ABSTRACT

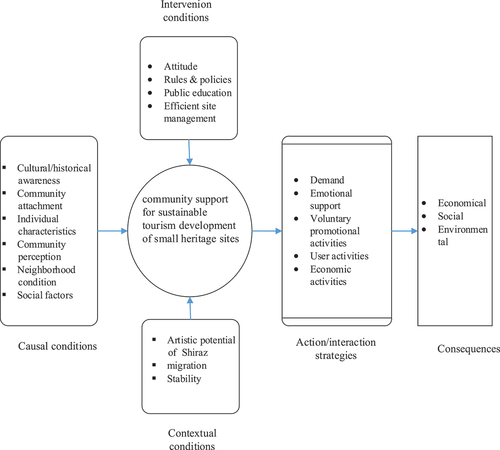

Community support is a key factor in the successful implementation of sustainable tourism development plans at heritage sites. This study presents a paradigm model to provide insight into the structure and process of community support for sustainable tourism development (SSTD) in small heritage sites. Using a social constructionist frame and grounded theory approach, the data from semi-structured interviews with 22 participants living in the historic city of Shiraz in Iran – selected through theoretical sampling – were analysed. In this study, for the first time, the dimensions of the core phenomenon of ‘community SSTD’ in small heritage sites were identified. They were categorised into five strategies of demand, emotional support, voluntary promotional activities, economic activities and user activities. Data analysis also revealed six factors of cultural/historical awareness, community attachment, individual characteristics, community perceptions, social factors and the sites’ neighbourhood conditions as factors affecting community SSTD in small heritage sites. Given the scarcity of qualitative studies conducted in the area of sustainable tourism development in small heritage sites, the findings of this study can be used as a basis for strengthening community SSTD in Iran and elsewhere.

Introduction

Sustainable development is one of the necessities of today’s world and all countries are encouraged to achieve this goal (e.g. United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals). Sustainable development means carrying out development activities in a way that brings positive consequences in all three areas of society, economy and the environment for both today and future generations (MacKenzie and Gannon Citation2019). The UN has defined 17 goals to make the issue of sustainable development more objective (Hall Citation2019). The goals include specific targets and are monitored and reported every year with defined criteria. According to the plan, the goals should be met by 2030 (Labadi et al. Citation2021). Achieving these goals is possible by defining the plans in various fields such as education, healthcare, welfare, natural heritage, cultural heritage and so on.

Cultural heritage includes all the tangible and intangible elements that we have inherited from the past. Planning for their protection, proper use, development and enrichment can contribute to sustainable development (Labadi et al. Citation2021). Cultural/heritage tourism is one of the solutions that can provide the basis for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the field of heritage (Labadi et al. Citation2021). The support of the community for tourism development in cultural tourism destinations is a crucial factor in accelerating the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). Community support refers to the behavioural intentions of residents to support the further development of tourism in their community and arises from the psychological perceptions of individuals (Yu Citation2015). Xie, Lee, and Wong (Citation2020) define community support as the deliberate or unintentional choice of residents after comparing development results with their expectations.

Community support for sustainable tourism development (SSTD) is an issue that has been widely studied in terms of its predictive factors. Researchers in previous studies have examined the impact or interaction of different variables on/with the construct of SSTD (e.g. Demirović Bajrami et al. Citation2020; Eslami et al. Citation2019; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). These quantitative studies have sought to identify important factors influencing community SSTD, but the dependent variable ‘community SSTD’ has not been well explained. Most existing studies ‘give insufficient attention to its exact meaning or measurement’ (Fan et al. Citation2021).

Moreover, the majority of the relevant studies have focused on the scope of tourism in general and few studies have paid special attention to the field of cultural heritage tourism (Rasoolimanesh et al. Citation2017; Zhu et al. Citation2017; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018; Fan et al. Citation2021; Hanafiah, Jamaluddin, and Riyadi Citation2021). Support for the development of cultural heritage tourism is also largely limited to World Heritage Sites or well-known national heritage sites of destinations (Rasoolimanesh et al. Citation2017; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018; Hanafiah, Jamaluddin, and Riyadi Citation2021), while many cultural tourism destinations include small heritage sites that, despite being less well known, have the potential to generate socio-economic benefits for the community (Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell Citation2021). Therefore, it is important to examine the dimensions of community support and understand how to strengthen this support to achieve SSTD in relation to small heritage sites.

One of the most important cultural tourism destinations in West Asia is Iran, where more than thirty-four thousand nationally registered sites are located (Talebian, Pour Ali, and Khasipour Citation2021). These sites date back to prehistoric times, ancient cultures and the Islamic period, and many of them are overlooked by residents and tourists. There are significant numbers of such sites in Iran, which can play a crucial role in the tourism economy. This is particularly the case considering the economic challenges that the country has faced over the past years due to increasing US-led economic sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic. The cooperation and support of communities – as one of the most important stakeholders of these sites – is crucial in creating the ideal conditions for tourism development at these sites.

Through a comprehensive review of the literature on heritage sites, sustainable development and community support, we were able to identify the gaps in defining the dimensions of the construct of SSTD and the process of its formation in the field of small heritage sites. This research, through a grounded theory approach, investigates how the communities in a cultural heritage destination contribute towards achieving SSTD. We do this by focusing on the historic city of Shiraz in Iran.

Our research on small heritage sites in Iran can contribute to international heritage research in several ways. Firstly, it can add to the body of knowledge on heritage preservation and management in Iran, which is an important area of research given the country’s rich cultural heritage and the challenges it faces in preserving its historical sites. Our research can shed light on the unique challenges associated with small heritage sites in Iran and provide insights into how they can be effectively preserved and promoted. Secondly, our research can provide comparative insights into heritage preservation and management in other countries and regions. By comparing the strategies and approaches used in Iran with those used in other contexts, we can identify similarities and differences in the challenges faced by small heritage sites, as well as the best practices for their preservation and promotion. Our research can contribute to the broader discussion on the role of small heritage sites in promoting sustainable tourism development. As tourists increasingly seek out authentic and off-the-beaten-path experiences, small heritage sites have the potential to offer unique and culturally rich travel opportunities. By exploring the ways in which small heritage sites can be effectively integrated into sustainable tourism initiatives, our research can inform and advance the broader conversation on heritage tourism and its potential for economic and social development. Finally, our study offers practical recommendations for policymakers and other stakeholders seeking to foster community support for sustainable development of small heritage sites.

This study is organised as follows. First, we provide a review of the literature in relation to the notions of small heritage sites, sustainable development, and community support for sustainable development. We then provide a discussion of our research methodology and the grounded theory approach to investigate SSTD in a cultural heritage tourism context. Finally, research findings are reported and discussed, and their implications for further research and applications are highlighted.

