ABSTRACT

This article adopts a reflexive methodology, called rapid logging, to examine how heritage values relating to the same heritage ‘thing’ are variously crafted by the mutual agencies of human and non-human actors on and with social media. In the process, it also explores the (in)visibilities produced through the heritage value assemblages co-curated by researchers with other actors including social media platforms and data, past objects, places and practices. The analysis focuses on the values associated with a specific case study, the area once occupied by the Old Gas Works, in North Canongate, Edinburgh, UK. Our conclusions demonstrate the importance of multi-platform and reflexive research to develop contextual and critical understandings of heritage value assemblages that can lead to fairer decision-making in heritage and more just societies.

1. Introduction

This article adopts a more-than-human approach to examine how heritage values relating to the same heritage ‘thing’ are variously crafted by the mutual agencies of human and non-human actors on and with social media environments. In the process it also explores the (in)visibilities and (in)justice produced through heritage value assemblages co-curated by researchers with other actors including social media platforms and data, past objects, places and practices.

In the last few years, there has been increasing consideration of social media websites as fields where interactions with the past can occur and be examined, qualitatively or in automated ways. Existing literature has analysed cultural, social and political values associated with tangible and intangible dimensions of the past on sites ranging from Twitter, Flickr, Facebook and Instagram, to eBay and YouTube (e.g. Arrigoni and Galani Citation2019; Bonacchi Citation2022; Gregory Citation2015). At the same time, significant theoretical contributions have emphasised the importance of ‘reading digital cultural heritage through a more-than-human and eco-systemic framework rather than a humanist’ (Cameron Citation2021, 129). In her recent book, The Future of Digital Data, Heritage and Curation, Cameron (Citation2021, 129) describes such a perspective as entailing an understanding of digital cultural heritage as ‘composed, conjoined and transformed by the co-evolving interrelatedness of a broad range of actors from people to technologies, algorithms, materials, infrastructures, energy systems, ideas and so forth’. Decentring the ‘human’ in digital cultural heritage-making has implications on how we conceive of and research the values that are co-constitutive of this heritage as well. Consistently, in fact, those values too should be understood as emerging assemblages co-created by human and non-human actors.

The digitally focused literature mentioned above builds on publications in the field of critical heritage studies more generally that have advocated for an understanding of heritage as assemblages resulting from the interacting and mutual agencies of human and non-human actors (Sterling Citation2020). For example, Harrison (Citation2013, 113) argues for the value of a ‘material semiotic’ approach that fully accounts for the material as well as the discursive nature of heritage. Macdonald (Citation2009b, Citation2009a, 4) and Bennett et al. (Citation2017, 5), amongst others, leverage assemblage theory to explore the ways in which heritage and museum objects are assembled through intersecting sociomaterial networks. The books Curated Decay (DeSilvey Citation2017), Heritage Futures (Harrison et al. Citation2020) and The Object of Conservation (Jones and Yarrow Citation2022) have investigated past-present-future assemblages by applying actor network theory in different contexts of heritage and museum practice. However, while the use of assemblage and more-than-human theorisation is not new in heritage scholarship, there has not been, so far, a focused and empirically evidenced reflection on how heritage values relating to the same heritage ‘thing’ are variously crafted by the mutual agencies of researchers and other human and non-human actors on and with social media environments specifically. Such a study constitutes the original contribution of this article and is of essential importance to account more effectively for the variabilities and (in)visibilities that can derive from the differential affordances of social media platforms in producing values relating to heritage and from the ways in which researchers curate these through harvesting and analysis of data.

A growing number of publications have addressed injustice in digitally enabled processes of knowledge creation (Fricker Citation2009). Discussing social media research, Leonelli et al. (Citation2021, 5) stress the significance of investigating the forms of prejudice that are built into our ways of knowing to understand ‘what is fair […] within society’. The authors claim that, to produce knowledge that supports social agency and empowers vulnerable groups’, it is key to ‘consider notions of trust, accountability, transparency and justice’ (Leonelli et al. Citation2021, 4). Data justice is central to this debate and can be defined as a ‘broad paradigm’ that ‘account[s] for complex power imbalances and injustices that are brought about by big data collection and use’ (Draude, Hornung, and Klumbytė Citation2022, 187, after Taylor Citation2017). According to Taylor (Citation2017), data justice entails an assessment of (in)visibility, (dis)engagement with technology and discrimination. In this article we will focus on the first pillar-notion of (in)visibility to understand the extent to which our study of heritage values with and on social media was just in representing diverse actors and perspectives.

We will address this important issue by reflecting on the research we undertook on the creation of social values relating to urban heritage places on social media platforms, which form an increasingly significant component in the heritage value assemblages surrounding specific heritage objects. In this article, we focus on a specific case study, the Old Gas Works in North Canongate, in the centre of Edinburgh, UK. This area was intensively analysed during the Deep Cities project (2020–22), which aimed to develop methodologies for understanding the social values of complex, layered urban environments to guide the curation of urban heritage transformations across Europe (Deep Cities Citation2020).Footnote1 The Old Gas Works constitutes an ideal case study to explore the social values of heritage due to its fast-changing and deep history and because it has been at the centre of controversies regarding the transformation of the city (see 3. Methodology). Examining how injustice is embedded in knowledge production about heritage is, in fact, of particular consequence when it informs decisions on themes of public interest, such as conservation and urban planning.

In the next section, we introduce the concept of ‘social value’ and ‘heritage value assemblage’, and discuss how a more-than-human approach to researching heritage values on and with social media can help to identify injustice. Our understanding of the term research recognises that researchers and their methods contribute to the crafting of heritage values as they examine them. In sections three and four, we present our methodology and findings. Thereafter, we conclude by emphasising the need to implement reflective and multi-environment investigations of heritage value assemblages on/with social media. We argue that this is paramount to account for the actors and processes involved in value generation more fully, so that different agencies and perspectives may be considered in value-driven heritage curation, leading to the construction of more just heritage futures and societies.

2. (In)visibility as a measure of injustice

Visibility, hypervisibility and invisibility have been debated robustly in critical data studies literature, particularly in relation to data feminism. D’Ignazio and Klein’s foundational work has highlighted that, in research, policy and other aspects of modern life, it is what ‘gets counted’ that ‘counts’ (D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020, 97). Furthermore, what is counted hides, overexposes or differentially platforms different individuals or even parts of the same person (their bodies, identities, etc.) in ways that are often undesirable (D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020). In social media research, social media companies are largely responsible for determining what is counted by deciding what user data is produced and collected and the extent to which it will be searchable and usable. In doing so, social media may reproduce injustice that exists offline and in society more generally, something that is also known as ‘societal bias’ (Brown, Davidovic, and Hasan Citation2021). An example is that algorithms that use smartphone data will prioritise the views and preferences of individuals who are wealthy enough to afford those devices over others Brown, Davidovic, and Hasan Citation2021, 5).

Presenting research that uses social media data to generalise about a specific population offline can contribute to epistemic injustice as well. Morstatter (Citation2016) conceptualises ‘population bias’ as relating to the different socio-demographic characteristics of the individuals that use social media sites. A survey of the UK population revealed that, as of 2013, only Google+ and Instagram allowed statistically representative studies of the UK population, because their user profiles were not skewed towards certain socio-demographic characteristics (Blank and Lutz Citation2017). In contrast, for example, higher income (but not educational background) is correlated with Twitter use (Blank and Lutz Citation2017). YouTube, Snapshot, Instagram and TikTok are more popular among younger people, who are instead progressively abandoning Facebook (Atske Citation2022). Furthermore, a survey of adults’ use of social media in the US showed that higher socio-economic groups are more likely to be on more than one platform; therefore, research drawing on big data tends to over-represent people in this category (Hargittai Citation2020).

