ABSTRACT

The management of cultural heritage is no longer exclusive to heritage professionals. The engagement of various stakeholders, particularly underrepresented groups in communities, is crucial to promote inclusiveness in heritage management practices. As future decision-makers, youth are vital to be engaged, yet their participation remains at a low level due to the underestimation of youth capacities and a lack of motivation among youth. Little research has been done to comprehensively conceptualise youth participation and frame it in the context of cultural heritage management. To fill this gap, an integrative literature review was conducted using academic and grey literature from participatory urban planning, design, governance, and heritage management fields. The results show that existing theories have made valuable insights into approaching youth participation by identifying the definition and roles of youth, levels of participation, and methods of engagement. However, they have so far failed to fully address the fluid nature of youth engagement and lack reflections from youth perspectives towards their initiatives to participatory practices. Drawing on the results, we propose a new conceptual framework consisting of four dimensions: purpose, positioning, perspectives, and power relations, which define youth participation theoretically and methodologically in cultural heritage management.

1. Introduction

The management practices of cultural heritage are no longer exclusive to heritage professionals (Harrison and Rose Citation2013; Landorf Citation2009; Roders Ana and Van Oers Citation2011). The collaboration and participation with multiple stakeholders, particularly the engagement of communities, social groups, and individuals have contributed to building more inclusive and democratic societies, fostering effective management processes of cultural and natural heritage, and promoting sustainable development of the living environment (Bandarin and van Oers Citation2012; Ginzarly, Houbart, and Teller Citation2019; Guzmán, Roders, and Colenbrander Citation2017; Loes, Pereira Roders, and Bernard Citation2013; Van and Pereira Roders Citation2012). Hence, the notion of inclusiveness has emerged as a prominent issue and has been aligned with the changing definition and discourse concerning cultural heritage, as well as the evolving management approaches outlined in supranational and regional policies (Gentry and Smith Citation2019; Waterton and Smith Citation2010; Waterton, Smith, and Campbell Citation2006).

The definition of cultural heritage has no longer been limited to the materialisation and fetishism of tangible values led by the official narratives and the predefined hierarchy of heritage values (Harrison Citation2015; Smith Citation2006; Winter Citation2013). Cultural heritage is argued to be a dynamic and contested concept shaped by social, political, and economic forces (Heras et al. Citation2019; Roders Ana Citation2019), and is recognised as a cultural process that engages with acts of remembering that aim to understand the past and present (Harrison and Rose Citation2013; Waterton, Smith, and Campbell Citation2006). Such arguments have been advocated by scholars of Critical Heritage Studies (CHS), which seek to broaden the definition of heritage to include diverse perspectives and voices, including those traditionally marginalised or excluded (Gentry and Smith Citation2019; Waterton, Smith, and Campbell Citation2006; Witcomb and Buckley Citation2013). Rather than imposing a predominated interpretation of cultural heritage, it is highlighted to recognise the contested values attached to cultural heritage through active community involvement (Harrison and Rose Citation2013). The Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD), which is often shaped by nationalism and national identity to recognise the role of experts and authorities, has remained the dominant approach in current heritage management practices (Gentry and Smith Citation2019; Smith Citation2006; Smith, Morgan, and Van Der Meer Citation2003). Their approaches inadequately recognise the legitimacy of underrepresented community groups, resulting in fragmented management processes and disparities among various stakeholders (Gentry and Smith Citation2019). Thus, the challenges to promoting inclusiveness in dominated heritage management discourse make it vital to engage diverse social groups.

The participation of local communities is therefore necessary to ensure that heritage is managed in a way that reflects diverse values, meanings, and perspectives so that the ethics of heritage management itself is open to renegotiation and redefinition, further helps to address power imbalances, and promotes democratic and inclusive decision-making processes (Hodges and Watson Citation2000; Olsson Citation2008; Waterton and Smith Citation2010). The engagement of multiple stakeholders, especially those who lack a direct voice in decision-making, is even more challenging and critical (Chirikure and Pwiti Citation2008; De and Dimova Citation2019). As one of the underrepresented groups, young people have their unique narratives regarding cultural heritage, yet their voices are less heard during decision-making processes.

The younger generation possesses unique perspectives and values associated with heritage sites and landscapes, distinct from those of previous generations (Manal and Jordan Srour Citation2021; Del; Baldo and Demartini Citation2021). Their interpretation of cultural heritage contributes significantly to the diversity and complexity of its values (Halu and Gülçin Küçükkaya Citation2016). The involvement of youth in the decision-making processes can contribute to rebalancing the power structure (Smith Citation2006) and fostering a more democratic and inclusive approach to heritage management systems (Bajec Citation2019; Madgin -David, Webb -Pollyanna, and Tim Citation2016; Winn Citation2012).

The United Nations defines youth to include young people aged between 15–24 years old, thus encompassing both teenagers and young adults (Nations Citation1981). The complex age composition of this social group presents challenges in understanding their diverse characteristics and needs (UNICEF Citation1989; B. N.; Checkoway and Gutiérrez Citation2012). The World Heritage Committee has declared that young people, as the agents of social change and the decision-makers of the future, are a crucial group to be engaged, especially in the management processes of cultural heritage (UNESCO Citation2014). Since the First World Heritage Youth Forum held in 1995, numerous initiatives have emerged to foster the connection between youth and cultural heritage, facilitating them to establish their cultural identity and take ownership through their personal narratives (UNESCO Citation2002, Citation2017).

Yet, youth participation in cultural heritage management has been rather limited. Young people have not been actively engaged in decision-making and their level of participation remains relatively low (Madgin -David, Webb -Pollyanna, and Tim Citation2016). Youth have mainly been informed or educated through the predominated heritage discourse (Mastura, Md Noor, and Mostafa Rasoolimanesh Citation2015b; Waterton and Smith Citation2010), without having the opportunities to generate their own interpretations of cultural heritage values (Manal and Jordan Srour Citation2021). Due to a lack of willingness and awareness to be engaged in heritage management, young generation struggles to establish self-motivation necessary for active participation in decision-making processes (Janković and Mihelić Citation2018). There exist multi-faceted barriers and challenges, including social, political, administrative, and economic aspects, that lead to the limitation of youth participation in cultural heritage management.

Considering the developing social-psychological status of young people, Frank (Citation2006) has summarised four societal views towards youth, in terms of their developmental capabilities, perceived vulnerability, limited citizenship rights, and the potential of their romantic yet impractical initiatives (Percy-Smith and Burns Citation2013; Jane; Strachan Citation2018). On one hand, these societal views have recognised youth as citizens-to-be (Chawla Citation2002; Shier Citation2001), who have the rights and potential to participate in decision-making (Checkoway Citation2011; Kudva and Driskell Citation2009). On the other hand, these views are derived from total adults’ perspectives (Head Citation2011), resulting in the underestimation of youth capacities, which consequently restricts youth’s access to information and resources that could enhance their engagement in policymaking processes (Derr and Tarantini Citation2016; Wilks and Rudner Citation2013). The lack of legislative support for youth participation is also evident from an economic standpoint. Specifically, there is a scarcity of volunteering opportunities and a low rate of youth employment within the realm of cultural heritage management (Menkshi et al. Citation2021). While supranational policies have increasingly emphasised the significance of youth engagement in supporting democratic and sustainable development, those policies have been argued to be Eurocentric and are predominantly influenced by the Western discourse of democracy (Bambara, Wilson, and McKenzie Citation2007; Giroux Citation2009). This is particularly evident within the context of the Global South, where such one-fits-all policies have been reported insufficient for localising youth participation into heritage management systems (Chirikure et al. Citation2010; Fairweather Citation2006). It is crucial to consider and respect the diverse political systems present in different contexts before institutionalising youth participation in decision-making (Witcomb and Buckley Citation2013).

Specifically, it is essential to recognise that youth is not a homogenous social group (Evans Citation2008). In different contexts, there are inherent heterogeneity and inequalities within the group of youth, which leads to diverse representations of the youth’s identity and their surrounding environments (Cushing Citation2015; Richards-Schuster and Pritzker Citation2016). These diverse characteristics and narratives within the younger generation can be further reflected through their individual interpretation of cultural heritage and their participation in management processes (Farthing Citation2012; McAra Citation2021). Therefore, it is critical to conceptualise youth and their engagement before involving them in the decision-making processes of cultural heritage management. This will enable a more nuanced and comprehensive approach to incorporating youth perspectives and contributions.

