Abstract

Facilitadores Judiciales is a programme run by the Organization of the American States and the Nicaraguan judiciary. In 2010, facilitators were recruited and trained in many but not all urban municipalities. This presented an opportunity for a natural experiment to assess the impact of the programme. In our theoretical framework the impact is related to improved access to justice which is one of the prerequisites for peace and development. Before and after quantitative and qualitative studies were conducted in intervention and control areas. The quantitative results show confirmation of some of the hypothesized effects of the programme. Other effects are indicated by the numerous in-depth interviews but are not substantiated by hard data. In the communities where facilitators were introduced the people report fewer legal problems. The facilitators are decreasing the costs of justice. Achieving amicable solutions and promotion of peace and social cohesion is another example of the programme's impact.

Introduction

In this article we analyse the impact of a paralegal programme in Nicaragua. Facilitadores Judiciales (FJ) is a programme initiated at the end of the 1990s by the Organization of the American States (OAS) and the Nicaraguan Supreme Court. Community-based facilitators help the people from the local communities to solve their disputes and legal problems. Initially the FJ programme ran in rural and isolated communities of Nicaragua. In 2010, the programme gradually expanded to urban communities. This stage of the programme presented an opportunity to study the intervention and compare its effects to communities where no facilitators were active.

The article aims to identify and quantify the impact of the FJ programme and its relevance for security and peace building in Nicaragua. Two cross-sectional surveys were conducted – before and after the intervention. Urban communities with and without facilitators were randomly selected for the study. In addition, a series of interviews with facilitators, beneficiaries and important stakeholders were conducted after the intervention in order to get a deeper insight of the results of the programme. Next, the article analyses the ‘drivers’ for success of the FJ programme. The approach has been widely acclaimed for its positive effect on access to justice.Footnote1 In the past couple of years it has been already replicated in other countries from the region. Our interest is to identify and discuss the critical areas that determine the success of the FJ and similar programmes.

Conflicts, Access to Justice and Peace

People need justice protection for their most valuable interests and relationships.Footnote2 Security of land and tenure rights is a prototypical example of individual or communal problems that can lead to violent conflicts. Past violations of human rights is another example that requires processes and procedures to restore damages, allocate liability and achieve reconciliation. When there are no accessible and fair disputes resolution mechanisms conflicts can escalate from individual into communal level and from communal to social level.Footnote3 It should be noted that both formal and informal justice mechanisms play an important role in the fair resolution of existing disputes.Footnote4 The state is the formal duty bearer responsible for ensuring the right of access to justice. Informal providers of justice – such as the facilitators – are also expected to provide a certain level of accessibility and fairness. The negative effect of the lack of justice is clear: unresolved conflicts inhibit development, nurture violence and other human rights abusesFootnote5 and lead to political exclusion of whole groups.Footnote6

In their daily lives the people experience many problems which necessitate some form of formal or informal dispute resolution process.Footnote7 Many of these problems might not be considered by the involved parties as legal or justiciable. Regardless of how people perceive their justice needs the lack of accessible and fair remedies leads to conflict escalation and a growing feeling of injustice and disenfranchisement. Many justice problems are interconnected and do not occur randomly. Studies show that various disputes trigger each other or happen in clusters.Footnote8 Perceived lack of justice in the everyday life leads to violent self-help solutions and radicalization.

Access to justice here refers to the objective availability of rules and procedures to resolve disagreements and grievances and the subjective belief that these rules and procedures are fair and accessible.Footnote9 The FJ programme is one of the many mechanisms that aim to facilitate access to justice (see below for the specific mechanisms in ‘Theory of the Intervention'). Wider and effective access to justice leads to fewer escalated disputes, a general sense of fairness and rule of law and more peaceful communities. Providing justice is one of the conditions to break the cycles of violence and insecurity.Footnote10 Nicaragua is in the process of coping with political violence but the peace in the country has been challenged by inequality and many disputes and disagreements for which the people cannot find fair resolution. In this study we question whether and how the FJ programme creates a legitimate institution for improving access to justice. To answer the question we explore how the beneficiaries experience the programme and how it affects their abilities to achieve fair resolutions to their legal problems. Our central assumption is that if the intervention improves access to justice it will contribute to the country's peaceful development.

The Facilitadores Judiciales Programme

The FJ programme is based on the ideal that everyone deserves justice, and couples with the recognition that, in practice, the state has not always been able to meet the demand for justice with fair, practical and affordable solutions. Importantly, rather than being based on an imported model, the programme has been inspired by local pre-existing practices of judicial outreach by way of making use of communal social structures and leaders. The value of the programme can be seen in the way it helps ordinary people to find solutions to their justice needs in a simple, quick and affordable manner; and when this is not possible, in how it helps people to take other steps towards solving their justice-related problems.

The programme ought to be understood against the background of the judiciary's sub-optimal performance. Although Nicaragua is not currently considered a fragile state according to standard classifications, its relevance to work on peace building and conflict prevention is underscored by its history of civil war and political instability. In the 2014 Rule of Law index in 2014 Nicaragua has been ranked 85th out of 99 countries and two before the last when compared to other countries from Latin America and the Caribbean.Footnote11 The processes of conflict prevention cannot be viewed without analysing the mechanisms for solving various types of disputes, disagreements and grievances. In an ideal world the combination of formal and informal dispute resolution processes provides accessible, fair and predictable options for dealing with disputes. Nicaragua's judicial system, however, has been said to suffer from political interference and widespread corruption.Footnote12 Even more important for understanding the significance of the programme is the assessment that the judiciary does not adequately cover the entire country, and demonstrates considerable functional deficiencies. Against this background, the use of ‘proxies’ located at community level, or, otherwise put, the possibility to avail communities of easily accessible authority to help with problems locally and quickly, bears a significant potential for increasing access to justice, thus improving people's lives.

