ABSTRACT

The UN may sanction peacekeeping operations (POs) to neutralize armed groups and promote democratization. This research presents perceptions from beneficiaries of assistance related to POs and relations between local women/girls and peacekeepers within two post-colonial contexts: the DRC and Haiti. Using cross-sectional, mixed-methods data collected in Haiti (2017) and the DRC (2018), we performed a comparative secondary analysis to better understand similarities and differences by country and gender in how participants perceived peacekeepers. Congolese participants were more likely to perceive foreign UN personnel as ‘able to offer financial support’, compared to Haitian participants who were more likely to perceive the UN personnel as ‘in a position of authority’ and ‘able to offer protection’. Overall response patterns indicated that both Haitian and Congolese perceived the peacekeeper as responsible for initiating interactions with local women/girls. However, some variations were noted: Congolese male participants were most likely to perceive UN personnel as the initiators of interactions with local women and girls, compared to Haitians and Congolese females, who were more likely to perceive local women and girls as the initiators. Our research presents a locally grounded understanding of how locals perceive POs and peacekeepers relative to their communities and women and girls.

Abbreviations::

- BAI: Bureau des Avocats Internationaux

- DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo

- ETS: Enstiti Travay Sosyal ak Syans Sosyal

- KOFAVIV: Komisyon Fanm Viktim pou Viktim

- MARAKUJA: Multidisciplinary Association for Research and Advocacy in the Kivus by United Junior Academics

- MINUJUSTH: The United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti

- MINUSTAH: The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti

- MONUC: The United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo

- MONUSCO: The United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- PO: Peace Operation

- SEA: Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

- SOFEPADI: Solidarité Féminine Pour la Paix et le Développement Intégral

- TPCC: Troop and police contributing countries

- UN: United Nations

- WWII: World War II

Introduction

Since the end of WWII, United Nations (UN) peace operations (POs) have led international conflict intervention and peace building efforts.Footnote1 Robust stabilization missions are POs that are authorized to use force and may also include broader liberalized peacebuilding agendas that involve democratization, market-based economic reform, and integration into globalization as mechanisms to promote peace between democratic nations.Footnote2 Two examples of POs focused on democratization alongside stabilization are The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH: 2004-2017) and The United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO: 2010-Present).

The reputation and legacy of MINUTAH and MONUSCO have been tarnished by reported cases of peacekeeper misconduct, including inappropriate use of lethal force, sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA), and abandoning their paternal responsibilities when conceiving peacekeeper-fathered children.Footnote3 Further, in Haiti, UN peacekeeping troops were found to be the source of a cholera epidemic that resulted in over 10,000 reported deaths.Footnote4 Human rights abuses occur within a context of broader militarization which extends military weapons, influence, ideologies, and identities into civilian life, the economy, and socio-political institutions.Footnote5 This paper examines how local beneficiaries of assistance perceive peacekeepers vis-à-vis women and girls who live in proximity to robust stabilization-focused POs in Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Our analysis focuses on Haiti and the DRC as comparative case studies to better understand how local civilians living in post-colonial and peacekept countries perceive women and girls’ interactions with peacekeepers. We begin with an overview of the colonial legacies of Haiti and the DRC to understand the context in which robust stabilization missions enter and operate.

Haiti and the DRC: Post-Colonial Countries with Diverging Conflict Histories

Under French colonial rule (1659–1804) and through African slave labour, Haiti became a major international supplier of coffee, sugar, indigo, and cacao and the world’s most profitable colony.Footnote6 After becoming the first republic led by Black slaves to gain independence from colonial rule, Haitian sovereignty was hindered by punitive policies. Such policies included France’s imposition of a colossal ‘independence tax’, the US occupation in the 19th-twentieth century, the implementation of conditional lending agreements, and structural adjustment programmes that crippled the Haitian economy and eroded the legitimacy of public service and governance.Footnote7

More recently, many Haitian heads of state have relied on paramilitaries to maintain political power and suppress opposition,Footnote8 thereby further engendering violence and insecurity, including coups. MINUSTAH was sanctioned in 2004 to address the overthrowing of President Aristide and was operational for 13 years until 2017. During MINUSTAH’s course on 12 January 2010, an earthquake of 7.0 magnitude with its epicenter near the capital city of Port-au-Prince led to approximately 300,000 deaths and the internal displacement of over one million people.Footnote9 MINUSTAH was then replaced by a smaller PO, The United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH), until 2019.Footnote10 In 2023, the UN security council authorized a non-UN, international mission led by Kenya to address the elevated levels of violence and human rights violations since MINUSTAH and MINUJUSTH.Footnote11

DRC’s history is similarly tumultuous. Belgian’s colonial rule (1908–1960) was marked by slavery and exploitation of the country’s natural resources. Post-1960 independence was also characterized by ongoing conflict and political instabilityFootnote12 with loss of existing infrastructure (railroads, highways, and industry) as well as stalled development. In the midst of the massive refugee crisis resulting from the 1994 Rwandan genocide came the First (1996–1997)Footnote13 and Second Congo Wars (1998–2003) which included Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Rwanda and Uganda.Footnote14 The Lusaka ceasefire agreement was signed in July of 1999, and the Security Council established the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUC) to observe the ceasefire and disengagement of forces.Footnote15 In 2010, the PO transitioned to The United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), with a mandate to protect civilians, support humanitarian and human rights defenders, and assist the Government in its stabilization and peace consolidation.Footnote16 MONUSCO continues today as the world’s second largest PO with 14,000 military personnel, 660 military observers, 591 police personnel and 1,050 members of formed police.Footnote17

