ABSTRACT

There has been a rise in archival activism, including the birth of social movement archives, leveraging marginalised communities’ voices, and challenging mainstream discourses. Through a case study of the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive (UMVA) in Hong Kong, this paper explores the risks faced by and the strategies of the archivists when preserving social movement objects amidst rapid autocratisation. Based on semi-structured interviews and documents analysis, this paper argues that autocratisation significantly restrains political opportunities for archival activism. When Hong Kong was relatively liberal before 2020, the UMVA encountered problems common in community archives in liberal democracies, such as sustainability crises and loss of public attention. Even so, archivists could still manage the risk by facilitating public communication and group solidarity. Nonetheless, the rapid autocratisation of Hong Kong since 2020 has created extreme political risks for archivists and the collection. Archivists could only migrate the archives overseas, resulting in public inaccessibility of the collection. While most extant literature on archival activism focuses on democratic or post-transitional context, this project offers an authoritarian-political perspective that tests the limits of the notion in the global wave of democratic backsliding.

Introduction

In recent decades, the archives sector has encountered a critical turn when scholars call attention to how its practices can reinforce mainstream discourse and social domination (Derrida Citation1995; Hall Citation2001). The co-reflection among scholars and practitioners has given rise to a new generation of archivists who view pursuing social justice as part of their professional missions (Caswell Citation2020) and call for archival activism, that describes ‘activities in which archivists act to deploy their archival collections to support activist groups and social justice aims’ (Flinn and Alexander Citation2015, 331). There is a growing academic interest in social movement archives and community archives as scholars recognise the potentiality and importance of information practice in advancing social changes (Watson Citation2010; Cooper Citation2016; Bastian and Flinn Citation2020).

However, little if any scholarly attention is dedicated to investigating the dynamics of archival activism in a time of increasing autocratisation, which is defined as ‘a substantial de-facto decline of core institutional requirements for electoral democracy’ (Lührmann and Lindberg Citation2019, 1096). This article argues that the gradual process of autocratisation erodes the freedom of speech underpinning archival activism. In many cases, authoritarian governments censor political information and threaten the safety of pro-democracy citizens (Li and Tong Citation2020). What kind of risks would archivists encounter when they preserve contentious objects? How do they mitigate those risks? Those questions are of growing importance, as Repucci and Slipowitz (Citation2021) observed that the world had experienced democratic backsliding in 15 consecutive years.

With a case study of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement Visual Archive (UMVA), this article will examine the risks and strategies of archiving social movement memories in an increasingly authoritarian context. As a former British colony and a Special Administrative Region in China, Hong Kong was often classified as a ‘liberal autocracy’ (Kuan and Liu Citation2002). Although citizens enjoyed some personal rights such as freedom of speech, the government was not democratically elected. While the quest for electoral democracy has dominated postcolonial social movements in Hong Kong, scholars maintain that contentious memories play a unique role in the struggle against Chinese authoritarianism by inspiring protest tactics and consolidating collective identity (Cheng and Yuen Citation2019; Tang Citation2021). However, the politics of archiving Hong Kong’s social movement memories are rarely discussed.

The UMVA is one of the most significant social movement archives projects, collecting approximately 1300 items related to the Umbrella Movement in 2014. Political resentment exploded in Hong Kong when the government launched a territory-wide engagement campaign to gauge public opinion on electoral reform in late 2013. The pro-democracy camp seized the political opportunity to strive for genuine universal suffrages of which citizens could nominate and elect candidates. However, when the police fired tear gas to suppress pro-democracy protesters on 28 September 2014, many citizens, driven by resentment, occupied three major business districts in Hong Kong. The movement was later characterised by rich cultural expressions and creative practices of cohabitation (Pang Citation2020). Some activists organised the UMVA to preserve the artwork and everyday objects created by protesters against police brutality and site clearance. While the pro-Beijing camp often portrays the movement as a ‘colour revolution’ sponsored by Western imperialists (Wenweipo Citation2015), the UMVA collection tells a different story of creative protesters fighting for electoral democracy and upholding egalitarian values. Qin (Citation2016) stress the importance of Umbrella Movement objects, with which ‘an entire generation of young people associates their political awakening’. Ho and Ting Citation2019, 197) argue that the UMVA is ‘a civic project for pursuing cultural citizenship in support of a democratic society’. However, when Hong Kong authorities escalated their political repression over the opposition camp after implementing a national security law in 2020, the UMVA collection was transferred to Europe due to rising political risk.

Based on the in-depth interviews (N = 8) with core members of the UMVA, organisation documents (N = 23), and visual images of archives materials (N = 309), this article recasts the history of the project. It explores ‘records-risks nexus’, which means the ‘relationship between records and risk’ (Lemieux Citation2010, 199), in the time of autocratisation. This article argues that autocratisation significantly restrains political opportunities for archival activism, especially the preservation of social movement memories that question the political order. When Hong Kong was relatively liberal before 2020, the UMVA encountered some common risks shared by community archives in liberal democracies, such as sustainability crises, participants’ mistrust (Williams Citation2018), and in extreme cases, heritage loss (Istvandity Citation2021). However, the archivists could still manage risk by facilitating public communication and intra-group solidarity. Nonetheless, rapid autocratisation since 2020 has created tremendous political risks for both archivists and the collection. The archivists, therefore, migrated the archives overseas, resulting in public inaccessibility of the collection.

The critical turn for archival practices and the rise of archival activism

Conventionally, archivists are often imagined as the custodians of records, whose professional ethics mainly concern neutrality, objectivity, and information accuracy (Greene Citation2013). However, some scholars and practitioners have called for a critical turn in the sector over the past few decades. They criticise the passivity, political indifference, and singularity of the mainstream archival community (Findlay Citation2013; Flinn and Alexander Citation2015). Some further argue that the asymmetrical power relations in recordkeeping reproduce and reinforce the oppressive structures, like sexism, racism, and colonialism in society (Derrida Citation1995; Hall Citation2001). The postmodern understanding of archival practice prompts practitioners to ‘radically rethink, redo, and reuse archives’ (Caswell Citation2020, 152). Scholars perceive the pursuit of social justice as part of the professional responsibilities of the archival community (Jimerson Citation2007).

