ABSTRACT

What do we actually know about how replicas of historical objects and monuments ‘work’ in heritage contexts, in particular their authenticity, cultural significance and intangible qualities? In this article we examine this question drawing on ethnographic research surrounding the 1970 concrete replica of the eighth-century St John’s Cross on Iona, Scotland. Challenging traditional precepts that seek authenticity in qualities intrinsic to original historic objects, we show how replicas can acquire authenticity and ‘pastness’, linked to materiality, craft practices, creativity, and place. We argue that their authenticity is founded on the networks of relationships between people, places and things that they come to embody, as well as their dynamic material qualities. The cultural biographies of replicas, and the ‘felt relationships’ associated with them, play a key role in the generation and negotiation of authenticity, while at the same time informing the authenticity and value of their historic counterparts through the ‘composite biographies’ produced. As things in their own right, replicas can ‘work’ for us if we let them, particularly if clues are available about their makers’ passion, creativity and craft.

“heaven in ordinarie” […] It’s a base material, it’s a beautiful object. On one level it’s a replica, and on another level it’s totally the real deal. On one level it speaks less powerfully because it’s not the original stone, hand carved with medieval tools, but on another level, it’s an expression of another kind of workmanship, and of a transmutation of that eternal truth, from the ninth century through to the twentieth century (Gertrude, a recent Iona resident)

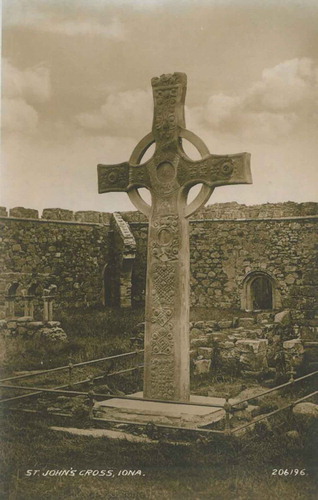

The subject of Gertrude’s ruminations is a full-scale 1970 concrete replica of the St John’s Cross, located at the renowned Iona Abbey, first established by St Columba in the mid-sixth century. The replica has an intricate set of relationships with a wider assemblage of historic carved stone crosses and their many and varied scale replicas, ranging from superbly crafted antique and contemporary jewellery, to mass-produced items, such as fridge magnets. These in turn are disparately related to the reconstructed Abbey and the traditions of ‘workmanship’ associated with the dispersed Christian ecumenical Iona Community established by George MacLeod in 1938, but rooted in the Church of Scotland. Gertrude’s musings take in the breadth of these associations, bringing together questions of materiality, beauty, craft, temporality and truthfulness. Above all, she is grappling with the complexity, subtlety and elusiveness of authenticity – all prompted by a concrete replica.

This article focuses on our ethnographic research surrounding the St John’s Cross replica and its wider material and social relationships. Our aim is to examine how replicas of historical objects and monuments ‘work’ in heritage contexts, and in particular how they inform the experience of authenticity. Within modernist discourses, authenticity has been firmly associated with original historic objects, and these discourses continue to hold sway in many heritage and museum contexts. As a consequence, replicas have a chequered history (Foster and Curtis Citation2016; Lending Citation2017), regarded as unruly or ‘wild’ objects, potentially subverting or threatening the authenticity of originals (Stockhammer and Forberg Citation2017, 12). Even where their value is recognised, replicas are deemed to lack the ‘history of felt relationships’ of originals (Lowenthal Citation1985, 295).

We contest these long-standing precepts and show that historic replicas can be actively involved in the production and negotiation of authenticity. Like original historic objects, their authenticity is in part founded on the networks of relationships that they come to embody – relations with people, objects and, importantly, places (Jones Citation2010, 189–90; Citation2016). Another significant component is the way they ‘connect’ through affect, producing a ‘touching’ encounter where the senses and emotions respond in some positive, but ineffable way (what Jeffrey Citation2015, 147 refers to as the ‘thrill of proximity’). Contra Holtorf (Citation2013), we also show that, even in the case of replicas, authenticity is not merely a social construct, but simultaneously draws on the material qualities of the thing itself (Jones Citation2010, 183; Graves-Brown Citation2013, 222). At the same time, the importance of what Holtorf (Citation2013) calls ‘pastness’ is clearly evident in terms of people’s emotive responses, along with what we have coined ‘anti-pastness’. Finally, the cultural biographies of replicas, and the ‘felt relationships’ associated with them, play a key role in the generation of authenticity, while simultaneously informing the authenticity and value of their historic counterparts through the ‘composite biographies’ produced (Foster Citation2018; Foster, Blackwell, and Goldberg Citation2014; Foster and Curtis Citation2016). In this regard, our research provides categorical support for emerging arguments about the importance of production, creativity and craft in generating authenticity at key moments in the story of a replica, whether it be physical or digital (Cameron Citation2007, 55, 60, 67; Jeffrey Citation2015; Jones et al. Citation2017; Latour and Lowe Citation2011).

As acknowledged above, some of these arguments have been made before in various guises, by us and other authors. However, there is a dearth of substantive, empirical research focusing on how replicas inform the experience of authenticity in heritage contexts. This in-depth qualitative study centred on a particular historic replica provides substantive empirical support for the arguments outlined above. During June and July 2017 we undertook focused, short-term ethnography (Low Citation2002; Taplin, Scheld, and Low Citation2002; Knoblauch Citation2005), consisting of qualitative, semi-structured interviews (59 in total) and participant observation. Longer recorded interviews (more than 48 hours in total) were designed to situate people’s experience of the replica within the context of their experience of the island, the Abbey, and the other crosses on Iona. Our sample included a cross-section of local residents, heritage professionals, staff and residents of the Iona Community (IC), longer-term visitors to the island, and individuals who had been involved in the production of the replica. Shorter interviews were also conducted with tourists on fleeting day visits, which were recorded through detailed field notes.

Throughout, we also used participant observation to examine how people engaged with the replica, its fragmented historic counterpart and other crosses on the island. We stayed with various residents engaged in the island’s tourist industry during our fieldwork and participated in short religious pilgrimages organised by the IC, as well as secular tours led by Historic Environment Scotland (HES) staff. Drawing on the ACCORD project methodology (Jones et al. Citation2017, 6–7), we also held a small digital modelling workshop focused on the replica, which provided an ‘intense route to knowing’ (Pink and Morgan Citation2013, 351). In February 2018 we extended elements of this approach to a workshop with the Iona Primary School to gain insights into the children’s perceptions of the replica and other crosses (GSoASimVis Citation[2017] 2018). We interviewed teachers before and after, observed the children in class, and made observations from their artwork.

