ABSTRACT

This article explores contemporary threads in the heritage history of Aotearoa New Zealand, as we witness in real-time the emergence of alternative narratives of Indigenous heritage, in contrast to those of Western dominated modernity and colonial hegemony. Moves to actively decolonise heritage studies is creating shifts in the bicultural understanding of culture and heritage to overtly include place heritage. As this new framing emerges, wider acknowledgement of the significance of Māori heritage landscapes is growing. This is explored here in a series of four case-studies. Each account illustrates how Indigenous Māori voices have gained momentum, and reinforces how Aotearoa New Zealand is transitioning to greater bicultural appreciation through inclusion, changes in social and cultural conventions, and new interpretations of dominant narratives using tools like critical heritage studies and existing legal conventions. This evolution of heritage values is not without repeated contestation, however. Positively, increasing numbers of settler-Pākehā (non-Māori) as well as those colonised, no longer believe or accept the histories previously told. Much needed, robust, and sometimes difficult discussions are taking place, enabling New Zealanders to reconsider the significance of what heritage means to all its people.

Introduction

This article reflects changing understandings of heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand, from a Western-centric outlook to a bicultural one that increasingly includes Indigenous Māori perspectives. This rebalancing from primarily non-Māori – that is, white (Pākehā) settler interpretations – focuses on place rather than built heritage. Aotearoa New Zealand is constitutionally bicultural through the Treaty of Waitangi 1840, which enacted a national partnership between all Māori and the British Crown and is increasingly a tenet of contemporary society in which Māori voices are more equally heard, respected, and acknowledged. Until recently, however, the reality has been a dominant colonial process which failed to recognise the heritage values of Māori culture that preceded European settlement. This continues today. North American scholars have some familiarity with the Aotearoa New Zealand idea of biculturalism through the seventeenth-century Treaty agreement between the Native American Haudenasaunee confederacy and Dutch traders, known as the Haudenasaunee Two Row Wampum-Covenant Chain (Hill and Coleman Citation2019). It is apposite to explore instances of this process of bicultural re-orientation at a period when Aotearoa New Zealand and other Western ‘nations have begun to debate who, how and what they choose to remember and forget’ (Kidman et al. Citation2022, 7). As non-historians, our current interests are related to the intersection of heritage values and how Indigenous New Zealanders’ relationship to place reconfigures the national understanding of the heritage significance of the natural environment.

The two authors are sociologists and New Zealanders of European (Pākehā) descent. Emma Passey emigrated from England in 2002, whilst Edgar Burns was born and raised in regional Aotearoa New Zealand with about twenty five percent of the region’s population being Māori. Born and raised in different countries but now both New Zealand residents, we bring emic and etic Pākehā views endorsing the bicultural re-valuing and re-weighting of what is Aotearoa New Zealand’s heritage from our non-Indigenous perspectives. This paper explores our evolving joint position, and we discuss four cases which illuminate shifting understandings of what counts as heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand today.

These contemporary cases document the ongoing active incorporation of Māori perspectives in broadening respect for these sites as cultural taonga (treasures) and enabling Indigenous oversight in managing these sites of significance for Māori. In both legislation and public discourse, consultation with Māori governance bodies is increasingly mandated, expected and welcomed by many Pākehā and Māori, actively changing culture. Attestations by Māori of the high cultural value of each of these places has long contested existing dominant framing of what colonial-settler white society said was heritage, but change has only come recently. The present discursive shifts only seem surprising within hegemonic white discourse. These four successful examples for change place anchors for exploring how the beliefs and knowledge of Aotearoa New Zealand’s white population is changing.

In the first case study, we compare visual cues showcasing traditional Pākehā settler understandings of heritage in relation to new bicultural appreciations at Maungawhau – Mount Eden in Auckland. The second example discusses the regeneration ambition for the natural landscape at Lake Whatumā in Central Hawke’s Bay. Plans are being co-designed by local Māori and statutory bodies, demonstrating a bicultural approach to managing heritage places. The third example reflects on ignored and erased heritage at Ihumātao in South Auckland, comparing Pākehā interpretations of heritage with that of resident mana whenua hapū (Māori groups with jurisdiction over land or territory). Our final case study highlights the joint commitment by the Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) a Hawke’s Bay tertiary institution, and local mana whenua hapū joining with other local statutory bodies. This engagement is advancing a new awareness of bicultural heritage in academic programmes and amongst the community.

Changing Aotearoa New Zealand, changing heritage

Our interest in the changing heritage perceptions of New Zealanders has developed for several reasons. First, our country’s national name is today often spoken of as ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’ not simply ‘New Zealand’. In June 2022, Te Pāti Māori (The Māori Party, a political party) submitted a petition to New Zealand’s national Parliament calling for the country to be renamed Aotearoa (Dexter Citation2022) in recognition of a te Reo Māori name and others suggest Aotearoa New Zealand in recognition of a new bicultural appreciation. The suggestion of a name-change along with considerations of new ways to acknowledge the cultural identity of Indigenous citizens and Indigenous heritage values, are taking place in real-time and within contemporary debates. Elsewhere, other countries have also changed their names. Zimbabwe was Rhodesia and Ceylon returned to Sri Lanka for example, as they sought to represent dominant Indigenous populations more appropriately or remove references to colonialism illustrating how various bicultural national approaches can be open to ongoing revisions of what heritage means.

Second, as non-historians our reasons for exploring our national history start from listening to a re-telling of Aotearoa New Zealand’s history by Māori. Both this national place – Aotearoa New Zealand – and the idea of heritage are replete with layers of shifting meanings influenced by history, culture and geographic settings that produce versions of the heritage of this antipodean, South Pacific place (Winter Citation2013). It is barely 250 years since Europeans began colonising Aotearoa New Zealand, which until then was occupied by Māori spread throughout the two main islands, the last temperate landmass to be occupied by humans.

Third, despite Māori and the British Crown signing Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) in 1840, the intent of the Treaty is often questioned. Despite initially signalling a bicultural commitment of partnership, protection and participation, in 1975 the Waitangi Tribunal was established to hear longstanding grievances about negative impacts of colonialism on Māori and to consider claims of Treaty breaches. These internal reasons find global echoes and corollaries in colonised countries elsewhere, such as the forced displacement of first nations people in America, Canada, and aboriginal Australians. Hegemonic narratives of linear modernising Western histories fail to explain the racialised and environmentally extractive practices that exploited forest, farmland, and fauna in Aotearoa New Zealand as elsewhere. Consequently, many people – both Māori and Pākehā no longer believe the supposed truth of previously unproblematised white settler history.

