ABSTRACT

Recent historical research has analysed the Cold War as an ‘imaginary war’, an interpretation that poses specific challenges for displaying the conflict in museums. In contrast to well-established representations of the First and Second World Wars in exhibitions, we find that the nature of the Cold War in Europe and the North Atlantic has made it difficult to tell stories of victimhood, heroism and military valour. Moreover, the memory and heritage of the Cold War have often been presented as monolithic and lacking specific chronologies, adding to the difficulty of telling stories through objects. This article explores how selected museums and exhibitions in the UK and Germany have addressed this double challenge. We examine how the conflict is portrayed, how buildings, images, text and artefacts interact in selected museums and exhibitions, and how they generate specific interpretations. We show these interpretations to be diverse and fractured: each museum chose different paths to staging the Cold War. From their comparison, in the context of heritage studies, we make the case for a distinct museology of the Cold War. We argue for a reflective approach that encourages the engagement of museum and heritage professionals with diverse material culture, filling the ‘empty battlefield’.

Introduction

Polaris Military Tartan was designed in 1964 by Alexander MacIntyre of Strone for personnel at the American submarine base at Holy Loch (). Polaris was the nuclear missile carried by the United States Navy’s ballistic missile submarines from the 1960s; it was also the name for the UK’s programme of development for submarine-based nuclear ballistic missiles from the 1960s to the 1980s that was based on American technology. The tartan has navy blue to represent the naval uniform, dark green to signify the depths of the oceans, and royal blue with gold over-checks in reference to the alternating ‘Blue’ and ‘Gold’ crews (Scottish Register of Tartans Citation1964). This tartan is on a wish-list to be acquired by National Museums Scotland as an artefact that speaks to Scottish experiences of the Cold War. Curators will use it to tell different stories – cultural/technical, civilian/military – of the local echoes of a global phenomenon. As a museum object with all the reification that this still entails (Alpers Citation1991) the tartan will become part of Cold War culture in the Britain. It highlights the multifaceted nature of this heritage, the varied objects to which such meanings attach and the different stories that we might tell with objects.

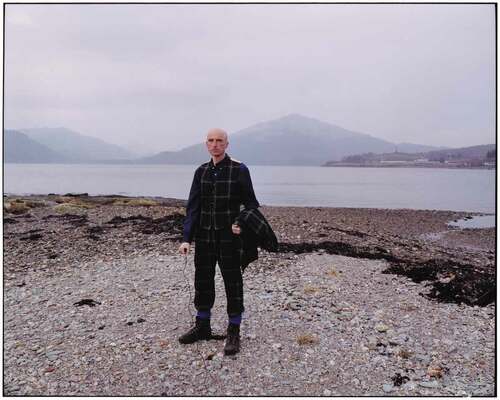

Figure 1. Artist Michael Sanders wearing the Polaris Military tartan suit he designed, standing across the bay from Coulport, north of Holy Loch, where Polaris missiles were housed and maintained during the Cold War. Image ©️ 2017 Michael Sanders. All rights reserved, DACS.

This article examines Cold War heritage in selected European museums and exhibitions and asks how these sites use artefacts to interpret the conflict. We develop our argument against the backdrop of the buoyancy of Cold War history and heritage studies. Since its end in 1989/90, the Cold War has turned from a contemporary conflict for which evidence was limited to a subject of historical inquiry and controversy for which there is an abundance of primary source material (Romero Citation2014). The Cold War now features in school curricula (Wood Citation2016), and interest in this aspect of global history can be found in online resources, television, the built environment and elsewhere. Cold War memorialisation and heritage have become topics in their own rights (Cocroft and Thomas Citation2003; Wiener Citation2012; Greiner et al. Citation2013; Lowe and Joel Citation2013; Schofield, Cocroft, and Dobronovskaya Citation2021).

In line with these developments, Cold War museums and exhibitions have developed and expanded in the United Kingdom, continental Europe, and the United States, as there has been a proliferation of matériel from the period that the armed forces wished to retire (Cocroft Citation2017, 226–27). Most recently, research has begun to focus on the global dimensions of the Cold War: 70% of those killed in conflicts between 1945 and 1990 died in the ‘Cold War bloodlands’ that ran from the ‘Manchurian plains in the east, south into Indonesia’s lush rain forests, and west across the arid plateaus of Central Asia and the Middle East’ (Chamberlin Citation2018, 2–3). Violent conflicts related to the Cold War also stretched to Latin America and the African continent. Europeans took an active role in this global Cold War (see e.g. Hong Citation2015; Westad Citation2017; Wyss Citation2021). These areas outside Europe served as ‘the staging grounds for both superpowers’ containment strategies and for new modes of revolution and resistance’ (Chamberlin Citation2018, 3).

In Europe and the North Atlantic area, however, the planning for war, armaments, fear, and ideological contestations came to matter more than the actual use of violence (Hennessy Citation2010; Nehring Citation2013; Grant and Ziemann Citation2016). As John Beck and Ryan Bishop have argued, ‘the elaborate technologies of the Cold War emerged in coextension with non-material systems of simulation, optimisation, pattern recognition, data mining and algorithms, and equally complex modes of thought’. This means that, at times, ‘the material legacies of the Cold War are visible and tangible’, such as in Cold War bunkers, but often ‘the material traces of Cold War thinking are imperceptible’ (Beck and Bishop Citation2016, 5, 9). The Cold War in the northern hemisphere was, throughout, a war of matériel and the imagination of its use (Grant and Ziemann Citation2016). The confrontation of tanks in Berlin at the point of the closure of the border between the Soviet and Western sectors on 13 August 1961 and the subsequent erection of the Berlin Wall were probably the last direct material confrontations between East and West in Europe. Subsequently, contemporary interpretations of the Cold War shifted towards perspectives that focused on signals, data and simulation, culminating for example in Paul Virilio and Jacques Derrida’s social theories in the 1980s (see Horn Citation2013; Eugster and Marti Citation2015).

As a consequence, the meanings of ‘Cold War’ have multiplied considerably over the last two decades or so. This is in marked contrast to earlier monolithic assumptions that regarded the Cold War as an ideological-cum-military conflict between two superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union), whose central faultline was the European landmass (as one of the last prominent manifestations of this view see Gaddis Citation1997). There is now a thriving international scholarship evaluating and re-evaluating the Cold War (e.g. Romero Citation2014; Farbøl Citation2015). This research has itself developed in line with the politics of the Cold War. It has had important national variations and has tended to advance in step with the release of new official documents (Reynolds Citation2017). Apart from introducing geographical complexity that explicitly discusses several Cold Wars across different locations (Lüthi Citation2020), we now find explanations of Cold War as a particular historical period, as a constellation of the international system, as a fundamentally ideological conflict as well as a series of violent conflicts for territorial and ideological control that was fought on a global level and that involved not just the two superpowers but a range of other actors (for an overview of different interpretations see Nehring Citation2012).

Despite this proliferation of Cold War scholarship and Cold War heritage, we so far lack a critical analysis and conceptual framework of how museums and exhibitions have displayed the Cold War. The construction of cultural meaning around wars is generally problematic as ‘war is the circumstance when the symbolic order and the grounds for representation collapse’ (Malvern Citation2000, 197). This was especially so for the Cold War in Europe: although there was real material mobilisation, the European Cold War was mainly fought in the imagination (Eugster and Marti Citation2015; Grant and Ziemann Citation2016); by contrast, the violence of the proxy wars in Africa, the Middle East and Asia was often forgotten (as analysed for example in Huxford Citation2018).

In this article we offer an analysis of how selected museums and exhibitions have constructed meanings from the Cold War. Our article seeks to provide an analysis of materialisation and emplotment at a number of key selected heritage sites, engaging the broader literature on Cold War heritage (see for example Wiener Citation2012; Hacker and Vining Citation2013; Jampol Citation2014). We ask how a selected group of museums displayed the Cold War, which kinds of objects they chose, which stories they sought to tell and what kind of contextual information they provided for visitors. Our objective is to provide the first analytical stock-taking of Cold War heritage in the museums and to provide the foundations for a Cold War museology.

