ABSTRACT

This article considers the concept of Illegal that is used to challenge the disciplinary constraints of authorised heritage practice. The Illegal provides a conceptual device to consider the ontological reality of the heritage world and the necessary illusion of the heritage profession. Alongside, the critical challenges to the Authorised Heritage Discourse presented by Indigenous Worlds, guerrilla restoration, People Centred Approaches, Experimental Preservation, and creative heritage practice, the tactical activism of Illegal practice is offered as an insurgent tool for transforming heritage worlds. Two recent Illegal projects, the ‘Illegal Town Plan’ and the Illegal Museum of Beyond’s ‘Objects of the Misanthropocene’ exhibition project, present speculative insouciance as a method for putting the Illegal into heritage practice.

Introduction

This article examines the role of Illegal action in authorised heritage practice, as a means of transgressing disciplinary boundaries that impose on the activities of heritage professionals. Illegal was presented by Hill (Citation1998) as a challenge to the ability of professionals to police the disciplinary boundaries of their profession. This allows for a consideration of the transformative potential of illegal activities, within other forms of resistance, that run counter to the legitimising discourse of heritage. Illegal practice provides a focused role for heritage professionals to challenge the authority of heritage in decision-making/action taking, and offers an opportunity to recentre less privileged inhabitants of heritage worlds, who lie outside of the bounds of proper action. The application of methods of creative practice, adapted as tools for heritage making, provides a mechanism for putting the Illegal into heritage practice. The contribution of speculative insouciance in two recent Illegal projects, the Illegal Town Plan and the Illegal Museum of Beyond’s ‘Objects of the Misanthropocene’ exhibition project, will be considered as an Illegal method, amongst others, of reforming authorised heritage practices.

Illegal

Actions that are identified as illegal, illicit, improper, immoral, or unethical, variously transgress laws, norms, protocol, authority, and principle (Hartnett and Dawdy Citation2013). The category shift from licit and legal, to illicit and illegal, is interwoven within the spaces of exception in regulatory frameworks for what has become normalised activity (Agamben and Attell Citation2005; Hudson Citation2020). Laws, standards, and rules of behaviour will vary over time and space and continue to be rewritten beyond the boundaries of what was previously accepted as illegal (Francesco et al. Citation2017; Somerville, Smith, and McElwee Citation2015). The term Illegal is used here to represent a method of action that aims to shift disciplinary norms, rather than necessarily transgress legal statute. This is in reference to the use of this term by Hill (Citation1998), and subsequently by Ward and Loizeau (Citation2020).

Illegal practice

The concept of the Illegal was used by Hill (Citation1998) to describe the potential for architects to disrupt the legislative framework of the architectural profession. Architects, like other professionals, reinforce disciplinary authority to resist internal criticism and external intrusion (Hill Citation1998, 34). The authority to control the designation of a world determines which people, ideas, stories, and practices can be sanctioned. This creates a disciplined place to articulate a limited range of intellectual positions, like a game played out by the agreed rules (Bourdieu Citation1998). In order to disrupt the illusion of professional mastery, and the hierarchicalness of its ordered dualities, something can be inserted between the binary opposition of the professional architect and the passive outside user (De Certeau Citation1984, 7; Hill Citation1998, 8). The Illegal professional equates to the intermediary position of the ‘fixer’, in Jackson’s ‘repair-thinking’ that reveals a view of the world from the position between the producer and the consumer, engaged in ongoing adaptations and improvisations that stabilise the familiarity of our worlds (Jackson Citation2014; Mattern Citation2018, 9).

In a similar way to the Illegal architect, the Illegal heritage professional can explore the potential of unorthodox action to perturb the authorised discourses of heritage practice. The Illegal professional, as an in-between practitioner, unrestrained by conventional professionalism, is able to question and subvert convention codes and laws (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2011, 122). The hybrid role of the Illegal professional offers an expanded set of ideas and working practices that can challenge established authorised discourses, which can be allied to common causes from inside and outside the discipline (Hill Citation1998, 16). Such an experimentation draws potential solutions from what is already there, rather than a calculated destruction in order to create something new (Moore Citation2015). The Illegal becomes a tactic of transdisciplinary entanglement. The ‘insider’ role of the Illegal heritage professional is an essential starting point to challenge accepted norms of practice in resistance to the hegemony of the authorised heritage practice.

Making heritage worlds

Professional heritage practice invents itself as a discipline with a self-productive technology of its own discourse constructed within competing modes of practice (Spivak Citation1993, 44). This provides a territorialisation of the world in which heritage practice has authority to determine what is proper and what is improper (Nancy Citation2007, 78). It creates meaning to itself and of itself which allows for problems to be created, in which heritage practice is the only proper solution (Sully Citation2015).

The Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD) as expressed by Smith is the overarching set of values, meanings, understandings, and laws that operate within the domain of heritage (Smith Citation2006, 4). The application of the AHD to the spaces and things of the human world transforms them into heritage places and objects, enforced through legal, institutional, and disciplinary procedures (De Certeau Citation1984, 117). The fabrication of a heritage place (e.g. built heritage, sites, monuments, and landscapes) occurs by transposing a terrain of fluid networks into a defined order of things stabilised by the imposition of agreed heritage rules (Shields Citation1998; Agamben Citation2009, xviii; Armstrong Citation2009, 168). The result is a place that is essentialised in the divide between the present and the past, separated from its embedded state in the complex human systems of everyday life, substituted with relationships that are proper for heritage (De Certeau Citation1984, 108). Separating categories into polarised oppositions is not a description of our being in the world, but a method of organising our action in the world (Agamben Citation2009, 4). The heritage world of the AHD does not exist in isolation, but in relation to other regulatory frameworks, imbricated and intersecting within other worlds (Agamben Citation2009, 4). Each world resisted and contested to the same extent as the violence and force required to police the sharp boundaries between them (Patel and Moore Citation2018, 202). As such, its actions are necessarily in conflict with the world making projects of other inhabitants, as a microcosm in the macrocosm of things with which humans co-produce their worlds (Connolly Citation2011, 93). Heritage practice, therefore, has no greater legitimacy, nor truth, other than that which can be secured from the hierarchies of power in designated places for the proper operation of its practice. It is a tautological process without ontological reality, which is challenged by the need to maintain the illusion of being real in the world beyond (Brey Citation2002, 65; Latour Citation2010, 114). This questions the assumed right of the heritage profession to police disciplinary boundaries, to claim authority over the production of heritage, and encourages heritage professionals to transform the discipline from a site of authority to a site of resistance (Butler Citation2006, 365; Pink Citation2012, 16).

