ABSTRACT

Over the last century, cultural heritage in Nigeria has experienced advanced neglect and continual degradation. This debacle created a trend whereby heritage resources have been wholly or partially replaced by new structures. The few heritage remnants in the locale will disappear if schemes to ameliorate, conserve and adaptive reuse are lacking. This research seeks a paradigm shift that balances the debacle and creates a sustainable physical development and cultural identity. This study is an empirical analysis of Old Oyo town in Nigeria and how it might be transformed into a living heritage rather than a deteriorating locale. This paper utilises the case study approach by presenting examples of the regeneration of the historic city in Fez, Morocco and the Kano ancient area in Nigeria. The findings show culture-led urban regeneration as a viable strategy for place making and sustainable development. It has the potential to drive the needed heritage development in Old Oyo while contributing to its environmental, economic and social sustainability. In addition, the project’s archeo-tourism potential is essential for socio-cultural sustainability and the revival of indigenous urban solutions and practices. Recommendations for the Old Oyo are crucial to developing the other heritage sites in Nigeria.

Introduction

The importance of historic places as an indicator of urban transformations cannot be over-emphasised. Urban heritage delineates the living continuity and development of cities across different civilisations. While architecture has always been crucial for shelter, its pertinent cycle ensures that it rapidly decays and deteriorates as it ages. As a result, their knowledge and construction practices may become extinct. Historic cities, on the other hand, promote cultural values and hold collective memories; when they disappear, a fundamental element of cultural identity is lost (Khan Citation2015).

Lynch (Citation1960) defines identity as the character of an object that distinguishes it from other things, making it unique. While the built environment plays an essential role in the narrative of culture and identity, it also tells a story about the place, collective attitudes and the common patterns of life (Boussaa Citation2016, Citation2018). However, the modern globalised trends of high towers of concrete and steel buildings create seemingly ubiquitous urban physiognomy between cities. It is hard to determine what the cities stand for in the long run with such uniformity in style, building materials and techniques, which generate discussions about the rapid changes and cultural amnesia that perverse the world (Boussaa Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015). A common practice is the neglect of heritage buildings to justify the impending demolition. While neglecting heritage places remains an anathema, a more repugnant act is obliterating people’s memories and references to the past (Rodwell Citation2008; Siamak and Michael Hall Citation2020; Boussaa Citation2021). The scarcity of resilient historic cities is a debacle that evolves from the contemporary propensity towards aesthetics rather than a sustainable environment.

Despite their potential for sustainable development, cultural heritage resources are one of the most susceptible sectors of development. They are the first section of a city to give way to grandiose planning reforms in most countries worldwide. Furthermore, the series of World Wars, conflicts, and conquests around the globe have had massive ramifications on historic towns, thus stifling cultural heritage tourism growth. Some cities or areas were severely damaged, and as a result, they were abandoned and never regained their former splendour. As of 12 November 2022, the UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger contains 52 properties of cultural, natural, mixed and transboundary sites. The endangered heritage sites are transnational in scope and contain monuments and city centres such as the historic centre in Vienna in Austria, with the more significant levels of deteriorating historic areas in Africa and Middle Eastern countries such as Mali, Niger, Egypt, Libya, Palestine, Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

Urban regeneration of old cities has recently been the topic of various studies across the core areas of architecture, urban planning, landscape and policy planning, due to its compatibility with more comprehensive sustainability of the built environment (Boussaa Citation2016, Citation2018). Various procedures have been inculcated in the regeneration of historic structures to reinvigorate, retain cultural relevance, and sustain more operational components of heritage (Orbaşli Citation2017). In historic areas, a human-centred strategy focusing on identity, sense of belonging, creative continuity, socio-economic development and evolving human aspirations is increasingly recognised as a solution to the complex urban dynamics. The interrelation between urban regeneration, conservation, sustainability and cultural heritage tourism development is a holistic approach that seeks to prolong the non-renewable resources in the built environment while enhancing place making and socioeconomic benefits.

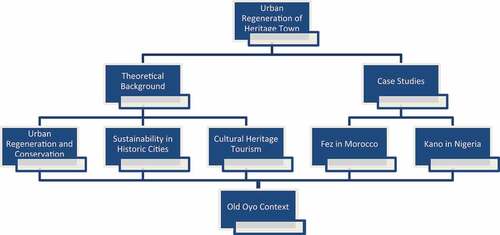

This paper adopts an empirical research method to discuss how urban regeneration of cultural heritage sites can innovate a holistic development pattern. This endeavour is part of the place making approach to conserve the deteriorating cultural heritage of ancient Oyo in Nigeria (). The research strategy intends to investigate case studies in Africa’s local and regional contexts. While the preponderance of cultural heritage sites in Africa presents a wide variety of urban heritage, the medina of Fez in Morocco and the ancient Kano metropolitan area in Nigeria form the case studies because of their comparable developmental conditions.

Urban regeneration; concept and meanings

Urban regeneration, also known as revitalisation, renewal, or renaissance in different nations, is a multidisciplinary topic that generally depicts the act or process of redesign, reconstruction, and often re-allocation of urban space to bring about a lasting improvement to the inner area of a city that is decaying (Roberts and Sykes Citation1999; Leary and McCarthy Citation2013). Although urban regeneration is imbued with complexities and might appear to be a fragmented profession at times, it gained prominence as a planning policy for physical and economic improvements of city cores and has many published treatises, especially in the United Kingdom (Lehmann Citation2019; Tallon Citation2020). Another aspect of urban regeneration is ‘maintaining a city’s competitiveness in an increasingly globalised post-industrial economy, while simultaneously trying to achieve more compact and sustainable urban forms’ (Couch, Sykes, and Cocks Citation2013, 33). Urban regeneration achieved global credibility as the solution to the upheaval, dislocation and complex urban problems primarily caused by rapid technological advancements, population growth, modernity and globalisation.

Urban regeneration and variant terms such as culture-led or conservation-led regeneration developed as an approach towards sustainable regeneration of historic areas (Orbaşli Citation2017). Despite policymakers’ initial concerns about combining regeneration and cultural components, it has become a catalyst for the city’s branding that drives regeneration while integrating with public participation and community involvement. Lehmann (Citation2019, 4) argues that urban regeneration, also called urban redevelopment or renewal, ‘includes smart infill housing, new infrastructure and the transformation of historic buildings for workplaces, education and tourism, culture-led regeneration and place making’. Due to their ties to memory and intrinsic meaning, it is nearly unanimous that people’s culture is crucial in rehabilitation projects. Urban regeneration entails adapting the ‘urban culture and heritage – maintaining a unique sense of place’ with the new developments within the existing urban morphology (). Cultural institutions play an important role in city revitalisation, typically combining civic functions and services with recreational opportunities. Therefore, urban regeneration is not just about building new things; it is also about conserving and reusing what already exists.