Fourth, trends show that among other influences shaping our perspectives of heritage have been the cultural perceptions of the colonising population’s settler processes overrunning another people and disregarding, or actively destroying, places and things held to be important (Belich Citation2009). Today, in Aotearoa New Zealand and other settler societies, a reappraisal is challenging this dominant Western-centric orthodoxy of what counts as heritage. A recent example is Campbell’s (Citation2021) three-step re-telling of Aotearoa New Zealand’s agriculture history: initial Māori land use in the thirteenth century, replaced in the nineteenth – twentieth centuries by modernist farming and productivist monocultures, which in turn is currently being fractured by pressures of environmental and climate change, public opinion, and animal welfare concerns.

Converging changes influence this shift in awareness and appreciation of what counts as heritage. First there is the incipient shift from Western-dominated modernity. Emerging global powers in the present century have historical consciousness going back many thousands of years. Second, the internal unbundling of the self-certainties of European global imperial projects of the seventeenth-nineteenth centuries have a corresponding though uneven process of challenge and review of artefacts and collections of trophies from the continents and countries from which they were ‘collected’. There is a steady litany of calls for repatriation of objects such as the human remains of Māori which were held at the Pitt Rivers Museum in England and returned to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 2017 (Gilyeat Citation2019; Horwood Citation2019). It is not just about reclaiming heritage objects of cultural significance, however. Aotearoa New Zealand’s museums have long engaged Māori to change interpretations of heritage collections, co-design exhibitions, develop culturally appropriate practice in collection care and documentation, and to actively challenge conventional ideas about what decolonisation means in the context of museums and heritage collections. Third, the existential threat of climate change is forcing a realisation of species unity that erodes claims of civilisational superiority. Most shifts are incomplete, finding resistance from nations and individuals well-served by current societal configurations, economic gain and memory.

In making assessments about heritage values, changing priorities have given rise to critical heritage perspectives standing apart from previous dominant narratives, implied in phrases such as ‘It is the winners of history who write history’. The incorporation of subaltern perspectives contesting interests, and challenges to institutional collections, however, does not mean a smooth transition to a new framing, rather the claims intertwine in an ethic of discomfort increasing pressure for change (Foucault Citation2000). The formally constituted institutions of heritage collections and storage adapt to shifting perceptions but are embedded in pressures to resist change given previous legislative remits. Often it is artists and authors seeking social change who bring political, social, and environmental issues into the public consciousness because their artistic freedom enables them to identify the edges of socio-cultural changes and the limits of cultural framing.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s national heritage entity, Heritage New Zealand, Pouhere Taonga (2022), previously the Historic Places Trust, describes itself as ‘the leading national historical heritage agency’ (Heritage New Zealand Citation2022). It manages and interprets various historic properties open to the public and keeps a register of heritage sites, undertakes heritage status assessment, and monitors heritage regulations for planning and site protection (McCarthy Citation2011). Today, Pouhere Taonga, and all national and statutory entities in Aotearoa New Zealand have Māori staff, Māori advisors, and Māori in governance positions. Other statutory bodies such as the Department of Conservation (DOC) also manage heritage places such as environmental reserves and National Parks. Heritage New Zealand is a Crown entity operating at arm’s length from government. Contrastingly, the DOC as a government department is also engaged in interpreting ‘place heritage’; in increasingly incorporating Māori-led perspectives DOC demonstrates in the real-time the substantive bicultural shift occurring. We operate in an environment marked by a growing interest in heritage, recognition of its social, cultural, environmental, and economic benefits to our country, and greater awareness of its importance to national identity. Even in this one country Newton (Citation2018) clearly shows there is much to dispute and re-evaluate. In commentating on Aotearoa New Zealand’s historical record and heritage traces, it is important to observe for international readers that even if full recognition and acknowledgement were to be given to Indigenous Māori as well as more recently arrived European settlers and others, the human population of these islands is generally considered to have a history of less than a thousand years (Walter et al. Citation2017). This is in marked contrast to the histories of many global heritage sites measured in millennia.

Aotearoa New Zealand today has an increasingly cosmopolitan multi-cultural, non-Māori and non-European population. A significant proportion of the Pākehā population continues to operate from a derivative sense of quasi-British/European self-identity and affiliation that sees heritage in terms of buildings such as cathedrals and structures of a bygone Europe. For some who emigrate to Aotearoa New Zealand this provides a sense of freedom from the proprieties and weight of Euro-centric history enabling the freedom for Pākehā to recognise Māori heritage in marae (traditional Māori gathering place), pā (fortified village) and other cultural manifestations on the landscape. Lähdesmäki, Zhu, and Thomas (Citation2019, 9) state that ‘One of the core concepts in Critical Heritage Studies is Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD), an idea initiated by Smith (Citation2006, 299)’. With this concept Smith referred to a heritage discourse that ‘takes its cue from the grand narratives of the Western national and elite class experience and reinforces the idea of innate cultural value tied to time depth, monumentality, expert knowledge and aesthetics’. There is much to unpack here (Kuutma Citation2009). (6) observed:

Heritage, itself a late-modern European conception and cultural phenomenon, is today actively implemented in policies globally; it has started to play an important role both in national and international culture-orientated politics from rather contradictory aspects—it serves the elites and general public to fuel national pride, whereas cultural traditions and suppressed history have become powerful tools for previously dominated regions or social strata. Thus, it remains continuously worthwhile to question who does heritage empower, or what the repercussions of (and impact on) collectives or individuals are in this process. When the dynamic nature of cultural expression becomes immobilised by the verbs ‘to preserve’, ‘to protect’, or ‘to safeguard’ utilised in the realm of cultural heritage politics, the contemporary scholarship of cultural criticism wants to unravel how heritage constitutes and eventually transforms culture.