Literature review

Sustainable development and heritage tourism

Development refers to a process that leads to the improvement of people’s living conditions (Bartelmus Citation1986). Development means change, changes in people’s desires and behaviours, and in the way they perceive the world around them (Dudley Citation1993). It involves human and institutional changes along with economic growth (Tosun Citation2001; Zamfir and Corbos Citation2015). Sustainable development is often seen as a long-term strategy to protect the environment while addressing the needs of current and future generations. Sustainable development is a type of development strategy that manages all assets and resources to increase the long-term prosperity and wealth of the present generation and avoids activities that weaken the prospects of future generations (Tosun Citation2001). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is a collection of 17 interlinked global goals acting as a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2021. The 2030 Agenda calls on the world to take bold and transformative steps to achieve the goals outlined (Hall Citation2019).

In the 2030 Agenda, cultural heritage appears most prominently in Goal 11, which focuses on ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’ as Target 11.4, ‘to protect the world’s cultural and natural heritage’, and more implicitly in other goals such as Goal 4 on ‘Education’, Goal 8 on ‘Work and Economic Growth’, and Goal 12 on ‘Consumption and Production’ (Labadi et al. Citation2021, 10). Heritage is a valuable resource that supports the identity, memory and sense of place and can play a key role in achieving the goals of sustainable development (Labadi et al. Citation2021; Aremu Citation2014). Heritage enhances social cohesion, social welfare and attractiveness of regions and increases the long-term benefits of tourism (Labadi et al. Citation2021). Heritage tourism, due to the distinctiveness of cultural, historical, architectural and archaeological resources of heritage sites, could provide opportunities for sustainable economic development and improve quality of life of communities (Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). Heritage tourism requires a sustainable approach to management and planning (Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell Citation2021) and community support is a key factor in the successful implementation of sustainable tourism development plans at heritage sites (Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). Involving society in sustainable development activities increases the likelihood of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and minimises the challenges of preserving cultural heritage as a fragile and non-renewable resource for present and future generations (Labadi et al. Citation2021).

Community support for sustainable tourism development (SSTD)

Understanding the collective characteristics of a society is a wide-ranging challenge in the social sciences. Communities are not homogeneous and are made up of groups of people who often have very different characteristics (Fan et al. Citation2021). In our study, we define community as a group of people with common interests and different experiences and perspectives who live in a geographical location. In the context of tourism, community support refers to the behavioural intentions of residents to support the development of tourism in their community and arises from the psychological perceptions of individuals (Yu Citation2015). Community support is defined as the intentional or unintentional choice of residents after comparing development outcomes with their expectations (Xie, Lee, and Wong Citation2020). Community support is an integral part of hospitality and tourism products, which affects cost levels, visitor satisfaction and visitor willingness to revisit (Fan et al. Citation2021).

The subject of SSTD has been studied considerably in relation to its predictive factors (e.g. Lee Citation2013; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018; Eslami et al. Citation2019; Demirović Bajrami et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2021). In these quantitative studies, researchers have examined the extent to which different variables influence or interact with the dependent variable ‘community SSTD’. Variables that have been considered predictive include; (1) community satisfaction, (2) attachment, (3) involvement, (4) empowerment, (5) perceived benefits and costs, (6) neighbourhood conditions, (7) residents’ personality, (8) sense of place, (9) cultural awareness, (10) quality of life, (11) infrastructure development, and (12) recreational amenities.

Local community satisfaction affects supportive behaviour towards tourism development (Nunkoo and Ramkissoon Citation2011a; Eslami et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Kanwal et al. Citation2020). Community attachment reflects the emotional connection to the community and enables effective collaboration (Lee Citation2013; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). Community involvement relates to participation in community decision-making and increases when benefits of heritage tourism are shared (Lee Citation2013; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). Community empowerment involves collective action of marginalised groups and local communities (Khalid et al. Citation2019). Perceived benefits and costs shape community support towards tourism development (Nunkoo and Ramkissoon Citation2011a; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018; Zhang et al. Citation2020; Hanafiah, Jamaluddin, and Riyadi Citation2021). Satisfaction with neighbourhood conditions relates to physical, social, and economic aspects (Nunkoo and Ramkissoon Citation2011a, Citation2011b). Residents’ personality refers to individual behavioural patterns (Jani et al. Citation2014; Moghavvemi et al. Citation2017; Mothersbaugh et al. Citation2020). Sense of place results from the interaction between humans and nature, personal emotion, and unique experiences (Zhu et al. Citation2017). Community awareness and agreement to sustainable tourism development are necessary precursors to tourism education and training programs (Cárdenas, Byrd, and Duffy Citation2015). Quality of life is assessed through life satisfaction (Woo, Kim, and Uysal Citation2015; Yu, Cole, and Chancellor Citation2018; Eslami et al. Citation2019). Access to tourism locations through transportation infrastructure is vital (Kanwal et al. Citation2020). Recreation amenities and entertainment are also important factors for residents (Eslami et al. Citation2018).

Past studies have used community support as a dependent variable and ‘few have thoroughly explored the attributes of these attitudes’ (Fan et al. Citation2021, 3. For example, Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (Citation2011b) used a four-item scale to measure support for tourism development. Lee (Citation2013) and Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan (Citation2018) used a similar scale with six items. Boley and Strzelecka (Citation2016) also designed a global tool with four items and emphasised the community’s perceptions of tourism; however, ‘the more individual level of attitude, such as how they will welcome tourists and how they would like to participate in tourism, is neglected’ (Fan et al. Citation2021, 4). In most of these quantitative studies, the construct of community support for tourism development is simplified, and inadequate attention has been paid to its meaning and measurement. To better understand the meaning and structure of the construct of ‘community support for tourism development’, Fan et al. (Citation2021), for the first time, designed a scale based on the results of a qualitative study. Fan et al. (Citation2021) conducted a number of semi-structured interviews with residents of two indigenous Chinese communities which were analysed using content analysis. This approach identified two dimensions of ‘originality’ and ‘hospitality’ which could support local tourism development. Based on these dimensions, a questionnaire with 12 items was consequently designed and validated, which demonstrates the importance of the qualitative data. A shift from quantitative studies to qualitative studies, with the aim of identifying/understanding the dimensions/factors of the construct of community support of tourism development, is therefore needed.

Small heritage sites in Iran

Iran is a country in Southwest Asia with nine thousand years of history, which contains many historical sites from prehistoric times, ancient cultures and the Islamic period (Pirnia, Ashtiani, and Taheri Citation2016, 37). Iran holds more than thirty-four thousand heritage sites which have been nationally registered, 24 of which are considered World Heritage Sites (Talebian, Pour Ali, and Khasipour Citation2021). This positions Iran among the top ten countries in the world (as of August 2021) in terms of World Heritage Sites (UNESCO, Citation2021). There are nationally registered sites in all parts of Iran, but many of them are located in the Fars province, which is in the southern half of the country. Fars province – where the city of Shiraz is located – was one of the most important capitals of the first empire in the world – the Achaemenids (559–330 BC) – and after that it was chosen as the capital during the Sassanid period (224–651 ad), Al-Buwayh (945–1055) and Zand Dynasty (1750–1779). There are more than three thousand nationally registered sites in this province, four of which (Persepolis, Pasargad, the ancient Sassanid landscape and the Persian Garden of Eram) have also been registered internationally (World Heritage status). The historic city of Shiraz is the centre of Fars province and is one of the well-known cultural tourism destinations in the Middle East. The fame of this city is mostly due to the presence of the tombs of two prominent poets in Persian literature (Hafez and Saadi). For example, according to the country’s Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts, the highest number of visits per year to a historical monument in the country are to Hafez’s tomb in Shiraz (MCTH Citation2021).