We do this through a number of case studies for which we carried out fieldwork in 2018 and 2019: some as visitors, others involving dialogue with curators.Footnote1 In particular, we focus on a British-German comparison (on the general relevance and significance of this comparison see Pedersen Citation2010, 392–3; Rüger Citation2011) and have chosen a number of key sites for each country. The Cold War histories of Britain and Germany have been deeply entangled: both countries faced each other in two world wars, and the United Kingdom played a major role in the reconstruction of the Federal Republic of Germany as a democracy in the context of the Cold War after 1945 (see Nicholls Citation2001; Cowling Citation2019). This ideological context of the heritage of the Cold War in the western world is also why we have excluded the German Democratic Republic (GDR) from our survey, although the GDR had its own special relationship with Britain during the Cold War (Berger and LaPorte Citation2010). We have made the conscious decision not to include the heritage of the two Cold War superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union in our analytical survey, as we specifically intend to show how Cold War heritage was made in Europe as one of the geopolitical flashpoints and imaginary battlefields of the global Cold War. Our European focus enables us, too, to examine whether and how the museums and exhibitions engaged with the Cold War outside Europe.

Against this backdrop, the British-German perspective brings two aspects into focus especially clearly. First, both countries’ memory cultures have been characterised by different ways of commemorating war and by the different ways of endowing war with meaning, and by the different valuation of the military in public culture (Thiemeyer Citation2010a). Our sample enables us to discuss to what extent Cold War heritage related to these more general aspects of discussing and evaluating war. Second, bringing British and German case studies together enables us to compare and contrast how museums and exhibitions in two countries with different geopolitical positions during the Cold War – one as a power with a potential global reach and its own nuclear weapons, the other a fractured semi-sovereign polity on the European front line of the Cold War – have created Cold War heritage in museums.

Our selection of case studies enables the comparisons of geographical locations as well as the concepts and categories on display. We include not only the military museums that dominate the landscape of Cold War museology, but also those telling stories from other perspectives (as well as civilian stories in the military museums we include). We selected our sites from a broader programme of fieldwork to provide a sampling to contrast different organisational scales, national contexts, governance structures and audience constituencies.

In Germany, we consider the Military History Museum in Dresden because of its widely acclaimed unconventional approach that focuses on the anthropology of violence in war. We also analyse the display at the Allied Museum in Berlin as a museum engaging with the geopolitics of the Cold War: the museum includes some military history, but provides a contrast in governance and focus, especially in its specific geographical remit. In the UK, we selected two major military-technological museums, the permanent Cold War exhibition at Royal Air Force Museums Cosford and Imperial War Museums’ Duxford site. We complement this through an analysis of a temporary exhibition on the British secret state staged at the National Archives in Kew to investigate how exhibitions have tackled the less tangible components of the Cold War and its impact on society.Footnote2 The five case studies together include larger permanent exhibits available in their respective countries as well as smaller and temporary displays and provide us with variations of military-civilian, technical-political, geographical and governance focus .

Approaching Cold War museology

Answers to the question of how the Cold War can be displayed, portrayed and narrated in museums are far from self-evident. As Jay Winter has observed in connection with war museums, they ‘entail choices of appropriate symbols and representative objects, arrayed in such a manner as to avoid controversy especially among veterans, to hold the public’s attention and to invite sufficient numbers of visitors to come so that bills can be paid’ (Winter Citation2012, 152). Our article builds on recent work on the material cultures and museology of war and violence (Malvern Citation2000; Thiemeyer Citation2010a; Cento Bull et al. Citation2019; Echternkamp and Jaeger Citation2019). In contrast to earlier work focusing on memory, memorialisation and trauma (e.g. Crane Citation1997; Auslander Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Audoin-Rouzeau Citation2009; Arnold-de Simine Citation2013; Solaro Citation2018; Geyer Citation2020), we develop an approach from museum studies for the analysis of the heritage of war and violence.

Conceptually, we follow Magda Buchczyk’s proposal to ‘investigate the use of museum […] displays as means of creating political knowledge with the Cold War context’ (Buchczyk Citation2018, 168). Rather than focusing on the narrative history of the Cold War itself, however, we seek to investigate how selected museums and exhibitions recreated the Cold War through material objects and thus made and remade Cold War heritage. In particular, we want to trace what Tony Bennett, in an important 1988 intervention, termed the ‘exhibitionary complex’ (T. Bennett Citation2017). We are interested in how museums were responses to the ‘problem of order, […] one which worked […] in seeking to transform that problem into one of culture – a question of winning hearts and minds as well as the disciplining and training of bodies’ (T. Bennett Citation2017, 26). We want to trace the transformation of war into culture displayed in a museum, bearing in mind that ‘wars and culture do not only use culture for non-cultural ends. Culture is rather a way to produce meaning of wars and conflicts itself’ (Weichlein Citation2017, 23, 47).

Unlike Bennett, however, we conceptualise museums and exhibitions not as fixed à la Michel Foucault’s discourses, but as ‘non-exhaustive patterned combinations and relationships’ (Macdonald Citation2013, 5), in which the exhibitionary complexes themselves ‘gain autonomous meanings, effects and possibilities’ (Whitehead et al. Citation2015, 8). We seek to expose the three-dimensional ontologies of the Cold War in selected museums and exhibitions as maps – maps that represent a real landscape, but that also come with specific ‘conceptual and epistemological geographies’ (Whitehead et al. Citation2015, 13), and maps that can be used differently by different people. By fixing heritage in one place, museums and exhibitions historicise objects and their contexts – and they have done this especially with regard to ‘antagonistic positions’, ‘differences and tensions’ (Whitehead et al. Citation2015, 15, 46). All museums and exhibitions, ‘through representation, construct social and political orders and values’ (Whitehead et al. Citation2015, 50).

However, the landscape of Cold War heritage research which museums might map mostly reproduces, as far as Europe is concerned, the classic portrayal of the ‘empty battlefield’ (Ziemann Citation2008, 237–238). The main trope of such interpretations is an empty landscape into which technological or military structures have been planted, many of them now abandoned: ‘modern warfare’s complete devastation of an environment creates the ideal condition for the operation of modern armor, communication, and surveillance devices’. What is left is ‘[o]nly mathematical space emptied of human experience’ (Hüppauf Citation1993, 74).

The Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously called war the ‘continuation of politics by other means’ (Clausewitz 1918 (Citation1832)). Turning Clausewitz’s dictum around, the German anthropologist Thomas Thiemeyer has observed how military museums and exhibitions offer the ‘continuation of war by other means’ as museums seek to capture events that visitors may not have experienced themselves (Thiemeyer Citation2010a, 462). But it is an open question as to how this portrayal works in light of recent developments in military history. Such research has moved away from the depiction of battles, fought by more or less anonymous armies under great commanders, towards interpretations that highlight the interactions between organisational structures, technological developments and the experiences of soldiers on the battlefield, often also emphasising the gendered nature of such experiences and representations (Kühne and Ziemann Citation2000).

This trend has also been reflected in the ways in which war and fighting have been exhibited in major museums. There has been a shift – in some cases more pronounced, in some cases less so – from exhibiting guns, armour, and weapons towards highlighting the fact that wars are about killing and dying. Such interpretations focus on the role of human beings in war and the military (Thiemeyer Citation2010a in contrast to the earlier findings by Zwach Citation1999). Over the last decades, there has been a growth of articulations of such narratives in military museums, whether celebratory, sanitary, or more critical (Dechow and Leahy Citation2006; Lisle Citation2006; Scott Citation2015; Cento Bull et al. Citation2019). But within this framework, military museology has focused primarily on the First and Second World Wars (Barton Hacker is a notable exception, cf. especially Hacker Citation2014), conflicts that lend themselves more immediately to such approaches because they are actively commemorated (Thiemeyer Citation2010ab; Muchitsch Citation2013). Elements of disaster, destruction and human loss also echo in studies of Peace Museums (e.g. Apsel Citation2016), ‘difficult heritage’ (Logan and Reeves Citation2008; Macdonald Citation2009) or ‘toxic heritage’ (Wollentz et al. Citation2020).