The shift of attention to social justice creates possibilities previously absent in traditional archival practices. One prominent trend is the rise of ‘archival activism’ that regards archivists as agents of social change (Flinn Citation2011; Findlay Citation2016). Many community-based archives and memory projects have emerged around the world. Unlike established institutions, those projects are usually staffed with volunteers and amateur archivists, many of whom aim to amplify the voice of marginalised communities and promote progressive social values, such as gender, class, and racial equality (Bastian and Flinn Citation2020). Some scholars evaluate the impacts of social movement archives; for example, Sellie et al. (Citation2015) theorises activist archives as ‘a free space for social movement culture’ that can connect community members and nurture movement solidarity through the study of Interference Archive in New York. Some examine the strategies of the archivists; for example, Cooper (Citation2016) assesses the case of BC Gay and Lesbian Archives in Vancouver and explores how it transcends the public/private and personal/ institutional divide in preserving the memories of gender minorities.

However, I would argue that autocratisation is a crucial variable absent in the current discussion because it threatens information rights and possibly creates political risks for the archives. There is some excellent literature on post-transitional archives in Latin America, South Africa, and the Balkan states, many of which have experienced a long period of authoritarian rule but later were democratised (Giraldo and Tobón Citation2021; Viebach, Hovestädt, and Lühe Citation2021). Nevertheless, the academic discussion on archiving social movement memories in authoritarian or semi-authoritarian contexts is still limited, especially those directly challenging government rule. One exception is Ngoepe and Netshakhuma (Citation2018) briefly illustrating how the records of the African National Congress liberation archives were ‘created in the trenches’ anonymously and transferred secretly from one place to another during the apartheid era in South Africa.

Mainland China is a significant case for studying archival practices in authoritarian contexts; community archives have been growing recently, but most are usually government-funded or hosted by scholarly organisations, with only a few exceptions established by the community (Lian and Oliver Citation2018). In order to survive under the existing legislative framework, China’s community archives avoid touching on politically sensitive issues and confronting the developing strategies of the state (Lian Citation2021). Some socially conscious citizens attempt to bypass state surveillance and commemorate political tragedies, such as the Great Famine in the 1950s, through digital technologies like Weibo (Zhao and Liu Citation2015). However, most traces of resistance remain undocumented. As Hillenbrand (Citation2020) argues, public secrecy has become a potent structuring force that recognises the danger of knowing and the benefit of knowing what not to know. Instead, some of the contentious memories were preserved by foreign communities; for example, Bond (Citation1991) traced how Amnesty International staff collected and smuggled protest leaflets from Beijing to London after 1989 Tiananmen Massacre in China.

This article will particularly look into the risks of archiving contentious memories and the strategies employed by archivists in an autocratising regime. Professional standards, like IEC 31010:2009 (International Organization for Standardization, Citation2009), define risk as ‘the effect of uncertainty on [organisational] objectives’. While much extant research focuses on microbiological, systematic, or digital risks (Donaldson and Bell Citation2019; Pinheiro, Sequeira, and Macedo Citation2019), many scholars also take into account political threats, including government censorship (Medina Citation2020) and even military conflicts (Lowry Citation2017). Political risks can lead to material decay, information loss, or even the complete migration or destruction of collections. In authoritarian politics, state repression can threaten the personal security of political dissidents, including socially engaged archivists, through mass purges and physical abuses (Li and Tong Citation2020). Authoritarian regimes are also more likely to be associated with information censorship (Wong and Liang Citation2021) which puts the archives materials at risk of destruction. Meanwhile, they may anticipate difficulties shared by those in liberal democracies; for instance, the sustainability crisis caused by the lack of space, money, and expertise (Williams Citation2018).

Methodology

From 2 July 2021 to 9 March 2022, eight semi-structured interviews, consisting of pre-set questions, were arranged with archive volunteers.Footnote1 As I was one of the volunteers of UMVA, interviewees were mainly recruited through my professional networks and the snowball sampling method. This article anonymises all the interviewees and institutions that supported the UMVA project.Footnote2

For the data analysis, edited transcripts were written for each interview. An inductive grounded theory approach was adopted to establish categories and a conceptual system. After coding the textual materials, I grouped the codes into higher-level concepts and categories until theoretical saturation was achieved.Footnote3 Finally, categorisation was followed by the cautious interpretation of the underlying context.

However, I was aware of my positionality between a volunteer archivist and a researcher. As a former and irregular volunteer from 2015 to 2020, I was able to apply my insider knowledge to the research study. Also, I enjoy the privilege of accessing 309 visual images and 23 sets of internal documents, which allows me to recast the development of the UMVA.Footnote4 Meanwhile, I also reminded myself to prevent presumption by considering the broader picture of theoretical interests and looking for generic propositions.

The formation of the umbrella movement visual archive

On September 28, when the police fired tear gas canisters at pro-democracy protesters, the general public was shocked by the scene because it was the first time tear gas was used to suppress pro-democracy protests since the sovereign transfer in 1997.Footnote5 Driven by moral outrage and the urge to protect students (Li and Tong Citation2020), the angry crowd occupied the main roads of three business districts: Admiralty, Causeway Bay, and Mongkok, kicking off what became known as the Umbrella Movement.Footnote6

In the beginning, the government adopted a tolerant approach to the protest to de-escalate political tension. The police retreated and did not intervene so long as protesters did not advance. In preparation for a long campaign, protesters set up tents, food stations, stages, and first aid teams, while some established barricades and patrol teams to protect the areas. As the protesters cohabited together, utopian villages gradually took shape in protest sites. The occupied area in Admiralty was nicknamed ‘Harcourt Village’, where protesters decorated and named their tents to make their warm home. After a few days, more and more community facilities appeared, such as study rooms, recycling stops, and power stations. As a result, the Umbrella Movement became not only a collective struggle for electoral democracy but also an experimental ground for egalitarian values, deliberative democracy, and participatory cultural practices (Pang Citation2020).

