ABSTRACT

As media users are trying to avoid traditional forms of advertising like display ads, companies apply content marketing techniques such as native advertising, sponsored content and company-owned media to reach their audiences. Such hybrid forms of content lead to a blurring of boundaries between editorial content and advertising and are not as easily recognized as promotional. This qualitative study examines consumers’ perspectives and reactions to different types of content marketing products by taking paid and owned media into account. Data from 50 qualitative interviews with media users were analysed by means of thematic qualitative text analysis. The results indicate that consumers often perceive hybrid content as a mix of information and advertising. Advertising recognition is most often based on content-driven characteristics of the message, such as mentioning a product and less so on the advertising disclosure label. This study derives four types of content marketing consumers: neutrals, enthusiasts, contemplators and critics. It contributes to the literature by strengthening the understanding of consumers’ perceptions of different types of hybrid content.

Introduction

Consumers are exposed to a plethora of advertising messages every day. Because online advertising formats are often very intrusive, leading to annoying ad experiences, people try to avoid them by simply ignoring the ads or using adblockers (Belanche Citation2019). As a consequence, companies increasingly use more surreptitious methods such as stealth marketing (De Pelsmacker and Neijens Citation2012; Kaikati and Kaikati Citation2004) and try to communicate their commercial content in a less irritating and more informative and entertaining way (Tutaj and van Reijmersdal Citation2012). The focus here is not so much on the company or a specific product but rather on content that only indirectly addresses the company or its offerings by often embedding them in engaging stories. A journalistic communication style is frequently applied instead of using promotional language. This leads to blurred boundaries between editorial content and advertising and to what has been called ‘hybrid forms of content’ (Taiminen, Luoma-Aho, and Tolvanen Citation2015).

Hybrid content includes different forms of content marketing like native advertising, sponsored content and company-owned media like customer magazines. One of the main characteristics of hybrid forms of content is that they do not look like advertising formats, which is why scholars describe it as covert advertising (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020). Controversy arises when such content lacks transparency of the source or aim, and ‘audiences are likely to be unaware of the commercial influence attempt’ (Balasubramanian Citation1994, 30) because consumers have learned to deal with classical forms of advertising, but they often do not recognize the persuasive intent of hybrid forms of content (e.g., Tutaj and van Reijmersdal Citation2012). Over and above the issue of transparency, content marketing – particularly native advertising – also poses challenges for traditional journalism and its credibility (e.g., Amazeen and Muddiman Citation2018; Wojdynski and Golan Citation2016). Additionally, content marketing contributes to the academic debate on the relationship between public relations and marketing, as both disciplines use it to create awareness for brands (Anani-Bossmann and Obeng Citation2022).

Owned media (Baetzgen and Tropp Citation2013) and sponsored content are not new. However, digitalization and the rise of new communication technologies have enabled companies to produce such content quite easily on multiple platforms and in different formats, including print and digital media. More and more companies publish their own content or even news media that are often of high editorial quality (Koch, Viererbl, and Schulz-Knappe Citation2021). The increase in quantity and quality of corporate publishing products and paid forms of hybrid content, i.e., native advertising and sponsored content that appear in third-party media, emphasizes the relevance of addressing the phenomenon broadly. While extant research has generally focused on the perception of specific variants of hybrid content – either paid (e.g., Amazeen and Muddiman Citation2018; Kendrick and Fullerton Citation2021; Park, Kim, and Lee Citation2020; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016) or owned (e.g., Florès et al. Citation2008; van Reijmersdal, Neijens, and Smit Citation2010) – this study takes a broad approach by investigating consumers’ perceptions of different forms of content marketing, including paid and owned media as well as print and digital formats. Specifically, this research seeks to investigate how consumers perceive and react to different forms of content marketing and how they reflect on hybrid content.

Based on the covert advertising recognition and effects model (CARE; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020) and the persuasion knowledge model (PKM; Friestad and Wright Citation1994), this research strengthens the understanding of consumers’ perceptions of hybrid forms of content and offers important insights into their opinions and reflection on such content. Furthermore, this study considers the role of new media literacy (Chen, Wu, and Wang Citation2011) in this process, which has been neglected in several studies on the perception of covert advertising.

In the following, we first give a brief overview of hybrid forms of content as it manifests as content marketing. We then delineate the different pathways in advertising recognition presented in the CARE model (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020). After discussing the role of media literacy in the process of perceiving hybrid content, we outline the PKM (Friestad and Wright Citation1994) as a central theoretical foundation. The research questions were addressed by means of qualitative research among 50 consumers. Following the presentation of results and discussion, this paper provides theoretical and practical implications by highlighting the importance of persuasion knowledge and media literacy.

Literature review

As defined by Pulizzi (Citation2012, 116), ‘content marketing is the creation of valuable, relevant and compelling content by the brand itself on a consistent basis, used to generate a positive behaviour from a customer or prospect of the brand’. While companies often use owned media channels for content marketing practices, the content can also be distributed by paid media, including native advertisements. Native advertising and sponsored content represent any paid content that mimics the form and appearance of editorial content from the publishing medium (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016). This study focusses on hybrid content with a commercial intent that appears in various forms in paid and owned media.

Pathways to advertising recognition

Wojdynski and Evans (Citation2020) underline the importance of the process of advertising recognition instead of simply differentiating whether recipients perceive media content as advertising or not. They describe native advertising, content marketing and branded content as ‘a form of advertising that can best be called covert, in that these forms render all or some aspects of what make an advertisement recognizable to the typical consumer obscured, opaque, or missing’ (4). Data from several studies suggest that advertising recognition is difficult for media users when they are confronted with covert advertising that looks like editorial format (e.g., Amazeen and Muddiman Citation2018; Tutaj and van Reijmersdal Citation2012; Wojdynski Citation2016). Another study shows that even one out of four advertising students does not classify a piece of native advertising labelled ‘sponsored content’ as an advertisement (Kendrick and Fullerton Citation2021). Additionally, consumers rarely pay attention to disclosure labels, which are required by law in many countries (Amazeen and Wojdynski Citation2020; Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016).