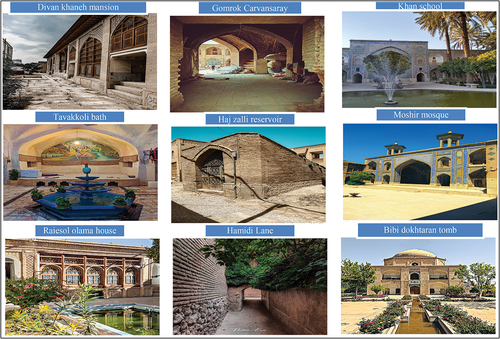

Despite the existence of more than six hundred national heritage sites in Shiraz, most of these sites can be considered as small heritage sites. Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell (Citation2021, 4) categorised small heritage sites as those sites which (1) are nationally registered and represent the distinctive character and uniqueness of the region, (2) enhance local identities, pride and sense of belonging, (3) are less well known outside of their region or unknown nationally/internationally, and (4) are capable of providing socio-economic advantages for communities. These sites in Shiraz include a diverse range of old houses, inns, arches, tombs, reservoirs, baths, schools and religious sites, most of which are located in the historic district of Shiraz ().

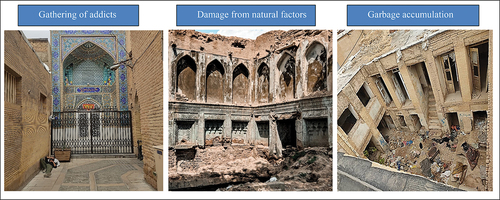

Small heritage sites in Shiraz are facing multiple challenges such as damage from natural factors like wind and rain, vandalism, gathering of addicts, garbage accumulation, and vermin infestations (). These issues not only threaten the preservation of the sites but also negatively impact the quality of life of the local community, leading to dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the neighbouring community of these sites is struggling with various social issues such as unemployment, poverty, and addiction, making the need for sustainable development even more pressing.

Shiraz has the second highest unemployment rate amongst cities in Iran. Developing sustainable tourism based on the potential of these small heritage sites can address these challenges by providing employment opportunities and contributing to the well-being of the community. Additionally, sustainable tourism development can also ensure the preservation of these sites for future generations to enjoy. Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell (Citation2021) conducted a study on the challenges of sustainable development in small heritage sites in Shiraz. The authors identified planning and policy, resources, desire/community support, knowledge, marketing activities, and awareness as significant challenges in their research. Building on this, the present study aims to explore the crucial role of community support in the preservation and promotion of small heritage sites. Specifically, the study investigates the expectations and requirements for community cooperation and participation in tourism development at these sites. The research seeks to identify the roles that are expected of the community, as well as the necessary prerequisites and contextual factors that should be strengthened or provided to facilitate their involvement.

Methodology

Research design and sampling

In order to explore the dimensions of community SSTD and develop a theoretical model in relation to community SSTD in small heritage sites, we have employed a qualitative research design. Since most previous studies in this subject area have employed quantitative methodologies – which has often led to a superficial understanding of concepts – the present study uses qualitative methodologies to gain a deeper understanding of the meanings that respondents attribute to topics and phenomena. The aim of the present study was not to generalise the findings from the population of respondents who are concerned with the development of sustainable heritage tourism, but rather to gain a deeper insight into the mental models of the interviewees through their own words (Backman and Kyngäs Citation1999). Therefore, the present study used the grounded theory approach to analyse the data collected from individual interviews.

Grounded theory is a theory that is extracted directly from data that has been regularly collected and analysed during research. In this method, data collection, data analysis and final theory are closely related. In this way, the researchers begin to work in the field of reality and allow the theory to emerge from the data they collect (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). A theory thus extracted from data may be closer to reality than a theory that puts together a number of concepts based on experience or mere speculation (Stumpf, Sandstrom, and Swanger Citation2016). Grounded theories, as they are extracted from the data, can be more insightful, reinforcing understanding and guiding action (Matteucci and Gnoth Citation2017).

In this study, theoretical sampling was used for continuous data collection and analysis. Theoretical sampling is a type of data collection that is based on evolving concepts and the concept of comparison, which means that we go to places, people and events that maximise the possibility of discovering diversity and enriching categories in terms of features and dimensions (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). In our study, people from the community of Shiraz () who were either experienced in helping to develop sustainable tourism in small heritage sites or aware of the experiences of others and had a special interest in the development of tourism in small heritage sites were interviewed. In total, 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted between July and October 2021. Data collection in the grounded theory method continues until the categories are saturated (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). In this study, theoretical saturation occurred with interview 19 and three additional people were interviewed to ensure that this was in fact the case. These interviews lasted an average of 50 minutes. The main questions of the interviews focused on (1) why people support the development of tourism in small heritage sites, (2) how they show support and (3) what the outcomes are.

Table 1. Participant profile.

Data analysis approach

The data analysis process, due to its importance in the grounded theory approach, was performed in three stages of coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). These three steps were performed – in accordance with the grounded theory approach – in the form of open, axial and selective coding. In open coding, researchers carefully study the transcribed material and memos associated with it. The interview data is broken down into distinct sets of meanings (Matteucci and Gnoth Citation2017). These distinct sets of meanings are given conceptual labels. Concepts are the basic units of analysis in grounded theory. Then, in the axial coding stage, any number of codes that are related in terms of concept and characteristics are collected and organised around a category. Thus, after the process of breaking the interviews into codes and concepts in open coding, in axial coding they are related and categorised around the main topics (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998).

Selective coding is done by selecting concepts and topics that seem to be effective in extracting the main category of the data. This step is done with the aim of integrating and refining the data, in order to develop the main category and theory. In selective coding, an attempt is made to select the categories in a way in which the extracted main category covers most of the concepts created in the previous steps (Stumpf, Sandstrom, and Swanger Citation2016). These three coding steps are not necessarily followed sequentially, and due to the nature of the research, researchers have moved between these steps to achieve the best results. During the triple coding process, the paradigm analysis tool was used according to what Strauss and Corbin had in mind. The paradigm used consists of three parts including conditions, action/interaction and consequences (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). This triple paradigm has acted as a guide for researchers in all stages of the research, from asking questions to creating theory, and has led to a better organisation of findings.

Findings and discussion

Open and axial coding

In the open coding stage, after analysing the content of the raw data, 116 concepts were identified (). Then, in the axial coding stage, the concepts with similar characteristics and properties were grouped to form subcategories (). Subcategories are at a higher level and are more abstract than concepts. Axial coding also uses the paradigm model to better identify structure and process. The paradigm model helps to collect and organise the data so that the structure and the process are connected (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998).

