ABSTRACT

This study draws on the Gender Schema Theory, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Uses and Gratifications Theory (U&G), and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) to explore how gender moderates the relationship between extreme-context perception and user intentions on Instagram for fashion brands, drawing on the COVID-19 pandemic as an example of extreme context. Specifically, our study context concerns social media users in West Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. Through a time-lagged online survey, the data of 310 Instagram users based in Uganda and Nigeria were obtained and subsequently analysed using a variance-based structural equation modelling. Our analysis supports previously reported results in the literature by demonstrating the positive effects of extreme-context perception on intentions to follow and recommend fashion brands on Instagram. Furthermore, our results present new evidence that gender moderates extreme-context perception effects, such that men are significantly more likely to develop higher usefulness, enjoyment, satisfaction and intentions to recommend and follow fashion brands on Instagram. This empirical investigation expands our knowledge of social media use by demonstrating the moderating role of gender regarding the way extreme-context perception affects consumer behaviour towards fashion brands on social media.

1. Introduction

An extreme context is a situation characterised by high uncertainty, risk, and complexity levels, where conventional approaches and strategies may be inadequate or insufficient (Mahmoud et al. Citation2023). In these situations, individuals, organisations, and societies are often pushed to adapt rapidly, displaying resilience and innovation to navigate the challenges (Rapaccini et al. Citation2020). Wars and pandemics serve as prime examples of extreme contexts, as they can have widespread and far-reaching consequences, necessitating quick decision-making, significant resource mobilisation, and the development of novel solutions to mitigate their impacts (Mahmoud et al. Citation2022). The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies an extreme context from a marketing and consumer perspective, as it introduced unprecedented levels of uncertainty, unpredictability, and interconnectedness to the business landscape (Golan, Jernegan, and Linkov Citation2020). The rapid global spread of the virus necessitated immediate adjustments to consumer behaviours, preferences, and expectations, profoundly affecting the strategies and tactics of marketers (Mahmoud, Joan and Daniel et al. Citation2021; Mahmoud, Dieu and Nicholas et al. Citation2021). Brick-and-mortar businesses faced abrupt closures, driving a surge in e-commerce and necessitating a swift digital transformation (OECD Citation2020). Marketers had to navigate the delicate balance between addressing the crisis's emotional impact on consumers and promoting their products or services (Balis Citation2020). The pandemic also accelerated the importance of corporate social responsibility and purpose-driven marketing, with consumers increasingly demanding that businesses demonstrate empathy, authenticity, and a commitment to social good (Zhao Citation2021). In this extreme context, flexibility, agility, and innovation became vital for survival and success as traditional marketing paradigms were upended and consumer priorities shifted dramatically (Sneader, Sternfels and Robert Citation2020).

Therefore, the recent COVID-19 pandemic profoundly changed the way people, particularly consumers, engage with social media platforms (Mason, Narcum, and Mason Citation2021). Studies show that due to globally implemented government-mandated lockdown measures, people spent more time on social media when compared to pre-pandemic levels (Cui et al. Citation2022). The increased use of social media during the pandemic has resulted in increased reliance on social media platforms for online shopping (Johnstone and Lindh Citation2022) and brand comparisons (Miah et al. Citation2022). One such platform is Instagram, with over 1.21 billion monthly active users in 2021, estimated to increase to 1.44 billion in 2025 (Insider Intelligence Citation2022). The widespread usage of Instagram affects preferences and influences consumers’ online purchasing behaviours (Djafarova and Bowes Citation2021). One of the primary features of social media platforms, such as Instagram, is the ability for people to share information worldwide. Social media describes interactive, computer-mediated technologies that facilitate, inter alia, the sharing of ideas and information via virtual communities and networks (Tuten and Hanlon Citation2022). From a marketing communication perspective, social media has allowed brand owners and existing users to spread word-of-mouth messages to new prospective consumers (Tuten Citation2022). Such sharing of relevant information is of immense value to both the brand owner and the consumer. The utility to the brand owner is immense, considering positive word-of-mouth messaging is a cost-effective marketing tool for creating brand awareness and purchase intention (Tuten Citation2022; Tuten and Hanlon Citation2022). The value to consumers is also significant since online platforms, such as Instagram in particular, provide a highly visual medium upon which to share brand-related content for discussion or peer-to-peer selling (Bianchi Citation2021). Notably, Instagram has witnessed swings in popularity between men and women, with male users bridging the usage gap compared to females recently (c.f. LSE Citation2017; Statista Citation2022a). Accordingly, Instagram serves as an important context for this study. In particular, this study explores consumers’ intentions to follow or recommend fashion brands using the Instagram platform in West Africa as an outcome of the interaction between COVID-19 perception and user’s gender. This region represents a suitable empirical setting for the study for several reasons. First, as Gillwald et al. (Citation2019) stipulate, the cost of phone calls and SMS messaging in Africa is prohibitively expensive. Second, penetration rates for Instagram in nations like Nigeria have reached 25 per cent (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, West Africa provides a unique and interesting context to explore this research agenda for additional reasons. Specifically, the relationships among perceptions (i.e., perceived usefulness and enjoyment), overall attitude (i.e., satisfaction), and behavioural intentions (i.e., intentions to follow and recommend) as well as the moderating role of generational cohorts, were established in Sub-Saharan Africa prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021, Citation2021). What sets this study apart is its novel investigation into gender as a moderator of extreme-context perceptions such as pandemics on the behavioural intentions towards fashion brands on social media, specifically on the Instagram platform.

The domain of social media marketing has been empirically evaluated in a number of previous studies (Tuten and Hanlon Citation2022). While numerous related associations have been examined in the literature, word-of-mouth communication between online users on social media platforms has been at the centre of much of this research (Delafrooz, Rahmati, and Abdi Citation2019; Eisingerich et al. Citation2015). What is less understood, however, is examining potential moderators of the antecedents to recommend or follow brands on social media platforms as consequences of the perceptions of extreme contexts like pandemics and warzones (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021, Citation2021). This gap in understanding indicates a lack of knowledge regarding how consumers connect with brands and communicate their preferences to others within such settings. Our hypothetical model consolidates relevant insights from several cognitive and behavioural perspectives, such as the TAM, U&G, and SCT theories, to examine the relationship between COVID-19 perceptions and gender-tailored consumer behaviours. In doing so, we extend the relevance of these theories and address the gap in the literature pertaining to the user’s gender as a moderator of pandemic perception effects on consumers’ intentions to recommend or follow fashion brands on Instagram. Fashion brands are particularly useful when studying social media trends and usage because fashion trends have been shown to spread easily and fast through social networks (Easley and Kleinberg Citation2010), hence the criticality of the choice of social media channels for marketing communications (Anselmsson and Tunca Citation2019). Importantly, previous research has demonstrated that high levels of brand commitment motivate consumers to communicate their views and preferences and incentivise them to engage with particular brands in their online pursuits (Wolny and Mueller Citation2013). However, there is presently little understanding regarding the potential relevance of gender in related activities and interactions, whereas gender has been found relevant to many other consumer-oriented behaviours (Cara, Greaves, and Graham Citation2016). The scope of this study is limited to a sub-Saharan geographical context and the study of fashion brands. Fashion brands are known to exhibit high consumer involvement, implying greater cognitive engagement and evaluation (Khare and Rakesh Citation2010). This view is supported by extant research, which posits that the connection between fashion brands and the high level of consumer involvement reflects the link between fashion conceptualisation and a consumer’s personality and cognitive bent (Bloch Citation1981; Hepner, Chandon, and Bakardzhieva Citation2020; Kapferer and Laurent Citation1985). Accordingly, our study aims to address this limitation, and we ask the following research question: Does gender moderate the effects of pandemic perception on consumers’ intentions to follow and/or recommend fashion brands on Instagram? In other words, this study is set to examine the moderating role of gender regarding extreme-context perceptions (drawing on the COVID-19 pandemic as an example) and the consequent intentions to follow or recommend fashion brands on Instagram conceptually and empirically developed and examined in the work of Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio (Citation2017), Mahmoud, Hack-Polay, et al. (Citation2021) and Mahmoud, Ball, et al. (Citation2021). Achieving the study aim and objectives is suggested to benefit both practitioners and scholars, such that answering the research questions can help marketers deliver more effective and efficient brand communications in extreme contexts, and scholars challenge existing and future theoretical frameworks amidst the dynamics imposed by such settings. In summary, the research context is unique due to its geographical focus, exploration of extreme contexts, emphasis on gender as a moderating variable, specific focus on the Instagram platform, integration of multiple complex factors, and a particular concentration on the fashion industry. These elements collectively contribute to making this study novel and original, addressing a gap in the existing literature and providing new insights into the field of marketing and social media engagement.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we provide a theoretical foundation for our study upon which we propose a research model and hypotheses for empirical investigation. We then address the methodology used in our study before revealing the results and providing discussion and suggestions for future work in this domain.