In addition to these considerations relating to data justice and fairness of use of social media data for research more generally, there are others that apply to heritage specifically and are important to understand who-what is represented in assessments of social values. The concept of social value refers to the meanings and values associated with heritage places, objects and practices by contemporary communities of residence, attachment and interest; ‘the concept encompasses the ways in which the historic environment provides a basis for identity, distinctiveness, belonging and social interaction. It also accommodates forms of memory, oral history, symbolism and cultural practice’ (Jones Citation2017, 22). Over the last twenty years it has taken on increasing significance in heritage policies, even though there is still a gap in implementation in routine conservation and management (Jones Citation2017). More broadly, the relationships constituted by these social values, as defined here, are part of the wider ‘heritage value assemblage’, which results from the ways in which a heritage ‘thing’ is variously crafted by the mutual agencies of non-human and human actors (on heritage assemblages and values, see also, for example, Bennett et al. Citation2017, Harrison et al. Citation2020 and Macdonald Citation2009a, Citation2009b).

However, there is a pressing need to reflect on the social values that are produced and negotiated around heritage places through and with social media. In this context, it is imperative to consider the agency of specific platform infrastructures. For instance, Facebook and LinkedIn have more complex functionalities than Twitter or Instagram and this has implications for the locality and modality of platform use. More sophisticated platforms are frequently accessed via both mobile devices and desktops, whereas mobile access is strongly prevalent for the others. Thus, the situated experience of interacting with a heritage ‘thing’ can vary profoundly. Furthermore, each of us may enact different data practices in connection with one or more of our multiple identities – e.g. as ‘good citizens’, neighbours, hobbyists, professionals, parents, etc. We may be amateur photographers of castles on Instagram and environmental activists on Twitter. These possibilities contribute to determine the meanings we express in relation to heritage; and, indeed, how a particular object of attention is produced (c.f. Jones and Yarrow Citation2022 for how heritage objects are constituted through conservation practice). In turn, the way in which a heritage thing exists on a given platform influences who we are in that space and is shaped by the web infrastructure, symbolism, software and collecting policy of the social media company.

Everyday experiences of the past are not only mediated by data, devices, digital systems and methods, and algorithms, but also by ‘the infrastructures through which we research and share our scholarship, research, and practice’ (Pink Citation2022, 747). For example, Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are designed to enable specific levels of access to the databases of social media companies by third parties including researchers. Companies have adopted their own, often different, approaches to data accessibility. In some cases, larger quantities of data can be extracted and mined thanks to more open APIs, while in others this is not possible because APIs have been shut down or substantially limited. Researchers will tend to use the data that is more easily available to them, therefore undertaking their work on and with certain platforms more than others. In this way, they will contribute to the over-representation and privileging of users on those platforms. Data, digital methods and web infrastructures play a role in ‘making’ heritage objects and values. We conceptualise the latter as ‘heritage value assemblages’, because they exist as aggregates resulting from the ways in which meaning is continuously generated and significance is framed, performed and studied. From a socio-material perspective, in fact, ‘the concept of the assemblage is adopted to encapsulate the idea of ever-changing human-non-human gatherings’ (Lupton et al. Citation2021, 5). As mentioned above, heritage value assemblages include, but are by no means restricted to, social values, which will be the focus in this article.

In summary, there are endless possible relationships between the human and non-human actors involved in making heritage value assemblages on and with social media. These actors can comprise heritage researchers, people engaging with the past, their bodies and identities, social media platforms, the devices used to access them, functions such as impressions, signs like hashtags or @ for tagging, APIs, algorithms that push certain content more than other, data, metadata, etc. (after Bonacchi Citation2021; Thompson Citation2020). Together, these actors co-create knowledge about the values of a heritage ‘thing’ on social media platforms. Exactly how this happens, however, and the kinds and levels of injustice co-produced have not yet been researched extensively and are the subject of our analysis.

3. Methodology

3.1. A reflective approach to researching heritage values

The study reported in this article consists of two main components. The first involves the investigation of heritage value assemblages emerging from social media and relating to a specific place, in the historic centre of Edinburgh, UK (see sub-section 3.2). The second component critically reflects on the first using rapid logging, a method applied while the research on heritage value assemblages was unfolding. We will introduce each of these components in turn.

Researchers used a mixed methodology to analyse social media data, and uncover social values and tensions associated with the case study in offline and online contexts (see Jones et al. CitationForthcoming for a detailed presentation). The methodology was designed to be implementable over a period of four months so that it could more easily be commissioned in future, by heritage managers or urban planners, to inform timely decision-making about urban heritage transformations. Offline research consisted of mixed methods, rapid ethnography and is discussed in Jones et al. (CitationForthcoming). The social media research, which is the focus of this article, was undertaken between May and September 2021; it was centred especially on Facebook, Flickr and Twitter. These platforms were prioritised for two important reasons. Firstly, they allowed both automated and on-platform analysis. Secondly, a keyword-based manual assessment had revealed a more prominent presence of our case study area in texts, videos and images on these social media sites. By contrast, the case study was only marginally or not at all present on YouTube and Reddit, the other two popular social media platforms that had accessible APIs for data extraction at the time of the research.

The methods chosen to assess values included close reading of text, images and videos as well as text mining techniques consisting of topic modelling, term frequencies and associations, and sentiment analysis. Despite the use of both data-intensive and qualitative methods, the overall interpretation of the results is qualitative and contextual. The article is concerned with differences between social media sites and with the agencies behind such differences, rather than with exhaustiveness in the assessment of the social value assemblages generated in and with each platform. Text mining was largely used to navigate large corpora of data, on Twitter and Flickr, to identify where the Gas Works featured, scope themes and sentiment and situate them in a broader context. Relevant material was then analysed primarily qualitatively, in part due to its limited quantity. Such limited quantity should not be read as surprising or, indeed, problematic. As discussed in Bonacchi (Citation2022), the primary use of data-intensive techniques to understand heritage values expressed on social media is that of locating those rare occurrences when people reference the past serendipitously as they go about their daily lives. Furthermore, in our specific case, social media was a very important environment for exploring heritage values because the place we were examining had suffered from considerable displacement of communities caused by pro-longed redevelopment.

Automated data extraction and analysis was performed using R Free and Open-Source Software. shows a summary of the methods of data collection and analysis utilised and of the data examined for each platform. Differences in the methods chosen relate to variabilities in web infrastructures and policies as well as information available. They will be discussed in section 4 since they contributed to the research as well as the creation of heritage value assemblages. The research received ethical approval by the University of Stirling. Data extracted from Flickr and Twitter was anonymised by substituting usernames and user IDs with random numbers. Where direct quotes are included to illustrate qualitative analysis we have avoided using content that might allow the identification of authors through web searches. Only single terms and frames are quoted directly, and any proper person names were substituted with fictitious ones.

Table 1. Methods of data collection and analysis performed.

