ABSTRACT

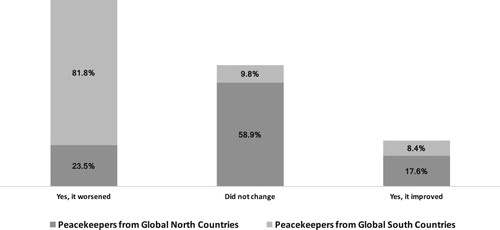

Why do the attitudes of United Nations military peacekeepers towards peacekeeping shift after their deployment from positive to negative ones and how do labour hierarchies influence this shift? Using surveys with military peacekeepers gathered within a professional military education (PME) context, we conducted an exploratory pilot study about individual attitudes towards UN peacekeeping operations (UNPKOs) after deployment. We found that a majority changed their opinion about UNPKOs as an effective tool for peacebuilding from positive to negative. Specifically, we found that 82% of troops from the Global South changed their perceptions from positive to negative after deployment; while 59% of Global North peacekeepers did not change their perceptions. This shift was on account of enduring command and control challenges, problems with analysing intelligence, and, the growing demands of robustness to protect civilians, which increasingly place peacekeepers from the Global South at the risk of armed attacks and under scrutiny for underperformance. Findings urge scholars and policy-makers to address the problem of labour hierarchies in the political economy of peacekeeping as a significant source of misalignment between the perceptions and experiences of troops from the Global South and the growing expectations of performance from them.

Introduction

Burden sharing in the political economy of peacekeeping is characterized by a triangular configuration between countries that mandate PKOs, those that pay for peacekeeping; and the major troop and police contributors from Asia, Africa and Latin America.Footnote1 According to a 2019 estimate, troops from countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America provide around 92% of all military and police personnel for UN peace operations, while contributing about 15% of the budget.Footnote2 Most countries from the Global North, are hesitant to field troops on the ground. BlocqFootnote3 notes that Western armed forces, have contributed little to post-millennium UNPKOs in Africa. In some cases, France and the UK have intervened unilaterally in a lead nation role such as in Mali and Sierra Leone, without placing their troops under UN command.Footnote4 In other cases, there is a push to create regional responses to security issues that offer ‘African solutions for African problems’. The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) is a case in point.Footnote5 Therefore, the western approach to UNPKOs tends to be more sceptical from the outset, this scepticism combined with Western hypersensitivity to body bags has resulted in peacekeeping being contracted out to militaries from the Global South.

Individual countries from the developing world gain both material and non-material gains such as on-the-job training, operational experience of international deployment, international reputation and legitimacy, and claims to regional leadershipFootnote6 by participating in peacekeeping. The hiring of Global South troops is further incentivised through ‘dependent militarisation’Footnote7 and ‘foreign aid’.Footnote8 In light of this division of labour, Malone and ThakurFootnote9 refer to the ‘growing apartheid’ or the ‘tribalisation’ in peacekeeping. There are well-documented differences in how troops interpret and implement the mandate regardless of their origin.Footnote10 The problems are more acute when troops are ill-trained or ill-equipped,Footnote11 or when they execute mission mandates based on the political direction from their national capitals.Footnote12 Expectations from peacekeepers on the part of the UN has evolved over time as well. Shifting from neutral minimalist behaviour to partial behaviour in targeting armed groups to protect civilians when the host state itself is unwilling or unable to do so.Footnote13 The push towards robust peacekeeping involves a calibrated use of force on a tactical level in self-defence or in defence of the mandate.Footnote14

There is also a disproportionate distribution of risk. Peacekeepers from the Global South are deployed to the most dangerous areas within UNPKOs. Polman describes how contingents are camped ‘according to country of origin … with the poorer countries located closer to the outer wall of the base.’Footnote15 Global South TCCs can be resentful of the fact that they are brought in to implement UN peacekeeping mandates by providing troops without being able to influence its decisions.Footnote16 Voicing discontent, the Permanent Representative of India to the UN in 2011, highlighted that while Western powers are willing to intervene unilaterally or in ‘coalitions of the willing’, and in pursuit of their own national interest and geopolitical considerations such as with the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance (NATO) in Afghanistan, they choose not to deploy for UNPKOs.Footnote17 Not all developing countries are complicit in this division of labour to be cast as ‘hired help’. In Sierra Leone, for example, Jordan pulled out 1800 troops from the UN Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) in October 2000, citing the lack of western company.Footnote18

Mismatches about expectations of what action is appropriate, the speed and directness with which responses should be made or the motivations which guide actions have created further frictions along North–South lines. Cases of reticence or non-use of force in alignment with mission mandates by Global South troops, has triggered the push for performance accountability in UNPKOs through the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2436 (2018) and the Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative. New systems of performance evaluation for military and police units have been introduced across all missions. The DPO has developed the Comprehensive Performance Assessment System (CPAS), to help make missions ‘more effective at preventing and resolving violent conflict by bringing together data and analysis to help missions respond more quickly to changes in the local context, and assess their impact and effectiveness to inform future operations’.Footnote19 Underperforming troops have been repatriated in some cases, and mentors or training teams deployed in other instances.Footnote20 At the same time a punitive, confrontational narrative of blame is counter-productive given the lopsided nature of troop deployments.Footnote21 It requires a more nuanced understanding of the role of labour hierarchies in shaping the perceptions, expectations and experiences of the peacekeepers themselves.

Before presenting the paper structure, a note on terminology is necessary. Labour hierarchy is defined as the categories of employment involved in executing UN peacekeeping mandates. The real work of peacekeeping includes a diversity of roles both at the headquarters and at the field level, and across military and civilian portfolios. They involve different types of expertise, experience, and performance expectations. Those on the lower rungs of the labour hierarchy execute tactical or field level actions that involve physical presence. Those on the higher rungs of the labour hierarchy apply intellectual labour through strategic and policy decisions regarding the deployment of resources by the UN mission. For individuals, their location on the labour hierarchy creates differences in financial pay and benefits, in decision-making ability, and in their degree of exposure to direct physical security risks to armed violence. We use peacekeeping experience to include both traditional and more robust operations.Footnote22 An individual’s attitude is defined as their belief or views towards different aspects of the world and is the result of their own experiences and upbringing.Footnote23 Operational effectiveness is defined as decreasing conflict intensity in the short-term through coordinated command and control, intelligence and information sharing and civilian protection by multinational troops in a mission.Footnote24

Through online survey research with military peacekeepers we sought to answer the following research question: How do peacekeeping perceptions, experiences and expectations shape the attitudes of peacekeepers located on different rungs of the peacekeeping labour hierarchy? By asking peacekeepers to reflect on their experiences within a PME context where students are encouraged to reflect on, and learn from their operational experiences, and by illustrating that peacekeeping labour hierarchies can to some extent shape how experiences and expectations of peacekeeping are perceived, this study contributes to the fields of critical military studies and peace and conflict studies. The research also complements studies that examine peacekeeping attitudes after deployment and the experiences of peacekeepers in a multinational setting. With little attention paid to the growing misalignment between experience and expectations around peacekeeping performance, our exploratory pilot study with peacekeepers from both the Global North and the Global South opens up new avenues for future research and offers preliminary evidence.

The paper proceeds as follows. It begins with a conceptual framing on peacekeeping attitudes of troops, and the labour hierarchies in the political economy of peacekeeping. This introduces the theoretical framework around ‘perceptions, experiences, expectations and labour hierarchies’ that is applied to the study of operational effectiveness of UNPKOs. A methodological statement follows. Empirical findings from the two online surveys with regard to shifts in peacekeeping attitudes post-deployment, and the operational experiences of command and control, information and intelligence sharing and civilian protection roles are presented next. A further Global North and Global South lens is applied to the data analysis. This distinction in the respondent sample allows us to analyse whether post-deployment attitudes towards peacekeeping are shaped by the gap between perceptions, experiences and expectations, depending on one’s position in the labour hierarchy. Key contributions of the paper and avenues for future research are summarized in the final section.