In what follows, we discuss the results of our fieldwork, which provide a rich and nuanced picture of people’s responses to the St John’s Cross (hereafter SJC) replica, and how its authenticity or otherwise is produced and negotiated through a complex web of relations, qualities and associations. The research challenges many of the prevailing assumptions about how historic replicas work and in the conclusion we make a case for a radical transformation in how we theorise them. We also highlight a few of the practical inferences, but leave a more detailed discussion of the implications for heritage management, interpretation and display to another article (Foster and Jones Citationin press). Likewise, a more in-depth temporal perspective on the SJC replica will be provided in a monograph exploring its complex, composite biography (Foster Citationforthcoming). Here, we begin by introducing the SJC replica and its wider historic and ethnographic contexts. We then focus on four main themes: the social and material networks in which it is embedded; place and displacement; materiality and ‘pastness’; and finally craft, creativity and biography. Throughout, we refer to recent research and current debates surrounding authenticity and the use of replicas in heritage contexts. We use pseudonyms to refer to ethnographic participants and interviewees.

Background: Iona, the St John’s Cross, and its replica

Iona bears a ‘burden of history and legend, of beliefs and expectation’ that belies its size (MacArthur Citation2007b, 199). The small island with its population of c.130 is a short ferry crossing away from the western tip of Mull, its mountainous neighbour in Scotland’s Inner Hebridean archipelago (). It requires an effort to get there, but every year domestic and foreign visitors swell its numbers by a thousand times as many. It has been internationally renowned since at least the mid-sixth century, when St Columba, the best known of the early saints to introduce Christianity to Scotland, established his monastic base there in AD 563. By the time of Columba’s biographer Adomnán, writing in the late seventh century, there was a large and wealthy monastery on Iona and its powerful abbot was the head of a monastic confederacy spanning Ireland and northern Britain. In around 1200 the Lords of the Isles established a Benedictine Abbey within the vallum of the monastery. This, the island’s Nunnery and associated chapels fell into ruins after the Reformation of 1560.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Iona, and key features mentioned in text. Graphic Christina Unwin.

The island’s ruins and its extraordinary assemblage of historic carved stones, combined with the nearby lure of Staffa’s Fingal’s Cave, have attracted travellers, antiquarians and scholars for centuries (Foster Citation2017). Insights into how today’s visitors find the island special can be found in a recent independent ethnographic study (Bhattacharjee Citation2018). For the purposes of this study, Iona Abbey offers several eighth-century and later high crosses in diverse contexts. The complete, in-situ St Martin’s Cross, in-situ SJC replica and in-situ base of St Matthew’s Cross () are situated outside, while the original SJC, St Oran’s and St Matthew’s Crosses have been relocated for conservation purposes in the Abbey Museum ().

Figure 2. Crosses from left to right, St John’s (replica in original base), St Matthew’s (empty base in front of group of visitors) and St Martin’s, in front of Iona Abbey. Photographer Sally Foster.

Figure 3. St Oran’s, St John’s and St Matthew’s Crosses relocated for conservation purposes in the Iona Abbey Museum, upgraded in 2013. Photographer Sally Foster.

Carved stones readily lend themselves to studies of value and authenticity because they can become portable and their resulting schizophrenic identity as monuments/artefacts has attendant heritage implications (Foster Citation2001, Citation2010; Jones Citation2004; Foster and Jones Citation2008; Macdonald Citation2013, 131). The SJC replica falls towards the end of a long trajectory of replication of early medieval carved stone monuments in Scotland (Foster Citation2018). Neither the original SJC fragments, nor the full-scale replica, are currently bound up in any contemporary controversies surrounding carved stones that might influence the ways in which authenticity is being experienced and exaggerated, e.g. by forms of dislocation and displacement, or inclusion and exclusion (Foster and Jones Citation2008; Jones Citation2016, 138; Jones et al. Citation2017, 17). Inevitably, our own research will in part inform the way it subsequently gains authenticity (Handler Citation2001, 963).

Some further historical context is necessary. The SJC is one of four monumental high crosses that began life as part of a landscape that directed pilgrims to the Shrine, which was the initial burial place of St Columba. The island once had many crosses. Today, the other survivors out in the open are MacLean’s Cross, erected by a secular patron in the fifteenth century alongside the medieval ‘Street of the Dead’ (the pilgrimage route to the Shrine), and a number of early and later medieval cross bases. Two modern memorials mimic the high-cross form: the Duchess Cross, erected in 1879 by the 8th Duke of Argyll to his first wife, and the 1921 War Memorial.

The original SJC, a composite monument thought to be the progenitor of the ringed, so-called Celtic cross, was already fragmented by the seventeenth century. The dispersed surviving elements were reunited with the in-situ shaft in 1927. In situ in this instance means standing sentinel at the entrance of St Columba's Shrine, which is widely thought to be his burial place. Much of this eighth-century free-standing building has been reconstructed and it is now tucked into the western front of Iona Abbey. The reconstructed SJC fell in 1951 and 1957, and was taken off Iona for technical conservation leading to some local disquiet over its removal. In its absence, David F. O. Russell, a wealthy business man with Iona connections, and the Iona Cathedral Trust (ICT), which had acquired the Abbey in 1899, initiated the production of the full-scale concrete replica. The replica was cast and erected in pre-stressed concrete; a mould had been taken from a plaster model created by casting from the surviving original. The gaps were filled by a combination of duplicating these casts and informed speculation about the abstract designs (Robertson Citation1975). The resulting replica was erected in the original SJC composite box-base in 1970. In a further twist to the tale, the original SJC was returned to the island in 1990, whereupon it found a home in a building converted to a museum by the IC. To add to the complexity of the heritage context, the national heritage body, Historic Scotland (now HES), assumed guardianship of the Abbey and Nunnery in 1999. In 2013, HES opened a new state-of-the-art Abbey Museum, its tour de force the upright, girded original fragments of the SJC flanked by St Matthew’s and St Oran’s Crosses ().

