ABSTRACT

Historic urban centres are struggling to survive in rapidly emerging global environments. While many significant historic districts were demolished to pave the way for new environments, others just disappeared from neglect and destruction. Tensions over land use and the continued consumption of historical areas such as trade and tourism place considerable pressures on their distinctive values that make them attractive places in which to live, work and visit. Such pressures have brought into focus the extent to which cultural sustainability can participate in revitalising a historic city while sustaining its place identity in a global world. In the age of globalisation, the mismatch between cultural (history, memory) and economic forces (tourism, trade) in a historic city can lead to the erosion of place identity. Within this context, this paper explores the following question; ‘in what way can cultural and economic forces be integrated with a historical city or district to accommodate change while sustaining its place identity’? The case study approach is used as the primary method of investigation, and old Doha in Qatar is the main setting of research.

Introduction

Within the emergence of globalisation trends, through social media and economic flows, the world has become like a small village. These impacts are very significant worldwide and in the Gulf, which resulted in the emergence of global environments in cities like Dubai, Manama and Doha. These global areas and mainly waterfronts are invaded with monotonous concrete, steel and glass towers, which do not have any link with the local contexts. Within this dilemma of creating similar environments, most cities have felt the need to search for a place identity that makes their cities distinctive and different from others in the region. Place identity is taking increasing attention and has become an important issue to tackle. In this context, resilient historic cities and urban centres are being viewed as catalysts and drivers of strengthening the uniqueness and distinctiveness of their cities.

In the Arab world, it was just recently that a real concern started to be given to the resilient historic cities and centres. For example, in Lebanon, while the Solidere- Project in Beirut was seen as a model for urban regeneration, however, its approach was acutely disapproved for destroying ‘Beirut’s old core and deleting significant memories of its past. In fact, to make way for projects, which would bring money, the rise in the real ‘estate’s prices resulted in gentrifying the local inhabitants outside Beirut city centre (Scharfenort Citation2013, 2). This is an aspect of radical losses that sacrificed cultural aspects related to identity and memory in favour of projects that generate money only. A reasonable change could have allowed the historic Beirut to evolve without being divorced from its past roots.

In the medina of Tunis, Tunisia, after the completion of the rehabilitation of the medina, rent increased dramatically. As a result, the low-income families who used to live there could not cope anymore with this rise and were forced to quit their homes to go to the periphery. Here again, the economic forces took over the culture- led forces by forcing the local inhabitants to abandon their homes. In old Damascus, in Syria Salamandra (Citation2004) evoked that a large number of courtyard houses are being transformed into famous restaurants to welcome local and global visitors at the expense of the local community needs and aspirations. This shift has changed the spirit of the Arab house Beit Al Arabi from being residential to becoming a commercial. Nevertheless, this kind of change is less harmful than complete loss and cultural amnesia.

In this situation, one might ask the following question, to what extent change can be allowed in historic cities and urban centres? It is believed that the more cultural forces are neglected in favour of the economic ones, the more change is likely to be dramatic, which may lead in many cases to complete losses and amnesia. Historic cities are permanently shifting, and their urban centres grow at a rapid pace and are often under threat of massive redevelopment projects. Therefore, within the emerging of globalisation, is there a danger that towns and cities are becoming similarly homogenised? While most cities have their modernist interventions, with retail and commercial boxes in anonymous suburbs on edge, there has been a growing recognition of the value of a city place identity.

According to (Academy of Urbanism Citation2011, 68), ‘Identity can be the characteristics of a place that makes it memorable, or even forgettable, as well as the names or symbols that turn identity into a brand’. The latter, in turn, signifies what the city wishes others to recognise it stands for. The name of Venice is universally recognised as being associated with the past, merged with culture, relaxation and pleasure. It is by trying to brand their cultural heritage that Gulf cities such as Dubai, Kuwait, Jeddah and Doha are competing to give their cities uniqueness and distinctiveness based on their past.

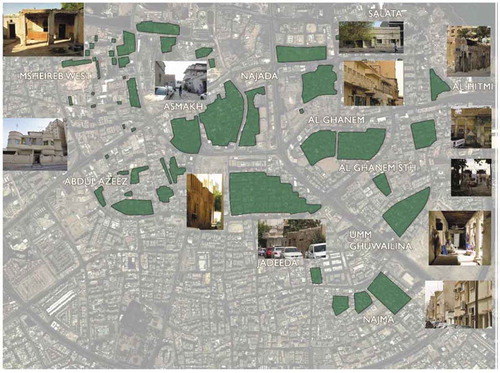

In the Gulf and during the late 1960s and 1970s when most of the six countries gained their independence, they launched many redevelopment projects to delete all signs of poverty and backwardness suffered from the Pre-oil era (). Historic areas were the first victims of this rapid urbanisation; entire districts were swept away overnight to provide land for modern redevelopment (Al-Nakib Citation2016). Today, the few surviving historic centres face significant problems, such as the departure of the original families from their old quarters, to be later replaced by low-income migrants seeking better living opportunities in the city. Eventually, these historic districts have become a refuge for thousands of low-income migrants and single workers. Due to their advanced decay, these historic areas have deteriorated quickly to become slums and ruins in the heart of the city. This critical situation of the historic district is more preferred to a massive tabula-raza of the area which does not leave any traces of the past (Boussaa Citation2014b, Citation2014c).

