ABSTRACT

Despite much attention to physical aspects of climate change, the relationship between climate change and culture has thus far received little attention in research. Cultures develop over time and are shaped by place-specific factors such as history, landscape, weather, flora and fauna. Climate change affects these contextual factors, and as such will have consequences for the cultures shaped by them. In addressing the intersection of culture and climate change, the paper draws on a qualitative study on Fanø, a low-lying Danish island in the Wadden Sea. We illustrate how the cultural heritage of Fanø’s seafaring past plays an important role in the everyday culture of the present. The cultural heritage and the nature of Fanø are at the core of the island’s identity. As climate change will affect the community’s ability to maintain their cultural heritage and will change the island’s natural values, it will affect what it means to be Fanniker.

Introduction

Many heritage sites across the world are at risk of damage due to the vulnerability of materials to a variety of climate change consequences, such as flooding, temperature changes and humidity changes (Carmichael et al. Citation2020; Riesto et al. Citation2022). There is a need for developing alternative management strategies to respond to the effects of climate change on heritage (Harvey and Perry Citation2015; Krauβ Citation2015; Riesto et al. Citation2022). Such sites, including historical monuments, archaeological sites and cultural landscapes, are an important part of community identity and cohesion in the present. They are often a basis for cultural activities (Carmichael et al. Citation2020) and serve to maintain cultural identity for future generations (Ashworth and Graham Citation2005). However, cultural consequences of climate change reach further than the effects on built heritage (Munshi et al. Citation2020; Richardson Citation2015; Riesto et al. Citation2022). Values and traditions that are rooted in place affect the way climate change may be felt by inhabitants of that place, for example, through experiencing changes to their way of life, food security, and even a loss of identity (Munshi et al. Citation2020). But as long as the effects of climate change on culture and heritage are not well understood, people cannot prepare to respond to these effects. In order to develop place-based and culturally appropriate adaptation policies, there first needs to be an understanding of what climate change means for culture (Kim Citation2011; Munshi et al. Citation2020).

This paper explores how climate change effects intersect with culture and heritage, both tangible and intangible. It contributes to an improved understanding of what climate change effects and adaptation could mean for culture and heritage, which we regard as the first step in preparing for cultural consequences of climate change. The paper is based on empirical research on Fanø, one of the Danish Wadden Islands, known for its seafaring heritage and its nature–culture interaction. We will first discuss the intersection of culture, place and climate change, which forms the basis of the empirical research. We then explain the research approach and provide background on the study location. This will be followed by a discussion of the research findings and their implications, focusing on the significance and strength of historic houses, the (social) value of cultural festivals and related practices, and finally the role of the island’s nature in cultural identity and the accompanying cultural resilience.

Culture, place & heritage

The working definition of culture in this article is that it encompasses objects and symbols and their ascribed meanings, as well as the norms, values and beliefs, which set the cultural boundaries recognised and constructed by a community (Reeves-Ellington and Yammarino Citation2010). This definition is purposefully broad, because it allows for contextual factors, and it leaves room for community members to determine what is and is not their culture. We use the concept of community here primarily in the sense of a shared geographical location, with the understanding that it may not be a homogenous group and community members are individuals with their own characteristics and opinions (Titz, Cannon, and Krüger Citation2018). In any place, multiple cultures may exist, and an individual may identify with several cultures. Cultures develop through contextual factors of place and time, such as history, geography, weather, flora and fauna, and cultural heritage. Considering the influence these factors have on cultures and vice versa, it is expected that changes to these factors will lead to changes to cultures (Modeen and Biggs Citation2020).

Through these contextual factors, cultures become nestled into a particular place, and it is this spatial dimension of culture that is at the core of this research. Place is here understood following Low (Citation2017, 32) who defined it as ‘the sense of a space that is inhabited and appropriated through the attribution of personal and group meanings, feelings, sensory perceptions and understandings’. Through culture, meaning is ascribed to place, and people’s experiences with that place, with language, cultural artefacts, and practices (Modeen and Biggs Citation2020; Richardson Citation2015). Places offer a location for everyday activities, as well as social life, and are therefore intertwined with how community members relate to each other and their surroundings (Low Citation2017; Tilley Citation2006). While place is shaped by the meanings ascribed to it, it is also dependent on the physical aspects of the landscape which facilitate certain cultural activities. As such, the place is intertwined with how people identify themselves and their cultures (Low Citation2017; Modeen and Biggs Citation2020; Tilley Citation2006).

Through interaction between a community and a place, cultural or place identities are created. An important part of the process of identification with a place is the creation of material and immaterial references to the past either through traditional activities or heritage sites (Modeen and Biggs Citation2020; Tilley Citation2006). Community activities can create a link to the past and support a sense of belonging by providing a space in which community-members can express themselves to themselves and others (Tilley Citation2006). The landscape where this takes place, created through both natural and cultural processes, is also part of the identification process (Antrop Citation2005; Tilley Citation2006).

Ashworth and Graham (Citation2005, 7) state: ‘heritage is that part of the past which we select in the present for contemporary purposes, whether they be economic or cultural (including political and social factors) and choose to bequeath to a future’ (emphasis added). Heritage links a community’s past, present and future in place and serves to continuously reinforce cultural identities. But, it is also a resource frequently used to promote tourism and economic development, which affects the meanings ascribed to it (Egberts and Hundstad Citation2019). Heritage is a dynamic expression of societal values, and not solely a selection of the best of the past (Abranches and Horton Citation2024; Harvey and Perry Citation2015). Heritage is political and therefore biased. Some parts of history are highlighted, in support of a particular place identity, but they are also contested (Ashworth and Graham Citation2005; Krauβ Citation2015; Lewicka Citation2008; Lowenthal Citation2005; Richardson Citation2015).