Contemporary adherence to Treaty of Waitangi obligations has meant re-prioritising and re-valuing Indigenous places and sites so that Māori history, residence and sense of place is repositioned and honoured, rather than repressed (Wheen and Hayward Citation2012). The critical studies perspective adopts a position that is ‘meaning-centred’ focusing on social action (Blyler Citation1998), naming power and conflict as part of the business of heritage studies (Nilsson Citation2022). Every step in Aotearoa New Zealand’s transition to greater bicultural appreciation has heard complaints from some Pākehā about ‘changing things’ rather than seeing this as restoring iniquitous treatment of cultural taonga (treasure) from pre-colonial times (Kearns and Lewis Citation2019). Contentious changes in the recent past include introducing a telephone greeting such as a Māori language greeting ‘Kia Ora’,(hello) in a work setting, or geographic name changes from Mount Egmont to Taranaki (Murton Citation2012). At each step questions of inclusion versus appropriation require fresh examination and argument, and new information and thinking emerges in cultural and political life (Harris and O’Sullivan Citation2013). Lähdesmäki, Zhu, and Thomas (Citation2019, 1) set out a critical heritage studies standpoint as follows:

Scholarly research of cultural heritage has faced paradigmatic changes during the past few decades. These changes have occurred in part as a reaction to diverse social, political, economic and cultural transformations of societies and traditional foundations of nation states. Today’s world, characterized by networked agencies, global cultural flows, cultural hybridity and movement of people within and across borders, contextualizes the idea of heritage in new ways. It challenges its previous core function as a bedrock of monocultural nation-building projects, a continuation of elitist cultural canons, and as upholding Eurocentric cultural values. As a part of this transformation, consensual heritage narratives about the nation and national identity have been questioned and contested through various identity claims below and above the national narrative—and within it.

It is not our purpose to formally explicate the changing paradigm that a critical studies approach brings to thinking about heritage (Gentry and Smith Citation2019). Here our aim is to illustrate it. Extending our current field interests, we are conscious of these international heritage shifts. ‘On the ground’ change involves not only effort, work and discomfort in colonial geographies, but changed sensibilities and understanding particularly in metropolitan centres, as can be seen in many countries’ recent public disavowal of public statuary honouring imperial figures (Ballantyne Citation2021; Drayton Citation2019).

Evidence of this contemporary stream of disaffection includes the defacing and removal of statues and memorials. In Britain, protestors unceremoniously toppled the statue of Edward Colston erected in 1895, throwing the figure into Bristol harbour. This visually demonstrated active rejection of continuing to honour a person involved in the slave trade previously considered by some as important enough to be cast in bronze and set on a pedestal (Elkins Citation2022; Prescott and Lahti Citation2022). The defacing and deposing of memorials has become a global phenomenon paralleled by other cultural changes such as the Black Lives Matter movement, which sparked widespread anti-racism protests since the murder of US citizen George Floyd by police officers in 2020, and the removal of Confederacy statues (Benjamin et al. Citation2020). It also gathered momentum in Aotearoa New Zealand. In June 2020, in Auckland a statue of Sir George Grey a colonial Governor was defaced with the words ‘racist’ and ‘stop’ in red paint, and in June 2020 a memorial to Captain Hamilton was removed from the centre of the city that bears his name, after a local Māori kaumātua (elder) called for its removal (Kidman et al. Citation2022, 8). So too, demands from some to change colonial street names to better represent a broader understanding of Māori heritage. Von Tunzelmann states that statues and memorials are an easy target for protestors because they are the ‘embodiment of a once living and breathing person’ (cited in Kidman et al. Citation2022, 8).

Demonstrations against public figures illustrate shifting understandings of ways our histories are represented and by whom and ‘their greatly altered status serves as a reminder of how understandings of the past shift, sometimes slowly, at other times more rapidly’ (Kidman et al. Citation2022, 8). As Orwell (Citation1961, 31) surmised in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four ‘Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present controls the past’. Debates considering whose history we are representing by whom and for whom, are critical for contemporary bicultural societies.

A new respect for heritage can be achieved by descendants of imperial settlers through contemporary understandings of the contested domains of human remains, cultural artefacts and the elegant Māori word, taonga. Taonga is not about Western perspectives viewing ‘baubles’ of ‘ethnic’ interest and curiosity as an authorised paradigm supposed (Paterson Citation1999). Rather, taonga in plural and singular senses may include more conventional items also referencing weaponry, food, ceremonial, and status items. Equally, it refers to those things valued in the land – places and the sacred identities of mountains or natural formations. As litigation under the Treaty of Waitangi established, rivers have a value as water for drinking, washing, crops and as sources of food and transport. They also, however, have mana (authority; influence; prestige) as spiritually significant in and of themselves. Hutchison (Citation2014) described the process by which Aotearoa New Zealand’s Whanganui River came to be recognised as having legal personhood in 2017, as Māori have maintained all along, giving a more comprehensive expression of what taonga means. The Whanganui River is thought to be the first river in the world to be granted the same rights and responsibilities as a person, but other countries have since followed Aotearoa New Zealand’s innovative bicultural approach including India which granted personhood to the Ganges and Yamuna in the same year (O’Donnell Citation2017).

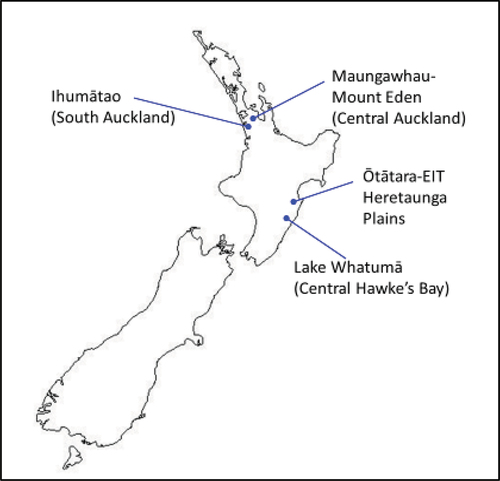

In this contemporary period of transitional heritage, the following examples () demonstrate current reappraisal and challenge to AHD – authorised heritage discourse – in Aotearoa New Zealand. These examples: Maungawhau-Mount Eden (Central Auckland), Lake Whatumā (Central Hawke’s Bay), Ihumātao (South Auckland), and Ōtātara-EIT (Taradale, Hawke’s Bay), represent places with differing challenges. We chronicle how they are now being managed in ways that advance a critical heritage discourse. The examples ground the wide sweep of this paradigm shift as a postcolonial era is being enacted in one settler society (Kawharu Citation2009).