In fear of losing any traces of the past, in Qatar, several studies dealt with the revival of traditional Qatari architecture and its relevance to the present and future. Al-Kholaifi (Citation2006) published a comprehensive book on traditional architecture in Qatar; he examined the different types of traditional buildings which need to be conserved. Three years later, Jaidah, a famous Qatari architect and Bourennane (Citation2009) carried out in-depth research on traditional architecture in Qatar; during the period 1800–1950. Old Doha was also discussed in several recent studies; (Nagy Citation2000; Lockerbie, Citation2010; Scharfenort Citation2013; Boussaa Citation2003, Citation2014a, Citation2018; Hadjri and Boussaa Citation2007).

Figure 1. A mismatch between the cultural and economic forces resulted in a partial demolition of the significant Al Asmakh house in 2013

Place identity is the way towards building and modifying significance, in a space-time continuum, based on cultural forces as framed and transformed by the progression of economic forces. The need to adapt to time in the period of globalisation, requests commitment with the rational economic forces towards protecting the cultural attributes related to history, memory, tradition and identity of cities. These two forces shape the cultural landscape of the place; therefore, how can a balance between economic and cultural forces maintain moderate versus drastic changes in resilient and fragile historic environments. In other words, place identity can be eroded if a mismatch between the cultural and economic forces occurs (Zetter and Butina Citation2006, 52).

Purpose of the study

With rapid urbanisation, questions related to historic districts are usually raised. What should be done, what should be the new approaches towards them? What strategies should be adopted? What kind of change is needed? In an attempt to respond these queries, UNESCO states, ‘In the wake of intense globalisation and increasing demand for modernisation, the local identity and visual integrity of cities, shaped by their distinctive culture and historic development, are directly impacted. Rapid uncontrolled urbanisation has led to the deterioration and destruction of urban heritage, threatening the identity and local culture of communities and the sense of place in cities’ (UNESCO Citation2016), which often leads to cultural amnesia.

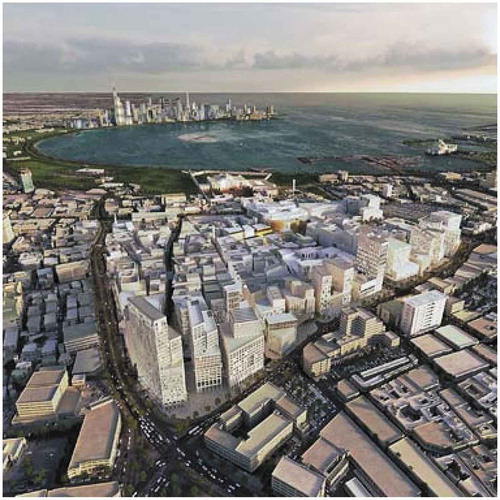

A balanced approach between economic and cultural forces can provide avenues to improve the historic built environment, while not threatening its place identity. For the change prompted by the travel industry, trade and real estate development to be suitable and economical, both cultural and economic forces need to be kept in view, and not hived off into different areas of inquiry. Inside this understanding of place identity, the mismatch between the cultural and economic forces will be explored in the context of old Doha, Qatar (). In addition, this paper investigates how can cultural and economic attributes be incorporated to accommodate moderate versus radical, and slow versus rapid changes while sustaining place identity?

Figure 2. Pressures of financial considerations leading to real estate high rise development encircling the low rise houses in Old Doha, Qatar

The research methodology for this paper has been designed and is based principally on two case studies; Souk Waqif and Msheireb. A case study approach has been chosen as the primary method for investigation and analysis because it provides a platform to understand how these two districts tackled their problems of regeneration and place identity. These two significant cases offer opportunities for comparison and contrast. The empirical investigation is based on several site visits and fieldwork during the last five years. Also, extensive interviews and informal discussions were held with the local heritage players, the different heritage associations and the broader community.

Theoretical background

Place identity is the meaning each individual gives to that place or city. It is an integration of the built heritage, local culture and geographical context, overlaid with perceived remembrances. Place identity has been described as both a sense of purpose and a strong sense of belonging. ‘City identity is a combination of the aspirations and experiences of the citizens and those who visit. The sense of place and identity is reflected in an understanding of both the wider city region and specific physical places. For each city to find its authentic and distinctive identity in a ‘placeless world’, where the same brands occur on every high street, is the ‘challenge’ (The Academy of Urbanism Citation2011, 72).

The role of local urban heritage in rebuilding or reinforcing a ‘city’s place identity cannot be overstressed as expressed in the following statement: ‘Culturally, vibrant cities build stimulating environments, acting as incubators for creativity and appealing to diverse groups of people. Conservation of urban heritage, culture and creativity in cities can help maintain and highlight their unique character while increasing their international visibility and placing them within a global continuum. Culture-Led regeneration strategies that reuse heritage buildings and engage with local citizens, for example, can reinforce the local culture and a community’s sense of pride and local ‘identity’ (UNESCO Citation2016, 6).

The importance of cultural forces in a city such as place identity is a matter that is taking increasing momentum in recent years. Cultural heritage faces distortion, campaigns aimed at playing down its importance and its significant role in rebuilding a ‘city’s place identity. Relph (Citation1976, 61) claims that identity of a place consists of ‘three inter-related components, each irreducible to the other – physical features or appearance, observable activities and function and meanings or symbols’. Physical features are the historic districts and monuments while the observable activities are the everyday use and the meanings related to identity and memory, which form the cultural forces.

Control of cultural forces by rational forces such as tourism is frequently aggravated by the commodification procedure whereby conventions, customs, convictions and ‘lifestyles’ (cultural forces) are often packaged, imaged and changed, into saleable products for tourists (Cohen Citation1987). McKean (Citation1993) elaborates that commodification, in itself, need not create conflict if it carries the participation of the local community and if it can receive the rewards of commercialisation. This view is also shared by McDonald and Thomas (Citation1997). They called attention so that the presentation of cultural artefacts can be identity-affirming and liberating for cultures seeking to exhibit their traditions, values and history. The critical issue in this procedure of commodification, as Robinson (Citation2001) argues, is that local inhabitants should have the right to decide for themselves what parts of their cultural heritage and in what way they should be reused.