2. Theoretical foundations and hypothetical model

Social media usage during pandemic time

Within the framework of our study and the Gender Schema Theory (Bem Citation1981), we segment gender as either male or female individuals. COVID-19 perceptions are defined as individuals’ subjective assessment of their personal concerns related to the negative consequences of the pandemic (Mahmoud et al. Citation2023). Additionally, we define the remaining constructs as follows. Perceived usefulness is defined as the extent to which a specific product associates with users’ identified goals (Davis Citation1989; Davis, Bagozzi, and Warshaw Citation1992). Perceived enjoyment indicates the degree of fun, relaxation, mental stimulation, and pleasure that consumers experience as a consequence of their interaction with social media (Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio Citation2017). Perceived satisfaction refers to a pleasant experience with social media that consumers perceive as satisfactory (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021). Intentions to follow and intentions to recommend indicate consumers’ inclination to follow a particular Instagram account and the likelihood of a positive referral of related content (Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio Citation2017; Mahmoud et al. Citation2021).

The impact of COVID-19 on social network usage has been remarkable (Sashittal and Jassawalla Citation2021; Sashittal, Jassawalla, and Sachdeva Citation2022). As more and more people were asked to stay at home, social network use skyrocketed to stay connected with family and friends and conduct work-related activities and interactions (Tibbetts et al. Citation2021). A shift towards consumers’ decision-making process on social commerce platforms was observed, with online trust and perceived risk playing a key role (Lăzăroiu et al. Citation2020). The use of these networks to share news, update statuses, upload photos, and share ideas has become part of our everyday life (Tsao et al. Citation2021). Pandemic-related developments and the consequent distancing measures further increased the emphasis placed on using these networks to stay informed, conduct professional activities, and engage in events happening worldwide. This also reflects the altered consumer attitudes, sentiments, and behaviours related to COVID-19, including changes in retail purchasing behaviour (Smith and Machova Citation2021). Social networks have become an invaluable tool during this time, allowing us to stay connected even when physical contact is not an option (Wang, Hao, and Sundahl Platt Citation2021; Wasserman et al. Citation2020).

During the pandemic, brand owners have also modified their social media tactics and practices, often adopting a more empathetic approach to content creation, thus shifting away from their prior preferences to post information intended to mock and/or undermine competitors (CBS NEWS Citation2020; Dubbelink, Herrando, and Constantinides Citation2021). Furthermore, instead of posting content designed to entertain or be helpful, brands have frequently posted messages of solidarity, as well as public service announcements that leverage brand image into urging consumers to comply with preventative measures, such as facemask wearing, hand washing, or social distancing (Ragavan Citation2020). Brand owners have also developed announcements intended to raise awareness of their CSR efforts (Ragavan Citation2020; Raimo et al. Citation2021). Consumer attitudes towards new models, such as slow fashion, swapping, and clothes rent in the fashion industry, and their willingness to support them have been evident in this shift, especially among the younger generations (Mohr, Leonora, and Ali Citation2022; Musova et al. Citation2021). Accordingly, in their efforts to navigate the global health crisis, successful brands focused more on consumer engagement and less on promotional efforts on social media platforms (Mundel and Yang Citation2021; Salzano Citation2020). As such, in an environment rife with misinformation, it appears that the brands that are able to establish relationships with consumers are best positioned to capitalise on social media as they provide a more reliable and, therefore, trusted source of information (Salzano Citation2020).

To understand these patterns, we draw from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Uses and Gratifications Theory (U&G), and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). The TAM provides a basis for understanding how perceived usefulness and enjoyment drive social media interaction (Davis Citation1989), while U&G sheds light on why people choose specific media to satisfy various needs (Elihu, Blumler, and Gurevitch Citation1973). The SCT adds a psychological perspective, explaining how individuals acquire and maintain behaviour while considering social environment factors (Bandura Citation1986). These frameworks synergistically enhance our understanding of consumer interactions and engagement with social media platforms during the pandemic.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the disruptions to users’ and brands’ social media habits reinforce the need to examine the accuracy and generalisability of prior research that examines consumer interactions on social media platforms (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021). This need is particularly pertinent in light of recent findings that establish a correlation between consumers’ perceived usefulness of information, their enjoyment of social media content, and subsequent intentions to follow and recommend social media accounts (Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio Citation2017). Moreover, COVID-19 perception has been found to positively predict the enjoyment and usefulness of consumed online content (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021). Given the previously outlined shift in online tactics by brand owners, COVID-19 perception effects have translated to a higher level of satisfaction with fashion brand accounts on Instagram and, hence, greater intention to follow and recommend those accounts (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021).

Gender as a moderator

Applying Gender Schema Theory (Bem Citation1981), we further explore the distinctions in male and female behaviour in the context of social media usage. This theory posits that gender-related differences in behaviour stem from societal norms and individual cognitive processing of gender-related information. This approach offers a detailed perspective on gender-based differences by clarifying the psychological processes that may cause diverse patterns of behaviour in men and women.

Contemporary digital marketing research (e.g., Davis, Lang, and San Diego Citation2014; Aramendia-Muneta, Olarte-Pascual, and Hatzithomas Citation2020; Liu Citation2019; Mahmoud et al. Citation2019, Citation2021; Twenge and Martin Citation2020; Zhang et al. Citation2019) emphasises the substantial differences in the way men and women behave in digital realms. This view is also supported by research highlighting that men and women process information differently, especially in the context of stressful situations like a pandemic (Alsharawy et al. Citation2021; Heffner, Vives, and FeldmanHall Citation2021). Men’s tendency to seek out information and data-driven content aligns with the more utilitarian nature of their online behaviour (Margalit Citation2015), which might explain why COVID-19 perception would affect their perceived enjoyment and usefulness differently. Women, on the other hand, are more receptive to the array of information and content provided on social media, making them more influenced by online content such as reviews and ratings (Karatsoli and Nathanail Citation2020).