What should heritage change mean in this country and what will future Aotearoa New Zealanders value in the country’s past as a more bicultural future is developed (Rowe Citation2022)?

Case study: Maungawhau-Mount Eden – visual cues of obsolete opinions and new understandings

In the changing environment of pre-European and post-European dominated worlds, re-thinking what heritage means is a significant part of updating national history and culture. How do we think our way through the specifics of this place and these aspects of our lived times to new and more inclusive frames? Maungawhau-Mount Eden is the highest extinct volcano in Tāmaki Makaurau (City of Auckland); it is one of fourteen tūpuna maunga (ancestral mountains) managed by The Tūpuna Maunga Authority. This statutory body, with equal membership from Ngā Mana Whenua o Tāmaki Makaurau (local Māori representatives) and Auckland City Council, was established in 2014 under the Ngā Mana Whenua o Tāmaki Makaurau Collective Redress Act.

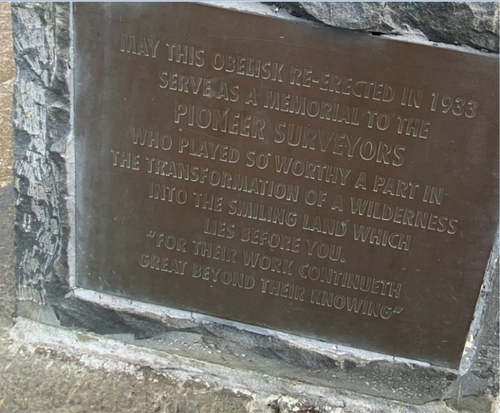

The mountain, commanding far-reaching views, is a popular destination for visitors (Arenas Citation2010). There is an obelisk and plaque at the top (see ).

Figure 2. A plaque on Maungawhau-Mount Eden, erected 1933 commemorating work of European surveyors. Source: Emma Passey.

The words of the plaque read as follows:

May this obelisk re-erected in 1933 serve as a memorial to the pioneer surveyors who played so worthy a part in the transformation of a wilderness into the smiling land which lies before you.

English surveyors thought clearing ‘a wilderness was an important task but failed to understand or acknowledge the cultural significance of the wider landscape that would become Auckland City. There are several visual cues, however, indicating that understandings of heritage are changing and because our first author is an English-trained surveyor, we were drawn further to exploring the changing discourses here.

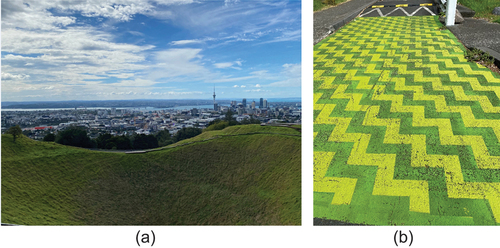

The experience of standing on the tūpuna maunga helps reflection on the paradigm shift in occurring in perceptions of heritage. In a second photograph shows the obelisk’s assertive pose on the edge of the hollow cone facing Auckland’s Central Business District (CBD) but not the kūmara (sweet potato) pits of an active pre-European settlement. These are not clearly signposted for visitors who may not recognise these landscape features for their heritage value. Instead, they are only a visual hint of the cultural significance of this land to Māori. What is erased or a mere trace seems eloquent. A different eloquence to the placing and date of the plaque as a settler assertion that this is history.

Figure 3. (a) Looking across the volcanic cone toward Auckland CBD; (b) Use of Māori imagery in road markings at Maungawhau-Mt Eden. Source: Emma Passey.

In contrast, our final observation on this case study in shows recent visual acknowledgement of a bicultural history apparent in modern road markings incorporating traditional Māori designs alongside conventional non-Māori ones. This distinctive imagery and the dual use of te Reo Māori (Māori language) and English language names on signage are being engaged by the Tūpuna Maunga Authority. At the time of visiting, the authors found that there was an absence of distinctive signage explaining the Māori heritage value of the tūpuna maunga. The use of imagery does, however, go some way to acknowledge bicultural heritage within plain sight, illustrating a subtle public shift occurring in heritage understanding (Vermeulen Citation2011).

Case study: Lake Whatumā, Waipukurau – a co-design approach between local Māori and local government

The Lake Whatumā Management Group comprising local hapū members currently manage Lake Whatumā in Waipukurau Central Hawke’s Bay, following the outcome of a Treaty of Waitangi Settlement. The 160-hectare lake, with a wetland margin of half that area again is the drainage point in a catchment basin of some 5,400 hectares (HBRC Citation2018). It is a fundamental part of the Tukituki River catchment area, is ‘a taonga or cultural treasure of great significance’ (HBRC Citation2018, 3), and has been utilised by several hapū over centuries. Currently, a draft plan which is not currently public is being co-designed between Māori leaders and the local community recommending how the ecology of the lake and surrounds could be regenerated, and cultural heritage celebrated more prominently.

Statutory bodies including the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council (HBRC), the Central Hawke’s Bay District Council, and the DOC have differing and sometimes conflicting statutory responsibilities relating to the management of the hydrology, ecology, and cultural heritage of the area. Specifically, the HBRC has responsibility for increasing and protecting biodiversity, water management and flood protection, pollution control, and environmental management and planning. Whilst these activities do not address cultural heritage protection per se, they inevitably form part of the work. Legislation within which all statutory bodies work, such as the Resource Management Act 1991, places obligations to uphold the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. This means that HBRC reports now highlight the range of cultural heritage values and HBRC’s bicultural approach to managing this place.

An example of management challenges faced here is the curious ownership history that has occurred due to European settler surveyors drawing boundary lines across the lake. The lake is not directly connected to either the nearby Tukituki or Waipawa rivers; Lake Whatumā dries up intermittently. Mid-nineteenth-century land acquisition by the Government for white settlers involved issuing legal titles into the centre of the shallow water body. Recently, duck shooters collectively bought a portion of the middle of the lake without legal access except through neighbouring properties. This situation illustrates consequences of settler surveyors determining legal boundaries but failing to consider all contributing factors to landscape characteristics, including cultural heritage and ecology. It also connects back the previous example’s hubris placing the surveying monument at Maungawhau. This in turn links to consequences, intended or not, of arbitrary boundary lines in the next example of Ihumātao. At every turn, we all have a responsibility to think of others’ cultural heritage and appropriately acknowledge it.