The FJ programme commenced officially in 1998 as a pilot project of the OAS. It should also be noted that the Nicaraguan Supreme Court actively partnered in the project from the very beginning. Initially, the FJ built upon a long lasting practice taking place in the north of Nicaragua where local judges used community leaders as proxies in remote and isolated villages.Footnote13 In the first years of implementation (1998–2001) the FJ was piloted in remote rural and post-conflict municipalities.Footnote14 At the time it was named Facilitadores Judiciales Rurales, indicating its focus on rural communities. By 2001 there were 76 FJs working in 18 municipalities. In the second programme stage (2001–07), the OAS and the Nicaraguan Supreme Court co-operated to expand the programme further in rural and underdeveloped municipalities. During that stage the FJ programme was extended to various indigenous areas of Nicaragua. As a result, many local indigenous judges (Wihta) were integrated as FJs. In 2007, there were 1,260 active FJs in 120 municipalities.

Since 2008, the Nicaraguan Supreme Court has taken a more active stance towards integrating the FJ programme into the national justice system. A National Service of Facilitators (Servicio Nacional de Facilitadores) was established with the aim of taking over the programme and funding it from the judicial budget. This policy course implies that FJs will be introduced in all municipalities of Nicaragua – rural, suburban and urban. Another corollary of the policy is that the FJs must be further integrated into the overall functioning of the judiciary.

As of May 2013, 2,762 FJs have been appointed, of which 36 per cent are women, 28 per cent work in urban areas and 4 per cent are indigenous. The programme is now present in all 17 provinces and 2 autonomous regions of Nicaragua, in all 153 municipios (notably also in all municipal capitals) in urban, suburban and rural areas.

How FJ Works

The facilitators are members of their local communities (barrios) who work on a voluntary basis in the interests of justice and the justice needs of the community. The particular barrios can range from a few hundred inhabitants to barrios of 2,000–3,000. The urban barrios where the study took place have on average a population of about 2,500 inhabitants. FJs are elected by their communities during a meeting at which everyone present can nominate a facilitator. The facilitators must be aged at least 18 and be respected members of the community. They should have independent sources of income since they cannot charge fees for their services. There is a minimum number of citizens that need to be present at the election meeting for the vote to be valid. After the elections the local judge serving the region appoints the successful applicant as a facilitator. Next, the appointed FJs take part in practical training performed by local judges. Introduction to mediation and mediation skills are core components of the training programme. According to the programme rules there are at least four training sessions per year. In practice training is contingent on the available resources.

Essentially, FJs act as paralegals/mediators within their own communities. They typically work from their own homes, or at the scene of the dispute. They help the members of the community to solve their disputes and grievances, whether directly (facilitate immediate solution) or indirectly (information, advice, accompanying, etc.).Footnote15 Internal OAS documentsFootnote16 suggest that the most frequent disputes referred to FJs are: money-related problems, disputes between neighbours, damages to crops and insults. They are barred from mediating certain kinds of cases, for example, severe criminal cases involving violence (including domestic violence), civil cases that entail change in property registration and family cases that concern custody.

The FJs perform primarily the following activities:

Increase awareness and provide information: FJs increase legal awareness by informing members of the community regarding laws, rights and institutions, collectively (during seminars and gathering) and individually (per specific needs that arise before them).

Provide legal education: Beyond merely providing information, (some) FJs provide normative/moral guidance as to what people should do (or not) to avoid trouble with the law and to live harmoniously.

Facilitate an immediate solution: Where possible, FJs encourage parties to reach an amicable solution through dialogue, and they solve incoming disputes through mediation and conciliation. When successful, they draft brief agreements or minutes that record the agreed solution.

Advise and refer: In cases that are not susceptible to immediate solution, or when the mediation attempt is unsuccessful, FJs advise victims/parties regarding their rights, options and possible redress. They refer these people to the authorities capable of solving the problem and might also provide a (semi-formal) referral to court.

Accompany: When possible, FJs not only explain to people where to go and what to do, they actually accompany them to the right place (legal aid bureau/ministry/court, etc.) and support them in the process.

Liaise with local courts and assist judges: FJs also partially function as the long arm of the courts, so members of the local communities can go to them to submit documents, instead of travelling long distances to file complaints and deposit documents on their own. FJs also directly support judges by performing tasks such as delivering summons, finding witnesses, measuring land, performing inspections and making appointments on behalf of the judge.

Theory of the Intervention

According to its designers, the FJ programme should have a far-reaching impact on access to justice, societal conflict and administrative costs in the judicial sector, in particular in:Footnote17

Prevention of (escalation of) problems: FJs are expected to prevent the occurrence of problems through their presence as a recognized conflict resolution mechanism. Where FJs are present, it is anticipated that individuals will be more likely to honour agreements as they are aware of acting ‘in the shadow of the law’. In addition, the presence of FJs as a local, cheap, easily accessible (both culturally and geographically) conflict resolution resource should prevent the escalation of problems beyond their initial inception.

More amicable solutions: The use of mediation approaches in the resolution of problems, and the greater involvement of the parties in the development of the solution to the problem should result in more amicable solutions being reached in FJ areas compared to those who continue to use the pre-existing adjudicative systems.

Reduced costs: The FJ service is provided to individuals free of charge in their own communities. This represents many cost savings to individuals, in terms of both financial costs (court fees, lawyer fees, transport costs), time costs (travel time, court appearances, visits to lawyers) and emotional and stress costs (caused by extended time-frames, adversarial court procedures, greater expense at risk). Accordingly, the FJ programme is expected to impact favourably on these costs.

