ABSTRACT

The rapid growth of cities can compromise their heritage by: diluting the distinctive character of diverse urban areas, destroying historic sites and buildings, and interrupting evolutionary continuity. This paper presents an innovative approach to addressing these problems. Using collaborative experimentation, a School of Urban Interventions was established to test the impact of different development scenarios on a diversity of urban areas in Krasnoyarsk (Siberia, Russia). The School created affordable tools to enable a more gentle, iterative and gradual way of developing often fragile historic areas, allowing hypotheses and design solutions to be examined before permanent changes were made. This collaborative experimentation approach helps participants to find shared collective values in the course of working with territory through negotiation, through participatory methods and grounded initiatives, helping to inform urban and architectural practices and therefore shape the cities’ heritage futures. The approach can also restore broken ties between the city and its inhabitants, empowering young professionals and creating active citizens while revealing hidden cultural potential. Being co-organised by the local university, this project also helped educate students to become activists and involved the university in urban life.

Introduction

The urban environment can be both sensitive and fragile. It is also constantly evolving, with implications for defining what constitutes ‘historic’ and for the way material fabric representing earlier and contemporary phases is valued, adapted, re-used or disregarded. The city and its heritage never simply ‘are’. They are in a constant state of becoming, new layers added to old, creating an increasingly complex urban palimpsest. Those historic parts of the city, their buildings, spaces and districts and their associated practices, lifeways, rhythms and rituals will shape the city’s heritage and define its character and identity. Heritage, character and identity are also often used to create a brand, to market the contemporary city, for example, and to promote its preparedness for a bright and prosperous future.

The historic urban environment therefore presents a constant and significant challenge to those invested in a city’s future, whether their focus is more on heritage protection (as heritage managers or conservation architects) or on growth and development (as developers, architects and arguably also politicians). The challenge can be summarised in the need to achieve balance between these priorities. It sounds simple but rarely has this balance been successfully struck and the relationships often remain tense, between old and new, preservation and growth, people and place.

Yet recognising the complexity of opportunities for growth within urban areas is made easier by understanding the values attached to those elements (e.g. buildings, historic sites or character areas) of which they are composed, values which are both varied and in some cases also highly contested. While defining historic and evidential values (and even perhaps aesthetic value) can be straightforward (a rare architectural form or feature, or the place where an important historic event occurred, or the location of known and previously unexcavated archaeological remains), the fact is that urban areas are also significant as a collection of spaces and places each with individual and shared or communal values, recognised and held by distinct cultural groups or by families or even by individuals for very specific personal reasons. These are often also referred to as ‘social values’ (e.g. English Heritage Citation2008; Jones Citation2017).

For the city’s occupants, these social values are often the most important. Yet, where these socially-valued spaces and places do not also hold what specialists recognise as architectural, historic or aesthetic interest, they are typically excluded from official heritage protection lists and often considered ‘blank slates’ in terms of development. Put simply, the places local people value often go unprotected; while places given national recognition and statutory protection are often not those places valued within communities (e.g. Gard’ner Citation2004). Therefore, except in those rare cases where urban areas have some protection in their entirety,Footnote1 or where ‘local lists’ give socially valued places some recognition and status within the planning system, the majority of most urban areas can be subject to transformative development without any regard for the values given to those areas by local people. In these situations, each intervention has the potential to destroy or interrupt important social values resulting in discontinuities between urban development and citizens. Such discontinuities can then impact less tangible elements of people’s personal or collective heritage such as local traditions and narratives. These observations are made within the context of urban theories which unanimously claim that development is inevitable and significant for every urban environment, including heritage sites and historic urban landscapes, to provide survivability and to guarantee the city’s inclusion in modern life (Caniggia and Maffei Citation2001; Dalla Negra Citation2015).

In Siberia, two strategies currently dominate conventional urban practices: non-intervention (or museumization) and radical permanent change. Here we argue that both strategies will usually be problematic within the context of socially-engaged heritage practice and that a viable alternative approach and a method for achieving it is therefore required. This paper suggests one such approach, by analysing existing theories and approaches to the historic urban environment as a backdrop to experimenting on the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk. Starting with a detailed consideration of the theoretical context, showing that studies of this kind are more often of an inductive nature, this paper then turns to the research methods and a description of the areas where the experiment was conducted. A review of the outcomes follows before a closing discussion which integrates the results of the study into the existing scientific context. Specifically, the paper will:

Test a methodology that creates the opportunity to retrieve memories and help articulate heritage values felt for a place by its community, with a view to providing sustainability and continuity in its development.

Use this methodology and the examples to test proposed scenarios of development before any permanent changes are made, in the hope of reducing negative impacts and the destruction of values while providing the opportunity for sustainable community-based developments within those scenarios.

We therefore follow the suggestions of Jacobs 1992 [Citation1961], 6) in recognising the city as, ‘an immense laboratory of trial and error, failure and success, in city building and city design … in which city planning [can learn and form and test] its theories’.

Framing a collaborative experimental approach

Authors, including Stepin, Gorochov, and Rozov (Citation1999) describing current developments in the philosophy of science, mention a move towards variability, change, probability research, openness and the need to assess opportunities and challenges within different scenarios. They also describe scientists prioritising subjectivity and consensus-based communication. Speaking about design, Dunne and Raby (Citation2013, 4) have emphasised the importance of considering different futures and the requirement of designers to be ready for them.Footnote2 This orientation of modern science towards the study of complex, self-developing systems significantly restructures the ideals and norms of heritage research, emphasising the role of actors (e.g. after Latour Citation2011) through ‘the multiplicity of distinct perspectives and the importance of socially shared action and knowledge’ (Groat and Wang Citation2013, 76) effectively transforming value-neutral research (Stepin, Gorochov, and Rozov Citation1999). Taken together, these positions suggest that recognising the variety of socially-constructed scenarios, actors and opinions is a prerequisite to achieving a more nuanced, future- and value-oriented, consensual and socially-sustainable approach to urban developments and one that embraces the key ingredient of urban heritage management.

However, despite these trends, and notably in Russia, practical urban development quite often embraces positivist principles, especially when it comes to development that impacts upon or incorporates traditionally recognised heritage sites. As already stated, within Russia, two opposite deterministic approaches (non-intervention and radical change) still predominate, supported either by tightly controlled conservation doctrines and restrictions or strict design regulations for new construction.