In discussing issues related to character, in his book ‘Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization’, Appadurai argues that worldwide social streams are an impact of globalisation, people and networks. He states that anthropologists must not depend on obsolete ideas of character, yet should instead represent how individuals assemble personalities in a globalised world (Appadurai Citation1996). According to Connerton, the locus for memory lies in place names, the house and the road; when these are obliterated, or renamed, a piece of history vanishes. Moreover, he makes his differences well; comparing journey, as giving a praiseworthy sense of place named and set apart, with powers of advancement that offer ascent to its unmistakable cultural amnesia (Connerton Citation2009).

One aspect of cultural amnesia ‘ends up in rivalry with high rises whose heights connote observers to the lords of business. In spite of the fact that not his anxiety, one can perceive how secularisation is a lacking term that hides the organising impacts of advancement, where the house of God loses its restraining infrastructure, its solitary magnificence, to increasingly insatiable ‘contenders’ (Connerton Citation2009, 18). This phenomenon is widely found in the global environments of the Gulf, where the minarets of mosques are drawn in a sea of high-rise towers. This is also an outcome of radical and rapid changes that resulted due to the failure of ensuring a balance between the cultural and economic forces, thus leading to cultural amnesia.

Holtorf. (Citation2018) claims that cultural heritage needs to be conserved as a significant catalyst for promoting cultural resilience. He argues that cultural resilience, risk preparedness, post-disaster recovery and mutual understanding will be reinforced by an expanded capacity to acknowledge loss and change. In this context, Holtorf. (Citation2018) defines ‘cultural resilience as the capability of a cultural system (consisting of cultural processes in relevant communities) to absorb adversity, deal with change and continue to develop. Cultural resilience thus implies both continuity and change: disturbances that can be absorbed are not an enemy to be avoided but a partner in the dance of cultural sustainability’.

Cultural heritage, whether tangible or intangible, is sustainable to the extent that it has the capability to adapt to change through creative transformation and continues to develop (Boccardi Citation2015; Lane Citation2015). When this is observed, any specific heritage has been lost or is currently vulnerable, and at risk, one should ask how that heritage has been or might be transformed absorbing the apparent disturbances (Holtorf Citation2015; DeSilvey Citation2017). Just like entire societies, a cultural heritage that is not adaptable and receptive for transformation is not sufficiently resilient and therefore not sustainable. Instead, loss of specific manifestations of heritage is an inevitable outcome of a living culture continuing to exist now and in a future that is going to be subjected to changes and transformations compared with the present. Though this is evident but can there be a moderate change, which allows the new to exist without excluding the old? This cannot happen unless a balance between the cultural and economic attributes is ensured and sustained.

While it is agreed that cultural heritage should adapt to current and future changes, however, one disagrees with having radical changes, which delete and erase cultural references of the past. One does not share the view that this can be one aspect of cultural sustainability or resilience, but only an aspect of cultural amnesia, as it deletes heritage resources for the sake of money. In fieldwork, as in history, the only thing that may be genuinely permanent is the need to be resilient and always ready for change but not for negation and decimation of any cultural attributes, which form the backbone of place identity.

This paper supports Lynch view that an ‘individual’s sense of well-being and effective action depends on stable references from the past, which provide a sense of continuity and reassurance in an uncertain future. Therefore, here one will refer again to what Hatford named as loss. It is believed that with the loss there will not be any presence of references from the past, therefore no uniqueness or distinctiveness of the contemporary city, which means no place identity in a global world.

Historic cities reflect the way people lived and accommodated to a specific place, making it unique to each city. Therefore, there is a vital need to maintain this adaptation and this way of living in an active and engaging way to the public. Adaptive reuse of historic cities and districts includes not only conserving substance and buildings as is but also requires sustaining all the values and traditions that people are attached to. In other words, ‘Historic cities, as the ‘collages of ‘time’ are the very references that connect past, present, and ‘future’ (Lynch Citation1972, 235). To recap, the above issues related to cultural sustainability and levels of change in historic cities will be explored in the context of old Doha, Qatar.

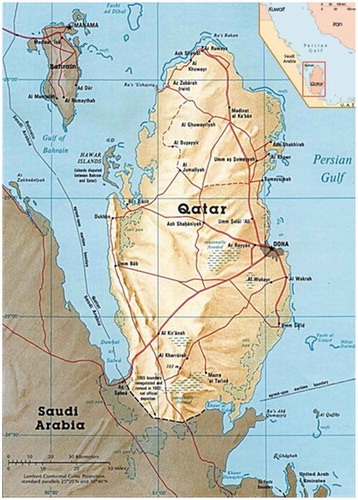

The context; Doha is a global world

Doha, the city-state of Qatar, has over 2 million inhabitants out of the nation’s population of 2,876,776 persons in June 2020 (www.mdps.gov.qa). It is also the main headquarters for the ruler and ministries and an economic centre of the country (). Before 1950, Doha was a small fishing and pearling village stretching 5kms along the sea. The appearance of Japanese cultured pearls in the 1930s had a severe impact on the traditional Qatari economy that was based mainly on pearling, trade and fishing. This resulted in many pearling divers losing their jobs who had to migrate outside Qatar to look for other living opportunities and then Doha suffered from many years of hunger. After the discovery of oil in 1939 and the beginning of its exportation in 1949, the first revenues from oil started to pour in increasingly. Only 15 years after 1950, Qatar witnessed the end of years of Hunger, and a visitor to Doha would see the changes that started to happen:

A sprawling city of concrete buildings, traffic lights, ring roads and soda stalls; air conditioning is the rule; the waterfront has been reclaimed, and much of the fifth removed; a large merchant class has grown up, and social life has become conventional and big ‘city’ (Montigny-Kozlowska Citation1982, 482).

