ABSTRACT

This article introduces an intervention framework to build the capacity of Lebanese youth to participate in effectively preserving Beirut’s heritage. Despite the current sectarian politics, enabling the youth to voice their narratives of the lived everyday contestation could herald their substantial contribution to the city’s urban reconciliation and peace-making process with the past. Through interviews and focus groups within the wider academic community, NGOs, and activists in Lebanon, the youth reflected on their interpretations of contestation and which elements of the local contested heritage are authentic. We argue that such authenticity is gained through lived space and experience, as we engage with emerging work that grasps authenticity as a subject of performance, negotiation, and experience.

Introduction

Beirut has not yet fully recovered from Lebanon’s long Civil War (1975–90) and the extreme political events prompted by the assassination of the former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in February 2005. The international community’s response to the erasure of social memory has been predominantly reactive, with no long-term plans to change the underlying factors. With time, the political instability produced intolerance and controversial discourses about the Lebanese youth’s cultural identities. War violence remains a significant point around which modern narratives revolve; the echo of fifteen years of war and the events that followed emerge as sounds of grief in every building, street, and neighbourhood to inform the collective perception, knowledge, and awareness of this history. One can hardly escape this imprinted culture given the still-standing buildings and public spaces of Beirut that display war memories and reveal the country’s political conditions. Beit Beirut, for example, is a museum and urban cultural centre that commemorates the war. The war-torn building became Lebanon’s first memory-museum, after activists turned it into an exhibition space. It highlights a claim to authenticity and presents an inquiry of what an authentic narrative might tell of the history of conflict by provoking a diverse and unpredictable effective response. Furthermore, through spatial and compelling work, the contiguity between content and context is likely to expand, rather than curb, the various emotional reactions that each building could evoke in the people in Lebanon.

The pursuit to learn from and move beyond the past in Lebanon remains a ‘politicised arena driven by the power of memory cultures and competing regimes of memory vying for representative forms and interpretative power’ (Larkin and Parry-Davies Citation2019). Furthermore, how social groups in Lebanon engage with their contested pasts is central to the emotional and mental study of conflict. For many, the past is a legitimate vehicle for connecting with the uncertain future of post-conflict cities, underlining the need to study these cities’ contested heritages (Salibi Citation1988). Nora’s Les Lieux de Mémoire – site of memory – explains how contested claims to local powers are strongly supported by remembrance practices (Nora Citation1989). Memory performance invokes prior temporality to signal buildings, streets, and public spaces to commemorate traumatic events. Scholars such as McDowell and Braniff (Citation2014) have stressed the impact of the enduring trilogy of memory, space, and conflict on peacebuilding and the crucial role of memory during the healing process among post-conflict groups. However, the vital role of space and memory in building potential reconciliation is contested given the apparent tendency among ruling powers to disregard the past and its memoryscape at a societal level.

This article contributes to the scholarly debate on the role of the youthFootnote1 in preserving Beirut’s memory to advance its recovery on the level of both its physical urban reform and its national collective rebranding (Haugbolle Citation2010). The collective amnesia thesis is even more dubious given recent studies on collective commemoration and remembrance (Khalaf Citation2006) that challenge such collective memory and strive to unravel the ‘performance of different groups within the collective’ towards the past (Puzon Citation2019). This work transcends the ongoing discourse that portrays the city as a nostalgic longing that cannot manage its cultural heritage (Nagle Citation2017). We must understand how the post-war youth engages with Beirut’s contested heritage, how they encounter the city, what stories and narratives they tell; and how the remnants of conflict and war in the city might build their identity and pride in the past.

This article emerges out of the project, (Re)contextualising Contested Heritage (ReConHeritage), funded by the Research England Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), between the University of Leeds (United Kingdom) and the Beirut Arab University (Lebanon). We investigate how memorising history involves overviews and inclusions that fit a temporal setting. This, in turn, requires a process that repetitively reviews Lebanon’s collective identity and facilitates the envisioning of a collective future. Our overarching goal is to create a virtuous cycle that enables the youth, as key actors, to protect their local cultural heritage and foster greater value for these assets. How can the youth better draw upon their heritage to highlight commonalities, cultural linkages, and an educational understanding that can transcend the ideological barriers and build sustainable peace? Can innovative approaches and tools for creative and skill-based arts and education provide access to the youth to empower spaces for co-designing inter-culture dialogue to address these challenges? How can new historical narratives shape the future? Finally, how can tangible heritage emerge within these historical narratives? We also argue that the authenticity of contested pasts is gained through lived space and experience, as we engage with emerging work that grasps authenticity as a subject of performance, negotiation, and experience.

To answer these questions, we developed a framework for interrogating the contested heritage of Beirut. Despite the sectarian politics in action, enabling the youth to voice their narratives of the lived everyday contestation could herald their substantial contribution to the city’s urban reconciliation and peace-making process with the past. Hence, ReConHeritage first aimed to deliver youth-centred capacity building by developing innovative digital platforms through plural participatory approaches to boost community resilience and develop channels for nation-rebuilding after the conflict. This supported the development of a research-led interactive digital platform. This platform aimed to build new cultural exchange venues for young people and institutions to share and translate cultural responses to ideological conflicts and developmental challenges. Second, the project aimed to strengthen the role of cultural institutions as promoters of human equality and social justice; these institutions open new channels for the youth’s voice after years of challenge in fragile states. We examined best practices and new avenues of collaboration that bring education development into play. Furthermore, we conducted interviews and discussions, enabling the youth to reflect on their interpretations of contestation and the authentic elements of the local contested heritage. As such, we understand authenticity as an embodied experience and emotional attachment to a place derived from the everyday practices of young generations (Zhu Citation2015). Moreover, we employed participatory arts and humanities research methods to establish a specialist task force of academics and non-academics. Thus, we could collate multiple views and practices with over 65 semi-structured interviews with academics; youth activists who are members of non-government organisations (NGOs) and cultural institutions (curators, architects, practitioners, and activists); and ten students from the School of Architecture at the Beirut Arab University.Footnote2

The article begins by situating Lebanon within the context of its contested heritage. It interrogates Beirut as a contested city and analyses how the heritage debate is lived and interpreted as an authentic element of the community in Lebanon. The final section presents the methods and framework to enable positive outputs for the youth’s engagement with their heritage.