Transgressing these museological discussions, Wayne Cocroft and colleagues have emphasised the breadth of the material legacies of the Cold War, which ‘went far beyond military installations, embracing or influencing many aspects of popular culture, science and technology, architecture, landscape and people’s perceptions of the world’ (Schofield and Cocroft Citation2007, 15; see also Cocroft Citation2007, Citation2014). Discussions on Cold War heritage are especially vibrant in northern Europe, mainly because of the abundance of relevant sites there (Axelsson et al. Citation2018; Farbøl Citation2015). Other work has tried to use the heritage sites for community projects that fill the empty sites of potential future battles with meaning and to relate this to the sounds, smells and feelings that these sites evoke today (Wilson Citation2007). Discussions in the UK and elsewhere have primarily taken place in the context of industrial and technological heritage, however. They have rarely ventured beyond these analytical confines. Nuclear installations, both civilian and military, or those linked to them have perhaps received the most consistent and systematic attention in heritage scholarship, emphasising nuclear weapons and the nuclear arms race as the specific characteristic of the Cold War (cf. Cocroft Citation2007, 114–16).

The Cold War on display

Museums build upon, reflect and develop the state of the field we have outlined. We now discuss how they display the Cold War and how they thus make and re-make Cold War heritage. In what follows, we assume that museums ‘create knowledge about the subjects they seek to represent’ (Moser Citation2010, 22), focusing the ‘modes of display [that] frame the visitor’s encounter’ (Mason Citation2013, 167). Applying the conceptual frameworks developed by Moser (Citation2010) and Mason (Citation2013), we analyse museum objects in light of the emplotment of artefacts in overarching narratives. We are particularly interested in whether a plurality of views has been represented, how objects are used (to speak for themselves or as part of experiential or even experimental spaces), as well as the forms of display (didactic or merely showing the objects). We also pay attention to the ways in which time, ruptures and chronology are addressed in the museums and exhibitions; the relationship between texts, images and installations; and, not least, the ways in which museums and exhibitions refer to national histories or seek to capture global, trans-national or sub-national developments.

The Museum of Military History, Dresden: wrestling with Cold War violence

The Bundeswehr’s Museum of Military History in Dresden presents military history from an anthropological standpoint (Militärhistorisches Museum Citation2019): ‘the human, who spreads violence and who suffers from it, is at its heart’.Footnote3 The building in which the museum is housed offers itself a glimpse into German military history and a German history of violence. The building, constructed between 1873 and 1876, originally served as the armoury in the German state of Saxony and became – this was common at the time – a museum in 1897. It maintained its function as a museum through the period of Soviet occupation and the history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) as the Armeemuseum der DDR (Army Museum of the GDR).

The museum was closed to the public in 1989/90 during the period of reunification. In a 1994 directive by the German minister of defence, the Militärhistorisches Museum Dresden ‘was assigned the role of the leading museum in the Bundeswehr network of museums and collections’ (Pieken Citation2013, 63). In 2001, an architectural competition was held to award a contract for an extension that would help to historicise this history and the history of war and violence in German history. Daniel Libeskind – who had already redesigned the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester – won the competition. After extensive renovations, the museum opened its doors to the public in October 2011 as the Bundeswehr Military History Museum, maintaining its function as a military institution but simultaneously aiming to offer a critique of violence and the military. It does this mainly through its permanent exhibition entitled ‘Violence, Culture, History’ and a number of smaller temporary exhibitions that address specific themes relating to the history of the German armed forces in the Second World War and the Holocaust (see Pieken Citation2013, 63–66). Through this approach, the museum moved intentionally away from the traditional concept of military museums as displays of military technology – weapons and uniforms – towards an approach that emphasised violence and a pluralism of perspectives that includes both victims and perpetrators. Owing to its affiliation with the Bundeswehr, the museum’s intended audience is not only the general public, but it also targets soldiers of the German armed forces (Cercel Citation2018, 3–4).

The permanent exhibition is split in two parts, separated through Daniel Libeskind’s stunning architecture – a gigantic wedge that perforates the classical building, a former weapons arsenal used by the Saxon kings (). The wedge symbolises both the violent ruptures of German history – and especially the Holocaust – as well as the fractured conceptualisation of the traditions on which the German army after 1945 relied (Thiemeyer Citation2012). Fractures were also a theme in his earlier work, including the Imperial War Museum North and the Jewish Museum in Berlin. The Bundeswehr Military History Museum’s wedge also brings out the museum’s general approach that does not merely want to tell one story but highlights the ‘shattered past’ of German history (Geyer and Jarausch Citation2003). An observation platform on the fourth floor of the thematic section of the museum’s permanent exhibition offers a view over Dresden, whose historic city centre was more or less completely destroyed by Allied bombers and subsequently reconstructed (Pieken Citation2013, 65–66). While a more conventional section presents a chronological account of German military history through artefacts, cross-cutting corridors explore a number of themes that highlight how individuals in war have meted out violence and how they have suffered it, and in which structures and through which technologies they have been able to do so, thus thematising ‘the intricacies of agency in contexts of extreme coercion’ (Cercel Citation2018, 13–16, 23).

Figure 2. The Bundeswehr Museum of Military History, designed by Daniel Libeskind, showing the giant wedge violently perforating the classical building. Image: MHM / Nick Hufton.

The result is a museum that still bears a resemblance to traditional museums as ‘temples where national identities are produced and reinforced’, but it also offers a forum that emphasises ‘counter-hegemonies, undecidability, contingency and open-endedness’. (Cercel Citation2018, 8, following the distinction by Cameron Citation1971). In highlighting that latter ‘agonistic’ aspect, the Dresden museum resembles some of the more innovative museums of the First World War (Cento Bull et al. Citation2019). There is, however, no direct engagement with the question of how the Cold War can be conceptualised – the conflict does not figure explicitly in the thematic sections, although the section on dual civilian/ military use is relevant in this context. The section on ‘Protection and Destruction’ includes the simulation of the explosion of a nuclear bomb by the artist Ingo Günther, ‘which temporarily etches visitors’ shadows to a phosphoric wall for a few seconds’. (Pieken Citation2013, 74). In the chronological sections, the Cold War becomes one episode for the history of the German Army (and to a lesser extent the GDR’s National People’s Army). The focus here is on its internal organisation as an explicitly democratic army, while also highlighting controversies, such as the debate about NATO’s dual-track decision and the stationing of Pershing II nuclear missiles in the Federal Republic in the early 1980s (Pieken Citation2013, 79).

Global dimensions are more or less absent from the museum for the Cold War period, where the focus is primarily on the German-German confrontation, shown through the display of military kit. In its treatment of the nuclear threat, the museum stages the Cold War as an ‘imaginary war’, but it also narrates the chronology of the Cold War so that visitors can imagine the Cold War as a conflict where ‘the armies of the two German states are presented in parallel’ (Cercel Citation2018, 22). This reflects the Cold War confrontation insofar as it opts for an explicitly ‘liberal-hegemonic’ interpretation, which finds fault mainly with the East German Nationale Volksarmee (National People’s Army, NVA) (Cercel Citation2018, 22). This is probably also a reflection of presenting the official-governmental version of German unification in general and the dissolution of the NVA and its integration into the Bundeswehr in particular, as a means of education for recruits and officers. The Dresden Museum therefore embeds the understanding of the Cold War in an almost absolute lack of specific groundedness: the museum establishes a virtual site of memory with a specific educational purpose. The key message is one about the role of the German military in the context of Germany’s politics of the past, explicitly National Socialism and more implicitly the history of democracy.

Allied Museum, Berlin: symbolising geopolitics

More specifically related to the Cold War are those German museums and exhibitions that focus on the German division, with Berlin being the symbolic reference point (for context see Dülffer Citation2008; Danylow and Etges Citation2013; Harrison Citation2019). The AlliiertenMuseum (Allied Museum) explores the American, French and British occupation of Germany generally and Berlin in particular. Unlike the museum in Dresden, it gives the Cold War a concrete location: Berlin as the Cold War’s capital city (on the historicisation of this view cf. Daum Citation2008).Footnote4 The global dimension is refracted through one city, which brings both benefits and distortions. The museum is housed in the south-western Berlin district of Steglitz-Zehlendorf, the former American sector in Berlin, at a site close to the former Berlin headquarters of the US Army. The museum occupies the former US cinema ‘Outpost’ and the Nicholson Memorial Library. It opened its doors to the public in 1998 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Berlin airlift. The idea for such a museum originated with civil society groups in Berlin who wanted to mark the American presence in the city immediately after German reunification in 1991. These efforts culminated in the ‘Charter for an Allied Museum’ drawn up by international experts in 1995 and the foundation of the non-profit association AlliiertenMuseum e.V. (Danylow and Etges Citation2013; Museum Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

Outside, the forecourt features vehicles that symbolise the connections between the surrounded city and the West: a train carriage and, most strikingly, a Hastings TG503 airliner. Inside, vehicles also feature prominently, including an American Jeep. The main building is the converted US Army cinema, its auditorium re-purposed to stage the dramatic narrative of geopolitical confrontation, with extensive use of costumes on mannequins. The architecture thereby reminds visitors of everyday life during the Cold War, its impact on all residents of Berlin and beyond, and how it pervaded culture (in this case, cinema). Within the auditorium, senior military and civic figures – almost exclusively male – feature as actors of occupation. Juxtaposition of the uniforms of the nations involved makes for a striking international comparison, a trope that is repeated throughout with other media. The interpretation is around networks of communication, people and goods, pitched to appeal to international visitors, heritage enthusiasts and, especially, school groups. Accordingly, the story is clear, didactic and largely linear.