Table 2. Concepts and categories.

Conditions

Conditions are a set of events that create situations, issues and matters related to a phenomenon. Labels such as causal, intervention and contextual are used for conditions.

Causal conditions

Strauss and Corbin Citation1998 defined causal conditions as those events that affect phenomena. In this study, six subcategories of cultural/historical awareness, community attachment, individual characteristics, community perceptions, social factors and neighbourhood conditions were categorised in the category of causal conditions.

Cultural/historical awareness was one of the most common issues raised by the interviewees. By informing the community about the artistic, cultural and historical value of the heritage left by the past, they become eager to protect and use small heritage sites. This, therefore, provides the condition for these types of attractions to become more visible in Shiraz heritage tourism. The importance of community awareness in the process of supporting the development of sustainable tourism has been recognised in previous studies (Cárdenas, Byrd, and Duffy Citation2015; Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell Citation2021). Interviewee 7, for example, said, ‘First of all, people should know about these sites. People are not aware of the art used in these sites and their historical background. So, it has made them reluctant to pay attention them’. Interviewee 10 similarly said, ‘The people of Shiraz think that old houses are more useful for tourists to come and see, not themselves’.

The subcategory of community attachment in the words of the interviewees refers to the concepts of the feeling of belonging to the place, authenticity, empathy of individuals of society, and closeness of ethnicities. In this regard, Interviewee 8 believed that people must preserve the city and its historic district. The noble people have left the historic district and right now they are embarrassed to say that they are from a certain neighbourhood of the historic district. People who are currently living there do not feel a sense of belonging to the historic district.Interviewee 19 also stated that ‘unfortunately, in Fars province, we have anti-ethnic views. Some tribes are insulted and we must respect the tribes. By doing so, we strengthen the sense of belonging. If someone feels this sense of belonging, they become a cultural ambassador’. Community attachment and sense of place have also been identified as effective factors influencing SSTD of heritage tourism in previous studies (Zhu et al. Citation2017; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018). Furthermore, a significant relationship between community attachment and support for tourism development (in general) has been shown in a number of past studies (Lee Citation2013; Eslami et al. Citation2019; Zhang et al. Citation2020; Demirović Bajrami et al. Citation2020; Moghavvemi et al. Citation2021). Community attachment includes the sense of belonging and being rooted in a society and refers to the psychological relationship of individuals in a society with a series of meaningful elements. This emotional connection can provide a basis for effective dialogue and cooperation between people in the community (Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018; Rao Citation2009).

The subcategory of individual characteristics is derived from two dominant concepts that were highlighted in the interviews – personality and values. Interviewee 5, for example, stated, ‘The nature of the people of Shiraz is far from exhibitionist and maybe this is the reason that they do not like to be extroverts. They prefer to be helpful and supportive’. Interviewee 18 also argued that ‘the people of Shiraz and the south of Iran are more interested in indulgence than in preserving their heritage’. Interviewee 17 similarly thought that ‘culturally, the issue of demanding has always been more a characteristic of the people of Isfahan [a neighbouring competitor city and a major tourist hub in Iran], which may have deep cultural, family and climatic roots. The people of Shiraz have always had a thoughtful characteristic’. Personality is ‘an individual’s characteristic response tendencies across similar situations’ (Mothersbaugh et al. Citation2020, 373). Residents’ personality can play an important role in forming overall support for tourism development (Moghavvemi et al. Citation2017). In their research, Moghavvemi et al. (Citation2017) analysed the support for tourism development in relation to the variables of residents’ personality, emotional cohesion and community commitment. The moderating role of personality in the relationship between satisfaction and support for tourism development was also demonstrated by Moghavvemi et al. (Citation2021). According to Rokeach (Citation1973), the value is a stable or prescriptive or imposed belief about a preferred or desirable state of behaviour or a final state of being. These values are organised as value systems along a continuum of relative importance. In our study, the values of wisdom, curiosity, pleasure, social recognition, love, beauty of nature and art were identified by the interviewees. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the relationship between values and SSTD.

Community perceptions was another causal condition obtained from the interviews. Interviewees, in their conversations, indicated that their perceptions of the benefits and costs of developing tourism at small heritage sites affect their level of support. Interviewee 9, for instance, said, ‘People have now realised that tourists can bring economic prosperity to their region’. Interviewee 8 also mentioned that ‘we have a person whose home is a national site, but it is not profitable for him to maintain it. Consequently, it is turned into a Vakil Bazaar’s [the main bazaar of Shiraz city] warehouse. It is rented to Afghan people who have no knowledge of its value. He does this because the house does not benefit him’. According to social exchange theory, communities that understand the benefits of tourism are more likely to support sustainable tourism development, and, conversely, perceived costs of tourism development may reduce communities’ intention to support tourism development (Rasoolimanesh et al. Citation2017). A significant relationship between community perceptions of the benefits and costs of tourism and SSTD of heritage tourism has been shown in the studies of Zhu et al. (Citation2017), Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan (Citation2018) and Hanafiah, Jamaluddin, and Riyadi (Citation2021).

The conditions around small heritage sites – categorised as neighbourhood conditions – was another factor that has impact on community SSTD in these sites. Since most of the small heritage sites are located in the historic district of Shiraz, it was considered important to optimise and create urban service infrastructure, provide security and pay attention to its potential for holding events. Interviewee 16, for instance, said, ‘When I visit these sites, I should have an enjoyable and pleasant experience. I should not feel insecure while I am visiting’. Interviewee 15 said, ‘This lady [pointing to his neighbour’s house], who has spent billions [of rials] here, needs all the water, sewage and electrical infrastructure to renovate her house. The government must provide these and collect taxes and duties from her’. Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (Citation2011a) in their study demonstrate that SSTD is under the influence of overall community satisfaction and that neighbourhood conditions have a significant relationship with satisfaction. In Nunkoo & Ramkissoon’s (2011b) study, neighbourhood conditions were measured by traffic, nature, safety and behaviour of children.

