ABSTRACT

Since the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime in 2003, Iraqi Shi’a political actors have been the main forces leading the country, dominating the domestic legislative scene over their Sunni and Kurdish counterparts. This article brings innovative analysis and classification of actors, such as Islamic Da’wa Party, Badr Organization, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), Harakat Huquq, Al-Hikma, Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), Sadrist Movement, or Imtidad, bringing more light on the Iraqi political scene since the parliamentary elections in 2021. The ideological anchorage of the parties is evaluated in two dimensions, religious and sectarian, placing them on the Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist axes, reflecting their approach towards intra-religious issues, vilayet al-faqih, possible normalization of relations with Israel, sectarianism, and nationalism. The methodology of this research is based on Chapel Hill Expert Survey data collection, semi-structured interviews with politicians and political experts from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Iraq, Jordan, and the United Kingdom, content analysis of examined actors’ statements on social and official media and opinion polls, reflecting the voices of the Iraqi society. The main results of this research singled out clusters of more pro-Iranian actors (Badr Organization, AAH, Harakat Huquq), with the highest tendency to use Islamic and sectarian policies, followed by more traditional Iraqi political actors such as Islamic Da’wa Party and ISCI. Al-Hikma, Sadrist Movement and Imtidad then inclined to be more nationalist and secular. Finally, it shows the Iranian influence as a crucial factor in shaping the domestic and foreign policies of thoseactors.

Introduction

After the US-led coalition toppled the dominant Sunni regime led by Saddam Hussein in 2003, the Iraqi Shi’a political actors not only became key decision-making actors but also constituted the first ever Shi’a-led authority in the modern Arab world.Footnote1 Iraqi Shi’as evolved into the main force in the country, drawing strength from the support of the majority Shi’a population and pre-election unity in 2005 and 2010.Footnote2 However, over time gradual fragmentation occurred, especially due to 2014, 2018, and 2021 parliamentary elections, where individual Shi’a groups started to compete not only in the political and ideological dimension but also on the security level.Footnote3 Despite partial divisions, today the main Iraqi Shi’a political actors lead the current Iraqi government, except for the Sadrist Movement.Footnote4 On 12 June 2022, 73 Sadrist representatives resigned their positions in the Iraqi parliament after Muqtada al-Sadr asked them to step down amid a prolonged stalemate over forming a government.Footnote5 These steps led to the failure to form the national majority government (and implementing reforms) that Sadr called for, making the difference in involved actors in the Iraqi political scene pre- and post-2021.Footnote6 In this light, the term ‘Shi’a politics’ needs a reconceptualization in the context of today’s Iraq, due to the recent developments in the country.Footnote7 According to many scholars and analysts, sectarian policy and Islamism are essential concepts defining present Shi’a politics.Footnote8

The relationship between the state and religion is widely presented in various academic papers, focusing on the role of political Islam and secularism within the modern state,Footnote9 explaining that ‘secularism does not amount to the complete privatization of religion and its exclusion from public life and morality, but rather merely the detachment of religious doctrine from the process of constructing coercive laws’.Footnote10 From the historical perspective, precolonial Muslim society governed by Sharia law criticizes the state.Footnote11 The Islamic state which is ‘organized organically around God’s sovereignty with Sharia as the moral code’Footnote12 is then not compatible with the concept of the Western modern state. The connection between Islam and politics and deep analysis of the concept of Islamism already have been researched,Footnote13 also in the specific case study of Shia-Islamism in Iraq.Footnote14

Further, sectarianism as a reaction against the imported state or Western influence on the region is discussed by Hashemi, Mahmood, and Postel,Footnote15 while Cammett, Matthiesen, Weiss, and White perceive the sectarian approach as a consequence of ‘incomplete or failed adoption of liberal governance’.Footnote16 Dodge and Mansour, investigated the role of sectarianism in Iraq’s post-2003 political system, questioning the Iraqi parliamentary elections and the role of sectarianism within the process of post-election negotiations and coalition building. As an example, the former Iraqi prime minister (PM) Nouri al-Maliki, in his two terms in office not only centralized his power,Footnote17 but also challenged the democratic trends applied sectarian policy, which later contributed to the emergence of an Islamic state in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).Footnote18 The concept of sectarianism is explored in more depth by Valbjørn, who distinguishes between sectarianism, post-sectarianism, and anti-sectarianism and their roles during the specific period of Iraq’s political system evolution post-2003.Footnote19 Saouli connects sectarianism to a political process, claiming that political sectarianism is ‘the mobilization of sectarian communities—their emotions, memories, beliefs, aspirations, and fears—for political goals’Footnote20 which is typical for the Iraqi Shia political parties. The evolution of Iraqi nationalism (together with Islamism and sectarianism) is discussed by Sidahmed,Footnote21 while Clausen acknowledges that ‘Iraqi state-based nationalism is used to signal opposition to the ethno-sectarian status quo and a desire for an Iraq based on unity’,Footnote22 which is consistent with conceptualization in this article. Dodge and Mansour then build upon the Brubaker and Cooper analytical rubric, where nationalism and secularism (together with sectarianism) can be perceived ‘relational categories of practice, ways of ordering a specific society deployed by those in competition with each other for the allegiance of a population contained within a given political field’.Footnote23 Finally, nationalism is often examined in the early post-2003 eraFootnote24 (such as the case of sectarianism), leaving a knowledge gap to research a perception towards nationalism in later period, and more specifically post-2021 as in the case of this research. Several authors exploring the connection between the Shi’a political parties and Shi’a militias under the umbrella of Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), such as Cole (2007),Footnote25 Hubbard (2007),Footnote26 Thurber (2014),Footnote27 Cigar (2015),Footnote28 or Rached and Bali (2019).Footnote29 A broader perspective of the key Shi’a figures and political parties is discussed by Katzman and Humud (2015).Footnote30 Finally, the relationship between the civil society, mainly represented by the Iraqi Federation of Oil Unions (IFOU), and the governing Shia actors such as PM al-Maliki is researched by Isakhan.Footnote31

Although the mentioned studies discuss the value anchorage through historical perspectives, they do not reflect the post-2021 parliamentary election development, which led not only to the consolidation of power by more traditional political actors such as State of Law Coalition (SLC) or Fatah AllianceFootnote32 and the sidelining of rivals like Sadrist Movement but also empowered a new player: Imtidad political entity. Thus, this article provides a new and innovative classification of the following Iraqi Shi’a political parties: Islamic Da’wa Party (the main ‘wing’ led by Nouri al-Maliki), Badr Organization (Hadi al-Amiri), SadiqunFootnote33 (Qais al-Khazali), Harakat HuquqFootnote34 (Hossein Moanes), Al-Hikma (National Wisdom Movement, Ammar al-Hakim), Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI, Humam al-Hamudi), Sadrist Movement (Muqtada al-Sadr) and the Imtidad political coalition (Alaa al-RikabiFootnote35). These political actors were chosen according to their current position in the Iraqi parliament or their historical importance within the Shi’a political and religious framework. The subjects of analysis were selected on the level of individual political actors/parties, not the whole coalition, with the exception of Imtidad. The reason for the inclusion of Imtidad in the analysis is to cover the segment of Shi’a public representation (with its strongest support in the parliament across the Tishreen parties) emerging after the Tishreen 2019–2020 protests, and challenging the status quo and the surviving political reality.Footnote36

In this article, the main focus is to classify the aforementioned parties by challenging existing preconceptions of the religious (Islamic)-secular and sectarian-nationalist division where the Islamic and sectarian policy is one of their main offers to its supporters and public, largely relying on an ethno-sectarian framework. This contribute not only to a deeper understanding of the Iraqi and Shi’a political scene in general but also to the theoretical discussion of the cleavages in Islamic society. Classification of these two divisions within the context of the Iraqi political scene will provide a useful contribution to plug the gap in the topic of classification of Middle Eastern parties in terms of the religious-secular division. However, within the context of various demographic structures of the Iraqi population and its representation by mostly Shi’a, Sunni, and Kurdish political parties, this article offers a new perspective of sectarian-nationalist classification with the main Iraqi Shi’a political parties at the centre of the research. Moreover, this article helps to better understand those parties as dominant actors within the Iraqi political environment. Hence, the placement of the individual actors on the axes reflects the societal cleavages inside society, showing the differences between actors’ positions. Deep divisions can be seen, indicating sectarian approaches; however, attempts to ‘build bridges’ can also be observed, signalling a more territorial nationalist approach.