Increased empowerment: Through the awareness raising activities of the FJs, and their easy availability as a source of information, we anticipate that the FJ programme will increase knowledge of laws, rights and access to justice in their communities. In turn it is expected that this increase in knowledge in these areas will improve the empowerment level of individuals, as they understand what their rights are, what the relevant laws are and how they can go about solving their problems. Accordingly, the FJ programme is expected to increase levels of empowerment in their communities.

Methodology

In 2009, a decision was taken to expand the FJ programme from rural to urban communities in Nicaragua. At the time, the available project funding allowed for only partial coverage of the urban sites. This provided a rare opportunity for a natural experiment in which some urban communities benefited from FJs whereas others did not.Footnote18 The decision on where to implement the FJ programme was based on organizational capabilities and the sites were selected at random. However, we are not aware of all factors which have influenced the decisions of the OAS regarding in which urban municipalities and barrios to expand the FJ programme. The study uses a pre- and post-intervention design, with both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. The quantitative data were collected through pre- and post-intervention surveys that used structured interviews administered to a sample of the population. The qualitative method consisted of semi-structured qualitative interviews conducted with a broad range of project stakeholders. The pre-intervention measurements were conducted in the period February–March 2010, while the post-intervention measurements took place in February–March 2013.

Quantitative Measures

Given the detailed nature of the analysis conducted for this study, only a subset of FJ-participant communities could be included. The data presented here thus do not describe the full range of communities served, but are in our assessment suggestive of broader trends that could be explored more fully in future work. Field sites were selected as follows: from the list of new urban municipalities targeted by the OAS to receive FJ services in more than four barrios, two municipalities were selected using the randomization function in Microsoft Excel. Municipalities with more than four targeted barrios were selected to ensure that community-level effects would be present. The two selected municipalities were Cuidad Sandino and Jinotega. Within each municipality, two barrios were selected, using the same randomization procedure.

A third municipality, Juigalpa, was also selected to act as a source of control information. This municipality was selected on the basis of similarity in population, socio-economic development and access to justice, to the intervention municipalities, from those municipalities where no FJ activities were scheduled to take place. This assessment has been made largely based on the analysis of the local OAS staff. Again, two barrios were selected in this municipality.

To collect the sample, random methods were combined with some quota sampling as follows.Footnote19 Initially, each barrio was divided into four equal clusters. Within each cluster, households were randomly selected by taking each n-th house starting from a randomly selected starting point. Within each household the adult (aged over 16) who had the earliest birthday was asked to provide responses to the questionnaire. However, in order to facilitate comparison and generalization, it was attempted to match the gender distribution of the entire Nicaraguan population (50:50). This meant that at the end of each block of questionnaires, specifically men or women would be selected in order to fulfil this quota. However, it was not possible to reach a 50:50 split, and both the pre- and post-intervention surveys had gender ratios of approximately 60:40 female–male.

The same barrios and sampling methods (with the exception of a differently selected random starting point) were used in the pre- and post-intervention surveys. Pre-intervention quantitative interviews were carried out by students of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua and of post-intervention by students of the Universidad Centroamericana in Managua. The questionnaire asked for information about previous experience with legal problems, perceived incidence of legal problems and legal empowerment. Copies of the pre- and post-questionnaires are available upon request from Martin Gramatikov.

To identify the impact of the FJ programme we employ the difference in differences (DiD) methodology. In essence, comparison of control sites pre- and post-intervention tells us what might have been expected to occur in the intervention sites if the FJ programme was not implemented. Comparing this difference to the difference found in intervention sites tells us the impact that the FJ programme had. Initial comparison of treatment and control sites helps us to identify pre-existing differences not attributable to the treatment. Post-intervention comparison is then made to assess the impact of the treatment, taking into account these pre-existing differences. In that way we can isolate the expected effects of the FJ programme from the trends that took place outside the programme and equally impact intervention and control sites. DiD, however, has its limitations. First, it does not tell us how comparable the control and intervention communities are in relation to factors beyond the comparison. Second, it does not account for spill-over effects. Third, DiD assumes that the intervention is uniformly applied across the intervention sites, and so variations that occur due to variations in implementation are not accounted for in a DiD analysis.

Analysis

Incidence of Problems

To get a better idea about people's actual experiences with the law we asked the respondents if, in the past 12 months, they had personally encountered situations that might require legal information or assistance. It is important to note that respondents were asked about problem situations, that is, dispute with a neighbour, land dispute, purchasing defective goods and so on. All of these situations could have legal but also non-legal solutions. Our interest was to find out what strategies people undertake to solve the problems, what level of fairness they receive and what costs the resolutions incur. From there we wanted to see if there is an impact of the FJ programme on experience with and resolution of problems.

In conformity with the findings reported above, the sites where facilitators were to be introduced saw in 2010 a higher proportion of people who report one or more problems which are difficult to resolve (see ). The difference is substantial, and statistically significant (Chi squareFootnote20 = 6.77, d.f. = 1, p = .009). After the FJs became active, there are still more problems reported in the intervention sites than in the control sites, but the difference is much smaller. Moreover, the difference within the intervention/control condition is not statistically significant anymore.

TABLE 1 OCCURENCE OF LEGAL PROBLEMS

To test further the hypotheses of DiD, we ran a multivariate binary logistics regression model with experience of problems as dependent variable and pre–post intervention-control conditions and their interaction as independent predictor. This model suggests that only the pre–post condition decreases significantly the likelihood (Wald = 42.535,Footnote21 d.f. = 1, p < .00) that a problem will be experienced. The interaction effect is not significant which means that we cannot be reasonably certain that the relative decline of reported problems in the communities with FJs is not due to sampling or measurement errors.

