ABSTRACT

In the past two decades, regional organizations and coalitions of states have deployed more peace operations than the UN. Yet most quantitative studies of peacekeeping effectiveness focus on UN peacekeeping exclusively, a decision owed to data availability more than to theories about the differential impact of UN and non-UN missions. As a result, we know little about the effectiveness of non-UN peacekeeping in mitigating violence. In this paper, we introduce and analyse monthly data on the approximate number of troops, police, and observers in both UN and non-UN peacekeeping operations between 1993 and 2016. Using these data, we show that when accounting for mission size and composition, UN and regional peacekeeping operations are equally effective in mitigating violence against civilians by governments, but only UN troops and police curb civilian targeting by non-state actors. We offer some theoretical reflections on these findings, but the main contribution of the article is the novel dataset on non-UN peacekeeping strength and personnel composition to overcome the near-exclusive focus on UN missions in the scholarship on peacekeeping effectiveness.

Introduction

Partnership peacekeeping involving both UN and non-UN actors has become a prominent feature of discussions about the future of peacekeeping within the UN system – a new paradigm even.Footnote1 Echoing these discussions at the political level, a number of studies have highlighted the empirical trend towards a proliferation of regional missions in the peacekeeping sphere.Footnote2 Yet even as the number of peacekeeping actors has increased, we know very little about the ability of these new actors to mitigate violence in civil conflicts. Our knowledge of the effectiveness of peacekeeping stems almost exclusively from studies on UN operations. These studies have demonstrated that UN peacekeeping, and especially the deployment of sizable contingents of armed troops, is an effective tool to lower violence and keep the peace once obtained.Footnote3 Can we expect the same empirical patterns from non-UN peacekeeping, or is there something particular about UN peacekeepers that make them more suitable for managing civil conflicts?

To address this question, we introduce and explore monthly data on the approximate size and composition of both UN and non-UN peacekeeping operations. The scholarship on UN peacekeeping has acknowledged that missions vary greatly in their capacity and constitution, and that mission strength and personnel composition can change drastically over the course of a year within the same mission, therefore requiring temporally disaggregated data when examining the impact these missions have on conflict dynamics. Until now, however, studies of non-UN peacekeeping have lacked comparable detailed data on the varying size of troop, police, and observer deployments and instead relied on dummy variables for peacekeeping presence/absence or simple categorizations of mission type.Footnote4 As a result, we do not know whether we can expect the same impact from non-UN peacekeeping operations as from UN peacekeeping. Moreover, by examining UN peacekeeping in isolation, without accounting for the presence of non-UN actors in the same conflicts (or in the comparison cases that are classified as ‘without’ peacekeeping even though a regional peacekeeping force may be present), existing findings may in fact be biased.

Our dataset reports the approximate monthly number of troops, police, and observers deployed by the UN, regional organizations, and coalitions of states to civil conflicts globally between 1993 and 2016. These data are compiled and consolidated from annual numbers provided by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).Footnote5 We then use linear interpolation to generate the monthly estimates. Our validation of this procedure for the UN part of our dataset (where we can compare the interpolated values against true monthly data) shows a high correlation with the true values. We thereby conclude that the interpolated data on non-UN missions are suitable for global analyses of peacekeeping in the absence of true monthly data.

Using these new data, we show that UN missions are on average much larger than non-UN missions. They are also more diverse in terms of personnel deployed, whereas especially the larger non-UN missions are more military-focused. These differences in size and personnel composition may offer an explanation for previous findings – based on binary indicators for mission presence – that only or primarily UN missions mitigate violence.Footnote6 To address this question, we systematically compare the impact of the size of UN and regional peacekeeping operations on violence against civilians by governments and rebel groups, respectively. We show that a greater number of troops and police in both UN and regional missions are associated with lower levels of violence by governments. However, when it comes to rebel one-sided violence, only UN troops and police are associated with fewer civilian fatalities; regional peacekeepers have no observable effect. The results are similar in the full sample and in a matched sample that we use to reduce the problem of selection bias.

In what follows we first provide a brief overview over the state of the art on research on UN versus non-UN peacekeeping, before we present the methodology for compiling the new dataset. We then offer some descriptive trends and patterns, and finally use the new data to assess the impact of UN versus non-UN peacekeeping on civil war violence. Last, we reflect on possible theoretical explanations for this difference.

State of the Art

Research on the effectiveness of peacekeeping, which since the ‘third wave’ of peacekeeping research has been predominantly quantitative-comparative,Footnote7 has focused primarily on UN missions, for which temporally and spatially disaggregated data is available. This body of research has found that UN peacekeeping is effective in promoting peace and security through several different pathways.Footnote8 First, UN missions are on average effective in keeping the peace once obtained.Footnote9 Second, recent research suggests that UN peacekeepers shorten episodes of conflict and violence.Footnote10 Third, even when conflicts are ongoing, there is evidence that UN missions mitigate the levels of violence in these wars, both in terms of battle deaths and violence against civilians.Footnote11 Many of these results are conditional in that not all peacekeeping personnel has the same impact; most positive impacts of peacekeeping on lowering levels of violence is associated with missions that have a high number of armed troops.

At this stage, there is no basis for judging whether these findings can be extended to peacekeeping missions by regional organizations or coalitions of states. Scholars have pointed out that non-UN missions likely differ from UN missions in important ways and that conclusions drawn about UN operations are not necessarily applicable to those organized by other actors.Footnote12 Especially for regional operations, arguments have been made in both directions, namely that particularities of regional missions should make them more or conversely less effective in dealing with violence. We briefly review three sets of arguments that are commonly made in this regard in the literature on non-UN or, more specifically regional, peacekeeping.

A first set of arguments on the relative effectiveness of UN and non-UN peacekeeping centres on the cultural and political closeness of regional operations. Because peacekeepers from the same region may have a better understanding of a conflict’s root causes, may speak the same language, or live in similar cultural and/or political contexts, they may be more effective in dealing with violence and communicating with the conflict parties.Footnote13 Conflict parties may also be more willing to cooperate with regional peacekeepers, whom they do not see as outsiders intervening in their own affairs to the same extent as they would see a UN mission.Footnote14 The flip-side of this coin is that conflict parties may actually regard regional peacekeepers as less neutral and assume vested interests by regional hegemons to be behind an intervention.Footnote15 In either case, Heldt cautions against giving too much weight to these regional homogeneity arguments because they likely overstate the homogeneity of ‘regions’ and the extent of local knowledge and understanding among neighbours.Footnote16

A second set of arguments revolves around the efficiency of deployment and the behaviour of actors once on the ground. It has been suggested that non-UN actors can deploy more rapidly than the UN for reasons of geographic proximity and because they are not bogged down in bureaucratic processes to the same extent as the UN.Footnote17 Once on the ground, regional peace operations are said to be less risk-averse and occasionally deploy to areas where the UN would not go because of the UN’s more strict requirements for deployment.Footnote18 Factors such as speedy deployment and risk tolerance could make non-UN operations more effective at bringing down ongoing conflict violence. At the same time, rapid deployment does not guarantee effectiveness in dealing with ongoing violence. Likewise, a more robust or even offensive posture of a mission could also bring peacekeepers into conflict with the warring parties and lead to more fighting and/or civilian harm.Footnote19

The third set of arguments relates to the relative capacities of UN and non-UN missions. The UN has vast experience in conducting peace operations and has continuously adapted its organizational structures and processes to deal with the demands of an ever-changing security landscape. Regional organizations, on the other hand, are often said to lack not only the experience, equipment, and training but also the budget and mission support structures to effectively conduct large-scale peacekeeping operations.Footnote20 While these capacity arguments may not apply to all non-UN peacekeeping actors alike (think NATO or US-led coalitions of states), it is relatively undisputed that there generally is a capacity difference between the UN and most other peacekeeping actors. Unlike the more contradictory arguments above, these capacity arguments lead to a clear expectation that UN missions should be more effective in bringing down conflict violence than non-UN missions.