While heritage discussions have often revolved around perpetuity, the idea that heritage has to remain as it is is being challenged more and more (Abranches and Horton Citation2024; Harvey and Perry Citation2015; Riesto et al. Citation2022). Harvey and Perry (Citation2015) argue for the recognition of the way our climatic heritage shapes the Anthropocene to support a different perspective on climate change. This does not mean supporting a narrative only focused on threats and potential losses, but acknowledging that change will come (Harvey and Perry Citation2015; Krauβ Citation2015). In this article, we do not intend to advocate that all will be lost or that all heritage must be preserved but to improve understanding of the relation between climate change and cultural practices and heritage so that people can make informed choices about the future of their heritage. Because as Harvey and Perry (Citation2015), Dawson (Citation2015), and DeSilvey and Harrison (Citation2020) illustrate, there are different possible ways of responding to heritage under threat, such as mitigation, adaptation or what DeSilvey (Citation2017) calls ‘palliative curation’.

The palliative curation or managed retreat approach accepts the inevitability that some heritage will be lost, especially in the context of accelerated climate change. It normalises that loss and change are part of heritage while acknowledging that there are different ways of dealing with loss (DeSilvey Citation2017; DeSilvey and Harrison Citation2020; Harvey and Perry Citation2015). While the process of dealing with loss is still new in heritage practice, engaging with the possibility of loss rather than avoiding it can be a meaningful and positive process for affected communities. Through the loss of heritage, new meanings and relations may emerge (Bartolini and DeSilvey Citation2020; Dawson Citation2015; DeSilvey Citation2017; DeSilvey and Harrison Citation2020). Palliative curation is not a passive approach of not preventing loss, but about transforming the relationship to heritage and active decision-making in how to deal with loss (DeSilvey Citation2017).

Decisions made today determine the future of heritage, but they can only be informed decisions if there is an understanding of what to expect and what is considered desirable (Harvey and Perry Citation2015). By taking a closer look at the intersection of heritage and climate, now and in the past, we can gain new insight into the challenges posed by climate change (Krauβ Citation2015). It can also open up opportunities for local people to engage more with their heritage and become involved in heritage management and decision-making on how to cope with changes and loss (Bartolini and DeSilvey Citation2020; Dawson Citation2015; Harvey and Perry Citation2015).

Methodology

Methods

This paper is based on a qualitative case study on the Danish Wadden Island Fanø. By focusing on a specific case study, it is possible to explore the context-specific intersections of culture(s) and climate change and gain an improved understanding of how ways of life will be affected by climate change at a local scale.

The data were collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2020). Because both climate change and culture tend to remain abstract topics, the interviews were supported by visual aids as an elicitation technique to stimulate the conversation. This made it easier for participants to imagine what climate change could mean for their life and cultures in the future (Fenech et al. Citation2017; Prosser and Loxley Citation2008). To prevent undue influence on the interview answers, the participants were first asked to reflect on the topic without the use of visual aids.

The elicitation took the form of news article clippings on incidents near Fanø that were reported to be climate change related, such as storm surges, biodiversity changes due to rising (water) temperatures, and 200 dead seabirds that washed ashore on Fanø in February 2022 linked to storms and a lack of nutrition (Skriver Citation2022a). Participants were asked to reflect on what the cultural consequences would be if these climate change-related incidents became more frequent. In addition, photographs of Fanø’s cultural practices and nature from the book ‘Fanø Mosaik’ (Lauridsen and Halberg Citation2013) were used, and participants were asked to bring items with an island link to further enable the conversation.

In total, 14 people participated in the research, 8 individually, and a group of 7, 1 participant was interviewed individually as well as in the group. All interviews were conducted in English. The interviews were recorded and transcribed and consequently coded inductively and analysed using Atlas.ti.

Participants

Potential participants were identified through websites of local heritage organisations, as well as a list of community organisations on the municipality website. In addition, local Facebook groups were used to recruit participants. Finally, the snowball method was used as various people were asked for suggestions and to spread information about the research (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2020).

All research participants were permanent residents aged 25 to 75. Of the 14 participants, 9 were women, and 5 were men. While most participants were not born on the island, many had long histories on the island and owned holiday homes before relocating to the island permanently. All participants felt a strong place attachment to Fanø, developed through time spent on the island and intense community experiences (see Shaykh-Baygloo Citation2020). All participants were given the choice between the use of a pseudonym or their first name in this article. All participants consented to the use of their first names.

Study location

Fanø is one of the Danish islands in the Wadden Sea. The Wadden Sea region comprises an interesting case study because of the interconnectedness of both natural and cultural processes that have shaped the landscape (Bazelmans et al. Citation2012; Blichfeldt and Liburd Citation2021). The landscape has been shaped by physical, geographical, natural and cultural processes, including dyke building, land reclamation and drainage activities, as well as periodic flooding going back a thousand years (Bazelmans et al. Citation2012; Reise et al. Citation2010; Schepers et al. Citation2021).

Climate change effects in the Wadden Sea are increases in mean temperature and precipitation, as well as longer heatwaves. Higher water temperatures are expected to have a large impact on the biodiversity of the Wadden Sea (Fanø Municipality Citation2023; Fruergaard et al. Citation2019; Oost et al. Citation2017). Due to sedimentation, the island has prograded approximately 1 km westward over the past 500 years and continues to do so. As a result, Fanø is currently not considered at risk of erosion due to sea-level rise (Fruergaard et al. Citation2019; Vollmer et al. Citation2001). The municipality strives to balance Fanø’s natural and cultural values while preparing for climate change mitigation and adaptation to protect the island’s special characteristics (Fanø Municipality Citation2023). This goal underlines the need for an improved understanding of the effects of climate change on culture and heritage to inform the municipality’s decision-making.

