ABSTRACT

This article sheds light on the entanglements of difficult heritage and digital media through an ethnographic analysis of digital photography and social media practices at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin. After a discussion of the project ‘Yolocaust’, through which an artist publicly shamed the ‘selfie culture’ at the memorial, the article argues that the sweeping condemnation of digital self-representations in the context of Holocaust remembrance remains simplistic. Instead, many visitors explore and enact potential emotional relationships to the pasts that sites of difficult heritage represent through digital self-representations. This observation raises critical questions about the role of digital media in current transformations of touristic memory cultures.

Introduction

Christine's picture () would appear completely mundane at most touristic places in Berlin: a young woman, with a camera around her neck and a backpack over her shoulders, is resting at a place mentioned in probably every travel guide to the city. As she turns her face towards the camera, she performs a warm and friendly smile. Later, she uploads this picture (next to two others) on Instagram, one of the largest and currently most popular social media platforms, where she adds several hashtags, such as: ‘#memorialtothemurderedjewsofeurope #berlin #jewish #history #neverforget #lchaim #tolife #tolove’.

As these hashtags already indicate, the place at which this picture is taken is the ‘Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe’, colloquially referred to as the ‘Holocaust Memorial’ (the name which I will use in the following). Designed by architect Peter Eisenman, the memorial is a field of 2711 concrete blocks, covering 19,000 square metres in total, located in the very heart of the German capital, right next to the Brandenburg Gate and many other touristic hotspots. Below the memorial, visitors can enter an ‘information centre’ with its permanent exhibition on the history of the Holocaust. While the exhibition ‘documents the persecution and extermination of the Jews of Europe and the historical sites of the crimes’,Footnote1 the memorial above ground is designed to afford a different kind of experience. As Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett has prominently argued regarding the making of heritage, the ‘production of hereness in the absence of actualities depends increasingly on virtualities.’ (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Citation1998: 169) In the case of the Berlin memorial, at which the actualities of the Holocaust are absent, Eisenman created a material space that affords such virtualities in the form of intense emotional experience. As he puts it, the ‘space is created for loss and contemplation, for elements of memory’.Footnote2 However, Eisenman did not want to determine how visitors feel at the place. In fact, he was very much aware that: ‘People are going to picnic in the field. Children will play tag in the field. There will be fashion models modeling there and films will be shot there. I can easily imagine some spy shoot ‘em ups ending in the field. What can I say? It’s not a sacred place.’Footnote3

The openness and accessibility of the memorial, which visitors can enter without going through any kind of entrance or gate, is certainly one of the reasons why it became one of the most visited Holocaust memorials in the world and one of the most frequented heritage sites in Berlin. Its particular architecture, which affords the taking of aesthetically complex pictures, has also made the memorial extremely popular on social media. One can find tens of thousands of pictures taken here and then publicly shared online on Instagram and Facebook – including the picture of Christine.

Considering the context of the picture, Christine’s smile seems highly ambivalent. Is it appropriate to take a picture of oneself at the Holocaust memorial; a picture that clearly puts the aesthetic representation of one’s own body into the centre? Christine is very much aware of where she is. She even emphasises her awareness of the memorial’s context through hashtags such as #jewish or #neverforget. These hashtags indicate that remembering the Holocaust matters emotionally to her. Her happy smile and posture, however, suggest an emotional indifference towards the past or even, as some would say (see section 2), disrespect of Holocaust victims.

Digital self-representations, taken at the memorial and shared online, frequently materialise this very ambivalence through social media. Such pictures have repeatedly sparked conflict in not only public debates in Germany but also similar debates connected to the Auschwitz memorial in Poland or the 9/11 memorial in New York. At the heart of such conflicts lies the question of whether digital self-representations when produced at sites of difficult heritage are always practices of articulating emotional indifference towards these places and, therefore, disrespect the commemoration of a troubling past.

This chapter, therefore, takes a closer look at digital self-representations taken at the Holocaust memorial Berlin and uploaded on social media. I apply a notion of ‘digital self-representation’ which not only refers to the particular format of the ‘selfie’ as a ‘photograph that one has taken of oneself’ (Eckel, Ruchatz, and Wirth Citation2018: 4), although the selfie will play a crucial role in the following. The term ‘digital self-representations’ in this chapter refers to pictures in which a) a particular person (or group of people) is clearly at the centre of the picture; b) this person is attentive of the fact that he or she is being photographed (often facing the camera directly) and performs accordingly through a variety of facial expressions, gestures, postures, etc.; or c) the person being portrayed (and not the person taking the picture) is uploading the picture on social media in order to represent his- or herself in a particular context.

The first section of this chapter outlines the basic approach of my analysis, starting with the methods of digital ethnography, which I apply here in the context of difficult heritage and tourism to explore emotional practices that are enacted through digital self-representations and social media. The second section sets the empirical scene by describing the so-called ‘Yolocaust’ project and the surrounding conflict that emerged in public debates regarding ‘selfie culture’ at the Holocaust Memorial. I show why many observers and visitors are critical about digital self-representations and how their criticism connects to questions of emotional indifference in the context of Holocaust remembrance; however, I will also argue that the sweeping condemnation of digital self-representations remains simplistic and does not account for the complexity of these practices. Instead, as the third section shows, many visitors explore and enact potential emotional relationships to the pasts that sites of difficult heritage represent through digital self-representations. This leads towards the conclusion, in which I discuss how this kind of doing emotion constitutes different but not necessarily indifferent ways of presencing the past. These different ways of past presencing, I will argue, deviate from established practices of remembrance but are, nonetheless, meaningful for the actors involved. They unfold a particular potential especially for visitors of younger generations – the so-called ‘digital natives’ – in that they allow the exploration of personal connections to sites of difficult heritage and new forms of social exchange about shared relationships to difficult pasts.