Building on the earlier observations of Jacobs 1992 [Citation1961], the consequent phenomena of atomisation and sterilisation of urban areas are often visible in urban environments. Approaches to urban development are often radical and pragmatic (e.g. Rowe Citation1996). However, the speed of urban growth has resulted in a visible crisis in the deterministic ‘production of space’ (Lefebvre Citation1991) causing a search for new approaches to the conceptualisation of urban processes and instruments (Zachary and Dobson Citation2020). Unplanned solutions and adaptable self-made tradition-based developments, the result of a phenomenon which urban morphologists have called ‘spontaneous consciousness’ (after Caniggia and Maffei Citation2001, 39–40) has, to a large extent, formed vernacular historic cities.

To understand how this spontaneous consciousness can be both recognised as part of the city’s heritage and integrated into management strategies, researchers have turned to forms of democratisation of urban space (Lefebvre Citation1991), emphasising the role of design and the designer: empowering, informing and promoting the best social practices, where prosumerism draws users into the project, making design an interface between top-down (strategic) and grounded (tactical) layers, mediating between participants by creating scenarios (Franqueira Citation2007). Generally, there are currently many different strands of urbanism, which stem from various philosophical approaches united by a belief in the necessity of social engagement.Footnote3 Authors claim that DIY politics in different contexts (architecture, music, fashion, etc) contributes to slower, simpler, more gentle, sustainable, self-organised forms of production, in which the notions of scarcity and consumption are re-evaluated. The focus thus shifts from strategists (governments and developers), to tactical users of space and individuals whose ‘intersecting writings compose a manifold story that has neither author nor spectator, shaped out of fragments of trajectories and alterations of spaces’ (de Certeau Citation1984, 93). Thus, this spontaneous consciousness, adapting to inherited civil substance while dealing with heritage, may have currency if knowledge about the inherited environment is reintroduced through participatory research and design during the process of consensual negotiations.

This transformation of a general set of principles from objective or scientific to ethical has also determined the transformation of understandings of heritage.Footnote4 Despite differences of approach across all of these areas, researchers often claim the positive effects of a collaborative heritage process (e.g. Drury, McPherson, and Heritage Citation2008; Yung, Lai, and Yu Citation2016), but emphasise that the effects are locally-specific. Some of these new ideas on heritage are often enshrined in conventions, including notably the prominent placing of social values as a concept within The Burra Charter (Australia Walker and Marquis-Kyle Citation2004), English Heritage’s Conservation Principles (English Heritage Citation2008) and the Faro Convention where everybody’s right to heritage is aligned to principles central to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Council of Europe Citation2009).

The growing literature on participatory values-oriented practices in the heritage sector is characterised by a variety of case studies and analysis of specific precedents.Footnote5 Together these examples explore different methods of memory-retrieval and evaluate practical cases of participatory approaches to the development of heritage sites around the world. Thus, a grounded participatory approach to urban heritage areas develops inductively to a large extent, provoking the appearance of numerous practice-based experimental case studies, embracing different geographies and social backgrounds. It is for this reason that we propose an experimental method which is ideologically derived from previous achievements in urban research and practices on a strategic level, while tactically proposing locally-specific approaches.

Methodology

Three relevant shifts have recently dominated heritage discourse: first, a shift in valuation from grand, monumental architectural objects to the entirety of historic landscapes, encompassing intangible components; second, a shift from national significance to local identities; and third, a shift from exclusively expert evaluation to more inclusive evaluations of heritage significance. These shifts should all imply a move towards community engagement, meaning and identity. This is however less well developed in practice than in theory. It is this interface between practice and theory that forms the focus of this paper and the example that it presents.

The example is of Krasnoyarsk, one of the largest cities in Russia (1.15 million people in 2021) and the largest educational, economic and industrial centre of Eastern Siberia. Founded in 1628, the city is located in central Russia () on either side of the Yenisei river. It has a rich and multilayered cultural and architectural history which is still embodied within its historic environment. Like many Russian cities, after Perestroyka in 1991, Krasnoyarsk developed erratically, with new developments destroying local identities. Russian architect E.M. Panov claimed: ‘historical buildings, the key elements in the structure and image of the city, have survived only in fragments: a chapel “Chasovnya” with modified proportions, Pokrovskiy Cathedral, which is lost among high-rise buildings […]. The importance of heritage in the urban system fades away’ (cited in Gevel Citation2012, 3). Yet Krasnoyarsk is an important cultural centre, hosting one of the country’s largest universities of federal significance – the Siberian Federal University (SFU). An aspect of this project was to give this important institution more immersion in the life of the city.

Figure 1. Above: the location of Krasnoyarsk. Below: the location of the three case studies in the city. (Maps: Daria Belova).

Against this background, researchers from Krasnoyarsk initiated an experiment which aimed to test a methodology for temporary participatory interventions across some of the city’s diverse historic areas (detailed below and shown in ). The experiment was named: the School of Urban Interventions (hereafter ‘the School’) and was based on a democratic co-creative idea of heritage as a way of thinking about place and identity. The School was designed for: students, specifically graduates majoring in architecture, heritage, design, urban planning, sociology and history; and for artists and social designers. It was also designed for anyone who worked or wanted to learn how to work with the historic urban environment and with heritage and how to be active and empowered while engaging communities in the process of co-creating the city’s diversity of possible futures.

From many potential participants, people of different ages, genders and backgrounds were selected on the basis of essays they had written, answering the question: ‘What would you like to better understand about Krasnoyarsk, and why is the city’s heritage important for you and for its future?’ The approach of the School was largely based on Participatory Action Research (after e.g. Kindon, Pain, and Kesby Citation2007). This involved organisers of the School and facilitators initiating studies and dialogues to attract, inspire and empower the local activists. For their part, and with the same purpose, the local activists initiated dialogues with local communities.

Over ten intense days, the participants were divided into three teams (comprising people we refer to as local activists alongside representatives of the local communities) which each studied, conducted research, and designed and implemented temporary interventions together with local communities at one of three selected locations in Krasnoyarsk under the guidance of specialist facilitators who then analysed the results of the interventions. The facilitators comprised seven international specialists in different fields – from architecture and urbanism to sociology and business, from Krasnoyarsk, Moscow and St. Petersburg. These facilitators informed and empowered the participants, introducing their theoretical and practical experience in urban development and heritage. The School took place from 20–30 August 2019. Materials for interventions were provided. Participation was free. The results of the School were presented at the thirteenth Krasnoyarsk Museum Biennale (http://biennale.ru/) and the annual Krasnoyarsk Book Culture Fair (https://kryakk.ru.com). The process and the results of these interventions were published in local media.

