Abstract

Over the past two decades, community-based approaches to project delivery have become a popular means for governments and development agencies to improve the alignment of projects with the needs of rural communities and to increase the participation of villagers in project design and implementation. This article briefly summarizes the results of an impact evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme (NSP), a community-driven development programme in Afghanistan that created democratically-elected community development councils and funded small-scale development projects. Using a randomized controlled trial across 500 villages, the evaluation finds that NSP had a positive effect on access to drinking water and electricity, acceptance of democratic processes, perceptions of economic well-being and attitudes towards women. Effects on perceptions of local and national government performance and material economic outcomes were, however, more limited or short-lived.

Introduction

Since the mid-1980s, community-based approaches to project delivery have become increasingly popular with governments and development agencies.Footnote1 Such approaches – termed Community-Driven Development (CDD) – grew out of the perceived lack of responsiveness of ‘top–down’ programmatic modalities to local needs.Footnote2 Spurred by academic studies that affirmed the ability of communities to solve collective action problems,Footnote3 CDD programmes sought to emphasize participatory planning modalities by which community members identify projects that address their specific priorities.Footnote4 Such processes, it is often hypothesized, may not just provide for better-targeted and more efficient projects, but also can increase participation in local institutions and, with it, build social capital.Footnote5

Of the myriad CDD initiatives throughout the developing world, few have garnered as much attention as the National Solidarity Programme (NSP), Afghanistan's largest development programme. Conceived soon after the fall of the Taliban regime, NSP was designed to extend the administrative reach of the state, build representative institutions for local governance and deliver critical services to the rural population. In villages covered by the programme, NSP has created gender-balanced Community Development Councils (CDC) through a secret-ballot, universal suffrage elections. Once constituted, CDCs have drafted community-development plans and developed proposals for village-level development projects that, subject to basic criteria being met, have been funded by NSP through the disbursement of block grants.

Following the implementation of the first phase of NSP from 2003 to 2007, international donors and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan requested that the impacts of the programme be rigorously evaluated by independent researchers, resulting in the NSP Impact Evaluation (NSP-IE). In the initial stages of the design of the NSP-IE, a financial constraint arose that limited the number of villages in each district that could be covered by the programme between 2007 and 2011. This financial constraint, in conjunction with demands from stakeholders for a rigorous impact evaluation, informed a joint decision by NSP, stakeholders and the NSP-IE research team to randomize the roll-out of NSP across 500 villages in 10 districts spanning northern, eastern, central and western Afghanistan, with 250 ‘treatment’ villages receiving NSP in 2007 and 250 ‘control’ villages not receiving NSP until 2012. NSP-IE midline estimates were provided by a comparison of economic, political and social indicators in treatment and control villages in 2009, with endline estimates provided by a comparison of the same indicators in 2011.

The collective NSP-IE findings provide some instructive lessons for development interventions in fragile contexts. That NSP provides a fleeting impetus to perceptions of central and sub-national government indicates that government legitimacy is contingent on the continued delivery of services rather than improved development outcomes per se. The durable positive effects of NSP on acceptance of democratic norms and female participation further suggest that the mandating of such practices by development programmes can spur social change. However, the relative ineffectiveness of CDCs in changing de facto village leadership structures and the negative impact on perceived local governance quality indicates that the creation of new institutions in parallel to customary structures may not have the desired effect, particularly in cases in which the roles of new institutions are not well defined.

The NSP-IE falls within a class of four rigorous evaluations of CDD programmes conducted across fragile contexts in the late 2000s.Footnote6 King and Samii synthesize the findings of these studies, concluding that attempts by CDD programmes to build local institutions in conflict-affected areas have generally been unsuccessful in generating durable and transferable increases in collective action.Footnote7 They note that the low intensity of these interventions, coupled with mismatches between evaluation and programmatic time-frames, may explain part of the underperformance. On the basis of a similar review, Bennett and D'Onofrio, attribute the mixed evidence of CDD programmes in conflict-affected contexts to the lack of a coherent and explicit theory of change.Footnote8 It should be noted that NSP has expressed the view that some of the findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this summary – and particularly those pertaining to the impacts of the programme on the quality of local governance and of the impacts of infrastructure projects – do not reflect its observations and are accordingly disputed.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: section two describes the history and characteristics of NSP; section three examines the development context in Afghanistan; section four reviews the NSP-IE methodology and data sources; section five summarizes the effects of NSP on economic, institutional and social outcomes; section six discusses the implications of the findings for development projects in Afghanistan and other fragile environments; and section seven concludes.