As a response, we could erase separations in an attempt to dissolve the boundaries of heritage as a field of activity (unlikely given its obvious appeal) or expand heritage to cover all things (an attractive solution to many heritage professionals). When the boundaries around heritage are clearly articulated, they can be transgressed (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2011, 28; Heidegger Citation1971; Olsen Citation2010, 48). These boundaries cease to be a barrier to understanding, rather their critical evaluation offers a means to challenge the way the world is divided up (Ingold Citation2008). Friction at the boundaries of the AHD can ferment positive change for the disciplining mechanisms of heritage as a bounded field of polarised oppositions. The dominant narratives that stand for accounts of truth and facts about the world can be challenged in order to amplify less powerful stories that lie hidden (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2011, 240; De Certeau Citation1984). This is evident in the challenge to authorised heritage practice when confronted with Indigenous worlds, which provide perturbation to a world authorised within the North Atlantic Universals, routinely applied in debates about Western heritage practice (Trouillot Citation2002). This acknowledges the debt that many western heritage professionals owe to non-Western and Indigenous scholars, practitioners, and collaborators who inhabit distinct worlds that continue to resist the intrusion of western practice (Todd 2015). Heritage professionals, however, cannot merely look outside Western modernity for innovations that will transform their professional discipline. This responsibility remains with heritage professionals (including Western practitioners) and requires tools that are not appropriations (well-meaning or not) of other peoples’ cultural knowledge and skills to do this.

Making heritage Illegal

The purpose of putting the Illegal into heritage practice is not to claim an exclusive challenge to the Authorised Heritage Discourse nor an attempt to recolonise new domains of activism. It offers heritage professionals a focus on their own disciplinary responsibility for transformative change, and adds to the toolbox of concepts that can be deployed in common cause with other forms of resistance to the hegemony of authorised heritage practice. The status as Illegal allows certain practices to sit outside of established conventions in the way that ‘Experimental Preservation’ is presented (Otero-Pailos, Langdalen, and Thordis Citation2016). This is in line with the growing movement of critical heritage studies (Harrison Citation2013), critical speculative design (Dunne and Raby Citation2013) and critical heritage practice (Sully Citation2007, 2014; Citation2019).

Guerrilla restoration

Guerrilla action is associated with perturbations that take place outside legally sanctioned processes to create a space for dissent and protest that disrupt systems of power and control (Haley Citation1986; Hardman Citation2011). Such tactical activism provides a legitimate tool for opening up local worlds as a terrain for transformative encounters, making new assemblages possible (Hou Citation2020; Tsing Citation2015, 160). The micropolitical moments of everyday resistance can be joined to new assemblages of common cause to forge macropolitical alliances that foster enduring political movements (De Certeau Citation1984, 183). Such guerrilla action can be subsequently legitimised by changes to official policy and practice that permit, rather than prohibit, such activities (Hardman Citation2011).

As a direct comparator for authorised heritage practice, are the covert urban exploration activities of the UX (Urban eXperiment) cultural guerrilla movement ‘Untergunther’, a group of architects and historians that have carried out clandestine restoration of Paris’s built heritage. Lazar Kunstmann states in Boyer King (Citation2007) that ‘We would like to be able to replace the state in the areas it is incompetent’, which represents a response to the absence of functioning infrastructures from which informal ecologies fill the gaps with unregulated and often illegal appropriation of resources (Moore Citation2015). The perspective of authorities on these illegal professionals is that they are irresponsible subversives whose actions serve as a model for terrorists and need to be stopped (Sage Citation2007).

Since the 1990s, Untergunther has staged cultural events in underground monuments, they have rebuilt an abandoned nineteenth-century French Government bunker, and renovated a twelfth-century crypt (Sage Citation2007). In 2005, they completed a self-initiated restoration of the Panthéon’s 1850 Wagner clock. The monumental clock, which had not worked since the 1960s, was restored by professional clockmaker Jean-Baptiste Viot, and a team of ‘illegal restorers’ (Kunstmann Citation2009). Despite an initially positive response, the Centre des Monuments Nationaux attempted to prosecute four members of the Untergunther squad for criminal damage in 2007 (Murray Citation2008). This shift to categorise the guerilla restoration as illegal activity meant that Untergunther

‘. could go down in legal history as the first people ever to be prosecuted for repairing a clock … if we hadn’t restored the clock, no one else would have bothered’ (Lazar Kunstmann in Sage Citation2007). The unsuccessful legal prosecution categorises this action illicit not illegal, but the control of the responsible authorities has been undermined, and the controversy of poorly maintained heritage confronted by the cultural guerrilla action of Untergunther. In this way, these insurgent practices have the ability to expose official negligence, and provide a critique of the regulatory control responsible for the restricted use and destruction of heritage places and public spaces (Trepz Citation2008).

Creative heritage practice

The porosity of the boundaries enclosing the heritage world is tested in the divide between professional practice and non-professional participation (Sully Citation2015). This is evident in the development of the People's Centred Approaches for Conservation of Nature and Culture, the current ICOMOS, IUCN, ICCROM conservation paradigm for caring for peoples’ heritage (Wijesuriya, Thompson, and Court Citation2017). The application of people centred approaches is key to deprivileging a certain anthropocentric worldview represented by Western experts, which enables a more dispersed and diverse concept of ‘human’ to be represented in decisions about heritage. The co-produced outcomes of people centred projects are necessarily less predictable than those managed within a linear centralised expert driven process (Sully Citation2015). The controversial 2022 re-painting of Sant Cristòfol by Jesús Cees and the 2012 transformation of the Ecce Homo (Behold the Man) fresco into ‘Ecce Mono’ (‘Behold the Monkey) raises issues for People Centred Approaches (PCA) as an authorised heritage practice (Kassam Citation2022). As with other self-initiated conservation projects, whether amateur restorer Doña Cecilia Giménez can be accused of a crime against culture, or celebrated as an Illegal in-between practitioner utilising PCA, is a polarising question (Hyde Citation2016). Such unauthorised acts represent a transgression of the rules of heritage places as spheres of exclusivity, which attack the idea of the sacred space of heritage being untouchable, destroying the shared harmony of imposed order, and result in impurity, disorder, chaos, and profanity (Dekeyser Citation2021, 314). Allowing a more diverse range of people to make their own decisions about their heritage creates a series of experiments from which true innovation is possible, and as a corollary, mistakes will be made, and criticism will result. The role of the Illegal professional in such unauthorised acts may simply be to provide retroactive justifications to support the action taken and defend the outcomes produced. This differs from the intended co-production that takes place within People Centred Approaches, which aims to co-develop internally justified decision-making systems as the mechanism for defending the intended outcomes (Sully Citation2015). As such, the Illegal professional, operating inside and outside of authorised discourse, necessitates a betrayal of those worlds and as a result makes new assemblages possible (Latour Citation2015, 51).