The full-scale concrete SJC replica therefore stands in a tangled set of material relationships, not only with original reconstructed fragments, but also with the historic landscape and the rebuilt Abbey. It is also central to a rich symbolic repertoire of religious and tourist iconography, and a tradition of smaller-scale replication dating back to at least 1899 with the Iona Celtic Art of Alexander and Euphemia Ritchie (MacArthur Citation2003). This in turn can only be understood with reference to the complexity of the island’s multiple communities, the nature of theirs and others’ gazes, and how this relates to different places on the island (). An important distinction needs to be made between the community of Iona, who often refer to themselves as ‘islanders’, and the Iona Community, both of which have been mentioned above. Founded in Glasgow by George MacLeod, between 1938 and 1965 the IC rebuilt and moved into the Abbey’s ruined later medieval monastic buildings. The Abbey Church itself had been restored, and brought back into use, between 1903 and 1910 under the aegis of the ICT. Including representatives from the Catholic and Episcopal churches as well as the Church of Scotland, they were set up to receive and manage the Abbey when the 8th Duke of Argyll decided to relinquish his family’s ownership (MacArthur Citation2007b, 83–4). Recent religious history on Iona is complex, what with the involvement of so many church organisations, as well as spiritual organisations such as the Findhorn Foundation. The other major institution involved is the (secular) National Trust for Scotland, a member-based conservation charity focusing on both natural and cultural heritage, which was gifted the island less its Abbey in 1979.

The islanders and people working there recognise the inevitable fragility of being part of a small island community, but at the same time express a palpable pride that it is also resilient, vibrant and growing. Despite some historic tensions surrounding the establishment of the IC it is seen as an important component in the island’s thriving economy and social life. It contributes to its particularly rich international networks, which challenge notions of ‘remoteness’ and echo the widespread significance of the island in the early medieval period. Nevertheless, the ‘islanders’ (non-IC residents) actively distinguish themselves from the IC: they work to be good neighbours, but there are fences. These fences reflect the specific agenda and focus of the IC: as Mary an islander noted, ‘there’s not a lot of integration goes on […] because they’re so darned busy doing what they’re doing up the road’. MacLeod’s legacy also lives on. Autocratic, patrician, charismatic and quick-witted, his was a passionate mission for a socially relevant church, but his personality and radical agenda created divisions as he sought to create a formal religious community, which incorporated the island’s name (Ferguson Citation2001; Muir Citation2011, 91–123). While initial tensions with the literally put-upon islanders had started to ease by the mid-1950s (Muir Citation2011, 99), challenges remain. As islander Donald noted, reflecting a widely held sentiment: ‘there’s really two communities in a way, although they’re much more one community now than they were’ (see MacArthur Citation2007b, 148–62, 195–6).

This background is relevant to how contemporary social relations intersect with the replica that is the ultimate focus of this study. Describing the older ‘islanders’, fellow islander Margaret reflected on how ‘some of them were so against the Iona Community that they almost seem to absolve themselves from the Abbey’. Accordingly, islanders also emphasise that there is more to Iona than the Abbey and Columba, both before and afterwards. The excellent interpretation at the community’s Heritage Centre reflects the historical research of MacArthur (Citation2007a), descendent of an Iona family, and focuses resolutely on the island community with little mention of the Abbey or the IC. As Mary, a Trustee of the Centre says, ‘the whole aim of the Heritage Centre has always been, to tell the story of the ordinary folk of Iona who get overshadowed by the Iona Community with capital letters, and St Columba really’. Columba and the Abbey, but studiously not the IC, is meantime the interpretative preserve of HES, while in the shared Abbey space the IC tells its own story. Correspondingly, certain places are identified as ‘belonging’ to different communities. The island is served by a single main road, and historic places on or beside the road are more ‘of’ the island community: the Parish Church, Nunnery (in HES care), Reilig Odhráin (burial place: St Oran’s Chapel within it in HES care), MacLean’s Cross (ditto) and the War Memorial. In contrast the reconstructed Abbey, along with its associated residential buildings, and its nearby ‘Welcome Centre and Shop’, are decisively linked to the Iona Community. All these communities come together and overlap in their use of the Abbey Church. Here different identities are defined, albeit with a knowing deftness, for these communities must live alongside each other.

Aside from its more-or-less residential population, Iona is a place of visitation and connection. Many tourists visit for the day or even a few hours, often exclusively committed to a visit to the Abbey. Cruise ships arrive and large groups of passengers descend with commercial guides, while other organised tour groups undertake more leisurely and specialised visits. There is also a veritable tradition of long-stay, repeat and transgenerational visitors on Iona, who are recognised by ‘islanders’ as being in some senses part of the place (MacArthur Citation2007b, 122–4). As Margaret explained, one outcome is that ‘Iona remains a constant from birth until death for many people; it’s a most unusual place’. For visitors, the island’s authenticity is often bound up in the networks of relations they have developed with its place(s), people (including other regular visitors) and its very fabric. A place of meeting and of greeting, it is lovingly regarded as safe, peaceful, beautiful and welcoming, often holding special personal associations. The shared conspiracy and effort of getting there is a part of the magic. Gordon, IC member and former resident summed it up with ‘no-one gets to Iona by accident’, while for Ruben, a heritage professional and regular visitor, ‘it always feels like a pilgrimage going to Iona – the infectious excitement of people waiting for the ferry’. These qualities complement its attraction as a spiritual destination, described by Gertrude as ‘God’s great Cathedral outdoors’, a place of retreat for numerous religious communities. Molly working for the IC sees it as ‘a place of empowering, equipping and sending’. Religious and other visitors allude to what can be characterised as the liminal qualities of the landscape that they experience (), which is leavened for some by its associations as the home of Celtic Christianity, however that is to be interpreted.

For a tiny island, Iona is thus a particularly complex place, in both material and social terms. Famously described as ‘A thin place where only tissue paper separates the material from the spiritual’ by George MacLeod (Ferguson Citation2001, 156), it is patently a ‘thick’ place ethnographically (and historically, Foster Citationforthcoming). In the following section we explore these complex social and material relationships in more depth with specific attention to how they intersect with the SJC and its concrete replica.

‘Loaded objects’: meanings and relationships

According to Isla, one of the Iona’s residents, visitors leave the Aosdàna jewellery shop with their modern replicas of Iona Celtic Art

feeling they’ve purchased part of the cultural heritage of Iona … the objects acquire a significance that is related to their cultural provenance, but also to the personal experience that the customer had when they were on Iona. So they’re loaded objects.