When people experience legal issues they need formal or informal justice mechanisms to resolve their problems. The resolution rate (the percentage of reported problems that have been resolved) is often used as an indicator of the impact of interventions designed to improve access to justice. The results show that the resolution rate for the intervention sites increases from 2010 to 2013 almost 10 per cent whereas in the control sites there is an increase of 3 per cent (see ). We should warn, however, that at this level of the analysis the numbers are small. This also affects our ability to test the hypothesized DiD effect using multivariate models.

TABLE 2 PROPORTION OF RESOLVED CONFLICTS

It could be that the work of the FJs directly or indirectly affects the resolution of legal problems. The FJs may step in actively in disputes and resolve the issues between the parties. Or, the FJs may assist people to find and use justice mechanisms, which otherwise would be unknown or unreachable. Another indirect contribution may be that FJs assist judges, the police or the government officials and make their interventions more effective.

Perceived Incidence of Problems

The respondents from both control and intervention barrios were also asked in the pre- and post-intervention surveys to assess the perceived level of conflict. Two types of conflict situations were addressed; communal and intra-family conflicts. Examples of the former category are disputes between neighbours, unruly behaviour and excessive noise. Intra-family problems refer to situations like divorce, separation, disputes over maintenance and custody rights and inheritance. Two types of questions were asked: (1) what the perceived prevalence of problems is, and (2) whether these problems have increased or decreased over the last three years. Both these issues were rated on a five-point scale. Low values indicate that the respondents report few problems on the first type of questions or a decrease in problems on the latter. High values have the opposite meaning: high prevalence of problems and an increase of these particular types of problems.

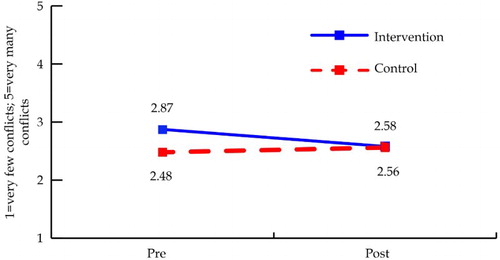

Compared to the control sites, the number of communal problems reported developed in a positive direction in communities where FJs have been deployed (see ). The two control communities (barrios Pedro Joaquin Chamorro and Nuevo Amanecer in municipality Juigalpa) started from fewer reported communal problems (Mpre-control = 2.48;Footnote22 Mpre-intervention = 2.87Footnote23). In 2013, the number of problems reported in communities with and without FJs were almost identical (Mpost-control = 2.56; Mpost-intervention = 2.58). The multivariate model is statistically significant (F = 7.98,Footnote24 d.f. = 3, p < .00) showing significant effects of the intervention condition as well as the interaction between the intervention and pre–post conditions. There is no statistically significant main effect of the pre–post condition.

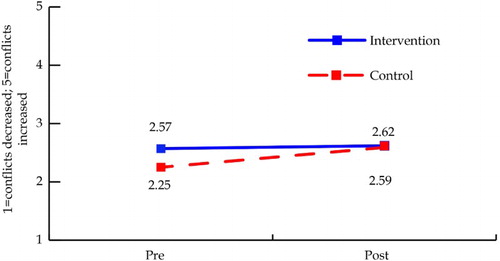

Next, we asked the respondents about trends: whether the number of communal problems has increased or decreased (see ). In 2010 the respondents from the control sites were more likely to have a positive view on the trend in their community (Mpre-control = 2.25; Mpre-intervention = 2.57). After the intervention both control and intervention sides report almost the same trends (Mpost-control = 2.59; Mpost-intervention = 2.62). Thus, the sites with FJs deployed improved their views on conflict-level trends compared to control sites. The multivariate model (F = 6.64,Footnote25 d.f. = 3, p < .00) shows that the main effects of the intervention and pre–post condition as well as their interactions are statistically significant.

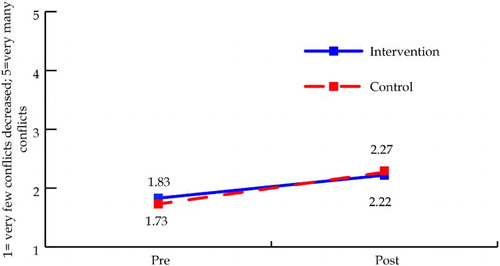

A similar pattern has been found in relation to intra-family conflicts (see ). All communities were rather positive about the number of these conflicts in 2010 (Mpre-control = 1.73; Mpre-intervention = 1.83). Three years later in both the intervention and control sites people thought there were more family problems (Mpost-control = 1.73; Mpost-intervention = 1.83). The intervention barrios did slightly better although in the multivariate model (F = 5.79,Footnote26 d.f. = 3, p = .001) the interaction effect is not statistically significant and we cannot be certain that the difference in difference is not due to sampling or measurement error.

The perceived trends in intra-family problems do not reveal significant differences between the sites with FJs and without them. However, the difference between scores in 2010 and 2013 is less negative in intervention sites than in control sites.

Part of these positive changes can be attributed to the presence of the FJs. Their mission is to help people handle justice problems through dispute resolution or referral to justice institutions. Clearly many beneficiaries shared during the in-depth interviews that the FJs helped them by offering more understandable justice processes. Because of the assistance they received, the beneficiaries feel more empowered in their interactions with the authorities. It is relatively easy to see the impact that the FJ programme has on the people who directly benefit from the services of the FJs.

It is more difficult to explain the relationship between the intervention and its impact at community level. In fact, only one respondent to the post-survey in the intervention barrios said that a problem was referred to a facilitator. The FJ programme does not reach people randomly. There is a significant amount of self-selection effect that takes place. Only those who need them and are particularly determined to solve their legal problems ever go to see a FJ. The FJ intervention is not a massive programme which pro-actively reaches out directly to a significant part of the community. How is it possible then to affect the perceived and experienced legal problems at a community level?

