ABSTRACT

As part of the culturally focused direction of travel surrounding Gothenburg’s fourth centenary, several departments of the municipality have collaborated to produce a virtual model of Gothenburg as it was in the seventeenth century, first presented to the public in 2017. This case study analyses the city’s approaches to displaying and vitalising the model, the role of the built environment as a cultural backdrop, and the efficacy of cultural transmission within this digital context. Principally, this analysis offers a critical response to the depiction of the city’s cultural heritage, but it also aims to examine the wider role of digital visualisation in contemporary heritage discourse. Characterising the realisation of the model’s current iteration as a stepping stone for further development, potential points of departure for creativity and meaning-making within the model itself and in a broader context are made to inform future heritage practices in the city.

Introduction

As both an urban space and place, the city has long been at the nexus of heritage and how it is communicated through art, be it the image, moving picture, music, or literature. However, if it is taken that ‘heritage is not a fixed, unchanging thing, but something that is constructed, created, constituted and reflected by discourses’ (Waterton Citation2010, 4), then it is equally important to retain sight of the evolving mechanisms for accessing and disseminating heritage information relating to such spaces. In order to be effective, ‘a dialectic relationship between society and discourse’ must be struck (2010, 7), requiring museums and heritage agencies to keep abreast of new means of delivering heritage. Digitality, representing one of several advances in cultural transmission, is not a new development. The ‘combined data and knowledge revolution’, as promoted by the parallel ‘computing and digital revolution in modern media and communication’ (Kristiansen Citation2014, 23), has long since spilled over into archaeological and historical studies and should be considered both interdisciplinary and global. As data is increasingly born digitally within the fields that feed museum curation, it is becoming ever more important that the heritage sector, whether professional or public, keep up with this direction of travel. As momentum is built along this vector and the various facets of digitality permeate society, contemporary audiences are increasingly expectant of communication methods that promote intellection in a format that is compatible with their daily routines (Petersson Citation2018, 83).

Given the current extent and prevalence of heritage visualisation across numerous sectors, including planning, management, marketing, entertainment, education, accessibility, and heritage preservation (Guttentag Citation2010, 637), it is not unusual for a city to present a version of their own urban heritage in digital form; many urban centres are attempting to express their identity and heritage through the creation of a digital surrogate, which refers to the digital reproduction of a material object or place, (Conway Citation2014; Rabinowitz Citation2015) or historic visualisation. The Rome Reborn project (Flyover Zone Citation2021) and Visualizing Venice (Citation2021) are frequently cited due to their extent and renown, but lesser-known models of similar origin in methodology, geography, and purpose are equally accessible; examples include the early modern explorations of Amsterdam (City of Amsterdam Citation2021) and Oslo (Tidvis Citation2020).

Analyses of virtual heritage models often focus heavily on their development and technical aspects; however, in this instance, through post-hoc analysis, this paper aims to summarise the effectiveness of historical visualisations in meeting a city’s cultural, social, and historical demands. Comparable aspects can be drawn between similar projects, thereby signposting further opportunities to develop and align such visualisations alongside the malleability of heritage processes. The rationales behind the choices in public technologies and narratives, as well as representativity and the politics of aesthetic and experiential decisions, will be examined in order to communicate the criticality and reflexive uses of digitality in the current milieu of the city. This includes an exploration of the authenticity of spatial representation (i.e. the conscious choice to blend fact and fiction for the benefit of common understanding); the power structures of presentation both locationally and institutionally; usership, the politics of inclusion, as well as presence and interactivity; and finally, a discussion outlining the potential models that this format can realise with further creative input. With the aim of providing a general commentary on the process of creating, presenting, and communicating heritage through digital surrogacy, this case study presents the ways in which multiple publics engage with the heritage visualisation of the city of Gothenburg.

Digitally encountering the seventeenth-century city of Gothenburg

2021 marks the fourth centenary of the city of Gothenburg (now delayed until 2023) has placed a great deal of emphasis and pressure on its cultural and historical agencies to convey meaningful public heritages in a modern vein. Since the last centenary celebration of 1923 (similarly delayed by two years because of the aftermath of the first world war), which placed significant emphasis on crafts in the city and surrounding areas (Thorén Citation2011, 277) rather than the city itself, it is evident that not only have the structures of Gothenburg’s demographics and built environment changed a great deal, so too have the socio-political contexts that they exist within. Therefore, within the epistemological context of heritage visualisation, a digital surrogate of Gothenburg as it was in the seventeenth century has been conceptualised by the city’s municipality.

Development

This paper’s focus is not on the techniques used to create the model; nevertheless, it is prudent to include a brief description of the model’s development. It could be argued that it has a strong impact on both the underlying decision-making processes and its effectiveness in its various deployments. Conceived by Gothenburg & Co (the city’s tourism, culture, and events board), the model represents the cultural intersect between the City Planning Office (Stadbyggnadskontoret), the Museum of Gothenburg, and the Visual Arena at Lindholmen Science Park. Much of the visualisation itself is concerned with the physical form of the city based on available archival material – primarily cartography in the form of architectural projections. In chronological terms, the depiction is presented to the public as illustrating the city as it was in 1698. It encompasses the entirety of the city within the inner fortifications, representing a space of approximately 70 hectares () – the outer fortifications are demarcated in the visualisation but the urban spaces within them are not included. There are additional aspects of city life depicted in various ways; these include human figures, foliage, water surfaces, and modes of transport.

Figure 1. A promotional image of the digital city (pictures by Göteborgs Stad/©Stadsbyggnadskontoret).

Figure 2. A screenshot of the central square as it appears in the virtual reality application (pictures by Göteborgs Stad/©Stadsbyggnadskontoret).

Its construction entailed procedurally modelling the more conspicuous of the city’s edifices with Autodesk Maya and embedding them within a more generic 3D urban environment created with ESRI CityEngine, largely due to a lack of preserved buildings from the period. The cinematic aspects of the historic urban environment were then developed and rendered using the Unreal Engine. This phase was largely the responsibility of Stadsbyggnadskontoret. Much of the city space was produced according to a standardised design. While this is unlikely to be accurately representative of Gothenburg as it appeared at the time, it does in some way mirror the known building techniques from the period. Despite the lack of preservation in the city, there is ample evidence for prefabricated log timber buildings that were produced north of the city and transported along the Göta river (Nilsen Citation2020, 84), particularly in light of the need for large-scale construction and replacement in response to fire or enemy attack.

The parallels between the standardised formats of the digital surrogate and the historic city are likely consequential more than a conscious choice, at least as far as is made evident to the user. This is consistent with the observation that cultural heritage professionals often provide content for digital applications but are seldom heavily involved in the design (Maye et al. Citation2017, 222). The Museum of Gothenburg largely operated in an advisory role for historical accuracy rather than a more creative capacity. Digitised versions of the architectural and cartographic plans of the city were requisitioned by the Museum from Krigsarkivet. Alongside the evidence produced from archaeological interventions, these projections provided the necessary source material for the visualisation. This substantiates the notion that there is a sparsity of academic historical input in such visualisations. The use of ‘off-the-shelf’ or well-established narratives is a markedly tendentious preference in heritage applications, especially when put together by local authorities or organisations where the focus is economically driven or regenerative (Poole Citation2017, 301). In this case, the visualisation represents the status quo in terms of official narratives and is thus not used as a research tool. Arrigoni, Schofield, and Pisanty (Citation2019, 2) note that digitally focused collaborations are either ‘driven by pre-determined research questions or requirements’ or emphasise ‘an experimentation and engagement with audiences, which takes precedence over particular outcomes’. Arguably, the Gothenburg approach falls somewhere between the two: it is caught between the fourth centenary as a cultural driving force but is simultaneously focused on new applications of digitality in the city’s heritage sector.