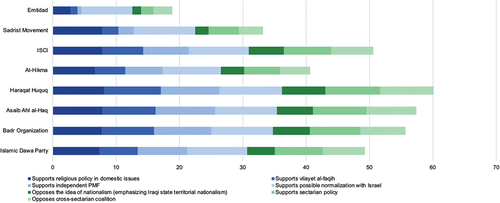

More specifically, this research examines two areas of focus—the religious (on Islamic-secular axis) and sectarian (on sectarian-nationalist axis) dimensions, dividing the research subjects into those more inclined to secular-nationalist tendencies (which are less religious and sectarian) in one corner of the axial cross, or towards Islamic-sectarian tendencies in the other corner (which are more religious and sectarian). The data collection is based on two main methods. Firstly, the mapping of Iraqi Shi’a political actors is done through expert survey data collection, working with its classification within the Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist axes (see ) by several political experts on the Iraqi political scene. Secondly, the data obtained are complemented by 14 semi-structured interviews with various political experts and politicians from several of the mentioned parties. These interviews were conducted from January to December 2023, mostly within the field research in the Iraqi cities of Erbil and Sulaymaniyah and through phone calls with political experts based in the rest of Iraq, Jordan, and the United Kingdom. To triangulate the evidence, the data were complemented from online sources, speeches, and posts, mainly through social media (such as Telegram, Twitter (X) channels, and Facebook posts), and official media platforms content analysis. The analysis focused primarily on the aforementioned leaders of individual political parties, who often determine the ideological direction of their political entity. The positions of some ordinary members were also reflected. Finally, data from opinion polls conducted under the leadership of Ali Taher al-Hamud and Munqith Dagher were included in the research.

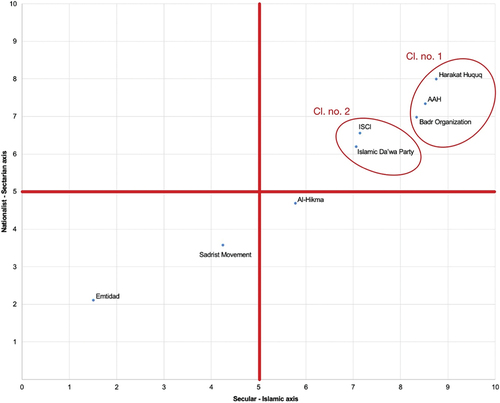

Figure 1. Position of the individual Iraqi Shi’a political parties on the nationalist-sectarian and secular-islamic axes.

The main results of this research report the positions of these parties on key issues such as their approach to intra-religious issues, sectarianism and nationalism, and distinguish clusters of pro-Iranian political actors (Badr Organization, AAH, Harakat Huquq), traditional parties (Islamic Da’wa Party, ISCI) and the special position of Al-Hikma, Sadrist Movement and Imtidad coalition, bringing new perspectives on these key issues within the Iraqi Shia politics.

Iraqi political system

Within the context of the Middle East, the Iraqi political system is uniqueFootnote37 and is classified as consociational (or semi-consociational),Footnote38 parliamentary, and multi-party system.Footnote39 The ethno-sectarian system of Muhasasa Ta’ifiya, established after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, is the main source of sectarian apportionment, based on specific conditions and the composition of Iraqi society. The idea of the distribution of individual key political positions according to Muhasasa Ta’ifiya was to bring a proportional representation to Shi’a, Sunni, and Kurdish political actors and to avoid the return of state authoritarianism. The idea is to share power between all the components of Iraq, based on their ethno-sectarian and religious affiliations. As in their highest positions, the post of the Iraqi presidency is always reserved for the Kurds (with Sunni and Shia deputies), the parliament speakership is designed for the Sunnis (with Shia and Kurdish deputies), and the post of PM is intended for the Shias (with the Sunni and Kurdish deputies).Footnote40 These divisions are just the ‘top of a glacier’ when all other governmental and provincial positions and bureaucracy are reserved for specific ethno-religious groups including the minorities. However, this division of power is functional more on paper rather than in reality. Thus, Muhasasa Ta’ifiya did not succeed in preventing either a sectarian civil war between 2006 and 2008, the emergence and existence of ISIS, or massive demonstrations beginning in 2009, erupting sporadically, with their peak in 2019.Footnote41 In terms of classification, significant trends occur within the individual political forces. Firstly, the former PM Nouri al-Maliki (and the current leader of one of the wings of the Islamic Da’wa Party) used the policy of sectarianism and pointed out the differences between the Shi’as and Sunnis. The sectarian policy against Sunnis manifested itself, for example, in the violent suppression of protests in 2013 which led to the Hawija massacre. Later, the rise and existence of ISIS were used as a pretext for government interventions against Sunnis, which only paved the way for more religious extremism. Therefore, al-Maliki’s policy deepened further still in his second term in office from 2010 until 2014.Footnote42 The end of the sectarian system of Muhasasa Ta’ifiya in Iraq, which is seen as a tool for corruption and nepotism, was also one of the demands of the Tishreen protest movements established in 2019. According to Dodge and Mansour, during that time (and also since then), the elites in Baghdad changed the ‘symbolic capital of sectarianism to coercive capital of suppression’ to save their positions secured by the Muhasasa system. The authors also pointed out that from Muhasasa Ta’ifiya (sectarian apportionment), the system transformed into Nidham Muhasasa (systemic apportionment).Footnote43 Moreover, Haddad pointed out that the ‘muhasasa system was never just a muhasasa “ta’ifiyyah” (sectarian apportionment): it was always also a muhasasa “hizbiyyah” (party apportionment)’,Footnote44 where the individual political actors securing the posts inside the establishment accepting the main rules of governing relations between the sects.Footnote45 Thus, the evolution of the sectarian apportionment and competition between the Shi’a, Sunni, and Kurdish political parties, officially representing ethno-religious groups in Iraq, recreated the system where elites sought the preservation of the Muhasasa system in Iraq and the consolidation of their political power. Since 2003, the Iraqi political system of ethno-religious consociationalism or sectarian apportionment (Muhasasa Ta’ifiyya) has been challenged by political actors (and their actions) and Iraqi citizens. The purpose of this system of ethno-religious division of the Iraqi state was to create equal opportunities for the political representation of all ethnic and religious groups, beginning with Shi’a and Sunni Arabs and Sunni Kurds.Footnote46 However, Iraqi state institutions have become nothing more than hollowed-out shells, with no higher authority in a country where the power of the tribal and clan system and the power of religious leaders continue to persist.Footnote47 Also, in Middle Eastern structures, political parties often lack a political apparatus and institutions and must be understood in a different sense from the way we see the traditional organization of Western/European political parties. The state structures and ethno-sectarian system are then used as a tool for achieving the goal of political elites. Thus, it is in their favour to preserve the Muhasasa system, leaving the Tishreen movement parties such as Imtidad as the only power emphasizing the need for a change in the status quo.

Within the Iraqi political context, political parties cannot be understood in the classic Western concept of a political party. The lack of internal structure, party apparatus, official institutions, and wide leadership is typical in Iraqi political parties. Furthermore, it is more a group of people with the same or similar economic interests that they want to achieve and secure through political processes, connections, and power. Moreover, they can be characterized by having one charismatic leader with strong decision-making power within the party or movement, following his interests and the interests of the group around him. As Van Veen, Grinstead, and El Kamouni-Janssen pointed out, the Iraqi Shi’a political parties have tended to be largely personality-based, with no space for two or more dominant leaders, instead having more modest personalities within the party structures.Footnote48 In this article, the goal is to discover how the Iraqi political parties profile themselves through their approaches towards religion, focusing either on one specific group of the population (triggering processes of sectarianism) or emphasizing Iraqi state territorial nationalism by ‘building bridges’ between the majority Shi’a population and Sunni, Kurdish and minority groups in Iraqi society.

