ABSTRACT

Chinese opera, a sing-song storytelling art form predominantly associated with rural and urban migrant communities, currently has over 300 regional styles. This paper investigates the intertwined development of a regional Chinese opera Shanghai All-female Yueju and its main audience, the Shanghai female textile workers and their omission in Shanghai Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) making. Utilising theories of ‘selective memory’ and ‘strategic forgetting’, this paper argues that the official construction of Shanghai semi-colonial heritage as Shanghai’s post-industrial identity and the omission of textile Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) is not only an attempt to establish a global cosmopolitan image, but also a strategy to deal with the post-industrial trauma of compulsory female workers’ redundancy and painful community dissemination. It suggests that, until Shanghai fully acknowledges its ‘dark heritage’, the discourse of CCI lacks context and Shanghai local community continues to experience alienation and their opera form struggles for expression. The paper highlights the urgency for China, as well as globally, to safeguard and implement UNESCO’s vision in promoting ICH as a key vehicle for social inclusion and sustainable development.

Introduction

Since the turn of the 21st century, the term Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) has spread globally as a post-industrial strategy for socio-economic revival. UNESCO has been the driving force in promoting both tangible (building site, machineries, fabric etc.) and intangible cultural heritage (ICH) (music, songs, storytelling etc.) for CCI development. Support for ICH-led CCI development are two main reasons: first, for place making, historical roots and cultural identities are crucial in guiding not only the community but also the city image; and second, the so-called city of the third wave, which is content powered digital economy (Moghadam and Bagheritari Citation2007; Scott Citation2011; Kurin Citation2014; Jeannotte Citation2016). The UNESCO (Citation2003) ICH Convention emphasises the process of oral traditions and expressions, performing arts, social practices, rituals and festive events as key in ‘passing on collective memory, creating places of memory for communities of origin and a wider audience for economic as well as social impact’ (UNESCO Citation2003).

Shanghai Textile Industry, known as China’s Mother Industry, has been the spearhead in Shanghai CCI post-industrial transformation with abundant textile heritage sites being turned into creative clusters and rebrand Shanghai as the UNESCO Creative City of Design. This paper takes Shanghai M50 Contemporary Arts Cluster, the very first Shanghai textile heritage site turned creative cluster as a case study, to examine the missing historical textile female workers and their art form Shanghai All-female Yueju in the making of Shanghai CCI. Previous researches have focused on Shanghai M50 as the symbol of China’s successful transformation from ‘Made in China’ to ‘Created in China’ with no reference made to its ICH female textile workers and their art form, Shanghai All-female Yueju. This paper inserts the missing textile ICH into M50ʹs ‘gentrified shell’ and highlights the ongoing struggle and urgency in safeguarding ICH-led CCI expansion in China, and globally.

China CCI through ICH

On 11 October 2000 China officially sanctioned the term Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) at the 15th Communist Party Central Committee and has since adopted CCI as its national policy and a pillar economy. Major investments in the early stage have focused on the establishment of ‘creative industry zones’ across the country, compatible with the global process of urbanisation and industrial transformation (Zhu Citation2007; Keane Citation2009; Sun Citation2016). Shanghai, being China’s ‘Head of the Dragon’ and its abundant Textile Industry heritage has been taken the leadership in China post-industrial city redesign and CCI development. Shanghai’s long-term ambition is to become the most influential CCI centre in Asia in 10–15 years, and the leading CCI hub globally in 25 years, with focus placed on digital technology (Wu Citation2004; Keane Citation2009; Wang Citation2011; O’Connor and Gu Citation2014; Gong and Hassink Citation2017; Arkaraprasertkul Citation2019).

However, how to adapt CCI, a discourse derived from the Global North countries in response to the decline of Western post-industrial cities and working-class community’s regeneration requires a careful approach on China’s part. A historically agricultural society, China’s urban population only tipped over 50% in the mid-2010s, and it announced a total rural poverty eradication in February 2021 (National News Net Citation2021). China’s marketisation since the early 1980s has achieved remarkable results but its developmental challenges remain centred around rural-urban disparity and rural migrant socio-cultural settlement in urban cities. To design a suitable CCI model will assist China’s ambition in the global eco-political power restructuring but also to ensure the very survival of legitimacy of the one party Communist rule.

China’s abundant ICH resources provide an alternative CCI model and lead its full support in implementing the UNESCO (Citation2003) ICH Convention. In 2004, China was amongst the first nations to ratify the UNESCO (Citation2003) ICH Convention, and by 2017 China has 47 UNESCO listed ICH and over 900,000 identified ICH (China ICH Net Citation2021). The 2013 Hangzhou Congress, which was the first international congress specifically focusing on the linkages between culture and sustainable development organised by UNESCO since the Stockholm Conference in 1998, was hosted in China (Hangzhou Citation2013, UNESCO Citation2013). In 2018, China merged its Culture Bureau and Tourist Bureau, clearly inspired by the 2005 joint declaration made by the UN, the World Tourism Organization and the Ministry of Tourism, asserting cultural tourism as a crucial move for alleviating poverty, further support UNESCO’s vision in promoting culture as a key strategy in addressing the world’s most pressing developmental challenges, such as sustainability, poverty and social inclusion. Xi JinpingFootnote1‘s 2014 inaugural speech emphasised that ‘China’s future CCI anchors in traditional Chinese culture’ (Xinhua News Agency Citation2015). China recognises ICH as its rich regional CCI resource and global soft power insertion.