Figure 2. The strategies of urban regeneration (Lehmann Citation2019, 134).

This study adopts Strategy 1; urban culture and heritage as a crucial part of the built environment to create a unique community that critically supports the heritage resources and correlates with the local population. Many studies have advocated for the intrinsic values of cultural heritage as the link between the past, contemporary urban setting and anticipating the future. One of the fundamental goals of global initiatives is to safeguard the world’s cultural heritage through documentation, sustainable urban regeneration and conservation projects. Furthermore, critical regionalism has also emerged to mediate cultural identity and globalisation. Cultural heritage has created vibrant communities that bolster tourism while improving society, education, health, and economy (Boussaa Citation2012). In addition, urban culture and heritage are also responsible for creating a sense of place in successive communities within the built environment.

Historic centres constitute significant parts of a city with a compact, mixed-use land-use system and a tailored strategy that supports the socio-economic resources unique to each community. The close-knit and organic system of most historic cities allows local participation, social interaction and functionality while making the best adaptive reuse of the existing buildings. Most modern cities based on the models like Haussmann’s planning system are formulated with spatial segregation according to the different social chaste. This hollowed out the heritage core, which led to massive suburbanisation and sprawl.

Sustainable historic areas are human-oriented rather than automobile-dependent schemes in contemporary cities. Besides, work, entertainment, and housing are intrinsically linked to transportation to form a well-integrated city. Even with the technological advancements of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, some historic cities retain the cohesive narrow streets that support pedestrianisation rather than allow for the modern domineering automobile infrastructures. When vehicles are not permitted, they provide efficient public transport to reduce air pollution but still prioritise cycling. For example, the medina of Fez in Morocco and other European city centres in Copenhagen and Amsterdam mainly restrict cars, which eventually encourages people to walk and bike, thus promoting social interaction and vibrant street life.

Cultural heritage tourism

According to UNESCO World Heritage Centre (Citation2022, 1), ‘heritage is our legacy from all historical periods that we live with today and what we pass on to future generations. They are our touchstones, our points of reference, our identity’. Cultural heritage can be defined as the creative or symbolic resources passed down from generation to generation to each civilisation and thus to humanity. It gives each area its recognised qualities and is the storehouse of human experience as part of the assertion and enrichment of cultural identities. While heritage is based on patrimony and inherited resources, it does not necessarily entail just the past but also a representation or a reinterpretation of the past. Tangible and intangible resources are not intrinsically heritage but can become one through cultural values from their history, aesthetics or age.

Tourism is a tool for urban regeneration, almost as a last resort, as part of a desperate plan to assist the revival of the local economy when other options appear to be limited (Jimura Citation2021). Modern inclinations towards ‘green’ and ecotourism, sports tourism, health tourism and wildlife are prevalent owing to the delicate treatment of people and places. Still, they lag behind cultural tourism needs and demands on the scale and complexity of the present day. Rather than the long-held concentration on monuments, there is now broad recognition and acceptance of daily cultural landscapes that portray the lives of regular people in the worldwide megatrend of heritage tourism. Most previously unknown locations have become increasingly popular because of foreign visitations. Several other types of heritage tourism include the persistent diaspora travel to ancestral homes; a common practice in many cultures worldwide.

The United Nations World Tourism Organization defines cultural heritage tourism as ‘a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination’ (Richards Citation2018, 2). It encompasses all components that reflect ‘overarching and defined ways of life and lifestyle of a population, both past and present, with implicit carry-forward into the future’ (UNWTO Citation2018, 44). Many studies have emphasised critical aspects of cultural heritage tourism such as art and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries, living culture, lifestyles, value systems, beliefs, and customs. Cultural exchange occurs through engagement with these features, encouraging dialogue, understanding, and, as a result, tolerance and peace. While cultural heritage tourism is generally unplanned and poorly regulated, especially in less developing countries, it is responsible for the more significant percentage of heritage conservation worldwide. In addition, many other benefits of encouraging the regeneration, responsible use and adaptation of ‘living heritage for tourism purposes can generate employment, alleviate poverty, curb rural flight migration, and nurture a sense of pride among communities’ (UNWTO Citation2012, 2).

While physical resources are the foundation of cultural heritage tourism, it is essential to emphasise that people value urban vestiges’ originality, rarity, authenticity and precocity. Authenticity is pertinent in conservation, regeneration and cultural heritage tourism and is often a crucial criterion in World Heritage designation. Modern authenticity judgements can be based on artistic, historic, social, and scientific aspects of cultural heritage, such as ‘form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, and spirit and feeling, as well as other internal and external factors’ (ICOMOS, Nara Citation1994, 47). One thing to keep in mind is that numerous historic sites have been rejected as lacking authenticity because of their treatment. Regenerating a historic site entails maintaining an intricate flow and connections with what previously existed. As a result, a crucial strategy for urban regeneration projects involves an investigation of heritage resources to maintain synergy with the present and future developments.

Cultural heritage tourism in Fez, Morocco

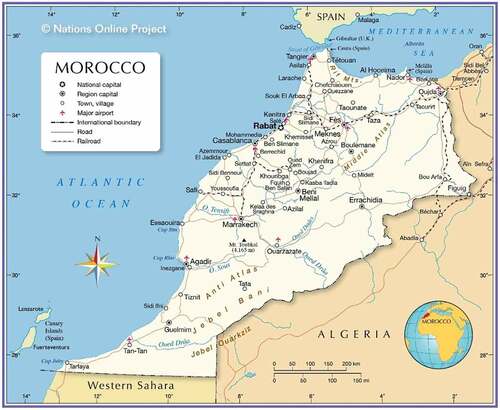

Fez is one of the medieval metropolises located about 200 km from the capital city of Morocco, Rabat. It holds an outstanding universal value as a rare example of a city that remained majorly unchanged from its inception to the present day. Fez was founded by the Idrissid dynasty between 789 and 808 A.D. as one of the oldest out of the 31 documented medinas in Morocco (Abdullah Citation2015). It is often considered as Morocco’s historical and cultural capital (El Harrouni Citation2017). The ancient city is split by the Fez wadi, separating the earlier migrants from Andalous in Spain and the Qairaouanis from Qairawan in Tunisia (El-Ghazaly Citation2008). Fez el-Bali (the old medina) and Fez el-Jadid (the new medina, founded in 1276) are fortified areas (). The bigger of the two, Fez el-Bali, is one of the most extensive and best-preserved Islamic cities in the Muslim world and is frequently cited by experts across the globe (Bianca and Holod Citation1980; Kahera Citation2011). Fez is significant as one of North Africa’s trade centres, where Europe and the Mediterranean intersect. In addition, the Qarawiyyin mosque, the oldest university globally, engrave Fez as a cradle for spiritual and scientific learning.