Iraqi Shi’a political actors

The main Iraqi Shi’a political parties differ due to their distinct historical development, legacy, and legitimacy, especially during the Saddam Hussein era from 1979 to 2003 and their role in post-Saddam Iraq. After the toppling of the Baathist regime in 2003, some of these parties have taken different stances towards US forces and administration. For example, while the Islamic Da’wa Party (and Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq—SCIRIFootnote49) worked pragmatically together with these ‘liberation’ forces in the form of US and United Kingdom administrations,Footnote50 the Sadrist Movement (together with Sunni insurgents) stood against them.Footnote51

There is no clear boundary between religious and political leaders in Iraq. Within the Iraqi political scene, there are two big religious centres of power represented by marja’iyyah in Najaf, led by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, and the Shi’a religious school in Qom, represented by Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The influence of two traditional religious families—Hakims and Sadrists—also needs to be mentioned as the stance of these parties towards Tehran and Qom as well as religious authorities in Najaf and Iraqi traditional families is essential for understanding their common functioning. Moreover, in post-Saddam Iraq, Shi’a clerical authority has evolved as a largely autonomous tradition that plays a crucial role within social and political structures.Footnote52 As Rojhelati pointed out, there are ‘three different views on the relationship between the Shiite religious elite and politics’, which reflect the role of the Shi’a clerical authorities within the political processes. The first view categorizes mainly the Najaf religious elites such as Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei and al-Sistani as those who do not want to intervene in politics as the ‘quietists’. On the other hand, the second view identifies some Shi’a religious leaders such as Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as those who directly intervene in political processes as ‘activists’. The third view rejects this dichotomy and division into ‘quietists’ and ‘activists’, and presents the argument that Shi’a religious leaders intervene in politics whenever there is an opportunity to do so. An example could be the occasional actions of al-Sistani, who campaigned in the Iraqi elections in 2005 and has sometimes shown (dis)approval of previous ministersFootnote53 as well as advocating the blocking of Maliki’s bid to run for a third term as Iraqi PM or issuing the fatwa calling on Iraqi citizens to defend their country its sacred places and honour of the citizens.Footnote54

Currently, there are several actors, highly influenced by Iranian policy, receiving commands from Tehran, and respecting and following the religious authority of vilayet al-faqih. Among them are the pro-Qom armed forces which have been part of politics since the 2018 parliamentary elections,Footnote55 and are mostly gathered within the Fatah coalition. The most vocal position of Tehran in Baghdad is held by the AAH militias led by Qais Khazali. Not only is there a connection to the al-Maliki sectarian policy of politically deepening the differences between Shi’as and Sunnis, but Khazali is also known for his strong anti-Kurdish stance. However, historically the Iranian marja’iys dominated the Iraqi marja’iyyah and made no distinction between Iraq and Iran as state entities, considering all its community as ‘the faithful’.Footnote56 The formation of modern nation-states changed the concept of umma, creating differences between the religious authorities in both states.

Conceptualization and classification of the main political parties—Middle East and Iraq

Conceptualization and classification of the main political parties are essential for understanding the value anchoring of the parties, their position on certain issues, prevailing discourses, considerations on legislation in parliament, the building of coalitions, and the self-promotion of their image. In its context, the Middle East is highly various in its political system classifications, where individual states are governed by different types of political arrangements, ranging from theocracies to parliamentary republics. In general, ‘the region suffers from a deficit of the party competition associated with democracy’.Footnote57 The region is dominated by autocratic regimes, where leaders remain in their positions for decades due to their family ties, coupled with the support of elites and the military.Footnote58 The classification of Middle Eastern political parties has been discussed by Aydogan, who argues that the ‘religious-secular divide is the primary dimension of political party competition’.Footnote59 He also mentions the axis of conservative vs leftist classification, which is often connected to the religious-secular axis. Several other authors classify the political parties into conservative/Islamist versus leftist/secular, such as Eyadat (2015),Footnote60 Hamid (2014),Footnote61 Hamzawy (2017),Footnote62 and Lust and Waldner (2016).Footnote63 Finally, so far little has been written on Middle Eastern (and especially Iraqi Shi’a) political parties in such a broad comparative perspective, and many of the themes are hitherto under-studied; yet, they are crucial if we are to understand the intricate dynamics of regional politics past and present.Footnote64

This article determines its classification, based on consultations with several political experts, politicians, and journalists who cover the Iraqi political scene. The aim is to challenge existing preconceptions of Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist division by its application toward key Iraqi Shi’a political parties while resisting the simplistic narratives of these concepts. In particular, the religious and sectarian categorization is justified by the more numerical representation of the Iraqi Shi’a political scene. Some scholars argue that ‘Shiites have always swung between two main approaches: The first calls for the formation of an independent Shiite political identity, while the second calls for the establishment of some sort of a secular state and the participation of all parties in building itFootnote65’. Also historically, across the Middle East and in Iraq specifically, the competition between Arab Nationalism, state-based nationalism, Islamism, and sectarianism has utilized ideology, coercion, and state institutional capacity in this interactive struggle imposed competing categories of practice.Footnote66 So, what do these pre-conceptions mean and are they applicable to the Iraqi Shi’a political actors?

Delimitation of classification axes

Islamic-secular axis

The first axis reflects the Islamic-secular approach and its involvement in Iraqi political parties’ agendas as a major dimension of the country (see ). The religious dimension is further divided into two different categories: more internal ‘domestic’ issues and external religious issues on the Iraqi political scene (and ‘outside’ of it).Footnote67 The internal issues concentrate on the position of the individual Shi’a political actors towards the implementation of religious principles in the lives of individuals or families. More specifically, the domestic approach targets the agenda of allowing men to have more than one wife and the stance of the political actors against the legalization of alcohol (i.e. making the drinking of alcohol legal). Within the ideological Islamic-secular axis, the more Islamic parties would strongly support the integration of these religious principles into more ‘domestic’ political issues, while more secular parties would have a more liberal posture towards it. The domestic approach is completed by the ‘external’ part of the religious-secular stance of the chosen actors. This involves their position towards the Iranian concept vilayet al-faqih,Footnote68 and their position on the concept that PMF should operate independently and parallel to the Iraqi army and police (and not be included under its operational control). Finally, the issue of normalization relations with Israel is considered a religious matter since this question is widely discussed not only on the Iraqi political scene but especially within the Iraqi Shia political circles. Shia political actors often perceive Israel by religious optics, labelling the Israeli government as Zionist, following the Iranian foreign policy.

The religious-secular divide represents the role of religion within the design and implementation of Iraqi political entities and actors. Within the concept of this article, the religious sphere is limited by the Shi’a branch of Islam, emphasizing a clear difference between Shi’a and Sunni Islamism. While Sunni Islamism emerged from the ‘defiance of postcolonial, authoritarian nationalist regimes and their socioeconomic policies and international alignments’, Shi’a Islamism built its approach on sect-centricity as a response to long-term political, economic, and cultural discrimination.Footnote69 Further, in Shi’a Islamism, there is the ideological concept of mathlomiya [مظلومية], which dates back 1400 years to the killing of Imam Ali and represents the victimhood of the Shi’as since the battle of Karbala 680 AD. This concept frames the ideology of the all-Shi’a political parties still today,Footnote70 while ‘Shi’as are more likely to speak of sectarian discrimination in pre-2003 Iraq whereas Sunnis are more likely to do the same with regards to post-2003 Iraq’.Footnote71 In terms of the Shia Arabs’ approach towards the state, their loyalty to Iraq increased after the change of political regime in 2003.Footnote72 This article researches the role of Islam within Iraqi political processes, adopted by various political actors, where political Islam tends to accept some features of modern politics such as the state, its institutions and the use of technology.Footnote73 The state apparatus is a version imported from Western societies, so the modern Islamist vision in terms of a homogenized Islamic public sphere and a codified Islamic legal system is linked to the concept of the modern state rather than pre-modern Islamic political tradition.Footnote74 Political Islam is the result of Islamic traditions’ dual processes of nationalization and reformation/westernization, where the concepts of religion, nationalism, and secularism are essential.Footnote75

As other examined concepts, secularism not only separates public and private approaches towards religion but is also open to transformations allowing religion to reform. Secularism thus supports religion as more private, moral, and ethical, rather than legal, political, and adjudicative.Footnote76 An-Na’im then supported the narrative of Abd al-Raziq’s (1925) Islam and the Foundations of Government, calling for ‘separation of state and religion rather than experimentation with their continued interdependence’.Footnote77 Within the Iraqi context, the terms ilmaniyya (secularism) and madanī/al-dawla al-madaniyya (civil/the civil state) also need to be presented. As Robin-D’Cruz and Mansour pointed out, the ‘civil state’ frequently functions as a strategic discourse whose utility for a diverse range of ideological actors lies primarily in its ambiguity, while secularism ‘denotes a more-or-less coherent political doctrine’.Footnote78

