Abstract

This article presents a case study from Liberia that focuses on the relationship between police reform and women, peace and security. It explores the Liberia National Police's (LNP) innovative efforts between 2003 and 2013 to recruit more female officers and to train a specialized unit to address sexual- and gender-based violence (SGBV). The analysis focuses on two key goals of the LNP: representation, through the Education Support Programme, and responsiveness, through the Women and Children's Protection Section. Assessed by these two metrics, the Liberian police reform can be considered a qualified success, as the percentage of female officers rose from 2 to 17 per cent, and the LNP improved its response to SGBV reports. Success factors included the timing, context, local ownership and foreign development assistance. However, the sustainability and overall impact of the reforms was severely hindered by low technical capacity and weak rule of law.

Introduction

Security reform, and police reform specifically, is an integral part of peacebuilding,Footnote1 as is the relationship between ‘women, peace and security'.Footnote2 This article bridges these two bodies of work in addressing issues of gender in police reformFootnote3 through a case study of Liberia's police reforms to recruit more women and respond better to sexual- and gender-based violence (SGBV).

Liberia is an important case for the study of post-conflict policing and security sector reform, and thus the subject of substantial research.Footnote4 In addressing important issues of gender in the process of reform in Liberia, this case study complements and provides new evidence on an important component of that reform.

As the case study illustrates, evaluating and explaining reform processes such as this one is challenging, given the number of factors that influence outcomes. In evaluating outcomes, this analysis focuses on representation and responsiveness, the two key goals of the Liberia National Police (LNP), arguing that in these terms, the Liberian police reform can be considered a qualified success that may offer useful insights for other situations. In explaining this assessment, it highlights the importance of political will, timing, conducive contextFootnote5 and local ownership,Footnote6 as well as of the role of foreign assistance.

Background and Context

Liberia's 14-year civil war ended with a peace agreement in 2003. Of a population of approximately 3 million, an estimated 270,000 Liberians were killed and hundreds of thousands were displaced.Footnote7

The post-war context was fragile. In the Liberian countryside – difficult to reach even during peaceful times – services such as education and health had been on hold for years. In Monrovia, the coastal capital city to which many Liberians fled during the war, residents were traumatized and infrastructure had crumbled. With a GDP per capita of US$135 in 2003, an unemployment rate of 85 per cent and following one of the steepest economic collapses ever recorded in the world, Liberia's economy was flailing.Footnote8 Helping to maintain the tenuous peace was the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL), the largest peacekeeping mission in the United Nations history.Footnote9

Security was UNMIL's and Liberians’ first concern. Although the disarmament and demobilization process mostly quieted the gunfire, a ‘culture of violence’ continued, especially against women and girls.Footnote10 During the war, many Liberians had been sexually or physically assaulted.Footnote11 After the war, sexual- and gender-based violence (SGBV) and armed robbery continued to be the two primary security concerns in Liberia.Footnote12

Citizens had lost trust in the justice system during the war. Liberia's police service had been known as particularly incompetent and brutal. Some police units were known as perpetrators of rape and murder.Footnote13 After the war, the LNP had to build its reputation and gain the confidence of Liberians.

More broadly, Liberia's post-war rule of law needed massive reform. By the end of the war, Liberia had 15 different security agencies with overlapping functions and mandates.Footnote14 The peace agreement called for Liberia's police service to start from scratch. In 2003, the UNMIL Police Commissioner and Liberia National Police (LNP) Inspector General began to implement reforms through a Rule of Law Implementation Committee.Footnote15

In this post-conflict context, could Liberia's new police service prove to be more representative and responsive? Focusing particularly on context, timing, local ownership, project design and foreign assistance, this article explores how – from 2003 to 2013 – Liberia and its partners dealt with these challenges and opportunities.Footnote16 Section three provides background on the local context and aid in Liberia. Section four describes two programmes: one to recruit female police officers; one to train officers in addressing SGBV reports. Because failures in addressing SGBV were attributable to larger justice system bottlenecks, Liberia and the donor community took follow-up steps described in Section five. Section six analyses and discusses what worked well, what did not and offers analysis and explanations for the outcomes. This final section also offers what can be learned from Liberia's experience, as well as what was on Liberia's horizon for gender-sensitive police reform.

The article's finding is that Liberia's gender-sensitive police reform towards better representativeness and responsiveness were innovative, with some positive outcomes. Success factors included timing, context, local ownership and extensive foreign assistance. However, results were mixed: ambitious recruitment efforts brought more female police on board, but the related fast-track programme was neither in-depth nor monitored enough to be effective and had some negative side-effects for women. The specialized unit increased awareness about and response to gender-based violence, but was impeded by a broken judicial system. The technical and financial sustainability of projects’ successes remained questionable, given Liberia's extremely low capacity and weak rule of law.

Gender-Sensitive Reform in a Fragile State Context: Opportunities and Challenges

After the civil war, the Government of Liberia and its international partners had several opportunities to make progress on gender-sensitive police reform. First, women had built credibility as peace agents in Liberia by accelerating the war's end. As acknowledged by the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize committee, thousands of Liberian women joined together during the war in an interfaith peace movement, rallying for a cease-fire and barricading peace talks until negotiators reached an agreement.Footnote17

Second, in 2005, Liberians elected the first female president in Africa. At her inauguration – an event brimming with hopeful Liberians and a supportive international community – President Johnson Sirleaf pledged to support the women in the country. The president followed through with this promise soon after her inauguration by appointing several women to high-level positions in her cabinet and the LNP.

A third window of opportunity for police reform was that Liberia's transition and post-war period was characterized by significant momentum for gender-sensitive reform. Liberian leaders and their international counterparts were mandated to act by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security. Passed in 2000, Resolution 1325 – and follow-up resolutions such as 1820, 1888, 1889 and 1960 – urged countries to increase women's representation in the security sector and to take special measures to prevent SGBV.Footnote18 In 2005, the Liberian legislature passed a ‘rape law’ that expanded the definition of rape and set harsh penalties for sexual assault.Footnote19 The Government of Liberia and UNMIL set a goal to increase the percentage of female police officers from 2 per cent in 2005 to 20 per cent by 2014.Footnote20 The United Nations, itself, set the same 20 per cent female target for itself for its peacekeeping missions.Footnote21

Domestic institutional support for gender-sensitive reform derived from many organizations and planning documents, including Liberia's Ministry of Gender and Development (founded during the war, in 2001, by the national legislature, and became more functional and donor-supported after the war)Footnote22 and the National Plan of Action for the Prevention and Management of Gender Based Violence in Liberia. The National Plan of Action for Gender Based Violence was developed from 2004 to 2006 by the Ministry of Gender and Development in collaboration with the World Health Organization and Liberian ministries and agencies.Footnote23 The national plan established the Gender Based Violence Taskforce, representatives from the police, ministries, donors, NGOs and other stakeholders who met regularly to share data and follow up on cases of gender-based violence.Footnote24

A fourth opportunity to strengthen Liberia's police reform was the presence of vast international support. Leaders around the globe were thrilled at the prospect of a peaceful, better-governed, gender-sensitive Liberia, and threw their support behind President Johnson Sirleaf, a Harvard-educated World Bank economist with a relatively clean record.Footnote25 International aid organizations and donors flooded into Liberia, determined to diminish the suffering and make their mark as the nation began to rebuild.Footnote26

Foremost among Liberia's external supporters after the war was the United Nations. UNMIL was founded in 2003 by United Nations Security Resolution 1509.Footnote27 At that time, it was the largest peacekeeping force in the history of the United Nations, with 15,000 peacekeeping troops and 1,115 police officers from around the world. In the 2003 peace agreement, UNMIL was designated as the lead body in overhauling the police service and developing Liberia's civilian police capacity. The LNP's counterpart at UNMIL was the UN Police (UNPOL), whose role included recruiting police staff, developing training programmes and addressing violence against women and girls as a weapon of war.Footnote28

In addition to UNMIL's massive peacekeeping force and civilian police, other United Nations entities had a major presence in Liberia, all of which engaged and invested deeply in the LNP's gender-sensitive reforms. Examples included United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Peacebuilding Fund, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM, which in 2011 became part of UN Women).

