ABSTRACT

In recent years, increasing attention has been given to the role of social movements in the production of heritage. However, there has been scant theoretical reflection on the inverse process ―the influence of heritage on the production of civic activism. The objective of this article is to fill this void in the literature about heritage movements, by exploring the strategic benefits and hermeneutical limitations of heritage as a political mobilisation device. The case study addresses the evolution of the movement in defence of Casa del Pumarejo (Seville) over the past twenty years, analysing the perception of heritage during three distinct historical stages: non-heritage, heritagisation and hyper-heritage. This ethnographic longitudinal approach shows the movement’s incorporation of transformative cultural meanings and subversive (or, as the activists say, ‘rampant’) uses of heritage to achieve public recognition, as well as the ambivalences of focusing social struggles on heritage.

Introduction

Casa del Pumarejo was built in 1775 as a manor house for Pedro Pumarejo, an hidalgo who forever restructured Seville’s urban fabric, since he had seventy traditional neighbourhood homes demolished to construct it. After his death, the building was sold to the City Council and served various social functions ―hospice for abandoned children (1785–1807), women’s prison (1808–1814), and adult school and popular library (1861–1882)― until it was purchased by Aniceto Sáez (1883), who gave it residential and commercial uses. During the 20th century, until the last individual owner, Gonzalo González, who died in 1975, it housed a sports club and several theatrical, musical and literary associations.

Casa del Pumarejo has thus been a focal point of sociability in the San Gil neighbourhood, a former working-class urban space currently undergoing an accelerated gentrification process (Jover Báez and Díaz Parra Citation2020). The neighbourhood is known for its associative fabric and a long-standing fight for social transformation and the ‘production of locality’ in the face of the homogenising, atomising dynamics of neoliberalism (Appadurai Citation1995). In 1999, a movement emerged to prevent the conversion of the building into a luxury hotel and the ensuing eviction of the residents. The mobilisation, which has had significant popular support within the neighbourhood, was headed by the Asociación Casa del Pumarejo ([Casa del Pumarejo Association]; hereafter, ACP), an assembly-based entity made up of dozens of social groupsFootnote1 ().

Figure 1. Symbolic embrace of Casa del Pumarejo during the COVID-19 pandemic in front of the façade. 2020. ACP archive.

During these twenty years, the ACP has promoted numerous debates about the strategic actions, political demands and the most suitable concepts for articulating the mobilisation (Benford and Snow Citation2000). This particular mobilisation can be understood as the collective action of a plurality of individuals to raise awareness about, and attempt to solve, certain socio-political problems, namely the safeguarding of Casa del Pumarejo. The association was originally organised to fight eviction from the building, connecting the neighbours’ problems to phenomena such as real-estate speculation, urban gentrification and the defence of the right to housing. Subsequently, it decided to frame the conflict within the discourse of heritage and the safeguarding thereof. The activists started a struggle to obtain a heritage declaration for the building and, once obtained, used it as a legal device to confront (and negotiate with) the local political authorities. However, the ACP has not incorporated the Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD) in a passive or acritical manner (Smith Citation2006), but has instead produced its own vernacular counter-narrative by qualifying heritage as common, participatory and diverse, and coining the adjective rampant to describe the subversive use of heritage.

‘Rampant heritage’ is an emic term used by some activists in a humorous, self-parodic manner to describe those strategies intended to go beyond hegemonic heritage paradigms (conservationist, monumentalist, expert). It is a polysemic concept, arising from the fact that Casa del Pumarejo is popularly known as ‘el Puma’ (abbreviation of Pumarejo and a fierce animal), and refers both to showing one’s claws to attack (like pumas do) and to social advancement through heritage. The coining of this term highlights the ACP’s creative and theoretical skills, and its search for new orientations in heritage management, but also raises some questions regarding the transformative power of semantically resignifying heritage. The concept ‘Rampant heritage’ is an ethnographic finding that highlights the theorising capacity of activists and it serves to articulate the relationships between concepts and literature about subaltern heritages, such as working class, migrant, diasporic or indigenous heritages (Smith Citation2006; Morell Citation2011; Dellios and Henrich Citation2020).

The current central role of the concept of heritage in the ACP’s struggle is suggestive from a comparative, diachronic and longitudinal perspective. In fact, in the beginning, the neighbours showed no interest in heritage, as they considered it to be an abstract, expert, elitist concept, incapable of condensing their experience of the world. Likewise, the activists interpreted it, not as an instrument of political mobilisation, but a bourgeois, counter-revolutionary, alienating concept. How was it that the ACP decided to include heritage recognition among its political demands? Why were the initial demands unrelated to official heritage (such as the right to adequate housing or the fight against gentrification) subsequently articulated through a heritage activist rhetoric? Why did a struggle without heritage develop into a struggle with heritage and, finally, a struggle from a heritage considered to be alternative, anti-establishment and subaltern? This article will attempt to answer these questions through an assemblage of social movement theory and critical heritage studies (Jones, Mozaffari, and Jasper Citation2018).

For analytical purposes, the article divides the ACP’s history into three broad stages: non-heritage, heritagisation and hyper-heritage.Footnote2 Firstly, we explore the association’s political origins and the complex network of unlikely alliances that enabled the mobilisation. In this section, we present the groups that led the struggle and the factors that conditioned the initial framing of the protest in terms of the right to housing. Secondly, we describe the actions aimed at the heritage construction of Casa del Pumarejo and examine the discourse of the advocates (particularly an anthropology professor) and the (anarchist-leaning) detractors of the heritagisation process. In the third section, we analyse the ACP’s strategies for resignifying and resemanticising the notion of heritage and the political implications of its theorisation as rampant heritage. Finally, we discuss some of the contradictions arising from focusing the struggle on the defence of metacultural values and offer a critical assessment of the hermeneutical limits of heritage as a framework for political resistance.