Programmatic Context

NSP is executed by the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development, funded by the World Bank and a consortium of bilateral donors, and facilitated by 8 national and 21 international NGOs. Programme implementation is structured around two major interventions at the village level:Footnote9

The election of a gender-balanced CDC through a secret-ballot, universal suffrage election centred on democratic processes and women's participation.Footnote10

The provision of ‘block grants’ – valued at US$200 per household, up to a village maximum of US$60,000 and averaging US$33,000 – to fund village-level projects designed and selected by CDCs in consultation with villagers.Footnote11

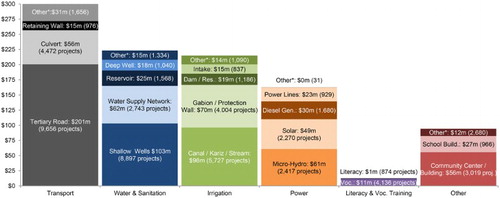

Projects financed by NSP generally fall into one of six categories: transport; water and sanitation; irrigation; power; literacy and vocational training; and other (). Between mid-2003 and early 2013, over 64,000 projects were funded by NSP, at a combined cost of US$1.01 billion.Footnote12

FIGURE 1 PROJECTS FINANCED BY NSP, BY AGGREGATE FUNDING ALLOCATED

In each village, NSP implementation takes approximately three years. The process of facilitating CDC elections usually takes about 6 months, after which an average of 12 months elapse before project implementation starts. During this period, CDCs design projects in conjunction with villagers, submit proposals, receive funds and, if necessary, procure contractors. Project construction lasts an average of nine months.

Once implementation of NSP in a village concludes, villages have no assurance of when – or if – they will receive further NSP activities, either in the form of facilitated CDC elections or block grants. However, in the current third phase of the programme, NSP is extending repeater block grants to around 12,000 villages mobilized in the programme's first phase between 2003 and 2007.Footnote13

Country Context

Afghanistan's population is overwhelmingly rural, with 80 per cent of the population living outside the country's regional and provincial centres.Footnote14 Generally, those living in rural areas suffer from tenuous agriculture-based livelihoods and limited access to basic amenities, such as clean drinking water, reliable irrigation and electricity. During the past ten years, various donor-funded interventions have attempted to enhance food security, improve economic opportunities and provide access to basic infrastructure. However, the incidence of poverty in rural areas remains very high, with Afghanistan ranking among the bottom 15 countries in UNDP's Human Development Index.

Due to conflict and a lack of state consolidation, Afghanistan's central government has historically been weak, with limited capacity for service provision. In response, rural communities throughout the country have developed informal yet sophisticated customary local governance structures. The foundation of these structures is the local jirga or shura, a participatory council that has traditionally managed local public goods and adjudicated disputes.Footnote15 Members of such councils are generally the elder males of families in the village.Footnote16 Villages also ordinarily have a headman (termed a malik, arbab or qariyadar) – usually a large landowner – who liaises with district, provincial and central authorities.Footnote17 The local religious authority, the mullah, is responsible for conducting rites and services and mediating disputes involving family or moral issues.Footnote18

In rural Afghanistan, women are generally barred from activities outside the household. Such norms render local governance a male-dominated activity.Footnote19 Female mobility is also constrained by customs that require a woman travelling outside her village to have a male relative as an escort. As a result of these norms, girls are usually prevented from attending school beyond fourth grade and, without education or mobility, are constrained in their ability to generate income.

Methodology and Data Sources

The NSP-IE represents a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the second phase of NSP. In mid-2007, 500 villages eligible for the programme were selected jointly by the NSP-IE research team, NSP and facilitating partners. The 500 villages are equally spread across 10 districts in Balkh, Baghlan, Daykundi, Ghor, Herat and Nangarhar provinces.Footnote20 The ten districts depict Afghanistan's ethno-linguistic diversity, with five predominantly Tajik districts, four predominantly Pashtun districts and one predominantly Hazara district. However, due to ongoing violent conflict, villages from the southern provinces, such as Kandahar and Helmand, were not able to be included in the sample.

Using a matched-pair cluster randomization procedure, 250 of the 500 villages were randomly selected to receive NSP in 2007 and comprise the treatment group for the study, with the remaining villages assigned to the control group.Footnote21 The matched-pair cluster randomization facilitates a transparent and unbiased estimation of programme impacts by ensuring that the background characteristics of the treatment group are, on average, identical to the control group.Footnote22 Accordingly, any differences that arise between the two groups of villages are attributable to NSP.

Baseline, midline and endline surveys were administered to a random sample of village households, as well as to male and female focus groups of village leaders, between August 2007 and October 2011.Footnote23 Collectively, the surveys comprised over 25,000 household interviews with male and female villagers, as well as more than 2,600 focus groups with male village leaders and women. The midline survey is used to estimate impacts of NSP two years after the start of NSP implementation and after all treatment villages had elected CDCs and selected projects, but prior to the completion of 82 per cent of NSP-funded projects.Footnote24 The endline survey is used to estimate impacts four years after implementation and after 99 per cent of NSP-funded projects had been completed, but prior to the implementation of NSP in control villages.