Initially marketable events with greater visibility and cultural capital heralded the project’s arrival into the public sphere before finding a more stable host at the Museum of Gothenburg. At present, this functions as the most prominent and stable mode of displaying the model. Virtual reality (VR) applications favouring head-mounted displays are the primary delivery format. This includes temporary displays utilising cell phone VR headsets, such as those used in the installation at the 2018 Gothenburg leg of the Volvo Ocean Race (Lagerlöf Citation2019) and the Gothenburg Culture Festival (Göteborgs Stadsmuseum Citation2019). There are also more permanent displays such as the Xbox One connection to an Oculus Rift platform in the entrance hall to the Museum as well as an augmented reality (AR) installation in the Tourist Information centre at Kungsportsplatsen. A video montage of the model has also been included as the centrepiece of the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition, utilising fly-by views of the structures that are most prominent in the digital city’s landscape. This can be seen on the City of Gothenburg’s YouTube channelFootnote1 and extracts have even made their way onto an episode of Sveriges Television’s (SVT) ‘Allt för Sverige’ (Citation2019), a reality TV show where American contestants of Swedish origin return to Sweden to rediscover their ancestral ties.

Analysis

Criteria for analysis

Largely qualitative in nature, much of the focus in this analysis will be on the three incumbent displays of the model: the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition, the VR installation in the Museum entrance hall, and the Tourist Information centre at Kungsportsplatsen. However, there are also significant observations to be made of the temporary installations and the ways in which the model was depicted. To reduce the subjective nature of this analysis and introduce a level of thoroughness, the experiences facilitated by the model on display in various modes in Gothenburg will be measured against aspects of both the London Charter (Denard Citation2012) and the Seville Principles (International Forum of Virtual Archaeology Citation2011). The London Charter, considered to be particularly important (Pujol and Champion Citation2012, 85), took the first steps in establishing guidelines for the application of scholarly rigour to the products of 3D visualisation so that they might make valuable contributions on a wider scale beyond virtual heritage studies. The Seville Principles, in turn, served as a further set of guidelines to improving the implementation of the London Charter but with greater attention to the specific needs of archaeological heritage (Carrillo Gea et al. Citation2013, 208). Due to their relevance to the field, reference to these documents is an appropriate measure.

Urban spatial representation

While they may perhaps be the most unequivocal starting points, historical chorography and cartography are not in themselves unproblematic. As city plans from numerous years were used in the production of this project, minor historical discrepancies arose. For example, Skansen Kronan redoubt is presented in the visualisation as complete, although the roof was not finished until after 1700 (Statens Fastighetsverk Citation2021). Instead of merely pointing out that this is wrong, we should consider how digital surrogates are negotiated elsewhere. Westin and Hedlund use a high-profile example in the form of Rome as it appears in Assassin’s Creed 2: Brotherhood. While clearly primarily a component of the entertainment industry, video games operate on multiple levels that include a degree of interaction with virtual heritage using visualisation as an ally to the process of storytelling (Champion Citation2015, 17). The Rome of Assassin’s Creed is not a snapshot of a specific moment in time but an assemblage of archaeological fact and popular expectation, producing a Rome that is instantly recognisable. This phenomenon becomes representative of what has been coined a ‘polychronia’, a representation of features or artefacts from multiple points in time with the goal of achieving common understanding (Westin and Hedlund Citation2016, 16).

By the 1621 establishment of Gothenburg, the ideal city was on its way to becoming a symbol of early modern engineering (Wennberg Citation2018, 19). Gothenburg was built on the principle of maintaining effective control and defence. As such, many of the city plans’ focal points allude solely towards important defensible assets. Fidelity to the source material and real-world constraints therefore depicts a city isolated within the model’s virtual landscape. There are exceptions for the two redoubts, namely, Kronan and Lejonet as well as the Älvsborgs fortress, but the surrounding representation of the historic environment is necessarily stripped of its anthropological characteristics.

Gothenburg’s higher ground is a good example of this. Early plans ahead of the city charter (1619/20) indicate that a castle of sorts should stand on Stora Otterhällan and a church is shown on Kvarnberget (Wennberg Citation2018, 25). Whilst this was never realised, by the time the fortification of the city was under the guidance of Eric Dahlbergh (1684–1719), the city had taken ownership of the high ground. It is known that a mill had once stood there); however, in peacetime, the city allowed those that could not buy and own a plot to build there until the land was required for defending the city. Renting plots next to the powder stores was understandably cheap. These spaces were not governed by the grid system demarcating the rest of the city, meaning there was a sense of impermanence to the housing and street plans on these escarpments (Öbrink, Williams, and Nilsen Citation2018, 291). The nature of the dwellings was not recorded in the plans and so is subsequently not reflected in the model, thereby obscuring the existence of the lower classes of Gothenburg society.

Lowenthal (Citation2015, 498) argued that in ‘[P]rofessing to correct precursors’ prejudices and to recover pre-existing truths, we fail to see how much of today we put in the past’, resulting in a misrepresented past – idealised as its supposed ‘best’ out of shame or pride. In the first century of its existence, space in Gothenburg was divided economically rather than by nationality: the wealthy clustered together. Whilst it was recognised that the city required their labour contributions, there remained an evident disdain for the lower classes. Despite engaging in a symbiotic relationship with the residential district of Majorna, it was not until 1868 that it became part of Gothenburg because the city authorities had been reluctant to include such a large area of poor workers and sailors (Hallén Citation2017, 207). Even Masthugget and Haga, which were part of the city from the outset despite being located outside the city gates and were only associated with the working classes in later centuries, were represented as geographically and socially peripheral (Nilsen Citation2020, 180). They are depicted as such in contemporary cartography and this is reproduced within the model. However, by pointedly drawing attention to such aspects within the model, reincluding undesirable or ignoble details of the city’s past can be encouraged.

Whether deliberately or not, the architects of the digital city echo the political choices of their forebears. Where these methodologies for visualising historic cities are followed, a greater sense of awareness is required, and the decisions taken in the process of creation ought not to mask the exclusionary politics of the past. Under ‘the methodological rationale of a visualisation’ (Denard Citation2012, 66), where decisions have been made for aesthetic reasons, responsibility for the nature of the content should also be taken. It is often the case that political choices are made in the modelling process, yet they are seldom recognised as such.