First, the fact that the FJs are there to help with disputes and problems might be encouraging people to think that if a problem with legal implications occurs, there will be someone available to help them solve it. We did not find significant impact of the intervention on the perceived legal empowerment but the relationship might be less straightforward. Second, with their work the facilitators prevent problems from escalating. This means every time they resolve an issue there are fewer complications. Research provides ample evidence that unresolved legal problems trigger other problems.Footnote27 For instance, unfair dismissal might lead to housing and debt problems, family breakdown and so on. Thus the accessibility to the justice mechanism decreases the overall number of problems in the community. Third, the FJs support justice institutions, and notably the courts, to provide better services. This might be increasing the feeling of protection and security among the communities where the FJ programme is operational.

More Amicable Solutions

One of the key aspects of mediated agreements is that they are acceptable to both parties, and consequently, have a better chance of being upheld without the use of any compulsion. One of the ways in which this can be examined is by looking at how the fairness of solutions was rated by individuals who used non-adjudication dispute resolution mechanisms. Although this question was asked to all respondents in the pre- and post-surveys, there were not enough people who used alternative dispute resolution. Therefore we cannot test this hypothesis.

There is qualitative evidence, however, that the programme has an impact on enabling more amicable solutions in processes that are based on communication, characterized by being ‘friendly’ or ‘pleasant’ with minimal quarrels among the parties, and leading to an agreed (rather than imposed) outcome, which also has a greater potential to be stable. The interviews with FJs and others make it quite clear that a friendly negotiated solution that can last in the long run is the result the FJs aim for when they attempt to mediate:

We act and we give them a bit of a coaching talk and we tell them: ‘Look, you need to be in peace with your neighbour that is what a neighbour is there for, neighbours are not there to be fighting with, they are there to have a plentiful life, to live in peace.' (FJ 4)

We have a number of examples of beneficiaries that have solved their problems through amicable processes and solutions that have developed a sense of ‘communitarian consciousness’:

He [the FJ] called us for a meeting for us to reach an agreement. He said it was not necessary to go so far, that we are there for each other, that we are comrades, that we are neighbours, that we live here in the community, that we should look after one another. (Beneficiary 5)

[The FJ] made him [the other party] see that I am a person who does not look for trouble with anybody [ … ]. So he said that this should be solved amicably. (Beneficiary 10)

Another beneficiary went out of her way to describe the FJ's pleasant manner of handling the matter:

He is efficient. He does not make anyone his enemy. He has no enemies because he does everything with love, with affection, saying: ‘We are friends, we know each other, we are neighbours, let's not do this again, let's change to support each other, we are here for that.' That is how he does it. (Beneficiary 10)

Reduced Costs

In Nicaragua, as in many other places, the costs of justice constitute a major hurdle for many people. One of the assumptions of the FJ programme is that it reduces the costs of access to justice for beneficiaries. The FJs perform their role on a voluntary basis. The beneficiaries receive services; information, advice, representation or actual resolution of disputes free of charge. Additionally, whereas distance can constitute an obstacle for accessing justice, the services of the FJs (except for accompanying people to other justice sector institutions) are provided on site; right there in the neighbourhood. In this way, the beneficiaries save travel costs and travel time (which constitutes opportunity costs) that they would have otherwise incurred.

In the survey, the clients were asked to identify one or more important barriers to resolution of their conflicts. We found no effect of the presence of FJs on costs being mentioned as an important barrier to dispute resolution, or the time spent on resolving disputes. It may be that the presence of facilitators reduces costs or time spent, but that is still seen as an important barrier to solving problems.

What we did find is that the individuals who experienced a problem more often report costs as one of the most important barriers to resolution in 2013 compared to 2010 (Wald = 11.390, p = .001). This indicates that either the costs of solving a problem increased, or ability to pay decreased. Our data do not indicate which of these possibilities reflects reality, however, as the interview data indicate the costs of access to justice in Nicaragua can be high. In 2013, respondents were less likely to report time spent on resolving disputes as such a barrier to resolution (Wald = 22.749, p < .001). These effects are replicated across both the intervention and control sites, and so may well be due to a third, external, factor.

In the majority of the in-depth interviews, the issue of the costs of justice also arose. Despite the quantitative data showing no change in the incidence of costs being an important barrier to access to justice, in the interviews, facilitators, judges and members of civil society, all saw costs as a serious issue:

Interviewer: What obstacles do people encounter while accessing justice when they have a problem?

Interviewee: Well, justice is expensive. Even if there is a constitutional decree stating that justice should be free you know that if there is no money nothing can be done here. If there is no money, there is no justice. If you want to file a claim, present charges, you need to go to a lawyer for him to draft the claim, or the necessary documents, and that has a price. (Civil society 2)

How am I going to pay for a lawyer? They earn excessively and sometimes they don't even handle the case for their client. Right? (Beneficiary 6)

Facilitators, too, are well aware of this difficulty:

Well, access to justice, at least in Nicaragua, is expensive. While going to a lawyer, sometimes, the first thing they ask for is money, they say: ‘You will give me 3,000 pesos.' That is only the initial fee afterwards they charge more, and more, and more, and more, and more and there is nothing to do about it. Sometimes for an ID card: ‘You will pay me 3,500 to see how we could help you to obtain this ID card.' The same for a birth certificate. So it is very expensive. (FJ 1)

Moreover, they clearly realize that one of their advantages in the eyes of the beneficiaries is the reduced (or even eliminated) cost, and they tend to assume this is indeed a major impact of their presence in their communities as alternative paths to justice:

They [beneficiaries of the FJ programme] will not spend money on the bus ticket, they won't waste their time and the authorities won't lose their time and energy on matters that could end up in a trial and you know how much a trial costs at the courthouse! In criminal matters, the offended party looks for a lawyer and the person sued also needs to look for a lawyer. All those are expenses for the family. [ … ] Just by getting on the bus to go to the courthouse they are already losing money. They stop working for a day; they can't do their domestic tasks. (FJ 5)

The FJ programme aims to make justice more affordable for the people who need it. Due to budgetary restrictions both pre- and post-surveys had limited sample sizes. As a consequence, the number of respondents who reported a problem and the incurred costs of dispute resolution were not sufficient to detect effects even if there are such in the general population. Therefore this impact has been corroborated exclusively from qualitative data.

