ABSTRACT

UNESCO’s Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) (Convention) provides the highest level of international recognition for outstanding universal heritage places. While the Convention has been instrumental in aiding heritage preservation, arguably it has also reinforced a problematic ‘culture’ and ‘nature’ division in protected area management. This is not a new observation. One solution that attempted to address this issue was the introduction of the World Heritage (WH) ‘Cultural Landscape’ category in 1992. Yet, as of 2023, there are only 127 Cultural Landscape properties of the total 1157 properties on the WH List (10.9%). Poor recognition of the category appears particularly acute in some regions, such as Australia-Oceania, and in this paper, we consider this apparent under-utilisation with a systematic review of the literature about the category. Our analysis reveals significant and concerning regional variations in both use of the cultural landscape category and in research about it. In our current era, when better recognition of First Nation heritage is demanded, and when greater protection of heritage assets is required, further uptake of the Cultural Landscape category has the potential to redress these pressing societal concerns.

Introduction

Heritage conservation approaches and the idea of ‘cultural landscapes’

The idea of a ‘cultural landscape’ has long been regarded as a tool to bridge the conceptual and practical gap in recognising and protecting ‘nature’ and ‘culture’. Almost 100 years ago Geographer, Carl Sauer (Citation1925, 46), defined cultural landscapes as a place ‘ … fashioned from a natural landscape by a culture group. Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape is the result’. Taylor et al. (Citation2022) criticise the term ‘natural landscape’ as a misnomer as all landscapes are inherently cultural. The cultural landscape idea affirms the interconnections between culture and nature. Taylor and Lennon (Citation2012) note that cultural attachment to landscape help shape identity to place and ascribe to it intangible values, therefore arguably landscapes everywhere are imbued with cultural connotations and are a product of cultural practices (Wylie Citation2007).

Much has been written about ‘cultural landscapes’ as a category for both describing and managing cultural and natural assets, but we do not review this literature here (see for examples, Bridgewater and Bridgewater Citation2004; Dailoo and Pannekoek Citation2008; Head Citation2000). Our aim is to aid our understanding of why the classification has not received greater success. To this end we have documented use of the term in academic literature since 1982 to identify trends and patterns for World Heritage (WH) Cultural Landscapes. We posit that in order to provide better recognition and protection of sites with significant interconnected cultural and natural heritage values, increased use of this category might be overdue or, at the least, its apparent under-use warrants further critical attention.

World heritage convention and cultural landscapes: an overview

The World Heritage Convention (WHC) (Citation1972) is regarded as the most successful international conservation treaty and links nature conservation and the protection of cultural properties (UNESCO Citation2021, s.II.A, 45). WH properties were first designated as either one of two types, ‘cultural’ or ‘natural’ (UNESCO Citation2021, s.II.A, 45). Properties are assessed for potential inclusion on the WH List (WHL) by the WHC’s official Advisory bodies, being (1) the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) for cultural properties, and (2) the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for natural properties. Sites could be nominated for both cultural and natural heritage, but would be assessed by ICOMOS/ICCROM and the IUCN separately (UNESCO Citation1985).

A key issue with a natural heritage listing was the specification that natural sites could not be modified by ‘man’ (sic) (UNESCO Citation1985). Yet, it was noted, following the preparation of the French Tentative List in 1985, that very few natural sites met this criterion due to the role of people shaping the landscape (UNESCO Citation1985). Initially this led to the recognition of ‘Rural Landscapes’, which were described as ‘biocultural mosaics’ and formed as a result of sustainable land production alongside human habitation (Rössler Citation2019). ‘Rural Landscapes’ reflected a more inclusive framework, however there remained concerns. One of which was related to the definition, which was thought to be too narrow, as it acted to exclude remote landscapes, as rural implied an agrarian society (Cameron and Rössler Citation2013).

The firm distinction between cultural and natural sites required revision, and so during the late 1980s, sites with both cultural and natural properties were prioritised for inclusion on the WHL through a new designation as ‘Mixed Sites’ (UNESCO Citation2021, s.II.A, 46). Mixed Sites ‘derive their outstanding universal value from a particularly significant combination of cultural and natural features’ (UNESCO Citation1999a, 18). While this development was significant, again there was dissatisfaction with the ‘Mixed Site’ category, especially as nominations only needed to satisfy the criteria for one of each of the cultural and natural criterion (UNESCO Citation1999a, 18). Thus, the interactions between cultural and natural assets were not necessarily established with the ‘Mixed Site’ category (UNESCO Citation1999a, 18). An inclusive, interconnected understanding of landscape remained absent.

At the same time, pressing demands for greater recognition of non-European Indigenous worldviews in WH management arose (Cameron and Rössler Citation2013). At this stage the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Operational Guidelines (1992a, 14), which is the key guiding documentation for enacting WHC commitments, were incongruent with a First Nations holistic understanding of place-being. As Aboriginal trawlwulwuy scholar Lee (Citation2016) reaffirms, Indigenous Australians for example, view nature and culture as inextricably linked and challenges the dominant dualistic narrative. Such a perspective was not reflected in the operationalisation of the WHC as community involvement was actively discouraged throughout the nomination stage, a practice that reinforced the culture-nature binary (Cameron and Rössler Citation2013; Hill et al. Citation2011).Footnote1

Another key moment in the evolution of the WH classifications came in 1986 when the United Kingdom nominated the English Lake District as a ‘Mixed Site’ (ICOMOS Citation2017).Footnote2 While ICOMOS recommended inscription of the property for cultural values, the WH Committee decided to ‘leave open its decision on this nomination until it had further clarified its position regarding the inscription of cultural landscapes’ (UNESCO Citation1987). The nomination was deferred due to a lack of sufficiently clear criteria at the time (UNESCO Citation1990). The WH Committee required the Secretariat to develop a proposal about ‘Cultural Landscapes’ for the Fifteenth Annual session in 1991 (ICOMOS Citation2017). As a result, ‘Cultural Landscapes’ were introduced as a separate category of the WHC, in October 1992, to better acknowledge sites as ‘the combined works of nature and man (sic)’ (UNESCO Citation1992). This was the first international legal instrument that provided recognition of cultural landscapes, defined as

… illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment, and of successive social, economic and cultural forces, both external and internal.