Social factors is another subcategory identified in the interviews. It includes the concepts of welfare, public culture, culture of participation, and trust. Interviewee 16, for example, said, ‘These sites are more attractive to foreign tourists because they live in more prosperous societies compared to our people [local residents]. Our people, who have been suffering from economic problems in recent years, are less interested in these places’. Interviewee 4 argued, ‘If a person is found who is trusted by heritage activists and he/she comes and gathers a team of five competent people around himself/herself, they will surely succeed’. Interviewee 5 also mentioned that ‘citizens need to have a greater sense of having influence. Doing a survey on a particular topic, applying the results and showing the achievements to those surveyed helps a lot to reinforce this feeling. I, as a citizen, must see the change’. Trust in regulatory institutions affects the overall acceptance of an action. In previous studies, institutional trust is considered as an effective factor in people’s support for tourism (Nunkoo and Ramkissoon Citation2011a). In our study, however, the results show that interpersonal trust in addition to institutional trust are the influential concepts. Wang et al. (Citation2021) identified community participation as an effective factor in heritage tourism. Residents’ participation in the decision-making process increases the likelihood of community support for tourism and strengthens residents’ desire to preserve their traditional values and lifestyle (Sheldon and Abenoja Citation2001)

Intervention conditions

Strauss and Corbin Citation1998 define intervention conditions as those that can be used in grounded theory research to analyse how individuals or groups respond to an intervention. These conditions often arise from unexpected and incidental situations that need to be addressed through action/interaction (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). Four subcategories of attitude, rules and policies, public education and efficient site management were included in the intervention conditions (). In terms of attitude, Interviewee 4, for instance, explained that ‘clergymen want to look at tourism from a religious perspective. We have to work on their attitude towards tourism developments, which can change the mood of the people as well as the historic district’. Previous studies in relation to tourism development have shown attitude towards heritage tourism development at the local community level is a crucial factor (Zhu et al. Citation2017; Khalid et al. Citation2019). Interviewee 18 said that ‘in order to encourage people to invest or work in these sites, a number of strategic policies need to be formulated’. Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell (Citation2021) identified the lack of comprehensive and up-to-date policies and regulations as one of the major challenges in developing heritage tourism. In relation to public education, Interviewee 3 focused more on the role of creating positive narrative and argued that ‘symbols and pictures of small heritage sites in the city should be seen more around the city’. Interviewee 14 also thought that ‘we need to create a better culture. We need to change the educational system to create a more favourable tourism environment and be able to deal with tourists more appropriately’. Improving promotion strategies and developing education and training programmes have been recognised in previous research related to sustainable tourism development (Cárdenas, Byrd, and Duffy Citation2015; Seyfi, Michael Hall, and Fagnoni Citation2019).

Efficient site management was also one of the subcategories in which a large number of concepts were categorised. Concepts of planning for the operation of small heritage sites, employees (motivation/competence) of relevant government agencies, benchmarking, strengthening of databases, strengthening of specialised libraries, support of ideas and influencers, strengthening of inter-sectoral cooperation, and studying behaviour of tourists were included in this category. The basis for effective heritage management lies in developing ‘a sound, practical, achievable conservation plan’ (Grimwade and Carter Citation2000, 48). This plan should focus on creating opportunities for local communities to work in partnership with heritage professionals in order to set clear development and management goals. The primary objective is therefore to ‘promote and share small heritage sites with others’ (Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell Citation2021). Interviewee 2, for example, argued that ‘one of our main problems is that the sites are shut early. Well, maybe the tourist wants to see Nasir Mosque [heritage site in Shiraz] at night’. According to the majority of the interviewees, both themselves and many members of the community possess valuable ideas and untapped potential to contribute to the development of tourism in Shiraz. However, these resources have not been effectively utilised in a systematic manner until now. It is important to consider that the local government is primarily responsible for two key objectives: enhancing the quality of life for the local community and effectively overseeing the utilisation of local resources (Kapera Citation2018).

Interviewee 4 also stated, ‘I have so much potential and they [heritage organisation] know it but they do not use me at all. Why don’t they use my potential? I have so much experience which can be used to develop heritage tourism’. The need for cooperation between organisations related to small heritage sites for the development of tourism in these sites is felt very much. Interviewee 15 emphasizes the pressing need for cohesive action, stating, ‘unfortunately, the heritage organisation and the municipality are constantly passing historic district activities between themselves while all the related bodies should cooperate’. The first and most important obstacle was the lack of coordination between stakeholders and the resulting conflicting views on tourism development (Seyfi, Michael Hall, and Fagnoni Citation2019). Successful implementation of the principles of sustainable development requires the participation of a wide range of stakeholders who need to work together and have strong leadership as well as local government support (Byrd Citation2007; Kapera Citation2018; Khodadadi, Pezeshki, and O’Donnell Citation2021).

Contextual conditions

Contextual conditions are a specific set of situations that come together at a specific time and place to create a set of situations or issues that individuals respond to through their interactions (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). Three subcategories of stability, migration and Shiraz artistic potential were identified as contextual conditions (). Policy stability and retention of talented/influential people were two concepts that were classified under the category of stability. Interviewee 4, for example, stated, ‘We can never expect progress in art, culture and tourism due to the lack of the retention of experienced people’. The current economic and social climate in Iran has diminished the incentive for elite individuals to remain in the country, resulting in a deceleration of progress across multiple industries. Immigration to Shiraz was highlighted by the interviewees as an important factor impacting on the city and sustainable tourism development. Interviewee 17, for example, argued that ‘one of the things that has made us see less supportive people in the city of Shiraz than the people of Isfahan is the uncontrolled migration to this city’. It is demonstrated that there is a direct relationship between the length of time spent living in the community and community attachment to tourism development (Dutt, Harvey, and Shaw Citation2018).

Shiraz Art School and maintaining prestige/distinctions are under the category of Shiraz artistic potential. Interviewee 19 pointed out that the cost of renovating a historic house in Shiraz is as much as the cost of renovating all the houses in an alley in the historic district of Yazd due to the complexity/multitude of the artistic elements used in it. Interviewee 1 also stated, ‘We are in a period of integration where everything is moving towards a single pattern [being similar to each other]. There is a world system that marginalises and ousts a person like me and I am in a constant battle with this. I am a single component of an infinite system. That’s why I came here’. The community of Shiraz has long been immersed in a rich cultural context, thanks to the presence of its renowned art school. This context has given rise to a unique set of cultural elements that distinguish Shiraz from other cities and have evolved over centuries. It is within this context that the community has developed strategies for the promotion and development of heritage tourism.

The preservation and promotion of heritage and its related traditions can play a vital role in shaping the distinctiveness and individuality of cities. They contribute to the preservation and enrichment of local identities, shared values, and a sense of pride and belonging. Additionally, heritage plays a significant role in attracting tourism, stimulating investments, and fostering the growth of cultural and creative industries, thereby generating employment opportunities. Furthermore, many historic urban areas, with their human-scale design, pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, vibrant atmosphere, diverse functions, and public spaces, enhance the overall liveability of cities. They also promote social inclusion, cohesion, and well-being within communities (Labadi et al. Citation2021).

Action/interaction

Action/interaction is another important part of the grounded theory model of community SSTD in small heritage sites () and refers to strategic tactics and the way in which people manage situations in the face of problems and issues (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). In this study, five subcategories of demand, emotional support, voluntary promotional activities, user activities and economic activities were identified as the community strategies to help and support the development of sustainable tourism in small heritage sites.