Chinese opera, collectively known as Xiqu,Footnote2 a synthetic theatrical art form consists of literature, music, singing, dancing and drama of 348 regional forms (China ICH Net Citation2021) occupies a unique position in China ICH. The very first UNESCO ICH recognition China received was Kunqu, the oldest regional opera form dating back over 600 years and was awarded by UNESCO as ‘a masterpiece of oral and intangible heritage’ in 2001. In 2006, the year when the 2003 UNESCO ICH Convention took effect in China, many regional opera forms were given national ICH status. In Shanghai alone, four obtained ICH status: Shanghai Kunqu, Shanghai Jingju, Shanghai Huju and Shanghai All-female Yueju. By 2021, all 348 regional opera are listed ICH, each represent local community diverse cultural expressions. Despite abundant ICH Chinese opera resources, how to integrate Chinese opera, which is predominantly associated with rural and urban migrant communities’ culture into official CCI narrative construction continues to pose challenges.

The Theoretical Framework: ‘Selective Memory’ and ‘Strategic Forgetting’

Integrating local culture as a way of city branding and municipal planning is not new. Scottish town planner Patrick Geddes back in the early 20th century advocated to ‘excavate the layers of our cities downwards … and thence … read them upwards, visualising them as we go’ (quote in Meller Citation2005, 223). To Geddes, the local cultural aspects of the city consist of the main elements that determine a city’s organic growth. Unfortunately, this holistic perspective fell out of fashion in the 1940s and was replaced by a zone system of urban regulation and planning (Mercer, Citation1997; Rubin Citation2009, 354–357). In the new millennium, a renewed strategy of integrating local culture in city development is increasingly seen as an important step in ensuring a city’s CCI creative source and a local-global distinction.

However, culture-generated place making is never straightforward. The relationship between memory and identity has constantly been in tension and negotiation. Sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (Citation1925/1992) in the early twentieth century articulated the concept of ‘collective memory’ and argued that memory and identity making is often a contradictory process of communicative memory and cultural memory. As communicative memory is related to oral history through an experience between partners, and expands for no more than eighty (at the very most) to 100 years thus, community identity could only be sustained through cultural memory – texts, images, epics, rituals, buildings, and others. Halbwachs points out that collective memory works by reconstruction, and that it always relates its knowledge to an actual and contemporary situation, consisting of ‘which society in each era reconstructs within its contemporary frame of reference’, and this is often done through the institutional buttressing of communication, depending on a specialised practice, a kind of ‘cultivation’. Through reconstruction of communicative memory and cultural memory, a local identity is formed and is defined in a positive ‘this is who we are’ or in a negative ‘this is our opposite’ sense (Halbwachs Citation1925/1992; Schechtman Citation1994; Assmann and Czaplicka Citation1995).

Since the 2010s, a small but rising research on place and community identity has been developed through the theories of ‘strategic forgetting’ to site renaming and recycling heritage sites for post-industrial urban regeneration and property commodification (Luna Citation2013; Bossewitch and Sinnreich Citation2013; Kearns, Joseph, and Moon Citation2015; Pendlebury, Wang, and Law Citation2018; González Martínez Citation2020). Luna’s work (Luna Citation2013), for example, examines old sites being recycled and redeveloped as luxury hotels. The author sees the autonomous reuse implying a total disconnection from previous purpose; memory is sustained only through its exterior fabric with all traces of interior prior function removed; the building itself becomes a ‘shell’ for luxury sale. Pendlebury’s study on Shanghai 1933 (Pendlebury, Wang, and Law Citation2018), a former slaughterhouse turned creative cluster, examines the parasitic reuse of the recycled building, through a process where the new use feeds off of the memory of the building in a more one-sided, less symbiotic way, resulting in a recycled ‘shell’ of architectural distinction and a gentrified site. ‘Strategic forgetting’ in this way has been used to critique the ‘shell’ effect of recycling buildings as being of architectural distinction, with any reference to former use avoided or minimised.

The theories of ‘strategic forgetting’ are derived from Bentham and Foucault’s work on panopticon and surveillance under specific ways of ordering and organising the lives and social activity of humans as well as animals (Foucault Citation1977). The concept of the panopticon being where, under surveillance by guards, the inmates involved in Bentham and Foucault’s work themselves developed a standard behaviour control. In response to the panopticon power and surveillance, a deeper model of psychology emerges in which suppression, repression and the ability to forget are vital aspects of our psychological makeup . This terrain is most often explored in fiction by examining the ways in which loss of memory alters, compromises or threatens personal and social identity. Joseph and Kearns define this as a process of ‘strategic forgetting’ (Kearns, Joseph, and Moon Citation2010; Joseph, Kearns, and Moon Citation2013; Bossewitch and Sinnreich Citation2013). ‘Strategic forgetting’ is associated with ‘dark heritage’, which encapsulates the complexity of the social impact, multifaceted aspects, and politically charged nature of heritage as how and why it impacts the community in the present day (Thomas, Seitsonen, and Koskinen-Koivisto Citation2019, 1). It explores how and why people engage with aspects of cultural heritage that are related to times of conflict, death and suffering. It is argued that individuals’ as well as communities’ identity formation depends upon the function of forgetting, which is a way to cope with trauma and stress (Freud Citation1920/1966; Elliott and Briere Citation1992; Van der Kolk Citation1994; Connerton Citation2008).