Furthermore, according to the Digital Marketing Institute, women are more likely to utilise social media prior to making a purchase (Digital Marketing Institute Citation2021). Digital Marketing Institute (Citation2021) further indicates that 78% of women are active on social media, with Snapchat and Instagram being their preferred platforms. This dynamic directly translates to the potency of influencer marketing efforts, as more than fifty per cent of women make purchases as a result of influencer posts. Interestingly, gender research shows that whilst women are likely to spend more time on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic, men are at a higher risk of developing social media addiction (e.g., Ceci Citation2023; Luo, Chen, and Liao Citation2021; Voss et al. Citation2023). Some of these broader gender-related cognitive and behavioural stipulations were documented in the West African regional context during the pandemic. For instance, while men are more consistent users of social media in Western Africa, the percentage of female users in the region has increased from 36% to 39% between 2020 and 2022 (Statista Citation2022b). According to Vermeren (Citation2015), women use social media to establish connections and keep in touch with family or friends. Conversely, men use social networking sites to obtain the data they need to gain influence, whereby social networking sites are utilised to conduct research, accumulate useful contacts, and eventually boost their overall status (Vermeren Citation2015). Combining the Gender Schema Theory and the documented behavioural patterns helps us understand that the relationship between COVID-19 perception and social media’s perceived enjoyment and usefulness may be shaped differently for men and women.

Accordingly, gender differences are likely to influence how COVID-19 perception affects consumers’ perceived enjoyment, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, intention to follow, and intention to recommend fashion brands via Instagram. This argument, alongside the results reported in previous research (Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio Citation2017; Mahmoud et al. Citation2021, Citation2021) and reports (e.g., Burke Citation2021) showing men shopping online more than women during COVID-19.

Given the above discussion and exploration of the literature, we can develop specific hypotheses () to guide our research.

As discussed above, research has highlighted gender differences in the utilisation and enjoyment of social media platforms (Szell and Thurner Citation2013), with men often engaging in more utilitarian and information-seeking activities (Margalit Citation2015; Zhang and Pennacchiotti Citation2013). During the pandemic, men’s focus on data-driven content might lead to a distinct response to online-shared content (Alsharawy et al. Citation2021; Heffner, Vives, and FeldmanHall Citation2021). Hence, men’s perceived enjoyment may be influenced differently by the COVID-19 perception compared to women. Therefore, we hypothesise:

H1:

User’s gender will moderate the relationship between COVID-19 perception and the perceived enjoyment of fashion brand accounts on Instagram, such that men are more likely to have higher levels of enjoyment as a result of COVID-19 perception than women.

Men’s inclination to seek out useful and practical information aligns with previous findings regarding the utilitarian nature of their online behaviour (Margalit Citation2015). For example, research has shown that men are more likely to use social media to seek information, while women use social platforms to connect with people (Muscanell and Guadagno Citation2012). The unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic might enhance the perceived usefulness of specific content for men, reflecting their information-seeking tendencies (Alsharawy et al. Citation2021; Vermeren Citation2015). Thus, we put forward Hypothesis 2:

H2:

User’s gender will moderate the relationship between COVID-19 perception and the perceived usefulness of fashion brand accounts on Instagram, such that men are more likely to have higher levels of usefulness as a result of COVID-19 perception than women.

Even during the pandemic, men’s reliance on information-driven content on social media (Sirola et al. Citation2021) may translate to greater satisfaction with content that aligns with their informational needs. Given the alterations in brand messaging during the pandemic (Ragavan Citation2020; Salzano Citation2020), men may find the content shared on Instagram more satisfying due to its informational value, hence our following hypothesis:

H3:

User’s gender will moderate the total effects of COVID-19 perception on the satisfaction with fashion brand accounts on Instagram, such that men are more likely to have higher levels of satisfaction as a result of COVID-19 perception than women.

Based on earlier arguments, it is reasonable to assume that men’s natural tendencies towards being intentional, explorative, and assertive would impact their online behaviour. However, the disparities in engagement with digital platforms, such as Instagram, between men and women in West Africa may not only be attributed to natural tendencies or stereotypical gender roles but also are likely influenced by the substantial digital divide that exists in the region, as shown in countries like Uganda (Kwakwa Citation2023). Barriers such as affordability, digital literacy, online harassment, and lack of content targeting women hinder women’s access to and use of digital technologies (OECD Citation2018). Therefore, men’s higher engagement with fashion brand accounts during the COVID-19 pandemic could reflect these underlying socio-economic factors rather than inherent behavioural differences. Considering these arguments, it is anticipated that men in West Africa will show greater engagement with fashion brands on Instagram. They are likely to develop stronger intentions to follow or recommend these brands as a result of COVID-19 perception compared to women. Therefore, we hypothesise the following:

H4:

User’s gender will moderate the total effects of COVID-19 perception on the intention to follow fashion brand accounts on Instagram, such that men are more likely to develop intentions to follow as a result of COVID-19 perception than women.

H5:

User’s gender will moderate the total effects of COVID-19 perception on the intention to recommend fashion brand accounts on Instagram, such that men are more likely to recommend to follow as a result of COVID-19 perception than women.

3. Research methodology

Our research was conducted in Nigeria and Uganda, two nations in West Africa and the data were collected using a time-lagged online survey in the year 2021. The participants were selected using purposive sampling, a procedure suitable for extreme contexts (Mahmoud et al. Citation2020, Citation2023) and time-lagged data collection (Short et al., Citation2002) because they were Instagram users and had engaged with fashion brand pages on Instagram. We notified the participants that participation on two separate occasions would be required to complete the survey. Participants’ contact information (including email addresses and/or WhatsApp numbers) was collected in order to send out the surveys. In addition, the participants were informed that, after finishing the first stage, they would be assigned a unique five-digit identification number that would be required to access the survey in the second step. Participants completed the COVID-19 perception, usefulness, and enjoyment assessments at Time 1.

The second wave of the survey was administered four weeks after the first phase was finished. We chose a four-week time lag because a too-short time lag can make correlations between different variables seem bigger than they really are, while a too-long time lag does the opposite (cf. Ployhart and Vandenberg Citation2009). A similar approach was used in prior studies (e.g., Yam et al. Citation2016). Moreover, we chose a four-week time lag based on a specific examination of the context and consumer behaviour related to the nature of engagement with fashion brand pages; a longer duration is particularly relevant to fashion, where trends may take time to resonate with users and influence their opinions.

The sample size was determined using an a-priori sample size calculator tailored to structural equation models (Soper Citation2021). Our data collection was guided by a target sample size of 236 based on the following assumptions: 0.95 power level, 0.30 effect size, six latent variables, and 17 observed variables. The St. John’s University Ethics Committee approved this investigation.