Kim, Pasadeos, and Barban (Citation2001) assume that advertising recognition can result not only from disclosure labels but also due to content-related elements. This finding is similar to one of the fundamental assumptions of the CARE model by Wojdynski and Evans (Citation2020). By drawing on potential antecedents and processes of recognizing covert advertising, the authors established several pathways to the outcome of persuasive communication. Advertising recognition and processing of covert advertising can take place in three ways: (1) through explicit disclosure, (2) through characteristics of message content and (3) through delivery message context characteristics (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020). Disclosure processing is categorized as top-down recognition, whereas bottom-up recognition is content-driven or context-driven.

Top-down recognition refers to differences in disclosure position, prominence and disclosure language. Earlier research showed that positioning, visual prominence and language of the label play a significant role in this process (Amazeen and Wojdynski Citation2020; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016). For instance, a clear disclosure label and prominent placement facilitate advertising recognition. Wojdynski and Evans (Citation2016) found that media users more frequently perceive a label of sponsored content when it is placed in the middle of the article compared to placement at its beginning or end. Bottom-up recognition, on the other hand, includes message characteristics such as brand presence, a bias or selling intent and the presence of a proximal source. It furthermore involves context characteristics, i.e., the timing, a perceived delivery rationale, the context congruity or specific features of the platform where it is published. If one of the potential recognition processes is activated, this leads to advertising recognition and instantiation of the advertising schema (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020).

This study aims to explore what consumers perceive as indicators for advertising in the context of content marketing publications by differentiating between top-down and bottom-up recognition. This leads to our first research question:

RQ1:

How do consumers process and identify the promotional intent of different forms of content marketing?

The role of (new) media literacy in perceiving hybrid content

Even after classifying a message, the understanding and reflection of content requires a series of skills that can be summarized as media literacy. In times of new media and blurring boundaries between journalism, advertising and public relations, these skills have become even more essential. Existing literature provides multiple definitions of media literacy (e.g., Eagle Citation2007; Hobbs Citation2013; Potter Citation1998). The general idea behind media literacy is the following: ‘A media literate person – and everyone should have the opportunity to become one – can decode, evaluate, analyse and produce both print and electronic media’ (Aufderheide Citation1993, 1). As this definition can be traced back to a time of predominantly analogue media, the concept of media literacy has gone through several stages over the past decades (Cervi, Paredes, and Pérez Tornero Citation2010; Pérez Tornero Citation2006).

New media literacy, which is most recently discussed in the literature (Chen, Wu, and Wang Citation2011; Lin et al. Citation2013; Koc and Barut Citation2016), is introduced first due to the increasing importance of digital media. It is also relevant for the consumption of traditional media, as the overall use of content and the relationship between recipient and media has changed over the past decade. As suggested in the study of media literacy trends in Europe (Pérez Tornero Citation2006), new media literacy represents a convergence of all previously developed types of literacy.

Chen, Wu, and Wang (Citation2011) propose a framework of new media literacy that can be applied to different types of media in the digital as well as print environment. Following this approach, new media literacy can be considered as two continuums of literacy, ranging from consuming to prosuming and from functional to critical. Consuming skills, on the one hand, enable people to access, understand, analyse and evaluate media content; prosuming media literacy, on the other hand, comprises the ability to create and produce media content (Chen, Wu, and Wang Citation2011). When investigating media users’ perception of content marketing, aspects of consuming are more important than aspects of producing. Thus, the focus here is on consuming, while considering the differentiation between functional and critical media literacy. This results in two types of media consumers: (1) functional media consumers and (2) critical media consumers (Chen, Wu, and Wang Citation2011). While functional media consumers are able to access the media content and understand the message, critical media consumers furthermore analyse and evaluate media content involving the social, economic, political and cultural context of a message. This is in line with the assumption that critical consuming literacy refers to a person’s skill to perceive a message as subjective rather than neutral and to evaluate its reliability and credibility (Koc and Barut Citation2016). Both functional media literacy and the critical reflection of content might be helpful when evaluating the persuasive attempt of hybrid content.

Other authors also emphasize the relevance of advertising literacy when it comes to advertising effects (Malmelin Citation2010; Rozendaal et al. Citation2011). However, content marketing cannot be considered traditional advertising but rather advertising disguised with relevant information for the reader. Thus, the broader framework of new media literacy according to Chen, Wu, and Wang (Citation2011) is considered the appropriate theoretical foundation here.

Research by Weitzl, Seiffert-Brockmann, and Einwiller (Citation2020) demonstrates that recipients’ new media literacy moderates the impact of sponsorship and forewarning disclosures on attitudinal persuasion knowledge. It shows that people with a high compared to a low level of new media literacy are more likely to activate their attitudinal persuasion knowledge when sponsorship/forewarning disclosures are present. To better understand advertising students’ media literacy skills, Kendrick and Fullerton (Citation2021) analysed the degree of media literacy the students exhibited in open-ended responses justifying why a sponsored content article was advertising or not. However, research in this context is scarce. This study seeks to address this research gap by analysing the role of media literacy skills in identifying the persuasive intent of content that appears in an informational or even editorial context. The second research question reads:

RQ2:

What role does (new) media literacy play in identifying the promotional intent of different forms of content marketing?