As Sarah Pink points out, however, emerging technologies in research require us to research alongside and with web infrastructures underpinned by automation and call for novel and bespoke methods of analysis that creatively ‘tweak’ more traditional ones (Pink Citation2022, 747). To investigate the kinds of value assemblages co-created by researchers and others on/with different platforms, we developed an approach called ‘rapid logging’. This approach focuses on the use of rapid ethnography with a strongly reflexive component. Rapid ethnography entails the deployment of ‘intensive routes to knowing’ often through team-based and participatory techniques (Knoblauch Citation2005). Rapid logging consists of following rapid assessments of heritage values on social media sites through the individual logging of reflective notes that researchers discuss periodically as a team. In this way, we could critically analyse the multiple actors and agencies at play in the creation of heritage values, as well as the (in)visibilities produced.

The project researchers ‘logged’ reflections on the ways in which their research functioned as an actor-network in the making of heritage value assemblages. This actor-network comprised researchers’ choices, functions, web infrastructures, APIs, software, etc. Researchers noted the affordances of this actor-network and their interrelations with other human and non-human actors encountered, specifically attending to who played what roles in crafting heritage value assemblages. The notion of ‘affordances’ was originally developed within ecological psychology (Gibson Citation1979). In social media research, it describes the possibilities – the ‘new dynamics or types of communicative practices and social interactions’ – enabled by certain kinds of technology (Bucher and Helmond Citation2018, 239; Ellison and Vitak Citation2015). Bossetta (Citation2018, 474) argues that ‘digital architectures shape affordances and, consequently, user behaviour’. According to his analysis of the impact of social media on political behaviour, the elements of digital infrastructure that influence affordances are network, functionality, algorithmic filtering and datafication (what a social media site decides to measure). Affordances are also relational, as the possibilities provided by features of technologies may change depending on the individual using them and the socio-cultural context in which they operate (see Costa Citation2018 for an application).

Regular discussions about the content of logs, through weekly meetings, aimed to encourage reflexivity and create a mutual awareness of the research unfolding on different social media platforms. Importantly, because rapid logging followed the rapid assessment of heritage values achieved through data-intensive and qualitative analyses of social media data, it reports on human-actor interactions in a way that is necessarily partial. It reflects what is possible to uncover regarding heritage value co-creation given the agencies of ethical research codes, researchers’ skills, digital infrastructures, metadata, etc. that make up the research actor-network and were followed from the specific viewpoint of researchers.

3.2. Case study context

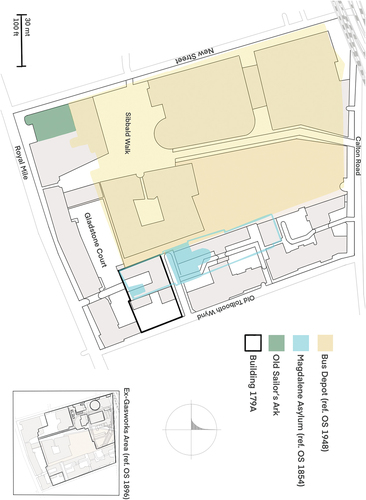

Our exploration of heritage values focused on the area once occupied by the Old Gas Works in North Canongate, within the Old Town of Edinburgh (UK) (). Despite its constant transformations, the burgh of Canongate preserves visible material traces dating back to its medieval origins through to the industrial and post-industrial era (Adamson, Kilpatrick, and McDonald Citation2016; Dennison Citation2008). Except for the street frontages overlooking the Royal Mile, the area was used mainly for semi-agricultural purposes up until the early 19th century (Adamson, Kilpatrick, and McDonald Citation2016). At that time, the Society for Support of The Magdalene Asylum of Edinburgh regarded it as an ‘airy and healthful situation’ suitable for the construction of a new Asylum for so-called ‘fallen women’ (RSEMA Citation1830). However, the advent of gas production changed the area profoundly. The first Gas Works buildings were erected in 1818 and expanded to the point of occupying the whole area between New Street and Old Tolbooth Wynd (). The Magdalene Asylum was partly absorbed by the Gas Works after 1864, when the institution moved elsewhere, since the Canongate area had lost its rural character (McLaren et al. Citation2022). The main Gas Works buildings currently located in 179a Canongate were built over the Asylum’s front garden, incorporating also the adjacent courtyard and structures ().

Figure 2. Map of the case study area showing key phases in its historical development © Elisa Broccoli.

Figure 3. North-east corner pertaining to building 179a in Old Tolbooth Wind. These front elevations are two of the few remaining upstanding structures of the Old Gas Works © Elisa Broccoli.

With the arrival of electric lighting, the Gas Works started to decline until the buildings and land on which they stood were repurposed entirely, first turned into a football ground and subsequently into a bus depot and a large car park. Between 1996 and 2003, the Out of the Blue charity converted some of the derelict bus garage offices into an arts centre, providing a workplace for artists and organisations, and a space for live performance and club nights with the Bongo Club. Both the car park and the arts centre were demolished in 2006 and the former Gas Works area is now part of a development called ‘New Waverley’. In contrast, the Gas Works’ remains in Gladstone Court are still standing, even though, over the years, this part of the complex was altered (). Between 1970 and 1980, it was one of the venues of the Richard Demarco Galleries, hosting Avant Garde exhibitions and activities. In the late 80s, it was converted into office accommodation and partially extended (Bradley-Lovekin, Roy, and Sproat Citation2019). Most recently, this court of buildings became one of the most popular indie markets in Edinburgh, the Old Tolbooth Market, originally set up as an experimental community project (). Since the Market closed, at the end of 2019, the site has been empty and inaccessible to the public, while awaiting commencement of an approved redevelopment.

Figure 4. View of the elevation that once served as the main access to the Tolbooth Market © Elisa Broccoli.

Today, the case study area is amongst the 50% most deprived in the country, according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (Scottish Government Citation2020).Footnote2 It comprises 40 households; 30% are owned, with the other 70% being rented, just under half privately (47.5%) and the rest from social housing schemes (20%) or the Council (2.5%). A significant student population lives in or travels to the site because of the proximity of university residences and departmental buildings. This is evidenced by Census data showing that 10% of households are occupied entirely by students (the figure for the whole city being 3%). Furthermore, 22.4% of residents were not born in the UK (15.9% for the wider city) and most of them (60%) had lived in the UK for less than two years (double the figure for the entire city). Overall, the data suggests that Canongate currently has one of the most fast-changing populations of Edinburgh.

4. (In)visibilities in heritage value assemblages

4.1. Assemblage 1: emerging from/with Facebook

We chose two very active Facebook environments for in-depth qualitative analysis, in response to the impossibility of examining Facebook data at scale. After the Cambridge Analytical scandal, Facebook closed its public API and introduced an application procedure through which researchers could request data for academic projects concerning democracy and misinformation. Whilst the research team submitted a proposal to access posts focusing on the area of Canongate, in Edinburgh, approval arrived after the end of the fieldwork and beyond the timeframe (then) stated by Social Science One, which reviews research proposals for Meta (Harvard University Citation2023). Company policies and related bureaucratic practices like these play a significant role in influencing methodological choices and, consequently, in mediating how heritage values are made visible as researchers assess them.