Methods

My analysis draws upon a digital ethnography of visitors’ media practices at the Holocaust memorial both offline and online, including participant observation at the memorial, 17 face-to-face interviews with 41 visitors at the site and 24 chat interviews with users of Instagram and Facebook who had been contacted shortly (most often one or several days) after they visited the memorial and posted pictures online. The fieldnotes and interviews were triangulated with a qualitative computer-assisted analysis of 800 social media posts (again on Instagram and Facebook), about 390 of which were digital self-representations. Additionally, the qualitative analysis included 200 comments to a particular social media debate in the context of the ‘Yolocaust’ project (see below). My selection of interviewees and the selection of the 800 social media posts built upon an inductive process of identifying particular media practices, which I followed throughout my research both offline and online. This resulted in a sample of interviewees with an equal gender balance, visitors aged between 12 and 77 years (most of them between 20 and 40 years), and from 29 different countries (visitors’ names in this article are fully anonymised).

My research was guided by the principles of digital and Internet ethnography (Hine Citation2015; Pink et al. Citation2016), followed ethical principles of care in Internet research (Boellstorff et al. Citation2012: 129) and applied a rigorous digital coding procedure (using the software MAXQDA) which is based on Grounded Theory Methodology (Strauss and Corbin Citation1994), but also develops a more ethnography-oriented coding style (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011: 177–200; Breidenstein et al. Citation2015: 124–139) more relatable to general practice theories and other concepts that were operationalised in my research.

Difficult heritage

The research field in which I apply this approach can be usefully framed with the notion of ‘difficult heritage’. Sites of ‘difficult heritage’ are material reminders of ‘a past that is recognised as meaningful in the present but that is also contested and awkward for public reconciliation with a positive, self-affirming contemporary identity’ (Macdonald Citation2009: 1). In other words: difficult heritage is troubling. As Sharon Macdonald (Citation2009, Citation2015) has pointed out, Germany has been particularly invested in making such difficult heritage publicly visible, especially regarding WW2 and the history of the Holocaust. The Holocaust Memorial, located in the centre of the German capital, is part of this process and was the anchor point of controversial debates about German memory cultures for several years. During its planning phase, Jürgen Habermas (Citation1999) tellingly called it the memorial ‘that shall remain a thorn’ (my translation). Its existence is an acknowledgement of the fact that ‘apologising for past wrongs also requires a bringing of those wrongs into view’ (Macdonald Citation2015: 16).

It is worth asking here what this ‘bringing into view’ entails. One dimension of the visibility of difficult heritage is usually constituted through the curated dissemination of historical information. Museums and heritage sites inform about particular pasts by allowing visitors to engage, for example, with texts, pictures, videos and audio guides, to learn about historical facts. The second, equally important dimension of this visibility, which is always intrinsically connected to the first, is emotional. Museums and heritage sites do not only provide information, but they constitute a material basis for the unfolding of emotions in relation to specific pasts. They do not only offer particular ways of knowing, they also offer ways of feeling the past. Accordingly, as Laurajane Smith and Gary Campbell (2015) argue, it is crucial to consider the emotional and affective dimension of visitors’ experiences:

If we accept that heritage is political, that it is a political resource used in conflicts over the understanding of the past and its relevance for the present, then understanding how the interplay of emotions, imagination and the process of remembering and commemoration are informed by people’s culturally and socially diverse affective responses must become a growing area of focus for the field. (Smith and Campbell Citation2015: 455)

Emotional practices and emotional affordances

Sharing this intention, a growing body of literature has emerged throughout the last few years that takes the emotional or affective dimension of heritage and museums into account (e.g. Witcomb Citation2007, Citation2012; Macdonald Citation2013; Gregory Citation2014; Golańska Citation2015; Smith and Campbell Citation2015; Waterton and Watson Citation2015; Tschofen Citation2016; Campbell, Smith, and Wetherell Citation2017; Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2017; Smith, Wetherell, and Campbell Citation2018), including works with a focus on difficult heritage (Sather-Wagstaff Citation2017) and the Berlin Holocaust memorial in particular (Knudsen Citation2008; Dekel Citation2013; Witcomb Citation2013; Bareither Citation2019). This kind of research follows an understanding of emotions or affects as entangled with everyday practices embedded in particular social and cultural contexts especially when conducted from an ethnographic perspective. It goes beyond a simplistic distinction between ‘knowing’ and ‘feeling’ that reproduces the Cartesian dualism of mind and body. Instead, it suggests ‘that recognizing reason/cognition, affect/emotion and memory as being mutually constitutive and reinforcing of each other is a positive step for anyone interested in understanding and researching the contemporary significance of the past’ (Smith and Campbell Citation2015: 452). The cultural anthropologist Bernhard Tschofen has proposed considering the ‘emotional knowledge of the historical’ (‘Gefühlswissen des Historischen’, Tschofen Citation2016: 144) as a conceptual frame for this perspective. How we feel about the past is always intrinsically related to our implicit knowledge of it, and vice versa, we come to know the past through our bodies and feelings.

This points us to the importance of emotional engagement with difficult heritage. Here, I draw upon the concept of ‘emotional practices’ by Monique Scheer (Citation2012, Citation2016) and the concept of ‘affective practices’ by Margaret Wetherell (Citation2013; Wetherell, Smith, and Campbell Citation2018), which can be productively brought together with other ethnographic or qualitative approaches to the study of emotions in everyday life (e.g. Abu-Lughod and Lutz Citation1990; Hochschild Citation2003; Ahmed Citation2014; Reckwitz Citation2017). Generally speaking, both concepts apply the notion of practice, in the sense carved out by practice theories (and in close relation to the work of Pierre Bourdieu), to understand emotions or affects as part of routinised doings in everyday life. As Scheer puts it, emotions are not something we have, emotions are something we do in social and cultural encounters (Scheer Citation2016: 16). Neither concept follows a conceptual distinction between emotions, affects and feelings, as is made in some studies of emotions. Praxeological or praxeographic approaches tend to treat these terms in close relation to each other and often interchangeably. Respectively, what I label emotional practices in the following could also be called affective practices. The two variations certainly have different heuristic advantages and disadvantages, but both achieve the same analytical goal here. They allow one to analyse and describe with ethnographic methods how emotions (or affects) are enacted in relation to difficult heritage.

