ABSTRACT

A political brand aims to project a differentiated and identifiable position in the minds of voters. However, there is limited understanding on the envisaged and realised positioning of political ‘party’ brands particularly in under-explored contexts. Therefore, this study investigates the brand positioning of four political ‘party’ brands from an insider (politician) and outsider (voter) perspective in the context of the British Crown Dependency of Jersey. Adopting a qualitative approach, this study conducted semi-structured interviews with politicians-candidates from all four political parties in Jersey and focus group discussions with young voters 18–24 years. Thematic analysis was adopted as part of the analytical strategy. It was revealed internal stakeholders created clear positioning for their political brands grounded on values and visual identity cues rather than grounded on distinct policies. However, the brand positioning of the three of the four political party brands were largely unclear from the standpoint of young voters. The study has implications for academics-practitioners beyond politics. More specifically, this study presents ‘the Political Brand Positioning Toolkit’. The toolkit developed from existing theory and empirical findings represents a systematic framework, which provides guidance on how to position new or existing brands and strategically manage a brand’s envisaged and realised position.

Introduction

Brands are ‘everywhere and everything is a brand … throughout the years, “brand” and “branding” have become so pervasive in the literature and business strategy discourse, it seems that everything thing, even everybody, has become a brand in its/their own right’ (Richelieu Citation2018, 354). Indeed, a brand goes beyond the name of an organisation, product, service, campaign, or person. A brand symbolises a complex collection of values, characteristics, and personality. Further, brands ‘represent promises and quality assurances made by organisations to give their target markets propositions of what they can expect and potentially benefit from their brand offerings’ (Pich Citation2022, 107). Brands are made up of physical and intangible elements, designed, managed, and communicated by organisations and brought to life in the minds of consumers (Aaker Citation1997; Armannsdottir, Pich, and Spry Citation2019; de Chernatony Citation2007; Ronzoni, Torres, and Kang Citation2018).

Brands also have the potential to aid the decision-making process by differentiating their offering against competitors and allow consumers to develop identification and form long-term trusted relationships (Nandan Citation2005; Pich and Spry Citation2019). Further, just as brands can signify membership, and express aspects of a consumer’s personality matching with consumers’ wants and needs, brands can become irrelevant and weak (Balmer and Liao Citation2007; Richelieu Citation2018). Successful brands should be consistent, relevant, authentic, and trustworthy, communicate clear identities and leave no room for ambiguity (Nandan Citation2005; Needham and Smith Citation2015). To build and maintain strong brands, organisations must continually explore and manage current associations and perceptions in the mind of multiple stakeholders to keep control and safeguard brands from becoming meaningless, irrelevant, and disconnected from its target market (Pich and Spry Citation2019). Therefore, after briefly presenting the advantages of branding, it is not surprising that commercial branding concepts, theories and frameworks have been transferred to multiple settings and contexts including politics.

It is widely accepted that political parties, candidates-politicians, party leaders, election campaigns, political groups, policy initiatives and legislators can be conceptualised as political brands (Marland, Lewis, and Flanagan Citation2017; Pich Citation2022; Simons Citation2016). However, existing research has tended to focus on ‘established’ political party brands rather than ‘new-emerging’ political brands or political brands in dynamic political systems (Marland, Lewis, and Flanagan Citation2017; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Pich Citation2022). Irrespective of the typology, political brands act as short-cut mechanisms to communicate desired positioning to a multitude of stakeholders such as supporters, activists, the media, employees and most importantly voters (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). In addition, political brands are designed to act as points of differentiation from political rivals in terms of policy initiatives, ideology, and values (Pich Citation2022). Furthermore, political brands are developed to encourage identification and support and signify a series of promises and desired aspirations, which they will enact if successful on polling day (Needham and Smith Citation2015; Rutter, Hanretty, and Lettice Citation2015). Needham (Citation2005) developed six attributes which she argued formed the basis of successful political brands: simplicity; uniqueness; reassurance; aspiration; values; and credibility. However, political brands are difficult to create and manage (Armannsdottir, Pich, and Spry Citation2019).

One area that has seen limited attention is political brand positioning. Political brand positioning signifies how a political brand ‘wants to be seen’ and designed to illustrate relevance by addressing the wants and needs of stakeholders (Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). Further, political strategists aim to project a clear, relatable, and comprehensible position in the minds of voters (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Pich Citation2022; Smith and French Citation2009). However, there continues to be a paucity of research dedicated to investigating the envisaged and realised positioning of political brands (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Smith Citation2005). This is supported by explicit calls for further understanding on political brand positioning (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Marland, Lewis, and Flanagan Citation2017; Pich Citation2022).

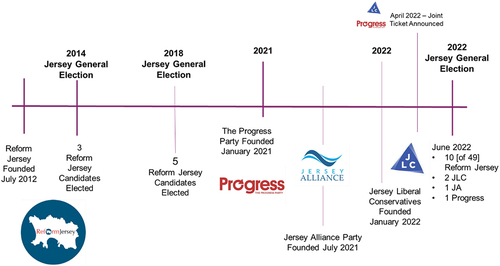

To contextualise this study, the research focused on the Channel Island of Jersey, a British Crown Dependency. The island’s General Election was contested on the 22nd of June 2022 (Pich and Reardon Citation2023). Prior the 2022 General Election, Jersey had four political parties – Jersey Alliance (formed 2021), Reform Jersey (formed 2014), Jersey Liberal Conservatives (formed 2021) and the Progress Party of Jersey (formed 2021). Therefore, Jersey’s four political parties served as appropriate brands to frame this study, as three of the four brands were newly created ahead of the 2022 General Election, and Jersey’s 49 seat Parliament was traditionally dominated by independent politicians (Pich and Reardon Citation2023). Subsequently, this study aimed to explore the brand positioning of political ‘party’ brands in the context of the British Crown Dependency of Jersey from a multi-stakeholder perspective. First, we present the theoretical underpinning for this paper and present our objectives. Second, we put forward our methodology. This is followed by our findings and then discussion section. We conclude with clear implications for theory and practice followed by limitations and areas for further research.

Political brand positioning

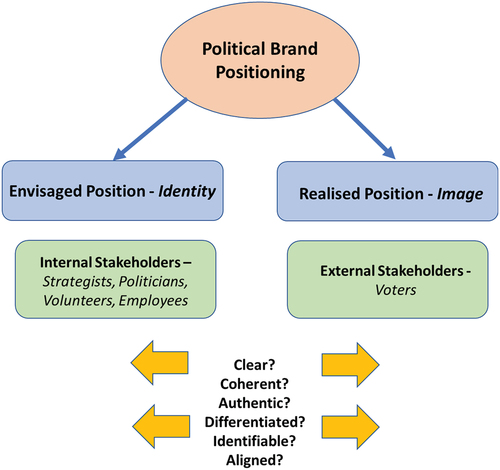

Political strategists aim to project a clear, relatable, and comprehensible position in the minds of voters (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Pich Citation2022; Smith and French Citation2009). Transferred from the commercial branding literature, brand positioning is defined as the ‘act of designing the company’s offering and image to occupy a distinctive place in the mind of the target market’. Successful positioning allows political brands to communicate clear points of differentiation compared to competitors. Political brand positioning signifies how the political brand ‘wants to be seen’ and designed to illustrate relevance by addressing the wants and needs of stakeholders (Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). However, political brand positioning is a complex ‘two-way communication process’ involving the producer-creator (insider the organisation), and consumer (outside the organisation)). Nevertheless, envisaged, and realised positioning can differ (Pich Citation2022). Therefore, it is the role of strategists to manage aligning the two related yet distinct perspectives (Armannsdottir, Pich, and Spry Citation2019; Newman Citation1999). Aligned political brands have the potential to be perceived as credible, trustworthy, authentic, and united, which can lead to greater success at the ballot box (Smith and French Citation2009). Ultimately, positioning has a ‘central place within political branding theory as it provides insight into the political brand’s product offering; responds to the wants and needs of voters; and enables strategists to create a competitive differentiation in the political marketplace’ (Pich Citation2022, 121).