The hypotheses to be tested by the NSP-IE, constituent indicators and the survey questions and specifications used to form indicators were formalized in a pre-analysis plan. The pre-analysis plan was completed prior to the receipt of endline survey data and registered with the Experiments in Governance and Politics (EGAP) network.Footnote25 The pre-analysis plan groups hypotheses and indicators into five broad categories of outcomes of interest: (1) access to services, infrastructure and utilities; (2) economic welfare; (3) local governance; (4) political attitudes and state-building; and (5) social norms.Footnote26 The hypotheses were not formulated to judge the effectiveness of NSP in meeting pre-identified program objectives, but rather to more broadly explore the reaches of program impact. As such, the hypotheses include both formal ‘project development objectives’ for which the project should be held accountable as well outcomes of general interest identified by the research team.Footnote27

Results

This section presents estimates of the midline and endline impacts across the five categories listed above.Footnote28

Access to Utilities, Services and Infrastructure

NSP improves the access of villagers to basic utilities. NSP-funded drinking water projects increase access to clean drinking water, with the programme increasing usage of protected sources by 15 per cent at endline. NSP also reduces the time that households spend collecting water by 5 per cent, although the programme has no lasting impact on perceived water quality or on the incidence of water shortages. NSP substantially boosts electricity usage, which rises by 26 per cent. The size of these effects is substantially higher when the impacts of NSP-funded water and electricity projects are examined specifically, rather than the impact of NSP generally.

NSP also increases access to services, including education, health care and counselling services for women. As NSP does not usually fund such services, these impacts appear to arise indirectly from other changes induced by NSP. While there is no impact on boys’ school attendance, NSP increases girls’ school attendance and their quality of learning. NSP further increases child doctor and prenatal visits and the probability that a woman's illness or injury is attended to by a medical professional, although it does not affect other health outcomes. Finally, NSP more than doubles the proportion of women who have a group or person with whom they can discuss their problems.

NSP-funded infrastructure projects in irrigation and transportation, however, appear to be less successful. Specifically, irrigation projects have no impact on the ability of land-holding villagers to access sufficient irrigation. Although there is weak evidence that transportation projects increase village accessibility at midline, the impact does not persist and there is no evidence of impacts on the costs and times of traveling from the village to the district center or on the mobility of male villagers.

There is weak evidence to indicate that, once complete, NSP-funded projects fulfil the development needs of male villagers, as measured by relative changes in the types of projects that are identified as being most needed by the village. NSP appears to specifically fulfil demands for drinking water projects, which were identified as necessary by a higher proportion of male villagers than any other projects at baseline. The impacts of NSP on aggregate categories of indicators on access to utilities, services and infrastructure are presented in .

TABLE 1 AGGREGATE IMPACT OF NSP ON ACCESS TO UTILITIES, SERVICES AND INFRASTRUCTURE

Economic Welfare

NSP impacts the economic perceptions and optimism of villagers, particularly women. Female villagers exhibit improved perceptions of the current economic situation and are more optimistic about future changes in the local economy, both at midline and endline. The economic perceptions and optimism of male villagers improve at midline, but there is only weak evidence of an impact at endline on optimism and no evidence of a longer-term impact on perceptions.

Despite the changes in economic perceptions, there are few impacts of NSP on objective economic outcomes. At midline, there is weak evidence that NSP induces small increases in the diversity of household income sources and in caloric intake, although both impacts do not persist after project completion. At endline, there is weak evidence of impact on the amount borrowed by households. NSP appears to have no robust impacts at midline or endline on income levels, income regularity, consumption levels, consumption allocations, assets or food insecurity.

There is also no evidence that NSP impacts general production and marketing outcomes. NSP has no discernible impacts on agricultural yields, productivity or the proportion of harvests sold, although the programme induces a fleeting increase at midline in agricultural sales revenue. NSP also does not affect whether households sell animals or animal products or the revenue derived from such activities. While NSP increases handicraft sales and sales revenue at midline, these impacts disappear following project completion.

At endline and midline, there is evidence that NSP reduces the net migration of households from villages, although both results lose statistical significance if migration patterns at baseline are controlled for. In addition, there is no evidence at endline that NSP induces any changes in net within-household migration.

The limited impact of NSP on economic welfare is potentially explained by the apparent ineffectiveness of infrastructure projects in inducing changes in agricultural productivity and access to markets and by the fact that more successful types of projects (such as water and electricity) are not designed to induce changes in local economic activity in the near-term. However, the sustained positive impact on female economic perceptions demonstrates the broader improvements brought to women's lives by female participation in CDC activities and by NSP-funded drinking water projects.

The impacts of NSP on aggregate economic welfare indicators are presented in .

TABLE 2 AGGREGATE IMPACT OF NSP ON ECONOMIC WELFARE

Local Governance

The creation of CDCs by NSP more than doubles the proportion of local assemblies that contain at least one female member. CDC creation also causes customary leaders to affiliate with representative assemblies during project implementation, although this effect is not sustained beyond project completion. There is no evidence that NSP changes the composition of local leadership or introduces new leaders into the core group of village decision-makers.

At midline, the creation of CDCs by NSP increases the provision of local governance services, the activity level of customary authorities and the role of representative assemblies in providing local governance services. These impacts generally do not persist following the completion of NSP activities in treatment villages, although NSP does result in a durable increase in the number of meetings held annually by representative assemblies. There is also strong evidence that NSP induces a durable increase in the provision of local governance services specific to women.

NSP increases villager participation in local governance at midline, as measured by meeting attendance and a desire to change leader decisions, and increases the proportion of villagers that prefer representative assemblies to be involved in local governance. However, while the desire to change leader decisions persists beyond project completion, NSP has neither a durable impact on the probability of villagers attending assembly meetings nor on the extent to which they believe assemblies should be involved in local governance.