The approach can be summarised as a three-layered process of engagement:

Initial dialogue comprising a set of interviews with the community initiated by students of the School operating as local activists.

During this initial dialogue, the local activists collected local memories, stories and narratives with the aim of agreeing on possible interventions, together with the local communities.

Local activists helped the communities become involved in the preparation of interventions and associated events.

The engagement between School students and local communities occurred mainly during the day, by several students working together with people informally in public and semi-public spaces. If communities voluntarily engaged and showed their initial interest, the conversations continued, sometimes leading to their participation in activities. Communities were invited to propose their own activities or ideas. People had every opportunity to not engage, withdraw or to take part, without pressure, whenever they wanted. Interviews and conversations were not recorded to keep the informal atmosphere. Students were instructed to be aware of any potential risk to participants, but in projects there was minimal potential for harm. It should be added that awareness of formal ethical consent procedures exists in Russia, but the procedures are quite unusual, and no agreed obligatory process exists within the host University for such procedures to be introduced. Having trained partly in the international environment, the project lead was aware of internationally-accepted ethical practices and nonetheless implemented these within this project.

The selected programme included theoretical, practical, reflective and research components: Project organisers contacted local museums, institutions and other bodies and activists who might be interested in the results of the School and its development. The School’s teams aimed at reinforcing local networks of activists and stakeholders, to involve and guarantee the sustainable development of projects following the School’s conclusion. To achieve this, sociologists provided training in communication. Experts gave participants the basic brief knowledge of heritage, community engagement and digital technologies, urban studies and research, project management and finances, and explained what the culture of experiment means in a wider sense. Participants studied how historical and cultural memory might work, how it is formed in architectural context and how it is transmitted, what it means for citizens and what could be done with it. The School also aimed to inform a wider audience and empower activists to transfer their experiences. The School therefore established a set of public talks, lectures and presentations, aimed at informing and involving as many citizens as possible.

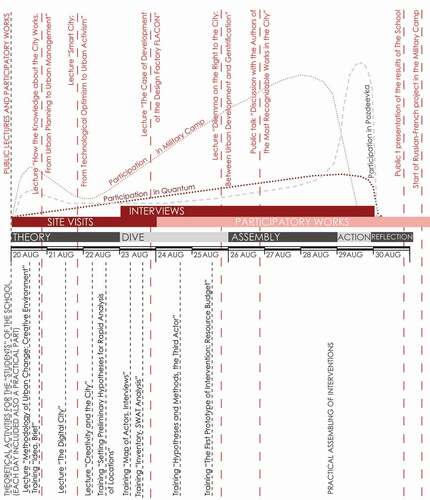

To summarise the process, the School comprised four activity blocks (illustrated in ):

Theory, with the set of theoretical events and training;

Dive, which included additional data collection and interviews, involving partners and stakeholders;

Assembly, which involved reaching agreement on one of the possible scenarios of development, formulating a hypothesis and preparing an intervention; and

Action, which assumed practical intervention at the location.

The School was enriched and followed by reflection sessions, and the analysis of results. The Project culminated in two public presentations.

Study areas

Within the city of Krasnoyarsk, three locations were selected for the School (). All three are historic areas, but none are included in the official list of the city’s heritage areas or ‘memorials’. All three locations were of significant interest either for developers or local stakeholders. All contained controversies in the history of their development and in their dominating narratives.

The three locations were selected based on the following criteria:

Compliance with the main theme of the School – the historical and cultural memory of the place. Locations were selected which contained many hidden layers and meanings that could be revealed and extracted.

High potential for development, being areas where the future was already under consideration by local authorities, designers and businesses.

The fact that results of interventions could make a significant contribution to the transformation of these places.

Location 1: The ilitary amp

The Military Camp in Krasnoyarsk, initially placed outside the city at the beginning of the twentieth century (Bykonya Citation2013), but today surrounded by urban development, is a heritage site in danger of demolition and is of specific interest to local developers (). The old military camp originally occupied 150 hectares, but today, after the elimination of its military function and the reduction of the area of its ‘closed territory’, only 10% of the initial area remains inhabited. At the time of the School, the Military Camp was divided into two parts: one part was functioning and consisting of a residential area where the community of former members of a military unit live amongst friends and families; the second part is empty and abandoned and the buildings are degrading. The residential part of the Military Camp is characterised by two- and three-storey red-brick military barracks for officers, as well as barracks for the cadet corps alongside the Mariinskaia Gimnasia for girls (which is still functioning). The place remains open but exists in informal isolation, while the buildings require structural reparation and technical support. Many of the buildings contain details related to their former use, in the form of fireplaces, high ceilings and ‘parade’ entrances, while providing historic evidence within the fabric of historical events and political change.

Figure 3. Military Camp: the map of the overall site (light grey) and the current residential (dark grey) areas. The photographs reflect the site’s current appearance. (Photos and map: Daria Belova).

Many residents still enjoy the place and their apartments and know their neighbours. Yet the new Krasnoyarsk Masterplan completely ignores the social and historical values these residents attribute to their neighbourhood. Local architects have proposed plans for development which were carefully evaluated within the project. Almost without exception, all city architects had proposed public spaces and buildings (museums, studios and shops, restaurants), or a new historical centre, in place of the existing residential units, often ignoring the function and overall logic of the space as well as the social values local people attribute to it.

Location 2: Quantum

The courtyard of Quantum, a former film factory located in the historical city centre, was being used for parking and storage when the School began (). However, the place has a multilayered and controversial history as well as strong potential for development. After the Great Fire of Krasnoyarsk in 1773, the site was used as a cemetery and, in 1798, the wooden All-Holy Church was built here before burning down in 1812. Later, in the nineteenth century, when the city started to grow (Ruzhzhe Citation1966; Bykonya Citation2013), this area of the former urban fringe became the location of important temple complexes and places of trade and recreation. This area was occupied by the new Vsehsvyatskaia (All-Holy) church complex. In the twentieth century, however, Soviet authorities destroyed many churches including Vsehsvyatskaia. Following demolition, during the period of the Second World War, a film factory called Quantum was located here. This was later abandoned and partly damaged and then, in 2004, during rebuilding works, archaeological studies of the church complex were carried out and 400 graves were opened. After 2004, part of the factory was used as a trade centre occupied by various small businesses, but a significant area remained unused. The place was shared between several stakeholders and was poorly managed leaving the site chaotic and fragmented despite its potential as a city centre location and the need to accommodate creative industries and events. For all of these reasons, the place was perceived as an urban void worthy of further investigation.