Given that the overarching objective of the Deep Cities project is to inform the work of heritage managers and planners in relation to urban transformation, it was necessary to develop relatively rapid methods that can be applied in practice. We therefore selected the Lost Edinburgh public page (160,000 followers) and group (48,000 members), run by the same administrators, for on-platform qualitative analysis. Only administrators can publish posts on the Facebook page, whereas both administrators and group members can post on the Facebook group. The contributions of group members are also often re-posted on the Lost Edinburgh public page, creating a circular dialogue and complex network between them.

It was logged that the Lost Edinburgh public Facebook page and group ‘seemed the most informative about people’s views on the transformations of the case study area’. It is worth reflecting on what ‘informative’ means in this context. Researchers agreed that the two Facebook spaces hosted data that was certainly addressing the heritage of Edinburgh; through keyword-based manual searches, they also ascertained that the case study featured amongst those mentions. The need to retrieve relevant material in a relatively short amount of time therefore led to focus on (and foreground the views of) a retrospective Facebook page and Facebook group concerned with the past of the city. We manually identified posts discussing the case study area and published between 1 June 2016 and 1 June 2021 on the page or the group, along with associated comments and reactions (11 posts and 298 comments created by 181 unique authors). Subsequently, the relevant textual and visual content was analysed qualitatively, with a view to understanding the production of values relating to the case study in this particular online environment.

Retrospective Facebook pages, dedicated to lost urban features and other heritages, have become almost a ‘genre’, and their formation is facilitated by Facebook’s conversational affordances (Gregory and Chambers Citation2021). Anyone with an account can set up a public page, where administrators ‘initiate conversations’, and others can respond and share additional content in the bounded but expandable space of the ‘wall’. We observed that ‘engagement is driven by the posting of old photographs, mostly in brown tones and accompanied by extensive captions’. For example, an image of the Canongate area when it was occupied by the Bus Depot, was shared in the summer of 2021 by the administrators of the Lost Edinburgh page, accompanied by these words:

The roof of New Street Bus Station was built on the short lived cinder pitch Bathgate Park which was home of junior football team Edinburgh Emmet. The site had previously been the old gas works with its huge chimney. When Edinburgh buses failed to buy the Edinburgh Exhibition Centre (now Annandale Street depot) built in 1922 New Street was built. In its final years New Street was used as a car park and if I remember was home to the ‘Bongo Club’. Today the Caltongate development is on this site.

The types of data (textual, visual, audiovisual) afforded by the network’s functionality (Bossetta Citation2018, 476) helped to attract users’ attention on a given topic and prompted their participation in threads of comments and replies. As emphasised by Gregory (Citation2015, 27), in her study of the Beautiful buildings and cool places Perth has lost Facebook group, photos have the power to elicit ‘tender regard’ for the past (after Sontag Citation2008, 71). Additionally, Gregory (Citation2015) argues that groups such as the one we observed express ‘an architecture of the heart’ based on the emotional and mnemonic attachment to a place (after Hornstein Citation2016, 3). ‘Old images’ with evocative captions trigger responses from users, the majority of whom must be in their 50s and over, since they have personal memories of the 1950s, 60s, 70s and 80s. This demographic seems rather different from that of followers of the Lost Edinburgh Facebook page overall; most of them were in the 25 to 44 age bracket as of 2015 (Gregory and Chambers Citation2021). Our research therefore renders a specific age group visible (and potentially others invisible) by focusing on this Facebook environment and associated meaning-making, foregrounding their ideas, values and memories.

Furthermore, as noted in our reflective logs, ‘longer threads emerge after a user asks a question about the place, within a comment under an image’. Users tended to answer each other’s questions and, in line after line of comments, shared opinions that brought to life multiple but similarly nostalgic versions of the case study area. These multiples (aspects of a heritage object at a given time) often related to the working lives of the Facebook users themselves, or of people close to them, and they mainly focused on the Bus Depot and the Old Gas Works. The latter was the most recurrent in people’s memories, and images of its towering chimney invited reflections on the environmental and affective qualities of the industrial past, such as smog, and the ecologically distinct urban experiences that preceded the Clean Air Acts of 1956 and 1968. Here, negative attributions relating to poor air quality and the ‘disgusting smell’ are intermingled with wistfulness for the yellow mist that covered the authors’ younger selves. Amid the ‘yucks’ and accounts of deaths of emphysema, these nostalgic notes tell complex stories, peopled by familiar characters, like ‘Big Georgie’, who worked at the Gas Training Centre in the 1970s. Authenticity is characterised as coinciding with a hard life conducted within rough industrial and post-industrial landscapes, and users lament their loss in the face of ‘concrete, glass and steel’. Except for the football pitch, other playful manifestations of the place – the market, or the art gallery, for example – are absent and no past beyond living memory is evoked.

Users added tags (@) to texts to connect past and present conversations, and to bring together multiples of the same user who contributed at different points in time. These tags worked across time and linked temporally distant identities. For example, in one of the 44 comments published under the post featuring a photo of the Bus Depot, a tag calls in another user, reminding them of an exchange that took place ‘the other week’. This interactive affordance was found to be an important enabler of relatedness in a previous study focusing on Facebook users older than 60 (Jung and Sundar Citation2018). It co-works to create a sense of familiarity that is not fleeting, and characterises the Lost Edinburgh group as being at least in part interconnected.

As noted above, in the case of Lost Edinburgh, individuals, mostly consisting of users in their 50s and over, mobilise the multi-modal sharing functionalities of Facebook to remember and celebrate a ‘tough’ but ‘genuine’ past. However, there are also departures from such a narrative. In contrast to Ekelund (Citation2022), we found that people were not merely engaged in ‘fragmented nostalgia’, important though that is in authenticating practices of establishing an author’s connection to a specific place and time. Rather, there are many instances where reflective considerations were informed by an interest in learning from each other and developing knowledge, with several comments and replies correcting or qualifying previous user contributions. For example, after the administrators of the Lost Edinburgh page published the photo of the bus depot, a user wrote that the building was wrongly captioned as a bus station.

Finally, the Facebook page and group offered a space to ‘(re)create’ a local community through the aggregation of members from the several different ‘local communities’ that developed in the case study area over time, before the ‘Waverley’ development took place. However, our decision to focus on Lost Edinburgh is likely to have restricted the kinds of values that would have been uncovered by the systematic text mining of a broader range of public Facebook pages and groups, had this been approved by Meta in the timeframe of our fieldwork. Extracting a higher number of pages and groups focused on ‘Canongate’ would have potentially revealed more ‘current’ meanings attributed to the site and more serendipitous and alternative – perhaps future-looking – responses to development-led change. However, investigating these without text mining is not viable since references to heritage are ‘hidden’ and very rare if the whole page or group is not centred on this topic (Bonacchi Citation2022).

4.2. Assemblage 2: emerging from/with Twitter

At the time when the research took place (May – September 2021), Twitter had an API designed for academics, which allowed the extraction of up to ten million real-time and historic tweets per month that responded to certain queries (they contained a specific string of characters or keyword/s). We reflectively logged that this API provided us with an opportunity to ‘rapidly “sweep” heritage values expressed on this platform in relation to the case study area’. Using the R package academictwitteR (Barrie and Ho Citation2021), we mined 6,250 potentially relevant tweets, identified as those containing the term ‘Canongate’ and dating between 1 June 2019 and 1 June 2021. This initial corpus was inspected quantitatively to provide context that could help us orientate the subsequent close reading of tweets specifically referencing the space once occupied by the Old Gas Works. We analysed hashtag frequency and used term frequencies and term associations to examine text, author location and profile description for all tweets in the corpus. Thereafter, we searched this corpus for terms related to past and present phases and uses of the case study area. Such terms were chosen based on the results of published literature and new primary research on the history, archaeology and social values of the area conducted via archival investigation, topo-stratigraphic approaches to standing buildings and offline rapid ethnography, including interviews, transect walks and focus groups employing photo elicitation (for detailed discussion of these see Jones et al. CitationForthcoming). In this way, we identified 23 tweets and associated threads of replies that were directly concerned with the site, which we then analysed qualitatively, looking for key value-related themes.