At endline, NSP has a negative impact on local governance quality as perceived by male villagers, reducing satisfaction with the work of local leaders by 8 per cent and almost doubling dissatisfaction with the recent decisions or actions of village leaders. While NSP induces an increase at midline in the extent to which village leaders are perceived as being responsive to the needs of women, this effect does not persist.

The impacts of NSP on aggregate local governance indicators are presented in .

TABLE 3 AGGREGATE IMPACT OF NSP ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE

Political Attitudes and State-Building

The evidence of NSP's impact on democratic values is mixed. There is strong evidence that NSP increased voting in the 2010 parliamentary elections, with the proportion of male and female villagers who claimed to have cast a ballot being 4 and 10 per cent higher, respectively, in treatment villages. NSP also appears to raise appreciation of democratic elections, at least as manifested by a 24 per cent increase in the proportion of male villagers who prefer that the village headman is subject to a secret-ballot election. However, NSP has no effect on female views of democratic elections, on participatory decision-making procedures or on the already-high proportion of male villagers who believe the President or provincial governor should be elected. NSP also has no impact on the proportion of villagers who believe it appropriate to discuss governance issues publicly or who support the participatory resolution of major village issues.

There is only weak evidence that NSP increases the legitimacy of the central government. In particular, NSP has no impact on whether villagers believe that the government should exercise jurisdiction over local crimes, set the school curriculum, issue ID cards or collect income tax. Furthermore, NSP has no impact on whether villagers prefer a centralized state (as opposed to a weak federation) or who identify primarily as Afghan (as opposed to a member of a specific ethnic group). At midline, NSP increases linkages of villages with government officials and representatives of the Afghan National Security Forces, although these effects do not last beyond the period of project implementation.

There is strong evidence that NSP improves perceptions of government entities at midline, but only weak evidence of such impacts at endline. During project implementation, NSP induces a highly significant increase in the reported benevolence of a wide range of government entities, but this impact mostly fades following project completion, with weak positive impacts observed only for the President and central government officials. This pattern is also true of perceptions of NGO officials, although NSP has a durable positive impact on perceptions of International Security Assistance Force soldiers. While the impacts of NSP on perceptions of government at midline indicate that the programme is generally perceived as government-owned, the reversion of villagers to original attitudes vis-à-vis the government once project funds are expended seems to imply that government legitimacy is tied more to the regularized provision of public goods than to development outcomes per se.

NSP does not appear to impact the likelihood of villages suffering violent attacks (at least as reported by villagers) at midline or endline. There is also no evidence that NSP affects the ability of insurgent groups to expropriate harvests. However, NSP improves perceptions of the local security situation among both male and female villagers at midline, although only the impacts observed for male villagers persist beyond project completion.

The impacts of NSP on aggregate categories of indicators measuring political attitudes and state-building are presented in .

TABLE 4 AGGREGATE IMPACT OF NSP ON POLITICAL ATTITUDES AND STATE-BUILDING

Social Norms

In accordance with observations that public resource decisions can sometimes aggravate intra-communal divisions, we find weak evidence that, during project implementation, NSP increases the incidence of disputes and feuds, while reducing the rate at which such disputes are resolved. Once projects are complete, this general effect disappears, however, and there is weak evidence that NSP slightly reduces intra-village disputes at endline. There is also some evidence at endline that NSP increases interpersonal trust among male villagers, although no evidence of a midline impact for male villagers or an impact at midline or endline for female villagers. Given the small magnitude of the observed changes, there is no evidence of a discernible impact of NSP on aggregate measures of social cohesion.

During project implementation, NSP improves the basic literacy and computation skills of male and female villagers, although these impacts do not last. There is also some evidence that NSP makes villagers happier. Specifically, there is weak evidence of a reduction in the proportion of female villagers who report that they are unhappy, a result that could be caused by the increased availability of counselling services for women, increased female participation in local governance and/or increased access to basic utilities and services.

NSP increases men's acceptance of female participation in political activity and local governance. Specifically, the programme increases male acceptance of female electoral participation, national candidacy by women and women holding civil service or NGO positions by 3, 4 and 6 per cent respectively. NSP also causes a 22 per cent increase in acceptance of female membership of village councils and a 15 per cent increase in acceptance of female participation in the selection of the village headman. The impact of NSP on women's views on female participation in political activity and local governance is more marginal. NSP also appears to have limited impacts on reducing cultural constraints limiting female educational opportunities.

Beyond attitudes, NSP has positive impacts on gender outcomes. NSP has durable positive impacts on the participation of women in local governance. Specifically, a 21 per cent increase is observed in the participation of women in dispute mediation and a 14 per cent increase is observed in the involvement of women in aid allocation. Although NSP does not appear to impact intra-village mobility of women, female socialization or female participation in economic activity or household decision making, it does produce a durable increase in the ability of women to travel beyond their village. Specifically, women in NSP villages are 13 per cent more likely to have visited the nearest village in the past year and 11 per cent more likely to have visited the district centre in the past month.

The size of the impact of these results in the aggregate categories of indicators is presented in .