Yet systematic empirical studies of the effectiveness of non-UN peace operations are scarce. There are case studies on individual non-UN missions that offer detailed accounts of particular operations and sometimes of their achievements and failings,Footnote21 but such case studies lack a counterfactual of what would have happened if no mission had been present, or if a UN mission could have achieved more (or less). There is also considerable literature on the various different organizations that now conduct peacekeeping missions, but rarely with a systematic focus on comparing the relative effectiveness of missions by different actors.Footnote22 Most studies that compare UN to non-UN missions instead have peacekeeping as the dependent variable and study whether and why countries prefer to support or contribute to UN or non-UN operations.Footnote23

Those studies that have compared the effectiveness of UN and non-UN operations (though some just as a control variable) study diverse outcomes and are dated compared to the more recent studies on the UN, but the general tenet is that there is either no difference in the effectiveness of UN and non-UN missions,Footnote24 or that only or primarily UN missions mitigate violence.Footnote25 The most comprehensive of these is a study by Sambanis and Schulhofer-Wohl in 2007.Footnote26 Noting a lack of theoretical arguments on why there should be a difference between organizations, they start from the assumption that all types of peace operations should have a positive effect if they have sufficient capacities to respond to the challenges of the conflict context. They hence expect no difference between UN and non-UN missions (which they note are not necessarily natural categories), but their empirical analysis still finds that the UN has been more successful in keeping the peace than other organizations.

It is important to note that all the above studies have – with the exception of Sambanis and Schulhofer-Wohl who categorize different mission types or mandates – based their findings on binary variables of peacekeeping presence and absence. Research has hence not been able to control for differing capacities or personnel compositions of UN and non-UN peacekeeping operations that could explain eventual differences in effectiveness. This is due to a lack of detailed data on non-UN missions in an accessible format. Scholars of UN peacekeeping have access to monthly data on the amount of troops, police, and observers deployed to any mission, disaggregated by contributing countries if desired.Footnote27 There is even data on the subnational location of peacekeeping bases.Footnote28 Available datasets on non-UN peace operations contain no such time-varying information. Datasets by MullenbachFootnote29 or Jetschke and Schlipphak,Footnote30 for instance, have information on the presence, start and end dates, mandates, and purposes of both UN and non-UN missions. While they do include the size of these missions in terms of personnel deployed, this information does not change over the course of a mission.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) offers the most detailed information on the number of troops, police, and observers deployed in non-UN (and UN) missions.Footnote31 However, two things have held scholars back from making full use of the SIPRI data. The first is that this data is on an annual level of aggregation, while most peacekeeping scholars wish to use monthly data to study the impact of peacekeeping on fast-changing dynamics of violence. The second is that while the SIPRI data is available online from 2000 onwards, data for the 1990s need to be pulled from tables in the printed yearbooks. The dataset we present in this study is based on the SIPRI data but takes care of both these issues.

Data on UN and Non-UN Peacekeepers

The dataset we use in this paper offers information on the approximate monthly number of peacekeeping troops, police, and observers – both UN and non-UN – deployed to civil conflicts globally between 1993 and 2016.Footnote32 While the contribution of the dataset is the data on non-UN missions that are comparable to existing UN data, we provide data on both types using the same methodology for generating monthly estimates to ensure comparability. We have compiled this data from SIPRI Yearbooks and the Peacekeeping Database, which offer these numbers annually.Footnote33 We then linearly interpolate between known data points (usually in December each year and in the last mission-month) to arrive at monthly personnel levels for each mission. We also extrapolate from the first available data point to the beginning of missions. While this may seem like a crude procedure, it works well for two reasons.

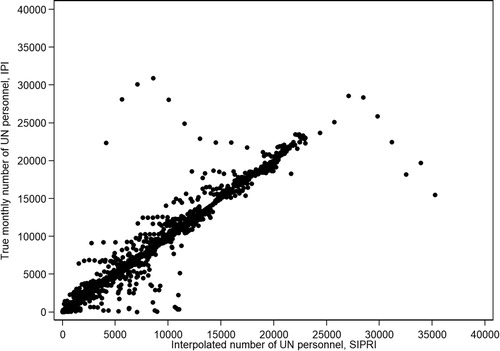

First, the most plausible theoretical assumption is that increases or decreases in deployment levels are gradual. While we can expect some missions that build up quickly to increase their presence in waves, most personnel changes are likely to be more incremental. Second, we show empirically that a linear interpolation proxies the monthly personnel levels very well. For UN missions, which make up almost half of our peacekeeping data, we have true monthly data to compare to from the International Peace Institute (IPI).Footnote34 As shows, the correlation between the interpolated and true monthly overall personnel numbers (given the presence of a UN mission) is very high with 0.97.Footnote35

The extreme outliers concern only two missions. In Bosnia in 1995, the interpolated numbers are much lower than the true monthly numbers from IPI. That is because interpolation assumes a smooth withdrawal of UNPROFOR in the last mission year, whereas IPI records a reduction from more than 20,000–2,000 in the last two months. In reality, the majority of UNPROFOR units was not actually withdrawn, but transferred to the NATO IFOR mission, hence neither version of the data reflects the reality on the ground fully.Footnote36 The opposite case in which the interpolated numbers are much higher than the real numbers concern Somalia in 1993. This is due to the nature of the extrapolation procedure: If only two data points exist for a mission, and the later point reports lower numbers than the first, then extrapolation assumes that the mission started with even higher numbers than recorded in the first data point. However, this is not a common problem in the data.

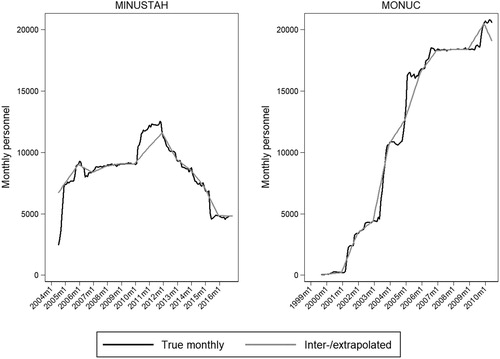

shows a comparison of the true and interpolated monthly data for two cases, MINUSTAH in Haiti, and MONUC in the DRC. This illustrates how close the interpolation generally is to the true monthly values, but it also shows what it misses. For MONUC, interpolation misses the stepwise increases. There is no good interpolation method that can deal with this, as these steps will happen in most missions, but in different intervals and at different times.Footnote37 For MINUSTAH, the linear interpolation seems to miss a peak in 2010, but here the problem is not with the interpolation, but the fact that the SIPRI and IPI numbers disagree. What the MINUSTAH graph does illustrate, however, is a large gap between the true monthly numbers and the extrapolated numbers at the beginning of the mission. Generally, the interpolated observations of our data are much closer to the true monthly data than the observations for which we extrapolated from the first observed data point to the beginning of the mission.

Extrapolation is tricky because not all missions start in the same way. Some missions start at zero personnel and deploy quickly, others start at zero and deploy slowly, again others are follow-on or rehatted missions that take over some or all personnel from previous missions. We thus offer our monthly data on UN and non-UN peacekeeping in two versions: One version in which we only interpolate, and do not extrapolate to the beginning of missions. Here, users have to accept that roughly 10% of monthly observations are missing, and that they are systematically missing at the beginning of peacekeeping operations. In the second version, we extrapolate to the beginning of missions, which renders a complete dataset, but one in which the gap between the true and interpolated values is likely larger for the extrapolated sections.

Even with these caveats, we conclude that when faced with the choice of not using data on non-UN missions because they are not readily available in a monthly format, and using an interpolated version, the latter is a better choice. It is also a better choice than the most basic alternative way of using annual numbers in monthly analyses, which would be to use the end-of-the year count of personnel for all months of the respective year.Footnote38 This is true at least if one is interested in testing general relationships across cases, where smaller measurement errors have less of an impact.Footnote39 Moreover, in a peacekeeping data discussion, van der Lijn and Smit write that although monthly data is crucial as mission strength can change a lot during the year, many – especially non-UN missions – already have difficulties in providing annual, let alone monthly, data.Footnote40 Therefore, using interpolated data is the best available option for now.