As an example of adopting a bicultural approach to environmental management, HBRC undertook an investigation into outstanding water bodies (OWB) which includes Whatumā. The subsequent HBRC report shows a more ancient history and heritage that has lacked recognition and accommodation by previous settler-influenced statutory bodies, but this is changing (HBRC Citation2018, 9). In the HBRC OWB report (HBRC Citation2018) several pictures illuminate the historic and archaeological heritage of this place for both settler Europeans and Māori. , for example, shows the scope for re-thinking a bicultural heritage.

Figure 4. Archaeological sites at Lake Whatumā – approximately 1.5km in length. Source: HBRC (Citation2018), 9.

It does not take a lot of imagination to look at the archaeological sites around Lake Whatumā (see ) and mentally reconstruct the thriving population, permanent and seasonal, accessing the lake and soils in both European earlier Māori settlement eras. It is a positive move that the local statutory bodies such as HBRC, Central Hawkes Bay District Council and the DOC, in applying their individual remits for heritage are today formally acknowledging Māori cultural heritage values in this landscape. Meshing with this continuing shift is the Government’s enactment of the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019, committing to reducing carbon emissions and improving the environment. A new Māori governance committee serve as environmental and cultural kaitiaki (guardians) of Whatumā. This fits with protecting, and cleaning waterways, high on the national agenda, with new funding for wetland restoration and management (Taylor Citation2020).

Whilst management plans for Lake Whatumā have previously been developed, conflicts of interests between landowners, traditional owners, recreational users, and statutory bodies mean little has so far been achieved. However, restoring the lake and its associated biodiversity and cultural heritage, now on the political agenda, provide an opportunity for local councils and Māori leaders to simultaneously seek a revival of histories. Both face challenges as new historical evidence and the consequences of previous actions continue to be examined and worked through, particularly since multiple actors have their own interests in the lake. These groups may need to be supported in their understanding and acknowledgement of alternative histories, which may not have been recorded, documented, or shared previously but which are no less relevant than those that have already been publicly told and presumed to be the simple facts of the Whatumā heritage story.

Case study: Ihumātao, South Auckland – biased institutionalised heritage

Ihumātao is a 30-minute drive from Auckland Central Business District and the Auckland International Airport is close-by. It covers approximately 100-hectares – the last remnant of several thousand hectares of historic gardening sites across the Auckland isthmus. This culturally and historically important landscape serves as another contemporary example of conflicting opinions over the heritage value of place. It is also another instance where after land confiscation, Europeans surveyed lines across fields with no care for how the wider landscape linked – environmentally, culturally, and historically. There has been several years of protest over proposed new commercial property developments here (Newton Citation2018) with tensions developing between some Māori who want to conserve the land protecting its cultural heritage, and others who believe that the acute need for housing in the region outweigh the interpretation of what is heritage (Mackintosh Citation2019, Citation2021).

The first human settlement at Ihumātao is thought to have been around 800 years ago followed by Polynesians between 1300 and 1350 (Veart Citation2016). Local families (iwi) also believe it to be the place where Hape, a significant Māori ancestor arrived on a stingray and greeted the Tainui waka (ancestral canoe). This account describes Tainui people as the first Māori settlers here from a distant Hawaiki (originating home in some Māori narratives), giving it important cultural and historical links to the first settlers of Auckland (Hayden Citation2017). Māori were kaitiaki (guardians) of Ihumātao, and from 1769 when the first Europeans arrived, they worked together with Pākehā to create ‘the food bowl of Auckland’ (Veart Citation2016), developing a thriving trading base (O’Malley Citation2016, 35). However, in 1863 ‘the biggest and most significant war ever fought on Aotearoa New Zealand shores’ (O’Malley Citation2016, 9) took place; it is often referred to today as the ‘New Zealand Land wars’. Fighting was over access to, control of, and ownership of land between the European newcomers and existing Māori inhabitants.

Subsequently, as shows in an early twentieth-century aerial photo, the land seized at Ihumātao by the Government went to European farmers who introduced stock, fences, drainage systems and extensively ploughed the land and quarried its hillsides (Veart Citation2016). This 1930s photograph predates further destruction of the site being quarried. It still shows the historic stone-fenced garden plots. shows visible remains cover an area greater than a square kilometre in the north coastal part of the map. Originally, these gardens extended further inland and were coterminous with gardens southward up to and beyond the volcanic cone and pā site of Maungataketake two to 3 km away. Maungataketake has been literally quarried to a hole in the ground by settler landowners.

Figure 5. Before quarrying, Ihumātao’s historic-stone-edged gardens, 1-2km across, 1930s. Source: Veart (Citation2016).

As the dominant heritage narrative began to shift, it was anchored by a series of archaeological projects and reports which had been brought together in 1983 (Rickard, Veart, and Bulmer Citation1983). Stone structures were mapped all the way from the northern coast by Waitomokia to Maungataketake (p. 22). Cleared stone fences for farming on eastern slopes were by then ‘absent’ data.

In the present century an Environmental Justice Group, SOUL (Save Our Unique Landscape) was established to stop corporate housing development. Part of the landscape, the Ōtuataua Stonefields Reserve, had gained heritage protection for its historical, cultural, and ecological values but the area earmarked for housing development referred to as Special Housing Area 62 (SHA62) was not. This was despite the entire locale being listed on the United Nations International Council on Monuments and Sites register as being at-risk (Doyle Citation2019). SOUL claimed the areas should be considered as one continuous heritage landscape because boundary lines between the Ōtuataua Stonefields Reserve and SHA62 were simply artefacts of European surveying in 1866 carving up the culturally rich area (Ihumātao Citation2022). Pania Newton’s leadership to ‘Not one more acre’ of Ihumātao exemplifies the long and difficult contestation processes – amongst Māori, and between Māori and some Pākehā, bringing fairer and more accurate heritage perspectives to Aotearoa New Zealand (Awarua Citation2022).