Existing theories have cast light on the topic of youth participation within the fields of urban planning, urban design, and urban governance (Simpson Citation1997; R.; Hart Citation1992; Shier Citation2001; B. N.; Checkoway and Gutiérrez Citation2012). These theoretical contributions are valuable to understand the role of youth (Head Citation2011), the methods of engaging youth (Bartlett Citation2002), and the nature of youth participation (Derr and Tarantini Citation2016). However, based on primary research, there is a very limited number of academic studies on youth participation in the context of cultural heritage and a lack of theoretical approach to conceptualising the involvement of youth in heritage management processes. Thus, it would be valuable to integrate youth participation theories from participatory urban planning, design, and governance into the heritage management discourse to provide a comprehensive definition of youth, their participation, and their roles in heritage management from a theoretical perspective. Through an integrative literature review, this paper aims to construct a conceptual framework to approach youth participation in the discourse of cultural heritage management based on the following research questions:

What is the role of youth in cultural heritage management and how can youth be engaged in the decision-making according to the state-of-the-art literature?

What dimensions should be considered when integrating youth participation in cultural heritage management?

2. Materials and methods

To conduct a comprehensive review and synthesis of existing theories of youth participation, an integrative literature review was employed in this paper (Torraco Citation2005). The review incorporated research findings and evidence from a range of resources, including academic literature and grey literature, in order to minimise potential bias and to provide a holistic overview of this cross-disciplinary topic.

2.1. Publication collection process

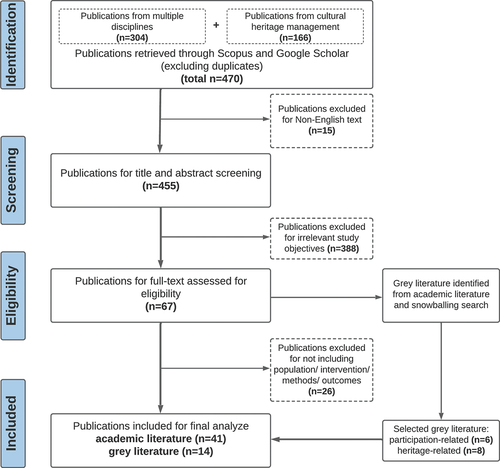

To collect significant publications, we conducted two different literature searches, within the database of Scopus and Google Scholar. The first search focused on collecting literature from multiple disciplines, using a set of search strings finalised as TITLE-ABS-KEY ((‘youth’ or ‘young*’ or ‘teenager’) and (‘participat*’ or ‘engage*’ or ‘involve*’) and (‘urban planning’ or ‘urban design’ or ‘urban governance’)). A total of 304 publications were collected from the first search. Another search strings which focused on the discourse of cultural heritage (‘heritage’ and (‘management’ or ‘preservation’ or ‘conservation’)) were applied in the second search within the same database. This retrieval returned 166 publications. In total, 470 publications were collected for screening (). A set of inclusion criteria was adopted to critically appraise the most related literature that can lead to the construction of the conceptual framework. The inclusion criteria included the following review elements: (1) population: young people aged between 10–24 (the age range of youth is expanded to obtain more related publications); (2) interventions: any level of youth participation within related disciplines; (3) methods: participatory methods targeted for youth; (4) outcomes: theoretical findings or case studies. After that, the ten most-relevant papers were selected through a snowballing procedure to collect other highly relevant sources of literature (Wohlin Citation2014). A final list of 41 academic literature was analyzed in-depth to answer the research questions.

To conceptualise youth participation from supranational level and policy-related perspectives, grey literature in the format of policy documents and/or reports adopted by international governmental, non-governmental organisations, and heritage institutions were also collected. The collection process started with the identification of grey literature mentioned in selected academic literature. Then, through the forward and backward snowballing method, other related policy documents and reports were collected (Wohlin Citation2014). As a result, 14 grey literature sources that fully focus on youth, of which six are related to participation and eight to cultural heritage, were selected for final analysis.

2.2. Data analysis

Thematic analysis is adopted in this paper to review and synthesise the data derived from academic and grey literature. As a qualitative research method widely utilised for analysing textual data, thematic analysis facilitates the abstraction of main- and sub-themes from a complex and detailed dataset (Joffe and Yardley Citation2003). Given its suitability for constructing a conceptual framework, thematic analysis is particularly apt for this paper’s objectives. During the initial phase of literature review, a semantic approach was applied to analyse the explicit content of literature. This approach helped identify initial codes that served as the basis for generating the main themes. Subsequently, a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the data was conducted, building upon the main themes. This process involved secondary coding to refine the main themes and establish sub-themes. Such reflexive thematic analysis provides a robust structure for the construction of a conceptual framework.

The main themes generated through thematic analysis focus on the following categories: definition of youth; role of youth; levels of participation; methods for youth participation; and participatory theories or conceptual frameworks. These themes were served to answer the following research questions: (1) What is the role of youth in cultural heritage management (through the definition of youth and their roles); (2) How youth can be engaged in the decision-making (through the identification of the levels of participation, the use of participatory methods, and the adoption of participatory theories/frameworks); (3) What dimensions should be considered when integrating youth participation in cultural heritage management (through the construction of a new conceptual framework that encompasses all the main themes summarised above).

3. Results

3.1. Definition of youth

Determined by biological age range, youth are recognised as the transition period between childhood and adulthood, encompassing teenagers and young adults, while the specific age range of youth varies across cultures and is reliant upon socioeconomic and political factors (Feldman-Barrett Citation2018). Youth are associated with a period of personal growth, exploration, identity formation, and increased independence (Golombek Citation2012; Simpson Citation1997). This way of linking biological development and cognitive differences has framed youth as being in the position of ‘becoming’ or ‘developing’ (Best Citation2007; Feldman-Barrett Citation2018). However, critical youth studies have argued that such assumptions based on developmental theories ignore the impact of cultural background on knowledge and individuals’ capacities (Dadich Citation2015; Lesko and Talburt Citation2012). By solely approaching youth as a biologically determined life stage, researchers have limited the understanding and consideration of youth as individuals with their own distinct identities and lived experiences in the present (Bambara, Wilson, and McKenzie Citation2007; Harlan Citation2016). The definition of youth would be constrained if it is approached totally from the adult’s perspective without the acknowledgement of the youth’s own establishment of identity (AbouAssi, Nabatchi, and Antoun Citation2013; Harlan Citation2016). The heterogeneity within the social group of young people is represented by their evolving intellectual and social maturity, and their distinct narratives and capacities at each stage of their development (Bartlett Citation2002; Checkoway Citation2011; Frank Citation2006). It is crucial to understand and respect the rights and capacities of youth in their present being and recognise their roles and responsibilities associated with their stages of life (Sletto and Vasudevan Citation2021).

The establishment of youth’s own identity is strongly affected by cultural, social, and political impacts, which makes it significant to recognise the definition of youth within the research of cultural heritage management (McAra Citation2021; Selim, Mohareb, and Elsamahy Citation2022). It is argued that there is no universal definition of who is considered youth and the concept of youth is a social construct. Rather than defining youth based on biological determinism and developmental theories, the definition of youth is argued to recognise individual youth’s capacities and narratives that are derived from their diverse contextual background and identity (Madgin -David, Webb -Pollyanna, and Tim Citation2016; Selim, Mohareb, and Elsamahy Citation2022; Winn Citation2012). Youth have the rights and responsibilities to identify and establish their interpretations of cultural heritage and participate in the decision-making processes with their unique discourse (Mwangonde, Ntinda, and Hasheela-Mufeti Citation2021; Radulović et al. Citation2022). Therefore, the definition of youth has been broadened to encompass a wider range of perspectives, aiming to reflect the complexity and heterogeneity of young individuals, including their rights, self-identity, ethnic background, historical context, socioeconomic status, and varying capacities (Irazábal and Huerta Citation2016; Oevermann et al. Citation2016).