The UMVA was formed in early October 2014 as protesters gradually built up their villages. Interviewee A, the co-founder of UMVA, was a young urbanist-artist.Footnote7 After the Umbrella Movement started, the idea of establishing a social movement archive soon occurred to him:

Back at that time, everyone, including me, was eager to contribute to the movement. I hoped to offer what I had and what I could do. In October 2014, the occupation areas became a wild gallery where excellent artworks could be found everywhere. Therefore, I wanted to organise people to save the art pieces.

Another co-founder, Interviewee B, a visual arts expert, developed an equivalent idea in early October.Footnote8 Initially, she visited the occupied area in Tsim Sha Tsui more frequently. One day, she wrote on a mahjong paper card in Chinese calligraphy style: ‘I Want True Universal Suffrage’ (ngo yiu jan pou syun). However, the banner was lost when the police cleared the area on October 3. She kept asking herself, ‘while we occupy the streets, what else can we do besides slogan-shouting?’ With the destruction of her work, she was determined to develop a social movement archives project. She and one of her friends later met Interviewee A. They called a meeting on October 12 in Admiralty, attracting around 20 people to join the core team of UMVA. The core team recruited more volunteers through Facebook, public announcements on protest sites, and personal networks. Interviewee A recalls that people were eager to contribute to the movement, so there were more than 200 volunteers in the early stage.

Selection and capture of social movement objects

Once the UMVA volunteer team was established, its first and foremost mission was to investigate the protest sites and identify the items to be collected.

Mistrust from the protesters

As the police adopted a non-intervention policy, the most significant risk for the volunteer archivists was not state repression but rather a lack of resources and suspicion from protesters. It created some real but minor problems for volunteers, who conflicted with the protesters in a few circumstances. When they intended to collect particular onsite objects, protesters insisted that the movement was ongoing and those things should stay. Interviewee E, a Ph.D. student during the Umbrella Movement, was an active volunteer in the Mongkok occupied area.Footnote9 He recalled that the UMVA was criticised by some radical protesters who dismissed the value of preserving artworks.Footnote10 Another volunteer, Interviewee F, encountered the same predicament in Harcourt Village, where he regularly stayed overnight.Footnote11 On November 30, while student leaders called for encircling government headquarters, there were violent exchanges between protesters and the police. Interviewee F and his companions attempted to protect the onsite objects from destruction, but they were scolded by protesters who insisted it was time to battle for democracy rather than collect artworks.

The volunteers tended to minimise the potential risks of protesters’ mistrust via communication. In the beginning, volunteers reached agreement on the basic principles of archival practices: they would only collect the objects i) no longer used, or ii) at the very last moment of the occupy protest. The volunteers, if possible, should seek permission from creators before collecting and documenting artworks. In fact, according to Interviewee F, some artists turned down his request because they wanted their works to ‘die with the protest’. The archival principles provided an action guide for volunteers and avoided unnecessary conflicts with the protesters.

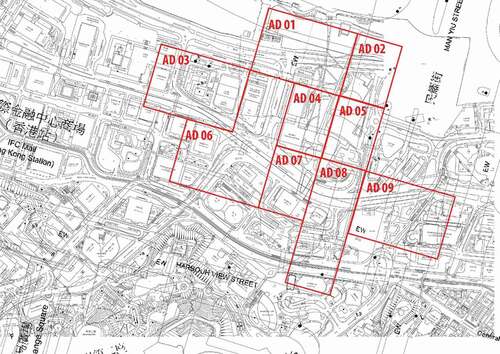

After the first two weeks, as the UMVA recruited a vast team of volunteers, core members developed a management system to monitor and facilitate onsite works. The three occupied zones were divided into 20 geographical blocs (see ); each bloc was supervised by a team of fewer than 20 volunteers, including a team leader who regularly contacted core members. The founders created a communication group for each team with the instant messaging app Telegram, which accommodated massive group conversations and allowed users to cloak their telephone numbers. The purpose was to facilitate communication, report emergencies, and nurture team cohesion. The UMVA also established a booth when Harcourt Village took shape. The booth could serve as a contact point to recruit new members and answer enquiries. Volunteers sometimes helped the protesters to repair some hand tools and banners. To reassure the protesters who barely knew the UMVA, volunteers wore labels to show their identity.

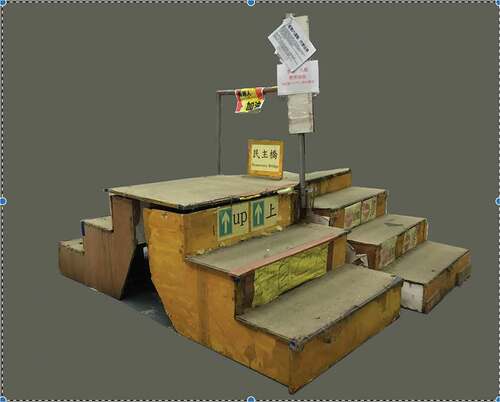

Volunteers had to investigate the assigned districts and interview the protesters to explore the stories behind protest objects of distinctively aesthetic or historical significance. For example, volunteers later collected a tent called ‘Hong Kong Camp’ () in Harcourt Village; the resident not only wrote down the slogan, ‘Say no to fake democracy’, but also drew a mailbox, nameplate, and also some cartoons of local gods and Jesus Christ as amulets, demonstrating the creativity and utopian characteristics of the movement. Some collected objects are less artistic but highly symbolic, such as the staircases () that cut across concrete barriers on Harcourt Road and allowed citizens to travel across Harcourt Village more easily. In general, volunteers successfully built trust with most of protesters. For instance, Interviewee E conducted 14 interviews in Mongkok without significant conflict, even though radical protesters dominated the places (Yuen Citation2018).