FJs are volunteers and do not collect fees from their clients. They are also located in the communities and thus are easy to reach; the physical distance is minimal. Because of the specifics of the programme, FJs often work from their homes which means that they are reachable even when the official institutions are closed for business. FJs work in a very informal way, which inevitably affects the amount of stress that people experience when they use their services. All these aspects of the FJ programme make it clear how the beneficiaries save monetary, opportunity and stress costs. It should be noted that perhaps when compared with the rural FJs, the cost reductions in the urban areas are more modest. In rural areas people are significantly more isolated from legal services. Therefore in the villages the FJs are perhaps saving significantly more costs for the people who need justice. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the programme is saving different types of costs of justice for the beneficiaries from urban areas.

Increased Legal Empowerment

Legal empowerment here refers to the ability of individuals to solve their legal problems. This was evaluated using the perspectives of individuals in qualitative interviews as well as measuring Subjective Legal Empowerment (SLE).Footnote28 SLE measures the perceived ability to solve legal problems; that is how able and confident respondents feel to solve potential future conflicts. It is anticipated that due to the presence of FJs people may feel protected and more able to use legal mechanisms to solve their problems, and thus more able and confident that they will be able to solve future problems.

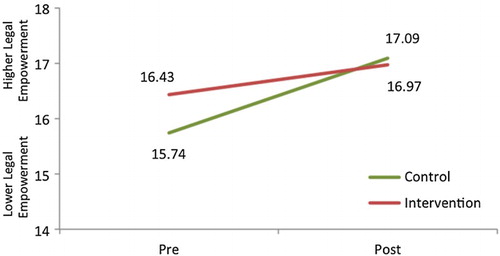

Overall, SLE ratings increased between the pre- and post-measures. However, SLE ratings improved more in control communities than they did in FJ communities (see ). This is counter to the anticipated effect, but can be explained by two different hypotheses. First, other legal empowerment activities were taking place in the control communities, and these produced the large change that is seen. We do not have a comprehensive index of all empowerment programmes taking place in Nicaragua at this time, but it is not expected that there would be any significantly different activities taking place in the control sites and not in the FJ sites. The second hypothesis is that the lower starting level of SLE in the control communities gave room for a much larger rise over time. This second hypothesis is discussed further below.

When we dig deeper into the specific legal domain (for instance domestic violence, employment problems, etc.) we find that the overall increase is present in the majority of domains for respondents in the intervention sites and for all domains in the control sites. We also find, using DiD analysis, that although there is a significant effect of the pre–post condition, there is no effect of intervention condition on SLE ratings.Footnote29 Accordingly, we conclude that the FJ intervention had no significant impact upon legal empowerment that was detected in the quantitative data.

What is also clear is that the intervention sites started with a significantly higher level of SLE overall than the control sites (t = 1.993,Footnote30 d.f. = 478, p = .047), but ended with non-significantly different levels (t = –0.423, d.f. = 998, p = .672). This indicates that the control groups actually ‘caught up’ on a prior deficit in relation to legal empowerment compared to intervention sites. shows the differences in mean pre- and post-scores for both the intervention and control sites. In two domains (domestic violence and neighbour problems), there was no significant change in the intervention sites scores. In these domains, the control group showed a significant increase in SLE in relation to neighbour disputes, but no significant change in relation to domestic violence.

TABLE 3 DIFFERENCES IN SLE RATINGS

On the one hand, the control group has a significant improvement in SLE scores in four of the five domains, as well as overall. The intervention group, on the other hand, has a significant improvement in SLE scores in only three of the five domains, although they also have a significantly higher overall SLE rating.

These results are difficult to interpret. The initially high starting point for SLE ratings in the intervention compared to control groups, although difficult to explain, may well account for the smaller improvement of FJ sites in comparison with control sites. As mentioned, there have been many activities in Nicaragua aimed at improving legal empowerment, and it is possible that these other interventions were more focused on those areas with no FJ presence (indeed, possibly because there was no FJ presence). However, it is not possible in this article to examine in depth the relationships between different situations or conditions and the variations in legal empowerment demonstrated here.

Simple Processes

Simplicity is a key distinguishing feature of how FJs are supposed to solve problems at the community level. Their presence can be expected to make it easier to begin a process that will bring resolution to the existing justice need, and to make this process more straightforward and understandable. Before the appointment of FJs, people would typically perceive the path to justice as too difficult and complicated.

Consider for example the following quote from a criminal law judge, when he was explaining the importance of FJs by way of describing the difficulties that people typically have when facilitators are not available: ‘[People] think: “I will go to Court but if the judge is busy she cannot help me”’ (Criminal judge 3). Or: ‘I go to the police. I file an accusation and the police officer will tell me that I have to bring I don't know how many witnesses and if the investigator is busy … Do you get my point?’ (Criminal judge 3). The risk the interviewed judge is referring to is that people with a justice need might feel defeated before even starting the procedure, just because things seem difficult or overly complicated, not worthy of action. Even worse is the situation of people who simply do not know what action to take, as everything seems complicated and discouraging. Complexity of processes is a serious barrier to justice and the FJs reduce it for their constituencies.