The peacekeeping missions included in the dataset are all peace operations listed by SIPRI that also fulfil a more narrow definition of peacekeeping by Bellamy & Williams.Footnote41 SIPRI defines peacekeeping as

operations that are conducted under the authority of the UN and operations conducted by regional organizations or by ad hoc coalitions of states that were sanctioned by the UN or authorized by a UN Security Council resolution, with the stated intention to (a) serve as an instrument to facilitate the implementation of peace agreements already in place, (b) support a peace process, or (c) assist conflict prevention and/or peace-building efforts.Footnote42

The dataset only includes missions that are deployed during an ongoing intra-state conflict as defined by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP),Footnote46 or during any time following a UCDP intra-state conflict that was ever ongoing between 1989 and 2016 (postwar years). This means that we exclude peace operations that were deployed in inter-state wars; missions outside contexts that ever had a civil conflict (such as the peacekeeping missions in Albania in the late 1990s); and preventative deployments such as UNPREDEP in Macedonia, that had already left by the time the conflict started.

In the data, we distinguish between UN, regional, and international missions. Missions are defined as regional missions if they are either run by a regional organization in their own region, or by an ad-hoc coalition of states exclusively or with a large majority from the region. Regions are defined very coarsely as Europe, America, Africa, MENA, and Asia/Oceania. International missions are thus missions run by regional organizations outside their region (such as the EU in Africa or NATO in Afghanistan) or coalitions of states from multiple regions. Regional and international missions can be combined into a non-UN category. The dataset distinguishes them primarily for the reason that many arguments on non-UN peacekeeping actually refer to regional peacekeeping. The separation provides users of the data with some flexibility. If they are more interested in the distinction between UN and non-UN missions, they combine regional and international missions; if they are more interested in whether peacekeeping by ‘neighbors’ differs from peacekeeping by outside actors, they combine UN and international missions, and study them separately from regional ones.

An important caveat is that from 2015 onwards (for the last two years of data contained in the current version), SIPRI does not distinguish between troops and observers, but combines both personnel categories into a ‘military’ category.Footnote47 For users wanting to use data for the whole time period, thus combining data before and after 2015, we suggest creating a military category combining troops and observer numbers for the entire time period. In our own analyses, we restrict the sample to 1993–2014 to be able to differentiate between troops and observers.

Descriptive Trends and Patterns

Our peacekeeping data contain 121 missions in 52 conflicts, covering 36 countries. 51 of these missions are UN missions, 47 are regional missions, and 23 are international.Footnote48 In the following, we offer descriptive statistics of these data, in particular concerning differences in the size and personnel composition of UN and non-UN missions. These shed light on the validity of some claims that have been made regarding differences in UN and non-UN peacekeeping.

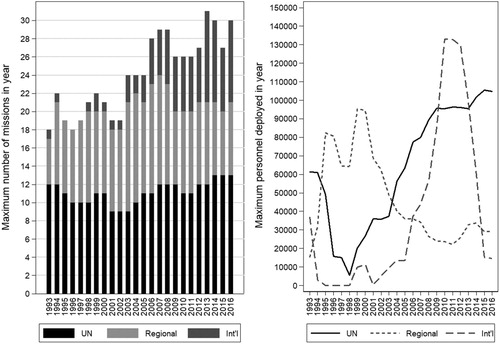

There have been multiple claims of a proliferation of non-UN peacekeeping since the end of the Cold War, going as far as to suggest that non-UN peace operations now account for the majority of missions globally.Footnote49 We can verify this trend with our data. (left) shows that while the number of UN missions has remained fairly stable, the number of regional and international missions has increased. The former increased primarily in the 1990s and early 2000s (when talks of regionalization intesified),Footnote50 the latter since about 2003. The many missions by the EU since the launch of its European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) in 1999 make up a large share of this increase in international missions.Footnote51 Overall, non-UN bodies have deployed more missions than the UN each year since the turn of the millennium. However, if we look beyond the number of missions and instead make use of the more detailed data we now have on the size of these missions (, right), other patterns emerge.

In the past few years, the UN is the dominating peacekeeping force in terms of people on the ground. In fact, if it were not for the massive deployment of personnel in ISAF in Afghanistan (which almost entirely drives the peak in international missions), the UN has been the main contributor of peacekeepers for at least the last ten years. Moreover, UN and regional missions display an inverse relationship. Regional peace operations seem to have taken over the role as the global provider of peacekeepers when the UN underwent a peacekeeping crisis in the 1990s. This bump in regional peacekeeping was driven by a few prominent missions in Europe (former Yugoslavia) and Africa. As Williams writes, regional organizations do fill the some of the gaps left by the selective approach of the UN Security Council.Footnote52 When the UN began to increase its peacekeeping commitments again at the end of the 1990s, the number of peacekeepers deployed by regional organizations declined at the same rate as UN peacekeepers increased.

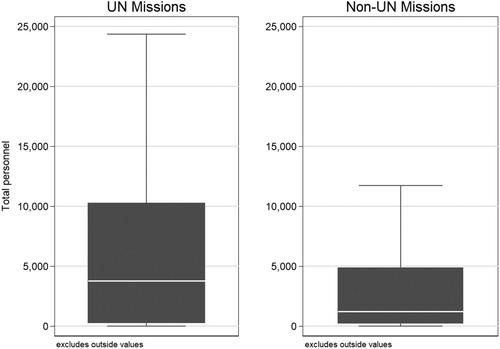

thus qualifies the idea that non-UN missions have replaced the UN as the key player in global peacekeeping. What happened was a proliferation of smaller non-UN missions, but with the exception of a few large NATO operations, the UN has been providing the majority of peacekeepers on the ground for quite a while. This is because UN missions are on average larger than non-UN missions, as illustrated in . The median UN mission has around 3,600 people deployed, whereas the median non-UN mission has a third of that. 75% of UN deployments lie in a range of between 200 and 10,000 persons; the same percentage of non-UN deployments lie in a range of between 200 and 4,600 persons. Hence while the extreme outliers in mission size – which are not in the graph – are mostly non-UN (KFOR in Kosovo, SFOR in Bosnia, ISAF in Afghanistan, and AMISOM in Somalia), the bulk of UN missions has more people on the ground.

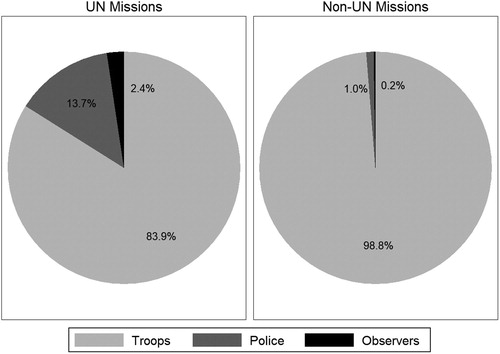

UN missions are not only larger, but also more diverse in terms of personnel deployed. As illustrated in , the average UN mission consists of around 84% troops, 14% police and a bit more than 2% observers, while non-UN missions consist mostly of armed troops, with minimal police and observer numbers. Among the non-UN missions, EU missions are the most diverse. Only a quarter of EU missions have had a military component, and the rest have deployed police, border guards, monitors, judges, and administrators.Footnote53 However, most EU missions are very small and do not have much influence on these personnel statistics. In essence, these numbers show that multidimensional peacekeeping is carried out by the UN, while non-UN missions are more military-focused.

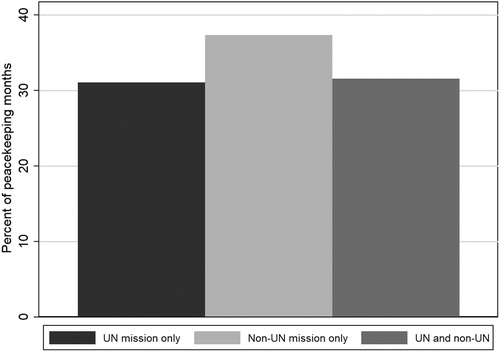

This raises the question of whether there is a certain division of labour, with non-UN missions taking a more military approach and stopping violence, whereas the UN does the peacekeeping, with a multidimensional engagement towards a lasting peace.Footnote54 A division of labour, however, needs peacekeeping partnerships between UN and non-UN organizations. Such partnerships, and the challenges and opportunities they present, have been discussed in a 2015 UN Secretary-General report, in which the engagement of regional partners in peacekeeping alongside UN operations has been described as ‘the norm rather than the exception’.Footnote55 This statement needs to be qualified somewhat. shows that in less than a third of months with peacekeeping, a UN and non-UN mission are on the ground at the same time. Simultaneous partnership peacekeeping has also not become more common over time. On the contrary, the share of joint deployments relative to the overall number of has declined over time.