As we will see, the ways in which these objects become embedded in meanings and relationships, relating to experience and place, can also be said to apply to the many and varied crosses on the island, including the SJC replica. This is not immediately evident in conversation with the islanders themselves, many of whom adopt a studied indifference towards the crosses, in part by association with the Abbey and its tenants (see above). Yet, this belies more subtle meanings and relationships. Former resident and frequent visitor, Doris, points out that there is something about how receptive you are to looking, which affects the visibility of the crosses and this depends on your circumstances. It was only after 20 years of visiting, she reflected, that she actually looked at the crosses and noticed them. Similarly, Isla, one of the island’s year-round residents, observes that ‘they’re wallpaper, in terms of your day-to-day life. You just, well you’re walking past them’. Yet this is not a consequence of disinterest. Indeed there are strong undercurrents of association and attachment to both the Abbey and the crosses among the islanders. Margaret explains that: ‘People you would think never went near the Abbey are actually obviously quite involved with it and there is this feeling that it’s our Abbey, which you don’t always feel when talking to people’. For a number of islanders the crosses, including the replica, are also charged with meaning and agency: Molly spoke about how ‘they stood the test of time and they’ve witnessed so much’, while they offer Margaret a ‘comforting permanence’. Moreover, Peter is adamant that it ‘would cause absolute civil war, if the crosses […] were going to be taken off the island’.

Not surprisingly, spiritual meanings and relationships also loom large in respect to the crosses, particularly for the IC community and its guests, although by no means exclusively. For Gertrude, a practising Christian who recently moved to Iona, both the SJC replica and St Martin’s Cross are ‘brought alive by […] pilgrim/community experience’, when used as props in active religious observance, such as the annual Stations of the Cross procession. Since MacLeod’s day, St Martin’s has been the starting point of the IC weekly pilgrimage. Inhabited with fantastic biblical vignettes and other designs, stories with a contemporary resonance are spun around it. Its very name prompts talk of the eponymous saint’s pacifism, an important symbolic element for the IC and its objectives. The role of the crosses as mediums for telling religious stories in the past is lauded by IC members, reworked for contemporary messages about the syncretism of pagan and Christian beliefs and popular notions of Celtic Christianity. These stories have become the signature of the monuments for many associated with the IC, to which can be added SJC’s role as the progenitor of Celtic ringed crosses. The crosses are also described as an aid to meditation and contemplation, sources of energy, the subject of veneration, reminders of faith, and markers of holy ground. Moreover, the replica is no less significant than the original in this regard. ‘Every cross is a replica, isn’t it?’ said Dora, an American IC visitor, while a quick-witted Dutch passerby, on hearing about the 3D digital model of the SJC replica we were creating, wryly observed, ‘so it’s a copy of a copy of a copy’.

Consciously or otherwise, all the crosses, including the replica, therefore have a spiritual agency, and, as Gordon noted, this is inextricably linked to their roots within the landscape (see below):

You’re moving through a landscape, both historical and spiritual, you know. And one of the prayers of the Iona Community was that, you know if Christ’s disciples keep silent, these stones would shout aloud. And they do.

Demonstrative expressions of belief in front of the crosses are almost non-existent. While this is not surprising for the Iona Community, which although ecumenical is a Protestant organisation founded in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, or indeed other Protestant denominations, there are Catholic visitors and many international visitors, some of whom will be of Catholic faith/background. Yet, Marthinus, an Afrikaans member of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and his companions, were the only people we observed genuflecting and making the sign of the cross in front of any of the monuments. Furthermore, excepting St Martin’s, the crosses are rarely the focus of active worship, pilgrimage or other IC activities. Being a Christian cross, replica or not, can also constrain some people’s willingness to engage in the first place, including non-believers, Protestants for whom the cross is associated with Catholicism, and those for whom the cross simply represents suffering.

Beyond the spiritual, what possibilities are there for people to connect with the biography of the replica? We quickly realised that apart from the interviewees involved in its creation nearly 50 years ago, no-one, including any of the heritage professionals, really knew anything about the replica’s creation and subsequent history. When they thought they did, they were often confusing its life story with return of the original SJC to Iona in 1990. Part of the same ‘composite biography’, the lives and fortunes of the original and the replica are inextricably entwined, grounded in the meaningful return of something ‘lost’ to the island. Some people vaguely remembered that the replica had won a concrete award, but only the son of one of the engineers involved in its creation knew the full details, carefully curated in a family archive dedicated to the replica. None of the on-site interpretation reveals any aspect of the replica’s story: it is a proxy for the brilliant, cutting-edge original, ‘now go see the original in the museum’, the display plaque suggests.

The replica is therefore one of an assemblage of crosses, that inhabit an island landscape imbued with both spiritual meanings and more secular forms of attachment and belonging. The crosses have an agency, and become especially meaningful to people when activated by use, not least in storytelling. The replica has no less significance than the original, but ways of engaging and connecting with its biography (and developing a relationship) are effectively shut down by lack of information and the way it is treated as a proxy for the original in terms of heritage management and interpretation. Our research shows that the replica might be said to have its own life, albeit constrained and to some extent dependent on the original. Yet the original was moved into the Abbey Museum, a radically different space in which to experience it. So, what part do place and space play in generating the aura of an in-situ replica?

Place and space

It is widely held that aura diminishes if something is ‘dislocated’ from the systems that give it meaning (Cameron Citation2007, 57; cf. Lowenthal Citation1985, 287), and that includes place and space (although see Lending Citation2017, 70–105). At the same time, Latour and Lowe (Citation2011, 282) assert that there is ‘a sort of stubborn persistence’ that makes it impossible to separate the association of a place, with an original and its aura. Accordingly, they suggest, aura can migrate to (high quality) replicas located in original historic contexts. What does this mean in practice and how might our qualitative research shed light on these processes?

There is wide acceptance that the original SJC needs to be displayed in the Abbey museum because it is too fragile to be conserved outside. The outcome though is a form of dislocation, evident in the commonly held perception that the monumental crosses sheltering in the museum have become art. The idea that they are ‘fragile’ is reinforced and their functions change; they become about ‘formation and edification’ rather than ‘worship and faith, and religion and spirituality’ noted Molly. Outside, in contrast, the crosses are seen by many as integral to the island’s fabric and, in the words of frequent visitor Dorothy, examples of where ‘the spiritual erupts from the earth’. The monumental replica takes on some of these qualities by virtue of the way in which it stands for the original, indeed in some senses is the SJC. As Stella, a heritage professional points out, ‘if you said to the Monument Manager, I’ll meet you at St John’s in ten minutes, you wouldn’t find her in the museum, you’d find her outside the Shrine’. Moreover, the place and space that the replica is located in expand the nature of, and opportunities for, social relations. Where experiences are embodied, stories can be elaborated and become embedded. This most obviously relates to the interlinked ways in which aura and emotion are generated, because the replica stands where people intended the original to be. On tours visitors are told that St Martin’s is ‘the oldest cross still in situ ’ (our emphasis) and reminded of its constant presence, whereas the SJC replica is often ignored in these narratives. Nonetheless, our interviewees attached a lot of significance to both St Martin’s and SJC replica being in situ, and effectively functioning as a team. Intrinsically, the location matters and a primacy is afforded to that original (i.e. first) location. It ‘returns’ something lost and retains a sense of the intended place.

