ABSTRACT

This case study draws on evidence gathered in a minority setting in north-eastern Italy where Ladin, the heritage language, is central to the construction of past and present narratives of heroism and resistance. The article aims to contribute to the development of new debates within this journal as facilitated by different disciplinary perspectives, and in line with recent discussions about the status of language as heritage, which question the problematic UNESCO definition of language as a vehicle to intangible cultural heritage. Adopting a Linguistic Landscape approach, which focuses on material aspects of language and spatial dimensions of identity-building, the article discusses local micro-narratives of heroism which are in turn encompassed in macro-narratives of major events with global repercussions, such as World War 1. Evidence of the symbiotic relationship between the natural landscape and these events is represented by linguistic resources interacting with the setting to render it a rich example of history being inscribed in geography, and of landscape as monument. The discussion foregrounds the centrality of the heritage language in the performance of heroism, and its role in engendering interconnections between self-perception, aesthetics and ethics.

1. Introduction

This article is based on a case study drawing on evidence gathered in a setting where Ladin, the heritage language (the indigenous language that is minoritised with respect to Italian, the language of the state), articulates consolidated discourses of heroism in its primary components of courage, self-sacrifice and moral integrity. Although hero stories display common cross-cultural features (Campbell Citation2008), they are understood in relation to the social order (e.g. social recognition) and the emotional culture (e.g. patriotism) that they express (Frisk Citation2019). Within the context of the commemorations of the centenary of the end of WW1, the study proposes that the use of the minority language in the public space performs an everyday reconstitution of the self, in relation both to the traumas of the past and to the threat of invisibility of the present. A Romance language spoken in the Alpine valleys of north-eastern Italy, Ladin is a small minority language whose speakers (between 3.5% and 4.5% of the regional population, ca. 30000 people)Footnote1 are located between a Germanophone area and an Italophone area, and the competition from larger linguistic groups can be perceived as constituting a threat to ethnolinguistic survival.

With a focus on the relevance of language acts, and the support of theoretical frameworks that enable the interpretation of heroic narratives, the article aims to contribute to the development of new debates within this journal as facilitated by different disciplinary perspectives (Winter Citation2013), and to expand recent discussions about the status of language as heritage (Eaton and Turin Citation2022), which question the problematic UNESCO definition of language as a vehicle to intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO Citation2003). Rather than considering language as a vehicle (and a mere reflection) of culture, language practices are central for the performative creation of culture (e.g. Butler Citation1997; Blommaert Citation2005). The present discussion is underpinned by an aspiration for language to be not only central to any discursive formations (including heritage discourses, as in Smith Citation2006), but for language to be considered as both tangible and intangible heritage in that the materiality of language artefacts as analysed in this paper provides a tangible infrastructure of verbal heritage. The article seeks to exemplify this claim through the synthesis represented by Linguistic Landscape (LL) studies (see § 3), and in particular through an analysis that points to the interconnections between language practices (currently understood as intangible cultural heritage) and the experience of the local natural landscape (tangible heritage). From this perspective, the discussion responds to calls to transcend the nature/nurture dualism, in order to move away from Western approaches to culture and consider the natural landscape a form of cultural heritage (Harrison and Rose Citation2010; Hou Citation2019) – a lived reality for the community at the centre of this study, and rooted in memory-making processes (Wallis and Harvey Citation2017).

LL centres around semiotic constructions of space and is a relatively recent development within Sociolinguistics, the study of language in society. A distinctly multidisciplinary approach has informed LL academic production in the last 15 years or so and has consolidated a view of space as a dynamic dimension of human experience. Space is not a canvas or a background, and it is not fixed; rather, space is in continuous transformation and contingent on the actions through which it is constructed. Theorisations of geosemiotics (i.e. signs observed in their material emplacement, or discourses in place, as in Scollon and Wong Scollon Citation2003) have put an emphasis on spatialisation practices for the construction of meaning – a primary focus for LL. In this light, writing acts, and more widely semiotic inscriptions, are reassessed as an ordinary, everyday practice where boundaries are blurred, and where the signs’ political valency critiques consolidated language ideologies (e.g. the primacy of the standard/official language) and articulates counter-discourses of language and identity.

In bringing together spatial and linguistic processes of identity making, LL foregrounds the role of verbal and other semiotic inscriptions in the public space in the construction of cultural and social landscapes. In the setting under investigation, the visuality and materiality of LL validate individual language acts as tangible heritage underpinning instances of collective heroism (Sharp Citation2009), and the commodification of historicised discourses of difference and authenticity is transcended through the inherent significance of linguistic and cultural survival for the group. The latter process engenders the merging of the aesthetic dimension of the landscape (the sensorial perception of the world that surrounds us) with the ethical mission (as facilitated by the established shared values) to consolidate the hero as heritage (Marschall Citation2006) – a key component in the performance of local identity.

In terms of the organisation of the article, § 2 contextualises the study; § 3 outlines LL developments, and the methodology employed for data gathering in the given locality and as grounded in LL as a discipline; § 4 is about the singular configuration of local WW1 events, its close interconnections with the natural environment, and the memorialisation practices that have consolidated the heritage dimension of local heroism; § 5 elaborates on the relationship between mythos and logos for the purpose of establishing a link between conceptions of beauty and ethical judgements and actions; and § 6 focuses on the contemporary LL construction of heroism. The Conclusion (§ 7) brings together the different threads of the discussion and foregrounds the production of the hero as heritage at the confluence of past and present narrative, and as inscribed in LL discourses.

2. The context

In the year that marked the centenary of the end of the First World War (WW1), 2018, in Italy as elsewhere events and commemorations were held to reflect on an experience with significant repercussions not just in historical and political terms, but primarily in human terms. This approach reflected a trend that began in the 1990s, when studies on the Great War started analysing in depth the cultural, social and psychological consequences of the conflict (Bizzocchi Citation2014). The Italian WW1 front was in the north-east, along the line that marked the separation between Austria-Hungary and the Italian state. The impact of local warfare on both soldiers and communities was immense, and collective memory was moulded through diverse voices – individual and group stories, military reports, official and unofficial accounts – which all converged to articulate a heroic narrative encompassing the topoi of sacrifice and resilience, and of the struggle for justice, that has consolidated over time. Although this article does not discuss gender dynamics in particular, it is important to note that women are generally overlooked in the local narratives about WW1, which continues to be configured as a male enterprise. Writings about WW1 authored by Italian women have similarly been side-lined and the male soldier-writer has been foregrounded in critical accounts. However, numerous Italian female writers have written about WW1, and not just about personal and domestic repercussions of the horrors of war, but also about their active support on the front, their participation in the political debate about the war and in the construction of heroism (Gragnani Citation2017).

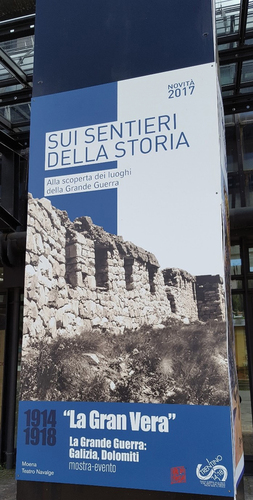

My 2018 fieldwork in Canazei, a town in the Val di Fassa in the Italian Dolomites, gave me the opportunity to observe and take part in some of the numerous commemorative events such as thematic exhibitions (e.g. La Gran Vera, see § 4), guided tours (see the map in § 4) and choir performances by the Alpini regiments, infantry corps who distinguished themselves in combat during WW1. During my stay in the summer of 2018, the heroic narrative, that was an explicit thread of the fabric woven by the memorialising events, strongly emerged from the everyday details of the local environment, and in the interconnections between the natural landscape and human undertakings, with the latter being characterised by linguistic constructions of meaning. The tremendous effort to maintain and revitalise Ladin, the heritage language, within the local linguistic ecology emerged in the performance of ethno-linguistic identity and in its public enactment through LL. This effort shared the characteristics of a heroic enterprise and established lines of continuity with the undisputed exceptional role of the locality in WW1 – a process leading to the reconstitution of the self for the local identity.

