ABSTRACT

Japanese immigration to the U.S. began in the late 1800s. Japanese immigrants and later their children were mostly engaged in agriculture; however, some owned nurseries and gardening or landscaping businesses. Following the outbreak of World War II, most Japanese and Japanese Americans were sent to one of ten incarceration camps, one of which was Amache, in the High Plains of Colorado. Inmates there planted trees and created hundreds of gardens to improve its stark institutional landscape. These gardens were located in the front of individual barracks and other public spaces. They formed the most significant landscape element within the camp and helped Japanese inmates retain their identities during wartime. This study focuses on two Japanese-style gardens created in the public spaces of barracks Blocks 6H and 12F in the Amache incarceration camp. Framed by archival research on professional gardener associations and the Japanese language section of the camp newspaper, it explores the significance of these Japanese-style gardens, revealing the value and role the gardens played among Japanese detainees. It also reveals the long-term impact of these gardens as a material legacy.

Introduction

Japan is rightly known for its exquisitely designed gardens, which have evolved for millennia with its climate and culture. For over 150 years, Japanese inspired gardens, built by both those of Japanese heritage and others have been replicated worldwide. As argued by garden historian Kendall Brown, when found outside of Japan, these expressions are most accurately called ‘Japanese-style’ gardens (Brown Citation2020). These Japanese-style gardens are not necessarily only Japanese-inspired in terms of design, construction techniques, and elements, but they utilise many techniques or components of Japanese gardens, often employing local materials (Keane Citation1996). Keane (Citation1996) also concludes that a Japanese or Japanese-style garden is not determined solely by its design, but there is something more essential to the gardens. Brown reinforces and describes Japanese-style gardens as those that ‘bring us closer to nature, even if it’s an idealised version, and enable us to restore ourselves physically and mentally’ (Brown Citation2020).

In the U.S., there are Japanese-style gardens of various sizes and styles, but among the most notable are those created in incarceration camps during World War II. After Pearl Harbour, Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were incarcerated primarily in ten facilities built by the War Relocation Authority. Japanese-style gardens were developed in all of these camps, often using whatever materials could find around the camp (Burton and Farrell Citation2014). While gardening cannot be classified solely as a recreational pursuit, it offered detainees the opportunity to connect with nature and embrace their surrounding environment (Chiang Citation2019). For example, Ozawa (Citation2016, Citation2020) reported that Japanese-style gardens played a role of providing spaces to create and maintain their communal identity in the Gila River incarceration camp. The scale of Japanese-style gardens established in the camps varies, but the presence of these gardens enhanced the aesthetic appeal of the camps and reinforced the detainees’ sense of cultural identity (Helpland Citation2006).

Among the Japanese-style gardens in incarceration camps, the gardens at Minidoka and Manzanar have drawn attention as nationally significant cultural landscapes that became units of the National Park System in the 1990s (Camp Citation2016). Numerous studies conducted on gardens situated in Manzanar National Historic Site have not only elucidated the distinctive characteristics of these gardens but have also shed light on the individuals responsible for their creations (Ng Citation2014; Suto and Voeks Citation2021; Tamura Citation2004). Under the direction of archaeologist Jeffery Burton, extensive study of these gardens continues (e.g. Burton and Farrell Citation2014).

A, Comprehensive research at Amache began as a collaborative archaeology and museum studies project initiated by Bonnie Clark at the University of Denver, undertaken following the site’s official designation as a national historical landmark in 2006 (Clark and Shew Citation2021). Today, the remains of over a dozen Japanese-style gardens have been excavated in Amache as integral components of the cultural heritage of the imprisoned community. In addition, survey by archaeology crews has documented even more evidence of detainee-created landscaping, including thousands of trees and hundreds gardens at the site. Both survey and excavation data up through the 2018 field seasons have been comprehensively explored in Clark’s book Finding Solace in the Soil: An Archaeology of Gardens and Gardeners at Amache (Clark Citation2020). These features have also been explored in thesis research by graduate students involved in the project. Notably, Garrison (Citation2015) explored the integrity of gardens and implications for Japanese-American identity, specifically focusing on entryway gardens among Japanese-style gardens discovered at the site. In part due to the comprehensive work of the archaeology team, Amache became a unit of the U.S. National Park System in 2024. The park foundation document explicitly identifies the remains of landscaping and especially gardens as fundamental resources “essential to achieving the purpose of the park and maintaining its significance (NPS, Citation2024, 10).

However, there is more work to be done. The Amache archaeology project continues to uncover new gardening features. As this work explores, here are also discoveries to be made in the archives – especially sources in Japanese – which reveal more about the roles of these gardens and their influence on detainees. This article deepens understanding of the significance and value of these gardens using avenues that remain underexplored in the existing literature, such as 3D modelling. This article applies new techniques and new data to explore the significance of two ornamental Japanese-style gardens constructed within the Amache incarceration camp, one newly discovered and one previously discussed by Clark (Citation2020). These new analyses unveil the value and roles played by these gardens among Japanese inmates and their influence on detainees after leaving the camp as a momentous heritage.

Materials and methods

The site – Amache

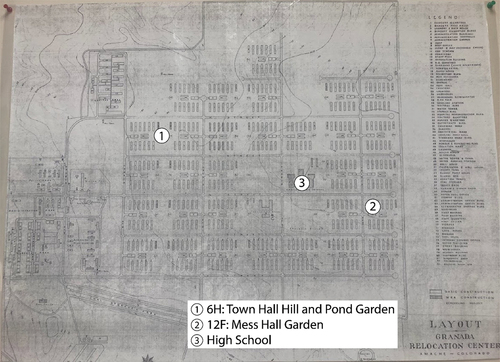

This work includes archival and field study at the Amache National Historic site in southeastern Colorado. Also known as the Granada Relocation Centre, it was one of ten incarceration sites established by the War Relocation Authority during World War II (). The site covered approximately 10,500 acres south of the Arkansas River and extended three miles west and four miles east of the small town of Granada, Colorado.

