ABSTRACT

Several scholars have emphasised the impact of gender on the notion, uses, and practices of heritage. Critical research dealing with gender, sexuality, and heritage is, however, rare. This article examines the research on gender and heritage across social sciences and humanities and shows how it is also gendered. Our meta-synthesis of articles selected from the Web of Science (WOS) combines a quantitative analysis of bibliometric information and coded contents of 427 relevant articles with a close reading of a sub-sample of 13 articles that explicitly deconstruct the binary gender system and its heteronormativity by focusing on LGBTQI minorities. Our results indicate that the articles on gender and heritage are predominantly written by one woman author, and related to this, mainly focus on cis women or femininity, which partly perpetuates a bias that gender is a ‘women’s issue’. Moreover, the analysed scholarship is Western dominated and Eurocentric. Although the articles in our sub-sample critically explore narratives, events, and sites dealing with LGBTQI minorities and their participation in heritage by queering it, the studies lack a critical approach to the notion of heritage and the use of power in heritagization processes.

Introduction

During the past few decades, global scholarly interest in heritage has grown enormously, drawing on the development in global heritage governance and intertwined social, environmental, and technological changes that impact on preserving, conserving, exhibiting, and managing heritage (Su, Li, and Kang Citation2019; SoPHIA Citation2020; Vlase and Lähdesmäki Citation2023). The increase in research reflects the expansion of the notion of heritage, its social impact, and academic approaches to it. Like many other fields in social sciences and humanities, heritage research has been impacted by critical theory exploring various aspects of power, such as hierarchies and uneven power relations, explicit and implicit politics of dominance and oppression, silenced and marginalised narratives and representations, and alternative, emancipatory, and empowering identity projects (Lähdesmäki, Zhu, and Thomas Citation2019). Laying the foundation for Critical Heritage Studies, Smith (Citation2006) underlines the taken-for-granted power structures embedded in the historical notion of heritage, which require critical exploration. These range from nationalist, colonialist and imperialist worldviews to elitism in heritage practices and social exclusion based on class, race, ethnicity, indigenousness, and gender.

A broad body of recent research has sought to deconstruct the power relations in heritage – particularly its nationalist, colonial legacy and oppressive, marginalising, or racist heritage practices. Although critical theory has identified gender as a key category of difference impacting the hierarchical use of power (e.g. Hall Citation1996, Citation2017), research on gender dynamics in heritage remains rare (Colella Citation2018). Critical scholars have, however, emphasised that explicit recognition of gender is ‘appropriate in all heritage situations’ (Levy Citation2013, 90). For Smith (Citation2008, 161), definitions and discourses of heritage are gendered, and this ‘reproduces and legitimises gender identities and the social values that underpin them’. Indeed, the historical notion of heritage heavily draws on privileged masculine positions, practices, and perceptions that have dominated definitions, interpretations, preservation, and values of heritage (Smith Citation2006; Colella Citation2018; Council of Europe Citation2018).

The aim of our article is to give an overview of research on gender and heritage across social sciences and humanities and to explore how such research is gendered and intersects with the geography of privilege in academia (Winddance Twine and Gardener Citation2013), i.e. how it is distributed across global scholarship. Our meta-synthesis is of articles selected from the Web of Science (WOS) – the core global index of more than 50,000,000 articles covering 250 scientific categories and about 150 research areas. Our research combines a quantitative analysis of WOS data and coded contents of 427 articles on gender and heritage, and a close reading of a sub-sample of 13 articles that focus on LGBTQI minorities. We ask: How has the research on gender and heritage indexed in WOS developed over the past two decades and what are its key characteristics? Whose gender and heritage does this research seek to explore? How does the research challenge the binary gender system and heteronormativity? Based on our results, we suggest how research on gender and heritage could be developed in future.

Our questions are prompted by the contradiction between our first observation of gender and heritage articles in WOS and the conclusions of critical research on the topic. While scholars have identified ‘a broader lack of attention to gender issues in the field of cultural heritage’ (Colella Citation2018, 250), hundreds of articles were available in WOS. As our analysis indicates, the way of addressing gender in cultural heritage varies greatly in scholarship. Reading (Citation2015, 398) points out that research on gender and heritage is commonly focused on four themes: representation of gender in heritage; the role of gender in consuming heritage; the impact of gender in curating and managing heritage; and issues of gender in heritage policies. Our study provides a metalevel view of the impact of gender on heritage research. We argue that few feminist or queer scholars aim at critical exploration of the gender binary, gendering as a practice in heritage, and heteronormativity of heritage. Moreover, our study reveals a lack of critical understanding of the concept of heritage and the power structures embedded in it. While the concept and ontologies of heritage have been rethought in Critical Heritage Studies (e.g. Smith Citation2006; Harrison Citation2013, Citation2018), heritage often remains an uncritical term in other fields of scholarship. We argue that the inherent conservatism included in broad, uncritical notions of heritage may lead to research in which the concept is used but not deconstructed, theorised, or related to the operation of power. In our article, we seek to show how structures of knowledge, such as normative understandings of gender and heritage, impact scholarship and limit its scope and diversity.

In this article, we draw on the critical epistemologies of intersectional feminist theory that explores gender in relation to a wider spectrum of categories of the other (McCall Citation2005; Shields Citation2008; Tong Citation2009; Walby, Armstrong, and Strid Citation2012). We complement this basis with quantitative analysis that Colella (Citation2018, 267) summarises as one of ‘the recommendations and suggestions that scholars have put forward as strategies of change’ in exposing gender biases in the field of heritage.