Figure 3. The map of Morocco showing the location of Fez (https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/morocco-political-map.htm).

To many tourists, Fez represents the acme of Moroccan urban sophistication. The metropolitan region is a showcase board for all the legacies of the past period, tradition, and human experience in Morocco, due to its culture, physical environment and urban fabric. For its resilience to withstand dynasty changes while maintaining its urban morphology unscathed, it became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981. It is home to a population of around 180,000 people and covers an area of 375 hectares with 31,385 dwelling units (Serageldin Citation2001). It encompasses 13,385 parcels of land, which contain 3000 historic buildings (Radoine Citation2003).

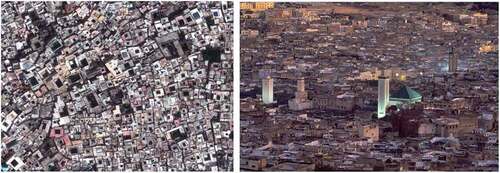

With its compact form, organic morphology, spatial configuration, blank facades, and labyrinthine narrow streets and alleyways, Fez’s urban design is indicative of the sustainable framework in the most ancient Arab cities. This system evolved from the principle of privacy and social cohesion embedded in the region’s practices and way of life. Fez is one of the world’s largest pedestrian cities. Each neighbourhood is a microcosm of an autonomous community centred on a mosque, palace and souq, with additional communal services such as public baths (hammams), bakery, madrasa and public fountains ().

Figure 4. The layout and aerial view of Fez (https://www.visitmorocco.com/en/travel/fez).

The approach towards urban regeneration

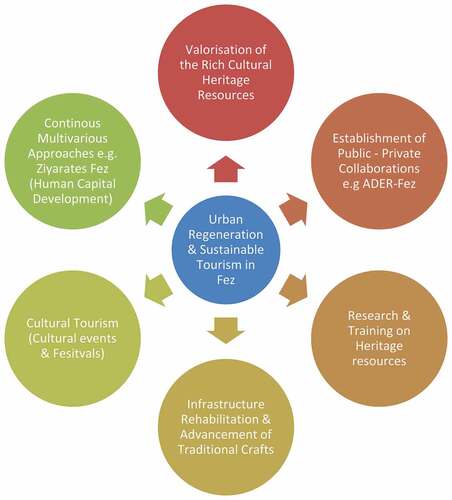

For up to three decades, the regeneration program considers research, data gathering, and documentation as integral (Radoine Citation2003; Serageldin Citation2001). Such a strategy prioritises place making and quality of life by addressing fundamental problems, including population density reduction programs, infrastructure repair, pollution transfer, and the creation of emergency street networks (). In 1989, an institutional intervention began with a commitment from the government and semi-private organisations ADER-Fez (the Agency for the Dedensification and Rehabilitation of Fez Medina) to engage in place making to address decades of neglect and bring amenities up to current standards. In addition, the Unit for Housing and Urbanisation at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design worked with various bodies to create the regeneration approach and analysis. It ensures the sustainability of the regenerating process by providing a training environment for the public towards continuity, innovation and adaptation of the local techniques that are indigenously Moroccan. Such a commendable strategy created the refinement of the medieval city and became an emblem of Moorish architecture.

The holistic problem-solving strategy lays out a systematic process for identifying all urban variables, infrastructure, and environmental characteristics from the city’s macro-level to the inner courtyard micro-scale. Furthermore, legislative support facilitates residents’ novelties and initiatives rather than hinders them. Moreover, the approach created a complete geographic information system (GIS) database of all physical resources in Fez, including buildings, infrastructure, sewage, springs, rivers and electrical networks. As a geospatial and cartographic resource, it is critical to coordinate the various urban management actors to make practical decisions and share information in real time.

The conservation program also pioneered new multidisciplinary approaches that analysed the hazardous chemicals that harmed the medina of Fez, such as chromium from industrial operations like leather tanning and brass manufacturing. They were relocated to Ain Nokbi’s newly planned industrial neighbourhood (El-Ghazaly Citation2008; Radoine Citation2008). In addition, other initiatives such as the ‘restoration and rehabilitation laboratory’, ‘socio-economic and urban observatory’, ‘survey and spatial analysis group’ and ‘environmental analysis group’ collaborated with the overall goal of improving the city’s fabric management, conserve its heritage and plan for future growth. A series of experimentation and intervention provided further lessons for the restoration and upgrading activities.

The impacts of cultural heritage tourism in Fez

Cultural heritage tourism contributes the highest quota, around 80% of tourism activities in Morocco compared to other tourism sectors (Siamak and Michael Hall Citation2020). Fez is one of the top ‘Moroccan Imperial Cities tours’, a vital element of cultural heritage tourism that entails exploring historic sites. Foreign visitors from France, Spain, and other European countries account for the highest annual visits, which engrave Fez’s reputation as one of Africa’s most desired tourist destinations. Increased tourist visits have concomitantly augmented the patronage of traditional crafts and souvenirs. In addition to the various tourism jobs, the rehabilitation processes generated new jobs to help the low-income social classes achieve financial independence. The estimations indicate that more than 10,000 jobs have been created through the involvement of the inhabitants in building works (Serageldin Citation2001).

Culture-led regeneration in Fez evolves a symbiotic relationship with cultural heritage tourism. While sustainable tourism invigorates financial, social and cultural efficiencies, the scheme is generally synergetic and successfully becomes a trajectory development. In essence, cultural hybridisation in urban regeneration is necessary to create a strategy that stimulates the local inhabitants. On the one hand, it ensures the continuity of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of great value to create a heterotopia. On the other hand, urban regeneration has increased international tourism in the last few decades because of improved urban amenities and cultural conditions (Abdullah Citation2015; El-Ghazaly Citation2008).