In the revisiting and recomposing of memorial accounts, Ladin, the heritage language, was central to the construction of past and present narratives of heroism and resistance (Campbell Citation2008). The centrality of language for identity construction is rooted in lively debates regarding the linguistic classification of Ladin as an independent language dating back to the nineteenth century and consolidating discourses of fragmentation and lack of unity between Ladin-speaking communities (Goebl Citation2020). On the one hand, this was due to the high mountains hindering movement and regular contact between settlements in the valleys, and on the other hand to their being surrounded by larger Germanophone and Italophone groups that threatened their survival by means of assimilation. Italian annexation of Ladin-speaking territories at the end of WW1 was experienced as a danger for ethnolinguistic survival – a sentiment that has inspired a wealth of initiatives for the defence of local identity throughout the twentieth century and that continues today (Palla Citation2020). Evidence of this struggle for visibility was enhanced by the WW1 commemorations providing an opportunity for the significance of local valour and sacrifice to emerge. In the process of historicization of landscapes of conflict, verbal inscriptions were deployed amidst sets of semiotic resources in the performance of difference and in the construction of both material and symbolic statements of singular alterity. The local landscape was interspersed with magnified and monumentalised language that articulated localised micro-narratives of heroism, which were in turn encompassed in macro-narratives of significant global events such as WW1. Evidence of the symbiotic relationship between the natural landscape and these events was discernible in acts that inscribe the heroic self into the intimidatingly majestic (and potentially threatening) surroundings, therefore making this setting a rich example of history being inscribed in geography, and of landscape as monument. The modalities of this symbiotic relationship constantly blurred the boundaries between what is considered to be tangible and intangible heritage, with language artefacts emerging as actors in the public space and acquiring the tridimensionality of embodied experience. In addition, discourses of heroism were underpinned by a moral mission that invites us to reflect on the links between ethics and aesthetics, which I explore in § 5.

In recalling aspects of the hero archetype, I draw from Campbell (Citation2008), a useful compendium of heroic forms and myths as they have been generated in very diverse cultures and spanning millennia. The archetypical solitary hero, however, is revisited to uncover processes that invest the community and foreground the collective efforts for the preservation of vital spaces of living (Ashley and Frank Citation2016). The present case study therefore provides an example of the reversal of collective marginality through the consolidation of heritage from below (Robertson Citation2008; Smith Citation2012).

3. LL studies and methodology

It can be argued that global mobility and the ensuing transformations of the last 30 years or so have brought about increased cultural and linguistic contact, the traces of which are visible in the environments that surround us. Mass tourism and ease of travel, for example, have prompted spatial adaptations of tourist destinations that have included the display of multilingualism, and often of the widespread use of English, to cater for tourists’ needs. Grounded in Sociolinguistics, LL studies have focused on the observation of multilingualism in the public space. This has generated an increasingly sizeable body of research into (predominantly urban) contexts that provide the opportunity to reflect on the role of the numerous verbal inscriptions that surround us. Although the origin of LL can be traced further back (e.g. Rosenbaum et al. Citation1977), Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997) is a much quoted study in the field and inspired projects that initially focused on LL documentation. This was facilitated by technological innovations such as digital cameras and mobile phones, which allow easy gathering and storing of data such as photographs of signs. From an initial emphasis on quantitative surveys that provided snapshots of multilingualism in given areas, the field has diversified to provide a host of qualitative studies that have aimed to provide in-depth LL analyses and that have drawn upon cognate disciplines such as cultural geography, anthropology, urban studies, semiotics etc. in the development of theoretical perspectives.Footnote2 As mentioned above, a seminal study that is central to the development of LL is Scollon and Wong Scollon (Citation2003) about geosemiotics, i.e. signs observed in their material emplacement. LL therefore foregrounds the importance of space as an actor in meaning-making practices, and spatial constructions implicate both verbal inscriptions and wider, non-verbal, semiosis (e.g. that resulting from the human manipulation of the environment in a broad sense). Underpinned by Lefebvrian and Foucauldian understandings of how space is implicated in power relations (Silva and Mota Santos Citation2012), ethnographic perspectives have increasingly enriched the field and supported critical approaches to the study of space. Finally, multimodality (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2001; Kress Citation2010) provides the tools for a comprehensive analysis of the characteristics of signs in place, in that it dissects the multiple components of signs as they are grounded in social context and highlights the interplay between visual (verbal and non-verbal) discourse and the spatial dimensions of culture. For the present study, all these elements will help to understand the production of a heroic narrative and the key role of LL in providing a synthesis between tangible and intangible heritage.

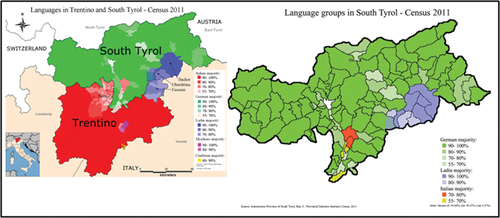

The data for this study were collected in and around Canazei, in the Fassa Valley, in the summer of 2018. The majority of the local inhabitants speak Ladin,Footnote3 a Romance variety spoken in the Alpine valleys in the north-east of Italy that enjoys the status of officially recognised (minority) language by the Italian state. Ladin is not a unified language, and different varieties are in use in the area; however, (an estimated 30,000) Ladin speakers self-identify as part of the same ethnic group (Dell’aquila and Iannàccaro Citation2006; Videsott, Videsott, and Casalicchio Citation2020). The area is at the confluence of different ethnolinguistic cultures, and is squeezed between a much larger Germanophone group in Alto Adige/South Tyrol to the north and Italophone areas to the south and east ().

Figure 1. Distribution of Ladin-speaking areas. Retrieved from https://forum.unilang.org/viewtopic.php?t=38224. Accessed 27 August 2021.

Figure 2. Linguistic distribution in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtyrol. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trentino-Alto_Adige/S%C3%BCdtirol. Accessed 23 March 2023.

The heroic dimension, rooted in memory-making processes, is enhanced by the historical struggles to gain visibility, due to Canazei and the other Ladin-speaking centres currently integrated into the Italian-speaking province of Trento striving to have their ethnic specificity acknowledged. Only in 1976 was the Val di Fassa, the valley encompassing Canazei, recognised as a Ladin area – this was followed by the placing of bilingual signage and toponyms (from 1987) and the declaration of Ladin as co-official with Italian (1994). The change of status of local varieties prompted the introduction of Ladin in nursery and compulsory schools, both as a subject of study and as a medium. A standard grammar of Ladin was published in 2001, followed by a dictionary in 2002 (Dell’aquila Citation2010).