Early modern heterotopia

As a literary-geographical analogy, Franco Moretti makes the point that ‘geography is not an inert container, it is not a box where cultural history “happens”, but an active force’ (Moretti Citation1998, 3). Mapping is a connection to space made visible, but it is not the conclusion of geographical work (Citation1998, 7). The same can be said of city visualisation: modelling a city is not the conclusion but the beginning. A city visualisation abides by specific configurations, but questions remain as to what narrative it relates concerning the lives of the people that inhabited the space. This notion of narrative can be expressed in three ways according to Dunn (Citation2019, 98): they can facilitate change, document personal experience, or assert power. Using the analogy of Plato’s Cave, Dunn goes on to argue that spatial media conditions the identities of nations, regions, communities, and individuals in spaces we have never seen and can never see (Citation2019, 101). In this sense, there is a need to be more explicit about what space represents in the context of virtual heritage. Michel Foucault conceptualises such spaces as ‘heterotopias’. Whereas utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces, operating as analogies to real spaces and presenting society in perfect form, some places exist simultaneously as ‘mythical and real contestations of space’ (Foucault and Miskowiec Citation1986, 24). By visualising maps and plans in 3D, we recognise Gothenburg, in this instance, as both a familiar city and as a digital object that exists in reality; at the same time, it is unreal as it has to pass through the ‘utopian virtual point’ of the past so as to be palatable for us to see it.

In relation to archaeo-historical visualisation, we attempt to translate the material of the graphosphere along with the material of reality into the digital hypersphere (Vandenberghe Citation2016, 38). However, reality holds too many variants for digital technology to account for, and mimesis is thus not possible. The relationship that exists between space, the built environment, and the society that would have inhabited it is not made explicit. Whilst there are shared visual similarities and characteristics between a historical city and its digital surrogate, the connection is largely superficial and unsentimental in experiential terms. Therefore, the goal should not be to just reproduce the map in a newer, more novel format. The goal should go deeper than data and juxtaposing materials as a means of authenticity and should strive for the emotional rather than the empirical.

Part past, part fiction

In The Archaeology of Time Travel: Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century Cornelius Holtorf defines time travel (within the capacity of current technological limitations) as an ‘embodied experience and social practice in the present that brings to life a past or future reality … to experience the presence of another time period’ (Holtorf Citation2017, 1), clarifying that ‘historical re-enactment and VR cannot bring the past back to life as it really was’ (2017, 14). This is a truism as a matter of course; however, the marketing of virtual heritage puts forward the idea that the user will find the experience comparable to visiting a realised and accessible past.

The London Charter and the later Seville Principles are explicit in advocating for digital heritage visualisations to be seen to be ‘at least as intellectually and technically rigorous as longer established cultural heritage research and communication methods’ (Denard Citation2012, 59). To achieve this, scientific transparency, historical rigour, and authenticity must be testable. As the latter principles state, ‘it should always be possible to distinguish what is real, genuine or authentic from what is not’; this is a standard that should be achievable for both a professional and a public audience (International Forum of Virtual Archaeology Citation2011). Due to the gaps in archaeo-historic knowledge regarding Gothenburg’s architectural morphology and the generic visualisation methodology to compensate for this, the necessary transparency has not hitherto been clearly achieved.

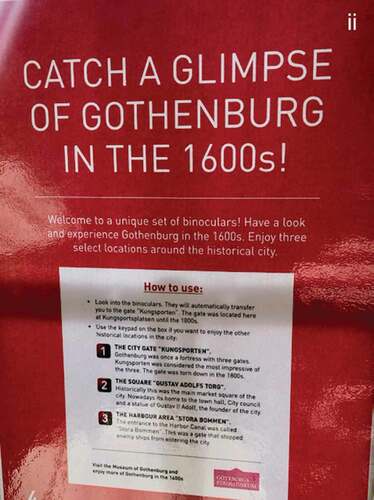

In such a context, it is inevitably difficult to separate the real from the speculative but there are nevertheless ways of counterbalancing this through effective presentation. The primary issue is the sparsity of preparatory information available to the prospective virtual user to mitigate the sense of verisimilitude. Semantically, the language used in the Gothenburg case (), namely, ‘catch a glimpse of … ’, ‘showing … ’, and ‘experience in Gothenburg’, indicates a degree of certainty. They leave no room for questions or interpretations but demand to be recognised as truth. By employing these semantics and incorporating the material into an assemblage of public narratives (Latour and Woolgar Citation1986, 106), historical reference is lost through the media performance of visual representation. Uncertainties and negotiations are forgotten and the representation is seen as fact (Westin Citation2014, 139).

Figure 3. The textual provision for preparatory information i) alongside the film in the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition, ii) at the Kungsportsplatsen tourist information centre, and iii) at the Museum’s VR station (photos by the author).

If one were to delve deeper and follow the audio description complementing the film in the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition, the boundaries between what is real and what is not are interwoven within the narrative, further blurring the lines between certainty and uncertainty. In the introduction, we are told:

This film is a computer-animated journey through seventeenth-century Gothenburg. The 3D motion pictures create a feeling both real and unreal at the same time. Some surfaces and objects are so detailed that they feel real, such as the water surface, the sky, the flowers, and trees. Others are only hinted at, such as the people, who appear as grey, still-standing paper silhouettes. They are slightly reminiscent of a computer game. (Göteborgs Stadsmuseum Citation2017)Footnote2

Moderation of the textual provisions would help temper the public’s expectations. Rather than addressing the areas of spatial uncertainty, the text’s focus is on the lack of human characters. This relates to both the user and the content. It is assumed that the model is immersive because of the VR application; however, in reality, there is a certain distance between the process of embodiment and that of movement through the digital space. Mediated by the console controller and the Unreal Engine, the user moves an avatar of themselves via a first-person camera view. This distance is magnified by the speed at which the camera moves through the space. Going faster and smoother than a person on foot might, this was recently likened by a student of mine to the experience of riding an e-scooter through the seventeenth century. A similar contemporary analogy can be made for the VR perspective on display at the Culture Festival. Here, via a mobile head-mounted display, the visualisation follows a prescribed path over the city; rather than the angelic perspective we might once have imagined of Rome in all its antiquarian glory, however, we are treated to a dispassionate and impartial drone’s eye view of the early modern city.

Presence

In the User Manual for his book Production of Presence, Gumbrecht (Citation2004) states that presence, as he utilises the term, refers mainly to spatial rather than temporal phenomena. However, when the goal is to explore space in time – as is the case when exploring virtual heritage in immersive media – then the question of presence requires deeper consideration in light of the inherent anachronisms that arise. Separating time and space as a scientific convention serves little purpose in this instance; instead, the focus ought to be on pursuing an understanding of organised space. This requires a ‘technically efficient environment, establishing a framework for the social system, and providing a starting point for the work of ordering the surrounding universe’ (Leroi-Gourhan Citation1993, 322). Presence is the key to the realisation of the heritage aspect in visualising a city so as to ‘attempt to convey not just the appearance but also the meaning and significance of cultural artefacts and the associated social agency that designed and used them’ (Champion Citation2019, 341). Cultural presence is established through what Champion (Citation2009) describes as hermeneutic richness, ‘the depth of affordance that a virtual environment gives to the interpretation of a natively residing culture in that virtual environment’. Crucially, this is achievable even in instances where digital architects ‘do not have the technology to simulate believable and authentic NPCs (Non-Playing Characters), and avatars as cultural agents’ (Champion Citation2009, 41).