At the same time, partnership peacekeeping does not have to mean simultaneous deployments: UN and non-UN missions can also deploy in sequence.Footnote56 There are claims that non-UN missions are often deployed as ‘first-responders’ to quickly stabilize a challenging situation before the UN takes over.Footnote57 The reasons would be that they have a greater interest to act quickly, due to their geographical proximity, and that they have a greater ability to act quickly, by not having to go through the UN Security Council and the UN bureaucracy more generally. This first-responder claim bears out in our data. For each conflict, we looked at the first month of an episode of peacekeeping (a continuous presence of peacekeepers in a conflict). In 42 of 60 such peacekeeping ‘onsets’, it was a non-UN mission who responded first (or was the only mission who responded at all). In only 13 instances, a UN mission was deployed first (or exclusively), and in 5 instances, peacekeeping started with a joint presence.

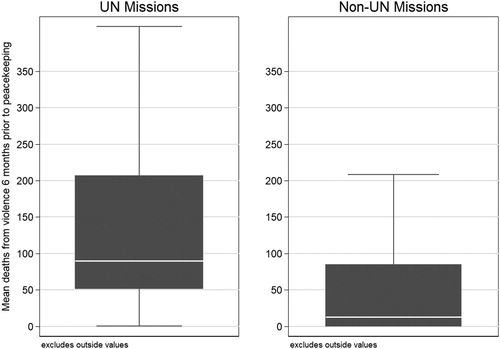

The first responder idea also bears a more substantive connotation, namely that regional and international missions would enter more difficult not yet stabilized situations, before the UN takes over to merely keep the peace. This was the case in Burundi, for instance, where the African Mission to Burundi (AMIB) deployed at a time when the UN was not willing to send a peace operation, as there was continued warfare despite several ceasefire and peace agreements. The UN Operation in Burundi (ONUB) took over a year later when the situation was more stable and a comprehensive peace agreement in place.Footnote58 The context into which different peace operations enter would naturally influence our assessment of how successful they are. If the UN mostly enters into situations where there is a peace to keep, we may think it is successful only because others have already done the difficult work. This, however, does not seem to be the case. As shows, on average the UN actually enters into much more violent contexts than non-UN missions.

We measure violent context as the number of fatalities in battle and one-sided civilian targeting by government and rebels in the 6 months prior to the start of a mission.Footnote59 The median UN mission enters into situations in which there have been an average of close to 100 monthly deaths from such violence in the past 6 months; whereas the median non-UN mission enters into situations in which this number is closer to an average of 10 deaths per month. Supporting this picture of the UN deploying to more difficult contexts is the fact that more than 80% of UN peacekeeping episodes – but only 60% of non-UN peacekeeping – start while conflicts are still active; the rest starts in the post-conflict phase. These response patterns may have consequences for how effectively UN and non-UN missions curb violence once deployed. There is an apparent contradiction here: non-UN missions are frequently the first responders, but UN missions – at least on average – enter into more difficult contexts. This may suggest that the UN is the sole responder in the most difficult and violent contexts, but it may also be a reminder that regional first responder missions in sequential deployments do not always succeed in curbing violence before the UN takes over.

Comparing the Effectiveness of UN and Non-UN Peacekeeping

In this section, we systematically explore the relative violence-reducing performance of UN and regional missions. Due to the heterogeneous category of non-UN missions, we focus on regional peacekeeping here, which corresponds better to arguments in previous research about the potential benefits and drawbacks of non-UN peacekeeping. We do this by using the same approach as a number of published studies have employed to assess the effectiveness of UN peacekeeping in reducing violence against civilians.Footnote60 We begin with a sample of all internal armed conflicts, defined by the UCDP as an armed contestation with a political incompatibility between a state and an organized non-state actor resulting in a minimum of 25 battle-related deaths in a calendar year.Footnote61 We follow these conflicts with monthly observations for their full duration plus the first 24 months of the post-conflict period to enable us to assess the decline of violence in the transition from war to peace. We also show results employing coarsened exact matching to reduce selection bias that is a likely consequence of peacekeeping operations being deployed into specific contexts. This mitigates concerns that the results are primarily driven by factors that distinguish conflicts to which peacekeepers are deployed at all from conflicts that receive no peacekeeping mission.Footnote62 We produce two separate matched samples, one for UN peacekeeping and one for regional peacekeeping (procedure presented below). Our analysis is global and covers the time period 1993–2014.

As a means of assessing effectiveness, we use two different dependent variables: one-sided violence by governments and rebel groups respectively. These variables capture direct and deliberate killings of civilians by the conflict actors. This is intended to reflect the ability of the peacekeeping mission in succeeding with one of its core tasks of protecting civilians from physical violence.Footnote63 This is a count variable, summarizing all the killings from one-sided violence by both governments and rebel groups. Both variables are created using data from the UCDP GED.Footnote64 Given the nature of our dependent variables, and in line with previous studies, we estimate our models with a negative binomial regression.

The main explanatory variables in the analyses are the monthly personnel levels for UN and non-UN peacekeepers, using our new dataset. Building on insights in previous research that troops and police are associated with less violence, while observers are associated with more violence,Footnote65 our main variable of interest is the sum of troops and police. Since we expect the same effect, we collapse these categories to reduce the number of variables and points of comparison. These variables, UN troops and police and regional troops and police, are measured in thousands and lagged one month to ensure temporal order. In addition, we control for the presence of observers by either sender type as separate variables. We include all of these variables in the same models, thus controlling for the other type of peacekeepers.

The models also include a number of relevant control variables.Footnote66 First, we control for the incompatibility of the conflict, measured as a dummy variable for whether the rebels make demands on the government (regarding who should govern and how) as compared to making demands about control over a specific territory. Second, we account for the duration of the conflict. Both these variables are based on the original UCDP conflict dataset.Footnote67 Third, we control for the number of battle deaths in the previous month. Fourth, to account for temporal dependency, we include a dummy variable of whether there was any one-sided violence in the preceding month.Footnote68 These two violence variables are based on the UCDP GED. Last, we control for the logged size of the population in the host country.Footnote69

The results for the full sample are presented in . Model 1 includes only UN peacekeepers. The findings show that UN troops and police have a negative and statistically significant effect, and the presence of UN observers has a positive effect, in line with what we expect based on findings in previous studies. Model 2 includes only regional peacekeepers. The number of troops and police from regional missions has a negative and statistically significant effect. Hence, regional peacekeepers seem equally apt to protect civilians from government violence as UN peacekeepers. In Model 3, where we include both UN and regional peacekeepers, the coefficients from these variables remain very similar. This suggests that estimating the impact of UN and regional peacekeepers separately, without controlling for the presence of the other, is in fact not a major problem.

Table 1. Comparing the effect of UN and regional peacekeeping on one-sided violence.

Models 4–6 mirror the first three, but now with rebel one-sided violence as the dependent variable. Model 4 replicates findings from previous research, showing that larger UN missions in the form of troop and police deployments are associated with fewer civilians killed by rebels. This finding is robust to controlling for regional peacekeepers, as shown by Model 6. Regional peacekeepers, however, do not have an observable effect when it comes to reducing violence by rebel groups. In neither of the two models that include regional peacekeeping do we find a statistically significant effect.