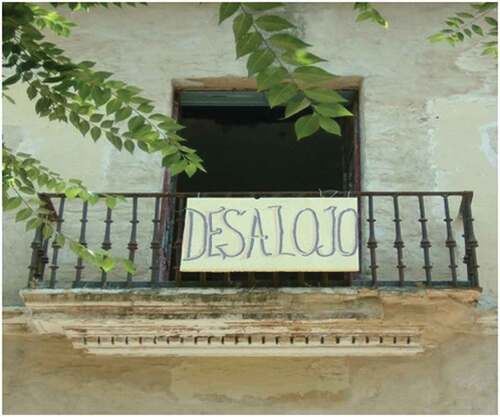

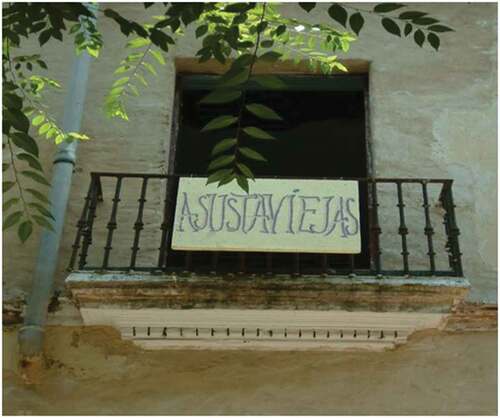

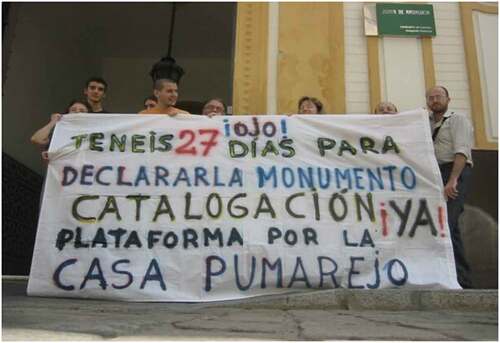

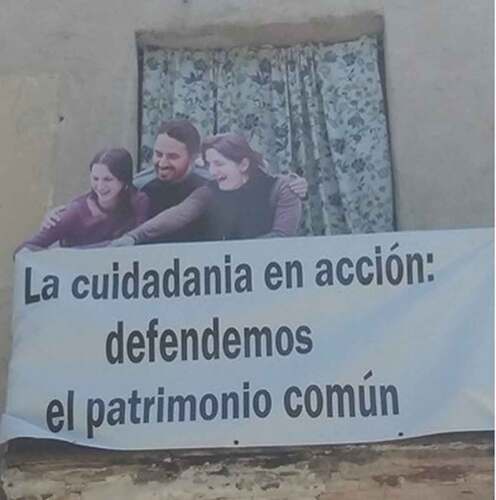

The article is illustrated with the banners hung from the Casa del Pumarejo’s balconies during each historical stage, which show the progressive transformation of the movement’s strategies. Our analytical and methodological approach is inspired by Framing Processes Theory (Benford and Snow Citation2000), which, in turn, is influenced by Erving Goffman’s notion of frame (Goffman Citation1974). This theoretical approach is appropriate for analysing the interpretation frames of social conflict, that is, the way in which social movement delimits the collective experience and produces a shared discourse on the causes of the struggle. An analysis of the banners’ messages reveals gradual changes in the perception of the neighbourhood’s problems, as well as the various narrative strategies used to morally legitimate the protest.

As stated in prior research on Casa del Pumarejo, codifying the mobilisation in terms of heritage was a deliberate discursive move adopted for pragmatic, strategic and instrumental purposes (Hernández-Ramírez Citation2003; García Jerez Citation2009). García Jerez’s doctoral dissertation (García Jerez Citation2009) analyses the uses of heritage in the symbolisation process of Casa del Pumarejo, whereas Hernández-Ramírez (Citation2003) focuses on the building’s historical functions. Both works aptly describe the vicissitudes of the heritage construction during the initial stages of the mobilisation; however, they disregard the long-term counter-productive consequences of heritagisation. Our article is intended to complement this literature, by presenting an ethnographic assessment of the Political Opportunity of Heritage (POPH) on Casa del Pumarejo (Santamarina and Mompó Citation2021), and emphasising that the discourse of heritage is not neutral, based on a rational assessment of political benefits, but that heritage construction entails affective, emotional and biopolitical transformations in the subjects (Bendix, Eggert, and Peselmann Citation2012).

Our approach is based on a comprehensive, holistic anthropological conception of heritage and inspired by the heterogeneous theoretical framework of Critical Heritage Studies (hereafter CHS) (Smith Citation2006; Hafstein Citation2012; Gentry and Smith Citation2019), which have rightly identified the asymmetries and inequalities in the field of heritage, asking uncomfortable questions about the influence of conservative ideologies (imperialism, nationalism, classism, patriarchy, etc.) on its definition. The main contribution of CHS has been to re-establish the importance of who, from where and for what purpose heritage is produced, thereby denouncing the exclusion of subalternised identities (oppressed genders, popular sectors, indigenous groups, etc.). The perspective of CHS is appropriate to reveal at a phenomenological level the relational webs of heritage constructions, the perception of heritage by subaltern and counter-hegemonic groups, and, last but not least, the voices of those activists who advocate the practical (and theoretical) feasibility of de-heritagising social movements.

The data presented are based on the research conducted for my doctoral dissertation (2016–2020), which combined qualitative fieldwork (four six-month stays in the field) and ongoing virtual dialogue with the activists through social media (WhatsApp group, email and Facebook). The methodological approach combines various research techniques: 23 semi-structured interviews (15 neighbours and activists, 4 former activists and 4 local civil servants), ethnographic observations recorded in a field journal (43 meetings, 9 assemblies and 7 guided tours) and a review of secondary sources (technical documents, heritage legislation, historical archives, etc.). The official documents analysed were the Heritage Declaration and various legal rules and regulations issued by the Seville City Council, while the ACP’s history was examined using documentary sources, historical photographs and the activists’ oral memories.

Heritage activism under analysis

The conceptual approach proposed is to understand heritage as a regime of truth in the Foucauldian sense, i.e. a system of ordered procedures for the production, circulation and operation of unquestioned and unquestionable assertions (Foucault Citation2000), but also as a regime of domination, intrinsically linked to the will to control the past and create prospects for the future (Alonso González, González-Álvarez, and Roura-Expósito Citation2018). The idea of heritage regimes has previously been used by Hafstein (Citation2012), Bendix, Eggert, and Peselmann (Citation2012) or Jiménez-Esquinas (Citation2017), primarily to describe the detrimental effects of certain heritagisation processes promoted from above, especially top-down initiatives of those stakeholders historically in charge of official heritage production. However, in the last two decades, the notion of participation has been integrated as imperative in the heritage regimes (Sánchez-Carretero et al. Citation2019), and, therefore, we use this theoretical framework to analyse popular and subaltern heritages activated by social movements from below (Robertson Citation2012).

In Spain, until the 1980s, the main promoters of heritage declarations were institutions like the State, technical experts and, significantly, the Catholic Church, whose actions cannot be separated from ideologies such as nationalism and its interest in generating a unifying discourse through monumentality, archaeology or museums (Alonso González Citation2018). Although, with the crisis of legitimacy of the nation-state and in the wake of international declarations (e.g. UNESCO in 2003), social movements became a leading actor in the activation of heritage, sharing mobilisation styles and repertoires with other activist movements such as environmentalist, feminists and indigenous rights advocate.

The increasing role of the citizenry in favour of heritage safeguarding has been documented on a global scale, with specific literature devoted to parts of Asia (Byrne Citation2014; Mozaffari and Jones Citation2019), Oceania (Hviding and Rio Citation2011), Africa (Schmidt and Pikirayi Citation2016), the English-speaking world (Harrison Citation2010; Smith and Campbell Citation2011), Latin American countries such as Mexico (García Canclini and IAPH Citation1999), Argentina (González Bracco Citation2014) and Chile (Conget Citation2014; Silva-Escobar Citation2021), and several regions within the Spanish State (Gómez Ferri Citation2004; Quintero Morón Citation2009; Santamarina Citation2014). Their research reveals the organisational diversity of heritage defence movements, which include classical conservationist organisations, with an oftentimes elitist and restricted concept of heritage, as well as associations and platforms that defend popular, alternative or unofficial heritage from counter-hegemonic positions (Hernández-Ramírez Citation2005).