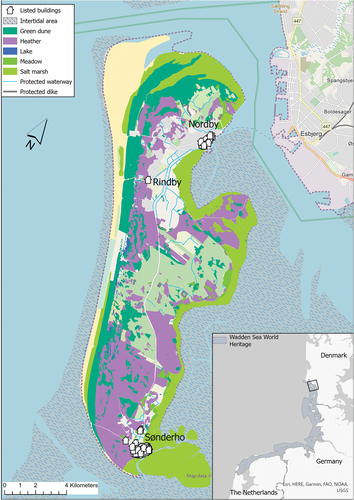

As illustrated by the map in , Fanø has several landscape types. In addition to municipal and national regulations, the island, with the exception of the three towns, falls under the protection of Natura 2000 and the Ramsar Convention (Blichfeldt and Liburd Citation2021; Reise et al. Citation2010). The island consists of natural dune systems with forest plantations in the middle of the island, dyked polders surrounding the villages in the north and south, undyked salt marshes on the east, a wide sandy beach on the west coast, and sand and green dunes.

Figure 1. Map of Fanø, including the various landscape types and monumental buildings. (data source: https://webkort.fanoe.dk/spatialmap. Last accessed September 7, 2023).

Before the eighteenth century, the main livelihoods on the island were agriculture and fishery (Vollmer et al. Citation2001). In 1741, Fanø citizens gained independence from the crown, which allowed them to profit from seafaring and shipbuilding on the island. This led to the expansion and prosperity in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, during which the towns of Nordby and Sønderho developed a distinct maritime character (Krageskov Citation2005; Vollmer et al. Citation2001). Through the seafaring industry Fanø developed international relations. This connectedness influenced the island’s identity and cultural practices, as will be illustrated in the findings. At the end of thenineteenth century, the first tourists arrived, attracted by the sandy beach. This led to the development of seaside resorts and a growth of the island population. Today, Fanø is primarily a tourism economy (Krageskov Citation2005; Vollmer et al. Citation2001).

Fanø is an independent municipality with three towns: Nordby, Sønderho, and Rindby (Krageskov Citation2005). Fanø has 3427 permanent residents (Statistics Denmark Citation2022). The island is well connected to the mainland via a ferry between Nordby and Esbjerg. Fanø was selected because it is known for both its natural and cultural values. Fanø has a vibrant cultural life and inhabitants who take pride in the island’s history and traditions (Krageskov Citation2005; Visit Fanø Citation2023; Vollmer et al. Citation2001).

Many of the old houses are well maintained by their owners and protected by legislation on monumental buildings (Vollmer et al. Citation2001). The heritage is celebrated in yearly festivals ‘Sønderho Day’ and ‘Fanniker Days’. During these festivals, all traditions are combined to celebrate the past and maintain the cultural identity of Fanø.

Living heritage

Sønderho Day has been organised every year in July since 1928 by the Foundation for Old Sønderho (Danish: Fonden Gamle Sønderho). The day consists of a bridal procession and a performance of the ‘Sønderhoning’, a traditional couple’s dance. During the event, people wear traditional folk costumes, which can be leased from the foundation (Fonden Gamle Sønderho (Citationn.d.)).

The Fanniker Days originated in 1953 as a way to revive cultural traditions, at a time when only a few women still wore traditional clothing (Fannikerdagen Citationn.d.-a). The festival is organised for three days in July in Nordby. Fanniker Days consist of a wide variety of activities including local foods, fiddle-music, dance performances, workshops, children’s games and sea-shanties. People perform a traditional returning of the sailors and a wedding procession through town. Any profits from the Fanniker Days festival go to Fanø’s museum of sailor heritage and folk-costumes, which educates visitors on local history (Fannikerdagen Citationn.d.-b). The cultural festivals also attract tourists, who are an important source of income for the island, which supports the work of the cultural heritage institutes (Fanø Municipality Citation2019; Krageskov Citation2005).

Results and discussion

Heritage & climate change

When asked to describe the identity of Fanø, two aspects were mentioned by every participant: the seafaring history which shaped the community and its’ culture and the island being ‘full of nature’ (Malene, 27). As Mille (35) noted: ‘The island has these traditions, it’s very much become part of the identity that you keep these traditions’. Malene (27) suggested that the international contacts of the seafaring past have led to the welcoming character of the community today: ‘Because of it being an old sailor society, people have been used to having visitors from everywhere in the world. And that’s what I feel. People are still very good at just being open to whatever comes’. According to Egberts and Hundstad (Citation2019), the image of an open and welcoming community, because of a history of intercultural connections, is found frequently in coastal areas, and is often used to promote tourism. For Malene (27), who moved to Fanø three years ago, the welcoming character of the community has facilitated the move. This is one example of how the seafaring past is integrated into the narrative around the present-day cultural identity.

The participants were asked what their expectations and concerns were, in general, about climate change on Fanø. While all participants share sea-level rise as the main concern, there was variation in other associations with climate change. A number of participants initially associated climate change with problems in other parts of the world. For example, Frank (45, mayor of Fanø), expressed concern for low-income countries who are facing the most severe climate change effects, as well as how for the world can facilitate future climate refugees. Others, like Tom (65+) and Mille (35), associate climate change with a responsibility to live in a more sustainable way. All participants found it challenging to state what the expected climate change impacts on Fanø are, let alone envisioning what the consequences for heritage and culture could be. Other places in the world can be considered more at risk, and it was interesting to see participants acknowledging a western responsibility in globalised climate change. However, the difficulty in identifying local risks does indicate a limited awareness of localised climate change effects.