Figure 3. Map of Qatar, showing the location of Doha on the eastern coast (https://www.google.com.qa)

From a place of poverty before the discovery of oil in the 1940s to an over grown fishing village in 1955 to a large city in 1965 and fast-growing capital in the 1970s. Doha is now a capital city of one of the most economically successful countries in the world (Fromherz Citation2012, 3). Qatar gained independence in 1971; one year later, the planning company of Llewellyn- Davies developed the first master plan for Doha. Due to the absence of any regeneration strategies for cultural heritage at that time, several historic districts were demolished such as old Slata and significant parts of old Al Ghanim (). The original inhabitants who lost their houses due to the bulldozer planning approach were forced to move out to new residential areas at the periphery, such as Al Rayyan, Madinat Khalifa and Al Gharafa (Fadila Citation1991, 86).

During that time, the authorities were too keen to modernise the city while removing the built heritage structures that stood in their way. To keep few ties with the past, a number of scattered monuments have been restored. The Old Palace was the first building to be rehabilitated just after independence during 1972–1975 to host the first national museum of Qatar. It was not until the year 2000 that comprehensive urban rehabilitation projects started to emerge. Souk Waqif rehabilitation project was the first project to be implemented during 2004–2010. Msheireb Downtown project was the second large scheme in a site 20 times the size of Souk Waqif. This project began in 2008 and is still ongoing; its heritage quarter was completed and was opened to the public in 2016.

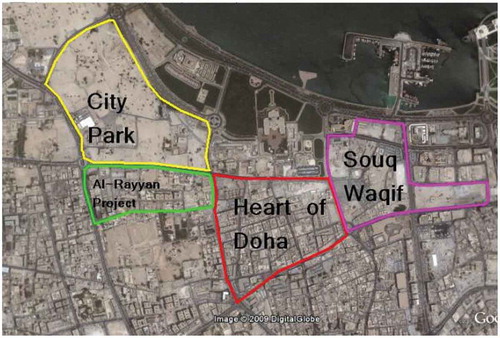

Figure 4. Pressures of economic forces resulting in the erosion of many historic districts, leaving only a few patches in old Doha (Courtesy of Qatar museums)

In their article There is no heritage in Qatar: Orientalism, colonialism and other problematic histories Exell and Rico (Citation2013) disapproved the claims of several scholars from the West who believe that ‘there is no heritage in ‘Qatar’ by arguing that despite the small size of Qatar, there is a potential cultural heritage that needs to be cared off. It is unfair to equate Doha to Venice, London, Paris or Granada in terms of history and heritage. It is also biased to compare Doha, to the ancient cities of Damascus, Baghdad and Cairo. Though, Qatar has its cultural heritage which forms its primary cultural identity. ‘Qatar’s cultural heritage is inscribed within the Gulf region scope, UAE, Bahrain and Kuwait.

In this context, Exell and Rico study ‘forms an introductory element of a study of the construction of contemporary Qatari heritage and identity, problematising state-level heritage construction and seeking to locate and identify locally constructed and branded Qatari heritage conceptions and practices’ (Exell and Rico Citation2013, 671). It is crucial to uncover several cultural heritage resources which still survive and thus form a strong basis for place identity. These elements range from historic mosques, forts and palaces to old districts. For instance, Al Zubarah archaeological site, including its resilient fort is the first World Heritage Site in Qatar since 2013 (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1402).

So far, the need for a balance between the cultural and economic forces as a way to allow change while identity is sustained through history has been highlighted. The question to discuss now in the context of Doha: why there is a need to maintain a balance between cultural and economic forces. This paper believes that this balance will enable a reasonable versus a radical change as a way to ensure cultural sustainability. To discuss this question in further details, two major regeneration projects will be examined; Souk Waqif and Msheireb in old Doha ().

Reinforcing place identity in Souk Waqif

Old Doha lies in an area of 250 hectares; it is a combination of traditional districts going back to the period (1850–1950). The surviving historic districts, such as Souk Waqif, Msheireb and Al Asmakh form important chapters in the ‘city’s history. All these neighbourhoods contain compact courtyard houses with one and two stories built with coral stones extracted from the sea and roofed with Danchal (wooden beams) imported from Zanzibar and Bamboo from India.

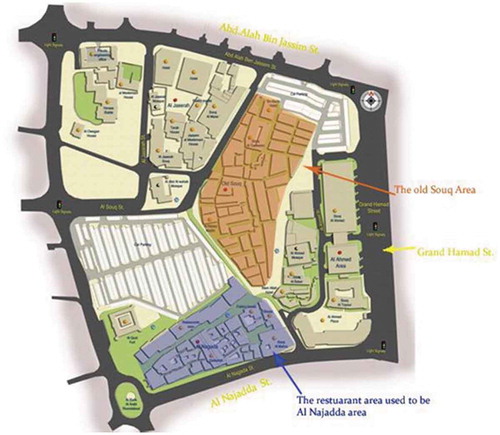

Souk Waqif is a famous Souk not only in Doha, but also in the entire Gulf. The history of the place serves as the true value of the Souk in the hearts of the local inhabitants. It is a very well-known souk for selling traditional garments, spices, handicrafts and souvenirs. It also features dozens of restaurants serving cuisines from all over the world, as well as a home for various five ‘stars’ boutique hotels.