Research on the positioning of political brands has received some attention. Existing research has tended to focus on the measurement of how political brands are positioned (positioning scales) or appraisal of strategies and communication tactics implemented by political brands during election campaigns (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Collins and Butler Citation2002; Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Johnson Citation1971; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Norris et al. Citation1999, O’Shaughnessy and Baines, Citation2009; Smith Citation2005; Smith and French Citation2009). For example, Smith (Citation2005), examined the positioning strategies of the three main political parties (Labour, Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats) during the 2005 UK General Election. It was found from the beginning of the campaign that all three political brands faced political positioning ‘dilemmas’ (Smith Citation2005, 1137) and this included the UK Conservative Party brand. The Conservative Party brand faced the internal problem of appeasing not only the previously silenced pro-European wing of the party but also the core anti-European constituency (Smith Citation2005). In addition, the UK Conservative party failed to develop a clear point of differentiation from political competitors, especially the Labour brand. For example, the Conservatives were perceived as an opposition party, not credible, and a ‘nasty’ uncaring party for the ‘rich and privileged’ (Smith Citation2005). Furthermore, Smith (Citation2005), concluded they had failed to produce an integrated long-term strategy and needed to develop new approaches to address the political brand’s dilemmas.

Subsequently, it is important to routinely audit and track the positioning of a political brand as this may reveal coherency or misalignment of envisaged and realised positioning (Pich Citation2022). This will allow strategists to respond and develop strategies to maintain alignment or devise repositioning strategies (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Collins and Butler Citation2002; Pich Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). Nevertheless, there continues to be a paucity of research dedicated to investigating the envisaged and realised positioning of political brands (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Pich Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). This is joined by broader calls for further understanding and detailed exploration on brand positioning in different contexts and settings (Fayvishenko Citation2018; Mogaji et al. Citation2023). Further, the positioning of political brands ‘is often difficult to capture’ (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Pich Citation2022, 121) and may be due to the complex and nebulous nature of political brand positioning. This may be a key factor for the limited studies on political brand positioning. To address this, perhaps appropriate theoretical lenses are needed to help structure the investigatory process of political brand positioning. Therefore, the related yet distinct constructs of brand identity and brand image could be seen as important dimensions of positioning and serve as unproblematic theoretical lenses to frame the investigatory process of political brand positioning.

Political brand identity and image

To conceptualise how a political brand creates an envisaged position in the minds of stakeholders, the construct of brand identity is a suitable theoretical lens to help structure the desired characterisation (H. He et al. Citation2016; Su and Kunkel Citation2019). More specifically, brand identity represents an internally created strategy designed to communicate what brands ‘stand for’ and constructed to appeal to multiple stakeholders inside and outside the organisation (Nandan Citation2005; Savitri et al. Citation2022; Silveira, Lages, and Simoes Citation2013). Applied to a political setting, brand identity enables political organisations (parties, politicians, campaigns etc), to map out a distinctive narrative from competitors and express their relevance, which in turn provides rationale for stakeholders to identify with their offering and establish a long-term relationship between organisations and their target markets (Foroudi et al. Citation2018; Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2022). Political brand identity can be created and managed around physical and intangible touchpoints (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Plumeyer et al. Citation2017; Propheto et al. Citation2020; Schneider Citation2004). Physical touchpoints can include components such as symbols, logos, signage, messages, policies, and communication platforms-methods-tools devised to raise awareness, communicate differentiation, and resonate with specific target markets. Intangible touchpoints can include components such as brand values, vision, goals, ideology, heritage-culture, feelings, attitudes, and associations often brought to life by the physical touchpoints (Pich et al. Citation2020).

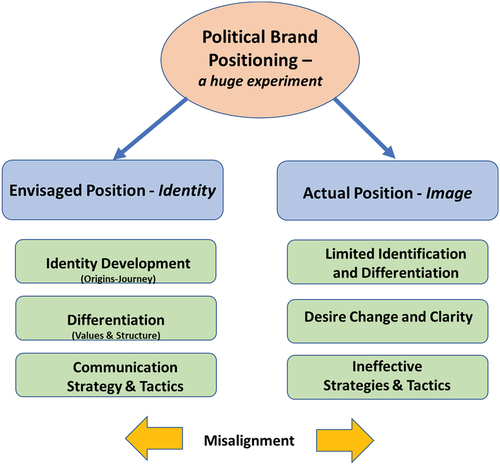

In contrast, brand image is a suitable theoretical lens to structure the realised perceptions, attitudes, and feelings consumers (external stakeholders) associate with the brand (Pich et al. Citation2020; Propheto et al. Citation2020). Brand image can also be interpreted as a set of ‘beliefs, attitudes, stereotypes, ideas, relevant behaviours or impressions that a person holds regarding an object, person or organisation’ (Panda et al. Citation2019, 237). Developed from the commercial brand image literature, political brand image has been defined as the manifestation of the communicated identity combined with perceptions associations and attitudes in the mind of the citizen or voter (Pich, Armannsdottir, and Spry Citation2018). Further, political brand image is seen as the voters’ understanding of the political brands, their perception of what they stand for and their experiences with brands (Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2022; Sharma and Jain Citation2022). It should also be perceived as authentic and should differentiate the brand from other competitors (Jain, Kitchen, and Ganesh Citation2018). Furthermore, political brand image should encourage involvement from stakeholders, live up to their expectations and help with building trust. Political brand image should reveal distinct factors of differentiation which can represent unique selling points for brands (Armannsdottir, Pich, and Spry Citation2019). However, misalignment between projected political brand identity and understood image can damage the clarity of the message or positioning, whilst strong alignment will help with voters’ engagement and trust (Pich Citation2022). A visualisation of key constructs related to political brand positioning can be seen in .

Figure 1. Key dimensions of envisaged and realised political brand positioning inspired by (Marland, Lewis, and Flanagan Citation2017; Pich Citation2022; Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2022; Rutter, Hanretty, and Lettice Citation2015; Sharma and Jain Citation2022; Simons Citation2016).

As Pich and Armannsdottir (Citation2022, 8) argue ‘political brands need to ensure their identities are believable, grounded on style and substance, live up to expectations, coherent across all touchpoints and be prepared to amend their offering in relation to an everchanging dynamic political environment’. Further, alignment between internal political brand identity and external political brand image is critical for organisations if brand is to be considered ‘authentic’ (Pich et al. Citation2020; Sharma and Jain Citation2022). Strategists and researchers should routinely reflect on the current envisaged identity of political brands and audit the realised image of political brands (Pich Citation2022). This will provide a holistic understanding of the political brand, which in turn will allow internal stakeholders to develop strategies to maintain positive, strong, aligned identities or design tactics to correct any misalignment, ambiguity and weaknesses associated with the desired position (Jain, Kitchen, and Ganesh Citation2018). In addition, there are limited studies on political brands that focus on an envisaged (internal) and realised (external) perspective and further research is called for to strengthen understanding of political brands in different settings and contexts (Marland, Lewis, and Flanagan Citation2017; Pich et al. Citation2020; Rutter, Hanretty, and Lettice Citation2015; Simons Citation2016).