In 2002, ten years after the creation of the category, there were only thirty official Cultural Landscapes listed but, at that time, there was estimated to be over one hundred potential properties already inscribed that might be re-nominated into this category (Fowler Citation2003). There were expectations that another hundred sites could be further nominated in the forthcoming decade (by 2013) (Fowler Citation2003). By way of example, in the Australian-Oceania region, two sites previously designated as Mixed properties, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (Australia), and Tongariro National Park (Aotearoa/New Zealand), were the first to be re-inscribed as Cultural Landscapes (Hill et al. Citation2011).

In 2023, thirty-one years after the creation of the category, the WHL currently recognises 121 properties and six transboundary properties as Cultural Landscapes (in addition to one de-listed property in Europe, 2009) (UNESCO Citationn.d.). This represents only 10.9% of all WH properties and is substantially less than the predicted number of properties which could be included under the Cultural Landscapes category. Understanding the patterns of an apparent ‘failure’ of the category to flourish is our aim. Commentators have indicated that it could be due to inefficiencies in the process (of nomination and assessment of dossiers), despite the category being, as Fowler (Citation2003, 15) described, an ‘increasingly known mechanism for describing one of the world’s saner ideas … recognising humanity’s near all-pervasive environmental influence’.

Unpacking the role of the category has been the subject of recent research. Brumann and Gfeller (Citation2022), for example, have drawn attention to the inefficiencies of the category. They document a mis-prioritisation at work, including listing of non-Indigenous European heritage sites such as vineyard landscapes over Indigenous heritage landscapes, which the category was explicitly designed to protect. Another key issue they identified is the difficulty in gaining expert approval for Indigenous heritage site inscriptions, due to expert bodies being dominated by European perspectives (Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022). They suggest that these factors have led to continued under-representation of the category for WH properties (Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022). Alongside other scholars, such as Taylor and Altenburg (Citation2006) and Winter (Citation2014), there is an ongoing call for better awareness of the overarching European influence within which the WHC operates. A strong European perspective gives rise to a stark othering of non-European Indigenous heritage values, which is arguably reflected in the location and number of Cultural Landscape inscriptions worldwide. We look to whether scholarship about the category reinforces this spatial bias. While cultural landscapes worldwide warrant further attention (especially in relation to First Nation cultural practices), we consider whether an under-utilisation of the category in one place, the Australian-Oceania region, reflects and reinforces a lack of engagement with Indigenous worldviews.

Australia’s World Heritage Cultural Landscape properties

There are twenty sites inscribed on the WHL in Australia in 2023, with twelve sites inscribed for natural heritage, four inscribed for cultural heritage and four inscribed under both cultural and natural ‘Mixed’ criterion (UNESCO Citation2023). There are only two WH properties in Australia inscribed under the Cultural Landscape category: Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and Budj Bim Cultural Landscape.Footnote3

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (Central Australia) was the second Cultural Landscape inscription globally. It was first inscribed as a Mixed Site in 1987, but was re-listed in 1994 as a Cultural Landscape in light of revised cultural criteria (ICOMOS Citation1994; UNESCO Citation1994; IUCN Citation1987). The WH inscription recognises the site for its outstanding geological formations, which represent part of the Anangu Aboriginal cultural belief system (ICOMOS Citation1994). Despite effective joint management, there were no additional cultural landscape inscriptions in Australia for a quarter century. Accordingly, twenty-five years later, Budj Bim Cultural Landscape (South-Eastern Australia) was inscribed on the WHL in 2019 (UNESCO Citation2019). Budj Bim is one of the oldest and most extensive aquaculture systems in the world, which were modified by the Gunditjmara people and formed the core economy and society for over 6,600 years. It is inscribed on the WHL for the cultural traditions and knowledge practices, and the Cultural Landscape is a representative example of people interacting with the environment (UNESCO Citation2019).

Cultural Landscapes have been a distinct WH category for the past thirty-one years, yet the initial expectation that the category would flourish has not been met. Cultural Landscape properties are largely located in Europe, creating a spatial bias in the category. The bias persists despite countries such as Australia arguably containing a significant number of sites which are well suited to the classification given Australia is home to the oldest living culture in the world (Poroch Citation2014).

Methods

We provide an empirical review of the WH ‘Cultural Landscape’ category within English-written academic literature to shed light on the apparent underutilisation of the category, especially in an Australian-Oceania setting. We use the publication of research about WH Cultural Landscapes as a proxy for awareness about the category and to provide critical insights into its use. Literature searches were conducted using the databases, Web of Science, Scopus, and Informit, published between 1982 and 2022 to ascertain if temporal trends could be discerned.

The literature from each database was retrieved during February and March 2023 using the following combined search query: ‘world AND heritage’, ‘cultural AND landscape*’ and Geographical Region such as ‘Australia* OR Pacific OR Oceania’ or ‘North OR South AND America*’. Each search was repeated for global areas of interest being classified regionally into Australia-Oceania, Africa, Asia, America (North and South) and Europe to identify the spatial distribution of research broadly relating to the ‘Cultural Landscape’ categorisation. These searches yielded a total of 494 results ().

Table 1. Preliminary database results by geographical region (Web of Science, Scopus, Informit).

As part of the initial scoping exercise, unrelated subject areas and categories were excluded to remove unnecessary noise from the search. The Web of Science categories were filtered to include the disciplines of ‘environmental studies, geography, environmental sciences, humanities multidisciplinary, geosciences multidisciplinary, multidisciplinary studies and social sciences multidisciplinary’. The Scopus searches were limited to broad disciplinary categories of ‘social sciences, environmental sciences, arts and humanities’. Searches using Scopus were also filtered using the following keywords: ‘cultural heritage, cultural landscape, World Heritage Site, World Heritage, UNESCO and environmental protection’. No additional filters were applied to the Informit databases. Results included journal articles, book chapters and media reports.

Search results were manually filtered for relevance, to include research investigating the integration of WH cultural and natural properties, values, or classifications, and mention of ‘Cultural Landscapes’ for the WHL.Footnote4 The narrowed search resulted in a final publication collection of 172 papers (). This smaller body of literature reflects that while cultural landscapes are a widely utilised concept across multiple disciplines, its application to WH represents only a small subsection of its overall use.Footnote5 By way of example, the search term ‘Cultural AND Landscape*’ yields 10,292 results on Web of Science alone.

Table 2. Refined database results by geographical region (Web of Science, Scopus, Informit).