Mental and physical burn-out

One of the most challenging parts for volunteer archivists was perhaps the psychological stress. The Umbrella Movement, and the broader political deadlock, lasted for almost three months; some UMVA volunteers were caught in frustration, powerlessness, and fatigue. Therefore, many of them could not sustain their dedication to the project. For example, Interviewee C, a full-time student in 2014, left the project soon after setting up the booth for the UMVA. She felt exhausted and stressed under such a social environment. Besides socio-political factors, many volunteers were full-time students or employees who struggled to balance their daytime duties and voluntary engagement in the UMVA project. Interviewee E estimated that only half of his team stayed until the end of the Umbrella Movement.

While some volunteers quit the UMVA in the middle of the movement, others could overcome the overwhelming stress by establishing affective ties to their archival work. Interviewees A and B found their purposes and position in the democratic movement by creating the UMVA. As a computer science student without much knowledge in politics before the Umbrella Movement, Interviewee F perceived participation in the UMVA as his political awakening moment. Interviewee F also added that the UMVA was a platform for nurturing friendship and emotional ties. With the sense of self-actualisation and affective ties, some UMVA volunteers eventually overcame the psychological stress.

In mid-November, when the government repeatedly revealed its intention to clear the site, UMVA core members realised it was the time to collect social movement objects. Therefore, Interviewee A contacted a secondary school for temporary storage of the collection. On November 25, court bailiffs, with the help of police officers, emptied the occupied areas in Mongkok. Before that, the UMVA had evacuated selected objects to the school in an orderly fashion.

An enormous retreat happened on the night of December 10 and the following morning, as the police announced their intention to take over the occupied area in Admiralty on December 11. That night, Harcourt Village was like a carnival, as villagers treasured the last moments of their utopian-like cohabitation. People were packed tightly; many citizens rushed to take pictures (see ). It was also the busiest night for UMVA volunteers who needed to collect all the identified items before the site clearance. Interviewees A and E remembered that many ordinary citizens came and helped their retreat. Interviewee C also rejoined the UMVA helpers. The collection process was smooth, but some fresh volunteers just took up everything they saw, enhancing the difficulties of preservation in the later stage. Interviewee F remembered that the evacuation lasted from 10 pm to 7 am. Interviewee E mentioned they called three trucks to transfer the items.

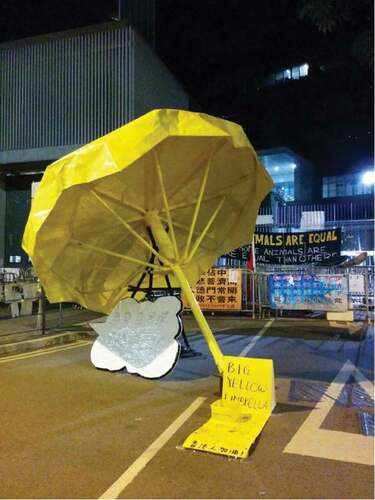

However, volunteers failed to collect the largest objects, such as the 3 m tall ‘Big Yellow Umbrella’ (see ). While citizens witnessed the site clearance via online broadcast, UMVA volunteers watched the scene of police destroying the leftover artworks in the occupied area. On December 15, the police finished clearing the occupied area in Causeway Bay, the last and smallest among the three protest sites. The clearance ended the Umbrella Movement and the collection phase of the UMVA, which captured 309 objects and over 1000 posters.

Preservation and use of social movement objects

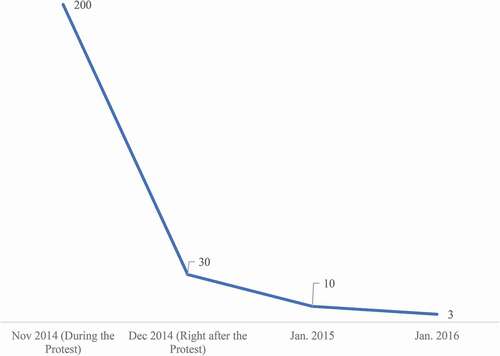

After collecting social movement objects, it was the most hectic moment for the UMVA volunteers, because they had to clean, preserve, and catalogue the items. However, most volunteers quit the project after the Umbrella Movement, partly because the failure of the movement traumatised many protesters who were new to street politics (Lee et al. Citation2019). Also, many politically engaged citizens turned to other channels to advance Hong Kong’s democratisation, such as the District Council (DC) election in 2015. When entering the preservation stage, there were only approximately 30 volunteers; many appeared intermittently because they had work duties during the week. The loss of public attention and helpers aggravated the risks encountered by volunteer archivists, such as psychological and financial stress.

The increasing burden on declining numbers of volunteers

Interviewee A borrowed half of a multi-purposed classroom for the collection. Based on my site visit, the storage area was approximately 150 ft2. Some sizeable items, like the aforementioned staircase, were placed at a corner of the underground carpark. According to Interviewee E and Interviewee G,Footnote12 the overcrowding environment made their job difficult and stressful.