This chapter focuses on emotional practices enacted through digital self-representations and the sharing of these pictures as well as the adding of captions and comments (including hashtags and emojis) on social media. These practices build upon the particular emotional affordances of digital cameras, smartphones and social media platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook. As I have argued elsewhere, ‘emotional affordances’ can be understood as capacities to enable, prompt and restrict the enactment of specific emotional experiences unfolding in between media technologies (or material environments) and an actor’s practical sense of their use (Bareither Citation2019: 15). This means that it is crucial for my ethnographic analysis of digital self-representations to account for how the particular functions of smartphones and other digital cameras, as well as social media platforms, enable and restrict specific ways of articulating, mobilising and sharing emotions.

Digital self-representations and social media in touristic contexts

Visitors who use digital media to engage emotionally with memorial sites are usually tourists and follow particular touristic routines. Thus, the particularities of tourist photography ‘as a socially consumptive and constructive practice that performatively produces and uses visual, communicative culture’ come into play (Sather-Wagstaff Citation2008: 97). As Jonas Larsen has pointed out, such practices do not only include the moment of taking a picture. Instead, they include ‘looking for, framing and taking photographs, posing for cameras and choreographing posing bodies’, followed by ‘editing, displaying and circulating photographs’ as well as their movements through ‘wires, databases, emails, screens, photo albums and potentially many other places’ (Citation2008: 143; also see Larsen Citation2014).

All of these practices can be related to what John Urry famously called the ‘tourist gaze’ (Urry and Larsen Citation2011; in relation to the Holocaust memorial, also see Knudsen Citation2008). This is a form of touristic looking through which the landscapes, scenes, people or objects encountered by tourists are visually consumed. Photography plays a crucial role in this process as it allows tourists ‘to make fleeting gazes last longer’ (Urry and Larsen Citation2011: 156) and, therefore, ‘[m]uch tourism becomes […] a search for the photogenic’ (178).

While the notion of the ‘tourist gaze’ contributes to understanding the aesthetic and emotional dimension of tourist photography, my own empirical research demonstrates that tourist photography can be much more than a form of pleasurable visual consumption. Visitors do not only consume the place through digital photography at the Holocaust Memorial, but they also emotionally engage with the place and the past it represents.

Similar observations have been made by other scholars regarding tourist photography at sites of difficult heritage or traumatic memory (e.g. Sather-Wagstaff Citation2008; Hilmar Citation2016; Douglas Citation2017). Looking at the practices of ‘picturing experience’ at the 9/11 memorial in New York, Joy Sather-Wagstaff argues that photographs ‘are devices for the performance of subjectivities, for the making of various social relationships and cultural realities, and most importantly, for memory, recalling the past in service to the present’ (Sather-Wagstaff Citation2008: 80). In a similar vein, Till Hilmar observes at the Auschwitz memorial site that with ‘their pictures, visitors not only seek to emphasise and materialise certain details about the past, but also to express modes of encountering and experiencing the past on site’ (Hilmar Citation2016: 457).

In the following, I build upon these previous studies to ask in greater detail about the role of visitors’ digital self-representations as emotional practices in relation to difficult heritage while acknowledging the particular role of social media in this process. The function of digital photography as a form of emotional engagement comes to light especially when visitors share their pictures on social media; pictures are often contextualised with captions, comments, hashtags and emojis, emphasising how the person taking the picture (or being represented in it) relates to the past that the memorial represents. Since these practices are an integral part of the memory experiences of millions of visitors, it seems crucial to pay particular attention to their specific implications.

‘Yolocaust’ and ‘selfie culture’

Before I go on to describe various kinds of digital self-representations and their contextualisation in detail, this section sets the empirical scene by describing the public negotiation of ‘selfie culture’ and the heated criticism of digital self-representations in relation to difficult heritage. In early 2017, the frequently posted digital self-representations taken at the Holocaust Memorial were noticed by Jewish-German satirist Shahak Shapira, who responded to them with the infamous ‘Yolocaust’ project. The project title is a combination of ‘Holocaust’ and the term ‘Yolo’, commonly known as an abbreviation for the saying ‘you only live once’ and usually associated with a young ‘Hipster’ generation. For this project, Shapira edited digital self-representations which were taken at the memorial and put historical footage from concentration camps, including dead bodies of victims, into the background. After he published these remixes on a website, the visitors who took the original pictures were supposed to write him a message and ask to be ‘undouched’ by him if they want the pictures to be taken offline again. All the self-representations he used were publicly accessible at the time. Some of them were pictures with people simply smiling into the camera while taking a selfie. Others showed acrobatic moves that visitors performed between the blocks. One picture was particularly extreme, as it showed two young men jumping on the blocks with the caption ‘Jumping on Dead Jews @ Holocaust Memorial’, which received 87 Likes before Shapira discovered, altered and re-posted it.

By using these examples and manipulating them with new background pictures showing Holocaust victims, Shahak Shapira suggests a very specific interpretation of the memorial. He suggests that the place should be experienced as a direct link to the horrors of the Holocaust and, accordingly, it should serve as a source of inspiration for solemn reflection and collective remembrance. His project ‘Yolocaust’ went viral on social media and was recognised widely by the German and international press. Shapira claims that he received overwhelmingly supportive emails not only from many viewers, but also from an international research institute and even the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem. There were also critical voices among them, including the Memorial’s architect, Peter Eisenman.Footnote4 Despite these critical voices, however, a lot of the feedback to the ‘Yolocaust’ project in both the German and international press was positive. As Shapira explained later, shortly after the project went online, 2.5 million people visited the website and all of the portrayed visitors contacted Shapira to apologise and asked to be ‘undouched’ by him. As promised, he took the pictures off the website and left only a written documentation of the project online.

Needless to say, the pictures had already been copied and distributed countless times and are still easily publicly accessible through various websites. The most popular documentation of the project, including the original pictures, is a video summary produced by the Facebook page AJ+, which clearly takes a positive stance towards the position of Shapira and speaks out against what it refers to as ‘selfie culture’.Footnote5 This video received more than 79 million views, about 23,000 ‘Facebook reactions’ (mostly ‘likes’, but also ‘angry’ and ‘sad’ emojis), was shared more than 20,000 times and publicly commented on more than 2,300 times.