Results

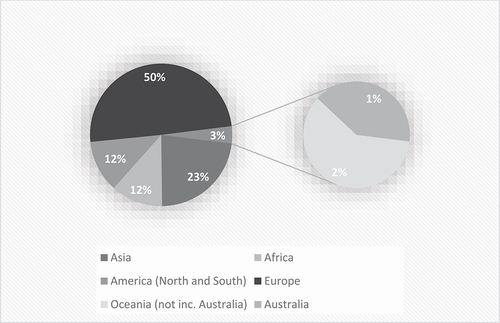

Search results yielded both spatial and temporal patterns from our dataset of 172 research papers. We firstly consider the spatial question of ‘where’ research about cultural landscapes is taking place. The results from the literature review, suggests in order of descent, that Europe has the most publications, followed by Australia-Oceania, Asia, Africa, North America and South America ().

Figure 1. Use of cultural landscapes as a World Heritage category in the literature, organised by continent. Listed, and mapped by Author 1. Continent basemap open-source: Esri.

A temporal pattern was also revealed. The decadal results illustrate limited discussion prior to 1992 (pre-formalisation of the category), which was expected (). An increase in literature following this period coincides with the growth of scholarly attention in the field of heritage studies (Gentry and Smith Citation2019). The International Journal of Heritage Studies was established in 1994 and followed by the development of the Critical Heritage Studies in the early 2000s (Gentry and Smith Citation2019). Publications occur across all regional locations in a relatively uniform manner between 2002–2011 (). The 2012–2021 time-frame shows a slight increase in African-based literature, a small decline in Asian-based literature with a greater increase in Australian- and American-based literature ().

Figure 2. Use of ‘cultural landscapes’ and ‘world heritage’ by geographical region and decade (2023). Graphed by Author 1.

The most significant increase is amongst the European literature, which reflects the region of the most inscribed Cultural Landscapes (). What is clear is that while Australia only contains two WH Cultural Landscapes, there is a disproportionately large amount of scholarly interest from this region.

Figure 3. Distribution of World Heritage Listed Cultural Landscape properties (121) and transboundary Cultural Landscapes (6) by continent, including Australia (2023). Transboundary properties were graphed using the predominant country location of the site. Graphed by Author 1.

As mentioned previously, existing WH properties within the Australia-Oceania region were the first to utilise the Cultural Landscape category through the re-inscription process in 1993 of Tongariro National Park and in 1994 with Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park respectively (UNESCO, Citationn.d..).Footnote6 Again, despite a relatively fast adoption this momentum did not gain the expected traction both in Australia and other continents (excluding Europe) (; Fowler Citation2003).

Many of the papers analysed underscore the arguments about an underutilisation of the Cultural Landscapes category. Research from Africa (Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022; Cocks, Vetter, and Wiersum Citation2018; Saintenoy et al. Citation2019), Asia (Akagawa and Sirisrisak Citation2008; Rössler and Lin Citation2018, Silva et al. Citation2022; Taylor Citation2009; Taylor and Lennon Citation2011), America (Carmody Citation2016; Losson Citation2017; Perez and Salinas Citation2015), and Australia (Carter Citation2010; Cullen-Unsworth et al. Citation2012; Hill et al. Citation2011; Lee and Richardson Citation2017) all reinforce this point. In reviewing this literature, three core themes regarding underutilisation emerged being (1) the definition of heritage within the WHC and heritage management field, (2) the need for increased recognition of First Nations cultural heritage and (3) the re-nomination of existing sites inscribed under natural or mixed heritage values.

The first issue concerned concerns about how heritage is defined. From the development of the WHC, heritage has been separated as having cultural and natural value and was viewed as incompatible to protect together (Aplin Citation2007; Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022). This perception has remained within wider heritage management practices, even with a more inclusive framework which recognised Cultural Landscapes and ‘Mixed’ properties. Therefore, scholars have argued for a more holistic and integrated approach to management of cultural and natural heritage (see for examples, Koch and Gillespie Citation2022; Marshall et al. Citation2022; Menzies and Wilson Citation2020).

The second issue called for stronger recognition of Indigenous cultural heritage and co-management practices through WH inscription. This perspective was dominant in over half (twenty-five) of the Australia-Oceania focused papers (see for examples, Carter Citation2010; Hill et al. Citation2011; Lee and Richardson Citation2017; Russell and Jambrecina Citation2002). Whilst a lack of representation and Indigenous engagement was noted in ten of the Australian publications (see for examples, Connolly Citation2007; Lee and Richardson Citation2017; Skilton, Adams, and Gibbs Citation2014; Smith et al. Citation2019).

The third notable trend related to a growing emphasis on the need to renominate existing WH properties, especially in an Australian context. Importantly, within this scholarship, twelve of the thirty-three Australian papers advocated for renomination of sites as Cultural Landscapes. Such calls for renomination also align with the aim to broaden an understanding of heritage as interconnecting both cultural and natural components.Footnote7

Discussion

Cultural landscapes: expanding the definition of heritage

The aim of the Cultural Landscape category was to expand the view of heritage to be more representative of its diversity (UNESCO, Citationn.d..). However, the literature is divided in whether this has occurred through the WH categorisation. For example, Skilton et al. (Citation2014) states that the Cultural Landscape category subverts the culture-nature binary that was prevalent within the WHC and Gfeller (Citation2013) indicates the new category successfully bridged the divide. In contrast, Buckley (Citation2022) affirms that the culture-nature divide is still prevalent, particularly as Cultural Landscapes are inscribed under the cultural category which they argue has exacerbated the imbalance. Further, Reeves and McConville (Citation2011) suggested that a baseline understanding of ‘Cultural Landscapes’ through the WH category has had limited success.

In terms of support for the category, Australia and New Zealand, in particular, were strong advocates for the Cultural Landscape category which in part, led to its early success (Wallace and Buckley Citation2015). However, uptake and endorsement of the classification has faltered. A UNESCO (Citation1999b), expert meeting noted there were multiple definitions of landscape and cultural landscape operating simultaneously. Specific interpretations of ‘cultural landscape’ were dependent on regional and national contexts and thus far an overarching universal definition has not emerged. To accommodate this, Reeves and Long (Citation2011) suggested the term cultural landscape should be both flexible and technical. Today, heritage remains defined by the WHC as either ‘cultural’ (monuments, groups of buildings and sites) or ‘natural’ (natural features and sites, and geological and physiographical formations) and each category is clearly delineated (UNESCO Citation2021, s.II.A, 45). Despite expanding the categories to include cultural landscapes, the WHC still operates with siloed definitions which further perpetuates the distinction between culture and nature (Carter Citation2010; Lee and Richardson Citation2017). Carter (Citation2010) highlights the current approach to heritage management has created a ‘separationist paradigm’. A similar view is echoed in Lee and Richardson (Citation2017), who argues that the protected area systems delineate a clearly defined geographical space which prevents a landscape scale approach to conservation, inclusive of culture and nature.