Interviewees F and G recalled that cleaning social movement objects was an arduous task. It had been raining in Hong Kong for several days before the UMVA collected the objects. Therefore, the volunteers needed to remove mud and dry the items carefully. It was a physically demanding procedure as volunteers had to carry heavy banners to the rooftop for drying in the sun. After cleaning and drying, they protected items with cling wrap, another time-consuming and exhausting task. A tremendous workload and serious understaffing created a vicious circle: more volunteers left the project, and people who stayed bore a more significant burden. In January 2015, Interviewee G, an active student volunteer, left for an exchange programme in Taiwan. With their departure, only around ten people remained active in the UMVA.

Nonetheless, according to Interviewee G, volunteers improvised some DIY methods to overcome resource constraints and physio-psychological stresses. For instance, facing a lack of space for storing banners, volunteers realised folding them might create ruptures on the surface. Therefore, they used soft pipes and butter paper to scroll the giant banners together. Also, dealing with the problem of humidity, volunteers created homemade dehumidifiers with desiccants and soup bags. These DIY methods saved much storage space, preserved the banners in good condition, and empowered volunteers with a sense of creativity.

Financial stress of the UMVA

After cleaning the objects, the UMVA encountered a more complex financial problem. Volunteers brainstormed some ideas to amplify the social values of the collection. However, resource constraints frustrated their plans and deepened the divide among the UMVA members. Some volunteers proposed establishing a website to serve as an online repository for the collection, so Interviewee B hired a web designer who drafted a webpage layout. Despite their effort, the project died on the vine because volunteers could not sustain their commitment physically and financially; Interviewee B stated they had already spent around HKD 40,000 (USD 5,160) on the project.Footnote13 Worse still, the UMVA had to invest more money on a permanent site for their collection. As recalled by Interviewee E, the school ordered them to leave during the summer of 2015, saying that it had to prepare for the new academic year. Interviewee A rented a 400 sq ft studio flat in San Po Kang,2 but it ‘became a nightmare’ for him. He paid approximately HKD 10,000 (USD 1,290) every month for the studio. Having not yet secured a full-time teaching position, Interviewee A described his investment in the studio as a ‘bottomless abyss’.

While the financial risk became a significant problem for the UMVA, volunteers explored various income sources. On the ‘July-first March’ in 2015, the UMVA set up a booth on the demonstration route to activate public memories of the Umbrella Movement and fundraise for their project. Yet the general public was indifferent to both their booth and the march, as many young protesters questioned the effectiveness of demonstrations (Lee et al. Citation2019). They also organised two exhibitions from September 26 to October 10. Unfortunately, they only received a few donations that could barely cover the studio rent for one month.

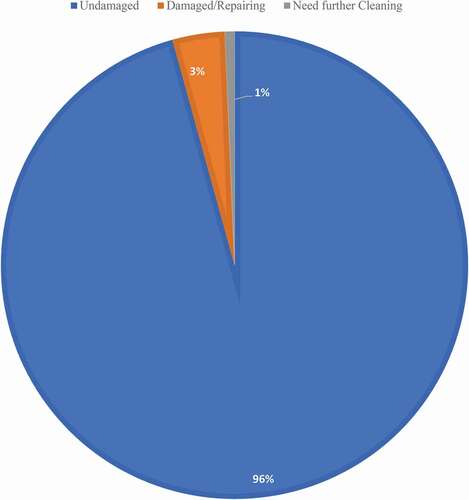

Seeing no concrete progress, some core members lost their faith in the archive’s future. Less than five active members remained by the end of 2015 (see ), all preoccupied with other full-time duties. Despite the lack of financial and human resources, most parts of the UMVA collection remained undamaged, at least before the record transfer in 2017 (see ).Footnote14 In 2017, Interviewee A could no longer withstand the financial pressure, so he decided to hand the collection over to a professional institution. Despite the pro-democracy nature of the UMVA, Interviewee A experienced little trouble in finding a new home for the collection because freedom of expression was still generally respected at that moment. The collection was finally migrated to a university library in May.

Autocratisation

Hong Kong was essentially a non-democratic regime and academic freedom was not a guarantee when the government manipulated most of the university funding. Interviewee H, a senior staff member of the university library at that time, highlighted the institutional constraints she and some of her colleagues encountered. Although they were enthusiastic about social justice, they needed to protect the interest of the library and avoided making a political stance. The library staff, being politically cautious, maintained a low profile in dealing with the UMVA collection. Only a few staff members participated in the project; Interviewee H sometimes worked overnight to digitise the posters in her office. Instead of requesting more storage space from the university, Interviewee H put some of the items at her office. The library established an online page for (but never advertised) the collection. When receiving enquiries from public members, the library and the Public Relations Office usually directed them to the online page, without further comments. The fate of the UMVA changed when Hong Kong experienced its most crucial political crisis in postcolonial history, the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) Movement in 2019 (Lee et al. Citation2019). The government proposed amending the extradition law to allow transfer of suspects to other jurisdictions, including Mainland China and Taiwan. The general public feared that the government would abuse this power to extradite political dissidents to Mainland China. A million citizens protested on June 9 to call for the complete withdrawal of the proposal. When the government insisted on the second reading debate on June 12, another protest surrounded the Legislative Council Building. The police, for the first time in postcolonial history, used rubber bullets to suppress the demonstration in addition to tear gas. In the following weeks, the Anti-ELAB Movement gradually evolved into a full-fledged anti-authoritarian protest, in which the citizens demanded democratic and policing reform. The movement died out only when the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the city.

Since the protest, the government escalated political repression over civil society. As of April 2021, the police made 10,242 arrests connected to the Anti-ELAB Movement, including many young students (Ng Citation2021). The introduction of the national security law on 30 June 2020, was particularly controversial because suspects can face a maximum sentence of life in prison if charged with secession, subversion, terrorism, or collusion with foreign forces. By 30 June 2021, 117 people were arrested under the national security law (Yiu and Katakam Citation2021). In addition, the government has resurrected a colonial-era law ruling that ‘any person who without lawful excuse has in his possession any seditious publication shall be guilty of an offence.Footnote15’ Legal repression has seriously affected the records management sector by spreading fear and self-censorship. For instance, public libraries have pulled down pro-democracy books since July 2020 (Strumpf, Citation2020). Also, the June Fourth Museum, which collected and exhibited items about Tiananmen Massacre 1989, has been indefinitely suspended since June 2021 (Davidson, Citation2021).