Peacekeeping Attitudes and Labour Hierarchies: Caught Between Perceptions, Experiences and Expectations

Peacekeeping as a form of employmentFootnote25 comes with perceptions, experiences and expectations both from the peacekeepers and from the international community that mandate and fund UNPKOs. It is also one which presents hierarchical labour dynamics given the predominance of troops in the field from the Global South, and experts from the Global North at the headquarters of various missions. This labour dynamic features in the attitudes of peacekeepers towards peacekeeping tasks, towards other troops in the field, and toward those in mission command. It also presents important considerations around troop performance alluded to earlier. Pre-existing beliefs around efficiency or effective operational performance in a military context, can promote racialised perceptions of peacekeeping labour and their operational effectiveness on the part of the UN and the international community. These can often reinforce deep-seated prejudices or colonial stereotypes around nationality and race. Henry notes that, ‘ … orientalist accounts of South Asian men as morally corrupt, sexually predatory, and conversely as effeminate and weak, perpetuates depictions of certain troops in colonial and stereotypical ways.’ Footnote26

Soldier’s own perceptions or self-image of individual capabilities during peacekeeping deployments differ based on their own location in the labour hierarchy and whether soldiers define themselves as combat soldiers or as peace helpers in uniform. Traditional peacekeeping was aligned with a constabulary ethic,Footnote27 more in the nature of policing.Footnote28 Galtung and Hveen’s study of Norwegian peacekeepers in Gaza (UNEF) and Congo (ONUC) found that most soldiers adhered to the minimum role definition in terms of observation, patrol, and deterrence through presence.Footnote29 Tomford found that British, American and French soldiers defined themselves mainly as combat soldiers.Footnote30 Italian soldiers, however, focused on peacekeeping rather than warfighting.Footnote31 Swedish soldiers deployed to Liberia and Kosovo, faced dilemmas based on their preference for neutrality and their perceived high moral standards.Footnote32 Transforming the military profession into a constabulary force requires a different set of skills, one that sensitizes soldiers to the political and social consequences of military action.Footnote33 Restrictions on the use of force however does not automatically result in a negative shift in soldier’s attitude towards peacekeeping.Footnote34 In some cases, soldiers felt peacekeeping missions could be performed without the use of force.Footnote35 In other cases, peacekeepers like the Dutch prepared for combat during pre-deployment training due to negative experiences in the field such as the Srebrenica massacre of July, 1995.Footnote36

Several studies about how the military experience their daily life and perceive multiculturalism during operations, suggest that conflicts and misunderstandings between troops may well be the result of cultural differences, their different thinking and reasoning styles.Footnote37 Troops operate within their own cultural sphere,Footnote38 and according to their own understanding of the situation and in line with national intervention policies and practices.Footnote39 Chiara Ruffa’s research about how the French, Ghanaian, Italian, and South Korean militaries responded operationally to the UN Mission in Lebanon (UNIFIL) found that the different contingents varied in their construction of the operating environment. This was in line with their learned military behaviours. These behaviours influenced responsiveness and execution of daily military activities in the peacekeeping context. By responding according to learned patterns of behaviour,Footnote40 TCCs can shape the operational practices and strategic coherence of the mission.Footnote41

Previous research on whether peacekeeping experiences change soldier’s individual attitudes suggest that attitude change can be both positive and negative.Footnote42 From a utilitarian perspective, soldiers who expect a peacekeeping assignment to help their careers are expected to be more positive towards such an assignment.Footnote43 Conversely, those who enjoy peacekeeping assignments but do not find it helpful for career progression, may change their attitude towards peacekeeping by changing their beliefs.Footnote44 From a psychological perspective, exposure to stressful events during peacekeeping deployment can shape soldiers’ attitudes as well.Footnote45 Feelings of powerlessness in protecting civilians, frustration with the rules of engagement (ROE), isolation, family separation and the hardships associated with deployment in conflict affected areas – insects, poor sanitation facilities, boredom and limited supplies of food, water, and electrical power,Footnote46 can create negative associations with peacekeeping.Footnote47 More positively, exposure to conflict zones, marked by civilian displacement and violence can enhance soldiers’ appreciation of peacetime military functions.Footnote48 Attitudes were more positive when peacekeeping deployments improved soldier skills at the small-unit level and developed leadership skills among non-commissioned officers (NCOs).Footnote49 However, as the number of deployments increased, soldiers reported lower morale due to living conditions, food quality, and leadership quality, especially for soldiers with families.Footnote50

Expectations about appropriate behaviour, and the nature and timing of responses are culturally based expectations. These relate to how different cultural groups accept and relate to power in the international system. Culture allows people to interpret their experiences and see their own and other’s action as proper and meaningful.Footnote51 Pressure from the United States to reduce peacekeeping budgets while asking TCCs to perform better creates increased expectations around performance and efficiency in the execution of mandates,Footnote52 reinforcing areas of inequality and opening up the scope for potential dissent. Current research on peacekeeping attitudes focuses on the experiences of British, American, French, Italian, Swedish and Dutch soldiers. There are comparatively fewer studies which address the experiences of soldiers from both the Global North and the Global South. A balance that is necessary because North–South divisions are increasingly prominent in the peacekeeping labour economy. Therefore, understanding peacekeeping attitudes and labour hierarchies in UNPKOs requires an understanding of not only the behaviour of countries at the UN, but also the gap between the experiences of troops in the field and the expectations from them.

Our study contributes to this gap in the current theorizing on the subject. We argue that the perceptions, experiences and expectations of military peacekeepers are shaped by their location in the labour hierarchy of peacekeeping. Troops from the Global South that field troops are expected to perform and execute mandates determined by countries mostly from the Global North that fund UNPKOs. Under-resourced missions place peacekeeping troops increasingly at the risk of armed attacks, which compromises their operational effectiveness, yet enforcement of accountability for underperformance is on the rise. This creates expectations of robust performance from Global South troops while generating experiences of unfairness, perceptions of inequality and added burdens on their part. This mismatch between the operational experiences of Global South troops and the perceptions and expectations around operational effectiveness when framed through the lens of labour hierarchies enables the study of attitude change after peacekeeping deployment from positive to negative ones.

Methodology

Based on our review of the literature, the issues around C2, information and intelligence sharing, and civilian protection challenges were identified as the most important ones affecting the operational effectiveness of UNPKOs. These were also areas where labour hierarchies were prominent. We therefore concentrated on these three areas to bound the study and to frame the survey questions.Footnote53 To operationalize the research, we designed a pilot study within a PME context, inviting military staff attending the Advanced Command and Staff Course (ACSC) to volunteer during 2017–2018. The ACSC is the flagship course offered at the United Kingdom Defence Academy open to both British and foreign nationals. Given that many on the course had deployed on various UNPKOs, the ACSC student cohort provided the necessary mixed sample population for the research.Footnote54 Around 270 students are selected each year, a third of which are international students.Footnote55 In terms of the composition of students, the top 20% of officers attend the ACSC. Officers are typically mid-career and pre-Command, with ACSC aiming to prepare them for operational level Command roles. This study cohort constituted the sample population. Both academic and military staff involved on ACSC approved the surveys to be used. Ethical approval for the study was secured from the University Research Ethics Committee.

Respondents were briefed about the main objectives of the study as part of the online survey form, and only those who consented to take part in the surveys are sampled here. Based on the return from Survey I, only 50 respondents fulfilled the research criteria (See ). The first survey collected demographics and information on nationality, rank, roles performed, the duration of deployments, and primary and secondary tasks undertaken while deployed. We also asked respondents about their attitude towards UNPKOs before being deployed for the first time in terms of their perceptions. More specifically we asked if there was a shift in their attitude towards UNPKOs based on their experiences while deployed and why. Only 60% or 30 respondents from Survey I, volunteered to take part in Survey II. The second survey included multiple choice and open-ended questions related to their operational experience, such as working in a multinational setting, command and control (C2), management of intelligence, and ROE related to protection of civilians (Appendix1).

Table 1. Peacekeepers’ deployment by UN Mission/CountryTable Footnotea.

Data were collected through Google Forms was analysed with Google Sheets. Various charts and tables were generated and response averages calculated. We did not interview the respondents in person to ensure anonymity and to avoid problems with security clearance for the international students. We used the responses from Survey I and II to analyse how these issues impacted the soldier’s attitude towards, and perceptions of, peacekeeping missions, in terms of operational effectiveness and core peacekeeping functions, disaggregating responses along the Global North-Global South categories as part of our secondary analysis. The rationale for drawing this distinction was to interpret the nuances of labour hierarchies in shaping peacekeeping attitudes with regard to perceptions, experiences and expectations as developed in the theoretical framework.