Shaming the ‘selfie monsters’

Although some of these comments take the video as a starting point for lengthy explanations of conspiracy theories (Holocaust denial included) or discussing other political issues, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, several hundred of them take a particular stance towards the ‘Yolocaust’ project. A qualitative computer-assisted analysis of a random sample of 200 of these last kind of comments shows that most them (about three-quarters) are supportive of Shapira’s intention. One viewer writes: ‘Kudos to the creator – these selfie monsters have lost all humanity and respect for sanctity of memorials, temples, – it’s good they get shamed in public. Need more such righteous “warriors” online.’ Another one comments more diplomatically: ‘The generation of selfie needed a lesson learnt – to be less self-centred of what you want to do but rather how others might be affected by what you do. The memorial belongs to those who died tragically and not a backdrop for those who want to show off on FB [Facebook, C.B.] they’ve been there.’

Terms such as ‘selfie monsters’ and ‘the generation of selfie’ are frequently reappearing, being prompted by the video itself, which, at one point, posits the threat: ‘But selfie culture beware – ’, before showing Shapira again who states he will do this again in two weeks if visitors don’t stop doing ‘stupid sh*t’. Here, the term ‘selfie culture’ does not only refer to the particular routine of self-photography (the ‘selfie’). Instead, the term functions as an idiom to denote a culture in which the aesthetic representation of oneself is apparently valued higher than engaging in ‘appropriate’ practices of remembrance. Tellingly, the terms most frequently appearing in the comments to the video documentation are ‘respect’ and ‘disrespect’, which are used to describe the inappropriateness of these ‘acts of millennialism’, as another viewer frames them. Comparisons are made to similar practices that viewers have personally observed at other memorial sites, for example, the memorial and museum at Auschwitz-Birkenau or the 9/11 memorial in New York.

From the perspective of emotional practice theory, these practices of public shaming function as regulating emotional practices, sanctioning specific kinds of emotions that are considered wrong or inappropriate by a particular group of actors. In doing so, they also attempt to establish a clear-cut dichotomy between ‘respect’ and ‘disrespect’, ‘appropriate’ vs. ‘inappropriate’, ‘righteous warriors’ vs. ‘selfie monsters’. These seemingly clear-cut dichotomies are not only emerging in the context of the ‘Yolocaust’ conflict. They appear quite regularly at the site as well, for example, when tour guides tell visitors about the inappropriateness of photographic self-representation at the site, or when visitors told me in interviews how they were ‘shocked’ by other people taking selfies. The reason for this ‘shock’ – both offline and online – is that, to many observers, selfies and other forms of digital self-representation seem to demonstrate, enact and propagate an emotional indifference towards the Holocaust.

Indifference in holocaust commemoration

Why this kind of indifference matters is probably best reflected through the speech ‘The Perils of Indifference’ that Eli Wiesel, Holocaust survivor, Nobel laureate and historian, gave at the White House on 12 April 2012 1999, in the presence of Bill and Hillary Clinton.Footnote6 ‘What is indifference?’, Wiesel asks. ‘Etymologically, the word means “no difference”. A strange and unnatural state in which the lines blur between light and darkness, dusk and dawn, crime and punishment, cruelty and compassion, good and evil.’ He continues to describe the role of indifference for the Holocaust with poetic accuracy: ‘It is, after all, awkward, troublesome, to be involved in another person’s pain and despair. Yet, for the person who is indifferent, his or her neighbor are of no consequence. And, therefore, their lives are meaningless. Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the other to an abstraction.’ And he observes: ‘In a way, to be indifferent to that suffering is what makes the human being inhuman.’

Here, the question of emotional indifference is far more than a question of attitude; being indifferent towards the Holocaust becomes a constitutive moment of being not human. From this perspective, it is only logical that the public portrayal of emotional indifference through digital self-representations appears problematic to many observers. After all, a rationalised mass genocide on the scale of the Holocaust may, indeed, happen again. ‘It happened, therefore it can happen again: that is the core of what we have to say’ (Levi Citation2017: 186). This phrase by Holocaust survivor Primo Levi is quoted above the entrance to the Information Centre below the Holocaust Memorial and, thus, serves as a guiding principle for the memorial as a whole. In a world in which right-wing populism is on the rise on a global scale, this fear seems more justified than ever since the end of WW2.

In a chat-interview with Adam, a young man from New York, who was at the time writing a screenplay and sent me detailed, almost poetic reflections on his experiences at the Holocaust memorial, picks up on this point. His elaborate description is worth quoting in detail:

In the age of social media and the total ubiquity of mobile phones, many people seem unable to experience anything directly anymore, instead filtering their daily interactions through the lens of their phone screen (or laptop screen). And when you live that way, removed from true ‘first-hand’ experience, things just don’t have the same gravity. A memorial is then just a place you ‘see’, rather than a place you go to feel. That’s what it is, isn’t it? People visit a place like the Holocaust Memorial or Auschwitz-Birkenau, and they are unable (or perhaps, on a subconscious level, unwilling) to have an experience of feeling. The mass extermination of millions of Jews (as well as homosexuals and other groups) should affect us all on a very deep level, disturb us, break our hearts and make us vigilant in working to ensure nothing like this could ever happen again. But I’m afraid it actually could, in some way, happen again, because so much of the population has become desensitised to such a degree that they can’t tell when bad things are on the horizon.

Adam directly relates his observation that more and more people seem to be emotionally indifferent towards the Holocaust to ‘the age of social media and the total ubiquity of mobile phones’. The project ‘Yolocaust’ aims in the same direction, although it takes much more extreme measures and publicly shames those who appear to portray their emotional indifference towards the memorial.

The question remains whether digital self-representations do indeed perform emotional indifference; and, if they do, is that all that they do? Is every kind of digital self-representation the same? Does a picture in which a person is aesthetically highlighted in front of the Holocaust memorial automatically disrespect Holocaust victims and the culture of their remembrance?