3.2. The changing roles of youth in decision-making

The concept that ‘youth as agents of environmental changes’ has been wildly accepted, which put an emphasis on the capabilities and rights of youth in civic and social activities (Head Citation2011; Kudva and Driskell Citation2009). In contrast to ‘youth as problems’, Shier (Citation2001) views young people as competent citizens with responsibilities to serve their communities. In this way, youth can ensure that their needs are included, and they make a difference as active participants in existing decision-making processes (Osborne et al. Citation2017). It is also crucial for youth to view themselves as agents of change, regarding adults as their allies in the participation process.

Being acknowledged as agents of change has stimulated young people to actively take on other roles in communities, including learners/researchers, peer educators, and/or leaders (Chawla Citation2002; Percy-Smith and Burns Citation2013). Acting as co-researchers and co-learners in communities can be more effective for youth to cultivate civic capacity and build connections to their communities than being passively educated within the curriculum (Jane Strachan Citation2018). Through independent research and inquiry processes, young people are encouraged to build up their knowledge systems and develop their role as peer educators (Golombek Citation2012; Shier Citation2001). Compared to the one-way learning process at school, the peer-to-peer learning process can encourage young people to take on responsibilities as leaders (B. N. Checkoway and Gutiérrez Citation2012). Through the development of leadership, youth are motivated to generate their initiatives and discourses in decision-making.

Youth are also regarded as ‘agents of cultural heritage’ (Del Baldo and Demartini Citation2021), bearing the responsibilities of safeguarding and transmitting heritage values to future generations (Janković and Mihelić Citation2018). However, only part of the young people who have previously established interests in heritage studies actively take on the role and responsibilities (Mastura, Md Noor, and Mostafa Rasoolimanesh Citation2015b). Therefore, scholars have explored fostering a sense of role consciousness among youth as ‘heritage guardians’ by employing heritage education and role theory, aiming to establish youth motivations to learn and protect local heritage values (McAra Citation2021; Wang et al. Citation2017). While such an approach has contributed to the awareness-raising of youth, the engagement of youth is still limited to informing or educating youth about the predominated heritage discourse (Wang et al. Citation2017). It failed to recognise the active role that youth can play in identifying heritage values and defining the discourse of cultural heritage (Fairweather Citation2006; Hodge, Marsiglia, and Nieri Citation2011; Winter Citation2013). Thus, recognising and incorporating youth narratives into the decision-making process has been advocated as a more effective means of stimulating responsible behaviour and fostering the commitment of youth to assume their roles in the management processes of cultural heritage (Menkshi et al. Citation2021).

Meanwhile, the roles of youth are contingent upon socioeconomic and political contexts. Confronted with various challenges, such as poverty, limited access to education and healthcare, and high unemployment rates, youth from the Global South are more actively taking on the role as agents of change at the forefront of social movements, advocating for inclusive policies to address their unique needs (Chirikure et al. Citation2010; Selim, Mohareb, and Elsamahy Citation2022). However, in the discourse of cultural heritage management, their indigenous and local knowledge is still underrepresented (Fairweather Citation2006; Hodge, Marsiglia, and Nieri Citation2011). Bearing the pressure of social inequalities and the influences of colonialism, these young people reinterpret cultural heritage as valuable resources on which they can draw in their interactions with the de-localised world (Simakole, Angela Farrelly, and Holland Citation2019). Therefore, the changing roles of youth in cultural heritage management are much associated with the heterogeneity of young individuals and are shaped by their socio-cultural backgrounds (Chirikure and Pwiti Citation2008; Chirikure et al. Citation2010).

3.3. Theoretical approaches: integrating youth participation in decision-making

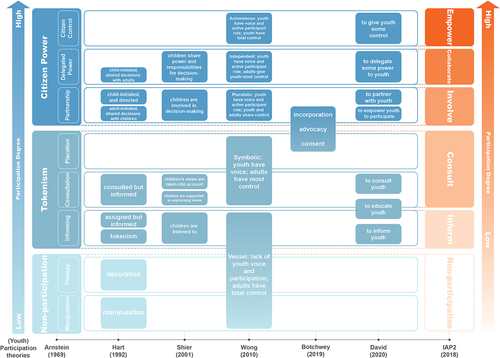

As one of the ground-breaking theories of youth participation, Hart’s Citation1992 ‘Ladder of Participation’ builds on Arnstein’s citizen participation theory (Arnstein Citation1969) with implications of youth’s characteristics and delineates the stepwise progression of participation based on youth and adult partnership (). Following that, successive scholars have generated their iterations with different emphasis on the effects of youth participation (Shier Citation2001), levels of youth empowerment (Wong, Zimmerman, and Parker Citation2010), youth-adult relationships (Botchwey et al. Citation2019), and youth prioritisation and institutionalisation (David Nina and Buchanan Citation2020).

These theories have provided valuable discussions and descriptions of various forms and degrees of youth participation, yet these linear frameworks tend to underestimate the complexities of youth participation and overlook the power dynamics within participatory practices (Collins and Ison Citation2006; Vromen and Collin Citation2010). Hence, through comparing and synthesising these theories, we applied more emphasis and research focus on the youth-adult partnership and youth empowerment in decision-making.

3.3.1. Youth-adult partnership in decision-making

While ‘non-participation’ has been positioned in Hart’s ladder, it is not considered a form of youth participation since youth are only included for symbolic purposes (Bridgman Citation2004; Head Citation2011). Most of the frameworks initiate their participation models by positioning ‘informing’ to the lowest level. This level indicates that youth are informed, while their voices are not adequately heard (R. Hart Citation1992). Starting from this level up, youth are assigned a role within participation with assistance from adults (Wong, Zimmerman, and Parker Citation2010). Although it is considered a participatory step, the conversation between youth and adults is still one-way and youth don’t have opportunities to generate their own initiatives (Derr et al. Citation2013). Consultation is considered an essential level in most participation models since it is the starting point after which youth can have some level of power and control in decision-making (Simpson Citation1997). Youth not only are listened to, but also, they are supported to express their views interactively and their opinions are taken into consideration (London, Zimmerman, and Erbstein Citation2003).

Youth-adult partnerships can progressively evolve through reaching higher levels of participation as youth gradually take on more responsibilities when adults start to lend citizen power to them (Botchwey et al. Citation2019; Wong, Zimmerman, and Parker Citation2010). Although youth receive increasing responsibility and power, the partnership patterns are still derived from adult-centric perspectives and further perpetuate the adult position of power (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2018; B. N.; Checkoway and Gutiérrez Citation2012).

3.3.2. Empowerment of youth in decision-making

To fully recognise youth ideas and fulfill their rights and power, youth-led participation is acknowledged as the higher level of participation (Percy-Smith and Burns Citation2013; Simpson Citation1997). However, many researchers have argued that pursuing total youth-initiated participation can place a disproportionate burden on youth since youth don’t have equal access to institutional resources as adults, thus, fail to fully achieve their initiatives in actual practices (Derr et al. Citation2013; Wong, Zimmerman, and Parker Citation2010). It is vital to understand that youth empowerment is gradually established and may exist in various formats depending on different contexts. Youth-initiated participation is efficient only under specific settings with appropriate design (B. N. Checkoway and Gutiérrez Citation2012; Kudva and Driskell Citation2009). Within the three levels of participation proposed by Botchwey et al. (Citation2019), youth voices cannot be authentically involved without assistance from adults. Adults scaffolding opportunities for youth to participate is thus argued to be the effective mean of youth-adult partnership and a way of youth empowerment (Botchwey et al. Citation2019; Cahill and Dadvand Citation2018). David Nina and Buchanan, Citation2020) highlight that the barriers to ensuring youth participation in formal planning processes mostly relate to the low capacity of youth. Therefore, in their youth participation models, educational training is emphasised as a key step to facilitate participation (Natalie et al. Citation2022). The capacity-building provides youth with access and opportunities to actual decision-making, and also it promotes intergenerational understandings which ultimately legitimates youth participation in policymaking (Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2023; Thomas, Cortina, and Smith Citation2014).