Data and methods

We selected the examined articles in a several steps. First, we performed a search using Boolean operator AND in the field Topic (TS) in WOS to obtain results that contain both key terms of interest, gender and heritage, in the title, keywords or abstract. Second, from the initial 1200 articles found on 12 October 2022, we removed the bibliometric information for 374 articles after an examination of their WOS categories. The main fields outside the scope of our study were first excluded automatically using the ‘refine results by selected’ function. These included Endocrinology & Metabolism; Nursing; Immunology & Infectious Diseases; Neurosciences & Psychiatry; Substance Abuse; Geriatrics & Gerontology; Social work; Medical Laboratory Technology; Dentistry, Oral Surgery & Medicine; and Medicine. Before removing articles in these fields from the dataset, we read the titles, keywords, and abstracts of the articles to confirm their irrelevance for the present study. As a result, we returned 12 articles out of the subsampled 374 articles to the dataset. Third, we examined the titles, keywords, and abstracts of the remaining 826 articles based on our agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria regarding gender drew on gender identities of men, women, boys, and girls; features of masculinity and femininity; masculine, feminine or gendered practices; gender roles; ways of doing or performing gender; ways of blurring binary gender categories; and issues regarding LGBTQI minorities. The inclusion criteria regarding heritage drew on how it is defined in UNESCO conventions and charters on natural heritage (including natural features, geological formations, and natural sites) and cultural heritage (including monuments, buildings and sites) (UNESCO Citation1972), intangible cultural heritage (including traditions, social practices, rituals, festive events and traditional crafts) (UNESCO Citation2003b), and digital heritage (digital materials and digitised heritage) (UNESCO Citation2003a). Most of the included articles dealt with tangible or intangible cultural heritage.

The exclusion criteria included the following uses of gender and heritage: gender as a grammatical term (e.g. a specific form of noun class system); heritage as a linguistic term (e.g. heritage language or heritage speakers as (socio)linguistics terms referring to minority language speakers); heritage in the names of peoples, places or institutions; heritage as a synonym for ethnic cohorts (e.g. a person’s African heritage); and heritage as a broad and general term for a certain phase of history and its ethos (e.g. Soviet heritage).

Based on these inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as on the content assessment of each title, keywords, and abstract, we introduced variables enabling in-depth quantitative exploration of the final dataset. The following variables were added to the Excel dataset file exported from WOS: relevance coded binary (1 = relevant, 2 = irrelevant for our study aim); number of authors as a continuous variable; authors’ gender as a categorical variable based on their contact information (1 = male, 2 = female, 3 = male and female, 4 = unidentifiable, 5 = other)Footnote1; and explicit gender focus of the studyFootnote2 in relation to either men and masculinity (1), women and femininity (2) or no explicit gender focus or both being more or less equally mentioned (3). In addition, our coding was extended to include variables capturing the presence/absence of LGBTQI minorities explicitly mentioned in the title, keywords, or abstract which was coded binary (1 = no, 2 = yes). Likewise, if the title, keywords or abstract explicitly referred to a geographical location, such as a country, region, or continent, we used open coding for this information which resulted in a sample of over 80 locations that were subsequently recoded into seven categories grouped by continents: Europe = 1 (including Russia), Asia = 2 (including Middle East and Turkey), Africa = 3, Latin America = 4, North America = 5, Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania = 6, and multiple continents = 7. Following the same logic, we coded the background of corresponding authors into categories of Western (1, 5, and 6) and non-Western (2, 3, and 4) locations based on their contact information. Finally, our coding included a variable capturing the presence of explicit reference to a national, ethnic, religious, or linguistic minority (including immigrants and refugees) (1 = yes, 2 = no, 3 = colonial past or other explicit influence of a foreign hegemonic culture in another country). Throughout the individually conducted coding process, we used the value ‘99’ when we lacked sufficient evidence or were unsure of the appropriate code. Upon completion of the coding, we jointly discussed the ambiguous situations and solved them by searching for additional information in the full articles. The final dataset of 427 relevant articles was confirmed after a careful coding crosscheck.

We conducted our analysis according to the guidelines provided by Hoon (Citation2013, 530) who states that a ‘meta-synthesis is defined as an exploratory, inductive research design to synthesise primary qualitative case studies for the purpose of making contributions beyond those achieved in the original studies’. Hoon (Citation2013) proposes eight steps for conducting meta-synthesis: (1) framing the research question; (2) locating relevant research; (3) defining inclusion/exclusion criteria of studies; (4) extracting and collecting data from the sampled studies; (5) analysing the relationship between the coding variables to understand underlying themes, patterns of associations, and contrasts; (6) producing a synthesis of findings on cross-study level; (7) building theory from meta-synthesis; and (8) discussing the limits and contribution of the meta-synthesis. We followed these steps in our analysis. Instead of theory building, we dived deeper into a small group within our dataset, namely the 13 articles dealing with LGBTQI minorities. With qualitative close reading we explored how these 13 articles link gender and heritage and how they approach power structures embedded in a heteronormative binary gender system and heritage practices.

Quantitative findings

Using WOS tools, we first examined the classification of articles in our dataset according to the WOS categories. The most represented science categories recording more than 15 articles are presented in . It shows how research on gender and heritage is addressed by various WOS categories within social sciences and humanities, from history to women’s studies and from sociology to educational research, to name just a few of the most populated. Studies on gender and heritage are particularly popular within the category Hospitality, Leisure, Sport, Tourism, which includes diverse surveys on visitors’ experiences at cultural heritage sites, while addressing, for instance, men’s and women’s divergent emotional engagement with the heritage tourism (Novoa Citation2021), indigenous women’s participation in the revitalisation of tourism through their commodified image attracting tourists’ gaze (Sheedy Citation2022), and women’s empowerment through cultural tourism (Su et al. Citation2023).

Table 1. Top 15 WOS categories to which the articles on gender and heritage are ascribed.

Reflecting the diversity of the WOS categories, the articles in our dataset are published in 328 different journals covering a broad range of fields. The journal that has published the most articles in our dataset, altogether 11, is the International Journal of Heritage Studies which draws on the critical approach that ‘encourages debate over the nature and meaning of heritage as well as its links to memory, identities and place’ (IJHS International Journal of Heritage Studies Citation2022). Considering the critical emphasis of the journal, 11 articles can be perceived as a small number. The second and third most common journals, with 10 and 6 articles, are Sustainability and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism. Besides heritage studies and tourism studies, the dataset includes plenty of articles published in journals focusing on cultural studies, educational research, history, and women and gender studies.