Location 3: Pozdeevka

At first glance, this location was the simplest (). However, it was important because it represented typical problems for the city. Until after the Second World War, a staple of Krasnoyarsk’s urban fabric was the estate or ‘usadba’ – a village-like type of courtyard-house (Ruzhzhe Citation1966) which, in the 1950s, began to be actively replaced by broadly identical five-storey brick-built multi-family apartment buildings. Consequently, many traditional neighbourhoods were replaced by these Soviet-style blocks, the interior courtyards of which had passageways with undefined areas for which nobody took responsibility and were thus often uncomfortable and empty. One of these courtyards became the location for the School. It was once the location of an art school, named after the famous Krasnoyarsk artist Pozdeyev Pozdeevka (Nazanskii Citation2011).

Outcomes

Each team selected one of a range of possible development scenarios for their study site and, working with stakeholders, residents and inhabitants, collaboratively created a temporary installation, as well as a series of events which aimed to test the potential applicability and impacts of their selected scenario. The teams were committed to engaging with the largest number of partners and raising collaborative funds, along with broadening awareness about the site and creating or strengthening a sense of local community.

Team 1 dealt with the Military Camp, their selected scenario involving the development of public space within the collectively used location of the residential area. The scenario partly corresponded with the idea to transform the residential neighbourhood into a second historical city core, increasing accessibility for the public. Participants formulated the social hypothesis:

‘If, collaboratively with residents, we can organize a temporary public space and series of events which unite people through shared memories, we will bring people together and start the process of strengthening social relations and traditions, anchoring them within the public space. This can open the possibility of creating a permanent public space based on the partnership of residents and external actors.’

The intervention was inspired by the model of the ecomuseum (e.g. Corsane et al. Citation2007; Davis Citation2011) and specifically the idea of in situ conservation and interpretation: that live heritage sites shouldn’t be conserved or museumified in the classical sense, but rather interpreted and managed by local communities on the basis of internal agreement and negotiations with external actors to strengthen the local economy, aid local identity and improve lives.

The inhabitants of the Military Camp were initially easy-going and friendly: some invited guests, told stories and took guided tours. The team cleaned the courtyard area between two houses with the participation of local residents. The courtyard had been previously landscaped by the residents, including planting the trees which surrounded it. Some participants found an original door which they restored together with the residents. The door then became an art-object covered with the written stories of citizens both by attaching text in envelopes and by writing directly onto its surface. By saving the door and using it as a ‘message board’, the participants drew attention to the value of historic artefacts while exploring the metaphor of ‘opening up’. Historically, street dinners and cinemas were normal practice when the territory functioned as a military camp. Participants organised a meal to restore the ‘dinner’ and street cinema traditions. People also gathered to project old photographs, collected during the interviews, onto the wall of a historic house. Collected artefacts were presented to the local ‘Victory Memorial’ museum, which promised to make regular excursions into the Military Camp (). The interventions made maximum use of the residents’ resources. The activities were then continued by one of the projects of the Krasnoyarsk Biennale, curated by the French artist Bertrand Gosselin in his public participatory wooden sculpture ‘Arches-stairs’ (http://mira1.ru/news/2636).

The Military Camp is a complex location which was intensively researched before the School. However, the intervention presented a result contrary to expectations: while there was some significant participation, most residents ignored the final event. The School revealed the existence of a community whose neighbourhood was spread across the area, encompassing courtyards and their adjacent territories which appeared inherently private. The preparation for interventions revealed strong narratives of people’s individual territories and generally citizens appeared ready to collaborate and communicate yet they protected their privacy and identity. Works involving the French artist, which participants planned to make public, are now abandoned and feel alien, even though residents participated in the process and offered the use of their garages, instruments and storage facilities. It would appear that residents were ready to invite guests, but not ready to allow outsiders to control their space. It seemed impossible to transform the semi-private and semi-public spaces controlled by communities of the Military Camp into public ones, open to the whole city, with a characteristic of centrality.

In summary, the intervention was perceived by residents as an aggressive intrusion to their private spaces and was therefore met with strong resistance at the final stage. Nonetheless, this intervention was successful in illustrating the various ways of defining the historic environment and demonstrating the necessity of experimentation before more radical and permanent interventions are made.

Team 2 dealt with Quantum, the courtyard of a former film factory, selecting the scenario of developing a creative art-residence on the basis of the existing narratives of place. The Team formulated the social hypothesis:

‘If we introduce the residents of different workshops to each other, we will make an internal creative community, showing the site’s history through events, and create new mutually beneficial relationships, which will enhance the cultural and economic value of place and lead to the transformation of the courtyard from a technical space to a public space.’

Participants decided to begin the popularisation of the difficult history of this place through the most recent and positive step: the factory of film and photographic paper. Participants, together with the most active stakeholder-representatives currently working at the site, created both a photo exhibition, based on technological principles of analogue photography and a place to rest and to enjoy the exhibition within the courtyard, taking temporary occupation of what are usually parking spaces. Thus, the participants aimed to demonstrate the potential of the parking area to become a public space. Photographs represented the scenes of creative work within the workshops. The current workers and stakeholders were invited to the opening event. During the intervention, participants collected opinions and feedback. The exhibition aimed at revealing memories of the film factory ().

Figure 7. Photographs illustrating the intervention at the former film factory. (Photos: Daria Belova).

The intervention at Quantum enjoyed less popularity than expected although the idea of a creative art-cluster was supported by the stakeholders. Currently, the art-cluster is inhabited by many creative industries and continues to grow. At the same time, historical memories, which the Team wanted to introduce, evaporated after the intervention.

Team 3 dealt with Pozdeevka, the selected scenario of development assuming the prospective creation of a semi-private courtyard for residents limiting transit through the yard. Participants formulated the social hypothesis

‘If, collaboratively with residents, we organize cultural and artistic events, we can: popularize the memory of the artist Pozdeev, introduce and unite residents in the community, and socially and culturally integrate the art school into the community of the semi-private yard’.