The availability of FJs improved the situation of such people, who can now access justice much more easily, among other things because it is free, but it is also simple to go to a FJ and ask for help. For someone with a problem, setting things in motion has become as simple as making a phone call to the facilitator or going to his or her house. There is no need to file a complaint formally, submit evidence or summon witnesses. Moreover, mediation as carried out by FJs is a rather simple process: The FJ invites the other party, this is typically followed by just one meeting to resolve the dispute, the results of which, if successful, are recorded in a very short and simple written agreement.

When asked about the impact of FJs, beneficiaries are more inclined to mention things like the reduced costs of justice, and the enhanced amicability, but their answers certainly give support to the view that they also feel a difference in terms of the simplicity of the paths to justice, and that they do appreciate the fact that getting on a path to justice, as well as actually travelling it, have really become simpler.

Gender Equality

Finally, an objective of the FJ programme is to increase the levels of gender equality in the intervention groups. It is difficult to measure precisely gender equality. However, one aspect which can be looked at is the rates of violence against women. Respondents were asked how many of every 10 women they knew, did they think had experienced violence in the last 12 months. shows the significant model that is found with the pre–post and intervention conditions. This shows us that there has been a significant drop in the perceived prevalence of violence against women between the pre- and post-time periods in both intervention and control locations, from a mean of 25 in every 100 women, to just 18 in every 100 women.

TABLE 4 PERCEIVED EXPERIENCE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Given that the intervention condition and interaction are not significant in this model, it is likely that this drop is due to an external factor. In particular, in June 2012, the highly publicized Comprehensive Law against Violence towards Women (Law 779) was passed in Nicaragua.Footnote31 This law is very well recognized and is regarded as being effective in reducing violence against women.

The impact that the FJ's programme has had on gender equality cannot be immediately inferred from the qualitative interviews. However, what can be seen is that FJs have adopted an educational role seeking a change in mentality and social patterns towards violence against women, an important aspect to achieve gender equality. Their constant efforts increase awareness on women's rights issues and educate society. FJ are speaking up, explaining laws and actively joining sensitization campaigns.

Conclusions

A sober and realistic picture emerges from the impact assessment of the expansion of the FJ programme into urban communities of Nicaragua. Our study finds that the presence of facilitators decreases the perceived level of intra-community conflicts. In the urban communities where facilitators were active the people experienced a sharper decrease of serious legal problems. The pre- and post-cross-sectional surveys, however, did not identify a couple of impacts that were expected. Qualitative interviews with facilitators, beneficiaries, police officers and local authorities provide less robust indications of impact. Decreased costs of obtaining justice, easier navigation through the justice system and increased self-confidence in own abilities to deal with problems are the most important programme benefits. We interpret the fact that qualitative measures detect more effects in three ways: (1) the FJ programme needs longer time to get recognized and experienced in the communities; (2) the skills, abilities and energies of the individual facilitators vary and thus affect the value that their clients receive; and (3) access to justice interventions are not massive programmes; they target people who experience serious and difficult to resolve problems. Examples of such issues are land disputes, domestic violence and aggravated family problems.

The introduction of facilitators decreases the number of problems and empowers people to resolve their disagreements in a fair manner. This means that fewer problems escalate into cycles of violence. More problems are being resolved through some sort of a fair process and the outcomes are considered as just. Considering the trigger effects of the justice problems we can hypothesize that the intervention is preventing other problems from occurring. Respondents from the intervention areas are more confident that the level of communal disputes decreases over time. Here it should be noted that these changes do not happen in the short run. It takes time for access to justice interventions to achieve their intended impacts. The improvements that can be attributed to the FJ programme are not radical but also not negligible. With small steps the accessibility of justice in the intervention communities has been improved. This means less escalated disputes, less violence and greater sense of justice, security and peace.

There is a large body of evidence regarding the ability for the FJ programme to be scaled up beyond the borders of Nicaragua and even Latin America. However, there are characteristics that we believe may have a significant impact on existing and future follow-up programmes. The institutional arrangement affects the success and sustainability of the FJ programme. The experience from Nicaragua provides ample evidence about the crucial importance of a genuine embracement by the judiciary. Organizational and personal commitment to the values of the FJ programme is a key factor for success. Moreover, the experience shows that judges alone cannot make it a success; involvement of all relevant stakeholders is needed. It is critical that the programme is seen as beneficial by a broad range of actors – local authorities, police officers, bar members, judges and community leaders.

Furthermore, the success of the facilitators is largely dependent on their ability to gain trust from the local community and use social authority to intervene in people's justice needs. Their work is more effective in smaller communities, where the bonds between the individuals and community are stronger. Various barriers to justice make the presence of FJs in remote and isolated communities more valuable for their beneficiaries. Scaling up of the programme should consider careful selection and sequencing of intervention sites. The Nicaraguan experience shows how important it is that the programme commences in places where it is needed the most.

Lastly, further research should look deeper into the drivers for success. Understanding how such factors work and interact with the surrounding social and legal culture is crucial for the replication and scaling up of every programme. In that respect some of the identified drivers of success of the FJ programme in Nicaragua provide a salient indication of how to implement similar programmes in other countries.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Martin Gramatikov is head of Measuring and Evaluation at HiiL Innovating Justice. He holds an LLM and Ph.D. degree in political science from the University of Sofia. Martin Gramatikov researched extensively the justice needs and experience as experienced by the individuals.

Maurits Barendrecht is a full professor in private law and conflict systems at Tilburg University. He is the research director of HiiL Innovating Justice and author of many books and articles in the field of access to justice and dispute resolution.

Margot Kokke is a trainee judge at the District Court of The Hague. Previously she worked as a lawyer at De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek and was a research fellow at the Tilburg University Law School.

Robert Porter is a researcher at Tilburg University and at HiiL Innovating Justice. He has academic background in both psychology and law and wrote a Ph.D. thesis on legal empowerment.