The museography is heavily text-based, a strong narrative illustrated by objects and different media. It uses reproductions of photographs, and in the early stages of the visitor journey, archival material to evoke feelings of authenticity. Maps feature throughout, including a large reproduction of an aerial photograph, which serves to emphasise the geographical specificity of the story. The Cold War appears as international (if largely European), but encapsulated within the epicentre of Berlin, here as elsewhere in the city’s heritage landscape. Among the objects, the museum focuses especially on communication technologies: radio equipment, typewriters and a red British telephone kiosk; the Cold War played out in day-to-day life. Unsurprisingly, there are fragments of the Wall, but they are overshadowed by the large section of a so-called ‘spy tunnel’ (). By these later stages of the display, the focus has turned to everyday street life and co-existence, the Wall (in images at least), military defence, and stories of escape.

Visitors are offered a specific path through the exhibition across two buildings, following the timeline of the Western powers’ occupation. The chronology pauses for a detailed section on the Berlin airlift of 1948 – foreshadowed in the visitor journey by the TG503 airliner outside – even though there are otherwise few surviving objects to illustrate it. Like many aviation collections, the museum uses model aircraft, but most striking is a small parachute that had been used to drop candy into the city. The interpretation presents both Western and Eastern perspectives on the airlift: whether a humanitarian project or covert American aggression. But, in general and unsurprisingly, the perspective is Western.

The museum includes a changing temporary exhibition space, which from 2016 housed 100 Objects: Berlin During the Cold War, displaying material culture from a much wider range of aspects of life, from board games to flags to traffic cones, juxtaposing high politics with espionage and humdrum existence in the city (Von Kostka and Helwig Citation2016). 100 Objects followed the vogue of history-through-things as advocated by the British Museum (MacGregor Citation2010) in which objects symbolise larger-scale historical events and processes and stand in for a chronological story-led narrative, in contrast to the approach in the standing displays. The range of objects – as comprehensive as we have seen – was a rich experience of the experience of Cold War everyday life in Berlin for its citizens – including, refreshingly, the material culture of the domestic realm, including kitchen technology and children’s toys. Of the institutions and exhibits we have considered in this partial review, 100 Objects gave the most intimate, geographically grounded glimpse into everyday life. Curators emphasised the objects’ charisma, letting visitors weave a narrative from them rather than seeking to impose a concrete or chronological account.

The Secret State at Kew: controlling the Cold War

Unlike the museums in Dresden and Berlin (but similar to the 100 Objects exhibition in Berlin), Protect and Survive: Britain’s Cold War Revealed was a temporary exhibition that was on display at the UK National Archives in Kew from April to November 2019. Its main focus was on the British intelligence machinery as a specific form of Cold War statehood.Footnote5 The exhibition faced the challenge of having to portray the machinery of government and its relevance for the Cold War more generally through archival evidence. The setting focuses explicitly on the British experiences of the Cold War, but also provides a rough chronology of British contributions to European geopolitics. The global context is almost entirely absent. On entering, visitors are greeted with a sign ‘You are now entering an official government bunker’, under the watchful gaze of a large white CCTV camera. The sign also requests that visitor ‘take an official pass’. Visitors can choose from three stickers: Regional Scientific Adviser, Principal Medical Officer, or Camp Commandant, three different functions within the UK state’s civil defence operation. As visitors enter this ‘bunker’, they experience the exhibition space as a key site for ‘both the landscapes of the mind and those on earth’ during the Cold War (L. Bennett Citation2017, 7). The exhibition encouraged its visitors to become collaborators in co-creating the Cold War. A red notice board at the end asks visitors to collect their experiences on post-it notes under the heading ‘Cold War Witness’.

Thus equipped, visitors embark on a more or less chronological tour of the Cold War, illustrated through some key junctures that emphasise Britain’s secret state and its activities along a number of themes. These are arranged in rough chronological order: the break-up of the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union; Britain’s development of nuclear weapons; war games; spies and spying; civil defence measures and regional seats of government; the cultural Cold War; the protests against nuclear weapons of the 1980s and Britain’s role at the end of the Cold War. Each juncture is illustrated through documents from the National Archives, leaflets, posters, TV footage and some reconstructions including a civil defence shelter. The role of the United States for the Cold War, NATO, or indeed any other Allied nation is almost absent; similarly connections between Britain’s secret state at home, decolonisation and the Cold War outside the North Atlantic have been completely neglected – the story told is essentially British and reflects a narrow view of what the Cold War involved for Britain – it is not surprising, therefore that the brief 33-page catalogue mostly lists popular accounts of the Cold War, many of them now regarded as out of date (National Archives Citation2019). An illuminated map of key sites relating to the Cold War secret states, such as Regional seats of government, dominates one of the walls. A few metres in front of it, visitors see a large wooden table with a red telephone on it.

The main impetus of the exhibition, as its sub-title suggests, is one of ‘revelation’ – of pulling back the veil of secrecy around the British state’s preparations and letting visitors participate in the uncanny wonder of ‘what we now know’. This narrative of the Cold War is, in itself, a product of the conflict: ‘secrecy and dissimulation are […] the flipside of the logic of deterrence which held the hot war in the cold war at bay. Public demonstration of one’s own strength […] on the one hand, paranoid secrecy on the other are two sides of the […] para-communication between the Cold War opponents’. (Horn Citation2007, 337). So, the Cold War that emerges from the Secret State exhibition is one that highlights the all-encompassing nature of state power, and one that was largely benign: the principle of ‘protect and survive’ that the exhibition took from subsequent civil defence pamphlets seemed to have worked – by averting the disaster of nuclear annihilation. At the end of the exhibition, visitors can leave their own memories of the Cold War under the heading ‘Cold War Witness’ on a red pinboard. They thus become part of the Cold War heritage displayed at the museum.

Here, the Cold War appears totalising, potentially lethal, but also almost always under control, as symbolised by the images of maps and command stands with screens and radars. The exhibition directly reflected recent research on the importance of the Cold War for forging images of citizenship (Grant Citation2011). However, it had little to say on the political and social relevance of these scenarios or indeed experiences, differentiated by class and race. In particular, the kind of citizen involvement it simulated through the stickers was directly related to Cold War notions of civic duty and did not directly discuss questions of gender. This was also a predominantly British story: it was the British state, and the British state alone, that fought its ideological opponent in the Soviet Union.

The National Cold War Exhibition at RAF Cosford: The aura of technology

While Protect and Survive was a small and temporary exhibition, our final analyses tackle two principal sites for the commemoration of the Cold War in the UK: the National Cold War Exhibition at Royal Air Force (RAF) Museum Cosford and the Imperial War Museum’s Duxford site (). Both seek to attract a core audience of family groups and school visits alongside military and aviation enthusiasts. The former is housed on the site of RAF Cosford, a site used for the training of RAF engineers since the 1930s, which also housed an RAF hospital until 1977. The exhibition’s stated aim is to tell a ‘story of the Cold War [that is] much larger than one of aviation alone; this national exhibition aims to inform and educate present and future generations about the immense threat posed to world peace and security during this significant period of the 20th century’ (RAF Museum Citation2020a).Footnote6

Figure 4. Aviation dominance: the National Cold War Exhibition at RAF Museums Cosford. The dramatically vertical English Electric over two of the three V-bombers. Image: RAF Museums.