Context – the British crown dependency of Jersey

To contextualise this study, the research focused on the Channel Island of Jersey, a British Crown Dependency. Jersey has a population of just under 100,000 across 9 constituencies. The island’s General Election was contested on the 22nd of June 2022 (Pich and Reardon Citation2023). Four political parties contested Jersey’s 2022 General Election including – Jersey Alliance (formed 2021), Reform Jersey (formed 2014), Jersey Liberal Conservatives (formed 2021) and the Progress Party of Jersey (formed 2021). Therefore, three of the four brands were newly created ahead of the 2022 General Election, and Jersey’s 49 seat Parliament was traditionally dominated by independent politicians (Pich and Reardon Citation2023). Prior the 2022 General Election, Jersey Alliance had 10 Members of Parliament. Reform Jersey had 5 Members of Parliament, and the Progress Party of Jersey had 2 Members of Parliament. The Jersey Liberal Conservatives had no elected members in Jersey’s Parliament. The remaining members of the 49-seat Parliament were not part of any political party and sat as independent politicians (Pich and Reardon Citation2023).

provides an overview of the outcome of the 2022 General Election in terms of seats won by independents/parties. 14 candidates (28%) were elected from political parties. Therefore, independent politicians remained dominant in the States Assembly (Pich and Reardon Citation2023). 92 candidates contested 49 seats in Jersey’s Parliament (States Assembly) across 9 constituencies. Voter turnout was 41.6% (out of 60,678 registered voters) compared with 42.3% in Jersey’s 2018 General Election. All four political party brands made gains at the 2022 General Election, however Reform Jersey had greater success compared to the three other political party brands as they managed to double the number of seats.

Table 1. Outcome of the 2022 general election in Jersey – (www.vote.je.).

Subsequently, Jersey served as a suitable context to investigate the envisaged and realised positioning of four political party brands, which up until this point remained an under-explored area of study (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Smith Citation2005). Therefore, this study aimed to:

Explore the brand positioning of political party brands in the context of the British Crown Dependency of Jersey from an internal of party candidate-politician perspective.

Understand the brand positioning of political party brands in the context of the British Crown Dependency of Jersey from an external young voter perspective.

Compare the envisaged and actual brand positioning of the four political party brands and develop a systematic framework to manage the positioning of political brands.

Methodology

As this study aimed to explore the brand positioning of four political party brands from a multi-stakeholder perspective, a qualitative interpretivist approach was considered an appropriate research strategy. Qualitative research is ideal for exploratory studies as the approach attempts to delve beneath the surface and capture rich insights into perceptions, attitudes, feelings, and behaviour (Bell, Bryman, and Harley Citation2019; Warren and Karner Citation2010). In terms of sampling, this study adopted a purposive sampling framework. A purposive sampling framework is a sample based on the researcher’s own judgement, with a focus on ‘some appropriate characteristic required of the sampling members’ (Zikmund Citation2003, 382) selected as they are considered key individuals to help address the research objectives. Purposive sampling is an appropriate sampling strategy as the study aimed to investigate the brand positioning of political party brands from an internal-external standpoint. Stage one of the study focused on internal stakeholders - categorised as party candidates-party members. Stage two of the study focused on external stakeholders - categorised as young voters aged 18–24 years.

As part of stage one, this study adopted semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews have been described as ‘non-standardised’ conversation with a purpose and are facilitated by the researcher and supported by an interview guide structured around broad themes developed from the existing academic literature (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill Citation2016). Eleven semi-structured interviews were carried out in November 2021-February 2022 with members of the four political party brands. Interviews were undertaken on video call (MS Teams) or telephone. provides an overview of the sample for stage one.

Table 2. Sample profile for internal stakeholders – stage one.

In terms of stage two, this study adopted focus group discussions as the principal method for exploring the political brands from an external young voter perspective. Further, focus group discussions are designed to encourage ‘broad discussion among multiple participants to capture both deeper insight and differing ideas on a particular subject’ (Halliday et al. Citation2021, 2145). Focus groups allow for greater flexibility and a natural-like conversation with a purpose compared to other methods (Bell, Bryman, and Harley Citation2019). Five focus group discussions with young voters 18–24 years (30 participants in total) were carried out face-to-face on 18 May − 21 May 2022. An outline of our sample profile can be seen in . Participants from stages one and two were given a unique code to ensure their identification and participation remained anonymous.

Table 3. Sample profile for external stakeholders/voters – stage two.

Thematic analysis served as this study’s analytical strategy. More specially, an inductive thematic approach was adopted to uncover the themes based on the raw findings and not influenced by existing frameworks or templates (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill Citation2016). The goal of thematic analysis is to ‘construct a plausible and persuasive explanation of what is transpiring from the emergent themes, recognising explanations are partial by nature, and there are multiple ways that experiences and/or phenomena can be explained’ (Butler-Kisber Citation2010, 31). To structure the thematic analysis, this study adopted Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six staged framework of thematic analysis. outlines the six-staged process followed as part of our analysis. The six-step approach to thematic analysis developed by Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) not only served as a pragmatic analytical strategy but also provided rigor and trustworthiness to the interpretation process. An outline of each step of our analytical strategy can be seen in .

Table 4. Stages of thematic analysis developed from Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006).

Findings

This study investigated the brand positioning of four political ‘party’ brands from an insider (politicians) and outsider (voter) perspective in the context of the British Crown Dependency of Jersey. The findings are presented in two stages. A visualisation to illustrate the identified themes are set out below. Stage one presents the internally created envisaged position (identity) of the four political brands and focuses on three identified themes including: identity development, differentiation, and communication strategies-tactics. Stage two presents the realised position (image) revealed by young voters structured via three identified themes including: limited identification-differentiation, desire for change and clarity, and ineffective communication strategies-tactics.

Stage one – envisaged political brand position

Identity development

Up until 2012, Jersey’s electoral system was dominated by independent candidates-politicians (IP9). The existing electoral system was often criticised as ‘inefficient’ (IP2), ‘slow’, ‘difficult to get things done as an individual’ (P2), ‘personality-based’ (IP6), and ‘inconsistent’ (IP6). Further, Jersey was ‘like Guernsey, (independent) candidates can’t be focused and can’t make promises’, and policy is developed after candidates are elected and ‘people don’t know what they voted for’ (IP4). Further, it was argued that ‘there’s a suspicion of the establishment on the island’ and ‘people are disconnected from the political system, and something has to change’ (IP11).

The ‘quality of government’ was also raised as justification for the introduction of political party brands to Jersey in addition to the perception that Jersey was governed by ‘an elite … nothing is working’ and ‘poor leadership and ill-considered reforms have brought Jersey politics to where it is’ (IP10). Nevertheless, constitutional reforms of 2022 opened ‘the space for the creation of political parties’ and the realisation that ‘as an individual I’ve realised that if you’re a minister it’s very difficult to get anything done’ (IP9). The introduction of political party brands was considered an efficient, professional, transparent, collective force, and an accountable form of contesting elections and governing (IP5). Further, ‘being in a party, one can still be independent, free thinking, own thoughts … independently minded … parties provide clarity and mandates and transparency … they help (voters) with decision making’ (IP5). However, some participants had originally been critical of the introduction of political ‘party’ brands to Jersey. For instance, ‘originally opposed to political parties, but many of us how now changed our minds and recognise that this makes sense’ (IP9). Similarly, it was argued ‘it’s only in latter years that I’ve changed my mind when it comes to political parties. It really comes down to a few practicalities that centre around and ability to meaningfully get things done’ (IP8).

In addition, the ‘political landscape on the right is crowded … parties are inevitable. It will take a few election cycles’ for political ‘party’ brands to become the norm in Jersey (IP7). Therefore, Jersey’s 2022 General Election was the first-time voters had the option of voting for candidates associated with four political party brands alongside independent candidates. The oldest of the four political party brands (Reform Jersey) was founded in 2012 whereas the three other political party brands were founded in founded 2021–2022 (The Progress Party, Jersey Alliance, and Jersey Liberal Conservatives). below provides an overview of the origins of each political party brand and the last three General Elections.