3.4. Level of youth participation

These theoretical approaches have provided a nuanced description of various forms of youth participation and the relationship between youth and adults. However, arguments regarding the linear and rigid frameworks have highlighted several limitations within those generalised theories (Botchwey et al. Citation2019; Farthing Citation2012). Firstly, the youth-adult partnership has framed youth participation totally from an adult’s perspective (R. A. Derr et al. Citation2013; Hart Citation2008), disregarding the importance of incorporating youth’s discourse on their own initiatives within the dynamics of power relationships (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2018). At the same time, the extensive emphasis on adults’ role in youth participation has overlooked the impacts that youth peers can provide during their learning and collaborations (Botchwey et al. Citation2019; London, Zimmerman, and Erbstein Citation2003). It is argued that youth groups with varying ages and abilities tend to generate more potential for capacity-building and creative initiatives (R. A. Derr and Tarantini Citation2016; Hart Citation2008). Secondly, these youth participation theories are associated largely with Western orientation to childhood and youth development, resulting in the tendency to normalise and generalise youth participation in actual practices (Dadich Citation2015; Vromen and Collin Citation2010). It is vital to recognise the historical, cultural, and social-political context of youth development with diverse contextualised approaches (Best Citation2007; Lesko and Talburt Citation2012; Percy-Smith and Burns Citation2013).

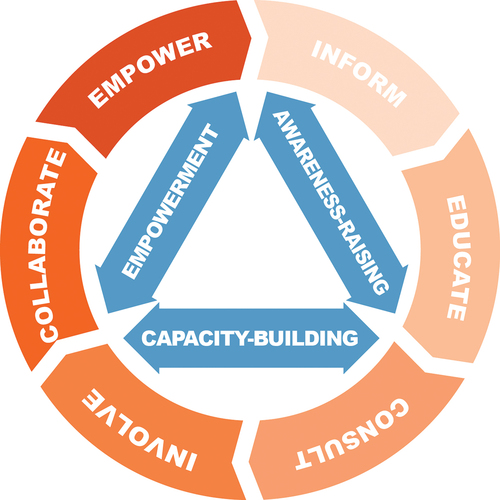

Therefore, to include more flexible and dynamic forms of decision-making in youth participation, the International Association for Public Participation framework (IAP2) has been identified and analysed (IAP2 Citation2018). The IAP2 framework has been adapted and implemented across disciplines of participatory studies, especially demonstrating its effectiveness in facilitating community participation in cultural heritage management (Leiuen Cherrie and Arthure Citation2016; Li et al. Citation2020; Rosetti et al. Citation2022). It is conceptualised as a five-level sequence and each level is built on the previous one: i. Informing; ii. Consulting; iii. Involving; iv. Collaborating and v. Empowering citizens (IAP2 Citation2018; De Leiuen and Arthure Citation2016). While most adaptations of the IAP2 framework retain its sequential configuration, the levels of participation can be implemented as an ongoing recursive process, continuously rotating as new challenges arise or when new youth groups and stakeholders are recruited into the participation processes (De Leiuen and Arthure Citation2016; Waterton and Smith Citation2010). With the acknowledgement of youth discourse and the integration of youth participation theories, a new adaptation of the IAP2 framework with a specific focus on youth has been developed. (.) The adapted framework provides two-fold contributions. First, it consists of six levels, with one new level of ‘educate’ added between ‘inform’ and ‘consult’, which emphasises the role of heritage education in fostering youth engagement. Secondly, explicit descriptions of each participation level were adapted to articulate power dynamics in different forms of youth participation.

Table 1. Conceptualization of youth participation in reviewed literatures.

3.4.1. Adapting the IAP2 participation framework

While as a mainstream participation framework in heritage management, the IAP2 framework also received several critical reflections. Firstly, some scholars argue that the exercise of tokenism and the simplification of complex participation processes have resulted in a lack of public trust (Brown and Yeong Wei Chin Citation2013; Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi Citation2021). The potential for power imbalances and manipulated participation suggests the fundamental weakness of the IAP2 spectrum, which is the haziness over decision-making (Carson Citation2008; Ianniello et al. Citation2019). Such haziness might be further exaggerated through the power dynamics between youth and the decision-making authorities or a limited representation of diverse youth voices (Thomas, Cortina, and Smith Citation2014; Vromen and Collin Citation2010), especially within the established and dominated heritage management discourse (Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2023). To attain accountability and mutual trust between youth and other decision-makers, it is critical to identify and adapt the specific goal and promise at each level of participation (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi Citation2021; Trivelli and Morel Citation2021), so that youth participation can be effectively integrated into decision-making rather than as a symbolic process.

Another argument regarding IAP2 is associated with the difference between the levels of ‘inform’ and ‘consult’ (Carson Citation2008; Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi Citation2021; Ianniello et al. Citation2019). Based on Arnstein’s ladder, the level of inform is kept in the participation spectrum to recognise the necessity of reaching out to broader participants in different settings of the participation (Derr, Chawla, and Mintzer Citation2018; R.; Hart Citation1992). Though, there exist arguments that whether ‘inform’ can be considered public participation for its limited impact on decision-making processes (Kaifeng and Pandey Citation2011). While consultation has promoted opinions exchanges between different stakeholders, the risks of disproportional engagement and prioritisation of the expert’s knowledge might also lead to the distrust of the communities (Bečević and Dahlstedt Citation2022; Ianniello et al. Citation2019). Particularly, youth’s capacities in cultural heritage management have not been fully recognised and integrated with professional knowledge (Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2023), then the level of ‘consult’ might not have adequate influences in decision-making, resulting in the lack of clarity between ‘inform’ and ‘consult’ (Brown and Yeong Wei Chin Citation2013). Therefore, it is argued that there should be a thicker line between the first two levels of participation in the IAP2 spectrum (Carson Citation2008; Kaifeng and Pandey Citation2011). Given the limited recognition of young people’s abilities in decision-making, and the diverse contexts and cultural sensitivity associated with cultural heritage (Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2023), a new level has been adopted in youth participation. The new level of ‘educate’ promotes youth participation from one-way communication to knowledge-sharing and opinions exchanges and provides forceful support for youth to generate influential perspectives during consultation.

Another adaptation of IAP2 focuses on the heterogeneity of young individuals and recognises youth participation as an iterative process. The engagement of a group of youth might reach different levels of participation, and such dissimilarity of participation levels might further stimulate the collaborations within the youth groups (Jennings et al. Citation2012; Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2023). The youth with professional backgrounds in heritage management or equipped with heritage knowledge through practices are referred to as young professionals (Del Baldo and Demartini Citation2021). They attempt to build up youth leadership through their active participation and act as leaders through peer-to-peer collaborations with other young people (Redweik et al. Citation2017). Meanwhile, youth can develop their active role as leaders and advocate participation to less motivated young people through youth campaigns or organisations (Mastura, Md Noor, and Mostafa Rasoolimanesh Citation2015a).

Given the fact that cultural heritage management is a context-specific process where expert knowledge has played an important part in the decision-making (Ginzarly, Farah, and Teller Citation2019; Hodges and Watson Citation2000), the highest level of ‘empower’ is a rarely achieved stage for youth participation (Mastura, Md Noor, and Mostafa Rasoolimanesh Citation2015b). Therefore, the adapted level of empowerment focuses on the recognition and prioritisation of youth initiatives in decision-making processes (Kudva and Driskell Citation2009; Trivelli and Morel Citation2021). Youth are encouraged to form their networks and generate their grassroots organisations alongside existing management systems to increase transparency and accountability of their participation (Botchwey et al. Citation2019; MacDonald et al. Citation2015).

3.4.2. Adding ‘educate’ as one level of youth participation

Heritage education was given a priority role in the knowledge-sharing and capacity-building of youth, as well as fostering intergenerational understanding within cultural heritage discourse (UNESCO Citation2002, Citation2017). The UNESCO Strategy on Youth (2014–2021) also aims to promote heritage education among youth to establish a cultural mechanism for perennial sharing and a long-term commitment of youth to cultural heritage (UNESCO Citation2014). Adding ‘Educate’ as one level of youth participation can recognise the vital role of heritage education in promoting the inclusivity and equity of youth participation, specifically regarding the disparities in the access to information and knowledge gaps that exist among different youth groups (Mkwananzi, Cin, and Marovah Citation2023; Trivelli and Morel Citation2021). At the same time, the level of ‘Educate’ further strengthens the legitimacy and credibility of youth participation in decision-making processes, by providing the platform for establishing common ground and fostering mutual trust among youth themselves or between different generations (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi Citation2021).