During the series of preparatory workshops, elements of the street furniture were built and painted in the style of Pozdeev’s work, involving residents and potential partners in the process, including the art school and local businesses. A final dinner and social event for children closed the series of workshops: traditional food was cooked within the courtyard, while the large moveable sculpture of a cat (), inspired by the motifs of pictures by the artist, attracted attention alongside a playground for children composed of donated toys. Artists from the art school participated in the dinner and sketched portraits of the citizens, organising a dynamic exhibition. Participants placed a large outline picture of Pozdeev on the wall of the electro-station so that citizens could colour it in.

The intervention of the Pozdeevka group proved to be popular, being visited by more than 70 people at one time whereas, before the intervention, the inhabitants of the yard were largely inactive in terms of public engagement. The final event was successful largely due to the participation of local stakeholders and businesses. Many potential partners and stakeholders were introduced to one another. The school re-established the artist’s name in the symbols and visual motifs around the yard, and gave the location new meanings and a new identity. Some of the created artefacts are still alive. However, the newly-established atmosphere did not last long: the intervention showed its social ineffectiveness in the long term presumably because it didn’t attract many residents, being largely based on the efforts of local businesses.

Discussion

The word ‘intervention’, which inspired the name of the School, is itself widely used in architectural and arts practice. Various art interventions and installations, such as ‘Happy City Birds’ (https://thomasdambo.com/happy-city-birds), ‘Wanderbaumallee Stuttgart’ (Wanderbaumallee-stuttgart.de), etc. together constitute well-known and ‘working’ forms of contemporary arts practice. They are often made as a manifesto to inform, question or promote important changes in life. Sometimes they take the form of a provocation. For example, the RAAAF ([Rietveld Architecture-Art-Affordances] practice for visual art and experimental architecture) group was focused on ‘making artistic interventions that allow visitors to experience what it would be like to live in entirely different ways’ (https://www.raaaf.nl/en/). They call for change, working with affordances – ‘possibilities for action provided by the living environment’ (https://www.raaaf.nl/en/). The group also operates within the heritage sphere, questioning policies in cultural heritage (e.g. cut-through monument Bunker 599; Still Life for Het HEM, a former bullet factory and a place for contemporary art in Amsterdam (https://www.raaaf.nl/en/)).

The organisers of the School were inspired by these examples. However, the School stands alone in several aspects. First, it focused not so much on the provocative and artistic value of interventions as on their ability to delicately and non-destructively explore the historic environment for hidden meanings and values, acting as a research tool. Second, it tested the possibility of implementing more radical pre-programmed scenarios of development. Third, the initiator of the interventions (whether architect, artist, etc.) in this case acted not as leading author, but rather as mediator in a dialogue with stakeholders and communities, at the same time trying to teach this role to interested activists so that they could initiate similar practices in the future. This created an important component of the School: replicability – to develop a co-creative approach which gave others the capacity to design exercises without the necessity for expert involvement. Finally, the results of these socially inclusive interventions sought to inform future architectural projects of ways to preserve narratives and local meanings, adding new layers to old. The School of Urban Interventions thus embodied a new method of collaborative experimentation which recognises heritage as being central to community engagement, both as a field of practice and an area of critical enquiry where past, present and diverse futures come into play.

The School in Krasnoyarsk succeeded in demonstrating how such interventions could serve as a research tool, using collaborative experimentation to identify a location’s potential to accommodate change. The results of interventions in the Military Camp were of particular interest. These demonstrated that any scenarios involving the organisation of public spaces and buildings in a residential area, and specifically the organisation of a second historical centre (as planned by local architects), risked destroying the existing environment and the values local people attach to it, making the space sterile and gentrified. Thus, even professional projects involving experienced architects conducting preliminary research, risked failing without careful non-destructive experimentation and collaborative, discursive gradual developments, recognising the value of not just buildings, but the environment as a whole. As one of the possible methods of developing such places, and as previously stated, the parallel of the eco-museum was relevant (Corsane et al. Citation2007; Davis Citation2011), and specifically the in situ conservation, interpretation and sustainable development of heritage sites by the local community, based on negotiation and agreement.

Urban environments exist in tight connection with communal memories. The sustainability of historic areas largely depends on the resilience of communities, their sense of belonging and responsibility and their connection with the environment. This experiment demonstrated a lack of connection between urban practitioners, citizens and historic areas and the need to establish these connections. Generally, the more diverse the environment and the values people attach to it, the more gentle and iterative the approaches to development should be to sustain values and build trust.

A further question concerns the people in Krasnoyarsk and their preparedness to be active and empowered in taking care of their historic environment. When the period of intensive group fieldwork and the preparation of the interventions took place, experts were in touch with participants almost around the clock, helping to solve problems, requiring constant revisions to the plan of the event. There were conflicts within teams and commands were temporarily collapsed. Yet there were some positive signs. Participants from different teams helped each other with resources and personal involvement. Participants also worked around the clock, demonstrating a collaborative potential often absent from everyday life.

Research interventions provided a necessary set of information about locations, which would be unattainable without experiments that provoked certain social reactions to people’s local environments. Additionally, in the process of data collection, a significant number of old photographs, stories, historical facts, narratives and personal artefacts, which are linked with the areas’ history and culture, was collected. When it comes to further implementation of the results of the School, all the research data (an array of interviews, observation protocols, documents and artefacts, which were obtained during the interventions) were used to create research reports and exhibition materials which were presented in the Krasnoyarsk Book Culture Fair. Additionally, the results will be used in the research and study programmes in the Institute of Architecture and Design in the Siberian Federal University. New competencies of the participants will also be applicable in further heritage projects, research and activism. Some participants will make exhibitions and excursions to sustain the effects of interventions. The School also helped to integrate the university into the life of the city and allowed students to work with real situations, which had a positive impact on the results of their own projects. The School was widely publicised, which increased awareness of the historic sites and the issues associated with them.

The School is one of very few cases in Siberia to have experimented with participation. The School’s purpose was primarily to empower activists to work with communities, while dealing with difficult heritage to simultaneously inform people about its value and collect data for future projects. Thus, the absence of a comprehensive result is not considered a failure and many positive results were achieved. The active interest of participants constitutes a success as well as the fact that participants were consistently engaged during all ten days. Public lectures attracted large audiences.