After long years of dilapidation and neglect, during the beginning of the 21st century, Souk Waqif fell into advanced disrepair and decay. Due to a lack of an initial concern about the souk, unsympathetic buildings of dense shops frontage, crowded entrances and clash of functions intruded the souk. All these physical changes resulted in a hybrid environment of modern and old structures that dramatically transformed the distinctive original image and character of the souk. Due to increasing dereliction, in 2004 the former Emir of Qatar Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa (the present ‘Emir’s father) launched an urgent rescue of the souk before it would disappear ().

Since most of the shops were privately owned, the government had to purchase

them from their owners. According to Mohamed Ali Abdulla, the Project Manager of the rehabilitation project, after a detailed survey, he found out that two-thirds of the buildings were still in their original state (Boussaa Citation2010). This is very important as these structures can play a significant role in reconstructing the damaged place identity of the souk through enabling a balance between the economic and cultural forces (). To achieve this, the rehabilitation project aimed to realise the following objectives:

‘Reconstruct the lost image of historic Doha through the rehabilitation of its authentic Souk Waqif;

Protect the area of the souk and its surrounding from real estate development;

Create an open-air public area pedestrianised;

Establish a vibrant souk with its original layout and ‘goods’ (Radoine Citation2010, 3).

Figure 7. Views are showing the Souk state before the beginning of restoration in 2004 (Courtesy the private engineering office)

The first and third objectives attempted to fulfil the cultural needs by reinforcing the place identity of the Souk. Protecting the area from massive changes due to real estate development was challenging to implement as the economic forces made more pressures to launch high-rise tower blocks around the souk. To retrieve the original character of the souk, several modern buildings were demolished and replaced and by new structures inspired by the local Qatari architecture. This was implemented to create a physical continuity with the 1/3 remaining of original historic buildings. To maintain the authenticity of the souk during the restoration process, traditional building materials were recycled and reused, such as coral stones for walls, Danjal and Bamboo in the roofs and teak wood for doors and windows. New features and services to upgrade and enhance the living environment were also added, like better lighting and drainage systems.

Souk Waqif is both a traditional open-air public space and most importantly a car-free area for tourists, merchants and residents alike. In response to the economic forces, the souk was completely restored, and then an adaptive reuse programme was implemented to revitalise the souk. Restaurants and cafes were taking place along Al Khrais Street on the southern part of the souk, with a wide variety of indoor and outdoor siting, public and semi-public spaces; it is called Al Najada area. The central area between Souk ―Al Etem and the restaurants’ area is characterised by the handicrafts, souvenirs, shops, Souk Waqif Art Centre and the traditional majlis settings ().

Figure 9. Msheireb project respecting the existing traditional urban pattern (Courtesy Msheireb Properties)

While new activities have been injected in the souk, the cultural forces were not neglected, as some of the original functions have been preserved to a certain extent. For instance, there are still shops selling traditional clothes, dates and spices. In addition, a traditional café ‘‘‘Gudwe’ always attracts elderly Qataris to chat and gather. To remember and live moments of the past, during each evening, a large baraha (plaza) hosts many elderly women who sit to prepare traditional food for locals and visitors to taste and try.

Since the souk has become a significant attraction in Doha, recently, two substantial underground parking, which accommodates around 3,000 cars, have been established to reduce the pressure caused by the lack of parking slots, especially during weekends and holidays. While the underground parking created a significant relief for the daily users of the souk, its roof offered a unique Baraha (plaza) facing the corniche, used for public gatherings and recreation. This is an exciting integration between the economic and cultural forces. The parking issue was solved while the baraha offers an opportunity for social interaction and integration between the users of the souk; a unique meeting point between the local and global. Adding to trade and recreational facilities, Souk Waqif has become home for cultural activities through its art galleries and workshops, which host several exhibitions and local concerts during special festivals.

On the one hand, an integration between the cultural and economic attributes has contributed greatly in injecting a new life to the souk. While the case of Souk Waqif showed a successful moderate change that sustained most of the existing heritage structures, thus strengthening a sense of place and the feeling of belonging to the souk. On the other hand, economic objectives were not dismissed as most of the resilient historic buildings have been reused as restaurants, shops, hotels and cafes. However, more efforts could have been added to reuse several upper floor shops for accommodation to increase the vibrancy of the souk to reach 24 hours a day. Souk Waqif has become a meeting point between the local and global tourists in a bustling historic environment.