Digital self-representations and emotional practices

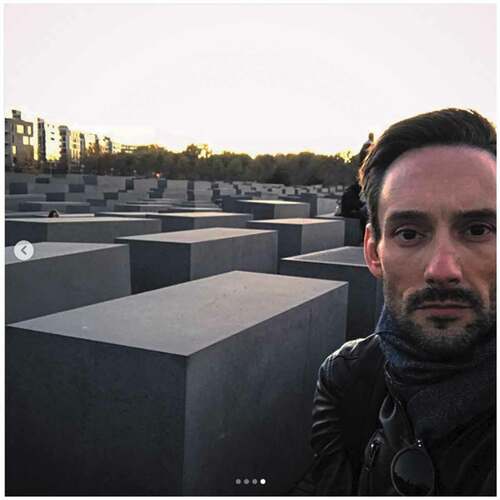

An ethnographic analysis of the variety of digital self-representations and related practices both offline and online clearly demonstrates that this is not the case. Considering Adam’s critical reflection quoted above, it might be surprising that he, in fact, took a selfie at the Holocaust memorial himself and shared it on social media ().

As already described above, you will find countless digital self-representations on Instagram and Facebook taken at the memorial, often selfies, some of them taken with a selfie-stick. First and foremost, this raises the question why one would take a picture of oneself in front of a memorial in the first place. As Anja Dinhopl and Ulrike Gretzel point out: ‘While tourist photography and the tourist gaze shape each other, tourist photography is also a performance of the self in tourism’ (Citation2016: 132). They use particularly the example of tourist selfies to argue that the space or scene of the tourist gaze fades gradually into the background in much contemporary tourist photography, and ‘[a]s the tourist destination becomes the distant backdrop or prompt or completely disappears from the photo, the self becomes elevated as a touristic product – it is what tourists are there to consume’ (134).

This argument relates to the notion of the ‘tourist gaze’ (see above) and observes a process of touristic consumption regarding one’s own bodily presence at a particular touristic site. By translating this observation into the language of emotional practice theory, I argue that digital self-representations in the context of tourism enact pleasurable experiences as they perform and materialise an aesthetic visual artefact which allows for good feelings regarding one’s own body and its presence within a ‘remarkable’ environment.

However, the fact that a digital self-representation allows one to mobilise good feelings about oneself and/or about one’s own presence at a particular site does not exclude the possibility that it constitutes, simultaneously, a practice of emotional engagement with the memorial. Adam already articulates this through the caption in his social media post, where he states that: ‘I found it to be the most meaningful and impactful monument – of any kind – that I’ve ever visited.’ Considering that Adam is very critical about smartphones and social media, this might make us wonder why he would choose the particular format of the selfie (next to two other pictures) to articulate this experience. In our interview, Adam explains: ‘In taking my photo [the selfie, C.B.], my intention was to say, in an earnest, honest and straightforward way, “I was here. I witnessed this, and I’m sharing it on social media because this was a powerful experience for me, an important and humbling experience that I want to share with friends and loved ones”.’

Putting oneself into the picture

Adam’s case demonstrates a simple fact: digital self-representations can be a form of aesthetic self-representation and, at the same time, a practice of emotional engagement. Kate Douglas observes in her analysis of the format of the selfie at trauma memorial sites that ‘selfies have the ability to be acts of witness: as engaged responses, as demonstrations of affect and as admissions of complicity and/or communion’ (Douglas Citation2017: 13). If we acknowledge this fact, the analytical perspective shifts to the question how visitors emotionally engage with the memorial through such pictures (not only selfies but all digital self-representations). Similar to Adam, many visitors use digital pictures to articulate commemoration and compassion with Holocaust victims, but they do so in very different ways.

Benedikt, for example, decided to share a selfie on which he cried while visiting the memorial (). His social media post is contextualised with the caption: ‘You can’t do much … just stop and ask yourself «What have we done?!»’ The caption is followed by several hashtags, one of which is ‘#cry’. In our chat interview he explains: ‘It was just an honest moment. Not pretending to be fake with all filters […] I just wanted to be very honest about my visit there. That place touched me deeply and that’s what I felt in the moment. […] I felt just sadness … Just that actually.’

Such pictures, in which the visitors look directly into the camera, are not the only kind of digital self-representations relevant here. Pictures in which visitors are portrayed (often through pictures taken by friends and family) in a situation in which they interact with the memorial are equally important. These pictures might include portraits of people who touch the memorial or who are wandering in-between the blocks while appearing to be lost in their thoughts. Visitors often ask their friends or family to take a picture of them while they sit on one of the blocks and look into the far.

Katarina and Haasim, for example, took this kind of picture in almost exactly the same position in front of almost exactly the same background (on different days) and both uploaded it on Instagram (). Katarina contextualised her self-representation with the caption ‘Walking through the passageways of history in #Berlin DE’, already pointing her followers (who appreciated the post with more than 140 likes) towards her emotional experience of commemorating the past. When I ask about the picture in our chat interview, Katarina explains that she is, in fact, critical about the ‘many people posting smiling happy photos there’, which is why she tried ‘to capture the place but still keep a serious note to it’. After I tell her about the ‘Yolocaust’ project and after she views the video documentation of it online, she states that she completely supports the artist in his critique and that she now feels ‘conflicted’ about her own self-representation, since ‘we are in a way shifting attention from the memorial to ourselves’. On the other hand, this seems necessary to her in order to communicate what she feels, ‘in a way to draw attention to the place and what it stands for’.

Haasim is even more explicit regarding this point. While visiting the memorial, he took great care in posing for the picture, directing his friend to the right angle, and later curating it through colour adjustment and filters to have the right aesthetic expression. His posture is strategic, as he explains in our chat interview: ‘I also took a thoughtful concerned look not directly into the objective, to invite the viewer to think with me about what happened […].’ After I point out that some viewers still might consider this picture ‘superficial’ and ‘inappropriate’ because it puts him as the person in the centre, he continues:

I hesitated before posing for the pics; if those were real tombs [the concrete blocks, C.B.], I wouldn’t have accepted. But I also see the memorial as a piece of art. So, I wanted to convey feelings through my pics and mark my presence there. I come from Lebanon, and most of my followers are Lebanese. Many of them hate Jews. So, the purpose of my pic was also provocative. So, I might agree with people who see it as superficial when the pics are randomly taken. But in my case, it meant more for me.

These examples demonstrate that, for many visitors, the function of digital self-representations at the Holocaust Memorial is not limited to the purpose of aesthetic self-representation. They can constitute practices of conveying sadness, anger, compassion, commemoration and more; they can serve to grasp the attention of others or even to explicitly provoke discussion. Digital self-representations are not necessarily playing into emotional indifference. Instead, by literally putting themselves into the picture, visitors use them to engage in cultures of remembrance.