Amache is situated in the High Plains, which is a gently undulating sandy grassland stretching between the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains. This region has a semi-arid climate characterised by low humidity and moderate annual precipitation. The summer season is characterised by hot and dry conditions, occasionally accompanied by intense thunderstorms and tornadoes, whereas winters tend to be cold and dry, with occasional snowfall. Throughout the year, this area frequently encounters high wind velocities, which can lead to heavy dust storms.

Materials

The primary archival materials used in this study were ‘Gardener’s Monthly’ and ‘Granada Pioneer’. ‘Gardener’s Monthly’ is an industrial magazine published by the League of Southern California Japanese Gardeners (LSCJG) in Los Angeles, as discussed in detail in later sections. The ‘Gardener’s Monthly’ was started by the leader of the LSCJG, Shoji Nagumo. According to the Southern California Gardeners’ Federation, which inherited the LSCJG after World War II, the origin of this magazine was newsletters for members, and it became a monthly magazine, the oldest surviving record being the April 1940 issue. The magazine was published every month from April 1940 to December 1941 until World War II began. The magazine was in Japanese, had advertisements that averaged approximately 20 pages, and contained many educational articles and information related to landscaping jobs. It also included articles on the lives of Japanese gardeners, covering aspects such as their grievances, experiences with racism, and difficulties in finding employment.

A key resource specifically related to Amache is the ‘Granada Pioneer’, the camp newspaper, which was primarily written in English, with two or more pages in Japanese at the back of each issue. It was published on Wednesdays and Saturdays from 14 October 1942 to 15 September 1945 and covered a wide range of topics related to camp activities, including routine administrative matters regarding camp infrastructure management and occasional events and activities, and news concerning the ravages of war. Notably, there were four issues of the ‘Granada Pioneer’ that featured a special page called the ‘Granada Bungei’, which showcased detainees’ haiku and other forms of poetry. These poems provide valuable insights into the emotions and thoughts of individuals at the time, which will be explored in greater detail later in this article.

Archaeological field data collected by the DU Amache Project, including maps created during excavations as well as field photographs were also key to this work.

3D modelling materials

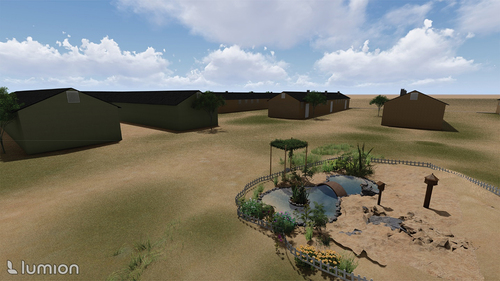

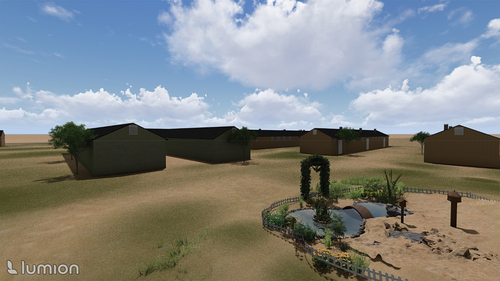

In this study, 3D modelling played a crucial role in the analysis of the gardens. To facilitate a comprehensive comparison between the present state of gardens and their original conditions at the time of construction, 3D modelling techniques were employed to recreate the missing elements. Based on the current condition model, which was captured using PIX4D catch, a mobile application by Pix4D S.A., Switzerland, for ground 3D scans, enables the acquisition of the right terrestrial data for digitising reality into accurate 3D models. Other missing elements were created using Rhino6, a 3D modelling software that allows for the creation of a freeform surface model by Robert McNeel & Associates, U.S. The model of garden was imported into Sketchup Pro 2023 where surrounding barracks and landscapes were constructed. Sketchup Pro 2023 is another 3D modelling software that allows to create and manipulate 3D models of buildings, landscape objects by Trimble, U.S. The entire model was brought into Lumion Student 2023, 3D rendering software that enables to visualise landscape by Lumion, France, to locate vegetation and texture in model. This approach proved to be instrumental in unravelling the spatial composition of the gardens, providing insights that surpass the limitations of traditional photography in conveying accurate and detailed information. In essence, 3D models significantly enhance comprehension of the gardens’ roles within the camp environment, particularly regarding surrounding vegetation and barracks. The digitisation of historic gardens visualises excavated ruins and lost elements separately, potentially offering insights beyond what 2D photographs can convey. Additionally, 3D models offer a compelling avenue for public engagement, enabling broad access to the visualisation of historical gardens without the reliance on physical or life-sized replicas, while concurrently remaining impervious to the influence of meteorological condition. 3D models can also effectively illustrate the transition between various time periods at the camp, showcasing different stages of the gardens based on the historic photographs.

Methods

This study employed a comprehensive literature review as a foundation for gathering relevant information and drawing insights from existing studies related to the research topic. The study focused on two prominent public ornamental Japanese-style gardens: a Hill and Pond Garden, situated in Block 6H, and a Mess Hall Garden, located in Block 12F. The combination of a literature review, field research, and 3D modelling in this study provided a robust and comprehensive approach for examining Hill and Pond Garden and Mess Hall Garden. By leveraging these diverse methods, we aimed to offer a nuanced and holistic understanding of Japanese-style gardens and their historical and contemporary cultural importance. This methodological approach ensured the reliability and validity of our findings and enabled a deeper exploration of the research topic.

Japanese immigrants and gardens before world war II

Japanese immigration to the U.S. began in 1868, with Hawaii and the Pacific coast becoming the most popular destinations. More than 400,000 Japanese men and women migrated to the U.S. between 1886 and 1911 at a steadily increasing rate. Initially, they came to the U.S. mostly for temporary jobs and planned to return to Japan. Early arrivals established themselves along the Pacific coast and formed small communities in different cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Portland, which later developed into Japanese Towns (Library of Congress, Citationn.d..).