Regarding the language of these sampled articles, the majority is published in English (85.0%), followed by Spanish (8.7%) and French (2.1%), while very few articles are published in other languages (e.g. Portuguese, German, Italian, Catalan, Hungarian or Russian). All these non-English articles include a title, keywords, and abstract in English. In general, most journals indexed in WOS are in English. Non-English literature dealing with gender and heritage might be better represented here if we had included in our study other, for instance national, databases.

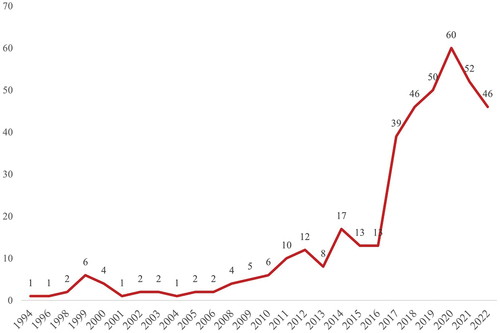

Besides language, another relevant criterion is the publication year. The vast majority of the sampled articles (90%) in our dataset are written after 2010. This growth in literature might be a result of an increase in scholars’ awareness that gender structures cultural heritage production, recognition and consumption, combined with a growing tendency to index journals of social sciences and humanities in the WOS database. This steady increase in the publication of articles dealing with gender and heritage in WOS is easily captured from that shows a peak in 2020 at 60 articles (14.1% of the sample). The number of articles in 2022 is relatively smaller but this difference might be partly due to the fact that the data was retrieved from WOS in October, so articles indexed in the last two months of 2022 are not included. Moreover, the figure excludes 18 articles in our dataset that the journals shared before official publication in 2021 and 2022 as ‘early access’ on their website.

The analysis of the affiliation of the authors in the dataset indicates how the research on gender and heritage in WOS is dominated by Western scholars (). The top ten most productive countries include only two non-Western ones, namely China and South Africa. However, the topic has been explored in other developing economic powers, such as India and Brazil, that rank 11th and 14th on our productivity list. Despite Western dominance, research on gender and heritage can be perceived as a global topic covering all continents. The corresponding authors in our dataset are affiliated altogether to 62 countries.

Table 2. Top countries producing scholarly articles on gender and heritage.

Similarly, the 12 most productive universities in our dataset are located mainly in Western countries, particularly in Western Europe with few in the US and South Africa ().

Table 3. Most productive institutions publishing articles on gender and heritage.

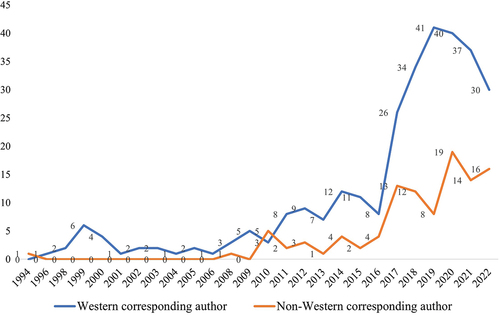

Scholars in Western countries have explored topics on gender and heritage since the 1990s but during the past decade such studies have been produced more globally (). In our dataset, 72.4% of the corresponding authors are located in Western countries. However, both Western and non-Western countries have a similar increasing tendency for such articles in WOS – strengthened in both cases after 2016.

Figure 2. The evolution of articles on gender and heritage by Western and non-Western corresponding authors.

The sampled publications have a very uneven impact in terms of the number of citations they gathered. A large portion of the articles (42.9%) has received no citation, while only 5.9% of the most cited articles have collected at least 30 citations. The most impactful are articles that usually fall within the WOS category of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport, Tourism and Food science (). These articles have been written by a variable number of authors (from one to 12) and are rather recent, the earliest being published in 2009 and the most recent in 2018. These articles approach heritage as a leisure activity or tourist destination and perceive gender as a meaningful variable in the reception or engagement with heritage activities or sites. Two of the most cited studies focus on the consumption and perceptions of local or traditional food. The studies do not seek to scrutinise more deeply the gendered practices in heritage or take a critical stand on the gender system.

Table 4. The five most cited articles on gender and heritage.

The frequency analysis of the number of authors per article indicates that half (50.4%) are single-authored articles. The maximum number of authors is 12, while the average number of authors per article is 2.1 with a standard deviation of 1.636. With respect to the authors’ gender, most of the articles are authored by female scholars exclusively (52.8%), followed by male and female authorship (27.5%), while male-only authorship represents only 19.7% in the dataset. This result suggests that in the context of heritage gender studies may still be perceived as a ‘women’s issue’. Of the sampled articles, 53% explore both male and female genders, while 41.8% focus on women/femininity and only 4.9% on men/masculinity.

The crosstabulation of gender in authorship and focus () reveals that a large share of articles focusing on women and/or femininity are authored by exclusively female scholars (56.6%). Likewise, male scholars are more likely (38.1%) to focus on men and masculinity. Articles by multiple authors, men and women, tend to focus more on research topics that engage with differences between men and women in diverse heritage practices and the reception of heritage. These articles did not commonly adopt a critical, emancipatory, feminist or queer approach. In these articles, the authors often consider men and women as binary statistical categories rather than gender as a critical analytical tool to explain gendered behaviours or attitudes regarding heritage production, conservation or consumption. A chi-square test was computed to determine whether the gender focus of the study (male, female or more than one gender) is dependent on the gender authorship pattern (male, female or more than one gender) of the articles. The results indicate a significant association, χ2 (4) = 49.261, p < .001, while the contingency coefficient (r) =.322 suggests a moderate effect size of the authorship pattern on the study’s gender focus.