Utilising theories of ‘selective memory’ and ‘strategic forgetting’, this paper scrutinises the intertwined development of Shanghai female textile workers and Shanghai All-female Yueju and their omission in Shanghai Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) making. It argues that the official narrative of semi-colonial heritage is not only to construct Shanghai as cosmopolitan city for a local-global distinction, but also a way to deal with post-industrial trauma in response to female worker redundancy, community disintegration and more importantly for China one party-state’s legitimacy and survival.

From ‘Made in China’ to ‘Created in China’: the intertwined fate of Shanghai All-female Yueju and Shanghai Textile Industry

At the Shanghai Textile Museum, a set of red-lettered words refers to Shanghai textile industry as China’s Mother Industry and the symbol of Shanghai modernity. In 1888, the first Chinese mill, Shanghai Machine Weaving Bureau, was set up and by 1894, the fast development of silk filatures and cotton mills, along with other industrial sites made Shanghai China’s largest industrial centre (Honig Citation1986, 16; Fung and Erni Citation2013). Before 1949, there were 4,550 textile factories in Shanghai, occupying 47.23% of China’s total textile industry (Li Citation1981; Zhu Citation2007). The Shanghai textile industry developed mainly along the waterway of the Suzhou Creek, on Moganshan Road, home of today’s Shanghai M50 Contemporary Arts Cluster.

The rise of the Shanghai textile industry required a large influx of labour consisting of young girls recruited mainly from the neighbouring Zhejiang province. There are two reasons for this trend. Zhejiang females traditionally worked as the main labour force in the Zhejiang silk industry and handcraft economy until its decline in the early 20th century, facing the fast-rising Shanghai textile industry. The expansion of the Shanghai textile industry required a large pool of labourers, which was an obvious attraction to Zhejiang women, whilst these women’s experience in the silk industry made them the most desirable group for hiring (Honig Citation1986, 50–55). With capital in hand, Zhejiang factory girls sought out diverse Shanghai cultural commodities, but they favoured their hometown opera Zhejiang Shaoxinxi.

Shaoxinxi is a fusion of Buddhist chanting and folk singing. Across Zhejiang province, locals sang it as a way of life: either during paddy fieldwork to relieve fatigue or to banter for entertainment. Public performance had historically been limited to males, but following China’s New Cultural Movement and the female emancipation in the 1910s and 1920s, women were legally allowed to enter the public spaces. A growing number of professional women and their financial ability to consume culture meant that their taste was catered for. In 1923, the first all-female troupe formed in Zhejiang province entered the Shanghai entertainment world. Its gentle singing tune and unique female cross-dressing male role, which plays exclusively the idealised male who cherishes and loves the unfortunate female protagonist, became an iconic figure and soon attracted the fast-rising female workers beyond the Zhejiang community. The name Shanghai All-female Yueju first appeared in Drama World (Xiju Shijie) in 1938 (Gao Citation1991, 71). By the end of the 1930s, Shanghai All-female Yueju rose to be one of the most popular theatrical forms in Shanghai, standing shoulder to shoulder with Jingju representing China’s first urban female working-class culture (Ma Citation2016; Jiang Citation2011).

The formation of the Shanghai female textile workers and their art form Shanghai All-female Yueju was identified by the then-underground Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as ‘a key force to be absorbed into the revolution’ (Li Citation2015). Support was provided to female artists to develop their scripts and union meetings took place exclusively during Yueju performances, where all female workers were guaranteed to attend. During Mao Zedong’s era (1949–1976), the textile industry and Yueju were handpicked to advance gender equality and exemplify socialist progression. In 1950, months after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, China’s first opera house – the East China Yueju Experimental Troupe – was established. In 1955 it is formally named Shanghai Yue Opera House (Shanghai Yueju Yuan) till this day. By the end of the 1950s, the number of state registered Yueju troupes expanded from a dozen to 113 in Shanghai and 4,647 in Zhejiang (Ying Citation2002, 180–181). There were frequently organised Yueju competitions within textile mills, interacting with professional Yueju troupes, and all performance productions and tickets were fully subsidised. During the first five-year plan (1950–1955), Shanghai industries were relocated across the nation for knowledge transfer, along with Shanghai Yueju troupes to ensure the workers will settle. Between 1956 and 1959, Shanghai Yueju expanded to nearly all the 23 provinces and 5 autonomous regions across China, including Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. By the end of 1965, there were 175 state-owned Yueju troupes across China (Ying Citation2002, 213). Amitin, who conducted research in the late 1970s was extremely impressed by the abundance of cultural productions in factories where all theatre tickets were subsidised, and made a specific reference to the All-female Yueju he attended, where the audiences were fervent’ (Amitin Citation1980).

Until the early 1990s, Shanghai had 500,000 textile workers in a city of 10 million people. ‘Textile female worker’ (fangzhi nvgong) became a distinct phrase in Shanghai as ‘every Shanghai household has family members, neighbours and friends working in the textile industry’ (Jiang Citation2020). Before the factory closure from the mid-1990s, Shanghai textile mills’ loudspeakers religiously played the Shanghai Yueju Love of the Butterfly throughout the day, and everyone sang ‘Lin sister has fallen from the sky (tianshang diaoxiage linmeimei)’, an aria from Shanghai Yueju Dream of the Red Mansion (Shanghai Story Citation2014). Shanghai Yueju forms a collective memory of Shanghai female textile workers and Shanghai community.