Persuasion knowledge model in the context of hybrid content

While persuasion knowledge and media literacy are related, the PKM by Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) represents a more specific approach for how people apply their knowledge of persuasion motives and tactics used by organizations and marketers to interpret, evaluate and respond to their influence attempts. People develop persuasion knowledge over time by consuming various forms of media. By doing so, they learn to recognize traditional advertising formats such as television commercials or display advertising. The PKM assumes that the recognition of advertising is a key trigger of persuasion knowledge and the associated coping behaviours, which encompass cognitive and physical actions during a persuasion episode, as well as thinking about the organization’s persuasion behaviour. Coping behaviours can include scepticism and avoidance of the advertisement, yet, Friestad and Wright (Citation1994) stress that resisting a persuasion attempt is not invariably or typically how people respond. ‘Rather, their overriding goal is simply to maintain control over the outcome(s) and thereby achieve whatever mix of goals is salient to them’ (3).

Adult media consumers generally have no problem detecting a persuasive intent in traditional advertising formats and subsequently activate their persuasion knowledge (e.g., Rozendaal, Buijzen, and Valkenburg Citation2010). However, research shows that consumers have difficulties in recognizing the promotional intent of content marketing in the form of paid media, such as native advertising or sponsored content (e.g., Tutaj and van Reijmersdal Citation2012; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016). Similarly, the persuasive intent of content marketing in the form of owned media is often inconspicuous to people and mainly detected when the medium has clear commercial features (van Reijmersdal, Neijens, and Smit Citation2010). Thus, due to their inconspicuousness, hybrid forms of content – like the different forms of content marketing – are less likely to activate people’s persuasion knowledge and, consequently, their persuasion coping behaviours.

For organizations that aim to persuade consumers of their products, services or other, this may be the desired effect, because recognizing the persuasive intent of covert ads can lead to negative attitudes toward the advertiser and publisher of sponsored news articles (Amazeen and Wojdynski Citation2020; Wojdynski and Evans Citation2016), toward the brand in sponsored blogs (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2016) and toward a customer magazine and its perceived credibility (van Reijmersdal, Neijens, and Smit Citation2010). Yet, as implied by the PKM, coping does not necessarily lead to negative effects. It may also be that the content marketing product serves the goal that is salient to the consumer at this moment. Advertising may have value to the consumer (Ducoffe Citation1995), and since content marketing is supposed to contain valuable, relevant and compelling content (Pulizzi Citation2012), it may very well meet consumers’ interests and goals. Previous research has established, for example, that native advertising is perceived as more engaging and less disruptive than display advertising (Tutaj and van Reijmersdal Citation2012). By drawing on the concept of consumption values in the context of digital content marketing, a recent study by Lou and Xie (Citation2021) reported that for high-product involvement, the perceived informative value of branded content had a positive effect on participants’ experiential evaluation of the brand and entertainment, and social value positively affected experiential evaluation for both high- and low-product involvement brands. In addition, the results of this study revealed consumers’ brand experiential evaluation as an underlying mechanism of content marketing predicting brand loyalty. While traditional forms of advertising are often irritating, hybrid forms of communication that combine features of journalistic products and elements of strategic communication might be more acceptable and even beneficial for consumers.

This raises the question of how consumers perceive and evaluate content marketing. When recognizing it as commercial, does it activate the persuasion knowledge they learned from traditional advertising? How sceptical or embracing are they of such novel forms of persuasive attempts? Hence, the third and last research question reads:

RQ3:

How do consumers perceive and react to different forms of content marketing?

Method

In order to answer the three research questions, 50 qualitative interviews with consumers were conducted. As qualitative research is designed openly and allows for individuality and flexibility in the research process (Flick Citation2014), this is an appropriate way to examine different perspectives on hybrid forms of content. The interviews were conducted by 12 master’s students in communication science. They followed a semi-structured approach (Helfferich Citation2011) using an interview protocol, which was pretested in 12 interviews.

Sample

Interviews were conducted between May and June 2019. The sample comprised 50 media users, who had to have at least some experience with online (news) media. In total, 24 of the participants were male and 26 were female; they were between 18 and 75 years of age. Their education level ranged from secondary school (n = 2) to high school (n = 12), vocational school (n = 15), to university or polytechnic (n = 21). Regarding occupation, participants were students (n = 9), employees in different types of organizations (n = 34) or retired (n = 7).

Stimuli

The stimuli comprised different types of content marketing products, including a customer magazine, a corporate blog, a sponsored media supplement, an online native advertisement on a news site and a sponsored Facebook post. The stimuli also included a journalistic article from an online news site to conceal the purpose of the study. The specific stimuli were selected based on a comprehensive investigation of various content marketing examples in the national media. The final set contained 11 stimuli in order to cover a wide range of topics and companies. From this set of stimuli, interviewers randomly selected five different content marketing examples for each interview, ensuring that each content marketing type (both paid and owned media stimuli) as well as one journalistic article was included.

Interview procedure

Interviews were conducted in person. Interviewees were told that the interview would deal with their media consumption in general, so they were not aware that the study was about the perception of content marketing. Before the start of the interview, participants were asked for their informed consent to participate and record the interview and assured full anonymity.