Table 5. Gender focus of the articles on gender and heritage by authorship pattern.

Upon recoding the number of authors variable from continuous into a categorical variable with three categories (one author, two co-authors, or three or more co-authors), we explored whether the number of authors affects the choice of gender focus in the articles (). We found a significant association, χ2 (4) = 50.233, p < .001, while the contingency coefficient (r) =.324 suggests a moderate effect of the number of authors of the article on the gender focus of the study. Single-authored studies deal significantly more with women and/or femininity. This might be a mediated effect of authors’ gender since most studies with single authors are conducted by women. Out of 214 articles with one author, 157 (73.4%) are authored by women. Articles that have three or more authors are more likely to engage with male and female genders than focusing either on women/femininity or men/masculinity.

Table 6. Gender focus of the articles on gender and heritage depending on the number of authors.

The analysis of the articles’ author-provided keywords verifies our result ( women-focused keywords are more common in articles only authored by women and male-focused in articles only authored by men, respectively. Moreover, female authors’ keywords more often emphasise a feminist approach.

Table 7. Most frequent words (with stemming and excluding common words) included in the lists of keywords by authors’ gender.

In 87.6% of the articles, the geographical focus of their empirical analysis is mentioned in the abstract. The geographical coverage of the articles extends to all continents, but the frequency analysis underlines the Eurocentrism of research on gender and heritage. The largest proportion of all coded articles focus on empirical cases in Europe (40.8%), followed by articles exploring cases in Asia (27.2%), Africa (9.3%), Latin America (9.1%), North America (8.8%) and Australia & New Zealand (2.9%). Of all coded articles, 52.5% deal with cases in Western countries and 45.6% in non-Western countries, respectively. Only 1.9% of the articles include empirical cases from two or more continents. Female authors have written over 50% of the articles in all coded continent categories, except in studies of Asian cases. Of these, women still authored most of the articles (45.5%) followed by male and female author groups (37.6%). There are no statistically significant differences between female, male, and male and female gender authorship regarding the geographical focus of the studies.

National, ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities are dealt with in 18.7% of the sampled articles indicating that the scholars exploring gender and heritage simultaneously contribute to the knowledge of various minoritized heritages, traditions, and identities. In addition, a small number of articles (12) engage with the influence of the colonial past on heritage communities and preservation discussing race and past or historical or current racism. All these articles indicate scholars’ intersectional interest that acknowledges factors of (dis)advantage or (in)equality based on gender, ethnicity, indigenousness, class or sexuality (for articles taking an explicit intersectional approach see e.g. Grahn Citation2011; Graves and Dubrow Citation2019; Novoa Citation2021; Spencer-Wood Citation2021; Åse and Wendt Citation2022). Such an approach is characteristic for third-wave feminist thinking (Carastathis Citation2016; Ciurria Citation2020) and feminist scholarship during the past few decades. Women authors have written 59.3% of the articles dealing with national, ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or colonial topics. There are no statistically significant differences between gender authorship patterns in exploring such topics.

Close reading of LGBTQI articles

Although feminist scholarship has long emphasised a non-binary approach to gender and criticised heteronormativity, our study indicates how research focusing on LGBTQI groups and identities remains marginal within the literature on gender and heritage. Very few articles (13) in our dataset deal with LGBTQI minorities and/or take a queer approach. Most of them are centred on barriers to full LGBTQI participation in heritage practices in public space. Few scholars bring up examples of the celebration of LGBTQI identities by mapping, for instance, monuments to LGBTQI figures and communities (Orangias, Simms, and French Citation2018) or the expressions of queer identities through heritage traditions (Vasquez Toral Citation2020). These 13 studies are conducted in Europe (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK), the US, and Australia. In this section, we close read the sub-sample of 13 articles to explore more how they address power hierarchies embedded in the binary gender system and heritage in different cultural contexts and how the inequalities drawing on such hierarchies are questioned or deconstructed.

Several studies in our sub-sample focus on ‘the spatial location of historic homosexuality’ (Oram Citation2011, 195). Such practice continues Western LGBTQI history writing, that increased in the 1980s and 1990s, and located historical LGBTQI figures and events in concrete places. In addition, many of the studies in our sub-sample emphasise LGBTQI communities’ identity building through historical narratives, heritage sites, and intangible traditions. The articles show how fostering LGBTQI heritage, and community and identity building drawing on such heritage, faces challenges: LGBTQI histories and narratives are often silenced or removed from museums or institutionalised heritage sites.

The two earliest articles in our sub-sample, written by Oram (Citation2011, Citation2012), explore two English historic houses as homes of women who have become icons of lesbian history, namely Vita Sackville-West (1892–1962) and Anne Lister (1791–1840). The first article highlights visitors’ ‘queer pilgrimage’ to these historical houses as a way to ‘search for sexual parallels within a less troubled past, especially when such validation is not available in a heteronormative or homophobic society’ (Oram Citation2011, 193). The article underlines the agency of LGBTQI visitors in creating ‘an alternative history of sexuality and desire by calling up the ghosts of the past’ in an environment in which queer histories have been ignored or suppressed beneath dominant narratives of class, national identity, and the heteronormative family (Oram Citation2011, 193, 195–196). The second article focuses on the ways the heritage industry narrates the life stories of women with unconventional romantic relationships in conventionalised ways so as to fit in the normative social expectation of family as heterosexual marital partnership and its ensuing offspring, rather than the historic house owners’ celibacy, same-sex love affairs or sibling-based households (Oram Citation2012). A concrete example of such conventionalising curatorial work at one of these houses, Sissinghurst, is the concealment of details referring to the intimate life of their famous queer residents, such as the separate bedrooms of Vita Sackville-West and her husband Harold Nicolson (1886–1968) who both had homosexual partners, while sharing a passion for gardening resulting in a famous Sissinghurst Garden (Oram Citation2012).