Until now, we have only analysed the full sample, thus potentially showing biased estimates due to the fact that peacekeeping operations are strategically deployed. We deal with this in two ways: first by analysing the effect of the number of troops and police only for those conflicts where a peacekeeping mission is present, and second by using matching to compare peacekeeping and non-peacekeeping cases that are as similar as possible on a number of variables. For the matching procedure, we use coarsened exact matching, where we match on population size, type of conflict, region and the presence of the other peacekeeping actor.Footnote70 We use k-to-k matching, which matches each peacekeeping observation to one without, leaving us with a UN peacekeeping sample of 2,054 observations and a regional peacekeeping sample of 1,480 (out of 11,286 in the full sample).Footnote71 The L1 statistic, which shows the multivariate imbalance in the data, improves from 0.78–0.49 in the UN models, and from 0.83–0.64 in the non-UN models. To account for the remaining imbalance, we include our control variables in the estimation, except those for which we have exact matches.

These results are reported in the form of a coefficient plot, see , that compares the coefficients for the number of UN and regional troops and police for these two reduced samples, as well as the full sample (results from Models 3 and 6 in ). This figure suggests that the results we reported in are robust to both the peacekeeping sample and the matching procedure. For government one-sided violence both UN and regional peacekeepers reduce the level of violence, whereas for rebel one-sided violence we only find an effect by UN peacekeepers. Below, we propose a few theoretical ideas based on the insights from our analyses.

Theoretical Reflections

Are 5000 UN peacekeepers more effective in protecting civilians than 5000 regional peacekeepers? Our findings suggest that this is not necessarily so, but that it depends on the civil war actors with whom the peacekeepers interact. How do we explain this divergence? Recent work has begun elaborating more on the mechanisms by which peacekeeping works in relation to governments and rebel groups, respectively. Fjelde, Hultman and Nilsson, for instance, distinguish between two types of costs that peacekeepers impose on warring actors.Footnote72 Military costs of targeting civilians arise from the risk that peacekeepers may respond to such violence with force against the perpetrating group. Political costs in the form of condemnations or prosecution come from peacekeepers monitoring and reporting abuses. Combined findings from several studies suggest that rebels are more sensitive to military costs, while governments’ propensity to target civilians is influenced more by the political costs of peacekeeping.Footnote73 If rebels are primarily influenced by coercion, peacekeeping effectiveness may hinge not only on the capacity, in terms of the number of troops and police deployed, but also on the capabilities that those peacekeepers have and their mandate. If we take this as a starting point, we can begin theorizing about the different effects of UN and regional peacekeepers.

Several scholars have suggested that capabilities are important for understanding peacekeeping outcomes. The military capabilities available to troops, in the form of training, equipment, and logistical support, dictate the mission’s ability to respond to hostile situations and engage with actors at the tactical level. This type of approach may be more important for the purpose of managing violence by non-state actors, while missions can influence governments through multiple channels including direct collaboration.Footnote74 While capabilities may vary within UN missions,Footnote75 there might be significant differences across UN and regional organizations. One perspective is that regional organizations tend to have weaker capabilities in the form of training, material, and logistics, which means that they cannot be as effective with the same number of peacekeepers as the UN.Footnote76 This has been identified as a key challenge in partnership peacekeeping in a report by the UN Secretary-General. For the AU-led missions in the Central African Republic and Mali, for instance, the report states that ‘the capabilities of the AFISMA and MISCA troops inherited by the successor United Nations missions in terms of equipment and self-sustainment, as well as in terms of training did not match relevant United Nations standards.’Footnote77 The lack of efficient mission support systems, in particular, would explain why 1000 Nigerian troops, to give just one example, could be less effective if deployed within a regional mission than if the same troops were deployed within a UN mission.Footnote78 Mission support boils down to how material and weapons are moved, stored and maintained, how and how quickly troops and be transported and moved, communication capabilities, and even medical aid to peacekeepers.Footnote79

If regional organizations have weaker capabilities, this could explain why they are not as effective in dealing with rebel violence. At the same time, low-income countries have higher incentives to contribute to UN missions, rather than non-UN missions, because of the flat reimbursement systemFootnote80 – and this could result in an overrepresentation of contributors with low military capabilities in UN missions. Most likely, we find both higher and lower capabilities in the non-UN category, depending on the organization. For example, the UN notes that in the case of NATO partnerships, it is actually the UN who profits from NATO expertise in specific areas, such as in dealing with asymmetric threats or in issues regarding improvised explosive devices.Footnote81 Our findings suggest that it would be fruitful to further disaggregate the non-UN mission category, in order to identify the factors that make regional organizations, on average, less able to manage violence by rebel groups.

If these differences in the ability to impose military costs can go some way towards explaining why regional organizations may not as effectively curb civilian targeting by rebels, can the ability to impose political costs explain why both the UN and regional organizations are equally successful in affecting government violence? According to Lise Howard, UN missions are not successful only, or primarily, through coercion, but also through inducement and persuasion.Footnote82 Behind any UN deployment is the consensus of the P5 members that the conflict poses a threat to global or regional peace and security. This may trigger additional efforts by the international community, such as political negotiations, aid, and SSR, which may more effectively target government incentives. However, similar processes could be at play within some of the regional organizations that are dominated or led by a regional hegemon. It is possible that regional strong states can also leverage their political power and economic resources to induce behavioural change in governments who target civilians, while such activities do not provide rebels with any incentives to change their behaviour.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have explored the similarities and differences between UN and non-UN peacekeeping. By providing comparable data on the approximate monthly number of peacekeepers for both UN and non-UN missions, we are able to examine issues relating to their different strengths, compositions, and effects. One question we ask is whether UN and non-UN missions deploy to different contexts. Our descriptive statistics shows some evidence for this. On average, the UN deploys to more violent conflicts than non-UN actors. However, in situations in which the UN and non-UN actors intervene into the same conflict, the non-UN actor is most often the first responder. This article could not explore these differences and temporal dynamics in more detail, but the question of how the effectiveness of earlier missions influences the effectiveness of missions that take over later deserves more research. The effects of these missions also vary. If we take the size of missions into consideration, is there a difference in the effect between UN and non-UN missions? Our findings suggest that there is, at least when it comes to reducing one-sided violence by rebel groups.

This example is a reminder that the category of non-UN peacekeeping is admittedly a rough mix of different types of missions and that the heterogeneity of non-UN missions ought to be further explored. Moreover, whether missions are deployed by the UN or another organization is perhaps not their most distinguishing feature. Certain UN and non-UN missions may be more comparable to each other than missions within these two organizational categories. The data we present here offers the possibility to explore differences between and among UN and non-UN missions further, and hopefully an impetus to overcome the step-motherly treatment of non-UN peacekeeping at least in the quantitative study of peacekeeping effectiveness.

Supplemental Material

Download Stata File (1.2 MB)Supplemental Material

Download Stata File (17.2 MB)Supplemental Material

Download Stata Do-File Editor File (10.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download Stata Do-File Editor File (6.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (200.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (429.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for excellent feedback from participants at the FBA and UNIGE workshop ‘State of the Art? The Future of Peacekeeping Data’ in Genoa, Italy, 18–19 June 2019, and the Peace Science Society Annual Meeting in Austin, Texas, 9–10 November 2018. We also thank Ognjen Gogić for excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Corinne Bara is Assistant Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, with a PhD from ETH Zürich. Her research focuses on the dynamics of violence and strategies of armed actors during and after civil war. Her work has appeared in the European Journal of International Relations, Journal of Conflict Resolution, and Journal of Peace Research.

Lisa Hultman is Associate Professor of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University. Her work focuses primarily on international interventions and violence against civilians. In 2019, her book Peacekeeping in the Midst of War (co-authored with Jacob Kathman and Megan Shannon) was published by Oxford University Press.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 UN Secretary-General, Partnering for Peace, 18.

2 E.g., Jetschke and Schlipphak, “MILINDA”; Williams, “Global and Regional Peacekeepers”; Bellamy and Williams, “Who's Keeping the Peace?”; Bellamy and Williams, “Trends in Peace Operations”; Bures, “Regional Peacekeeping Operations”; Gelot, Legitimacy, Peace Operations.

3 For a good overview, see Di Salvatore and Ruggeri, “Effectiveness of Peacekeeping Operations”.

4 E.g., Heldt, “UN-Led or Non-UN-Led”; Heldt and Wallensteen “Peacekeeping Operations”; Fortna “Does Peacekeeping Keep Peace?”; Fortna, Does Peacekeeping Work?; Sambanis and Schulhofer-Wohl, “Evaluating Multilateral Interventions.”