While Henning (65+) associates climate change with storms and flooding, he has little concern for Fanø since the last flood that reached inside the towns was in 1981, after which the dikes were built. Malene (27) worries less about the floods themselves, but more about the effect that extending and heightening the dikes as a mitigation measure, will have for the nature and landscape of the island. She also wonders if completely blocking out the water could affect the community’s connection to the water and their understanding of the tides. This could affect their cultural identity as islanders, which is continuously reinforced by the seascape (see Modeen and Biggs Citation2020). Although respondents did not immediately introduce cultural or heritage aspects, with the exception of Malene who mentions the connectedness to land and water, during the conversations, various experiences emerged.

In the following, we will discuss these in more detail, focusing on three key aspects that emerged from our data analysis, namely: built heritage, living heritage, and natural heritage; and their connection to climate change. It is important to understand that these aspects have been analytically separated for clarity, but are in fact interconnected, and change to one aspect, affects the others.

Built heritage

Many respondents agree that the built heritage on Fanø is an important part of what keeps the history of the island visible and alive. The town centres have ‘a rich history in the museums and the houses (…) from the seventeenth or eighteenth century (…) which are very beautiful and very well maintained’ (Frank, 45). Else-Marie (65+) called Sønderho a ‘fairy tale city’. The buildings serve as a representation of the seafaring past, and support the preservation of Fanø’s cultural identity. Frank explained the cultural significance by stating that the historic town centres date back to Fanø’s seafaring age. In addition, the design of the roofs and tile decorations were inspired by what the sailors saw in cities such as Amsterdam. When asked about the potential consequences of climate change, Frank (45) expressed what a tremendous loss it would be if the houses were damaged as the result of climate change effects, particularly through flooding:

It takes away some of our culture, if these houses that we are so proud of cannot stand any longer what do we have to be proud of then? We don’t have the ships anymore so we only have it in pictures. But if we also lose the houses it’s another battle that we would lose.

The sense of pride that is gained from these historic houses and the sense of loss that would be felt should they be damaged indicates a high public value. According to Dawson (Citation2015), awareness of this value is the first step in protecting heritage. It is also an important consideration in determining what loss would be (un)acceptable (see Harvey and Perry Citation2015). However, because the historic houses on Fanø are considered well-maintained and strong, all participants deemed it unlikely that climate change would have a significant effect. The strength of the houses can be ascribed to the way they were built, which was, as Henning (65+) and Malene (27) explain, with storms in mind:

The houses are placed in an east to west direction, so that it follows the wind. Because if they were placed north south, the wind would hit it directly on the longer side. So they have placed that east-west to let the winds go around the house. And then in the western side of the house, they placed the animals (…) in the windy side. The people lived towards the east of the house, so they were protected from the wind.

In a way, these houses were originally climate-adapted buildings, newer buildings were not necessarily built with the same consideration for weather patterns. Furthermore, the participants repeatedly mentioned that in 300 years, the houses have been flooded multiple times and have managed to outlive many newer buildings:

No, they will survive. Because you know, they have the dikes here in Nordby. And there was a really big storm in 1981 and high tide, so the water was in the towns and the houses are still there and I know that many of the old houses in Sønderho have been under water many times but they’re still there. (…) I’m absolutely sure they will be standing. Because when the storms are coming, damage to houses is more in the new houses. The old houses are very strong so I’m convinced they will be staying there.

Many of the participants expressed the hope that the community would maintain these houses in the future. Potential damage to new buildings does not appear to evoke the same sense of loss. However, structural adaptations to retain the old as living spaces (e.g. by adjusting the height of doors and ceilings) are prevented by heritage preservation policies. These preservation policies also pose a challenge for climate change mitigation on the island. In their climate action plan, the municipality notes that the possibilities for installation of solar panels on monumental buildings are limited, as are the options for improving energy efficiency (Fanø Municipality Citation2023). This example illustrates some conflicts around heritage and climate change that may also affect communities elsewhere. As Ashworth and Graham (Citation2005) discussed, heritage is about a choice a community makes in the present on what will be passed on to future generations. In the future, inhabitants of Fanø may have to make choices between strict preservation of its built heritage and adapting to changing circumstances to ensure sustainability and continued liveability.

Living heritage

Cultural festivals are the highlight of cultural life on Fanø and an important part of how inhabitants connect to the island and each other (see Low Citation2017). This is illustrated by Ragnhild (65+), who explains that the Fanniker Days festival ‘means a lot to us (the Fanø community), it connects us, it puts us together. Because we are very proud of it’. The festivals consist of many elements that all contribute to the cultural heritage and identity of Fanø. The re-enactment of the return of sailors and the traditional bridal procession showcase the past and reaffirm the identity of a seafaring community.

Several festival elements are part of Fanø life throughout the year, continuously supporting attachments between people and place (see Tilley Citation2006). Line (35) and Ragnhild (65+) noted that some women wear traditional clothing at events throughout the year, such as weddings, funerals, and cultural activities, as well as the occasional regular day. Seeing women in traditional dresses is a visual reminder of the past, similar to monumental buildings, but the meaning of the dress goes beyond this. As Ragnhild explains in the quote below, women work throughout the winter to create their own dresses. This creation becomes a social activity in itself, and supports the development of social attachments (see Shaykh-Baygloo Citation2020).

The best is of course to have your own. So it’s very popular to make your own costume during winter. So there are groups here in Nordby, and in Sønderho, where people meet, and they sow by hand. It has to be made by hand. And it takes a really long time. And it’s actually a quite expensive one, but it’s, I don’t know, it’s a very special feeling you have to put it on. (…) I think it’s nice because it makes us who we are now. Because of course we go with that dress on and we have our cell phones and et cetera, but it also reminds us about how it used to be and about how life was before. Especially the women on Fanø I think they were very strong, very independent, because during the sailing period, the men were on sea maybe for two years. And then it was a woman who was in charge of everything at home.