Most studies on heritage activism start from the premise that minority groups in marginal positions have the ability to use heritage from below, as a non-violent counter-power mobilisation tactic (Robertson Citation2008; Conget Citation2014; Hammami and Uzer Citation2018). They thus assume that social movements have a certain degree of agency and that articulating heritage into their demands has positive effects in terms of citizen empowerment. This instrumentalist, functionalist view of heritage is based on three primary assumptions. First, the heritagisation framework codifies dissidence in constructive, socially acceptable terms, thereby favouring social recognition of the values and diversity of groups by public institutions. Second, heritagisation struggles strengthen subaltern positions because they renew and diversify confrontation repertoires and symbolically revalue previously marginalised memories, pasts and identities. Third, heritage activations promote identity reaffirmation dynamics that can be effective in reclaiming citizen rights and participation, and/or fighting speculative processes.

In this article, we will question these assumptions from an ethnographic standpoint in order to highlight four potential and possible counter-productive effects of the emphasis on heritage. First, the articulation around heritagisation does not necessarily reaffirm the social movements’ collective identity, since, in practice, heritage can add a new axis of conflict between heterogeneous groups of activists that do not always share the same strategic view of the struggle. The emphasis on identity can help heritage discourse to operate as a cohesive tool, but it may also introduce an epistemic gap that fractures the movements, leading groups with counter-heritage views to turn away. Second, appropriating the language of power by means of heritagisation does not necessarily multiply political opportunities, since, although it may facilitate institutional recognition processes, it also exposes the movements to devices of bureaucratic and administrative control. Third, the symbolic recognition of heritage does not mechanically contribute to resolving the material inequalities fought by the movements, since prioritising the discursive frame of heritage may end up replacing or relegating more combative grammars of struggle, which, in turn, may hinder achieving other citizen rights. Fourth, heritage construction is not necessarily a clever political confrontation scheme, as studies on the subject have increasingly warned about the dialectic, mutually reinforcing relations between heritagisation processes and neoliberal dynamics such as gentrification, commodification or touristification (Franquesa Citation2013; De Cesari and Herzfeld Citation2015; Beeksma and De Cesari Citation2019). For all these reasons, it seems more pertinent to address heritage as a paradoxical, ambivalent and contradictory notion, and to maintain a sceptical outlook on its effectiveness in channelling political antagonisms.

Not all persons, groups or movements can be producers of official forms of heritage; rather, the production of heritage requires a mobilisation of affects and a socialisation of knowledge. This is why we make it a point not to present heritage as empirical, physical-world evidence, but, instead, trace a genealogy of the conditions for its appearance in activist groups and its interconnections with other contestatory rhetorics against social inequality. Our purpose is to complement studies on heritage activism by unravelling the mediations of knowledge and power that grant political legitimacy to heritage. Of course, heritage is a form of resistance that may be harnessed to articulate protest in multiple scenarios: from questioning the neoliberal economic order to vindicating spatial justice (Hammami, Jewesbury, and Valli Citation2022). However, it is reasonable to ask in what ways heritagisation creates injustice and how heritage and resistance are intertwined with social conflict (Hammami and Uzer Citation2022). The answer involves problematising the relationships between heritage and social movements through an ethnographic approach to the disputes between activists in favour of and against heritagisation, as well as analysing the differential forms of internalisation and embodiment of heritage according to the social actors’ (neighbours, activists, researchers, etc.) positioning. It involves understanding the progressive incorporation of heritage defence discourse within social movements, as well as the effects that the thematisation in terms of heritage has on the figuration of political action, a topic that has received limited attention in the literature.

The emergence of the non-heritage struggle for Casa del Pumarejo

The activists involved in the Casa del Pumarejo movement trace its origins back to the autumn of 1999, when a hotel company purchased half of the building and started negotiations to acquire the rest. Since the luxury hotel’s tourist use was incompatible with the neighbours’ residential uses, the owners implemented schemes designed to expel the residents: they refused to rent the vacant dwellings, stopped collecting rent to elicit non-payment evictions and hindered maintenance works. When these tactics proved insufficient to vacate the premises, they resorted to real-estate mobbing. For example, in December 1999, hotel company lawyers warned the neighbours about an alleged building collapse risk, which was just intended to instil fear, since they did not submit any architectural reports to endorse their predictions.

For strictly analytical purposes, on the basis of their heritage and political subjectivity, we can classify the persons opposed to these pressures and the ensuing housing insecurity into three heterogeneous groups:

The residents of Casa del Pumarejo, elderly popular-class women who had no formal education and had always worked within the domestic sphere. After living there for decades with renta antigua [old rent] leases,Footnote3 they felt a strong emotional attachment to Casa del Pumarejo. Their sense of belonging was immanent, related to their biographical experience and community ties. They did not value the building for its architectural or historical features, but for its residential function ―as their home and the epicentre of their affective relations. Until then, they had little contact with the official field of heritage and associated the concept with high culture, grandiloquence, monumentality and the dominant classes (Choay Citation2007). They experienced their problems in an individual, atomised manner, avoided socialising the moral sentiments aroused by the eviction (fear, frustration, shame, etc.) and did not consider the possibility of a collective struggle to keep their homes. Their indignation was not initially related to a structural critique of speculative and/or gentrification practices, but to the owners’ degrading treatment, their disrespect for human dignity and their violation of ethical codes.

Middle-aged people from the neighbourhood with heterogeneous professional backgrounds (liberal professionals, university professors, artisans and shopkeepers) who shared admiration for Casa del Pumarejo and valued it as a palace emblematic of eighteenth century Sevillian civil architecture and a casa de vecindadFootnote4 representative of nineteenth century Andalusian working class dwellings. Having been socialised in the transcendental value of heritage, they treasured the building for its historical, monumental and ethnological elements, which they wished to preserve. This group was interested in the heritage declaration and determined to defend the residents’ rights through formal, normative mobilisation repertoires (public requests, calls for meetings, collection of signatures, etc.).