The automatically generated IDs at Time 1 were used to match the responses at Time 1 to the responses at Time 2, making sure that the pairing was done correctly. At Time 2, participants completed measures of satisfaction, intention to recommend, intention to follow, and demographics. Participants in both waves of the study were given a detailed description of the study’s objectives and procedures. They were informed that they were able to contact the investigators anytime to ask questions, express concerns about the survey, or leave the study. Participants’ signatures were not collected since the survey was administered online for both stages of the research. All of the responses to the survey were kept confidential. We promised confidentiality for all participant responses. At Time 1, we distributed 700 questionnaires and obtained 398 responses. At Time 2, we circulated the second wave of questions only to the respondents who had completed Time 1’s surveys. Ultimately, we received 310 completed questionnaires whose data informed our analyses and conclusions. The majority of our sample was aged between 26 and 39 (42%), women (51%) and educated to a university degree level (49%).

For measuring COVID-19 perception, we used the work of Mahmoud, Ball, et al. (Citation2021). For measuring usefulness, enjoyment, satisfaction, intention to follow and intention to recommend fashion brand accounts on Instagram, we used the work of Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio (Citation2017) and Mahmoud, Ball, et al. (Citation2021) as Appendix 1 exhibits. Multi-item and rated on a five-point Likert scale were the characteristics of the measures used in this research. Implementing the Fornell-Lacker Criterion, the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlations with the remaining variables (see ). demonstrates that all constructs had average variance extracted (AVE) values of more than 0.5, correlation coefficient (CR) values between .7 and.9 (Hair et al. Citation2022), and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values less than 3. Common-Method Bias (CMB) was also evaluated and yielded no inner VIFs of concern (see ) since they were all either very close to or less than 3.3 (Kock Citation2015). In light of these findings, we conclude that all of the study measures satisfied the discriminant validity, construct reliability, and convergent validity quality requirements.

Table 1. Discriminant validity test.

Table 2. Outer loadings, VIFs, construct reliability and validity.

Table 3. Inner VIFs.

4. Results

We primarily employ structural equation modelling with the variance-based approach or partial least squares (PLS-SEM) to evaluate study hypotheses. Our decision to use the PLS-SEM method is based on previous research recommending it for analysing predictive models and the increasing prevalence of its application in behavioural and social sciences research (Hair et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, the literature (e.g., Mahmoud et al. Citation2021) indicates that the multivariate normality criterion is unlikely to be met by the majority of data. In addition, a growing body of research (e.g., Pathania, Dixit, and Rasool Citation2022; Phan Citation2023; Mahmoud et al. Citation2023) has validated the use of PLS-SEM for empirical research investigations incorporating non-normality-sensitive data.

To test the hypotheses, we employ SmartPLS 4 to conduct a path analysis. This includes reporting standardised betas (β) for direct effects, unstandardised betas (B) for total indirect effects, and their t-values with bootstrapping performed at 5,000 samples (Preacher and Hayes Citation2008). In addition, Cohen’s f2 was used to evaluate effect sizes, with scores of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicating small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen Citation2013). Finally, PLSpredict is calculated to test the out-of-sample prediction (Hair et al. Citation2019), and the standard root mean square residual (SRMR) is employed to assess the model’s fit to the data (Henseler et al. Citation2014).

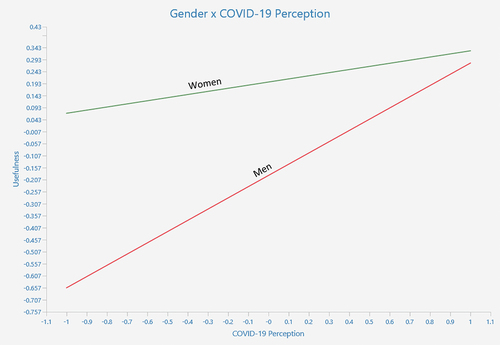

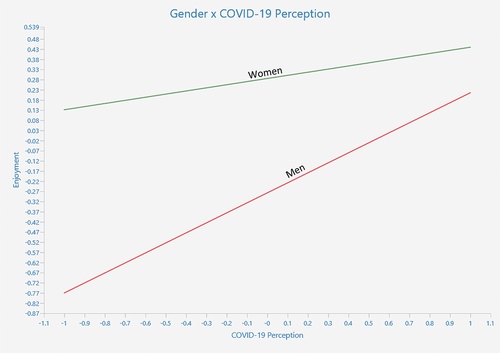

Our statistics show that COVID-19 perception positively predicts both usefulness (β = .481, t = 3.984, f2 > .15) and enjoyment (β = .499, t = 5.044, f2 > .15). Further, both usefulness (β = .471, t = 6.872, f2 > .35) and enjoyment (β = .433, t = 6.586, f2 > .35) positively predict satisfaction that in turn positively predicts intentions to follow (β = .75, t=16.539, f2 > .35) and intentions to recommend (β = .646, t = 14.038, f2 > .35). Also, all unstandardised betas are positive and significant at a probability value less than .001, indicating all of the mediations transmitting COVID-19 perception total effects through usefulness, enjoyment and satisfaction onto intention to follow (B = .337, SD = .082, t = 3.965) and intention to recommend (B = .29, SD = .073, t = 3.83) are significantly full and positive. However, as both show, the direct paths from COVID-19 perception to both usefulness and enjoyment are moderated by gender, leading to COVID-19 perception total effects on both intention to follow and intention to recommend being moderated by gender too. In other words, whilst women are shown to perceive fashion brands’ accounts on Instagram as more useful (β = .387, t = 3.898, f2 > .02) and thus more satisfied (B = .426, SD = .077, t = 5.489) with them and more likely to follow (B = .321, SD = .066, t = 4.81) or recommend them (B = .276, SD = .056, t = 4.866) than men; however, men are more likely to have higher levels of usefulness (β = −.327, t = 2.087, f2 > .02), enjoyment (β = −.342, t=, f2 > .02), satisfaction (B=−.306, SD = .126, t = 2.407) and hence more likely to follow (B=−.231, SD = .098, t=2.311) or recommend (B=−.199, SD = .086, t = 2.271) those accounts because of COVID-19 perception effects. Therefore, we judge H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 as valid (see ).

Figure 4. Hypotheses testing results.

Table 4. Hypotheses testing – direct effects.

Table 5. Hypotheses testing – total indirect effects.

The SRMR value is found to equal .059, less than .08, indicating that our hypothetical model fits our data well. Finally, when compared to the naive LM benchmark (), nearly all of the observed variables in the PLS-SEM evaluation possess lower root mean square error (RMSE) scores, suggesting that the model has a medium to a strong level of predictive power (Hair et al. Citation2019).

Table 6. Plspredict results.

5. Discussion

Brand recommendations on social media are mostly firm (brand owner) driven, aimed at increasing sales via selected e-commerce platforms (Zhang and Pennacchiotti Citation2013). Social media has put brands’ marketing, via word-of-mouth recommendations, in the hands of consumers (Cheung, Chiu, and Lee Citation2011). Consumers now value social media as a brand communication medium more than traditional communication media (Nisar and Whitehead Citation2016), thus giving consumers the power to influence other consumers’ views on brands (Mangold and David Citation2009). Our work adds to the existing literature by examining the overlooked moderating effect of customer gender on online engagement within extreme contexts like pandemics, an aspect not previously emphasised in the literature.