Another justification for ‘Educate’ to be recognised as a participation level is based on the various forms of educational communication (Schuster and Jacqui Citation2021; Shaw and Krug Citation2013). Formal heritage education normally happens within schools or institutions as a part of the curriculum (Selim, Mohareb, and Elsamahy Citation2022). Informal education has been observed to be carried out more frequently without the constraints of physical settings and the rigid format of top-down structure (Haddad Citation2014; Del; Baldo and Demartini Citation2021). Education is no longer a one-way communication through which youth only act as receivers and learners within the curriculum (Luo Citation2021; Pazarli, Diamantis, and Gerontopoulou Citation2022). Instead, peer-to-peer education provides youth with more opportunities to critically learn from peers and develop their initial activities (Janković and Mihelić Citation2018).

3.5. Methods of youth participation

Various participatory methods have been implemented and tested with youth, such as public workshops, surveys, meetings, and cultural campaigns (Deitz et al. Citation2018; Haddad Citation2014; Hanssen Citation2019). Those methods have been designed and customised to better fit youth characteristics and to stimulate their motivations, especially with the application of digital technologies (Poplin, de Andrade, and de Sena Citation2022). Based on the purposes of heritage practices and their intended levels of engagement, the participatory methods have been categorised into three pathways: awareness-raising, capacity-building, and empowerment (). These three pathways are not mutually exclusive, they can be combined to foster meaningful engagement in an iterative process of youth participation.

3.5.1. Awareness-raising and capacity-building

Awareness-raising and capacity-building are the basic paths that have been incorporated within educational systems to stimulate youth engagement to evolve beyond one-off interaction to long-term practices (Selim, Mohareb, and Elsamahy Citation2022). Diverse creative approaches, such as drawing, photovoice, digital storytelling, and emotion mapping have been tested to be beneficial (Janković and Mihelić Citation2018). Young people are observed to have a distinct relationship with digital technologies (Ishar, Zatanova, and Roberts Citation2022), and the application of digital serious games is helpful to foster youth capacities of critical thinking and self-learning (de Andrade, Poplin, and de Sena Citation2020). Furthermore, evidence from growing practices has demonstrated the effectiveness of directly involving youth in the documentation of heritage assets or mapping of cultural heritage values during the management processes (Inzerillo and Santagati Citation2016). This approach not only provides opportunities for them to build up capacities along with heritage experts but also stimulates young people to establish intergenerational partnerships (Nofal et al. Citation2020; Redweik et al. Citation2017).

3.5.2. Empowerment through institutionalization

Youth councils or youth parliaments are common methods to empower youth, however, with limited structural support, these approaches might serve as informing or educating platforms rather than empowering youth (Bečević and Dahlstedt Citation2022; Ianniello et al. Citation2019). Thus, it is vital to articulate youth with management authorities to ensure their empowerment in decision-making has real influences (Trivelli and Morel Citation2021). B. N. Checkoway and Gutiérrez (Citation2012) have argued that institutionalisation can promote youth engagement to have a mechanism that is ‘inside the system’, and thus improve youth empowerment (David Nina and Buchanan Citation2020; Horelli Citation1997).

However, there raised concerns about the potential presence of adult bias within the empowerment of youth, whereby adult perspectives influence the selection of good-performance youth as the majority of empowerment (Jennings et al. Citation2012). Such a tendency has been argued to be embedded in the top-down structure and results in the further exclusion of marginalised youth (Bečević and Dahlstedt Citation2022; Ianniello et al. Citation2019). Therefore, it is essential to provide a ‘voice’ for young people from non-legal rationales and through bottom-up initiatives (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi Citation2021; Trivelli and Morel Citation2021).

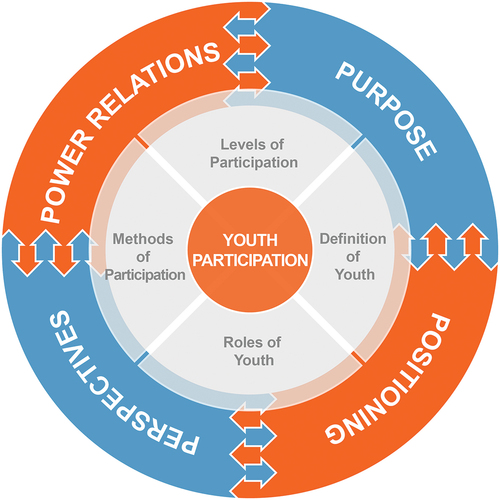

4. New conceptual framework: youth participation in cultural heritage management

In previous sections, youth participation in cultural heritage management was explicitly conceptualised, identifying the definition and role of youth, levels of youth participation, and participatory methods to engage youth. However, most of the existing youth participation models tend to presume that participation is inherently good and that providing a voice or agency to youth will directly lead to the empowerment of youth (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2018). Thus, they do not account for the potential unintended negative consequences of participatory practices (Botchwey et al. Citation2019; Frank Citation2006). A generalised and linear model might fail to reflect the dynamic nature of participation which is highly influenced by historical, cultural, political, and economic background (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi Citation2021). It is vital to recognise that participation does not always follow a linear process that leads to empowerment, but rather a dynamic and iterative process.

While many scholars have reconstructed the hierarchical structure of youth participation models (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2018; Natalie et al. Citation2022), there is still a lack of a dynamic framework in the field of cultural heritage management. Therefore, we propose a new conceptual framework to approach youth participation from four dimensions: purpose, positioning, perspectives, and power relations (). These four dimensions interact with each other and focus on the fluid nature of participation, with its ongoing responses to young people’s characteristics, diverse contexts, and dynamic power relations.

Figure 4. A new conceptual framework of youth participation in cultural heritage management (by authors).

4.1. Purpose

Thinking about the ‘purpose’ starts with defining youth and their levels of participation with attention to the ethical parameter and social-political orientation of the practices. More emphasis should be put on the process of youth engagement and the integration of youth discourse in decision-making, which is vital to ensure their long-term commitment and ownership of future participatory practices. Given its contested nature, cultural heritage can be subject to diverse interpretations among youth and adults or among individual youth (McAra Citation2021). Instead of focusing solely on the results of negotiation, it is more valuable to direct attention towards how diverse interpretations either align or diverge with one another.

Defining youth in participatory practices involves more than the recognition of their capacities and narratives; it also invites young people to define themselves within the program (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2018). Through self-definition, youth tend to actively assume their role in decision-making and are motivated to co-design the visions and purpose of the practices. Being collectively generated, the purpose can be stronger and more feasible to achieve, creating mutual benefits for communities and youth themselves (Victoria and Kovács Citation2017). Through the acknowledgement of the significance of youth engagement, various opportunities can be generated during the envisioning of purpose, which leads to diverse levels of youth participation during management practices.

4.2. Positioning

The concept of ‘positioning’ reflects how young people are culturally framed and understood in terms of their potential contributions to decision-making. Different cultural narratives and norms can influence how youth are positioned and how they position others (Derr and Tarantini Citation2016). However, positioning youth only based on age groups might result in the cultural segregation of young people, further impairing their motivation to be engaged with cultural heritage (Bečević and Dahlstedt Citation2022). Such limited recognition of youth tends to position them only as dependents, followers, or passive recipients.

We argue that such cultural resistance can be mitigated by including and respecting youth’s own positioning of themselves, through which young people can develop their self-identity and sense of agency (Di Franco et al. Citation2019). The process of self-positioning stimulates youth to define their narratives and assign themselves roles in decision-making processes. Through self-recognition and motivation, young people tend to take on more active roles, such as leaders, advocates, investigators, or co-contributors. Meanwhile, how youth position others, including other youth groups, community members, schools, or institutions can also influence their role consciousness. Encouraging youth to critically position themselves and others not only can promote the inclusion of diverse youth representations in decision-making, but also stimulate the bottom-up initiatives that might arise from peer collaborations or youth-adult partnerships (Trivelli and Morel Citation2021).

