Points/blob/master/Output/IdealpointestimatesNuclear_Apr2020.csv.

- Von Stein, J. (2005). Do treaties constrain or screen? Selection bias and treaty compliance. American Political Science Review, 99(4), 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051919

- Williams, H. (2018). A nuclear babel: Narratives around the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. The Nonproliferation Review, 25(1-2), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2018.1477453