Sectarian-nationalist axis

The second axis represents the issue of sectarian-nationalist division (see ). The sectarian dimension explores the position of the individual actors on Iraqi state territorial nationalism (and on using it as a mobilization tool), their position on sectarian policy (and, again, on using it as a mobilization tool), and the position of the parties on sectarian policy in terms of willingness to create pre-election cross-sectarian coalitions with Sunni and Kurdish parties/coalitions/alliances.Footnote79 On the one side, there are ‘digging trenches’ between individual ethno-sectarian groups, promoting sectarianism and hatred towards other ethno-religious groups and empowering ethno-religious nationalism of the population. On the other side, there stands the preservation of national unity as a whole, including the various minorities, based on the belief that all inhabitants of a chosen territory should share a common national identity, regardless of ethnic, linguistic, religious, cultural, and other differences. Hence, the location of the individual political parties on the axis shows their reflection of societal cleavages inside society, either deepening the gaps or, on the contrary, ‘building bridges’ between them. Hence, this understanding of sectarianism does not refer to sect-coded violence and entrenchment at a societal level, which was the phenomenon of the Iraqi civil war with its peak in 2006 and 2007.Footnote80 In terms of nationalism, we can speak about supporting Iraqi state territorial nationalism, where all the inhabitants share a common national identity, regardless of their ethno-religious background.Footnote81 As Barth points out, the sectarian processes strengthen both the internal coherence of each religious group as well as the boundaries that divide these groups from each other.Footnote82,Footnote83

Methodology

Several methodological techniques are widely used in the political sciences to uncover ideological positions or the value anchoring of political actors and parties such as discourse analysis, content analysis, or roll call vote analysis. This article uses an innovative combination of data collection from expert surveys complemented by 14 semi-structured interviews, creating a new dataset leading to the classification of the main Iraqi Shi’a political actors. Unless otherwise noted, the interviewees’ identities were kept anonymous. Firstly, due to security reasons and secondly to enable the most accurate responses. To triangulate the evidence, the data were complemented from online sources, speeches, and posts, mainly through social media (such as Telegram, Twitter (X) channels, and Facebook posts), and official media platforms content analysis. To reflect the approaches of the Iraqi population towards examined political parties, data from opinion polls conducted under the leadership of Ali Taher al-Hamud and Munqith Dagher were also included in the research.

Expert survey data acquisition was conducted in the Kurdistan region of Iraq and the rest of Iraq from March to May 2023. On-the-ground surveys and interviews were conducted with Iraqi political experts, journalists, and activists to discover how the parties are perceived in terms of chosen categorization criteria of Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist division by the surveyed sample of people. This methodological approach aimed to obtain the subjective perspectives of these political experts, which could shape the level of understanding of these concepts associated with the individual Iraqi Shi’a political parties. Moreover, the expert surveys introduce more local perspectives, challenging these concepts and their Western understanding by domestic elites. This study used the approach of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, which was sent to 37 Iraqi political experts, with 21 of them completing it, representing a 56.8% return of the responses. These experts were selected due to their long-term focus on this issue and approached the author’s contacts from the Institute of Regional and International Studies (IRIS) at the American University in Iraq, Sulaimani (AUIS). These experts come from academic institutions and think tanks such as The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Chatham House, and The Century Foundation. This survey aimed to find out how the concepts of religion versus secularism and sectarian versus nationalist divisions are perceived by the people. Although within the interviews some politicians were included, the major focus was oriented towards independent political experts.

The expert survey consisted of five questions based on the research objectives, which were reflected by the research questions mentioned in the introduction of this article. After each question, the respondents were presented with a 10-point Likert-type scale from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. Respondents were asked to select how the main research objects, the aforementioned Iraqi Shi’a political parties, would behave in the given situations. For example, they were asked to determine the position of each Iraqi political actor towards the issue of sectarian policy, with 0 points representing strong opposition to the idea of sectarian policy and its use in their agenda, while 10 points represented full support for it.

The answers in the form of quantitative data from the expert survey were then converted into a table, where the averages (see Table A1) and standard deviations (see ) of the values for each research question were calculated. Subsequently, two aggregated indicators were created, representing the two areas of the research focus: the religious dimension (including the importance of the implementation of religious principles in the life of individuals/families and position on the external religious issues), and the sectarian dimension (including position on Iraqi state territorial nationalism and sectarian policy). The averages relating to each aggregate indicator are shown in on the Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist ideological anchorage axes. Finally, the outcomes represent the ideological anchorage of the mentioned actors in the post-2021 parliamentary elections, involving changes within their ideological positions over time, in response to events on the Iraqi political scene.

Additionally, 14 semi-structured interviews were conducted with various political experts and politicians from some of the mentioned actors such as the Fatah coalition or Independents.Footnote84 Of these 14, 7 were conducted in person and 7 via phone. These interviews were conducted between January and December 2023, mostly during field research in the Iraqi cities of Erbil and Sulaymaniyah and through phone calls with political experts based in the rest of Iraq, Jordan, and the United Kingdom. Some of the interviews followed up on the completed expert questionnaire. Their main objective was to supplement the quantitative data obtained from the expert survey with thematically sorted qualitative explanations of some research gaps. The other prominent methods capturing the ideological position of individual political parties like roll-call vote analysis were excluded due to the inaccessibility of obtaining this data, particularly from the ranks of the Iraqi parliament. The data collection was complemented by social media and official mediaFootnote85 content analysis, and outcomes of opinion polls aiming at perceptions of Iraqi society towards political processes in the country. The analysis focused primarily on the aforementioned leaders of individual political parties, who often determine the ideological direction of their political entity. The positions of some ordinary members were also reflected. In terms of content the analysis aimed at the approaches of these actors within the frameworks of the Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist approaches. During the analysis of the speeches, the main focus was on the similarities and differences between the results and outputs from the expert questionnaire and the interviews. Finally, to reflect the voice of Iraqi society towards examined actors, the data from opinion polls were added. One limitation of the methodology used is the non-coverage of the responses of some political experts, especially from Baghdad and the southern Shi’a part of Iraq. Another limitation is the subjectivity of the answers, which are based on the perceptions of the different political parties.

Results

Firstly, almost all of the respondents made distinctions between ‘the more traditional’ political actors like the Islamic Da’wa Party, Fatah political parties (such as Badr Organization, AAH, and Harakat Huquq), and ISCI on the one side, while Al-Hikma, Sadrist Movement and Imtidad (which was created in 2019) were put on the other.Footnote86 In general, there is a clear correspondence between the Islamic and sectarian approaches on the one hand and the secular and nationalist approaches on the other. Also, there is an obvious cluster (see Cl. no. 1 in ) of the pro-Iranian political parties, where Harakat Huquq is the party most inclined towards Islamic and sectarian policies on the ground. The second cluster is created by the Islamic Da’wa Party and ISCI (see Cl. no. 2 in ),Footnote87 which in this respect may indicate similar approaches by these parties to the stated research objectives. Finally, Al-Hikma, Sadrist Movement, and Imtidad (as a new political coalition) tend to accentuate less the religious and sectarian policies (and in the case of Imtidad actively stand against Muhasasa Ta’ifiya, which is explained below).

The approaches of individual political actors towards chosen topics reflecting the religious (represented by the blue shades in ) and sectarian (represented by the green shades in ) ideological anchorages, perceived by the various political experts, are more visible in the case of . Finally, the higher the value on the axis, the more political actors gravitate towards Islamic and sectarian politics. The lower value thus indicates the inclination of these actors towards a secular and Iraqi state territorial nationalist approach. Except Imtidad, we can see that all other Iraqi Shi’a political actors have a similar position towards Iraqi domestic policy, in terms of religious issues. However, they differ in their religious foreign policy.