Another window of opportunity was that the LNP was starting anew. The security sector reform process involved deactivating all former police officers and inviting them to apply to join the new service. Starting the police service nearly from scratch meant the opportunity to vet new officers, to weed out those who were unqualified or ill-suited for police service – including those affiliated with rebel groups and those who had committed war crimes – to train recruits, to build a different policing culture and to make a change.Footnote29

However, on the flip side of these opportunities were challenges. For one, as described by Friedman, there was little institutional memory, because officers were deactivated in the security sector overhaul.Footnote30 The post-war state of the police was abysmal and had little infrastructure on which to build. Furthermore, police officers’ capacity to perform their duties was extremely low because the war had deprived them of over a decade of education, training and proper professional experience. Poor infrastructure and low technical capacity would be a constant constraint throughout Liberia's post-conflict police reforms.

Another challenge was that the LNP had a tarnished image after the war. Peace talk participants agreed to dissolve security units that developed reputations for corruption and predation. Such units included the former President Charles Taylor's notorious Anti-Terrorist Unit, known for committing murder, torture and rape.Footnote31 But the police's violent reputation would not disappear immediately. In addition, the LNP did a poor job handling cases of SGBV, such as domestic abuse, child abuse and sexual assault. The head of the SGBV Unit of Liberia's Ministry of Gender and Development recalled that, before and during the war: ‘The police didn't know how to handle SGBV. … If a woman reported rape, the police would suggest she had caused it. They would make it worse, and women would be traumatized.’Footnote32

A third challenge for enhancing responsiveness was the pattern of low reporting rates for rape. Stigmatization and taboos associated with rape in Liberia worsened the problem of underreporting that commonly characterized such crimes.Footnote33 In a study commissioned by the United Nations in 2008, only 12.5 per cent of Liberian women who had been raped said they had reported their cases to the police.Footnote34 Another underreporting factor was that an extraordinarily high rate of sexual assaults were committed against children. A 2006 report by Doctors without Borders indicated that 85 per cent of 658 rape victims treated at its clinic were younger than 18; 48 per cent were under 12.Footnote35 Most sexual assault cases were settled outside of court, either privately or through traditional or customary structures.Footnote36

A fourth challenge both for recruiting women and for responding to SGBV was Liberia's culture and history: the security services had been predominantly male throughout Liberia's history, a pattern common to security services throughout the world. This would make it more difficult to recruit women to the police service. Furthermore, Liberia's history of male domination and violence against women meant that the country's ‘rape epidemic’ and ‘culture of violence’ would be extremely difficult to combat.

Finally, the donor presence in post-war Liberia provided resources and support, but also posed hazards. There was the danger – especially in a post-war context – that aid organizations could prioritize pet projects, proceed without a full understanding of the Liberian context or create reforms unsustainable in donors’ absence. Of particular concern, outsiders’ solutions could fail to consider Liberia's pre-existing customary, traditional and informal structures.Footnote37 Furthermore, donor projects would need to ensure that investments were not concentrated solely in the capital. The majority of Liberians lived in villages that were difficult to reach, especially during the rainy season, and were hours or days away from donor projects and development in Monrovia.Footnote38

Initiatives to Improve Representation and Responsiveness

After Liberia's civil war ended, the LNP – alongside UNMIL, and with support from other aid organizations – engaged in two major gender-sensitive initiatives.Footnote39 The first was to improve women's representation in the LNP, with the goal of reaching a 20 per cent female police service by 2014. The second was to enhance responsiveness to SGBV.

The LNP's dual goals of representation and responsiveness were related. Poor responsiveness to SGBV was explicitly linked to a shortage of women in the security sector.Footnote40 Few women in police ranks meant few women to respond to and conduct the kind of sensitive investigations required for gender-based crimes, whose victims often preferred to speak with female officers.Footnote41 However, recruiting more female officers was also driven by beliefs that Liberia's leaders and public sector should be more representative of its citizens and that women would make important contributions to a security sector from which they had been discouraged previously.

In 2006, President Johnson Sirleaf appointed Beatrice Munah Sieh as Liberia's first female inspector general, the top position in the LNP, and in 2007, she appointed Asatu Bah-Kenneth as the LNP's deputy inspector general.Footnote42 Beginning in 2006, the LNP's leaders, as well as the LNP's gender, personnel and community services units, worked to recruit new officers and showcase the growing numbers and prominence of women in the police service.

By early 2007, the percentage of women in the LNP had more than doubled from 2 per cent to 5 per cent, but the 20 per cent goal remained distant. The key hurdle was that many women did not have the required high-school education.Footnote43 In 2007, because of the years of war and because parts of the country did not encourage girls’ education, only 5 per cent of women had completed high-school.Footnote44

In response to this obstacle, an Education Support Programme (ESP) was created to enable women between the ages of 18 and 35 who had completed at least ninth grade to earn the equivalent of a high-school degree and enter police training. The impetus for the ESP was a combined effort of UNMIL and UNPOL.Footnote45 In the first step of the ESP, the West African Examination Council (WAEC) determined female applicants’ education level and assessed their ability to learn the required material. In the first cohort, fewer than half of the 350 applicants were accepted into the programme.Footnote46 Through the next three months, the accepted female police aspirants underwent intense schooling six full days per week. The programme provided lunches and transportation and housing stipends. Instructors, mostly Liberians and other West Africans, taught classes in 11 subjects and administered progress exams every month.Footnote47 After three months, the institute conducted final exams followed by official exams administered by WAEC. Successful candidates then followed the standard procedures to enter basic police training at the academy.

The ESP had three sessions – one pilot cohort in 2007, a second cohort in late 2007 and a third cohort in 2008 – and significantly improved the LNP's gender balance. As a result of the three cohorts in the programme between 2007 and 2008, approximately 300 women joined LNP training classes, increasing female enrolment from 5 per cent to 12 per cent.Footnote48

Recruitment efforts continued, led by UN Women, Liberia's Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Gender and Development, UNMIL and the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET).Footnote49 By 2013, 767 of the LNP's 4,417 officers were women (17.4 per cent).Footnote50

***

Beyond recruitment for more balanced representation, the LNP worked to improve its responsiveness, particularly to sexual- and gender-based violence. In 2005, the LNP created a special unit, the Women and Children's Protection Section (WACPS), dedicated to responding to reports of domestic violence, sexual assault and crimes against children. UNMIL and UNICEF supported the creation of this section, and UNPOL were assigned to WACPS as colleagues and trainers. WACPS units throughout the country were funded through a grant from the Norwegian government, administered through UNDP.Footnote51

WACPS's mission was modelled after an innovative unit in neighbouring Sierra Leone. With the support of the UN Mission in Sierra Leone, Kadi Fakondo – a high-ranking police officer from Sierra Leone – had established Family Support Units in 2001 to encourage survivors of rape, domestic violence or sexual crimes to report the crimes to the police.Footnote52 Sponsored by UNICEF, Fakondo and another officer came from Sierra Leone to Liberia in 2005 to train the first two batches of LNP WACPS officers and to train trainers for future sessions. Each batch of Liberian trainees consisted of 25 male and female LNP officers, some of whom were new to the police, and some of whom were LNP veterans who had to repeat basic training due to the deactivation process. Training included instruction in topics such as creating case reports for crimes of domestic violence and sexual assault, investigating reports, collecting evidence and maintaining confidentiality.

WACPS began operations in September 2005, staffed by the first 25 trainees. Asatu Bah-Kenneth, who had been in the police service for two decades, attended the first WACPS training and was named to head the section in 2005. (She was later appointed as the LNP's deputy inspector general.) WACPS's organizational structure included a director, deputy director, chief of administration, chief of operations, chief investigator, three crime squad heads, as well as several investigators, officers and support staff. Two of WACPS's three squads – the Sexual Assault Unit and Juvenile Unit – had been independent LNP operations previously, while the third, Domestic Violence, was new.

Accurate record-keeping was crucial – collecting victims’ statements, co-ordinating investigations and following up – and WACPS and UNPOL continued to hone the section's information management and investigation processes. On a monthly basis, WACPS compiled data from all of its units into a report, which it then sent to members of the Gender Based Violence Taskforce.