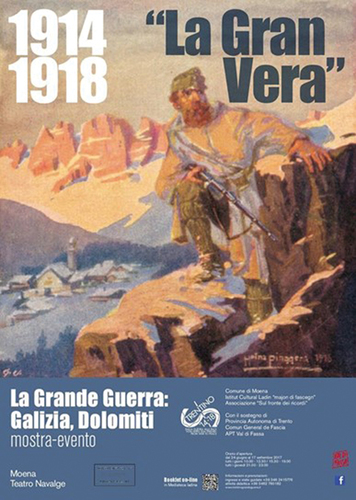

In keeping with LL methodological approaches, during my stay in Canazei I recorded all LL items (all signs displayed in public areas) visible in the main thoroughfare crossing the town (approximately 1 km) and the side streets departing from it. In the small town environment, these were the sites experiencing the regular passing of people exposed to the signs. Out of 249 recorded items, 58 featured Ladin – about a quarter of the total. Ladin featured in bilingual signs together with Italian, in multilingual signs together with Italian, English and German, and autonomously in signs displaying proper nouns (e.g. house names, street name signs and shop signs). Signs not featuring Ladin were primarily in Italian (118), whilst English and German did not appear on any signs autonomously. LL items (by which I mean a framed verbal inscription which was visible to any passer-by) featuring Ladin included municipal material (street signs,Footnote4 recycling bins); commercial signs (tourist and shop signs, restaurant and hotel signs, the local bank); adverts for local events issued by a mix of private and public bodies; and house names as in the examples provided in § 5.Footnote5 The discussion will also refer to additional items displayed in the town’s tourist office, such as maps reproducing war walkscapes and information about initiatives marking the historical anniversary, e.g. thematic exhibitions and events that I participated in. An example of an exhibition is La Gran Vera (It. La Grande Guerra; Eng. The Great War – as in in § 4), that took place in Moena, a nearby town, and that foregrounded the human element of the war and the social upheaval that it generated. A community event was an Alpine choir singing songs from the Great War, some of which in Ladin, and interspersed with brief narratives and poems about life on the Dolomitic front. Memorial itineraries included key heritage sites (see in § 4). Although these activities were aimed at engaging external visitors in a touristic context, they sought to foreground the key role of those who inhabited the area at the time of the Great War and to immortalise the ennoblement of local mountain people through the public recognition of their historical mission. I participated in these activities as a visitor, and had the opportunity to talk to guides and local staff, or ask questions as a member of the audience/group. Consulting informants on aspects of LL was not envisaged and was not done systematically. As both researcher and visitor, however, I am acutely aware of the fact that the way that we go about gathering information for our research, and our own subjectivities, cannot be disentangled from the object of our investigations. This type of reflexivity is an integral part of sociolinguistic approaches to the study of language in society, which is also inspired by an ethos to put marginalised actors at the centre of scholarly work (Heller and McElhinny Citation2017). I do not have any personal connections to the Fassa Valley and my interest in Ladin is that of a researcher who engages with minority languages and whose background in dialectology facilitates the understanding of Romance language varieties and of the worlds that they inhabit. In this particular instance, this research seeks to foreground minority heritage, and to tease out its characteristics as engendered in the given locality and as articulated through LL. The proposal is that this LL case study will contribute to a re-assessment of the separation between tangible and intangible heritage, and demonstrate that language is integral to both dimensions.

4. Merging nurture with nature: history inscribed in geography

The imposing natural landscape of the Dolomites will strike all visitors (). All that the human eye can capture from any vantage point in the area gives an idea of the magnitude of the mountains, limestone peaks stretching above 3,000 m, which form part of the eastern Alps and are interspersed with valleys where people settled in the face of very difficult circumstances. It is in this exceptionally challenging natural environment that local history has been inscribed, forging a symbiotic relationship between the grandiosity of nature and the resilient character of those who inhabit it.

The perception of the unique setting, coupled with a strong sense of cultural and linguistic identity, have moulded the Ladin specificity – something that the locals are strongly aware of and that emerges in scholarly accounts (e.g. Delai and Marcantoni Citation2005). Local pride has been enhanced by newly found confidence in local resources following the economic developments of the last 60 years. The area is a popular destination for both winter and summer holiday makers, and thanks to tourism the region is one of the wealthiest in Italy (Eurostat Citation2019). The diversification of tourism has provided additional opportunities to emphasise the Ladin specificity, and the local merits of actions and events with significant repercussions at both a national and an international level. In particular, the experience of WW1 represents one of the main (if not the main) cornerstones of local memory, and one that has contributed to the creation of a spatio-temporal narrative engendering the heroic dimension that is the focus of this article. The fact that in WW1 the Italian front crossed parts of the Dolomites, and that soldiers in those areas fought at impossible altitudes (Corà Citation2008) and in horrendous climate conditions, is an integral part of this narrative.

Italian participation in the conflict was rooted in the nationalist desire to claim territories that were considered to be Italian culturally and linguistically, and that in 1915, when Italy joined the war, were part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, situated on the other side of the north-eastern border. Ladin-speaking groups lived on both sides of the border and had been a bone of contention between Austria-Hungary and Italy. Even before the war, the tradition of Austrian historiography about Ladins was highly influential in the representation and self-representation of Ladin honesty, loyalty, endurance and reliability (Palla Citation2015, 31–33). This characterisation tended to highlight the similarities with (German-speaking) South-Tyrol in terms of ethos and mentality, and obscure any possible tensions. Conversely, Italian accounts emphasised the Italianness of Ladins, and tales surrounding the heroism of ethnic Italians who lived in Austria-Hungary volunteering to cross the border to fight alongside Italian soldiers in WW1 would subsequently be greatly emphasised by Fascist rhetoric (Thompson Citation2008, 114–115). This claim was usually based on language (Ladin was considered to be an Italian dialect) and relied on the widespread lack of awareness of the specificities of ethnolinguistic fragmentation in the north-eastern border area (populated by people speaking Slavonic, Germanic and Romance varieties), even on the part of leading politicians. At the time, consolidated discourses around the one language-one nation nexus had been appropriated and promoted widely, and even a multi-national empire such as the Austro-Hungarian one recognised the different ethnic groups on the basis of the respective landesüblicke Sprachen, or languages customarily spoken in a given area, with all the problematic consequences of such as assertion in a linguistically fragmented territory (Wallnig Citation2003, 24).

With the resolution of WW1 leading to the political incorporation of border areas into the then Kingdom of Italy, existing allegiances towards the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the sense of identity converged to deepen the internalisation of ethnic diversity which would be safeguarded through mechanisms that span the twentieth century and reach the twenty-first, and would ultimately lead to Ladin gaining visibility (see § 3). The war was therefore crucial for engendering a renewed ethnic conscience that would drive self-determination and guide the demands made to the Italian state to support it. The outcome of the war accelerated this process and, in turn, the war had a significant responsibility for local reconstructions of the past.

As documented by sources, in local memoirs and oral histories there is a constant reference to the mythical and idealised soldier from the north-eastern border (Palla Citation2015, 19–21). Peculiar to the Ladins, in addition, was the representation of the local sense of duty and sacrifice, and the courageous acceptance of the unfolding events. Italian annexation after the war reinforced war memories of Ladins as heroic defenders of the values and traditions of the local community.

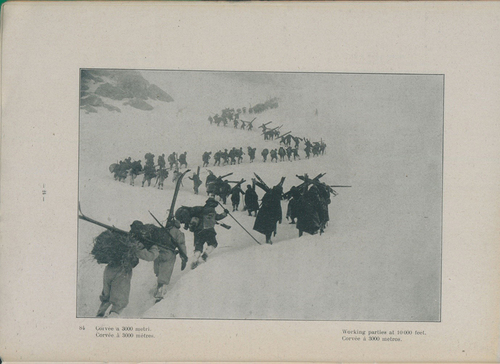

The mythical aspect of the war fought on the Dolomites was established early on in the conflict. From the start it acquired the features of position warfare, fought at very high altitudes and characterised by man-to-man combat that enhanced individual valour and allowed the thorough study of the adversary in the long, icy winters that forced soldiers to endure sustained periods of inactivity (Palla Citation2015, 93).