In 1994, under the central call of ‘smashing ten million machines nationally (quanguo yading yibaiwan)’, Shanghai as the newly appointed ‘Head of the Dragon’ led the national State Owned Enterprise (SOE) reform. Textile factories were pulled down to make new city landmarks such as the Pearl Tower, and 550,000 female workers were made redundant (Jiang Citation2020). Various retraining programmes were launched to assist the transition. The most famous event was called the Aunt Stewardesses (Kong Sao), when Shanghai Eastern Airlines recruited exclusively from redundant textile workers (Shanghai Story Citation2014). Further attempts were made to absorb the textile workers into a fast-rising service industry: hotels, shopping malls, metros and banking. In reality, these women had little chance to compete with a new migrant labour force – the younger and better-educated female. In the case of the above-mentioned Aunt Stewardesses, only 18 were recruited from the 550,000 redundant textile workers. To compound their misery, the free housing the textile workers once occupied was sold to real estate developers, and occupants were forced to move to the outlying suburbs, where they made do with what little they had (Chen Citation2009). In the new millennium, Shanghai female textile workers, the once Shanghai socio-economic elite class, are now the new urban poor consists of mainly middle aged and elderly women.

Meanwhile, Shanghai entered full speed of marketisation and modernisation. The city has been transformed with textile factories turned into creative clusters, community districts are pulled down to make way for grand theatres and commercial boulevards to attract and cater for the rising new middle class. From 2005, nationwide State Owned Enterprise reform extended to all opera houses and Shanghai Yueju Opera House had state funding withdrawn.Footnote3 What this means is full rental payment for performing in theatre spaces and high price-tagged tickets to justify its value and continued existence. As Yueju’s main audience, the Shanghai textile female workers, have no financial means to enter the glittering theatre and young middle-class desires Western cultural capital rather than community art form of Chinese opera, Shanghai Yueju Opera House has been forced to tour in peripheral and rural regions. By the late 2000s, Shanghai Yueju virtually disappeared from Shanghai official cultural spaces along with its main body audience, the redundant Shanghai textile female workers.

In 2005, Shanghai Chunming (Spring and Bright) Textile Factory renamed itself Shanghai M50 Contemporary Arts Cluster and opened to the public. It soon became the symbol of Shanghai regeneration and gentrification, a successful model of China CCI post-industrial transformation from ‘made in China’ to ‘created in China’. At Shanghai M50, there is no information on the female textile workers nor their art form Shanghai All-female Yueju. The only trace of Shanghai textile ICH is a mural at deep end of the M50 cluster depicting a group of female textile workers smiling at visitors. It is as if the ghosts from the past are hosted in the gentrified shell of today’s Shanghai M50.

(M50 mural painting of female textile workers, used with permission, photographer: Zhu 2019)

Analysis: The Missing Shanghai Yueju in Shanghai CCI through ‘Selective Memory’ and ‘Strategic Forgetting’

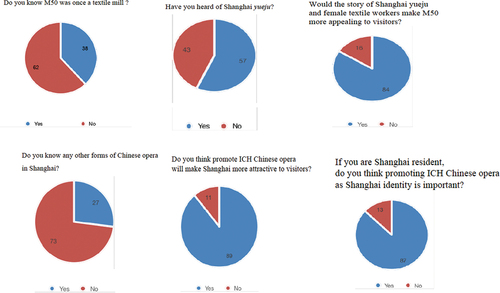

In June 2020, a two-week field research was conducted at Shanghai M50 for the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project Popular Performance for New Urban Audience, Reconnecting M50 Creative Cluster with Shanghai All-female Yueju (2018–2021). One hundred visitors completed digital questionnaires which were designed to gather their knowledge on M50 textile ICH, using the Chinese Digital Questionnaire app Wen Juan Xin (WJX) via WeChat, the most popular Chinese social media platform. The questionnaires contained seventeen questions with single and multiple choices as well as statement options. Participants were provided with explanation on the aims and objectives of the research and had verbal consent obtained before scanned the research team’s WeChat QR code, downloaded WJX and had the questionnaires completed on site. WJX result was then processed and participants’ responses generated as Excel and Word files. Informal discussion and focus group with local residents were also conducted, as well as semi-structured interviews with Shanghai government officials and arts institution managers between 2018 and 2021. Written consent forms were distributed and signed and interviewees’ names are anonymised to protect individual identity. The data collected forms the base of this research paper.

Of the 100 completed questionnaires, 62% of the participants stated that they were unaware of the site was formerly a textile factory; 43% had not heard of Shanghai Yueju, 27% knew the other four awarded ICH Shanghai opera. Nearly no one knew the historical link between Shanghai All-female Yueju and Shanghai female textile workers. Although there are occasional signs naming Xinhe Cotton Factory, there is little information, either onsite or online, to inform visitors about the female textile workers nor Shanghai All-female Yueju. Visitors stated that they came to M50 because the place had been marketed as Shanghai’s popular tourist site with a cool collection of art galleries, design shops, bars and restaurants. The questions participants consistently asked were ‘how could this important information be absent in M50 public marketing?’ and ‘why would the government not promote Shanghai All-female Yueju and Shanghai female textile workers together with M50?’