To illustrate intricacies of the folklore costume, in the interview Gitte (35) used the doll shown in . The strength of the women of Fanø’s past was mentioned repeatedly. As Ragnhild explained above, the sailors were away for most of the year, if not more, leaving the women to take care of everything at home. When women in the present choose to wear traditional dresses, it is in admiration of the strength of the women from that time. Wearing the costumes fills women with pride and allows them to embody the identity of the strong Fanø woman.

Another element of the cultural festivals that play an important social role throughout the year, is the traditional music and dance of Fanø. When describing Fanø culture, several participants mentioned weekly evenings where people play folk music and dance the Sønderhoning, a couple-dance: ‘Did anyone mention the rich music life? Especially (…) all the Fiddler’s or the folk music. It is very special folk music in especially Sønderho, but in both towns’ (Steen, 65+).

The fiddle music is another part of Fanø culture in which the international connections of the seafaring history are present. It was the sailors who brought the violins to the island, and ‘the music is (…) a mix; the men they went abroad and came home with a little mix from music from there and from there’ (Ragnhild, 65+). While over time it developed into a distinctive style, international influences illustrate the flexibility of Fanø culture, and perhaps the potential for adaptation to new circumstances.

The music evenings are open to anyone, young or old, long-term residents and newcomers. In addition, there are dance and fiddle courses available on the island. The active participation of the youth is considered very special by the participants:

One thing that is quite unique for Fanø in particular is that the folk music is also passed on to the youth. There’s quite a huge number of young people who fiddle and dance and are very passionate about it.

In other parts of Denmark the young pupils they don’t want to dance in this way, but here they do. Here it is cool. My eldest grandson, he says the best trick to get a hold of a girl is to dance.

By facilitating social interactions, these evenings contribute to community cohesion for all ages (see Low Citation2017; Shaykh-Baygloo Citation2020). It is an important goal of the municipality’s cultural policy that there is room for everyone, across generations, to participate in cultural activities and the associations that organise them. The associations are primarily run by older people, but the municipality recognises in its cultural policy that cultural heritage can only be passed on, if there is room for younger generations to contribute with their own characteristics (Fanø Municipality Citation2019).

The participants in our study do not expect climate change effects to affect these traditions of folk costumes, dancing, and music. However, we expect that storm surges, high-intensity rainfall, and extended heatwaves can threaten the outdoor festivities in which these elements come together. Still, these elements illustrate the flexibility that cultures can have and could perhaps support the community in coping with other changes. As Line (35) expressed in her hopes for the future: ‘The spirit will be here, and hopefully the music too’.

However, there is an interconnectedness between these practices, the festivals, cultural identity, but also tourism. The tradition of making folk costumes will only continue if there are activities where women can wear the costumes. The old costumes would remain on display in the museums, but the skill of making the dresses and the accompanying social interactions would be lost. In turn, it will affect the community’s ability to maintain the identity of the strong Fanø woman. Wanting to participate in the festivals motivates the youth to learn to play the fiddle and dance the Sønderhoning.

Both the cultural festivals and the many other festivals that Fanø hosts are primarily organised outside, which makes them dependent on weather conditions:

Once when there was this knitting festival in September, some years ago, it was completely full of water. So they were so stressed and had to move things around. And there is really thousands of people visiting the island during that knitting festival.

A storm surge in 2017 flooded the designated festival terrain, forcing the knitting festival inside (Fanø Municipality Citation2023). Moving inside is not considered an option for cultural festivals, especially for events such as bridal processions. Frank (45) noted that ‘it wouldn’t be the same, because it’s the ceremony, and the walk through town, it’s not just going to the party, it is the whole atmosphere around it’.

While details on the effect climate change will have on cultural festivals are not yet known, adapting them to changing circumstances would have an effect on the meaning and value these cultural celebrations have for the community. In turn, this would affect the community’s ability to maintain the identity of the sailor island. In addition, the cultural festivals attract many tourists each year. If the festivals would be cancelled because of extreme weather or floods, it could decrease tourism income, which would affect the community’s continued ability to organise the festivals.

Natural heritage

Almost all participants explicitly mentioned how much they value the variation in the landscape on Fanø, including the beach, marshland, heathland, mudflats (inhabited by seals), and hills. Nature is such an important part of life on the island that the municipal cultural policy considers nature as ‘a large part of the island’s identity’ (Fanø Municipality Citation2019).

This is further illustrated by the cup in that Malene (27) brought to the interview as a symbol for Fanø:

It’s the bird life on Fanø (…) and it symbolised the Wadden Sea, like the beach and the sea, and (…) all the space and the blue sky. (…) I was really like wow, I need this cup. Because this is essential to what we are here.

Figure 3. Coffee cup symbolizing Fanø. Created by Mette Hübschmann Pettit, after a design by her father.

The municipal cultural policy further states that ‘Fanø’s location in the Wadden Sea National Park and the inclusion of the Wadden Sea on UNESCO’s World Heritage List is an important element of the cultural heritage’ (Fanø Municipality Citation2019). Most of the participants mentioned that the combination of nature and culture is the reason they choose to live on Fanø. Ragnhild (65+) considers nature to be an important part of Fanø: ‘I think that to most of us, nature really means a lot. Maybe we do not use it every day. But it’s important it’s there. And that it’s taken care of’. In addition, Frank (45) noted how important the Wadden Sea is for a wide variety of wildlife.