The reality of the destructive power of war machines (such as the machine gun) and of the massification of death soon replaced the romanticised idea of the noble war characterised by the pre-modern hero fighting for a greater good (Leed Citation1981, 115–150). The environmental conditions of Alpine warfare, however, ensured that the heroic aspects of the vertical war (Leoni Citation2015) emerged in much WW1 literature that celebrated idealistic behaviours and values, such as honour and respect for the adversary, which were reflected in the chivalrous and self-sacrificing spirit of the Alpine soldiers. High altitudes and mountain morphology conferred a different character to warfare – contrary to the massification of death that was under way in lower battlefields, the peculiar terrain allowed the de-anonymisation of the war experience and the emergence of personal stories and individual heroic actions (Corà Citation2008, 648). Sanitised from the traumatic reality of the war smellscape and soundscape, the creation of relevant public iconography was supported by a host of visual representations of heroic deeds in the press, postcards, photographs and documentaries (Isnenghi Citation1989, 130 ff.).

The figure of the Alpine soldier, and of his symbiotic relationship with nature, became legendary also thanks to discourses encouraged by the military establishment, eager to foreground the unshakeable moral qualities, coupled with the physical fitness guaranteed by the healthy and spartan upbringing in a pure environment, that characterised the Alpine fighter – a reassuringly conservative figure when compared to conscripts coming from urban contexts, or other parts of Italy, who had been exposed to political ideas that challenged the status quo (Mondini Citation2008, 10). This myth was canonised by literary production that crystallised the epos of the heroic metamorphosis of humble farming and mountain people (Isnenghi Citation1991), by journalistic reports that substantiated hyperbolic accounts, and by a repertoire of folk songs, still performed by Alpine choirs in both regional and national events, that have nourished the collective memory and imaginary beyond the local dimension.

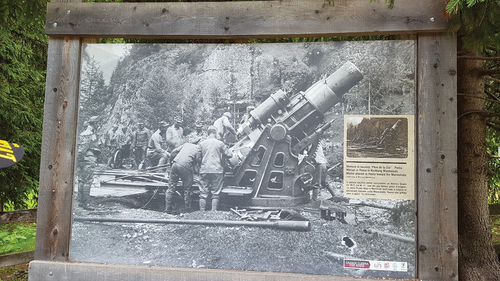

The unimaginable hostility of the mountainous landscape, much of which permanently covered by snow and ice, exalted the soldiers’ titanic efforts to dominate the forces of nature and engage with miracles of engineering to secure routes, galleries, and shelters, in addition to miles and miles of trenches ().

Figure 5. Italian soldiers marching upwards in the snow. Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/mountain-warfare#. Accessed 27 August 2021.

Figure 6. Poster advertising the exhibition ‘The Great War’ (Ladin, Italian). Retrieved from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/eng/Events/1914–1918-La-Gran-Vera-the-Great-War-Galicia-Dolomites. Accessed 9 September 2022.

Figure 7. Memorial and ethnographic itinerary (adapted from Museo sul Territorio, n. d.). Retrieved from https://www.istladin.net/it/museo-sul-territorio. Accessed 9 July 2021.

To maintain the epic metaphor, significant human losses (two thirds of mountain casualties were due to weather conditions, see Gibelli Citation1998, 102) could be interpreted as a result of hubris and of the resistance exercised by the violated mountains. Often hubris characterises the classical hero and is a trigger for action leading to a tragic outcome. The tragic character of the fighting on the Dolomitic front was certainly validated by the sacrifice of significant numbers of people – both on and off the battlefields, but it was also to be seen in the traumatic repercussions on those who survived and for which WW1 proved to be a disjunctive experience (Leed Citation1981) – a watershed between a before and an after, an unbridgeable fracture between those who fought and those who did not. Within Ladin historiography this disjunction would have long-lasting consequences both for collective memory and for the consolidation of an ethnic specificity, in a cathartic process of re-birth. As will be shown below, a contemporary heroic dimension would emerge in the shared spaces of everyday life where human actions belong, and in the routine blending of local natural beauty and human moral mission that have produced a distinctive landscape of cultural heritage (Harrison and Rose Citation2010; Hou Citation2019).

The existence of a grand narrative about WW1 which rests on so many accounts that it would be impossible for any individual to read them all (Gilbert Citation1994) is undisputed. This narrative was reinvigorated through the numerous initiatives carried out to mark 100 years from the end of the war in 2018 – the year in which the data for this article were gathered and that offered the opportunity to observe the multiple occasions for remembering the unique role played by local people, and accomplish the transformation of the hero as heritage. Signs relating to the historical anniversary were, understandably, prominent and could be identified in different locations. In addition to , which was advertised in the tourist office as an exhibition hosted in a nearby town (Moena) and features Ladin in the title (La Gran Vera – The Great War), a host of booklets, leaflets and other visual items constituted the material made available to visitors interested in memorial tourism and for which the area represented a primary memorial site. In keeping with much of the memorialisation effort, and of the concomitant iconography, the poster in exalts the solitary hero perched on a rock ledge and surrounded by a wintry dolomitic landscape.

Activities organised locally included the opportunity to re-trace past war itineraries, paths and walkways, and identify the former sites of trenches and military positions. War itineraries (Museo sul Territorio, n. d.) intersected with ethnographic ‘stations’ on a journey incorporating core signifiers of local identity such as the exhibition on the Great War in Moena (1), the ethnographic museum in Vigo (2), the community dairy farm documenting traditional farming and cheese-making methods (3) and the old sawmill in Penia (4) ().

The black-and-white image in , the reproduction of an original photograph, displays a WW1 mortar which was positioned along what is now a footpath used by tourists taking walks in the mountains surrounding local towns and villages. As the logos of relevant municipalities in the bottom right-hand corner suggest, these reminders of the strategic importance of the locality for the war efforts (right on the border between Italy and Austria-Hungary at the time) were placed along these routes by local authorities as part of the activities commemorating the centenary of the end of WW1 (the logos are preceded by the Italian caption Grande Guerra 100 anni – Great War 100 years). Above the logos, an explanatory text in Italian, Ladin, German and English reports that similar artillery pieces positioned in that area aimed at striking Italian military posts located on the Marmolada – the highest peak of the Dolomites (3,343 m.) situated a few miles away. The contemporary viewer will dwell on the meaning of Italian in this context, as the concerned site is encompassed within the current Italian territory. This detail is in fact part of a wider heroic narrative, and the dramatic black-and-white sign is a reminder of the multiple intersecting conflicts characterising this area in a not-so-distant past – an external, physical conflict bringing destruction and death to a border area with moveable identity, emotional and affective boundaries, where it was not unusual that people belonging to the same ethno-linguistic group would fight each other on opposite sides of the front.

The pervasiveness of these initiatives and their exploitation of material artefacts with war associations for the benefit of memorial tourism expanded and enhanced external perceptions of local heroism. As already evidenced in , the topos of the perilous journey, a key aspect of the hero’s existential parable, was reproduced in the form of war walkscapes along which visitors could re-trace war itineraries () It. Sui sentieri della storia, Eng. On the paths of history).

Figure 9. Example of organised walks (Title at the top ‘On the paths of history’). Retrieved from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/eng/Events/1914–1918-La-Gran-Vera-the-Great-War-Galicia-Dolomites. Accessed 9 September 2022.