At the beginning of the interview, participants were asked about their media use. Then, the stimuli were presented to the interviewees. They were given as much time as they needed to look at each stimulus. Interviewees were asked to reflect on how interesting they found the content of each stimulus, what it was about, who they thought had authored it and with what intent and whether they perceived it as credible and why or why not. In a second round, interviewees who had not yet mentioned that they considered a stimulus advertising or had mentioned the disclosure label were prompted to reflect whether this could be advertising; they were also pointed to the disclosure. Participants were asked whether they were familiar with specific advertising disclosure labels used in the stimuli. Next, interviewees’ persuasion knowledge was assessed by asking, for example, if they generally pay attention to whether something is advertising or not and how they identify advertising. New media literacy, particularly consumer scepticism, was gauged by asking how critically the participant usually consumes media. Interviewees were subtly prompted to self-assess their media literacy by reflecting on their skills to differentiate different forms of media, evaluate the credibility of messages and whether they thought they could be persuaded by such hybrid forms of content. The last part of the interview dealt with people’s specific knowledge and awareness of content marketing as a marketing strategy. Finally, interviewees were informed about what content marketing is and thoroughly debriefed about the goal of the study.

Thematic qualitative text analysis

After transcribing the interviews, thematic qualitative text analysis was used to analyse the interviews, following the seven steps proposed by Kuckartz (Citation2014), 73–90): (1) initial text work, highlighting important passages and writing memos, (2) developing the main thematic categories from the research questions and interview protocol, (3) first coding of all data using the main categories, (4) compiling all of the text passages that belong to each of the main categories, (5) inductively creating sub-categories based on the data, (6) second round of coding of all data using the category system including sub-categories and (7) category-based analysis and documentation of results.

The main categories were created deductively from the literature and the interview questions. Sub-categories like the familiarity with a type of communication, consumers’ interest and the perceived credibility, as well as the classification of the content as advertising or not, were developed inductively for each type of stimulus. Also, the different types of content marketing were coded separately to account for differences in their perception. Based on the data, we differentiated between the categorization of the content as advertising, neutral information and a mix of advertising and information.

Media literacy was coded into low, moderate and high. To do so, we analysed the individual responses and the self-reflection of the participants in each case and then categorized them. To compare the assessment of media literacy with participants’ skills in recognizing the promotional intent behind the stimuli, we added four sub-categories: (1) promotional intent of all content marketing stimuli identified, (2) promotional intent of most of the content marketing stimuli identified, (3) promotional intent of most of the content marketing stimuli not identified and (4) promotional intent of all content marketing stimuli not identified.

To answer the research questions, we conducted category-based analyses of the main categories and assessed relationships between sub-categories within a main category and relationships between categories. The software MAXQDA was used to support the analysis.

Results

Indicators of identifying the promotional intent

To answer the first research question, we analysed the reasons why interviewees perceived the content as commercial. Reasons included both content- or context-driven characteristics and disclosure-driven characteristics of the stimuli. The majority of participants believed the content was advertising due to message characteristics, such as the perception of a product reference (selling intention), a brand or company reference or a content bias (one-sidedness), which is termed bottom-up recognition. The following statement exemplifies a content-related reason for considering the customer magazine as advertising:

Because the one who writes the magazine is not trying to inform me but is trying to convince me of something that he can then use.

Results show that top-down recognition happens quite rarely, i.e., people did not pay much attention to the disclosures. Although many interviewees detected the ‘sponsored’ labelling on the Facebook post, most of the participants did not detect the disclosures on the other paid media examples, the native ad and the sponsored media supplement. Younger participants, in particular, pay more attention to labelling in social media. For example, one person stated:

I think I pay more attention to that on Facebook and Google because it’s always clearly labelled, and I know where to look.

In contrast, others generally do not care much whether paid content is labelled or not:

I don’t pay attention to the labelling, because I recognize very well if an article is biased in a specific direction. But it doesn’t matter to me if it’s labelled.

Regarding owned media, the disclosures on the stimuli were not as obvious as on the paid media examples. Nevertheless, respondents mentioned the logo of the brand on the customer magazine or corporate blog as an indicator of the content being advertising. Additionally, several participants checked the imprint of the magazine or the blog and consequently identified the source as commercial. Bottom-up arguments that occurred less frequently included context characteristics of the message, such as related links and information or the platform on which the content appeared. The latter implies that interviewees expected the content to be advertising in social media and as media supplements. However, some participants initially overlooked the promotional intent of the hybrid content and only recognized this after taking a closer look at the stimulus or being directed to it by the interviewer.

Sociodemographic characteristics and the amount of media use do not play an apparent role in the reception of content marketing and the recognition of promotional content. However, older participants tended to be more sceptical about advertising content, while younger respondents more frequently explicitly identified paid content in social media as advertising.

New media literacy

The second research question asked about the role of (new) media literacy in identifying the promotional intent of hybrid forms of content. Most participants self-assessed themselves as having a moderate level of media literacy. The following quote exemplifies a low self-assessment of media literacy regarding the ability to differentiate between informational, advertising and entertainment content:

Honestly, I don’t worry about that. I don’t sit in front of the TV and think, is this advertising, or is this information, or is this perhaps some kind of political thing? I watch it, and either it’s interesting to me or it’s not. I don’t think about it.

Because these questions were asked after the perception of the stimuli, several consumers had already reflected on their skills to differentiate between different forms of content. The following quote is an example of a moderate level of media literacy:

Actually, I thought I could tell the difference quite well. But now that we’ve been talking about it, it’s been quite difficult for me.

One interviewee was a marketing expert who estimated his media literacy to be high. He stated that it was easy for him to differentiate between the functions of media content and evaluate the credibility of hybrid content. Simultaneously, he expected the average consumer not to be so critical about such practices. He elaborated:

It’s easy for me because that’s my business. Because I have to deal with it every day. But those who are not so involved think everything is true and believe it to be so. So, I think people, the average, or the majority of the population, who don’t look at it that deeply, find it credible.