Although both Haiti and the DRC share colonial histories, the UN sanctioned POs in response to different forms of insecurity. MINUSTAH’s presence was in response to civil unrest and instability in the form of armed criminal gangs that operated with impunity in Haiti.Footnote18 In contrast, the DRC has experienced armed conflict between warring nations and parties for over two decades. Despite the diverging nature of conflict, both Haiti and the DRC have experienced prolonged internal conflict, creating protracted state fragility.Footnote19

Gendered Consequences of Robust Stabilization Missions Within Host Communities

Both MONUSCO and MINUSTAH peacekeepers have been involved in the delivery of humanitarian aid, such as medical care and food, which often fall under the purview of ‘women’s’ household responsibilities.Footnote20 Given that some humanitarian efforts intersect more directly with women’s domestic gender roles, the militarization of humanitarian aid creates spaces for gendered power dynamics to manifest as coercive interactions between well paid and predominantly male, militarized peacekeepers and local women/girls in need of material assistance. The inherent gendered power hierarchies can manifest as sexual and exploitation and abuse (SEA), sometimes involving minors and the exchange of humanitarian aid for sexual activity.Footnote21 While it is important to recognize that sexual exploitation and abuse can occur among both genders, including men and boys,Footnote22 the reality is that women and girls are disproportionately affected both in terms of prevalence and pregnancy-related consequences. While we note that men and boys are also affected by SEAFootnote23, in the current work the focus was women and girls.

The scarcity of socio-economic opportunities and social safety nets contributes to insecurity in both DRC and Haiti. Consequently, women and girls often engage in small-scale business opportunities to generate income.Footnote24 The trading and selling of everyday goods (coffee, fufu, soap, shoes, clothing, etc.) enables women and girls with little or no educational qualifications to enter the informal economy and attain income and resources.Footnote25 The presence of peacekeepers magnifies precarious forms of labour performed by women and girls in the absence of social protections that can prevent or mitigate exploitation.Footnote26 For example, the magnification of sex industries and transactional sex have been documented, alongside the preferential hiring of young and sexually attractive women in administrative roles.Footnote27

While scholarship has examined the geo-political and colonial dimensions of peacekeeping and related misconduct,Footnote28 less attention has been given to the micro-level perceptions of peacekeepers and PO that are informed by everyday interactions between locals and peacekeepers. The lived experiences of hosting POs and subsequently navigating militarized spaces is the focus of the present analysis.

Purpose

We present local civilian understandings of UN peacekeeping, relations between local women/girls and peacekeepers, and everyday interactions with peacekeeping personnel within two post-colonial contexts: the DRC and Haiti. We focus on how local beneficiaries of assistance (both males and females) perceive and understand interactions between local women and girls and UN peacekeepers in one context of gang-related insecurity and natural disasters (Haiti) and the other in the context of armed conflict (DRC). To compare experiences and perceptions, we first disaggregated results by country (Haiti and DRC). Given the militarized nature of robust POs, the gendered manner through which women and girls interact with peacekeepers, and the documented occurrence of SEA primarily affecting women and girls,Footnote29 we considered the gender of local community members to be an important factor to consider in addition to country. Therefore, within each country, we also considered gender differences by stratifying response patterns by male and female respondents.

Methods

Survey Implementation

This research is based on field work conducted by the research team in partnership with local community-based organizations in Haiti (2017) and the DRC (2018) (Refer to Appendix 3). Our studies involved the collection of qualitative micro-narratives (short stories shared in relation to a prompt) from local male and female community members about women/girls’ interactions with UN peacekeepers and subsequent quantitative data on how participants interpreted their shared micro-narratives (Refer to Appendix 4). We conducted a secondary data analysis of the original mixed-methods cross-sectional studies conducted in HaitiFootnote30 and in the DRC.Footnote31

Haiti

In Haiti, the cross-sectional survey was administered in Kreyòl using the SenseMaker app installed on iPad Mini 4s. The research team led a four-day training for research assistants from two Haitian community partner organizations: Komisyon Fanm Viktim pou Viktim (KOFAVIV) and Enstiti Travay Sosyal ak Syans Sosyal (ETS). Two KOFAVIV research assistants who worked with survivors of gender-based violence, who were able to provide referral services during data collection, and 10 undergraduate social work students from ETS assisted in data collection. Using convenience sampling, the research assistants recruited Haitians over the age of 11 years within a 30 km radius of 11 selected MINUSTAH bases (Cité Soleil, Charlie Log Base, Tabarre, Léogâne, Cap Haiïtien, Saint Marc, Gonaïves, Morne Cassé, Fort Liberté, Hinche, and Port Salut).

DRC

In the DRC, two local organizations – Multidisciplinary Association for Research and Advocacy in the Kivus by United Junior Academics (MARAKUJA) and Solidarité Féminine Pour la Paix et le Développement Intégral (SOPFEPADI) – implemented the study in Swahili and Lingala using SenseMaker on iPad mini 4s. MARAJUKA supported data collection logistics and SOFEPADI, as a women’s advocacy organization, provided contextual expertise and referral services. The research assistants attended a 5-day research training. The research assistants recruited a convenience and snowball sample of Congolese participants over the age of 13 within a 30 km radius of 6 MONUSCO peacekeeping bases in Eastern DRC (Kisangani, Bukavu, Goma, Benia, Bunia, and Kalemie).