In this study, we investigated the moderating effects of gender regarding the way extreme context variables, such as the COVID-19 pandemic perception, affect consumer behaviour towards fashion brands on social media. In line with existing research that has highlighted gender differences in the utilisation and enjoyment of social media platforms (Szell and Thurner Citation2013), with men often engaging in more utilitarian and information-seeking activities (Margalit Citation2015; Zhang and Pennacchiotti Citation2013), we formulated five hypotheses and tested a model of the moderating role of gender in the effects of COVID-19 perception effects on perceived usefulness, enjoyment of and satisfaction with fashion brands’ accounts on Instagram and the subsequent behavioural intentions of following or recommending those accounts. All five hypotheses formulated theory-based directional predictions about the moderating role of gender in COVID-19 perception pronounced effects on Instagram users’ behavioural intentions building primarily on the work of Casaló, Flavián, and Sergio (Citation2017), Mahmoud, Hack-Polay, et al. (Citation2021) and Mahmoud, Ball, et al. (Citation2021). We hypothesised how men’s focus on data-driven content might lead to a distinct response to online-shared content (Alsharawy et al. Citation2021; Heffner, Vives, and FeldmanHall Citation2021), as well as how the unique circumstances of the pandemic might enhance perceived usefulness for men (Alsharawy et al. Citation2021; Vermeren Citation2015). We also considered how differences in engagement with digital platforms in West Africa may reflect underlying socio-economic factors, including the digital divide in the region (Kwakwa Citation2023; OECD Citation2018). Using variance-based structural equation modelling to conduct path and multigroup analysis, we found full support for all of our hypotheses. Whilst our findings supported previous studies (Mahmoud et al. Citation2021, Citation2021), indicating a positive effect of COVID-19 perception on consumer intention to follow and recommend fashion brands on Instagram, our study offered novel findings – new evidence, demonstrating that gender moderates COVID-19 perception effects such that the women favourability of following or recommending fashion brands’ accounts on Instagram are less affected by that extreme-context perception. Whilst our gender-related findings align with the studies and theories that established rationale for our hypotheses (e.g., Alsharawy et al. Citation2021; Bem Citation1981; Heffner, Vives, and FeldmanHall Citation2021; Kwakwa Citation2023; Margalit Citation2015; Muscanell and Guadagno Citation2012; Sirola et al. Citation2021; Szell and Thurner Citation2013; Vermeren Citation2015), our results represent a deviation from existing models, adding a fresh perspective to the established theories.

Certainly, whilst women are shown to perceive fashion brands’ accounts on Instagram as more useful, thus more satisfied with them and more likely to follow or recommend them than men, women are yet less likely to be affected by COVID-19 to perceive those accounts as useful (H1) or entertaining (H2) and consequently feel satisfied (H3) or develop intentions to follow (H4) or recommend (H5) than men. Specifically, women are significantly less likely to develop higher usefulness, enjoyment or satisfaction with fashion brands and are less likely to recommend and follow fashion brands via visually rich social media as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study contributes a fresh understanding of gender dynamics within social media brand interactions during a global crisis, synthesising and extending the work of previous scholars in the field.

6. Conclusion

Practical implications

We make several notable contributions to the literature. First, our study utilises a unique and valuable empirical setting and provides additional validation to earlier stipulations regarding the consequences of social distancing to consumer engagement and interactions on social media platforms. Second, we present novel insights regarding the role of gender in consumers’ response to extreme socio-economic developments, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent social distancing measures. We specifically demonstrate that women tend to be less affected by the extreme-context circumstances of COVID-19 as it relates to their engagement with fashion brands on social media platforms. This gender-related cognitive and behavioural context concerns differentiated consumer responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study specifically shows a hindered inclination by women to develop higher enjoyment and satisfaction with fashion brands due to social distancing measures. It further indicates that women are less likely to follow and recommend branded products on social media platforms as a consequence of pandemic-related isolation policies. Our study has broad and far-reaching implications for the matters of both policy and practice, with direct relevance to the development of effective policies, organisational strategies, and operating models and protocols. The COVID-19 pandemic was a global crisis with unprecedented consequences for a wide range of social interactions, customer engagement, and broader economic developments. These circumstances provide a unique setting to assess the complex effects of social distancing on consumer behaviour. In this context, our study presents important insights regarding the role of gender in the way consumers respond to social distancing measures, with a focus on their behaviour towards fashion brands on social media platforms. This information can help organisations and brand owners develop effective marketing strategies that consider distancing trends in many markets while factoring in gender-related nuances. For example, whilst online word-of-mouth brand recommendations generated by consumers are largely uncontrollable by the brand owner, brand owners can direct online brand conversations by developing gender-specific marketing communication campaigns. In doing so, brand owners are using a form of consumer advocacy to create, inter alia, purchase intentions via specific online channels. Our study can also aid policymakers in their evaluation of COVID-19 consequences and preparation for future developments that may necessitate the implementation of widespread social distancing initiatives.

Limitations and future directions

Whilst our study’s findings have implications for academics and practitioners, we acknowledge several limitations of our work. First, our West Africa setting provides an interesting yet geographically limiting understanding of consumer behaviour regarding online fashion brand recommendations. Whilst we acknowledge the international reach of social media platforms, such as Instagram, the effectiveness of rapport-building strategies between brand owners and consumers is culturally dependent. It should be adapted to the micro level, especially for continental countries that are culturally diverse. This suggests the need to consider the different cultural contexts to better understand consumers’ behavioural tendencies towards fashion brands. A further limitation centres around the choice of social media platform. We selected Instagram as the sole social media platform in this study. Alternative social media sites such as YouTube offer consumers and brand owners a rich visual experience to develop positive brand perceptions, possibly yielding different results. Indeed, one advantage that YouTube has over alternative social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) is that it does not require consumers to sign up for membership to receive brand recommendations. Finally, our study uses the current COVID-19 pandemic as a backdrop. Whilst the world is still in the grip of COVID-19, much of the world’s population is vaccinated against the effects of COVID-19. Does this alter consumers’ perceptions and the likelihood of recommending or following fashion brands on social media? Moreover, with new extreme contexts developing worldwide (e.g., the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the cost-of-living crisis in Europe), can our result generalise to those extreme settings?

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2023.2278058.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ali B. Mahmoud

Dr. Ali B. Mahmoud is a dual PhD holder in Digital Marketing and Organisational Behaviour and a DLitt candidate at LSBU Business School. Dr Mahmoud is a Visiting Professor of Management in the Peter J. Tobin College of Business at St. John’s University in New York City and a Senior Research Scholar at ResPeo. Dr Mahmoud has published over 70 publications, including books, book chapters and journal articles featured in international journals like European Management Review, Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Marketing Communications, Technovation, Personnel Review, Journal of Brand Management, Journal of Strategic Marketing, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, BMC Public Health, BMC Psychology, Higher Education Quarterly, International Sociology, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management and many others where he reviews and occupies editorial roles too. He has presented his work at leading conferences like the Academy of Marketing Science (AMS), the British Academy of Management (BAM) and the British Educational Research Association (BERA). Dr Mahmoud’s work has won the most cited/impactful article, an award by Wiley, and his work published in European Management Review as well as the Scandinavian Journal of Psychology.