In creating a digital surrogate, the ‘paper silhouettes’ approach adopted by the model operates as a means of communicating scale within the model but not as a means of creating presence. Whilst they may be considered as elements that enrich the model, the function of such placeholders often primarily appears architectonic in character (Westin Citation2014, 144). The cues for activity in the Gothenburg example are taken primarily from the street furniture of early modern urbanity. Semiologically, artefacts of activity are in abundance within the digital space – albeit generically sourced – and are placed to prompt the user; ships in the canal and cargo-laden wharves indicate the city’s mercantile function, canons and martial display signal the city’s military clout, the hanging laundry and smoking chimneys indicate domestic activity, grinding wheels indicate blade sharpening, and yards full of hop plants indicate brewing practices. These elements alone, however, are not enough to sufficiently capture the meaning, social agency, or character of a city.

A significant issue is the mediation of the visual representation in becoming a material force. The efficacy of the cues relies upon the cognitive ability to relate ocular stimuli to prior knowledge through the distinct nature of cultural identifiers. If imposition and effect are developed through the techniques that produce the image and the network through which they are perceived (Debray and Rauth Citation1995, 530), then without this knowledge, the efficacy of the symbology is greatly reduced. The use of generic objects further dissipates cultural distinction. As we do not meet the merchants, sailors, soldiers, grinders, and brewers, nor encounter any tangible demonstration of domestic living, the meaning and scale of these activities are lost. Furthermore, there is no indication of the division of labour, family structures, gendered perspectives, or any sense of social and economic diversity or alterity. This is information that we have access to; alternative historical experiences are well known and are in other projects used as a key narrative thread in the Museum’s approach to the city’s formation.

In instances when this knowledge is not available before or during the visualisation experience, the capacity for a viewer to recognise the local processes that characterise Gothenburg is limited. Research suggests that background knowledge, experience, and personal conceptualisation aid the perception of digital artefacts (Galeazzi, Franco, and Matthews Citation2015, 479–81). On a city scale, however, historical processes, social relationships, and causal agents are fundamental. Resultantly, the lack of any significant relation to the past magnifies the inherent anachronism of virtual time travel; rather than embracing this anachronism as a method of understanding the past and present (Petersson Citation2017), the model’s human representation amplifies historical lacunae rather than bringing humanity into the visualisation.

Without human imposition, Scandinavian historicity (Orrman Citation2016, 161) no longer impacts Gothenburg. The model becomes a pristine space free from the consequences of the recurrent wars that characterised the kingdom of Sweden’s international relations up until the 1720s; it is a city seemingly unafflicted by widespread crop failures and famines, untouched by epidemics, and unscathed by fire. We encounter a city standing in the vacuum of a culturally empty landscape, bathed in heavenly morning sunlight. Not unlike the way the sky is employed in the visualisation of Rome – with the sun at its zenith and the tranquillity and stillness of the unfathomable blue mirroring ‘the calm centre of human culture’ (Westin Citation2014, 146) – this resplendent dawn both hides urban inaccuracies and heralds the arrival of the perceived ‘golden age’ of Gothenburg. Blurring, distorting, or highlighting spaces of doubt in archaeo-historic visualisation has an accepted place when precisely deployed, but by using aesthetic methods such as avatar movement and sunlight, which are consistent throughout the models, the boundaries of uncertainty become equally unclear. Digital surrogates become unchanging, non-negotiable entities swept up in a narrative that withstands exploration or revisitation.

Audience matters

As a developing digital product, the model has naturally been subject to multiple iterations in different settings as a means of finding an audience. To some extent, the question of who it is intended for and what it is supposed to do remains unanswered. The practice of spreading it out across multiple platforms is not inherently bad; for example, hosting the model on a stable web platform as well as in an augmented reality application can function as long as the goal and audience remain coherent. Multiplicity may be contested against point two of the Seville Principle (International Forum of Virtual Archaeology Citation2011), which is to make the ultimate purpose or goal of the work completely clear. As a digital object, models can easily be mobilised, but this does not necessarily mean that the transmission and trajectory of heritage information will remain constant with each form of delivery. As audiences broaden, the varying degrees of participation we go through to experience the model can often be overlooked.

In Gothenburg, the range of variation can be encapsulated fairly well. Although it forms part of a more exceptional deployment rather than the norm, the Volvo Ocean Race has a role in attracting visitors and promoting the city as a destination with the explicit intention of giving a platform to its development programmes in an international setting (Kärnman Citation2019). However, more than merely projecting the city’s internal narratives to a global audience, it could be argued that this event holds latent class differences in habitus and the reproduction of Bourdieusian social capital. Sailing is a sport that requires time and financial investment and has a tendency to be associated more with the production of greater economic capital gain than cultural capital gain (Ritchie Citation2015, 217). As a sport, it allows for status-seeking confirmation, reflecting the upper class’s ‘aesthetic/ethical dimensions, temporal/spatial orientations, material and symbolic status signs, and body hexis’ (Booth and Loy Citation1999, 10). In essence, it is a world away from sports that emphasise ‘physical contact, toughness, asceticism, and hard manual labour’ that tends to be favoured by lower classes (Wilson Citation2002). As such, egalitarian access to the model is not likely to be a high priority at such events.

By contrast, the purpose of the installation at the Culture Festival was far more overtly the gain in cultural capital. The 2019 event had a far broader target audience with stages appealing to a greater cross-section of social classes, thereby emphasising ecological, social, and financial sustainability. Ostensibly, the local demographic was the principal target with the inclusion of primarily Swedish nomenclature with secondary texts available to Anglophones. Spatially, the event was more spread out and much less demanding in formalities, allowing for greater access by the general public. The VR installation itself was located in the Jubileumspaviljongen, which was located outside the entrance to the Trädgårdsföreningen (the Garden Society of Gothenburg) at the foot of a main thoroughfare in the city. In terms of spheres of normative activity (Ellegård Citation2019, 8), it was far more likely to coincide with the pocket of local order for more people, thereby physically and socially enabling a broader spectrum of visitors.

Via a stationary AR installation, the Tourist Information centre at Kungsportsplatsen creates an additional audience dynamic. Here, a binocular viewing platform offers a time slice view of the former city gate, Kungsporten. The same platform also offers views of Gustav Adolfs torg (the main square) and Stora Bommen (the entrance to the harbour canal), focusing on places deemed intrinsically important to the city’s past. Its accompanying English nomenclature, whilst not explicitly excluding Swedes, linguistically points to an external rather than an internal user. Whereas museums ‘sacralise’ objects, space, and history through the enunciation of knowledgeable discourse (Mota Santos Citation2012, 445), the Tourist Information centre packages it for immediate consumption. The issue is that the material content of the visualisation is the same. Although the setting does not necessarily exclude the city’s inhabitants, its primary target audience is logically extra-local; without clearer semiotic transmission, annotation, or multimedia input, however, there is nothing to mediate the information for a tourist audience.

The museum and the virtual environment

Compared to the installation at the Tourist Information centre, the one at the Museum is more overtly positioned for twofold engagement with both locals and tourists. Its coincidence with the Museum’s investment in a new permanent exhibition exploring Gothenburg’s foundation also represents their primary concern with the city’s history. As with many historical museums, historicity is derived not just through the discourse of its content but in the architecture of the building itself; the East India House, in which the Museum is located, has significant meaning in the development of the city and is itself a cultural landmark. Located in the historic centre of the city, the building is a relic of the peak of Gothenburg’s mercantile past and has long demarcated a space for the culturally aware middle classes and wealthy benefactors (Falkemark Citation2010, 88) to maintain a stable identity in the city’s early modern roots.