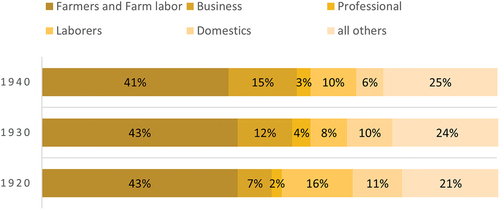

The history of the first Japanese immigrants (also known as Issei) is also their labour history, and Issei engaged in urban service trade and agricultural, railroad, mining, lumber, and fishing industries (Ichioka Citation1988). Between the 1920s and the 1940s, farmers and farm labourers comprised approximately half of the Japanese immigrant population, as shown in

Figure 2. Japanese immigrant occupation, created by author, referred to Suzuki, Masao. 1995. ‘Success Story? Japanese Immigrant Economic Achievement and Return Migration, 1920–1930’. the Journal of Economic History 55 (4): 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700042200.

However, some immigrants established businesses, such as nurseries and small shops (Library of Congress, Citationn.d..). Hiroshi Yoshiike began to grow flowers commercially in 1886 and became the first Japanese floriculturist in the U.S. Since then, nurseries became another type of business for the Japanese population, and in 1891, Issei began to engage in yard care, marking their entry into the ‘gardening’ occupation. Since the early twentieth century, Issei gardeners have gained a reputation as the ‘finest in garden maintenance’ (Chiang Citation2019).

One of the earliest Japanese gardens built in the U.S. was the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition at Fairmount Park in 1876. It was one of many Japanese-style gardens constructed for exhibitions at world fairs and expositions appreciated by the American mainstream (Tamura Citation2004). These gardens were designed and constructed by first-(Issei) or second-(Nisei) generation Japanese immigrants (Brown Citation1999). Many West Coast-based Japanese-style gardeners collaborated in the construction of Japanese-style gardens (Esaki Citation2013). Some Japanese-style gardens set up at the World’s Fair continued to be maintained as parks, such as the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. These gardens became an important cultural experience for many Japanese immigrants in the West (Brown Citation1999), as shown in .

The league of Southern California Japanese gardeners

In 1926, the first gardener organisation was established in Southern California. In 1933, three gardeners’ associations were established in Southern California, specifically in Hollywood, Uptown Los Angeles, and West Los Angeles, under Shoji Nagumo’s leadership. Nagumo is called the father of Southern California gardeners because he has contributed significantly to gardener organisations and education. By December 1934, nearly one-third of the Japanese labour force in Los Angeles (1500 men) comprised gardeners. The League of Southern California Japanese Gardeners (LSCJG), established in 1937 based on the these earlier three gardener associations, had 900 members by 1940. Of these, 250 were from Hollywood, 300 were from Uptown LA, and 350 were from West LA (Naomi Hirahara, Citation2000). The LSCJG was active until the Pearl Harbour attack.

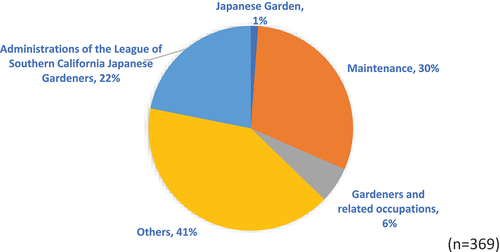

The LSCJG held regular meetings, seminars, and workshops to provide education and training on various aspects of landscaping, including the design of Japanese gardens. It became a major centre for sharing information and skillsets among Japanese gardeners on the West Coast. For this organisation, Shoji Nagumo started a monthly magazine called the ‘Gardeners Monthly’. Among all the articles published between April 1940 and December 1941, those relating to Japanese gardens comprised only approximately 1%, as shown in .

However, these articles were written by Japanese garden experts. For example, in November 1940, the magazine published part of a letter about the trends in Japanese gardens from Kannosuke Mori, a well-known Japanese garden designer and landscape architecture professor at Chiba High School in Japan. This article suggests that the LSCJG had connections with professional gardeners in Japan. Thus, the LSCJG provided knowledge regarding traditional Japanese gardening practices and aesthetics from professionals in Japan, and this knowledge was shared with the families and community networks of immigrants, which may have influenced the creation of Japanese gardens in incarceration camps.

In February 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which paved the way for the creation of military zones from which ‘any and all persons’, (including U.S. citizens) could be removed. Soon thereafter, all individuals of Japanese ancestry living in the newly-created exclusion zones, which included all of California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona, were removed, first to temporary detainment camps while the more permanent facilities were constructed. The Amache incarceration camp was established on 27 August 1942, and 98% of the detainees at the camp were from California and 7% were engaged in gardening-related jobs. Each camp undertook the task of organising a community, which included assuming responsibility for cleaning and landscaping the grounds (Helpland Citation2006, 157) The presence of these individuals with prior experience in gardening and landscaping played a key role in facilitating the construction of Japanese-style gardens within Japanese incarceration camps.

Two Japanese-style gardens at Amache

All ten of the incarceration camp sites are similar in terms of their functions, size, and layout of army-style barracks. Each were purposely placed in remote locations that were typically characterised by extreme and harsh climates such as deserts or swamps. Yet each camp is also unique, with geography and climate that created specific opportunities and challenges. These are reflected in the Japanese-style gardens at each camp, as the location changed the materials available for garden creation. In Manzanar, there are tremendous amounts of rocks and abundant water resources that had been brought to Japanese-style gardens; Amache’s extreme conditions did not allow excessive use of water, and resources such as rocks were significantly limited (Burton et al. Citation2002; Clark Citation2020; Clark and Shew Citation2021; Ng Citation2014; Tamura Citation2004). Hundreds of gardens have been identified by archaeologists at Amache and using categories applied to other War Relocation Authority camps, they have been classified into three styles: public ornamental gardens, vegetable or ‘victory’ gardens, and entryway gardens, which are located in front of barrack buildings (Clark Citation2020). This article focuses on two prominent public ornamental Japanese-style gardens, namely the Hill and Pond Garden located in Block 6H and the Mess Hall Garden located in Block 12F, as shown in .

Figure 5. Plan view of the blocks in the camp and the location of the gardens. Created based on Layout Granada Relocation Center, by author, 2023.