Specifically, we can interpret that Harakat Huquq represents the actor with the highest tendency towards using Islamic and sectarian policies, followed by other pro-Iranian actors like AAH and Badr Organization. Those actors are then to some extent bound by their connection to the Iranian regime. With these actors, there is also the lowest willingness to normalize ties with Israel, which fits into the framework of their geopolitical orientation. There is also a clear difference between the pro-Iranian actors, who strongly oppose the idea of Iraqi state territorial nationalism, and the creation of a cross-sectarian coalition with Iraqi Sunni and Kurdish political parties. Generally, in terms of sectarian ideology, Al-Hikma, Sadrist Movement, and Imtidad are less inclined towards sectarianism. However, when it comes to the approach of the Sadrist Movement towards Islamism, I believe that their position should be more inclined towards Islamist policies. Especially when it comes to their conservative approach towards religious policy in domestic issuesFootnote88 and strong anti-Israeli stance, which further deepened since 7 October 2023, when the Israeli-Hamas war started. Comparing the positions of the Sadrist Movement and al-Hikma in , the Sadrist should be considered as more Islamic than al-Hikma, considering more ‘hardline’ approach towards domestic and foreign Islamic issues. On the other hand, al-Hikma has better relations with Iran, which in terms of Sadrists could be marked as highly complicated. I also believe that the position of Sadrists on those axes is also influenced by their rejectionist attitude towards independent PMF and vilayet al-faqih. Also, as one respondent pointed out: ‘Competing Shi’a factions approach these questions instrumentally and most of their strong positions are entirely negotiable if there is a question of achieving more power or a greater share of government posts and resources’.Footnote89

Finally, the point about the generation gap between the ruling Shia political elite and Iraq’s major Shia population needs to be further explained. Leaders of individual Shia political parties such as Nouri al-Maliki, Hadi al-Amiri, Ammar al-Hakim, and Humam al-Hamudi represent the older generation of Iraq’s Shia ruling elite. Their perceptions were deeply influenced by the period of Baathist rule, when major of those leaders took a refugee and lived in exile in neighbouring Iran or were oppressed by Baathists. Hence, when they came to power in post-Saddam Iraq, they seized the opportunity for the Shia to dominate the Sunnis after years of Sunni despotism.Footnote90 However, at least 40% of Iraq’s population is under the age of 15,Footnote91 so their experience with the Baathist rule is often blurred. The needs and demands of the youth are often not heard and reflected by the older generations of Shia party leaders. The gradual distrust from the younger generation then culminated in the already mentioned Tishreen protests in 2019, and the long-standing frustration then contributed to the inclusion of the Imtidad political platform in the Iraqi parliamentary elections in 2021. However, state power is concentrated in the hands of older Shia men who are out of touch with Iraq’s majority Shia youth population’s needs and visions. Thus, when it comes to opinion polls, the highest percentage of respondents would vote in Iraqi parliamentary elections in 2018 for a bloc, coalition, party, or individual with a civil/secular agenda (24,3%), followed by votes for independent autocrats (23,9%). These groups are followed (by a relatively large gap of 9%) by the group that would vote for a bloc, coalition, party, or individual backed by religious authority (14,8%).Footnote92 On the contrary, only 4,6% of respondents would vote for the bloc, coalition, party, or individual with a religious sectarian agenda and 2,3% for the bloc, coalition, party, or individual with ethnic/nationalist loyalties.Footnote93 Thus, comparing the approaches of the main political actors and the Iraqi population, one can see a huge difference in attitudes within the Islamic-secular and sectarian-nationalist anchorages.

Islamic-secular axis

Approach towards religious policy in domestic issues

Regarding the first research question about the importance of the implementation of religious principles in the life of individuals/families, all of the ‘traditional’ parties can be categorized as ‘religious’ when Islam is their main source of identity,Footnote94 following their respective religious authorities (like in the case of a religious centre in Qom by parties involved in the Fatah coalition). Concerning the religious and political affairs and their overlaps, one of the respondents divided political actors into three groups: 1) Full overlap of religious and political affairs—Badr Organization, AAH, and Harakat Huquq; 2) Attempts to separate religious and political processes—Islamic Da’wa Party and Sadrists Movement; and 3) Complete separation between religious and political processes—Imtidad.Footnote95 Regarding the position of individual political actors towards Islamic-secular issues, one of the respondents answered that it is ‘hard to compare’ since ‘all of them exist in the area where being secular is taboo’.Footnote96 An example of a higher tendency towards Islamic discourse is condemning the form of celebration of Iraq’s National Day on the 4th of October 2023, pointing out on display devoid of values in terms of poor women’s clothes, against the core values of Islam.Footnote97 Majority of examined parties then condemned the Quran burning in Sweden throughout 2023.Footnote98 Also, during the Iraqi provincial election 2023 campaigns, the political actors within the Coordination Framework (CF) targeted the opposition platforms such as Qiyaam Civil Coalition which served as an umbrella of Democratic Forces of Change, accusing the individuals of supporting LGBTQ community (thus threatening the Islamic principles and Iraqi traditional family) or labelling them as Mossad agents.Footnote99 Strong anti-LGBTQ stance is then typical for the Sadrist Movement, often presented on its social media platforms.Footnote100 Muqtada al-Sadr also declared that ‘Iraq is a nation of Quran’Footnote101 When it comes to the protection of traditional religious values, Sadiqun (AAH) then again often targeted the Tishreen platform, accusing them of being infiltrated by the USA, claiming that ‘Men and women are gathering together and staying during the night without any morals, using drugs and alcohol’.Footnote102 On the contrary, some statements of Ammar al-Hakim, leader of al-Hikma show a more moderate approach towards women’s rights, calling for ‘Changing the environment and social heritage and the wrong interpretation of religious scripts like the Sunna and the Quran (limiting women’s rights) and supporting the authorities in their duty to protect women against violence’.Footnote103 According to Iraqi public opinion in 2021 on democracy and governance, 30% of respondents labelled themselves as ‘A very religious person’ and 62% as ‘A somewhat religious person’.Footnote104 At the end of 2023, 40% of the respondents feel a high religiosity in terms of their identity, while 55% feel moderately religious.Footnote105 When it comes to the relationship between religion and politics, in 2021 only 39% of respondents believed that Iraq should implement only the laws of the Sharia. In early 2023, only 44% of respondents trusted religious institutions in Iraq (while at the end of 2023, it was 64%Footnote106). On the contrary, 80% of respondents believed that religious practice is a private matter and should be separate from political lifeFootnote107 in 2021, while 77% endorsed the separation of religion and politics at the end of 2023.Footnote108

Approach towards vilayet al-faqih

The outcomes of the next research question focused on the positions on external religious issues. In terms of following the Iranian concept of vilayet al-faqih, the connection between the Iranian regime and the pro-Iranian actors (Badr Organization, AAH, and Harakat Huquq) is undeniable. Iranian role in Iraq slightly decreased after the 2019 nationwide protests and the assassination of General Qasim Suleimani in 2020. These pro-Iranian actors also lost a significant number of seats in the 2021 parliamentary elections (where Fatah, for example, lost about 31 seats).Footnote109 However, as of 2023, these parties are once again back on track, strengthening their position inside and outside of the state structures, using political leverage and involvement within PMF.Footnote110 Other respondents marked political parties, namely Islamic Da’wa Party,Footnote111 Badr Organization, AAH, Harakat Huquq, and ISCI as ‘radical Islamic parties, where the majority of them believe in the vilayet al-faqih in one way or another’.Footnote112 In the case of Haraqat Huquq, we can find postsFootnote113 mourning Ayatollah Khomeini, and highlighting the internal political arrangement of Iran as a possible model for future arrangements in Iraq. Despite the mentioned actors following the Iranian ideology, they are building upon their economic independence, exploiting Iraqi state structures and access to financial flows, and controlling significant businesses and border crossings. On the other hand, other responses described ISCI (together with Al-Hikma) as closer to the concept of marja’iyyah in Najaf, despite ‘being influenced by ISCI during their presence in Iran during the rule of the previous (Saddam’s) regime’. Regarding Imtidad, they are the furthest from marja’iyyah because they are Iraqis who have been affected by Iranian influence and formed a party during the protests, one of whose goals was to end Iranian hegemony over Iraqi political decision-making. Al-Sadr’s movement’s approach towards Iranian influence is much more complicated but rather far from the Iranian influence than other mentioned political actors (except Imtidad).