On their way to the visitor centre, visitors approach the large and imposing hangar that houses the National Cold War Exhibition through a path flanked by aircraft used by the RAF until the 1980s. The steel building was custom built and completed in 2007 and ‘made of two curvilinear triangles’ (Lowe and Joel Citation2013, 170). Although not as dramatic as Libeskind’s intervention in the Museum of Military History (), the shape of the building symbolises simultaneously the importance of aviation, technostructures and technology for the Cold War, ‘the fractured Cold War world’ (Cocroft Citation2017, 227), and the threat posed by it. Inside, the £10 million display space is dominated by large technology, mainly by three V bombers (whose full extensions can only be glimpsed properly by taking the stairs up to a gallery that surrounds part of the display area) and a vertically displayed English Electric Lightning supersonic jet seemingly shooting towards the sky. All objects played a role in the deployment of the British nuclear deterrent prior to the introduction of submarine-based missiles in the mid-1960s (RAF Museum Citation2020b). Throughout, the description and explanation of artefacts is minimal and relies primarily on the use of the website to make sense of the ‘gleamingly maintained’ aircraft (Lowe and Joel Citation2013, 170–1). In terms of its chronology, the display encompasses the importance of the RAF for British nuclear deterrence, with some glimpses towards Europe, the United States and the Soviet Union, with some displays covering technological artefacts relating to wars outside the North Atlantic area. Visitors are at liberty to explore the exhibition by following their own interests – there is no prescribed route through the exhibition.

Among the densely displayed aircraft, stand-alone pods focus on particular aspects of the Cold War. One is devoted to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and protests against nuclear weapons. Without much explanation, the pod shows a number of banners and posters, mainly relating to the Greenham Common Peace Camp and CND in the 1980s more generally. Other displays show images of life in the Soviet Union, highlighting its character as a totalitarian society, with one display highlighting drunkenness among Soviet soldiers as a particular problem.

On the lower level, the exhibition focuses on the German-German division as the main geopolitical flashpoint of the Cold War. It does so primarily through a recreation of a Berlin border crossing. Artefacts here include an orange VW Beetle, perhaps chosen as an icon for Cold War consumer culture, but mainly because a military commander authorised the start of car production in the Wolfsburg plant in the British zone of occupation in 1945 (RAF Museum Citation2020c). There is also an Opel Senator used by the British Commanders in Chief to the Soviet forces in Germany, which includes some special features such as four-wheel drive as well as ‘infrared and tactical lights for night-driving’ (RAF Museum Citation2020d).

In line with its affiliation to the RAF, Cosford’s exhibition is at its core a traditional military museum: it presents national technological artefacts and highlights Britain’s contribution to the Cold War emphasising British technological prowess in line with a model of British national identity that was especially prevalent from the late 1950s into the 1980s and that framed Britishness in terms of technological modernity (Edgerton Citation2013, Citation2018). In the exhibition, the Cold War appears primarily as a conflict around the nuclear arms race, military technology, and the ideological confrontation between the Eastern and Western blocs, so that its global component is not explicitly addressed. Given that there is no single path through the exhibition, there is no single overall message. The museum relies on the auratic power of the artefacts to provoke discussions and emotions. A complete list of items, including more information on the objects, is available on-line and provides the audience with an opportunity to reflect on their visit, appealing especially to those interested in the technological aspects of the military confrontation. Similar to the displays in the other museums, there is no explicit discussion of gender – as the objects appeal primarily to technological aficionados, there is at least an implicit assumption of a male gaze here (cf. L. Bennett Citation2013). Extra-European developments are entirely absent from the main exhibition. One of the hangars does, however, include an exhibition that displays weapons used in colonial or post-colonial settings. But there is no reference to the specific historical context in which these weapons were used, thus potentially reproducing colonial patterns of engaging with technology and warfare (cf. the debate between Wagner Citation2018 and H. Bennett et al. Citation2019).

There is also a programme for educational visits from schools, addressing pupils aged 11 to 16. Like the exhibition itself, these programmes focus on making the artefacts speak by providing technological details and combining these details with stories, sometimes told by former RAF personnel (RAF Museum Citation2020e). At Cosford, the Cold War therefore remains an empty battlefield: violence itself is abstract and can only be grasped through planes and weapons. Time seems to be more or less absent from the display of British weapons and technology from different periods of the Cold War, which sit next to reconstructed elements such as the Berlin border crossing. So, on one level, this exhibition portrays the Cold War as frozen time. On the other, however, by doing so, it enables visitors to use the displayed artefacts to tell their own stories and to discuss Cold War stories with the volunteer guides on the gallery floor. The museum eschews, despite its stated intentions, a broader explicit pedagogical message.

IImperial War Museum, Duxford: Centring the Cold War

Although there are Cold War displays at Imperial War Museums (IWM) sites in London and Manchester, IWM concentrates its main Cold War holdings at Duxford in Cambridgeshire. Opened as a museum in 1976, the site was originally a Royal Flying Corps training depot from the era of the First World War, and most of its historic buildings are functional elements from the airfield, active from the 1920s until 1964. A large concrete apron survives from the Cold War era, on which civilian airframes owned by the Duxford Aviation Society have been arranged. The effect is to make the visitor feel as if they are entering an active civilian Cold War era airfield (particularly on the days when enthusiasts are taking off from the adjoining active runway).

Some civilian elements are also present in the largest exhibition, in the Airspace hangar, opened in 2007, where a Concorde and a Vulcan bomber (bomb doors open for visitors to stand in) sit side by side. A Polaris missile acts as an indoor gate-guard, and a Handley Paige Hastings C1a transport aircraft represents the Berlin airlift. In this hangar the timeframe is loose, and the Cold War is embedded in a the longer chronology of twentieth-century conflict, including the world wars. The interpretation is sparse and technical, with a few pilot biographies, but an overall emphasis on engagement with STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). Like the RAF Museum, then, Duxford overall is dependent on aircraft to tell the history of the Cold War. Land vehicles feature more prominently at Duxford, however, especially in another hangar devoted to the land war hangar which addresses the Cold War proxy wars including Korea. Most striking is an American TEL (Tractor, Erector, Launcher) vehicle with its ‘Honest John’ missile (a nuclear missile with only a 37 km range). These and other military hardware, interpreted with technical details, dominate a chronological journey in which proxy wars are self-contained techno-military episodes.

A greater variety of objects and interpretations can be found on site in the American Air Museum, 50% of which is funded by the United States Air Force, built in 1997 and refurbished in 2016.Footnote7 Here, the Cold War can be found nestled between the Second World War and the euphemistic ‘Desert and Mountain War’ around the world. This broader twentieth-century battlefield is far from empty, dominated overhead by the vast B52 Stratofortess, iconic of American Air dominance, as well as a U-2 Bomber, threatened by a Soviet SA-2 missile. Below these giant suspended artefacts are multi-media and multi-disciplinary pods that use a range of interpretative methods and material culture, offering multiple routes through the material within a broadly chronological arrangement.

The exhibition includes different perspectives: not only those of pilots, but also of engineers; not only American, but also British and Soviet voices. Specific individuals provide biographical hooks rather than sweeping international chronologies. The Greenham Common display in particular includes ephemera and oral history from peace campaigners, US personnel, and UK police officers (cf. Fiorato Citation2014). Objects dominate, but image and word are also juxtaposed engagingly. Visitors can browse extensive first-person accounts from the different actors on screen, on long labels and in reproductions of primary material including diaries. Like the Allied Museum, the American Air Museum uses costume extensively, from pilot uniforms to George H.W. Bush’s suit (the only one to be found outside the US). Here as elsewhere the display gives a sense of the human scale below the aircraft and ordnance. Narratives around these objects are nuanced and varied, providing an unusual range of perspectives, from peace campaigner Debbie Handy (including her accordion, complete with its case adorned with protest stickers, see ) to RAF pilot Martin Loveridge (whose Aviator sunglasses, according to the label, are redolent of the 1986 motion picture Top Gun). Social and political elements and their associated material and print culture are, however, overshadowed (literally) by the giant aircraft. Overall, Duxford’s Cold War is framed from the UK and US perspectives, an aerial war-that-never-happened in Europe and the north Atlantic in hangars or hangar-like architecture. The imaginary war is presented as one episode in a conflict-ridden century.