The ability to relate to what people did in the past is also seen as important. Being outside, the replica evokes the tradition of outdoors worship. It also contributes to an ability to reimagine the topography of the Columban monastery, and its symbolism, through the location of its crosses, Shrine, vallum and the rocky prominence of Tòrr an Aba, where St Columba had his writing cell. Although largely unrealised for most people we interviewed, this is a prominent aspect of the HES audio-tour. Another related dimension is the replica’s contribution to an embodied experience of religious or secular pilgrimage along a well-trodden evocative path ending at St Columba’s Shrine.

Outside there is also a palpable pleasure that comes from what feels like an individual experience, the special privilege of the islanders who can visit out of season, or visitors who can encounter the replica after hours, once the HES staff have left and the last ferry is away for the day. For some the experience is rendered more profound by the evening shadow of the replica cast on St Columba’s Shrine. Tracey, an American holidaying on Iona sums this up in her description of the replica as ‘beloved of the shadow – it moves the people who come here’ (). The shadow is now thought to be a deliberate design feature of the eighth-century craftsmen, a feat unintentionally recreated when the replica was erected in 1970 against the backdrop of the Shrine that, until its recreation in 1954/55, survived as no more than low wall footings (). Regardless of its twentieth-century concrete fabric, the experience has a timeless quality, which the original in the museum no longer conveys in the same way. As Dora reminds us, ‘emotion springs up unbidden, and the museum doesn’t do that for me’.

Figure 6. St John’s Cross (the reconstructed original) standing in front of the Abbey ruins in a postcard from 1927 or shortly after. Copyright: J Valentine & Sons.

Open to the weather and skies, the monuments evoke ‘something higher’, explains Andrew, a heritage professional. There is a metaphorical and physical ‘surrender’ to nature’s rhythms, and the aging that results contributes to the idea that outside the monuments, including the replica, have lives. The recreated Benedictine buildings and reconstructed Shrine form a theatrical backdrop. The place hardly resembles an eighth-century monastery, but this is a real experience nonetheless. Some visitors are uncomfortable with the lack of ruins – Heidi, a visiting American academic, was one of several people effectively ‘looking for the ruins within the reconstruction’. More frequently locals and visitors talk in a positive way about renewal, resuscitation, rebuilding, reimagining, recreating.

Given the visual power of the replica outside, it is hardly surprising that HES’s 2013 redisplay of the SJC and its fellows employs son et lumière to stimulate the senses and heighten the emotions of visitors: to re-invigorate it as a monument, albeit evoking past rather than present times. It achieves this impressively, in a small, single-cell, chapel-like building, with rotating diurnal light (but no shadow) and associated sound effects evoking the Gaelic, Columban-period monastery in three and a quarter-minute rounds. As Isla summed up, the SJC in the museum is like a ‘powerful ghost or spectre’, a ‘tangible presence, and […] it’s trying to create the intangible presence roundabout it’. Accordingly, for some, the overall experience in the museum is more moving than the outside replica experience, with an immediacy that invites (forbidden) touch.

The original and the replica thus mutually reinforce each other’s significance, while simultaneously invoking complex relationships to place and different forms of aura and authenticity. Although at a spiritual level Gertrude might argue that the replica is ‘sacrosanct to God and not the location’, the replica acquires aura and authenticity because it replaces something important that is lost and illuminates the personality of the original with its shadow-casting. The experience of authenticity is not just bound up with the immediate space the replica occupies, but also the desires, expectations and realities of experiencing the Abbey and Iona more widely. Locale and atmosphere (Lowenthal Citation1985, 240–41) are germane, but these are bound up in social networks as well as aesthetics. What then happens as people encounter the replica close up, and experience its materiality?

Material evidence of ‘pastness’

A long-standing body of writing and research (e.g. Ruskin Citation[1849] 1865; Lowenthal Citation1985; Holtorf Citation2013, Citation2005; Douglas-Jones et al. Citation2016) points to the importance of material transformation, ruination and decay in the production of ‘age-value’ (Riegl Citation[1902] 1982) and the experience of authenticity. In keeping with this material aesthetic, we found our interviewees generally like things to feel unaltered, and unmediated. It is for this reason that many of them expressed a fondness for the unreconstructed [but conserved] Iona Nunnery, and the importance of being able to read the ruins within a building, or somewhere that their imagination can reign. They also pointed to the importance of patina derived from weathering, decay and the growth of lichen and related plants. This creates ambivalence towards the engineered, pre-stressed concrete that makes up the fabric of the SJC replica (made to withstand winds of up to 120 mph). For John Lawrie the artist who cast it, weathering well therefore means that the surface is not decaying, whereas nearly everyone else needs the replica to be ageing gracefully, showing visible signs of its life-span. Poring over the surface, local resident Emma was delighted to find lichen, while others were pleased that the seam (a deliberate design feature, to make it clear it is a replica) is looking less obvious. Regular visitor Roderick has known the replica all its life, and for him, ‘with the growth on it, the lichen and so on, I think it looks very authentic, very original almost’.

It seemed to us that it was often a badge of honour to be able to recognise that the cross is a replica, but many of our interviewees did not know it was a copy, or what it was made of (indeed, this did not necessarily matter). The replica was described by some as ‘too crisp’, although its profile is actually based on plaster casts made from the original, and its makers were at pains to address ‘pastness’, with their efforts to match both the colour and geological fabric of the original in its aggregate. Lawrie hand-finished the exposed aggregate to enhance its ‘worn’ qualities, a modern attribute that heritage professional, Andrew, attributed to age. But while concrete may gain some growths, it does not erode like stone. For some it can still look ‘too new’, while for others the replica’s apparent crispness is a virtue; as Ruben observed there is ‘information trapped in there, there’s knowledge preserved’.