Creative practices

The creative practice of artists and designers offers methodological tools, and provides a powerful body of work, from outside the AHD that mirrors the social benefit aspirations for Illegal heritage projects. Artwork, such as Ryan Mendoza’s installation art transformation of Rosa Parks's Chicago residence (https://www.rosaparkshouse.com) and Theaster Gates’ 12 Ballads for the Huguenot House (https://www.theastergates.com), as well as design work such as Hefin Jones’, Glofa’r Gofod (Cosmic Colliery) (http://hefinjones.co.uk), seek to engage in broader concerns of social justice, equality, and restitution within their creative projects. A recent University College London/University of Gothenburg Centre for Critical Heritage Studies, Research project ‘Hidden Sites of Heritage’, explored the tension between creative artistic and authorised heritage practice in making of urban spaces out of heritage places (Gravesen and Stein Citation2019; Sully Citation2019, Citation2022).

The Hidden Sites of Heritage project investigated the re-assembly of heritage places through the transdisciplinary intersection of art, architecture, archaeology, anthropology, conservation, performance, and design (see ). This was based on fused sympoietic practice (academic/practice, art/design and critical heritage approaches) as an attempt to create art/science worldings that are able to address broader social questions about how the human built heritage world comes into being, beyond merely tautological justifications of fixing a past in temporal isolation within the heritage places of the present (Haraway Citation2016). In juxtaposing creative artistic practice and authorised heritage practice, we are able to activate a field of dynamic transdisciplinary encounters. This provides opportunities for hybrid professionals acting in-between, rather than within the disciplinary constraints of heritage.

Speculative practice

Speculative techniques, amongst other tools, offer the Illegal heritage professional a set of creative working practices that can contest established authorised discourses. Speculations on the nature of authorised practice provide an opportunity to free practitioners from the constraints of their professional discourse by removing the consequences of their decision-making and action taking in the real world. Speculative techniques, such as Critical Speculative Design, Design for Debate, Design Fiction, Participatory Speculation, Fictioning, etc., allow the exploration of the uncertainties of everyday life and emerging worlds, in a new light using ‘fiction as method’ (Dunne and Raby Citation2013; Shaw, and Reese-Evison Citation2017). These methods for future making/world building are deployed by posing ‘What if’ questions that aim to make reality more malleable. If we see the future differently, we can alter our view on the present and engage in more affective action. As a technique, speculative practice aims to create a future so real that a shadow is cast over the present, which creates the conditions for this future to become the preferred reality (Bell and Mau Citation1971; Ward. Citation2015). Speculating about future worlds is an opportunity to think about what we want and do not want to happen and to do something about it now (Piercy, Citation1976 (2019), vii).

Speculative insouciance

In curating a certain reality, the fabrication of truths occurs equally in speculations about the past, as it does in descriptions about the future. By raising concerns about the stability of the speculative pasts routinely authorised by heritage practice, we can understand heritage truths as parables, simplified didactic stories used metaphorically to illustrate broader meaning. Speculative techniques are therefore critical tools for heritage practitioners that no longer imagine their role in recovering a lost past but are engaged in assembling the components for preferred future worlds (Harrison et al. Citation2020). In questioning the authority of privileged processes that turn certain stories into generally agreed truths, we are able to substitute the epistemic virtue, required to arrive at the best accessible approximation of truth as congruence with reality, with epistemic insouciance. This playful indifference towards the veracity of inquiry and truth production manifests as a defiant challenge to the predatory narratives of authorised knowledge production systems that tend to outcompete the truths of other worlds (Cassam Citation2018). The playfulness of speculative insouciance helps to disrupt the complex choreography of truth production, long enough for it to be reimagined into a belief in the reality of newly proposed worlds. The ‘Illegal Town Plan’ project provides an example of insurgent participatory speculation applied to reform urban design and planning practices that better support the relevant and resilient developments of a more liveable place.

The Illegal town plan

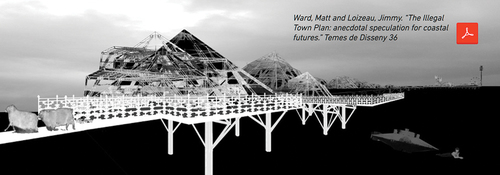

In one of the most deprived coastal towns in the UK, the Illegal Town Plan (ITP) set out to address the despair of local people, and the loss of ambition demonstrated by local planning authorities (Ward and Loizeau Citation2020). As part of this ongoing Goldsmith’s Department of Design project (2013-present), a speculation to build the world’s longest pier in Rhyl, North Wales, developed out of key relationships with local people (see ). This form of grounded speculation aims to untangle some of the wicked problems that are affecting the town, through collective reality detection and amplification creating new ‘images of the future’, to produce preferred alternative futures for Rhyl (Bell and Mau Citation1971, 18). Once initiated, the project has been used to investigate the application of an assemblage of speculative methods to support collective imagination and community development. The challenge for the Illegal designer is to move through the many encounters that straddle spaces between the ‘proper’ and ‘improper’, amplifying marginal voices to stimulate the imaginations of those in power (Law Citation2004, 14; Ward and Loizeau Citation2020, 3).

Figure 2. A speculation to re-build the longest pier in the world in Rhyl, North Wales (Jimmy Loizeau).