Differentiation - positioned by values

It was revealed that it was ‘difficult to define your label’ yet in all four cases, the political ‘party’ brands carried out formal and informal exercises to develop ‘what we believe in and what is important to us’ (IP1). Further, the identities of the four political ‘party’ brands were positioned by values. For instance, Reform Jersey was founded in 2012 as a ‘campaign group for electoral reform’ (IP3) in Jersey before registering as an official party to contest the 2014 General Election. Reform positioned itself as a ‘left of centre’ organisation, campaigned for social justice, environmental issues (IP11), and the support of low paid workers. In the 2022 GE, Reform campaigned on specific issues such as ‘education, affordable housing, the living wage, transparency in government, and support for young islanders’ (IP5). Further, Reform was often credited as ‘the trendsetters’ in establishing party politics in Jersey. Indeed, Reform had spent many years prior 2022 arguing for party politics (IP3; IP11) opposed to independents and has now ‘won the battle over being accepted as a party and this opened the gates’ to the formation of other political party brands (P5). Reform was seen as ‘incredibly successful and have shown how it can be done. They are incredibly high profile and well-organised’ (IP11). Finally, it was argued that Reform Jersey had successfully positioned itself as a brand, which represented championed sustainable policies and stewards of environmental issues for instance, ‘there is space for a Green Party and there’s some surprise that one hasn’t already emerged. However, it may be the case that this territory is occupied by Reform Jersey’ (IP11).

The Progress Party was founded in January 2021 as a ‘centrist’ (IP9) political brand however ‘right of Reform Jersey’ (IP2). Similarly, ‘I’d say we are centrist rather than centre right. Yes, it is a crowded field. I would say that the Alliance and the JLC are further to the right than they claim to be. The leaders of those parties have quite big egos and that’s been a hindrance to proper co-operation between the centre right parties’ (IP8). Further, Progress argued it had developed distinct values at the heart of its identity including supporters of ‘transparency, accountability and delivery’ (IP2) and represented a ‘pragmatic approach’ to governing. Progress also claimed that its candidates had a ‘proven track record’ of ‘moderate, sensible’ policies in action and as they had already served in Jersey’s Parliament (States Assembly) (IP9). Progress also put forward specific pledges to ‘review publicly owned housing, introduce a points-based immigration system, to be clear and open with voters’ (IP2). Further, Progress aimed to represent ‘big tent politics’, generate wide appeal and be seen as a ‘big central party to take on the incumbent Alliance Party’. Nevertheless, Progress was ‘open to discussions with anyone and everyone; there’s always room for compromise and pragmatism. Traditionally that is how things have been done in Jersey politics by building consensus’ (IP9).

The Alliance Party was founded in July 2021 and was created by three Ministers in Jersey’s Government (2018–2022) and elected as independent candidates in Jersey’s 2018 General Election. Further, Alliance disliked the label ‘political party’ and attempted to position itself as a ‘political movement’ and a ‘continuity group’, which would continue with the current Government’s plan if re-elected in June 2022. Alliance argued their brand could be seen as a ‘centre-right’ offering (IP1), championing liberal conservatism with an emphasis on ‘opportunities, investment, and an open economy’ with a specific emphasis on ‘improving the quality of government … championing social mobility’ (IP10). However, other internal stakeholders argued they represented a ‘centralist’ position and put forward a ‘sensible, moderate, pragmatic, using what works’ agenda (IP10). Further, ‘I prefer centrist. But we’re labelled the centre right which works in Jersey as Jersey people are very conservative’ (IP10). Like Progress, Alliance were also ‘open to discussions with independents, the JLC and Progress. Can find common ground. That’s how Jersey politics works and there’s no reason to believe that parties will make it that different’ (IP10). However, pressed on whether Alliance would collaborate with Reform, the participant suggested that this would not be the case as ‘Reform is left. It’s funded by Unite who clearly do the work for them. It’s a populist party. The solution to everything is give people money. They are well organised and good campaigners. Their leader was a minister. Simplistic solutions to everything. Tax the rich. If you tax the rich they will go somewhere else’ (IP10).

Finally, Jersey Liberal Conservatives (JLC) were founded in January 2022–5 months before the 2022 June General Election. The JLC claimed that they were ‘not keen on ideology … some say right-wing, and some say left-wing’ (IP4) yet argued they were ‘fiscally conservative and socially liberal’, similar to the David Cameron’s UK Conservative Party (2005–2016). Further, the JLCs was founded as a ‘movement’ with three overarching values including ‘transparency, truthfulness and tolerance’ and over the course of six months, developed the political brand into a registered party (December 2021) and officially launched in January 2022. An overview of each of the four political party brands in terms of their desired positioning, structure, strategies-tactics, and reflections of competitors can be seen in .

Table 5. An overview of the four political party brands in Jersey.

It was also revealed that creating an identity and establishing differentiation was challenging in terms of raising awareness, support, and knowledge. Despite participants arguing clear justification for the introduction of political ‘party’ brands, most participants recognised this would be challenging. Firstly, ‘most Jersey voters simply don’t know what’s coming down the line. They have no awareness of how much of a change the constitutional reforms will be and what they mean. The first they know about them will be when they go to vote … Jersey is a right-leaning society, but time will tell how far this assumption is tested’ (IP9). Further, ‘public attitudes will be the biggest barrier to effectively creating and sustaining political parties’ (IP11), however, ‘parties could play a role where they are simply a pragmatic vehicle for a collection of like-minded people to win election’ (IP11). For instance, there were ‘significant logistical challenges’ and limited support in place for developing political ‘party’ brands in Jersey. For instance, ‘despite constitutional reforms the system is set up to mitigate against establishing a party’ (IP9). It was acknowledged that establishing a political ‘party’ brand was a ‘big political experiment’ (IP4) and party members had no experience, we had to make it up as we went along’ (IP6), and some adopted ‘an artisan approach’ (IP1) to designing and developing an identity.

In contrast, some political brands used existing parties in other jurisdictions as a case or blueprint of how to develop their political party. For example, Progress used the ‘New Zealand Labour Party was our model. We wanted to find a party in a similar society that was pragmatic and centre ground’ (IP9). Similarly, ‘New Zealand Labour Party was the model – policies can be put side by side with those of Progress. Policies in key areas of the economy, housing, health, and education are exactly the same. A source of inspiration’ (IP8). This was also the case for the JLC. The JLC sought inspiration from ‘David Cameron’s UK Conservative manifesto’ to develop its identity and position (IP4). Finally, the JLC also sought guidance and advice from ‘contacts in the UK and former colleagues and current friends who held senior media and advisory roles in both the Conservative and Labour parties’ (IP10). ‘That advice was critical, but the system does not make it easy to establish parties and there’s a local pushback against having them, even though the political system by default kind of encourages them’ (IP10). Reform Jersey were in a strong and unique position. Reform Jersey had managed to position themselves as the ‘party of opposition’ (IP6) as they had developed their identity over time and had the fortune to try and test policies, messages and ensure they were projecting a united and professional position, which was acknowledged by their competitors (IP4; IP5; IP8). Therefore, the four political brands adopted a pragmatic approach in creating their identities.

Communication strategies/tactics

All four political ‘party’ brands adopted traditional communication strategies and tactics to raise awareness, encourage engagement, and communicate ‘what they stood for’ (IP1). For example, all four parties used mainly offline tactics including leaflets, posters in streets, businesses, and gardens, short 500-word manifestoes, election material published in local newspapers, question-and-answer events (hustings) and door-to-door canvassing (door-knocking). Reform Jersey also used non-traditional tactics including hosting a ‘Rock the Vote’ music event designed to appeal and engage younger voters (IP5). Whereas pop-up street stalls were rolled out in prominent positions in the High Street of Jersey’s capital to discuss key political issues with voters, raise awareness, and carry out informal market research (IP5; IP6). Nevertheless, it was acknowledged that canvassing was a key tactic (IP3; IP4; IP6; IP8; IP10) and ‘comfortable shoes are an electioneering aid’ (IP4) as it was crucial for candidates to canvas as many houses across consistencies as possible to engage with voters. Further, door-knocking was considered ‘crucial’ to connect with voters and explain what the political ‘party’ brands represented. For instance, the word ‘party’ in Jersey was considered ‘controversial’ (IP1) and candidates associated with parties in Jersey would need time to ‘explain’ (IP4) their vision, and ‘persuade people’ (IP6) why they should support a party over independent candidates.