As Garrison (Citation2015) mentioned, Japanese-style gardens served as symbols of the camps for detainees and they are cherished with pride and admired by the War Relocation Authorities; therefore, we carefully selected these two gardens, which were created in public. They exhibited crucial characteristics indicative of collaborative efforts in their creation, which will be elaborated in subsequent sections.

During the operation from 1942–1945, more than 10,000 people passed through the Amache incarceration camp. According to the former incarceree database compiled by the DU Amache Project, 97.7% were from California, and 32% of those from California were from Los Angeles. In the camp, the primary occupations of 3,636 people were recorded, and 7% were related to gardening. Further breaking those numbers down, 5% were gardeners, groundskeepers, or worked in parks or cemeteries. One percent ran nurseries or were floriculturists, and 1% were nursery or landscape labourers. It is difficult to determine the number of gardeners from Los Angeles because the member lists of the LSCJG are not available. However, Tetsujiro Takai, a gardener from Los Angeles, was mentioned in the Gardener’s Monthly in January 1941 as an associate of the organisation. He lived in Block 12K, apartment 1E. There were likely more members of the LSCJG like him in Amache.

There were other trained landscape professionals among the detainees. For example, Kaneji Domoto studied landscape architecture at UC Berkeley and worked with Frank Lloyd Wright. The Domoto family was ‘the largest importer of nursery stock on the Pacific Coast’ (Guest Citation2020). They played a major role in planting trees in Block 6F, where Kaneji Domoto lived (Clark Citation2020, 90). Similarly, in Block 12H, the Shigekuni family played an important role. The family operated a nursery in California. People with professional nursery experience assisted in planting trees, even in blocks where detainees with such experience lived, such as Block 7H (Clark Citation2020, 87). In addition to planting trees, Kaneji Domoto was a block representative of 6F and designed a plan for building a porch and landscaping at the entrance of the camp’s Boy Scout Headquarters (Clark Citation2020, 90). Kaneji’s brother, Toichi Domoto, lived in Block 6H, and he and others with professional horticultural backgrounds were likely involved in the construction of the Japanese-style garden there.

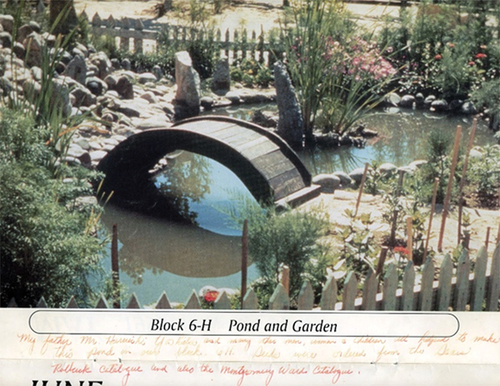

shows a WWII-era colour photograph of the 6H garden which evidence shows how stones and plants were laid out in the garden.

Figure 6. Historic photograph of 6H garden from 1998 calendar prepared for an Amache reunion. Annotations by Kazie Yoshida Aoiki. Courtesy, Amache Preservation Society, Granada, CO.

Many stones were brought into the camp from the nearby Arkansas River. The tall grasses at the water’s edge were also from the river, and the small pine saplings visible in the bottom right corner of the photograph must have been brought from afar or purchased at a nursery because pine trees do not grow in this area. Two bird houses were installed on the hill, and the block number ‘6H’ was inscribed on the one in the foreground, as shown in .

Figure 7. Historic photograph by Jack Muro of wooden bird houses in the 6H garden. Courtesy, DU Amache Project.

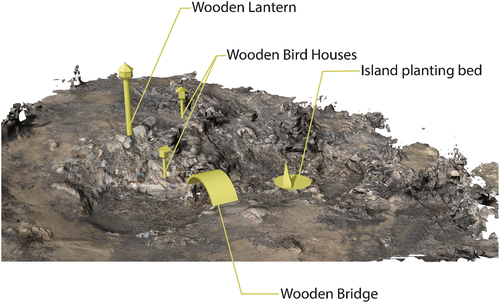

shows a 3D model of the 6H garden ruins with the restored bridge, bird houses, and vertical stone present on the island in the old photographs, as shown in and .

Figure 8. Features of the 6H garden. 3D model created by author, based on the current condition model, which was captured by Pix4D Catch provided by Jim Casey.

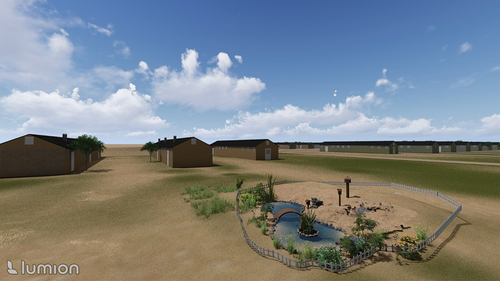

The shape and size of real stones available for the garden were limited, and concrete pieces that were the by-product of camp construction were used when more vertical elements were desired. From this model, we can observe that the pond was shaped like a gourd, which was the typical shape used for ponds in small residential Japanese-style gardens. The pond was spanned by an approximately 1 m-long semi-circular bridge connected to a hill. The height of the hill was only about 1.5 m. shows the surrounding environment around the garden and helps us better conceptualise the scale of the garden and barracks. and also depict the 6H garden at various times. The pergola models are derived from historic photographs taken during different periods in the camp. Although this garden was small in scale, it was packed with elements of a Japanese garden, that is water, a hill, a bridge, stones, and vegetation, which are also found in hill and pond gardens in Japan.

Figure 9. 6H garden in place, showing surrounding barracks and landscape. 3D model created by author. Buildings at Amache were commonly clad in asphalt roll roofing of either a tan or green colour. Based on historic photographs, the buildings in Block 6H where the garden is located were tan and the buildings in adjacent Block 7H were green. The colour of the cladding for buildings the background block (7K) portrayed in Figure 9 are unknown. For this image I have chosen to also represent them as tan.

Figure 10. 6H garden in place with a pergola, showing a different time period from Figure 9 and Figure 11.