The contested memories of resurrection in Beirut

… wiping out totally [the] past and just saying, let’s look at the future and forget about anything that happened before that, [is] a truly dangerous statement because it leads to a general amnesia and … disconnection between the younger generation and what happened … it’s really about connecting. A(1)

Beirut exemplifies a war-torn city, displaying contradictions within its neighbourhoods and streets that reflect the paradox of war and peace (Cobb Citation2010). The city has been repeatedly invaded and destroyed throughout its modern history during episodes of civil conflict (1975–1990), the Israeli invasion in 1982, and the bombing of the city in 2006 (Nasr and Verdeil Citation2008). The traumatic post-war context heavily shaped the recovery of its historic core. The ‘violent post-war reconstruction’ was regarded as ‘a property development operation for one part of the city that led to the erasure of the pre-war past and the entrenchment of socio-spatial hierarchies’ at a colossal scale of change (Puzon Citation2019; Sawalha Citation2010).

This highlights the danger of expunging Beirut’s contested memory and wiping out its historic buildings, disintegrating its past. However, the state adopted a strategy of amnesia, erasing any mention of the war; its manifests in the efforts to rebuild Beirut (Barak Citation2007). While it permitted mega projects by Solidere to restore the destroyed city, it halted the efforts to build a civil war memorial and erased some of its traces (Larkin and Parry-Davies Citation2019) – a widely contested policy. Khalaf (Citation2006) used ‘collective amnesia’ to describe the predominant disposition regarding the conflict in post-war Lebanon, while others unambiguously held the state responsible for purposefully emboldening this atmosphere. Scholars such as Dagher (Citation2000) and Young (Citation2000) highlighted the local, national amnesia in Lebanon, arguing that the reconstruction took place on account of state-sponsored amnesia. The demolition of war-torn buildings in Beirut was described as an attempt to ‘physically rewrite’ Lebanese history (Makdisi Citation1997).

A plethora of literature focuses on the memory of Beirut’s public spaces (Harb Citation2018; Larkin Citation2010; Puzon Citation2019), since the role of memory substantially influences the city’s collective identity and psyche. Indeed, a sense of loss serves as an everlasting narrative that has become a part of the city’s identity and history. Each seemingly isolated violent incident denotes a history of a battle informing the future generations in Lebanon – each a brief segment in a long story of contestation. A remarkable, painful memory of the city evolved along the green line, dividing Beirut into a Muslim West and a Christian East during the Civil War, where Beirut’s contested heritage resides. According to Möystad (Citation1998), this division ‘turned identities into territories’. Along this line, most nearby buildings were severely damaged. After the war, many were rebuilt; however, the war had a profound psychological impact on the souls of the Lebanese. In addition to the green line, a few remaining facets of the war are central to Beirut’s contested heritage; the Lebanese team of the funded project analysed these.

Lebanon’s youth, or its ‘lost generation’, grew up during the last nine years of the Civil War. ‘They were just waking up on the world, just starting to read the newspapers, when the war blew away their adolescence before they even knew it was gone’ (Friedman Citation1984). For many years, their life was constructed through ‘fragmented lenses, and [they have been] recipients of policies that are partial, unresponsive, and often irrelevant’, whereby they are not perceived as agents of societal and political change (Harb Citation2018). Given the complex cultural situation, the Lebanese youth often reproduce traditions and cultural and religious divisions and are subject to various systemic barriers. For instance,

[they] stay within their religious sector, [they] live in an area that is nearly homogenous in terms of sector (which is the case for most of Lebanon except for some areas in Beirut), [they] go to school with children of their own sector, and [they] perform all the activities within the same sect. (Y.11)

The youth can only start overcoming these systematic barriers when they reach university age. They move among three clashing identities, according to mobilised interest and resources. They are strongly sensitive both to the culture of their community and the global mass culture elements conveyed by modern channels of communication technologies. Although they did not personally experience the war, the youth are still experiencing the repercussions and reproduced accounts of conflict. They have been witnessing the war’s unfolding imprint, not only through sectarian and political enmity but most notably through the city and its built form. Most of them perceive Lebanon as a foreign country and feel a lack of identity and emotional attachment. The Syrian (1976–2005) and Israeli occupations (1982–2000), coupled with the division of Lebanon into sectarian cantons – a Muslim West and a Christian East Beirut – have rendered some parts of the country off-limits to virtually every Lebanese community (Friedman Citation1984). The volatility of these events and the ensuing sectarian tensions resulted in the redistribution of demographic populations across the urban landscape of Beirut and Lebanon in general.

Scholars from various backgrounds and disciplines, such as historians, artists, and psychologists, believe that future generations should be informed and engaged with their contested pasts to better understand their current reality and the possibilities for the future. While the Lebanese state and its political institutions were exercising their utmost effort not to ‘mention the war’, civil society groups pledged to keep its memory alive (Barak Citation2007). A member of Nahnoo, a local heritage NGO, mentioned that

The youth need memories from the past … the amnesic Phoenix memory is crucial when [you] speak about heritage. We are wrongly very proud that we will rise again like the Phoenix from the ashes; well, but we are rising without any memory, and that is a big problem. (A.2)

When the youth are not involved in reconciliatory initiatives nor allowed to develop trusted, reliable narratives to navigate their history, they become vulnerable to political manipulation and more likely to engage in violence.