All four political ‘party’ brands also had an online presence to support the offline tactics. Further, Reform Jersey had a stronger online presence compared to its rivals and this was due to the fact the party was well-established and had contested previous elections (IP3). Online tactics included party websites, social media platforms managed by each party, and election content created by Jersey’s Electoral Authority (Vote.je). There was also limited coverage given to the four political ‘party’ brands (and limited coverage of independent candidates) provided by the island’s broadcast media (online, television, and offline) including the BBC and ITV. Coverage was limited due to the challenges of providing unbiased and impartial time/exposure/reporting to all 92 candidates (party-candidates and independent candidates).

It was reported that the strategies and tactics adopted by the four parties were constrained by the limited funding for parties (IP1; IP2). For example, the lack of funding and resources was frustrating. The problem was to do with finance and getting a bank account set up. It took us three or four months to get a bank account established. None of the island’s banks would set up an account for ourselves or the other parties. They said they wanted to remain neutral and that they were apolitical. This had a massive impact on us … We couldn’t do any fundraising because we had nowhere to deposit it, we couldn’t accept donations as a newly formed political party which was very difficult, and it was a very anti-democratic decision for the banks to make (IP8). Similarly, ‘For nine months it was nigh on impossible to find. A clearing bank anywhere in Jersey that would go near us with a bargepole’ (IP9). Further, it was also argued there was no ‘infrastructure’, (IP1) and ‘machine’ (IP6) to support the rollout and management of parties (IP1), and the current electoral system was designed to support independent candidates rather than support political parties. The current election laws for example were described as ‘unclear and allow dirty tactics’ to prevail (IP2), therefore, Jersey should ‘be serious about the development of political parties’ and ensure resources are in place to support a party system (IP5).

Stage two – realised political brand position

Limited identification and differentiation

It was revealed that most young voters were interested in political issues. For instance, young voters argued that ‘housing’ (P5FG5), ‘education’ (P2FG3), ‘improving transport links’(P1FG4), ‘employment prospects’ (P2FG1), ‘improving healthcare for all islanders’ (P5FG3), the climate emergency’ (P5FG2), and ‘the cost-of-living crisis’ (P6FG1) were key topics of interest to young people in Jersey. Further, it was revealed that ‘you don’t have to be clued up or an expert on politics to have an opinion or be passionate about important concerns that face all islanders including young people’ (P3FG3).

In addition, there was limited awareness of the four political party brands across all focus group discussions and limited understanding of the positioning, identity, or policies of the political party brands. For example, most participants argued ‘to be honest, I didn’t know we had parties in Jersey and don’t have a clue what they stand for’ (P3FG3), and ‘we have parties in Jersey? Since when? (P6FG5) Similarly, ‘unsure what they stand for’ (P6FG2), ‘no idea’, (P5FG1) ‘they’re all the same’ (P2FG1), ‘no difference to me … a group of politicians all saying the same thing’ (P7FG5), and ‘they need to tell us what they stand for. Do they have policies? Are they the same as the parties in the UK? (P1FG5). However, despite there was some awareness of the names of the four political party brands across all five focus groups, participants were only able to provide some detail on one political party brand – Reform Jersey. ‘I only know about Sam Mezec’s party, Reform. They’re big on improving housing’ (P4FG5). ‘Reform are for the working-class’ (P3FG3), ‘education’ (P2FG4), and ‘campaign on green (sustainability) issues’ (P2FG1). ‘Sam came to my old school to talk about politics. He’s young. He’s in a band’ (P4FG1). Therefore, apart from Reform, there was limited identification and differentiation between the four political party brands apart from Reform Jersey.

Desire change and clarity

Young voters argued that they felt ‘frustrated’ (P4FG1) about the limited understanding of the positioning of the four political-party brands. It was argued that ‘no one listens to us or actually asks us what is important to us’ (P2FG5), ‘they don’t care about young people … all they’re bothered about is big business and finance’ (P4FG2), ‘if they took the time to ask us then it may push more people into getting involved or engaged in politics’ (P6FG5). ‘If a politician actually asked me what was important to me, then that would be a start’ (P1FG3). ‘I’m interested in politics, but they seem to forget about young people, it’s as if I don’t count’ (P5FG4). Further, most voters believed parties had failed to ‘reach out’ (P3FG5), ‘make a connection with young voters’ (P1FG1) even though young voters were ‘engaged and interested’ (P3FG3) in the upcoming General Election.

In addition, it was found that our young voters welcomed the introduction of political party brands to the dynamic political environment of Jersey. Young voters believed the introduction of political parties would bring ‘much needed clarity’ (P3FG3), ‘clearer differentiation’ (P2FG1) and ‘simplify choice in elections as we will finally know what politicians stand for’ (P5FG2). Further, the introduction of political party brands would also ‘shake things up a bit’ (P2FG4), and ‘inject a bit of fun into elections as politics in Jersey is pretty boring. Politicians (independents) in the past have all said the same thing and they’re not clear about what they will do if they’re elected’ (P2FG5). Political parties also ‘send out detailed manifestoes and clarify what they will do. Political parties do that in the UK like the Conservatives and Labour, and this makes it clearer as you know what you’re voting for’ (P4FG3).

Ineffective strategies and tactics

Young voters also discussed the use of strategies and communication tactics used by political brands in Jersey and this was not limited to the political parties. For example, it was found that candidates used a range of traditional campaign strategies and communication tactics including ‘posters-banners’ featuring the picture of candidates on lampposts, shops, restaurants, cafes across the island. In addition, posters-banners were also displayed in ‘gardens and hedgerows or prominent junctions across the island. Tactics also included ‘leaflets’ (P2FG2), ‘manifestoes’ (P2FG5), election information in ‘newspapers’ (P2FG1) and ‘online’ (P4FG2). However, very few participants could recall examples of online content created by candidates or social media platforms used by candidates. Nevertheless, two self-proclaimed ‘engaged’ voters recalled the leader of Reform Jersey [Sam Mezec] as ‘active on Twitter’ and ‘often posts content not always about politics. Sam did that “Rock the Vote” gig a few years ago’ (P2FG3), which prompted another participant in the same group to argue ‘yeah I remember my dad saying something about that earlier this week. He said Sam was a good musician. Gigs could be a good way to get more young people interested in politics. Politicians should be creative and make politics fun. You’ve got to admit, it can be dull’ (P3FG3).