Alexander Berman

Dr. Alexander Berman is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Management at St. John’s University. He holds a BS from Cornell University, an MBA from Boston University, and a Ph.D. from Temple University. Prior to joining academia, Alexander spent over ten years in the financial services industry, working as a member of portfolio management teams at Goldman Sachs and Barings. Alexander is also a founder of BAIS Enterprise, a Registered Investment Advisory firm in New York. Alexander studies entrepreneurship and innovation with a focus on context-specific processes. His research examines the roles of government policy and technological innovation in the formation and sustainability of firms. He also evaluates how linguistic, cultural, cognitive, and geographic contexts relate to consumer behaviour, innovation processes, and entrepreneurial outcomes.

Nicholas Grigoriou

Dr. Nicholas Grigoriou is an experienced lecturer in marketing at Monash University Faculty of Business and Economics, Clayton, VIC, Australia, with a demonstrated history of working in the higher education industry. He is skilled in intercultural communication, analytical skills, research design, lecturing and instructional design. His research interests are focused on marketing and international business.

Konstantinos Solakis

Dr. Konstantinos Solakis holds a PhD in Tourism Marketing and Management as a research fellow at the Marketing, Innovation, Tourism and Sustainability (MITS) Research Group at the University of Seville. Research Interest: Literary Tourism, Tourism Marketing Management and Value Co-Creation.

References

- Alsharawy, Abdelaziz, Ross Spoon, Alec Smith, and Sheryl Ball. 2021. “Gender Differences in Fear and Risk Perception During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689467.

- Anselmsson, Johan, and Burak Tunca. 2019. “Exciting on Facebook or Competent in the Newspaper? Media Effects on consumers’ Perceptions of Brands in the Fashion Category.” Journal of Marketing Communications 25 (7): 720–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1392337.

- Aramendia-Muneta, Maria Elena, Cristina Olarte-Pascual, and Leonidas Hatzithomas. 2020. “Gender stereotypes in original digital video advertising.” Journal of Gender Studies 29 (4): 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2019.1650255.

- Balis, Janet. 2020. Brand marketing through the coronavirus crisis. Harvard Business Review. Accessed May 23. 2023. https://hbr.org/2020/04/brand-marketing-through-the-coronavirus-crisis

- Bandura, Albert. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bem, Sandra Lipsitz. 1981. “Gender Schema Theory: A Cognitive Account of Sex Typing.” Psychological Review 88 (4): 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.88.4.354.

- Bianchi, Anna. 2021. Driving Consumer Engagement in Social Media: Influencing Electronic Word of Mouth. 1st ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Bloch, Peter H. 1981. An Exploration Into the Scaling of Consumers' Involvement With a Product Class. In NA - Advances in Consumer Research, edited by Kent B. Monroe, 61–65. Vol. 8. Ann Abor, MI: Association for Consumer Research.

- Burke, M. 2021. Consumer Trends Report—Men Vs Women Shopping Statistics, Behaviors & Other Trends. Jungle Scout, Accessed December 2. https://www.junglescout.com/blog/men-vs-women-shopping/.

- Cara, Tannenbaum, Lorraine Greaves, and Ian D. Graham. 2016. “Why Sex and Gender Matter in Implementation Research.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 16 (1): 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0247-7.

- Casaló, L. V., C. Flavián, and I. Sergio. 2017. “Antecedents of Consumer Intention to Follow and Recommend an Instagram Account.” Online Information Review 41 (7): 1046–1063.

- CBS NEWS. 2020. Burger King’s Instagram Urges People to Get Takeout — from Other Restaurants. CBS Interactive Inc, Accessed June 29. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/burger-king-offers-instagram-feed-to-independent-restaurants-struggling-with-covid-lockdowns/.

- Ceci, L. 2023. Average Daily Time Spent by Users Worldwide on Social Media Apps from October 2020 to March 2021, by Gender. Statista, Accessed July. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1272876/worldwide-social-apps-time-spent-daily-gender/.

- Cheung, Christy M. K., Pui-Yee Chiu, and Matthew K. O. Lee. 2011. “Online Social Networks: Why Do Students Use Facebook?” Computers in Human Behavior 27 (4): 1337–1343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.028.

- Cohen, Jacob. 2013. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. NY: Routledge.

- Cui, Nan, Nick Malleson, Victoria Houlden, and Alexis Comber. 2022. “Using Social Media Data to Understand the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Urban Green Space Use.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 74:127677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127677.

- Davis, Fred D. 1989. “Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology.” MIS Quarterly 13 (3): 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

- Davis, Fred D., Richard P. Bagozzi, and Paul R. Warshaw. 1992. “Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace1.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 22 (14): 1111–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x.

- Davis, Robert, Bodo Lang, and Josefino San Diego. 2014. “How Gender Affects the Relationship Between Hedonic Shopping Motivation and Purchase Intentions?” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 13 (1): 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1450.

- Delafrooz, Narges, Yalda Rahmati, and Mehrzad Abdi. 2019. “The Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Instagram Users: An Emphasis on Consumer Socialization Framework.” Cogent Business & Management 6 (1): 1606973. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1606973.

- Digital Marketing Institute. 2021. 20 Surprising Influencer Marketing Statistics. Digital Marketing Institute, accessed02 December. https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/20-influencer-marketing-statistics-that-will-surprise-you.

- Djafarova, Elmira, and Tamar Bowes. 2021. “‘Instagram Made Me Buy it’: Generation Z Impulse Purchases in Fashion Industry.” Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services 59:102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345.

- Dubbelink, Sanne I., Carolina Herrando, and Efthymios Constantinides. 2021. “Social Media Marketing as a Branding Strategy in Extraordinary Times: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Sustainability 13 (18). https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810310.

- Easley, D., and J. Kleinberg. 2010. Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World. NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Eisingerich, Andreas B., HaeEun Helen Chun, Yeyi Liu, He Michael Jia, and Simon J. Bell. 2015. “Why Recommend a Brand Face-To-Face but Not on Facebook? How Word-Of-Mouth on Online Social Sites Differs from Traditional Word-Of-Mouth.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 25 (1): 120–128.

- Elihu, Katz, Jay G. Blumler, and Michael Gurevitch. 1973. “Uses and Gratifications Research.” Public Opinion Quarterly 37 (4): 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/268109.

- Gillwald, A., O. Mothobi, A. Ndiwalana, and T. Tusubira. 2019. The State of ICT in Uganda. Research ICT Africa, Accessed June 29. https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019_After-Access-The-State-of-ICT-in-Uganda.pdf.

- Golan M. S., Jernegan L. H., and Linkov I. 2020. Trends and applications of resilience analytics in supply chain modeling: systematic literature review in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Environment Systems and Decisions 40 (2): 222–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-020-09777-w.

- Hair, J., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2022. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). London: SAGE.

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. “When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM.” European Business Review 31 (1): 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203.

- Heffner, Joseph, Marc-Lluís Vives, and Oriel FeldmanHall. 2021. “Anxiety, Gender, and Social Media Consumption Predict COVID-19 Emotional Distress.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8 (1): 140. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00816-8.

- Henseler, J., T. K. Dijkstra, M. Sarstedt, A. Diamantopoulos, D. W. Straub, D. J. Ketchen, J. F. Hair, G. T. M. Hult, and R. J. Calantone. 2014. “Common Beliefs and Reality About Partial Least Squares: Comments.” Rönkkö Evermann (2013) Organizational Research Methods 17 (2): 182–209.