The space of the historic centre operates as both a first place (Mota Santos, Citation2017) and as the city’s primary heritagescape. It is thus inextricably linked to a sense of heritage (Garden Citation2006). However, this cannot be said to be a universal heritage. Insulated within the historic centre, the Museum is in a somewhat restrictive location for marginalised populations. Property in the centre of Gothenburg is largely afforded only to institutions, businesses, and the wealthy; for the majority, issues surrounding class, ethnicity, and affordable accommodation mean that daily encounters in the city centre are largely between those who travel inwards from the peripheries of the city. The content and policy of the Museum are not in question in this regard; however, whilst the physical infrastructure of Gothenburg’s seventeenth-century fortifications has long since gone, there remain social hurdles in accessing the past in the central city. This is often manifested in practices of stigmatisation and exclusion, with ambivalence and territorial association to suburban locale compensating for subordination and disassociation with the urban centre (Johansson and Nils Citation2011, 48).

Certainly, this space provides strong hermeneutic foundations for the model’s display. The in situ video presentation as part of the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition benefits from the knowledge-making capacity of the Museum, but the dynamic is altered as far as the experience of the VR station is concerned. Whilst it draws its sense of meaning from its valorised location and credibility from the intellectual authority of the Museum as a trusted institution (Bennett Citation1995, 146), it simultaneously becomes unchallengeable and isolated. It should be cautioned against merely brushing off these dynamics as ‘soft power’. In his 1938 publication, Power, A New Social Analysis, Bertrand Russell argued that due to the propagation of education, the intellectual lacks the awe and power over belief that their spiritual antecedents in the clergy possessed (Russell Citation2004, 33). However, this view negates the nuances and confrontation with power on a local level.

I argue instead that intellectual power works differently to the power over opinion of Russell’s understanding. On the contrary, Foucault argues that intellectuals have been drawn closer to the masses as a result of ‘real, material, everyday struggles’ (Foucault Citation1980, 126). It is instead commonplace and accepted facts that are the building blocks of power. This is significant when, in light of alternative histories, an authorised narrative remains what is considered actual reality. Foucault’s reading of power dynamics reveals his conclusion that truth is a product of ‘a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation, and operation of statements’ (Foucault Citation1980, 133). When articulated in a museological context, a Foucauldian analysis of regimes of truth yields new truths and shapes social understanding for the inclusion of subaltern knowledges (Bennett Citation2018, 1).

Relatively, the visualisation gains its veracity from this setting, rather than its content. It engages in a pact of trust with space and place over the audience, using the weight of the Museum to formulate the user’s expectations and experience. Whilst the video embedded in the exhibition has the clear purpose of illustrating the city’s early beginnings, the Museum’s VR station creates the possibility for users to explore the historic space; however, the installation enrols them within the ecology of the Museum’s own internalised network.

Discussion

Neil Silberman points out that ‘remembering and commemorating is not merely preserving or digitally reconstructing a mute building or object’. Where process rather than product is the focus, he continues, ‘digital novelties whose rapid obsolescence, requires a constant flow of new, ever more visually striking representations just to keep up with the quickening pace of the digital age’ (Silberman Citation2015, 3). In this mode, meaning and memory are the fundamental purposes, whether as a form of education or an act of heritage-making. Great care is needed in publicising the VR experience; in general, it is difficult to pair a journalistic or touristic ideal to such an experience as this approach often fails to communicate any specific objectives beyond its novelty.

Typically, the rhetoric surrounding visualisations to some extent speaks to the pursuit of technology for its own sake, cut adrift from any governing theory or principle (Parry Citation2005). Where it is confined within the paradigm of tourism, it is difficult to conceive of digital surrogates beyond the product on the display – it is, in a sense, rendered final. However, in terms of communicating archaeological or historic data in a hermeneutic context, digitality presents an unfixed space to develop a platform able to evolve in any one of several directions to fulfil a more meaningful role in the place-based heritage mechanisms and potentially define future digital praxis in Gothenburg and elsewhere.

The inclusion of material with greater heterogeneity would signify a critical step forward. Approaches that layer visual representation alongside databases are well-represented in virtual heritage projects. Although they are better known as paid virtual reality applications, the Rome Reborn (Wells et al. Citation2009) and Digital Karnak (Citation2021) projects open in Google Earth and are annotated with information supplied by an associated database with links to landing pages, thereby offering greater depth than the mere visual representation of a digital surrogate. However, an archive that provides data is just one aspect of this issue. Importantly, it is the understanding of the re-use of archival material that is often limited by a lack of qualitative research. Archives, particularly those of an archaeological nature, lend themselves well to politicisation and an idealised past; when presented through digital surrogates, they can be problematic.

The Skopje 2014 project is a prime example of this. It utilises a Slavic Macedonian ideal that functionally enforced contemporary spatial division in what its detractors describe as ethnic segregation tied to the real-world erasure of the Ottoman urban space in the city (Mattioli Citation2014, 600). In models where the human aspect is only represented with placeholders, topics that aid engagement and inclusivity such as alterity, migration, and colonial affairs are all aspects of a city’s past that could be integrated. For Gothenburg, the first call in this instance is to mirror the narratology of the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition. In that installation, societal inequalities and historical living conditions are successfully incorporated within a holistic narrative (Illsley Citation2020). Historical lacunae are always present; however, rather than covering up the gaps by drawing on archaeological empiricism, in order to explore the humanistic aspect of time travel, a critical re-evaluation of the archives is a necessity.

An architectural spatial focus unbalances the anthropological epistemologies through which we encounter the digital city. Although it has been demonstrated that VR is a motivational and attractive medium, ‘learning or understanding will only be achieved if the physical and virtual interfaces are multisensorial and intuitive enough’ (Tost, Laia and Economou Citation2009, 161). An over-reliance on ocular-centric digital representation detracts from immersion. Aside from the occasional seagull, aural stimuli are lacking and the misleading audio description accompanying the exhibition needs attention. There is nothing in the way of meaningful olfactory or tactile stimuli. While early successes were seen with apps offering hybrid views of the past and present such as the Museum of London’s Streetmuseum (currently offline for redevelopment purposes), the precedence was set by Tidvis (Citation2020) visualisation of ‘The Port of Oslo in 1798ʹ. Their 3D visualisation, accessible via smartphone or tablet as well as through a web platform, works symbiotically with a curated walking tour focusing on historical sights, sounds, and scents.

This approach could first be trialled at the tourist bureau but also supplement existing walking tours. Augmented 4D city experiences are often focused on enhancing visitors’ learning experiences within the sphere of cultural heritage (Niebling et al. Citation2018), but they can also augment the experiences of residents. The city of Gothenburg produces mapped walking tours in six languages with the intention of helping newly arrived denizens become better acquainted with the city as a historic environment. Routes correlate to the spaces within the boundaries of the historic city, offering the opportunity to create time-annotated AR snapshots using archival images and visualisation to ameliorate users’ experience and deepen their historical understanding. By presenting the space in a manner accessible to tourists and residents alike with increased sensory engagement, this approach anchors the digital world in reality by shifting the focus towards an embodied experience.