To spread awareness about WACPS to the Liberian people, UNICEF, UNMIL, the WACPS team and other supporters designed awareness campaigns, including leaflets, posters, school visits, community meetings, billboards and radio shows. Officers engaged with journalists on a regular basis to make sure their services were publicized. In its early months, the section also engaged in advocacy events such as marches and radio features to support the 2005 passage of Liberia's broadened and toughened law on rape. The section engaged in community outreach with other police units. For instance, the Community Policing Unit organized weekly community-discussion trips that included representatives from the Gender Unit, the Personnel Unit and the Traffic Patrol Unit. WACPS officers joined these outreach sessions, explaining how to report crimes and preserve evidence.

The Norwegian Refugee Council's gender-based violence programme worked with the LNP and others to devise a ‘Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Referral Pathway'. The pathway – which was depicted on brochures, posters and LNP presentations – publicized proper reporting channels so that victims, police, hospitals, counsellors and courts understood victims’ rights and reporting options. In clear language, it emphasized that survivors should never pay bribes or fees for reporting.

Changing cultural norms was an important responsibility of WACPS. Many Liberians did not realize that rape was a reportable crime and did not know how to preserve evidence or where to go for help. With support from UNMIL, WACPS and its counterparts posted billboards around Monrovia with messages like ‘Rape is a crime’ and ‘Against my will is against the law', and co-ordinated a ‘Stop Rape’ campaign that culminated in an event at the sports stadium, with songs, skits and speeches by Liberian leaders and public figures. Through such campaigns, the Liberian public became increasingly aware of laws against rape and where to seek help.

In May 2011, the new WACPS headquarters in Monrovia was completed and dedicated with a launch ceremony. By June 2013, over 300 officers had received WACPS training. At any given time, approximately 180 active WACPS officers – approximately one-third of whom were women – were stationed in 52 police stations spread across all of Liberia's 15 counties.Footnote53

Addressing Broader Justice System Constraints to Responsiveness: Follow-up Projects

During its reforms to enhance responsiveness to SGBV, the LNP and its partners encountered judicial hurdles. As more Liberians learned that they could report rape to the police, WACPS's caseload and the number of cases it sent to the courts grew. By 2009, a backlog of more than 100 cases had developed.

Although the backlog partly reflected the difficulties of investigating new allegations of crimes that had taken place years earlier, it was also a by-product of a slow-moving justice system. Police officers did not always co-ordinate well with prosecutors, and officers did not always have the technical capacity to follow proper procedures. Sometimes investigations did not collect enough evidence to support the case in court. As a result of insufficient evidence as well as low capacity, court proceedings moved at a glacial pace – when courts heard these cases at all. These challenges so deeply compromised WACPS's mission that donors and the Government of Liberia decided to act.

In February 2009, leaders at Liberia's Ministry of Justice took two steps, both of which were designed to address the LNP's obstacles in responding to gender-based violence. First, the ministry – with support from UNFPA and funded by the Government of Denmark – established Criminal Court E (known as a ‘Special Court’ or the ‘rape court’), a fast-track mechanism intended to overcome Liberia's backlog of cases involving SGBV.Footnote54 The court used in camera hearings, in which a private witness room enabled the victim and any witnesses to testify and receive questions without having to face the accused perpetrator.Footnote55

Second, the justice ministry created the SGBV Crimes Unit in April 2009.Footnote56 The mission of the unit – intended as a pilot project – was to counsel victims, improve police officers’ ability to run investigations, co-ordinate police officers and prosecutors, train prosecutors to tackle cases involving sexual violence and build public awareness. The SGBV Crimes Unit was set apart from both the Ministry of Justice and police headquarters for confidentiality reasons.

When Criminal Court E was created, there was a great deal of optimism and hope that the backlog of sexual violence cases would finally be resolved. For instance, UNMIL Independent Human Rights Expert Charlotte Abaka told reporters in 2008 that she was ‘encouraged’ by the creation of the new court dedicated to sexual assault, saying, ‘The undue delay in prosecuting such cases will now be a thing of the past.’Footnote57 Unfortunately, by 2013, almost everyone was discouraged as the backlogs and delays continued.

Analysis and Discussion

From 2003 to 2013, to mixed results, Liberians and their development partners recruited female officers to improve representation, and created and scaled-up a specialized police unit to address SGBV to improve responsiveness. This section first provides an evaluation of the two LNP projects. It next evaluates the two follow-up Ministry of Justice projects: Criminal Court E and the SGBV Unit. It then offers a broad analysis and discussion of which elements of Liberia's gender-sensitive police reforms were the strongest and weakest, and why.

Assessments of the LNP's ESP and WACPS Reforms

As a means of accelerating female officer recruitment, the ESP received mixed reviews. Champions believed it provided an accelerated professional gateway for women who were not able to complete high-school. On the whole, it was an innovative programme tackling a specific context-relevant problem, and fast-tracked a record number of women into the LNP.

However, some elements of the recruitment reforms were not as effective. Women were poorly represented in the LNP's specialized and elite forces such as the Police Support Unit (PSU) and Emergency Response Unit (ERU). For instance, of the 523 operations PSU officers in July of 2011, only 31 (6 per cent) were women.Footnote58 Of 324 ERU officers in 2011, only 19 (6 per cent) were women.Footnote59 Furthermore, while the number of female police officers was rising, there were few female police officers deployed outside Monrovia. For instance in 2011, of the 71 female Women and Children Protection Section officers deployed around the country in 2011, only five (7 per cent) were in rural counties.Footnote60

Nielsen, UNMIL's commissioner of police, said that the programme created a caste system and did a disservice to trainees:Footnote61 ‘The real problem is, we condemned those young women to a career as a patrolman, because they can't read and write. … How can they compete? They can't.’Footnote62 Other observers were concerned that the female graduates of the ESP could become a liability to the LNP if not further trained and mentored, or that they might have extremely high rates of attrition going forward.Footnote63

A former police officer and top official at the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization offered her assessment that the programme had been created in a desperate effort to reach the goal of 20 per cent women in the police service: ‘They were looking for numbers and not quality … and so they didn't find the best.’Footnote64 She noted that some men resented a fast-track education programme for women because men, too, had missed out on education during the war.Footnote65 Finally, she questioned the decision to seek new female recruits rather than tap into the LNP's pool of experienced women who had left the police in the deactivation process.Footnote66

UNMIL's Sylvia Bisanz, who helped coordinate the programme, said: ‘I believe that overall the programme was successful. However, prolonging it a little might be beneficial.’Footnote67

Outsiders’ assessments of police responsiveness to SGBV were also mixed. First, it is important to note that assessing WACPS's precise impact on rates of gender-based violence would be impossible. Because few victims report rape – not just in Liberia, but in most contexts – real rates of sexual assault will never be known.Footnote68 Furthermore, in a point discussed later in this article, most criminal cases in Liberia do not make their way through the formal system. Isser et al. estimate that 50 per cent of rape cases were never reported, 28 per cent were taken to an informal forum (e.g. family heads, traditional leaders, elders, secret society members, soothsayers, midwifes, chiefs) and 21 per cent were taken to a formal forum (e.g. police officers, magistrates, government officials).Footnote69 So the total amount of WACPS reports of gender-based violence would never reflect actual SGBV crime rates.

That said, after WACPS was founded, the number of Liberians reporting SGBV to the police rose – including the reporting of assaults that had happened years earlier.Footnote70 Many observers and internal actors believed that higher rates of reporting indicated enhanced trust in the LNP, rather than higher incidence of crime.Footnote71

Indeed, many observers praised WACPS. In a context of a supportive president and eager external community, WACPS enhanced awareness about and response to gender-based violence. In particular, WACPS emphasized that rape is a reportable crime. UNMIL's monthly reports heralded WACPS, as did the donors (especially the Norwegian government). The deputy director of training at the National Police Training Academy said that people never used to report sexual assault or domestic violence to the police, but now ‘if there is a problem, people go to the WACPS first’.Footnote72 A United States Embassy officer said that the WACPS was ‘highly regarded'.Footnote73 The Liberian community was more aware than ever about the illegality of and ability to report sexual crimes because of ubiquitous billboards, media announcements, community events, posters and other forms of publicity. Officials at the Ministry of Gender and Development, as well as taxi drivers and other non-government officials, noted that many Liberian women would respond to harassment by threatening to make a report to WACPS.