The youth’s memory of Lebanon’s heritage

Relating cultural heritage assets (both tangible and intangible) with stories and living values will facilitate the connection of youth to them. Before that, the heritage context should be prepared to answer their needs spatially and socially. (A member of Nahnoo)

Notably, in the past decade, heritage actors and supporters have shifted to comprise a younger generation through several NGOs. According to Barak (Citation2007), these groups implemented initiatives focusing on public forums and research activities to involve the general public in creating dialogue, raising awareness, and informing action. Most of this work targeted groups that experienced the conflict (59 initiatives), while half of these projects targeted the youth. These initiatives were oriented towards gathering insights from the youth in a post-war city. Lefort (Citation2020) interviewed 13 Lebanese students and asked them to mark the places that held a special meaning for them and to expose the social dynamics shaping their experiences of Beirut on collaborative maps. Other projects involved different stakeholders exchanging views related to youth engagement. For example, UNESCO Beirut organised a Management of Social Transformations (MOST) school activity focused on youth civic engagement and public policies for urban governance through cultural heritage. These activities were based on field visits and interactive sessions that provided the young participants, alongside experts, a platform for sharing experiences (MOST Citation2019). An additional initiative, the Youth Engagement Index in Beirut, applied a collaborative method for measuring youth participation in the affairs of Beirut City. This method involved local stakeholders and 28 young participants; they conducted personal interviews with institutional representatives to identify and discuss the public sector’s roles and actions in implementing a youth policy (Chemali, Maci, and Makki Citation2018). The absence of a Lebanese national history curriculum and the lack of educational tools addressing the Civil War period have contributed to the youth’s marginalisation in the dialogue regarding the past and the need to document and discuss this memory.

The project engaged with 10 young participants (out of 65) from the Beirut Arab University, recruited via an open call led by our local partner with four focus groups. Participants engaged in training focused on documentation as a means of plural participation to generate a public memory that could enable the younger generation to revisit the assumptions about the past and share these experiences via social media platforms and public displays. We implemented a methodology that enabled the participants to go beyond the collective memory and become more critically analytical of the bases for their identities. The choice of building/space was integral to the unique aide-mémoire story of each participant that builds spatial contiguity, the memory of war, and layers of historical conflict. We claim that these spaces hold memories, ‘that trauma inheres in place, that there is a dimension of congruence between features of the landscape and narratives invoked’ (Clark Citation2015).Footnote3

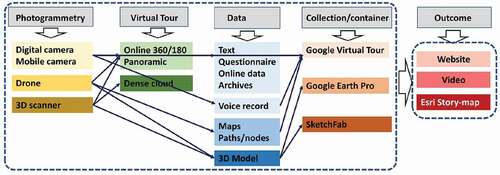

Producing digital heritage resources is unique to human knowledge and expression, ‘created digitally or converted into digital-form from existing analogue resources’ (UNISCO Citation2003). Digital content can either be ‘born digital’ (e.g. electronic journals, worldwide webpages) or ‘digital surrogate’ (made from analogue resources such as three-dimensional (3D) scanned objects or digital video of a ritual). Moreover, digital content is more durable, reaches a broader audience, and is interactive and allows for feedback. Thus, we created a digital platform that allows the youth to engage in dialogue around the city and its visible built environment contestation (oral history, testimonies, documentaries, etc.). We also combined historical inquiry with digital platforms to reconnect them with their past and built heritage through the co-production of online content such as photogrammetry modelling using their mobile cameras, creating 3D models or virtual tours of buildings, interactive story maps, and short films. We aimed to create a virtuous cycle whereby heritage is interrogated by building cultural bridges that include the youth as the key actors, which will, in turn, be strengthened by promoting the value of the cultural heritage, see ().

Figure 1. The digital tools and techniques used in the workshop. The lighter colours denote affordable digital tools; the darker colours denote more expensive but accurate tools.

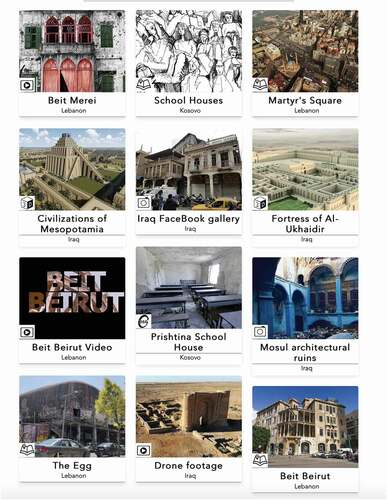

Figure 2. Outputs produced by young participants, as displayed on the digital platform. (https://www.reconheritage.co.uk/case-studies).

Interpreting ‘our’ heritage

I dream of a city that nurtures our ambitions instead of slaying them in the womb. A city where racism has no place and indifference is an impossible word. (Chemali, Maci, and Makki Citation2018)

Heritage is often ambiguously described as a set of attitudes and relationships with the past (Harvey Citation2001; Walsh Citation1992) which similarly shapes the present to reflect inherited and present concerns about the past (Harrison Citation2013). Heritage also involves engagement and communication practices to broadcast values, knowledge, and ideals that materialise the tangible and intangible (Graham Citation2002; Smith Citation2006). Its interpretation depends on an individual’s spatial literacy, subjectivity, and cultural positioning (McCullough Citation2004). The perceived value of specific content differs by person and often results in heritage dissonance (Tunbridge and Ashworth Citation1996). Thus, with linear narratives, users fail to grasp the inherent significance of heritage, such as place-specific physical artefacts or architectural memorials, and their relationship with much broader non-visible cultural processes of which they are a part.