Twitter’s interface is less bounded than Facebook’s, and tweets move downward rapidly in users’ Twitter Home. These features of the platform’s digital infrastructure are less conducive to the emergence of the retrospective and intimate interconnectedness we observed for the Lost Edinburgh group. Differently, Twitter affords a ‘natively digital’ kind of ‘momentary connectedness’ enacted by users not only through tagging users’ handles, but also via hashtags:

Sending tweets with an issue-response hashtag is a momentary act that brings users to a topical structure of connectivity. That, however, is not necessarily an indication of user intention to form or interact with well-defined, and unified, communities or publics.

Although in the passage above, the authors refer to issue-response hashtags, the same concept can be extended to other kinds of hashtags such as place-based ones. The latter are intended to momentarily connect a Twitter user with others who are or have been at a location. Hashtags are therefore important because they influence the co-working of themes (including heritage places and values) and users on and with Twitter. Within the corpus of 6,250 tweets containing the term ‘Canongate’, however, the most frequently recurrent hashtags after #canongate itself, were popular locations and landmarks nearby such as #Holyrood (featuring 59 times) and the #royalmile (41 times). By contrast, only two hashtags pertained to our site: #newwaverley (used twice) and #tolboothmarket (used once). The first is the name of the development project acquired by Queensberry properties to create new and modern residential buildings and retail space in the case study area (Queensberry Citation2018). The second, #tolboothmarket, refers to a particular use of the former Gas Works as an indie market, selling street food and drinks in a music-filled and art-rich environment.

During the analysis, we logged that this could be in part influenced by the fact that ‘popular hashtags are suggested to users in a drop-down menu as soon as the # symbol is included by a user in a tweet’. The more hashtags are being used, the more they are suggested and contribute to reinforce majority tastes and choices. These signifiers pushed forward the most visible heritage and co-produced a version of the Canongate where the case study area was almost absent. While the physically and visually prominent/promoted material heritage of Canongate and the Royal Mile generally became ‘hypervisible’, the social and industrial heritage that is relatively hidden from a passer-by’s eye was rendered almost invisible. Furthermore, in contrast to the Facebook group and page we investigated, tweets platformed multiples of the area that were ‘alive’ at the time of tweeting. Only one of the 23 tweets takes a retrospective view or embraces a nostalgic mood. Canongate features predominantly as a ‘present thing’ characterised as an aesthetically appealing attraction for cultural tourism, or valuable for its local businesses. The only exception is one tweet that contains an image of late Victorian Edinburgh showing the prominent Old Gas Works chimney. This photo of a bustling city scape accompanied text noting how ‘we’ (a reference to a transtemporal local community) have witnessed ‘wars’ and ‘plagues’ as well as positive events and ‘celebrations’. Tweeted in July 2020, amidst the Covid pandemic lockdowns in the UK, this industrial landscape is used to evoke a heritage of survival associated with the district of which the Gas Works were inherently part. Even here, however, the recollection is forward looking, as the past is recalled to find strength in dire circumstances.

A group of tweets also referred to the New Waverly development. They either retweeted press releases and updates on the topic originally tweeted by news outlets, or replied to such news-focused tweets expressing disapproval. The New Waverly site’s future destination as a place for government offices, amongst other residential and retail functions, is linked in these tweets to the ‘imperialism’ of the British Government over Scotland. One author complains about erroneous heraldry used on a corner of New Street, and encouraged the ‘knitting of a baclava’ to deface it, calling this action ‘a civic duty’. Such an ‘Imperial Government’, of which the new development is considered an expression, is antagonised and opposed using passing mentions of the Gas Works.

In this assemblage, researchers’ systematic data extractions, co-produced with users’ mobilisation of hashtags and Twitter’s mediation of this through hashtag suggestions, render the case study area relatively invisibile, beyond its more famous and touristic loci: Canongate as a whole and the Royal Mile. The rare and disconnected references to the site presented it in its contemporary form and uses, with two exceptions that were, however, still linked to the forward-looking, activist intensions of the users who tweeted them. Anger towards a development perceived as political and prioritising commercial interests over those of the communities takes centre-stage, although in a more de-contextualised and less ‘organised’ manner than the one documented for the Flickr assemblage discussed next. The perspectives of local activists, tourists and commercial businesses are foregrounded compared to others.

4.3. Assemblage 3: emerging from/with Flickr

Through Flickr’s API, it was possible to extract up to 4,000 photos per query together with their metadata. As with Twitter, manual and exploratory searches of Flickr using unequivocally popular, placed-based keywords such as ‘Canongate’ and ‘Edinburgh’ suggested that the ex-Gas Works is relatively invisible. Therefore, researchers interrogated the API with the R package photosearcher (Fox et al. Citation2020) to retrieve relevant photos published until 2021. These photos had geotags related to the ex-Gas Works area and/or their title, description, tags and comments included one or more keywords within a list of terms referring to specific placenames and phases of the site.Footnote3 Since this method yielded less than 100 photos, the number considered to be sufficient for the study, automated searches were eventually integrated with manual ones using a snowballing approach. Researchers gathered other photos published by the same users who posted the images returned by the automated search; they also collected photos appearing in comments about the photos obtained in an automated way. As underlined by Kennedy et al. (Citation2007, 635), ‘it is important to recognise that location-based tags are not always used to annotate the content of the image in the traditional sense’. In our case, there were not many such texts, and some tags were misspelled or inaccurate; users’ behaviour therefore influenced the possibility of finding relevant photos automatically and the kind of assemblage that resulted from this research practice. We logged that this would be ‘more likely to happen with research that focuses on a relatively small or less visible area of the city or a landscape more generally’.