The research and related methodology accounted for the limitations of the sample population accessible through the voluntary research design and via online surveys. First, the small sample size, and with all respondents being male the generalisability of the analysis is compromised. The limited time available to students during a compressed academic study year combined with multiple field visits to Europe and the United States meant the respondent return was lower than anticipated. International military students were more hesitant to participate due to official protocols around divulging nationally sensitive information, although they had the most experience in UNPKOs compared to the British officers. Second, the measure used to collect data – online surveys, did not allow more respondent specific questions that could have assisted in exploring the issues in greater depth. As a result, the population to which surveys were distributed cannot be described, and voluntary participation in the surveys, can result in respondents with biases selecting themselves into the sample.Footnote56

Survey I: Demographics

The sample population of 50 students who responded to Survey I, included military personnel from 18 countries with diverse operational background and military branches, and with different rank levels. Global North countries in the sample included UK, US, Australia, New Zealand, Netherlands, France, Japan and Bosnia Herzegovina. The Global South countries included Kenya, Pakistan, Ghana, Cameroon, Egypt, Niger, Nigeria, Nepal, Malaysia, and Kuwait. In terms of troop contribution, these countries represent variable levels of contribution to UNPKOs over the years. Some like Pakistan, Ghana, Nepal and Egypt were top 10 contributors in 2018.Footnote57 Therefore, some students had experience of multiple deployments. 57.7% (29) of respondents had participated in one PKO, 23.1% (11) in two operations, 15.4% (7) in three, and 3.8% (2) in four PKOs. At the time of their participation in UNPKOs, 35% (17) of the survey’s participants were Army-equivalent Captain (OF2), 24% (12) were Major (OF3) or Lieutenants (OF1), and both Troops (E) and Lieutenant Colonels (OF4) were a minority, with just 3% (1) (). Indeed, Majors and Captains together represented 70% (37) of respondents in terms of their rank when they first deployed as peacekeepers.Footnote58 In particular, Company and Battalion Commanders (OF2 and OF3) represented more than 30% (15). 23% (11) of the Captains had commanded platoons, and Majors constituted the bulk of the Staff Officer cadre at 19% (9). Respondents spent on average 7.7 months in the field, with a minimum of four months for 11.5% (5 respondents) and 12 months for 23% (11 respondents).

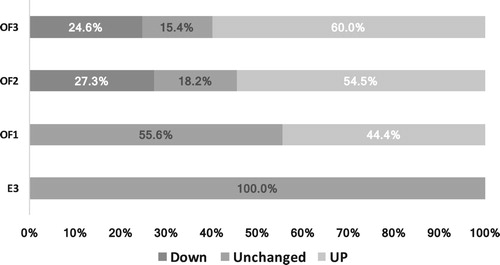

Figure 1. Change in peacekeepers’ attitude towards international PKOs by rank (ex-ante vs. ex-post deployment).

Depending on their mission (), the participants engaged in multiple tasks within their mandate, including traditional peacekeeping, cease-fire monitoring, protection of civilians, humanitarian assistance, election supervision, advancement of democracy, government capacity-building, disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of former combatants, support to local law and order, promotion of the rule of law, and reform of the security sector (SSR). Other important mandates, such as specialist advisors on human trafficking and counterterrorism, were noted in 5.4% (2) and 3.6% (1) of the sample respectively. SSR and DDR represented 80% of all secondary tasks – 42.9% (21) and 35.7% (17), respectively. Other tasks such as humanitarian assistance, intelligence, and peace monitoring accounted for 3.6% (1) of self-reported functional involvement.

Survey I: Peacekeeping Attitude Change

In Survey I, we asked three questions related to peacekeeping attitudes. First, what was your attitude towards UNPKOs before participating for the first time? Second, do you recall if your attitude towards UNPKOs changed upon completing your deployment as a peacekeeper and returning to your country? Third, what was the primary reason for the change if any? An analysis, by rank, of peacekeepers attitude towards PKOs before being ever deployed showed that those of higher rank had some reservations about the effectiveness of PKOs in countries affected by conflict and violence. They perceived the UN’s efforts as ineffective in these countries. In contrast, younger officers (OF1) and troops were more confident about the UN; and their attitude towards PKOs indicated higher levels of approval, as they had less experience. This point is supported in the literature. Segal and Tiggle have found that experienced officers with combat experience viewed unarmed or traditional peacekeeping as detrimental because professional soldiers cannot perform peacekeeping and war-fighting missions with equal effectiveness, due to the different mindsets required.Footnote59

After their first deployment and following the operational experience of PKOs, 27.3% (4/17) of OF2, and 24.6% (3/12) of OF3 changed their opinion about PKOs from largely positive to negative. The attitudes for the OF1 ranks or the junior troops did not worsen (). With regard to the primary reason for change in their perception from positive to negative, the OF2 and OF3 respondents indicated that countries did not operate ‘super partes’ or impartially, and this was the main reason for their negative perception change. A lack of political will to implement PKOs’ mandates on the part of TCCs, overly restrictive ROE that limited the scope of operations, and the low professional level of some PKO troops accounted for further reasons for a negative shift in attitude. For a third of the respondents (15), whose views of PKOs improved after deployment, reasons like the troops’ neutrality and impartiality on the ground combined with the efforts by TCCs with limited military resources contributed to improving their view of PKOs after their deployment. 17% (8) of the respondents reported that their attitude towards PKOs improved after deployment without specifying the rationale for such a change ().

Figure 2. Peacekeepers’ post-deployment attitude towards UN PKOs by their country of origin’s level of development.

When we disaggregated the respondent sample (50) by country of origin into Global North (n = 36) and Global South categories (n = 14), we found that prior to their first deployment, more than 63% (8) of peacekeepers from the Global South considered the UN as well-suited for performing peacekeeping tasks, with two respondents extremely positive about the UN. Only one respondent expressed negativity towards UNPKOs. After their first deployment, 82% (11) of respondents from the Global South countries no longer felt positively about the UN. For one respondent, there was an improved perception after deployment, and for two of the respondents their attitudes towards UNPKOs did not change. Peacekeepers from the Global North in contrast, had a mostly neutral attitude towards UNPKOs prior to being deployed for the first time. 59% (21) of the respondents from the Global North did not change their pre-deployment perception, and only 17.6% (6) of them improved their attitude towards UNPKOs after their deployment. We investigated these shifts further in Survey II across three areas of operational experience: command and control issues, intelligence collection and information sharing, and finally, the demand for civilian protection. The aim was to investigate if the combination of perceptions, experiences and expectations and the labour hierarchies in the political economy of peacekeeping influenced the shift in peacekeeping attitudes from positive to negative.

Survey II: Findings

In the Survey II sample (n = 30), 13 of the respondents reported to have participated in medium size PKOs involving 10–20 troop contributing countries (TCC). 11 have PKO experience in minor operations with less than 10 TCCs, and only four were involved in major PKOs with more than 20 TCCs. The experience of working in a multinational environment was mixed. 80% of peacekeepers (24) considered the multinationalism of units as a major obstacle to troops’ coordination in the field. Nevertheless, 77% (23) of respondents had positive experiences with soldiers from other nations and only 23% (7) could not define that as a good experience. Among those who did not have a positive experience working in an international setting, 18% (5) indicated language as the major obstacle to coordination. For 16% (4), a major issue was the difference in mentality and culture, while 14% (4) of respondents found restrictive ROE as a major obstacle for smooth, coordinated operations. These findings are supported in the earlier studies.Footnote60 Contrary to expectations that national allegiances would be weakened, most studies find that peacekeeping missions witness a reinforcement of the sovereignty, agency and national interests of troops.Footnote61 This is because disciplinary measures are determined by national law and by the national chain of command from their direct reports in the field. The UN has very little recourse to discipline as troops are only seconded to the organization.Footnote62 Command and control (C2) and how it plays out in the mission environment is a core concern for the study of peacekeeping effectiveness.Footnote63 Few studies examine operational effectiveness through the lens of labour hierarchies, a gap that we address here.