The essentially mythical dimension of a distant event not directly experienced by any current visitor is continuously recreated through storytelling and the ritualistic performance of local warscapes. The archaeological positioning of surviving war evidence (e.g. sections of trenches, barracks and military posts) which has endured material transformations over time contributes to conjuring up images of a mythical past and establishing an emotional connection with those who were and are not any longer. Semiotic and linguistic artefacts are heritage items that merge to recompose a narrative that consolidates the heroic dimension of local actors and foregrounds its relevance for the current struggle for (ethno-linguistic) survival. This narrative evidences transitions from/to classical interpretations of mythos and logos, and interconnections between ethics and aesthetics – aspects that are directly involved in the actualisation of the local heroic landscape and in the concomitant construction of the hero as heritage.

The purpose of the next section is to propose a framework that establishes connections between different narration modes, and the aesthetic and ethical underpinnings of heritage discourses in the given context. This will provide the theoretical foundation for an understanding of the local heroic landscape before moving to the analysis of signs in place.

5. Mythos and logos, aesthetics and ethics

In reconstructing the passage from mythical narration to philosophical thought in ancient Greece, Vernant (Citation1980) clarifies that the separation between mythos and logos was due to the different status of the two modes of narration. Oral narration presupposes the gift of eloquence and a performer’s ability to capture the imagination of the audience, to fascinate and enthral them, to persuade them of the metaphysical content of the message. The seductive, persuasive power of the text begins and ends with the oral narration itself, which stands in opposition to the writing act (logos), that uses arguments to convince the reader. Reading activates the reader’s critical judgement – logos as written text is in this sense opposed to mythos as an oral narration, and it fixes the truth through the collective sharing of the facts – the act of writing makes the text available to the community on a permanent basis and, by sharing it, makes it public. LL, therefore, is key to the validation of heroic narratives as articulated through the local language. Even though they are emptied of their metaphysical content and abstract teaching power, in the modern era myths maintain an important function: they reinforce social cohesion through the transmission of values and behaviours, and the consolidation of group norms through the ritualistic regularity and repetition of forms of existence.

Both mythos and logos are the result of acts of creativity – the ability to give shape to something (a narration) that was not there before, and which is inextricably interwoven with the human aesthetic experience. Aesthetics refers to the phenomenon of perception (Greek aisthesis), where the senses are central for the establishment of an interface between us and the world, and it is key to ensuing articulations of beauty. While discussing the relationship between aesthetics and semiotics, Finocchi (Citation2013) highlights that creativity represents the link between the individual feeling and the collective feeling, and it engenders the normalisation of how humans feel the world. Language allows the articulation of the aesthetic experience, and of its adaptation to express unusual or new meanings in relation to situations – what Eco (Citation1984, 50) calls invention. The process of creativity, and its inherent openness to variation and innovation, allows language to facilitate comprehension among its users through an aesthetic disposition that enables interlocutors to share correspondences to decode meaning – to tune in to shared/common feelings, so to speak. The possibility of designating linguistically (through a semiotic system – language) something that is perceived through the senses (aesthetics) implies creativity. Creativity in turn can be seen as the process that engenders the interpenetration between aesthetics and ethics in that it also facilitates the normalisation of a system of values.

The aesthetic experience is closely related to the ethical dimension, and this link is rooted in ancient conceptualisations and verbalisations of the connection (Chiodo Citation2016). An example is the Greek hendiadys kalokagathos - i.e. kalòs kai agathòs, or beautiful and good, a binomial that has been profoundly influential in western cultures together with its direct counterpart – ugly and evil. An English lexicalisation of the concept is encompassed in the word fair, meaning both beautiful and just (Scarry Citation1999). The universality of this axiom can be detected in non-western cultures, too – the Japanese term yoshi subsumes the notions of beauty and good, and so does the Chinese ideogram mĕi (Bodei Citation1995).

The Platonic perspective is representative of ancient approaches to the interconnections between aesthetics and ethics. For Plato beauty is an essence (a Platonic idea that belongs to the superior, non-material world), and as such it is present in the mind and universal. It is also the only essence that human beings can access through the senses, and therefore the only sensorial (aesthetic) experience that gives access to universality – the ability to distinguish (both aesthetic and ethic) perfection from (both aesthetic and ethic) imperfection. We can aspire to ethical perfection (the absolute harmony/order inherent in the cosmos) through the experience of beauty. Ethics is closely linked to politics and the running of things according to principles that are based on the realisation of the perfection of the cosmos. Cosmic beauty is not attainable for humans, but it represents a methodology, a measure in the materiality and limitation of our lives, in that we can measure our aspirations and achievements against the perfect beauty (harmony) of the cosmos, which we experience sensorially.

In contrast to the ancient thinkers, modern philosophy introduces the idea that beauty is subjective, and not objective. The concept becomes secularised and intellectualised, with beauty pertaining to the arts and separate from the everyday (Chiodo Citation2016, 39 ff.). In the last 20 years, however, there has been a renewed interest in the philosophical idea of beauty, with analyses extending to the examinations of links between beauty and moral perfection. In Nehamas (Citation2007) a connection is re-established between beauty and desire, and encompassed in Stendhal’s aphorism whereby beauty is the ‘promise of more’ (76). This connection involves ethical interests, in that beauty promises the fulfilment of not just our current desires, but also of those that we are not aware of yet, therefore pushing individuals to work towards the realisation of an existence characterised by a higher quality. Judgements on beauty are therefore commitments to the future.

The metaphysical overtones that can emerge from the account provided above share aspects with ideas about the metaphysics of heritage in Mota Santos (Citation2018). This could be seen in the ethical mission of the Ladins as is engendered by the aesthetic relationship with the landscape. In addition, the Ladin language can be conceptualised as a first place, which is ‘broadly defined as the location from where purportedly a social identity is taken as having emerged by those who see themselves as related to it’. (Mota Santos Citation2018, 121). Language is therefore endowed with ethnogenetic properties – it is the primary location for the emergence and transmission of the collective self and the merging of mythos and logos. As such, language can also engender spaces of potentiality in that it articulates imaginings of heritage futures (Harrison Citation2015a).

As mentioned earlier, the inherent beauty of the Dolomitic landscape is interspersed with those traces that actualise the symbiotic relationship between nature, events and humans, and that have facilitated the compenetrating of beauty and good whilst decontaminating the site from the horrors of war in a process of physical and spiritual renewal. The heroic macro-narrative of WW1 is steeped in myth, however, whilst the normalisation of logos as truth is enacted through the heroic micro-narrative articulated by Ladin in the local LL. In addition, LL enables instances of Ladin to be magnified and monumentalised, therefore facilitating the simultaneous materialisation of beauty and good through logos – the truth of contemporary daily life. Examples of this heroic micro-narrative will be analysed in the next section.

6. Heroism of the everyday

In addition to Ladin featuring on a range of functional bilingual signs (as envisaged by linguistic legislation – e.g. bilingual directional signs and shop signs, see § 3), the aestheticisation of Ladin for the purposes of naming houses was noteworthy. This was in the form of narratives inscribed on buildings, and in the ‘presentation’ of the different towns encompassed in the Valley positioned on the main road granting access to Canazei (an evident threshold) and displaying the traditional local nicknames together with the painted representations of the relevant town signifiers.

Naming homes is a powerful act of creation as we name things into existence – this reinforces the idea of Ladin as first place (see § 5). Naming practices also connect language with landscape as heritage (Eaton and Turin Citation2022, 797). In the given context, home marking strengthens the centrality of the domestic environment both in social and in economic terms, it reinforces local identity and foregrounds the link with the locality by memorialising rooted traditions and clarifying layers of transmission. For example, in La Fusina (Ladin for smithy) indicates the site of the old smithy, which is illustrated with a representation of the old-fashioned workshop with the blacksmith and his assistant portrayed while replacing a horseshoe. The frame of the picture reproducing a stylised parchment roll immortalises the image as precious evidence of past activities that underpin present life and that used to be conducted entirely in Ladin, the local language.