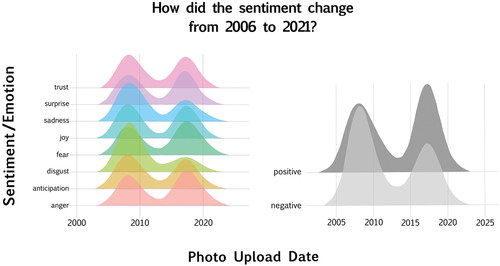

Topic modelling of the corpus consisting of all the text documents (titles, descriptions, tags and comments) related to the final sample of 100 photos was performed using the R package tidytext (Elsinghorst Citation2017; Silge and Robinson Citation2016, Citation2017). This analysis brought to the fore several different actors: the Caltongate development plan; people involved in this plan; photography; and Gladstone Court, where the last Old Gas Works building still stands; the bus depot and the car garage in New Street. Comments on the Caltongate masterplan were all negative, as in the case of Twitter towards the New Waverley plan which replaced the Caltongate. Since photo metadata comprised upload dates, we estimated how sentiment associated with the area changed from 2006 to 2021, through a quantitative, lexicon-based analysis, using again the R package tidytext,().Footnote4 Disgust and sadness were prevalent before 2014, when the New Waverley Development that followed the Caltongate Scheme was approved. Visually ordering images based on upload date helped to understand why this happened and clarified what people considered to be valuable of the case study area; this could be a past or present building (the Old Sailor’s Ark or the blue entrance of 179a Canongate), a street (part of New Street before the transformation), a particular feature of that urban environment as a landscape view (the view of the ex-Gas Works site from the top), or, more generally, public spaces (e.g. Sibbald Walk or the Tolbooth Market). The photos also showed people’s interactions with the area including protest activities and participation in local markets. Furthermore, the analysis of how the ‘photo collection’ changed through time revealed that certain buildings were photographed mostly when their fate was decided, which likely coincided with a heightened sense of threat or loss (e.g. the Old Sailor’s Ark and New Street’s views were the predominant subject in 2013–2014). We observed that, in contrast to Facebook and Twitter, the multiples of the ‘case study on Flickr are versions of the space at critical times for their existence and that of a local community’. At those times, they had more visibility and were the subject of concern. Demolished buildings were posted to highlight missed opportunities to preserve heritage considered valuable by users (New Street Gas Works and Bus Depot).

Figure 5. Sentiment changes evidenced via quantitative, lexicon-based analysis of texts associated with 100 photos relevant to the case study and published on Flickr between 2006 and 2021.

Generally, only 27 photos (of 100) were accompanied by comments. Photos were shared by locally active photographers with the primary intent to document the urban space and its key changes, sometimes for protest purposes. The textual content accompanying these images consisted of website links, protesters’ signs and initiatives related to the Save Our Old Town Campaign; such material turned the platform into an image-driven ‘unruly and instant’ archive (Geismar Citation2017, 333) about the urban life and struggles of a local community. Furthermore, Flickr played an external/outward role, becoming an arena for mobilisation and recruitment, for the transnational distribution of information and protest. In a minority of cases, the photos are listed as being part of groups that contribute to such agendas: the Save our Old Town, Progressive Photo-Journalism, and Demolitions groups. Flickr’s digital infrastructure co-worked with activists as a space to ‘self-mediate’. As Cammaerts (Citation2015, 92) writes, ‘movements use technologies of self-mediation to construct and sustain collective identities, to articulate a set of demands and ideas and in effect to become self-conscious as a movement’. This is evident, for example, when a user from east-central Europe commented that in their country they have their own problems affecting World Heritage sites, but Edinburgh losing their status due to the ignorance of developers would be a loss for everyone not just local inhabitants (). Here, then, we see the role of Flickr as a ‘technology of self-mediation’ in ‘transmitting practices, tactics and ideas across space and time’ (Cammaerts Citation2015).

Figure 6. Photo entitled ‘Caltongate’, shared on Flickr. CC BY-NC © Angus Mcdiarmid. https://www.flickr.com/photos/angusmcdiarmid/3026716887/in/photolist-5BsHtV.

5. Conclusion

The research discussed in this article shows how heritage value assemblages emerging from different social media platforms may differ profoundly, because of the mutual agencies of human and non-human actors, in a range of contexts and times. Researchers’ choices, in part influenced by the affordances of digital infrastructures, contribute to the creation, as well as the investigation of, these assemblages. Within such assemblages we highlighted (hyper)visibilities as well as invisibilities, which both inform and are informed by ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ values associated with the site of the Old Gas Works, in North Canongate, Edinburgh, UK. In turn, these (in)visibilities and the values connected with them constitute the heritage object at the heart of the case study in different ways that, following Annmarie Mol (Citation2002), can be said to be more than one, but less than many.

We have shown how the retrospective Lost Edinburgh Facebook page and group surface nostalgia towards the case study area, which is chiefly celebrated for its working class heritage. This is an outcome of the multiple affordances and actors involved, including the closed Facebook API, the short duration of the research, the strong interactivity and multimodality of the Facebook page, and the 50+ age profile of the users who, at some point in time, belonged to the ‘local communities’ physically present at the site. The assemblage documented for Twitter is markedly different, revealing only a few, disconnected tweets directly related to the case study, despite the more wide-ranging data extraction facilitated by the API. This is likely to have resulted also from algorithms that prioritise popular hashtags over less popular ones and from Twitter’s rather unbounded, rapidly changing and immediacy-focused interface. In this assemblage, the meanings assigned to the place relate to present-day use and activist mobilisation in opposition to privatisation and development, rather than nostalgic forms of engagement with its past. Finally, the heritage value assemblage produced and researched with Flickr expands and, to some extent, internationalises this activist ethos. However, in contrast to Twitter, it is organised through the photographic documentation of buildings at critical stages of their biography. The values of the site that are privileged are those within living memory, linked to the public space that was once available to residents and which is no longer there.

There are variabilities between the three assemblages from three points of view: the multiple ways in which the site is constituted as an object of attention, the values attached to these multiples, and how heritage values are put to work. Through Facebook, we observed the hypervisibility of working class industrial heritage and sports heritage (the football pitch). These had value for a specific demographic who turned to the Lost Edinburgh group and page to experience a sense of place-based community no longer readily accessible for them offline. Flickr platformed multiples of the site that are mostly, although not exclusively, within living memory but not necessarily related to working heritage – aspects of leisure life relating to the Bongo Club, the artist studios, the Tolbooth market were all represented. The social and personal values connected to these urban features at different points in time were prominent and presented as in need of protection against developers’ plans. Twitter is similar in this activist respect, but comprises more strongly political and politicised views and values.

The implications of these results are significant, if, as researchers, we hope to explain reality in ways that account for and expose differential visibilities, so that findings may be used to inform the creation of more just social and heritage futures. Rapid logging as a method to record the active role of the researcher in the curation of values alongside other actors can help to build robust reflexivity and contextualisation in assessments of heritage meanings and uses. Such an approach is vital to understand the kinds of assemblages that express certain sets of values, the heritage multiples that are made visible and the reasons why they matter for specific individuals and groups. Researching heritage values on several different social media spaces will contribute to expose many, if not all, the imbalances in visibility afforded by platforms in their interplay with other actors including researchers.

Beyond the academy, studies of this type could be commissioned by heritage managers and planners to shape decision making about the transformation of heritage places. Our approach was designed to be implemented rapidly, over a few months, and on shoestring budgets, with virtually no additional cost other than researchers’ time. None of the techniques outlined requires extensive training and expensive, proprietary software – an important aspect that renders this research accessible to organisations of different scale and capacity. As such, for example, it could be funded alongside or as part of the work of commercial units responsible for archaeological assessments and community engagement. This would ensure that the views and values of communities online are considered more fully and critically in the ‘making of places’. For instance, research to unearth the differential values associated with heritage places on an array of social media platforms could help to understand the attitudes of those who are no longer ‘local’ to an area as well as more political and controversial meanings that people may not feel comfortable to express when questioned directly. Finally, the proposed methodology could aid collection management, whether in museum, library or archival contexts. If adopted by audience development and interpretation teams, it could inform curatorial practice at different levels. In all the situations described, foregrounding (in)visibilities can help to rebalance representational and epistemic injustice in a digital age.