Operational Experiences of Command and Control

Unity of command is perceived as essential in UN peacekeeping and is the key expectation for the effectiveness of operations. The force commander is formally granted operational command over national contingents. This allows the force commander to assign tasks to subordinate commanders and deploy forces through operational directives.Footnote64 National differences in staff procedures, training, equipment, and language can make coordination of deployed troops from different countries complicated however.Footnote65 Each national battalion brings with it its own particular cultural complex and set of assumptions.Footnote66 Their cultural differences can give rise to barriers to smooth interaction, and possible misunderstandings. Fetherston and Nordstrom remind us that peacekeepers interpret the world through the lens of their own culture, i.e. their own habitus.Footnote67 When under threat in a peacekeeping environment, soldiers act according to learned patterns of behaviour, rather than responding to the actual conditions of a particular situation.Footnote68 These include, using armed force rather than communication techniques or refraining from taking robust action based on their organizational approaches to handling insurgents.Footnote69 Lack of unit cohesion, unclear command relationships, and uncertainty about how to relate to foreign soldiers in a multi-national environment can present early deployment stressors in the field.Footnote70 Soldiers are known to experience frustration and powerlessness in getting past multiple layers of military and government bureaucracies during the mid-deployment phase, while uncertainty, ambiguity, and boredom can be prominent in the late deployment phase.Footnote71

LeckFootnote72 notes that C2 arrangements in UNPKOs can create gaps in the attribution of conduct. Military contingents are deployed in PKOs only after their specific tasks and zones of deployment have been negotiated and agreed upon between the TCCs and the UN Department for Peace Operations (DPO). Risk averse TCCs would not contribute troops without these caveats in place. The UN must accept these national restrictions on the employment of peacekeepers. Restrictions and risk aversion are common across a range of TCCs. Smith and Dee cite some of the national restrictions pertaining to Australian troops’ deployment within East Timor and the stringent conditions attached to the use of Australian Blackhawk helicopters.Footnote73 The UN has declared that it cannot accept TCC restrictions that compromise the mission, but in legal terms, these are non-binding guidelines rather than legal requirements. As such, peacekeepers follow national directions before executing orders of the Force Commander (FC).Footnote74 They enjoy the upper hand, as they can always withdraw troops. Clearly, there is a gap between expectation on part of the UN and the experience of peacekeepers. To probe this issue further, in Survey II, we asked participants to describe how multiple C2 systems shaped their experience of PKOs at the operational level.

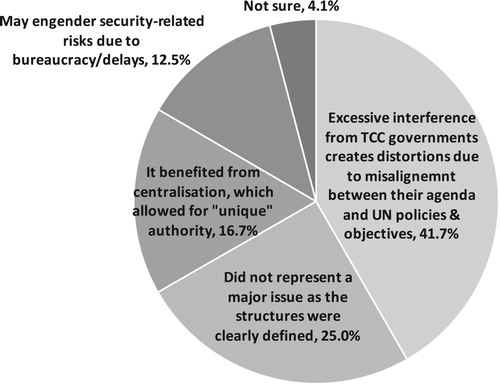

54.2% (16) of the respondents admitted that they were accountable to multiple official lines of command and were required to report to more than one commander or authority in charge of supervising their activities at the operational level. According to 41.7% (12) of participants, excessive interference from the TCC governments created distortions in carrying out their mission assignment due to a misalignment between national interests, UN policies, and the UN field headquarters. When the TCC or national contingent commander (NCC) consent to any tasks while being fully aware that the assigned task, if mishandled, may lead to violations of international humanitarian and human rights law, the onus in terms of duty of care and vigilance resides with the NCC.Footnote75 They must ensure that troops do not violate any laws in carrying out instructions from the UN Force Commander, so they remain cautious in executing orders that can cause C2 complications. For 25% (7) of the respondents, multiple C2 systems did not represent a major issue as the command structures were clearly defined. 16.7% (5) confirmed that operations benefited from centralization. However, 12.5% (3) of peacekeepers highlighted centralization created bureaucratic delay in response times. When a rapid response is required, unit commanders lost both time and initiative in having to consult with multiple authorities (). More than 45% (13) reported that parallel reporting using communication systems that allowed double entry was used to cater to the need for dual accountability. Worryingly, 27% (8) of respondents admitted to customizing their reported information based on the authorities’ needs and interests, either reporting non-relevant information or worse, failing to report critical details.

Figure 3. Effects of multiple command and control (C2) systems on operational efficiency and effectiveness as perceived by peacekeepers.

Based on the misalignment between the UN’s expectations and the peacekeepers’ experiences of C2, we asked the respondents how the lack of unity in C2 could be better tackled? 44% (13) indicated that limiting the TCCs’ national interference could facilitate a rapid response in the field. 35% (10) called for more transparent communication. Finally, 21% (6) of participants suggested that a clear pre-deployment policy would ensure transparency, clarity, and operational rapidity for troops. Only 9% (2) suggested that organizing troops by culture and same level of development may be a possible way to tackle differences in capacity and capability. To improve the coordination of multinational troops, 41% (12) of peacekeepers suggested that the dissemination of standard operating procedures among TCCs prior to their deployment would facilitate interoperability, communication, and coordination once troops are in theatre. 27% (8) of the respondents felt an exchange programme including all TCCs conducted before any field deployment could create the basis for familiarization and greater coordination among troops; and 23% (7) of respondents thought that a supranational training centre would facilitate better operational coordination through a centralized and unified training programme. How peacekeepers are trained, socialized and deployed with regards to operational effectiveness does matter. While seeking uniformity, peacekeeping training transmits standards of behaviour or institutionalized norms that are translated differently by peacekeepersFootnote76 which explains the persistence of C2 problems.

A further Global North – Global South breakdown during the data analysis revealed that 66.7% (24) of peacekeepers from developed countries felt that strong interference from TCCs’ governments hampered their readiness and effectiveness. 42.9% (6) of peacekeepers from the Global South showed a negative attitude towards multiple C2s, identifying both joint training prior to deployment and unity of command without any TCC interference in decision-making as critical for more effective operations. In summary, regardless of their position in the labour hierarchy, respondents felt that C2 is problematic because the UN struggles to enforce effective control over peacekeeping troops. TCCs can build in caveats prior to deployment, and make demands regarding operations and ROE. Through their NCCs, TCCs can also disagree with any changes to where peacekeepers are deployed within the mission. The key point is that a TCC can, at any time, decline to take on a task, and this was true of both Global North and Global South troops.

Intelligence Management and Information Sharing Between Peacekeeping Contingents

Most studies agree that intelligence collection and sharing has historically been a sensitive issue, with most PKOs traditionally lagging in terms of suitable intelligence.Footnote77 The UN is also plagued by a lack of cooperation with regard to intelligence, with the more powerful countries being reluctant to share information and intelligence with troops on the ground. As a result, many TCCs find themselves limited in operations. Some well-known failures, such as in Rwanda (1993), have been attributed to lackadaisical intelligence collection and sharing.Footnote78 To remedy these shortcomings, a situation centre within the DPO was established in 1993 to ‘speed up, complement, and amplify information flows.’ This was intended to enable timely decision-making by the Under-Secretary General for UN Peacekeeping.Footnote79 The Brahimi report (2000) boosted these efforts, recommending the creation of an Information and Strategic Analysis Section. A consensus was reached by the early 2000s that the UN should be allowed to produce more efficient tactical and operational intelligence for PKOs to respond more effectively to field level threats. By 2006, the DPKO set up a Joint Mission Analysis Centre (JMAC) in each PKO to conduct all source information gathering.Footnote80

The High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HiPPO) report (2015) emphasized the need to further strengthen analytical capabilities of peace operations.Footnote81 In May 2017, the first UN Peacekeeping Intelligence Policy was established. In March 2018, the Secretary General launched the A4P initiative, stressing the need for effective intelligence to identify threats to peacekeepers from armed groups. In response to digital innovation, the UN has begun to collect data through the Situation Awareness Geospatial Enterprise (SAGE) event database tool. SAGE allows UN military, police, and civilian staff to log incidents across UNPKOs and special political missions. It is in the process of being rolled out by the UN Secretariat to all peacekeeping and peacebuilding field missions.Footnote82