However, WACPS faced serious challenges. First, as in most Liberian institutions, WACPS needed further capacity building and training. Some officers lacked the skills needed to write reports, investigate crimes effectively and follow up.Footnote74

Second, like the rest of the LNP, WACPS also faced resource limitations. Most section officers did not have vehicles. Lack of transportation jeopardized confidentiality; for example, a former WACPS section head mentioned that she had often paid for private taxis for victims so that they would not have to travel from WACPS headquarters to the hospital in a shared taxi (as shared taxis are customary in Liberia).Footnote75 Furthermore, transportation difficulties compromised the integrity and feasibility of the investigation. The deployment of WACPS officers in 52 units across the country meant communities were closer to formal institutions than in the past, but some Liberians still had to walk hours to reach the nearest section office, and officers had to make the same trek to investigate the crime. Additionally, WACPS lacked communication resources, such as cellphones and computers. Most officers outside of Monrovia reported cases to headquarters through hard copy, via UNMIL vehicles passing through or by calling or sending text messages.

Third, officer attrition was another issue, because there were few incentives. WACPS officers did not receive an extra bonus for their specialized training, whereas members of other specialized units enjoyed higher salaries and greater access to per diem payments.Footnote76 Not surprisingly, some of the best WACPS officers transferred to other units. Interestingly, some critics complained that WACPS had more resources than other units at the police, because donors tended to prioritize WACPS. For instance, in some rural counties, WACPS had a motorcycle or car or better facilities than other units within the LNP. Sometimes, estimations of WACPS resources were inflated: the head of WACPS's Juvenile Unit noted that other officers had an inaccurate perception of WACPS's resources: ‘Other police officers feel we have been sponsored by donors and think that we have extra wages for the work we do. They think there is a special fund for WACPS investigators. Then they go to WACPS training and realize there isn't.’Footnote77

WACPS was a unique effort to address an important and intractable problem, but it was limited by extremely low capacity, in terms of both resources and technical ability to perform necessary duties. The critical setback was that WACPS was impeded by a broken judicial system (see later sections on ‘Evaluation of Criminal Court E and SGBV Crimes Unit' and ‘Overall Discussion and Analysis'). Vildana Sedo, acting UNPOL gender adviser and UNPOL officer at WACPS noted: ‘LNP has made huge progress. The problem is that the criminal judicial system is unable to support what LNP achieves.’Footnote78 The acting UNPOL gender adviser summed up LNP's progress on responding to SGBV: ‘They're doing a good job given the challenging circumstances and resources they have.’Footnote79 The UN Secretary-General's assessment of WACPS in 2012 was as follows: ‘While intensive in-service training has improved the handling of cases involving SGBV and their referral by the police to the courts, the criminal justice system continues to face enormous challenges in dealing with such cases.’Footnote80

Overall, the situation was still bleak, with Liberia's ‘rape epidemic’ persisting a decade after the war ended. In 2013, armed robbery and rape were still Liberia's two most commonly reported crimes.Footnote81 Of the victims of sexual assault, 70 per cent were minors and nearly 18 per cent were under 10 years old.Footnote82

Evaluation of Criminal Court E and SGBV Crimes Unit

Although the joint initiatives of the Criminal Court E and the SGBV Crimes Unit were promising steps, a shockingly small number of cases made it from the LNP to and through court.

The SGBV Unit had a backlog of more than 100 cases when it was established. The leader of one donor project said: ‘It's almost like the Crimes Unit was set up to fail, which I think is just really unfair, because potentially it could be amazing. It could be a really great resource for Liberia.’Footnote83

From its founding in February 2009 through July 2011, the SGBV Crimes Unit was able to shepherd only 16 of approximately 200 cases through Criminal Court E, eight of which ended in convictions ranging from seven years to life imprisonment.Footnote84 By 2013, the court had tried 34 rape cases: 18 defendants were found guilty, 15 were found not guilty and one verdict was not resolved due to a hung jury; 280 cases were dropped because of lack of sufficient evidence.Footnote85 Meanwhile, over 100 people accused of rape sat in prison waiting for trial and accusers waited for their day in court.Footnote86

Felicia Coleman, head of the SGBV Unit, explained that there were many difficulties and challenges in managing rape cases. She lamented that complaints often came to the police or the unit long after the evidence had been destroyed, rendering investigation and conviction more difficult. In rare instances when complaints were reported immediately, Liberia had no forensic laboratory to analyse the evidence. Finding witnesses was impossible in most cases.

One clear bottleneck was that only one judge was active at Criminal Court E, although the law technically provided for two judges. An independent evaluation of the SGBV Crimes Unit recommended that ‘a second judge should be added to the one sitting judge … because the time spent on one case by the long-present judge makes the trial process too slow and thus handles few cases only.’Footnote87

Other bottlenecks in moving cases through the judicial system included lawyers, the jury and the note-taking process. First, according to an independent analysis, defence lawyers tended to file ‘unnecessary and delay-tactic motions', which the Liberian system required be adjudicated before continuing the trial.Footnote88 Second, the analysis recommended that the Liberian government should empanel another grand jury for sexual offences and other related cases in order to help a greater number of cases move from grand jury level to trial stage.Footnote89 Furthermore, the analysis reported that, ‘the Special Court typist is not a trained stenographer. The current arrangement is so slow that it distorts the flow of evidence as the witnesses testify. Persistently, the court would have to wait for the machine to catch up with the proceedings.’Footnote90

The overarching problem, Coleman said, was that a single court or crimes unit could not solve Liberia's broad and deep justice system problems. ‘The entire criminal justice system needs to be reformed', she asserted. ‘The jury system needs to be overhauled. … The challenges are enormous and run across the entire system: the jury, the court, old laws, witnesses, the communities.’Footnote91

Overall Discussion and Analysis

The following section takes a step back to consider the broader contextual issues that impacted recruitment and responsiveness – including timing, local context, foreign aid, sustainability, project design and rule of law.

An overall framing for successes and failures of these projects could find support in Andrews et al.’s concept of ‘problem-driven iterative adaptation’ – a pragmatic synthesis of development reform results describing interventions which:

(i) aim to solve particular problems in local contexts, (ii) through the creation of an ‘authorizing environment’ for decision-making that allows ‘positive deviation’ and experimentation, (iii) involving active, ongoing and experiential learning and the iterative feedback of lessons into new solutions, doing so by (iv) engaging broad sets of agents to ensure that reforms are viable, legitimate, and relevant.Footnote92

In part, the extent to which the programmes (ESP, WACPS, Special Court E, SGBV Crime Unit) were driven by problems rather than imposed solutions, took into account the local context, allowed for experiential learning and engaged a broad set of agents determined the extent to which the programmes were effective and sustainable.

Timing, context and foreign aid: In some respects, the timing and context of Liberia's gender-sensitive police reforms was ideal. There is no question that Liberia was in a desperate situation and in need of foreign aid after its 14-year conflict. Most structures were shattered; services like electricity, water, education, health and security were non-existent; residents were displaced and traumatized; crime rates were high; ex-combatants were still armed; and there was no formal rule of law. External support – security, financial, technical and human capital – was welcomed by Liberians. Crowds cheered when the UN tanks rolled in, and those tanks remained in Monrovia for years after the war ended.Footnote93 The local context, then, was ripe for development support.

As mentioned earlier, donors took advantage of a post-conflict window of opportunity that included strong momentum for changing norms while starting from scratch. With a women-led peace movement that helped stop the war, a newly elected female president, a female inspector general of police, gender-sensitive donor nations and a UN mission with a mandate to incorporate gender mainstreaming in security sector reform, there was a great deal of energy behind the recruitment and responsiveness initiatives. In this new era, donors and their Liberian partners had leeway to recruit female police ambitiously and create a new unit to respond to gender-based violence.

However, analysis indicates that the timing of these projects was not always successful. With representation, the attempt to fast-track education and recruitment should have been more thorough in its training and accompanied by robust follow-up measures. WACPS was not as effective as it could have been because Liberia's entire justice system was weak. Had more resources and capacity building efforts been concentrated earlier on holistic improvements of Liberia's rule of law, it is possible that fewer WACPS cases would have been backlogged in the court system. Indeed, because WACPS cases were backlogged in courts, it is possible citizens may have lost faith in the unit over time and instead sought alternative mechanisms (e.g. settling outside of the formal system).