Participant Recruitment

Across both countries, the research assistants approached prospective participants within community settings including, markets, commercial settings, and transportation hubs. Both MINUSTAH and MONUSCO bases were purposively selected based on their years of operation, size, and troop and police contributing countries (TPCC), as well as geographic (including rural and urban regions). Female participants were primarily interviewed by female research assistants and male participants were primarily interviewed by male research assistants. It was considered important to include adolescents because evidence suggests that young girls are affected by sexual exploitation and abuse and other peacekeeper misconduct. A variety of participant subgroups were recruited through convenience sampling including family members and friends of individuals who had interacted with peacekeepers, individuals who had interacted with peacekeepers, as well as other community members and leaders.

Instruments and Measures

The cross-sectional surveys were conducted using SenseMaker: a narrative-based research methodology and mixed-methods data collection tool that extracts meaning from short narratives (called micro-narratives, referring to brief experience or story shared by participants in response to the open-ended prompts).Footnote32 Using SenseMaker large numbers of short micro-narratives related to a topic of interest are collected to understand complex phenomena. SenseMaker methodology bridges the gap between large sample survey data and case studies.Footnote33

In both the DRC and Haiti, the SenseMaker survey began with an open-ended prompt asking participants to share a story about a woman or girl in their community in relation to UN peacekeeping or peacekeepers. These prompts did not mention peacekeeper misconduct or SEA and there was no further probing by the research assistants. This approach enabled stories about SEA to emerge more naturally from the broader landscape of experiences and did not require that participants speak about SEA.

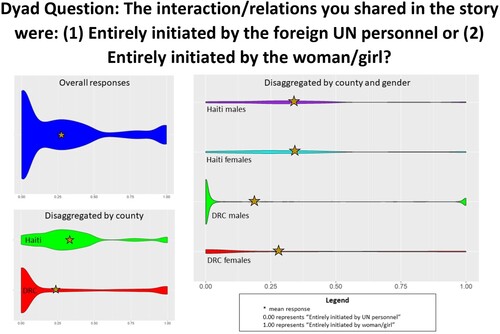

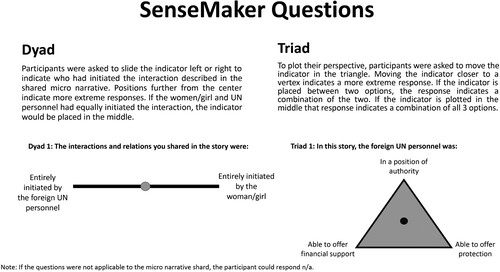

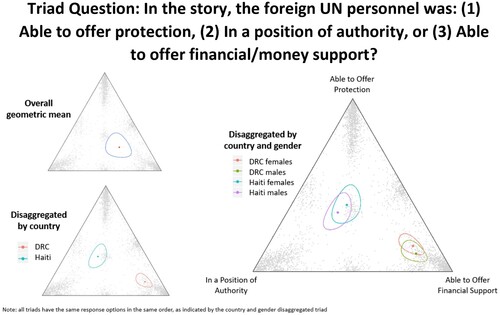

After audio recording short micro-narratives (usually between 1 and 3 min in length) that were later transcribed, participants were asked to self-interpret their experiences. Accordingly, participants expressed their feelings, attitudes, and perspectives by responding to a series of quantitative analytical questionsFootnote34 that involved plotting their perspectives spatially between a spectrum of dichotomous extremes (dyads) or three possible options (triads) (Refer to ). To reduce social desirability bias, all response options within a given triad or dyad had the same emotional tone: neutral, negative, or positive. SenseMaker then assigned quantitative values to the plotted self-interpretations. Participants also answered multiple choice questions pertaining to participant demographics and micro-narrative characteristics (i.e. emotional tone, importance of the micro-narrative, frequency of occurrence, etc.).

Figure 1. SenseMaker Questions.

Haiti

Haitian community partners from KOFAVIV, ETS, and Bureau des Avocates Internationaux (BAI) worked collaboratively with SAB and SL to develop the SenseMaker survey questions. The survey was originally drafted in English, then translated to Kreyòl and independently back translated to English. Language discrepancies were resolved through translator consensus. In March of 2017, the survey was pilot tested in Haiti among 54 participants who provided feedback on how to further refine the survey for greater clarity.

DRC

For the DRC, the SenseMaker survey was developed in English with representatives from SOFEPADI as well as the research team. The English survey was translated to Lingala and Swahili and independently back translated to English. Additionally, in January 2018 the survey was pilot tested in the DRC among 24 participants to improve clarity and further refine the instrument.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the Haiti study protocol was obtained from the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (6020398; 6023714) and the University of Birmingham’s Ethical Review Board (ERN_16–0950). Prior to data collection, KOFAVIV and BAI advised that there were no national legislative requirements to obtain Haitian research ethics review.Footnote35 The DRC study protocol was obtained from Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (6019042) and the Congolese National Committee of Health Ethics (001/DP-SK/119PM/2018).

Research assistants introduced the study in local languages using a standard script and informed consent was obtained prior to beginning the survey. The research assistants did not record identifying information and conducted the survey in private settings. Participants indicated consent by tapping a consent box on the tablet. Written consent was waived given there were no questions about SEA and participants could share any narrative they wanted. Adolescents were included because they were known to be exposed to SEAFootnote36, and it would have been unethical to exclude their perspectives. Parental consent for the inclusion of minors was not sought; adolescents were considered mature minors and involving parents would likely have introduced bias and risk for parental conflict and/or abuse if the SEA was not disclosed to the parents.Footnote37 Team members from KOFAVIV and SOFEPADI were onsite to offer immediate support and referral mechanisms were in place for any participant requiring ongoing assistance. No compensation was provided. All completed surveys were uploaded from the tablets to a secure server and then were permanently deleted from the tablets.