Conclusion: materialising the Cold War

Like the Polaris Military Tartan, the heritage analysed here has a complex weave. The Cold War that emerges from this analysis of selected museum displays and exhibitions is not monolithic and fixed, but diverse and fluid. Each museum approached the conceptualisation of the ‘Cold War’ differently – and some of the museums (Dresden and Cosford in particular) chose to make fracturedness and diversity the main topic of their displays. There are two main findings of our survey: first, as with more traditional displays relating to the First and Second World Wars, the displays in military museums we examined emphasise the importance of moveable technological artefacts: weapons, machines, planes, cars and tanks serve as placeholders for the war-like character of the Cold War. But the real or potential use of these weapons is rarely discussed. Nor did the displays we examined engage analytically and deeply with the importance of location on the one hand and the global nature of the Cold War on the other. On the contrary, the AlliiertenMuseum shows Berlin as the central location of the Cold War (though without engaging directly with the cityscape and without suturing it directly to the global Cold War). The two exhibitions based on former airfields – Duxford and the national Cold War museum – do not explicitly reflect on their location; the airfields are clearly used for the site, but they have not themselves been historicised in Cold War terms. Dresden conceptualises itself as a virtual site of memory, in which the museum’s architecture is used to convey a message about the fracturedness of modern German history and the violence that characterised it.

None of the museums we studied thematises the global nature of the Cold War as a zone through which we might glimpse the real violence of this conflagration. Instead, as is evident especially in the display at RAF Cosford, the violence nestled within the weapons from those conflicts but was not discussed explicitly. Conceptually, this reflects the debate among historians about how best to write the history of weapons and violence – as a social history of experience or as a history of technology (cf. Wagner Citation2018; H. Bennett et al. Citation2019). One might conclude from this that the global dimension is simply excluded in favour of reifying local and national perspectives. However, all the museums we discussed at least leave the space to see these local and national experiences are ‘enmeshed and co-constitutive’ with the global (Mason Citation2013, 40). The displays at Duxford, Cosford and especially at Dresden allow the interpretative and experiential flexibility for audiences and for curators to bring the global back in.

Our second main finding is that there were no general national differences between our British and German examples. The nature of the Cold War in Europe and the North Atlantic seems to have made it difficult to tell stories of national victimhood, heroism and military valour, three key reference points that have structured war exhibitions in the UK, continental Europe and elsewhere (Thiemeyer Citation2010a). The possible exception to this finding is the Military Museum in Dresden. Its pedagogical focus on the nexus between army, violence and democracy relates directly to mainstream German memory discourses in connection with National Socialism (Niven, Citation2001 ; Cercel Citation2018). Yet taking the Cold War-related sections of the museum for themselves, there is no specific interpretation that one might not have transferred to the British context.

We could not find a strong relationship between a museums’ pedigree and governance on the one hand and its interpretative approach on the other. There are similarities in approach between the UK National Cold War Exhibition (with its links to the Royal Air Force) and Imperial War Museums’ Duxford site, but they contrast with our experience at Dresden. None of the exhibitions we have analysed, meanwhile, explicitly addresses the global nature of the Cold War – they follow more traditional interpretations of the Cold War as a geopolitical-cum-ideological conflict centred on Europe in which technology played a key role; they mostly do not engage with the broader recent attention to Cold War material cultures of art and design, although there has been some concrete museological engagement in this area (see, for example, Crowley and Pavitt Citation2008; Jampol Citation2014; as well as Hogg Citation2016).

Apart from the temporary exhibitions 100 Objects at the Allied Museum and Protect and Survive at Kew, the museums and exhibitions analysed here followed, on the whole, chronological stories through technological objects, and none of the museums overlaid their exhibits with explicitly pedagogical material that directed the audience’s gaze. Rather, the exhibitions we discussed work by relying on the aura of objects: the aura of fighter bombers and rockets as both technological wonders and awesome death machines; the aura of declassified papers and formerly secret sites in letting the audience in on the often uncanny secrets of the Cold War state; the uncanniness of empty uniforms; or the aura of empty and now disused airfields and bunkers enabling imaginations of what the Cold War was like.

All the museums we considered here portray the Cold War, in analogy to the Second World War (Thiemeyer Citation2010a: 488), as a war in which the good triumphed over evil, and where the objects displayed signify that fight. In the British and German museums, the underlying narrative is one of the victories of democracy over dictatorship and totalitarianism. Interestingly, two of the military museums with close links to the armed forces – the Cold War Museum at Cosford and the Dresden Military Museum – offered the least direct guidance for their visitors and left them to explore some of the context themselves, although the Dresden Museum communicates an underlying message about the anthropology of violence explicitly. Rather, they provided cool surfaces of Cold War artefacts to generate warm emotions, either admiration for the technological objects, bemusement about some of the artefacts, but also perhaps some questioning of the rationale that led to the building of these objects. The museums focusing on technological objects especially do not explicitly discuss questions of gendered experiences of the Cold War – but, like in other war museums, the ‘war machines are staged as if in a gigantic children’s toyshop’ (Malvern Citation2000, 197), and these have traditionally attracted more men than women.

More recent literary scholarship on the Cold War has pointed out that ‘by enscribing (…) experiences and stories within the established representational canon (…) those who engaged with the Cold War rift attempted to render it physically, perceptually, emotionally, and intellectually accessible, and hence surmountable’ (Komska Citation2015, 238). This conclusion also applies to experiences of Cold War museums: by placing artefacts in specific spaces, illustrating them with texts, images and film, or by simulating Cold War experiences, museums re-produce the Cold War, each in their own way; they thus make Cold War heritage. By displaying artefacts from the period of the Cold War, museums therefore not only engage with Cold War scholarship. Their classifications and interpretations also influence definitions of what the Cold War was, both among their audiences, and, potentially, among historians. Although none of the displays we studied reflects the recent global turn of Cold War scholarship and although they remained committed to more traditional interpretations of the Cold War as an ideological-cum-geopolitical conflict that was predominantly in and about Europe, the displays nonetheless have a productive force for historical scholarship: they highlight the importance of artefacts and their locatedness for thinking through the diverse ways in which the Cold War was made and un-made.

This, we argue, is the basis from which we can develop a distinct Cold War museology. We hope that our essay has established the foundation on which to conduct reflective discussions beyond our case studies, between and among museum studies and heritage scholars, museum anthropologists, media scholars and contemporary historians. Only such collaboration will enable us to populate the empty battlefield and materialise this imaginary war. This means that there is potential energy to harness, not only across different kinds of collections, but also across different media. Our main focus here has been on objects, resources found in archival, photographic and film collections may complement material culture stored in museum collections facilities (Brusius and Singh Citation2017).

Walter Benjamin assumed that mechanically reproduced objects lacked their ‘presence in time and space’ and thereby lost their aura (Benjamin 1969 (Citation1935), 3). But the artefacts we encountered have gained a new aura – and new authenticity – in the context of the Cold War museums and exhibitions. This has not happened by evoking the ‘experience of [humanity’s] destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order’ (Benjamin 1969 (Citation1935), 3), but instead by gazing at the technological artefacts in awe and wonderment, precisely because the context of killing and dying is not shown. The museums pacified the Cold War by converting it into culture (cf. Bazon Brock cited in Trenkler Citation2018), thus filling the empty battlefield in different ways. The museology of the Cold War we develop in this article makes a case for a conceptually informed and nuanced reflection on this process of meaning making.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bernd von Kostka, Allied Museum; IWM curators Craig Murray and Emily Charles; Sarah Harper, University of Stirling and National Museums Scotland; Julian Jones, Heriot-Watt University; Siân Jones and Nina Parish, University of Stirling; Calum Robertson, National Museums Scotland; Michael Sanders; Fiona Alberti; and our helpful peer reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samuel J.M.M. Alberti

Samuel JMM Alberti PhD FRSE is Director of Collections at National Museums Scotland and an Honorary Professor at the University of Stirling’s Centre for Environment, Heritage and Policy. He has curated exhibitions on race, museum history, and the First World War; his books include Nature and Culture: Objects, Disciplines and the Manchester Museum (Manchester University Press, 2009) and Morbid Curiosities: Medical Museums in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Oxford University Press, 2011). His book on science and technology collections will be published in 2022. From October 2021, he is Principal Investigator on the major research project ‘Materialising the Cold War’, generously funded by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/V001078/1).