Msheireb; a new identity inspired from the past

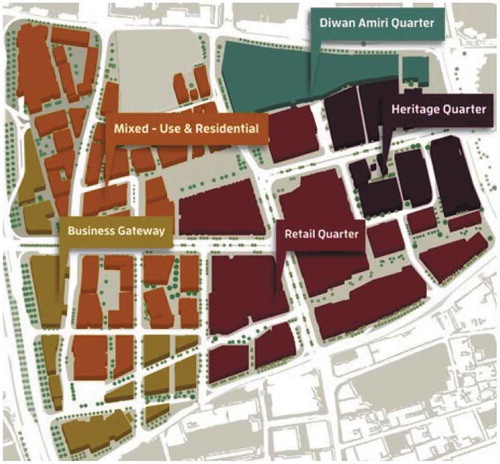

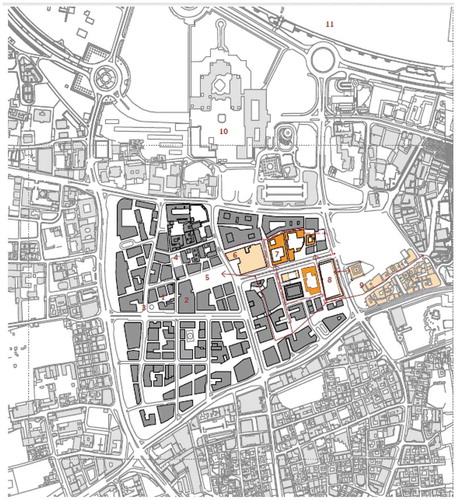

Msheireb Downtown Doha is an innovative mixed-use project for sustainable urban regeneration. Msheireb project is one of the first contemporary master plans developed for a historic district in the Gulf (). Previously titled Doha land the development has a progressive outlook yet draws its inspiration from the local history, looking to re-create a lifestyle deeply rooted in the traditional Qatari culture. While it is being developed as a state-of-the-art and upscale project, Msheireb aims to be a fully integrated community providing a mix of residential, commercial, heritage and retail activities.

Figure 11. Msheireb project respecting the existing traditional urban pattern (Courtesy Msheireb Properties)

Msheireb project dives deep into the local history and morphological imprints to find the social meanings and values embedded in the traditional fabric. After decades of car-driven urban expansion, the project backs the trend by putting people first and cars second via introducing a completely new public realm network. Msheireb project demonstrates that there is an intense desire for outdoor activities and an alternative to the air-conditioned and energy-hungry entertainment boxes ubiquitous in the region (Scharfenort Citation2013).

In 2008, the Msheireb project headed by her Highness Shaikha Moza (the present ‘Emir’s mother) and patronised by Qatar Foundation launched a large-scale project over an area of (31 hectares). The project intended to regenerate this historic district to establish a contemporary fareej (neighbourhood) inspired by tradition. In short, the following are the main objectives of the master plan: (Law and Underwood Citation2012, 133).

‘To promote a sustainable way of living within a compact city framework that reduces automobile usage, increases density and improves public transport and mixed-use;

To renew a piece of city infrastructure to reduce its reliance on fossil fuel;

To promote better integrated social communities at the heart of the city where locals and expatriate workers are walkable neighbourhoods, public spaces and amenities;

To modernise a piece of ‘Qatar’s capital city in ways that will resonate with local history and ‘cultures’.

The master plan proposes a safe, well-appointed, well served, a thriving residential/commercial centre comprising facilities and amenities within a walkable distance. In Msheireb, streets and neighbourhoods are designed as collective ensembles rather than being isolated each one in its plot (). The compact layout offers many advantages in terms of creating shaded streets that encourage inhabitants to walk and interact. The scale of an intervention lies at mid-way between the high rise towers of the West bay and the low rise houses of Al Asmakh and Souk Waqif, with structures reaching 10–12 stories on Msheireb and Kahrabaa streets.

The plan integrates a variety of activities with areas of a specific character. Eight distinctive areas were defined, each one with its character but form an integral part of a unified identity. Some areas are mainly residential, while others are a mixture of retail and commercial space. The new fareej incorporates a unique urban diversity with well spacious city houses within easy access to services and amenities. A vital characteristic of the project is the vibrant public barahas (plazas) and courtyards, which are rarely found in Doha.

Adjacent to Souk Waqif, Msheireb project aims to create a new social and civic hub in the city centre – a place where it is enjoyable to live, work, shop, visit, and spend time with family and friends. Msheireb aims to create a living district featuring office space, retail, leisure facilities, townhouses, upscale apartments, hotels, museums, civic services, and exciting cultural and entertainment venues. Cars are strategically placed underground in several basement levels, ensuring a complete pedestrian-friendly atmosphere.

(mdd.msheireb.com/exploreproject/projectoverview.aspx#sthash.xJpWsA2l.dpuf).

The approach adopted was a complete tabula-raza of the original historic district. However, to avoid total cultural amnesia, only four houses have been conserved and adaptively reused as museums. The diversity of heritage and new structures has emerged to make the experience memorable. As previously mentioned, ‘Shaikha Moza said ‘Our architecture is simple and elegant, it’s not ornamentation, pattern, colour; it’s not Morocco or the Alhambra. For us, the most important thing was looking at history. In 1947, it was just a fishing village, then the 1950s oil and gas money hit and there were big urbanisation and eventually suburbanisation issues’ (Law and Underwood Citation2012).

The approach of Msheireb to create a distinctive identity and character is not based on copying the past; instead, it draws from a thorough study of the local traditional architecture. This project is different from Souk Waqif, which has been more successful in rescuing at least 1/3 of the original buildings in the souk. However, in Msheireb, the scale of demolition was overwhelming, and only four historic houses were rescued. Therefore, this created an urgent need to create a new urban identity inspired by memories of the past ().

While the physical environment succeeded in a way to construct a new identity inspired from the past, however, the approach fails to reflect the original inhabitants’ aspirations and needs. Neither the former nor the latter residents were consulted about how the future of Msheireb would be. Therefore, a lot of people, architects and urban planners expressed disagreements about the outcomes of the project. This cultural amnesia could have been avoided if Msheireb Properties involved at least the original owners and experts during the project’s development.

Although the design of the project gives the impression of a well-planned venture, nevertheless Msheireb lacks a harmonious integration with its surrounding areas of Souk Waqif, Al Najada and Al Asmakh. The buildings adjacent to Souk Waqif and Al Asmakh historic areas are massive and tall with 10–12 stories. These towers built on the edge to respond to the economic pressures obstruct direct views towards the low-rise buildings of the neighbouring historic districts. This is an example of what happens when the financial considerations via the emergence of high-rise towers for rent, override the sensitive and cultural needs of the heritage quarter. While Msheireb initiated an innovative approach to create a new urban identity inspired from the past, the experience would have been more successful through more involvement of the local community, and with more sympathy and respect to the surrounding historic areas.