Finally, a more homogeneous group was made up of young activists (between 20 and 35 years of age) who were politically committed to environmentalism, anti-developmentalism and libertarian anarchism, exhibited counter-culture aesthetics (punks, squatters, hippies, etc.) and had been active in previous mobilisations against neoliberal urban projects in Seville: the 1992 Universal Exhibition, the Alameda parking lot and forced evictions from other buildings, such as Palacios Malaver (Barber, Fresnel, and Romero 2006). These activists were somewhat reluctant towards heritage, which they viewed as an institutional, academic, and elitist concept completely ineffective in articulating the antagonism between life and capital; instead, they were concerned about conflicts at the neighbourhood level, such as lack of access to affordable housing, increasing rents and real-estate speculation. Most of them were wary of representative politics, reformist solutions and monolithic ideological frameworks, although in practice their principles were close to anarchism: self-management, mutual aid, assembly-based organisation and the defence of vindication repertoires such as direct action or disruptive confrontation. However, despite their reluctance towards the concept of heritage, in their everyday practices they were committed to safeguarding the Casa del Pumarejo’s intangible legacy (social common goods, local memory, affects towards the building, etc.).Footnote5

During the spring of 2000, the shared concern over the Casa del Pumarejo’s future led to the first informal contacts between neighbours (especially a trade unionist family) and activists. These meetings gradually consolidated into what Lefebvre ([1974] Citation2013) calls an ‘unlikely alliance’ between a first reactor group, which sought to protect its own social space against the threat of eviction, and a second, liberal or radical, group, which opposed the project out of a sense of public commitment. Their convergence was based on the critique of the most noxious aspects of urban gentrification and an implicit consensus to prioritise the building’s residential uses over the real estate sector’s speculative interests.

In 2000, this group of neighbours and activists founded the Plataforma para la Defensa de la Casa del Pumarejo [Platform in Defence of Casa del Pumarejo], which in 2008 was legally formalised as the Asociación Casa del Pumarejo ([Casa del Pumarejo Association] ACP). The ACP set up alliances with neighbourhood cultural associations and Squatted Self-Managed Social Centres that were also resisting neoliberal urban planning policies. They initially demanded a comprehensive rehabilitation of the building and that the tenants be able to stay under dignified conditions, while their political actions focused on denouncing those responsible for the property’s decay: the greediness of private capital (the owners, who did not comply with their legal duty to preserve it) and the neglect by public institutions (the Seville City Council, which did not implement any measures to resolve the situation). These demands were legitimated by invoking constitutional citizen rights and thus inscribed the movement within the long history of housing struggles in Spain, which emerged in the 1970s and have continued up to the present thanks to organisations like the PAH (Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca [Platform of People Affected by Mortgages]) (García-Lamarca Citation2017).

During this initial period, the Casa del Pumarejo’s banners were characterised by a direct style and a transformative intention. The activists considered that the most effective way to get the citizenry involved was to point out the conflict’s empirical aspects. Hence the inventive, relatable and referential mobilisation rhetorics (for example, invoking the Virgin of the Hiniesta, a protector of the city of Seville), and the slogans highlighting the neighbours’ everyday problems (). The banners’ logic was clearly reactive, articulated through the denunciation of the damages incurred (eviction), the opponents (asustaviejas)Footnote6 and the underlying socioeconomic processes (speculation), while their purpose was to convey the neighbours’ feeling of indignation and transform it into a public interest issue.

The heritage construction of Casa del Pumarejo

In the middle of 2000, a few months after the beginning of the mobilisation, Javier Hernández, a social anthropology professor who lived in the neighbourhood and was ideologically close to the activists, contacted the ACP to express his interest in collaborating with the struggle from his area of activity and professional knowledge: heritage. The professor was concerned because the hotel company’s economic interests threatened to destroy the Casa del Pumarejo’s heritage elements (architectural features, historical uses, social values, etc.). In order to revert these dynamics of privatisation, he started attending the assemblies and initiated an awareness process, focusing on certain tangible and intangible features of Casa del Pumarejo, not so much to encourage an abstract appreciation of heritage (based on some sort of essence or mythical past) as to help the social movement to obtain moral, institutional and legal recognition (Personal communication from Javier Hernández, 05/17/2017).

During the first stage, Hernández shared his expert knowledge with the activists, to convince them of the aggregative and anti-establishment potential of heritage. However, this pedagogical process had an uneven impact and did not predispose the movement towards a favourable assessment of heritage. As Hernández explains in the following interview excerpt, negotiation of the action repertoires generated conflict, since there were opposing views on the convenience of using heritage as a rhetoric:

In the end we had several tense assemblies. Because some participants suggested that we chain ourselves and lock ourselves down, whereas others, even though we weren’t ideologically to their right, had a different viewpoint. The squatters said it was an injustice and direct action was needed … And some of us said that it was heritage! And, moreover, violated heritage! We said, ‘There’s a heritage law, let’s take advantage of it … Because what sells and what the administration has internalised is the discourse of heritage’. Luckily, in the end we managed to convince some of them, and others left. (Javier Hernández, 05/17/2017)Footnote7

Hernández posited the heritage claim as a scheme to reinforce the ACP’s position in the political arena. The heritage declaration was interpreted as a dissent device intended to accumulate symbolic capital and obtain social legitimacy and institutional approval. It was not proposed as a vehicle for identity expression or historical ties, but for pragmatic, rationalist and instrumentalist reasons, given the dominant rhetoric within the institutional sphere. In other words, he considered the discourse of heritage as the most suitable tool to achieve the movement’s political demands and increase its control over its own past, identity and territory.

His arguments were well received by the Casa del Pumarejo’s residents because of their pragmatism and even more so by the middle-aged neighbours who had a prior heritage awareness. However, his strategic view was not shared by some anarchist youngsters, who left the mobilisation, frustrated by the drift towards heritagisation. This group’s counter-heritage view may be summarised into four main objections. First, a critique of state dependency: heritage approval entailed validation of those antagonists ―such as the State― that threatened to discipline and domesticate the movement using the heritage declaration as a regulatory device. Second, they critiqued the alienation and fetishism dynamics: heritage recognition would not resolve the neighbours’ housing problems, but, rather, conceal the conflict’s socioeconomic origin and blur the confrontation between owners and tenants. This group believed that the struggle for the neighbours’ material conditions was based on direct experiences of inequality, whereas the struggle for heritage (as normatively and legally understood) was more ethereal, as it concentrated on the building’s symbolic values. Third, they critiqued the discrepancies between means and ends: appropriation of the hegemonic language of heritage for counter-hegemonic purposes would hinder prefigurative political actions and limit the movement’s creative and institutive power. Finally, they also critiqued voluntary servitude: applying for the heritage declaration meant adopting a ‘slave morality’ (Nietzsche [1887] Citation2017); that is, surrendering one’s ‘will to power’ for the benefit of the masters ―the heritage institutions― which make unilateral decisions about the cultural authenticity of otherness. In the following excerpt, a former ACP activist explains his reasons for opposing the heritagisation process:

The moment we began to discuss the heritage stuff all the masks fell off… It became clear who was who! Those who wanted to beg daddy-State for absurd recognition … And those who fought for more real things: that people don’t die of hunger or get evicted from their homes. The funny thing is that those who believed this heritage hoax said we were ‘childish’. While they wanted to dismantle the master’s house … with the master’s tools!Footnote8 I would call that a lack of imagination. No outsider’s gonna come and tell me who I am!

In any case, most of the neighbours and activists shared the professor’s strategic view and, following an intense debate, decided to initiate the heritage declaration procedure. With Hernández’s expert technical support, several activists conducted research on the building’s architectural elements and historical uses by means of oral and archival sources. This knowledge helped to substantiate the application, while promoting feelings of dignity, pride and sense of place (Smith Citation2006). During the process, the activists discovered the practicality of heritage for reactivating hidden memories, regulating local identity, formalising tradition, resignifying the territory and achieving citizen rights.