The findings indicate that people who consider their media literacy to be high or moderate tend to better identify the promotional intent of content marketing. Most of those with a high self-assessment of media literacy perceived all content marketing stimuli as commercial, and most participants with a moderate self-assessment identified the promotional intent for most of the content marketing stimuli. In contrast, participants with a low level of media literacy tended to have more difficulties, as most of them did not identify most of the stimuli as promotional.

Thus, a high and moderate self-assessment of media literacy seems to be positively related to people’s abilities to consider content marketing as commercial. Therefore, it can be assumed that there is a positive relationship between (self-assessed) media literacy and the recognition of the promotional intent of hybrid content.

Content marketing as a mix of information and advertising

The third research question addressed how consumers perceive and react to different types of hybrid forms of content. The findings demonstrate that many consumers do not clearly distinguish between journalistic or informational content on the one hand and advertising on the other hand. Instead, many participants described the content as a mix of information and advertising:

Yes, it’s a mixture of entertainment and information, but it’s also advertising of course. So, it’s a combination of everything.

Not all participants who identified the commercial source behind the content perceived it as advertising. Those who did not perceive the content as promotional rather described it as neutral information. Several participants even denied when the interviewer asked whether the content they just saw might have been advertising, which shows that their persuasion knowledge for traditional advertising was incompatible with the hybrid forms of content they were presented with.

I wouldn’t see it as an advertisement but rather as an information supplement.

(female, 25 years, regarding the sponsored media supplement)

Others concluded that the stimulus is advertising and reflected on the inconspicuousness of the sponsored content:

Yes, I think this is an advertisement. When I look at it more closely. It’s hidden advertising.

It’s advertising obscured with informative content.

What was considered advertising or not also depended on the type of content marketing. Several participants classified paid media more clearly as advertising, while they were unsure about the owned media stimuli, as the following statements illustrate:

But I’m not quite sure if this is really advertising as I usually know it.

For me, these are individual articles that deal with different topics. Yes, there may be tips in between or information on where to buy certain things, but it’s not really an advertising magazine.

The interviews showed that participants focused mainly on the topic and less on its potentially biased source. When the content was considered interesting, reactions tended to be positive, even if people noticed the commercial source. Some participants elaborated that it makes no difference to them if something is advertising or not as long as it is interesting. However, if the stimulus contained a clear selling intent, reactions tended to be more negative. Negative reactions also occurred when people noticed the commercial source of the content after they had at first overlooked it; they felt deceived and betrayed. One person, for example, described the advertising in the sponsored content article in an online newspaper as ‘cheeky’ (male, 19). Overall, the sponsored Facebook post generated particularly negative reactions, whereas reactions towards the owned media stimuli and the media supplement tended to be less negative. This is because the latter offered diverse and detailed information, but the commercial intent was also recognized less frequently here.

The aversion to social media advertising was also reflected in the negative evaluation of the message credibility of the sponsored Facebook post. Yet, generally, when interviewees found the content to be well-made, they did not necessarily consider it less credible after identifying the commercial source:

Yes, I find it credible because the products somehow fit the topic. It appears very coherent, I must say.

Participants also mentioned that the publishing medium has an impact on the perceived credibility. Sponsored content in online newspapers tended to be more credible than paid content in social media.

Asked whether they had heard about content marketing before, the majority of participants said that they had not. Although they had been confronted with it, they were not familiar with the term. Of the 50 interviewees, 16 were able to more or less correctly explain what content marketing may stand for or what it wants to achieve; one of them was the marketing expert.

A typology of content marketing consumers

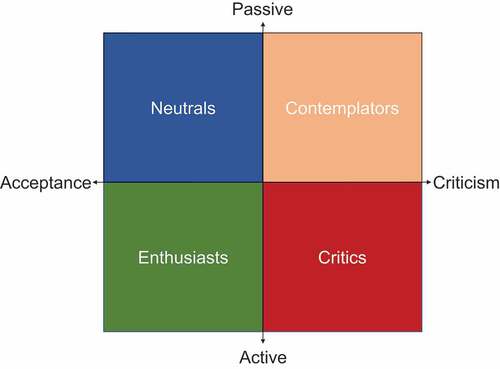

Based on our findings, we identified four types of content marketing consumers along two continuums ranging from (1) acceptance to criticism and (2) active to passive. The first continuum is based on the different reactions of recipients regarding the content marketing stimuli. As described above, both positive and negative reactions towards hybrid content occurred to various degrees, which implies different levels of acceptance or criticism. The second continuum ranging from active to passive is based on the finding that some consumers showed strong reactions such as outrage or fascination toward this type of persuasive communication, while others were less concerned and less emotional in their reactions. depicts the four types of content marketing consumers: neutrals, the enthusiasts, the contemplators and the critics.

Neutrals are characterized by their passive acceptance of hybrid content. They are open to consuming the content and would read it if it seems interesting, even though they know it is advertising. This reaction is rather passive, as they show little interest in the author’s purpose and the type of advertising. According to neutrals, it is important that the content itself is interesting:

If something is of interest to me, I read or watch it. No matter if it’s advertising or not.

This certainly includes reports that are interesting, helpful or informative to me – even if it is somehow advertising. I don’t feel deceived.

Enthusiasts’ reactions to content marketing are characterized by active acceptance. Although they actively reflect on the purpose of the content, they still find it interesting without automatically doubting its credibility. This type includes consumers who are surprised or impressed by the way this type of advertising appears and show no reactance when they realize that the content is an advertisement, even after initially overlooking it:

Ah, it is advertising after all. Exciting, this is how advertising also works. It is well-hidden advertising.

Enthusiasts may also consider content marketing a necessary and legitimate way for news media to make money, as the following quote exemplifies:

Well, these are all media, i.e., service providers that have to sustain themselves somehow. And they can only do that if they advertise and get money.