SOUL maintained that the history and significance of these events has until recently been inadequately told and respected because of Aotearoa New Zealand’s biased institutionalised heritage. Indeed, elsewhere across the country there continues to be difficult conversations as communities begin to question with greater vehemence, different narratives, and heritage values of the same past events. As these alternative interpretations gather support and pace, other communities begin to find their voices to protect their taonga and heritage. While chronicling recent and rapid political and historical changes is difficult, seeing the Ihumātao changes captured in pictures is striking. Again, the surveying presumption of turning wilderness into ‘our’—meaning European settler or Pākehā, ‘productive’ landscape – permeates non-Māori history resisting recognition of Māori affinities and historical identities in the landscape. However, in 2020 the heritage listing of the Ōtuataua Stonefields Reserve was upgraded by Heritage New Zealand, including the contested land, bringing to recognition intangible histories of the Māori Indigenous people of the land, tangata whenua (University Citation2020).

The cases of Maungawhau-Mount Eden and Ihumātao illustrate how the physical geography of Auckland City has been shaped by the histories of Māori and Pākehā settlers but often split (Mackintosh Citation2019). suggests that Auckland city’s landscape reveals complex histories that are still not acknowledged. These need to be brought to light and reconsidered in the same way as more familiar prominent stories recognised by mana whenua and other Māori communities.

Case study: environment, cultural heritage and Ōtātara Pā—an institutional commitment

The Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) has several campuses across the east coast of Aotearoa New Zealand’s North Island. EIT recently committed to integrate the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (https://sdgs.un.org/goals) across the institution where possible. From teaching to research this encourages creative ways of thinking and new pedagogical practices (EIT Citation2022). An integral part of this sustainable approach is recognition and visual celebration of connections between environmental and cultural heritage values.

The campus adjoins the historic Ōtātara Pā (fortified Māori village) and Hikurangi Pā landscape, one of the largest and most significant pā in Aotearoa New Zealand’s pre-colonial history (Parsons Citation1997). In more recent settler times, Ōtātara was the site of two large European-style homesteads, since demolished, home to the Hetley family who gifted the land to the people of Hawke’s Bay for a university. The first campus building was named after the Hetley family in recognition of this European heritage. During the 1970s and 1980s EIT was home to the internationally renowned Ōtātara Arts and Crafts Centre. Not only did the Centre include the name Ōtātara acknowledging the importance of its location in this culturally significant landscape, but students explored both Māori and Pākehā arts (Morris-Matthews Citation2015). These layers of history celebrating both Māori and European heritage have increasingly influenced EIT’s bicultural framework ().

Figure 7. (a) the physical closeness of the Ōtātara landscape and EIT campus from Ōtātara Pā viewing platform; (b) View of the Ōtātara Pā viewing platform. Source: Emma Passey.

EIT has rich cultural and institutional histories and it is intended that this bicultural heritage is pivotal in the organisation’s future operation. In 2019, the Air New Zealand Environment Trust (AirNZET) and EIT signed a Memorandum of Understanding to work collaboratively with a range of local organisations, driving sustainability issues and strengthening capacity development for educators to gain skills, knowledge, and confidence to work with nature in the context of learning. This recognised mutual commitment to the intentions of the United Nations SDGs including SDG-eleven, promoting sustainable cities and inclusivity in communities. As part of the agreement, EIT and AirNZET funded the development stages of an outdoor area on the site of the previous Ōtātara Arts and Crafts Centre. It is known as the Ōtātara Outdoor Learning Centre (ŌOLC).

Funding was provided for ‘enriching existing educational programmes, developing new programmes, engaging with students, community groups, schools, and researchers’ (EIT Citation2019) to provide an environment where people can connect with local histories, culture and biodiversity and contribute to sustainability research (Viriaere and Miller Citation2018). This is being achieved through co-design of programmes and the co-management of the site between the original ŌOLC partners; Ngāti Pārau – the mana whenua hapū, EIT, the local Regional Council, the government DOC, and other community leaders (EIT Citation2019). This approach integrates natural environment and heritage values for people who live, work, and use this place.

This new focus prompted the establishment of a fixed-term position in 2018 later morphing into a role as Environment and Sustainability Manager for the first author in 2020. The ŌOLC was officially opened in November 2020 (EIT Citation2020) and the philosophies of the project are now being actively shared with high schools and other tertiary providers throughout Aotearoa New Zealand’s Te Pūkenga national polytechnic network. This educational engagement supports meeting the challenge of new heritage learning head-on by incorporating and highlighting, where possible, the intrinsic connections between cultural heritage and natural environment across the education curriculum from early childhood to all tertiary level subjects. A practical example of this has been the design and planting of a rongoā (Māori medicine) garden on campus. Students studying horticulture, mental health and nursing collaborate with Te Ūranga Waka (the school of Māori Studies) to design, plant and utilise the garden.

Reflection and conclusion

Although museums have long engaged Māori, we have shown through these recent case studies how Māori are regaining control over their heritage with supportive Government institutions and statutory authorities. Co-designing heritage management plans, supporting education and ensuring visual cues are more prominent in every-day life, a mixture of collaboration and contestation to achieve this more genuinely bicultural partnership is slowly being developed. As McCarthy, Hakiwai, and Schorch (Citation2019) noted, the Te Māori exhibition, which travelled internationally in 1984–85 is frequently considered to have been a landmark in changing ideas about taonga Māori. What had previously been categorised by academically trained anthropologist-curators as material culture, came to be seen and recognised by Māori and Pākehā as ancestral and living treasures of the highest significance. We have shared here emerging narratives of the changing understanding of place heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand through case studies referencing tools like critical heritage studies and existing legal arrangements. As critical heritage discourses emerge, many Pākehā New Zealanders now talk about heritage in terms of people and place rather than previous Western-dominated hegemony of heritage objects and buildings. We are also witnessing the emergence of bicultural visual cues at tourist places, on our road signage and the embracing of te Reo (Māori language) and tikanga (Māori protocols) in everyday interactions.