Climate change is already having consequences for nature on (and around) the island, in particular, through the rising water temperatures which affects aquatic life. While there is no commercial fishery on the island, according to Henning (65+) and Frank (45) those who fish privately have shared with the community that the fish supply is declining. Both Frank (45) and Christina (35) remarked how important the Wadden Sea is for migratory birds who feed before travelling south or north or make their nests on the islands. The Danish Ornithological Society is concerned about the effect of rising water temperatures on the bird's food supply. It was linked to the dead birds that washed ashore on Fanø in February 2022, although it was later concluded that malnutrition made them susceptible to bird flu, which was the ultimate cause of death (Skriver Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

Considering the role of nature in the identity of Fanø, it can be expected that changes in nature would have a significant impact on the community. However, the participants found it very difficult to imagine what it would mean for the community if nature on the island changes or declines. Gitte (35) remarked ‘that’s a question, or will it just be a different picture of Fanø? I don’t know’. The general expectation was that the community would get used to changes:

I feel like the people in Fanø have always adapted to however the weather changes, because there is this big respect for that the nature is harsh here. And you should respect the tides and all that. So I don’t think that will change the community a lot, they will just adapt to the new way of living.

This sentiment was shared by the participants of the group interview, who expected that nature will change, without indicating how, but nature will not disappear. Furthermore, the group suggested that change does not have to be negative, in line with the arguments made by Harvey and Perry (Citation2015) and DeSilvey and Harrison (Citation2020). It also illustrates how engaging with the potential loss of heritage can reveal new meanings (see Dawson Citation2015). The potential change of the tangible natural heritage highlights the adaptive capacity derived from the intangible heritage narrative of sailors and strong women who lived with the tides and the harsh nature. Whether it is the changing tides, incoming storms, or the return of sailors after months or years at sea, life on Fanø has always been dynamic and subject to change, therefore the community will continue to adapt. Because of this powerful narrative, there is potential for the seafaring heritage as a tool in building community resilience against climate change in the future (see Holtorf Citation2018).

However, this does not mean the community will not be affected by changing nature at all. The participants did note that the diversity of nature and the landscape is an important part of why people choose to live on Fanø, and a decrease in that diversity could eventually be a reason to move away. Furthermore, Mille (35) believes that:

A lot of people come here on Fanø to experience nature, the animal life, the beaches, bird life. So if that changes a lot in a negative way, that would affect tourism, and that could affect income, and that would affect all of us.

The natural heritage is an important draw for tourism in the Wadden Sea region (see Egberts and Hundstad Citation2019). Several participants imagined that the island could become less attractive for tourists, and a decline in tourism would in turn have significant consequences for the community and their ability to maintain other heritage aspects. This includes both direct consequences, i.e. financial constraints, and indirect consequences, as residents move away to seek employment elsewhere. Even if the community is willing to accept change, it is not solely up to them. Furthermore, due to the high value of Fanø’s nature, there is protective legislation in place, both locally and internationally. This raises the question, also posed by DeSilvey and Harrison (Citation2020), who decides what heritage is lost or preserved? In addition, Malene (27) wondered if it could also be a complicating factor when it comes to climate change mitigation and adaptation measures:

Can we extend the dikes? (…) Just north of Nordby, we could be able to extend the dike more, but then that extension would go out into a protected nature area. And that means that you have to get a lot of approvals from our national state or by the EU. (…) The dilemma is, should we protect the nature? Or should we also protect the humans and who are more important?

This challenge is also noted in the municipal climate action plan, as is the case with built heritage, the preservation policies for natural heritage limit the possibilities in the energy transition, as there are few places, for example, where policies would allow the build of windmills (Fanø Municipality Citation2023). The protective policies come partly from national governance (the Danish Wadden Sea National Park) and partly from international agreements (Natura 2000, UNESCO World Heritage, and the Ramsar Convention) (Blichfeldt and Liburd Citation2021). But, there is a responsibility for the municipality to take into account the impact heatwaves, sea-level rise, and more intensive precipitation will have on flora and fauna, as they ‘depend on specific conditions and dynamics’ (Fanø Municipality Citation2023). As was noted in the built heritage section, heritage is a choice, but in the case of natural heritage that choice is made at national and international levels. While the Fanø community certainly values the natural heritage, it only has limited say in how to cope with the effects of climate change.

Conclusion

The empirical findings in this study provide an understanding of the importance of cultural and natural heritage have for the Fanø community, and the complexity of addressing localised climate change. The participants in our study associated climate change primarily with extreme events such as flooding rather than gradual changes in weather patterns or sea-level rise. In addition, they related climate change to direct material effects, and they had not previously given much consideration to the long-term effects for customs and traditions within the community. This made it very challenging for them to imagine what the implications of climate change for heritage could be. This suggests that an improved literacy of localised climate change characteristics is necessary for communities to develop an understanding of the effects on all aspects of their lives.

When exploring the practice and meaning of culture during our interviews, the seafaring heritage of Fanø emerged as highly valued; it was even seen as integral to the cultural identity. The community has actively maintained this heritage. Upon reflection, the participants noted that it would be considered a great loss, if climate change effects impact their ability to practise their cultural activities and preserve the built heritage. It would affect the link to the past and ultimately the cultural identity that the community embodies. However, the participants also indicated that changes are acceptable, as long as they can somehow maintain the intangible, ineffable, spirit of Fanø.

Heritage in Fanø was analytically separated into built, living, and natural heritage. However, it is important to note the interconnectedness between these heritage aspects and their entanglement with different aspects of life on Fanø. In particular, the economic entanglement of heritage with income-generating tourism and the connections of islanders to off-island employment need to be considered, as they influence the community’s choices for maintaining their heritage.