Other examples such as (Cèsa Marmolèda – Ladin for Marmolada House, named after the mountain) actualise the symbiotic relationship between the local built environment and the Marmolada, the highest peak in the area.

provides an example of the actualisation of logos through the process of inscribing the personal in the public. The house is a recent building with a traditional design and displays framed inscriptions in Ladin painted on the external walls and narrating the origins of the building – the replica of an eighteenth century aristocratic residence. The central text above the first line of windows reports ‘This house was built in 1960–1962 by the village doctor G. Pasquali, the parish priest was Carlo Locatin da Pozza and Head of the Municipality Dantone Luigi del Pich’.

In the process of reproducing the ancient custom of positioning an external inscription with the name of the owner on a building, Ladin becomes endowed with the connotations of undisputable ownership of both building and locality – a prerogative that makes claims of belonging deeply rooted. In addition, the name of the house, Cesa Melester (bottom right-hand corner in the image) translates as Rowan Tree House. In Nordic traditions the Rowan tree is a symbol of protection and strength – it is in fact a resilient tree that can stand adverse environmental conditions and as a result it is characterised by heroic connotations.Footnote6 The characteristics of this pioneer species establish an intertextual relationship with the complex visual narrative displayed a few steps down the road (see ). The typology of named houses represents one of the discursive frames (Coupland and Garrett Citation2010) employed in the locality in the performance of the heroic, and reconnects present and past heroic narratives.

In line with the longstanding custom of naming private homes, the choice of Ladin names and titles for private buildings in our context suggests an intent to consolidate and publicly share an assertion of ethnolinguistic and regional identity. In addition, this type of signs can be seen as ‘a statement about the beliefs and values of the city’s inhabitants’ (Garrioch Citation1994, 30–31), a manner of claiming possession of a material artefact that functions as a boundary-making device – a local landmark is meaningful for those who are familiar with it, and not for outsiders. These naming practices are reminiscent of heraldry and coats of arms that served the purpose of proudly displaying an individual’s or a family’s privileged social standing. However, this practice was reproduced at a humbler level, too, and provides an example of the construction of a collective Alpine identity inhabited by the humble members of the Dolomitic valleys (as the central positioning of ordinary people suggests).

The striking appearance of a decorated external wall right at the beginning of the town is a rich example of the spatial and visual materialisation of logos encompassing both alphabetical and other semiotic conventions. The outer, peripheral frame of the wall consists of the busts of local dignitaries (encircled at the top) and of pioneering mountain climbers (lined up at the bottom). A series of shields provide internal frames for the illustration of human figures and symbols of the peoples of the valley, known by their nicknames rather than by their surnames, as old naming practices dictated and as is still the custom in rural communities in Italy. The text in large font says in Ladin Sorainomes dei paises de Faša (Nicknames of the villages of [the] Fassa [valley]).

The shields fashioned as coats of arms (conferring status to local groups) are evocative of the mission of the founders of the original settlements and strike the visitor as a magnified representation of local genealogies occupying an entire wall of a building positioned on the main road into the town. The shields are characterised by those naturalistic features that define the essential components of local identity – the frames are brown, in keeping with the wooden background of the building and with a key signifier of mountain life: trees as landscape, but also (worked) wood – a versatile and sustainable provider of primary needs (shelter, home and work commodities, fire). Additional naturalistic details such as the Alpine Star/Edelweiss, a flower found at high altitudes, adorn the frames of the shields and complement the brown of the wood and the other colours reproducing the surrounding landscape – earthly tones composing a palette fading into shades of green and grey, and contrasting with the blue of the sky. The idyllic scenes represented in the shields idealise bygone times and immortalise the activities (the coopers – botaces - of Gries; second shield from right, top line) or the main personality traits (the profiteers – pelacristi - of Mazzin; second shield from left, bottom line) for which the inhabitants of the different villages were famous. With this monument to local personalities being exactly at the point of access to the town of Canazei, the town shield (detail in ) features prominently in the middle of the upper line, and the appellative of ‘gourmets’ (pazedins) is displayed proudly – the pazeida was an implement used to make a type of stuffed ravioli, a local delicacy. Canazei’s shield is placed immediately above the second larger shield representing Campitello (and the goats – beches - that used to be bred there), the next village on the main road that was moved into and out of the jurisdiction of Canazei several times over the twentieth century, hence the strong ties between the two sites (ISTAT Citation2001).

The examples of magnified and monumentalised language discussed above construct LL discourses of heroism through Ladin and the foregrounding of aspects such as the continuous struggle (to emerge), and local resilience (to maintain a role) and resistance (to survive). The local linguistic ecology requires special efforts to make the smallest ethnolinguistic group in the area visible, and LL is a significant resource to enact a heroic dimension, one where the etymology of the word hero (Greek hērōs), meaning protector or defender, is a primary component of the local character.

It is evident that LL is instrumental in the process of heroicisation of the everyday and helps to foreground some of the key components of the hero archetype (Campbell Citation2008). The hero is generated by narration and self-narration – the reiteration of mythos in processes of memorialisation, and the transformation of mythos into logos through material artefacts and written accounts, have engendered the permanence of the heroic as a structural aspect of local life. Ladin in LL constructs a visual narration that facilitates the performance of the heroic as everyday practice and enhances heroic features, such as acting in extraordinary circumstances and being faced with repeated challenges and obstacles (WW1 in the past, a competitive linguistic market in the present).Footnote7

7. Conclusion

The article highlights the key role of LL in the construction of heroic landscapes as they have materialised in a small area in northern Italy which lies at the confluence of multiple ethno-linguistic traditions. The heroic dimension emerges enhanced by the resilience of local speakers, who have succeeded in maintaining their linguistic and cultural specificity (performed aspects of heritage) in the face of daunting difficulties. One such difficulty is the miniscule size of the Ladin-speaking group, which is challenged by immediately surrounding areas where both another minority language (German) and the majority language (Italian) enjoy stronger positions in the linguistic market.

The visibility of local heroic narratives is stratified and rooted in the widespread awareness of the significant role of local fighters in WW1 – something that gained wider appreciation on the occasion of the centenary of the end of the Great War in 2018 and has since prompted additional initiatives heightening the profile of the small community for international audiences beyond their touristic importance.

The romantic view of Alpine mountaineering was enhanced by the subsequent framing of the act of climbing as a pure, heroic and solitary endeavour between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. For the benefit of a modernist audience, this perspective foregrounded once again the exceptional individual relying on their skill and on minimal protective gear, in preparation for the ethical enterprise represented by WW1. It is rather apt that this approach is known as alpinismo eroico (heroic Alpine mountaineering, as in Crippa Citation2004, 10–13), and is part of the process of the sacralisation of the mountain as the physical trait d’union between heaven and earth – one of the prerogatives of the classical hero. The heroic narrative permeating local history is re-enforced through the visibility of Ladin in the public space. The resulting picture is one of heritage as assemblage formed by heterogeneous groupings of things and people (as in Harrison Citation2015b, 306) where LL accomplishes the transformation of the heroic from the individual dimension to the collective and produces shared discursive formations of the hero as heritage.