The mounting political risk forced the UMVA and university library to rethink their collection strategy. With the pro-Beijing camp predicting the introduction of the national security law in April 2020, Interviewee H advised Interviewee A to move the collection away from the university. Interviewee A agreed and felt that there were no other ways to mitigate the mounting political risks. Eventually, with assistance from Interviewee H, Interviewee A, on behalf of the UMVA, signed a deposit contract with an institute in Europe that accommodates social movement objects from different parts of the world. The deposit contract lasts for ten years, subject to future extension. The contract includes a photo of the collection and a catalogue showing the basic description of deposited items. According to the agreement, the UMVA retains ultimate ownership of the collection. The institute in Europe has the right to use the materials and is responsible for the collection’s care. According to Interviewee A, the institute promises that UMVA can host back the collection if the political situation in Hong Kong allows. In May 2020, Interviewee A visited the collection and conducted a final check at the university library. After that, the collection was transferred to Europe through commercial shipping in a low-profile manner before the national security law was implemented. Later, an institute representative sent an email to Interviewee A notifying them that the items had been received. However, as of January 2022, Interviewee A has not visited Europe to verify the collection conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Having limited knowledge about the archive industry in Europe, he is also confused about the roles of the institute and how the collection will be managed. At the time of writing, the collection remains closed, hampering public access to the materials.

Although the domestic audience will face barriers accessing the collection in the future, Interviewee A believes that he has made the best decision, as the collection is under the custody of a professional body and safe from destruction now. It can be argued that, with academic freedom on the wane in Hong Kong, a university library is no longer a secure place for socially engaged staff and the Umbrella Movement collection. It was reported that national security police occasionally searched university campuses in Hong Kong, while there has been an exodus of Hong Kong’s academic staff since 2020 (Kwan Citation2021). The political risk has also proved very real for the UMVA; one of its former core members was arrested for criminal charges under Hong Kong’s national security law. Although she has left the UMVA early and her lawsuit is unrelated to the archive project, it has created fear and anxiety among some interviewees. Migrating the collection protects not only the social movement objects but also the personal security of the archivists, because the collection can potentially draw political and legal attacks from the government amidst the rapid autocratisation. In fact, many of Hong Kong’s civil society organisations have adopted a similar strategy; at least 50 pro-democracy groups disbanded in one and a half years after the imposition of the national security law, with many of them deleting all of their records, like social media content and written documents (Walker Citation2021). However, it may lead to a vicious circle of autocratisation: while state repression harms information rights through censorship, democratic backsliding will be sped up, because freedom of information is the key to government accountability and public deliberation (Shepherd and Yeo Citation2003).

Conclusion

Archival activism has become a global phenomenon, as people around the world increasingly recognise the potentiality of information practice in fostering social changes (Bastian and Flinn Citation2020). Many recordkeepers are devoted to preserving social movement memories that challenge mainstream narratives, inspire collective mobilisation, and consolidate collective identity (Cheng and Yuen Citation2019; Tang Citation2021). However, while there is much effort to theorise archival activism, mainly with cases in Western democracies, the experiences of archives and archivists in authoritarian regimes are often neglected. Therefore, I raised two inter-related questions: What risks would the archivists encounter when preserving social movement objects in an authoritarian context? How do they counteract those risks?

This article has contributed to the current debates on archival activism and social movement memories by establishing a record-risk nexus in authoritarian Hong Kong that is different from Western democracies. This article illustrates the ways in which the physio-psychological wellbeing of the volunteer archivists, safety of the collection, the precariousness of resources, the interplay with protesters, and an authoritarian threat combine to create risks to both the collection and those who preserve them. This article also traces and explains how archival activism is sensitive to changing political climates: the UMVA has passed through different political stages of Hong Kong and developed various forms of records-risk nexus (see ). The UMVA was established during the peak days of the Umbrella Movement when socially engaged citizens were eager to contribute their labour and expertise to the democratic cause. When freedom of speech was still respected in the semi-authoritarian city, the harshest challenges to the volunteer archivists were mistrust from protesters and their physio-psychological exhaustion. Still, the UMVA volunteers eventually gained the trust of the protesters by establishing transparency and clear archival principles while overcoming personal frustration by giving meaning to their participation.

Table 1. The records-risk nexus of the UMVA

When the Umbrella Movement ended in December 2014, Hong Kong entered a period of movement abeyance, when activists were traumatised by the failure of their efforts. Along with the loss of volunteers and public attention, the UMVA entered the labour-intensive collection care phase. The physical, mental, and financial burden was left on the shoulders of remaining volunteers. In the beginning, volunteers could improvise DIY methods to relieve their burn-out. However, when financial investment by the volunteers turned out to be a ‘bottomless abyss’ and no visible progress was achieved, tension among the volunteers deepened. After crowdfunding and donation failed to generate enough income, the only realistic way was to collaborate with a professional and resource-rich organisation.

Nonetheless, the Anti-ELAB Movement in 2019 and the subsequent promulgation of the national security law in 2020 showed that the political climate in non-democratic countries could change drastically in a short period. While the government tightens its control over civil society and fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, are challenged, there is only limited space for archival activism that exposes archives and archivists to extreme political and legal risks. As a result, recordkeeping sectors either submitted to self-censorship (self-compromise), such as the cases of some public libraries, or migrated the politically sensitive records to other places, as the UMVA did.