Normalising culture-and-climate change as a conversation topic is an important first step in preparing for changes that are coming in the future. We brought to light ways in which people connect with place-based heritage places and practices that are the result of ways of life which developed in close relation to the environmental conditions of the past; seafaring economies, island architecture and everyday practices emerged from these.

Cultures and cultural heritage can also facilitate changes and support community resilience and sustainability (Holtorf Citation2018; Kim Citation2011). Lewicka (Citation2008, 211) says place attachments can give ‘people the sense of stability they need in the ever changing world’. Inhabitants of Fanø incorporated their past of adapting to the dynamics of the Wadden Sea and the seafaring lifestyle into their cultural identity. Because of this, the participants believe the community will continue to adapt to changes in the future. With an improved understanding of the role of heritage in climate change, communities can actively engage with the potential source of strength in coping with changes.

While the (expected) effects of climate change on cultures are often considered undesirable and perceived as a loss, not all climate change effects on cultures will necessarily be perceived as negative changes. If it is considered a loss, there are still multiple possibilities of responding to that potential change. According to DeSilvey and Harrison (Citation2020), accepting heritage loss requires a mourning period. DeSilvey (Citation2017) further suggests applying the concept of palliative care to heritage sites, allowing them to decay while giving the community the chance to say goodbye. But, this is only possible if the decision is made on time. Ashworth and Graham (Citation2005) argue that heritage is a choice made in the present about what to pass on to the future. We argue that communities also have choices to make in how to respond to the effects of climate change on cultures and heritage. However, these choices can only be made if communities know what effects to expect, and have the decision power and means to respond.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ilse C. van Dijk

Ilse van Dijk is a PhD student in Cultural Geography at Groningen University. Her research explores the intersection of climate change and culture, including heritage and cultural practices. The research is focused on the effects of climate change on culture and ways of life, as well as the possibility for coping strategies to respond to these effects. Her work involves qualitative, participatory and creative methodologies.

Bettina van Hoven

Bettina van Hoven is Associate Professor in Cultural Geography at Groningen University. Much of her work evolves around physical, social and affective processes and experiences of exclusion by marginalised groups. However, as a result of her multi-disciplinary background, she also works on human-nature interactions. Her research employs on qualitative, participatory and creative methodologies.

Erik Meijles

Erik Meijles is Associate Professor in Landscape Geography at Groningen University. He has developed an active interest in relations between people and landscapes. Many of his publications and his education cover topics on the impact of people on rural and natural landscapes and how physical environments influence people, including perceptions and heritage values. The interdisciplinary connection of human and physical geography is a key component of his interests.

References

- Abranches, M., and E. Horton. 2024. “Heritage Through Collage: A Participatory and Creative Approach to Heritage Making.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 30 (1): 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2277780.

- Antrop, M. 2005. “Why Landscapes of the Past Are Important for the Future.” Landscape and Urban Planning 70 (1–2): 21–34.

- Ashworth, G. J., and B. J. Graham, eds. 2005. “Senses of Place, Senses of Time and Heritage.” In Senses of Place: Senses of Time (Ser. Heritage, Culture, and Identity), 3–14. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

- Bartolini, N., and C. DeSilvey. 2020. “Recording Loss: Film As Method and the Spirit of Orford Ness.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (1): 19–36.

- Bazelmans, J., D. Meier, A. Nieuwhof, T. Spek, and P. Vos. 2012. “Understanding the Cultural Historical Value of the Wadden Sea Region. The Co-Evolution of Environment and Society in the Wadden Sea Area in the Holocene Up Until Early Modern Times (11,700 BC–1800 AD): An Outline.” Ocean & Coastal Management 68:114–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.05.014.

- Blichfeldt, B. S., and J. Liburd. 2021. “Transcending the Nature/Culture Dichotomy: Cultivated and Cultured World Class Nature.” Journal of Tourism and Development 36 (1): 9–20.

- Carmichael, B., G. Wilson, I. Namarnyilk, S. Nadji, J. Cahill, S. Brockwell, B. Webb, D. Bird, and C. Daly. 2020. “A Methodology for the Assessment of Climate Change Adaptation Options for Cultural Heritage Sites.” Climate 8 (8): 88.

- Dawson, T. 2015. “Taking the Middle Path to the Coast: How Community Collaboration Can Help Save Threatened Sites.” In The Future of Heritage As Climates Change, edited by D. Harvey and J. Perry, 268–288. London: Routledge.

- DeSilvey, C. 2017. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- DeSilvey, C., and R. Harrison. 2020. “Anticipating Loss: Rethinking Endangerment in Heritage Futures.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (1): 1–7.

- Egberts, L., and D. Hundstad. 2019. “Coastal Heritage in Touristic Regional Identity Narratives: A Comparison Between the Norwegian Region Sørlandet and the Dutch Wadden Sea Area.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (10): 1073–1087.

- Fannikerdagen. n.d.-a. “Program 2022.” Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.fannikerdagen.dk/program-2022/.

- Fannikerdagen. n.d.-b. “The Story of the Fanniker Days.” Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.fannikerdagen.dk/.

- Fanø Municipality. 2019. “Kultur-, Fritids- og Idrætspolitik for Fanø Kommune 2019-2023.” https://www.fanoe.dk/politik/politikker-planer-og-strategier/politikker-og-planer.

- Fanø Municipality. 2023. Klimaplan Fanø Kommune 2023-2050. https://www.fanoe.dk/politik/politikker-planer-og-strategier/politikker-og-planer.

- Fenech, A., A. Chen, A. Clark, and N. Hedley. 2017. “Building an Adaptation Tool for Visualizing the Coastal Impacts of Climate Change on Prince Edward Island, Canada.” In Climate Change Adaptation in North America: Fostering Resilience and the Regional Capacity to Adapt, edited by W. Leal Filho and J. M. Keenan, 225–238. Cham: Springer.