Of note is that the Cultural Landscape category (alongside ICOMOS Australia (Citation2013) and UNESCO (Citation2003)), has expanded the values of nominated places for WH status to include associative and intangible heritage (Head Citation2000; McBryde Citation2014). This is regarded as a significant shift away from monumental heritage, with its material and archaeological focus. In the context of the Australia-Oceania dataset twenty-five papers linked cultural heritage to non-Indigenous archaeological endeavours favouring assessments in terms of the material landscape (tangible heritage) (see for examples, Cullen-Unsworth et al. Citation2012; Draper Citation2015; Wallace and Buckley Citation2015). This focus on tangible heritage is perpetuated through dominant non-Indigenous European scientific assessment models, and this phenomenon was identified by multiple authors as prevalent (Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022; Draper Citation2015; Taylor and Altenburg Citation2006; Winter Citation2014). However, best practice conservation strategies suggest there should be equal consideration of both tangible and intangible heritage (Connolly Citation2007; Marshall et al. Citation2022; Wallace and Buckley Citation2015). The WH nomination dossiers for Australian sites including Kakadu National Park, Tasmanian Wilderness, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and Willandra Lakes emphasised scientific perspectives and notably these properties were not originally nominated or recognised for cultural continuity (ICOMOS Citation1981, Citation1989, Citation1991, Citation1994; McBryde Citation2014).

Many scholars identified that the current protected area management system (including WH), has an insular approach to protection as it requires a clear distinction of spatial and temporal boundaries (Connolly Citation2007; Lee and Richardson Citation2017; Reeves and Long Citation2011; Russell and Jambrecina Citation2002). This limitation restricts heritage to a single defined place, making it difficult to incorporate the ‘Cultural Landscape’ concept (Connolly Citation2007) as cultural landscapes move beyond the protection of monuments and buildings alone (Blair and James Citation2016; McBryde Citation1997; Reeves and Long Citation2011). There lies a significant challenge where sites meet the definition of a ‘Cultural Landscape’, such as trade routes or song-lines, but there are no clearly defined boundaries for known routes or archaeological assemblages, which can be used to quantify significant associational, spiritual, cultural or ceremonial values (McBryde Citation1997, Citation2014; Russell and Jambrecina Citation2002). Again, many researchers have called for the adoption of a holistic landscape approach to avoid the rigid specificity of particular site-based assessments (Blair and James Citation2016; Buckley Citation2022; Carter Citation2010; Koch and Gillespie Citation2022; Marshall et al. Citation2022). Shifting the perspective of heritage classifications towards better use of cultural landscapes may enable better use of WH buffer zones to, for example, protect vulnerable ecological communities, and/or to give better recognition of local community attachment to place (Gillespie Citation2012; Russell and Jambrecina Citation2002; Trau, Ballard, and Wilson Citation2014). Ultimately, scholars argue that the Cultural Landscape category has the potential to enable better conservation outcomes (Russell and Jambrecina Citation2002). Similar terms have been coined to describe the interactions between people and the environment, including biocultural landscape and eco-cultural landscape (Bridgewater, Rotherham, and Rozzi Citation2019). Therefore, a shift to more inclusive terminology could add clarity and allow for more widespread use. To achieve this, arguably cultural landscapes require a more consistent and universal definition.

Lack of recognition of first nation cultural landscapes

One of the dominant themes from our review was a lack of recognition of First Nations heritage in the WHL. Researchers clearly present the case that a Cultural Landscape protected area classification is a suitable way to provide for greater First Nation heritage recognition and can enable an improved integration of non-European Indigenous values within the management of WH sites.Footnote8 The UNESCO Operational Guidelines (Citation2021) have gradually been adjusted to reflect Indigenous participation and consultation however, greater inclusion of Indigenous traditional knowledge systems are still required in the WHC (Jornet Aguareles Citation2023). WH sites which contain both cultural and natural elements have struggled to overcome often conflicting management approaches (Cocks, Vetter, and Wiersum Citation2018). Natural WH sites have tended towards a naturalistic management emphasis which can be very problematic, not least due to the displacement of Indigenous people and the resultant loss of connection with their traditional land- and water-scapes (Carter Citation2010; Lee and Richardson Citation2017). Arguably, a naturalistic gaze has led to an underrepresentation of non-European Indigenous sites on the WHL (Skilton, Adams, and Gibbs Citation2014). While 10% of WH properties worldwide are located on Indigenous owned land less than forty sites have been inscribed for Indigenous cultural values (Skilton, Adams, and Gibbs Citation2014).

The majority of cultural heritage properties on the WHL are located in European countries (). This spatial unevenness led to a call for a more even distribution of the WH Cultural Landscape category beyond Europe (Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022; Reeves and McConville Citation2011; Winter Citation2014). As previously mentioned, a Eurocentric emphasis has been attributed to the institutional structure of ICOMOS/ICCROM and IUCN experts and assessors, who focus on cultural and natural heritage values as separate entities (Cocks, Vetter, and Wiersum Citation2018; Gfeller Citation2013; Head Citation2000). From the whole dataset, we identified nineteen publications which commented on the biased European regional focus (see for selected examples, Brumann and Gfeller Citation2022; Taylor and Lennon Citation2012; Winter Citation2014; Zhang Citation2017). Scholarship most concerned about the spatial unevenness of the WH Cultural Landscape distribution, came from research based in Australia-Oceania (eleven papers), followed by Asia (six papers). Of the four cultural WH inscribed properties in Australia, Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is the only WH site in Australia to be inscribed entirely for First Nation cultural heritage (Beatty and Unsworth Citation2020). It is distinguished from mixed WH sites in Australia, such as Kakadu National Park and Tasmanian Wilderness. These sites are referred to as living cultural landscapes, but face ongoing management issues due to incompatible heritage values surrounding the presence and absence of people (Lee and Richardson Citation2017; Palmer Citation2007). Authors such as Blair and James (Citation2016) signal that a cultural landscape approach is more inclusive and can recognise Indigenous, post-colonial and natural qualities of WH sites. It may be that the inscription of the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape represents a sign of a gradual shift towards recognising the connection of Indigenous people to landscape (Beatty and Unsworth Citation2020). We suggest that as Budj Bim is currently the only example of this in Australia, it signals a vast under-representation of First Nations cultural heritage in Australia.