The vertical journey that characterised the experience of WW1 was accomplished through an aesthetic experience that elevated the protagonist in that it put them in direct contact with the cosmos. The primordial features of the dramatic landscape provide an optimal visual and perceptual frame to enduring cosmogonies dating back millennia, where space and its signifiers are indispensable for the production of life (Campbell Citation2008, 234), and where the concept of space-less and darkness is replaced with that of space-ful and light, engendering visibility and perception. At the same time, the sheer physical magnitude of the mountain peak, the iconic Marmolada, makes it the ideal earthly podium for accessing cosmic beauty and attaining the moral heights of the ethical enterprise. Actually inhabiting its caves and crevices for months on end and in the harshest possible weather conditions, when not excavating its icy surfaces to create trenches, galleries, shelters and walkways to provide liminal spaces of wartime life, is no less heroic than the deeds narrated in the mythical accounts of the distant past. The modern hero therefore inhabits the classical ideal and reproduces the archetypical journey where the struggle for (linguistic) justice is part of the ethical mission and where the recomposition of the self, previously split by the disjunctive experience of the war, is enacted through LL.

By designating the accomplished perfection of the individual, the platonic ideal encompassed in the expression kalòs kai agathòs integrates an ethical and simultaneously aesthetic responsibility that translates into the necessity for action – something that LL actively contributes to through the manipulation of the public space and by enacting the harmonisation of natural landscape and spaces of living via the erection of material and symbolic thresholds, naming practices and the monumentalising of identity. The artistic intent of examples such as actualises a dialectical relationship between doing (executing a mural painting) and reflecting, highlighting the cognitive and ethical potential of the aesthetic experience. In this process the LL artefact represents the material link between aesthetics and ethics, and acts as a reminder of the moral mission – an imperative inherited through the universally acknowledged heroic past of the locality which continues to be consolidated publicly in the dialectical relationship between mythos and logos. Importantly, both this dialogic dimension and the materiality of the linguistic artefacts foreground the role of language as both tangible and intangible heritage. The emergence of the hero as heritage is therefore the result of ‘complex, interconnected webs of relationships across time and space’ (Harrison Citation2015b, 306), where Ladin provides a tangible infrastructure of verbal heritage. The latter is actualised through LL, in that it contributes to the (spatial) construction of the underlying foundations of a system of meaning that is necessary for the social functioning of the community and that validates the past in order to build the future.

The classical hero accomplishes their mission by achieving the goal of the quest, and the ultimate boon is characterised by the sanctioning of the hero’s attainment of immortality. In the process of secularisation of the heroic journey, the current visibility of Ladin and of its aesthetic potential can be seen as a significant milestone towards securing a future for local aspirations to language normalisation and immortalisation, in keeping with the notion that beauty ‘is the promise of more’. By providing a synthesis of internalised understandings of the heroic enterprise, performed heritage as carried by LL is instrumental in articulating this commitment to the future, and to heritage futures – those that become actualised between the aesthetic experience of the material landscape and the unfolding of the ethical mission in which the local community has been invested.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefania Tufi

Stefania Tufi is a Reader in Italian Studies and Sociolinguistics at the University of Liverpool, UK. Her main research interests lie within Sociolinguistics, in particular minority and heritage languages, language practices in transnational spaces and multilingualism in border and peripheral areas. Her research is multidisciplinary and situated at the intersection of language, memorialisation practices and spatial constructions of identity (the linguistic landscape – exploring language use in public space). She has co-authored the volume The Linguistic Landscape of the Mediterranean – French and Italian Coastal Cities (2015), and co-edited Reterritorializing Linguistic Landscape: Questioning Boundaries and Opening Spaces (2020). She is currently Co-Investigator for the AHRC international networking project Multilingual Heritage: Challenging monolingual memorialisation (AH/T008474/1), to create a research network of researchers interested in questions of heritage, multilingualism, and memorialisation.

Notes

1. Figures are based on the ISTAT 2015 linguistic census (see ISTAT Citation2017)

2. The first double issue of the journal Linguistic Landscape (2015) provides reflections on the main developments of the field, whilst proposing new directions for an increasingly diverse range of studies.

3. The percentage of Ladin speakers in the area ranges between 77% and 97%. This is reflected in language use in Canazei, the location which represents the focus of this study – according to the latest available figures, out of a population of 1,911, 1,524 people (about 80%) speak the local language (Servizio Statistica della Provincia Autonoma di Trento Citation2012).

4. Investigations into toponymy have been carried out both in Heritage Studies (e.g. Erőss, Holányi, and Tátrai Citation2022) and in LL (e.g. Tufi Citation2020).

5. A definition of what constitutes a sign in LL studies is part of an ongoing debate. For a recent review of methodological issues, including the nature of LL tokens, see Gorter (Citation2018).

6. As a people inhabiting these Alpine valleys since pre-Roman times, and due to historical Germanic influences, Ladins perceive themselves as part of an Alpine and Mitteleuropean identity which is decisively ‘Nordic’, and particularly so in the Italian context (Craffonara, Citation1986; Richebuono, 1992).

7. The notion of the linguistic market was introduced by Bourdieu (Citation1977) in relation to his theory about cultural capital. Here it is used in a generic sense that highlights the competitive nature of language maintenance and survival in the area.

References

- Ashley, S. L. T., and S. Frank. 2016. “Introduction: Heritage-Outside-In.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (7): 501–503. doi:10.1080/13527258.2016.1184704.

- Bizzocchi, M. 2014. “Nuove prospettive storiografiche sulla Grande Guerra: violenze, traumi, esperienze.” E-Review 2. https://e-review.it/bizzocchi-nuove-storie-sulla-grande-guerra-violenze-traumi-retaggi ( accessed 28/8/21)

- Blommaert, J. 2005. Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511610295.

- Bodei, R. 1995. Le forme del bello. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. “The Economics of Linguistic Exchanges.” Social Science Information 16 (6): 645–668. doi:10.1177/053901847701600601.

- Butler, J. 1997. Excitable Speech. The Politics of the Performative. New York NY: Routledge.

- Campbell, J. 2008. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd ed. Novato, CA: New World Library.

- Chiodo, S. 2016. “Storia breve della relazione filosofica tra la bellezza e l’esistenza etica e politica degli esseri umani.” Itinera 11: 34–48.

- Corà, V. 2008. “La guerra in montagna.” In Gli italiani in Guerra: conflitti, identità, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni. Vol. 3. La Grande Guerra: dall’intervento alla vittoria multilata, edited by M. Isnenghi and D. Ceschin, 647–655. Torino: UTET.

- Coupland, N., and P. Garrett. 2010. “Linguistic Landscapes, Discursive Frames and Metacultural Performance: The Case of Welsh Patagonia.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2010 (205): 7–36. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2010.037.

- Craffonara, L. 1986. “Die Dolomitenladiner. San Martin de Tor: Inst.” Cultural Ladin Micurà de Ru.

- Crippa, L.2004. Appunti di storia dell’alpinismo. Seregno: Club Alpino Italiano. https://www.caiseregno.it/sites/default/files/APPUNTI%20DI%20STORIA%20DELL’ALPINISMO.pdf ( accessed 19/8/21)

- Delai, N., and M. Marcantoni. 2005. Identità e sviluppo. Le minoranze ladine pensano il proprio futuro. Milano: Franco Angeli.

- Dell’aquila, V. 2010. “Comunità ladina.” In Enciclopedia dell’italiano. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/comunita-ladina_%28Enciclopedia-dell%27Italiano%29/ ( accessed 23/6/2021)

- Dell’aquila, V., and G. Iannàccaro. 2006. Survey Ladins: Usi linguistici nelle valli ladine. Trentino-Alto Adige: Regione Autonoma Trentino-Alto Adige.

- Eaton, J., and M. Turin. 2022. “Heritage Languages and Language as Heritage: The Language of Heritage in Canada and Beyond.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28 (7): 787–802. doi:10.1080/13527258.2022.2077805.