This article shows that autocratisation can be a crucial factor influencing the records-risk nexus in archival practice. An authoritarian perspective is both theoretically and practically important to record keeping professionals in an era of democratic backsliding. However, my research has some limitations. Although the single-case study can preserve the rich context of and explore dynamics within archival activism in Hong Kong, more research is needed to test if the experience of the UMVA is comparable in other non-democratic contexts. The migration of the UMVA demonstrates that the records-risks nexus in the archive sector of Hong Kong might become more similar to that of Mainland China, as Lian (Citation2021, 240) observed that China’s community-based archives ‘should be consistent with or at least not contradictory to the political, social and cultural development strategies of the state’. However, more scholarly efforts should be dedicated to comparing the survival strategies of community archives in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Also, while the UMVA collection was migrated to Europe, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Citationn.d.) also hosts the ‘Hong Kong Protest Movement and Aotearoa’ collection, consisting of 60 social movement objects created during the Anti-ELAB Movement. Future research is needed to reflect contemporary archival issues, such as displaced archives and how they relate to broader socio-political contexts such as global autocratisation and transnational social movements.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to my MA dissertation supervisor Dr. Anna Sexton for the valuable advice. I also owe thanks to Prof. Tim Jordan, Dr. Daniel Boswell, Dr. Andrew Flinn, Dr. Elizabeth Lomas, Dr. Samson Yuen, Dr. Sean Tierney and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. I also thank my interviewees for participating in this study.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that I was an irregular volunteer of the Umbrella Movement Visual Archive from 2015 to 2020 that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from my voluntary involvement in the organization.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kin-Long Tong

Kin-long Tong is a PhD student in the Department of Information Studies at UCL. His research interests include information politics, media activism, DIY culture, self-publishing, and independent archives in authoritarian contexts. His articles were published in peer-reviewed journals, such as, Sociological Forum, Radical History Review, Japanese Journal of Political Science and ZINES Journal. Before joining the academia, Tong worked for publishing press, university libraries and independent archives. Twitter: @BillyTong13.

Notes

1. For the information of each interview, please refer to appendix I. The interviews were conducted in Cantonese, the mother language of the interviewees.

2. I obtained the research ethics approval from the Department of Information Studies, UCL on 22 May 2021 and registered for the data protection on 8 July 2021.

3. For the full coding scheme, please refer to appendix III.

4. For the information, please refer to Appendix II. The use of materials was consented by the two founders of the UMVA. The documents are primarily about the daily operation and the collection condition of the UMVA, containing no private information of the volunteers.

5. Tear gas was once used in 2005 against the anti-WTO protesters led by Korean farmers.

6. The occupy protest extended to another central business district, Tsim Sha Tsui, on October 1, but the police soon took over the area on October 3.

7. Interview A, 2 July 2021.

8. Interview B, July 13.

9. Interview E, July 23 2021.

10. Although the radical protesters advocated militant actions, their level of violence was still far lower than that of many places. For example, they did not use offensive weapons commonly found in riots like metal sticks and Molotov cocktails.

11. Interview F, July 24 2021.

12. Interview 7, 7 August 2021.

13. The exchange rate was HKD 1 = USD 0.129 in June, 2015.

14. N = 309; Only covers the non-poster objects.

15. Cap. 200 Crimes Ordinance.

References

- Bastian, J. A., and A. Flinn. 2020. “Introduction.” In Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity, edited by J. A. Bastian and A. Flinn, xix–xxiv. London: Facet.

- Bond, S. 1991. “An Archive of the 1989 Chinese Prodemocracy Movement.” The British Library Journal 17 (2): 190–197.

- Caswell, M. 2020. “Feeling Liberatory Memory Work: On the Archival Uses of Joy and Anger.” Archivaria 90: 148–164.

- Cheng, E., and S. Yuen. 2019. “Memory in Movement: Collective Identity and Memory Contestation in Hong Kong’s Tiananmen Vigils.” Mobilization 24 (4): 419–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-24-4-419.

- Cooper, D. 2016. “House Proud: An Ethnography of the BC Gay and Lesbian Archives.” Archival Science 16 (3): 261–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9250-8.

- Davidson, H. 2021 “Mourn June 4 in Your Own Way: Tiananmen Square Events Vanish amid Crackdowns and Covid.“ The Guardian, 3 June.

- Derrida, J. 1995. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Donaldson, D. R., and L. Bell. 2019. “Security, Archivists, and Digital Collections.” Journal of Archival Organization 15 (1–2): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15332748.2019.1609311.

- Findlay, C. 2013. “People, Records and Power: What Archives Can Learn from WikiLeaks.” Archives and Manuscripts 41 (1): 7–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2013.779926.

- Findlay, C. 2016. “Archival Activism.” Archives and Manuscripts 44 (3): 155–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2016.1263964.

- Flinn, A. 2011. “Archival Activism: Independent and Community-led Archives, Radical Public History and the Heritage Professions.” UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies 7 (2). doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/D472000699.

- Flinn, A., and B. Alexander. 2015. ““Humanizing an Inevitability Political Craft”: Introduction to the Special Issue on Archiving Activism and Activist Archiving.” Archival Science 15 (4): 329–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9260-6.

- Giraldo, M. L., and D. J. Tobón. 2021. “Personal Archives and Transitional Justice in Colombia: The Fonds of Fabiola Lalinde and Mario Agudelo.” The International Journal of Human Rights 25 (3): 529–549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1811691.

- Greene, M. 2013. “A Critique of Social Justice as an Archival Imperative: What Is It We’re Doing That’s All that Important?” The American Archivist 76 (2): 302–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.76.2.14744l214663kw43.

- Hall, S. 2001. “Constituting an Archive.” Third Text 15 (54): 89–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820108576903.

- Hillenbrand, M. 2020. Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China. London: Duke University Press.