Morly Frishman studied law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the University of Amsterdam. His work experience includes diverse positions such as a justice sector advisor at HiiL Innovating Justice and legal clerk at the International Criminal Court.

Andrea Morales studied law at the Pontificia Universidad Católica in Equador, the Hanzehogeschool in Groningen, The Netherlands and Leiden University, The Netherlands.

Notes

1. Margot Kokke and Pedro Vuskovic, ‘Legal Empowerment of the Poor in Nicaragua’, SSRN, 2010 (at: ssrn.com/abstract=1674020), p.4.

2. Maurits Barendrecht, Martin Gramatikov, et al., Towards Basic Justice Care for Everyone: Challenges and Promising Approaches, The Hague: Hague Institute for the Internationalisation of Law, 2012, p.141; Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor, Making the Law Work for Everyone, New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2008.

3. World Bank, ‘The World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development’, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2011.

4. Kieran McEvoy, ‘Beyond Legalism: Towards a Thicker Understanding of Transitional Justice’, Journal of Law and Society, Vol.34, No.4, 2007, pp.411–40.

5. Lars-Erik Cederman, Andreas Wimmer, et al., ‘Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel? New Data and Analysis’, World Politics, Vol.62, No.1, 2010, pp.87–119.

6. World Bank (see n.3 above); Beqiraj Julinda and Lawrence McNamara, The Rule of Law and Access to Justice in the Post-2015 Development Agenda: Moving Forward but Stepping Back, London: Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law, 2014.

7. Hazel Genn, Paths to Justice: What People Do and Think about Going to Law?, Oxford: Hart Publishing, 1999; Pascoe Pleasence et al., ‘Causes of Action: First Findings of the LSRC Periodic Survey’, Journal of Law and Society, Vol.30, No.1, 2003, pp.11–30; Ben van Velthoven and Marijke ter Voert, Paths to Justice in the Netherlands: Looking for Signs of Social Exclusion’, Leiden: Leiden University, 2004; Martin Gramatikov, Justiciable Events in Bulgaria, Sofia: Open Society Institute, 2010.

8. Ab Currie, The Legal Problems of Everyday Life: The Nature, Extent and Consequences of Justiciable Problems Experienced by Canadians, Ontario: Department of Justice, Canada, 2010: Pascoe Pleasence et al., ‘Multiple Justiciable Problems: Common Clusters and Their Social and Demographic Indicators’, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vol.1, No.2, 2004, pp.301–29.

9. Martin Gramatikov, ‘Methodological Challenges in Measuring Cost and Quality of Access to Justice’, Working Paper No.005/2008, Tilburg: Tilburg University Legal Studies, 2007.

10. World Bank (see n.3 above).

11. See data.worldjusticeproject.org/#/index/NIC, accessed 1 Jun. 2015.

12. See Bertelsmann Transformation Index report (at: http://bti-project.org/index/), accessed 1 Jun. 2015; see also country-specific information provided by the United States Department of State (at: travel.state.gov/travel/cis_pa_tw/cis/cis_985.html), accessed 1 Oct. 2013.

13. Kokke and Vuskovic (see n.1 above).

14. Margot Kokke, Marian Van Dijk, et al., ‘Facilitadores Judiciales Nicaragua Impact Evaluation: Baseline Assessment’, Tilburg: Tilburg Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies of Civil Law and Conflict Resolution Systems, 2010, pp.1–71 (on file with the authors).

15. For more information see www.oas.org/es/sla/facilitadores_judiciales_una_respuesta.asp, accessed 21 Aug. 2013.

16. Kokke and Vuskovic (see n.1 above).

17. See www.oas.org/es/sla/facilitadores_judiciales.asp, accessed 13 Aug. 2013.

18. See, for thorough discussion of natural and quasi-experimental designs and the threats to their internal and external validity, Bruce D. Meyer, ‘Natural and Quasi-Experiments in Economics’, Journal of Business and Economics Statistics, Vol.13, No.2, 1994, pp.151–61. See also www.wider.unu.edu/research/current-programme/en_GB/Experimental-Methods-Study-Goverment-Performance/, accessed 4 Oct. 2013.

19. Emmanuel Skoufias, ‘Introduction to Impact Evaluation: Methods and Examples’, World Bank, 12 Aug. 2013 (at: siteresources.worldbank.org/INTISPMA/Resources/Training-Events-and-Materials/050310_IE_Methods.pdf); Christopher Blattman, Alexandra Hartman and Robert Blair, ‘Building Institutions at the Micro-Level: Results from a Field Experiment in Property Dispute and Conflict Resolution’, 4 Oct. 2013 (at: www.american.edu/cas/economics/news/upload/Blattman-paper.pdf).

20. Goodness of fit test; d.f. refers to degrees of freedom; p refers to the significance level.

21. Wald test is used to determine how significant an explanatory variable in a model is.

22. Mean of the control group during pre-intervention study.

23. Mean of the intervention group during pre-intervention study.

24. Muli-variate linear regression.

25. Kokke and Vuskovic (see n.1 above).

26. Ibid.

27. Currie (see n.8 above); Pleasence et al. (see n.7 above).

28. Martin Gramatikov and Robert B. Porter, ‘Yes, I Can: Subjective Legal Empowerment’, Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, Vol.18, No.2, 2011, pp.169–99.

29. When the pre–post condition and intervention/control conditions were entered as independent variables, with SLE ratings as dependent variables, the pre–post condition of the measure was the only significant predictor in relation to overall SLE (p < .000), property (p = .002), employment (p < .000) and violent crime (p < .000), while neither of the independent variables were predictors in relation to domestic violence, and only the interaction between the pre–post condition and the intervention/control condition was a significant predictor in relation to neighbour disputes.

30. Test for difference of means of independent samples.

31. See www.asamblea.gob.ni/Informacion%20Legislativa, accessed 15 Aug. 2013.