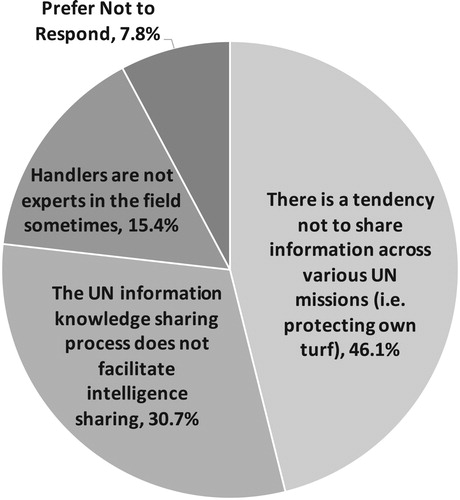

Therefore, the expectation of efficient and timely responses to armed groups threatening local security has grown. Yet, in our study, over 61% (18) of respondents felt that intelligence gathering, management, analysis and sharing across peacekeeping forces was suboptimal in their experience. Over 18% (5) confirmed that governments tend to retain critical intelligence. Additionally, over 46% (13) of respondents were convinced that there is a tendency by the intelligence agencies not to share relevant information, a conviction that shaped their perception of inequality across intelligence sharing between the Global North and Global South troops. 31% (9) of respondents thought that staff responsible for intelligence gathering was not sufficiently knowledgeable for the task. 15.4% (4) thought that those in charge of information management are not experts. 29% (8) indicated that, regardless of the quality, intelligence is not shared openly across UN missions. Lastly, 16% (4) felt that even when intelligence gathering was done properly by the TCC units, the UN agencies failed to analyse and utilize information in a timely and efficient manner. 31% (9) of respondents indicated that this inefficiency was a result of the UN bureaucracy, and mechanical limitations or unsuitability of hardware and information systems ().

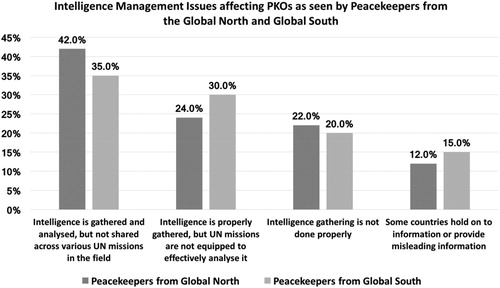

Respondents from both the Global North and the Global South – 83.3 (29) and 85.7% (12) respectively – agreed that intelligence management in UNPKOs is quite ineffective. There is a propensity for sharing information vertically. Structures favour sending information up, with muted horizontal information sharing, alongside limited flow from UN Headquarters to the field, reinforcing labour hierarchies. Inter-mission learning across countries was equally limited, despite the existence of the JMAC structures in each mission. Respondents however had some differences in their overall understanding on these issues. 42% (15) of the participants from the Global North felt that although intelligence was properly gathered and managed by the units it was not adequately shared with other units participating in the same operation. Nearly a third of the Global South peacekeepers felt that even when properly gathered, intelligence cannot be adequately evaluated due to limited capabilities of participating contingents to analyse intelligence (). Kuele and CepikFootnote83, in their study of intelligence structures in the UN Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO), support this observation. They note that human intelligence failures were attributable to weak analysis rather than a lack of information.

By way of remedying the problems with intelligence sharing, the officers from the Global North suggested assembling UN contingents by cultural closeness, which they felt might increase trust. Conversely, the Global South peacekeepers felt that, an effective solution could be employing intelligence professionals who would be able to effectively manage and circulate critical information across multiple units. Bove, Ruffa and RuggeriFootnote84 argue that cultural distance or closeness between the force commander and his troops does not translate into easier coordination. Romeo Dallaire’s frustration with Bangladeshi and Belgian troops in the UN Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) was balanced by his easier relations with the Ghanaians who though culturally distant performed as a well-led, cohesive unit.Footnote85 Therefore the expectation on part of Global North peacekeepers that cultural contiguity would encourage better intelligence sharing can be misplaced. The experience of the Global South peacekeepers regarding weak analysis, and application of available intelligence was better reflective of ground realities as reported in recent studies.

Demand for Civilian Protection

Protection of civilians (PoC) has featured prominently in contemporary debates around peacekeeping and a core expectation from troops. Commitment to robust action in executing the PoC mandate is perceived as the true test of troop performance. Since 1999, the UNSC has actively recognized and worked on this concept as a cornerstone of its ability to prevent and resolve violent conflict. The 2008 UN DPKO and Department of Field Support (DFS) Principles and Guidelines document has listed civilian protection as one of the primary and core tasks of peacekeeping missions.Footnote86 Scholars argue that missions which are diverse in their compositions and those operating in civil wars have been more successful in reducing violence and in protecting civilians.Footnote87 Peacekeepers often act as physical barriers between warring actors and civilians, and use different protection mandates to take necessary actions to shield civilians. The most common approach is to patrol regularly in high-risk areas, but more directed and calculated actions can also be taken. For example, the UN mission in Liberia arrested over 30 rebel fighters who were using firearms in a village in 2004.Footnote88

In practice, recent missions in DRC, South Sudan, Darfur and Côte d’Ivoire, have faced huge challenges in meeting the demand for civilian protection.Footnote89 On the one hand, UN Missions have developed targeted civilian protection strategies; and peacekeepers have carried out a large number of the humanitarian, political, and military tasksFootnote90, including strategies to safeguard civilians and reduce violence against them. On the other hand, military operations in UNPKOs are ridden with limited resources, considerations of collateral damage, false allegations, and ambiguity, especially regarding the combatant-civilian distinction.Footnote91 Often the host government’s soldiers are the ones responsible for ethnically targeted attacks on opposition sympathisers.

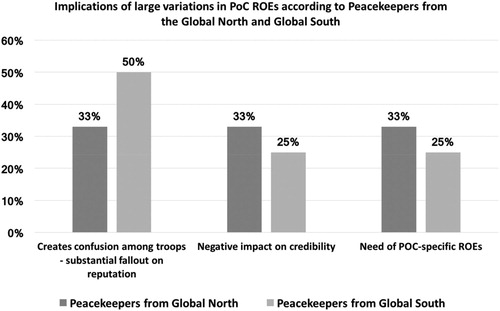

According to more than 61.5% (18) of the respondents, the ROEs regarding armed groups and PoC mandates vary considerably across different peacekeeping contingents. In the sample, 50% (7) of peacekeepers from the Global South felt that a lack of standardization in ROEs regulating PoC was the main cause for confusion across multiple contingents participating in the same operation which often had a negative fallout on the UN’s reputation. The remaining 50% (7) were equally divided between the arguments of negative impact on UNPKO’s credibility and the necessity of creating and implementing standardized ROEs specific for PoC, which, according to them, need to be adopted by all units in any UNPKO equally. That would, in fact, ensure standardization of procedures as well as interoperability among contingents from different countries, with a positive impact on UN operations in terms of both credibility and authority. Peacekeepers from the Global North were equally distributed over the three positions ().

Study respondents experienced considerable dilemmas over distinguishing between government and opposition groups while deployed in South Sudan and DRC. The host government forces would target civilians and behaved as much as a rebel group.Footnote92 In fact, peacekeepers attempting to keep peace between the parties to the conflict including the government, rebel factions, and greater population in South Sudan and the DRC have become the targets of armed attacks themselves.Footnote93 The UN Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) has recorded 93 fatalities of military, police, and civilian personnel since its inception in 2010. In December 2017, militants from the Islamist oriented Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) staged an assault on the UN base in the town of Semuliki in North Kivu’s Beni territory. At least 15 Tanzanian UN peacekeepers were killed, and 53 others wounded.Footnote94 Threat to life, once uncommon to peacekeepers, has become a more prominent stressor in recent missions. These conditions increase the risk for post-traumatic stress or dissociative disorders.Footnote95 Feelings of powerlessness in protecting civilians, and frustration with the ROE is known to generate negative views of peacekeeping.Footnote96 These factors and the danger to life experienced in recent missions helps explain the overall negative shift in some of the study’s respondents’ attitudes toward peacekeeping participation. As with C2 and intelligence sharing, the demand for PoC are mired in unrealistic expectations around performance, while the experience of troops when deployed does not enable the meeting of these expectations creating disappointment and further stressors.