In Lebanon, like elsewhere, heritage exists through communal practices, sediment legacy-based knowledge, and values; heritage is fundamental for building a sense of community. Aware that the collective heritage is vanishing, the local academic community is trying to recall and re-centre the heritage discourse through the self, asking questions such as: What architectural forms can empower this legacy, and what meanings does heritage have in the modern societal contexts? In fact,

[We] do not have to live in the novelty of a bright future any more than we must hide behind reassuring pastiches of the past … [We] must live in a perpetually evolving present, motivated by the possibilities of change, with the baggage of the past and the experience as a safeguard. (A.21)

The scarred buildings in Beirut ‘transmit a perpetual feeling of understanding where we come from and of the collective riches and ideals of the culture’, and it pins ‘the place where people come from, once lived in, and the role of this place in defining them’ (A.4). Their maintenance requires expertise, technology, time, and capital that are not always available for projects that do not immediately revert to the ever-expanding progress of society. The war still portrays ‘the community’s collective legacy’ of the youth’s unlived childhood but remains a memory ‘passed on to the next generation and the general public’ (A.5). However, this heritage matters because, for

the people lack that anchoring … that identity … that sense of community … [it] is the glue that holds us all together … culture and heritage are about people, and things that are important to people; so, when you make it a culture conversation, you are making it a people conversation. (A.17)

Born after the war, the youth does not understand many scenes of its past in relation to the city’s aesthetics and the built environment. The youth group who visited Beit Beirut, for example, did not recognise the Lebanese Forces symbol graffitied on the walls, ‘as it was [their] first time going there’ (Y.4). Touring the building and making 360° interactive images and short films allowed them to develop interpretations of the past: ‘As grasping what they represent provides an opportunity to have a fresh start; the youth need, more than ever, to stick to their heritage’ (A.8). The bullet holes on the walls of Beit Beirut added a visual uniqueness: ‘The building stands like an injured and silent person who wants to tell a story of pain and sorrow’ (Y.15). In their perspective, the building stood against the widespread and sweeping norms of modernisation in the city [referring to Solidere], ‘which [we] like as architects interested in heritage, but it also stands against globalisation which produces prototype products everywhere’ (Y2). Older generation architects in Lebanon reveal a nostalgic association with the building and recite their stories and memories during and after the war. Over the years, some developed an inclusive archival collection of images and architectural drawings of Beit Beirut. While the ruins induce ‘the most powerful prompt of the memory of contestation’, the visuals an interviewee displayed provoked discussions about an elapsed past between two generations that do not know about each other’s experience during the war (A.9). Across the street, Beit Meri, which represents the other group along the green line that fought against those occupying Beit Beirut, went unnoticed. The participants were unaware of the building’s history. The distant and recent past are the only certain things to understand, learn, and initiate a better future from in Lebanon ().

Sometimes, heritage is used in Lebanon to challenge dislocation from past divisive ideologies or to found a shared cultural legacy. The Egg, an egg-shaped cinema-shopping complex built during the 1960s in downtown Beirut, barely survived the Civil War and has been vacant and unrestored since. Every few years, the building was threatened with demolition but always rescued by activists who fought for its preservation and repair. It was revived during the 2019 uprising. Professors held seminars; activists screened Lebanese films and documentaries; and artists painted graffiti on the walls. It was transformed into cultural and creative activity centre in a few days and became a youth revolution icon.

Moreover, some buildings and squares in Beirut, such as the City Palace and the Grand Theatre, gained their cultural value due to youth demonstrations during the garbage crisis in 2015. Due to the successive participation of the younger generation in rallies and protests against the state or a political faction, the Martyr’s Square has become more of a revolution symbol than a historically significant square. Consequently, when most of the young participants began the field survey in the square, they were ignorant of its historical significance or the reason why it has attracted most protests throughout its long history.

In 2008, a group of architects including George Arbid, Nada Habis Assi, Bernard Khoury, Hashim Sarkis, and Jad Tabet established the Arab Center for Architecture (ACA) to raise awareness about architecture and urbanism within civil society and provide a public forum for debating the present and future of architecture and cities. The centre introduced a new programme in 2015 named ‘Discover, Visit, Debate’ to raise awareness for students and initiate a platform for discussing the modern built heritage. The programme also included monthly guided tours by urban and heritage professionals to explore new perspectives relating to several neighbourhoods and sites in Beirut. In the interviews that we have conducted, Arbid claims that the role of the youth in safeguarding heritage must be passed on from one generation to the next. Such intergenerational dialogue and continuity enables ‘critical debates about what changed across time in the profession and what is finally relevant to keep … knowledge is not only about an architect knowing how to sue stone, concrete and glass, but it’s about the practice … and practice is also heritage’ (A.6). Less than ten years ago, national governmental universities in Lebanon, such as the Lebanese University, started running heritage conservation programmes. Private universities also started to establish centres such as the Center for Lebanese Heritage at the Lebanese American University (LAU), or labs such as the urban labs found at both the American University of Beirut (AUB) and the Beirut Arab University (BAU).