Sustainability and capacity: Sustainability and capacity issues arose in the gender-sensitive police projects supported by bilateral donors, international NGOs and UN partners.

Donors tried to build sustainability and Liberians strived to assume ownership of projects. For instance, Dave Beer, chief superintendent at the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who worked for the UN in Liberia, lauded Liberia's efforts to recruit more women to the police, noting that the reforms were locally led. ‘This was done by the government, not by the international community', Beer said. ‘[Efforts] displayed not only a lot of creativity and a desire to have much more gender balance, but it was a real indicator of political will to make some substantive change.Footnote94 Liberia Representative Regina Sokan-Teah said: ‘They [UNMIL] want us to take ownership of the security sector instead of leaving it in the hands of strangers.'Footnote95

However, the jury was still out as to whether achievements could persist. The Liberians’ lack of technical, financial and physical capacity to perform roles would continue to hinder progress on security. Through Security Council Resolution 2066 (2012), which extended UNMIL's mission through 30 September 2013, the UN reiterated its calls on the Government of Liberia to

continue to combat SGBV and, in co-ordination with UNMIL, to continue to combat impunity for perpetrators of such crimes and to provide redress, support, and protection to victims, including through the strengthening of national police capacity in this area and by raising awareness of existing national legislation on sexual violence. (Emphasis added by author)Footnote96

In 2013, the UN Secretary-General described the security situation as ‘stable but fragile’ and confirmed that ‘addressing issues such as the quality of training, professional standards, accountability, public trust, and sustainability is central to the ability of the police to perform their duties’.Footnote97

Unique project design elements: Unique and innovative elements include the prioritization of cultural/norm change, an emphasis on awareness-raising educational campaigns, study trips, role modelling and side-by-side embedding.

Donors and the Liberian police invested not only in recruitment and responsiveness projects but also awareness-raising initiatives, whose impact should not be underestimated. For instance, UNMIL radio often featured information and shows on gender-related topics, Monrovia's billboards were plastered with messages and images about reporting rape, Liberia's international partners helped the country prepare for holidays (which tended to have higher rates of gender-based violence) and donors sponsored massive campaigns both on women's participation in security sector reform and on rape prevention. For such activities, outcomes and metrics of success are hard to track – especially in the short term – but likely contributed to norm changes in Liberia.

In terms of unique design elements that other countries could model after the Liberian experience, international actors might try to expose government officials to a wealth of experiences through study trips, role modelling and side-by-side embedding. Liberian government officials went on sponsored trips and came back with new ideas. Napoleon Abdulai, security sector reform adviser at the UNDP, said: ‘In Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Mali, you have many more women in higher positions in the security sector who make decisions. They're not leaders in a ceremonial sense. They control budgets’.Footnote98 Study trips were important because they helped instil the gender-sensitive ideas that outsiders had been pushing within Liberia to some resistance. Abdulai noted: ‘People thought that it was because of the president and international community that we were pushing these things. But when you go out, you see what gender experts were saying. Then you see it in reality.’Footnote99 Of note, Liberian officials did not perceive the extent of male domination in Liberian institutions until they travelled and returned as ‘apostles for gender mainstreaming’.Footnote100 For instance, Liberia's House of Representatives national security committee chairman came back from a trip to Ghana fired up to make changes. ‘They went to Ghana to the police headquarters', Abdulai said, ‘and realized that what gender experts were saying in Liberia was actually being implemented there’.Footnote101

Role modelling was another successful component incorporated into the design of Liberia's reforms. It was critical that the president had appointed women to high-level positions at the LNP, and that those women were in the spotlight. Nielsen stressed the importance of female role models:

I'm a believer in this; I became a convert in this. The first IG [inspector general of the police] was a woman. And it was a good thing. Children learn what they see. So having an IG in the hallways – a woman, and she made a point of having senior women around her – changed the perspective of the men at the top of the LNP, especially the young officers coming up. So you were building respect.Footnote102

The presence of an all-female Indian Formed Police Unit also helped reinforce the image of women leading security efforts.

Another element of the mutual learning design included the embedding of outside experts with local police. UNPOL worked side by side with LNP leaders, enabling hourly feedback, training and mentorship. For instance, six UNPOL officers were assigned to WACPS. Not only did this regular contact help Liberian police institutionalize new practices and build their technical capacity through on-the-job training and learning, but this arrangement also helped UNPOL better understand the Liberian context and challenges. Nielsen of UNMIL said: ‘This mission [UNMIL] has 39 different nations contributing police officers and, therefore, [39] professional perspectives on policing.’Footnote103 Such a diversity of opinions could potentially confuse or dilute the development efforts (and sometimes did, in Liberia's case), but the variety of counterparts also let Liberians learn from a broad array of experiences and cultures.

Geography was one design element that did not work as well. Donors’ efforts in Monrovia did little for Liberians in rural counties. Projects often did not heed the common refrain – ‘Monrovia is not Liberia’ – and rather focused primarily in the capital. To be effective going forward, donors and the government would need to adopt similar approaches and broaden their reach.

Security, justice, and rule of law issues: Liberia's rule of law hindered LNP reforms from 2003 to 2013. The result was clear, explained by the UN Secretary-General's 2013 report on UNMIL: ‘Effective investigation and prosecution of SGBV cases remain problematic, and out-of-court settlements are prevalent.’Footnote104

Blume places the blame on several factors: ‘principally a lack of Liberian capacity; mutual accusations of incompetence between UNMIL and Liberian lawyers; resistance of the Liberian judiciary to engage in reforms; and UNMIL's state-centred approach to legal reforms. Many of these issues were exacerbated by personality clashes between individuals in UNMIL and the Liberian judiciary.’Footnote105

Diagnoses for the problem range widely, but a few primary themes emerge.

First, all actors would need to invest more in prevention, while still addressing investigation and prosecution issues. The UN Secretary-General's 2013 report on UNMIL stated:

Notwithstanding important progress made in strengthening response mechanisms and the reporting of crimes of sexual and gender-based violence, the prosecution of these cases remains a challenge, owing to weak institutional capacity and the high cost, both financially and socially, of the victims and their families. Efforts for prevention require much greater attention, both from the Government and international partners.Footnote106

Second, some donors privileged SGBV projects over prevention and broader justice reforms, which analysis found problematic. Schia and de Carvalho report that the international response to crime in Liberia was fragmented and ineffective, focusing on symptoms rather than causes. One of the anonymous interviewees in their paper said: ‘Everyone looks at GBV at the expense of a holistic picture of the criminal justice system. The problem is the legal system as a whole.’ Another interviewee lamented: ‘Why can't victims of rape get justice? It's not because they're women; not because they're victims of rape; it's because nobody gets justice here!’Footnote107

Third and relatedly, reformers did not pay adequate attention to customary and traditional justice systems. One criticism is that donors took the ‘start from scratch’ element too far. Schia and de Carvalho write: ‘What we witness in Liberia is to a large extent what Sarah Cliffe and Nick Manning have termed “the fallacy of terra nullius” – the inability of the UN to take into account pre-existing institutions and the assumption that everything must “start from zero”.’Footnote108 Specifically, UNMIL, the Norwegian government and other donors did not pay appropriate attention to the role of traditional/customary justice in Liberia.Footnote109 In a 2009 study of Liberia's dual justice system, the United States Institute of Peace found that only 2 per cent of criminal cases reached formal courts, 45 per cent went to traditional/customary courts and the rest never made it to any system.Footnote110

Given the importance of the informal justice system in Liberia, Schia, de Carvalho, Isser, Maturu and others believe it is essential that international actors explore Liberia's dual system of customary and statutory law to see how they might work together and complement one another, but that outside supporters have focused almost exclusively on statutory law.Footnote111 Furthermore, there was a ‘propensity to apply readymade, generic solutions that resonate well with Western donors’.Footnote112

Schia and de Carvalho articulate this point by tying LNP reforms to broader issues:

The problems surrounding the WACPS are in many ways symptomatic of the way in which post-conflict reconstruction is managed by international donors and the UN in general – namely that there is lack of coherence, no comprehensive and deep understanding of how the issues relate to each other, and an undue channelling of resources into projects that fit with the donors’ perspective rather than the needs of the community. SGBV and the protection of women and children is no doubt an important task; it also fits within the Scandinavian priorities, and therefore is an attractive way to spend aid money.Footnote113

Maturu explains why the traditional systems often worked better for Liberians and why efforts to respond to gender-based violence have not trickled down to rural crimes:

Most magistrate courts and police stations are located in large urban centers; most Liberians are not. The average walking time to police stations and courts is 3.5 hours and can go up to 10–12 hours. In comparison, customary institutions exist in all communities at all levels, and are also much more cost effective. Many formal judicial proceedings will not go forward unless ‘fees’ are paid to keep cases from being neglected. The overall costs for the customary justice system are significantly lower, more consistent, and transparent, and sometimes even free.Footnote114

According to Isser et al., Liberians are extremely dissatisfied with the formal justice system, especially at the local level: ‘[E]ven if the formal justice system were able to deliver affordable, timely, and impartial results, it would still not be the forum of choice for many rural Liberians.’Footnote115 In fact, it could be that some of the reforms to strengthen the formal system – such as the ban on handling matters of serious crimes in customary courts – might have made things worse: ‘State policies aimed at regulating and limiting the customary justice system in order to comply with human rights and international standards are having unintended adverse consequences.’Footnote116 For instance, many Liberians interviewed for the Isser et al. study believed that – because chiefs complied with the ban and because formal courts could not yet fulfil their mission – this ban led to less justice rather than more.Footnote117

On one hand, donors not taking traditional and informal systems of law more fully into account could appear at best to fall into the trap of not understanding local context, and at worst prove counterproductive and a product of cultural imperialism. However, it could be argued that Liberia's male-dominated security sector and its rape epidemic were rooted in some elements of Liberia's traditional culture and that a robust and institutionalized rule of law would be necessary to change norms and achieve justice. Thus, efforts to recruit women actively, move criminal cases to the formal system and earn citizens’ trust in the formal justice system were well placed. However, they certainly needed thoughtful and accompanying reforms at the local levels.

Looking Forward

As for the LNP, lack of resources, capacity issues and gender imbalances continued to be major constraints in Liberia, as in many other post-conflict countries. However, Liberia planned to adapt new approaches to address some of the challenges discussed in this article and also to prepare for the transition of security responsibilities from UNMIL to the Government of Liberia.

In 2014, the spread of Ebola to thousands of Liberians threatened a great deal of post-war progress that the country had made on many fronts: security, economic, political and so on. By 2015, Liberia had nearly eradicated Ebola, but the setbacks were substantial.

On a more positive note, Nielsen provided a vivid picture of the extent to which community perceptions of the LNP had changed since the end of the war: ‘As our inspector general likes to say, “I want our children to run to the policeman, not away from them.” And they do.’Footnote118

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Bacon is Principal, Policy for the Governance and Citizen Engagement Initiative at Omidyar Network, a philanthropic investing firm. She is based in London, UK. Previously, she was the Associate Director of Innovations for Successful Society, Princeton University, a research programme at which she conducted the bulk of this Liberia research. She has served as a White House Fellow (2009–10), an adviser to Liberia's Women's Legislative Caucus (2009) and Liberia's Ministry of Gender and Development (2008), a research fellow at Harvard's Center for Public Leadership (2005–07) and a Peace Corps Volunteer in Niger (2002–05). She has a master's degree in Public Policy from Harvard Kennedy School and a bachelor's degree from Harvard College.

Notes

1. S. Dinnen and G. Peake, ‘More Than Just Policing: Police Reform in Post-Conflict Bougainville’, International Peacekeeping, Vol.20, No.5, 2013, pp.570–84; B.K. Greener, ‘Statebuilding, Peacebuilding, Police and Policing in Solomon Islands’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, Vol.6, No.2, 2011, pp.30–42; O. Marenin, ‘Styles of Policing and Economic Development in African States’, Public Administration and Development, Vol.34, No.3, 2014, pp.149–61.

2. K. Erzurum and B. Eren, ‘Women in Peacebuilding: A Criticism of Gendered Solutions in Postconflict Situations’, Journal of Applied Security Research, Vol.9, No.2, 2014, pp.236–56; OECD, Gender and Statebuilding in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States, Paris: OECD, 2013; T.L. Tryggestad, ‘The UN Peacebuilding Commission and Gender: A Case of Norm Reinforcement’, International Peacekeeping, Vol.17, No.2, 2010, pp.159–71.

3. See R. Kunz, ‘Gender and Security Sector Reform: Gendering Differently?’, International Peacekeeping, Vol.21, No.5, 2014, pp.604–22.

4. B. Baker, ‘Resource Constraint and Policy in Liberia's Post-Conflict Policing’, Police Practice and Research, Vol.11, No.3, 2009, pp.184–96; M. Bøås and K. Stig, ‘Security Sector Reform in Liberia: An Uneven Partnership without Local Ownership’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Vol.4, No.3, 2010, pp.285–303; Marenin (see n.1 above); S. Podder, ‘Bridging the “Conceptual–Contextual” Divide: Security Sector Reform in Liberia and UNMIL Transition’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Vol.7, No.3, 2013, pp.353–80; K.B. Robinson and C. Valters, Progress in Small Steps: Security against the Odds in Liberia, London: Overseas Development Institute, 2015; U.C. Schroeder, F. Chappuis and D. Kocak, ‘Security Sector Reform from a Policy Transfer Perspective: A Comparative Study of International Interventions in the Palestinian Territories, Liberia and Timor-Leste’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Vol.7, No.3, 2013, pp.381–401.

5. Marenin (see n.1 above).

6. E. Gordon, ‘Security Sector Reform, Statebuilding and Local Ownership: Securing the State or Its People?’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Vol.8, No.2–3, 2014, pp.126–48.

7. Republic of Liberia, ‘Poverty Reduction Strategy', 2008 (at: emansion.gov.lr/doc/Final%20PRS.pdf), p.14.

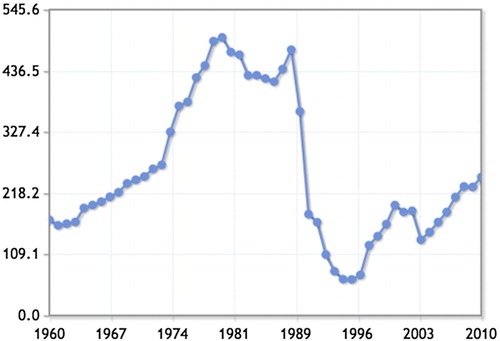

8. Index Mundi, ‘Liberia – GDP Per Capita (Current US$)', 2013 (at: www.indexmundi.com/facts/liberia/gdp-per-capita); CIA Factbook, ‘Liberia', 2013 (at: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/li.html); Republic of Liberia (see n.7 above), p. 15. The economic drop refers specifically to the 1987 to 1995 period, in which Liberia's gross domestic product dropped 90 per cent. See Appendix A for a graph of Liberia's GDP drop.

9. See Appendices B and C for information on UNMIL's Liberia presence and funding from 2005 to 2013.

10. Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘Women's Rights through Sensitization and Education (WISE)', 2011. Document given to author by project manager (at: www.nrc.no/arch/_img/9474672.pdf); C. Shiner, ‘Liberia: New Study Spotlights Sexual Violence', AllAfrica.com, 2007 (at: allafrica.com/stories/200712051066.html).

11. Studies on assault against women during the war report a wide range of percentages (from 12 per cent to 92 per cent), depending on how the research questions were worded, in what county the respondents lived and whether the violence included domestic violence. In this article, data on sexual assault were derived from multiple sources, including: (1) P. Vinck, P. Pham and T. Kreutzer, ‘Talking Peace: A Population-Based Survey on Attitudes about Security, Dispute Resolution and Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Liberia,’ Berkeley, CA: Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley, 2011, p.34; (2) M. Omanyondo, Sexual Gender-Based Violence and Health Facility Needs Assessment, Monrovia, Liberia: World Health Organization 2005; and (3) E. Johnson Sirleaf, ‘Liberia's Gender-Based Violence National Action Plan’, January 2007 (at: http://www.fmreview.org/sexualviolence).