In the case of the pier, the architecture speculation acts as a discursive device for new social realities; gathering together people, ideas, and stories to stimulate and re-engage local action, manufacturing a feedback system that brings about social change as a present reality (Ward and Loizeau Citation2020, 9). The power of localised images of the future (the local, collective images, values and beliefs about the future economic and social prosperity of a coastal town) to catalyse social change lies in the ability to affect political systems that influence and enable change to take place (Bell and Mau Citation1971, 18). As discussions of the pier move between worlds (academic, political, and social), the idea of the pier is sustained through diverse transformations that assemble and amplify collective hopes in new ways to accommodate the desires of those involved (Ward and Loizeau Citation2020, 9). The end of the pier is known to be unstable and vulnerable to damaging changes and therefore hosts the most dynamic and experimental thinkers at the ‘University at the End of the Pier’. This is where the ‘Illegal Museum of Beyond’ can be found, forever extending away from the shoreline, just out of reach, on the far side.

The Illegal museum of Beyond

The Illegal Museum of Beyond (IMoB) is a speculative future museum that is constantly reimagined at the far edges of the Anthropocene. The IMoB curates the pre-eminent museum collection of past objects from our future worlds, representing the histories of futures already long passed that have not yet existed. Its most spectacular encyclopaedic collections have been assembled to represent our broken futures of the Misanthropocene (see ).

Figure 3. Objects of the Misanthropocene, a time travelling exhibition of insouciant Objects from the museum of Beyond online exhibition, August 2020 (Sully et al. Citation2020).

The Illegal work of the museum takes place through a lens of multiple realities, through experiments with ontological fracture, epistemic breakage, and institutional carelessness that seek to engage with more destabilised ideas of temporality and the more-than-human. The Illegal is used as a means of transformative practice alongside other methods; projected pasts/retrospective futures (Dupuy Citation2007), dabbling with time travel (Holtorf Citation2009), science fact/science fiction (Haraway Citation2016), speculative fabulation/fabrication (Dunne and Raby Citation2013), perturbation (Haley Citation1987), guerrilla (De Certeau Citation1984), profanation (Agamben Citation2007), truth and insouciance (Cassam Citation2018), broken worlds (Mulgan Citation2011). These techniques have been used to highlight the (un)certainty of authorising knowledge production in providing stories of the past and the future, by presenting a time travelling exhibition of objects from the future of the Anthropocene. The museum collections reflect objects that inhabit specific dystopian futures/other worlds, selected from fictional and non-fictional accounts of the Misanthropocene (published literature, film, music, gaming, etc.) presenting existence in various future, alternative, parallel, multiverses. Situating museum speculations in environmental humanities and ecocriticism of the Anthropocene provides a retrospective critical gaze on our uncertain present, from the perspective of a certain future (Dupuy Citation2007; Haraway Citation2015; Mulgan Citation2011).

The Misanthropocene

The Anthropocene, as a geological thought experiment, looks back from a post-apocalypse human future that collapses the future into the past (Lewis and Maslin Citation2015). Accepting that the future disaster is inevitable and mourning the lost future is part of the Anthropocene (anxieties about precarity, climate crisis, pandemic, asteroid strike, mass volcanic eruptions, cyber war/terrorism, nuclear holocaust, apocalyptical utopian/dystopian change, mass extinctions, human genocides, exterminations of multi species living, AI replacement, human-less futures, etc.) (Colebrook Citation2019; Haraway Citation2016). The Misanthropocene represents a geological apocalypse anticipated by many long-standing anxieties about unstable and uncertain futures, as a cautionary tale of its own making, in turn used to make sense of the calamity we find ourselves in now (Mulgan Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2018). The human history of living in the Misanthropocene is implicated in living on an endangered, hospitalised, damaged planet that can no longer sustain human futures. We are living out the loss of certainty about our present, and a lost belief that the future will be better.

The charismatic properties of the Anthropocene have generated a broad critique within the arts and humanities (Haraway Citation2015). The homogenisation of the human (heteropatriarchal Eurocentric, white, colonial) is a particularly problematic element of the ‘anthropos’ in the Anthropocene, whose retained privilege continues to inflict violence on both human and non-human worlds (Todd 2015, 247). This abstracted aggregate of human impact acts to mask the distinctions between those as perpetrators and those as victims (Davis and Turpin Citation2015,17; Yusoff Citation2018, 26). In colonising the terrain of the environmental crisis, the in-it-together innocent universalism of the Anthropocene reinforces the existing ecological damage to colonial relationships, alongside post-humanist tendances to erase non-European ontologies (Todd 2015, 244; Yusoff Citation2018, 104). The abstraction and delocalisation of Indigenous worlds form part of the ongoing violence of colonial practices. Indigenous knowledge systems become appropriated thoughtlessly without honouring the source of that knowledge with reciprocity, respect, and acknowledgement. This takes place where concepts such as non-human agency have become integral to the post-human responses of the Anthropocene (Todd 2015, 245).

There are many paradoxes to be resolved in inhabiting an Anthropocene, therefore the Anthropocene may be a short-lived framing for these problems, to be replaced by other terms later. Despite the many intriguing contradictions, it remains a useful concept now. Perhaps, its real value is as a readily identifiable transdisciplinary space to bring people together without having to work hard to explain why (Latour Citation2015, 49). The vast temporal and spatial scales of the Anthropocene can help to free us from its homogenising anthropocentric focus and allow us to step outside of current constraints in comprehending problems and taking action (Colebrook Citation2019; Tsing Citation2015, 19; Tsing et al. Citation2021). In situating heritage practice within the Anthropocene, the sense of loss about the past (its salvage paradigm) is replaced by a fear of losing the future, and a view of the past as a source of regret, missed opportunity, and guilt (Sully Citation2022). This presupposes a critical approach to our present that reimagines heritage practice for its disruptive potential, as an urgent matter of concern (Bennett Citation2010; Connolly Citation2011). This reinforces the need for an insurgent heritage practice that highlights the exclusions, silences, and violences evident in the designation of heritage that ‘stays with the trouble’ of deciding what heritage worlds are being cared for at the expense of which others (Haraway Citation2016; Yusoff Citation2018, 95).

Objects of the Misanthropocene

‘Objects of the Misanthropocene’ is an exhibition project initiated in 2020 to create a physical reality for the future worlds generated in the Illegal Town Plan. Hosted by the Illegal Museum of Beyond, it features objects that have travelled back to us from different future/other worlds. The Illegal method used for the Objects of the Misanthropocene project was guided by the following statements:

Speculative time-travel gives our intergenerational obligations the same kind of urgency as our obligations to our contemporary world.