4.3. Perspectives

It is vital to recognise the dissimilar perspectives of youth and acknowledge that the inequities within gender, socio-economic background, and political context might still exist within participatory practices. Diverse historical, and cultural traditions, and hierarchies surrounding social class, ethnicity, and ability might also influence the voice of youth and their willingness to participate (Thomas, Cortina, and Smith Citation2014). Not only should it be crucial to involve the diverse youth perspectives in heritage discourse, but also to identify the existence of marginalised voices and inequitable patterns of participation within youth groups. Therefore, thinking about ‘perspectives’ should start with distinguishing the perspectives that are included, excluded, or privileged within youth groups (Trivelli and Morel Citation2021). The inclusion of youth perspectives and voices is also closely associated with their roles in decision-making. For those youth who position themselves as advocates for participatory practices might feel frustrated and demotivated if their voices are less heard in the decision-making (Bečević and Dahlstedt Citation2022). Thus, it is important to devise different methods and participation processes to reach youth perspectives, especially for those who are less representative or marginalised for participation.

4.4. Power relations

The inclusion of diverse perspectives is also embedded in the structure of power relations within heritage practices, as it challenges the prevailing dominance of authorised discourse in the management processes (Waterton and Smith Citation2010). It is vital to recognise that power is relational (Arnstein Citation1969) and power relations can be reflected in the levels and methods of participation. However, empowering youth should not directly impose power and control over youth; instead, it should involve efforts to encourage youth to assert control over power dynamics. More emphasis should be placed on cultivating participatory methods that foster young people’s consciousness of roles and responsibilities embedded in power relations. Only until youth acknowledge the power dynamics within participatory practices and take responsibility for their perspectives, can their participation be meaningful and influential in decision-making. Thus, considering power relations can be approached from two aspects: firstly, how power dynamics are managed to incorporate diverse youth perspectives; and secondly, how engaged youth can comprehend and manage power relations to improve their levels of participation.

4.5. Applying the conceptual framework

In addition to highlighting the interconnectedness of the four dimensions, the conceptual framework also emphasises the relations between these dimensions and critical aspects of youth participation. We argue that each dimension can be perceived through different aspects, and the critical aspects are significantly influenced by considerations from different dimensions. For example, the dimension of positioning can be developed through a critical examination of how youth are defined and their roles in decision-making. Simultaneously, defining youth can be approached by envisioning the purpose and positioning within the participatory processes. In this way, youth participation can be envisioned theoretically through the four dimensions and be approached methodologically through the design of four critical aspects in participatory practices.

Our conceptual framework also aims to stimulate youth’s own narratives on the four interrelated dimensions. The purpose of participatory practices can be co-designed with youth to stimulate their motivations and foster their long-term commitment to heritage management. Instead of being positioned by others, youth’s own positioning of themselves tend to cultivate their self-identity and agency, which further promotes their bottom-up initiatives. Taking on active roles in decision-making incentivises youth to make further efforts to ensure the inclusion of their diverse perspectives, especially those that are typically marginalised and underrepresented. Such efforts require youth to comprehend the power relations embedded in participatory practices and acknowledge their responsibilities in decision-making.

5. Conclusion

This paper has analysed and highlighted the contributions of various youth participation theories from urban planning, urban design, urban governance, and heritage management. The results show that these theories or frameworks have provided valuable discussions and visions to integrate youth participation into management systems and advocated an active role of youth in contributing to their society. However, existing models and frameworks tend to presume the inherent ‘goodness’ of youth participation and lack critical reflections about voice, agency, and empowerment within the imposed hierarchical structure of participation. Especially, there is a lack of discussions on the integration of diverse youth discourse into the dominant authorised discourse in participatory heritage practices. It is argued that the limited definition of youth and underestimation of youth capacities in their current state do not adequately acknowledge young people as agents of change, resulting in a low level of youth participation or tokenism. Moreover, the general youth participation models are mostly derived from the Western understanding of youth, which tends to homogenous young people and fails to recognise the various vulnerabilities and inequities within the youth groups. Furthermore, these models do not sufficiently address the nature of participation which has ongoing interactions with historical, cultural, socio-economic, and political complexities in diverse contexts.

In response to these critical reflections, we proposed a new conceptual framework for youth participation in cultural heritage management, which consists of four dimensions: purpose, positioning, perspectives, and power relations. Moving from a linear structure of participation, we aim to reflect the fluid nature of participation with an emphasis on the iterative processes of participatory practices instead of outcomes. Besides conceptualising youth participation and integrating it into the managerial or institutional systems, this framework also encourages youth to envision their participation through their own perspectives. The four dimensions and four critical aspects in the framework provide theoretical implications and methodological applications, framing youth participation in the context of participatory heritage management.

With a limited number of literature about participatory heritage practices with youth, there might be further considerations that can be incorporated into the framework. More perspectives can be focused on other vulnerabilities and inequities of youth in diverse contexts, such as gentrification, colonialism, or gender inequities. This framework can be refined in the future for contextualisation in different social, cultural, and political settings, to encourage more effective youth participation in local heritage management practices. Furthermore, creative participatory methods, particularly with digital technologies can be explored and extend the knowledge of youth participation theoretically and methodologically.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yingxin Zhang

Yingxin Zhang: Yingxin Zhang is a Ph.D. candidate of Architectural History and Theory at the Department of the Built Environment at Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands. Her research interests include participatory heritage management and public participation in sustainable urban development.

Deniz Ikiz Kaya

Deniz Ikiz Kaya: Deniz Ikiz Kaya is an Assistant Professor of Architectural History &Theory at Eindhoven University of Technology. Received her Ph.D. degree in Architecture from the school of Built Environment at Oxford Brookes University, UK, she has many publications in the field of urban heritage management, historic urban landscape, as well as stakeholder participation in heritage management.

Pieter van Wesemael

Pieter van Wesemael: Pieter van Wesemael is Professor of Urbanism and Urban Architecture (UUA) at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e). He is responsible for the Living Cities research program, which focuses on correlations between architecture and urbanism as well as on the evolutionary development of cities and regions bridging place-making, urban studies and cultural history.

Bernard J. Colenbrander

Bernard Colenbrander: Bernard Colenbrander is Professor of Architectural History &Theory at Eindhoven University of Technology since 2005. Previously, he is the chief curator at The Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAI), and project leader of Cultural Planning at the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW).

References

- AbouAssi, K., T. Nabatchi, and R. Antoun. 2013. “Citizen Participation in Public Administration: Views from Lebanon.” International Journal of Public Administration 36 (14): 1029–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.809585.

- Andrade, B. D., Í. A. Poplin, and S. de Sena. 2020. “Minecraft as a Tool for Engaging Children in Urban Planning: A Case Study in Tirol Town, Brazil.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 9 (3): 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9030170.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 35 (4): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Bajec, J. F. 2019. “The Interpretation and Utilization of Cultural Heritage and Its Values by Young People in Slovenia. Is Heritage Really Boring and Uninteresting?” Etnoloska tribina 49 (42): 173–193. https://doi.org/10.15378/1848-9540.2019.42.07.

- Baldo, M. D., and P. Demartini. 2021. “Cultural Heritage Through the “Youth Eyes”: Towards Participatory Governance and Management of UNESCO Sites.” Cultural Initiatives for Sustainable Development 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65687-4_14.

- Bambara, L. M., B. A. Wilson, and M. McKenzie. 2007. “Transition and quality of life.” Handbook of Developmental Disabilities 371–389.

- Bandarin, F., and R. van Oers. 2012. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century. UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bartlett, S. 2002. “Building Better Cities with Children and Youth.” Environment and Urbanization 14 (2): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780201400201.

- Bečević, Z., and M. Dahlstedt. 2022. “On the Margins of Citizenship: Youth Participation and Youth Exclusion in Times of Neoliberal Urbanism.” Journal of Youth Studies 25 (3): 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1886261.

- Best, A. L. 2007. Representing Youth: Methodological Issues in Critical Youth Studies. Methodological Issues in Critical Youth Studies. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814739204.001.0001.