12. Secretary-General of the United Nations, ‘Twenty-Fifth Progress Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Liberia', United Nations Security Council, 28 Feb. 2013 (at: www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2013/124).

13. J. Friedman, ‘Building Civilian Police Capacity: Post-Conflict Liberia, 2003–2011', Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University, 2011 (at: www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties), p.2.

14. Ibid.

15. For more on Liberia's Rule of Law and Security Sector Reform, see T. Blume, ‘Implementing the Rule of Law in Integrated Missions: Security and Justice in the UN Mission in Liberia’, Journal of Security Sector Management, Vol.6, No.3, 2008 (at: http://www.gsdrc.org/go/display&type=Document&id=4887)

16. Much of the content and many of the interviews cited in this article are derived from historical case studies produced by Princeton University's research programme, Innovations for Successful Societies, especially Laura M. Bacon, ‘Building an Inclusive, Responsive National Police Service: Gender-Sensitive Reform in Liberia, 2005–2011', Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University, 2012 (at: www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties).

17. Ibid.

18. For more on UNSCR 1325 and the other resolutions mentioned, see United States Institute of Peace, ‘What Is UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and Why Is It So Critical Today’ (at: www.usip.org/gender_peacebuilding/about_UNSCR_1325), accessed 6 Jun. 2013.

19. E. Blunt, ‘Liberian Leader Breaks Rape Taboo', BBC News, 2006 (at: news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4632874.stm).

20. The goal was originally set at 15 per cent female officers by 2014, but in 2008 the target was increased to 20 per cent by 2014, as codified in Liberia's Poverty Reduction Strategy. For more, see (1) Republic of Liberia (n.7 above); and (2) Office of the UNMIL Gender Adviser, OGA, ‘Gender Mainstreaming in Peacekeeping Operations: Liberia 2003–2009. Best Practices Report', Accra, Ghana: United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL), Sept. 2010.

21. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Women UN Peacekeepers: More Needed', IRIN Humanitarian News and Analysis, 2010 (at: www.irinnews.org/printreport.aspx?reportid=89194).

22. An Act establishing Ministry of Gender and Development. Government of Liberia, 6 August 2012 (at: www.infoliberia.org).

23. Liberia Ministry of Gender and Development, ‘2011 Annual Report’, 2012 (at: www.mogd.gov.lr).

24. For more, see Gender Based Violence Interagency Taskforce, ‘National Plan of Action for the Prevention and Management of Gender Based Violence in Liberia (GBV-POA)', 2006 (at: temp.supportliberia.com/assets/34/National_GBV_Plan_of_Action_2006.pdf).

25. In 2009, Liberia's Truth and Reconciliation Commission ruled that Johnson Sirleaf should be banned from government for 30 years because of her early support for Liberian President Charles Taylor. More information can be found in G. Gordon, ‘In Liberia, Sirleaf's Past Sullies Her Clean Image', Time, 3 Jul. 2009 (at: www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1908635,00.html).

26. See Appendices B1, B2, and C for more data on donors, aid inflows and development finance.

27. United Nations Security Council (2003), Resolution 1509 (at: www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1509%20%282003%29), accessed 6 Jun. 2013.

28. United Nations Mission in Liberia, ‘Mandate', 2013 (at: www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unmil/mandate.shtml).

29. Friedman (see n.13 above).

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid., p.2.

32. Bacon (see n.16 above).

33. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘The New War Is Rape', IRIN Humanitarian News and Analysis, 2009 (at: www.irinnews.org/printreport.aspx?reportid=87122).

34. United Nations Mission in Liberia, ‘Research on Prevalence and Attitudes to Rape in Liberia', UNMIL Legal and Judicial System Support Division Coordinator, 2008 (at: www.stoprapenow.org/uploads/advocacyresources/1282163297.pdf), p.30.

35. As cited in UNIFEM, ‘Liberia: Supporting Women's Engagement in Peace Building and Preventing Sexual Violence: Community-Led Approaches', 2007 (at: www.unifem.org/afghanistan/docs/pubs/07/DFID/liberia.pdf), p.7.

36. For an in-depth description and analysis of Liberia's customary/traditional local justice systems, see D.H. Isser, S.C. Lubkemann and S. N'Tow, ‘Looking for Justice: Liberian Experiences with and Perceptions of Local Justice Options', United States Institute of Peace, 2009 (at: www.usip.org/files/resources/liberian_justice_pw63.pdf).

37. N.N. Schia and B. de Carvalho, ‘Nobody Gets Justice Here!’, Addressing Sexual and Gender-Based Violence and the Rule of Law in Liberia, Security in Practice 5, NUPI Working Paper 761, 2009 (at: www.nupi.no/content/download/10158/102232/version/5/file/SIP-5-09-Schia-de+Cavalho-pdf.pdf); S. Maturu, ‘To Combat Violence in Liberia: A Need for Sharper Focus on Traditional Justice', Stimson, 2012 (at: www.stimson.org/spotlight/to-combat-sexual-violence-in-liberia-a-need-for-sharper-focus-on-traditional-justice/).

38. Republic of Liberia, ‘Population and Housing Census’, 2008 (at: www.emansion.gov.lr/doc/Population_by_County.pdf).

39. LNP also engaged in other gender-sensitive initiatives, such as the drafting of a gender policy, the creation of a gender unit and the coordination of an association of female police officers. The description and evaluation of these other gender-related projects is beyond the scope of this article because (1) these projects did not engage donors to the same extent as the recruitment of female officers through the Education Support Programme (ESP) and the creation of the Women and Children Protection Section (WACPS), and (2) ESP and WACPS are arguably more innovative and unique than the initiatives mentioned above. Readers interested in learning more about the gender unit can find more information at C. Bowah and J.E. Salahub, ‘Women's Perspectives on Police Reform in Liberia: Privileging the Voices of Liberian Policewomen and Civil Society’, in Salahub (ed.), African Women on the Thin Blue Line: Gender-Sensitive Police Reform in Liberia and Southern Sudan, Ottawa, ON: The North-South Institute, 2011, pp.11–39, and the association of female police officers at J. Becker, C.B. Brown, A.F. Ibrahim and A. Kuranchie, ‘Freedom through Association: Assessing the Contribution of Female Police Staff Associations to Gender-Sensitive Police Reform in West Africa', Canada: The North–South Institute, 23 Apr. 2012.

40. Republic of Liberia (see n.7 above), pp. 164–5; Gender Based Violence Interagency Taskforce (see n.24 above), p.32.

41. In an example from another country, see N. Mandhana, ‘Anti-Rape Law Means India Needs More Female Cops', The New York Times , 2 Apr. 2013 (at: india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/02/anti-rape-law-means-india-needs-more-female-cops/); interviews with Patricia Kamara, Assistant Minister, Ministry of Gender and Development, Liberia and Vera Manly, WACPS Chief, Liberia National Police, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011; S. Payne, ‘Rape: Victims Experience Review', London: Home Office, National Archives, UK, 2009 (at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/documents/vawg-rape-review/rape-victim-experience2835.pdf?view=Binarywebarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/), p.16. This is not to imply that male officers cannot investigate sexual assault cases responsibly or well. Liberia trains all of its officers – male and female – in proper investigation techniques. And the majority of LNP officers, including WACPS officers, are male.

42. More biographical information on both women can be found in Bacon (see n.16 above). Munah Sieh stepped down from her position in 2009. As of the submission of this article, she had been indicted around corruption related to irregularities in the procurement of officer uniforms, an allegation she denied, and the case was pending in the Liberian Supreme Court.

43. Correspondence with Sylvia Bisanz, Community Relations Adviser, UNPOL, UNMIL, 8 Jul. 2011.

44. Republic of Liberia, ‘Liberia Demographic and Health Survey 2007’, 2007 (at: http://www.measuredhs.com/publications/publication-FR201-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm), cited in L.M. Bacon, ‘Liberia Leans In', ForeignPolicy.com, 2013 (at: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2013/06/03/liberia_leans_in).