Holger Nehring

Holger Nehring is Professor of Contemporary European History at the University of Stirling. He holds a DPhil from the University of Oxford and has published widely on the transnational and comparative history of social movements during the Cold War, especially peace movements. His publications include Politics of Security. British and West German Protest Movements and the early Cold War, 1945-1970 (Oxford University Press, 2013) and (co-edited with Stefan Berger), The History of Social Movements in Global Perspective: A Survey (Palgrave, 2017). Together with Samuel Alberti, he is co-investigator on the major AHRC-funded research project ‘Materialising the Cold War’ (AH/V001078/1).

Notes

1. Our broader fieldwork included exhibition assessments at RAF Museums Cosford (18 January 2018, as visitors); the Atomic Weapons Establishment Non-Classified Museum, Aldermaston (11 June 2018, with staff); Stiftung Berliner Mauer (3 November 2018, as a visitor); Imperial War Museums Duxford (7 May 2019, with staff); Alliierten Museum, Berlin (7 November 2018, dialogue with staff after a visit); Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin (3 November 2018, as a visitor); Bunker 42 Cold War Museum and Entertainment Complex, Moscow (17 March 2019, as a visitor); Norsk Luftfartsmuseum, Bodø (16 July 2018, with staff), Protect and Survive: Britain’s Cold War Revealed exhibition at the National Archives, Kew (18 and 19 September 2019, as a visitor), The Museum of Military History, Dresden (17 August 2019, as a visitor).

2. We are aware that this selection is necessarily partial. Elements of Cold War museology ripe for future analyses include protest movements (for example at Glasgow Museums or the Peace Museum in Bradford), nuclear power (see Boyle Citation2019; Sastre‐Juan and Valentines‐Álvarez Citation2019), or art, design and culture as seen in the exhibitions Cold War Modern: Design 1945–70 at the V&A in 2008–9 (Crowley and Pavitt Citation2008); War of Nerves, a collaboration between the Wende Museum and Wellcome Collection (Birchall and Segal Citation2018); and the Bruce Museum’s Hot Art in a Cold War (2018).

3. The Museum of Military History, Dresden field visit, 17 August 2019.

4. AlliiertenMuseum field visit, 7 November 2018.

5. Protect and Survive: Britain’s Cold War Revealed exhibition at the National Archives, Kew, field visit 18 and 19 September 2019. The curator’s tour of the exhibition can be watched at https://youtu.be/UoiMMtLZgPQ (accessed 21 September 2020).

6. RAF Museums Cosford field visit, 18 January 2018.

7. Imperial War Museums Duxford field visit, 7 May 2019.

References

- Allied Museum. 2020a. “Historic Site.” Accessed 15 June 2021. www.alliiertenmuseum.de/en/exhibitions/historic-site.html.

- Allied Museum. 2020b. “The History of the Allied Museum.” Accessed 15 June 2021. www.alliiertenmuseum.de/en/about-us/timeline.html.

- Alpers, S. 1991. “The Museum as a Way of Seeing.” In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, edited by S. D. Lavine and I. Karp, 25–32. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Apsel, J. 2016. Introducing Peace Museums. London: Routledge.

- Arnold-de Simine, S. 2013. Mediating Memory in the Museum. Trauma, Empathy, Nostalgia. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Audoin-Rouzeau, S. 2009. Les armes et la chair. Trois objets de mort en 14-18. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Auslander, L. 2005a. “Coming Home? Jews in Postwar Paris.” Journal of Contemporary History 40 (2): 237–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009405051552.

- Auslander, L. 2005b. “Beyond Words.” The American Historical Review 110 (4): 1015–1045. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.110.4.1015.

- Axelsson, T. Gustafsson, H. Karlsson and M. Persson. 2018. “Command Centre Bjorn: The Conflict Heritage of a Swedish Cold War Military Installation.” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 13 (1): 59–76. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2018.1536407.

- Beck, J., and R. Bishop. 2016. “Introduction: The Long Cold War.” In Cold War Legacies. Systems, Theories, Aesthetics, edited by J. Beck and R. Bishop, 1–32. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Benjamin, W. 1969 (1935. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by H. Arendt, 1–26. New York: Schocken.

- Bennett, H.,Finch, A. Mamolea and D. Morgan-Owen. 2019. “Studying Mars and Clio: Or How Not to Write about the Ethics of Military Conduct and Military History”. History Workshop Journal 88: 274–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbz034.

- Bennett, L. 2013. “Who Goes There? Accounting for Gender in the Urge to Explore Abandoned Military Bunkers.” Gender, Place & Culture 20 (5): 630–646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2012.701197.

- Bennett, L. 2017. In the Ruins of the Cold War Bunker: Affect, Materiality and Meaning-Making. London and Lanham, MD: Rowan & Littlefield.

- Bennett, T. 2017 (1988). “The Exhibitionary Complex.” In Idem, Museums, Power, Knowledge. Selected Essays, 23–51. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Berger, S., and N. LaPorte. 2010. Friendly Enemies. Britain and the GDR, 1949-1990. Oxford and New York: Berghahn.

- Birchall, D., and J. Segal. 2018. War of Nerves. Psychological Landscapes of the Cold War. Culver City CA: Wende Museum of the Cold War.

- Boyle, A. 2019. “‘Banishing the Atom Pile Bogy’: Exhibiting Britain’s First Nuclear Reactor.” Centaurus 61 (1–2): 14–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1600-0498.12220.

- Brusius, M., and K. Singh, eds. 2017. Museum Storage and Meaning: Tales from the Crypt. London: Routledge.

- Buchczyk, M. 2018. “Ethnographic Objects on the Cold War Front: The Tangled History of a London Museum Collection.” Museum Anthropology 41 (2): 159–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12185.

- Cameron, D. F. 1971. “The Museum, a Temple or the Forum.” Curator 14 (1): 11–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1971.tb00416.x.

- Cento Bull, A., H. L. Hansen, W. Kansteiner and N. Parish 2019. “War Museums as Agonistic Spaces: Possibilities, Opportunities and Constraints.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (6): 611–625. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1530288.

- Cercel, C. 2018. “The Military History Museum in Dresden. Between Forum and Temple.” History & Memory 30 (1): 3–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/histmemo.30.1.02.

- Chamberlin, P. T. 2018. The Cold War’s Killing Fields: Rethinking the Long Peace. New York: Harper.

- Clausewitz, C. V. 1918 (1832). On War, trans. J. J. Graham. New and Revised edition with introduction and notes by F. N. Maude, 3 vols. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & . Accessed 15 June 2021. https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/clausewitz-war-as-politics-by-other-means.

- Cocroft, W. D. 2007. “Defining the National Archaeological Character of Cold War Remains.” In A Fearsome Heritage. Diverse Legacies of the Cold War, edited by J. Schofield and W. D. Cocroft, 107–127. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Cocroft, W. D. 2014. “Cold War.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by C. Smith, 1545–1554. New York: Springer.

- Cocroft, W. D., and R. J. C. Thomas, eds. 2003. Cold War: Building for Nuclear Confrontation 1946–1989. Swindon: Historic England.

- Cocroft, W. D., C. F. Ostermann and A. Etges 2017. “Protect and Survive. Preserving and Presenting the Built Cold War Heritage.” In The Cold War. Historiography, Memory, Representation, edited by K. H. Jarausch, et al., 215–238. Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter.

- Cowling, D. 2019. “Anglo-German Relations after 1945.” Journal of Contemporary History 54 (1): 82–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009417697808.

- Crane, S. 1997. “Memory, Distortion, and History in the Museum.” History and Theory 36 (4): 44–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0018-2656.00030.

- Crowley, D., and J. Pavitt, eds. 2008. Cold War Modern: Design 1945–1970. London: V&A.

- Danylow, J., and A. Etges. 2013. “A Hot Debate over the Cold War: The Plan for a ‘Cold War Center’ at Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin.” In Museums in a Global Context: National Identity, International Understanding, edited by J. W. Dickey, S. El Azhar, and C. M. Lewis, 144–161. Washington, DC: AAM Press.