When people recognised or knew the cross to be concrete, this could evoke a chain of reactions as they actively negotiated its implications. Those involved in its manufacture admire good concrete and its artistic potential, but for many it has negative connotations, at least in heritage contexts. Fundamentally, it is regarded as a new, industrial-age material that involves no skills and little or no craftsmanship. Accordingly, it invokes negative responses, not least in conservation circles where, as Ruben notes, ‘over decades of my work life, [I’ve had it drilled into me] that there’s something not quite right and kosher about concrete’.

There is therefore something about knowing the replica is concrete that has a negative impact, arguably more so than it being a replica. This is because of what Forty (Citation2016, 10–11) summarises as concrete’s multiple and seemingly contradictory characteristics and associations: ‘liquid/solid, smooth/rough, natural/artificial, ancient/modern, base/spirit’. Concrete is visibly not an anachronism, one of the three processes that Lowenthal (Citation1985, 241) argues help people to recognise things as being of the past. Nonetheless, touch, and occasionally smell and taste, emerged as important ways that people sought to connect with the subject of their interest, whether replica or historic fabric. Commonly, the reason cited for touching is to make a connection between the past and present, with its ineffable rewards. ‘I feel I can touch and feel the history and it sends a shiver down my spine, it really does’, said Annie, a steward at the Abbey. For Gertrude, ‘coming into relationship is signified by the act of just reaching out and patting something’, while Tracey explained that in touching something you can turn around and look either way, into the past and future. The patent modernity of the replica again places it in an ambiguous position with the result that for some it does not merit the reverence connoted by touch, or for others it requires active and conscious labour to bring it into this relation. Thus, Robin ran his fingers over the replica during his interview observing that, ‘I don’t think I would have wanted to touch it when it was new because it would have been a new object, no historical connections or anything’.

Having age-value and ‘pastness’ is bound up with the sense that the object has had a life and has experienced things. It is the connection with these experiences that renders them special. Despite the efforts of its makers and the gradual development of patina, cultural conceptions of concrete disrupt the aura of something that is otherwise widely recognised as being aesthetically pleasing, if not beautiful. Its materiality also impedes people’s understanding of the potential craft and skills behind the replica’s creation.

‘Glorious revelation’: bringing it back home

Towards the end of our interviews, we brought out photographs of the engineers and craftsmen involved in the production of the replica and invited reflections on these, seeking to understand how they might contribute to the value and authenticity of the replica (). In the second-to-last interview, we discovered that the son of one of the project engineers had made a silent cinefilm documenting the final stages of the creation of the replica in Edinburgh, its journey to Iona and erection there (MacKenzie and Foster Citation2018). Along with some of the photographs, and historic postcards, we showed this in our school workshop and used the children’s resulting artwork to understand what was important to them. All in all, these contemporary images reveal the human story behind the creation of the replica and hint at the skills involved, while the film also offers a vignette of everyday 1970 Iona, and the intersection of the replica with this.

Figure 7. ‘It makes it more real, when you see these people. You see I’m more interested in seeing the actual construction ‘cause it makes it real. And they look so chuffed. Don’t they?’ (Peter). Engineer John Scott, conservator Tam Day, foreman plaster Jackie Drysdale and artist John Lawrie stand in front of newly completed replica in Edinburgh. © Courtesy of HES (Photographer Arthur MacGregor).

Some of our interviewees were not particularly convinced that the photographs changed their views, the most extreme perhaps being heritage professional Mark, for whom ‘all replicas are ultimately fakes’. However, a greater nuance did usually reveal itself, despite people’s initial reactions. The images shed light on the replica’s early biography and the people involved in its creation, as Isla highlights:

I think the replica tells a contemporary human story of commitment and endeavour, connected to the cross, and connected to the wider importance of the cross, and the wider religion on Iona. So I think it’s a, it’s a continuity of care, it’s a continuity of belief, whether that’s a religious belief, or a belief in the job you’re doing as a craftsperson, or a belief in the job you’re doing as an engineer. I think, for me, it’s the human story.

A sense emerged that the replica involved high levels of investment, being handmade by skilled and connected craftsmen who took a big pride in their work. If it mattered to them it should matter to the wider community. Links were also created to the craftsmen who rebuilt the Abbey. The replica project was largely undertaken by Iona lovers rather than the permanent residents or the IC (Foster Citationforthcoming), and Tom and Molly respectively recognised it as a ‘passion thing’ and ‘passion project’. During our workshop at the school, children responded in different ways, often making clear distinctions between replica and original (and even in one case the 3D digital model). Nevertheless, the majority were captivated by the story of the replica as revealed by the images and cinefilm. In their artwork and discussions, they made meaningful links with people and places familiar to them (; cf. Jones Citation2016, 145).

For the poetic and deeply spiritual Gertrude, the photographs became a ‘glorious revelation’. In common with a notable number of other interviewees, the dedication and skills of honest craftsmen, what she described as ‘God’s workmanship […] God’s masterpieces’, was also imbued with sanctity, something that should be acknowledged as an act of worship. Accordingly, a direct link was often implied between these craftsmen and the monks who made the original cross. For Gertrude the replica also acquired metaphorical interest as she drew on George Herbert’s phrase ‘heaven in ordinarie’ (see opening quote). Staying at the Findhorn Foundation retreat, belonging to an organisation focussing on the ‘intelligence of nature’, Donna also expressed a sense of revelation. Concerned about what she feels is a lack of ‘energy’ in concrete, the photographs evoked what she called the ‘alchemy of manufacture’, brought about by ‘intelligent and astute gentlemen’.

The images thus provided our interviewees with the necessary personal hooks into the replica’s biography. They also generated a form of enchantment associated with the transubstantiation of materials and the potency of coming into existence (cf. Gell Citation1992). As Molly put it, ‘information is formational’. Interviewees gained insights that invited them to think differently about their responses to the materiality of the cross. This highlights again the paradoxes associated with established thinking surrounding replicas in heritage contexts. While their status as copies is expected to be documented, the people and materials involved in their production is often hidden, and their form and appearance is such that they do not mark themselves out in any obvious way from their historic originals. In contrast, by revealing the human investment, craft and materiality involved in the production of the SJC replica – showing what Gertrude called its ‘displaced workmanship’ – quite literally exposed its heart, and in doing so it could be said to have acquired some soul.

Concluding discussion

authentic doesn’t mean from the seventh century. Authentic means that it still carries its significance in the community […] authenticity is like legitimacy. It’s in the eyes of the grantor [and happens] when the heart is moved (Dora)

there is no sense in which I need to see the real thing for the experience to be authentic – it’s the symbolism, the narrative, the interpretation of the thing that’s important rather than the thing itself (Gordon).