The subcategory of demand included the concepts of criticism, petition and protest. Interviewee 4, for example, recounted, When they wanted to sell a series of mosque artifacts, I said, ‘Excuse me, I am the first person to complain to you’. These are museum assets and you can earn money from them. If you sell it, it will end, but if you make a museum out of it, you can make money from it forever. Interviewee 20 also discussed that ‘film, photos and music are the common language of all people in the world. If there is media uproar, the authorities will inevitably be forced to preserve the heritage. Promoting an elevated level of cultural expectations among Shiraz residents represents a critical tactic for fostering sustainable tourism growth in small heritage sites. Hospitality, openness, protection of sites and the preference of collective interests over individual were categorised under emotional support. In relation to this, Interviewee 2 discussed that ‘Shiraz community is always welcoming tourists. You take tourists to the artists; everyone welcomes them with open arms. Everyone enjoys introducing tourists to their art. Who wouldn’t enjoy this?’ Interviewee 9 similarly expressed that ‘as a citizen of Shiraz, I must be careful to protect the historical monuments of my city and have the zeal in me’. Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) and Moghavvemi et al. (Citation2017) have considered pride in the presence of tourists and pride in their interest in what the destination community has to offer in designing the construct of support for tourism development.

Intellectual leadership, research, education (children and social skills), media activities, intellectual and financial assistance, sponsors (content production, art events and research), storytelling, adherence to valuable actions, and awareness-raising conversations were several concepts derived from the data analysis and classified under voluntary promotional activities. From the interviewees’ point of view, these concepts can be utilised by the local community, especially non-governmental organisations and the private sector. Interviewee 1, for example, said, I have dedicated my potential to the children here to the best of my ability. I have talked to the kids about the paintings [my murals on the streets]. Now I have told my story, it is your turn to make it [the murals] into a postcard and sell it to a tourist. When he [the child] gets a taste of it, he will probably want to paint more, then I will encourage him to read ShahnamehFootnote1 and ask him to draw his own painting and give it to me to sell. Interviewee 4 expressed that ‘when I started here, I informed all the galleries and schools and told them that every artist from wherever they came from would stay in my art residency. I will be their sponsor’. In term of awareness-raising conversations Interviewee 12 said that ‘in our families, there is no familiarity with the past and exploration of the past. Mothers with information and interest in these topics can play a significant role’. Participation in cultural exchanges and education has been applied on the scale of supporting tourism development in some studies (Lee Citation2013; Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan Citation2018; Eslami et al. Citation2019).

Another strategy of the community to help the sustainable development of tourism is the user activities strategy. The concepts of attending in tours, visiting sites, producing content on a personal account, buying cultural products related to Shiraz, inviting acquaintances, and renovating houses for self-stay were categorised under this subcategory. Interviewee 9, for instance, discussed that ‘the spontaneous nucleus of the people for intra-city tours can create the context for familiarity with small heritage sites and the city’. Interviewee 22 similarly expressed that ‘my daughter has now become a heritage ambassador herself. I have worked on my family so that they can go and bring their friends. I take my friends from different cities to handicraft workshops and they buy there’.

Concepts of implementing creative ideas, using the potential of neighbouring communities, inventing new procedures/programmes, content production, events and festivals, specialised training, investment, fostering a culture of cooperative competition (coopetition), the protection of human values, a marketing approach, and proficiency in international languages are classified in the framework of the economic activities strategy. Interviewee 1, for example, said, I was looking forward to being able to create my own gallery, workshop and personal residence. Together they have an excellent output, in terms of executive appeal and in terms of showing my lifestyle to my audience. My audience should know that I eat this Sangak bread [referring to a type of traditional Persian bread] and create this work of art. Using the potential of neighbouring community in economic activities is considered a valuable tactic. Interviewee 4 mentioned that ‘the local criminals themselves can be among our agents. I can change the path of this criminal by defining a cultural and artistic programme and giving this person a responsibility’. Community proficiency in international languages can also help sustainable tourism development. Interviewee 19 also discussed that an ‘Isfahanian [a person from the neighbouring city of Isfahan] seller speaks English fluently with tourists, but this is not the case in Shiraz’. Olya, Alipour, and Gavilyan (Citation2018) and Lee (Citation2013) used the item of participation in plans and developments related to sustainable tourism in designing an SSTD questionnaire.

Consequences

The last part of the paradigm model is the consequences. Consequences arise whenever a person or people choose to do or not do an action or interaction in response to a problem or in order to manage or maintain a position (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). Three subcategories of economic, social and environmental consequences were included in this category. The concepts of earning income, increasing the value of assets and job creation were categorised under the subcategory of economic consequences. Interviewee 15, for instance, argued, The more tourists we have, the more people get out of poverty. For example, imagine I am poor, and I am the neighbour of your home, which has been turned into tourist accommodation. You give my child the opportunity to work at your business and my child earns money. Then my house consequently will be a better place. The concepts of national and international credibility, vitality of society, national identity, cultural exchanges and cultural impacts were categorised under the subcategory of social consequence. Interviewee 13 said, ‘I know families in the historical district who took tourists to their home without any financial expectation and gave them dinner and talked to them. These families could speak very little English. It was very interesting to me how cultural exchange was taking place. Tourists entered the family institution’. The concepts of changing the face of the city, preserving the historical district and destroying the originality of some buildings were included in the subcategory of environmental consequences. Interviewee 17 expressed that ‘when people conclude that a monument is their national identity, not a soulless object, they try to preserve it as an asset for their children’. Interviewee 1 also thought that ‘some accommodations change the taste of the tourist in the long run. They make superficiality common in art. Because they are purely materialistic, they destroy the originality of the historic house in order to attract more tourists’.

Selective coding

After open and axial coding, selective coding was performed to connect the categories to design the theory. demonstrates community SSTD as a major phenomenon. In this model, the contextual conditions for community support are stability, migration and artistic potential in Shiraz., attitudes, rules and policies, public education and efficient management of small heritage sites are influential as intervention conditions. The community – being in the above conditions and under the influence of cultural/historical awareness, individual characteristics, community perceptions, community attachment, social factors and the neighbourhood condition of the sites – adopts strategies of demand, emotional support, economic activity, voluntary promotional activities and user activities, and as a result of applying these strategies, economic, social and environmental consequences are achieved.

Conclusion

Many people in communities living near small heritage sites are concerned about preserving and restoring these valuable places for themselves and future generations. This noble concern has led us to investigate the role of the local community in developing sustainable tourism based on the potential of these sites, with a focus on ‘community support’. After reviewing previous research, we discovered that most studies only identify the influencing factors on community support through quantitative research. Additionally, community support has only been considered in the development of urban, rural, and world heritage tourism, and they have measured the intention to support or attitude to support tourism development (as a dependent variable) with a few limited items.

This literature gap has motivated us to investigate the process of community support for sustainable tourism development in small heritage sites. Specifically, we aim to determine the dimensions of this support and the prerequisites and context necessary for its fulfilment. This study makes a theoretical contribution by presenting a grounded theory model of community support for sustainable tourism development (SSTD) in small heritage sites. In this context, community SSTD refers to a collection of demanding behaviours, emotional support, and promotional, economic, and user activities undertaken by community members to achieve economic and social benefits from small heritage sites. This approach also emphasises the importance of preserving and revitalising these sites for future generations.