It is also essential to note that the tourism prospect of the cultural resources is somewhat responsible for the keen interest in rehabilitation endeavours in the Medina of Fez. Tourism in Fez has emerged as a critical driver of macroeconomic growth with increased sociocultural activities and public investment, such as the road networks and the airport. Cultural heritage tourism in Fez developed through international private participation, especially the Westerners. They constitute one of the highest investors in rehabilitating old houses to attract tourists. Fez is not only a place for a destination resort, but it is now gradually becoming the permanent property of foreigners as well. Their principal strategy is to purchase dilapidated buildings and rehabilitate them to create exotic riad hotels and guesthouses with the Arabian ‘one thousand and one nights’ themes (). Undoubtedly, such practices create physical development; however, the potential to create gentrification and other avoidable social segregation remains the downside of the ‘commodification’ approach to tourism.

Figure 6. Rehabilitation and adaptive reuse of an old house into a riad boutique hotel in Fez. (https://www.jacadatravel.com/africa/morocco/fes/accommodation/riad-fes/).

Cultural heritage tourism development has evolved 112 riad hotels between 1997 and 2016 (Alami, El Khazzan, and Souab Citation2017), or more than 150 boutique hotels located within the medina designated as a UNESCO historic site (Sutton Citation2012). In addition, local inhabitants are actively invested in the rehabilitation processes to create tourist lodges and boutique hotels. They contribute immensely to the economic prosperity of the Medina of Fez and the ongoing balance in the social strata. It is evident that the implementation of the rehabilitation plan is pertinent to revitalising the medina of Fez since it enhances the economy, restores cultural assets and improves the physical environment (Istasse Citation2019).

Another aspect of the Fez urban regeneration process concerns the commitment to increase the influx of tourism-related foreign capital. Several scholars classified the heightened interest in ‘Riad Fever’ (or riad property boom) towards creating a perfect Moroccan paradise for foreigners as an antithesis to the tremendous impact of cultural heritage tourism on the local people (El-Ghazaly Citation2008; Sutton Citation2012; Abdullah Citation2015; Steenbruggen, Kazakopoulos, and Nizami Citation2019). While cultural heritage tourism provides various benefits to the development of Fez, the lack of equilibrium creates marginalisation and socio-spatial transformation of some areas leading to a population decrease when low-income artisans had to sell their houses and take up residence elsewhere. The process is responsible for more than 25% population decrease in Fez, with 24,344 inhabitants leaving between 2004 and 2014 (Alami, El Khazzan, and Souab Citation2017).

A positive aspect of the regeneration policy is the continuous efforts to solve negative drawbacks within the historic area. Ziyarates Fez, a project officially launched in 2008, supports local tourism development through the adaptive reuse of 30 locals’ homes to accommodate tourists with the significant benefit of sharing common space, intangible culture, religion, experience, tradition, and culinary knowledge with the local inhabitants (Istasse Citation2019). This ‘bed and breakfast’ concept integrates tourism and human development as an inexpensive, social alternative to the pervasive boutique hotels, which curb the selling of houses, loss of the original inhabitants and balance of social classes within the community. While it promotes financial stability for the residents, it also generates the platform for continuously regenerating the old city infrastructure.

Unlike most modern cities in Africa, the desire for vernacular continuity still burgeons within the people who have always been the backbone of the Fez societal system and are responsible for the cultural and environmental developments over time. Even with globalisation worldwide, the example in Fez demonstrates that a decaying historic area’s intrinsic value can be renewed and rejuvenated by balancing the various rudiments of the built environment. The framework of cultural heritage tourism in Fez shows the importance of research and planning in creating a holistic approach to urban regeneration.

Largely, public participation and social integration contribute to a successful regeneration activity to complement the integral involvement of governmental bodies and other professionals. In terms of building supplies and technical support, financial assistance amounted to 30% of the work cost, while the occupants contributed around 70% of the cost of the works (El Harrouni Citation2017). It shows the level of social responsibility in the collective endeavour to rescue what remains from old Fez. However, an intervention must be concise and coordinated between the different bodies to avoid stifling tourism development.

The case of ancient Kano city in Nigeria

Nigeria, the largest economy in Africa, is also its most populous, with more than 200 million persons (Citation2021). It is located in the Sub-Saharan region on 923,769 square kilometres and has famous metropolitan areas like Lagos and Abuja (). It is home to many indigenous pre-colonial states and various cultures. The country claims more than 250 ethnic groups and 514 living languages. In addition, Nigeria has 101 important tourist destinations, which can be broadly classified as cultural/historical tourism, parks/ecotourism and landform/adventure tourism. Similarly, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments declared 65 heritage resources and has recently proposed an additional 100 heritage assets of significant importance to the culture and history of Nigeria.

Figure 7. Map of Nigeria showing Kano and old Oyo (https://www.google.com.ng/Nigeria).

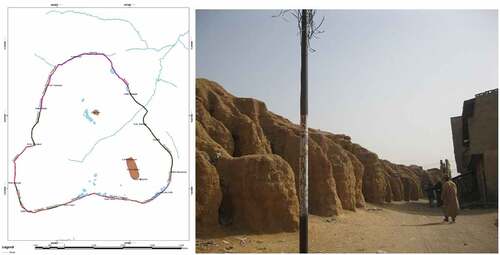

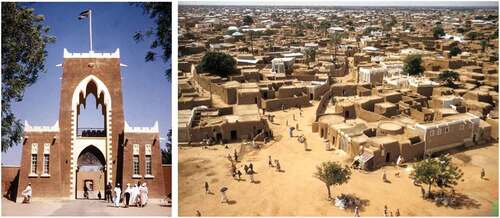

The Kano historic area and associated sites are significant cultural assets in the northwestern part of Nigeria. It serves as an emblematic mud heritage for the Hausa people, defining traditional building materials, techniques, themes and artisanship. Before the colonial era, the city formed an important crossroads for trans-Saharan trade. The heritage area holds spiritual, historical and cultural reverence for many Kano residents and is a notable tourist attraction. The urban area delineates the humble historical beginnings and continuity of the generations who have occupied and nurtured the legacy. Like most ancient civilisations’ practices, the wall enclosure serves as a defensive barrier to protect the city from wars and encroachments. According to Barau (Citation2014), the massive city wall spans over twenty square kilometres. It has an eighteen-square-kilometre radius with a height of ten metres and a thickness of nine metres. While much of it is in ruins, it still contains key heritage attractions such as Dala Hills, Kurmi Market and the Emir’s Palace. Unlike the ancient Palace area of Old Oyo, the Kano landmark area continues to serve its sociocultural, administrative, recreational, educational, and religious functions. This is a commendable scheme because unrestricted growth and modernity have caused the abandonment of most heritage places ().