Once the application was submitted, they closely followed the bureaucratic process. In the beginning, they conformed to the administrations’ prevailing waiting times and exhausted all the citizen participation mechanisms established by law. However, the lack of institutional response caused them to progressively turn to more expressive, performative and assertive actions (). For example, on 7 June 2001, a dozen activists showed up at the Andalusian Directorate General for Cultural Heritage to present the public officers with a piece of a balustrade that had fallen off the patio. This tangible proof of the Casa del Pumarejo’s architectural decay highlighted their concern for heritage and reminded the administrations of the need to accelerate the listing process.

Figure 6. Banner: Beware! You have 27 days left to declare it a monument. Listing now! 2003. ACP archive.

Between 2001 and 2003, the banners’ messages underwent a significant change in order to integrate the notion of heritage into the struggle. In contrast to the previous empirical denunciation of the opponents, the ACP now circulated metacultural narratives that redefined the conflict in constructive, proactive terms (). The representational power of heritage was used to arouse the citizens’ connection to Casa del Pumarejo, showing it to be an emblematic rallying point within the urban fabric. This heritagisation strategy was accompanied by a revaluing of the neighbourhood’s stigmatised identity through anamnesis practices that promoted an intergenerational exchange of experiences between neighbours and activists (oral memory workshops, compilation of old photographs, interviews with neighbours, etc.), and established symbolic linkages between the concept of heritage, the neighbours’ modus vivendi and the neighbourhood’s local history.

The ACP’s drift towards hyper-heritagisation

After a long administrative procedure, on 26 June 2003, the Andalusian Regional Government listed Casa del Pumarejo in the General Catalogue of Historical Heritage as a Cultural Interest Asset, albeit without mentioning the ACP’s heritage activation work. It was a comprehensive heritage listing, since it recognised both the building’s material elements (the columns, tiles and balustrades) and the ethnological wealth of local lifestyles and the tenants’ forms of sociability. Thereafter, the activists showcased the declaration until they stopped the hotel project and achieved the municipalisation of the building and the right to use some of its facilities through collective management. However, the attainment of their initial demands did not mean the end of the mobilisation, but the beginning of a new political cycle in which heritage operated as a catalyst for collective action. The activists no longer presented their interests as radically opposed to the municipal authorities ―instead, they legitimately used the declaration as cultural capital to facilitate political negotiations.

The heritage declaration served multiple functions. Firstly, it served as a connective platform or interface for mediation (Hooper Citation2018) with heterogeneous agents (public officers, technical specialists, universities, etc.), since it allowed the activists to appear as potential collaborators and to advise municipal technicians on heritage. Secondly, it operated as an emotional device for the social movement’s political subjectivation and recodification. The text of the declaration was posted on a visible wall at Casa del Pumarejo with those excerpts extolling the building’s temporal depth and artistic exceptionality underlined.

However, the heritage declaration was not only instrumentalised by the activists, but by the public administrations as well. The neighbours’ current problem lies in the fact that the institutions use the heritage listing to establish zonings and security measures that hinder circulation through the building. This intervention dissociates the heritage asset from its instrumental function, by granting epistemic priority to conservationist ethics (the view of the building as a monument) over the neighbours’ residential logic (the view of the building as a home). That is, the safeguarding instruments impose procedural frameworks and value hierarchies that conceal the cognitive dissonance of heritage. The practical consequence is that the mere presence of residents is considered harmful for the monument’s preservation, while their lifestyles become reified. In sum, the declaration serves ambivalent functions, since it provides the social movement with a tool for protection and resistance against real-estate speculation, while simultaneously providing the heritage administrations with an artefact for subjection and technical management.

It is worth noting, however, that the declaration’s discursive force has by itself been insufficient to predispose all neighbours and activists towards a positive assessment of heritage. Rather, the latter’s conversion into a dominant symbol has been achieved by means of pedagogical subjectivation technologies: guided tours, conferences on historical memory, colloquia with experts (architects, archaeologists, art historians, etc.). These re-education schemes have progressively anchored the value and significance of heritage through the mobilisation of emotion. According to the activists, the most effective actions are guided tours of the building, since they facilitate an in situ objectivation of heritage values by direct experience and face-to-face interactions. The ethnographic observation of these ritual itineraries during my fieldwork unveils the tactical connection between heritage and identity narratives from a certain ‘strategic essentialism’ (Spivak Citation1987). The following excerpt from my field journal shows the deliberate selection of certain heritage elements to convey various ideologies, such as Andalusian nationalism, the critique of urban gentrification and the praise of the social value of self-management:

When the group of visitors reaches the main patio, a young woman slows down to gaze at the base of tiles. Before she poses any questions, Salva ―who today acts as the cicerone― begins to extol the patio’s singularities. He explains that the tiles are dry-string, oven-baked in an old working-class Sevillian neighbourhood (Triana), and that the patio’s decorative style is Mudejar. This explanation is accompanied by a critique of urban transformations in former industrial neighbourhoods and a digression about Muslim influence on Andalusian culture. When he finishes, the girl says that the patio makes her feel ‘like a sultanah’ and asks about other buildings in Seville with similar mosaics. Salva recommends some places to visit, but adds that the Pumarejo tiles are unique. He makes a dramatic pause to elicit the group’s attention and concludes, ‘They are unique because, given the politicians’ blatant neglect, the neighbours take care of their heritage’.

As the ethnographic description shows, the ACP does not passively adopt the Authorised Heritage Discourse (Smith Citation2006), but, instead, resignifies and goes beyond hegemonic heritage contents to produce vernacular narratives. Hence the coining of the term rampant heritage to designate the subversive uses of heritage to fight social injustice, as well as its constructive uses for promoting ethical and human values opposed to the dominant morality (caring, diversity, participation, etc.). They thus transform heritage into a tool for producing new cultural meanings and a mechanism to negotiate alternative forms of knowledge and co-existence, while collaborating with university research groups and engaging in dialogue with contemporary heritage theory through participation in international meetings.

During my field work, I had the opportunity to identify at least four areas in which the ACP’s concept of rampant heritage challenges nineteenth century theoretical assumptions. First, it critiques the use of heritage to freeze and glorify the past, as essentialist paradigms tend to do; instead, it presents Casa del Pumarejo as a living heritagisation process, with a strong experiential component and a will to update the past in order to intervene in the present (). Second, it questions classist, conservative views of heritage that only value the dominant classes’ cultural expressions, by presenting Casa del Pumarejo as popular-class heritage and a site to celebrate the neighbourhood’s diversity and multiculturalism (). Third, it challenges the vertical, commanding heritage management style typical of expert discourse, by presenting it as the opposite of the Casa del Pumarejo’s horizontal, participatory, assembly-based governance model. Finally, it denounces the scarcity of institutional actions designed to revert the privatisation and commodification of heritage, by presenting Casa del Pumarejo as collective, common heritage, and invoking the citizenry as the political subject that takes care of its heritage through the neologism cuidadaníaFootnote9 ().