Orangias, Simms, and French (Citation2018) continue to explore space by studying 46 ‘queer monuments’ inaugurated between 1984 and 2018 worldwide. By the term, they refer to ‘a heritage site that is officially dedicated to gender and sexual minorities, including trans, lesbian, bisexual, gay, queer, intersex, asexual, and two-spirit communities, among others’ (Orangias, Simms, and French Citation2018, 706). The article underlines how setting up queer monuments and commemorating queer history publicly challenges cultural, sexuality, and gender norms and legitimises the political movement for gender and sexual minority rights. The article identifies three key functions of queer monuments: to signal the existence of oppressed sexual and gender minorities and to reduce their stigma in public space; to educate people towards being more inclusive and tolerant of these minorities; and to enhance advocacy and political debates for improving equality, rights and public representation of these minorities (Orangias, Simms, and French Citation2018, 709).

In our sub-sample, many of the articles discuss the history of LGBTQI communities in relation to power relations in the private sphere and public space. Farges (Citation2020) explores public and private spaces where homosexuals could find ways to express their gender identity and sexual orientation within the totalitarian regime of the German Democratic Republic where the secret police, the Stasi, undertook continuous surveillance of their private lives and limited their opportunities for social and political participation. The article underscores discrimination and challenges faced by homosexuals but also the emancipatory contribution of the Protestant church which facilitated the setup of 20 working groups between 1982–1990 promoting homosexual liberation, for instance, through improving their access to housing and commemorating homosexual victims of Nazism.

Although inequality and power hierarchies based on intersecting categories of difference are discussed in all articles in our sub-sample, only two of them take an explicit intersectional approach to LGBTQI minorities and heritage. Spencer-Wood (Citation2021) discusses how activist archaeology advocates for social justice in commemorating places and intersectional identities associated with individual or collective improvement in the life conditions of marginalised groups. She calls for heritage practices that include muted minorities that have been excluded from historic sites and landscapes that predominantly celebrate elite white cisgender heterosexual men. Building on two projects in Boston (i.e. Boston Freedom Trail and Black Heritage Trail), the author critically interrogates ‘the intersecting oppressive power structures of imperial colonialism, classism, racism, androcentrism, and heteropatriarchy’ (Spencer-Wood Citation2021, 208) that accounted for the symbolic violence reified in the ways the elitist selection operated in the decision-making of stakeholders responsible for the inclusion of monuments, sites, and their biased narratives praising some identities while deliberating muting and erasing others like the community who organised protests and the annual Gay Pride in Boston from 1971 onwards. Although the article is rich in historical facts illustrating women’s and ethnic minorities’ social activism, queer movements are marginal to the analysis. Similarly, Graves and Dubrow (Citation2019) address the lack of equity and diversity in the cultural management policies and resources of agencies in charge of listing the official heritage sites. These institutional agencies do not reflect the histories of LGBTQI and other minorities and their multi-layered identities. Based on the exploration of heritage in San Francisco, which has a rich history of overlapping and conflicting LGBTQI narratives and sites, the authors stress the value of intersectionality for developing policies and practices of heritage with multi-layered meanings.

Three articles in our sub-sample explore gender diversity in intangible cultural heritage and practices drawing on folklore. The ethnographic work by Vasquez Toral (Citation2020) documents the value of queer epistemology through the study of a Bolivian patron-saint fiesta, La Fiesta del Gran Poder, recognised by UNESCO since 2019 as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In the fiesta, Waphuri dancers, traditionally performed by cisgender men, are increasingly taken over by queer men and trans women reworking queer aesthetic elements to invest Bolivian nationalist folklore and its underlying Catholic values and heteronormativity with new LGBTQI political activism in Bolivia. In a similar vein, Strahilov (Citation2021) explores the tenth Sofia Pride in 2017 as well as other Bulgarian qualitative data collected between 2018 and 2021. The study illustrates the popularisation of reinvented mumming that involves queer aesthetic elements to carry over LGBTQI causes in a profoundly illiberal politics. Queer epistemology is also discussed by Gray, Reimers, and Bengtsson (Citation2021, 177) who use the suggestive metaphor of the ‘boy in a dress’ to explore how such a figure ‘is deployed as a “tipping point” between the tolerance and intolerance of gender diversity and racialised minorities’ within Swedish and Australian national contexts. The Australian case study draws on a television ad campaign against marriage equality, while the Swedish case draws on a commercial picture for Lucia festival. In both cases, the focus is on a boy wearing a dress – a racialised boy in the Lucia commercial – and the conservative populist debates that the cases triggered. All three articles underline how ‘the power of cisgender normativity intersects with notions about the nation within public consciousness’ (Gray, Reimers, and Bengtsson Citation2021, 176).