Figure 8. Kano city wall encircles the Emir Palace and other heritage sites (Saliu and Osiboye Citation2018, 3).

The heritage site was added to the UNESCO World Heritage tentative list after meeting specific criteria in 2007. Without a doubt, the urban environment elucidates the community’s dynamic cultural legacy. The evolution of the sites is directly associated with the historical significance of the many rulers, as well as their beliefs, ideals, and aspirations. The regeneration of the urban area by overlapping age groups indicates a strong sense of place, which coincides with place-making activities. The heritage area has been deteriorating for a long time because of neglect. Even though they are now vulnerable and undergoing irreversible change, all the urban stocks are shaped by the culture, social status and complex interactions between the inhabitants and their environment ().

Figure 9. The Gidan Rumfa Palace gate and adjoining buildings (https://www.archnet.org/sites/3778).

The approach towards urban regeneration

Urban regeneration in the historic area has been a piecemeal process over a long period. Generally, regeneration or conservation is a budding field in Nigeria that requires conceptualisation due to the absence of well-defined norms and methods. For a long time, the prevalent misconception about mud buildings has been that they have crude and poverty persona in most urban areas, which is why they are less desired than modern structures. Given that the urban agglomeration maintains its clay form, the continuity of the earthen vestiges elucidates the typological significance and ingenuity of the successive regeneration and conservation because of the material’s fragile attribute. Urban regeneration is achieved through a collaborative work by the local guild and master buildings. It is, in essence, a classic case of ‘architecture without architects’ and ‘conservation without conservators’. Similarly, it indicates that addressing each locale as a specific case with unique features, materials, beliefs and context presents a more feasible approach.

The continuity of urban identity in the near future is a big challenge. A paradigm shift from traditional to modern fabric is becoming increasingly popular. The current retrofitting processes neglect the indigenous identity because of contemporary aspirations. While the urban area of ancient Kano was regarded as an exceptional artisanship and ‘the most impressive monument in West Africa during 1903 (Darling Citation2010), the urban fabric now resembles kitsch due to the lack of texture, colour, material authenticity maintained for more than 100 to 250 years. For example, the renewal of the indigenous earthen Great Mosque of Kano in the 1960s instils a modern concrete type that was insensitive to the immediate environment, thus changing the practices of heritage buildings. Furthermore, the regeneration of the palace area preserved the heritage buildings in the 1930s but it is transfiguring into concrete now.

Furthermore, the lack of protection policies caused unmitigated development and encroachment into the social space and the destruction of various ponds and vegetation that existed in the past. In the 2006 census, Kano State’s population density was higher than the national average of 441 people per square kilometre (Barau Citation2014). While it may be a modern necessity to adapt to the contemporary context, many people believe that the reconstructions have been fanciful and non-historic, which created an ‘overall loss of integrity and was the main reason why the Kano city walls and associated structures were not listed as a priority site in the original tentative list’ (Darling Citation2010, 1).

The impacts of cultural heritage tourism in Kano

Ascribing importance to the location of Kano within the rich historical cluster in the North of Nigeria makes it a hub for disseminating cultural resources. On one end of the spectrum, the cultural role of the historic urban centre supports the administrative and residential functions embedded in the living heritage rather than as a ‘cosmetic’ cultural emblem. It outshines all the other parts of Nigeria with neglect of cultural resources. On the other end of the spectrum, the recent accretions have reduced their cultural potential. One of the significant causes is following a globalised approach to heritage management regardless of the adaptability to the local environmental context. At the peak of its cultural excellence, cultural heritage tourism in Kano could compete with other countries and complement the rich historical settings in the various parts of Nigeria.

Several recent attempts to brand tourism in Kano have yielded sparse regeneration of authentic cultural buildings and precincts. While the tangible resources perform less than other historic cities like Fez, the approach involves creating a typical display board for urban identity. For instance, Gidan Makama, a cultural exhibition site adjacent to the Palace, complements the tourism laxity with its distinctive identity and functions as an open museum and public artistic site. With its traditional configuration, decorations and motifs, Gidan Makama is known for its touristic attraction as an important cultural centre. Besides its urban image, it contains all of Kano’s artefacts and ethnographic collections. It is one of 53 National museums in Nigeria (https://museum.ng/museums/national-museums).

The urban regeneration process and cultural heritage tourism in Kano have a midrange performance because of the overall treatment of the cultural resources. It outshines Old Oyo, where the historic district is almost extinct, although it trails behind other African landmarks such as Fez’s medina. It is a commendable accomplishment that Kano historic area maintains scanty antiquities and fabrics after 500 years. In the same spirit, the notion of sustaining spatial attachment and function ensures that even after a structure deteriorates, it is rebuilt. However, the lack of research results in a haphazard approach to tackling the innate urban area. As a result, the cultural continuity of the historic fabric succumbs due to globalisation.

Even when vernacular techniques are less influential in today’s society, they are still used in some parts of Nigeria. As a result, it is a feasible feat to achieve in order to ensure its long-term viability. While cultural heritage tourism is the primary factor responsible for the piecemeal regeneration in Kano, it has also benefited immensely from the built environment, which provides a conducive milieu for development. It became apparent that when public participation is not ensured in cultural heritage regeneration within the built environment, the interest in the symbolic fabric wanes amongst the inhabitants. Private-public participation should coexist to develop cultural heritage tourism and its management.

The case of old Oyo heritage site

Old Oyo heritage site is one of the most important but now deteriorating historic locations in the southwestern region of Nigeria. Within Nigeria, Oyo Ile, or Katunga as it was known in antiquity, encompasses a vast region in Oyo State, Nigeria, including towns such as Saki, Igbeti, Sepeteri, and Iseyin. It is located in the northern periphery of the modern Oyo town and Ibadan, about 414 kilometres from Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, and 190 kilometres from Lagos, the country’s commercial capital, with a total area of about 2,450 kilometres (Falade Citation1990; Folorunso et al. Citation2006).