However, it is also important to discuss failures on the community level, including the issue of non-participation (e.g. Bradby and Stewart Citation2020; Harper Citation2020). As Harper Citation2020, 12) has said, ‘[d]etermining, from the outside, whether participation has effectively taken place, and whether it has been “good”, “passive” or “manipulated” may risk false judgments through incomplete awareness of competing local narratives or political agendas’. The main omission in this case was that the organisers did not set performance parameters for successful participation within each case. Without these, and without the deep understanding of each community, it was difficult to judge the quality of participation. Harper posed the question: ‘Is it really a failing to not want to participate or could it be seen, in certain contexts, as an affirmation of agency, a demand for something different?’ (Harper Citation2020, 3). Non-participation in public interventions can be interpreted as a manifesto, for instance, with ‘isolation … a defense against incoming gentrification’ (Harper Citation2020, 12).

In the case of the Military Camp, the involvement of communities turned out to be especially valuable at the stage of collecting information and first conversations. It was at the final stage that non-participation took place. As Bradby and Stewart Citation2020, 13) have claimed: ‘[A]s so often happens with participatory projects, community involvement ended when the show moved on’. The ending of participation can represent a poor strategy of participation. Thus, the excessive contribution of students, who arranged a successful show together with business representatives, might be the reason for the non-sustainable effect of the Pozdeevka intervention. The format of the event did not allow for the non-participation of residents. In these situations, ‘failure becomes simultaneously inevitable and impossible’ (Bradby and Stewart Citation2020, 3).

In terms of research questions, The School of Research Interventions demonstrated its potential to serve both as a method of sense-retrieval and of collaborative experimentation, which can non-destructively, gently and collaboratively, test possible scenarios of future permanent interventions. However, its potential to provide sustainable community-based developments and heritage impacts requires assessment over the longer term. A lack of impact now does not necessarily mean the lack of any longer-term legacies.

With regards to the theoretical framework, the School showed that the current scientific trend towards addressing a variety of socially-constructed scenarios, actors and opinions is recognised as helpful at local scale and can be applied to urban heritage in Krasnoyarsk. Further, the idea of ‘spontaneous consciousness’ or adapting to inherited civil substance while dealing with historical areas, can be introduced through participatory research and design during the process of consensual negotiations. In summary, this project has proposed an experimental method strategically derived from previous interventions but adapted to meet local needs, forming an effective and translatable interface between theory and practice.

Conclusion

The twentieth century was a period of discontinuity in the development of urban areas in Russia, the process of change being reinforced by changes of ideology impacting the overall logic of spatial development. This process has been disorienting for residents. It was this process of change that formed a focus of this project. The School revealed and promoted the inscribed values of unobvious or everyday urban heritage, such as old factories, military towns, vernacular regions, etc. It also informed citizens about historical landscapes and taught local activists how to help people to engage with their local area. Over the long-term, this approach has the potential to address the lack of connectivity between people and their neighbourhoods, especially where different people hold values that are contradictory. The method allowed hypotheses and design solutions to be tested before permanent interventions while revealing the potential in citizens to influence change.

Unobvious, not-listed, ‘everyday’ urban heritage, sometimes representing a difficult or personalised view of the past, usually goes unprotected yet forms an important part of the city’s identity and of its residents. Recognition of this unobvious heritage therefore needs to be developed. The School succeeded in testing some research tools to delicately, non-destructively and collectively begin to reveal these hidden meanings and values and to test the impact of proposed development scenarios using socially inclusive methods. Participatory activities helped to define the social borders of neighbourhoods, clarify morphologies of the place from social perspective and reveal those historically-assembled compositions of public and private areas, stories, narratives, traditions and collective memories, which characterise neighbourhoods.

As Hillier (Citation1997, 7) argues: ‘attempts to support designers by building methods and systems for bottom-up construction of designs must eventually fail as explanatory systems. They can serve the purpose of creating specific architectural identities, but not to advance general architectural understanding’. Following this argument, the methods of bottom-up or grounded construction are not a panacea but rather should be understood in combination with other analytical and design theories, which could be introduced into future experiments. Examples might include urban morphology (e.g. Maretto Citation2014; Caniggia and Maffei Citation2001; Hillier Citation1997) and the mapping of social structures, informed by actor-network theory (Latour Citation2011).

According to Chirikure et al. (Citation2010, 41), ‘community participation is not an event but a process which evolves over time’. The important aspect of this project is that it did not merely initiate the bottom-up activities and practices, but taught activists to initiate them. However, challenges, including the discussion of different voices within communities, social inequality, issues of responsibility, economic effects, data sharing and gentrification also need to be considered.

Managing change and balancing heritage priorities with social and economic drivers (the very definition of a sustainable approach), presents one of the greatest challenges to those responsible for heritage management. A directly related challenge is understanding what people think about their local area and the often conflicting values they attach to it. What do they wish to retain, what are they prepared to let go, and what is tradeable? Here we present a replicable methodology which creates the opportunity for a combination of dialogue and practical interventions that give voice to local residents. In this paper, we have promoted the advantages of taking an experimental approach in which co-creative practices involve developing and testing ideas, recognising that these ideas can be a positive force whether their implementation is a success or not. In this way urban landscapes become, in the words of Jacobs (Citation1992 [1961], 6) ‘laboratories of trial and error, failure and success’.

Acknowledgments

Daria Belova would like to take this opportunity to thank all of the participants of this project, for their time and commitment. Special gratitude is given to Pyotr Ivanov, Maria Bystrova and Vadim Pirogov for their cooperation in organising the event, and to the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation for their financial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. As World Heritage Sites for example, where particular planning constraints might apply throughout the city, or through statutory protection (e.g. as Conservation Areas, as in the UK).

2. This aligns with current thinking on heritage futures (e.g. Harrison et al. Citation2020; Holtorf and Högberg Citation2021).

3. After e.g. Watson and Waterton Citation2010; Waterton and Watson Citation2015; Locke et al. Citation2018; Šćitaroci et al. Citation2019. Approaches include: Do It Yourself (DIY) and DIT – (do-it-together) urbanism (Gella Citation1999; Douglas Citation2014), ‘austerity urbanism’ (Tonkiss Citation2013), ‘heritage urbanism’, etc., as well as collaborative and use value-oriented approaches which require shared responsibility and self–empowered collaborators.