- Eco, U. 1984. Semiotica e filosofia del linguaggio. Torino: Einaudi.

- Erőss, Á., Á. Holányi, and P. Tátrai. 2022. “Toponymic Politics and the Role of Heritagisation in Multiethnic Cities in Romania.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28 (6): 763–777. doi:10.1080/13527258.2022.2076719.

- Eurostat. 2019. GDP per capita in 281 EU regions. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/9618249/1-26022019-AP-EN.pdf/f765d183-c3d2-4e2f-9256-cc6665909c80 ( accessed 26/8/21)

- Finocchi, R. 2013. “Sette indizi sulla creatività: tra estetica, semiotica e filosofia del linguaggio.” E|C, Serie Speciale VII (17): 105–111. accessed 17/6/21. http://www.ec-aiss.it/monografici/17_senso_e_sensibile/senso_e_sensibile_FINOCCHI.pdf

- Frisk, K. 2019. “What Makes a Hero? Theorising the Social Structuring of Heroism.” Sociology 53 (1): 87–103. doi:10.1177/0038038518764568.

- Garrioch, D. 1994. “House Names, Shop Signs and Social Organization in Western European Cities, 1500–1900.” Urban History 21 (1): 20–48. doi:10.1017/S0963926800010683.

- Gibelli, A. 1998. La Grande Guerra degli italiani 1915-1918. Milano: Sansoni.

- Gilbert, M. 1994. The First World War: A Complete History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Goebl, H. 2020. “Il ladino e le altre lingue romanze.” In Manuale di linguistica ladina, edited by P. Videsott, R. Videsott, and J. Casalicchio, 202–240. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110522150-006.

- Gorter, D. 2018. “Methods and Techniques for Linguistic Landscape Research.” In Expanding the Linguistic Landscape: Linguistic Diversity, Multimodality and the Use of Space as a Semiotic Resource, edited by M. Pütz and N. Mundt, 38–57. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. doi:10.21832/9781788922166-005.

- Gragnani, C. 2017. “L’altra sponda del conflitto: le scrittrici italiane e la prima guerra mondiale.” Allegoria 76 (luglio/dicembre): 41–62.

- Harrison, R. 2015a. “Beyond “Natural” and “Cultural” Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene.” Heritage & Society 8 (1): 24–42. doi:10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036.

- Harrison, R. 2015b. “Heritage and Globalization.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by E. Waterton and S. Watson, 297–312. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137293565_19.

- Harrison, R., and D. Rose. 2010. “Intangible Heritage.” In Understanding Heritage and Memory, edited by T. Benton, 238–276. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Heller, M., and B. McElhinny. 2017. Language, Capitalism, Colonialism: Toward a Critical History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Hou, S. 2019. “Remembering Trees as Heritage: Guji Discourse and the Meaning-Making of Trees in Hangzhou, Qing China.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (5): 455–468. doi:10.1080/13527258.2018.1509229.

- IATA 2022 September passenger demand stays strong. https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/2022-releases/2022-11-07-02/ ( accessed 24/11/22)

- Isnenghi, M. 1989. Le guerre degli italiani: parole, immagini, ricordi 1848-1945. Milano: Mondadori.

- Isnenghi, M. 1991. “Le montagne della letteratura e della memoria.” In La montagna veneta in età contemporanea. Storia e ambiente. Uomini e risorse: convegno di studio, Belluno, 26-27 maggio 1989, edited by A. Lazzarini and F. Vendramini, 333–340. Roma: Edizioni di storia e letteratura.

- ISTAT 2001 Unità amministrative. https://ebiblio.istat.it/SebinaOpac/resource/unita-amministrative-variazioni-territoriali-e-di-nome-dal-1861-al-2000-popolazione-legale-per-comun/IST0031557?locale=eng ( accessed 9/7/21)

- ISTAT 2017 L’uso della lingua italiana, dei dialetti e di altre lingue. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/207961 ( accessed 14/4/23)

- Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality. A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold.

- Landry, R., and R. Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language & Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49. doi:10.1177/0261927X970161002.

- Leed, E. J. 1981. No Man’s Land. Combat and Identity in World War I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leoni, D. 2015. La guerra verticale. Uomini, animali e machine sul fronte di montagna 1915-1918. Torino: Einaudi.

- Linguistic Landscape: An International Journal. 2015. 1 (1–2).

- Marschall, S. 2006. “Commemorating ‘Struggle Heroes’: Constructing a Genealogy for the New South Africa.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (2): 176–193. doi:10.1080/13527250500496136.

- Mondini, M. 2008. Alpini. Parole e immagini di un mito guerriero. Laterza: Roma-Bari.

- Mota Santos, P. 2018. “The Concept of ‘First-place’ as an Aristotelean Exercise on the Metaphysics of Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1393448.

- Nehamas, A. 2007. Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Palla, L. 2015. La grande guerra nelle valli ladine. Fra realtà e mito. Trento: Curcu & Genovese.

- Palla, L. 2020. “6. Coscienza linguistica e identità ladina.” In Manuale di linguistica ladina, edited by P. Videsott, R. Videsott, and J. Casalicchio, 243–272. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110522150-007.

- Robertson, I. J. M. 2008. “Heritage from Below: Class, Social Protest and Resistance.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. edited byB. Graham and P. Howard, 143–158. Ashgate: Aldershot, 10.4324/9781315613031-8.

- Rosenbaum, Y., E. Nadel, R. L. Cooper, and J. A. Fishman. 1977. “English on Keren Kayemet Street.” In The Spread of English, edited by J. Fishman, A. W. Conrad, and L. C. Robert, 179–196. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

- Scarry, E. 1999. On Beauty and Being Just. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400847358.

- Scollon, R., and S. Wong Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203422724.

- Servizio Statistica della Provincia Autonoma di Trento. 2012. 15° Censimento della popolazione e delle abitazioni. http://www.statistica.provincia.tn.it/binary/pat_statistica_new/popolazione/15CensGenPopolazione.1340956277.pdf ( accessed 26/8/21)

- Sharp, J. 2009. “Geography and Gender: What Belongs to Feminist Geography? Emotion, Power and Change.” Progress in Human Geography 33 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1177/0309132508090440.

- Silva, L., and P. Mota Santos. 2012. “Ethnographies of Heritage and Power.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18 (5): 437–443. doi:10.1080/13527258.2011.633541.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203602263.

- Smith, L. 2012. “Editorial. A Critical Heritage Studies?” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18 (6): 533–540. doi:10.1080/13527258.2012.720794.

- Thompson, M. 2008. The White War. Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915-1919. London: Faber and Faber.

- Tufi, S. 2020. “Instances of Emplaced Memory: The Case of Alghero/L’Alguer.” In Multilingual Memories. Monuments, Museums and the Linguistic Landscape, edited by J. B. Robert and J. Macalister, 237–261. London: Bloomsbury. doi:10.5040/9781350071285.ch-011.

- UNESCO. 2003. “Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention

- Vernant, J. P. 1980. Myth and Society in Ancient Greece. Brighton: Harvester.

- Videsott, P., R. Videsott, and J. Casalicchio, eds. 2020. Manuale di linguistica ladina. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110522150.

- Wallis, J., and D. C. Harvey, eds. 2017. Commemorative Spaces of the First World War: Historical Geographies at the Centenary. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315651170.

- Wallnig, T. 2003. “Language and power in the Habsburg Empire. The historical context.” In Diglossia and Power: Language Policies and Practice in the 19th Century Habsburg Empire, edited by R. R. Schjerve, 15–32. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Winter, T. 2013. “Clarifying the Critical in Critical Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (6): 532–545. doi:10.1080/13527258.2012.720997.