TABLE 5 AGGREGATE IMPACT OF NSP ON SOCIAL NORMS

Discussion

The study's results provide a rigorous assessment of the absolute impact of NSP on a broad set of outcomes. Comprehensive though they may be, the results have important limitations. In the absence of other comparable evaluations on other development programmes in Afghanistan, the findings of the NSP-IE do not allow comparisons to be made between the effectiveness of NSP and other programmes. For the same reason, it is very difficult to make qualitative judgements concerning the relative size of the observed impacts or whether they collectively might be used to designate NSP as a ‘successful’ or ‘unsuccessful’ project.

The results nonetheless point to several areas of achievement and other areas of concern. The participatory approach adopted by NSP has borne fruit in developing a role for women in local public decision making and, in so doing, countering the traditional dominance of male elites over local governance. NSP bridges the considerable gap between villages and the central government, while drinking water and electricity projects funded by the programme address critical needs of villagers and improve their lives. On the other hand, the relative ineffectiveness of NSP-funded infrastructure projects calls for further investigation. Likewise, some of the results suggest that it may be necessary to assess whether the presence of CDCs inadvertently diffuses institutional accountability in Afghan villages.

The following sections discuss implications of the results for other development projects in post-conflict settings, with a focus on how projects can best enhance government legitimacy, strengthen local accountability and participation and facilitate the acceptance of the participation of marginalized groups in local public affairs.

Effects on Government Legitimacy

NSP is funded by the World Bank and bilateral aid agencies, managed by the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development and facilitated by 29 NGOs. This arrangement has allowed NSP to benefit from the substantial local knowledge and expertise built up by the NGO sector in Afghanistan during the two decades of conflict the country suffered prior to 2001, while also clearly linking the programme with the Government of Afghanistan.

The NSP-IE results suggest that, while NSP increases the favourability of individuals’ views towards the government, this effect fades after the completion of NSP-funded projects. This, in turn, indicates that villagers perceive NSP as a government-sponsored intervention and that government support is contingent upon the continual provision of public goods and services, such as development projects. Thus, even though NSP-funded projects deliver a development impact in improving access to utilities, this is not sufficient to improve perceptions of government unless there is an expectation of future service provision.Footnote29 Accordingly, the effects of development interventions on government legitimacy in post-conflict settings may be maximized by instituting a regularized and frequent pattern of project activity.

Accountability of Local Governance Structures

Local ownership is a core principle of NSP, with the mandated election of CDCs and the participatory selection of public goods projects financed by NSP block grants. The process of establishing CDCs and involving villagers in project selection has produced a number of positive effects, such as increasing the number of meetings held by village assemblies, increasing participation in and preferences for democratic elections, increasing female participation in local governance and liberalizing men's attitudes to female participation in local governance.

Despite these positive effects, however, the study finds that, once NSP-funded projects are complete, the overall effect of NSP on male perceptions of the quality of local governance deteriorates. In addition, the institutional relevance of the CDC – relatively strong at midline – fades substantially following project completion. These results suggest that the diffusion of institutional authority created by the co-existence of CDCs with local customary institutions and the ambiguous mandates of CDCs following project completion may produce perverse effects on local governance. The results underscore the need to provide new local institutions with a clear mandate distinct from those of existing local institutions.

Participation of Women

The most positively surprising set of results in the study are those pertaining to the durable impacts wrought by NSP on perceptions of gender roles and on women's lives generally. Of particular note is that while other impacts – such as those on perceptions of government – are not sustained beyond project completion, the effects on gender norms and gender outcomes do not fade. These results provide a strong vindication of NSP's policy of mandating female participation in CDC elections, CDC composition, and the selection and management of sub-projects, which have produced changes in women's lives that extend far beyond both the scope of programme activities and the lifecycle of programme implementation. Accordingly, similar approaches might be adopted in development projects in other post-conflict environments to facilitate acceptance of democratic norms and participation in public affairs of women and other marginalized groups.

Conclusion

By embracing bottom–up approaches to development, CDD empowers local communities to select and manage projects which best address local priorities. NSP, the largest development programme in Afghanistan, has brought CDD to all of Afghanistan's 34 provinces and in so doing has overcome vast challenges posed by insecurity, prevailing gender norms and suspicion of the central government. The NSP-IE provides a rigorous, large-scale quantitative evaluation of the impacts of NSP across a wide range of economic, institutional and social outcomes and can potentially serve as an important tool for policy making for CDD and other programmes in Afghanistan and other post-conflict settings.

The findings of the NSP-IE identified some aspects in which NSP is succeeding and other areas where performance has been more limited. Specifically, the results show that NSP positively affects the access of villagers to drinking water and electricity, increases acceptance of democratic processes, improves perceptions of economic well-being and lessens constraints to the participation of women in public affairs. However, positive effects on attitudes towards central and sub-national government fade quickly following the completion of NSP-funded projects. Moreover, NSP negatively affected perceptions of local governance quality among male respondents, while the composition and behaviour of the customary village leadership appears to be unaffected by the intervention.