Some owners of war-buildings attempted to sell these buildings, despite the steady resistance from multiple activist groups who aimed to maintain the city’s social fabric against frenzy construction (Fawaz Citation2020). For example, the Save Beirut Heritage group supported owners in finding solutions to avoid selling to developers who would destroy them to reconstruct profitable mega projects. Beit Beirut, for instance, constitutes one example of a symbol of war turned into a space of remembrance. Activists described how, after 2 August 2020, the explosion of the Beirut Port, property developers were already on the ground; ‘news of investors … agents going around the street trying to take advantage of what happened and the people’s weakness at that time’ (Chahine Citation2020). The hashtag and slogan, ‘Beirut Is Not For Sale’, surfaced online and on the walls of the damaged neighbourhoods. UNESCO also launched the ‘Li Beirut’ initiative as an international appeal to raise funds to support the rehabilitation of schools, historical heritage buildings, museums, galleries, and other creative economies affected by the blast (Chahine Citation2020).

Building participatory heritage

We conducted 65 interviews with academics from various schools of architecture across Lebanon. Three focus groups were organised online (due to COVID-19 lockdowns) as half-day seminar/workshops; each group comprised a mix of expertise and backgrounds (curators, architects, practitioners, and activists). We asked four core questions to each to stimulate the conversations:

Q1. How do you define cultural heritage (tangible and intangible)? Why is cultural heritage important to you as an individual or a group (memory, identity, etc.)? Why does heritage matter?

Q2. Why should young people engage in protecting their heritage? Why would their voices and actions make a difference? Why now?

Q3. What is the current role of the youth in understanding the value of the past? What skills and practices are in place? What challenges do they face? What tools do they need to support them?

Q4. How can we work in a better interdisciplinary way to motivate youth to engage? What are the main resources we need (educational/non-educational)? What are the challenges, and who are the potential players in this? (institutional, societal, etc.)

The discussions revealed the integral role of educational institutions in engaging young people with their contested past (). For the youth, the proper channels and tools to express their ‘attachment’ should reflect their need to engage with the past and communicate with their surrounding context in a simple and direct manner. Complicated technologies are unnecessary, except for free tools/applications (if needed) to communicate with others and share their ideas with the larger community. This interaction took the form of projects, personal reflections on areas/buildings, or organising online campaigns/events. Hence, the role of the institutions varies, from being a facilitator providing capacity building for youths by organising workshops and events to engaging them in the decision-making process about preserving or reusing heritage buildings and their surrounding context. The institutions’ role is essential in increasing and organising youth engagement, which increases the youth’s sense of belonging and the value they give to their cultural heritage. Hence, three main subthemes emerged around education, engagement, and digital tools.

Table 1. Key parameters and outcomes from the focus groups and workshops.

Participation and engagement

Young people bring fresh ideas and enthusiasm to heritage projects … they will be the ones who look after heritage and pass it on in their turn. For young people, involvement brings opportunities to develop new skills, interests, and aspirations to connect with their wider communities. (A.10)

Youth engagement is applied in different fields such as education, community, and research. One of these fields is protecting and preserving ‘cultural heritage’ among tangible and intangible features. Some participants claimed that their voices are ‘not heard’ and that they ‘hear’ about their heritage but do not ‘live’ it, creating a feeling that heritage is imposed on them (Y.1). As a result, they become detached from their heritage: ‘like something pulling them down … . And the importance of our past should be experienced first-hand, not passed down’ (Y.9). The challenge is to link this heritage (tangible and intangible) with their stories and living values.

Furthermore, young participants claimed that, due to globalisation, they are disconnected from the context in which they live (Y.3,6,7). There has been a ‘memory hole’ and general amnesia after the war, causing a rupture between the young people and their cultural heritage. Furthermore, there is a rupture between the youth and the older generation, with a clash of ideologies between the past, present, and future. The younger generation feels that the older generation constantly criticises their views for adopting what they perceive to be shallower values and beliefs, which generally leads them to adopt a defensive state of denial, culminating in a clash between the two generations. An advantage noted was that ‘the COVID-19 pandemic has helped the youth reconnect with their villages by learning about their roots’ (A.4). Heritage actors and supporters, including the Save Beirut Heritage, Nahnoo, and other NGOs in Lebanon, have notably shifted to the younger generation (A.2). Digital actions, according to the experts, can serve as documentation and dissemination while creating a physical distance. They have the potential to balance the old and new, and their wide reach may be a powerful asset in preserving heritage. For young people, involvement brings opportunities to develop new skills, interests, and aspirations and connect with their wider community.

The youth needs training to participate in decision-making; however, helping them implement their ideas is essential in establishing a link to their heritage. For example, the ‘Our City Our Way’ project hosted 30 young participants (aged 13–17) from different parts of El Mina City, North of Lebanon, Tripoli. Its aim was not only capacity-building or designing a framework for youth participation but also demonstrating youth community participation in realising a designed vision in an unused interstitial space in the historical part of El Mina City. A series of 15 workshops and cultural training processes led the participants to proactively understand the key urban functions and to design and implement their vision in an actual site (Mohareb, Elsamahy et al. Citation2019).

Skills and challenges

Images from the past are reaching our generation in a diluted form. Youth ought to save these images in hope of saving them from being erased. (Y.14)

The Lebanese academic institutions hold the primary responsibility for raising awareness about the value of the past, whereas ‘the education sector makes a minor, inadequate contribution in this field’ (A.2, 4, 6). The youth must ‘understand the worth of the heritage through start-ups related to the heritage that is appearing notably in these tough times in Lebanon’ (A.5) such as the ‘Tourathing – Protecting our Future’ project, a youth-led venture promoting local heritage in six rural and urban areas within Lebanon (Zahle, Bikfaya, Beit Chebab, Salima, Tripoli, and Sarafand) by addressing both heritage and social needs. Thirty young volunteers were recruited to work with three NGOs, Nahnoo, Arcenciel, and Biladi, to build a management and marketing business to promote this heritage. They were provided training workshops in photography, writing, video-making, oral history recording, and creating interactive websites. According to a study conducted by Out_of_the_box (Citation2017), there was a general lack of youth leadership in local heritage identification and documentation, which led to a lack of youth engagement in promoting local cultural heritage. Although the youth were interested in participating and motivated to learn about their local heritage, many had superficial knowledge about it, learned from their elder community members or families. Perhaps, this is a consequence of the war and conflict that damaged generational links and the understanding of cultural heritage and landscape, whereas members of the older generation want to avoid the unresolved past.