Unlike the 6H garden, no photographs or other documentation of the 12F Mess Hall Garden remain, and archaeological evidence is the only source for learning about this garden. The incarceree database compiled by the DU Amache Project indicates that many of the residents of block 12F were farmers prior to the war. However, there were also three gardeners and two nursery professionals in this block, including a gardener, Kameju Kai, who came to the U.S. at the age of 24 (National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], Citation1900–1953). These few professionals were likely to be involved in making this garden with other residents.

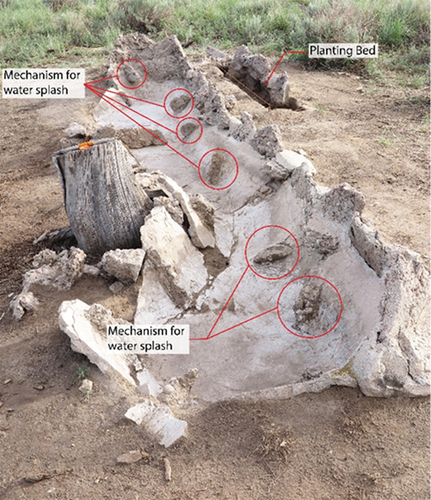

Its archaeological plan, as shown in , shows that the garden had varying elevations and a drain hole, suggesting that at least on occasion, it had cascading water. Analysis of the diatoms (remains of single cell algae common to aquatic environments) excavated from the base of the pond suggest that it was filled with water, but that it was either primarily still or a low energy flow (Rogers Citation2024).

The ruins shown in also indicate that the basin had multiple bumps on the sides to ensure that the water splashed when it did flow.

Figure 13. Excavated 12F basin and its features. Created by author, based on a photo provided by the DU Amache Project.

It is difficult to determine exactly how the detainees set up the flowing water in the feature, although the proximity to the plumbed mess hall is the most likely source. Even if the water only flowed occasionally, this garden with its water-filled feature and the shade of a tree would have offered block residents and visitors a sense of coolness.

Japanese detainees and their thoughts on gardens

This was a period of time in which expressions of Japanese identity were fraught. There was a strong nationalism and militarism in homeland Japan that problematised the identity of those abroad. Both personal correspondence, and English-language articles in the Granada Pioneer were censored (Gebhard Citation2015). In these traumatic circumstances, it is very difficult to know detainees’ honest feelings, and it could be harder for them to recall these feelings even after incarceration. However, the camp landscape and the detainees’ emotions can be perceived through their poems. We can retrieve them from the four issues in the Granada Pioneer, which had a special page called the ‘Granada Bungei’, which contained detainees’ haiku and other styles of poems. Overall, these poems convey a range of emotions of detainees concerning the camp, the surrounding landscapes, and their personal experiences. From this collection, we selected five poems that notably captured their profound feelings of anxiety and nostalgia, while also providing a vivid depiction of the alternation of their surrounding environment. They serve as valuable evidence that provides honest insights that were probably not always revealed in public during confinement.

In the camp, detainees were forced to live inconveniently in harsh weather, and confusion about sudden changes in their situation is evident in the poem. For instance, in the poem below, which was contributed to the Granada Bungei on 23 January 1943, the author describes themself as vanishing smoke, which reflects people’s anxiety about their life in an unfamiliar place in the desert.

静かき朝・人影は見えず・煙突から煙ばかり・まるで煙の音の如く・今の我等は消えていく (Densho, Citationn.d.)

Silent morning, I don't see any shadows of people, but what I see is only smoke from the chimney, what we are now is going to fade as if the sound of smoke.

The camp conditions during the first year were particularly harsh, before detainees made changes to these facilities that lacked privacy and basic amenities. Because the barracks in which they lived were cheaply constructed, uninsulated housing and the hot summers and cold winters added to the challenges faced by the detainees (Eggleston Citation2012). A poem that was contributed to Granada Bungei on 23 January 1943 indicates an insecure feeling about the unknown outcome of imprisonment and the fear and misery of living in such a condition.

~ああ・羅針盤を失った船のやうに・西へ東へと・落ち行く運命・風に吹かれ・雨に流れど・その足跡は化石のやうに・おお神よ・忘れ給うなこの足跡を (Densho, Citationn.d.)

Like a ship lost the compass, to the West or to the East, we are to be ruined, as the wind blows to us and rain falls to us, our footprints [… are] like a fossil, oh gods, please do not forget our footprints.

Furthermore, in the haiku below, which was contributed to the Granada Bungei on 9 January 1943, the landscape is called a ‘wasteland’, contrasting the previous phrase of ‘the first sunrise on New Year’s’. Because the New Year is the most important holiday in Japan, similar to the Western Christmas, juxtaposing ‘New Year’ and ‘wasteland’ indicates their hopeless circumstance.

幾山河越えて荒野の初日の出. (Densho, Citationn.d.)

Crossing over many mountains and rivers, finding the first sunrise on New Year’s in the wasteland.

The detainees’ sense of nostalgia intensified in the midst of disappointment and fear. The poem below, which was contributed to the Granada Bungei on 30 December 1943, is about a person’s thoughts about Japan and his or her family there.

故郷の老ひたる母の偲ばれて夜更けの原にひとり覚め居り. (Densho, Citationn.d.)

Thinking of old mom left in [my] hometown, I woke up in the late [… of] night and stayed alone in the dark field.

Furthermore, at the Amache camp, the detainees worked together to improve the surrounding landscape by lining the streets with trees and growing plants near their barracks. A primary purpose of altering the landscape in Amache was to alleviate the feelings of detainee discomfort. Elementary schoolchildren also participated in the development and implementation of landscaping plans in collaboration with adults (Clark Citation2020; Suto and Voeks Citation2021). At the site, planting trees was perhaps the single most impactful modification to the camp, and we can see Siberian Elms (Ulmus pumila) mainly along the barracks and road in this photograph taken in 1942, as shown in .