The results provide important lessons for development interventions in post-conflict contexts. First, the positive and durable impacts observed on female participation and acceptance of democratic processes are a vindication of NSP's policy of mandating female participation and democratic CDC elections in a context in which such practices contrast with local customs. Second, the positive but temporary impact of NSP on perceptions of central government indicates that development projects can assist in building government legitimacy in fragile states, but that such improvements in legitimacy are reliant upon a predictable and continuous stream of public goods and services provided by the central government. Finally, the finding that local governance as perceived by male respondents did not improve suggests caution is called for when establishing new local institutions in parallel with customary structures. Particular care must be paid to ensure that the new local bodies are provided with specific mandates distinct from those of existing institutions.

The process of conducting the NSP-IE has also generated lessons that may be useful to the design and implementation of similar development interventions. First, it is important that studies present a precise account of the specifics of the intervention and the context in which it is implemented. As demonstrated by the results of the variations tested by the NSP-IE and reported elsewhere,Footnote30 relatively minor variations in programmatic components can result in pronounced differences in impacts. Accordingly, only when provided with a precise description of the components of the programme can policy-makers make informed decisions.

Second, further efforts must be made to ensure research designs are geared towards understanding the long-term impact of programmes on outcomes of interest to policy-makers. While academics are rewarded for original experimental interventions with relatively short gestation periods, practitioners and policy-makers are often interested in understanding impacts on outcomes that may take many years to evolve and in establishing whether similar programmes have common impacts across different contexts.

Third, the ability to isolate rigorously the impact of CDD programmes – and to help them improve – is greatly enhanced where logical frameworks enumerate distinct and quantifiable outcome indicators that the programme aspires to impact. When outcome indicators are not well defined ex-ante by the programme, disagreements may arise ex-post between researchers and practitioners about whether a given outcome was measured correctly. Failures to adequately specify assumptions underlying a logical framework may meanwhile inhibit researchers from being able to isolate why a particular intervention failed to have the desired effect and provide recommendations to improve programmatic effectiveness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article directly draws from previous reports and papers.Footnote31 The analysis and interpretations here summarize particularly those presented in A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Program-Final Report, World Bank Report No. 81107. Washington, DC: World Bank’, 2013 (at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/07/18273450/randomized-impact-evaluation-afghanistans-national-solidarity-programme). Financial and logistical support for the Randomized Impact Evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme, whose results are summarized in this article, was provided by the World Bank's Trust Fund for Environmental and Socially Sustainable Development (TFESSD), the World Bank's AusAid-SAR Afghanistan Strengthening Community-Level Service Delivery Trust Fund, the World Bank's Development Impact Evaluation (DIME) initiative and the World Bank's Afghanistan Country Management Unit; and by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. The Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan financially supported data collection for the baseline, midline and endline surveys through the monitoring and evaluation budget of Phase-II of the National Solidarity Programme. The Village Benefit Distribution Analysis was supported by the World Food Programme, the US Agency for International Development; the International Growth Centre and the Canadian International Development Agency. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this summary are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent; the National Solidarity Programme, Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan or the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan; Australian Aid; the United States Agency for International Development, the Canadian International Development Agency; the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; the World Food Programme; and/or the International Growth Center.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Andrew Beath works for the World Bank’s Office of the Chief Economist for East Asia and the Pacific. Since joining the World Bank in 2010, Andrew has led the design and implementation of experimental and quasi-experimental impact evaluations of community-driven development programmes and livelihoods interventions across the Afghanistan, the Philippines, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, and Vietnam. Andrew holds a Ph.D. from the Department of Government at Harvard University and a Master of Public Administration in International Development from the Harvard Kennedy School.

Fotini Christia is an associate professor of political science at MIT. She has carried out extensive ethnographic, survey, and experimental research in Afghanistan and Bosnia and is currently working on projects in Yemen and Iraq. Her articles have been published in Science, in the American Political Science Review, and in Comparative Politics among other journals. Her book, Alliance Formation in Civil Wars, published by Cambridge University Press in 2012, was awarded the Luebbert award for best book in comparative politics, the Lepgold prize for best book ininternational relations and the distinguished book award of the ethnicity, nationalism, and migration section of the International Studies Association.

Ruben Enikolopov is an ICREA Research Professor at Barcelona Institute of Political Economy and Governance, UPF, and Associate Professor of economics at the New Economic School, Moscow. His research interests include political economy, development economics, and economics of mass media. Ruben has published his research in leading academic journals such as American Economic Review, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Proceedings of National Academy of Science, American Political Science Review, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Journal of Public Economics.

Notes

1. P. Dongier et al., ‘Community-Driven Development', in J. Klugman (ed.), A Sourcebook for Poverty Reduction Strategies, Vol. 1, Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2002, pp.303–31; G. Mansuri and V. Rao, ‘Localizing Development: Does Participation Work?’, World Bank Policy Research Report, Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2012; S. Wong, What Have Been the Impacts of World Bank Community-Driven Development Programmes? CDD Impact Evaluation Review and Operational and Research Implications, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012. As of 2012, the World Bank supported approximately 400 community-driven development projects in 94 countries (Wong, What Have Been).