Happy remembrance?

While all the visitors interviewed quoted above created digital self-representations, they still insist that their own representations are different from the ‘smiling happy photos’ taken by countless others. In doing so, they implicitly or explicitly suggest that the portrayal of happiness is the actually ‘inappropriate’ practice in the context of the memorial that articulates an emotional indifference towards the past. On the one hand, this critique of ‘happy pictures’ might be justified considering the fact that many visitors, as my ethnographic study also confirms, simply follow the tourist routines of smiling for pictures at ‘remarkable’ sites without reflecting much about the implications of their smile – and this is also true for the Holocaust Memorial. Even among the visitors smiling for pictures, however, there are many who do not consider their own smile to be an articulation of emotional indifference. On the contrary, they consider their smile to be a different but meaningful practice of remembrance. As Lina, a 28-year-old tourist from Belgium, puts it: ‘I think that even if you smile you can still have respect for the things that the memorial stands for, which happened here. I don’t think a smile is in contrast to respecting it.’ Tara, a young woman from Washington D.C., emphasises the same point as she explains to me what kind of pictures she took:

Um, we smiled, and we kinda just had our hands crossed, like joined behind our backs. I think something like this is powerful, but it’s also really unifying, so I don’t think there is a problem smiling. I think that, you know, the struggle of people’s past has been able to cultivate what we have today. So I don’t wanna say: ‘Why not enjoy the site?’, but: ‘Why not show that you were there and that you were happy with the experience that you had?’

As Tara and Lina explain, a smile can be a form of commemoration as well. This brings me back to the introductory example: Christine’s warm and friendly smile, contextualised by hashtags such as ‘#jewish #history #neverforget #lchaim #tolife #tolove’.

In our chat interview, Christine tells me about her family history, about how her grandfather had to flee from Poland to Germany by foot and how she got interested in the history of WW2 and the Holocaust. Although she is not Jewish, she always wears a necklace with the Hebrew symbol ‘L’Chaim’ (‘to life’) around her neck, which also inspired her choice of hashtags. In our interview she reflects upon her smiling pictures (my translation):

I’ve been thinking about posting the pictures for a long time. … because of the smile; actually, it’s a serious topic behind the memorial. But then I thought to myself, this history belongs to us, we have to accept it. I accepted it and try to do everything differently in my life than was done then. I just don’t have the right words right now![]() [Emoji for ‘Face with Hand Over Mouth’, C.B.]. I am very cosmopolitan, take an interest in other cultures […]. I am very interested in Israel and the Jewish culture and then I just thought, because I am somehow at ‘peace’ with all this, I can smile on my pictures at the memorial.

[Emoji for ‘Face with Hand Over Mouth’, C.B.]. I am very cosmopolitan, take an interest in other cultures […]. I am very interested in Israel and the Jewish culture and then I just thought, because I am somehow at ‘peace’ with all this, I can smile on my pictures at the memorial.

Just as in the cases described above, Christine’s smile is not simply an articulation of happiness that demonstrates her emotional indifference, let alone disrespect, towards the Holocaust. On the contrary, Christine’s smile is enacted as part of her ongoing interest in the history of the Holocaust and, from her point of view, an emotionally meaningful practice of remembrance and commemoration. As such, her ‘happy picture’ fulfils a similar function as the other digital self-representations with a more ‘serious’ tone that I have described above, and it even goes one step further: for Christine, her picture becomes part of a process of figuring out her personal way of commemorating the past. In her case, this is achieved through a smile as an emotional practice that acknowledges the horrors of the Holocaust while still expressing confidence and even happiness about how the world unified against the crimes of the past.

Conclusion

The ethnographic examples in this article demonstrate that digital self-representations at sites of difficult heritage can constitute complex practices of emotional engagement with the past. If memorials to atrocities serve as a reminder of particular pasts that affect us through our knowing and feeling bodies, then digital technologies can become media for relating to the past through one’s own body and making these particular relationships publicly visible.

While many of these practices of digital self-representation are not entirely new and photographic portraits in front of memorials have been a part of tourists’ photographic routines for decades, new digital technologies still enhance the ubiquity, frequency and style (e.g. selfies) of mediated self-representations at such sites. Even more crucially, they allow visitors to digitally share these representations with their friends and the global public. While also the sharing of and talking about such representations is not a genuinely new phenomenon, digital infrastructures and especially social media platforms afford a dynamic renegotiation of self-representation related to the Holocaust. However, the significant transformations of memory practices that we are currently witnessing in relation to digital media are not simply an effect of technological change. They go hand in hand with broader socio-cultural transformations. Not only the technologies of self-representation change, also the cultures of self-representation do.

While the critics of ‘selfie culture’ make a valid point in criticising emotional indifference towards the Holocaust, we need to look more closely at these practices in order to see whether they are, indeed, articulating emotional indifference. As I have shown, many of these practices do the exact opposite. This argument is not supposed to prevent a critique of emotional indifference towards the Holocaust. In fact, considering the current rise of populist truth-making in public debates, this critique seems more crucial than ever. The Holocaust Memorial has already been questioned concerning its legitimacy by right-wing politicians, most prominently by Björn Höcke, who called it the ‘memorial of shame’ (‘Denkmal der Schande’) and asked for a ‘180 degree turn in memory politics’.Footnote7 Careful analytical attention to how difficult heritage is experienced, how visitors feel about it and how the digital transformations of memory cultures shape these emotional relationships is of particular value in the light of such developments.

It might be tempting to see a direct connection between the digital transformations of memory cultures and a supposed growth in emotional indifference towards the past. Indeed, there might be some truth in my interviewee Adam’s observation that many people are ‘filtering their daily interactions through the lens of their phone screen’ and are, thus, ‘removed from true “first-hand” experience’, which results in experiences in which ‘things just don’t have the same gravity’ (see full quote above). At the same time, however, blaming ‘selfie culture’ and equating digital media practices with ‘superficial’ remembrance is much too simplistic, as Adam demonstrates himself through his social media post. Digital devices can become powerful media of personal emotional engagements in their own right.