Author contribution statement

CB designed the research on heritage values in social media spaces and conceptualised the article; SJ designed the research on assessing heritage values offline and contributed to conceptualise the article; CB and SJ wrote the article; EB, ER and AH commented on the article and edited it; EB and AH collected data and CB, EB and AH analysed and interpreted data on heritage value assemblages in social media spaces.

Data access statement

Due to the sensitivity of the data and the legal and policy requirements of social media sites, we are not able to make supportive data available.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage (JPI CH) for funding the Deep Cities project that allowed undertaking the research presented in this article (award-id: AH/V003615/1). We also thank the Deep Cities team for their collaboration and very interesting discussions during the lifetime of the project, and all our research participants for their time and invaluable contribution. We thank John Lawson and Jenny Bruce at Edinburgh City Council, and Steven Robb and Ann MacSween at Historic Environment Scotland, for introducing us to the site and sharing their knowledge of its history. Finally, we are grateful to the Old Town Development Trust team for allowing us to join their activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chiara Bonacchi

Chiara Bonacchi is Chancellor’s Fellow in Heritage, Text and Data Mining and Senior Lecturer in Heritage, at the University of Edinburgh. She is the recipient of the Philip Leverhulme Prize in Archaeology (2022). Her research focuses on investigating the intersection between contemporary experiences and public uses of the past, identity building, social change and politics in the digital age. Her most recent book, Heritage and Nationalism: Understanding populism through big data (UCL Press 2022), is the first to leverage millions of social media data points to examine the ways in which people’s understanding of the pre-modern past shape political identities.

Siân Jones

Siân Jones is Professor of Heritage and Director of the Centre for Environment, Heritage and Policy at the University of Stirling. She is an interdisciplinary scholar with expertise in cultural heritage, as well as the role of the past in the production of power, identity and sense of place. Her recent projects focus on the practice of heritage conservation, the experience of authenticity, replicas and reconstructions, approaches to social value, the role of heritage in urban transformation, and care for heritage in the context of war. Her latest book, co-authored with Tom Yarrow, is The Object of Conservation (Routledge 2022).

Elisa Broccoli

Elisa Broccoli is Research Fellow at the University of Florence and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Stirling. She holds a PhD in Archaeology and Post-Classical Antiquities (University of Rome – La Sapienza). Her main research interests focus on Medieval Archaeology and Digital Heritage. She is also interested in different forms of public engagement with archaeology, and has experience of designing and implementing crowdsourcing projects.

Alex Hiscock

Alexander Hiscock completed an MA in Archaeology from Durham University and is currently a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, School of History, Classics and Archaeology. His work focuses on empathy and memory making in online spaces and on digital heritage co-production. Alongside this, his research interests include landscapes and identity making in the Roman North, and Rome in popular media and film. His research experience comprises historical consultancy for BAFTA and Rose d’Or winning programming from Lion Television and Sky Potato Productions.

Elizabeth Robson

Elizabeth Robson is an inter-disciplinary researcher with a professional background working internationally in community development. Her research interests include: collaborative knowledge production; people-centred methods; and participatory heritage management, placemaking, and planning processes. Her doctoral project was focused on qualitative methods for assessing the contemporary social values associated with the historic environment. From August 2023, she will be a Research Fellow at the University of Stirling, working in collaboration with the National Trust for Scotland to develop an organisational approach to social values.

Notes

1. The Deep Cities project was undertaken by a consortium of six partners, led by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural heritage (NIKU), and including the University of Stirling and The University of Edinburgh, University College London, The University of Barcelona and the University of Florence.

2. The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation is a relative measure. It ranks all the data zones and divides them into ten equally sized segments: the first decile are the 10% most deprived areas, and the tenth decile are the 10% least deprived areas.

3. Keyword combination list (case insensitive): North Canongate; Gladstone Court; New Waverley; New Street Edinburgh; Out of the Blue New Street Canongate; Old Tolbooth Wynd; Old Tolbooth market; Magdalene asylum Edinburgh; Magdalene asylum Canongate; Gaswork Canongate; Gas Work Canongate; Demarco gallery Canongate; Bathgate Park Edinburgh; Calton Road Edinburgh; Caltongate; sibbaldwalk.

4. We used the Bing sentiment lexicon (Liu Citation2022) and the NRC Emotion lexicon (Saif Citation2020).

References

- Adamson, A., L. Kilpatrick, and M. McDonald. 2016. Pints, Politics and Piety: The Architecture and Industries of Canongate. Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland. Edinburgh [ online] (Accessed Jan 29 2022). http://canmore-pdf.rcahms.gov.uk/wp/00/WP004359.pdf.

- Arrigoni, G., and A. Galani. 2019. “From Place-Memories to Active Citizenship: The Potential of Geotagged User-Generated Content for Memory Scholarship.” In Doing Memory Research, edited by D. Drozdzewski and C. Birdsall, 145–168. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1411-7_8.

- Atske, S. August 10 2022. “Teens Social Media and Technology.” In Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech [Blog] (Accessed March 07 2023). https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/.

- Barrie, C., and J. C. Ho. 2021. “AcademictwitteR: An R Package to Access the Twitter Academic Research Product Track V2 API Endpoint.” Journal of Open Source Software 6 (62): 3272. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03272.

- Bennett, T., F. Cameron, N. Dias, B. Dibley, R. Harrison, I. Jacknis, and C. McCarthy. 2017. Collecting, Ordering, Governing: Anthropology, Museums, and Liberal Government. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822373605.

- Blank, G., and C. Lutz. 2017. “Representativeness of Social Media in Great Britain: Investigating Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+, and Instagram.” American Behavioral Scientist 61 (7): 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217717559.

- Bonacchi, C. 2021. “Heritage Transformations.” Big Data & Society 8 (2): 205395172110343. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211034302.

- Bonacchi, C. 2022. Heritage and Nationalism: Understanding Populism Through Big Data. London: UCL Press.

- Bossetta, M. 2018. “The Digital Architectures of Social Media: Comparing Political Campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.S. Election.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95 (2): 471–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018763307.

- Bradley-Lovekin, T., M. Roy, and D. Sproat. 2019. Old Tolbooth Wynd 179a Canongate, Edinburgh, Archaeology and Historic Building Assessment, Unpublished AOC Archaeological report.

- Brown, S., J. Davidovic, and A. Hasan. 2021. “The Algorithm Audit: Scoring the Algorithms That Score Us.” Big Data & Society 8 (1): 205395172098386. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720983865.

- Bucher, T., and A. Helmond. 2018. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, edited by J. Burgess, A. Marwick, and T. Poell, 233–253. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473984066.n14.

- Cameron, F. R. 2021. The Future of Digital Data, Heritage and Curation: In a More-Than-Human World. London: Routledge.

- Cammaerts, B. 2015. “Technologies of Self-Mediation: Affordances and Constraints of Social Media for Protest Movements.” In Civic Engagement and Social Media: Political Participation Beyond Protest, edited by J. Uldam and A. Vestergaard, 87–110. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137434166_5.

- Costa, E. 2018. “Affordances-In-Practice: An Ethnographic Critique of Social Media Logic and Context Collapse.” New Media & Society 20 (10): 3641–3656. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818756290.

- Deep Cities. 2020. “Deep Cities” [online] (Accessed Feb 1). https://curbatheri.niku.no/.