The certainty of a particular future can be used to understand the uncertainty of the curated past.

Speculating about future worlds is an opportunity to think about what we want and do not want to happen and to do something about it, turning plausible and possible futures into preferable futures.

Understanding how future people, whose world is broken by us, view the moral justifications used by us in breaking their world, can affect our actions now.

What we consider to be ethical and orthodox now is unlikely to be justifiable to those in the future who will bear the consequences of our actions.

Living in the Anthropocene transforms our relationship with our pasts and our futures, it requires us to care for more-than-human relationships over extended non-human time scales.

The process was developed using transdisciplinary experimental online exchanges during the 2020 UK COVID-19 lockdown. Participants from UCL Slade School of Fine Art and Institute of Archaeology, the Architectural Association School of Architecture, Goldsmith’s Department of Design, and beyond, contributed to the fabulation and fabrication of the exhibits. The online workshops resulted in an online exhibition ‘The Objects of the Misanthropocene, A Time Travelling Exhibition of Insouciant Objects from the Museums of Beyond’, which opened in August 2020 (https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk/online-exhibition). This was subsequently developed into a Temporary Exhibition at the UCL Institute of Archaeology and Slade School of Fine Art, January–September 2022; ‘Objects of the Misanthropocene: A Time-Travelling Exhibition from the Illegal Museum of Beyond’ (https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk/ioa-slade-exhibition) (Sully et al. Citation2020).

This method was repeated for the UCL Octagon Gallery exhibition ‘Objects of the Misanthropocene; discovering future worlds’ September 2022 – February 2023 (https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk/octagon-gallery-exhibition).

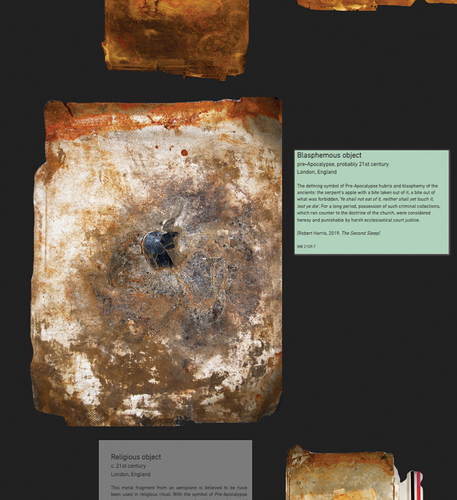

Archaeological remains of an iPad

An example of this approach is the Archaeological remains of an iPad, which has featured in each version of the exhibition, initially in the online exhibition as Exhibit 3.1, Exhibition Room 3, within the theme of ‘Technology: misuse and malfunction’ (see )

Figure 4. Exhibit 3.1. Archaeological remains of an iPad. The object page partial sections screenshots (https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk/3–1-ipad) (Sully et al. Citation2020).

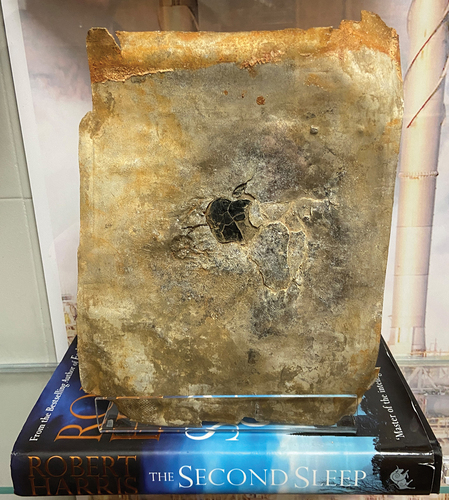

The fabricated object is composed of a deconstructed iPad, artificially aged to create the appearance of an archaeologically recovered object. The exhibit confronts the museum visitor with a familiar object (an iPad) in an archaeological state, with a surprising curatorial interpretation. This helps to create a perturbation in our familiar world that opens up the possibility of conceiving the world differently, and provides an opportunity to confront the reality of other worlds interwoven with our own reality.

The exhibit inhabits a future that is our broken world described in (Harris’s Citation2019) bestselling novel ‘The Second Sleep’ (see ). This is a world after the Apocalypse of 2025 CE, a catastrophe that induces savage resource wars and mass human genocide. In the novel, the world in recovery resembles a theocratic Medieval Britain, small religious communities and agrarian economies. The discovery of ancient, but technologically sophisticated artefacts, points to a past that has been erased from the memories of the post-apocalypse society. Access to and possession of knowledge of the pre-apocalypse world is considered to be a crime, counter to the doctrine of the church, and a heresy to be punished by harsh ecclesiastical court justice. Apple products play a key role in revealing the horrors of inter-human violence committed in establishing the stable society experienced in the novel. The focus on the Apple logo brings inevitable comparisons to the expulsion from the Garden of Eden and forbidden access to illicit knowledge (Harris Citation2019, 23).

Figure 5. Exhibit 8, Archaeological remains of an iPad temporary exhibition at UCL Institute of Archaeology and Slade School of Fine Art, January–September 2022; ‘Objects of the Misanthropocene: a time-travelling exhibition from the Illegal museum of Beyond’ (https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk/ioa-slade-exhibition) (Sully et al. Citation2020).

The speculative insouciant method of the time travelling exhibit relies on the believability of the future world and the credibility of the exhibit to a contemporary audience. Mulgan explores the moral implications of broken futures in a series of publications that utilise a certain understanding of a future world to affect current ethical thinking in surprising ways (Mulgan Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2018). This version of the heuristics of fear populates the consequences of our current decisions in the everyday lives of future people, whose world is broken by us (Dupuy Citation2007; Mulgan Citation2018). Conceiving, fabricating, translating, and presenting the exhibits represents a reification of these future worlds that can be directly experienced.

The process of transforming newly created objects into museum exhibits involved a theatrical performance of the museumification process; registration, documentation, loan agreements, condition reports, museum quality handling/transport/packaging/mounting, best practice presentation processes used to authenticate the time-travelling objects as ‘real’ museum exhibits. This forms part of the suspension of disbelief about the less believable elements of the exhibits, such as the time travel from far distant futures/alternative universes. The exhibit is interpreted by diverse curatorial voices (present/future curators, curatorial voices from other worlds, non-human and non-animate curators of the featured worlds), which reveal contradictory descriptions about the exhibits and the worlds that they inhabit. This seeks to retain the multiple interpretations that attach to material culture that aims to destabilise the certainty of a singular truth about an object. These curatorial perspectives engage with the trans-temporal misunderstandings that occur in the translation between worlds. This provokes questions about which misinterpretation of the Misanthropocene we can trust, in relation to which unconvincing truth most matches our own delusions, interests, and values. This reflects a contemporary experience of a post-truth world, less based on evidence and more on prejudice, and raises concerns about the stability of the speculative pasts routinely authorised by museums, in a juxtaposition with the reality of our speculations about the future.