The contemplators are characterized by their passive criticism of content marketing. They are aware of the persuasive intent of the message, but instead of actively criticizing this type of advertising, they contemplate the purpose of the content and its credibility to not be influenced by it unintentionally. Some contemplators would not read the content after they identified its commercial intent or trust the content if they read it. One participant explained that hybrid forms of content can include helpful information, but ‘I always have to be aware (of) who I’m getting the information from’ (female, 50 years). Similarly, another person contemplated the credibility issue as follows:

I think that most of it is probably true. They will then just omit the negative things and emphasize the positive things, but this already distorts the truth. And that’s how you fool people.

The fourth type of content marketing consumers comprises people who actively criticize hybrid forms of content. Critics are outraged about content marketing and evaluate it negatively due to the inconspicuous persuasive intent. They show stronger negative reactions than the contemplators, perceive it as more disturbing than traditional forms of advertising and call for more transparency. According to the marketing expert:

Everything that is hidden like this is actually not fair but manipulation. One must clearly show the difference: This is advertising, this is well-researched content, and this is a personal opinion.

Another participant strongly criticized the commercial nature of the sponsored content article:

This is advertising that wants to look like a journalistic article. To me, this is an even worse form of advertising.

Overall, the majority of participants were neutrals or contemplators whose reactions were less concerned about the hybrid forms of content.

Discussion

Companies are increasingly applying content marketing techniques like native advertising, sponsored content and company owned media to reach their audiences and break consumers’ advertising avoidance patterns. Such hybrid forms of content do not look like traditional advertising formats; they are not as easily recognized as promotional, which also aggravates the activation of persuasion knowledge. This research set the objective to analyse media consumers’ recognition and perception of different forms of such hybrid content.

Most of the 50 participants in the qualitative research identified the persuasive intent of the content marketing stimuli through the bottom-up and only rarely through the top-down pathway. This finding contributes to Wojdynski and Evans (Citation2020) CARE model by providing a test of the suggested pathways. By including owned media, this research helps extend the CARE model by adding the imprint to the elements of top-down ad recognition. It also reveals differences between the different types of media. On social media, the disclosure was more easily detected, especially by younger participants, who have a higher social media use than older people, which likely contributes to their acquisition of the necessary persuasion knowledge also for social media ad content. Owned media, however, appeared less transparent, as the source is often hidden in the imprint. Thus, they were less often identified and perceived as advertising.

The research furthermore highlights the role of media literacy. People with a moderate and high self-assessment of media literacy tended to better identify the promotional intent of content marketing products. Thus, a certain level of media literacy seems to be important for the identification of hybrid forms of content as promotional. However, consumers did not automatically perceive content marketing as advertising, even if they correctly identified the source of the content. This suggests that many people still hold a rather narrow definition of advertising as something flashy using big letters and pictures. That content which contains interesting information can also be advertising is not learned and therefore not part of many peoples’ persuasion knowledge (yet).

The data suggested four types of content marketing consumers depending on how critical and active they are. On the one hand, there are neutrals and enthusiasts who accept this form of persuasive promotional communication. They, for example, see content marketing as a necessity for media companies to make money; others value the informational character, and some are even enthusiastic about this new form of less intrusive and more informative advertising. On the other hand, however, contemplators and critics are sceptical that this form of advertising is a positive development. They perceive their freedom is particularly curtailed by the inconspicuousness of the promotional intent, which some refer to as deception. Thus, they exhibit psychological reactance (Brehm Citation1966; Brehm and Brehm Citation1981), which is particularly high when the promotional nature of the content is only detected after consuming it. While some only passively contemplate this lack of transparency, others call for policymakers to crack down on such practices.

Implications

While several studies have addressed the relationship between public relations and marketing (e.g., Anani-Bossmann and Obeng Citation2022; Kitchen and Moss Citation2006), this research contributes to the academic debate on blurring lines between journalism, public relations and marketing/advertising manifested by hybrid forms of content. It provides a test and enhancement of the CARE model (Wojdynski and Evans Citation2020) and reveals different media consumer types ranging from accepting to criticizing. Importantly, the findings contribute to the debate regarding the transparency and ethical nature of strategic communication, which takes place not only in academia but also increasingly in practice and society.

The practical implications for strategic communication are, on the one hand, that content marketing can be positively viewed by stakeholders, especially when it is interesting and valuable to them. This holds for paid as well as for owned media. However, on the other hand, companies need to be aware that a lack of transparency can activate critics to voice their complaints and possibly activate others to join in the criticism. Beyond that, transparency is a central requirement of ethics. Thus, to exercise their social responsibility in communication, companies must be transparent and prominently disclose themselves as the source in their content marketing products.

Implications for society and policymakers are considerable. Importantly, the findings of this research imply that advertising disclosure labels required by media law in most countries are not as effective as intended by policymakers. This particularly applies to owned media, which are often not considered in policies that mainly focus on paid media. Thus, policymakers should expand the focus regarding this type of communication and make it a requirement that owned media clearly display the (brand) logo or name of the company on the front or entry page because most media consumers do not check the imprint to find out who the content is from.