Approach towards independent PMF

Answering the research question about the position on the concept that PMF should operate independently and parallel to the Iraqi army and police, one of the respondents noted: ‘Islamic Da’wa Party deals with pro-PMF parties like AAH and Badr Organization as a threat when al-Maliki is afraid that pro-PMF parties will destroy his political gains, which are rooted in the 2021 parliamentary election results. Da’wa seeks to undermine the influence of those parties and control PMF on their own. In electoral circuits, where a candidate of the Islamic Da’wa Party was a winner, no other pro-PMF actors (like the al-Fatah coalition or Harakat Huquq) won and vice versa’. Thus, these relations ‘trigger hidden conflicts between those two sides, in which al-Maliki sees PMF not as an ideological force but some force that should be kept under the rule of the government, but only his government’. So, Islamic Da’wa Party would support the PMF, ‘only if they were under their control’. More particularly, a leaked audio file from July 2023 labels PMF ‘as being ‘the cradle of cowards’ according to the leader of Islamic Da’wa Party Nouri al-Maliki.Footnote114 Among the answers, it was also said that the Islamic Da’wa Party sees PMF as a militia that they can use for their purposes.Footnote115 Al-Hikma, the ISCI, and the Islamic Da’wa Party are less interested in dissolving the PMF, even though they know that their strength and continued hold on power today depend on the existence of these factions as a balance against the populist line that rejects Iranian hegemony. On the other hand, Badr Organization, AAH, Harakat Huquq, and ISCI ‘do not believe in the traditional Iraqi forces, and they see PMF as the bodyguard of the entire system and they are part of these forces’. In the case of ISCI, its leader Humam al-Hamudi was for example highlighting the role of PMF not only during the war against ISIS but also in the post-ISIS Iraq.Footnote116 Muqtada al-Sadr has different calculations about PMF and is trying to dissolve PMF and distribute its fighters among other security agencies in Iraq. He is also counting on the fact that if PMF is disband somehow, other parties (who are now opponents of al-Sadr) would not be able to remobilize their forces. On the other hand, if al-Sadr demobilize Saraya al-Salam, he can still mobilize his people within hours. So, dissolving PMF ‘would give him this advantage’.Footnote117 However, Muqtada al-Sadr oscillates between being a supporter and an opponent of this issue. As for the Imtidad Party, they are against these factions, although not explicitly.Footnote118 According to Iraqi public opinion in 2021 on democracy and governance, 59%Footnote119 of Iraqi people believed that armed groups outside of state control have either much more or slightly more control of Iraqi politics than the state.Footnote120

Approach toward possible normalization of relations with Israel

In terms of the possible normalization of ties with Israel, all traditional parties oppose this process. More deeply ‘it is more a community issue, than an ideological and political issue’, where ‘the majority of the community representatives state that to a degree no one can talk about the normalization of ties with Israel’Footnote121 or its ‘totally against the main beliefs and principles of the parties or because they want to avoid being treated as an enemy by the people in general, especially religious scholars’.Footnote122 On 26 May 2022, the Iraqi parliament unanimously passed the ‘Criminalising Normalisation and Establishment of Relations with the Zionist Entity Law’, criminalizing any form of normalization ties with Israel in Iraq.Footnote123 The bill had been submitted by Muqtada al-Sadr one month earlier. In April 2023, the Sadrists protested, accusing PM Sudani and Coordination Framework (CF) of being part of the Summit for Democracy (organized by the USA), together with the Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu.Footnote124 One of the answers claimed that ‘even if they are against it, they cannot say it, and wouldn’t talk about it publicly’.Footnote125 Since the outbreak of the Israeli-Hamas war on 7 October 2023, these trends have deeply intensified. The pro-Iranian Iraqi militias under the umbrella of Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI)Footnote126 have begun to launch drone and missile attacks against Israel, presenting the active approach of their foreign policy. On the contrary, the Sadrist Movement action has not crossed the border out of Iraq, organizing mass demonstrations and reinforcing strong anti-Israel rhetoric. Yet, they remained the dominant political force that condemned the Israeli actions towards the Gaza strip, while other political actors such as Fatah coalition parties also rhetorically opposed Israel, empowered by its geopolitical connections to Iran. On their official media, Sadiqun strongly condemned ‘what the Zionist entity is doing against the Palestinian people by committing crimes of murder and destruction, which represents the case of Zionist’s recklessness and undermining of the innocent blood and their negligence of humanity and sanctity of the blood (of Palestinians)’.Footnote127 Both, pro-Iranian Iraqi political actors and the Sadrist movement are competing over the dominance of the anti-Israel and anti-West narrative within the Iraqi political scene. Finally, strong support for Hamas activities against Israel came from Nouri al-Maliki,Footnote128 leader of the Islamic Da’wa Party.

Sectarian-nationalist axis

Approach towards nationalism

Regarding the issue of the position towards Iraqi state territorial nationalism and using it as a mobilization tool, the Sadrist Movement and Imtidad are seen as more ‘nationalist’ than other parties. A case in point is the name change of the Sadrists in April 2024 to the Shia Nationalist Movement. The name is meant to define itself against the parties within the CF that Muqtada al-Sadr sees as a pro-Iranian player, emphasizing his distinctiveness in supporting Iraqi nationalism. Al-Hikma is perceived as more nationalist than the rest of the traditional political actors. However, according to one of the respondents ‘all factions invoke nationalism and the nation-state, they just define it very differently and often corrode the state even while employing nationalist discourse’.Footnote129 On the other hand, others noted that ‘generally Islamic parties do not believe in the concept of citizenship or the nation, but rather they believe in the concept of the Islamic ummah. This issue varies from one party to another based on their interests and the political agenda that governs them’.Footnote130 As for the Imtidad Party, it is in favour of the concept of Iraqi citizenship as it represents the popular Iraqi sentiment that requires national belonging to solve its crises. In one of their posts, Imtidad praises a secular state: ‘To build a state where law and justice prevail and that accommodates everyone, personal freedoms must be protected as long as they do not infringe on the freedoms of others, and no party has the right to set limits or prevent freedoms guaranteed by the constitution’.Footnote131 Additionally, they supported the idea of Iraqi nationalism, saying ‘It is not permissible to formulate state policies, make decisions, or discriminate between Iraqi citizens in rights and duties on the religious or sectarian basis’.Footnote132 However, according to a public opinion poll done by IIACS in 2023, there is a declining number of Iraqis who identify themselves primarily as Iraqis, with a growing proportion leaning towards Islamic or sectarian identities.Footnote133

Approach toward sectarian policy

Answering the question on the position towards sectarian policy and using sectarianism as a mobilization tool, some of the respondents marked a ‘sectarian’ attitude as a tool for targeting its ‘audience’, which comes mainly from the Shi’a population, where there is a clear interdependence between religion and sectarian policy both targeting a specific religious group and distinguishing it from other ethnoreligious groups.Footnote134 Sectarianism is a part of the establishment of these partiesFootnote135 and also the ‘main product of those parties because, without it, they have nothing to sell to their followers’. However, their approach towards promoting sectarianism is different. By sectarian policy, some of the respondents see ‘special interpretations of religion, where Sunnis and Shi’as have their different interpretation of Islam’Footnote136 As one of the respondents pointed out: ‘As for sectarianism, Shiite or Sunni Islamic parties use sectarian religious feelings to seize people’s minds and emotions, thereby ensuring their votes even though the citizens themselves know the problems caused by these parties’.Footnote137 In this case, the transformation of the sectarian approach of the Sadrist Movement has to be mentioned. During the Iraqi civil war (2006–2008) ‘the Sadrist Movement militias Jaysh al-Mahdi (JaM) were one of the main sectarian actors,Footnote138 over time they became more civilized’.Footnote139 More specifically, Islamic Da’wa Party and Fatah parties (Badr Organization, AAH, Harakat Huquq) seem to rarely avoid using sectarian terms in their rhetoric, although they do so in a way that does not provoke people from other sects. Firstly, in one of his Telegram posts, Hossein Moanes highlights the position of Shiites in Iraq. In this post, Moanes is asking ‘Why should only Shiites sacrifice and not the others?Footnote140’ pointing out Sunnis and Kurds and their lack of sacrifice on the Iraqi issue. Secondly, in a leaked audio file from July 2023 leader of the Islamic Da’wa Party Nouri al-Maliki attacked Sunnis, labelling the majority of them as ‘spiteful’.Footnote141 On the contrary, the Sadrist movement sometimes tries to show deep respect for other sects and religions in their rhetoric. Imtidad has seldom used any sectarian terms within their political speeches, ‘promoting the necessity of enacting laws that criminalize and punish anyone who uses religion to sow division in Iraqi society’.Footnote142 Finally, according to the Iraqi public opinion in 2021 on democracy and governance, only 43% of Iraqi people were willing to vote for a party that represents a sect.Footnote143 The majority (51%) of respondents in public opinion reports believed that political sectarianism has once again emerged, casting a formidable shadow over the political landscape in Iraq.Footnote144