Every replica will find itself in unique circumstances, and Iona is of course unusual in many ways for reasons we have explored. Arguably given its nature and biography, the SJC replica is a celebration in concrete, and a celebration of concrete. It is situated in a complex web of meaningful contemporary and historic relationships, a world that we gained an insight into through ethnography, alongside complementary historical research (Foster Citationforthcoming). But its treatment is perhaps typical of Western heritage management practices. Of the features at the (recreated) Abbey that it is technically possible to designate as scheduled monuments or listed buildings, only the SJC replica has been excluded. There is the whiff of traditional heritage discourse about what is of value and deemed significant, emanating from modernist attitudes that place replicas in secondary positions and locate authenticity ultimately in the fabric of historic originals (see Foster and Jones Citationin press, for a discussion of the broader heritage implications of this study).

Traditional ideas about replicas and materials such as concrete are a live issue in the case of the SJC replica, particularly for some cognoscenti, whether Iona residents, visitors or heritage professionals (cf. Lowenthal Citation1985, 295). For Lowenthal (Citation1992), a replica is made authentic by hard work (so it closely mimics the original). Our research suggests that replicas acquire aura and authenticity when they are recognised as things in their own right, socially embedded and inextricably linked to the expectations and experience of their materiality, setting and place. The presence of the SJC replica permits a contemporary phenomenological experience that evokes symbolism and stories, rather than ‘adding originality’ in the way that Latour and Lowe (Citation2011, 285) appear to suggest. The replica’s evening shadow setting on St Columba’s Shrine, can still do something ineffable for someone who knows the SJC is a concrete replica, even if that knowledge in some way impedes their ability to just enjoy it for what it is. To an island child, born 40 years or so after the replica was erected, it’s ‘a real story and people realy [sic] did look like this’ (). Such perspectives invite serious reflection.

Figure 8. Child’s artwork inspired by the biography of the St John’s Cross replica. By kind permission of Iona Primary School.

We therefore call for a new theory of replicas that encompasses the part that networks of relations – between people, objects and places – play in the production and negotiation of authenticity, and the ways these are embodied in the biographies and materialities of things. Our research shows that this applies to replicas, as well as historic originals. They can acquire authenticity and ‘pastness’, linked to materiality, craft practices, creativity, and place. Yet, their authenticity is founded on the networks of relationships between people, places and things that they come to embody, as well as their dynamic material qualities. The cultural biographies of replicas, and the ‘felt relationships’ associated with them, play a key role in the generation and negotiation of authenticity, while at the same time informing the authenticity and value of their historic counterparts through the ‘composite biographies’ produced (see Jones et al. Citation2017 for a discussion of parallel processes with respect to digital, ‘virtual’ replicas).

The paradox for any replica is that, if it works well as the proxy it is intended to be in the context of authorised heritage discourse, its own life story is often rendered materially invisible, indeed deliberately so (Cameron Citation2007, 60, 70). However, this denial of its biography undermines people’s ability to connect to the networks of people, places and objects in which it is embedded, and which in turn inform the experience of authenticity. If it shows any independent evidence of ‘pastness’ then it might indeed acquire the sense it is old and has had a life, imagined or real, but it risks betraying its intended fidelity to its parent when it does so, because it has acquired its own trajectory of physical change. So, what happens if people allow for the possibility that a replica is a thing in its own right, albeit a thing that stands in complex relationship to another thing? We experienced this when we showed our interviewees images relating to the making of the SJC replica. The insights they gained into the replica’s creativity and craft, as well as the sense of the replica as something with its own life story, allowed interviewees to negotiate emergent forms of aura and authenticity.

Thus, as things in their own right, replicas can ‘work’ for us if we let them, particularly if clues are available about their makers’ passion, creativity and craft. For the Palmyra arch replica temporarily placed in Trafalgar Square in 2016, Kamash (Citation2017) suggested that the lack of information for visitors was possibly intended to make encounters with it more magical. Our study reveals the magic that happens when you add an evocative picture to the frame, allowing people to connect to a replica’s own unique biography. From out of the concrete come non-concrete, intangible connections, as the replica acquires a social life and ‘felt relationships’ are generated.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the eloquence, kindness, grace and tolerance of our interviewees, the hospitality and support of those who live and/or work on Iona, and the many other friends we made along the way. Richard Strachan and the HES Iona Abbey team, as well as the Abbey’s resident Iona Community, facilitated access and offered various kinds of support, including a room to work in. Dr Stuart Jeffrey, Glasgow School of Art, worked with us on the digital elements of the project, and helped to run the school workshop. He also undertook three interviews, and was a critical friend throughout. Rod McCullagh supported the school workshop. Friends, colleagues and HES staff provided helpful feedback at presentations and on drafts, and we are also grateful to our peer reviewers for insightful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sally M. Foster

Sally M. Foster joined Stirling as Lecturer in Heritage and Conservation in 2014. Prior to returning to academia in 2010, she worked in the heritage sector for over 20 years, latterly heading a Historic Scotland designation team. She is particularly interested in critical histories of heritage and museum practices and unites several interests by employing composite biographies of early medieval carved stones and their copies to explore such issues.

Siân Jones

Siân Jones is Professor of Environmental History and Heritage at the University of Stirling. She is an interdisciplinary scholar with expertise in cultural heritage, as well as on the role of the past in the production of power, identity and sense of place. Her recent projects focus on the practice of conservation, the experience of authenticity, replicas and reconstructions, approaches to social value, and community heritage.

References

- Bhattacharjee, K. 2018. “Once upon a Place: The Construction of Specialness by Visitors to Iona.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh.

- Cameron, F. 2007. “Beyond the Cult of the Replicant: Museums and Historical Digital Objects—Traditional Concerns, New Discourses.” In Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage, edited by F. Cameron and S. Kenderdine, 49–75. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Douglas-Jones, R., J. J. Hughes, S. Jones, and T. Yarrow. 2016. “Science, Value and Material Decay in the Conservation of Historic Environments.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 21 (September–October): 823–833. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.03.007.

- Ferguson, R. 2001. George MacLeod. Founder of the Iona Community. 2nd ed. Glasgow: Wild Goose Publications.

- Forty, A. 2016. Concrete and Culture. A Material History. London: Reaktion Books .

- Foster, S. M. 2001. Place, Space and Odyssey. Exploring the Future of Early Medieval Sculpture. Rosemarkie: Groam House Museum.