This argument resonates with broader discussions in the field of museums and heritage regarding the transformations of contemporary cultures of remembrance. Juliane Brauer and Aleida Assmann (Citation2011) suggest considering the process of historical imagination and presencing of the past (‘Vergegenwärtigung’) when looking at the entanglements of media and commemoration in Holocaust remembrance. Brauer and Assmann’s case is different from my own, since they studied video projects conducted by German school students working with video interviews with Holocaust survivors and witnesses. The researchers’ observations about the historical imagination, however, are relevant for my case as well. They argue that practices of presencing the past through media entail far more than subjective emotional immersion into this past. Instead, they are about connecting to the past in order to make this past a meaningful part of one’s own present (Brauer and Assmann Citation2011: 80).

This argument also corresponds with what Thomas Thiemeyer (Citation2018) has suggested regarding current transformations of Holocaust commemoration in both Germany and Israel. Together with Jackie Feldman, Tanja Seider and students from universities in both countries, they explored contemporary practices of remembrance (also touching upon the ‘Yolocaust’ debate and digital media), leading Thiemeyer to observe an ongoing transition towards a ‘performative culture of remembrance’ (‘performative Erinnerungskultur’, 18). The growing performative aspect of Holocaust remembrance, he suggests, is anchored in how visitors individually appropriate the past, how they come to make it their own and meaningful for their present (18).

This observation of a growing tendency towards individual appropriation in Holocaust remembrance does not suggest that memory practices become entirely fragmented. Instead, it points us to the growing importance of personal connections to the past for a generation of young people who are increasingly estranged from the shared historical experience of WW2. My own ethnographic analysis supports these observations, and it highlights the crucial role that digital media can play for visitors in their practices of personally relating to the past through emotional practices and, thus, of making the past part of each visitor’s own present.

Looking at social media, we also see that for many visitors, performing and experiencing their personal relationship to the past is not the end of the story. Instead, they are often shared. The personal experiences of individuals in contemporary digital cultures of remembrance have high socio-cultural value and can contribute to the constitution of and exchange within ‘emotional communities’ (Gregory Citation2014). Consequently, when emotional relationships to the past are shared on platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, this is where an emerging both performative and digital culture of Holocaust remembrance constitutes its particular social impact.

That is to say, if we follow Eli Wiesel in acknowledging that ‘it can happen again’, this does not call for a general condemnation of digital media practices at sites of difficult heritage. On the contrary, as we grow into a society without witnesses of that time and weaker personal connections to it, even digital self-representations – or maybe especially digital self-representations – can play an important role in the making and sharing of personal experiences. To the critics, these practices might seem mundane, shallow and inappropriate articulations of emotional indifference towards the Holocaust – the term ‘selfie culture’ is representing this perspective. For many visitors, however, these practices can become different yet meaningful ways of relating to the past.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my gratitude to all visitors and interviewees involved in this project and to the Foundation Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe for providing the space to conduct interviews; to several student assistants for their work; and to the members of the Centre for Anthropological Research on Museums and Heritage (CARMAH) and its director Sharon Macdonald for their invaluable support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christoph Bareither

Christoph Bareither is Junior Professor of European Ethnology & Media Anthropology at the Institute for European Ethnology and the Centre for Anthropological Research on Museums and Heritage (CARMAH) at the Humboldt University of Berlin. His research is concerned with the transformations of everyday practices and experiences enabled through digital technologies. He is especially interested in the fields of media and digital anthropology, museum and heritage studies, popular culture and game studies, digital methods, ethnographic data analysis and the ethnography of emotions.

Notes

1. https://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/memorials/memorial-to-the-murdered-jews-of-europe/?lang=en. Accessed 1 May 2020.

2. https://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/memorials/memorial-to-the-murdered-jews-of-europe/?lang=en. Accessed 1 May 2020. See section ‘Peter Eisenman about the Memorial’.

3. https://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel-interview-with-holocaust-monument-architect-peter-eisenman-how-long-does-one-feel-guilty-a-355252.html. Accessed 1 May 2020.

4. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38675835. Accessed 1 May 2020.

5. https://www.facebook.com/ajplusenglish/videos/holocaust-selfie-culture-yolocaust/914675568673951/. Accessed 1 May 2020.

6. http://www.historyplace.com/speeches/wiesel.htm. Accessed 1 May 2020.

7. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/parteien-die-hoecke-rede-von-dresden-in-wortlaut-auszuegen-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-170118-99-928143. Translated by the author. Accessed 1 May 2020.

References

- Abu-Lughod, L., and C. Lutz, (eds.) - 1990. Language and the Politics of Emotion. Cambridge, UK, New York, Paris: Cambridge University Press.

- Ahmed, S. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2nd Ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Bareither, C. 2019. Doing Emotion through Digital Media: An Ethnographic Perspective on Media Practices and Emotional Affordances. Ethnologia Europaea 49 (1): 7–23.

- Boellstorff, T., B. Nardi, C. Pearce, and T. L. Taylor. 2012. Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Brauer, J., and A. Assmann. 2011. Bilder, Gefühle, Erwartungen: Über die emotionale Dimension von Gedenkstätten und den Umgang von Jugendlichen mit dem Holocaust. Geschichte und Gesellschaft 37 (1): 72–103.

- Breidenstein, G., S. Hirschauer, H. Kalthoff, and B. Nieswand. 2015. Ethnografie: Die Praxis Der Feldforschung. Second ed. Constance; Munic: UVK.

- Campbell, G., L. Smith, and M. Wetherell. 2017. Nostalgia and Heritage: Potentials, Mobilisations and Effects. International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (7): 609–611.

- Dekel, I. 2013. Mediation at the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dinhopl, A., and U. Gretzel. 2016. Selfie-Taking as Touristic Looking. Annals of Tourism Research 57 (January): 126–139.

- Douglas, K. 2017. Youth, Trauma and Memorialisation: The Selfie as Witnessing. Memory Studies, 1–16.