In the new millennium, Shanghai official branding focuses on the making of ‘Haipai’ or Shanghai (Hai) style (Pai), emphasising the 1920s and 1930s semi-colonial Shanghai. The extraterritorial presence of foreigners, the British architecture along The Bund, and the French concession area of coffee bars lined up on the street turned the city into a legend – a nostalgic imaginary of a global cosmopolitan city (Jansson and Lagerkvist Citation2009; Pan Citation2009; Zheng and Chan Citation2014; Maags and Svensson Citation2018). In the process of Shanghai CCI making, there is no reference to Chinese migrants, who are now well-established Shanghai communities, nor the opera forms they brought into the city and developed in Shanghai. When the author interviewed a senior official at Shanghai Municipal Government regarding the various Shanghai opera forms and Shanghai city branding, the answer was ‘Shanghai needs to kick them (regional opera) out. Shanghai’s identity rests on its semi-colonial past cosmopolitan city. These opera forms don’t represent Shanghai’ (private interview 2018).

The original meaning of ‘Haipai’ in fact bears no nostalgic reference but diversity and innovation. ‘Haipai’ was first coined in the late 1930s to differentiate the Shanghai style Jingju from its conventional Beijing style as Pan comments:

‘Haipai Jingju is spiced up, flashier, with an eye to the box office … To put it another way, to say that a Jingju is done in Haipai is to suggest that it is commercialized, vulgarized and westernized. And these three tendencies – towards the marketplace, popular culture and hybridity – came to be regarded as aspects of Shanghai local identity’ (2009, 219).

Shanghai All-female Yueju is also developed under Haipai, through innovation and creativity. The two major influences that contributed to the rise of Shanghai All-female Yueju in the 1930s were Western drama and Chinese Kunqu. What the Shanghai officials seem to have forgotten is that cosmopolitan Shanghai could not be understood as coming about through the cultural domination of the foreigners alone. The real pre-1949 Shanghai culture involved the interplay of the traditions and customs with the modern brought into the city by thousands of international as well as Chinese rural migrants (Lee Citation1999; Abbas Citation2000). Haipai or Shanghai Style refers to a hybrid culture of both the Western and Chinese migrant communities.

Whilst the officials have excluded Chinese residents and their opera in the making of Shanghai CCI, local communities’ response to M50 and Shanghai CCI is equally hostile. Our research extended visiting and interviewing local residents on their views on M50, and we found that many of them had never visited the site. When asked for reasons, as most residents live around M50 are the remaining redundant female textile workers and M50 must retain their memory of the past, the consistent response was: ‘it (M50) has nothing to do with us’ (private interview 2020). This tension highlights what Halbwachs states, that the reconstruction of cultural memory through institutionally buttressed communication and cultivation results in the official identity becoming a negative ‘this is our opposite’ (1925/1992) and further evokes questions of ‘whose culture, whose city?’ and the critique of spectacle and alienation.

However, the question of why Shanghai textile ICH is not included in Shanghai official CCI continues. After all, the Shanghai textile industry is regarded as the China Mother Industry and a symbol of Shanghai modernity, which is interconnected with Western industrialisation and a semi-colonial past as well as its international connection through contemporary global textile heritage. So why would they not be included in the official making of a collective memory to present Shanghai’s UNESCO Creative Cities cultural identity? I argue that the omission is a ‘strategic forgetting’ to deal with Shanghai post-industrial trauma, conflict and suffering.

Adjacent to M50 stands the Shanghai Textile Museum, another former textile factory turned contemporary art centre, there is a statue of a female bending backwards, with one arm broken and the other pointing up to the sky. The inscription below reads: ‘The martyr breaks (her) arm (to survive)’ (Zhuangzhi Duanbi). It was erected in the late 1990s to commemorate the 550,000 redundant female textile workers. Curator Jiang Guorong of Shanghai Textile Museum explains the importance of the statue:

‘By the mid-1990s, it was evident that State Owned Enterprise (SOE) was no longer working and it became a main burden of Shanghai economic transformation – both space and staff. Where the Pearl Tower stands today, its tripod used to be three textile factories. If they were not demolished, Shanghai could not be redesigned. At that time, Shanghai had 550,000 female textile workers, we had to shed them. By the end of 1990s the number was reduced to 18,000. At M50, we shed all workers retained only 20 cleaners. Today, we still have around 400,000 textile industry pensioners. For Shanghai’s post-industrial transition, the female textile workers sacrificed themselves’ (Jiang Citation2020).

Jiang emphasised that the symbolic meaning of the statue is not just to collectively commemorate the scarified female textile workers, but more importantly, the determination of a successful Shanghai economic transition – ‘the martyr breaks (her) arm (to survive)’ (Zhuangzhi Duanbi). ‘The martyr survived!’ Jiang states, in an exuberant tone, ‘Shanghai has progressed from labour intensive economy to CCI’. This positive official twist of the compulsory act in which female textile workers ‘sacrificed themselves’ for Shanghai’s CCI transition covered the unspeakable trauma and suffering of the female textile workers. Through ‘strategic forgetting’, individuals’ as well as communities’ identity have been re-established, and this has become a way to cope with trauma and stress.