As many authors have identified, the siloed approach of the WH listing process further perpetuates a problematic culture-nature dualism for First Nations people (Bridgewater and Upadhaya Citation2022; Head Citation2000; Lee Citation2016; Palmer Citation2007). Palmer (Citation2007) states that mixed cultural and natural listings create an oppositional distinction between the two values that causes tensions about site management leading to a reduction in Indigenous autonomy in managing cultural values for sites which are perceived as ‘natural’. Similarly, Lee (Citation2016) suggests the listing process reinforces a dualism that restricts a First Nations understanding of Country to an artificial view of ‘culture’ and this process ultimately undermines Aboriginal authority, and participation, whilst enhancing the status of natural values in protected area management.

Separation between culture and nature, evidenced in the institutional dynamic of the Advisory Bodies, introduces a tension between the ‘scientific’ management perspective for protected areas and Indigenous spiritual/cultural sensibilities (Blair and James Citation2016; Carter Citation2010). For example, Palmer (Citation2006, Citation2007), uses Kakadu National Park to illustrate that nature should be reframed as a social construction, which takes into account the history of the place and co-existence over time. Many observe that there is a lack of integration between non-Indigenous and Indigenous knowledge systems, where the latter is often disregarded for not meeting criterion for authenticity, credibility and legitimacy and any such values are then subsequently not incorporated within management practices (Draper Citation2015; Palmer Citation2006). Joint management structures are sometimes established to bring together non-Indigenous scientific perspectives with other forms of knowledge (Carter Citation2010; Head Citation2000). Head (Citation2000) illustrates this using Uluru-Kata Tjuta, which is managed through a combination of non-Indigenous European scientific methods, and traditional Anangu practices. This includes recognition of Tjukurpa (the law) across ancestral and present time and traditional management practices such as mosaic burning, hunting and gathering, and reciprocal migration with neighbouring groups (Head Citation2000). Joint management between Anangu and non-Indigenous European experts has led to cross-cultural insights for landscape protection.

Our review reveals that Australian based authors, reflecting on the management of WH properties, have drawn attention to how efforts to incorporate both local and dynamic Indigenous values into heritage protection can yield stronger protection outcomes. Increasing the use of the Cultural Landscape category to enable such practices can also potentially provide for greater recognition of the diversity of heritage across the globe.

Calls for re-nomination using the Cultural Landscape classification

Since the mid-1990s, UNESCO has cited the importance of increasing WH classifications for New World and east-Asian Cultural Landscapes, but this has not yet eventuated, despite significant opportunities (Taylor and Lennon Citation2011). In this section we reflect on the potential of re-nomination using the Cultural Landscape category in an Australian context, which emerged as a key issue in the literature.

Many authors provided recommendations for renomination of existing WH properties as a Cultural Landscape. In twelve papers various authors explicitly made this suggestion. Of these, the Greater Blue Mountains WH Area (Connolly Citation2007; Koch and Gillespie Citation2022), Purnululu (Connolly Citation2007), K’gari (Fraser Island) (Carter Citation2010), Wet Tropics WH Area (Cullen-Unsworth et al. Citation2012), Tasmanian Wilderness WH Area (Lee and Richardson Citation2017), and Kakadu National Park (Blair and James Citation2016; Bridgewater and Upadhaya Citation2022; Palmer Citation2007) were highlighted as current WH properties inscribed under natural or mixed criteria with the potential to be renominated as a Cultural Landscape (Taylor and Lennon Citation2011). These suggestions reflect recent calls from within ICOMOS to move towards a more inclusive heritage framework (ICOMOS Citation2023) and which was emphasised in the ‘Nature-Cultures’ sessions of the 2023 General Assembly Symposium (ICOMOS Citation2023). Moreover, during the Murujuga Cultural Landscape Symposium 2023, the Australian Federal Minister for the Environment, Tanya Plibersek announced a $5.5 million program to reassess Australia’s existing natural WH sites for potential renomination for cultural values, which could provide greater recognition for the Cultural Landscape category (Plibersek Citation2023).

Many scholars identified that multiple WH properties were either described and/or managed as a cultural landscape, but were not currently inscribed as under the category. There were seven site examples, including the Tasmanian Wilderness (Lee and Richardson Citation2017; Pocock, Collett, and Knowles Citation2022), Kakadu National Park (Marshall et al. Citation2022), the Wet Tropics of Queensland (Hill et al. Citation2011; Cullen-Unsworth et al. Citation2012), the Great Barrier Reef (Pocock, Collett, and Knowles Citation2022), K’gari (Carter Citation2010), Purnululu (Connolly Citation2007) and the Greater Blue Mountains (Connolly Citation2007; Koch and Gillespie Citation2022). These authors argue that including intangible/cultural heritage within the definition and criteria for these sites is crucial for better recognition of Indigenous values and influence. Beatty and Unsworth (Citation2020), indicate that intangible/cultural heritage values can be overlooked if not otherwise considered. Skilton et al. (Citation2014) argue that the majority of the Pacific/Oceanic region could be classified as a cultural landscape, as most properties in this region currently on the WHL possess interconnected cultural and natural heritage qualities. In an Australian setting, these papers highlight the strong potential for further utilisation of this category, either through renomination of existing properties or through the nomination of new sites.

By way of example, the Greater Blue Mountains WH Area represents a site which was recognised at the time of nomination as containing significant Aboriginal cultural heritage (including 700 recorded sites, 40% containing some form of rock art) alongside natural heritage values (ICOMOS Citation1999). However, ICOMOS’s evaluation of the site stated that European settlement caused a discontinuity of the ‘intense interrelationship of nature and people over tens of thousands of years’ (ICOMOS Citation1999) and so the Greater Blue Mountains WH Area was ultimately only inscribed for its natural values, which does not reflect how local Aboriginal people view the properties’ heritage (ICOMOS Citation1999).