- Eckel, J., J. Ruchatz, and S. Wirth. 2018. “The Selfie as Image (And) Practice: Approaching Digital Self-Photography.” In Exploring the Selfie: Historical, Theoretical and Analytical Approaches to Digital Self-Photography, edited by J. Eckel, J. Ruchatz, and S. Wirth, 1–23. London, New York, Shanghai: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Emerson, R. M., R. I. Fretz, and L. L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd Ed. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

- Golańska, D. 2015. Affective Spaces, Sensuous Engagements: In Quest of a Synaesthetic Approach to ‘Dark Memorials’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (8): 773–790.

- Gregory, J. 2014. Connecting with the past through Social Media: The ‘Beautiful Buildings and Cool Places Perth Has Lost’ Facebook Group. International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (1): 22–45.

- Habermas, J. 1999. Der Zeigefinger: Die Deutschen und ihr Denkmal. DIE ZEIT. https://www.zeit.de/1999/14/199914.denkmal.2_.xml/komplettansicht(Accessed 1 February 2020).

- Hilmar, T. 2016. Storyboards of Remembrance: Representations of the past in Visitors Photography at Auschwitz. Memory Studies 9 (4): 455–470.

- Hine, C. 2015. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hochschild, A. R. 2003. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. 1998. Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Knudsen, B. T. 2008. Emotional Geography: Authenticity, Embodiment and Cultural Heritage. Ethnologia Europaea 36 (2): 5–15.

- Larsen, J. 2008. Practices and Flows of Digital Photography: An Ethnographic Framework. Mobilities 3 (1): 141–160.

- Larsen, J. 2014. The (Im)mobile Life of Digital Photographs: The Case of Tourist Photography. In Digital Snaps: The New Face of Photography, edited by J. Larsen and M. Sandbye, 25–46. London: Tauris.

- Levi, P. 2017. The Drowned and the Saved. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Macdonald, S. 2009. Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi past in Nuremberg and Beyond. London, New York: Routledge.

- Macdonald, S. 2013. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. London, New York: Routledge.

- Macdonald, S. 2015. Is ‘Difficult Heritage’ Still ‘Difficult’? Museum 67 (1–4): 6–22.

- Pink, S., H. A. Horst, J. Postill, L. Hjorth, T. Lewis, and J. Tacchi. 2016. Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Reckwitz, A. 2017. Practices and Their Affects. In The Nexus of Practices: Connections, Constellations, Practitioners, edited by A. Hui, E. Shove, and T. R. Schatzki, 114–125. London, New York: Routledge.

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. 2008. Picturing Experience: A Tourist-centered Perspective on Commemorative Historical Sites. Tourist Studies 8 (1): 77–103.

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. 2017. Making Polysense of the World: Affect, Memory, Heritage. In Heritage, Affect and Emotion: Politics, Practices and Infrastructures, edited by D. P. Tolia-Kelly, E. Waterton, and S. Watson, 12–29. London, New York: Routledge.

- Scheer, M. 2012. Are Emotions A Kind of Practice (And Is that What Makes Them Have A History)? A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion. History and Theory 51: 193–220.

- Scheer, M. 2016. Emotionspraktiken: Wie man über das Tun an die Gefühle herankommt. In Emotional Turn?! Europäisch ethnologische Zugänge zu Gefühlen & Gefühlswelten: Beiträge der 27. Österreichischen Volkskundetagung in Dornbirn vom 29. Mai - 1. Juni 2013, edited by M. Beitl and I. Schneider, 15–36. Wien: Selbstverlag des Vereins für Volkskunde.

- Smith, L., and G. Campbell. 2015. The Elephant in the Room: Heritage, Affect and Emotion. In A Companion to Heritage Studies, edited by W. Logan, M. N. Craith, and U. Kockel, 443–460. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Smith, L., M. Wetherell, and G. Campbell, (eds.) - 2018. Emotion, Affective Practices, and the past in the Present. Milton: Routledge.

- Strauss, A. L., and J. Corbin. 1994. Grounded Theory Methodology: An Overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 273–285. London, New York: SAGE.

- Thiemeyer, T. 2018. Erinnerungspraxis Und Erinnerungskultur. In Erinnerungspraxis Zwischen Gestern Und Morgen: Wie Wir Uns Heute an NS-Zeit Und Shoah Erinnern: Ein Deutsch-Israelisches Studienprojekt, edited by T. Thiemeyer, J. Feldman, and T. Seider, 7–20. Tübingen: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde.

- Tolia-Kelly, D. P., E. Waterton, and S. Watson, (eds.) - 2017. Heritage, Affect and Emotion: Politics, Practices and Infrastructures. London, New York: Routledge.

- Tschofen, B. 2016. Eingeatmete Geschichtsträchtigkeit’: Konzepte Des Erlebens in Der Geschichtskultur. In Doing History: Performative Praktiken in Der Geschichtskultur, edited by S. Willner, G. Koch, and S. Samida, 137–150. Münster, New York: Waxmann.

- Urry, J., and J. Larsen. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. 3rd Ed. London: Sage.

- Waterton, E., and S. Watson. 2015. A War Long Forgotten: Feeling the past in an English Country Village. Angelaki 20 (3): 89–103.

- Wetherell, M. 2013. Feeling Rules, Atmospheres and Affective Practice: Some Reflections on the Analysis of Emotional Episodes. In Privilege, Agency and Affect, edited by C. Maxwell and P. Aggleton, 221–239. Vol. 35. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Wetherell, M., L. Smith, and G. Campbell. 2018. Introduction: Affective Heritage Practices. In Emotion, Affective Practices, and the past in the Present, edited by L. Smith, M. Wetherell, and G. Campbell, 1–21. Milton: Routledge.

- Witcomb, A. 2007. Beyond Nostalgia: The Role of Affect in Generating Historical Understanding at Heritage Sites. In Museum Revolutions: Museums and Change, edited by E. R. Sheila, S. M. Watson, and S. J. Knell, 263–275. London: Routledge.

- Witcomb, A. 2012. On Memory, Affect and Atonement: The Long Tan Memorial Cross(es). Historic Environment 24 (3): 35–42.

- Witcomb, A. 2013. Using Immersive and Interactive Approaches to Interpreting Traumatic Experiences for Tourists: Potentials and Limitations. In Heritage and Tourism: Place, Encounter, Engagement, edited by R. Staiff, 152–170. London: Routledge.