Youth skills in cultural heritage identification and documentation were useful due to their perspectives about heritage’s value for them and their communities. However, they lacked skills in marketing, tour guiding, and storytelling. Yet, they were motivated about using digital tools such as social media.

Adaptive reuse design studios are becoming an exemplary scheme for developing new programmes in architecture schools, which could be applied in other disciplines as well. Schools offer electives related to the heritage, depending on the availability of expert instructors; hence, this issue needs a new strategy of intervention (A.2). Digital communication techniques, as used in teaching during COVID-19, connects young people with experts from any location at a lower cost via mobile phones and the Internet. The current generation depends more on digital gadgets for their learning and communication; therefore, it is better to provide them with supportive tools that suit their current lifestyles.

The UNESCO-Beirut Office and a local NGO, Biladi, for example, delivered an initiative to increase the awareness of 1,600 students (aged 11–15) about protecting heritage in times of war and learning more about heritage protection through hands-on skills such as creating artefacts (Unite4heritage Citation2015). This approach enabled the youth to learn on-site skills such as creating mosaic and class activities. More recently, the World Monuments Fund adapted this approach, and the outcomes have been acknowledged through the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund Award to establish the programme in Tripoli, Lebanon in 2020. The young participants attained valuable skills, developed relationships with professional colleagues, and reinforced their commitment to cultural heritage through site training with a focus on the basics of conservation, stonemasonry, and general conservation (World-Monuments-Fund Citation2021). Furthermore, a team from the Beirut Arab University and the UNFPA-UNESCO-UNODC investigated the youth’s emotional attachment to their heritage in response to the Beirut Port explosion (UNESCO Citation2020). Using a gaming environment approach to promote youth-led initiatives, they developed a spatial map-board strategically designed to be filled with 3D wooden parts of historical buildings’ models that could be disassembled and assembled, using architectural vocabulary from the Lebanese architectural heritage available in Beirut.

Motivation and empowerment

When irreplaceable memory sites and cultural expressions are increasingly under attack, awareness, particularly among youth, must be raised to draw attention to the importance of cultural diversity and improve knowledge of world cultures (A.12). Enabling young people to participate in community life and educating students to become global, accountable citizens is crucial to create a fairer, more sustainable, and more prosperous society. Digital technologies and the Internet influence how cultural diversity is communicated and interpreted and how young people learn and express themselves. Therefore, they could help counter radicalisation, including by safeguarding heritage and education for global citizenship.

In Lebanon, local NGOs are more active and dynamic than the governmental agencies in motivating the youth to engage in activities related to cultural heritage. These activities are individual efforts by NGOs and international agencies, such as the United Nations, where the relevant international agency’s vision tends to be applied. The government has no clear strategy for engaging the youth, and there is no collective archiving process that highlights the accomplished targets and maps the problems or gaps in the activities (A.5). Therefore, a wide range of stakeholders, such as educational institutions, museums, ministries, and local municipalities must be involved to develop a local network that can publicise projects, funding, courses, and other related opportunities as well as document the relevant activities. This network would be more effective if integrated within related international networks. Moreover, heritage learning must be interactive and easily accessible; for example, heritage could be implemented in the gaming world using application-based software.

In general, through this work, the youth and the local community members identified vital shortfalls. They are knowledgeable but ‘lack understanding and knowledge of the detailed information’ (A.6). Most learn about the past through families or older people; however, this intangible form of certification of the past has become less frequent. It is important to ‘provide knowledge, leadership skills, and the proper channels and platforms to allow their voices to be heard and to enable them to become active citizens’ (Y.12). The youth and their communities are less interested in protecting and/or promoting their local cultural heritage features, as they suffered from growing political instability and insecurity. Moreover, the main intergenerational and social divisions remained, endangering local cultural heritage projects.

This changed after the explosion of the Beirut Port, as the youth were the main force on site, providing help to the injured and assisting in removing the rubble. Given the soulless nature of the neighbouring downtown area that was once before overtaken by the Solidere projects for redevelopment after the Civil War, people, especially activists, were already aware and cautious of what would happen to the neighbourhoods famous for their social sphere and beautiful ambience, namely, Mar Mikhael and Gemmayze neighbourhoods. The youth joined efforts to voice their opposition against wealthy investors who aimed to acquire the damaged or semi-damaged historical buildings at cheap prices, which would not only gentrify the area but also render it inaccessible to its original residents and complicit to the erasure of a social fabric. As such, this catastrophe has emotionally affected and motivated the youth to engage in public activities and with their public realm. The most remarkable activity was the preliminary documentation and assessment of damaged buildings and their surroundings, coordinated by multiple schools of architecture based in Beirut (Order-of-Engineers-and-Architects-in-Beirut Citation2020). Most of the site surveys were conducted by architecture students using digital techniques. The Beirut Urban Declaration outlines the course of intervention and the role that the Order of Engineers and Architects (OEA) could play in cooperation with the universities and their students in envisioning the reformation of the damaged area as an urban fabric fully integrated with the port. Consequently, the universities included courses, projects, and extracurricular activities tackling how to deal with damaged historical and old buildings and the urban fabric. This activity increased and re-established the connection between the youth and the historical parts of the city.