- Fonden Gamle Sønderho. n.d. “Sønderho Day.” Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.fondengamlesonderho.dk/soenderhodag-en/.

- Fruergaard, M., L. Kirkegaard, A. T. Østergaard, A. S. Murray, and T. J. Andersen. 2019. “Dune Ridge Progradation Resulting from Updrift Coastal Reconfiguration and Increased Littoral Drift.” Geomorphology 330:69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.01.008.

- Harvey, D. C., and J. Perry, eds. 2015. “Heritage and Climate Change: The Future Is Not the Past.” In The Future of Heritage As Climates Change, 23–42. London: Routledge.

- Hennink, M., I. Hutter, and A. Bailey. 2020. Qualitative Research Methods. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Holtorf, C. 2018. “Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience Is Increased Through Cultural Heritage.” World Archaeology 50 (4): 639–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340.

- Kim, H.-E. 2011. “Changing Climate, Changing Culture: Adding the Climate Change Dimension to the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Cultural Property 18 (3): 259–290.

- Krageskov, F. 2005. “Deense Waddenkust.” In Wadden Verhalend Landschap: Cultuurhistorische reis langs de waddenkust van Denemarken, Duitsland en Nederland, edited by J. Abrahamse, M. Bemelman, and M. Hillenga, 38–71. Baarn: Tirion Natuur & Common Wadden Sea Secretariat.

- Krauβ, W. 2015. “Heritage and Climate Change: A Fatal Affair.” In The Future of Heritage As Climates Change, edited by D. C. Harvey and J. Perry, 63–81. London: Routledge.

- Lauridsen, S., and K. Halberg. 2013. Fanø Mosaik. Translated byH. B. Foldager. Jyllinge: Forlaget Mathilde - Coffeetablebooks.

- Lewicka, M. 2008. “Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (3): 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.02.001.

- Low, S. 2017. Spatializing Culture: The Ethnography of Space and Place. New York: Routledge.

- Lowenthal, D. 2005. “Natural and Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 11 (1): 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250500037088.

- Modeen, M., and I. Biggs. 2020. Creative Engagements with Ecologies of Place: Geopoetics, Deep Mapping and Slow Residencies. London: Routledge.

- Munshi, D., P. Kurian, R. Cretney, S. L. Morrison, and L. Kathlene. 2020. “Centering Culture in Public Engagement on Climate Change.” Environmental Communication 14 (5): 573–581.

- Oost, P., J. Hofstede, R. Weisse, F. Baart, G. Janssen, and R. Zijlstra. 2017. “Climate Change.” In Wadden Sea Quality Status Report 2017, edited by S. Kloepper, et al. Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Common Wadden Sea Secretariat. Last updated 21.12.2017. Retrieved August 13, 2023. qsr.waddensea-worldheritage.org/reports/climate-change.

- Prosser, J., and A. Loxley. 2008. “Introducing Visual Methods.” ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper. NCRM/010 October.

- Reeves-Ellington, R. H., and F. J. Yammarino. 2010. What is Culture? Generating and Applying Cultural Knowledge. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Reise, K., M. Baptist, P. Burbridge, N. Dankers, L. Fischer, B. Flemming, A. P. Oost, and C. Smit. 2010. “The Wadden Sea - A Universally Outstanding Tidal Wetland.” Wadden Sea Ecosystem 29:7–24.

- Richardson, B. 2015. “Introduction: The “Spatio-Cultural Dimension”: Overview and a Proposed Framework.” In Spatiality and Symbolic Expression: On the Links Between Place and Culture. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137488510_1.

- Riesto, S., L. Egberts, A. Aslaug Lund, and G. Jørgensen. 2022. “Plans for Uncertain Futures: Heritage and Climate Imaginaries in Coastal Climate Adaptation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28 (3): 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.2009538.

- Schepers, M., E. W. Meijles, J. P. Bakker, and T. Spek. 2021. “A Diachronic Triangular Perspective on Landscapes: A Conceptual Tool for Research and Management Applied to Wadden Sea Salt Marshes.” Maritime Studies 20 (3): 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-021-00215-4.

- Shaykh-Baygloo, R. 2020. “A Multifaceted Study of Place Attachment and Its Influences on Civic Involvement and Place Loyalty in Baharestan New Town, Iran.” Cities 96:102473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102473.

- Skriver, J. 2022a. “Massedød af havfugle på vestkysten af Fanø.” Dansk Ornitologisk Forening. February 18, 2022. https://www.dof.dk/om-dof/nyheder?nyhed_id=2048.

- Skriver, J. 2022b. “Massedød blandt havfugle: Sulerne på Vestkysten er døde af fugleinfluenza.” Dansk Ornitologisk Forening. June 30, 2022. https://www.dof.dk/om-dof/nyheder?nyhed_id=2079.

- Statistics Denmark. 2022. “Population 1. January by Municipality and Time.” https://www.statbank.dk/20021.

- Tilley, C. 2006. “Introduction: Identity, Place, Landscape and Heritage.” Journal of Material Culture 11 (1–2): 7–32.

- Titz, A., T. Cannon, and F. Krüger. 2018. “Uncovering ‘Community’: Challenging an Elusive Concept in Development and Disaster Related Work.” Societies 8 (3): 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030071.

- Visit Fanø. 2023. “Experience”. Accessed August 12, 2023. https://visitfanoe.dk/en/experience/.

- Vollmer, M., M. Guldberg, M. Maluck, D. van Marrewijk, and G. Schlicksbier. 2001. “Landscape and Cultural Heritage in the Wadden Sea Region—Project Report.” In Wadden Sea Ecosystem, 12, Wilhelmshaven, Germany: Common Wadden Sea Secretariat.