Approach towards willingness to create a cross-sectarian coalition

On the position towards sectarian policy in terms of willingness to create a pre-election cross-sectarian coalition with Sunni and Kurdish parties, the respondents answered that Shi’a actors, namely Al-Hikma, Sadrists Movement, and Imtidad are willing to create a pre-election alliance with Sunni and Kurdish parties. In the case of al-Hikma, its policy is more open to the case of Kurdish regional government (KRG) representatives such as PM Masrour BarzaniFootnote145 or President Nechirvan Barzani.Footnote146 As for the Sadrists, ‘even though Islamic principles are mentioned in most of their rhetoric, they seem to be more open to allying with non-Islamic parties. For instance, they allied with the Iraqi Communist Party as well as the Civil Democratic Coalition in 2018’. In 2021, Muqtada al-Sadr praised the need to form a national majority government, stating that ‘The next government is a government of law, there is no room for violation, regardless of whoever it may be. There will be no return to sectarian fighting or violence, as the law will rule’.Footnote147 In the post-election negotiations, he formed a cross-sectarian national majority alliance with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Taqaddum. The idea was preserved even after his withdrawal from the Iraqi parliament in June 2022, representing a form of alliance between the Kurds, the Sunnis, and the ruling Shia CF. However, with the continuous pressure from the Shia parties towards KRG, especially KDP,Footnote148 and the unresolved issue of the posture of the Iraqi parliament’s speakership,Footnote149 cross-sectarian cooperation is highly at risk. On the other hand, the ‘Islamic Da’wa Party and Fatah parties have always allied with parties whose political identities are similar to their own political identity’. As for Imtidad, ‘although all of its members belong to one sect, they seem to be far more open to allying with the parties that do not adopt the political Islamic identity. They have not allied with any Islamic party yet’.Footnote150 Imtidad did, however, form a pre-election coalition with the Kurdish Party ‘New Generation Movement’ in 2021.Footnote151

Conclusion

This article brings a new comprehensive analysis of the main Iraqi Shi’a political actors, whose actions in the political field are motivated by their ideological anchorage, often shaped by internal and external events. The Iraqi Shi’a political actors are a dominant force on the Iraqi political scene, where the role of Iran has a significant external influence that impacts the decisions of some of these parties concerning their domestic and foreign activities. In particular, these actors such as the Badr Organization, AAH, and Harakat Huquq, are the closest in their affiliation with the Iranian regime’s activities and influence in the region. These political actors are followed by more traditional parties such as the Islamic Da’wa Party or ISCI, which also have historical ties with Iran. Al-Hikma and the Sadrist Movement then have a specific position within the Iraqi Shi’a political scene. Finally, Imtidad as the newest politically relevant actor tends to be more towards secular and nationalistic policies.

Within the domestic context, there is no clear boundary between Iraqi political and religious leaders, as all of the large main Shi’a parties have relations with religious authorities. The parties’ positions towards Islam are shaped by the fact that they are using Islam as a mobilization tool. Their positions on vilayet al-faqih are more strongly held but are not relevant to any important decisions. Groups that do not support vilayet al-faqih for instance are still willing to work closely with Iran when it suits their interests. The ideological anchorage of the main Iraqi Shi’a political actors is thus often influenced by pragmatic decisions, which possibly lead to gaining more power or leverage, where all of these (except Imtidad) are already well known established in the Iraqi political system, so they know how to play the power politics game. Further, within the environment of various ethno-confessional groups of the population, sectarian rhetoric became a tool for the ethno-political mobilization of masses to support individual Iraqi political actors to gain or consolidate power and pursue their interests within the post-2003 period.Footnote152 This research also confirms that parties that tend to be more Islamic also have a higher tendency to be sectarian, from the perspectives of the political experts. However, the reality on the ground goes far beyond this simplistic dichotomy. For example, there are signs of pragmatic cooperation between the mentioned Shia political actors with their Sunni counterparts on the provincial level during the post-election negotiations aftermath of the Iraqi provincial elections held in December 2023. However, the voices of the Iraqi citizens are not fully represented, especially after the failure of Shia-led Tishreen protests from 2019 until 2020, which have called for more nationalistic and secular policies, later promoted by Imtidad.

In conclusion, this research provides a new and unique classification of Iraqi Shi’a political parties; however, there are many other research questions worth exploring. One area of interest, for example, would be to elaborate on the question of these parties’ willingness to build a coalition with Iraqi Sunni and Kurdish political actors who together shape the local political environment. It is then important to map the relationships between the different actors to find certain patterns and thus contribute to clarifying the very dynamic and complicated Iraqi political scene.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Benjamin Isakhan, ‘Shattering the Shia: A Maliki Political Strategy in Post-Saddam Iraq’. In: Benjamin Isakhan, (eds) The Legacy of Iraq: From the 2003 War to the ‘Islamic State’. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 2015): 67–81.

2 Ervin Van Veen, Nick Grinstead and Floor El-Kamouni-Janssen, ‘A house divided: Political relations and coalition-building between Iraq’s Shi’a’, CRU Report, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ (2017).

3 Ziryan Rojhelati, ‘The “Holy” Conflict; The Religious Authority and Intra—Shiite Tensions in Iraq’, Rudaw Research Center (2023).

4 Which was rebranded to the Shia Nationalist Movement on 11 April 2024. It is expected that Shia Nationalist Movement will compete in the upcoming parliamentary elections scheduled for 2025. Although, the more familiar name Sadrist Movement is preferred in this article.

5 Mohanad Faris, ‘Why did the Sadrists Withdraw from the Iraqi Political Process?’, Fikra Forum, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/why-did-sadrists-withdraw-iraqi-political-process (accessed January 10, 2024).

6 Al Monitor, ‘Muqtada al-Sadr threatens to withdraw from parliament’, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/06/muqtada-al-sadr-threatens-withdraw-parliament (accessed January 10, 2024).

7 Fanar Haddad, ‘Shia Rule Is a Reality in Iraq. “Shia Politics” Needs a New Definition’. The Century Foundation, 1 March 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/shia-rule-is-a-reality-in-iraq-shia-politics-needs-a-new-definition/ (accessed May 27, 2023).

8 However, the author mentioned another factor that explains the Iraqi political scene. These are divides between core and periphery, competing elite factions and status quo and reformist challengers. Haddad, ‘Shia Rule Is a Reality in Iraq. “Shia Politics” Needs a New Definition’ (2022).

9 Abullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, ‘Islam and the Secular State: Negotiating the Future of Shari’a’. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: Harvard University Press, (2008).

10 Andrew F. March, ‘Political Islam: Theory, The Annual Review of Political Science’ 18, (2015): 103–123. The author here refers to a previously mentioned work of An-Na’im: ‘Islam and the Secular State: Negotiating the Future of Shari’a’. March is here arguing that the statement of ‘secularism does not amount to the complete privatization of religion and its exclusion from public life and morality’ is ‘a misconception to which he attributes the widespread Muslim antipathy toward the idea of secularism’, p.113.

11 Wael B. Hallaq, ‘The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity’s Moral Predicament’. (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2013).

12 Jocelyne Cesari, ‘What is Political Islam?’, Lynne Rienner Publishers, CO, USA (2018), p.2.

13 Olivier Roy, ‘The Failure of Political Islam’. (Cambridge: Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1994).

14 Søren Schmidt, The Role of Religion in Politics. The Case of Shia-Islamism in Iraq, Nordic Journal of Religion and Society, 22, no. 2 (2009): 123–143.

15 Cesari, ‘What is Political Islam?’, (2018): 4.

16 Ibid.

17 Toby Dodge, ‘Iraq: From War to New Authoritarianism.’, (The International Institute for Strategic Studies, Routledge, 2012).

18 Isakhan, ‘Shattering the Shia: A Maliki Political Strategy in Post-Saddam Iraq’ (2015).

19 Toby Dodge and Renad Mansour, ‘Sectarianization and Desectarianization in the Struggle for Iraq’s Political Field’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs 18, no. 1 (2020): 58–69.

20 Adham Saouli, ‘Sectarianism and Political Order in Iraq and Lebanon’, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 19, no. 1, (2019): 4.

21 Abdel Salam Sidahmed, ‘Islamism, Nationalism, and Sectarianism’. In: Markus E. Bouillon, David M. Malone and Ben Rowswell (Ed.): Iraq: Preventing a New generation of Conflict. A project of the International Peace Academy. (London: Lynne Rienner Publisher, 2007), 71–88.

22 Maria-Louise Clausen,‘The Potential of Nationalism in Iraq: Caught between Domestic Repression and external Co-optation’. In: POMEPS Studies 38: Sectarianism and International Relations, (2020): 26.