- Foster, S. M., and S. Jones. 2008. “Recovering the Biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Cross-Slab.” In A Fragmented Masterpiece. Recovering the Biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish Cross-Slab, edited by H. James, I. Henderson, S. M. Foster, and S. Jones, 205–284. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- Foster, S. M. 2010. “The Curatorial Consequences of Being Moved, Moveable or Portable: The Case of Carved Stones.” Scottish Archaeological Journal 32 (1): 15–28. doi:10.3366/saj.2011.0005.

- Foster, S. M. 2017. “Icolmkill: The Ruins of Iona.” In Writing Britain’s Ruins, edited by M. Carter, P. N. Lindfield, and D. Townsend, 158–161. London: British Library.

- Foster, S. M. 2018. “Replication of Things: The Case for Composite Biographical Approaches.” In Remakings: Replications and Reproductions in the Nineteenth Century and Beyond, edited by J. F. Codell and L. Hughes, 23–44. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Foster, S. M. forthcoming. My Life as a Replica: St John’s Cross, Iona.

- Foster, S. M., A. Blackwell, and M. Goldberg. 2014. “The Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Replicas for Object Cultural Biographies: Lessons in Duplication from 1830s Fife.” Journal of Victorian Culture 19 (2): 137–160. doi:10.1080/13555502.2014.919079.

- Foster, S. M., and N. G. W. Curtis. 2016. “The Thing about Replicas: Why Historic Replicas Matter.” European Journal of Archaeology 19 (1): 122–148. doi:10.1179/1461957115Y.0000000011.

- Foster, S. M., and S. Jones. in press. “The Untold Heritage Value and Significance of Replicas.” Conservation and Management of Heritage Sites 21 (1).

- Gell, A. 1992. “The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology.” In Anthropology, Art, and Aesthetics, edited by J. Coote and A. Shelton, 40–63. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Graves-Brown, P. 2013. “Authenticity.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, edited by P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison, and A. Piccini, 219–231. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- GSoASimVis (Glasgow School of Art School of Simulation and Visualisation). [2017] 2018. “St John’s Cross, Iona.” https://sketchfab.com/GSofASimVis

- Handler, R. 2001. “Authenticity, Anthropology Of.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, edited by N. J. Smesler and P. B. Baltes, 963–967. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Holtorf, C. 2005. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas. Archaeology as Popular Culture. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Holtorf, C. 2013. “On Pastness: A Reconsideration of Materiality in Archaeological Object Authenticity.” Anthropological Quarterly 86 (2): 427–443. doi:10.1353/anq.2013.0026.

- Jeffrey, S. 2015. “Challenging Heritage Visualisation: Beauty, Aura and Democratisation.” Open Archaeology 1 (1): 144–152. doi:10.1515/opar-2015–0008.

- Jones, S. 2004. Early Medieval Sculpture and the Production of Meaning, Value and Place: The Case of Hilton of Cadboll. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland.

- Jones, S. 2010. “Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves. Beyond the Deconstruction of Authenticity.” Journal of Material Culture 15 (2): 181–203. doi:10.1177/1359183510364074.

- Jones, S. 2016. “Unlocking Essences and Exploring Networks. Experiencing Authenticity in Heritage Education Settings.” In Sensitive Pasts? Questioning Heritage in Education, edited by C. van Boxtel, M. Grever, and S. Klein, 130–152. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Jones, S., S. Jeffrey, M. Maxwell, A. Hale, and C. Jones. 2017. “3D Heritage Visualisation and the Negotiation of Authenticity: The ACCORD Project.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (4): 333–353. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1378905.

- Kamash, Z. 2017. “‘Postcard to Palmyra’: Bringing the Public into Debates over Post-Conflict Reconstruction in the Middle East.” World Archaeology 49 (5): 608–622. doi:10.1080/00438243.2017.1406399.

- Knoblauch, H. 2005. “Focused Ethnography.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 6 (3): Art. 44. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/20/43

- Latour, B., and A. Lowe. 2011. “The Migration of the Aura, or How to Explore the Original through Its Facsimiles.” In Switching Codes. Thinking through Digital Technology in the Humanities and the Arts, edited by T. Bartscherer and R. Coover, 275–297. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lending, M. 2017. Plaster Monuments. Architecture and the Power of Reproduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Low, S. M. 2002. “Anthropological-Ethnographic Methods for the Assessment of Cultural Values in Heritage Conservation.” In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage, edited by M. de la Torre, 31–49. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Lowenthal, D. 1985. The Past Is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lowenthal, D. 1992. “Authenticity? the Dogma of Self-Delusion.” In Why Fakes Matter: Essays on Problems of Authenticity, edited by M. Jones, 184–192. London: British Museum.

- MacArthur, E. M. 2003. Iona Celtic Art. The Work of Alexander and Euphemia Ritchie. Strathpeffer: The New Iona Press.

- MacArthur, E. M. 2007a. Iona. The Living Memory of a Crofting Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- MacArthur, E. M. 2007b. Columba’s Island. Iona from Past to Present. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Macdonald, S. 2013. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. London: Routledge.

- MacKenzie, M., and S. M. Foster 2018. MM Films present A Study in Concrete by Exposagg: St. John’s Cross, Iona (1970). M MacKenzie in interview with S Foster, filmed by the University of Stirling. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cSIcMll4Mo

- Muir, A. 2011. Outside the Safe Space. An Oral History of the Early Years of the Iona Community. Glasgow: Wild Goose Publications.

- Pink, S., and J. Morgan. 2013. “Short-Term Ethnography: Intense Routes to Knowing.” Symbolic Interaction 36 (3): 351–361. doi:10.1002/symb.2013.36.issue-3.

- Riegl, A. [1902] 1982. The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Origins. Reprinted in Oppositions 25, New York: Rizzoli.

- Robertson, W. N. 1975. “St John’s Cross, Iona, Argyll.” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 106: 111–123.

- Ruskin, J. [1849] 1865. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Stockhammer, P. W., and C. Forberg. 2017. “Introduction.” In The Transformative Power of the Copy. A Transcultural and Interdisciplinary Approach, edited by C. Forberg and P. Stockhammer, 1–17, Heidelburg: Heidelberg University Publishing.

- Taplin, D. H., S. Scheld, and S. M. Low. 2002. “Rapid Ethnographic Assessment in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Independence National Historic Park.” Human Organization 61 (1): 80–93. doi:10.17730/humo.61.1.6ayvl8t0aekf8vmy.