Because people generally pay little attention to disclosures, but rather detect the promotional nature of the content marketing product from message characteristics, the research clearly reveals the necessity for more media education. As shown by the age effect of detecting sponsored social media posts, experience with a certain media type can help to enhance persuasion knowledge. However, this does not automatically mean that younger people are more media literate. As the findings reveal, older participants were more sceptical and critical towards content marketing than younger people. Thus, media education must become a fixed part of school curricula, especially in this era of digitalization and the constant emergence of new media. Media consumers need to raise their awareness of interest-driven content and expand their narrow definition of advertising to such content that does not look like traditional advertising but still has a commercial intent.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

This research has several limitations. While the qualitative study generated in-depth insights, it does not provide results that can be generalized to all media consumers. In future research, it would be particularly interesting to assess the reliability of the age effects. Furthermore, the findings are restricted to the media environment in the European country where the research was conducted, despite the fact that companies in many countries use similar content marketing products. Although a variety of content marketing stimuli were used in the study, their selection influenced the results. Further research with different stimuli would broaden the findings and put them on more solid ground. The fact that the interviews were conducted by master’s students in communication science can also be considered a limitation of the study due to their limited experience and different levels of interviewing skills. Another limitation is the assessment of (new) media literacy. Because the questions assessing participants’ media literacy were asked after their perception and evaluation of the stimuli, their answers were likely influenced by what was discussed before. Future research should separate individuals’ self-assessment of media literacy, or even apply an objective measure for it, from the other questions regarding the identification of promotional content.

Acknowledgements

An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the EUPRERA Congress 2022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lina Stürmer

Lina Stürmer (M.A., University of Vienna) is a research associate at the University of Vienna’s Department of Communication, where she is a member of the Corporate Communication Research Group. Her research interests include strategic communication, content strategies and the blurring of boundaries between journalism, advertising and public relations.

Sabine Einwiller

Sabine Einwiller (PhD, University of St. Gallen) is the professor of public relations research at the University of Vienna’s Department of Communication, where she heads the Corporate Communication Research Group. In her research she is mainly interested in integrated communication management and in the effects of corporate communication on their stakeholders. In particular, her research focuses on the strategic management of contents, the effects of negative publicity and crisis communication on corporate reputation and employee communication.

References

- Amazeen, M. A., and A. R. Muddiman. 2018. “Saving Media or Trading on Trust? The Effects of Native Advertising on Audience Perceptions of Legacy and Online News Publishers.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 176–195. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1293488.

- Amazeen, M. A., and B. W. Wojdynski. 2020. “The Effects of Disclosure Format on Native Advertising Recognition and Audience Perceptions of Legacy and Online News Publishers.” Journalism 21 (12): 1965–1984. doi:10.1177/1464884918754829.

- Anani-Bossmann, A., and S. A. A. Obeng. 2022. “Corporate Allies or Adversaries: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Public Relations and Marketing Among Ghanaian Practitioners.” Journal of Marketing Communications 1–18. doi:10.1080/13527266.2022.2105932.

- Aufderheide, P. 1993. Media Literacy: A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. Queenstown, MD: Aspen Institute, Communications and Society Program. Accessed 16 March 2022. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED365294

- Baetzgen, A., and J. Tropp. 2013. “‘Owned Media’: Developing a Theory from the Buzzword.” Studies in Media and Communication 1 (2): 1–10. doi:10.11114/smc.v1i2.172.

- Balasubramanian, S. K. 1994. “Beyond Advertising and Publicity: Hybrid Messages and Public Policy Issues.” Journal of Advertising 23 (4): 29–46. doi:10.1080/00913367.1943.10673457.

- Belanche, D. 2019. “Ethical Limits to the Intrusiveness of Online Advertising Formats: A Critical Review of Better Ads Standards.” Journal of Marketing Communications 25 (7): 685–701. doi:10.1080/13527266.2018.1562485.

- Boerman, S. C., E. A. van Reijmersdal, and P. C. Neijens. 2012. “Sponsorship Disclosure: Effects of Duration on Persuasion Knowledge and Brand Responses.” The Journal of Communication 62 (6): 1047–1064. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01677.x.

- Brehm, J. W. 1966. A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Brehm, S. S., and J. W. Brehm. 1981. Psychological Reactance: A Theory of Freedom and Control. New York: Academic Press.

- Cervi, L., O. Paredes, and J. M. Pérez Tornero. 2010. “Current Trends of Media Literacy in Europe: An Overview.” International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence 1 (4): 1–9. doi:10.4018/jdldc.2010100101.

- Chen, D. T., J. Wu, and Y. M. Wang. 2011. “Unpacking New Media Literacy.” Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics 9 (2): 84–88.

- De Pelsmacker, P., and P. C. Neijens. 2012. “New Advertising Formats: How Persuasion Knowledge Affects Consumer Responses.” Journal of Marketing Communications 18 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1080/13527266.2011.620762.

- Ducoffe, R. H. 1995. “How Consumers Assess the Value of Advertising.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 17 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/10641734.1995.10505022.

- Eagle, L. 2007. “Commercial Media Literacy: What Does It Do, to Whom—and Does It Matter?” Journal of Advertising 36 (2): 101–110. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367360207.

- Flick, U. 2014. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Florès, L., B. Müller, M. Agrebi, and J. L. Chandon. 2008. “The Branding Impact of Brand Websites: Do Newsletters and Consumer Magazines Have a Moderating Role?” Journal of Advertising Research 48 (3): 465–472. doi:10.2501/S0021849908080471.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts.” The Journal of Consumer Research 2 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1086/209380.

- Helfferich, C. 2011. Die Qualität Qualitativer Daten: Manual Für Die Durchführung Qualitativer Interviews [The Quality of Qualitative Data: Manual for Conducting Qualitative Interviews]. 4th ed. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Hobbs, R. 2013. “The Blurring of Art, Journalism, and Advocacy: Confronting 21st Century Propaganda in a World of Online Journalism.” I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society 8 (3): 625–637.

- Kaikati, A. M., and J. G. Kaikati. 2004. “Stealth Marketing: How to Reach Consumers Surreptitiously.” California Management Review 46 (4): 6–22. doi:10.2307/41166272.