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate why the attitude of military peacekeepers towards UNPKOs shift after their deployment from positive to negative and how labour hierarchies influence this shift? Using surveys with British and international military peacekeepers gathered within a PME context, we find that there is an important misalignment between the perceptions about, expectations from, and the experiences of troops. Although peacekeepers from both developed and developing areas, found ROEs very restrictive, with national agendas triumphing over UNPKOs’ mandates, difficulties of working in an unequal multinational environment, where task allocation and exposure to risk varied based on the nationality of the contingents, we found negatively impacted the perception and execution of set tasks of some troops more than others. These inequalities explain why 59% (21) of the respondents from the Global North did not change their pre-deployment perceptions, as their experiences were less negatively affected during their peacekeeping deployment. By contrast, 82% (11) of troops from Global South changed their perceptions about the UN’s ability to conduct PKOs for the worse after deployment.

By disaggregating the experiences of military peacekeepers from the Global North and Global South, our study adds to the literature in two ways. First, the criticism of troop performance and the formalization of accountability measures with punitive potential, generates negative perceptions around troop willingness to robust action.Footnote97 It can enhance feelings of resentment amongst Global South TCCs who are brought in to implement UN peacekeeping mandates with little influence on decisions. It will likely widen the gap between the expectations from troops and their deployment experiences. Second, classifying troop performance into compartments breeds prejudice, and a misplaced arrogance amongst western troops towards their non-western counterparts, and withholds due recognition of the latter’s contribution.Footnote98

Examples abound when western troops such as the Italians in Mozambique; and the Belgians in Rwanda have been ineffective compared with their Global South counterparts. In South Sudan more recently, the Mongolian troops are well-recognized as by far the most effective.Footnote99 There is therefore a strong need to acknowledge that the disparity in performance cannot be enforced simply through stricter accountability measures, it requires acknowledging that national interests interact with labour hierarchies in important ways. These dynamics can and often do undermine the expectations that troops must deliver in alignment with the UN’s mandate.Footnote100 The gap between perceptions, expectations and experiences is an important area for the study of peacekeeping attitudes through the lens of labour hierarchies. Our study offers preliminary evidence and identifies an important area for future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the military officers who took part in this research and the military leadership on the Advanced Command and Staff Course (2017-2018) for supporting this study. An earlier draft of this paper benefited from comments by David Curran, Mats Berdal, two anonymous referees, and panellists at the ISA-Asia Pacific conference held at Singapore in July, 2019.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sukanya Podder

Sukanya Podder (PhD Post War Recovery Studies, University of York, UK) is a Reader in Post War Reconstruction and Peacebuilding at the Defence Studies Department, King’s College London. Her book Peacebuilding Legacy: Programming for Change and Young People’s Attitudes to Peace is forthcoming with Oxford University Press.

Giuseppe Manzillo

Giuseppe Manzillo, Senior Consultant at the World Bank is based at Washington D.C. He is currently a PhD candidate, Defence Studies Department, King’s College London.

Notes

1 Boutellis, “Burden-sharing,” 200.

2 Weiss and Kuele, “The Global South and UN.”

3 Blocq, “Western Soldiers,” 290.

4 Tanner, “Addressing the Perils”.

5 Fisher, “Failed State in Somalia”.

6 Bellamy and Williams, “The West and Contemporary Peacekeeping,” 39–57.

7 Cunliffe, Legions of Peace.

8 Boutton and D’Orazio, “Buying Blue Helmets”.

9 Malone and Thakur, “Racism in Peacekeeping,” 30.

10 Bode and Karlsrud, “Implementation in Practice”.

11 Brahimi, “Report of the Panel on the United Nations.”

12 Berdal, “The Security Council and Peacekeeping,” 26.

13 Tanner, “Addressing the Perils,” 215.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Amvane, “United Nations Peacekeeping,” 466–7.

17 Ibid.

18 Malone and Thakur. “UN Peacekeeping: Lessons Learned?” 11–17.

19 Comments made by Cedric de Coning, Senior Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), 11 November, 2019.

20 UN News, “Improving Performance”.

21 Di Razza, “The Accountability System,” 1.

22 Dobbie, “Post-Cold War Peacekeeping,” 121–48.

23 Crano and Prislin, “Attitudes and Persuasion,” 347.

24 Di Salvatore and Ruggeri, “Effectiveness of Peacekeeping Operations”.

25 Henry, “Parties and Pests,” 373.

26 Henry, “Peacexploitation,” 21; see also, Razack, Dark Threats and White Knights.

27 Janowitz, The Professional Soldier, 419.

28 Moskos, The Peace Soldiers.

29 Galtung and Hveen, “Participants in Peacekeeping,” 37.

30 Tomforde, “Role of Culture”.

31 Battistelli, “Post-modern Soldier”.

32 Hedlund and Soeters, “Reflections on Self-image,” 411.

33 Reed and Segal, “Multiple Deployments,” 58–9.

34 ibid.

35 Segal and Meeker, “Warfighting,” 171–3.

36 Sion, “Sweet and Innocent,” 462.

37 Rubinstein, “Cross-cultural”, 29–30; 35.

38 Fetherston and Nordstrom, “Overcoming Habitus”.

39 Mackinlay, A Guide to Peace Support Operations.

40 Ruffa, “Think and Do,” 199–200.

41 Albrecht and Cold-Ravnkilde. “National Interests as Friction,” 204–20.

42 Tesser, “Attitude Change,” 289–90.

43 Wilen and Heinecken, “Peacekeeping Deployment Abroad,” 236–53.

44 Segal and Meeker, “Warfighting,” 174–5.

45 Thomas et al., “Serving in Bosnia,” 376–80.

46 Miller, “Hate Peacekeeping,” 438.

47 Bartone, Adler, and Vaitkus, “Pyschological Stress,” 587; Segal and Tiggle, “Citizen-soldiers,” 383–4.

48 Thomas et al., “Serving in Bosnia,” 378; Moskos, “Constabulary Ethic”; Segal and Segal, American Participation.

49 Miller, “Hate Peacekeeping,” 438.

50 Reed and Segal, “Multiple Deployments,” 74–5.

51 Rubinstein, “Cross-cultural,” 25.

52 Coleman, “Incentivizing Effective Participation”; Boutellis, “Burden-sharing”, 200.

53 Berdal, “The Security Council and Peacekeeping”; Duursma, “Counting Deaths,” 823–47; Karlsrud, “The UN at War,” 40–54.

54 The ACSC trains and educates British Officer from all three services (Army, Navy and Air force) and military students from 57 other nations’ armed forces.

55 Interview with the ACSC Course Director, 20 January 2018.

56 Andrade, “Online Surveys,” 575.

57 United Nations, “Country Rank Report”.

58 This distribution is consistent with deployed troops where, in fact, middle-level officers such as Majors and Captains constitute the core leadership of such units (Lieutenants are too young and still need training before operational deployment, whereas Colonels are too senior and their presence in the field is just limited to the commanding role). Note however, by the time the students enrolled, they were almost all of Lieutenant Colonel rank.

59 Segal and Tiggle, “Attitudes of Citizen-soldiers,” 388.

60 Ben-Ari and Elron, “Blue Helmets,” 272.

61 Rubinstein, “Imperial Policing”, 462; Albrecht and Cold-Ravnkilde, “National Interests as Friction”.

62 Ben-Ari and Elron, “Blue Helmets,” 281.

63 Malone and Thakur, “Racism in Peacekeeping”; Ruffa, “What Kind of Military Leadership”; Berdal and Ucko, “Use of Force,” 6–12.