Shortly after, in 2003, there was another attempt by Australia to recognise the interconnected cultural and natural values with the nomination of Purnululu National Park, this time through the WH Cultural Landscape category (ICOMOS Citation2003). Despite displaying deep time hunter-gatherer traditions, the nomination was rejected by ICOMOS (Citation2003) due to colonial settler arrival and subsequent resource extraction which resulted in the removal of the local Indigenous people (ICOMOS Citation2003). The assessment was uncertain about whether re-inhabitation of the proposed WH area would occur and the ICOMOS (Citation2003) Evaluation cites that ‘a certain number of people will be needed in order to reach a sustainable system, which has a tangible impact on the area’. This suggests even within the Cultural Landscape category there is still a focus on physical heritage, as many of the intangible qualities of Purnululu are unrecorded. Such circumstances highlight the challenge the European WH framework has with assessing and monitoring Indigenous knowledge, ceremonies and oral traditions, which also may be culturally inappropriate to record (Marley Citation2019). An emphasis on protecting authenticity presents a significant challenge for the Cultural Landscape category as it allows for evolution of heritage over time but this can be viewed by the WHC as an erosion of the heritage values (Connolly Citation2007).

As some authors point out, formal designations often prioritise expert over local opinion (Cullen-Unsworth et al. Citation2012; Pocock and Lilley Citation2018). De-emphasising local perspectives potentially means neglect of local heritage values, which may be intertwined with sense of place, spiritual associations, belonging and identity. Scholars such as Carter (Citation2010), Hill et al. (Citation2011), Agnoletti et al. (Citation2015) and Koch and Gillespie (Citation2022) make the point that cultural landscapes can better give voice to concerns of local communities and provide a potential platform for ethical and social justice considerations in managing sites.

Conclusion

This paper provides an overview of publishing trends relating to WH Cultural Landscape properties since its inception as a classification type in 1992. We have used research scholarship as a proxy to indicate where/when the category has been used and to tease out some of the key concerns of scholars relating to the shortcomings and opportunities for WH Cultural Landscape classifications. In terms of regional issues in the Australian/Oceania area, these results suggest that there are clear calls for action, including for renomination of existing WH properties. For example, there are at least nine additional sites in Australia which have been advocated for inscription as Cultural Landscapes, five of which are already inscribed for either natural or mixed heritage values. Many have argued that First Nations heritage in Australia is under-represented on the WHL but the Cultural Landscape category could be used more effectively to, amongst other things, promote Indigenous voices.

The WH Cultural Landscape category enables a wider and more representative protection regime for sites where cultural and natural heritage is inseparable. However, there are still significant barriers preventing further utilisation of this category. These include a lack of a universal definition which may also be contributing to a lack of representation of First Nations heritage sites. The literature clearly identifies these concerns. Many scholars, particularly those writing about Australian/Oceania WH sites, loudly suggest it is time to seriously consider re-nomination of many existing WH properties as a matter of priority under the Cultural Landscape category. For this to occur, a shift in approach is required to acknowledge all environments have been shaped by people and are imbued with cultural meaning. While this is already recognised by the WHC, ICOMOS, and IUCN, there is further work to be done to translate what is already widely known into nomination and re-nomination of WH sites, to redress the under-representation of the Cultural Landscape category worldwide.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by The School of Geosciences Scholarship in Sustainable Futures and University of Sydney Postgraduate Award.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Koch

Emma Koch is a PhD candidate in the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney, Australia. Emma has a Bachelor of Arts (Ancient History) and Science (Environmental Studies) with first class Honours in Geography. Emma’s research investigates the ways in which cultural and natural heritage can be integrated to provide better management outcomes for World Heritage properties.

Josephine Gillespie

Josephine Gillespie is an academic based in the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney, Australia. Josephine researches the complex regulation of protected areas, especially World Heritage properties and Ramsar wetlands.

Notes

1. The authors have intentionally chosen to use culture-nature phrasing to subvert the dominant paradigm which often places an emphasis on nature over culture where both heritage values are present.

2. The English Lake District National Park was first nominated as a rural landscape and used a ‘test case’ for the applicability of the suggested changes to the category (Cameron and Rössler Citation2013). While it met the criteria it was ultimately replaced with the new cultural landscape classification.

3. There is one Cultural Landscape property, ‘Murujuga Cultural Landscape’ on Australia’s Tentative List (UNESCO Citation2020).

4. The results from each database were compiled using EndNote, categorised into geographical region and duplicated papers removed.

5. There is a large body of literature that refers to cultural landscapes but it is not explicitly connected with World Heritage classification so falls outside the scope of this study.

6. This term includes the islands found throughout the Central and South Pacific Ocean, including Australia and New Zealand.

7. This may include the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage 2003 (ICH Convention). The ICH recognises non-material heritage, which is an aspect of cultural landscapes that has traditionally been less considered by the WHC framework.

8. This paper recognises that there are many Indigenous European cultures and heritage, such as the Sami people of Norway. Menzies and Wilson (Citation2020) note that the cultural landscapes category and integration of natural and cultural heritage, is reflective of Indigenous cultures more broadly. While there are similarities, particularly the issue of recognising intangible heritage, this paper is concerned with the unique challenges of non-European Indigenous heritage and management.

References

- Agnoletti, M., M. Tredici, and A. Santoro. 2015. “Biocultural Diversity and Landscape Patterns in Three Historical Rural Areas of Morocco, Cuba and Italy.” Biodiversity and Conservation 24 (13): 3387–3404. [Springer Link]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-1013-6.

- Akagawa, N., and T. Sirisrisak. 2008. “Cultural Landscapes in Asia and the Pacific: Implications of the World Heritage Convention.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14 (2): 176–191. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Aplin, G. 2007. “World Heritage Cultural Landscapes.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 13 (6): 427–446. [Taylor & Francis Online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250701570515.

- Beatty, A., and T. Unsworth. 2020. “Indigenous and Environmental Law: The Legal Implications of Australia’s Latest World Heritage Site.” Law Society Journal 63:86–87. [LSJ Online].

- Blair, S., and D. James. 2016. “Indigenous Heritage at Australia’s Northern and Western Pastoral Frontiers.” Historic Environment 28 (1): 70–84. [Informit].

- Bridgewater, P., and C. Bridgewater 2004. “Is There a Future for Cultural Landscapes?” Paper presented at the New Dimensions of the European Landscape. [Web of Science ®]

- Bridgewater, P., I. D. Rotherham, and R. Rozzi. 2019. “A Critical Perspective on the Concept of Biocultural Diversity and Its Emerging Role in Nature and Heritage Conservation.” People and Nature 1 (3): 291–304. [British Ecological Society]. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10040.

- Bridgewater, P., and S. Upadhaya. 2022. “Biocultural, Ecocultural, or just plain Cultural? Genes and Memes in Cultural Landscape conservation.” In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Heritage in the Asia-Pacific, edited by K. D. Silva, K. Taylor, and D. S. Jones, 108–122. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Taylor & Francis Group].