- Hepner, Judith, Jean-Louis Chandon, and Damyana Bakardzhieva. 2020. “Competitive Advantage from Marketing the SDGs: A Luxury Perspective.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 39 (2): 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-07-2018-0298.

- Insider Intelligence. 2022. Number of Instagram Users Worldwide from 2020 to 2025 (In Billions) [Graph]. Statista, Accessed December 2. https://www.statista.com/statistics/183585/instagram-number-of-global-users/.

- Johnstone, Leanne, and Cecilia Lindh. 2022. “Sustainably Sustaining (Online) Fashion Consumption: Using Influencers to Promote Sustainable (Un)planned Behaviour in Europe’s Millennials.” Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services 64:102775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102775.

- Kapferer, Jean-Noel, and Gilles Laurent. 1985. Consumers' Involvement Profile: New Empirical Results. In NA - Advances in Consumer Research, edited by Elizabeth C. Hirschman, and Moris B. Holbrook, 290–295. Vol. 12. Holbrook, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

- Karatsoli, Maria, and Eftihia Nathanail. 2020. “Examining Gender Differences of Social Media Use for Activity Planning and Travel Choices.” European Transport Research Review 12 (1): 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-020-00436-4.

- Khare, Arpita, and Sapna Rakesh. 2010. “Predictors of Fashion Clothing Involvement Among Indian Youth.” Journal of Targeting Measurement & Analysis for Marketing 18 (3): 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2010.12.

- Kock, Ned. 2015. “Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach.” International Journal of E-Collaboration (IJeC) 11 (4): 1–10.

- Kwakwa, V. 2023. Accelerating Gender Equality: Let’s Make Digital Technology Work for All.The World Bank Group, Accessed August 19. https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/accelerating-gender-equality-lets-make-digital-technology-work-all.

- Lăzăroiu, George, Octav Neguriţă, Iulia Grecu, Gheorghe Grecu, and Paula Cornelia Mitran. 2020. “Consumers’ Decision-Making Process on Social Commerce Platforms: Online Trust, Perceived Risk, and Purchase Intentions.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00890.

- Liu, Youmei. 2019. “Gender Difference in Perception and Use of Social Media Tools.” In Handbook of Research on Instructional Systems and Educational Technology, edited by T. Kidd, and L. Morris Jr, 249–262. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- LSE. 2017. Social Media Platforms and Demographics.Accessed December 2. https://info.lse.ac.uk/staff/divisions/communications-division/digital-communications-team/assets/documents/guides/A-Guide-To-Social-Media-Platforms-and-Demographics.pdf.

- Luo, Tao, Wei Chen, and Yanhui Liao. 2021. “Social Media Use in China Before and During COVID-19: Preliminary Results from an Online Retrospective Survey.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 140:35–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.057.

- Mahmoud, Ali B., Joan Ball, Daniel Rubin, Leonora Fuxman, Iris Mohr, Dieu Hack-Polay, Nicholas Grigoriou, and Aziz Wakibi. 2021. “Pandemic Pains to Instagram Gains! COVID-19 Perceptions Effects on Behaviours Towards Fashion Brands on Instagram in Sub-Saharan Africa: Tech-Native Vs Non-Native Generations.” Journal of Marketing Communications 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2021.1971282.

- Mahmoud, A. B., Berman, A., Reisel, William D., Fuxman, L., Grigoriou, N., and Tehseen, S. 2023. International Review of Entrepreneurship 21 (1): 1–26.

- Mahmoud, A. B., Alexander Berman, William D. Reisel, Leonora Fuxman, and Dieu Hack-Polay. 2023. “Examining Generational Differences as a Moderator of Extreme-Context Perception and Its Impact on Work Alienation Organisational Outcomes—Implications for the Workplace and Remote Work Transformation.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12955.

- Mahmoud, Ali Bassam, Nicholas Grigoriou, Leonora Fuxman, Dieu Hack-Polay, Fatina Bassam Mahmoud, Eiad Yafi, and Shehnaz Tehseen. 2019. “Email is Evil! Behavioural Responses Towards Permission-Based Direct Email Marketing and Gender Differences.” Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 13 (2): 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-09-2018-0112.

- Mahmoud, A. B., Nicholas Grigoriou, Leonora Fuxman, and William D Reisel. 2020. “Political Advertising Effectiveness in Wartime Syria.” Media, War & Conflict 13 (4): 375–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635219841356.

- Mahmoud, Ali B., Dieu Hack-Polay, Nicholas Grigoriou, Iris Mohr, and Leonora Fuxman. 2021. “A Generational Investigation and Sentiment and Emotion Analyses of Female Fashion Brand Users on Instagram in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Brand Management 28 (5): 526–544. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00244-8.

- Mahmoud A. B., Reisel W. D., Fuxman L., and Hack‐Polay D. 2022. Locus of control as a moderator of the effects of COVID‐19 perceptions on job insecurity, psychosocial, organisational, and job outcomes for MENA region hospitality employees. European Management Review 19 (2): 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12494.

- Mangold, W. Glynn, and J. Faulds. David. 2009. “Social Media: The New Hybrid Element of the Promotion Mix.” Business Horizons 52 (4): 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.03.002.

- Margalit, Liraz. 2015. Men Systemize. Women Empathize. Psychology Today, Accessed August 18. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/behind-online-behavior/201507/men-systemize-women-empathize.

- Mason, Andrew N., John Narcum, and Kevin Mason. 2021. “Social Media Marketing Gains Importance After Covid-19.” Cogent Business & Management 8 (1): 1870797. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1870797.

- Miah, Md Rukon, Afzal Hossain, Rony Shikder, Tama Saha, and Meher Neger. 2022. “Evaluating the Impact of Social Media on Online Shopping Behavior During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bangladeshi consumers’ Perspectives.” Heliyon 8 (9): e10600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10600.

- Mohr, Iris, Fuxman Leonora, and B. Mahmoud. Ali. 2022. “Fashion Resale Behaviours and Technology Disruption: An In-Depth Review.” In Handbook of Research on Consumer Behavior Change and Data Analytics in the Socio-Digital Era, edited by Pantea Keikhosrokiani, 351–373. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Mundel, Juan, and Jing Yang. 2021. “Consumer Engagement with Brands’ COVID-19 Messaging on Social Media: The Role of Perceived Brand–Social Issue Fit and Brand Opportunism.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 21 (3): 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2021.1958274.

- Muscanell, Nicole L., and Rosanna E. Guadagno. 2012. “Make New Friends or Keep the Old: Gender and Personality Differences in Social Networking Use.” Computers in Human Behavior 28 (1): 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.016.

- Musova, Zdenka, Hussam Musa, Jennifer Drugdova, George Lazaroiu, and Jehad Alayasa. 2021. “Consumer Attitudes Towards New Circular Models in the Fashion Industry.” Journal of Competitiveness 13 (3): 111.

- Nisar, Tahir M., and Caroline Whitehead. 2016. “Brand Interactions and Social Media: Enhancing User Loyalty Through Social Networking Sites.” Computers in Human Behavior 62:743–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.042.

- OECD. 2018. Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate. OECD, Accessed August 19. https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf.