In this example, the interpretation includes both literal and fanciful descriptions of the object (‘an iPad cover’, ‘blasphemous object’, ‘votive object’). The exhibition label from a ‘Mid-Anthropocene human curator’ is written by Father Christopher Fairfax, a character in Harris’s novel;

“Archaeological Remains of an iPad, Addicott St. George, Wessex, Year of Our Risen Lord 1468 (0003493 CE). The serpent’s apple with a bite taken out of it, commonly found on a range of pre-Apocalypse relics, was once the defining symbol of arrogance and blasphemy. For a long period, possession of such criminal objects ran counter to the doctrine of the church and were punishable by harsh ecclesiastical court justice. ‘Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall yet touch it, lest ye die’. (Genesis 3:3 in Harris Citation2019, 55). IMoB 2109.7 (see ).

Figure 6b. Exhibition label from the UCL octagon gallery exhibition ‘Objects of the Misanthropocene; discovering future worlds’ September 2022- February 2023 (https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk/octagon-gallery-exhibition).

The specialist skills of heritage practitioners are key in creating an authentic experience that matches the expectations of visitors to a museum exhibition. The authentication comes from the performance of authorised practice guided by peer-imposed professional codes and regulations by which the practitioners police themselves (Sease Citation1998, 98). Linking object curation and interpretation information with administrative files, such as loan files and condition reports, establishes a comprehensive meaning-making network for visitors to understand the material and managerial meta-context of the collection beyond the exhibition narrative. The same heritage performance is used in the fabrication of authorised heritage places and objects to provide an authentic visitor experience of the past (Holtorf Citation2009). The authorised practice of heritage is inverted in the exhibition within an ‘Illegal’ framing to move inside and outside the normalised constraints for proper practice (Hill Citation1998).

Conclusion

This article sets out to introduce the concept of Illegal practice into heritage as a conceptual device to challenge the AHD. The role of creative practice is explored to provide tools, such as speculative insouciance, which can be applied by the Illegal heritage professional in their work to disrupt orthodox heritage practice. The case studies are intended as examples of how this concept can be applied to critical heritage projects. Putting the Illegal into heritage practice provides a device to test the ontological reality of the heritage world, and the porosity of its boundaries. The presumed ability of the heritage profession to control the designation of what is illegal and improper, from what is legal and proper, secures a privileged place for the production of authorised heritage. In this circularity, there is a central role for the heritage professional in safely managing the processes formulated to ensure a proper approach to heritage. This, in turn, maintains the necessary illusion of the profession. The heritage industry (in the reification/administration/actualisation of heritage objects and places) operates within a specific discourse that will continue to be asserted in debates about the legacy of the past in contemporary world making. This does not need to be a reactionary or conservative process, looking to maintain established hierarchies by emphasising consensus, stability, and tradition, rather it can be a way of challenging the becoming of the world, making it, and remaking it (Agamben Citation2009; Jean-Luc Citation1991; Nancy Citation2007). This allows for innovative, improvisational, opportunities for political action to influence the making of less damaging, more-liveable, more-than-human worlds (Haraway Citation2016, 102).

The illusory nature of the bounded heritage world is clearly visible in an examination of the fabrication of its tautological boundaries. Rather than police these indefensible borders, the authority of the heritage professional can be dissolved into a participation in the lived experience of others, in ways that avoid re-colonising other worlds and resist new separations and violent exclusions (Tsing Citation2015, 258; Yusoff Citation2018). The Illegal professional, acting in-between and beyond disciplinary rules, can transgress conventional ideas and practices, disrupt internal hierarchies of control, and challenge hegemonic truth production systems (Hill Citation1998). In the resulting flux of authorising narratives, multiple ambiguous readings of heritage discourses can emerge. In so doing, we can understand heritage truths, more as parables, in the flow between constructed facts and inter-subjective fictions (Haraway Citation2016; Latour Citation1988, Citation1996, Citation2005).

Rather than precarity and controversy being seen as avoidable misunderstandings, they provide a mode of exploration for a creative response to inhabiting uncertain heritage worlds with generosity and curiosity (Harrison Citation2013; Ingold Citation2013; Latour Citation2015; Morton Citation2013). Therefore, inter-agential concatenation, conflict, and friction can be embraced as the matters of concern, rather than as problems that need to be avoided (Connolly Citation2011, 27). Heritage practice becomes the uncertain and indeterminate act of caring for the multi-plurality and temporal flows of agents that inhabit the world (Haraway Citation2016, 146). Central to Illegal heritage practice is the elevation of humility and doubt over certainty and hubris of professional arrogance (Cassam Citation2018). As a counter point to the egocentric reinforcements of privileged specialists secure in their expertise, the lack of professional certainty makes heritage choices only credible when subject to broader justifications. Some provisional certainties can be secured from uncertainty, by asking diverse questions in hybrid fora, which enables change in unforeseeable ways. This requires creative listening to stories told in otherwise muted registers that avoid human exceptionalism, to detect previously unrealised common agendas (Barad Citation2007; Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2011, 28). From this, it is possible to make common cause with other human, non-human, and non-animate actors to co-create more-liveable more-than-human worlds, co-deciding with those who will bear the precarity of the consequences (Haraway Citation2016; Yusoff Citation2018). As such, world-making collaborations are good for some but not all, the benefits need to be identified to compensate for what is lost (Tsing Citation2015, 255). The aim becomes making preferable good enough worlds that are permanently provisional (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe Citation2011, 9).