5 SIPRI Yearbooks; SIPRI, “SIPRI Multilateral Peace Operations Database”.

6 Fortna, “Does Peacekeeping Keep Peace?”; Sambanis and Schulhofer-Wohl, “Evaluating Multilateral Interventions”; Nilsson, “Partial Peace”; Hultman, “Keeping Peace”.

7 Fortna and Howard, “Pitfalls and Prospects”.

8 Hegre, Hultman, and Nygård, “Evaluating the Conflict-Reducing Effect.”

9 Fortna, Does Peacekeeping Work?; Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “United Nations Peacekeeping Dynamics”; Gilligan and Sergenti, “Do UN Interventions Cause Peace?”; Doyle and Sambanis, Making War.

10 Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally” show that peacekeeping operations shorten local episodes of violence, and Kathman and Benson, “Cut Short?”, show that they reduce the time to conflict settlement.

11 Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Civilian Protection in Civil War”; Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Beyond Keeping Peace”; Melander, “Selected to Go”; Bove and Ruggeri, “Kinds of Blue”; Haass and Ansorg, “Better Peacekeepers”; Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection though Presence”.

12 E.g., Diehl, “Behavioural Studies”, 490.

13 Williams, “Global and Regional Peacekeepers,” 127; Heldt, “UN-Led or Non-UN-Led”; von Hippel, “NATO, EU, and Ad Hoc”; Bures, “Regional Peacekeeping Operations”, 92–4; Heldt and Wallensteen, “Peacekeeping Operations.”

14 Diehl, “New Roles”, 541.

15 Heldt, “UN-Led or Non-UN-Led,” 120; Heldt and Wallensteen, “Peacekeeping Operations”.

16 Heldt, “UN-Led or Non-UN-Led,” 121–2.

17 Bellamy and Williams, “Who's Keeping the Peace?,” 195; von Hippel, “NATO, EU, and Ad Hoc,” 211; De Coning, Gelot, and Karlsrud, “Towards an African Model,” 2.

18 Bromley, ”Introducing the UCDP Peacemakers at Risk,” 128; Akpasom, “What Roles,” 115; De Coning, Gelot, and Karlsrud, “Towards an African Model,” 2.

19 Akpasom, “What Roles,” 112; Fjelde, Hultman, and Bromley, “Offsetting Losses,” 621.

20 Williams, “Global and Regional Peacekeepers,” 128; Lotze, “Mission Support.”

21 E.g., Freear and De Coning, “Lessons from the African Union”; Friesendorf and Penksa, “Militarized Law Enforcement,”; Wondemagegnehu and Kebede, “AMISOM.”

22 For instance: Keohane, “Lessons from EU,” on the EU in Europe, Africa, and Asia; De Coning, Gelot, and Karlsrud, “Towards an African Model,” on the AU; Mackinlay and Cross, Regional Peacekeepers, on Russian peacekeeping in its former Soviet territory; Tavares, “The Participation,” on the SADC and ECOWAS; Francis, “Peacekeeping in a Bad Neighbourhood,” on ECOWAS.

23 For instance, Ruffa, “What Colour”; Bove and Elia, “Supplying Peace”; Gaibulloev et al., “Personnel Contributions.”

24 Heldt, “UN-Led or Non-UN-Led”; Heldt and Wallensteen, “Peacekeeping Operations”; Fortna, Does Peacekeeping Work?

25 Fortna, “Does Peacekeeping Keep Peace?”; Nilsson, “Partial Peace”; Hultman, “Keeping Peace.”

26 Sambanis and Schulhofer-Wohl, “Evaluating Multilateral Interventions.”

27 International Peace Institute, “IPI Peacekeeping Database”; Kathman, “United Nations Peacekeeping Personnel.”

28 Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection through Presence”; Ruggeri, Dorussen, and Gizelis, “Winning the Peace Locally.”

29 Mullenbach, “Third-Party Peacekeeping Missions.”

30 Jetschke and Schlipphak, “MILINDA.”

31 SIPRI, “SIPRI Multilateral Peace Operations Database.”

32 The dataset and codebook with more detailed information are in the supplementary materials.

33 SIPRI Yearbooks: https://www.sipri.org/yearbook, SIPRI Multilateral Peace Operations Database: https://www.sipri.org/databases/pko. For a short presentation and discussion of this data, see the section by Jaïr van der Lijn and Timo Smit in Clayton et al., “The Known Knowns.”

34 International Peace Institute, “IPI Peacekeeping Database.” These data are also included in our dataset. We discuss some changes we have made to the IPI data in the Codebook.

35 Graphs with correlations for the individual personnel types (troops, police, observers) are in the Appendix.

36 UN Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General.

37 Besides the interpolated monthly values, the dataset also contains the variables in which only the values given by SIPRI are listed (mostly December and last mission month), and months in between are coded as missing. This allows users to use different interpolation or extrapolation methods if they desire. Our tests have shown that more complex interpolation methods either do not fare much better compared to simple linear interpolation (natural cubic spline interpolation, for instance), or fare better but lose up to a third of observations because more than two observed points are needed (cubic interpolation, for instance).

38 We demonstrate this in the Appendix. The Appendix also offers more descriptive statistics about how the two interpolated versions compare to the true monthly data.

39 If one is primarily interested in describing the development of a particular peacekeeping mission, these interpolated data are more problematic.

40 Van der Lijn and Smits in Clayton et al., “The Known Knowns.”

41 Bellamy and Williams, “Trends in Peace Operations.”

42 SIPRI, “SIPRI Multilateral Peace Operations Database.”

43 Bellamy and Williams, “Trends in Peace Operations.”

44 Unlike Bellamy and Williams, however, we do include pure police missions such as EUPOL as we are specifically interested also in the effect of police. The dataset includes a variable that flags the missions for which we have done that so as to allow the user to exclude those and thus stick to the strict Bellamy & Williams definition of peacekeeping.

45 Bellamy and Williams, “Trends in Peace Operations,” 14.

46 UCDP Armed Conflict Dataset v.17.1 (Gleditsch et al., “Armed Conflict 1946–2001”; Allansson, Melander, and Themnér, “Organized Violence, 1989–2016”).

47 The reason being that for non-UN missions is not always clear whether military personnel would correspond to troops or military observers as defined by the UN (Email Timo Smit, SIPRI, on 24 July 2017).

48 The Appendix contains a map illustrating which countries in conflict have received a mission at all, and whether they received a UN mission, non-UN mission, or both.

49 Diehl, “Behavioural Studies,” 485–6.

50 Bellamy and Williams, “Who’s Keeping the Peace?”; Cottey, “Beyond Humanitarian Intervention”; Griffin, “Retrenchment, Reform and Regionalization.”

51 Keohane, “Lessons from EU Peace Operations.”

52 Williams, “Global and Regional Peacekeepers,” 127.

53 Keohane, “Lessons from EU Peace Operations.”

54 See also Howard, UN Peacekeeping in Civil Wars; Muggah, “Peacekeeping Operations.”

55 UN Secretary-General, Partnering for Peace, 2.

56 UN Secretary-General, Partnering for Peace. This sequential deployment may or may not be intended from the outset. Especially for AU missions there have frequently been expectations but no guarantee that the UN eventually takes over, see Brosig, “The Multi-actor Game,” and De Coning, Gelot, and Karlsrud, “Towards an African Model.”

57 De Coning, Gelot, and Karlsrud, “Towards an African Model,” 1–2; Williams, “Global and Regional Peacekeepers,” 127.

58 Brosig, “The Multi-actor Game,” 332–5, discusses this case in some detail.

59 Data from the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset v19.1 (Sundberg and Melander, “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced”; Högbladh, “UCDP GED Codebook”).

60 E.g., Bove and Ruggeri, “Kinds of Blue”; Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Protection of Civilians in Civil War”; Haass and Ansorg, “Better Peacekeepers”; Beardsley, Cunningham, and White, “Mediation, Peacekeeping.”