Figure 8. Banner: We manufacture space and time. We update our past. 2018. Photograph by the author.

Figure 9. Banner: Since the beginning of this century, the lights are guiding us to create a cultural melting pot in the neighbourhood. 2018. Photograph by the author.

Figure 10. Banner: Cuidadanía in action defends the common heritage. 2018. Photograph by the author.

Subjectivation within the discursive regime of heritage thus reconfigures the activists’ prior identity and leads to a change in political action. The incorporation of heritagisation discourse entails a breakage with previous forms of dramatising the conflict and an overall reassessment of the purposes of the mobilisation. The protest’s discursive framework has moved from the denunciation of housing inequalities to the affirmation of the social values of heritage through metacultural narratives. The practical consequence has been a weakening of the ACP’s alliances with neighbourhood associations and Squatted Social Centres, and a strengthening of solidarity networks with national and international universities and heritage institutions and movements. This subjective incorporation of heritage values is particularly noteworthy among the new generations of activists, mostly university students of architecture, anthropology or art history who come into contact with Casa del Pumarejo through internships.

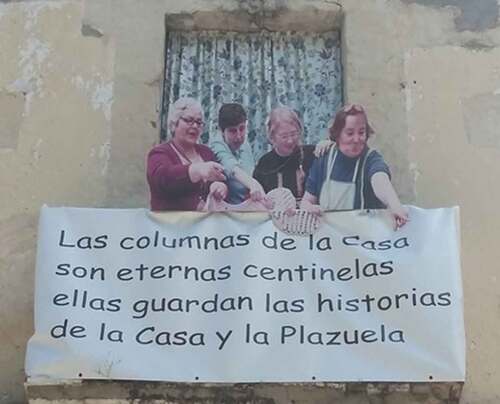

In recent years, most of the Casa del Pumarejo’s banners include celebratory messages that highlight the official heritage listing and the singularity of certain architectural elements, such as the columns (). Whereas in the beginning the ACP used a directly confrontational and largely spontaneous rhetoric to denounce the neighbours’ everyday problems, the mobilisation has now moved towards identity affirmation and a reflexive recognition of cultural difference. The initial instrumentalisation of heritagisation discourse has drifted towards a deep affective involvement with heritage, has ceased to be merely a symbolic pretext to become the main motivation for political resistance. In our interviews, some activists explained that the assimilation of the fetishistic, transcendental, post-materialistic values of heritage has led to a docile activism that hinders combative expression:

Sometimes I wonder whether we’re losing the original essence. That more feline thing … Which has now been watered down by this heritage issue. I mean… Heritage has given us many positive things: we get visits from many different places, we’re a referent for many things and we have our backs covered just in case. But I sometimes miss showing our claws a bit more. Because it’s not the same to say ‘you’re going to make these neighbours die of sorrow’ than ‘hey, mister city hall, look at the decay of these tiles’.

Figure 11. Banner: The house’s columns are eternal sentinels. They preserve the House’s and the Plaza’s history. 2018. Photograph by the author.

Figure 12. This House has the same listing as the Giralda: Monument. 2018. Photograph by the author.

Our longitudinal study of the ACP’s history evinces three big paradoxes or controversial consequences of the drift towards hyper-heritagisation. First, a substantial change in the activists’ class origins and political motivations, such that the struggle for the recognition of popular heritage is increasingly championed by the middle, creative and intellectual, classes, while the historical neighbourhood, trade unions and other working-class movements are aggregated to a lesser extent. Second, a gradual convergence with capitalist interests that capture the symbolic surplus value of the heritage listing (real estate developers, politicians, tourist agencies, etc.). As we have noted in other publications, the activists’ demand for rehabilitation is negotiated with public officers who associate heritage with urban regeneration and intend to transform the Casa del Pumarejo’s surroundings into a focal point for economic investment (Roura-Expósito Citation2019). Third, the contradictions inherent in subaltern groups’ struggles for recognition, which elicit heated theoretical debates between Marxist, feminist and post-structuralist positions (Butler Citation1997; Fraser Citation2000). The paradox lies in that the potential of heritage for cultural self-affirmation has ended up co-existing with subservience to the schemes of capital and neoliberalism.

Conclusion

The increasing interweaving between heritage and social movements has favoured the consolidation of a new field of study devoted to the particularities of heritage defence activism (Jones, Mozaffari, and Jasper Citation2018). However, despite this growing academic interest, the field is still under-theorised and lacking in ethnographic and comparative studies (Mozaffari and Jones Citation2019; Hammami and Uzer Citation2022). Our theoretical approach moves away from positivist postulates that interpret heritage and social movements as empirical facts or pre-existing ontological entities, and, instead, shows that both concepts are subject to conflictive, unfinished social construction processes. On the one hand, the activists contribute to the construction of heritage; on the other, the heritage statement leads to the emergence of a singular style of civic activism. However, our analysis suggests that the condition of possibility for heritage activism is a prior subjectivation in the significance and transcendental value of heritage. In non-heritage contexts subject to multiple inequalities, there is a risk that heritage may be imposed from the outside, in an act of terminological reification which has ambivalent consequences for activism.

Our case study confirms that social movements have a certain ability to appropriate the normative language of heritage for non-violent resistance to the dispossession of their identity, past and/or territory (Smith and Campbell Citation2011; Conget Citation2014; Hammami and Uzer Citation2018). The discursive versatility of heritage provides social movements with the opportunity to channel their collective yearning for self-affirmation (revaluation of their own site of enunciation) and to dramatise their opposition to neoliberal trends they experience as frustrating (political contestation of hegemonic projects). In this regard, the concept of Political Opportunity of Heritage (POPH) can be applied to the strategic mobilisation of heritage as an instrument for the legitimation of multiple political subjects within the new cultural economies (Santamarina and Mompó Citation2021). Such a thematisation shows the capacity of social movements to reinvent themselves, as well as their potential to update citizens’ sensitivities and renew their protest repertoires (Diz, Estévez, and Martínez-Buján Citation2022). It is worth noting that the ACP’s activist strategies include the conceptualisation in terms of heritage of intangible aspects of culture (the neighbourhood’s lifestyle, its community-based organisation, local memory, etc.) which were previously integrated within other discourses of resistance.

Our analysis of the Casa del Pumarejo’s heritagisation process reveals practical and symbolic effects that favour social transformation. On a practical level, the heritage declaration has operated as a legal guarantee for the preservation of the neighbours’ residential uses and prevented privatisation of the building, but it has also imposed conservationist ethics that subordinate frameworks of local sense of place to expert management. On a symbolic level, the dominant meaning of heritage has brought together heterogeneous militant experiences under the same transversal demand for recognition. Rampant heritage as a driving force condenses the movement’s collective identity, facilitates achieving a certain degree of political agency and partially challenges nineteenth century heritage paradigms of specific institutions (essentialist, conservationist, expert, etc.). In this sense, activism promotes the emergence of new heritage values, operating as a vehicle for democratisation and an epistemic transformation of the heritage field.