- Brumann, C., and A. É. Gfeller. 2022. “Cultural Landscapes and the UNESCO World Heritage List: Perpetuating European Dominance.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28 (2): 147–162. [Taylor & Francis Online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1941197.

- Buckley, K. 2022. “Thirty Years of World Heritage Cultural Landscapes.” In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Heritage in the Asia-Pacific, edited by K. D. Silva, K. Taylor, and D. S. Jones, 60–77. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Routledge Taylor & Francis Group].

- Cameron, C., and M. Rössler. 2013. Many Voices, One Vision: The Early Years of the World Heritage Convention, 1–330. London, UK: Routledge. [Routledge Taylor & Francis Group].

- Carmody, L. 2016. “Tangible and Intangible Heritage: Cultural Landscapes in Columbia and Indonesia.” Perth International Law Journal 1:59–71. [Informit].

- Carter, J. 2010. “Displacing Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: The Naturalistic Gaze at Frazer Island World Heritage Area.” Geographical Research 48 (4): 398–410. [Wiley Online Library].

- Cocks, M., S. Vetter, and K. F. Wiersum. 2018. “From Universal to Local: Perspectives on Cultural Landscape Heritage in South Africa.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (1): 35–52. [Taylor & Francis Online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1362573.

- Connolly, I. 2007. “Can the World Heritage Convention Be Adequately Implemented in Australia without Australia Becoming a Party to the Intangible Heritage Convention?” Environmental and Planning Law Journal 24 (3): 198–209. [Scopus].

- Cullen-Unsworth, L. C., R. Hill, J. R. A. Butler, and M. Wallace. 2012. “A Research Process for Integrating Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge in Cultural Landscapes: Principles and Determinants of Success in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, Australia.” The Geographical Journal 178 (4): 351–365. [Royal Geographical Society].

- Dailoo, S. I., and F. Pannekoek. 2008. “Nature and Culture: A New World Heritage Context.” International Journal of Cultural Property 15 (1): 25–47. [Cambridge University Press].

- Draper, N. 2015. “Recording Traditional Kaurna Cultural Values in Adelaide - the Continuity of Aboriginal Cultural Traditions within an Australian Capital City.” Historic Environment 27 (1): 78–89. Informit.

- Fowler, P. J. 2003. “World Heritage Cultural Landscapes 1992-2002. World Heritage Papers 6. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. [UNESCDOC Digital Library]

- Gentry, K., and L. Smith. 2019. “Critical Heritage Studies and the Legacies of the Late-Twentieth Century Heritage Canon.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11): 1148–1168. [Taylor & Francis Group]. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1570964.

- Gfeller, A. E. 2013. “Negotiating the Meaning of Global Heritage: ‘Cultural Landscapes’ in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, 1972-92.” Journal of Global History 8 (3): 483–503. [Cambridge University Press].

- Gillespie, J. 2012. “Buffering for Conservation at Angkor: Questioning the Spatial Regulation of a World Heritage Property.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18 (2): 194–208. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Head, L. 2000. Cultural Landscapes and Environmental Change. London, UK: Arnold. [Taylor & Francis Group].

- Hill, R., L. C. Cullen-Unsworth, L. D. Talbot, and S. McIntyre-Tamwoy. 2011. “Empowering Indigenous Peoples’ Biocultural Diversity Through World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Case Study from the Australian Humid Tropical Forests.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17 (6): 571–591. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- ICOMOS. 1981. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 167, Willandra Lakes Region (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/167/documents/.

- ICOMOS. 1989. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 181, Tasmanian Wilderness (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/181/documents/.

- ICOMOS. 1991. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 147, Kakadu National Park (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/147/documents/.

- ICOMOS. 1994. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 447rev, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/447/documents/

- ICOMOS. 1999. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 917, Greater Blue Mountains Area (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/917/documents/.

- ICOMOS. 2003. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 1094, Purnululu National Park (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1094/documents/.

- ICOMOS. 2017. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 422rev, the English Lake District (United Kingdom). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/422/documents.

- ICOMOS. 2023. ICOMOS 21st General Assembly and Scientific Symposium. Sydney: ICOMOS. https://icomosga2023.org/.

- ICOMOS Australia. 2013. The Burra Charter. Australia https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf.

- IUCN. 1987. Advisory Body Evaluation. No. 447, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (Australia). Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/447/documents/.

- Jornet Aguareles, C. 2023. “Indigenous-Based Heritage Management of UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Rapa Nui and the Indigenous Governance of the Rapa Nui National Park.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 29 (5): 413–427. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Koch, E., and J. Gillespie. 2022. “Separating Natural and Cultural Heritage: An Outdated Approach?” The Australian Geographer 53 (2): 1–15. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Lee, E. 2016. “Protected Areas, Country and Value: The Nature-Culture Tyranny of the IUCN’s Protected Area Guidelines for Indigenous Australians.” Antipode 48 (2): 355–374. [Wiley Online Library].

- Lee, E., and B. J. Richardson. 2017. “From Museum to Living Cultural Landscape: Governing Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage.” Australian Indigenous Law Review 20:78–107. [Informit].

- Losson, P. 2017. “The Inscription of Qhapaq Ñan on UNESCO’s World Heritage List: A Comparative Perspective from the Daily Press in Six Latin American Countries.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (6): 521–537. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Marley, T. L. 2019. “Indigenous Data Sovereignty: University Institutional Review Board Policies and Guidelines and Research with American Indian and Alaska Native Communities.” The American Behavioral Scientist (Beverly Hills) 63 (6): 722–742. [Sage Journals].

- Marshall, M., K. May, J. Lee, and G. O’Loughlin. 2022. “Looking After the Rock Art of Kakadu National Park, Australia.” Studies in Conservation 67 (S1): 156–165. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- McBryde, I. 1997. “The Cultural Landscapes of Aboriginal Long Distance Exchange Systems: Can They Be Confined within Our Heritage Registers?” Historic Environment 13 (3/4): 6–14. [Informit].

- McBryde, I. 2014. “Reflections on the Development of the Associative Cultural Landscapes Concept.” Historic Environment 26 (1): 14–32. [Informit].

- Menzies, D., and C. Wilson. 2020. “Indigenous Heritage Narratives for Cultural Justice.” Historic Environment 32 (1): 54–69. [Informit].