- OECD. 2020. E-commerce in the time of COVID-19. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/e-commerce-in-the-time-of-covid-19-3a2b78e8/

- Pathania, Anjali, Saumya Dixit, and Gowhar Rasool. 2022. “‘Are Online Reviews the New shepherd?’ –Examining Herd Behaviour in Wearable Technology Adoption for Personal Healthcare.” Journal of Marketing Communications 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2022.2140183.

- Phan, Tan, Luc. 2023. “Customer Participation, Positive Electronic Word-Of-Mouth Intention and Repurchase Intention: The Mediation Effect of Online Brand Community Trust.” Journal of Marketing Communications 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2023.2177709.

- Ployhart, Robert E., and Robert J. Vandenberg. 2009. “Longitudinal Research: The Theory, Design, and Analysis of Change.” Journal of Management 36 (1): 94–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352110.

- Preacher, K. J., and A. F. Hayes. 2008. “Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models.” Behavioral Research Methods 40 (3): 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879.

- Ragavan, S. 2020. How Brands are Positioning Their Messages During COVID-19. PRWEEK, Accessed June 29. https://www.prweek.com/article/1678186/brands-positioning-messages-during-covid-19.

- Raimo, Nicola, Angela Rella, Filippo Vitolla, María-Inés Sánchez-Vicente, and Isabel-María García-Sánchez. 2021. “Corporate Social Responsibility in the COVID-19 Pandemic Period: A Traditional Way to Address New Social Issues.” Sustainability 13 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126561.

- Rapaccini M., Saccani N., Kowalkowski C., Paiola M., and Adrodegari F. 2020. Navigating disruptive crises through service-led growth: The impact of COVID-19 on Italian manufacturing firms. Industrial Marketing Management 88:225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.017.

- Salzano, M. 2020. Using Instagram to Build Business in the Age of COVID-19. Floor Covering News, Accessed May. https://www.fcnews.net/2020/04/fcnews-exclusive-using-instagram-to-build-business-in-the-age-of-covid-19/.

- Sashittal, Hemant C., and Avan R. Jassawalla. 2021. “Brands as Personal Narratives: Learning from User–YouTube–Brand Interactions.” Journal of Brand Management 28 (6): 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00248-4.

- Sashittal, Hemant C., Avan R. Jassawalla, and Ruchika Sachdeva. 2022. “The Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer–Brand Relationships: Evidence of Brand Evangelism Behaviors.” Journal of Brand Management. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-022-00301-w.

- Short, Jeremy C., David J. Ketchen, and Timothy B. Palmer. 2002. “The Role of Sampling in Strategic Management Research on Performance: A Two-Study Analysis.” Journal of Management 28 (3): 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800306.

- Sirola, Anu, Markus Kaakinen, Iina Savolainen, Hye-Jin Paek, Izabela Zych, and Atte Oksanen. 2021. “Online Identities and Social Influence in Social Media Gambling Exposure: A Four-Country Study on Young People.” Telematics and Informatics 60:101582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101582.

- Smith, Alison, and Veronika Machova. 2021. “Consumer Tastes, Sentiments, Attitudes, and Behaviors Related to COVID-19.” Analysis and Metaphysics 20:145–158. https://doi.org/10.22381/am20202110.

- Sneader, K., and Sternfels, R. A. 2020. From surviving to thriving: Reimagining the post-COVID-19 return. Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/from-surviving-to-thriving-reimagining-the-post-covid-19-return.

- Soper, Daniel. 2021. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models. Free Statistics Calculators, Accessed February 7. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89.

- Statista. 2022a. Distribution of Instagram Users Worldwide as of January 2022, by Gender [Graph]. Statista, Accessed December 02. https://www.statista.com/statistics/802776/distribution-of-users-on-instagram-worldwide-gender/.

- Statista. 2022b. Distribution of Social Media Users in Western Africa from 2020 to 2022, by Gender. Statista, Accessed December 2. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1326152/distribution-of-social-media-users-in-western-africa-by-gender/.

- Szell, Michael, and Stefan Thurner. 2013. “How Women Organize Social Networks Different from Men.” Scientific Reports 3 (1): 1214. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01214.

- Tibbetts, Maureen, Adam Epstein-Shuman, Matthew Leitao, and Kostadin Kushlev. 2021. “A Week During COVID-19: Online Social Interactions are Associated with Greater Connection and More Stress.” Computers in Human Behavior Reports 4:100133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100133.

- Tsao, Shu-Feng, Helen Chen, Therese Tisseverasinghe, Yang Yang, Li Lianghua, and Zahid A. Butt. 2021. “What Social Media Told Us in the Time of COVID-19: A Scoping Review.” Lancet Digital Health 3 (3): e175–e194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30315-0.

- Tuten, T. L. 2022. Principles of Marketing for a Digital Age. London: SAGE Publications.

- Tuten, Tracy L., and Annmarie Hanlon. 2022. Introduction to Social Media Marketing. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Marketing, edited by Annmarie Hanlon, and Tracy L. Tuten, 3–13. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Twenge, Jean M., and Gabrielle N. Martin. 2020. “Gender Differences in Associations Between Digital Media Use and Psychological Well-Being: Evidence from Three Large Datasets.” Journal of Adolescence 79:91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.018.

- Vermeren, I. 2015.Men Vs. Women: Who is More Active on Social Media?. Brandwatch, Accessed December 2. https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/men-vs-women-active-social-media/.

- Voss, Claire, Phoebe Shorter, Jessica Mueller-Coyne, and Katherine Turner. 2023. “Screen Time, Phone Usage, and Social Media Usage: Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Digital Health 9:20552076231171510. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231171510.

- Wang, Yan, Haiyan Hao, and Lisa Sundahl Platt. 2021. “Examining Risk and Crisis Communications of Government Agencies and Stakeholders During Early-Stages of COVID-19 on Twitter.” Computers in Human Behavior 114:106568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106568.

- Wasserman, Danuta, Miriam Iosue, Anika Wuestefeld, and Vladimir Carli. 2020. “Adaptation of Evidence-Based Suicide Prevention Strategies During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic.” World Psychiatry 19 (3): 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20801.

- Wolny, Julia, and Claudia Mueller. 2013. “Analysis of Fashion consumers’ Motives to Engage in Electronic Word-Of-Mouth Communication Through Social Media Platforms.” Journal of Marketing Management 29 (5–6): 562–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.778324.

- Yam, K. C., R. Fehr, F. T. Keng-Highberger, A. C. Klotz, and S. J. Reynolds. 2016. “Out of Control: A Self-Control Perspective on the Link Between Surface Acting and Abusive Supervision.” Journal of Applied Psychology 101 (2): 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000043.

- Zhang, Xin, Ma Liang, Bo Xu, and Xu. Feng. 2019. “How Social Media Usage Affects employees’ Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention: An Empirical Study in China.” Information & Management 56 (6): 103136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.12.004.

- Zhang, Yongzheng, and Marco Pennacchiotti. 2013. Recommending Branded Products from Social Media. Proceedings of the 7th ACM conference on Recommender systems, Hong Kong, China. https://doi.org/10.1145/2507157.2507170.

- Zhao J. 2021. Reimagining Corporate Social Responsibility in the Era of COVID-19: Embedding Resilience and Promoting Corporate Social Competence. Sustainability 13 (12): 6548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126548.