Figure 14. Aerial of the Amache incarceration camp with trees planted by detainees. Many of these were Siberian Elms (Ulmus pumila) known for quick growth. Courtesy, ‘Granada (Amache) concentration camp, Colorado’ ddr-densho-157–107. Densho, the Wada and Homma Family Collection.

Some of those trees were purchased from a nursery, and some were transplanted native cottonwoods relocated from along the Arkansas River (Clark Citation2020). Tree planting seems to vary by individual or block, as the number of trees varies in public spaces and landscape schemes.

It is unclear when the first trees were planted at Amache; however, the poem below, which was contributed to the Granada Bungei on 9 January 1943, refers to rows of trees.

線条網の外はサボテンの上で夕日が射している。見馴れたキャンプを雪景となり並木のつら(ら). (Densho, Citationn.d.)

The evening sun is shining upon the Cacti outside of the braided wire mesh. The familiar camp view is now covered with snow and icicles on rows of trees.

Moreover this poem implies that landscaping, including planting trees in the camp, was well underway by January 1943; therefore, building Japanese-style gardens could also have started by then. The poems above reveal the detainees’ state of mind when they Japanese-style gardens in the Amache camp. For Japanese detainees, planting trees and building Japanese-style gardens were not only a way to improve their physical condition, but also to compensate for their feelings of loss. The extent of the effect of altering the landscape could be read from the poem above, that is, shifting the expression ‘wasteland’ to ‘familiar camp view’, which suggests that the detainee’s feelings towards the camp changed to something familiar. During this process of adapting their surroundings to a more familiar and soothing environment, the detainees found solace in the semblance of their everyday camp view. Such interludes may have caused detainees to miss more of their homeland’s scenery or something symbolising Japanese culture, resulting in Japanese-style gardens.

Evaluation of Amache Japanese-style gardens

To overcome the deep sadness, anxiety, and fear over the unknown outcome of their lives at the incarceration camp, Amache detainees organised schools, religious services, and cultural events to support themselves. They planted trees and created gardens to mitigate the effects of harsh climates. Among their creations, the two small Japanese-style gardens built in the public spaces of Blocks 6H and 12F had particularly diverse meanings and roles compared to other activities and projects at the camp.

However, before evaluating the effects of these creations, we need to review what elements of these gardens are ‘Japanese’. An important source for Japanese garden design is the Sakuteiki, the oldest known manuscript on the creation of such gardens. In the first chapter, Sakuteiki describes the fundamental ideas underlying Japanese gardens as follows:

Visualize the famous landscapes of our country and come to understand their most interesting points. Re-create the essence of those scenes in the garden, but do so interpretatively, not strictly.

It also reads:

Select several places within the property according to the shape of the land and the ponds and create a subtle atmosphere reflecting again and again on one’s memories of wild nature.

In short, Sakuteiki describes Japanese garden design as symbolising the beauty of the surrounding nature to evoke emotions. To symbolise the beauty of nature, Japanese gardens miniaturise natural elements such as mountains and rivers in their limited space. With such miniaturised elements, Japanese gardens have become contemplative places where individuals can enter into dialogue with nature (Goto Citation2003; Tagsold Citation2017). Regarding the form of the garden, among many ways to classify its styles, Japanese gardens are divided into two primary types based on the landform of the garden: a flat garden (hiraniwa) and a hill and pond garden (tsukiyama) (Keane Citation1996). While flat gardens do not incorporate natural water features, hill and pond gardens involve the creation of artificial mounds using the soil excavated during pond construction. Even if it is a small pond, as Sakuteiki describes, the scenery should represent ‘memories of wild nature’ so that these mounds and the pond represent mountains and the ocean respectively.

Although the 6H garden is small, it is a hill- and pond-style garden. Here, instead of ‘re-creating surrounding nature’, that is, the desert landscape, the detainees created a pond and a mountain, designing a landscape that mirrored the landscape of Japan. The 1.5 m high mound, the pond built with concrete rubble, and the small pine saplings in the 6H garden obviously represent Japanese landscapes, surrounded by lush mountains and the ocean with white sand beach and green pine forest, the ‘home country’ landscape from the memories of the Issei. The vertical stone on the small island could suggest a crane island, a symbol of longevity, stretching its long neck towards the sky. On the other hand, although minimal, the 12F garden has designed a feature that reminds us of a waterfall or stream. It recreates the natural splash and amplifies the sound of water, like Murin-an, which designed a running stream in an open field (Goto Citation2005).

Although the size and materials are limited, the 6H and 12F gardens of Amache were recreating the detainees’ memories of the Japanese landscape in a symbolic way; thus, we can call them Japanese-style gardens. Because the image of the landscape is abstract and miniaturised, despite the small size and lack of traditional materials, the Japanese-style gardens in Amache could still convey the ideas of the Japanese landscape and culture, as well as evoke a sense of peace and spiritual connection.

In the camp, detainees who were knowledgeable about Japanese culture, typically elders, played a role in organising club activities involving kabuki and haiku, creating new bonds through such educational and cultural activities (Clark Citation2020). The construction of Japanese-style gardens was one such activity, but these gardens had greater meaning. Unlike other club activities, which were temporary or held primarily for members, these Japanese-style gardens were permanent and built in public spaces. They were appreciated by many people, not only club members but also neighbours and friends passing through these areas. Together they experienced this traumatic situation and together they moved through public spaces that celebrated their traditions. In other words, the Japanese-style garden became not only an opportunity to learn garden design and construction techniques but also a space for all detainees to gather, learn, communicate, and take pride in their Japanese identity ().

Conclusion

At Amache, the construction of Japanese-style gardens in a public space was typically undertaken by groups, likely with guidance from people with experience in Japanese garden construction. Notably, the detainees gathered and cooperated to construct a common space in Japanese style, as noted in the hand-written inscription shown in which reads, ‘My father Mr. Hauichi Yoshida and many other men, women, and children all helped to make this pond in our block, 6H’.