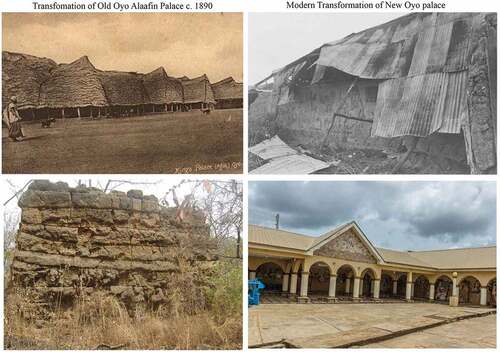

With a history that antedates the country, it was one of the earliest, most extensive, and culturally most advanced in the coastal region of West Africa. While the historical origin of Oyo is essentially contested amongst scholars because of the lack of a dating system, it is believed through oral tradition that Oyo-Ile was created by Oranmiyan, the youngest son of Oduduwa between the eighth and twelfth centuries A.D. (Olukole Citation2013). Interestingly, through carbon dating, archaeological findings establish a thriving society within the locale between 765 A.D. to around 1140 A.D. (Folorunso et al. Citation2006). From the twelfth century until its extinction in 1837, the site thrived as the political centre and capital city of the Old Oyo Empire. The incursion of war from the neighbour in Ilorin ensured the area remained uninhabited. The settlement relocated 130 kilometres southward to Oyo’s modern town, where the new capital city was created as a facsimile of the old. Archaeologists suggest an estimated population between 60,000 and 140,000 through pottery density during the eighteenth century (Olukole Citation2013).

In general, neglect of heritage resources in the Oyo area has left only a small number of cultural remnants that will most likely vanish if no urgent rescue activities are taken. In 1991, the ancient Oyo and its defunct Palace were given a new functional status as a National Park and game reserve after more than a century of neglect. It aimed to turn the new Park into a natural site by preserving flora and fauna. Out of all the eight recognised National Parks in Nigeria, Old Oyo National Park (OONP) is the fourth largest in Nigeria and encompasses the Old Oyo historic and archaeological site. Many of the cultural resources are distorted into ecological landscapes because nature has taken over a large portion of the site. For instance, most of the national parks listed by the Nigerian government are indeed classified as cultural heritage destinations.

The Park serves primarily as a protected tourist destination for wildlife and is organised into five ranges. The adjacent towns serve as the administration and management stations for the vast land area within the buffer zones. Old Oyo is managed from a neighbouring station in Igbeti, one of the bordering northern communities where the predominant populations are low-income farmers and artisans. While the surrounding towns depend on the Park’s tourism influence for community development, the Park mainly supports ecological wildlife and recreational activities and serves as a prominent research ground for botany, zoology, and ethnobotany.

While the urban section of Old Oyo and its constituents are devoid of their intrinsic cultural and functional significance, it is of interest to archaeologists, anthropologists, and European explorers invested in studying its built environment and cultural context. Years of archaeological studies have uncovered a piece of the urban area’s spatial layout, including Palace remains, Akesan market, prince’s (Aremo) dwelling, defence walls, reservoirs, wells, rock shelters and mud houses. In particular, the palace area of Oyo Ile has received increased attention and continues to unravel discoveries about building techniques and materials (Aremu, Emeagwali, and Shizha Citation2016; Falade Citation1990).

Meanwhile, it appears that the tandem mistreatment of the heritage-built environment is multi-facet and not limited to the Old Oyo milieu. A similar fascination with modernity and the concomitant undervalues for heritage also caused the extermination of the New Oyo vestiges. When early urban records of the surrounding royals are compared, more than 30% of the urban layout was lost following decomposition in the early twentieth century. Similarly, new structures continue to replace heritage buildings with traditional mural designs and decorations (). Unfortunately, this ongoing process may sever the link between the past and the future.

Figure 10. A collage of the evolution of old and New Oyo (Bowen Citation1977; Citation2017).

However, tourism in OONP has low performance and is mainly patronised by local tourists from neighbouring communities and states who understand the site’s historical significance. Tourism is affected by the underdevelopment of the cultural heritage sector, which hinders the site’s acceptance rate to foreign tourists. The seasonal factors and poor maintenance of accommodational and recreation facilities have been one of the threats to tourism. The need to enhance cultural heritage in Nigeria, specifically in Old Oyo, is pertinent to tourism development. The misrepresentation of the site as a natural site has subjugated its cultural resources. On the other hand, treating it as an archaeological resource rather than a functional heritage has affected its integrity. While the protection of nature remains a good framework, an ideal module will be a context where the nuances are balanced, so that cultural resources do not play catch up but at least coexist on par.

Discussion and synthesis

The three explored case studies have shown how the regard for sociocultural values and the regeneration of historic resources could improve cultural heritage development. Rather than treatment as sacrosanct, archaeological sites and their utilitarian values have the potential to herald tourism development. Archaeo-tourism is a common form of cultural tourism with the goal of propagating the sense of place experienced by a past culture. Many regions are gaining socio-economic benefits by cultivating interest in archaeology and conserving remnant resources. For example, the Jorvik Viking Centre in York, U.K, is a reconstructed replica site that depicts the old life of the Vikings after more than 1000 years and has been responsible for more than 17 million tourists since 1984 (Symonds Citation2020). With an average of 400,000 visits every year, such development has reinforced the culture’s identity beyond the scope of its period.

Central to the entire discussion of tourism development is the prospect of culture to attract high spending visitors and foreign investment. Undoubtedly, cultural heritage tourism has economic and social benefits. From the case of cultural heritage tourism in Fez and other African cities, tourism supports local business activities such as selling indigenous arts and crafts. In addition, cultural heritage tourism initiatives regenerated the urban heritage and provided financial incentives through organisations such as the World Bank and UNESCO to implement the regeneration framework.

Urban regeneration via cultural heritage tourism needs to support the already established way of life in crafts and art within the surrounding community. A bottom-up approach centred on human capital development enforces better use and public-private participation. Inhabitants around Old Oyo Park are oriented towards cultural creatives in cloth weaving, sculpture, blacksmithing, drum making, leatherwork, and iron smelting, crafts that have existed for a long time. Promoting culture-led regeneration will enhance their competitiveness and attractiveness, especially to the international community and create a domino effect on the standard of living. Sustainable development of cultural tourism will harness their creative enterprises and improve their socio-economic life. On the other hand, it will guarantee public participation, which is essential for developing tourism in a country like Nigeria.

Even with its current derelict status, Old Oyo has the potential to attract visitors through tourism because of its cultural significance. With global development trends, cultural heritage tourism in Old Oyo requires more experience-oriented outcomes. As a result, regenerating the historic area will develop the community and cultural resources into a living heritage. The examples of success stories of cultural heritage tourism worldwide come with the care, continuity and development of heritage resources. It remains a possible outcome that when the cultural aspect is stimulated, it will bring the enlistments as the first UNESCO mixed heritage Site in Nigeria.