4. Examples of this include: information technologies in participatory heritage (e.g. Salerno Citation2014; Monteiro, Painho, and Vaz Citation2015; Hong et al. Citation2017; Zhang Citation2017; van der Hoeven Citation2020); human rights approaches (e.g. Blake Citation2013; Baird Citation2014) and cultural discussions around values-based approaches (Poulios Citation2010; Labadi Citation2013; Torre Citation2013; Turner and Tomer Citation2013; Fredheim and Khalaf Citation2016; Buckley Citation2017); a critique of official discourse, policies, agencies, and doctrines (Pendlebury and Townshend Citation1999; Smith Citation2006; Deacon and Smeets Citation2013; Mualam and Alterman Citation2018); the problem of economic development (Hampton Citation2005); and the role of the architect (Awan, Schneider, and Till Citation2011).

5. Examples include but are not confined to: Sanoff Citation2000; Gard’ner Citation2004; Lewicka Citation2008; Barelkowski Citation2009; Abu-Khafajah Citation2010; Chirikure et al. Citation2010; Crooke Citation2010; Greer Citation2010; Grydehøj Citation2010; Prangnell, Ross, and Coghill Citation2010; Mitchell et al. Citation2013; Kankpeyeng, Insoll, and Maclean Citation2014; Mackay and Johnston Citation2014; Stephens and Tiwari Citation2015; Yung, Lai, and Yu Citation2016; Jang, Park, and Lee Citation2017; Onciul, Stefano, and Hawke Citation2017; Sontum and Fredriksen Citation2018; Jones et al. Citation2018;; Cizler and Soriani Citation2019.

References

- Abu-Khafajah, S. 2010. “Meaning-Making and Cultural Heritage in Jordan: The Local Community, the Contexts and the Archaeological Sites in Khreibt Al-Suq.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 123–139.

- Awan, N., T. Schneider, and J. Till. 2011. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. New York: Routledge.

- Baird, M. F. 2014. “Heritage, Human Rights, and Social Justice.” Heritage & Society 7:2: 139–155.

- Barelkowski, R. 2009. “Involving Social Participation in the Preservation of Heritage: The Experience of Greater Poland and Kujavia.” WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 122: 435–446.

- Blake, J. 2013. “Taking a Human Rights Approach to Cultural Heritage Protection.” Heritage & Society 4:2: 199–238.

- Bradby, L., and J. Stewart. 2020. “Drumming up an Audience: When Spectacle Becomes Failure.” Conjunctions Transdisciplinary Journal of Cultural Participation 7: 2.

- Buckley, K. 2017. “2013 UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value: Value-Based Analyses of the World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage Conventions Book Reviews.” Heritage & Society 9:2: 191–194.

- Bykonya, G. 2013. Krasnoyarsk: Ot Proshlogo K Budushcemu. [Krasnoyarsk: From past to Future]. Krasnoyarsk: Rastr.

- Caniggia, G., and G. L. Maffei. 2001. Architectural Composition and Building Typology: Interpreting Basic Building. Florence: Alinea.

- Chirikure, S., M. Manyanga, W. Ndoro, and G. Pwiti. 2010. “Unfulfilled Promises? Heritage Management and Community Participation at Some of Africa’s Cultural Heritage Sites.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 30–44.

- Cizler, J., and S. Soriani. 2019. “The Role of Bottom-up Initiatives in Waterfront Development in Venice, Italy Case Study: The Venetian Arsenal.” Sociologija I Prostor 57 (3): 229–251.

- Corsane, G., P. Davis, S. Elliott, M. Maggi, D. Murtas, and S. Rogers. 2007. “Ecomuseum Evaluation: Experiences in Piemonte and Liguria, Italy.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 13 (2): 101–116.

- Council of Europe, 2009. Heritage and Beyond. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: rm.coe.int/16806abdea

- Crooke, E. 2010. “The Politics of Community Heritage: Motivations, Authority and Control.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 16–29.

- Dalla Negra, R. 2015. “L’intervento contemporaneo nei tessuti storici.” U+D_urbanform and Design 03/04: 10–32.

- Davis, P. 2011. Ecomuseums: A Sense of Place. London: Continuum.

- de Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. London: University of California Press.

- Deacon, H., and R. Smeets. 2013. “Authenticity, Value and Community Involvement in Heritage Management under the World Heritage and Intangible Heritage Conventions.” Heritage & Society 6:2: 129–143.

- Douglas, G. C. C. 2014. “Do-It-Yourself Urban Design: The Social Practice of Informal “Improvement” through Unauthorized Alteration.” City & Community 13 (1): 5–25.

- Drury, P., A. McPherson, and E. Heritage. 2008. Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment. London: English Heritage.

- Dunne, A., and F. Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything. Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. London: MIT Press.

- Franqueira, T. 2007. “Reshaping Urban Lives-Design as Social Intervention Towards Community Networks”. Presented at IASDR 07 (International Association of Societies of Design Research): Emerging Trends in Design Research. Hong Kong: School of Design, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, November, 1–25.

- Fredheim, H.L., and M. Khalaf. 2016. “The Significance of Values: Heritage Value Typologies Re-Examined.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (6): 466–481.

- Gard’ner, J. M. 2004. “Heritage Protection and Social Inclusion: A Case Study from the Bangladeshi Community of East London.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 10 (1): 75–92.

- Gella, E. I. 1999. Sredovoi Podhod i Programmy Uchastiia v Arkhitekture [Environmental Approach and Participation Programs in the Architecture of I960-90th.] PhD diss., Kharkiv State Technical University of Construction and Architecture.

- Gevel, E. 2012. Image of the City in the Krasnoyarsk Urochische.Krasnoyarsk. LAD.

- Greer, S. 2010. “Heritage and Empowerment: Community-Based Indigenous Cultural Heritage in Northern Australia.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 45–58.

- Groat, L., and D. Wang. 2013. Architectural Research Methods. Wiley.

- Grydehøj, A. 2010. “Uninherited Heritage: Tradition and Heritage Production in Shetland, Åland and Svalbard.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 77–89.

- Hampton, M. 2005. “Heritage, Local Communities and Economic Development.” Annals of Tourism Research 32 (3): 735–759.

- Harper, S. J. 2020. “Redefining Failure.” Conjunctions. Transdisciplinary Journal of Cultural Participation 7: 2.

- Harrison, R., C. DeSilvey, C. Holtorf, S. Macdonald, N. Bartolini, E. Breithoff, H. Fredheim, et al. 2020. Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices. London: UCL Press.

- Hillier, B. 1997. Space Is the Machine. Vol. 18. London: UCL.