Analysis

Quantitative Descriptive

The present analysis focuses on SenseMaker triad and dyad questions that were common between the Haiti and DRC surveys. Quantitative response patterns among the selected triads and dyads were stratified by setting and gender (Haitian males, Haitian females, Congolese males, and Congolese females). For the triads, the average response pattern for each stratified group was computed using the geometric mean. The geometric mean is a measure of central tendency that is conceptualized as a single coordinate that could replace all data points while keeping the overall product of the data values unchanged.Footnote38 The geometric mean was used (rather than the more commonly used arithmetic mean or average) because data coordinates within triads are normalized. Each triad data point is represented by three coordinates (x, y, z), which are ratio lengths, and sum to 1.0.Footnote39 The ratio length coordinates are calculated by first computing the distance between the point to each triangle side length and then taking the ratio between each length to the total sum of the lengths. Since only two of the three coordinates representing a plotted point are independent, the geometric mean must be used as the arithmetic mean would yield misleading results.Footnote40 The position of the geometric mean represents the spread of the location and clustering of responses, relative to the three triad vertices. Using R scripts (R V.3.4.0) 95% confidence ellipses were also generated for each geometric mean. If the 95% confidence ellipses surrounding the geometric means did not overlap, the responses of the stratified groups were statistically different.

For the dyads, data were first graphically represented using histograms. Due to non-normal response distributions, non-parametric descriptive statistics were computed. In SPSS, the independent samples Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare the dyad distribution responses between Haiti and the DRC, at an alpha level of 0.05. Further, the independent samples Kruskal–Wallis H test determined if there were any statistically significant differences by country and gender, at an alpha level of 0.05. When significant findings using the Kruskal–Wallis H test were detected, Dunn’s test was used post-hoc to identify any pairwise differences among the 4 stratified groups. Using the Bonferroni correction, the significance level for the pairwise comparisons was adjusted for multiple tests. To visually depict dyad response patterns among the groups stratified by country and participant gender, violin plots were constructed. An asterisk indicates the mean response per stratified group.

Qualitative Contextualization

Utilizing a sequential exploratory design for this mixed-methods research, the quantitative descriptive findings provided a framework for the qualitative analysis. Micro-narratives in the direction of significant response patterns (by country and/or gender) within the triads and dyads were exported, read to gain an understanding of the overall essence of the shared experiences and perceptions, and considered for inclusion. LV and SB engaged in critical dialogue with respect to micro-narrative selection, ensuring that the analysis was sensitive to the literature base in this area. The research team was also intentional about identifying which aspects of the data were most pertinent to the experiences of Congolese and Haitian women/girls, as reflected by the initial prompting questions. Illustrative micro-narratives composed of thick descriptions were selected from participants within each stratification group (Congolese males, Congolese females, Haitian males, and Haitian females) to help contextualize the quantitative findings. We present quotes from the micro-narratives that (i) represented plotted perceptions in the direction of the statistically significant findings from the quantitative analysis, (ii) reflected experiences/concepts across the were shared across micro-narratives rather than expressed in an idiosyncratic manner, and (iii) were described with sufficient detail and clarity.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In total, 2451 micro-narratives were shared by Haitian participants and 2856 micro-narratives were shared by Congolese participants. Of the total sample with non-missing values for gender (n = 5394), 33.43% were Haitian males, 27.72% were Congolese females, 25.21% were Congolese males, and 13.64% were Haitian females (Refer to Appendix 1 and Appendix 2).

displays the demographic and micro-narrative characteristics among participants. All demographic variables differed between the DRC and Haiti samples. Compared to the Haiti sample, a greater proportion of participants in the DRC were female, young adults (18–24-year-old participants), married/living with their partner or separated from their spouse/divorced, had achieved either the lowest levels of education (no formal education and some primary school) or the highest (some or completed post-secondary school), and reported being ‘well off’ financially. Similarly, the micro-narrative characteristics also differed between the two country samples. Micro-narratives about family members and micro-narratives interpreted as having a strongly negative or negative emotional tone were more likely to be shared by Congolese participants, compared to Haitian participants. In contrast, personal micro-narratives and micro-narratives interpreted as having a strongly positive emotional tone were more commonly shared by Haitian participants, compared to Congolese participants.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Triad 1: The Perceived Positionality of the Peacekeeper

The first triad asked participants to consider, in relation to the shared micro-narrative, whether the foreign UN or MONUSCO/MINUSTAH personnel was: (i) able to offer protection, (ii) in a position of authority, or (iii) able to offer financial/money support. The overall geometric mean was closest to ‘offer financial/money support’ halfway between ‘able to offer protection’ and ‘position of authority’ ().

Figure 2. Geometric mean for triad question with surrounding 95% confidence ellipses, stratified by country and gender.

The overall geometric mean indicates participants perceived the foreign UN/MOUSCO personnel in the direction of being able to ‘offer financial/money support’. Haitian participants were more likely to identify the UN/MINUSTAH personnel as ‘offering protection’ and ‘being in a position of authority’, compared to Congolese participants, who answered predominantly in the direction of ‘able to offer financial support’. There were no significant differences between male and female respondents within each country. Refer to Appendix E for additional information regarding the triad question.