The remaining four articles focus on artists and authors and how their creative work challenges the gender binary and sexual conformity in varying contexts and as a part of cultural heritage of an ethnic or local community. Walters (Citation2019) documents the biography and artistic career of Navajo painter Rudolph Carl Gorman (1931–2005) who blossomed in his adopted city of San Francisco (1955–1968) during its Renaissance of the queer liberation movement. The city hosted queer and migrant artists to challenge heteronormative practices and institutions, and safe locations (e.g. gay bars, queer neighbourhoods and political associations) to perform their non-normative gender and sexual identities. Through his flamboyant paintings expressing both powerful Navajo women and homoeroticism, Gorman challenged the society’s dominant judgement of supposedly inferior Native art. Ibarraran-Bigalondo (Citation2018) analyses Felicia Luna Lemus’s (Citation2007) Like Son, a novel published in 2007 epitomising the fractured destinies of the politically silenced and socially marginalised LGBTQI Chicano/as, namely Americans of Mexican heritage whose identities transgress the gender binary. Through the analysis of the novel’s transgender protagonist who changes name from the Spanish feminine name Francisca to the Anglo masculine name Frank, the article provides a nuanced discussion of the quest of gender and ethnic identities, social recognition of and reconciliation between them within a Chicano community. Also, Loth (Citation2017) draws on the analysis of literary agency, the negotiation of gender and sexual identity and gender crossing in a specific ethnic context – in colonial North Africa. Loth focuses on French writer-traveller women in Algeria, namely Isabelle Eberhardt (1877–1904), a legendary transgressive, cross-dressing female explorer, and Henriette Celarié (1872–1958) who followed her footsteps and played a crucial role in crystallising Eberhardt’s status in the travel genre. The article underlines the ambiguous intersection of gender and ethnicity performed, for instance, by clothing. Wearing traditional men’s ethnic costume enabled Eberhardt to travel alone in Algeria, a disguise that has become enigmatic in her legend. While Celarié admired Eberhardt’s agency, in her own works ‘episodes of cultural cross-dress in which Algerians adopt French clothing are, for reasons of anxiety and narcissism, sites of violently pejorative representations of colonised peoples’ (Loth Citation2017, 84). Clothing and gender conformity are also explored by Brajato and Dhoest (Citation2020) who study the Antwerp fashion scene as a local cultural heritage inspiring young designers today. The article focuses on the creative resistance of renowned Belgian fashion designer Walter Van Beirendonck (b. 1957) in his menswear collections addressing queer sexuality and non-binary gender and to challenge modern hegemonic ideals of masculinity as typified by the bourgeois normativity expressed and performed through the dominant fashion in menswear.

Discussion and conclusions

Our search for WOS-indexed articles on gender and heritage yielded a broad dataset. Gender is addressed in varying ways in social sciences and humanities scholarship ranging from a normative binary statistical category to ambivalent performative queer identity. Critical approaches to gender in heritage contexts and gendering as a practice in heritage are, however, rare. Although critical heritage scholars have recognised the central role of gender for power dynamics in heritage (e.g. Smith Citation2008; Colella Citation2018), research that takes critical analysis of gender more seriously is still needed. Our study underlines the common shortcoming of research on heritage and gender: both are often taken as uncritical terms, ignoring their inherent power structures. This generates scholarship that draws on, cements, and transfers normative understandings of heritage and gender. As a result, scholars can ‘reveal alternative histories’ or expose ‘hidden stories’ of people and their heritages that do not fit into gender norms.

With our quantitative analysis of 427 articles, we sought to respond to Colella’s (Citation2018) call for quantitative research exposing gender biases in the field of heritage. We found that gender and heritage is a rather new focus in scholarship with publication volume increasing after 2016. This may reflect the recent development of indexation of social sciences and humanities journals in WOS. Based on authors’ affiliation and the geographical focus in their empirical analyses, the studies can be perceived as Western dominated or even Eurocentric. The scholarship could benefit from cross-continental empirical studies, which were extremely rare in our data.

Our results indicate how research on gender and heritage is typically authored by lone woman scholars focusing on cis women, femininity, and/or feminism. Thus, in the context of heritage gender is still perceived as a ‘women’s issue’. Articles with multiple authors of different genders typically approach gender as a normative binary category, particularly in the context of reception studies, while male-authored articles more typically deal with cis men and masculinity. This may explain why heritage scholarship often excludes gender and sexual minorities and reproduces conservative and conformist notions of heritage and gender: scholars are not asking such questions because their own gender identities are not implicated. Limited evidence of gender diversity among the published heritage researchers impacts research into gender and heritage. Our results indicate how research on gender and heritage relatively often acknowledges the intersection of gender with minority nationality, ethnicity, religion or language. Nevertheless, this intersectional approach rarely included LGBTQI communities.

Despite the usefulness of the quantitative study in our meta-synthesis, we identified some limitations of the method. These limitations drew on the information provided by the articles’ titles, keywords and abstracts. We were not able to code 427 full articles but trusted that the authors had included in their titles, keywords and abstracts key information of the gender, minority and geographical focus of their research, though this may not necessarily be the case. Moreover, the authors’ gender was coded based on their names. This meant that we were not able to identify trans, non-binary, or intersex authors. Hence, we acknowledge that our study contributes to the construction and reinforcement of a gender normative binary research ecology. As our article focuses on WOS-indexed articles, a lot of important heritage work, documentation, and thinking by marginalised gender-diverse communities fall outside the scope of our study, reinforcing their marginalisation.

Informed by the awareness of historic erasure, many Western LGBTQI communities are currently actively documenting their heritage practices, which is likely to nurture heritage scholarship in the future. Close reading the articles in our LGBTQI sub-sample indicated, however, the thinness of current research focusing on gender and sexual minorities and their heritage. This underlines how heritage is perceived not only as a ‘women’s issue’ but as a cis-gendered issue. The articles show how scholars of LGBTQI history seek to fill gaps that have remained unexplored. Such history writing needs a more global perspective. Our study indicates how the research on LGBTQI communities and heritage is profoundly Western-centred, reflecting the geopolitical history of the LGBTQI liberation movement. The explored studies typically drew on the critical stand of the second wave feminist scholarship underlining the performative nature of gender and sexuality and the normative power of the binary gender system and heteronormativity that LGBTQI identities and agencies challenge. Moreover, the studies recognised the interdependence of gender and sexual identities with other categories of difference and how individuals are exposed to overlapping forms of discrimination and marginalisation. Intersectional feminism, often identified as its third wave, drew to the discussion the links between binary understandings of gender, heteronormativity, and nationalism (Gray, Reimers, and Bengtsson Citation2021). Authors of our subsampled articles had different approaches to the concept of queer. For most of the authors, it was an identity category within a broader category of LGBTQI, while some had a more theoretical approach to queer as a deliberate agency to challenge, oppose, or deconstruct the gender binary and heteronormativity (Oram Citation2011; Strahilov Citation2021).