We see many good things that Pākehā society gains from association with te ao Māori (the Māori world view) but while some Pākehā appreciate Māori heritage, particularly in terms of the natural environment and place, this still sometimes tends to be an appreciation of convenience, such as when it does not constrain current activities – changing the course of a river or creating a dam to benefit farming husbandry, for example. It is both a personal and societal work-in-progress to go beyond simply appreciating Aotearoa New Zealand’s bicultural heritage, but to take the time to understand what this is and what it represents. Slowly over time the acknowledgement, respect and more comfortable interaction by a greater proportion of the Pākehā population makes those relations less exploitative, nudging society towards bicultural partnership, participation, and protection in understanding that all our histories and pasts form a mutual part of our present heritage.

The recent backdrop is of traditional heritage studies becoming more plural, inclusive, and open-ended. Potentially in the future new heritage practices can be instrumental enabling reconciliation for wider understanding and participation in Aotearoa New Zealand society. From a tool of reinforcing colonial hegemony to actively acknowledging this country’s bicultural diversity, this makes a better academic discipline, and better reconstructs our past to invite a fairer future. New things begin to surface in our case study examples. Heritage is not just about the old but the response of today in understanding our past, relearning what we have repressed or not previously listened to. Aotearoa New Zealand heritage is about people as well as place, and about place before it is about buildings. Heritage in a bicultural sense, is about giving priority to nature not simply colonial-settler institutions and objects: rocks marking transit, mountains holding mana and sacredness, rivers as persons – because that is sharing a Māori worldview not just a Pākehā-European one; future research from an Indigenous perspective will add significantly to this discourse.

An outflowing of new ideas grounded in this local antipodean place challenges conventional ideas of heritage. What in this country do ‘we’—Māori and Pākehā—want to draw from elsewhere? How might we respond and sometimes make use of that even as we chart our own local pathways, choices, and materials in our furthering our collective heritage? How do we work between known and unknown views, and work back in time to reconfigure this place as our heritage? Whilst there are ongoing questions and contestations as we shift our bicultural understanding of heritage as a nation, the institutional commitments in these case studies of a metropolitan urban authority, rural and regional and local authorities, and a tertiary education provider, seeing the heritage conjunction of Māori culture and environmental values, is a good omen for progress in a distinctly new Aotearoa New Zealand heritage. Perhaps this can also be a good omen for new understandings of contemporary bicultural heritage elsewhere?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emma Passey

Emma Passey was central in developing the Ōtātara Outdoor Learning Centre at the Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) in Aotearoa New Zealand, a cultural and environmental initiative, which won an Australasian Green Gown Award in 2021. Emma’s MA explored how Māori and Pākehā staff describe their campus sense of place, including historic and cultural values of Ōtātara, and her PhD research explores how a local rural community has developed environmental values through heritage, place, and nature connectedness.

Edgar A. Burns

Edgar A. Burns has taught in the polytechnic and university tertiary sectors in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. He takes an interdisciplinary approach starting from his core sociology teaching and research which includes environmental sociology, social ecology, and antipodean theory. In his present role, influencing attitudes about environment and climate are priorities.

References

- Arenas, N. 2010. Stakeholder Collaboration for the Development for Sustainable Tourism in Urban Green Spaces: The Case of Maungawhau-Mt Eden, Auckland, New Zealand. MSc, Wagingen University. https://edepot.wur.nl/150826.

- Awarua, A. 2022, 12 June. “Not One More Acre: Pania Newton on Ihumātao.” Woman+. https://womanmagazine.co.nz/not-one-more-acre-pania-newton-on-ihumatao/.

- Ballantyne, T. 2021. “Toppling the Past? Statues, Public Memory and the Afterlife of Empire in Contemporary New Zealand.” Public History Review 28:1–8. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v28i0.7503.

- Belich, J. 2009. Replenishing the Earth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Benjamin, A., R. Block, J. Clemons, C. Laird, and J. Wamble. 2020. “Set in Stone? Predicting Confederate Monument Removal.” Political Science and Politics 53 (2): 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519002026.

- Blyler, N. 1998. “Taking a Political Turn: The Critical Perspective and Research in Professional Communication.” Technical Communication Quarterly 7 (1): 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572259809364616.

- Campbell, H. 2021. Farming Inside Invisible Worlds: Modernist Agriculture and Its Consequences. London: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350120570.

- Dexter, G. 2022. “Petition to Official Name Country Aotearoa Delivered to Parliament.” RNZ Website. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/468391/petition-to-officially-name-country-aotearoa-delivered-to-parliament.

- Doyle, C. T. 2019. Resistance is Never Wasted—Defending Māori Cultural Heritage with Radical Planning. Dunedin, New Zealand: MA, University of Otago. http://hdl.handle.net/10523/9476.

- Drayton, R. 2019. “Rhodes Must Not Fall?” Third Text 33 (4–5): 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2019.1653073.

- EIT. (Eastern Institute of Technology) 2019. “Air New Zealand Trust and EIT Embrace Outdoor Learning.” https://www.eit.ac.nz/2019/06/air-new-zealand-environment-trust-and-eit-embrace-outdoor-learning/.

- EIT. (Eastern Institute of Technology) 2020. “EIT Celebrates Official Opening of the Ōtātara Outdoor Learning Centre.” https://www.eit.ac.nz/2020/11/eit-celebrates-official-opening-of-otatara-outdoor-learning-centre/.

- EIT. (Eastern Institute of Technology) 2022. “Integrating Sustainability Across EIT.” Eastern Institute of Technology Website. https://www.eit.ac.nz/research-innovation/sustainable-futures/integrating-sustainability/.

- Elkins, C. 2022. Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire. London: Random.

- Foucault, M. 2000. “For an Ethic of Discomfort.” In Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984, edited by J. Fabion, 443–448. New York: Free Press.

- Gentry, K., and L. Smith. 2019. “Critical Heritage Studies and the Legacies of the Late-Twentieth Century Heritage Canon.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11): 1148–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1570964.

- Gilyeat, D. 2019. “Pitt Rivers: The Museum That’s Returning the Dead.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-45565784.

- Harris, H., and J. O’Sullivan. 2013. “The Importance of Understanding Māori Greetings to Doing Business in Aotearoa/New Zealand.” Australia New Zealand Academy of Management Conference, 1–12. 4-6 December, Hobart, Tasmania. https://www.anzam.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf-manager/188_ANZAM-2013-407.PDF.