Whilst Jiang spoke about the missing textile ICH in Shanghai CCI transition with pride and guilt, other Shanghai officials are more concerned with how the trauma and suffering needs to be managed to minimise their impact on contemporary official legitimacy. One of our China partners on the awarded AHRC project Song of the Female Textile Workers (2020–2021), which build on Popular performance for new urban audience, reconnecting M50 creative cluster with Shanghai All-female Yueju (2018–2021), expressed their concern on the content of the project

‘Shanghai had gone through a time of turmoil in the 1990s and 2000s. Millions of workers were made redundant, countless protests were staged. The government spent extraordinary amounts of effort, both financially and politically, to have the unrest supressed (yaxiaqu). The very name of the project, the female textile workers, provokes Shanghainese memories (of post-industrial transition) and may cause further social turmoil. We cannot afford the risk, certainly not this year, which is the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) centenary’ (private communication 2021).

Other China partners expressed similar concerns. Whilst being supportive, extreme caution has been taken to ensure the content does not incite any negative memories so that ‘the project may continue’. After numerous alterations to the performance script, which the author penned, China partners asked another ‘final change’ to be made: to alter the concluding sentence from ‘We dedicate the play to the Chinese women who sacrificed themselves in China’s post-industrial transformation’ to ‘We dedicate the play to the Chinese women who embraced themselves in China’s post-industrial transformation’.

As stated earlier, the concept of ‘strategic forgetting’, derived from Bentham and Foucault’s work on panopticon and surveillance, refers to specific ways of ordering and organising the lives and social action of humans as well as animals. In response to the panopticon power and surveillance, the inmates stated in Bentham and Foucault’s work themselves developed a standard behaviour control in which a deeper model of psychology of suppression, repression and the ability to forget are vital to survival. The ‘strategic forgetting’ emphasised by our project China partners clearly derives from the panopticon theory of establishing specific ways of ordering and organising the lives and social action of humans. I argue that the concept of the panopticon in this context are the Chinese government officials have developed a standard behaviour control of ‘self-censorship’, in response to the Chinese communist party (CCP) surveillance. The Shanghai officials have developed ‘a standard behaviour control’ which ensures that ‘no risk’ is taken for ‘another social turmoil’ which may affect the celebration of ‘the CCP centenary’. In other words, the ‘selective memory’ and the ‘strategic forgetting’ act of excluding Shanghai textile ICH in Shanghai CCI making is not only a strategy to deal with the post-industrial trauma of compulsory worker redundancy and painful community dissemination, more significantly, is to ensure China’s one-party regime its own legitimacy and survival.

At the Shanghai Textile Museum, the female martyr statue that once stood at the prominent entrance is now tucked away in an obscure corner on the second floor. M50 continues to stand as a gentrified shell, receiving visitors who have no reference of Shanghai All-female Yueju and Shanghai textile female workers. However, as Halbwachs points out, the relationship between memory and identity are in constant tension and negotiation. During our M50 field research, 89per cent of participants state that they consider the story of the intertwined relationship between Shanghai All-female Yueju and the female textile workers is worth telling and will enhance the M50ʹs attraction and Shanghai cultural identity.

Whilst Shanghai All-female Yueju struggle to appear in official Shanghai CCI spaces, social media as a bottom-up device seems to lend an opportunity to reveal the voice of Shanghai communities: in April 2020, in response to COVID performance restrictions, Shanghai Yue Opera House pioneered a Shanghai Yueju streaming via TikTok and received 1.7 million hits, the highest audience online viewing amongst Shanghai live stream entertainment (Wenhui Net Citation2020). Many of the them are the 400,000 textile pensioners. The community’s voice and their memory maybe selectively forgotten by the officials, but they still exist in Shanghai, and do represent Shanghai.

Conclusion

Tracing the intertwined historical development of the Shanghai All-female Yueju and Shanghai female textile workers, this paper evidences the absence of ICH and its local community cultural expression in the making of Shanghai CCI. Using theories of ‘selective memory’ and ‘strategic forgetting’, exemplified through the case study of Shanghai M50 Contemporary Creative Arts Cluster, this paper explored the continued struggle of cultural identity construction between community memories and official statements. It has argued that the exclusion of Shanghai All-female Yueju and the redundant textile workers are not only a way for Shanghai to manage its post-industrial transitional trauma, but more so to retain the legitimacy of the one-party’s rule. The paper suggests that until Shanghai fully acknowledges its ‘dark heritage’ of community disintegration and incorporates local opera art form as community cultural expression into official city making, Shanghai CCI continues to experience alienation and rejection from its local community.

Although this paper examines the absence of ICH in Shanghai CCI development, the tension between community cultural expression and official CCI making is global. This paper highlights the urgency in safeguarding and implementation of the UNESCO (Citation2003) ICH Convention, which emphasises the process of oral traditions and expressions, performing arts, social practices, rituals and festive events as key in ‘passing on collective memory, creating places of memory for communities of origin and a wider audience for economic as well as social impact’ (UNESCO Citation2003).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Sun Sixing’s work in distributing and collecting digital questionnaires at M50 in June 2020 as a research assistant on the UK AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council) funded project Popular performance for new urban audience, reconnecting M50 creative cluster with Shanghai All-female Yueju (2018-2021; AH/S003304/1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Haili Ma

Dr.Haili Ma is Associate Professor in Performance and Creative Economy at School of Performance and Cultural Industries, University of Leeds. Her research focuses on artistic evolution of theatre and performance in the digital era and their contribution to sustainable socio-economic development. Before coming to the UK in 1997 Haili was a member of Shanghai Luwan All-female Yue Opera Troupe, specialising in xiaosheng (cross dressing male role). Haili has continued to perform and produce whilst developing her academic career. She is the author of Urban Politics and Cultural Capital, the case of Chinese Opera (Routledge 2016) and Understanding Cultural and Creative Industries through Chinese Opera (Palgrave Macmillan forthcoming).