- Daum, A. 2008. Kennedy in Berlin. Politics and Culture in the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Dechow, D. R., and A. Leahy. 2006. “Not Just the Hangars of World War II: American Aviation Museums and the Role of Memorial.” Curator: The Museum Journal 49 (4): 419–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2006.tb00234.x.

- Dülffer, J. 2008. “Cold War History in Germany.” Cold War History 8 (2): 135–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14682740802018652.

- Echternkamp, J., and S. Jaeger, eds. 2019. Views of Violence: Representing the Second World in German and European Museums and Memorials. New York and Oxford: Berghahn.

- Edgerton, D. ed. 2013. England and the Aeroplane: Militarism, Modernity and Machines. Revised. London: Penguin.

- Edgerton, D. 2018. The Rise and Fall of the British Nation: A Twentieth-Century History. London: Penguin.

- Eugster, D., and S. Marti, eds. 2015. Das Imaginäre des Kalten Krieges. Beiträge zu einer Kulturgeschichte des Ost-West-Konfliktes in Europa. Essen: Klartext.

- Farbøl, R. 2015. “Commemoration of a Cold War: The Politics of History and Heritage at Cold War Memory Sites in Denmark.” Cold War History 15 (4): 471–490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2015.1028532.

- Fiorato, V. 2014. “Greenham Common: The Conservation and Management of a Cold War Archetype.” In A Fearsome Heritage: Diverse Legacies of the Cold War, edited by J. Schofield and W. Cocroft, 129–154. London: Routledge.

- Gaddis, J. 1997. We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Geyer, M. 2020. “The Prague Cookbook of Ruth Bratu, Or: How a Historian Came to Feel the Past.” Central European History 53 (1): 2–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938919001018.

- Geyer, M., and K. H. Jarausch. 2003. Shattered Past: Reconstructing German Histories. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Grant, M. 2011. “‘Civil Defence Gives Meaning to Your Leisure’: Citizenship, Participation, and Cultural Change in Cold War Recruitment Propaganda, 1949–54.” Twentieth Century British History 22 (1): 52–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwq040.

- Grant, M., and B. Ziemann, eds. 2016. Understanding the Imaginary War: Culture, Thought and Nuclear Conflict, 1945–1990. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Greiner, B., T. B. Müller and K. Voß., eds. 2013. Erbe des Kalten Krieges. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition.

- Hacker, B. C., and M. Vining. 2013. “Military Museums and Social History.” In Does War Belong in Museums? the Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, edited by W. Muchitsch, 41–59. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Hacker, B. C. 2014. “Reflections on Nuclear Submarines in the Cold War: Putting Military Technology in Context for a History Museum Exhibit.” In A Fearsome Heritage: Diverse Legacies of the Cold War, edited by J. Schofield and W. Cocroft, 211–229. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast.

- Harrison, H. M. 2019. After the Wall: Memory and the Making of the New Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hennessy, P. 2010. The Secret State. Preparing for the Worst, 1945-2010. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Hogg, J. 2016. British Nuclear Culture: Official and Unofficial Narratives in the Long 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hong, Y.-S. 2015. Cold War Germany, the Third World, and the Global Humanitarian Regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Horn, E. 2007. Der geheime Krieg. Verrat, Spionage und moderne Fiktion. Frankfurt/Main: Fischer.

- Horn, E. 2013. The Secret War: Treason, Espionage, and Modern Fiction. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Hüppauf, B. 1993. “Experiences of Modern Warfare and the Crisis of Representation.” New German Critique 59: 41–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/488223.

- Huxford, G. 2018. The Korean War in Britain: Citizenship, Selfhood and Forgetting. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Jampol, J., ed. 2014. Beyond the Wall: Art and Artifacts from the GDR. Cologne: Taschen.

- Komska, Y. 2015. The Icon Curtain. The Cold War’s Quiet Border. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Kühne, T., and B. Ziemann. 2000. “Militärgeschichte in der Erweiterung. Konjunkturen. Interpretationen, Konzepte.” In Was ist Militärgeschichte?, edited by T. Kühne and B. Ziemann, 10–46. Paderborn: Schöningh.

- Lisle, D. 2006. “Sublime Lessons: Education and Ambivalence in War Exhibitions.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 34 (3): 841–862. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298060340031701.

- Logan, W., and K. Reeves, eds. 2008. Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’. London: Routledge.

- Lowe, D., and T. Joel. 2013. Remembering the Cold War: Global Contest and National Stories. London: Routledge.

- Lüthi, L. 2020. Cold Wars: Asia, the Middle East, Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Macdonald, S. 2009. Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi past in Nuremberg and Beyond. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Macdonald, S. 2013. Memorylands. Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. Abingdon: Routledge.

- MacGregor, N. 2010. A History of the World in 100 Objects. London: Allen Lane.

- Malvern, S. 2000. “War, Memory and Museums: Art and Artefact in the Imperial War Museum.” History Workshop Journal 49 (1): 145–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/2000.49.177.

- Mason, R. 2013. “National Museums, Globalization, and Postnationalism. Imagining a Cosmopolitan Museology.” Museum Worlds: Advances in Research 1 (1): 40–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2013.010104.

- Militärhistorisches Museum. 2019. MHM Berlin-Gatow Airfield. Accessed 30 May 2019. www.mhmbw.de/standorte-eng/mhmgatow-eng.

- Moser, S. 2010. “The Devil is in the Detail: Museum Displays and the Creation of Knowledge.” Museum Anthropology 33 (1): 22–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01072.x.

- Muchitsch, W., ed. 2013. Does War Belong in Museums? the Representation of Violence in Exhibitions. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- National Archives. 2019. Protect and Survive. Britain’s Cold War Revealed. London: National Archives.

- Nehring, H. 2012. “What Was the Cold War?” The English Historical Review 127 (527): 920–949. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ces176.

- Nehring, H. 2013. Politics of Security: British and West German Protest Movements and the Early Cold War 1945–1970. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nicholls, A. J. 2001. Fifty Years of Anglo-German Relations. The 2000 Bithell Memorial Lecture. London: University of London School of Advanced Study.

- Niven, B. 2001. Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich. London: Routledge

- Pedersen, S. 2010. “Money, Space and Time: Reflections on Graduate Education.” Twentieth Century British History 21 (3): 382–396.

- Pieken, G. 2013. “Contents and Space: New Concept and New Building of the Militärhistorisches Museum of the Bundeswehr.” In Does War Belong in Museums? the Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, edited by W. Muchitsch, 63–82. Bielefeld: transcript.

- RAF Museum. 2020a. “The National Cold War Exhibition.” Accessed 18 June 2021. www.rafmuseum.org.uk/cosford/things-to-see-and-do/hangars/cold-war .aspx.

- RAF Museum. 2020b. “On Display.” Accessed 18 June 2021. www.rafmuseum.org.uk/cosford/things-to-see-and-do/on-display.aspx.

- RAF Museum. 2020c. “VW Beetle.” Accessed 18 June 2021. www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/collections/volkswagen-beetle.

- RAF Museum. 2020d. “Opel Senator 2.8i.” Accessed 18 June 2021. www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/collections/opel-senator-2-8i.

- RAF Museum. 2020e. “History.” Accessed 18 June 2021. www.rafmuseum.org.uk/cosford/schools-and-colleges/history.aspx.

- Reynolds, D. K. H. Jarausch, C. F. Ostermann and A. Etges. 2017. “Probing Cold War Narratives since 1945: The Case of Western Europe.” In The Cold War. Historiography, Memory, Representation, edited by K. H. Jarausch, et al., 67–82. Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter.

- Romero, F. 2014. “Cold War Historiography at the Crossroads.” Cold War History 14 (4): 685–703. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2014.950249.

- Rüger, J. 2011. “Revisiting the Anglo-German Antagonism.” Journal of Modern History 83 (3): 579–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/660841.

- Sastre‐Juan, J., and J. Valentines‐Álvarez. 2019. “Fun and Fear: The Banalization of Nuclear Technologies through Display.” Centaurus 61 (1–2): 2–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1600-0498.12223.

- Schofield, J., and W. D. Cocroft, eds. 2007. A Fearsome Heritage: Diverse Legacies of the Cold War. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast.

- Schofield, J., W. D. Cocroft, and M. Dobronovskaya. 2021. “Cold War: A Transnational Approach to a Global Heritage.” Post-Medieval Archaeology 55 (1): 39–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00794236.2021.1896211.