The existing conditions of Msheireb area before 2010 showed deterioration of existing architecture, the area was also abandoned by locals and was occupied by low-income workers. The redevelopment project took the initiative to regenerate the area with heritage and cultural sustainability as its theme. However, it drove away from the low- income occupants and made way to luxury housing inspired by traditions, targeting investors from Arab Gulf states and expatriates. One of the main criticisms for the project is that the old downtown has lost its former charm and soul while the city is now divided (Scharfenort Citation2013).

The popular Msheireb project in Doha has been both praised and criticised for the implications it had on the pre-existing Msheireb area and the future consequences it may potentially have. There are questions about the future of the project and if it will be a mixed-use project. Will a project that started by driving away the migrant workers be able to qualify a mixed-use title, or will it be only meant for the upper economic classes. Any prosperous society calls for mixing of social classes, and future development schemes need to consider redevelopment and avoid gentrification, in other words sustaining a balance between the cultural and economic forces.

Towards a sustainable balance between cultural and economic forces

From the review of the two regeneration projects in Souk Waqif and Msheireb, it can be concluded that moderate versus radical change as experienced in Souk Waqif can allow change while it reinforces cultural sustainability. However, in Msheireb, where change was more massive through demolishing about 90% of the original old houses, thus a loss of the original identity. This issue has led Msheireb Properties to create an alternative identity inspired from the past. It can be said that a more balanced approach between cultural and economic forces has been experienced in Souk Waqif more than in Msheireb. In the future, a moderate versus a massive approach should be applied in other sensitive historical centres and districts, as a way to ensure cultural sustainability and avoid cultural amnesia.

An integrated approach between the cultural and economic forces can ensure that place identity is sustained by managing change and not stifling it. Appropriate practice should reflect the local context, and real-life settings are never global and cannot come into being without the local cultural and economic forces. Based on the cases of Tunis, Damascus, Beirut and Doha, one way in which the historic environment looks at cultural sustainability debate is by putting people, their needs and understanding, as a priority over the physical aspects of cultural heritage. What survives from the historic cities is only significant if it is valued and reused first for the benefit of the local community and then for the global tourists and visitors.

Following the cases of Souk Waqif and Msheireb, it appears that there are more potentialities in relying on historic districts rather than individual landmarks when striving to reinforce an existing place identity as in Souk Waqif or create a new one as in Msheireb. The continued debate on image-making and symbolism in cities are generally derived from the need to search for a local place identity in the emerging global world. Therefore, old districts should form the driving force to direct and control future urban development of a city, rather than relying on single disparate monuments or iconic landmarks.

To avoid cultural amnesia in historic cities, the local inhabitants need to be involved in deciding about the future of their environments, which means that a bottom-up versus a top-down approach needs to be applied. Change in historic areas is too serious a business to leave to the judgement of the stakeholders and officials only. There must be a participatory approach that encourages people to care about their past, buildings, activities, symbols and meanings, which all should participate in retrieving or reconstructing their ‘city’s place identity.

In a historic site, economic-led actions should work to support and strengthen cultural traditions, religious beliefs, local products, food, arts, crafts, and not to eliminate them. Both these forces, economic and cultural if considered equally, can contribute to sustaining a ‘city’s place identity within the emerging global world. If these sensitive aspects are disregarded, the conserved historical cities will become empty containers, or open-air museums thus will ultimately fail to ensure their resilience and sustainability.

Most of the surviving historical centres are located in the heart of cities, which creates continuous conflicts between the need to conserve and the need to redevelop. Since the price of land in the centre rises dramatically, this encourages the owners to demolish their old houses and replace them with high-rise multi-use towers for rent and trade. In addition, the need to get high returns from heritage through tourism and real estate development can be another significant threat to historic areas. Therefore, to sustain place identity of cities, a balance should be maintained between the cultural and the economic forces.

Sustaining a place identity through history is a way to extend and promote the cultural heritage of a city; for saving places with special character and for keeping a city alive. Besides, giving a city its roots is offering the local people their roots as well. In a time of rapid change, links with the past enable people to move forward while feeling proud of their history. In other words, a moderate change based on a balance between cultural and economic forces can be the driver for sustaining a historic city’s place identity while allowing it to be resilient and sustainable in an emerging global world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Djamel Boussaa

With a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Algiers in 1984, Djamel Boussaa obtained his Master of Philosophy in Architecture from the University of York, the UK in September 1987. He taught as an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Architecture, University of Blida, in Algeria for eight years. He joined UAE University in September 1996 and worked for ten years before moving to the University of Bahrain for three years. He completed his PhD in Urban Conservation from the University of Liverpool, the UK in 2008. From September 2009, he is an Assistant Professor at Qatar University, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning. He was promoted to the rank of Associate Professor in March 2019. In addition to teaching, he was the Coordinator of the Graduate Studies from September 2016 until November 2018. During the last 30 years, he published extensively in the areas of Urban Conservation in North Africa and the Gulf Region. He published over 40 conference papers, one book, two book chapters and about 20 journal papers.

References

- The Academy of Urbanism. 2011. Urban Identity, Learning from Place (2). UK: Routledge, Oxon.

- Al-Kholaifi, M. J. 2006. “The Traditional Architecture in Qatar, National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage, Museums and Antiquities Department, Doha, Qatar.”