- Palmer, L. 2006. “‘Nature’, Place and the Recognition of Indigenous Polities.” The Australian Geographer 37 (1): 33–43. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Palmer, L. 2007. “Interpreting ‘Nature’: The Politics of Engaging with Kakadu As an Aboriginal Place.” Cultural Geographies 14 (2): 255–273. [Sage Journals].

- Perez, R. S., and V. F. Salinas. 2015. “The Cultural Landscapes of UNESCO from the Latin American and the Caribbean Perspective. Conceptualizations, Situations and Potentials.” Revista INVI 30 (85): 181–212. [Scopus].

- Plibersek, T. 2023. “Minister’s Address: Murujuga and Australia’s World Heritage List.” Presented at the ICOMOS Murujuga Cultural Landscape Symposium. Sydney Australia September. [ICOMOS GA 2023].

- Pocock, C., D. Collett, and J. Knowles. 2022. “World Heritage As Authentic Fake: Paradisic Reef and Wild Tasmania.” Landscape Research 47 (8): 1024–1038. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Pocock, C., and I. Lilley. 2018. “Who Benefits? World Heritage and Indigenous People.” Heritage & Society 10 (2): 171–190. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Poroch, N. C. 2014. “Kurunpa: Keeping Spirit on Country.” Health Sociology Review 21 (4): 383–395. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Reeves, K., and C. Long. 2011. “Unbearable Pressures on Paradise? Tourism and Heritage Management in Luang Prabang, a World Heritage Site.” Critical Asian studies 43 (1): 3–22. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Reeves, K., and C. McConville. 2011. “Cultural Landscape and Goldfield Heritage: Towards a Land Management Framework for the Historic South-West Pacific Gold Mining Landscapes.” Landscape Research 36 (2): 191–207. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Rössler, M. 2019. “Rural Landscapes and Sustainable Development: International Day for Monuments and Sites 2019.” UNESCO. April 18 2019. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1959.

- Rössler, M., and R. C. H. Lin. 2018. “Cultural Landscape in World Heritage Conservation and Cultural Landscape Conservation Challenges in Asia.” Built Heritage 2 (3): 3–26. [SpringerOpen].

- Russell, J., and M. Jambrecina. 2002. “Wilderness and Cultural Landscapes: Shifting Management Emphases in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.” The Australian Geographer 33 (2): 125–139. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Saintenoy, T., F. G. Estefane, D. Jofre, and M. Masaguer. 2019. “Walking and Stumbling on the Paths of Heritage-Making for Rural Development in the Arica Highlands.” Mountain Research and Development 39 (4): D1–D10. [BioOne Digital Library].

- Sauer, C. O. 1925. The Morphology of Landscape. [Google Books]. University of California Press.

- Silva, K. D., K. Taylor, and D. S. Jones, edited by. 2022. The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Heritage in the Asia-Pacific, 1–580. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Taylor & Francis Group]

- Skilton, N., M. Adams, and L. Gibbs. 2014. “Conflict in Common: Heritage-Making in Cape York.” The Australian Geographer 45 (2): 147–166. [Taylor & Francis Online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2014.899026.

- Smith, A., I. J. McNiven, D. Rose, S. Brown, C. Johnston, and S. Crocker. 2019. “Indigenous Knowledge and Resource Management As World Heritage Values: Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, Australia.” Archaeologies 15 (2): 285–313. [Springer Link].

- Taylor, K. 2009. “Cultural Landscapes and Asia: Reconciling International and Southeast Asian Regional Values.” Landscape Research 34 (1): 7–31. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Taylor, K., and K. Altenburg. 2006. “Cultural Landscapes in Asia-Pacific: Potential for Filling World Heritage Gaps.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (3): 267–282. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Taylor, K., and J. Lennon. 2011. “Cultural Landscapes: A Bridge Between Culture and Nature?” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17 (6): 537–554. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Taylor, K., and J. Lennon. 2012. Managing Cultural Landscapes. Oxon: Routledge. [Routledge Taylor & Francis Group].

- Taylor, K., D. K. Silva, and D. S. Jones. 2022. “Introduction. Managing Cultural Landscape Heritage in the Asia-Pacific.” In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Heritage in the Asia-Pacific, edited by K. D. Silva, K. Taylor, and D. S. Jones, 1–28. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Taylor & Francis Group].

- Trau, A. M., C. Ballard, and M. Wilson. 2014. “Bafa Zon: Localising World Heritage at Chief Roi Mata’s Domain, Vanuatu.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (1): 86–103. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- UNESCO. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/.

- UNESCO. 1985. World Heritage Committee: Report of the Nineth Ordinary Session, CONF.008/3. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/1985/sc-85-conf008-3e.pdf.

- UNESCO. 1987. World Heritage Committee: Report of the Eleventh Ordinary Session, CONF. 005. Decision 11 COM Viib.B. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/3756.

- UNESCO. 1990. World Heritage Committee: Report of the Fourteenth Ordinary Session, CONF.004. Decision 14 COM VIID. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/3575.

- UNESCO. 1992. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide92.pdf.

- UNESCO. 1994. World Heritage Committee: Report of the Eighteenth Ordinary Session, CONF. 003/7. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/1994/whc-94-conf003-7e.pdf.

- UNESCO. 1999a. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide99.pdf.

- UNESCO. 1999b. “Report of the Regional Thematic Expert Meeting on Cultural Landscapes in Eastern Europe.” Bialystok: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/1999/whc-99-conf209-inf14e.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2003. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. [online]. https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-safeguarding-intangible-cultural-heritage.

- UNESCO. 2019. World Heritage Committee: Report of the Forty-Third Ordinary Session, 42. COM. Decision 43 8B.14. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2019/whc19-43com-18-en.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2020. “Murujuga Cultural Landscape”. UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6445/.

- UNESCO. 2021. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/.

- UNESCO. 2023. “World Heritage List”. UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/.

- UNESCO. n.d. “Cultural Landscapes.” UNESCO. Accessed September 2, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/.

- Wallace, P., and K. Buckley. 2015. “Imagining a New Future for Cultural Landscapes.” Historic Environment 27 (2): 42–56. [Informit].

- Winter, T. 2014. “Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage Conservation and the Politics of Difference.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (2): 123–137. [Taylor & Francis Online].

- Wylie, J. 2007. Landscape. London: Routledge. [Taylor & Francis Group].

- Zhang, R. 2017. “World Heritage Listing and Changes of Political Values: A Case Study in West Lake Cultural Landscape in Hongzhou, China.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (3): 215–233. [Taylor & Francis Online].