Conclusion

This article discussed how the Lebanese youth can draw upon their heritage to highlight commonalities, cultural linkages, and the educational understanding that can transcend the ideological barriers and build sustainable peace. Youth engagement has been achieved in this project on two levels. First, the project raised awareness through open discussions with stakeholders; second, it obtained the insights of relevant institutions and the youth. The training workshop on digital technologies helped to enhance the youth’s capacity building, as they disseminating their stories based on real case studies and published their work on well-established digital platforms. This work provided the youth and related stakeholders with the tools and framework to more closely engage with their cultural heritage. The priorities for cultural heritage research emerged through a critical dialogue, leading to the design of research programmes based on capacity building and critical discussion, involving the youth and other stakeholders, including experts, NGOs, and government bodies. Cultural heritage research has a vital, inclusive role in helping people to understand and sensitively deal with the needs and motivations of diverse communities and groups.

The suggested framework covers two sections: (1) the priorities for cultural heritage research and (2) an outline of specific ‘areas of intervention’, namely, the instruments that should support the results of this research to produce actual innovation, impact, and growth. We must take advantage of the globally accessible digital networking to spread the youths’ narratives and ideas to the larger communities, crossing all borders. We must understand how heritage interpretation and shared historic experiences can contribute to an enhanced sense of attachment and common dialogue among countries facing similar challenges, and develop ways to formulate an inclusive heritage discourse by facilitating multi-perspective, authentic interpretations and approaches in history and memory research and education. The type of partnership and collaboration exemplified in this work offers mutual benefits on different levels. Young people benefit from listening, discussing, sharing, and learning from experts from different cultural and educational backgrounds. Future work must include individuals from younger age groups, such as from high schools, cultural centres, and NGOs that involve the youth in their activities. Moreover, collaborating with young entrepreneurs will boost the quality of the outcomes and encourage other young people to engage. Indeed, regarding youth engagement in Lebanon, there are still many challenges to be addressed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gehan Selim

Gehan Selim is Professor of Architecture at the University of Leeds. She was Fellow of The Senator George Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice (2017/18). Her interdisciplinary research bridges between Architecture, Urban Politics and Digital Heritage. Prof Selim is leading several funded research projects with an extensive portfolio of empirical research in the global south. She is the author of ‘Unfinished Places’ (Routledge, 2017) and ‘Architecture, Space and Memory of Resurrection in Northern Ireland’ (Routledge, 2019).

Nabil Mohareb

Nabil Mohareb is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture in the School of Sciences and Engineering (SSE) at the American University in Cairo (AUC). Former Director of the Faculty of Architecture – Design & Built Environment at Beirut Arab University’s Tripoli Campus in Lebanon. He has worked for prestigious universities in Egypt, the UAE, and Lebanon. He was a Fellow of the Heritage Program Fellowship Liverpool (2020/21). His research focuses on the relationship between architecture and urbanism, emphasising social behaviour activities and their mutual effects on spatial and economic variables in urban spaces.

Eslam Elsamahy

Eslam Elsamahy is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Architecture- Design and Built Environment at Beirut Arab University, Lebanon, loaned from the Architectural Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, Alexandria University, Egypt. Received his Master of Science and Ph.D. in architectural education from Alexandria University, Egypt. He has many published papers in the field of architectural education and the relation with Mixed reality and digital game-based learning, in addition to environmental design studies and participatory design.

Notes

1. The article uses ‘youth’ and ‘young people’ interchangeably to mean people aged 15 to 24. We adapted the United Nations Report (Citation2021) on ‘Policies and Programmes Involving Youth (A/76/210)’: ‘youth is best understood as a period of transition from the dependence of childhood to adulthood’s independence. The term “youth” is more fluid than other fixed age-groups. Yet, age is the easiest way to define this group, particularly in relation to education and employment, because “youth” is often referred to a person between the ages of leaving compulsory education and finding their first job.’ See the full report: https://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?OpenAgent&DS=A/76/210&Lang=E

2. Interviewees are referenced based on the standard code used in this paper (P.y), where (P) refers the participants type [Academics (A), Youth (Y)] and (y) is the code in the list of interviews.

3. We selected three sites along Beirut’s green line: The Martyr’s Square, The Egg, and Beit Beirut, which are further explored in ‘Digital Storytelling: The Youth’s Vision of Beirut’s Contested Heritage’ (accepted for publication) with in-depth analysis of the sites, youth interaction, discussion and engagement.

References

- Barak, O. 2007. “Don’t Mention the War? the Politics of Remembrance and Forgetfulness in Postwar Lebanon.” The Middle East Journal 61 (1): 49–70. doi:10.3751/61.1.13.

- Chahine, M. 2020. “Not for Sale: Beirut’s Reconstruction Must Prioritise People and Not Profit”. Retrieved 20 February 2021, from https://beirut-today.com/2020/08/19/not-for-sale-beirut-reconstruction-prioritize-people/

- Chemali, J., M. Giulia, and M. Farah. 2018. Youth Engagement in Beirut, Dreams to Action. Lebanon: NAHNOO, URBEGO, Architect For Change, & LOYAC.

- Clark, L. B. 2015. “Ruined Landscapes and Residual Architecture: Affect and Palimpsest in Trauma Tourism.” Performance Research 20 (3): 83–93. doi:10.1080/13528165.2015.1055084.

- Cobb, E. 2010. “Cultural Heritage in Conflict: World Heritage Cities of the Middle East.” ( Masters Thesis). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

- Dagher, C. 2000. Bring down the Walls: Lebanon’s Post-war Challenge. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fawaz, M. 2020. “Beirut: A City for Sale?”. Retrieved 28 June 2021, from https://www.beiruturbanlab.com/en/Details/612/beirut’s-residential-fabric

- Friedman, T. L. 1984. “A New Lost Generation: Lebanon’s Haunted Youth.” The New York Times Digital Archive.