23 Rodgers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, ‘Beyond “Identity”’, Theory and Society 29, no. 1, (2000): 1–47. In: Dodge and Mansour, ‘Sectarianization and Desectarianization in the Struggle for Iraq’s Political Field’ (2020), p.2.

24 For example, W. Andrew Terill, ‘Nationalism, Sectarianism, and the Future of the U.S. Presence in Post-Saddam Iraq’, U.S. Army War College: Strategic Studies Institute (2003) or Elisheva Machlis, ‘Shii-Kurd relations in post-2003 Iraq: visions of nationalism’. Middle East Policy, (2021):1–17.

25 Juan Cole, ‘Shia Militias in Iraqi Politics’. In: Markus E. Bouillon, David M. Malone and Ben Rowswell (Ed.): Iraq: Preventing a New generation of Conflict. A project of the International Peace Academy. (London: Lynne Rienner Publisher, 2007), 109–123.

26 Andrew Hubbard, ‘Plague and Paradox: Militias in Iraq’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 18, no. 3, (2007): 345–362.

27 Ches Thurber, ‘Militias as sociopolitical movements: Lessons from Iraq’s armed Shia groups’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 25 (5–6), (2014): 900–923.

28 Norman Cigar, ‘Iraq’s, Shia Warlords and their Militias: Political and Security Challenges and Options’, United States Army War College Press, US Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute (2015).

29 Kardo Rached and Ahmed O. Bali, ‘Shia Armed Groups and the Future of Iraq’, Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal 23, no. 1 (2019): 217–233.

30 Kenneth Katzman and Carla E. Humud, ‘Iraq: Politics and Governance’, Congressional Research Service report (2015).

31 Such as Benjamin Isakhan, ‘Civil Society in Hybrid Regimes: Trade Union Activism in Post-2003 Iraq’, Political Studies, 71 no. 2, 295–313 or Benjamin Isakhan, ‘Doing Democracy in Difficult Times: Oil Unions and the Maliki Government’. In Isakhan, B. (Ed.) The Legacy of Iraq: From the 2003 War to the ‘Islamic State’. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; New York: Oxford University Press 2015), 125–137.

32 With Islamic Da’wa Party being the core of SLC and Badr Organization the dominant player within Fatah Alliance.

33 Political wing of the Shi’a militia group Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), later referred to by this better-known name.

34 Political wing of the Shi’a militia group Kata’ib Hezbollah.

35 Although Alaa al-Rikabi officially holds the party’s chairman position, he is no longer in the party leadership. In February 2023, the vote of no confidence removed him from his post. He was replaced by Hamid Schiblau, who then soon disappeared from the political field. Imtidad remains internally divided over trivial political matters (Anonymous interview 13 in Sulaymaniyah on 28 November 2023).

36 Haddad, ‘Shia Rule Is a Reality in Iraq. “Shia Politics” Needs a New Definition’ (2022).

37 Middle East is divided between republics governed by autocratic regimes or individuals (such as Egypt, Syria or Iran), absolute monarchies such as Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Oman and semi-constitutional monarchies such as Jordan, Kuwait or United Arab Emirates. Thus, in wider comparison is Iraq’s political system (together with Lebanon and Israel) quite rare.

38 Eduardo Wassim Aboultaif, ‘Revisiting the semi-consociational model: Democratic failure in prewar Lebanon and post- invasion Iraq’, International Political Science Review, 41, no. 1, (2020): 108–123.

39 In its constitution, the Republic of Iraq is labelled as ‘a single federal, independent and fully sovereign state in which the system of government is republican, representative, parliamentary, and democratic’, Constitute Project: Iraq 2005, https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Iraq_2005 (accessed June 17, 2024).

40 Charles Tripp, ‘A History of Iraq.’ (New York: Cambridge University Press 2007).

41 Ibid.

42 More on the political development of Nouri al-Maliki in Hayder Said,‘The Politics of the Symbol: About the end of a national state culture, Arab Institute for Research and Publishing’, (2009).

43 Ibid.

44 Fanar Haddad, ‘The Waning Relevance of the Sunni-Shia Divide: Receding Violence Reveals the True Contours of “Sectarianism”’ in Iraqi Politics, The Century Foundation, ‘Citizenship and Its Discontents: The Struggle for Rights, Pluralism, and Inclusion in the Middle East,’ a TCF project (2019).

45 Ibid.

46 Dodge and Mansour, ‘Sectarianization and Desectarianization in the Struggle for Iraq’s Political Field’ (2020).

47 An example could be the long-term intra-Shi’a rift between Muqtada al-Sadr and Nouri al-Maliki, which occasionally surfaces as it did in 2008, 2014 and 2022.

48 Van Veen et al., ‘A house divided: Political relations and coalition-building between Iraq’s Sh’a’ (2017).

49 Which changed its name to ISCI in the middle of 2007, distancing itself from the Iranian influence. ISCI also announced following Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, shifting its loyalty from Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Benjamin Isakhan, Peter E. Mulherin, ‘Shi’i division over the Iraqi state: decentralization and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq’, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 47, no. 3 (2020): 361–380.

50 Zaid Al-Ali, ‘The Struggle for Iraq’s Future: How Corruption, Incompetence and Sectarianism Have Undermined Democracy’, (Yale University Press 2014).

51 Van Veen et al., ‘A house divided: Political relations and coalition-building between Iraq’s Shi’a’ (2017).

52 Harith Hasan al-Qarawee, ‘Shi’i Clerics and the Transformation of Authority in Iraq’, SFM I Bi-Weekly Research Seminars, Striking from the Margins Project, Phase I, SFM Project. Central European University, Oct. 6., 2017. https://religion.ceu.edu/dr-harith-hasan-shii-clerics-and-transformation-authority-iraq (2017).

53 Rojhelati, ‘The “Holy” Conflict; The Religious Authority and Intra—Shiite Tensions in Iraq’ (2023).

54 Harith Hasan al-Qarawee, ‘The “formal” Marjaʿ: Shiʿi clerical authority and the state in post-2003 Iraq’, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 46, no. 3, (2019): 481–497.

55 And to some extent since the 2014 election.

56 Al-Qarawee, ‘Shi’i Clerics and the Transformation of Authority in Iraq’ (2017).

57 Raymond Hinnebusch, ‘Political parties in MENA: their functions and development’. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 44, no. 2 (2017): 159–175, p.1.

58 Michele Penner Angrist, ‘Politics and Society in the Contemporary Middle East’. Lynne Rienner Publishers (2010).

59 Abdullah Aydogan, ‘Party systems and ideological cleavages in the Middle East and North Africa’, Party Politics 27, no. 4, (2021): 814–26, p.815.

60 Zaid Eyadat, ‘A transition without players: the role of political parties in the Arab revolutions’, Democracy and Security 11, no. 2 (2015): 160–75.

61 Shadi Hamid, ‘Political Party Development Before and After the Arab Spring’, 20 February 2014.

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/political-party-development-before-and-after-the-arab-spring/ (accessed June 10, 2023).

62 Amr Hamzawy, ‘Egypt’s Resilient and Evolving Social Activism, Carnegie endowment for international peace’, 21 February 2017. https://carnegieendowment.org/2017/04/05/egypt-s-resilient-and-evolving-social-activism-pub-68578 (accessed June 10, 2023).

63 Ellen Lust and David Waldner, ‘Parties in transitional democracies: authoritarian legacy and post-authoritarian challenges in the Middle East and North Africa’. In: Nancy Bermeo and Deborah J. Yashar, (eds) Parties, Movements, and Democracy in the Developing World. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016): 157–189.

64 Raymond Hinnebusch, Francesco Cavatorta and Lise Storm, ‘Political Parties in MENA: An Introduction’. In: Francesco Cavatorta and Lise Storm and Valeria Resta, (Ed.) Routledge Handbook on Political Parties in the Middle East and North Africa. London and New York, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, (2021): 1–12.

65 Ali Taher al-Hamud, هل الإسلام السياسي الشيعي يتّجه نحو العلمانيّة؟, Al Monitor, https://www.al-monitor.com/ar/contents/articles/originals/2013/11/iraq-shiites-secularism-sectarianism.html (accessed March 7, 2024).

66 Toby Dodge, ‘Introduction: Between Wataniyya and Ta’ifia; understanding the relationship between state-based nationalism and sectarian identity in the Middle East’, Nations and Nationalism 26, no. 1 (2019): 85–90, p.2.