In this iteration, the effective transmission of Gothenburg’s urban heritage is sought through resolution, epitomising the assumption that ‘visual realism, immersion, and navigation are sufficient to simulate the past, and constitute a universal didactic method’ (Tost, Laia Citation2019, 2:2). Drawing on ‘storytelling, responsive characters, emotivity, or enhanced interaction’ (2019, 2:1) elevates the status of the traditional 3D architectural model. Reaching the benchmarks set by the London Charter and the Seville Principles should be important criteria in improving users’ experience with the affective performance of heritage narratives. Relating the current experience to the turn towards critical thinking in the evaluation of digital cultural resources (Economou et al. Citation2019) must be applied here. One approach that might encapsulate much of this process, as well as the gamification aspect discussed below, could be exemplified by the Virtual Sydney Rocks (VSR) project, which currently allows for both guided tours and the user’s freedom to explore (Devine Citation2012, 530). The ultimate goal of the VSR project is to promulgate active participation. Future developments will allow social and cultural immersion through role-playing varying by gender, social status, and ethnicity (Devine Citation2018, 179).

The limitations of architecturally focused models, ‘both as a tool for archaeological research and as means of presenting cultural heritage to the public’ (Woolford and Dunn Citation2013, 16:1), underline the need for a narrative focus throughout the process of visualisation. This calls for a reconceptualisation of how this information is retrieved from and characterised by digital surrogates. In their book Theatre/Archaeology, Pearson and Shanks describe theatre/archaeology as a blurred genre wherein academic, artistic, and cultural efforts converge (Pearson and Shanks Citation2001). An effective bridging between the self (the user) and space and place (the visualisation) could be achieved by drawing upon theatre/archaeology’s greater performativity of perceptual stimuli. Whilst some degree of interdisciplinarity is encountered, the bias is towards architectural components. True interdisciplinarity involves the regular and fluid exchange of ideas – in this case, from a greater breadth of disciplines – to achieve enrichment. By making available toolkits to supply cultural heritage practitioners with the understanding of how interactive technologies are built, there is the potential of better achieving interpretative and visitor experience goals. Whilst there are obvious limitations to these endeavours, notably time and funding (Maye et al. Citation2017, 230), taking advantage of such initiatives may, in turn, engender greater input for heritage epractitioners in the creative process. An example of this is the DigMus Project (Bäckvall Citation2020).

Gamification, using Champion’s definition (2020) of a game – namely, that of ‘a challenge that offers up the possibility of temporary or permanent tactical resolution without harmful outcomes to the real-world situation of the participant of content’ – is a route that the Stadsbyggnadskontoret has already begun to consider. While the implication is that games are not able to ‘record, preserve or recreate’, nor communicate the need to care for the fragility of inanimate objects efficiently, they can be used to advance fact procurement and environmental presence, if not always cultural presence (Champion Citation2020). Such approaches enable digital cultural custodians to communicate, enrich, and educate those in the present through an understanding of the past as well as promote multi-modal interactivity. Heritage is often considered the enrolment of place-related values that can be aesthetic, historic, social, or spiritual (Champion Citation2008, 223) and not just simply factual or scientific. However, whether fictional or non-fictional, gamifying historic content should not be an attempt to establish authority or authenticity, nor should it reproduce unhelpful dichotomies between what is real or not. The focus should be the communication of meaning, a sense of place, and the promotion of ‘history as a shared cultural process spread across multiple forms, practices, social domains, and stakeholders’ (Chapman, Foka, and Westin Citation2016, 361). As a product of human activity, virtual spaces are never devoid of anthropological content. However, the architectural focus of the Gothenburg model and a great many others fail to achieve hermeneutic richness through insufficient inworld prompting or encouragement. By comparison, gamification offers access to a wider range of narratives, rather than paradoxically using novel technology to reaffirm the grand narratives of old.

Regarding the filmographic treatment of visualisation, non-linear narratives and the use of montage can be employed to visualise the city. Collaborative encounters with dedicated monteurs and narrators can move the visualisation beyond merely memorialising the city’s mythologised form. Scale is the key to this approach. Selectively targeting specific sites such as entry points to the city, one or more of these approaches could be trialled. By narrowing the focus, the reality of historical politics such as the right to space, cultural capital, and alterity could be explored in order to intensify user engagement under the social conditions of both the past and present. This could, for example, draw influence from novel concepts such as Papers, Please, a critically acclaimed concept gamifying the responsibilities of an immigration officer from a fictional country targeting real-world reform through rethinking the conventions of gameplay and narrative design (Kelly Citation2015). This would, of course, demand more labour and attention, but it is likely that greater creative engagement with the subject will translate to greater user engagement.

Cultural and chronological context is clearly important, particularly in light of anniversary events. In Gothenburg, if the emphasis of rhetoric for the fourth centenary is ‘a Gothenburg for everyone’, then the topography of the model’s propagation must be levelled. As digitality intrinsically supports and encourages mobility, pop-up museums at local transport or culture hubs or even empty shop spaces could be utilised to promote multi-sited curation in order to reach suburban population centres. However, in doing so, great care must be taken to not colonialise outlying heritage narratives. In essence, the goal should be participation in rather than the uptake of a narrative. If we consider museum entities and heritage as commons in relation to societal stakes and interest, then participation is both desirable and feasible. Although allowing for the reinterpretation and re-use of digital material is envisioned, it has yet to find its way into the Stadsbyggnadskontoret’s repository for 3D data. Vis-à-vis Oslo, TidVis offers further inspiration in open sourcing their files and encouraging the public to ‘download, use, remix and build upon’ their work. Very much in the ‘hackathon’ vein, this approach, whilst not necessarily stable or reliable (Arrigoni, Schofield, and Pisanty Citation2019, 6), would not only offer a creative stimulus but also establish a platform for the public to envision heritage through non-official channels that are disconnected from the political stances and choices of its current performative settings.

Conclusion

If four hundred years is considered a milestone for the city and its origin is central to its story, then genuine accessibility and the transcendence of status and space are required in realising the vision of a Gothenburg that involves everyone. Meaningful associations to the city’s past via narratives focusing on the under classes and religious or ethnic minorities have already been demonstrated by the production of the ‘Birth of Gothenburg’ exhibition. Although both aesthetically pleasing and coupled to the exhibition’s discourse, the visualisation of the seventeenth century’s first outings have yet to build upon the critical dynamic established by the exhibition.

Reconfiguring the visualisation’s form, narrative, and technological approaches are key to achieving this. There are numerous precedents that demonstrate various approaches to virtual heritage through digital surrogacy and, in some cases, multiple combinations within the same digital iteration of space. In contemporary museology and tourism, it has become both relatively simple and commonplace to utilise computer visualisations for communicating heritage. However, while it is clear that there is a degree of imagination required on behalf of the user, it is no longer enough to simply offer a digitised space and allow the technological aspect to provide vitality. A wider understanding of the audience and their needs is especially necessary when the digital representation of objects and spaces is increasingly profane. In a world where the museum industry can seldom compete with the digital aesthetics of the entertainment industry in terms of digital renderings of space, evincing a critical commitment to sources, the procedures of creation, and the politics of presentation becomes a necessity. Authority is thus sought through transparency, engagement, and accessibility.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Andrine Nilsen for an excellent critical discussion in the preparation of this paper; to Carina Sjöholm, Dennis Axelsson, and Tom Wennberg of the City of Gothenburg Museum for their feedback and facilitating my secondment, as well as to Arvid Försberg of Stadsbyggnadskontoret for the preview of the model and the screen captures.