Moreover, this research enhances our understanding of the context of Iranian cultural and heritage tourism by studying the structure and process of community SSTD in Shiraz, one of the most well-known historical and cultural tourism destinations in Western Asia. The findings shed new light on the causal, intervention, and contextual conditions of the phenomenon of community SSTD in small heritage sites, including subjects such as individual values, immigration, and the art potential of a region. This study is significant because it fills gaps in the literature of community SSTD and provides insights into the unique cultural and heritage tourism context of Iran. Overall, our research on small heritage sites in Iran can contribute valuable insights to international heritage research and promote a better understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with preserving and promoting cultural heritage in different contexts.

It also contributes to the development of effective strategies and policies for sustainable tourism development in small heritage sites by identifying the key factors and dimensions of community support. The practical contribution of this study is to provide stakeholders of small heritage sites with a tangible and objective understanding of the construct of community SSTD. Local decision makers and non-governmental organisations in the field of cultural heritage are among the key stakeholders of small heritage sites. By studying the process of community SSTD formation in small heritage sites, decision makers of cultural heritage tourism can adopt a systematic viewpoint and avoid making partial decisions with a short-term perspective. By understanding the dimensions that influence community support, policy makers can tailor their approaches to address the specific needs and concerns of local communities, while also promoting the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage. Additionally, our findings can help policy makers design and implement community engagement programs that foster a sense of ownership and empowerment among local residents, leading to greater participation and support for tourism development initiatives.

For instance, enhancing community members’ understanding of the historical and cultural importance of small heritage sites could increase their support for economic activities related to these sites, provided that suitable policies for site usage and investment risk reduction are established by relevant organisations. This study can also be useful for non-governmental organisations working in the cultural heritage sector, as it provides insight into audience segmentation and suggests appropriate strategies to encourage community support. For example, an NGO can organise educational programs and workshops to raise awareness among the local community about the cultural and historical significance of small heritage sites. They can also collaborate with local schools to incorporate heritage education into the curriculum. Therefore, NGOs can play a crucial role in facilitating community support for sustainable tourism development of small heritage sites by raising awareness, involving the community in planning, and promoting cultural events that benefit both the heritage site and the local community. Overall, this study provides practical guidance to stakeholders of small heritage sites to foster community support for sustainable tourism development and contribute to the preservation and revitalisation of these valuable sites for future generations.

While this study offers valuable insights into the dimensions of community support for sustainable tourism development in small heritage sites in Shiraz, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic challenges faced by tourism business owners and the local community created difficulties in eliciting their views on the topic of support. Many interviewees expressed concerns about the broader challenges facing tourism development in the region, which required the interviewer to steer them back to the main topic of the study.

Nevertheless, this study lays the groundwork for further research in this area. Based on the dimensions identified in this study, future research could focus on developing a scale to measure community support for sustainable tourism development in small heritage sites. Additionally, given the study’s focus on a historical city in an Eastern culture, similar qualitative studies could be conducted in other cultural contexts to enable comparisons and enhance the generalisability of findings.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest to report for this study.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fereshteh Pezeshki

Fereshteh Pezeshki holds a PhD in Marketing from University of Yazd. Her current research interests include sustainable tourism development, tourist behaviour and heritage tourism marketing.

Masood Khodadadi

Masood Khodadadi, PhD, is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Tourism and Events Management at University of the West of Scotland. He specialises in policy, planning and heritage aspects of tourism studies.

Moslem Bagheri

Moslem Bagheri is an Associate Professor in the Department of Tourism and Hospitality Management at Shiraz University, Iran. His principal research interests are in tourism planning, human resource management in tourism and hospitality and tourist behaviour.

Notes

1. The Shahnameh or Shahnama is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 ce and is the national epic of Greater Iran.

References

- Aremu, D. A. 2014. “Heritage Sites Management and Tourism Development in Nigeria.” Journal of Tourism & Heritage Studies 3 (1): 18–28.

- Backman, K., and H. A. Kyngäs. 1999. “Challenges of the Grounded Theory Approach to a Novice Researcher.” Nursing & Health Sciences 1 (3): 147–153. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2018.1999.00019.x.

- Bartelmus, P. 1986. Environment and Development. Boston: Allen and Unwin.

- Boley, B., and M. Strzelecka. 2016. “Towards a Universal Measure of Support for Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 61: 238–241. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2016.09.001.

- Byrd, E. T. 2007. “Stakeholders in Sustainable Tourism Development and Their Roles: Applying Stakeholder Theory to Sustainable Tourism Development.” Tourism Review 62 (2): 6–13. doi:10.1108/16605370780000309.

- Cárdenas, D. A., E. T. Byrd, and L. N. Duffy. 2015. “An Exploratory Study of Community Awareness of Impacts and Agreement to Sustainable Tourism Development Principles.” Tourism and Hospitality Research 15 (4): 254–266. doi:10.1177/1467358415580359.

- Demirović Bajrami, D., A. Radosavac, M. Cimbaljević, T. N. Tretiakova, and Y. A. Syromiatnikova. 2020. “Determinants of residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: Implications for Rural Communities.” Sustainability 12 (22): 9438. doi:10.3390/su12229438.

- Dudley, E. 1993. The Critical Villager: Beyond Community Participation. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203311707.

- Dutt, C. S., W. S. Harvey, and G. Shaw. 2018. “The Missing Voices in the Perceptions of Tourism: The Neglect of Expatriates.” Tourism Management Perspectives 26: 193–202. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.004.

- Eslami, S., Z. Khalifah, A. Mardani, and D. Streimikiene. 2018. “Impact of Non-Economic Factors on Residents’support for Sustainable Tourism Development in Langkawi Island, Malaysia.” Economics & Sociology 11 (4): 181. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2018/11-4/12.

- Eslami, S., Z. Khalifah, A. Mardani, D. Streimikiene, and H. Han. 2019. “Community Attachment, Tourism Impacts, Quality of Life and residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 36 (9): 1061–1079.. doi:10.1080/10548408.2019.1689224.

- Fan, L. N., M. Y. Wu, G. Wall, and Y. Zhou. 2021. “Community Support for Tourism in China’s Dong Ethnic Villages.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 19 (3): 362–380. doi:10.1080/14766825.2019.1659283.

- Grimwade, G., and B. Carter. 2000. “Managing Small Heritage Sites with Interpretation and Community Involvement.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 6 (1): 33–48. doi:10.1080/135272500363724.

- Hall, C. M. 2019. “Constructing Sustainable Tourism Development: The 2030 Agenda and the Managerial Ecology of Sustainable Tourism.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27 (7): 1–17. doi:10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456.

- Hanafiah, M. H., M. R. Jamaluddin, and A. Riyadi. 2021. “Local Community Support, Attitude and Perceived Benefits in the UNESCO World Heritage Site.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 11 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1108/JCHMSD-03-2020-0034.