A small number of participants also stated that ‘hustings’ (P4FG1; P5FG4; P4FG5) – (town hall style question and answer sessions with candidates) was another common campaign tactic. However, most participants revealed that they had never attended a hustings event as ‘they wouldn’t know what to do or ask’ (P5FG4). Nevertheless, a common yet debated tactic was ‘door-knocking’ (door-to-door canvassing). Most participants were aware of ‘door-knocking’ (P3FG1; P5FG2; P3FG4), however, many believed door-knocking was ‘awkward’ (P5FG5) and ‘embarrassing’ (P3FG3) as they didn’t know how to respond to candidates on the doorstep. Further, several participants revealed that they often ‘ignored candidates’ (P1FG2) and ‘pretended to be out’ (P6FG1) if candidates canvassed their home addresses as door-knocking was seen as ‘annoying’ (P6FG1). When probed for tactics that would appeal to young voters, participants argued that candidates should use more on ‘online’ tactics (P2FG2) as ‘that’s what young people are interested in and use’ (P5FG2). Further, participants argued that candidates need to create ‘a buzz’ (P3FG3) on the run up to an election, make politics ‘interesting’, (P5FG5) ‘relevant’ (P1FG1) and to ‘be creative’ (P1FG3) with the campaign strategies-tactics. Participants argued that young people are ‘interested’ (P5FG3) in politic issues but politicians fail to communicate the ‘relevance’ and ‘impact’ (P4FG1) of politics to the everyday life of voters. Therefore, participants argued that political party brands should campaign with appealing and appropriate tactics designed to ‘engage young voters’ (P2FG2) rather than ‘outdated’ (P5FG2) and ‘alienating’ (P2FG1) electioneering methods.

Discussion and conclusion

This study explored the brand positioning of four political ‘party’ brands in the context of the British Crown Dependency of Jersey from multi-stakeholder perspective. Further, this study aimed to compare the envisaged and actual brand positioning of the four political party brands and develop a systematic framework which could be used to manage the positioning of political brands. Existing research in this area has tended to focus on established political party brands rather than new-emerging political brands or political brands in dynamic political systems (Marland, Lewis, and Flanagan Citation2017; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Pich Citation2022). Therefore, Jersey’s four political parties served as appropriate brands to frame this study, as three of the four brands were newly created ahead of the 2022 General Election, and Jersey’s 49 seat Parliament was traditionally dominated by independent politicians (Pich and Reardon Citation2023).

This study adds to the limited research the envisaged and realised positioning of political brands (Pich Citation2022; Smith Citation2005) by providing deep insight into the internal identity and external image of four political brands. Further, this study addresses explicit calls for further research on brand positioning in different context and settings (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Fayvishenko Citation2018; Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Mogaji et al. Citation2023; Smith Citation2005). For example, this study revealed each political party brand represented a unique case in terms of creation, development, and management. Further, the findings highlight that each political party brand started from humble beginnings often created from scratch and developed and managed by a small group of individuals. In addition, each political party brand faced a series of challenges for development and existence in an electoral system structured and dominated by independent politics. For instance, internal stakeholders created clear positioning for political party brands grounded on values and visual identity cues rather than grounded on distinct policies. Reform was the first political party brand out of the four to carve out a position in the market and designed a distinct position of centre-left politics based on a gap in the market (dominance of independent politics – centre and centre-right leaning) and set the agenda and landscape for the other three political party brands. Therefore, the four political party brands developed their identities structured around intangible values, envisaged policies, and issues that attempted to set them apart from their political rivals.

The four political party brands attempted to communicate ‘what they stood for’ and how their offering differed from their direct competitors. Alliance was often seen as the ‘party of government’ and ‘incumbents’ whereas Reform, Progress, and JLC were seen as the outsider or unofficial ‘opposition’. JLC and Progress also merged/co-brands in the penultimate weeks of the general election, which changed the political offering from four to three political brands. The three new political brands also acknowledged respect for their political rival (Reform) in terms of professionalism, structure, consistency, and the fact Reform had contested several elections in comparison to the new political brands. Therefore, Reform was at an advantage compared to the three new political brands in terms of experience, development, maturity, and use of additional communication strategies/tactics. Nevertheless, all four political party brands utilised a range of similar traditional communication tactics mainly offline to communicate with the electorate. Further, all four also used some online tactics. However, Reform utilised several creative tactics to engage voters and communicate their identity.

To reiterate, political brand positioning signifies how a political brand ‘wants to be seen’ and the ‘act of designing the company’s offering and image to occupy a distinctive place in the mind of the target market’ (Kotler and Keller, 2003: 867). All four political brands were successful in part, in terms of developing envisaged positions and identities grounded upon values (Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Newman and Newman Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). However, political strategists also aim to project a clear, relatable, and comprehensible position in the minds of voters (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Pich Citation2022; Smith and French Citation2009) and this was not necessarily the case in this research. For example, this study uncovered the brand positioning of the four political party brands and young voters highlighted that there was limited differentiation and identification with the political party brands. However, there was awareness of the Reform political brand compared to the three new political party brands, mainly due to its leader and creative tactics. Nevertheless, young voters argued that the introduction of political party brands would bring greater clarity and understanding to the positioning and offering of the political brands and this underpinned the ‘desire for change’ and desire to make politics relatable, relevant, and impactful. Most young voters also argued that the four political brands used effective communication strategies and tactics and called for creative methods to capture their attention to communicate what they stand for and communicate the relevance/impact of politics to young voters. Therefore, this study demonstrates that political brand positioning is complex, yet it remains a ‘two-way communication process’ involving the producer-creator (insider the organisation), and consumer (outside the organisation) (O’Shaughnessy and Baines, Citation2009: 239).

It was also reported that investigating the positioning of political brands ‘is often difficult to capture’ (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Pich Citation2022, 121) and may be due to the complex and nebulous nature of political brand positioning. Therefore, this study demonstrates that the related yet distinct concepts of internal brand identity (H. He et al. Citation2016; Su and Kunkel Citation2019) and external brand image (Pich et al. Citation2020; Propheto et al. Citation2020) are appropriate theoretical lenses to help structure the investigatory process of positioning. For instance, brand identity enables political organisations (parties, politicians, campaigns etc), to map out a distinctive narrative from competitors and express their relevance, which in turn provides rationale for stakeholders to identify with their offering and establish a long-term relationship between organisations and their target markets (Foroudi et al. Citation2018; Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2022). Political brand identity can be created and managed around physical and intangible touchpoints (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Plumeyer et al. Citation2017; Propheto et al. Citation2020; Schneider Citation2004). Whereas brand image is the manifestation of the communicated identity combined with perceptions associations and attitudes in the mind of the citizen or voter (Pich, Armannsdottir, and Spry Citation2018). Further, political brand image is seen as the voters’ understanding of the political brands, their perception of what they stand for and their experiences with brands (Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2022; Sharma and Jain Citation2022). Therefore, alignment between internal political brand identity and external political brand image is critical for organisations if a brand is to be considered ‘authentic’ (Pich et al. Citation2020; Sharma and Jain Citation2022).

Strategists and researchers should routinely reflect on the current envisaged identity of political brands and audit the realised image of political brands (Pich Citation2022). This will provide a holistic understanding of the political brand, which in turn will allow internal stakeholders to develop strategies to maintain positive, strong, aligned identities or design tactics to correct any misalignment, ambiguity and weaknesses associated with the desired position (Jain, Kitchen, and Ganesh Citation2018). Subsequently, this study revealed that envisaged, and realised positioning can differ (Pich Citation2022), and this could be why three of the four political party brands had limited success at the 2022 General Election. Aligned brands are perceived as credible, trustworthy, authentic, and united, which could explain Reform Jersey’s success at the ballot box (Smith and French Citation2009).

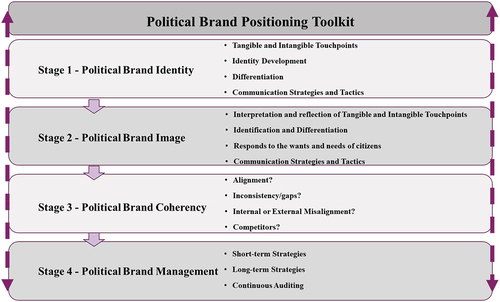

The findings have implications for academics and practitioners beyond the world of politics. More specifically, this study puts forward ‘the Political Brand Positioning Toolkit’ – . The proposed toolkit developed from existing theory and from the empirical findings represents a systematic framework of how to position new or existing brands and strategically manage a brand’s envisaged and realised positioning.