The political task of the coming generation becomes profaning the unprofanable (Agamben Citation2007, 92). This requires the unmaking of conditions of separation in collective acts of resistance, which embrace openness and celebrate the incompatible, rather than striving for general consensus and resolving conflict. This may provide a response to a fundamental desire to humanise the uncaring universe and provide new ways of imagining a ‘reparation ecology’, living modestly without the strategies of capitalist ecologies in the construction of polarised oppositions, such as nature/culture, mind/body, human/non-human, man/woman, white/non-white, past/present (Patel and Moore Citation2018, 211). These are operational tools that we can use in making a world in which more of us have the possibility of happiness (Connolly Citation2011, 21).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of staff and students at UCL and Goldsmiths for their enthusiastic participation in the ongoing projects. We wish to thank Cecile Graveson, Katherine Beckwith, Ariel Li Xiaozhou, Aparna Dhole for their creative action. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments that have greatly improved the published version. Dean Sully gratefully acknowledges the financial support from the UCL Centre for Critical Heritage Studies and the Institute of Archaeology for the Illegal Museum of Beyond.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dean Sully

Dr Dean Sully is Associate Professor in Conservation at University College London Institute of Archaeology, where he coordinates the MSc in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums. He is a coordinator of the Centre for Critical Heritage Studies (CCHS) and the Curating the City Research Cluster, National Trust’s Conservation Advisor for Archaeological Artefacts, and Emeritus Scientist in Residence at the Slade School of Art

Matt Ward

Matt Ward is Professor of Design at Goldsmiths, where he has held leadership positions for 18 years. His work engages in a wide range of topics from speculative design to radical pedagogy. He’s a practicing designer and writer whose work searches for meaning in the construction of the extraordinary through the reconfiguration of everyday life. He’s held numerous academic roles across the world, including; Visiting Professor at the Designed Realities Lab at The New School, Academic Advisor at Lasalle School of Art and Design in Singapore and External Examiner at the Royal College of Art.

Jimmy Loizeau

Jimmy Loizeau’s practice explores design through various approaches. The Audio Tooth Implant and The Afterlife Project explored the role of technology and our relationship to it through work that continues to be exhibited internationally. The Illegal Town Plan explores inclusive strategies for local engagement through ‘speculative town planning schemes’ that mediate community engagements with local government. Since 2015, Loizeau has been working with refugee communities in France and Greece initiating numerous mapping and media collaborations that explore the lives of people who have been forced to leave their countries.

References

- Agamben, G. 2007. Profanations. New York: Zone Books.

- Agamben, G. 2009. “The Coming Community.” In Theory Out of Bounds, edited by S. Buckley, M. Hardt, and B. Massumi (Eds). Vol. 1. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Agamben, G., and K. Attell, translated by by. Kevin Attell. 2005. State of Exception. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226009261.001.0001.

- Armstrong, P. 2009. Reticulations: Jean-Luc Nancy and the Networks of the Political. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bell, W., and J. A. Mau, eds. 1971. The Sociology of the Future: Theory, Cases, and Annotated Bibliography. New York: Russell Sage.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1998. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Boyer King, E., 2007. ’Cultural guerrillas’ Cleared of Lawbreaking Over Secret Workshop in Pantheon. The Guardian Newspaper, UK. Mon 26 Nov 2007. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/nov/26/france.artnews.

- Brey, J. 2002. Tautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism: An Onto-Theological Approach. Lincoln: Writers Club Press.

- Butler, B. 2006. “Heritage and the Past Present.” In Handbook of Material Culture, edited by C. Tilley, W. Keane, S. Kuechler, M. Rowlands, and P. Spye, 463–479. London: Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607972.n30.

- Callon, M., P. Lascoumes, and Y. Barthe. 2011. Acting in an Uncertain World, an Essay on Technical Democracy. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Cassam, Q. 2018. “Epistemic Insouciance.” Journal of Philosophical Research 43:1–20. https://doi.org/10.5840/jpr2018828131. Online First: August 29, 2018.

- Colebrook, C. 2019. “The Future in the Anthropocene: Extinction and the Imagination.” In Climate and Literature (Cambridge Critical Concepts, 263-280), edited by A. Johns-Putra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108505321.017.

- Connolly, W. E. 2011. A World of Becoming. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Davis, H., and E. Turpin Eds. 2015. Art in the Anthropocene Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. Open Humanities Press. http://openhumanitiespress.org/books/art-in-the-anthropocene.

- De Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dekeyser, T. 2021. “Dismantling the Advertising City: Subvertising and the Urban Commons to Come.” EPD: Society and Space 39 (2): 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775820946755.

- Dunne, A., and F. Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Dupuy, J.-P. 2007. “Rational Choice Before the Apocalypse.” Anthropoetics XIII (3): fall 2007/Winter 2008.

- Francesco, C., H. Tim, H. Ray, C. Francesco, H. Tim, H. Ray, Eds. 2017. The Illicit and Illegal in Regional and Urban Governance and Development. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315317663.

- Gravesen, C., and R. Stein. 2019. Pattern Language. New York: Circadian Press.

- Haley, J. 1986. The Power Tactics of Jesus Christ and Other Essays. 2nd ed. New York: Crown house publishing ltd.

- Haraway, D. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hardman, M., 2011. Understanding Guerrilla Gardening: An Exploration of Illegal Cultivation in the UK. School of Property, Construction and Planning, Birmingham City University Working Paper Series No. 1. https://bcuassets.blob.core.windows.net/docs/CESR_Working_Paper_1_2011_Hardman.pdf.

- Harris, R. 2019. The Second Sleep. London: Hutchinson.

- Harrison, R. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harrison, R., C. DeSilvey, C. Holtorf, S. Macdonald, N. Bartolini, E. Breithoff, H. Fredheim, et al. 2020. Heritage Futures Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices. London: UCL Press.

- Hartnett, A., and S. L. Dawdy. 2013. “The Archaeology of Illegal and Illicit Economies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42:37–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155452.

- Heidegger, M. 1971. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Harpers and Row.

- Hill, J. 1998. The Illegal Architect. London: Black Dog Publishing Ltd.

- Holtorf, C. 2009. “On the Possibility of Time Travel.” Lund Archaeological Review 15 (2009): 31–41.

- Hou, J. 2020. “Guerrilla Urbanism: Urban Design and the Practices of Resistance.” Urban Design International 25 (2): 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00118-6.

- Hudson, R. 2020. “The Illegal, the Illicit and New Geographies of Uneven Development.” Territory, Politics, Governance 8 (2): 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1535998.

- Hyde, R. 2016. “Monkey Jesus.” In Experimental Preservation. London Meeting: Projects, edited by J. Otero-Pailos, E. Langdalen, and T. Arrhenius, 156. Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers.