In order to incentivise the government to allocate resources for cultural heritage tourism, cultural heritage initiatives need to follow actionable steps involving public and professional participation to provide the required data and awareness. The Federal Government currently manages all the cultural heritage assets through the Federal Ministry of Information and Culture and the National Commission for Museums and Monuments, which creates a cumbersome hierarchy because of the large size and different heritage context in the different zones of the country. One of the initial steps should be integrating heritage management into the local planning frameworks to map out heritage areas and create innovative human-centred proposals for regeneration. Part of this scheme may involve overseeing research development, updating heritage databases and creating GIS to manage heritage resources.

The governmental organisations should also create policies and legislate heritage management based on heritage significance such as archaeological, architectural, artistic, and historic interest in each state of the country. Such a strategy would provide the government with the data to understand the resources needed to develop the nation’s cultural heritage while enabling monitoring and transparency. Similarly, to the practices in the UK and most European countries, effective management of cultural heritage tourism would come from the local level based on their findings and input, which could be cascaded to the Federal system for resource allocation.

Another actionable step would require a long-term commitment from the Government and institutions to promote heritage education and reorientate the public on its significance. Several institutions worldwide offer courses and programs on heritage management, which develop their awareness and build capacity for better management of cultural resources. Nigerian universities and learning institutions should inculcate heritage conservation and tourism pedagogy in the curriculum for architectural and urban design students to prevent its treatment as specialised knowledge.

Conclusion and recommendations

In order to regenerate resilient historic cities in North Africa and Nigeria, a consolidative approach can adopt the bed and breakfast system in Fez, where the tourist can stay and integrate with the culture while the citizens gain employment and earn revenues. Another possible area for intervention is the provision of culture-related jobs like in museums. Better still; the approach can create new culture-led utilitarian residences and facilities for tourism.

In the long term, it is necessary to anchor tourism on cultural resources to regenerate heritage as a world site rather than a local game reserve. Studies have shown the importance of the cultural realm in the transformation of tourism. To achieve great strides in tourism, the government needs to invest in research to develop cultural tourism in Nigeria. The rich educational resources and research facilities in each state in Nigeria can be centralised to analyse the urban dynamics and the challenges facing the specific heritage areas. Investing in a study-based approach will ensure the authenticity and integrity of the regeneration processes since comprehensive documentation of heritage is unavailable. It is vital for the economic, social and environmental sustainability of the approach and cultural heritage tourism in the long term.

The tourism potential should promote sustainability by safeguarding the environment and historic resources while developing economic and social integration. Even with their archaeological and architectural value, historic urban areas that are inhabited are neither sacrosanct nor a museum that cannot be altered, but a delicate dynamic ensemble with social, residential and economic potentials. As such, the tabula raza approach must be avoided.

Cultural heritage resources catalyse developmental strategies, increase living standards, and improve health and safety. Tourism-driven urban regeneration is considered an appropriate system in any sociocultural milieu, so it does not vitiate the legacies. However, it must also ensure balance so that it does not stifle the ability to create as well. Infrastructure developments are essential to urban liveability, especially sustainable ones such as transportation, sewage, water, electricity, communication and urban educational facilities. UNESCO World Heritage recognition can bring the required international aid campaign to the progress and management of a city.

Capitalistic approaches are a downside to the sustainability goal of urban regeneration or sustainable tourism. On one side, profit-driven plans result in socio-spatial segregation and allow the marginalisation of the poor. Local inhabitants and artisans who are forced to leave may displace the original meaning and memories of heritage practices. Excessive tourism accentuation, on the other hand, may lead to the commodification of legacies, skewing the authenticity and integrity of historic locations. Similarly, focusing on monuments to create nationalistic rhetoric can utilise more practical communal infrastructure resources. Housing and infrastructures directly affecting the inhabitants are more compelling and necessary than monument rejuvenation, which does not contribute to the general public’s standard of living. Thus, a human-centred approach is required in all societies.

When a scheme is termed as successful, it does not connote that it created a utopian environment; instead, it successfully improved a local community’s living conditions. Urban regeneration is a continuous process and not a one-time intervention. It has two sides, which can be beneficial or adverse if not appropriately managed. Gentrification is a critical aspect that must be alleviated through incessant stringent policy checks. As is typical of practically all urban regeneration projects, when the standard of living grows, so does the neighbourhood’s real estate value. It might contribute to the impoverishment of the population, forcing residents to suburbanisation.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Muhammed Madandola

Muhammed Madandola is a PhD candidate at the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning at Qatar University. He holds a Master in Islamic Architecture, with Honors from Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Qatar. As a research, he has undertaken research on the subject of Urban Conservation and Sustainability, Islamic Art and Architecture, African Architecture and Urbanism.

Djamel Boussaa

Djamel Boussaa graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Algiers (EPAU) in 1984. He obtained his Master of Philosophy in Architecture from the University of York, UK in September 1987. He taught as an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Architecture, University of Blida, in Algeria for 8 years. He joined UAE University in September 1996 and worked for ten years before moving to the University of Bahrain for three years. He completed his Ph.D. in Urban Conservation from University of Liverpool, UK in 2008. From September 2009, he is an Assistant Professor at Qatar University, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning. He has been promoted to the rank of Associate Professor in March 2019. In addition to teaching, he was the Coordinator of the Graduate Studies since September 2016 until November 2018. During the last 30 years, he published extensively in the areas of Urban Conservation in North Africa and the Gulf Region. He published over 40 conference papers, one book, two book chapters and about 20 journal papers. In addition to teaching and research, he is now the Graduate Studies Coordinator since May 2021.

References

- Abdullah, A. 2015. ”The Fez Medina Heritage, Tourism, and Resilience.” In International Conference Proceedings: Heritage Tourism & Hospitality, CLUE+ Research Institute/Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 1–10.

- Alami, Y. H., B. El Khazzan, and M. Souab. 2017. “Heritage and Cultural Tourism in Fes (Morocco).” International Journal of Scientific Management and Tourism 3 (2): 441–457.

- Aremu, D. A. 2016. “Enclosures of the Old Oyo Empire, Nigeria.” In African Indigenous Knowledge and the Sciences: Journeys into the Past and Present, edited by G. Emeagwali and E. Shizha, 145–151. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

- Asiri. 2017. “Old Oyo.” ASIRI Magazine 2017. http://asirimagazine.com/en/old+oyo/.

- Barau, A. S. 2014. “The Kano Emir’s Palace.” KANO 91.