61 Högbladh, “UCDP GED Codebook,” 28.

62 Cf. Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Beyond Keeping Peace.”

63 Cf. Diehl and Druckman, Evaluating Peace Operations.

64 Sundberg and Melander, “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced”; Högbladh, “UCDP GED Codebook.”

65 Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Civilian Protection in Civil War.”

66 We include a similar set of control variables as Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Civilian Protection in Civil War,” to enhance comparability.

67 Pettersson and Eck, “Organized Violence, 1989–2017.”

68 The results are very similar if only including a lagged dummy of the dependent variable to account for temporal dependency.

69 Data for population and infant mortality rate from the World Bank, “World Bank Indicators.”

70 Iacus, King, and Porro, “Causal Inference.” The variables are selected based on studies of where peacekeepers are deployed, e.g., Gilligan and Stedman, “Where Do the Peacekeepers Go?”; Mullenbach, “Deciding to Keep Peace.” Our data also show that both UN and regional peacekeeping is more common in conflicts fought over government control, compared to territory. We bin population into small and large, divided by the mean value, and require exact matches on the remaining variables.

71 The alternative is to allow multiple matches per peacekeeping observation. Employing that alternative strategy yields similar results.

72 Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection though Presence,” 107.

73 Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon, “Civilian Protection in Civil War”; Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection though Presence”; Phayal and Prins, “Deploying to Protect.”

74 Cf. Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection through Presence.”

75 Haass and Ansorg, “Better Peacekeepers.”

76 See Lotze, “Mission Support,” for a discussion of this problem in African peacekeeping missions.

77 UN Secretary-General, Partnering for Peace, 8.

78 We thank one anonymous reviewer for raising this important and thought-provoking question, given that several countries deploy troops both to UN and non-UN missions.

79 Lotze, “Mission Support.”

80 Gaibulloev et al., “Personnel Contributions”; Bove and Elia, “Supplying Peace.”

81 UN Secretary-General, Partnering for Peace, 12.

82 Howard, Power in Peacekeeping.

References

- Akpasom, Yvonne. “What Roles for the Civilian and Police Dimensions in African Peace Operations?” In The Future of African Peace Operations – From the Janjaweed to Boko Haram, edited by Cedric de Coning, Linnéa Gelot, and John Karlsrud, 105–119. London: Zed Books, 2016.

- Allansson, Marie, Erik Melander, and Lotta Themnér. “Organized Violence, 1989–2016.” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 4 (2017): 574–87. doi: 10.1177/0022343317718773

- Beardsley, Kyle, David E. Cunningham, and Peter B. White. “Mediation, Peacekeeping, and the Severity of Civil War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63, no. 7 (2019): 1682–709. doi: 10.1177/0022002718817092

- Bellamy, Alex J., and Paul D. Williams. “Who's Keeping the Peace?: Regionalization and Contemporary Peace Operations.” International Security 29, no. 4 (2005): 157–95.

- Bellamy, Alex J., and Paul D. Williams. “Trends in Peace Operations, 1947–2013.” In The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, ed. Joachim Koops, Thierry Tardy, Norrie MacQueen, and Paul D. Williams, 13–42. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Bove, Vincenzo, and Leandro Elia. “Supplying Peace: Participation in and Troop Contribution to Peacekeeping Missions.” Journal of Peace Research 48, no. 6 (2011): 699–714. doi: 10.1177/0022343311418265

- Bove, Vincenzo, and Andrea Ruggeri. “Kinds of Blue: Diversity in UN Peacekeeping Missions and Civilian Protection.” British Journal of Political Science 46, no. 3 (2016): 681–700. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000034

- Bromley, Sara Lindberg. “Introducing the UCDP Peacemakers at Risk Dataset, Sub-Saharan Africa, 1989–2009.” Journal of Peace Research 55, no. 1 (2018): 122–31. doi: 10.1177/0022343317735882

- Brosig, Malte. “The Multi-actor Game of Peacekeeping in Africa.” International Peacekeeping 17, no. 3 (2010): 327–42. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2010.500142

- Bures, Oldrich. “Regional Peacekeeping Operations: Complementing or Undermining the United Nations Security Council?” Global Change, Peace & Security 18, no. 2 (2006): 83–99. doi: 10.1080/14781150600687775

- Clayton, Govinda, J. Kathman, K. Beardsley, T.-I. Gizelis, L. Olsson, V. Bove, A. Ruggeri, R. Zwetsloot, J. van der Lijn, T. Smit, L. Hultman, H. Dorussen, A. Ruggeri, P. F. Diehl, L. Bosco, and C. Goodness. “The Known Knowns and Known Unknowns of Peacekeeping Data.” International Peacekeeping 24, no. 1 (2017): 1–62. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2016.1226768

- Cottey, Andrew. “Beyond Humanitarian Intervention: The New Politics of Peacekeeping and Intervention.” Contemporary Politics 14, no. 4 (2008): 429–46. doi: 10.1080/13569770802519342

- De Coning, Cedric, Linnéa Gelot, and John Karlsrud. “Towards an African Model of Peace Operations.” In The Future of African Peace Operations: From the Janjaweed to Boko Haram, ed. Cedric De Coning, Linnéa Gelot, and John Karlsrud, 1–19. London: Zed Books, 2016.

- Diehl, Paul F. “New Roles for Regional Organizations.” In Leashing the Dogs of War: Conflict Management in a Divided World, ed. Chester A. Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela Aall, 535–52. Washington, DC: USIP Press, 2007.

- Diehl, Paul F. “Behavioural Studies of Peacekeeping Outcomes.” International Peacekeeping 21, no. 4 (2014): 484–91. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2014.946741

- Diehl, Paul F., and Daniel Druckman. Evaluating Peace Operations. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner, 2010.

- Di Salvatore, Jessica, and Andrea Ruggeri. “Effectiveness of Peacekeeping Operations.” In Oxford Encyclopedia of Empirical International Relations. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.586.

- Doyle, Michael W., and Nicholas Sambanis. Making War & Building Peace. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Fjelde, Hanne, Lisa Hultman, and Sara Lindberg Bromley. “Offsetting Losses: Bargaining Power and Rebel Attacks on Peacekeepers.” International Studies Quarterly 60, no. 4 (2016): 611–23. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqw017

- Fjelde, Hanne, Lisa Hultman, and Desirée Nilsson. “Protection Through Presence: UN Peacekeeping and the Costs of Targeting Civilians.” International Organization 73, no. 1 (2019): 103–31. doi: 10.1017/S0020818318000346

- Fortna, V. Page. “Does Peacekeeping Keep Peace? International Intervention and the Duration of Peace After Civil War.” International Studies Quarterly 48, no. 2 (2004): 269–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00301.x

- Fortna, V. Page. Does Peacekeeping Work? Shaping Belligerents’ Choices after Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Fortna, Virginia Page, and Lise Morjé Howard. “Pitfalls and Prospects in the Peacekeeping Literature.” Annual Review of Political Science 11, no. 1 (2008): 283–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.041205.103022

- Francis, David J. “Peacekeeping in a Bad Neighbourhood: The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in Peace and Security in West Africa.” African Journal on Conflict Resolution 9, no. 3 (2009): 87–116.