45. For many more details on the ESP programme, please see Bacon (n.16 above).

46. Correspondence with Sylvia Bisanz (see n.43 above).

47. Ibid.

48. See Appendix D for more details on the ESP programme. Some women were trained through the programme but did not join the LNP immediately. Others dropped out and never joined the LNP. Office of the UNMIL Gender Adviser (see n.20 above).

49. C. Griffiths and K. Valasek, ‘Liberia Country Profile', in Miranda Gaanderse and Kristin Valasek (eds), The Security Sector and Gender in West Africa: A Survey of Police, Defence, Justice and Penal Services in ECOWAS States, Geneva: DCAF, 2011, pp.141–58, p.147.

50. Secretary-General of the United Nations www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2013/124 (see n.12 above).

51. B. de Carvalho and N.N. Schia, ‘The Protection of Women and Children in Liberia', Police Brief, 1. Norway: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, 2009, p.1.

52. A. Boutellis, ‘Interview with Kadi Fakondo, Assistant Inspector General, Sierra Leone Police’, 5 May 2008 (at: www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties/oralhistories/); United Nations Women, ‘Policing with Compassion', Women as Partners in Peace and Security, October 2004 (at: www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/resources/faces/9-Police_faces_en.pdf); Sierra Leone Police/Ministry of Social Welfare, Gender and Children's Affairs, ‘The Family Support Unit Training Manual', 2008 (at: www.britishcouncil.org/fsu_training_manual.pdf).

53. Secretary-General of the United Nations, ‘Twenty-Fourth Progress Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Liberia', United Nations Security Council, 15 Aug. 2012 (at: daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N12/453/81/PDF/N1245381.pdf).

54. For more about the court and its relation to Liberia's plans to combat SGBV, see the court's founding document (at: legislature.gov.lr/sites/default/files/Criminal%20Court%20E.pdf) and (stoprapenow.org/uploads/features/SGBVemail.pdf).

55. For more about and criticism of the in camera approach in Criminal Court E, see E.S. Abdulai, ‘Evaluation: Strengthening of Prosecution of SGBV Offenses through Support to the Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Crimes Unit (SGBV CU)', Independent consultant report sponsored by Republic of Liberia and UNFPA, Nov. 2010 (at: www.mdtf.undp.org/document/download/6383), pp.19–20.

56. Ibid.

57. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Special Court for Sexual Violence Underway', IRIN: Humanitarian News and Analysis, 21 Mar. 2008 (at: www.irinnews.org/report/77406/liberia-special-court-for-sexual-violence-underway).

58. Interview with William Mulbah, deputy director for training and development at the National Police Training Academy, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

59. Ibid.

60. Bacon (see n.16 above).

61. Interview with John Nielsen, deputy commissioner of UN Police (in 2013, commissioner of UN Police), Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

62. Ibid.

63. Interviews with Bose, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011 and Asatu Bah-Kenneth, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

64. Interviews with Abla Gadegbeku Williams, former LNP officer and deputy commissioner of the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

65. Ibid.

66. Ibid.

67. Interview with Sylvia Bisanz, Community Relations Adviser, UNPOL, UNMIL, Jun.–Jul. 2011.

68. A. Boutellis, ‘Interview with Paavana Reddy, Civil Society Officer for UNDP and Technical Assistant to Ministry of Gender and Development, Liberia’, 17 May 2008 (at: www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties/oralhistories/www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties/oralhistories/).

69. Isser et al. www.usip.org/files/resources/liberian_justice_pw63.pdf (see n.36 above).

70. UNMIL, ‘New Confidence in Liberian Police Has More Women and Children Reporting Crime', 15 Jun. 2008 (at: reliefweb.int/report/liberia/new-confidence-liberian-police-has-more-women-and-children-reporting-crime).

71. Ibid.

72. Interview with William Mulbah, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

73. Interview with US Embassy official, who wished not to be named, 2011.

74. To address this problem, UNMIL along with the LNP/WACPS instituted periodic in-service or refresher courses to enable section investigators to revisit important aspects of their training. To complement in-service training, the Norwegian Refugee Council offered WACPS officers courses based on the Ministry of Justice's handbook on prosecuting sexual and gender-based crimes.

75. Interview with Bah-Kenneth (see n.63 above).

76. Interview with Anna Stone, project manager of the SGBV project at the Norwegian Refugee Council, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

77. Interviews with Korlu Kpanyor, head of WACPS Juvenile Unit, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

78. Interviews with Vildana Sedo, Acting UNPOL gender adviser, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

79. Ibid.

80. Secretary-General of the United Nations (see n.53 above).

81. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Liberia: Sexual Violence Projects Could Suffer Post-UNMIL', IRIN: Humanitarian News and Analysis, 18 May 2010 (at: www.irinnews.org/printreport.aspx?reportid=89127).

82. Secretary-General of the United Nations (see n.12 above).

83. Interview with Anna Stone (see n.76 above).

84. Interview with Felicia Coleman, head of SGBV unit, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

85. A.M. Wolokolie, ‘Liberia: Lack of Evidence Hinders Fight against Rape', The Inquirer, Monrovia, Liberia, 21 Feb. 2013 (at: allafrica.com/stories/201302211190.html).

86. J. Moore, ‘Liberia's “Rape Court”: Progress for Women and Girls Delayed?’, Christian Science Monitor , 10 Oct. 2010 (at: www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/Africa-Monitor/2010/1010/Liberia-s-Rape-Court-Progress-for-women-and-girls-delayed); Abdulai (see n.55 above), pp.11–12.

87. Abdulai (see n.55 above), p.21.

88. Ibid.

89. Ibid.

90. Ibid., p.20.

91. Interview with Felicia Coleman (see n.84 above).

92. M. Andrews, L. Pritchett and M. Woolcock. ‘Escaping Capability Traps Through Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA)', Faculty Research Working Paper Series, Harvard, 2012, p.2 (at: https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/getFile.aspx?Id=841).

93. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘County Nominees Rejected as New Parliamentarians Meet', IRIN: Humanitarian News and Analysis, 13 Oct. 2003 (at: www.irinnews.org/printreport.aspx?reportid=46681).

94. A. Boutellis, ‘Interview with Dave Beer, Chief Superintendent, Director General of International Policing, Royal Canadian Mounted Police’, Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University, 15 Jan. 2008 (at: https://www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties/oralhistories/).

95. Interview with Regina Sokan-Teah, Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

96. United Nations Security Council, ‘Security Council Extends Mandate of Liberia Mission Until 30 September 2013, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2066 (2012)', 17 Sep. 2012 (at: http://www.un.org/press/en/2012/sc10765.doc.htm).

97. Secretary-General of the United Nations (see n.12 above).

98. Interview with Napoleon Abdulai, security sector reform adviser, UNDP, Jul. Monrovia, Liberia, Jun. and Jul. 2011.

99. Ibid.

100. Ibid.

101. Ibid.

102. Interview with Nielsen (see n.61 above).

103. Ibid.

104. Secretary-General of the United Nations (see n.12 above).

105. Blume (see n.15 above).

106. Secretary-General of the United Nations (see n.12 above), emphasis added.

107. Schia and de Carvalho (see n.37 above).

108. Ibid., citing S. Cliffe and N. Manning, ‘Practical Approaches to Building State Institutions’, in Charles T. Call and Vanessa Wyeth (eds), Building States to Build Peace, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2008, pp.163–84.

109. Maturu (see n.37 above).

110. Isser et al. (see n.36 above), pp.4, 25, 31, 70 , as quoted in Maturu (see n.37 above).

111. Ibid.; Schia and de Carvalho (see n.37 above), p.19.

112. Schia and de Carvalho (see n.37 above), p.19.

113. Niels Nagelhus Schia and Benjamin de Carvalho, ‘Addressing Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Liberia’, Conflict Trends, p.26–33 (at: http://www.academia.edu/10158898/Addressing_Sexual_and_Gender-Based_Violence_in_Liberia).

114. Maturu (see n.37 above).

115. Isser et al. (see n.36 above).

116. Ibid.

117. Ibid, p.5.

118. Interview with Nielsen (see n.61 above).

APPENDIX A: LIBERIA GDP PER CAPITA

Source: Index Mundi, ‘Liberia — GDP per Capita (Current US$)’, 2013 (at: www.indexmundi.com/facts/liberia/gdp-per-capita).