- Botchwey, N. D., N. Johnson, L. K. O’Connell, and A. J. Kim. 2019. “Including Youth in the Ladder of Citizen Participation: Adding Rungs of Consent, Advocacy, and Incorporation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 85 (3): 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1616319.

- Bridgman, R. 2004. “Criteria for Best Practices in Building Child-Friendly Cities: Involving Young People in Urban Planning and Design.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 13 (2): 337–346. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44321120.

- Brown, G., and S. Yeong Wei Chin. 2013. “Assessing the Effectiveness of Public Participation in Neighbourhood Planning.” Planning Practice and Research 28 (5): 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.820037.

- Cahill, H., and B. Dadvand. 2018. “Re-Conceptualising Youth Participation: A Framework to Inform Action.” Children and Youth Services Review 95 (December): 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.001.

- Carson, L. 2008. The IAP2 Spectrum: Larry Susskind in Conversation with IAP2 members. International Journal of Public Participation.

- Chawla, L. 2002. ““Insight, Creativity and Thoughts on the Environment”: Integrating Children and Youth into Human Settlement Development.” Environment and Urbanization 14 (2): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780201400202.

- Checkoway, B. 2011. “What is Youth Participation?” Children and Youth Services Review 33 (2): 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.09.017.

- Checkoway, B. N., and L. M. Gutiérrez. 2012. “Youth Participation and Community Change: An Introduction.” In Youth Participation and Community Change. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n01_01.

- Chirikure, S., M. Manyanga, W. Ndoro, and G. Pwiti. 2010. “Unfulfilled Promises? Heritage Management and Community Participation at Some of Africa’s Cultural Heritage Sites.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16 (1–2): 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903441739.

- Chirikure, S., and G. Pwiti. 2008. “Community Involvement in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Management.” Current Anthropology 49 (3): 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1086/588496.

- Collins, K., and R. Ison. 2006. ‘Dare We Jump off Arnstein’s Ladder? Social Learning as a New Policy Paradigm.’ In Proceedings of PATH (Participatory Approaches in Science & Technology) Conference. www.macaulay.ac.uk/PATHconference/index.html#output.

- Cushing, D. F. 2015. “Promoting Youth Participation in Communities Through Youth Master Planning.” Community Development 46 (1): 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2014.975139.

- Dadich, A. 2015. “Beyond the Romance of Participatory Youth Research.” In A Critical Youth Studies for the 21st Century, 410–425. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004284036_029.

- David Nina, P., and A. Buchanan. 2020. “Planning Our Future: Institutionalizing Youth Participation in Local Government Planning Efforts.” Planning Theory & Practice 21 (1): 9–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1696981.

- Davison, K., and Russell, J. 2017. “Disused Religious Space: Youth Participation in Built Heritage Regeneration.” Religions, 8 (6): 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8060107.

- De, C. C., and R. Dimova. 2019. “Heritage, Gentrification, Participation: Remaking Urban Landscapes in the Name of Culture and Historic Preservation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (9): 863–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1512515.

- Deitz, M., T. Notley, M. Catanzaro, A. Third, and K. Sandbach. 2018. “Emotion Mapping: Using Participatory Media to Support Young People’s Participation in Urban Design.” Emotion, Space and Society 28 (August): 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.05.009.

- De Leiuen, C., and Arthure, S. 2016. “Collaboration on Whose Terms? Using the IAP2 Community Engagement Model for Archaeology in Kapunda, South Australia.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 3 (2): 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1154735.

- Derr, V., L. Chawla, and M. Mintzer. 2018. Placemaking with Children and Youth: Participatory Practices for Planning Sustainable Communities. New York, NY: New Village Press.

- Derr, V., L. Chawla, M. Mintzer, D. Flanders Cushing, and W. Van Vliet. 2013. “A City for All Citizens: Integrating Children and Youth from Marginalized Populations into City Planning.” Buildings 3 (3): 482–505. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings3030482.

- Derr, V., and E. Tarantini. 2016. ““Because We are All People”: Outcomes and Reflections from Young People’s Participation in the Planning and Design of Child-Friendly Public Spaces.” Local Environment 21 (12): 1534–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1145643.

- Evans, B. 2008. “Geographies of Youth/Young People.” Geography Compass 2 (5): 1659–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00147.x.

- Fairweather, I. 2006. “Heritage, Identity and Youth in Postcolonial Namibia.” Journal of Southern African Studies 32:719–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070600995566.

- Farthing, R. 2012. ‘Why Youth Participation? Some Justifications and Critiques of Youth Participation Using New Labour’s Youth Policies as a Case Study’. www.macaulay.ac.uk/PATHconference/index.html#output

- Feldman-Barrett, C. 2018. “Back to the Future: Mapping a Historic Turn in Youth Studies.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (6): 733–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1420150.

- Franco Paola, D., G. Di, M. Winterbottom, and F. Galeazzi. 2019. “Ksar Said: Building Tunisian Young People’s Critical Engagement with Their Heritage.” Sustainability 11 (5): 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051373.

- Frank, K. I. 2006. “The Potential of Youth Participation in Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 20 (4): 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412205286016.

- Gentry, K., and L. Smith. 2019. “Critical Heritage Studies and the Legacies of the Late-Twentieth Century Heritage Canon.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11): 1148–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1570964.

- Ginzarly, M., J. Farah, and J. Teller. 2019. “Claiming a Role for Controversies in the Framing of Local Heritage Values.” Habitat International 88(June). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.05.001.

- Ginzarly, M., C. Houbart, and J. Teller. 2019. “The Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Urban Management: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (10): 999–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1552615.

- Giroux, H. A. 2009. “Introduction: Expendable Futures: Youth and Democracy at Risk.” In Youth in a Suspect Society: Democracy or Disposability?, 1–26. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230100565_1.

- Golombek, S. B. 2012. “Children as Citizens.” In Youth Participation and Community Change, 11–30. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n01_02.

- Grcheva, O., and B. Oktay Vehbi. 2021. “From Public Participation to Co-Creation in the Cultural Heritage Management Decision-Making Process.” Sustainability 13 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169321.

- Guzmán, P. C., A. R. P. Roders, and B. J. F. Colenbrander. 2017. “Measuring Links Between Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Urban Development: An Overview of Global Monitoring Tools.” Cities 60 (February): 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.005.

- Haddad, N. A. 2014. “Heritage Multimedia and Children Edutainment: Assessment and Recommendations.” Advances in Multimedia 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/579182.

- Halu, Z. Y., and A. Gülçin Küçükkaya. 2016. “Public Participation of Young People for Architectural Heritage Conservation.” Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences 225 (July): 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.017.

- Hanssen, G. S. 2019. “The Social Sustainable City: How to Involve Children in Designing and Planning for Urban Childhoods?” Urban Planning 4 (1TheTransformativePowerofUrbanPlanning): 53–66. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i1.1719.

- Harlan, M. A. 2016. “Appears with the Article: Reprinted, with Permission, from School Libraries Worldwide.” School Libraries Worldwide 22 (2): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.29173/slw6917.

- Harrison, R. 2015. “Beyond “Natural” and “Cultural” Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of Anthropocene.” Heritage & Society 8 (1): 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036.

- Harrison, R., and D. Rose. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Hart, R. 1992. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. UNICEF Innocenti Essays No. 4. Florence: UNICEF .

- Hart, R. A. 2008. “Stepping Back from “The Ladder”: Reflections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children.” In Participation and Learning, 19–31. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6416-6_2.

- Head, B. W. 2011. “Why Not Ask Them? Mapping and Promoting Youth Participation.” Children and Youth Services Review 33 (4): 541–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.05.015.

- Heras, V. C., M. Soledad Moscoso Cordero, A. Wijffels, A. Tenze, and D. Esteban Jaramillo Paredes. 2019. “Heritage Values: Towards a Holistic and Participatory Management Approach.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 9 (2): 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-10-2017-0070.

- Hodge, D. R., F. F. Marsiglia, and T. Nieri. 2011. “Religion and Substance Use Among Youths of Mexican Heritage: A Social Capital Perspective.” Social Work Research 35 (3): 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/35.3.137.