- Ho, S., and V. Ting. 2019. “Museological Activism and Cultural Citizenship: Collecting the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement.” In Museum Activism, edited by R. R. Janes and R. Sandell, 197–207. Abingdon: Routledge.

- International Organization for Standardization. 2009. “IEC 31010: 2009 Risk Management — Risk Assessment Techniques“ https://www.iso.org/standard/51073.html

- Istvandity, L. 2021. “How Does Music Heritage Get Lost? Examining Cultural Heritage Loss in Community and Authorised Music Archives.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (4): 331–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1795904.

- Jimerson, R. 2007. “Archives for All: Professional Responsibility and Social Justice.” American Archivist 70 (2): 252–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.70.2.5n20760751v643m7.

- Kuan, H.-C., and S.-K. Liu. 2002. “Between Liberal Autocracy and Democracy: Democratic Legitimacy in Hong Kong.” Democratization 9 (4): 58–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/714000284.

- Kwan, R. 2021. “National Security Police Search University of Hong Kong Student Union.” Hong Kong Free Press, 16 July.

- Lee, F. L. F., S. Yuen, G. Tang, and E. W. Cheng. 2019. “Hong Kong’s Summer of Uprising: From Anti-extradition to Anti-authoritarian Protests.” China Review 19 (4): 1–32.

- Lemieux, V. L. 2010. “The Records-risk Nexus: Exploring the Relationship between Records and Risk.” Records Management Journal 20 (2): 199–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09565691011064331.

- Li, C.-K., and K.-L. Tong. 2020. ““We are Safer without the Police”: Hong Kong Protesters Building a Community for Safety.” Radical History Review 137 (137): 199–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-8092870.

- Lian, Z. 2021. “Dancing with the State: The Emergence and Survival of Community Archives in Mainland China.” Archives and Manuscripts 49 (3): 228–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2021.1958237.

- Lian, Z., and G. Oliver. 2018. “Sustainability of Independent Community Archives in China: A Case Study.” Archival Science 18 (4): 313–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-018-9297-4.

- Lowry, J. 2017. Displaced Archives. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lührmann, A., and S. I. Lindberg. 2019. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New about It?” Democratization 26 (7): 1095–1113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

- Medina, M. 2020. “Governmental Censorship of the Internet: Spanish Vs. Catalans Case Study.” Library Trends 68 (4): 561–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2020.0011.

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. n.d. “Hong Kong Protest Movement and Aotearoa.” Accessed 29 January 2022. https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/topic/11038?fbclid=IwAR0lJJvhuz9cviOZyd3cRKpIe9jagx3cZWlsNky7BGyhtccLrcGkHESpJ5M

- Ng, K.-C. 2021. “Hong Kong Protests: More than 10,200 Arrested in Connection with Unrest since 2019.” South China Morning Post, 9 April.

- Ngoepe, M., and S. Netshakhuma. 2018. “Archives in the Trenches: Repatriation of African National Congress Liberation Archives in Diaspora to South Africa.” Archival Science 18 (1): 51–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-018-9284-9.

- Pang, L. 2020. The Appearing Demos: Hong Kong during and after the Umbrella Movement. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Pinheiro, A. C., S. O. Sequeira, and M. F. Macedo. 2019. “Fungi in Archives, Libraries, and Museums: A Review on Paper Conservation and Human Health.” Critical Reviews in Microbiology 45 (5–6): 686–700. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2019.1690420.

- Qin, A. 2016. “Keeping Hong Kong Protest Art Alive Means Not Mothballing It” The New York Times 13 May.

- Repucci, S., and A. Slipowitz. 2021. “Freedom in the World 2021: Democracy under Siege.” Accessed 29 January 2022. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege

- Sellie, A., J. Goldstein, M. Fair, and J. Hoyer. 2015. “Interference Archive: A Free Space for Social Movement Culture.” Archival Science 15 (4): 453–472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9245-5.

- Shepherd, E., and G. Yeo. 2003. Managing Records: A Handbook of Principles and Practice. London: Facet.

- Strumpf, D. 2020 “Hong Kong libraries pull books for review under China’s security law.“ The Wall Street Journal, 5 July.

- Tang, T. Y.-T. 2021. “Collective Memories, Emotions, and Spatial Tactics in Social Movements: The Case of the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong.” Emotion, Space and Society 38: 100767. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100767.

- Viebach, J., D. Hovestädt, and U. Lühe. 2021. “Beyond Evidence: The Use of Archives in Transitional Justice.” The International Journal of Human Rights 25 (3): 381–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1853534.

- Walker, T. 2021. “Hong Kong Civil Society Keeps Shrinking.” VOA News, 7 October.

- Watson, S. 2010. “Community Archives: The Shaping of Memory.” The International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (6): 530–532. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2010.510662.

- Wenweipo. 2015. The Truth about Hong Kong’s “Color Revolution” [Gang Ban Yan Se Ge Ming de Lai Long Qu Mai]. Hong Kong: Wenweipo Press.

- Williams, C. 2018. “Understanding Collection at Risk.” Archives: The Journal of the British Records Association 53 (136): 45–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/archives.2018.4.

- Wong S H-W and Liang J. (2021). “Dubious until Officially Censored: Effects of Online Censorship Exposure on Viewers’ Attitudes in Authoritarian Regime“. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 18(3), 310–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2021.1879343.

- Yiu, P., and A. Katakam. 2021. “In One Year, Hong Kong Arrests 117 People under New Security Law”, Reuters, 30 June.

- Yuen S. (2018). “Contesting Middle-class Civility: Place-based Collective Identity in Hong Kong’s Occupy Mongkok“. Social Movement Studies, 17(4), 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1434501.

- Zhao, H., and J. Liu. 2015. “Social Media and Collective Remembrance: The Debate over China’s Great Famine on Weibo.” China Perspectives 1 (1): 41–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.6649.