- Hayden, L. 2017, 7 December. “Bringing the Fight for Ihumātao to K Road.” The SpinOff. https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/07-12-2017/bringing-the-fight-for-Ihumātao-to-k-road/.

- HBRC. (Hawke’s Bay Regional Council) 2018. “Lake-Whatumā-Candidate-OWB-Report.” https://www.hbrc.govt.nz/assets/DOCument-Library/Projects/Outstanding-Water-Body/Lake-Whatuma-candidate-OWB-report-201807111.pdf.

- Heritage New Zealand. 2022. “About Us.” Heritage New Zealand Website. https://www.heritage.org.nz/about-us.

- Hill, R. W., and D. Coleman. 2019. “The Two Row Wampum-Covenant Chain Tradition as a Guide for Indigenous-University Research Partnerships.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 19 (5): 339–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708618809138.

- Horwood, M. 2019. “Museum Encounters—Ngā Paerangi Travel to Oxford.” In Sharing Authority in the Museum, 42–68. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351251129-3.

- Hutchison, A. 2014. “The Whanganui River as a Legal Person.” Alternative Law Journal 39 (3): 179–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969x1403900309.

- Ihumātao, P. 2022. “History.” Campaign Website. https://www.protectihumatao.com/the-campaign.html.

- Kawharu, M. 2009. “Ancestral Landscapes and World Heritage from a Māori Viewpoint.” Journal of the Polynesian Society 118 (4): 317–338.

- Kearns, R. A., and N. Lewis. 2019. “City Renaming as Brand Promotion: Exploring Neoliberal Projects and Community Resistance in New Zealand.” Urban Geography 40 (6): 870–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1472445.

- Kidman, J., V. O’Malley, L. Macdonald, T. Roa, and K. Wallis. 2022. Fragments from a Contested Past: Remembrance, Denial and New Zealand History. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781990046483.

- Kuutma, K. 2009. “Cultural Heritage: An Introduction to Entanglements of Knowledge, Politics and Property.” Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 3 (2): 5–12.

- Lähdesmäki, T., Y. Zhu, and S. Thomas. 2019. “Introduction.” In Politics of Scale: New Directions in Critical Heritage Studies, edited by T. Lähdesmäki, S. Thomas, and Y. Zhu, 1–18. New York: Berghahn. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv12pnscx.5.

- Mackintosh, L. 2019. Shifting Grounds: History, Memory and Materiality in Auckland Landscapes c.1350–2018. New Zealand: ResearchSpace@ Auckland.

- Mackintosh, L. 2021. Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Auckland: Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781988587332.

- McCarthy, C. 2011. Museums and Māori: Heritage Professionals, Indigenous Collections, Current Practice. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press.

- McCarthy, C., A. Hakiwai, and P. Schorch. 2019. “The Figure of the Kaitiaki: Learning from Māori Curatorship Past and Present.” In Curatopia: Museums and the Future of Curatorship, edited by, P. Schorch and C. McCarthy. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526118202.00023.

- Morris-Matthews, K. 2015. First to See the Light: EIT 40 Years of Higher Education. Napier, New Zealand: Eastern Institute of Technology.

- Murton, B. 2012. “Being in the Place World: Toward a Māori ‘Geographical self’.” Journal of Cultural Geography 29 (1): 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2012.655032.

- Newton, P. December 18, 2018. Ihumātao: Recognising Indigenous Heritage. (15.01 mins.). TEDxAuckland. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tT11yvE5plo.

- Nilsson, B. 2022. “An Ideology-Critical Examination of the Cultural Heritage Policies of the Sweden Democrats.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28 (5): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2022.2042718.

- O’Donnell, E. L. 2017. “At the Intersection of the Sacred and the Legal: Rights for Nature in Uttarakhand, India.” Journal of Environmental Law 30 (1): 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqx026.

- O’Malley, V. 2016. The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800–2000. Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781927277577.

- Orwell, G. 1961. Nineteen Eighty-Four. New York: Signet Classics.

- Parsons, P. 1997. Napier City Heritage Study: Places of Spiritual Significance to Māori. Napier, New Zealand: Napier City Council.

- Paterson, R. K. 1999. “Protecting Taonga: The Cultural Heritage of the New Zealand Maori.” International Journal of Cultural Property 8 (1): 108–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0940739199770633.

- Prescott, C., and J. Lahti. 2022. Looking Globally at Monuments, Violence, and Colonial Legacies. London: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003397458-1.

- Rickard, V., D. Veart, and S. Bulmer. 1983. “A Review of Archaeological Stone Structures of South Auckland.” Auckland City Council. https://dl.heritage.org.nz/greenstone3/library/collection/pdf-reports/document/Rickard8;jsessionid=8EB108B1DC00F50B80F4046CFD35BC59.

- Rowe, D. 2022, 18 March. “What’s in the New New Zealand History Curriculum.” The SpinOff. https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/18-03-2022/whats-in-the-new-new-zealand-history-curriculum.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, P. 2020, 5 December. “New Zealand Declares a Climate Change Emergency.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/02/new-zealand-declares-a-climate-change-emergency.

- University, A. 2020. “Ihumātao’s Heritage Listing Win—What Does It Mean?” https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/news/2020/02/28/ihumatao-heritage-listing-win-what-does-it-mean.html.

- Veart, D. 2016, 1 May. “Archaeologist David Veart Explains the Significance of Ihumātao.” (17.38 Mins.), YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWXJgUhdGrw.

- Vermeulen, E. 2011. Memetics and the Architecture of Storytelling. Masters Arch, Auckland University. http://hdl.handle.net/2292/8918.

- Viriaere, H., and C. Miller. 2018. “Living Indigenous Heritage: Planning for Māori Food Gardens in Aotearoa/New Zealand.” Planning Practice and Research 33 (4): 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1519931.

- Walter, R., H. Buckley, C. Jacomb, and E. Matisoo-Smith. 2017. “Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand.” Journal of World Prehistory 30 (4): 351–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y.

- Wheen, N. R., and J. Hayward, eds. 2012. Treaty of Waitangi Settlements. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781927131381.

- Winter, T. 2013. “Clarifying the Critical in Critical Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (6): 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2012.720997.