Micro-Narratives from Congolese Participants Interpreted in Direction of ‘Able to Offer Financial Support’

Congolese participants who perceived the UN/MONUSCO personnel as ‘able to offer financial support’ described peacekeeping economies wherein some Congolese were employed by peacekeepers or through POs. Some Congolese participants who had received material resources from peacekeepers were able to later resell the items. For example, one man (aged 35 to 44) from Goma described:

Something beneficial for us about MONUSCO presence here is the fact that they often give out food and non-food items to their local agents and the latter do easily help us in one way or another when they also go to sell those items to community people at fair/low prices. It really helps many locals who even start their commercial business and family economy that way [NarrID 2828].

Micro-narratives of peacekeepers employing locals were also shared. However, employment opportunities were not evenly distributed. Sometimes MONUSCO-related employment engendered animosity between Congolese who were able to secure employment though peacekeeping economies and Congolese who were unemployed. For example, one female participant from Bukavu (aged 25–34) highlighted divisions between Congolese who benefited from peacekeeping economies and Congolese who did not reap the same financial resources: We hate our brothers who work for MONUSCO, for they are very stingy and not cooperative [NarrID 1394].

Even if inequitable, MONUSCO-related employment opportunities were generally described in favourable terms as having the potential to improve one’s quality of life. Thus, employment opportunities made available through peacekeeping economies were coveted. For example, one male from Bunia (aged 18–24) stated:

Every day he could meet the workers of MONUSCO, he would appear the best among MONUSCO workers, they were providing him with telephones and his life became better [NarrID 1001].

They earn much [more] money and use that for entertainment whereas our husbands are paid 100$, but they earn about 1000$ and get 100$ every week as a bonus … When they get their bonus, they start going round in the quarter. For nobody can refuse money if he has no food to eat. That’s the reason why we have plenty of prostitutes due to the presence of MONUSCO [NarrID 1235].

The seemingly ‘formal’ employment of Congolese women and girls at local MONUSCO bases was also described in relation to sexual abuse and exploitation, wherein the employment offer was sometimes contingent on sexual activity. One female from Goma (aged 18–24) shared:

I was going to MONUSCO camp to meet with those women working for them. When I saw them, I asked them to plead for me so that I could start working there. They asked me if I had ever tried to be sex professional. I told them that when I finished primary school, I met my husband when I was 13 years old. I had my first child at 14 years of age, my husband died after we had 4 children … They [the women] ensured me that the only thing that can push someone to get a job, is to accept having sex with them [the peacekeepers] … I was astonished; many women working for them are at the same time their wives [NarrID: 2158].

Micro-Narratives from Haitian Participants Interpreted as a Balanced Perspective Between ‘Offering Protection’ ‘Financial Supports’ and ‘Being an Authority’

Haitians whose responses indicated that UN personnel offered protection, financial support, and authority in equal measure had mixed feelings about the presence and role of MINUSTAH peacekeepers. Many shared micro-narratives that contained both positive and negative impacts of the PO. On one hand, some Haitians recognized that MINUSTAH peacekeepers contributed to greater security and law enforcement. However, the widespread knowledge of SEA and the cholera outbreak tarnished the PO’s reputation in Haiti. For example, a male participant from Hinche (aged 25–34) mentioned that while peacekeepers assisted with a law enforcement matter, they were also implicated in sexual abuses:

If the MINUSTAH was not present, the country would have been worse than it is in term of insecurity … MINUSTAH helps the police because the police have no equipment nor vehicles, they have nothing … But the bad side was that people are saying that the MINUSTAH was involved in homosexuality with boys and girls and sexually attacking children and women [NarrID 1937].

In relation to peacekeeping economies, Haitians explained how peacekeepers created jobs. However, employment opportunities were contrasted with the adverse consequences of the cholera epidemic, as described by one male in Hinche (aged 25– 34):

The presence of MINUSTAH in the country was good for some people, just like there are some people that it did not benefit at any point. Because primarily, when they arrived in the country they created jobs, many people found jobs … But in my opinion, what shocked me is the cholera outbreak that they said came about because the MINUSTAH brought it with them. Although I was not affected, but I had people close to me that were affected. It hurts me [NarrID 1862].

One day, there was a fight between neighborhoods … Shots were being fired, so the MINUSTAH came, brought some peace and restored order … Throughout the day MINUSTAH patrolled to provide security and prevented additional disturbances [NarrID 1237].

I don't know if everyone else is aware of the happiness I feel about MINUSTAH's presence … I gained knowledge beyond my years through [working] with MINUSTAH. My profession has allowed me to make a lot of money … But with UN presence through MINUSTAH, like we are saying their support is more than 10,000 times more effective for Haiti [than the government or the National Police Force]. The reason: the National Police is committing more crimes, while MINUSTAH offer support with what they have … We all need these benefits from MINUSTAH. So, I don't know, I am just trying to point out the reality. To the current Haitian Government [officials] who are listening and [want] to do it alone … MINUSTAH has a place in Haiti [NarrID613].

The biggest frustration is the issue of communication … They do not understand us, we do not speak the same language, we do not use the same communication codes … When there are protests, they do not understand the peaceful demonstrations we are holding. They shot at us many times … They do not know what we are saying when we are talking to them, and some gestures that we are making is not understood by them and can cause them to shoot at us at any time [NarrID 1068],

After the American occupation we used to see people mulattos but without knowing their father … So, this phenomenon is not new in the country, but also, I do not see what great thing that these people brought to the country … Many children are born, they can go to search, many children are born again, many mulattoes have adopted the signature of their mother since they do not know their father. After becoming pregnant for these soldiers, these soldiers leave and leave victims after their departure. These women victims may not have any recourse or assistance to complain, or to testify all these things in radio stations because it would be in vain. It is useless to do this because we are not going to find these guilty soldiers. [Narr ID 1274]

Dyad 1: Who Initiated Interactions with Peacekeepers

The first dyad asked participants to indicate whether the interactions shared in the story were (i) ‘entirely initiated by foreign UN personnel’ (value of 0) or (ii) ‘entirely initiated by the woman or girl’ (value of 1). The shape of the violin plot in illustrates the overall distribution of responses. The mean value among all participants was 0.273 (standard deviation: 0.320, Ntotal: 4135), indicating that overall, the MINUSTAH/MONUSCO peacekeepers were perceived as being more likely to have initiated the interactions or relations mentioned in the micro-narrative.