64 Berdal, “Command and Control,”13–14.

65 Duffey, “Cultural Issues,” 147–8.

66 Ibid.

67 Fetherston and Nordstrom, “Overcoming Habitus,” 106.

68 Ruffa, “What Peacekeepers Think”.

69 Matsumoto and Fletcher, “Cross-national Differences in Disease Rates, 112.

70 Bartone, Adler, and Vaitkus, “Dimensions of Psychological Stress,” 589.

71 Ibid., 589–90.

72 Leck, “International Responsibility,” 346.

73 Alcott, Smith, and Dee, Peacekeeping in East Timor, 69.

74 Bullion, “India in Sierra Leone,” 77–91.

75 Leck, “International Responsibility,” 6.

76 Holmes, “Situating Agency,” 57.

77 Dorn, “Blue Beret,” 414; Shetler-Jones, “Intelligence,” 517–27; Duursma and Karlsrud, “Predictive Peacekeeping”.

78 Dallaire and Sarty, “Shake Hands,” 445.

79 Duursma, “Counting Deaths,” 826.

80 Ibid.

81 Andersen, “HIPPO in the Room,” 343–61.

82 Duursma and Karlsrud, “Predictive Peacekeeping,” 2.

83 Kuele and Cepik, “Intelligence Support,” 44–68.

84 Bove, Ruffa, and Ruggeri, Composing Peace, 115–6.

85 Dallaire and Beardsley, Shake Hands, 177.

86 DPKO, “Principles and Guidelines”.

87 Bove and Ruggeri, “Kinds of Blue”.

88 Fjelde, Hultman, and Nilsson, “Protection through Presence,” 103–31.

89 Berdal and Ucko, “The Use of Force”.

90 Williams, “Protection, Resilience and Empowerment,” 287–98; Lilly, “Changing Nature of Protection,” 628–39.

91 Wills, Protecting Civilians.

92 Rhoads and Welsh, “Close cousins,” 597–617.

93 Fortna and Howard, “Pitfalls and Prospects,” 283–301.

94 Mahamba, “Rebels Kill 15 Peacekeepers”.

95 Dirkzwager, Bramsen, and Van Der Ploeg, “Factors Associated with Posttraumatic Stress,” 37–51.

96 Bartone, Adler, and Vaitkus, “Dimensions of Psychological Stress,” 587.

97 Amvane, “United Nations Peacekeeping,” 466–7.

98 Kabilan, “Third World Peacekeepers,” 56–76.

99 Interview, UK based peacekeeping expert, 30 July 2020.

100 Tanner, “Addressing the Perils,” 211.

Bibliography

- Albrecht, Peter, and Signe Cold-Ravnkilde. “National Interests as Friction: Peacekeeping in Somalia and Mali.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14, no. 2 (2020): 204–220.

- Alcott, Louisa May, Michael Geoffrey Smith, and Moreen Dee. Peacekeeping in East Timor: The Path to Independence. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003.

- Amvane, Gabriel. “United Nations Peacekeeping and the Developing World.” Swiss Review of International & European Law 28 (2018): 465–487.

- Andersen, Louise Riis. “The HIPPO in the Room: The Pragmatic Push-back from the UN Peace Bureaucracy Against the Militarization of UN Peacekeeping.” International Affairs 94, no. 2 (2018): 343–361.

- Andrade, Chittaranjan. “The Limitations of Online Surveys.” Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 42, no. 6 (2020): 575–576.

- Bartone, Paul T., Amy B. Adler, and Mark A. Vaitkus. “Dimensions of Psychological Stress in Peacekeeping Operations.” Military Medicine 163, no. 9 (1998): 587–593.

- Battistelli, Fabrizio. “Peacekeeping and the Postmodern Soldier.” Armed Forces & Society 23, no. 3 (1997): 467–484.

- Beardsley, Brent, and Romeo Dallaire. Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Toronto: Random House Canada, 2003.

- Bellamy, Alex J., and Paul D. Williams. “The West and Contemporary Peace Operations.” Journal of Peace Research 46, no. 1 (2009): 39–57.

- Ben-Ari, Eyal, and Efrat Elron. “Blue Helmets and White Armor Multi–Nationalism and Multi–Culturalism among UN Peacekeeping Forces.” City & Society 13, no. 2 (2001): 271–302.

- Berdal, Mats. “The United Nations System of Command and Control of Peacekeeping Operations.” The International Spectator 31, no. 1 (1996): 13–24.

- Berdal, Mats. “The Security Council on Peacekeeping.” In The United Nations Security Council and War. The Evolution of Thought and Practice Since 1945, eds. Teoksessa V. Lowe, A. Roberts, J. Welsh, and D. Zaum, 175–204. Oxford: OUP, 2010.

- Berdal, Mats, and David H. Ucko. “The Use of Force in UN Peacekeeping Operations: Problems and Prospects.” The RUSI Journal 160, no. 1 (2015): 6–12.

- Blocq, Daniel. “Western Soldiers and the Protection of Local Civilians in UN Peacekeeping Operations: is a Nationalist Orientation in the Armed Forces Hindering Our Preparedness to Fight?” Armed Forces & Society 36, no. 2 (2010): 290–309.

- Bode, Ingvild, and John Karlsrud. “Implementation in Practice: The Use of Force to Protect Civilians in United Nations Peacekeeping.” European Journal of International Relations 25, no. 2 (2019): 458–485.

- Boutellis, Arthur. “Rethinking UN Peacekeeping Burden-sharing in a Time of Global Disorder.” Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 13 (2020): 193–209.

- Boutton, Andrew, and Vito D’Orazio. “Buying Blue Helmets: Western Aid Allocation & UN Peacekeeping Troop Contributions.” Unpublished Manuscript, 2013.

- Bove, Vincenzo, Chiara Ruffa, and Andrea Ruggeri. Composing Peace: Mission Composition in UN Peacekeeping. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Bove, Vincenzo, and Andrea Ruggeri. “Kinds of Blue: Diversity in UN Peacekeeping Missions and Civilian Protection.” British Journal of Political Science 46, no. 3 (2015): 681–700.

- Brahimi, Lakhdar. Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (A55/305-S/2000/809, August 21, Annex), 2000.

- Bullion, Alan. “India in Sierra Leone: A Case of Muscular Peacekeeping?” International Peacekeeping 8, no. 4 (2001): 77–91.

- Cil, Deniz, Hanne Fjelde, Lisa Hultman, and Desirée Nilsson. “Mapping Blue Helmets: Introducing the Geocoded Peacekeeping Operations (Geo-PKO) Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 57, no. 2 (2020): 360–370.

- Coleman, Katherina P. “The Political Economy of UN Peacekeeping: Incentivizing Effective Participation”. Providing for Peacekeeping No. 4. International Peace Institute. May 2014.

- Crano, William D., and Radmila Prislin. “Attitudes and Persuasion.” Annual Review of Psychology 57 (2006): 345–374.

- Cunliffe, Philip. Legions of Peace: UN Peacekeepers from the Global South. London: CH Hurst & Co., 2013.

- Dallaire, Romeo, and Roger Sarty. “Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda.” International Journal 59, no. 2 (2004): 445–449.

- Di Razza, Namie. “The Accountability System for the Protection of Civilians in the UN System”. International Peace Institute. December 2020.

- Dirkzwager, A. J. E., I. Bramsen, and Henk M. Van Der Ploeg. “Factors Associated with Posttraumatic Stress among Peacekeeping Soldiers.” Anxiety, Stress & Coping 18, no. 1 (2005): 37–51.

- Di Salvatore, Jessica, and Andrea Ruggeri. “Effectiveness of Peacekeeping Operations.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Empirical International Relations Theories, ed. William R. Thompson New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Dobbie, Charles. “A Concept for Post-Cold War Peacekeeping.” Survival 36, no. 3 (1994): 121–148.

- Dorn, A. Walter. “The Cloak and the Blue Beret: Limitations on Intelligence in UN Peacekeeping.” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 12, no. 4 (1999): 414–447.

- Duffey, Tamara. “Cultural Issues in Contemporary Peacekeeping.” International Peacekeeping 7, no. 1 (2000): 142–168.

- Duursma, Allard. “Counting Deaths While Keeping Peace: An Assessment of the JMAC's Field Information and Analysis Capacity in Darfur.” International Peacekeeping 24, no. 5 (2017): 823–847.

- Duursma, Allard, and John Karlsrud. “Predictive Peacekeeping: Strengthening Predictive Analysis in UN Peace Operations.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 8, no. 1 (2019). doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/sta.663 (accessed March 11, 2021).

- Fetherston, Anne Betts, and Carolyn Nordstrom. “Overcoming Habitus in Conflict Management: UN Peacekeeping and War Zone Ethnography.” Peace & Change 20, no. 1 (1995): 94–119.