- Al-Nakib, F. 2016. Kuwait Transformed; A History of Oil and Urban Life. USA: Stanford University Press.

- Appadurai, A. 1996. “Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization.” Public Worlds, Vol. 1.

- Boccardi, G. 2015. From Mitigation to Adaptation: A New Heritage Paradigm for the AnthropoceneIn Perceptions of Sustainability in Heritage Studies, edited by M.-T. Albert, 87–97. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Boussaa, D. 2003. “Dubai: The Search for Identity.” In People Places and Sustainability, edited by G. Moser, E. Pol, Y. Bernard, M. Bonnes, J. Corraliza, and V. Giuliani, 51–60. Germany: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

- Boussaa, D. 2010. Interview with Mr Mohamed Ali Abdulla, Souk Waqif, Doha, Accessed 6 November 2010.

- Boussaa, D. 2014a. “Rehabilitation as a Catalyst of Sustaining a Living Heritage: The Case of Souk Waqif in Doha, Qatar.” Art and Design Review 2 (3): 62–71. doi:10.4236/adr.2014.23008.

- Boussaa, D. 2014b. “Al Asmakh Historic District in Doha, Qatar: From an Urban Slum to Living Heritage.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 20(1): 2–15. Routledge. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raco20

- Boussaa, D. 2014c. “Social Sustainability of Historic Centres in North Africa: Cases from Algiers, Tunis, and Fez.” The International Journal of Social Sustainability in Economic, Social, and Cultural Context 9(3): 69–83. Common Ground. www.onsustainability.com

- Boussaa, D. 2018. “Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities.” Sustainability 10, 48 (1): 1–16. MDPI. www.mdpi.com

- Cohen, E. 1987. “Authenticity and Commoditization.” Annals of Tourism Research 15 (3): 371–386. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X.

- Connerton, P. 2009. How Modernity Forgets. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- DeSilvey, C. 2017. Curated Decay. Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Exell, K., and T. Rico. 2013. “‘There Is No Heritage in Qatar’: Orientalism, Colonialism and Other Problematic Histories.” World Archaeology 45 (4): 670–685. doi:10.1080/00438243.2013.852069.

- Fadila, A. A. 1991. “Urban Development and Planning in the State of Qatar.” Master Thesis, University of New Mexi, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- Fromherz, A. 2012. Qatar: A Modern History. USA: Georgetown University Press.

- Hadjri, K., and D. Boussaa. 2007. “Architectural and Urban Conservation in the United Arab Emirates.” Open House International 32 (3): 16–26.

- Holtorf, C. 2015. “Averting Loss Aversion in Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (4): 405–421. doi:10.1080/13527258.2014.938766.

- Holtorf., C. 2018. “Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience Is Increased through Cultural Heritage.” World Archaeology 50 (4): 639–650. doi:10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340.

- Jaidah, I., and M. Bourennane. 2009. The History of Qatari Architecture 1800–1950 Milan. Italy: Skira.

- Lane, P. J. 2015. “Sustainability. Primordial Conservationists, Environmental Sustainability, and the Rhetoric of Pastoralist Cultural Heritage in East Africa.” In Heritage Keywords: Rhetoric and Redescription in Cultural Heritage, edited by K. Lafrenz Samuels and T. Rico, 259–283. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Law, R., and K. Underwood. 2012. “Msheireb Heart of Doha: An Alternative Approach to Urbanism in the Gulf Region.” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 1 (1): 131–147. doi:10.1386/ijia.1.1.131_1.

- Lockerbie, J. “The Old Buildings of Qatar.” Accessed 1 February 2015. http://catnaps.org/islamic/planning.html

- Lynch, K. 1972. What Time Is This Place? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- McDonald, R., and H. Thomas. 1997. “Nationality and Planning.” In Nationality and Planning in Scotland and Wales, edited by R. McDonald and H. Thomas, 1–14. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- McKean, C. 1993. “The Scottishness of Scottish Architecture.” In Heritage: Conservation, Interpretation and Enterprise, edited by J. M. Fladmark, 77–93. London: Donhead.

- Montigny-Kozlowska, A. 1982. “Histoire et Changements Sociaux au Qatar.” In La Penisule Arabique d’Aujourdhui2 vols. edited by Bonenfant, 475–517. Paris: CNRS.

- Nagy, S. 2000. “Dressing up Downtown: Urban Development and Government Public Image in Qatar, DePaul University.” City & Society XII (1): 125–U7 125. doi:10.1525/city.2000.12.1.125.

- Radoine, H. 2010. “Onsite Review Report, Souk Waqif, Doha, Qatar.” Accessed 1 June 2015. http://www.akdn.org/architecture/project

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion.

- Robinson, M. 2001. “Tourism Encounters: Inter-and Intra-Cultural Conflicts and the World’s Largest Industry.” In Consuming Tradition, Manufacturing Heritage: Global Norms and Urban Forms in the Age of Tourism, edited by N. Al Sayyad, 34–68. London: Routledge.

- Salamandra, C. 2004. A New Old Damascus: Authenticity and Distinction in Urban Syria (Middle East Studies). USA: Indiana University Press.

- Scharfenort, N. 2013. “Large-Scale Urban Regeneration: A New Heart for Doha. In Focus No. 1, Arabian Humanities.” International Journal of Archaeology and Social Sciences in the Arabian Peninsula 2. http://cy.revues.org/2532

- UNESCO. 2016. “Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments; A Practical Guide to UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape.” Accessed 15 January 2017. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php

- Zetter, R., and W. Butina, eds. 2006. Designing Sustainable Cities in the Developing World. Aldershot: Ashgate.