As depicted in , the response patterns for Haiti and the DRC differed. Congolese participants (mean = 0.230, standard deviation = 0.357, N = 2410) were less likely to respond in the direction of ‘entirely initiated by the woman or girl’ compared to Haitian participants (mean = 0.333, standard deviation: 0.248, N: 1725) (Mann–Whitney U standardized test statistic: −23.108, p-value = 0.00). When disaggregated by country and participant gender, multiple pairwise comparisons were statistically significant. Of note, significant differences were noted between the response patterns of Congolese females (mean: 0.271, standard deviation: 0.356, N: 1338) and Congolese males (mean: 0.179, standard deviation: 0.352, N: 1072) (Dunn’s test statistic: 10.491, p = 0.00). This indicates Congolese females were more likely to respond in the direction of ‘entirely imitated by the woman or girl’ compared to Congolese men. Further, the response pattern among Congolese females was also statistically different from Haitian males (mean: 0.332, standard deviation: 0.243, N: 1236) (Dunn’s test statistic: 13.715, p = 0.00) and Haitian females (mean: 0.336, standard deviation: 0.261, N: 487) (Dunn’s test statistic: 9.997, p = 0.00). Haitians (male and female) were the most likely to indicate that interactions/relations were ‘entirely initiated by the woman/girl’, followed by Congolese females, and Congolese males.

Male Congolese Participants who Interpreted Micro-narratives in Direction of ‘Entirely Initiated by the Foreign UN Personnel’

Congolese men who interpreted micro-narratives in the direction of ‘entirely initiated by the foreign UN personnel’ spoke about the experiences of female SEA victims, who were their family members, friends, or neighbours. Some Congolese men highlighted the exploitative nature of SEA relations, coercion tactics employed by peacekeepers to enact SEA with girls below the age of 18 years, and the negative consequences of peacekeepers’ eventual departure from the DRC. For example, a male from Bunia (aged 25–34) shared a micro-narrative about an internally displaced adolescent girl in his neighbourhood who conceived a child with a MONUSCO peacekeeper, within the context of food insecurity:

I know a girl who … had a baby with a MONUSCO soldier from Uruguay. That girl made a baby in this circumstance: firstly, after [the] war, all her relatives ran and left while she was 14 or 15 years. As internally displaced people were going to look at white people to beg [for] bread and so on. At that time, Uruguay soldiers were there. That soldier fell on the girl and made her pregnant as they were having intimate relations regularly. When the girl gave birth, that man used to come visit his child because he was an officer [NarrID 58].

For young ladies, they know that after being hired, they will easily be having sexual intercourse with them. They consider ladies as less reasonable creatures. Young ladies rely on money, they think that as MONUSCO men are sent by UN, they should have much money. They are paid by MONUSCO men, they pay each $100 or $50 as wage. Young ladies are misled because of MONUSCO men [NarrID 194].

In other cases, women and girls’ vulnerability was obscured by the perceived material ‘advantages’ of transactional sexual relations with peacekeepers. A male participant from Beni (aged 18–24) described a situation wherein a girl was employed as a housemaid for a MONUSCO peacekeeper. The employment relationship became intertwined with SEA. However, the male participant perceived this situation as ‘advantageous’ given that the girl was able to keep the peacekeeper’s furniture and received pay after his departure:

There was a girl who was working as a housemaid at a MONUSCO agent's residence. That man at first was considering her as his housemaid, but with time, he started having intimate relations with her. In reality, we took advantage of him. He was at a given time supposed to go to his country, so he left the girl with all the house furniture, and he gave her some amount of money to help her do something lest she suffers the consequences of joblessness. I personally considered that situation as an advantage [NarrID 85].

Sometimes these whites ask us to go and find women for them. They promise to give us 5 and 20 dollars for the woman in case we succeed to bring one. Many girls or women often agree. When a woman has agreed to come, we always lead them to MONUSCO base where they have their sex deal and come back. All these whites behave that way. [NarrID 1570]

Those MONUSCO agents always pick them from here at university and go with them in guest houses, luxurious restaurants, and good hotels. When for example, one girl comes back, and students want to provoke her, she is ready to say, ‘I have a boyfriend of mine who works at MONUSCO who gives me 200 to 300 dollars every two months … I always go to restaurants and eat whatever I want, so he will pay. You guys cannot do [that]. In addition, that man pays my academic fees and buys me everything I want. Even if he doesn't have money when I call him, he can take out a loan provided that he satisfies me. You students have nothing’ [Narr ID 59].

When I was living in [X], there was a beautiful girl who was living nearby our place. I was feeling like I could date her. So, a certain guy informed me that that girl goes out with a MONUSCO agent. The guy told me that … I did not have financial means to provide for her; he told me that once a MONUSCO agent falls in love with a girl, he spends so much money on the girl. He discouraged me to not continue longing for the girl [NarrID 1712].