Although the articles in our sub-sample critically analysed and queered narratives, events and sites dealing with LGBTQI minorities and their participation in heritage, these studies lacked the critical analysis of the notion of heritage and the use of power in heritagization processes. The articles rarely discussed the normative structures, such as the practices of professional valorisation, officialisation and institutionalisation, that are central for the idea of heritage. ‘Making’ cultural heritage, including LGBTQI heritage, is always about the use of power. While the articles broadly questioned the binary gender system and heteronormativity, they rarely challenged the concept of heritage.

This study underlines the need for a critical, intersectional approach to the concept of heritage. This includes decolonisation and questioning gender normativity within the heritage studies and the heritage sector at large. Researchers into heritage and gender could do much more to address sexuality and gender diversity. We encourage scholars to scrutinise how (explicitly or implicitly) gender normativity is being constructed, reinforced, and transmitted in heritage research. Moreover, scholars may consider how heritage research could be more multivoiced and inclusive and ask themselves who has the responsibility – and the power – to develop heritage research towards such goals.

Acknowledgements

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or granting authority. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. We want to thank our anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions for improving our manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tuuli Lähdesmäki

Tuuli Lähdesmäki (art history; sociology), is Associate Professor in Art History at the Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies of the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She has the title of Docent in Art History at the University of Jyväskylä, in Area and Cultural Studies at the University of Helsinki, and in Critical Heritage Studies at the University of Turku, Finland. Lähdesmäki is currently leading the project on EU Heritage Diplomacy and the Dynamics of Inter-Heritage Dialogue (HERIDI), funded by the Academy of Finland. Moreover, she is a partner in the project on Establishing a Laboratory of Cultural Heritage in Central Romania (ELABCHROM), funded by the EU’s Horizon Europe Programme. She has recently co-edited a special issue entitled Heritage Diplomacy: Policy, Praxis and Power, published in the International Journal of Cultural Policy (2023). ORCID: 0000-0002-5166-489X

Ionela Vlase

Ionela Vlase is Associate Professor in Sociology Department of the Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania. She has the title of Docent in Sociology at the University of Bucharest. Her main research interests concern gender, sex work, migration, and social inequalities. She is the author of articles published in academic journals like Gender, Place and Culture, Current Sociology, European Societies, European Journal of Women’s Studies, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, and Journal of Sex Research among others. ORCID: 0000-0002-5117-3783

Notes

1. This variable is based on the authors’ names and thus draws on the gender binary in naming practices. The variable does not seek to indicate how the authors define their gender identity. Based on names, all authors were coded either male or female. We acknowledge that this coding practice provides only limited information on the authors, ignoring, for instance, whether they are cis or transgendered. The data do not enable us to identify trans, non-binary, or intersex authors.

2. This variable includes cis, trans and intersex genders. The articles predominantly explored cis women and men.

References

- Åse, C., and M. Wendt. 2022. “Gender, Memories, and National Security: The Making of a Cold War Military Heritage.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 24 (2): 221–242. doi:10.1080/14616742.2021.1920844.

- Brajato, N., and A. Dhoest. 2020. “Practices of Resistance: The Antwerp Fashion Scene and Walter Van Beirendonck’s Subversion of Masculinity.” Critical Studies in Men’s Fashion 7 (1–2): 51–72. doi:10.1386/csmf_00017_1.

- Carastathis, A. 2016. Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1fzhfz8.

- Ciurria, M. 2020. An Intersectional Feminist Theory of Moral Responsibility. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429327117.

- Colella, S. 2018. “‘not a Mere Tangential Outbreak’: Gender, Feminism and Cultural Heritage.” Il Capitale Culturale 18 (1): 251–275.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Gender Equality: What Does Cultural Heritage Got to Do with It? Strategy 21 Factsheets. Accessed 22 October 2022. https://rm.coe.int/strategy-21-factsheet-gender-equality-what-does-cultural-heritage-got-/168093c03a

- Dieck, M. C. T., and T. Jung. 2018. “A Theoretical Model of Mobile Augmented Reality Acceptance in Urban Heritage Tourism.” Current Issues in Tourism 21 (2): 154–175.

- Farges, P. 2020. “Out in the East. Contribution à une histoire des homosexualités en Allemagne en contexte post-dictatorial.” Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez: Genre, sexualités et démocratie 50 (1): 189–209. doi:10.4000/mcv.12514.

- Grahn, W. 2011. “Intersectionality and the Construction of Cultural Heritage Management.” Archaeologies 7: 222–250. doi:10.1007/s11759-011-9164-x.

- Graves, D., and G. Dubrow. 2019. “Taking Intersectionality Seriously: Learning from LGBTQ Heritage Initiatives for Historic Preservation.” The Public Historian 41 (2): 290–316. doi:10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.290.

- Gray, E., E. Reimers, and J. Bengtsson. 2021. “The Boy in a Dress: A Spectre for Our Times.” Sexualities 24 (1–2): 176–190. doi:10.1177/1363460720904636.

- Guerrero, L., A. Claret, W. Verbeke, G. Enderli, S. Zakowska-Biemans, F. Vanhonacker, S. Issanchou, et al. 2010. “Perception of Traditional Food Products in Six European Regions Using Free Word Association.” Food Quality and Preference 21 (2): 225–233.

- Hall, S. 1996. “Introduction: Who Needs ‘Identity’?” In Questions of Cultural Identity, edited by S. Hall and P. du Gay, 1–17. London: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781446221907.n1.

- Hall, S. 2017. The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, Nation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/9780674982260.

- Harrison, R. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. New York: Routledge.

- Harrison, R. 2018. “On Heritage Ontologies: Rethinking the Material Worlds of Heritage.” Anthropological Quarterly 91 (4): 1365–1384. doi:10.1353/anq.2018.0068.

- Hoon, C. 2013. “Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Case Studies: An Approach to Theory Building.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (4): 522–556. doi:10.1177/1094428113484969.

- Ibarraran-Bigalondo, A. 2018. “The Thin Frontera Between Visibility and Invisibility: Felicia Luna Lemus’s Like Son.” Atlantis 40 (1): 175–191. doi:10.28914/Atlantis-2018-40.1.09.