2. A. Escobar, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995; J. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

3. M. Cernea (ed.), Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development, New York: Oxford University Press and World Bank, 1985; A.O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970; A.O. Hirschman, Getting Ahead Collectively: Grassroots Experiences in Latin America, New York: Pergamon Press, 1984; E. Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990; A.K. Sen, Commodities and Capabilities, Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1985; A.K. Sen, Development as Freedom, New York: Knopf, 1999.

4. Dongier et al. (see n.1 above); Wong (see n.1 above); R. Chambers, Rural Development: Putting the First Last, London: Longman, 1983.

5. D. Narayan (ed.), Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002.

6. Macartan Humphreys, Raul Sanchez de la Sierra and Peter van der Windt, ‘Social and Economic Impacts of Tuungane: Final Report on the Effects of a Community Driven Reconstruction Program in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo’, Mimeo, Columbia University, Jun. 2012; J. Fearon, M. Humphreys and J. Weinstein, ‘Democratic Institutions and Collective Action Capacity’, (forthcoming in American Political Science Review); K. Casey, R. Glennerster and E. Miguel, ‘Reshaping Institutions: Evidence on Aid Impacts Using a Preanalysis Plan*’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol.127, No.4, 2012, pp.1755–812; A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Program-Final Report, World Bank Report No. 81107. Washington, DC: World Bank', 2013 (at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/07/18273450/randomized-impact-evaluation-afghanistans-national-solidarity-programme).

7. Elisabeth King and Cyrus Samii, ‘Fast Track Institution Building in Conflict Affected Countries? Insights from Recent Field Experiments’, World Development, Vol.64, Dec. 2014, pp.740–54.

8. Bennett Sheree and Alyoscia D’Onofrio, ‘Community-Driven? Concepts, Clarity and Choices for CDD in Conflict-Affected Contexts', [International Rescue Committee Report] New York: International Rescue Committee, 23 Feb. 2015.

9. Villages must have more than 25 households to form a unitary CDC, although smaller villages may form joint CDCs with larger villages.

10. Villages are divided into ‘clusters’ of between 5 and 20 families, with each cluster electing a male and female representative to the CDC. The CDC is headed by an executive council composed of a president, deputy president, secretary and treasurer.

11. NSP features a ‘negative list’, which bans certain types of projects from receiving funding (including mosque construction, land purchases, payment of salaries to CDC members, purchase of weapons and cultivation of illegal crops). Eligible projects are generally approved by NSP provided they are endorsed through a village-wide consultation process; provide for equitable access; are technically and financially sound; include an operation and maintenance plan; and are funded by the community (including labour and material contributions) up to a level exceeding 10 per cent of the total cost.

12. A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, 2013. Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme-Final Report, World Bank Report No. 81107, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2013 (at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/07/18273450/randomized-impact-evaluation-afghanistans-national-solidarity-programme). Seventy-three per cent of NSP funding is allocated to block grants, 18 per cent to facilitation costs and 9 per cent to administration.

13. NSP Phase-III also intends to mobilize the remaining 16,000 villages that have yet to receive the programme.

14. Icon-Institute, ‘National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2007/08: A Profile of Afghanistan’, [Main Report] Cologne: Icon-Institute, 2009.

15. T. Barfield, Weak Links on a Rusty Chain: Structural Weaknesses in Afghanistan's Provincial Government Administration, Berkeley, CA: Institute of International Studies, University of California, 1984; N. Nojumi, D. Mazurana and E. Stites, ‘Afghanistan's Systems of Justice: Formal, Traditional, and Customary', Working Paper, Medford: Feinstein International Famine Center, Youth and Community Programme, Tufts University, 2004.

16. A. Rahmani, The Role of Religious Institutions in Community Governance Affairs: How Are Communities Governed beyond the District Level?, Budapest, Hungary: Open Society Institute, Central European University Center for Policy Studies, 2006.

17. P. Kakar, Fine-Tuning the NSP: Discussions of Problems and Solutions with Facilitating Partners, Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, 2005.

18. Rahmani (see n.16 above).

19. I. Boesen, From Subjects to Citizens: Local Participation in the National Solidarity Programme, Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, 2004.

20. The ten districts were purposively sampled to meet the following three criteria: they had not been mobilized by NSP before; the security situation was conducive to survey implementation; and they had at least 65 villages. For more see A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme: Hypotheses and Methodology, Kabul: World Bank, 13 April 2008.

21. Villages assigned to the control group received NSP in 2012.

22. The matched-pair cluster randomization procedure used background village characteristics including village size (based on data collected a few years earlier by Afghanistan's Central Statistics Organization) and a set of geographic variables (distance to river, distance to major road, altitude and average slope). The procedure was successful in statistically balancing treatment and control groups across 19 key variables for which data were collected in the baseline survey. The difference between the means of the two groups is always smaller than 6 per cent of the standard deviation. For more see A. Beath, F. Christia, R. Enikolopov and S. Kabuli, Randomized Impact Evaluation of Phase-II of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme (NSP): Estimates of Interim Program Impact from First Follow-Up Survey, Washington, DC: World Bank, 8 July 2010.

23. See here http://www.nsp-ie.org/followups.html for the survey instruments in English, and in the relevant local languages, Dari and Pashto.