That man fell in love with a girl up to the time he took her to South Africa where they lived both before going to Cape Verde where they are living now … When that man left for his country, three months later, he sent some money to the girl to fill all the necessary requirements like visa, air ticket to join him. In addition, he came back to Congo to give the dowry to the family of the girl. She joined him there. She had her wedding ceremony in South Africa … Not only MONUSCO have wrong deeds in their achievements, but also, they have good ones [NarrID 230]

Female Congolese Participants Who Interpreted Micro-Narratives in the Direction of ‘Entirely Initiated by Woman/Girl’

Most micro-narratives shared by Congolese women/girls that were interpreted as ‘entirely initiated by the woman/girl’ mentioned SEA. Female community members mentioned that women/girls traveled to the MONUSCO base to exchange sexual activity for money. For example, an adolescent female participant (aged 13–17) from Bukavu stated: ‘At the MONUSCO camp, there are ladies who often go there to meet the agents of MONUSCO. They take off their clothes to get money’ [NarrID 864].

Sexual activity was also exchanged for gifts and food, which could be re-sold by women/girls for a profit. Another female participant from Bukavu (aged 13–17) described this practice, emphasizing the seemingly ‘active’ participation of women/girls who experience SEA:

The guys of MONUSCO give money to girls who accept to show them their breasts. Those girls who refuse to show their breasts are not forced, especially when their chief is around. When the chief is absent, they do stupid things like asking girls to show their breasts in exchange for gifts, food, money. The women who are selling items near the camp are acquainted with them. They get so many things from the camp of MONUSCO that they retail [NarrID 236].

I fell in love with a Malawian, who had a sexual intercourse with me by force, [and] I got pregnant with him. In that way [of] getting pregnant, he left me with a pregnancy, I stayed with pregnancy, and I’ve given birth. The baby is here and he is now one year and three months old. I am here alone, there is nobody to help me it is myself only [1247, Goma].

All those women who have been selling things there have had children they made with those white men. Today, they have been looking for the so-called Pakistani and Uruguayan husbands, but they cannot see them anymore. I also know a girl who always goes out with these whites. I always see her with them, almost every day. We sometimes catch her and some of her friends undressed in front of those guys, with their bras only. [NarrID1707]

Many girls here are very apparently beautiful, but their main activity here has remained prostitution only. Some of them have abandoned school and started doing harlotry. They are sinking their own lives in many awful things/behaviors. MONUSCO guys and locals who work for them have all made children with our sisters. [NarrID 2265]

Haitian Participants Who Interpreted Micro-Narratives as ‘Entirely Initiated by Woman or Girl’

Like Congolese females, several micro-narratives shared by Haitians that were interpreted as ‘entirely imitated by the woman/girl’ mentioned SEA. In some cases, friends of women/girls who had children fathered by peacekeepers mentioned that the implicated women and girls immigrated or relocated to a different country:

I have lived a story where I had a friend who was dealing with MINUSTAH. There was one of the MINUSTAH who loved her; MINUSTAH took good care of her. For now, she is not in Haiti anymore. MINUSTAH sent her in another country with an only child that she has with him. For now, she is not in Haiti. [NarrID 357, female in Port-au-Prince aged 18–24]

There is kind of Haitian when they see foreigners come in the country, they always want to be in contact with them although the MINUSTAH have been in the country for a long time. Besides where I live, people always want to keep in touch with them, especially women. Sometimes they have sex with them without knowing if they do not have an illness. Sometimes there were cases that happened, and we never expected, for example when the girls became pregnant for foreigners and then they are afraid to explain or have guts to say that [NarrID 957].

The ladies were trying to feed themselves that they ended up in such situation. They offer themselves to the MINUSTAH so they can get something in return. The MINUSTAH on the other hand, since they are the ones that came to them, they enjoyed it. I think that, if it wasn’t for hardship, the ladies would never have done these things with the MINUSTAH. The parents have failed them. [NarrID 1670]

Discussion

Using data collected in Haiti (2017) and the DRC (2018), we conducted a comparative secondary data analysis to better understand differences and similarities by country and gender with respect to (i) how UN peacekeepers were perceived and (ii) who initiated interactions between peacekeepers and local women/girls. In both Haiti and the DRC, participants’ micro-narratives shed light on how civilian interactions with peacekeepers occur in militarized social spaces that include gendered exchanges of ideas, experiences, emotions, money, and services.Footnote41 In exploring the gender-specific opportunities and interactions created through POs, we expand and apply the peacekeeping economy concept,Footnote42 the human rights violation of SEA,Footnote43 and local perceptions of peacekeeping operations.Footnote44 Our analysis of ‘everyday’ interactions between peacekeepers and Haitian and Congolese community members contributes a contextual understanding of the gendered power asymmetries at play and how these interactions are perceived to be economically beneficial but also exploitative, particularly for women and girls. Similar to Beber et al (2019),Footnote45 our data emphasize that peacekeeping missions are ‘economic forces’ and that gendered power structures and ideologies create short-term opportunities for economic gain,Footnote46 that are unrelated to long-term tangible improvements in security and democratization.

Drawing from our data, gendered power structures and ideologies play out in distinct ways regarding peacekeepers, local men and boys, and local women and girls. Adopting a macro-level, scholars have described peacekeeping as both gendered and colonial.Footnote47 Men from the global south predominantly perform the ‘dirty work’ of peacekeeping while ideologies from the global north inform liberalized and robust peacekeeping agendas, focused on the market liberalization and democratization through military intervention and force.Footnote48 This gendered and colonial aspect of peacekeeping is less invested in creating what Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel have deemed as ‘sustainable peace’ which involves the formation of ‘peace economies’ that work to reduce structural economic inequalities and sustainably improve citizen livelihoods.Footnote49 For instance, Haitian participants spoke positively about MINUSTAH peacekeepers restoring order during armed conflict, the provision of jobs related to the PO, and peacekeepers use of vehicles to patrol communities alongside the police. Yet, these short-term improvements in peace did not equate to sustainable peace via the reduction of structural and gendered inequalities.