- Fisher, J. “AMISOM and the Regional Construction of a Failed State in Somalia.” African Affairs 118, no. 471 (2019): 285–306.

- Fjelde, Hanne, Lisa Hultman, and Desirée Nilsson. “Protection Through Presence: UN Peacekeeping and the Costs of Targeting Civilians.” International Organization 73, no. 1 (2019): 103–131.

- Fortna, Virginia Page, and Lise Morjé Howard. “Pitfalls and Prospects in the Peacekeeping Literature.” Annual Review of Political Science 11 (2008): 283–301.

- Galtung, Johan, and Helge Hveem. “Participants in Peace-keeping Forces.” Cooperation and Conflict 11, no. 1 (1976): 25–40.

- Henry, Marsha. “Peacexploitation? Interrogating Labor Hierarchies and Global Sisterhood Among Indian and Uruguayan Female Peacekeepers.” Globalizations 9, no. 1 (2012): 15–33.

- Henry, Marsha. “Parades, Parties and Pests: Contradictions of Everyday Life in Peacekeeping Economies.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 9, no. 3 (2015): 372–390.

- High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) Report. Uniting Our Strengths for Peace: Politics, Partnership and People, UN Doc. A/70/95–S/2015/446, New York, 2015.

- Holmes, Georgina. “Situating Agency, Embodied Practices and Norm Implementation in Peacekeeping Training.” International Peacekeeping 26, no. 1 (2019): 55–84.

- Janowitz, Morris. The Professional Soldier. A Social and Political Portrait. Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1960.

- Karlsrud, John. “The UN at War: Examining the Consequences of Peace-enforcement Mandates for the UN Peacekeeping Operations in the CAR, the DRC and Mali.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2015): 40–54.

- Krishnasamy, Kabilan. “‘Recognition’ for Third World Peacekeepers: India and Pakistan.” International Peacekeeping 8, no. 4 (2001): 56–76.

- Kuele, Giovanna, and Marco Cepik. “Intelligence Support to MONUSCO: Challenges to Peacekeeping and Security.” The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs 19, no. 1 (2017): 44–68.

- Leck, Christopher. “International Responsibility in United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Command and Control Arrangements and the Attribution of Conduct.” Melbourne Journal of International Law 10 (2009): 346.

- Lilly, Damian. “The Changing Nature of the Protection of Civilians in International Peace Operations.” International Peacekeeping 19, no. 5 (2012): 628–639.

- Mackinlay, John, “A Guide to Peace Support Operations.” In Institute for International Studies, ed. Thomas J. Watson Jr., Providence: Rhode Island, Brown University, 1996.

- Mahamba, Fiston. “Rebels Kill 15 Peacekeepers in Congo in Worst Attack on U.N. in Recent History.” REUTERS, December 8, 2017, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-congo-un/rebels-kill-15-peacekeepers-in-congo-in-worst-attack-on-u-n-in-recent-history-idUKKBN1E21YO (accessed April 10, 2020).

- Malone, David, and Ramesh Thakur. “Racism in Peacekeeping.” The Globe and Mail. 2001.

- Malone, David M., and Ramesh Thakur. “UN Peacekeeping: Lessons Learned?.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 7 (2001): 11–17.

- Matsumoto, David, and D. Fletcher. “Cross-national Differences in Disease Rates as Accounted for By Meaningful Psychological Dimensions of Cultural Variability.” Journal of Gender, Culture, and Health 1, no. 1 (1996): 71–81.

- Miller, Laura L. “Do Soldiers Hate Peacekeeping? The Case of Preventive Diplomacy Operations in Macedonia.” Armed Forces & Society 23, no. 3 (1997): 415–449.

- Moskos, Charles C. Peace Soldiers: The Sociology of a United Nations Military Force. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

- Polman, Linda. We Did Nothing: Why the Truth Doesn't Always Come Out When the UN Goes in. London: Penguin UK, 2013.

- Razack, Sherene. Dark Threats and White Knights: The Somalia Affair, Peacekeeping, and the New Imperialism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

- Reed, Brian J., and David R. Segal. “Th1e Impact of Multiple Deployments on Soldiers’ Peacekeeping Attitudes, Morale, and Retention.” Armed Forces & Society 27, no. 1 (2000): 57–78.

- Rhoads, Emily Paddon, and Jennifer Welsh. “Close Cousins in Protection: The Evolution of Two Norms.” International Affairs 95, no. 3 (2019): 597–617.

- Rubinstein, Robert A. “Cross-Cultural Considerations in Complex Peace Operations.” Negotiation Journal 19, no. 1 (2003): 29–49.

- Rubinstein, Robert A. “Peacekeeping and the Return of Imperial Policing.” International Peacekeeping 17, no. 4 (2010): 457–470.

- Ruffa, Chiara. “What kind of Military Leadership for What Kind of Operation? Assessing ‘Mission Command’ in Peace Operations and Counterinsurgencies.” In Leadership in Challenging Situations, eds. Harald Haas, Franz Kernic, and Andrea Plaschke, 183–194. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Publishing Group, 2012.

- Ruffa, Chiara. “What Peacekeepers Think and Do: An Exploratory Study of French, Ghanaian, Italian, and South Korean Armies in the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon.” Armed forces & society 40, no. 2 (2014): 199–225.

- Ruffa, Chiara. “Military Cultures and Force Employment in Peace Operations.” Security Studies 26, no. 3 (2017): 391–422.

- Segal, David R., and Barbara Foley Meeker. “Peacekeeping, Warfighting, and Professionalism: Attitude Organization and Change Among Combat Soldiers on Constabulary Duty.” JPMS: Journal of Political and Military Sociology 13, no. 2 (1985): 167.

- Segal, David R., and Mady Wechsler Segal. Peacekeepers and their Wives: American Participation in the Multinational Force and Observers. No. 147. Praeger, 1993.

- Segal, David R., and Ronald B. Tiggle. “Attitudes of Citizen-soldiers Toward Military Missions in the Post-Cold War World.” Armed Forces & Society 23, no. 3 (1997): 373–390.

- Shetler-Jones, Philip. “Intelligence in Integrated UN Peacekeeping Missions: The Joint Mission Analysis Centre.” International Peacekeeping 15, no. 4 (2008): 517–527.

- Sion, Liora. ““Too Sweet and Innocent for War”? Dutch Peacekeepers and the Use of Violence.” Armed Forces & Society 32, no. 3 (2006): 454–474.

- Tanner, Fred. “Addressing the Perils of Peace Operations: Toward a Global Peacekeeping System.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 16, no. 2 (2010): 209–217.

- Tesser, Abraham. “Self-generated Attitude Change.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 11, 289–338. Academic Press, 1978.

- Thomas, Samantha, Christopher Dandeker, Neil Greenberg, Vikki Kelly, and Simon Wessely. “Serving in Bosnia Made Me Appreciate Living in Bristol: Stressful Experiences, Attitudes, and Psychological Needs of Members of the United Kingdom Armed Forces.” Military Medicine 171, no. 5 (2006): 376–380.

- Tomforde, Maren. “Introduction: The Distinctive Role of Culture in Peacekeeping.” International Peacekeeping 17, no. 4 (2010): 450–456.

- United Nations. “Troop Contributions: Country Rank Report.” 2018, https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/2_country_ranking_report.pdf (accessed March 11, 2021).

- United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO). United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines, March 2008, https://www.refworld.org/docid/484559592.html (accessed June 15, 2020).

- UN News. “UN Evaluates Progress in Improving Peacekeeping Performance.” December 6, 2019. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/12/1052941 (accessed March 12, 2021).

- Weiss, Thomas G., and Giovanna Kuele. “The Global South and UN Peace Operation.” E-International Relations, 2019, https://www.e-ir.info/2019/02/03/the-global-south-and-un-peace-operations/ (accessed February 12, 2020).

- Wilén, Nina, and Lindy Heinecken. “Peacekeeping Deployment Abroad and the Self-perceptions of the Effect on Career Advancement, Status and Reintegration.” International Peacekeeping 24, no. 2 (2017): 236–253.

- Wills, Siobhán. Protecting Civilians: The Obligations of Peacekeepers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.