Disclosure statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

William R. Illsley

William R. Illsley is a PhD candidate and early-stage researcher on the CHEurope project. He studies archaeological archives and visualisations as digital manifestations of heritage. His primary aim is to explore the digital spaces through which the public encounter the historic environment.

Notes

2. Author’s translation.

References

- Allt för Sverige. 2019. Season 9, episode 5. Directed by C. Åkerlund. Aired November 24th,2019, on SVT 1.

- Arrigoni, G., T. Schofield, and D. T. Pisanty. 2019. “Framing Collaborative Processes of Digital Transformation in Cultural Organisations: From Literary Archives to Augmented Reality.” Museum Management and Curatorship 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2019.1683880.

- Bäckvall, M. 2020. “The DigMus Project: Newly Funded Project through Nordplus.” The Digital Humanities Uppsala Blog, Accessed May 19th. http://digitalhumanities.blogg.uu.se/2020/05/14/the-digmus-project-newly-funded-project-through-nordplus/?fbclid=IwAR3Qn199VpyaFQSHiitfERpOmj5lZFQN3EG5xV53Q92B5AqS7zJpic3gxxQ

- Bennett, T. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bennett, T. 2018. Museums, Power, Knowledge: Selected Essays. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Booth, D., and J. Loy. 1999. “Sport, Status, and Style.” Sport History Review 30 (1): 1–26.

- Champion, E. 2008. “Otherness of Place: Game‐based Interaction and Learning in Virtual Heritage Projects.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14 (3): 210–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250801953686.

- Champion, E. 2009. “Roles and Worlds in the Hybrid RPG Game of Oblivion.” International Journal of Role-Playing 1: 37–51.

- Champion, E. 2015. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Champion, E. 2019. “From Historical Models to Virtual Heritage Simulations.” In Der Modelle Tugend 2.0: Digitale 3D-Rekonstruktion als virtueller Raum der architekturhistorischen Forschung, edited by P. Kuroczyński, M. Pfarr-Harfst and S. Münster, 337–351. Heidelberg: arthistoricum

- Champion, E. 2020. “Culturally Significant Presence In Single-Player Computer Games.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 13 (4): 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3414831.

- Chapman, A., A. Foka, and J. Westin. 2016. “Introduction: What Is Historical Game Studies?” Rethinking History 21 (3): 358–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2016.1256638.

- City of Amsterdam. 2021. “De Groei Van De Grachtengordel/Expansion of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth Century.” Accessed March 11th. https://maps.amsterdam.nl/?LANG=en

- Conway, P. 2014. “Digital Transformations and the Archival Nature of Surrogates.” Archival Science 15 (1): 51–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-014-9219-z.

- Debray, R., and E. Rauth. 1995. “The Three Ages of Looking.” Critical Inquiry 21 (3): 529–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/448763.

- Denard, H. 2012. “A New Introduction to the London Charter.” In Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage, edited by A. Bentkowska-Kafel, H. Denard, and D. Baker, 57–72. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing .

- Devine, K. 2012. “Making Place: Designing and Building an Engaging, Interactive and Pedagogical Historical World.” In 2012 16th International Conference on Information Visualisation, 528–533. Montpellier, France.

- Devine, K. 2018. “A Drama in Time: The Life of A City.” In Cities in the Digital Age: Exploring Past, Present, and Future, edited by A. G. da Câmara, C. Bottaini, D. Alves, H. Murteira, H. Barreira, M. L. Botelho, and P. S. Rodrigues, 173–184. Porto: CITCEM–Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar Cultura, Espaço e Memória.

- Digital Karnak. 2021. “Digital Karnak.” University of California, Accessed April 28th. http://dlib.etc.ucla.edu/projects/Karnak

- Dunn, S. 2019. “A History of Place in the Digital Age.” In Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Economou, M., I. Ruthven, A. Galani, M. Dobreva, M. de Niet, M. Economou, I. Ruthven, A. Galani, M. Dobreva, and M. D. Niet. 2019. “Editorial Note for Special Issue on the Evaluation of Digital Cultural Resources—January 2019.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 12 (1): 1–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3307313.

- Ellegård, K. 2019. “The Roots and Diffusion of Time-Geography.” In Time Geography in the Global Context: An Anthology, edited by E. Kajsa, 1–18. London: New York: Routledge.

- Falkemark, G. 2010. “The Gothenburg Spirit.” In (Re)searching Gothenburg: Essays on a Changing City, edited by H. Holgersson, C. Thörn, H. Thörn, and W. Mattias, 83–90. Göteborg: Glänta Produktion.

- Flyover Zone. 2021. “Rome Reborn.” Accessed March 11th. https://www.romereborn.org

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/ Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977, Translated by C. Gordon, L. Marshall, J. Mepham, and K. Soper. New York: Pantheon.

- Foucault, M., and J. Miskowiec. 1986. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16 (1): 22–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/464648.

- Galeazzi, F., P. D. G. D. Franco, and J. L. Matthews. 2015. “Comparing 2D Pictures with 3D Replicas for the Digital Preservation and Analysis of Tangible Heritage.” Museum Management and Curatorship 30 (5): 462–483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1042515.

- Garden, M. E. 2006. “The Heritagescape: Looking at Landscapes of the Past.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (5): 394–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250600821621.

- Gea, C., M. Juan, J. L. Ambrosio Toval, F. Alemán, J. Nicolás, and M. Flores. 2013. “The London Charter and the Seville Principles as Sources of Requirements for E-Archaeology Systems Development Purposes.” Virtual Archaeology Review 4 (9): 205–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2013.4275.

- Göteborgs Stadsmuseum. 2017. Göteborgs Födelse. Gothenburg: Göteborgs Stadsmuseum.

- Göteborgs Stadsmuseum. 2019. “Upplev 1600-talets Göteborg I Virtual Reality.” Gothenburg Culture Festival, Accessed September 30th. https://gothenburgculturefestival.com/program/29217

- Gumbrecht, H. U. 2004. Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Guttentag, D. A. 2010. “Virtual Reality: Applications and Implications for Tourism.” Tourism Management 31 (5): 637–651. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.003.

- Hallén, P. 2017. “The Dual Town 1730–1815: Trade as a Transformation Force of the Early Modern Town - the Case of Göteborg and Majorna” In Urban Variation. Utopia, Planning and Practice, edited by P. Cornell, L. Ersgård and A. Nilsen, 189–210. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Press, Inc.

- Holtorf, C. 2017. “The Meaning of Time Travel.” In The Archaeology of Time Travel: Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century, edited by B. Petersson and C. Holtorf, 1–24. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Illsley, W. R. 2020. “Göteborgs Födelse (The Birth of Gothenburg). Permanent Exhibition, Gothenburg City Museum, Gothenburg, Sweden.” Nordisk Museologi 28 (1): 120–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.7988.

- International Forum of Virtual Archaeology. 2011. Principles of Seville: International Principles of Virtual Archaeology. Seville: International Forum of Virtual Archaeology.

- Johansson, T., and H. Nils. 2011. “The Art of Choosing the Right Tram: Schooling, Segregation and Youth Culture.” Acta Sociologica 54 (1): 45–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699310392602.