- Freear, Matt, and Cedric De Coning. “Lessons from the African Union Mission for Somalia (AMISOM) for Peace Operations in Mali.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2, no. 2 (2013): 23. doi: 10.5334/sta.bj

- Friesendorf, Cornelius, and Susan E. Penksa. “Militarized Law Enforcement in Peace Operations: EUFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” International Peacekeeping 15, no. 5 (2008): 677–94. doi: 10.1080/13533310802396277

- Gaibulloev, Khusrav, Justin George, Todd Sandler, and Hirofumi Shimizu. “Personnel Contributions to UN and Non-UN Peacekeeping Missions: A Public Goods Approach.” Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 6 (2015): 727–42. doi: 10.1177/0022343315579245

- Gelot, Linnéa. Legitimacy, Peace Operations and Global-Regional Security. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Gilligan, Michael J., and Ernest J. Sergenti. “Do UN Interventions Cause Peace? Using Matching to Improve Causal Inference.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 3, no. 2 (2008): 89–122. doi: 10.1561/100.00007051

- Gilligan, Michael, and Stephen John Stedman. “Where Do the Peacekeepers Go?” International Studies Review 5, no. 4 (2003): 37–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1079-1760.2003.00504005.x

- Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg, and Håvard Strand. “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 39, no. 5 (2002): 615–37. doi: 10.1177/0022343302039005007

- Griffin, Michèle. “Retrenchment, Reform and Regionalization: Trends in UN Peace Support Operations.” International Peacekeeping 6, no. 1 (1999): 1–31. doi: 10.1080/13533319908413755

- Haass, Felix, and Nadine Ansorg. “Better Peacekeepers, Better Protection? Troop Quality of United Nations Peace Operations and Violence against Civilians.” Journal of Peace Research 55, no. 6 (2018): 742–58. doi: 10.1177/0022343318785419

- Hegre, Håvard, Lisa Hultman, and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård. “Evaluating the Conflict-Reducing Effect of UN Peacekeeping Operations.” The Journal of Politics 81, no. 1 (2019): 215–32. doi: 10.1086/700203

- Heldt, Birger. “UN-Led or Non-UN-Led Peacekeeping Operations?” IRI Review 9 (2004): 113–39.

- Heldt, Birger, and Peter Wallensteen. Peacekeeping Operations: Global Patterns of Intervention and Success, 1948–2004. Stockholm: Folke Bernadotte Academy, 2007.

- Högbladh, Stina. UCDP GED Codebook version 19.1. Uppsala: Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, 2019.

- Howard, Lise Morjé. UN Peacekeeping in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Howard, Lise M. Power in Peacekeeping. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Hultman, Lisa. “Keeping Peace or Spurring Violence? Unintended Effects of Peace Operations on Violence against Civilians.” Civil Wars 12, no. 1–2 (2010): 29–46. doi: 10.1080/13698249.2010.484897

- Hultman, Lisa, Jacob Kathman, and Megan Shannon. “United Nations Peacekeeping and Civilian Protection in Civil War.” American Journal of Political Science 57, no. 4 (2013): 875–91.

- Hultman, Lisa, Jacob Kathman, and Megan Shannon. “Beyond Keeping Peace: United Nations Effectiveness in the Midst of Fighting.” American Political Science Review 108, no. 4 (2014): 737–53. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000446

- Hultman, Lisa, Jacob Kathman, and Megan Shannon. “United Nations Peacekeeping Dynamics and the Duration of Post-Civil Conflict Peace.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 33, no. 3 (2016): 231–49. doi: 10.1177/0738894215570425

- Iacus, Stefano M., Gary King, and Giuseppe Porro. “Causal Inference without Balance Checking: Coarsened Exact Matching.” Political Analysis 20, no. 1 (2012): 1–24. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpr013

- International Peace Institute. “IPI Peacekeeping Database.” http://www.providingforpeacekeeping.org/contributions/, 2019.

- Jetschke, Anja, and Bernd Schlipphak. “MILINDA: A New Dataset on United Nations-Led and Non-United Nations-Led Peace Operations.” Conflict Management and Peace Science Online first (2019). doi:10.1177/0738894218821044.

- Kathman, Jacob D. “United Nations Peacekeeping Personnel Commitments, 1990–2011.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30, no. 5 (2013): 532–49. doi: 10.1177/0738894213491180

- Kathman, Jacob, and Michelle Benson. “Cut Short? United Nations Peacekeeping and Civil War Duration to Negotiated Settlements.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63, no. 7 (2019): 1601–29. doi: 10.1177/0022002718817104

- Keohane, Daniel. “Lessons from EU Peace Operations.” Journal of International Peacekeeping 15, no. 1–2 (2011): 200–17. doi: 10.1163/187541110X540544

- Lotze, Walter. “Mission Support to African Peace Operations.” In The Future of African Peace Operations – From the Janjaweed to Boko Haram, edited by Cedric de Coning, Linnéa Gelot, and John Karlsrud, 76–89. London: Zed Books, 2016.

- Mackinlay, John, and Peter Cross. Regional Peacekeepers: the Paradox of Russian Peacekeeping. Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 2003.

- Melander, Erik. “Selected To Go Where Murderers Lurk? The Preventive Effect of Peacekeeping on Mass Killings of Civilians.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 26, no. 4 (2009): 389–406. doi: 10.1177/0738894209106482

- Muggah, Robert. “Peacekeeping Operations and the Durability of Peace: What Works and What Does Not?” In Meeting note of the Third International Experts Forum (IEF), New York, 10 December 2012. New York: International Peace Institute, 2013.

- Mullenbach, Mark. “Third-Party Peacekeeping Missions (Version 3.1).” Harvard Dataverse, 2017.

- Mullenbach, Mark J. “Deciding to Keep Peace: An Analysis of International Influences on the Establishment of Third-Party Peacekeeping Missions.” International Studies Quarterly 49, no. 3 (2005): 529–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00376.x

- Nilsson, Desirée. “Partial Peace: Rebel Groups Inside and Outside of Civil War Settlements.” Journal of Peace Research 45, no. 4 (2008): 479–95. doi: 10.1177/0022343308091357

- Pettersson, Therése, and Kristine Eck. “Organized Violence, 1989–2017.” Journal of Peace Research 55, no. 4 (2018): 535–47. doi: 10.1177/0022343318784101

- Phayal, Anup, and Brandon C. Prins. “Deploying to Protect: The Effect of Military Peacekeeping Deployments on Violence Against Civilians.” International Peacekeeping Online first (2019). doi:10.1080/13533312.2019.1660166.

- Ruffa, Chiara. “What Colour for the Helmet? Major Regional Powers and their Preferences for UN, Regional or Ad Hoc Coalition Peace Operations.” Perspectives on Federalism 1 (2009): E-68–E-96.

- Ruggeri, Andrea, Han Dorussen, and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis. “Winning the Peace Locally: UN Peacekeeping and Local Conflict.” International Organization 71, no. 1 (2017): 163–85. doi: 10.1017/S0020818316000333

- Sambanis, Nicholas, and Jonah Schulhofer-Wohl. “Evaluating Multilateral Interventions in Civil Wars: A Comparison of UN and Non-UN Peace Operations.” In Multilateralism and Security Institutions in an Era of Globalization, edited by Dimitris Bourantonis, Kostas Ifantis, and Panayotis Tsakonas, 252–87. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). “SIPRI Multilateral Peace Operations Database.” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. https://www.sipri.org/databases/pko, 2019.

- Sundberg, Ralph, and Erik Melander. “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013): 523–32. doi: 10.1177/0022343313484347

- Tavares, Rodrigo. “The Participation of SADC and ECOWAS in Military Operations: The Weight of National Interests in Decision-Making.” African Studies Review 54, no. 2 (2011): 145–76. doi: 10.1353/arw.2011.0037

- UN Secretary-General. Partnering for Peace: Moving towards Partnership Peacekeeping (S/2015/229). New York: United Nations, 2015.

- UN Security Council. Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1026 (S/1995/1031). New York: United Nations, 1995.

- von Hippel, Karin. “NATO, EU, and Ad Hoc Coalition-Led Peace Support Operations: The End of UN Peacekeeping or Pragmatic Subcontracting?” Sicherheit und Frieden (S+F) / Security and Peace 22, no. 1 (2004): 12–8.

- Williams, Paul D. “Global and Regional Peacekeepers: Trends, Opportunities, Risks and a Way Ahead.” Global Policy 8, no. 1 (2017): 124–9. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12393

- Wondemagegnehu, Dawit Yohannes, and Daniel Gebreegziabher Kebede. “AMISOM: Charting a New Course for African Union Peace Missions.” African Security Review 26, no. 2 (2017): 199–219. doi: 10.1080/10246029.2017.1297583

- World Bank. “World Bank Indicators.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator, 2018.

![Figure 8. Coefficient plot comparing effect of troops and police by sender type [with different samples].](/cms/asset/4638d87b-1c6a-497b-8945-eef08a7a8905/finp_a_1737023_f0008_ob.jpg)