- Jani, D. J.-H., J., and H. Yeong-Hyeon. 2014. “Big Five Factors of Personality and Tourists' Internet Search Behavior.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 19 (5): 600–615.

- Kanwal, S., M. I. Rasheed, A. H. Pitafi, A. Pitafi, and M. Ren. 2020. “Road and Transport Infrastructure Development and Community Support for Tourism: The Role of Perceived Benefits, and Community Satisfaction.” Tourism Management 77: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104014.

- Kapera, I. 2018. “Sustainable Tourism Development Efforts by Local Governments in Poland.” Sustainable Cities and Society 40: 581–588. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.001.

- Khalid, S., M. S. Ahmad, T. Ramayah, J. Hwang, and I. Kim. 2019. “Community Empowerment and Sustainable Tourism Development: The Mediating Role of Community Support for Tourism.” Sustainability 11 (22): 6248. doi:10.3390/su11226248.

- Khodadadi, M., F. Pezeshki, and H. O’Donnell. 2021. “Small but Perfectly (In) Formed? Sustainable Development of Small Heritage Sites in Iran.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 17 (1): 74–90. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2021.1933992.

- Labadi, S., F. Giliberto, I. Rosetti, L. Shetabi, and E. Yildirim 2021. “Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Policy Guidance for Heritage and Development Actors. ICOMOS, March 21. https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2453/

- Lee, T. H. 2013. “Influence Analysis of Community Resident Support for Sustainable Tourism Development.” Tourism Management 34: 37–46. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.03.007.

- MacKenzie, N., and M. J. Gannon. 2019. “Exploring the Antecedents of Sustainable Tourism Development.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 31 (6): 2411–2427. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0384.

- Matteucci, X., and J. Gnoth. 2017. “Elaborating on Grounded Theory in Tourism Research.” Annals of Tourism Research 65: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.003.

- Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts. 2021. Tehran and Fars are at the Top of the Number of Visitors to Historical Monuments and Museums/Hafezieh the Most Visited Tourist Site. Available from: https://www.mcth.ir/news/ID/58653

- Moghavvemi, S., K. M. Woosnam, A. Hamzah, and A. Hassani. 2021. “Considering residents’ Personality and Community Factors in Explaining Satisfaction with Tourism and Support for Tourism Development.” Tourism Planning & Development 18 (3): 267–293. doi:10.1080/21568316.2020.1768140.

- Moghavvemi, S., K. M. Woosnam, T. Paramanathan, G. Musa, and A. Hamzah. 2017. “The Effect of residents’ Personality, Emotional Solidarity, and Community Commitment on Support for Tourism Development.” Tourism Management 63: 242–254. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.021.

- Mothersbaugh, D. L., D. I. Hawkins, S. B. Kleiser, L. L. Mothersbaugh, and C. F. Watson. 2020. Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Nunkoo, R., and H. Ramkissoon. 2011a. “Developing a Community Support Model for Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 38 (3): 964–988. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.017.

- Nunkoo, R., and H. Ramkissoon. 2011b. “Residents’ Satisfaction with Community Attributes and Support for Tourism.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 35 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1177/1096348010384600.

- Olya, H. G., H. Alipour, and Y. Gavilyan. 2018. “Different Voices from Community Groups to Support Sustainable Tourism Development at Iranian World Heritage Sites: Evidence from Bisotun.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26 (10): 1728–1748. doi:10.1080/09669582.2018.1511718.

- Pirnia, H., A. E. Ashtiani, and A. A. Taheri. 2016. History of Iran. Tehran: Ravniz.

- Rao, U. 2009. “Caste and the Desire for Belonging.” Asian Studies Review 33 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1080/10357820903362951.

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., C. M. Ringle, M. Jaafar, and T. Ramayah. 2017. “Urban Vs. Rural Destinations: Residents’ Perceptions, Community Participation and Support for Tourism Development.” Tourism Management 60: 147–158. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.019.

- Rokeach, M. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York: The Free press.

- Seyfi, S., C. Michael Hall, and E. Fagnoni. 2019. “Managing World Heritage Site Stakeholders: A Grounded Theory Paradigm Model Approach.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 14 (4): 308–324. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527340.

- Sheldon, P. J., and T. Abenoja. 2001. “Resident Attitudes in a Mature Destination: The Case of Waikiki.” Tourism Management 22 (5): 435–443. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00009-7.

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

- Stumpf, T. S., J. Sandstrom, and N. Swanger. 2016. “Bridging the Gap: Grounded Theory Method, Theory Development, and Sustainable Tourism Research.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24 (12): 1691–1708. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1149183.

- Talebian, M. H., M. Pour Ali, and S. Khasipour. 2021. Immovable Cultural Heritage of Iran. Iran: Golden Cup Publishing.

- Tosun, C. 2001. “Challenges of Sustainable Tourism Development in the Developing World: The Case of Turkey.” Tourism Management 22 (3): 289–303. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00060-1.

- UNESCO. 2021. ”UNESCO Country Page”. Aceesses 2 May. https://www.unesco.org/en/countries/ir

- Wang, M., J. Jiang, S. Xu, and Y. Guo. 2021. “Community Participation and Residents’ Support for Tourism Development in Ancient Villages: The Mediating Role of Perceptions of Conflicts in the Tourism Community.” Sustainability 13 (5): 2455. doi:10.3390/su13052455.

- Woo, E., H. Kim, and M. Uysal. 2015. “Life Satisfaction and Support for Tourism Development.” Annals of Tourism Research 50: 84–97. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2014.11.001.

- Xie, P. F., M. Y. Lee, and J. W. C. Wong. 2020. “Assessing Community Attitudes Toward Industrial Heritage Tourism Development.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 18 (3): 237–251. doi:10.1080/14766825.2019.1588899.

- Yu, W. 2015. Study on Influence of Jiangping Town Residents, Sense of Place on Positive Attitude to Tourism, 24–27. Nanning: Guangxi University.

- Yu, C. P., S. T. Cole, and C. Chancellor. 2018. “Resident Support for Tourism Development in Rural Midwestern (USA) Communities: Perceived Tourism Impacts and Community Quality of Life Perspective.” Sustainability 10 (3): 802. doi:10.3390/su10030802.

- Zamfir, A., and R. A. Corbos. 2015. “Towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Urban Areas: Case Study on Bucharest as Tourist Destination.” Sustainability 7 (9): 12709–12722. doi:10.3390/su70912709.

- Zhang, Y., J. H. Chan, Z. Ji, L. Sun, B. Lane, and X. Qi. 2020. “The Influence of Community Factors on Local entrepreneurs’ Support for Tourism.” Current Issues in Tourism 23 (14): 1758–1772. doi:10.1080/13683500.2019.1644300.

- Zhu, H., J. Liu, Z. Wei, W. Li, and L. Wang. 2017. “Residents’ Attitudes Towards Sustainable Tourism Development in a Historical-Cultural Village: Influence of Perceived Impacts, Sense of Place and Tourism Development Potential.” Sustainability 9 (1): 61. doi:10.3390/su9010061.