In Block 6H, seven residents besides Toichi Domoto had previously worked in gardening, that is, they had operated nurseries, were floriculturists, yard workers, gardeners, or groundskeepers, or had worked in parks, cemeteries, etc. These people could call for work collaboration not limited to just their barrack residents but all camp residents through the Granada Pioneer (“Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection”., Citationn.d.). As the gardens were built in public spaces, their construction and maintenance became an educational opportunity for people who lacked formal knowledge of Japanese gardening traditions.

Brown (Citation1999, p. 13) suggests that for many Issei, building gardens served not only as a way of defining their Japanese-ness and maintaining ties to the homeland left behind but also as a means of securing a living and even assimilating into their new country. Nisei (second generation immigrants) were born in the U.S. (some in the incarceration camps) but even among the Issei, many immigrated at a young age and did not know much about Japanese culture. Ironically, incarceration in the camp became an opportunity for people with limited exposure to traditional Japanese culture to learn more about their shared heritage (Skiles and Bonnie Citation2010). Because the 6H and 12F were situated in shared spaces in the community, these gardens increased their significance each time detainees interacted with them. They were evidence of how Amacheans maintained their identity and culture, and gave new generations the chance to inherit traditions and cultures despite such atrocious experiences.

Extensive research has delved deeply into wartime trauma, including World War II, shedding light on its various dimensions and effects across cultures and ethnicities (Barclay Citation2021; Hashimoto Citation2015; Ohnuki-Tierney Citation2002). War experiences vary significantly based on factors such as individual’s age at the time, location, and their involvement in wartime activities. These varied experiences collectively contribute to feelings which engender a profound sense of powerlessness, particularly in a defeated situation. Moreover, the lasting effects of wartime trauma extend beyond the immediate survivors to family members who were either too young to remember the war or did not experience it firsthand (Hashimoto Citation2015). Throughout history, numerous minority ethnic groups have endured persecution and forced relocation, resulting in their assembly in concentrated areas. Despite being unfamiliar with one another, the shared cultural and linguistic heritage of these groups plays a unifying role (Casella Citation2007). For example, Native American reservations came about because of colonisation, but are also locations of vital indigenous cultures and traditions. Lucero (Citation2010) also suggests that for Indigenous individuals living in urban areas, experiences and connections with other native people during young adulthood influenced how they established their native identity. In this context, individuals develop a sense of collective identity that builds on the resources of their tangible and intangible cultural heritage. During World War II, Japanese Americans were forced to reside in incarceration camps, and their cultural practices and traditions followed a similar trajectory. Amacheans created Japanese gardens to not only cope with an oppressive landscape but also trauma, and through Japanese gardens, they evolved intimate connections, emotional bonds, and an understanding of their own culture across generations.

The Amache incarceration camp was officially closed on 27 January 1946. Many evacuees returned to California, but nearly 2,000 remained in Colorado. Ironically, after the war, Japanese gardens became popular on the West Coast among Americans who were introduced to Japanese culture during the war. The construction of these Japanese-style gardens was fuelled by the efforts of Japanese Americans who returned from the incarceration camp and sought to reconnect with their cultural heritage (Clark and Shew Citation2021). Consequently, numerous public and private Japanese-style gardens were built on the West Coast, and the number of LSCJG members rose to over 6,000 members in 1950 (Minami Kashū Nihonjin shichijūnenshi Kanko Iinkai, Citation1960). Gardener’s Monthly was republished in June 1956, and issues contained more articles about Japanese gardens, which suggests a rising trend of Japanese gardens in the U.S. It is difficult to track all the detainees after the war; however, detainees from Amache, who either learned about or learned more about Japanese gardens in the camp, were likely involved in the construction of new Japanese-style gardens after World War II. Minoru Tonai, a leader in the preservation efforts at Amache, recounted to co-author Clark that his father built a Japanese-style garden at the Compton Japanese school (in a neighbourhood in LA) just prior to the war. After returning to the area in 1946, his family was able to buy a house on a hillside and there his father built a Japanese-style garden with a waterfall and pond (Tonai Citation2020).

Japanese-style gardens in Amache were humbly constructed using limited materials. Nevertheless, we could say that these gardens were possibly some of the most influential Japanese-style gardens in North America during World War II, as they brought detainees together, healed them, and provided them with the knowledge and courage to express their cultural identity in the U.S. Now these Japanese-style gardens remain as a memorial legacy for future generations.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Jim Casey for providing 3D models of the current condition of Amache, which significantly improved the modelling and analysis of the manuscript. This study greatly benefited from the expertise and assistance of Shinkichi Koyama at the Southern California Gardener’s Federation and the archivist Jamie Henricks at Japanese American National Museum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sayaka Akayama

Sayaka Akayama is a doctoral student at the School of Environmental Science, Nagasaki University. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in environmental science from Nagasaki University as well as a master’s degree in landscape architecture from University of Oregon.

Bonnie Clark

Bonnie J. Clark is committed to using tangible history to broaden understanding of our diverse past. She began her career as a professional archaeologist and now serves as a Professor in the Anthropology Department at the University of Denver (DU), as well as the Curator for Archaeology of the DU Museum of Anthropology.

Katsunori Furuya

Katsunori Furuya is a Professor at the Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University, Japan, where his teaching covers Landscape planning. He has also published extensively on the subject.

Yusuke Mizuuchi

Yusuke Mizuuchi, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at the University of Tokyo Forests, Japan. His current research interests include scenic landscape assessment and landscape planning.

Ryo Nishisaka

Ryo Nishisaka, Ph.D., is a Lecturer at the Faculty of Global and Regional Studies, University of the Ryukyus, Japan, where her teaching covers tourism resources management by landscape planning and qualitative analysis.

Seiko Goto

Seiko Goto is a Professor at the School of Environmental Science, Nagasaki University, Japan, where her teaching covers Japanese gardens. She has also published extensively on the subject. She is an academic expert in Japanese garden history and the healing effects of its design.

References

- Barclay, P. D. 2021. “Imperial Japan’s Forever War, 1895-1945.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 19 (18): 5635. https://apjjf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/article-561.pdf.

- Brown, K. H. 1999. Japanese-Style Gardens of the Pacific West Coast. New York: Rizzoli.