However, social movements not only contribute to the configuration of heritage ―they are also affected by the hegemonic structure of heritage institutional management. In this article, we have shown the paradoxical consequences of incorporating heritage demands into the political agenda. Firstly, we have pointed out the ideological critiques of activist groups that oppose the heritagisation process for fear of state dependency and alienation dynamics, from positions influenced by autonomism, Marxism or post-structuralism. These counter-heritage activists believe that the notion of heritage is insufficient to metabolise all the conflicts in the social arena (especially materialistic or redistributive demands). Secondly, our field work highlights various challenges faced by heritagisation activism: the loss of militants among the popular sectors, its unexpected convergence with neoliberal dynamics and the complex dialectics between the acquisition of public recognition and institutional co-optation.

A final focus of analysis points out the biopolitical effects of heritage on the regulation of conducts, ways of thinking and the figurative style of political action. The ACP’s example shows that the thematisation in terms of heritage has replaced more disruptive struggle strategies (direct action) and generated a tendency to collaborate with the public administrations (participatory negotiations). The domestication effects of heritage are partly illustrated by the historical transformation of the banners on the Casa del Pumarejo’s balconies. On the one hand, the initial artisan red-and-black forms gave way to stylish fonts and digital printing. On the other, the slogans, which initially linked the conflict to empirical political causes (evictions, asustaviejas, speculation) using popular, direct and antagonistic mobilisation repertoires, are currently articulated around historical depth, intangible values and ethnological exceptionality; i.e. an expert discourse based on metacultural appreciation and a predisposition to enter into agreements with the previously contested powers.

Our case study highlights the virtues, risks and ambivalence underlying the rampant uses of heritage. As a discourse of power, heritage has allowed the ACP to renew its confrontation repertoires, negotiate the redistribution of resources and conquer spaces of autonomy. However, as an experience of subjectivation, it has had the controversial effect of generating an epistemic gap inside the activist group, reducing its power to bring people together, disciplining its forms of protest and exposing it to administrative control. As academics, we need to further connect collective action theories and critical heritage studies in order to contribute to the debate ―already present within the activist movement itself― as to whether heritage is a language for showing one’s claws or a melody for taming resistance.

Acknowledgments

I thank all the neighbours and activists of the Casa del Pumarejo for sharing their valuable time and knowledge with me. I would also like to thank Jacqueline Cruz for her involvement in the translation of the article, as well as my thesis directors Cristina Sánchez-Carretero and Carlos Diz and researchers Pablo Alonso and Ana Pastor for their advice on how to improve the theoretical approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joan Roura-Expósito

Joan Roura-Expósito (Vilafant, 1986) has a Bachelor’s Degree in Social and Cultural Anthropology (2010) and a Master’s Degree in Anthropology and Ethnography (2013), both from the University of Barcelona. He has published several books and articles, in Spanish and English, on indigenism, migrations and sports in the Plurinational State of Bolivia. Currently, he is working as a predoctoral researcher at the Institute of Heritage Sciences in Santiago de Compostela under an FPI fellowship and is writing his doctoral dissertation on the risks of participatory governance in heritage.

Notes

1. For situated knowledge about the history of Casa del Pumarejo, the groups involved in its everyday management and the activities organised by the ACP, you may visit its website: https://pumarejo.org/. The website also shows the common spaces created by the movement: the Centro Vecinal [Neighbourhood Centre] (a space for activities), the Bajo 5 [Ground Floor 5] (a space for group meetings) and the popular library Rosa Moreno (a space for book loans). The ACP uses these common spaces to disseminate its view of the world, ideology and languages through various types of free activities open to the citizenry.

2. Naturally, this division into historical stages is used for heuristic purposes only. We do not intend to propose an evolutionary, sequential and/or deterministic model for the movement, but use these analytical categories to understand the variability of its thematisations.

3. Renta antigua agreements are those signed prior to 9 May 1985, and are regulated by Decree 4101/1964, of 14 December. Their main features are their long duration and indefinite extension periods, and the virtual impossibility of raising the prices. Although they are intended to protect the tenants, they have often led to lack of upkeep of the buildings, mobbing practices and forced evictions.

4. The casas de vecindad, also known as corralas, are typical Spanish popular-class dwellings built around a courtyard and with shared facilities for the residents.

5. We wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation, which contributed to broadening our conceptualisation of heritage to include its non-official views.

6. Emic word used by the popular classes to designate people who pressure tenants so that they vacate the premises in favour of the owners.

7. All English translations are the author’s.

8. The activist is adapting Audre Lorde’s well-known dictum ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,’ uttered by the Afro-American feminist intellectual during the Second Sex Conference (New York, 1979).

9. The best English translation of cuidadanía is care-tizenship. However, this term does not convey the Spanish play on words, since the concept of cuidadanía emerges from the common typographical error when writing ciudadanía (citizenship). With this small change in the order of the vowels, the activists suggest that political belonging is not based on administrative issues, but on the establishment of caregiving ties (also with respect to heritage).

References

- Alonso González, P. 2018. The Heritage Machine: Fetishism and Domination in Maragatería, Spain. London: Pluto Press.

- Alonso González, P., D. González-Álvarez, and J. Roura-Expósito. 2018. “ParticiPat: Exploring the Impact of Participatory Governance in the Heritage Field.” Political and Legal Anthropology Review 41 (2): 306–318. doi:10.1111/plar.12263.

- Appadurai, A. 1995. “The Production of Locality.” In Counterworks: Managing the Diversity of Knowledge, edited by E. Farbon, 204–225. London: Routledge.

- Barber, S., V. Fresnel, and M. J. Romero (Coords). 2006. El Gran Pollo de la Alameda. Seville: Consejo Redactor del Gran Pollo de la Alameda.

- Beeksma, A., and C. De Cesari. 2019. “Participatory Heritage in a Gentrifying Neighbourhood: Amsterdam’s Van Eesteren Museum as Affective Space of Negotiations.” Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (9): 974–991. doi:10.1080/13527258.2018.1509230.

- Bendix, R., A. Eggert, and A. Peselmann. 2012. Heritage Regimes and the State. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611.

- Butler, J. 1997. “Merely Cultural.” Social Text 52 (52/53): 265–277. doi:10.2307/466744.

- Byrne, D. 2014. Counterheritage: Critical Perspective on Heritage Conservation in Asia. New York: Routledge.

- Choay, F. 2007. Alegoría del patrimonio. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

- Conget, L. 2014. “Usos políticos reivindicativos del patrimonio en la ciudad: El caso de la red Vecinos por la Defensa del Barrio Yungay.” In Usos políticos del patrimonio cultural, edited by F. Van Geert, X. Roigé, and L. Conget, 129–170. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona.