- Hodges, A., and S. Watson. 2000. “Community-Based Heritage Management: A Case Study and Agenda for Research.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 6 (3): 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250050148214.

- Horelli, L. 1997. “A Methodological Approach to Children’s Participation in Urban Planning.” Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 14 (3): 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02815739708730428.

- Ianniello, M., S. Iacuzzi, P. Fedele, and L. Brusati. 2019. “Obstacles and Solutions on the Ladder of Citizen Participation: A Systematic Review.” Public Management Review 21 (1): 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1438499.

- IAP2. 2018. ‘International Association of Public Participation’. www.macaulay.ac.uk/PATHconference/index.html#output.

- Inzerillo, L., and C. Santagati. 2016. Crowdsourcing Cultural Heritage: From 3D Modeling to the Engagement of Young Generations. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 10058 LNCS Springer Verlag: 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48496-9_70

- Irazábal, C., and C. Huerta. 2016. “Intersectionality and Planning at the Margins: LGBTQ Youth of Color in New York.” Gender, Place and Culture 23 (5): 714–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2015.1058755.

- Ishar, S. I., S. Zatanova, and J. L. Roberts. 2022. “3D GAMING for YOUNG GENERATIONS in HERITAGE PROTECTION: A REVIEW.” International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives, Vol. 48, 53–60. International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-4-W4-2022-53-2022.

- Jaafar, M., Noor, S. M., and Rasoolimanesh, S. M. 2015. “Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: A case study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site.” Tourism Management 48:154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.018.

- Janković, I., and S. Mihelić. 2018. “Get’em While They’re Young: Advances in Participatory Heritage Education in Croatia.” In SpringerBriefs in Archaeology, 107–117. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68652-3_7.

- Jennings, L. B., D. M. Parra-Medina, D. A. K. H. Messias, and K. McLoughlin. 2012. “Toward a Critical Social Theory of Youth Empowerment.” In Youth Participation and Community Change, 31–56. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n01_03.

- Joffe, H., and L. Yardley. 2003. “Chapter four: content and thematic analysis.” Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology, 56–68. London: Sage Publications.

- Kaifeng, Y., and S. K. Pandey. 2011. “Further Dissecting the Black Box of Citizen Participation: When Does Citizen Involvement Lead to Good Outcomes?” Public Administration Review 71 (6): 880–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02417.x.

- Kudva, N., and D. Driskell. 2009. “Creating Space for Participation: The Role of Organizational Practice in Structuring Youth Participation.” Community Development 40 (4): 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330903279705.

- Landorf, C. 2009. “A Framework for Sustainable Heritage Management: A Study of UK Industrial Heritage Sites.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 15 (6): 494–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903210795.

- Leiuen Cherrie, D., and S. Arthure. 2016. “Collaboration on Whose Terms? Using the IAP2 Community Engagement Model for Archaeology in Kapunda, South Australia.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 3 (2): 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1154735.

- Lesko, N., and S. Talburt. 2012. Keywords in Youth Studies: Tracing Affects, Movements, Knowledges. New York: Routledge.

- Li, J., S. Krishnamurthy, A. Pereira Roders, and P. van Wesemael. 2020. “Community Participation in Cultural Heritage Management: A Systematic Literature Review Comparing Chinese and International Practices.” Cities 96(January). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102476.

- Loes, V., A. R. Pereira Roders, and J. F. C. Bernard. 2013. “Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 4 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1179/1756750513z.00000000022.

- London, J. K., K. Zimmerman, and N. Erbstein. 2003. “Youth-Led Research and Evaluation: Tools for Youth, Organizational, and Community Development.” New Directions for Evaluation 2003 (98): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.83.

- Luo, Y. 2021. “Safeguarding Intangible Heritage Through Edutainment in China’s Creative Urban Environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (2): 170–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1780463.

- MacDonald, J. P., J. Ford, A. Cunsolo Willox, C. Mitchell, K. Productions, M. W. S. A. D. Media Lab, and R. I. Community Government. 2015. “Youth-Led Participatory Video as a Strategy to Enhance Inuit Youth Adaptive Capacities for Dealing with Climate Change.” Arctic 68 (4): 486–499. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4527.

- Madgin -David, R., R. Webb -Pollyanna, and S. Tim. 2016. “Engaging Youth in Cultural Heritage: Time, Place and Communication.” Youth and Heritage. www.macaulay.ac.uk/PATHconference/index.html#output.

- Manal, G., and F. Jordan Srour. 2021. “Unveiling Children’s Perceptions of World Heritage Sites: A Visual and Qualitative Approach.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (12): 1324–1342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1977374.

- Mastura, J., S. Md Noor, and S. Mostafa Rasoolimanesh. 2015a. “The Effects of a Campaign on Awareness and Participation Among Local Youth at the Lenggong Valley World Heritage Site, Malaysia.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 17 (4): 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2016.1175907.

- Mastura, J., S. Md Noor, and S. Mostafa Rasoolimanesh. 2015b. “Perception of Young Local Residents Toward Sustainable Conservation Programmes: A Case Study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site.” Tourism Management 48 (June): 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.018.

- McAra, M. 2021. ““Living in a Postcard”: Creatively Exploring Cultural Heritage with Young People Living in Scottish Island Communities.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (2): 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1795905.

- Menkshi, E., E. Braholli, S. Çobani, and D. Shehu. 2021. “Assessing Youth Engagement in the Preservation and Promotion of Culture Heritage: A Case Study in Korça City, Albania.” Quaestiones Geographicae 40 (1): 109–125. https://doi.org/10.2478/quageo-2021-0009.

- Mkwananzi, F., F. M. Cin, and T. Marovah. 2023. “Transformative Youth Development Through Heritage Projects: Connecting Political, Creative, and Cultural Capabilities.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 29 (6): 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2209058.

- Mwangonde, K., M. Ntinda, and V. Hasheela-Mufeti. 2021. A Game-Based Approach to Revive Cultural Heritage Amongst the Youth; a Game-Based Approach to Revive Cultural Heritage Amongst the Youth. Www.IST-Africa.Org/Conference2021.

- Natalie, H., P. Patterson, P. Orchard, and K. R. Allison. 2022. “Support, Develop, Empower: The Co-Development of a Youth Leadership Framework.” Children and Youth Services Review 137 (June): 106477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106477.

- Nations, U. 1981. ‘General Assembly: Report of the Advisory Committee for the International Youth Year’. www.macaulay.ac.uk/PATHconference/index.html#output.

- Nofal, E., G. Panagiotidou, R. M. Reffat, H. Hameeuw, V. Boschloos, and A. Vande Moere. 1 2020. “Situated Tangible Gamification of Heritage for Supporting Collaborative Learning of Young Museum Visitors.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 13 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3350427.

- Oevermann, H., J. Degenkolb, A. Dießler, S. Karge, and U. Peltz. 2016. “Participation in the Reuse of Industrial Heritage Sites: The Case of Oberschöneweide, Berlin.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (1): 43–58. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1083460.

- Olsson, K. 2008. “Citizen Input in Urban Heritage Management and Planning: A Quantitative Approach to Citizen Participation.” TPR 79 (4): 371–394. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.79.4.3.

- Osborne, C., Baldwin, C., Thomsen, D., and Woolcock, G. 2017. “The unheard voices of youth in urban planning: using social capital as a theoretical lens in Sunshine Coast, Australia.” Children's Geographies 15 (3): 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2016.1249822.

- Pazarli, M., K. Diamantis, and V. Gerontopoulou. 2022. ““Hack the Map”, a Digital Educational Program Inspired by Rigas Velestinlis’ Charta of Greece (1796–1797)”.” International Journal of Cartography 8 (1): 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/23729333.2021.1972908.

- Percy-Smith, B., and D. Burns. 2013. “Exploring the Role of Children and Young People as Agents of Change in Sustainable Community Development.” Local Environment 18 (3): 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.729565.

- Poplin, A., B. de Andrade, and Í. de Sena. 2022. “Let’s Discuss Our City! Engaging Youth in the Co-Creation of Living Environments with Digital Serious Geogames and Gamified Storytelling.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 50 (4), May): 1087–1103. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083221133828.