- Hoeven, A. V. D. 2020. “Valuing Urban Heritage through Participatory Heritage Websites: Citizen Perceptions of Historic Urban Landscapes.” Space and Culture 23 (2): 129–148.

- Holtorf, C., and A. Högberg, eds. 2021. Cultural Heritage and the Future. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hong, M., J. J. Jung, F. Piccialli, and A. Chianese. 2017. “Social Recommendation Service for Cultural Heritage.” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 21 (2): 191–201.

- Jacobs, J. 1992 [1961]. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Jang, M., S.-H. Park, and M.-H. Lee. 2017. “Conservation Management of Historical Assets through Community Involvement. A Case Study of Kanazawa Machiya in Japan.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 16 (1): 53–60.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37.

- Jones, T., A. Mozaffari, J. M. Jasper, and T. Jones. 2018. “Heritage Contests: What Can We Learn from Social Movements?” Heritage & Society 10 (1): 1–25.

- Kankpeyeng, B. W., T. Insoll, and R. Maclean. 2014. “The Tension between Communities, Development, and Archaeological Heritage Preservation. The Case Study of Tengzug Cultural Landscape, Ghana.” Heritage Management 2:2: 177–197.

- Kindon, S., R. Pain, and M. Kesby, eds. 2007. Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place. London and New York: Routledge.

- Labadi, S. 2013. UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value: Value-Based Analyses of the World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage Conventions. AltaMira Press.

- Latour, B. 2011. “Networks, Societies, Spheres: Reflections of an Actor-Network Theorist.” International Journal of Communication 5: 796–810.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Blackwell. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith.

- Lewicka, M. 2008. “Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28: 209–231.

- Locke, R., M. Mehaffy, T. Haas, and K. Olsson. 2018. “Urban Heritage as a Generator of Landscapes: Building New Geographies from Post-Urban Decline in Detroit.” Urban Science 2 (3): 92.

- Mackay, R., and C. Johnston. 2014. “Heritage Management and Community Connections — On the Rocks.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 16 (1): 55–74.

- Maretto, M. 2014. “Perché La Morfologia Urbana?” [Why Urban Morphology?] U+D_urbanform and Design 1 (1): 62–63.

- Mitchell, M., D. R. Guilfoyle, R. D. Reynolds, and C. Morgan. 2013. “Towards Sustainable Community Heritage Management and the Role of Archaeology: A Case Study from Western Australia.” Heritage & Society 6:1: 24–45.

- Monteiro, V., M. Painho, and E. Vaz. 2015. “Is the Heritage Really Important? A Theoretical Framework for Heritage Reputation Using Citizen Sensing.” Habitat International 45 (P2): 156–162.

- Mualam, N., and R. Alterman. 2018. “Social Dilemmas in Built-Heritage Policy: The Role of Social Considerations in Decisions of Planning Inspectors.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 33 (3): 481–499.

- Nazanskii, V. 2011. “Pozdeev’s Phenomena”. Dialogues of Arts, December 27. Available online at: https://di.mmoma.ru/news?mid=2669&id=1110 (accessed 11 November 2021

- Onciul, B., M. L. Stefano, and S. Hawke. 2017. Engaging Heritage, Engaging Communities. Boydell Press.

- Pendlebury, J., and T. Townshend. 1999. “The Conservation of Historic Areas and Public Participation.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 5 (2): 72–87.

- Poulios, I. 2010. “Moving beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 12 (2): 170–185.

- Prangnell, J., A. Ross, and B. Coghill. 2010. “Power Relations and Community Involvement in Landscape-Based Cultural Heritage Management Practice: An Australian Case Study.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 140–155.

- Rowe, C. 1996. “Program versus Paradigm Otherwise Casual Notes on the Pragmatic, the Typical, and the Possible.” In As I Was Saying: Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays, 7–41. MIT Press.

- Ruzhzhe, V. L. 1966. Krasnoyarsk: Voprosy Formirovaniia I Razvitiia. [Krasnoyarsk. Issues of Formation and Development]. Krasnoyarsk: Krasnoyarsk Book Publishing.

- Salerno, I. 2014. “Sharing Memories and “Telling” Heritage through Audio-Visual Devices. Participatory Ethnography and New Patterns for Cultural Heritage Interpretation and Valorisation.” Visual Ethnography 3: 2.

- Sanoff, H. 2000. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. Wiley.

- Šćitaroci, O., B. Mladen, B. O. Šćitaroci, and A. Mrđa, eds. 2019. “Cultural Urban Heritage.” Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sontum, K. H., and P. D. Fredriksen. 2018. “When the past Is Slipping. Value Tensions and Responses by Heritage Management to Demographic Changes: A Case Study from Oslo, Norway.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (4): 406–420.

- Stephens, J., and R. Tiwari. 2015. “Symbolic Estates: Community Identity and Empowerment through Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (1): 99–114.

- Stepin, V. S., V. G. Gorochov, and M. A. Rozov. 1999. Filosofiia Nauki I Techniki [Philosophy of Science and Technics]. Gardariki.

- Tonkiss, F. 2013. “Austerity Urbanism and the Makeshift City.” City 17 (3): 312–324.

- Torre, M. D. 2013. “Values and Heritage Conservation.” Heritage & Society 6:2: 155–166.

- Turner, M., and T. Tomer. 2013. “Community Participation and the Tangible and Intangible Values of Urban Heritage.” Heritage & Society 6:2: 185–198.

- Walker, M., and P. Marquis-Kyle. 2004. The Illustrated Burra Charter: good practice for heritage places. Burwood, Australia: Australia ICOMOS.

- Waterton, E., and S. Watson. 2015. The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Watson, S., and E. Waterton. 2010. “Heritage and Community Engagement.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 1–3.

- Yung, E.H.K, L. W. C. Lai, and P. L. H. Yu Yung, E.H.K., L.W.C. Lai, and P.L.H. Yu. . 2016. “Public Decision Making for Heritage Conservation: A Hong Kong Empirical Study.” Habitat International 53: 312–319.

- Zachary, D., and S. Dobson. 2020. “Urban Development and Complexity: Shannon Entropy as a Measure of Diversity.” Planning Practice & Research 36 2 (2021): 157–173.

- Zhang, X. 2017. “Conversation on Saving Historical Communities: A Participatory Renewal and Preservation Platform”. Presented at IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 245, no. 8: 1–11.