- De Cesari, C., and M. Herzfeld. 2015. “Urban Heritage and Social Movements.” In Global Heritage: A Reader, edited by L. Meskell, 171–195. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Dellios, A., and E. Henrich. 2020. Migrant, Multicultural and Diasporic Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Diz, C., B. Estévez, and R. Martínez-Buján. 2022. “Caring Democrazy Now: Neighborhood Support Networks in the Wake of the 15-M.” Social Movements Studies 1–20. doi:10.1080/14742837.2022.2033115.

- Foucault, M. 2000. Defender la sociedad. Buenos Aires: FCE.

- Franquesa, J. 2013. “On Keeping and Selling: The Political Economy of Heritage Making in Contemporary Spain.” Current Anthropology 54 (3): 346–369. doi:10.1086/670620.

- Fraser, N. 2000. “Rethinking Recognition.” New Left Review 3: 107–120.

- García Canclini, N., and IAPH. 1999. “Los usos sociales del Patrimonio Cultural.” In Patrimonio Etnológico: Nuevas perspectivas de estudio, edited by E. Aguilar, 16–33. Comares: IAPH.

- García Jerez, F. A. 2009. Trazos de la ciudad disidente: Espacios contestados, capital simbólico y acción política en el centro histórico de Sevilla. PhD diss., Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

- García-Lamarca, M. 2017. “Creating Political Subjects: Collective Knowledge and Action to Enact Housing Rights in Spain.” Community Development Journal 52 (3): 421–435. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsx025.

- Gentry, K., and L. Smith. 2019. “Critical Heritage Studies and the Legacies of the Late-Twentieth Century Heritage Canon.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11): 1148–1168. doi:10.1080/13527258.2019.1570964.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis. New York: Harper.

- Gómez Ferri, J. 2004. “Del patrimonio a la identidad: La sociedad civil como activadora patrimonial en la ciudad de Valencia.” Gazeta de Antropología 20: 9–20. doi:10.30827/Digibug.7260.

- González Bracco, M. 2014. “Asociaciones patrimonialistas en la ciudad de Buenos Aires: Apuntes para una genealogía.” Cuaderno Urbano 16 (16): 51–68. doi:10.30972/crn.1616268.

- Hafstein, V. 2012. “Cultural Heritage.” In Companion to Folklore, edited by R. Bendix and G. Hasan-Rokem, 500–519. Oxford: Malden.

- Hammami, F., D. Jewesbury, and C. Valli. 2022. Heritage, Gentrification and Resistance in the Neoliberal City. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Hammami, F., and E. Uzer. 2018. “Heritage and Resistance: Irregularities, Temporalities and Cumulative Impact.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (5): 445–464. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1378908.

- Hammami, F., and E. Uzer. 2022. Theorizing Heritage Through Non-Violent Resistance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harrison, R. 2010. “Heritage as Social Action.” In Understanding Heritage in Practice, edited by S. West, 240–276. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hernández-Ramírez, J. 2003. “La construcción social del patrimonio: Selección, catalogación e iniciativas para su protección. El caso del Palacio del Pumarejo.” In Antropología y Patrimonio: Investigación, documentación e intervención, edited by V. Quintero and E. Hernández, 84–95. Seville: Junta de Andalucía.

- Hernández-Ramírez, J. 2005. “De resto arqueológico a patrimonio cultural: El movimiento patrimonialista y la activación de testimonios del pasado.” Boletín Gestión Cultural 11: 1–19.

- Hooper, G. 2018. Heritage at the Interface: Interpretation and Identity. Gainesville: University of Florida.

- Hviding, E., and K. Rio. 2011. Made in Oceania: Social Movements, Cultural Heritage and the State in the Pacific. Wantage: Sean Kingston Publishing.

- Jiménez-Esquinas, G. 2017. “El patrimonio (también) es nuestro: Hacia una crítica patrimonial feminista.” In El género en el patrimonio cultural, edited by I. Arrieta, 19–48. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco.

- Jones, T., A. Mozaffari, and J. Jasper. 2018. “Heritage Contests: What Can We Learn from Social Movements?” Heritage & Society 10 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/2159032X.2018.1428445.

- Jover Báez, J., and I. Díaz Parra. 2020. “Gentrification, Transnational Gentrification and Touristification in Seville, Spain.” Urban Studies 57 (15): 3044–3059. doi:10.1177/0042098019857585.

- Lefebvre, H. 2013. La producción del espacio. Madrid: Capitán Swing.

- Morell, M. 2011. “Working Class Heritage Without the Working Class: An Ethnography on Gentrification in Ciutat (Mallorca).” In Heritage, Labour and the Working Class, edited by L. Smith, P. A. Shackel, and G. Campbell, 288–302. London: Routledge.

- Mozaffari, A., and T. Jones. 2019. Heritage Movements in Asia: Cultural Heritage Activism, Politics & Identity. New York: Berghahn.

- Nietzsche, F. 2017. Nietzsche: On the Genealogy of Morality and Other Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Quintero Morón, V. 2009. Los sentidos del patrimonio: Alianzas y conflictos en la construcción del patrimonio etnológico andaluz. Seville: Fundación Blas Infante.

- Robertson, J. M. I. 2008. “Heritage from Below: Class, Social Protest and Resistance.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, edited by B. Graham and P. Howard, 143–158. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Robertson, J. M. I. 2012. Heritage from Below. London: Ashgate.

- Roura-Expósito, J. 2019. “El discreto encanto de la participación en el proceso de patrimonialización de la Casa del Pumarejo (Sevilla).” In El imperativo de la participación en la gestión patrimonial, edited by C. Sánchez Carretero, J. Muñoz-Albaladejo, A. Ruiz-Blanch, and J. Roura-Expósito, 79–108. Madrid: CSIC.

- Sánchez-Carretero, C., J. Muñoz-Albaladejo, A. Ruiz-Blanch, and J. Roura-Expósito. 2019. El imperativo de la participación en la gestión patrimonial. Madrid: CSIC.

- Santamarina, B. 2014. “El oficio de la resistencia. Salvem y Viu al Cabanyal como formas de contención del urbanismo neoliberal.” Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares 69: 305–326. doi:10.3989/rdtp.2014.02.003.

- Santamarina, B., and E. Mompó. 2021. “The Political Opportunity of Heritage: Appropriations, Memories, and Identities in Cabanyal.” Anthropological Quarterly 94: 313–344. doi:10.1353/anq.2021.0004.

- Schmidt, P., and I. Pikirayi. 2016. Community Archaeology and Heritage in Africa. London: Routledge.

- Silva-Escobar, P. 2021. “Monumento, espacio público, y poder simbólico: El caso de la estatua del General Baquedano y el uso político del patrimonio.” In Multiplicidades del Patrimonio, edited by A. Castro San Carlos, C. Burdick, and J. P. Silva-Escobar, 18–50. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Mayor.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Smith, L., and G. Campbell. 2011. “Don’t Mourn Organize1: Heritage, Recognition and Memory in Castleford, West Yorkshire.” In Heritage, Labour and the Working Classes, edited by L. Smith, P. Shackel, and G. Campbell, 85–105. London: Routledge.

- Spivak, G. 1987. In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics. New York: Methuen.