- Dennison, E. P. 2008. “The Medieval Burgh of Canongate .” In Scotland’s Parliament Site and the Canongate: Archaeology and History, edited by the Holyrood Archaeology Project Team, 59–68. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- DeSilvey, C. 2017. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- D’Ignazio, C., and L. F. Klein. 2020. Data Feminism. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Draude, C., G. Hornung, and G. Klumbytė. 2022. “Mapping Data Justice as a Multidimensional Concept Through Feminist and Legal Perspectives.” In New Perspectives in Critical Data Studies: The Ambivalences of Data Power, edited by A. Hepp, J. Jarke, and L. Kramp, 187–216. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96180-0_9.

- Ekelund, R. 2022. “Fascination, Nostalgia, and Knowledge Desire in Digital Memory Culture: Emotions and Mood Work in Retrospective Facebook Groups.” Memory Studies 15 (5): 1248–1262. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980221094517.

- Ellison, N. B., and J. Vitak. 2015. “Social Network Site Affordances and Their Relationship to Social Capital Processes.” In The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology, edited by S. Sundar, 203–227. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118426456.ch9.

- Elsinghorst, S. 2017. “Characterizing Twitter Followers with Tidytext” [online] (Accessed Feb 16 2023). https://shiring.github.io/text_analysis/2017/06/28/twitter_post.

- Fox, N., T. August, F. Mancini, K. E. Parks, F. Eigenbrod, J. M. Bullock, L. Sutter, and L. J. Graham. 2020. ““Photosearcher” Package in R: An Accessible and Reproducible Method for Harvesting Large Datasets from Flickr.” SoftwareX 12:100624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2020.100624.

- Fricker, M. 2009. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Geismar, H. 2017. “Instant Archives?” In Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography, edited by L. Hjorth, H. Horst, A. Galloway, and G. Bell, 331–343. New York, NY and Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gibson, J. J. 1979. “The Theory of Affordances.” In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology, edited by R. Shaw and J. Bransford, 67–82. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gregory, J. 2015. “Connecting with the Past Through Social Media: The ‘Beautiful Buildings and Cool Places Perth Has Lost’ Facebook Group.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (1): 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.884015.

- Gregory, J., and S. Chambers. 2021. “Longing for the Past: Lost Cities on Social Media.” In People-Centred Methodologies for Heritage Conservation: Exploring Emotional Attachments to Historic Urban Places, edited by R. Madgin and J. Lesh, 41–64. London: Routledge.

- Hargittai, E. 2020. “Potential Biases in Big Data: Omitted Voices on Social Media.” Social Science Computer Review 38 (1): 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318788322.

- Harrison, R. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harrison, R., C. DeSilvey, C. Holtorf, S. Macdonald, N. Bartolini, E. Breithoff, H. Fredheim, A. Lyons, S. May, J. Morgan, and S. Penrose. 2020. Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv13xps9m.

- Harvard University. 2023. “Social Science One” [online] (Accessed Aug 14 2023). https://socialscience.one/.

- Hornstein, S. 2016. Losing Site: Architecture, Memory and Place. London: Routledge.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996.

- Jones, S., C. Bonacchi, E. Robson, E. Broccoli, A. Hiscock, A. Biondi, M. Nucciotti, T. S. Guttormsen, K. Fouseki, and M. Díaz-Andreu. Forthcoming. “Assessing the Dynamic Social Values of the ‘Deep City’: An Integrated Methodology Combining Online and Offline Approaches.”

- Jones, S., and T. Yarrow. 2022. The Object of Conservation: An Ethnography of Heritage Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jung, E. H., and S. S. Sundar. 2018. “Status Update: Gratifications Derived from Facebook Affordances by Older Adults.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4135–4154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818768090.

- Kennedy, L., M. Naaaman, S. Ahern, R. Nair, and T. Ratternbury 2007. “How Flickr Helps Us Make Sense of the World: Context and Content in Community-Contributed Media Collections”. In MM ‘07: Proceedings of the 15thInternational Conference on Multimedia 2007, Augsburg, Germany, September 24-29, 2007, edited by A. Hanjalic, S. Choi, B. Bailey, and N. Sebe, pp. 631–640. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1291233.1291384.

- Knoblauch, H. 2005. “Focused Ethnography”. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research 6 (3): Art. 44. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.20.

- Leonelli, S., R. Lovell, B. W. Wheeler, L. Fleming, and H. Williams. 2021. “From FAIR Data to Fair Data Use: Methodological Data Fairness in Health-Related Social Media Research.” Big Data & Society 8 (1): 205395172110103. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211010310.

- Liu, B. 2022. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02145-9.

- Lupton, D., C. Southerton, M. Clark, and A. Watson. 2021. The Face Mask in COVID Times: A Sociomaterial Analysis. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Macdonald, S. 2009a. Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi Past in Nuremberg and Beyond. London: Routledge.

- Macdonald, S. 2009b. “Reassembling Nuremberg, Reassembling Heritage.” Journal of Cultural Economy 2 (1–2): 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350903064121.

- McLaren, D., M. Roy, D. Wilson, D. Gallagher, G. R. Haggarty, A. Morrison, J. Robertson, et al. 2022. “The New Street Gasworks, Caltongate: Archaeological Investigation of a Major Power Production Complex in the Heart of Edinburgh and Its Significance in the Industrial Development of Britain.” Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports 101. https://doi.org/10.9750/issn.2056-7421.2022.101.

- Mol, A. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. London: Duke University Press.

- Morstatter, F. 2016. “Detecting and Mitigating Bias in Social Media”. 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), San Francisco, CA, USA, edited by R. Kumar, J. Caverlee, and H. Tong, pp. 1347–1348. San Francisco, CA, USA IEEE Press. https://do.org/10.1109/ASONAM.2016.7752412.

- Pink, S. 2022. “Methods for Researching Automated Futures.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (7): 747–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004221096845.

- Queensberry. 2018. “New Waverley, Edinburgh” [online] (Accessed Jan 31 2023). https://www.queensberryproperties.co.uk/projects/new-waverley/.

- Rathnayake, C., and D. D. Suthers. 2018. “Twitter Issue Response Hashtags as Affordances for Momentary Connectedness.” Social Media + Society 4 (3): 2056305118784780. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118784780.

- (RSEMA). 1830. Report of the Society for the Support of the Edinburgh Magdalene Asylum for 1827, 1828 & 1829. 1830. Printed by J. Ritchie, Edinburgh.

- Saif, M. M. 2021. “Sentiment Analysis: Automatically Detecting Valence, Emotions, and Other Affectual States from Text.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.11882.

- Scottish Government. 2020. “Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2020” [online] (Accessed Nov 09 2021). https://simd.scot/.

- Silge, J., and D. Robinson. 2016. “Tidytext: Text Mining and Analysis Using Tidy Data Principles in R.” The Journal of Open Source Software 1 (3): 37. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00037.

- Silge, J., and D. Robinson. 2017. Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach. Sebastapol, CA: O‘Reilly Media.

- Sontag, S. 2008. On Photography. London: Penguin.

- Sterling, C. 2020. “Critical Heritage and the Posthumanities: Problems and Prospects.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (11): 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1715464.

- Taylor, L. 2017. “What is Data Justice? The Case for Connecting Digital Rights and Freedoms Globally.” Big Data & Society 4 (2): 2053951717736335. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717736335.

- Thompson, T. L. 2020. “Data-Bodies and Data Activism: Presencing Women in Digital Heritage Research.” Big Data & Society 7 (2): 205395172096561. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720965613.