Notes

1. Chinese surname appears before first name. This paper follows this convention.

2. Chinese opera of over 300 regional forms is collectively referred to as Xiqu. Xi means drama and Qu music. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, Xiju has been adopted as an official umbrella term for both Chinese opera and modern spoken drama. Ju means modern drama. Xi, Qu, Ju are often inter-used for Chinese theatre. When referring to a regional opera, regional name appears in front to specify its location. For example, Yue is the ancient name of Zhejiang province and Shaoxin is a region within Zhejiang province. We have Shaoxinxi, Zhejiang Yueju, Shanghai Yueju as well as Zhejiang/Shanghai All-Female Yueju all refer to the same opera. There is another regional opera, Cantonese Yueju (Guangdong Yueju) which has the same pronunciation as Shanghai Yueju but bears a different Yue character. Since the 1950s Shanghai Yue Opera House (Shanghai Yueju Yuan) has been incorporating male Yueju performers in response to party-state directed art reform. However, All-female Yueju remains the most popular form.

3. From 2005, apart from all Beijing Opera and Kunqu Opera Houses across the country, rest state opera houses have funding withdrawn. Since 2014, full state subsidy has been restored to all state opera houses nationally, but strict party-state content censorship applies.

References

- Abbas, M. A. 2000. “Cosmopolitan De-scriptions: Shanghai and Hong Kong.” Public Culture 12 (3): 769–786. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-3-769.

- Amitin, M. 1980. “Chinese Theatre Today: Beyond the Great Wall.” Performing Arts Journal: 9–26.

- Arkaraprasertkul, N. 2019. “Gentrifying Heritage: How Historic Preservation Drives Gentrification in Urban Shanghai.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (9): 882–896. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1460732.

- Assmann, J., and J. Czaplicka. 1995. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique, no. 65: 125–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/488538.

- Bossewitch, J., and A. Sinnreich. 2013. “The End of Forgetting: Strategic Agency beyond the Panopticon.” New Media & Society 15 (2): 224–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812451565.

- Chen, E. Y. I. 2009. “Shanghai Baby as a Chinese Chick-lit: Female Empowerment and Neoliberal Consumerist Agency.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 15 (1): 54–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2009.11666061.

- China ICH Net. 2021. Feiwuzhi yichan mingdan (The ICH List). Accessed on 30 August 2021. http://www.ihchina.cn/project.html

- Connerton, P. 2008. “Seven Types of Forgetting.” Memory Studies 1 (1): 59–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698007083889.

- Elliott, D. M., and J. Briere. 1992. “Sexual Abuse Trauma among Professional Women: Validating the Trauma Symptom Checklist-40 (TSC-40).” Child Abuse & Neglect 16 (3): 391–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(92)90048-V.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

- Freud, S. 1920/1966. Sigmund Freud: Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis. New York: W. W. Norton & .

- Fung, A. Y., and J. N. Erni. 2013. “Cultural Clusters and Cultural Industries in China.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 14 (4): 644–656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2013.831207.

- Gao, Y. 1991. Yueju Shihua (Yueju History). Shanghai: Shanghai Wenhui Publisher.

- Gong, H., and R. Hassink. 2017. “Exploring the Clustering of Creative Industries.” European Planning Studies 25 (4): 583–600. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1289154.

- González Martínez, P. 2020. “Curating the Selective Memory of Gentrification: The Wulixiang Shikumen Museum in Xintiandi, Shanghai.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (6): 537–553. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1821237.

- Halbwachs, M. 1925/1992. On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hangzhou. 2013. Culture: Key to Sustainable Development, Hangzhou International Congress China. Hangzhou: UNESCO.

- Honig, E. S. 1986. Strangers: Women in the Shanghai Cotton Mills, 1919–1949. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Jansson, A., and A. Lagerkvist. 2009. “The Future Gaze: City Panoramas as Politico-emotive Geographies.” Journal of Visual Culture 8 (1): 25–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412908100902.

- Jeannotte, M. 2016. “Story-telling about Place: Engaging Citizens in Cultural Mapping.” City, Culture and Society 7 (1): 35–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.07.004.

- Jiang, J. 2011. Women Playing Men: Yue Opera and Social Change in Twentieth-century Shanghai. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Jiang, G. 2020. “Private Interview.” 20th November 2020.

- Joseph, A., R. Kearns, and G. Moon. 2013. “Re-imagining Psychiatric Asylum Spaces through Residential Redevelopment: Strategic Forgetting and Selective Remembrance.” Housing Studies 28 (1): 135–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.729270.

- Keane, M. 2009. “Great Adaptations: China’s Creative Clusters and the New Social Contract.” Continuum 23 (2): 221–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310802691597.

- Kearns, R., A. Joseph, and G. Moon. 2010. “Memorialisation and Remembrance: On Strategic Forgetting and the Metamorphosis of Psychiatric Asylums into Sites for Tertiary Educational Provision.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (8): 731–749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2010.521852.