- IJHS (International Journal of Heritage Studies). 2022. Aims and Scope. Accessed 22 October 2022. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?show=aimsScope&journalCode=rjhs20

- Kim, Y. G., A. Eves, and C. Scarles. 2009. “Building a Model of Local Food Consumption on Trips and Holidays: A Grounded Theory Approach.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (3): 423–431.

- Lähdesmäki, T., Y. Zhu, and S. Thomas. 2019. “Introduction: Heritage and Scale.” In Politics of Scale: New Directions in Critical Heritage Studies, edited by T. Lähdesmäki, S. Thomas, and Y. Zhu, 1–18. New York: Berghahn Books. doi:10.2307/j.ctv12pnscx.5.

- Lemus, F. L. 2007. Like Son. New York: Akashic Books.

- Levy, J. 2013. “Gender, Feminism, and Heritage.” In Heritage in the Context of Globalization: Europe and the Americas, edited by P. Bihel and C. Prescott, 85–94. London: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6077-0_11.

- Loth, L. 2017. “Writing and Traveling in Colonial Algeria After Isabelle Eberhardt: Henriette Celarié’s French (Cross) Dressing.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 36 (1): 75–98. doi:10.1353/tsw.2017.0018.

- McCall, L. 2005. “The Complexity of Intersectionality.” Signs 30 (3): 1771–1800. doi:10.1086/426800.

- Muler Gonzalez, V., L. Coromina, and N. Gali. 2018. “Overturism: Residents' Perceptions of Tourism Impact as an Indicator of Resident Social Carrying Capacity - Case Study of a Spanish Heritage Town.” Tourism Review 73 (3): 277–296.

- Novoa, M. 2021. “Gendered Nostalgia: Grassroots Heritage Tourism and (De)industrialization in Lota, Chile.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 18 (3): 365–383. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2020.1867561. Epub ahead of print 13 January 2021.

- Oram, A. 2011. “Going on an Outing: The Historic House and Queer Public History.” Rethinking History 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1080/13642529.2011.564816.

- Oram, A. 2012. “Sexuality in Heterotopia: Time, Space and Love Between Women in the Historic House.” Women’s History Review 21 (4): 533–551. doi:10.1080/09612025.2012.658178.

- Orangias, J., J. Simms, and S. French. 2018. “The Cultural Functions and Social Potential of Queer Monuments: A Preliminary Inventory and Analysis.” Journal of Homosexuality 65 (6): 705–726. doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1364106.

- Reading, A. 2015. “Making Feminist Heritage Work: Gender and Heritage.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by E. Waterton and S. Watson, 397–413. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137293565_25.

- Sheedy, C. 2022. “Using Commodified Representations to ‘Perform’ and ‘Fashion’ Cultural Heritage Among Yucatec Maya Women (Mexico).” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 20 (1–2): 115–130. doi:10.1080/14766825.2021.1966023.

- Shields, S. A. 2008. “Gender: An Intersectionality Perspective.” Sex Roles 59: 301–311. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203602263.

- Smith, L. 2008. “Heritage, Gender and Identity.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, edited by B. Graham and P. Howard, 159–178. Aldershot: Ashgate. doi:10.4324/9781315613031-9.

- SoPHIA. 2020. Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment. Review of Research Literature, Policy Programmes and (Good and Bad) Practices. Accessed 5 September 2022. https://sophiaplatform.eu/uploads/sophiaplatform-eu/2020/10/21/a4309565be807bb53b11b7ad4045f370.pdf

- Spencer-Wood, S. M. 2021. “Creating a More Inclusive Boston Freedom Trail and Black Heritage Trail: An Intersectional Approach to Empowering Social Justice and Equality.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 25: 207–271. doi:10.1007/s10761-020-00544-w.

- Strahilov, I. 2021. “National Pride: Negotiating Heritage, Gender, and Belonging in Times of Illiberal Ethnonationalism in Bulgaria.” Intersections East European Journal of Society and Politics 7 (4): 13–31. doi:10.17356/ieejsp.v7i4.826.

- Su, X., X. Li, and Y. Kang. 2019. “A Bibliometric Analysis of Research on Intangible Cultural Heritage Using CiteSpace.” SAGE Open 9 (2): 1–18. doi:10.1177/2158244019840119.

- Su, M. M., G. Wall, J. Ma, M. Notarianni, and S. Wang. 2023. “Empowerment of Women Through Cultural Tourism: Perspectives of Hui Minority Embroiderers in Ningxia, China.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 31 (2): 307–328. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1841217.

- Tong, R. 2009. Feminist Thought: A More Comprehensive Introduction. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- UNESCO. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2003a. Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2003b. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

- Vasquez Toral, E. 2020. “Queer Fiesta. Hybridity, Drag and Performance in Bolivian Folklore.” Performance Research 25 (4): 98–106. doi:10.1080/13528165.2020.1842602.

- Vlase, I., and T. Lähdesmäki. 2023. “A Bibliometric Analysis of Cultural Heritage Research in the Humanities: The Web of Science as a Tool of Knowledge Management.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10 (84): 1–14. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-01582-5.

- Waitt, G. 2000. “Consuming Heritage: Perceived Historical Authenticity.” Annals of Tourism Research 27 (4): 835–862.

- Walby, S., J. Armstrong, and S. Strid. 2012. “Intersectionality: Multiple Inequalities in Social Theory.” Sociology 46 (2): 224–240. doi:10.1177/0038038511416164.

- Walters, J. B. 2019. “‘So Let Me Paint’. Navajo Artist R.C. Gorman and the Artistic, Native, and Queer Subcultures of San Francisco, California.” Pacific Historical Review 88 (3): 439–467. doi:10.1525/phr.2019.88.3.439.

- Winddance Twine, F., and B. Gardener. 2013. “Introduction.” In Geographies of Privilege, edited by F. W. Twine and B. Gardener, 1–16. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203070833.