- Brown, K. H. 2020. Visionary Landscapes Japanese Garden Design in North America, the Work of Five Contemporary Masters. Vermont: Tuttle Publishing.

- Burton, J. F., and M. M. Farrell. 2014. A Place of Beauty and Serenity Excavation and Restoration of the Arai Family Fish Pond Block 33, Barracks 4. Independence: Manzanar National Historic Site California.

- Burton, J. F., M. M. Farrell, F. B. Lord, R. W. Lord, E. Roosevelt, R. J. Beckwith, and J. C. Irene. 2002. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. University of Washington Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnv2x.

- Camp, S. L. 2016. “Landscapes of Japanese American Internment.” Historical Archaeology 50 (1): 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03377183.

- Casella, E. C. 2007. The Archaeology of Institutional Confinement, the American Experience in Archaeological Perspective.

- Chiang, C. Y. 2019. Nature Behind Barbed Wire: An Environmental History of the Japanese American Incarceration.

- Clark, B. J. 2020. Finding Solace in the Soil: An Archaeology of Gardens and Gardeners at Amache. Denver: University Press of Colorado.

- Clark, B. J., and D. O. Shew. 2021. “From the Inside Out: Thinking Through the Archaeology of Japanese American Confinement.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 25 (3): 803–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-020-00576-2.

- “Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection.” n.d. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/.

- Densho. n.d. Ddr-Densho-147-29 — Granada Pioneer Vol. I No. 28 (January 23, 1943) | Densho Digital Repository. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-147-29/?format=doc.

- Eggleston, E. C. 2012. How Japanese American Gardeners Shaped an Internment Camp Landscape: A Soil Chemistry and Archival Analysis. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Esaki, B. 2013. “Multidimensional Silence, Spirituality, and the Japanese American Art of Gardening.” The Johns Hopkins University Press 16 (3): 235–265. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2013.0026.

- Garrison, D. H. 2015. A History of Transplants: A Study of Entryway Gardens at Amache.Pdf.

- Gebhard, J. P. S. 2015. “Community Identity in “The Granada Pioneer”.” Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 234. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/234.

- Goto, S. 2003. The Japanese Garden: Gateway to the Human Spirit (Asian Thought and Culture). New York: Peter Lang Inc. International Academic Publishers.

- Goto, S. 2005. “The Confrontation with Western Culture: A New Garden Style in Kyoto — Murin-An.” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 25 (3): 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2005.10435443.

- Guest, G. 2020. “Plants and Immigration: The Domoto Legacy.” GardenRant. August 12, 2020. https://gardenrant.com/2020/08/the-domoto-legacy-plants-and-immigration.html.

- Hashimoto, A. 2015. The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Japan.

- Helpland, K. I. 2006. Defiant Gardens Making Gardens in Wartime. San Antonio: Trinity University Press.

- Ichioka, Y. 1988. The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese Immigrants, 1885-1924. New York: Free Press: Collier Macmillan Publishers.

- Keane, M. P. 1996. Japanese Garden Design. Vermont: Turtle Publishing.

- Library of Congress. n.d. “The U.S. Mainland: Growth and Resistance.” Washington, D.C. 20540 USA: Library of Congress. Accessed November 22, 2022.

- Lucero, N. M. 2010. “Making Meaning of Urban American Indian Identity: A Multistage Integrative Process.” Social Work 55 (4): 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/55.4.327.

- Minami Kashū Nihonjin shichijūnenshi Kanko Iinkai. 1960. Minami Kashū Nihonjin Shichijūnenshi. Los Angeles: Japanese Chamber of Commerce of Southern California.

- Naomi Hirahara, ed. 2000. Green Makers: Japanese American Gardeners in Southern California. Los Angeles: Southern California Gardeners’ Federation.

- NARA (National Archives and Records Administration). 1900–1953. Washington, D.C.; Series Title: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Honolulu, Hawaii, Compiled 02/13/1900 - 12/30/1953; NAI Number: A3422; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 - 2004; Record Group Number: RG 85. College Park: Department of Justice. Civil Rights Division.

- Ng, L. W. 2014. “Altered Lives, Altered Environments: Creating Home at Manzanar Relocation Center, 1942-1945.” University of Massachusetts Boston 279. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses/279.

- NPS (National Park Service). 2024. “Foundation Document, Amache National Historic Site, Colorado.” https://parkplanning.nps.gov/document.cfm?parkID=73&projectID=114923&documentID=134935.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, E. 2002. Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ozawa, K. 2016. The Archaeology of Gardens in Japanese American Incarceration Camps. San Francisco: San Francisco State University.

- Ozawa, K. 2020. “Sifting Through Multiple Layers of Violence: The Archaeology of Gardens at a WWII Japanese American Incarceration.” In Archaeologies of Violence and Privilege, edited by C. N. Matthews and B. D. Phillippi, 133–153. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Rogers, A. 2024. Amache 2022 Field Season – Diatom Analysis. Report prepared for the DU Amache Project. Manuscript in possession of Bonnie Clark.

- Skiles, S., and J. C. Bonnie. 2010. “When the Foreign Is Not Exotic: Ceramics at Colorado’s WWII Japanese Internment Camp.” In Trade and Exchange: Archaeological Studies from History and Prehistory, edited by C. Dillian and C. White, 179–192. New York: Springer Press.

- Suto, A., and R. Voeks. 2021. “Uprooted: Gardening and Landscaping During the Japanese-American Internment.” California Geographer 60:73–94.

- Tagsold, C. 2017. Spaces in Translation: Japanese Gardens and the West. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Takei, J., and M. P. Keane. 2008. Sakuteiki: Visions of the Japanese Garden: A Modern Translation of Japan’s Gardening Classic. Vermont: Tuttle Publishing.

- Tamura, A. H. 2004. “Gardens Below the Watchtower: Gardens and Meaning in World War II Japanese American Incarceration Camps.” Landscape Journal 23 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.23.1.1.

- Tonai, M. 2020. “Email with Bonnie Clark About His father’s Gardening Experience.” Manuscript in Possession of Bonnie Clark.