- Graham, B. 2002. “Heritage as Knowledge: Capital or Culture?” Urban Studies 39 (5–6): 1003–1017. doi:10.1080/00420980220128426.

- Harb, M. 2018. “New Forms of Youth Activism in Contested Cities: The Case of Beirut.” The International Spectator 53 (2): 74–93. doi:10.1080/03932729.2018.1457268.

- Harrison, R. 2013. “Heritage Graves-Brown, Paul, Harrison, Rodney, Piccini, Angela.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D. C. 2001. “Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning and the Scope of Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 7 (4): 319–338. doi:10.1080/13581650120105534.

- Haugbolle, S. 2010. War and Memory in Lebanon. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Khalaf, S. 2006. Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj. United Kingdom: SAQI BOOKS.

- Larkin, C. 2010. “Remaking Beirut: Contesting Memory, Space, and the Urban Imaginary of Lebanese Youth.” City & Community 9 (4): 414–442. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01346.x.

- Larkin, C., and P. D. Ella. 2019. “War Museums in Post-war Lebanon: Memory, Violence, and Performance.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 25 (1): 78–96. doi:10.1080/13537113.2019.1565182.

- Lefort, B. 2020. “Cartographies of Encounters: Understanding Conflict Transformation through a Collaborative Exploration of Youth Spaces in Beirut.” Political Geography 76: 102093. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102093.

- Makdisi, S. 1997. “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere.” Critical Inquiry 23 (3): 661–705. doi:10.1086/448848.

- McCullough, M. 2004. Digital Ground: Architecture, Pervasive Computing, and Environmental Knowing. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- McDowell, S., and M. Braniff. 2014. “Landscapes of Commemoration: The Relationship between Memory, Place and Space.” In Commemoration as Conflict, 12–25. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137314857_2

- Mohareb, N., E. Elsamahy, and M. Felix. 2019. “A Child-Friendly City: A Youth Creative Vision of Reclaiming Interstitial Spaces in El Mina (Tripoli, Lebanon.” Creativity Studies 12 (1): 102–118.

- MOST. 2019. Youth Civic Engagement & Public Policies for Urban Governance. Beirut: UNESCO Beirut. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/sv/news/unesco_beirut_holds_a_most_school_on_youth_civic_engagement/

- Möystad, O. 1998. “Morphogenesis of the Beirut Green-line: Theoretical Approaches between Architecture and Geography (Note).” Cahiers de Géographie du Québec 42 (117): 421–435. doi:10.7202/022766ar.

- Nagle, J. 2017. “Ghosts, Memory, and the Right to the Divided City: Resisting Amnesia in Beirut City Center.” Antipode 49 (1): 149–168. doi:10.1111/anti.12263.

- Nasr, J., and V. Eric. 2008. “The Reconstructions of Beirut.” In The City in the Islamic World. Vol. 2, 1121–1148. Austin: Brill.

- Nora, P. 1989. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations 26: 7–24. doi:10.2307/2928520.

- Order-of-Engineers-and-Architects-in-Beirut. 2020. Retrieved 30 June, from https://www.oea.org.lb/Library/Files/events/2021/march%202021/Beirut%20Urban%20Declaration/BUD%20eng.pdf

- Out_of_the_box. 2017. “TOURATHING Protecting Our Future: A Youth-led Approach to the Promotion of Lebanese Cultural Heritage.” Search for Common Ground Team. Retrieved 21 March 2021, from https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Tourathing-Baseline-FINAL.pdf

- Puzon, K. 2019. “Saving Beirut: Heritage and the City.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (9): 914–925. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1413672.

- Salibi, K. 1988. A House of Many Mansions, the History of Lebanon Reconsidered. California: University of California Press.

- Sawalha, A. 2010. Reconstructing Beirut: Memory and Space in a Post-war Arab City. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. New York: Routledge.

- Tunbridge, J. E., and G. J. Ashworth. 1996. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the past as a Resource in Conflict. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- UNESCO. 2020. ”Announcement: UNESCO, UNFPA and UNODC Joint Call for Proposals on Youth-Led Rehabilitation Efforts to Support Local Communities Affected by the Beirut Blast.” Retrieved 21 March, from https://en.unesco.org/news/announcement-unesco-unfpa-and-unodc-joint-call-proposals-youth-led-rehabilitation-efforts.

- UNISCO. 2003. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNIS.

- Unite4heritage. 2015. ”1600 Lebanese Students to Learn About Heritage Protection.” Retrieved 20 March, from https://www.unite4heritage.org/en/news/1600-lebanese-students-to-learn-about-heritage-protection.

- United Nations. 2021. Policies and Programmes Involving Youth: Report of the Secretary-General. United Nations. Retrieved 29 December, from https://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?OpenAgent&DS=A%2F76%2F210&Lang=E.

- Walsh, K. 1992. The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Post-modern World. London: Routledge.

- W.-M.-F. 2021. ”Stonemasonry Training in Tripoli, Lebanon.” Retrieved 20 March, from https://wmf.org.uk/Projects/stonemasonry-training-in-lebanon/

- Young, M. 2000. “The Sneer of Memory: Lebanon’s Disappeared and Post-war Culture.” Middle East Report 217 (217): 42–45. doi:10.2307/1520176.

- Zhu, Y. 2015. “Cultural Effects of Authenticity: Contested Heritage Practices in China.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (6): 594–608. doi:10.1080/13527258.2014.991935.