- Bianca, S. 1980. “‘Fez: Toward the Rehabilitation of a Great City’.” In Conservation as Cultural Survival, edited by R. Holod, https://archnet.org/publications/2617

- Boussaa, D. 2012. “The Casbah of Algiers, in Algeria; from an Urban Slum to a Sustainable Living Heritage.“ American Transactions on Engineering & Applied Sciences 1 (3): 335–350.

- Boussaa, D. 2014a. “Cultural Heritage in the Gulf: Blight or Blessing? A Discussion of Evidence from Dubai, Jeddah and Doha.” Middle East-Topics & Arguments 3: 55–70.

- Boussaa, D. 2014b. “Rehabilitation as a Catalyst of Sustaining a Living Heritage: The Case of Souk Waqif in Doha, Qatar.” Art and Design Review 2 (03): 62. doi:10.4236/adr.2014.23008.

- Boussaa, D. 2015. “Souk Waqif, a Case of Urban Regeneration and Sustainability in Doha’s Vanishing Urban Heritage, Qatar.” Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal 8: 389–400.

- Boussaa, D. 2016. “Cities in the Gulf: Rapid Urban Development and the Search for Identity in a Global World.“ In Population Growth and Rapid Urbanization in the Developing World, edited byBenna, U. G., Garba, S. B., 166–191. Pennsylvania: IGI Global.

- Boussaa, D. 2018. “Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities.” Sustainability 10 (1): 48. doi:10.3390/su10010048.

- Boussaa, D. 2021. “The Past as a Catalyst for Cultural Sustainability in Historic Cities; the Case of Doha, Qatar.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (5): 470–486. doi:10.1080/13527258.2020.1806098.

- Bowen, A. B. 1977. Murals at Afin Oyo. African Arts 10 (3): 42–45.

- Couch, C., O. Sykes, and M. Cocks. 2013. “The Changing Context of Urban Regeneration in North West Europe.“ In The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration, edited byLeary, M. E., McCarthy, J., 53–64. London: Routledge.

- Darling, P. 2010. ”’Ancient Kano City Walls and Associated Sites - World Heritage Site - Pictures, Info and Travel Reports’.” 16 October 2010. https://www.worldheritagesite.org/tentative/id/5171.

- El-Ghazaly, S. S. 2008. “Reclaiming Culture: The Heritage Preservation Movement in Fez, Morocco.“ Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. University of Tennessee - Knoxville. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1176.

- Falade, J. B. 1990. “Yoruba Palace Gardens.” Garden History 18 (1): 47–56. doi:10.2307/1586979.

- Folorunso, C. A., P. A. Oyelaran, B. J. Tubosun, and P. G. Ajekigbe. 2006. “Revisiting Old Oyo: Report on an Interdisciplinary Field Study.” In Society of Africanist Archaeologists 18th Biennial Conference Proceedings 2006, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

- Harrouni, E. K. 2017. “‘Sustainable Urban Conservation and Management of Historical Areas. Come Back to Thirty Five Years (1981–2016) of Observation in Fez Medina, Morocco’.“ In International Sustainable Buildings Symposium, edited by Firat, S., Kinuthia, J., Abu-Tair, A., 542–553. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- ICOMOS, Nara. 1994. “The Nara Document on Authenticity”. Proceedings of the ICOMOS. Nara, Japan, 1–6.

- Istasse, M. 2019. Living in a World Heritage Site. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Jimura, T. 2021. Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Japan. London: Routledge.

- Kahera, A. I. 2011. Reading the Islamic City: Discursive Practices and Legal Judgment. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Khan, H.U. 2015. “Architectural Conservation as a Tool for Cultural Continuity: A Focus on the Built Environment of Islam.” ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 9 (1): 1. doi:10.26687/archnet-ijar.v9i1.682.

- Leary, M. E., and J. McCarthy. 2013. The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration. London: Routledge.

- Lehmann, S. 2019. Urban Regeneration: A Manifesto for Transforming UK Cities in the Age of Climate Change. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Olukole, T. O. 2013. “‘A Geographic Information Systems Documentation of Oyo-Ile and Badagry Heritage Sites, Southwestern Nigeria’.” PhD Thesis.

- Orbaşli, A. 2017. “Conservation Theory in the Twenty-First Century: Slow Evolution or a Paradigm Shift?” Journal of Architectural Conservation 23 (3): 157–170. doi:10.1080/13556207.2017.1368187.

- Radoine, H. 2003. “Conservation-Based Cultural, Environmental, and Economic Development: The Case of the Walled City of Fez.“ In The Human Sustainable City, edited byForte, B., Girard, L. F., Cerreta, M., De Toro, P., 457–477. London: Routledge.

- Radoine, H. 2008. “Urban Conservation of Fez-Medina: A Post-Impact Appraisal.” Global Urban Development Magazine 4 (1): 1–12.

- Richards, G. 2018. “Cultural Tourism: A Review of Recent Research and Trends.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 36: 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005.

- Roberts, P., and H. Sykes. 1999. Urban Regeneration: A Handbook. London: Sage.

- Rodwell, D. 2008. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Saliu, M. A., and O. O. Osiboye. 2018. “Ancient Kano City Wall: Tourism and Economic Resource.”

- Serageldin, M. 2001. “‘Preserving a Historic City: Economic and Social Transformations of Fez’.“ In Historic Cities and Sacred Sites. Cultural Roots for Urban Futures, edited bySerageldin, I., Shluger, E., Martin-Brown, J., 237. Washington: The World Bank.

- Siamak, S., and C. Michael Hall. 2020. Cultural and Heritage Tourism in the Middle East and North Africa: Complexities, Management and Practices. London: Routledge.

- Steenbruggen, J., P. Kazakopoulos, and I. Nizami. 2019. “Urban Tourism and Cultural Heritage: The Ancient Multi-Layered Medina’s in Morocco.” Research Memorandum 2019 (1).

- Sutton, S. S. 2012. “‘Implications of“Neo-Orientalist” Conservation in Fez, Morocco: Need for an Innovative Non-Profit Alternative’.” PhD Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Symonds, J. 2020. “Jorvik Viking Centre.” Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology 6193–6194.

- Tallon, A. 2020. Urban Regeneration in the UK. London: Routledge.

- UNESCO. 2022. “‘World Heritage’.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2022. https://whc.unesco.org/en/about/.

- UNWTO. ed. 2012. Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 10.18111/9789284414796.

- UNWTO. 2018. Tourism and Culture Synergies. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). doi:10.18111/9789284418978.

- World Bank. 2021. “‘Overview’.” Text/HTML. World Bank. 2 June 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.