Stage one focuses on the envisaged brand identity, which refers to the tangible (communication strategies, tactics, and messages) and intangible touchpoints (including values, issues, and imagery). The envisaged identity which aims to develop a distinct position in the mind of internal and external stakeholders, which in turn should provide differentiation with competitors and encourage identification between stakeholders and the brand. Stage two focuses on capturing the realised image/position in relation the brand’s tangible and intangible touchpoints. In addition, stage two will provide insight into the interpretation of the desired position and reveal awareness, familiarity, impact, relevance, authenticity, and identification associated with the brand. Stage three will allow strategists and researchers the opportunity to compare the brand’s envisaged and realised position, ascertain alignment or inconsistencies, and highlight points of differentiation or parity with competitors. Finally, stage four focuses on utilising the captured insight from stages one to three to develop short-term and long-term strategies to respond and address any inconsistencies, amend desired positioning, and manage communicated identity. Auditing should be carried out on a routine basis as part of a proactively managing and safeguarding a brand’s position.

Subsequently, this study provided deep insight into the envisaged and realised positioning of four political brands. Up until now, there has been a paucity of research dedicated to investigating an envisaged and realised perspective (P. R. Baines, Lewis, and Ingham Citation1999; Gurau and Ayadi Citation2011; Pich Citation2022; Smith Citation2005). This study accepts that the positioning of political brands ‘is often difficult to capture’ (P. Baines et al. Citation2014; Pich Citation2022, 121) however brand identity and brand image are two inter-related yet distinct theoretical lenses, which help structure the investigatory process. Further, this study presents the developed multi-stage framework entitled ‘the political brand positioning toolkit (), to manage the positioning of political brands. This systematic framework represents a pragmatic method that can be adopted by practitioners and researchers to audit the envisaged and realised position of brands. Finally, this study reaffirms that brands are ‘everywhere and everything is a brand’ (Richelieu Citation2018, 354), therefore it is crucial for practitioners and researchers to routinely examine the envisaged and realised position of brands as this will help manage brands and improve the customer/voter journey.

Limitations and future research

All studies have limitations (Rashid, Spry, and Pich Citation2024). Firstly, Jersey represented a unique setting and due to the exploratory nature of this study, the findings are not generalisable beyond the jurisdiction of Jersey. The nature of qualitative research does not provide representative samples of the target population, whereas quantitative research would address this limitation. Therefore, this study documented the world view of internal and external stakeholders regarding the political brand positioning of four party brands, with an increased emphasis on intimate knowledge and depth rather than breadth (Bell, Bryman, and Harley Citation2019; Warren and Karner Citation2010). Future studies could go some way in addressing this and adopt a multi-method approach to investigate brand positioning within and beyond politics. More specifically, quantitative methods could be adopted to measure the coherency/misaligned of the envisaged and realised position of brands and this would complement the qualitative insight. This in turn would support the development of short-term and long-term strategies to manage the positioning of brands. Future research could also consider interviewing additional internal groups/members including supporters, party members, volunteers and individuals employed by the political parties. This would provide additional insight into the envisaged positioning and coherency of the internal perspective. Similarly, future research should consider other groups of voters potentially segmented via demographic, psychographic, geographic and/or socio-cultural variables. This would then lead to more comparative studies and provide even greater insight into the realised position of political brands.

Second, Graziano and Raulin (Citation2004) argued that the poor replicability of qualitative inquiry can be considered a limitation that needs to be acknowledged. Nevertheless, this study accepts that poor replicability thus flexibility can be seen as a strength of qualitative inquiry. This research accepts that different researcher’s exploring the same phenomenon through qualitative inquiry may witness different observations and different inferences (Graziano and Raulin Citation2004). Moreover, Graziano and Raulin (Citation2004, 141) suggested that ‘replication is possible only if researchers clearly state the details of their procedures’. Therefore, procedural replication of this study is somewhat possible. For instance, this study followed and applied a six-staged framework to analyse the findings from the interviews and focus group discussions. Second, this study developed a systematic four staged framework () which operationalises political brand positioning. Future research should assess the usability and transfer potential of the multi-stage framework to contexts within and beyond politics as an investigatory tool and make amendments/improvements if necessary. In addition, researchers should consider carrying out longitudinal and comparative research on the positioning of political brands in national and international settings, which continues to be an under-researched and under-developed area of study. In fact, studies on the envisaged and realised positioning of brands beyond politics also remains limited, therefore researchers should consider this as another stream of further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

C. Pich

Dr C. Pich is an Associate Professor in marketing and branding at Nottingham University Business School, The University of Nottingham, United Kingdom. He is an active researcher currently focusing on the application of branding concepts and frameworks to the political environment ranging from brand identity, brand image, brand reputation, co-branding and consumer-based brand equity. Further, Christopher specialises in the use of qualitative projective techniques in interviews and focus group discussions. He has published work in a range of academic journals such as the Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Vocational Behaviour, Journal of Strategic Marketing, Journal of Marketing Management, International Journal of Market Research, Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, and the Journal of Political Marketing. Finally, Christopher is the Managing Editor for Europe for the Journal of Political Marketing (2016-Present), and Associate Editor for the International Journal of Market Research (2023-Present).

J. Reardon

Dr J. Reardon is a researcher and Associate Lecturer at the University of Cumbria. He is an education professional with a long and proven track record of securing good outcomes. John possesses professional expertise in teaching and learning, Initial Teacher Education (ITE), mentoring, coaching, behaviour management and raising attainment. Further, John is a experienced researcher, with a distinct focus on comparative politics, governance, local government, political branding and small states and territories, using mostly but not exclusively qualitative methodologies. Finally, John has published work in international journals such as the Journal of Small States and Territories and presents research at international conferences most recently the 2024 Political Studies Association Annual Conference.

A. Armannsdottir

Dr A. Armannsdottir is a Senior Lecturer at Nottingham Business School, Nottingham Trent University. Her expertise includes political marketing and brand political branding, focusing on political band identity and image. She has published her work in various journals such as Journal of Vocational Behaviour, International Journal of Marketing Research, Qualitative Market Research: an International Journal, Journal of Political Marketing and Politics and Policy.

References

- Aaker, J. L. 1997. “Dimensions of Brand Personality.” Journal of Marketing Research 34 (3): 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379703400304.

- Armannsdottir, G., C. Pich, and L. Spry. 2019. “Exploring the Creation and Development of Political Co-Brand Identity: A Multi-Case Study Approach.” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 22 (5): 716–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-10-2018-0119.

- Baines, P., I. Crawford, N. O’Shaughnessy, R. Worcester, and R. Mortimore. 2014. “Positioning in Political Marketing: How Semiotic Analysis Adds Value to Traditional Survey Approaches.” Journal of Marketing Management 30 (1–2): 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.810166.

- Baines, P. R., B. R. Lewis, and B. Ingham. 1999. “Exploring the Positioning Process in Political Campaigning.” Journal of Communication Management 3 (4): 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb023496.

- Balmer, J. M. T., and M. N. Liao. 2007. “Student Corporate Brand Identification: An Exploratory Case Study.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 12 (4): 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280710832515.

- Bell, E., A. Bryman, and B. Harley. 2019. Business Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Butler-Kisber, L. 2010. Qualitative Inquiry: Thematic, Narrative and Arts-Informed Perspectives. London: Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526435408.

- Collins, N., and P. Butler. 2002. “Considerations on Market Analysis for Political Parties.” In The Idea of Political Marketing, edited by N.J. O’Shaughnessy and S.C.M. Henneberg, 1–17. Westport: Praeger Publishers.

- de Chernatony, L. 2007. From Brand Vision to Brand Evaluation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Fayvishenko, D. 2018. “Formation of Brand Positioning Strategy.” Baltic Journal of Economic Studies 4 (2): 245–248. https://doi.org/10.30525/2256-0742/2018-4-2-245-248.