- Kearns, R., A. Joseph, and G. Moon. 2015. The Afterlives of the Psychiatric Asylum: The Recycling of Concepts, Sites and Memories. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Kurin, R. 2014. Reflections of a Culture Broker: A View from the Smithsonian. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Lee, L. 1999. Shanghai Modern: Reflections on Urban Culture in China in the 1930s. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Li, L. 1981. China’s Silk Trade: Traditional Industry in the Modern World, 1842-1937. Cambridge: Harvard University Asian Centre.

- Li, S. 2015. Reflections off Stage: Interviews with Shanghai Yueju Audience of 1940s and 1950s (Wutai Xia de Shenying: Ershi Shiji Si Wu Shi Niandai Shanghai Yueju Guanzhong Fangtanlu). Shanghai: Shanghai Yuandong Publisher.

- Luna, R. 2013. “Life of a Shell and the Collective Memory of a City.” IntAR Interventions and Adaptive Reuse 4 , no. : 30–35.

- Ma, H. 2016. Urban Policy and Cultural Capital, the Case of Chinese Opera. London: Routledge.

- Maags, C., and M. Svensson. 2018. Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Meller, H. 2005. Patrick Geddes: Social Evolutionist and City Planner. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mercer, C. 1997. “Geographic for the Present: Patrick Geddes, Urban Planning and the Human Sciences.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 26 (2): 211–232.

- Moghadam, V., and M. Bagheritari. 2007. “Cultures, Conventions, and the Human Rights of Women: Examining the Convention for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage, and the Declaration on Cultural Diversity.” Museum International 59 (4): 9–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0033.2007.00618.x.

- National News Net. 2021. Tuoping biaozhun bushou yiqing gaibian (Poverty elevation will not be effected by COVID). Accessed 10 October 2021. http://www.scio.gov.cn/xwfbh/xwbfbh/wqfbh/42311/42706/zy42710/Document/1675173/1675173.htm

- O’Connor, J., and X. Gu. 2014. “Creative Industry Clusters in Shanghai: A Success Story?” International Journal of Cultural Policy 20 (1): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2012.740025.

- Pan, L. 2009. “Of Shanghai and Chinese Cosmopolitanism.” Asian Ethnicity 10 (3): 217–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631360903189542.

- Pendlebury, J., Y. W. Wang, and A. Law. 2018. “Re-using ‘Uncomfortable Heritage’: The Case of the 1933 Building, Shanghai.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (3): 211–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1362580.

- Rubin, N. H. 2009. “The Changing Appreciation of Patrick Geddes: A Case Study in Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 24 (3): 349–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02665430902933986.

- Schechtman, M. 1994. “The Truth about Memory.” Philosophical Psychology 7 (1): 3–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089408573107.

- Scott, A. J. 2011. “Emerging Cities of the Third Wave.” City 15 (3–4): 289–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2011.595569.

- Shanghai Story. 2014. Auntie Stewardess. Accessed 10 October 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tT2JPPXbKas

- Sun, Y. 2016. “Shanghai Fangzhi, Laochangfang Biansheng Chuangyiyuan (Shanghai Textile, from Textile Mill to Creative Cluster).” Shanghai Guozi (Shanghai National Capital) 225 , no. : 36–37.

- Thomas, H., O. Seitsonen, and E. Koskinen-Koivisto. 2019. “Dark Heritage.” In Encyclopaedia of Global Archaeology, edited by C. Smith. Denmark: Springer 60–77 .

- UNESCO. 2003. UNESCO Intangible Domains. Paris: UNES.

- UNESCO. 2013. Culture: Key to Sustainable Development. Hangzhou: The Hangzhou Declaration, Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies. Hangzhou: UNES.

- Van der Kolk, B. A. 1994. “The Body Keeps the Score: Memory and the Evolving Psychobiology of Posttraumatic Stress.” Harvard Review of Psychiatry 1 (5): 253–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229409017088.

- Wang, S. W. H. 2011. “Commercial Gentrification and Entrepreneurial Governance in Shanghai: A Case Study of Taikang Road Creative Cluster.” Urban Policy and Research 29 (4): 363–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2011.598226.

- Wenhui Net. 2020. “Yanyi Dashijie Yunjuchang (Live Cloud Grand Theatre).” Accessed 20 December 2020. http://www.xinhuanet.com/ent/2020-03/23/c_1125752950.htm

- Wu, W. 2004. “Cultural Strategies in Shanghai: Regenerating Cosmopolitanism in an Era of Globalization.” Progress in Planning 61 (3): 159–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2003.10.002.

- Xinhua News Agency. 2015. Xi Jinping Zai Wenyi Zuotanhuishang de Jianghua Shouci Gongbu Fabiao (Full Publication of Xi Jinping’s Forum on Arts and Literature First Publication). Beijing: Phoenix Report.

- Ying, Z. 2002. Yueju Shi (History of Yueju). Beijing: China Opera Publisher.

- Zheng, J., and R. Chan. 2014. “The Impact of ‘Creative Industry Clusters’ on Cultural and Creative Industry Development in Shanghai.” City, Culture and Society 5 (1): 9–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2013.08.001.

- Zhu, J. 2007. “Zhongguo Chengshi Yu Shanghai Chanye Yuanqu Xietiao Fazhan Yanjiu (Shanghai City and Creative Cluster Development Research).” Zhongguo Renkou Ziyuan Yu Huanjing (China Population Resources and Environment) 17 (6): 139–142.