- Kendrick, A., and J. A. Fullerton. 2021. “Can US Advertising Students Recognize an Ad in Editorial’s Clothing (Native Advertising)? A Partial Replication of the Stanford “Evaluating Information” Test.” Journal of Marketing Communications 27 (2): 207–228. doi:10.1080/13527266.2019.1655086.

- Kim, B.-H., Y. Pasadeos, and A. Barban. 2001. “On the Deceptive Effectiveness of Labeled and Unlabeled Advertorial Formats.” Mass Communication and Society 4 (3): 265–281. doi:10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_02.

- Kitchen, P. J., and D. Moss. 2006. “Marketing and Public Relations: The Relationship Revisited.” Journal of Marketing Communications 1 (2): 105–106. doi:10.1080/13527269500000012.

- Koc, M., and E. Barut. 2016. “Development and Validation of New Media Literacy Scale (NMLS) for University Students.” Computers in Human Behavior 63: 834–843. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.035.

- Koch, T., B. Viererbl, and C. Schulz-Knappe. 2021. “How Much Journalism is in Brand Journalism? How Brand Journalists Perceive Their Roles and Blur the Boundaries Between Journalism and Strategic Communication.” Journalism 0 (0): 1–18. doi:10.1177/14648849211029802.

- Kuckartz, U. 2014. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software. London: SAGE Publications, Limited. doi:10.4135/9781446288719.

- Lin, T. B., J. Y. Li, F. Deng, and L. Lee. 2013. “Understanding New Media Literacy: An Explorative Theoretical Framework.” Educational Technology & Society 16 (4): 160–170.

- Lou, C., and Q. Xie. 2021. “Something Social, Something Entertaining? How Digital Content Marketing Augments Consumer Experience and Brand Loyalty.” International Journal of Advertising 40 (3): 376–402. doi:10.1080/02650487.2020.1788311.

- Malmelin, N. 2010. “What is Advertising Literacy? Exploring the Dimensions of Advertising Literacy.” Journal of Visual Literacy 29 (2): 129–142. doi:10.1080/23796529.2010.11674677.

- Park, H., S. Kim, and J. Lee. 2020. “Native Advertising in Mobile Applications: Thinking Styles and Congruency as Moderators.” Journal of Marketing Communications 26 (6): 575–595. doi:10.1080/13527266.2018.1547918.

- Pérez Tornero, J. M. 2006. Current Trends on Media Literacy in Europe: Approaches – Existing and Possible – to Media Literacy. Accessed 20 May 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271505667_Current_trends_on_Media_Literacy_in_Europe_Approaches_-_existing_and_possible_-_to_media_literacy

- Potter, W. J. 1998. Media Literacy. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Pulizzi, J. 2012. “The Rise of Storytelling as the New Marketing.” Public Research Quarterly 28 (2): 116–123. doi:10.1007/s12109-012-9264-5.

- Rozendaal, E., M. Buijzen, and P. Valkenburg. 2010. “Comparing Children’s and Adults’ Cognitive Advertising Competences in the Netherlands.” Journal of Children and Media 4 (1): 77–89. doi:10.1080/17482790903407333.

- Rozendaal, E., M. A. Lapierre, E. A. van Reijmersdal, and M. Buijzen. 2011. “Reconsidering Advertising Literacy as a Defense Against Advertising Effects.” Media psychology 14 (4): 333–354. doi:10.1080/15213269.2011.620540.

- Taiminen, K., V. Luoma-Aho, and K. Tolvanen. 2015. “The Transparent Communicative Organization and New Hybrid Forms of Content.” Public Relations Review 41 (5): 734–743. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.06.016.

- Tutaj, K., and E. A. van Reijmersdal. 2012. “Effects of Online Advertising Format and Persuasion Knowledge on Audience Reactions.” Journal of Marketing Communications 18 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/13527266.2011.620765.

- van Reijmersdal, E. A., M. L. Fransen, G. van Noort, S. J. Opree, L. Vandeberg, S. Reusch, F. van Lieshout, and S. C. Boerman. 2016. “Effects of Disclosing Sponsored Content in Blogs: How the Use of Resistance Strategies Mediates Effects on Persuasion.” The American Behavioral Scientist 60 (12): 1458–1474. doi:10.1177/0002764216660141.

- van Reijmersdal, E. A., P. C. Neijens, and E. G. Smit. 2010. “Customer Magazines: Effects of Commerciality on Readers’ Reactions.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 32 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1080/10641734.2010.10505275.

- Weitzl, W. J., J. Seiffert-Brockmann, and S. Einwiller. 2020. “Investigating the Effects of Sponsorship and Forewarning Disclosures on Recipients’ Reactance.” Communications 45 (3): 282–302. doi:10.1515/commun-2019-0113.

- Wojdynski, B. W. 2016. “The Deceptiveness of Sponsored News Articles: How Readers Recognize and Perceive Native Advertising.” The American Behavioral Scientist 60 (12): 1475–1491. doi:10.1177/0002764216660140.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and N. J. Evans. 2016. “Going Native: Effects of Disclosure Position and Language on the Recognition and Evaluation of Online Native Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 45 (2): 157–168. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1115380.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and N. J. Evans. 2020. “The Covert Advertising Recognition and Effects (CARE) Model: Processes of Persuasion in Native Advertising and Other Masked Formats.” International Journal of Advertising 39 (1): 4–31. doi:10.1080/02650487.2019.1658438.

- Wojdynski, B. W., and G. J. Golan. 2016. “Native Advertising and the Future of Mass Communication.” The American Behavioral Scientist 60 (12): 1403–1407. doi:10.1177/0002764216660134.