- Foroudi, P., Z. Jin, S. Gupta, M. M. Foroudi, and P. J. Kitchen. 2018. “Perceptional Components of Brand Equity: Configuring the Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Paths to Brand Loyalty and Brand Purchase Intention.” Journal of Business Research 89 (2018): 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.031.

- Graziano, A. M., and M. L. Raulin. 2004. Research Methods: A Process of Inquiry. Boston USA: Pearson Education Group Inc.

- Gurau, C., and N. Ayadi. 2011. “Political Communication Management.” Journal of Communication Management 15 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/13632541111105222.

- Halliday, M., D. Mill, J. Johnson, and K. Lee. 2021. “Let’s Talk Virtual. Online Focus Group Facilitation for the Modern Researcher.” Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 17 (12): 2145–2150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.02.003.

- He, H., L. C. Harris, W. Wang, and K. Haider. 2016. “Brand Identity and Online Self-Customisation Usefulness Perception.” Journal of Marketing Management 32 (13–14): 1308–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1170720.

- Jain, V., P. J. Kitchen, and B. E. Ganesh. 2018. “Developing a Political Brand Image Framework.” In Back to the Future: Using Marketing Basics to Provide Customer Value. Proceedings of the 2017 Academic of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual conference, edited by N. Krey and P Rossi. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66023-3_147.

- Johnson, R. M. 1971. “Market Segmentation: A Strategic Management Tool.” Journal of Marketing Research 8 (1): 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377100800101.

- Marland, A., J. P. Lewis, and T. Flanagan. 2017. “Governance in the Age of Digital Media and Branding.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions 30 (1): 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12194.

- Mogaji, E., M. Restuccia, Z. Lee, and N. P. Nguyen. 2023. “B2B Brand Positioning in Emerging Markets: Exploring Positioning Signals via Websites and Managerial Tensions in Top-Performing African B2B Service Brands.” Industrial Marketing Management 108:237–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.12.003.

- Nandan, S. 2005. “An Exploration of the Brand Identity-Brand Image Linkage: A Communications Perspective.” Journal of Brand Management 12 (4): 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540222.

- Needham, C. 2005. “Brand Leaders: Clinton, Blair and the Limitations of the Permanent Campaign.” Political Studies 53 (2): 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00532.x.

- Needham, C., and G. Smith. 2015. “Introduction: Political Branding.” Journal of Political Marketing 14 (1–2): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.990828.

- Newman, B. I. 1999. “A Predictive Model of Voting Behaviour. The Repositioning of Bill Clinton.” In Handbook of Political Marketing, edited by B. L. Newman, 259–282. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Newman, B. I., and T. P. Newman. 2022. “Introduction: Political Marketing Analysis, Synthesis and Future Considerations.” In A Research Agenda for Political Marketing, edited by B. I. Newman and T Newman, 1–14. Elgar Research Agendas, Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800377202.00007.

- Norris, P., J. Curtice, D. Sanders, M. Scammell, and H. A. Semetko. 1999. On Message: Communicating the Campaign. London: Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446218587.

- Panda, S., S. C. Pandey, A. Bennett, and X. Tian. 2019. ““University Brand Image As Competitive Advantage: A Two-Country Study.” International Journal of Educational Management 33 (2): 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-12-2017-0374.

- Pich, C. 2022. “Political Branding - a Research Agenda for Political Marketing.” In A Research Agenda for Political Marketing, edited by B. I. Newman and T Newman, 121–142. Elgar Research Agendas, Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800377202.00014.

- Pich, C., and G. Armannsdottir. 2022. “Political Brand Identity and Image: Manifestations, Challenges and Tensions.” In Political Branding in Turbulent Times. Palgrave Studies in Political Marketing and Management, edited by M Moufahim, 9–32. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83229-2_2.

- Pich, C., G. Armannsdottir, D. Dean, L. Spry, and V. Jain. 2020. “Problematizing the Presentation and Reception of Political Brands.” European Journal of Marketing 54 (1): 190–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2018-0187.

- Pich, C., G. Armannsdottir, and L. Spry. 2018. “Investigating Political Brand Reputation with Qualitative Projective Techniques from the Perspective of Young Adults.” International Journal of Market Research 60 (2): 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785317750817.

- Pich, C., and J. Reardon. 2023. “A changing political landscape : The 2022 general election in Jersey.” Small States & Territories 6 (2): 169–184.

- Pich, C., and L. Spry. 2019. “Understanding Brands with Contemporary Issues.” In Contemporary Issues in Branding, edited by P. Foroudi and M. Palazzo. Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429429156-2.

- Plumeyer, A., P. Kottemann, D. Böger, and R. Decker. 2017. “Measuring Brand Image: A Systematic Review, Practical Guidance, and Future Research Directions.” Review of Managerial Science 13 (2): 227–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0251-2.

- Propheto, A., D. Kartini, S. Sucherly, and Y. Oesman. 2020. “Marketing Performance As Implication of Brand Image Mediated by Trust.” Management Science 10 (4): 741–746. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.10.023.

- Rashid, A., L. Spry, and C. Pich. 2024. “A Proposed Brand Architecture Model for UK Fashion Brands.” Journal of Brand Management. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-024-00358-9.

- Richelieu, A. 2018. “A Sport-Oriented Place Branding Strategy for Cities, Regions and Countries.” Sport, Business and Management 8 (4): 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-02-2018-0010.

- Ronzoni, G., E. Torres, and J. Kang. 2018. “Dual Branding: A Case Study of Wyndham.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights 1 (3): 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-03-2018-0016.

- Rutter, R. N., C. Hanretty, and F. Lettice. 2015. “Political Brands: Can Parties Be Distinguished by Their Online Brand Personality.” Journal of Political Marketing 17 (3): 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2015.1022631.

- Saunders, M., P. Lewis, and A. Thornhill. 2016. Research Methods for Business Students. 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson.

- Savitri, C., R. Hurriyati, L. Wibowo, and H. Hendrayati. 2022. “The Role of Social Media Marketing and Brand Image on Smartphone Purchase intention.” International Journal of Data & Network Science 6 (1): 185–192. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.9.009.

- Schneider, H. 2004. “Branding in Politics – Manifestations, Relevance and Identity-Oriented Management.” Journal of Political Marketing 3 (3): 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J199v03n03_03.

- Sharma, P., and V. Jain. 2022. “Influencers and the Building of Political Brands—The Case of India.” Political Branding in Turbulent Times: 69–85.

- Silveira, C. D., C. Lages, and C. Simoes. 2013. “Reconceptualising Brand Identity in a Dynamic Environment.” Journal of Business Research 66 (1): 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.020.

- Simons, G. 2016. “Stability and Change in Putin’s Political Image During the 2000 and 2012 Presidential Elections: Putin 1.0 and Putin 2.0.” Journal of Political Marketing 15 (2–3): 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2016.1151114.

- Smith, G. 2005. “Positioning Political Parties: The 2005 UK General Election.” Journal of Marketing Management 21 (9–10): 1135–1149. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725705775194184.

- Smith, G., and A. French. 2009. “The Political Brand: A Consumer Perspective.” Marketing Theory 9 (2): 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593109103068.

- Su, Y., and T. Kunkel. 2019. “Beyond Brand Fit: The Influence of Brand Contribution on the Relationship Between Service Brand Alliances and Their Parent Brands.” Journal of Service Management 30 (2): 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2018-0052.

- Warren, C. A. B., and T. X. Karner. 2010. Discovering Qualitative Methods: Field Research, Interviews and Analysis. 2nd ed. California: Roxbury Publishing Company.

- Zikmund, W. G. 2003. Business Research Methods. 7th ed. USA: Thomson/ South-Western.