24. For the midline male household questionnaire, enumerators sought participation of baseline male household respondents or, in their absence, a relative or cohabitant of the respondent.

25. See here for the full pre-analysis plan that links specific survey questions to indicators and offers detailed specifications of the analysis that were run (at: http://www.nsp-ie.org/toolsanddata/paps/NSP_IE_2FU_PAP_2012_02_07.pdf). This paper present the results of specification from the pre-analysis plan. Appendices IV and V in Beath et al. (n.6 above) present results for an alternative specification with improved statistical power.

26. See Part II, Section VII of Beath et al. (n.6 above) for further discussion of the hypotheses of the study.

27. For the second phase of NSP (2006–10), the PDO was to “lay the foundations for a strengthening of community level governance, and to support community-managed subprojects comprising reconstruction and development that improve access of rural communities to social and productive infrastructure and services”. The key outcome indicators were: (i) to enable “[a]round 21,600 … CDCs across the country [to] avail of basic social and productive infrastructure and other services”; (ii) to achieve “ERRs for community projects [in excess of] 15%”; to ensure that “O&M is in place for the completed projects and that the infrastructure services are use [sic] appropriately by the targeted communities for the purposes intended”; to ensure that “[a]t least 60% of CDCs [are] functioning to address critical development needs as identified by villages”; and (iv) to provide for “an increased level of participation of women in the community decision making [sic]” (World Bank [2006], p. 33). Note that the key outcome indicators identified by the program consist mainly of outputs specific to treatment areas and are thus inappropriate for this type of study, which includes control and treatment villages and seeks to explore impacts on general outcomes.” World Bank (2006). Technical Annex for a Proposed Grant of SDR 81.2 Million (US$120 Million Equivalent) to the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan for a Second Emergency National Solidarity Project (NSPII). Washington, DC: World Bank (November 10).

28. This section summarizes Part III of Beath et al. (see n.6 above).

29. Given the uncertainty over the future schedule of NSP block grant disbursement, villagers are unlikely to expect the implementation of further NSP-funded projects once the village's block grant allotment is completed.

30. A. Beath, F. Christia, G. Egorov, & R. Enikolopov, Electoral Rules and the Quality of Politicians: Theory and Evidence from a Field Experiment, Working Paper: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2013; A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, ‘Direct Democracy and Resource Allocation: Experimental Evidence from Afghanistan’ [MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2011-6], SSRN, 26 Apr. 2015; A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, ‘Do Elected Councils Improve Governance?: Experimental Evidence on Local Institutions in Afghanistan’ [MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2013-24], SSRN, 15 Sept. 2013.

31. Beath et al. Electoral Rules and the Quality of Politicians (see n.29 above); A. Beath, F. Christia, & R. Enikolopov, Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme – Hypotheses and Methodology, Kabul: World Bank, 13 Apr. 2008a; A. Beath, F. Christia, & R. Enikolopov, Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme – Report on Election Monitoring, Kabul: World Bank, 23 July 2008b; A. Beath, F. Christia, & R. Enikolopov, Randomized Impact Evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme: Baseline Survey Report, Kabul: World Bank, 11 Dec. 2008c; A. Beath, F. Christia, & R. Enikolopov, Randomized Impact Evaluation of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme – Report on Monitoring of Sub-Project Selection, Kabul: World Bank, 17 Jan. 2009; A. Beath, F. Christia, & R. Enikolopov, ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme – Village Benefit Distribution Analysis. Pre-Analysis Plan: Hypotheses, Methodology and Specifications’. EGAP Registered Design, 17 Jan. 2012a; A. Beath, F. Christia, & R. Enikolopov, ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme – Final Report. Pre-Analysis Plan: Hypotheses, Methodology and Specifications’. EGAP Registered Design, 14 Feb. 2012b; A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, ‘Empowering Women through Development Aid: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Afghanistan’, American Political Science Review, Vol.107, No.3, 2013, pp.540–57; A. Beath, F. Christia and R. Enikolopov, ‘Winning Hearts and Minds through Development: Experimental Evidence from Afghanistan’ [MIT Political Science Department Research Paper No. 2011-14], SSRN, 13 Apr. 2012; Beath et al. Direct Democracy and Resource Allocation (see n.29 above); Beath et al. Do Elected Councils Improve Governance? (see n.29 above); A. Beath, F. Christia, R. Enikolopov, & S. Kabuli, ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme: Sub-Treatment Interventions – Analysis of the Impact of Election Type on Electoral Outcomes’, Kabul: World Bank, 2 July 2009a; A. Beath, F. Christia, R. Enikolopov, & S. Kabuli, ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of the National Solidarity Programme: Sub-Treatment Interventions – Analysis of the Impact on Project Selection Outcomes of Variation in Selection Procedure and Election Types’, Kabul: World Bank, 2 July 2009b; A. Beath, F. Christia, R. Enikolopov, & S. Kabuli, (2010). ‘Randomized Impact Evaluation of Phase-II of Afghanistan's National Solidarity Programme (NSP) - Estimates of Interim Program Impact from First Follow-Up Survey’, Washington, DC: World Bank, 8 July 2010.