- Kärnman, K. 2019. “Let the Adventure Begin!” Göteborg & , Accessed 30th September 30th. https://goteborgco.se/en/tag/volvo-ocean-race-en

- Kärnman, K. 2019. “Let the Adventure Begin!” Göteborg & Co. Accessed 30th September. https://goteborgco.se/en/tag/volvo-ocean-race-en/

- Kelly, M. 2015. “The Game of Politics.” Games and Culture 13 (5): 459–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015623897

- Kristiansen, K. 2014. “Towards a New Paradigm? Towards a New Paradigm? the Third Science Revolution and Its Possible Consequences in Archaeology.” Current Swedish Archaeology 22 (1): 11–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2014.01.

- Lagerlöf, B. 2019. “Gör En Virtuell Resa På 400 År Genom Göteborg.” Vårt Göteborg, Accessed September 30th. https://vartgoteborg.se/gor-en-virtuell-resa-pa-400-ar-genom-goteborg

- Latour, B., and S. Woolgar. 1986. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Leroi-Gourhan, A. 1993. Gesture and Speech, Translated by A. B. Berger. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Lowenthal, D. 2015. The Past Is a Foreign Country - Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mattioli, F. 2014. “Unchanging Boundaries: the Reconstruction of Skopje and the Politics of Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (6): 599–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.818569

- Maye, L. A., D. Bouchard, G. Avram, and L. Ciolfi. 2017. “Supporting Cultural Heritage Professionals Adopting and Shaping Interactive Technologies in Museums.” In DIS ‘17: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, edited by O. Mival, M. Smyth, and P. Dalsgaard, 221–232. Edinburgh: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Moretti, F. 1998. Atlas of the European Novel 1800-1900. London; New York: Verso

- Mota Santos, P. 2012. “The Power of Knowledge: Tourism and the Production of Heritage in Porto’s Old City.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18 (5): 444–458. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.598541

- Mota Santos, P. 2017. “The Concept of ‘First-place’ as an Aristotelean Exercise on the Metaphysics of Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (2): 121–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1393448

- Niebling, F., F. Maiwald, K. Barthel, and M. E. Latoschik. 2018. “4D Augmented City Models, Photogrammetric Creation and Dissemination.” In Digital Research and Education in Architectural Heritage. UHDL 2017, DECH 2017. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 817, edited by S. Münster, K. Friedrichs, F. Niebling, and A. Seidel-Grzesińska, 196-212. Cham: Springer.

- Nilsen, A. 2020. Vernacular Buildings and Urban Social Practice: Wood and People in Early Modern Swedish Society. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Öbrink, M., G. Williams, and A. Nilsen. 2018. “Townscapes: Utopia and Practice in a Thematic Comparison of Nya Lödöse and Gothenburg.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22 (2): 274–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-017-0423-4.

- Orrman, E. 2016. “Growth and Stagnation of Population and Settlement.” In The Cambridge History of Scandinavia: Volume II 1520-1870, edited by E. I. Kouri and J. E. Olesen, 135–175. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Parry, R. 2005. “Digital Heritage and the Rise of Theory in Museum Computing.” Museum Management and Curatorship 20 (4): 333–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770500802004.

- Pearson, M., and M. Shanks. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology. London. New York: Routledge.

- Petersson, B. 2017. “Anachronism and Time Travel.” In The Archaeology of Time Travel, edited by B. Petersson and C. Holtorf, 281–298. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing .

- Petersson, B. 2018. “From Storing to Storytelling: Archaeological Museums and Digitisation.” In Archaeology and Archaeological Information in the Digital Society, edited by I. Huvila, 70–105. London: New York: Routledge.

- Poole, S. 2017. “Ghosts in the Garden: Locative Gameplay and Historical Interpretation from Below.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (3): 300–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1347887.

- Pujol, L., and E. Champion. 2012. “Evaluating Presence in Cultural Heritage Projects.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18 (1): 83–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.577796.

- Rabinowitz, A. 2015. “The Work of Archaeology in the Age of Digital Surrogacy.” In Visions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean Archaeology, edited by B. R. Olson and W. R. Caraher, 27–38. Grand Forks: Digital Press @ The University of North Dakota.

- Ritchie, I. 2015. “Social Class and Sport.” In Routledge Handbook of the Sociology of Sport, edited by R. Giulianotti, 210–219. London, New York: Routledge.

- Russell, B. 2004. Power: A New Social Analysis. London, New York: Routledge.

- Silberman, N. 2015. “What are Memories Made Of? the Untapped Power of Digital Heritage.” In Behind the Pixel: Practices and Concepts in Virtual Reality, edited by L. P. Tost and S. M. Subías, 1–9. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

- Statens Fastighetsverk. 2021. “Skansen Kronan, Göteborg.” Statens Fastighetsverk, Accessed April 7th. https://www.sfv.se/fastigheter/sok/sverige/vastra-gotalands-lan/skansen-kronan-goteborg

- Thorén, C. 2011. “Till Allmänhetens Tjänst.” In Att Fånga Det Flyktiga: Göteborgs Museum 150 År, edited by M. Sjölin, 268–281. Stockholm: Göteborgs stadsmuseum & Carlssons Bokförlag.

- Tidvis. 2020. “The Port of Oslo in 1798.” Tidvis AS, Accessed May 26th. https://oslohavn1798.no

- Tost, Laia, P. 2019. “Did We Just Travel to the Past? Building and Evaluating with Cultural Presence Different Modes of VR-Mediated Experiences in Virtual Archaeology.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 12 (1): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3230678.

- Tost, Laia, P., and M. Economou. 2009. “Worth a Thousand Words? the Usefulness of Immersive Virtual Reality for Learning in Cultural Heritage Settings.” International Journal of Architectural Computing 7 (1): 157–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1260/147807709788549367.

- Vandenberghe, F. 2016. “Régis Debray and Mediation Studies, or How Does an Idea Become a Material Force?” Thesis Eleven 89 (1): 23–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513607076130.

- Visualizing Venice. 2021. “Visualizing Venice: Exploring a Cities Past.” Accessed March 11th. http://www.visualizingvenice.org/visu

- Waterton, E. 2010. Politics, Policy and the Discourses of Heritage in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wells, S., B. Frischer, D. Ross, and C. Keller. 2009. “Rome Reborn in Google Earth.” In Making History Interactive. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA). Proceedings of the 37th International Conference Williamsburg, Virginia, United States of America, March 22–26,2009, edited by B. Frischer, J. W. Crawford, and D. Koller. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Wennberg, T. 2018. “Hur Planerade Man Staden? Göteborg Som Ideal Stad Och Fästning.” In Göteborg: De Första 100 Åren, edited by B. Lindberg, 19–32. Göteborg: Kungl: Vetenskaps- och Vitterhets-Samhället i Göteborg.

- Westin, J. 2014. “Inking a Past; Visualization as a Shedding of Uncertainty.” Visual Anthropology Review 30 (2): 139–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12044.

- Westin, J., and R. Hedlund. 2016. “Polychronia: Negotiating the Popular Representation of a Common past in Assassin’s Creed.” Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds 8 (1): 3–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.8.1.3_1.

- Wilson, T. C. 2002. “The Paradox of Social Class and Sports Involvement: The Roles of Cultural and Economic Capital.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 37 (1): 5–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690202037001001.

- Woolford, K., and S. Dunn. 2013. “Experimental Archeology and Serious Games: Challenges of Inhabiting Virtual Heritage”. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 6 (4): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2532630.2532632.