- Ingold, T. 2008. “Bindings Against Boundaries: Entanglements of Life in an Open World.” Environment and Planning A 40 (8): 1796–1810. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40156.

- Ingold, T. 2013. Making Anthropology, Archaeology, Art, and Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Jackson, S. J. 2014. “Rethinking Repair.” In Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, edited by T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, and K. Foot, 221–239. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jean-Luc, N. 1991. The Inoperative Community. Theory and History of Literature Volume 5, vii–xli. London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kassam, A., 2022. ‘Discordant’: Unauthorised Chapel Revamp Lands Spanish Artist in Trouble. The Guardian News Website. 8 April 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/08/spanish-chapel-artist-murals-jesus-cees-sant-cristofol.

- Kunstmann, L. 2009. Pantheon, User’s Guide. Ruhe Production UX Films. https://vimeo.com/51365068.

- Latour, B. 1988. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 1996. Aramis or the Love of Technology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B. 2010. On the Modern Cult of Factish Gods. London: Duke University Press.

- Latour, B. 2015. “Diplomacy in the Face of Gaia Bruno Latour in Conversation with Heather Davis.” In Art in the Anthropocene Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, edited by H. Davis and E. Turpin, 42–55, London: Open Humanities Press.

- Law, J. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science. London & New York: Routledge.

- Lewis, S. L., and M. A. Maslin. 2015. “Defining the Anthropocene.” Nature 519 (7542): 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258.

- Mattern, S. 2018. “Maintenance and Care.” Places Journal, (2018): November2018. https://doi.org/10.22269/181120.

- Moore, H. L. 2015. “Global Prosperity and Sustainable Development Goals.” Journal of International Development 27:801–815. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3114.

- Morton, T. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: university of Minnesota Press.

- Mulgan, T. 2011. Ethics for a Broken World, Imagining Philosophy After Catastrophe. Durham: Acumen. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780773594746.

- Mulgan, T. 2014. “Ethics for Possible Futures.” The Aristotelian Society Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society cxiv (1pt1): 57–73. Part 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9264.2014.00364.x.

- Mulgan, T. 2018. “Answering to Future People: Responsibility for Climate Change in a Breaking World.” Journal of Applied Philosophy 35 (3), August. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12222.

- Murray, C. 2008. “Clandestine Encounter: The AJ Speaks to Guerilla Restoration Group, the Untergunther.” Architects Journal, February 20. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/clandestine-encounter-the-aj-speaks-to-guerilla-restoration-group-the-untergunther.

- Nancy, J.-L. 2007. The Creation of the World or Globalization. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Olsen, B. 2010. In Defence of Things Archaeology and the Ontology of Objects. Lanham: Altimira Press.

- Otero-Pailos, J., E. Langdalen, and A. Thordis. 2016. Experimental Preservation. Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers.

- Patel, R., and J. W. Moore. 2018. History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. London & New York: Verso. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520966376.

- Piercy, M. 1976 (2019). Woman on the Edge of Time. London: Delray.

- Pink, S. 2012. Everyday Life, Practices and Places. Los Angeles: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250679.

- Reynolds, R. 2008. On Guerrilla Gardening. London: Bloomsbury.

- Sage, A., 2007. ‘Underground ‘Terrorists’ with a Mission to Save City’s Neglected Heritage’, The Times, 29 September 2007, 42.

- Sease, C. 1998. “Codes of Ethics for Conservation.” International Journal of Cultural Property 7 (1): 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739198770092.

- Shaw, and Reese-Evison. 2017. Fiction as Method. Sternberg Press.

- Shields, R. 1998. Lefebvre, Love and Struggle, Spatial Dialectics. London: Routledge.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. Oxon & New York: Routledge.

- Somerville, P., R. Smith, and G. McElwee. 2015. “The Dark Side of the Rural Idyll: Stories of Illegal/Illicit Economic Activity in the UK Countryside.” Journal of Rural Studies 39:219–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.12.001.

- Spivak, G. C. 1993. Outside the Teaching Machine. New York & London: Routledge.

- Sully, D., edited by 2007. Decolonising Conservation: Caring for Maori Meeting Houses Outside New Zealand. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Sully, D. 2015. Conservation theory and practice: Materials, Values, and People in Heritage Conservation In edited by C. McCarthy Volume 4: Museum Practice: Critical Debates in the Museum Sector. International Handbook of Museum Studies, 1–23. Sydney: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sully, D. 2019. “Unheritaging Hidden Sites of Heritage.” In Cecilie Gravesen and Robin Stein Pattern Language, 13–15. New York: Circadian Press.

- Sully, D. 2022. “Universities Curating Change at Heritage Places in Urban Spaces.” In Co-Curating the City: Universities and Urban Heritage Past and Future, edited by C. Melhuish, H. Benesch, D. Sully, and I. M. Holmberg (pp. 43–65). London: UCL Press.

- Sully, D., C. Gravesen, K. Beckwith, and L. Xiaozhou, 2020. Objects of the Misanthropocene A Time-Travelling Exhibition from the Museums of Beyond. https://www.illegalmuseumofbeyond.co.uk.

- Trepz, D. 2008. Untergunther and the Pantheon Clock, Paris, November 3, 2008. http://www.ugwk.eu/.

- Trouillot, M.-R. 2002. “North Atlantic Universals: Analytical Fictions, 1492-1945.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 101. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-101-4-839

- Tsing, A. L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873548.

- Tsing, A. L., J. Deger, A. Keleman Saxena, and F. Zhou. 2021. Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.21627/2020fa.

- Ward, M. 2015. “Rapid Prototyping Politics; Design and the Dematerial Turn.” In Transformation Design; Perspectives on a New Design Attitude, edited by W. Jonas, 227–245. Basel: Birkhauser. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783035606539-017

- Ward, M., and J. Loizeau. 2020. “The Illegal Town Plan: Anecdotal Speculation for Coastal Futures.” Temes de Disseny 36 (36): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.46467/TdD36.2020.90-113.

- Wijesuriya, G., J. Thompson, and S. Court. 2017. “People-Centred Approaches: Engaging Communities and Developing Capacities for Managing Heritage.” In Heritage, Conservation and Communities Engagement, Participation and Capacity Building, edited by G. Chitty, 34–50. London: Routledge.

- Yusoff, K. 2018. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/9781452962054.