As our data and the scholarship reflect, interactions between peacekeepers and local women and girls are motivated by a lack of gender equitable socio-economic opportunities.Footnote50 The influx of foreign male peacekeepers in post-colonial settings strongly signals the potential for economic gain, even if short term, for both local men and women. In our data, both men and women spoke about formal and informal employment opportunities at local peacekeeping bases and the commercial practice of selling food and non-food items from peacekeepers to local community members. However, the means through which local men and women gain access to peacekeeping economies is gendered.

Economic gain from foreign peacekeepers signals a gendered performance that may have short term income gains but is ultimately deleterious in the long term.Footnote51 Gendered and racialized stereotypes create space for women and girls to access resources from peacekeeping economies. In our data, participants mentioned that women seeking employment at local peacekeeping bases were asked to engage in sexual activity. Further, women and girls’ engagement in transactional sex with peacekeepers allowed them to gain access to resources even if unemployed. Drawing from the scholarship of Jennings (2019), peacekeepers perceive local women and girls in Haiti, DRC, and Liberia as ‘easy’, ‘prostitutes’, and ‘dirty’.Footnote52 Given that money flows from peacekeepers to locals (and not the other way around), local women and girls are recognized as dispensable sexual objects by peacekeepers, who will implicitly exchange sex for payment (gifts, clothes, food, cellphones, school fee payment, aid), even in coerced or pressured circumstances.Footnote53 Some women and girls may be able to leverage this perception for economic gain, particularly if they are young and ‘attractive’.Footnote54 Whatever agency is expressed by women and girls who choose to engage in transactional sex and reap short-term economic benefits, the macro-level geo-political context cannot be ignored. Transactional sex, sex work, and other sexual/romantic interactions exist in spaces where women and girls have fewer opportunities for socio-economic advancement, in part due to the global north’s focus on robust and liberalized peacekeeping agendas.Footnote55

As reflected in our data, men can position themselves in different ways relative to peacekeepers. For example, sometimes men and boys are brokers of sexual interactions involving local women and girls, recognizing that male peacekeepers have more access to capital that can be used to ‘attract’ women. In our data young men mentioned receiving money from peacekeepers to recruit women and girls for them. Further, compared to women, it is more likely that local men may be employed by peacekeepers as security, local interpreters, or contractors without the assumption that they will engage sexually with them, thereby boosting their masculine role as household income earners.Footnote56 This masculinity hierarchy reflects differences in disposable income and relative wealth, with peacekeepers being perceived as having the material means to better take care of women and girls compared to local men and boys. Both male and female participants in our data reflected on the higher earnings of peacekeepers; at times local men and boys felt threatened by this financial differential, noting they could not compete with peacekeepers for the romantic attention of local women and girls.

The global north’s lack of investment in sustainable peace economies that mitigate the feminization of poverty creates unique gendered power hierarchies between peacekeepers, local men/boys, and local women/girls. Young local women and girls who can access capital from peacekeeping economies via transactional sex or sex work can question local masculinities by drawing attention to what resources or experiences peacekeepers can provide (payment of school fees, restaurant excursions, cash gifts, hotel excursions). When local men/boys cannot economically compete with peacekeepers for women and girls’ romantic or sexual attention, feelings of resentment against local women/girls or peacekeepers may ensue. However, whatever short term income gains are made by women and girls, are moot compared to the victim blaming and stigma women/girls who engage in sex with peacekeepers face and the social and economic fallout of bearing a child with a peacekeeper.Footnote57

In summary, the economic position of foreign male peacekeepers relative to local men and women in post-colonial contexts signals the potential for economic gain. Women and girls’ racialized and gendered identities are inextricably connected to local peacekeeping economies. While women and girls who exchange sex are able to more readily tap into peacekeeping economies, leading to the emasculation of local men and boys, the long-term socio-economic realities and skills of women and girls are not changed via transactional sex. The risk of pregnancy, victim blaming, and troop withdrawal can potentially leave women and girls in more dire circumstances, compared to men and boys.Footnote58

Next, we draw attention to two key findings from our data and connect them to local contexts in Haiti and the DRC. First, Congolese participants were more likely to perceive foreign UN personnel as ‘able to offer financial support’, compared to Haitian participants who were more likely to perceive the UN personnel as ‘in a position of authority’ and ‘able to offer protection’. Second, Congolese male participants were most likely to perceive UN personnel as the initiators of interactions with local women and girls, compared to Haitians and Congolese females, who were more likely to perceive local women and girls as the initiators.

Perceptions of Peacekeepers’ Positionality

That Congolese participants were more likely to perceive foreign UN personnel as ‘able to offer financial support’ rather than ‘in a position of authority’ and ‘able to offer protection’ is line with a previously documented critique that MONUSCO was not providing the level of protection expected of a PO.Footnote59 A reoccurring theme among the Congolese micro-narratives was the perception that peacekeepers were direct sources of income and material goods, rather than protection/security. As previously explored by other scholars,Footnote60 peacekeeping economies refer to economic activity that is bolstered in terms of frequency or pay due to the presence of POs and peacekeepers. When peacekeepers or POs employ local civilians, gender-specific opportunities and access to resources arise. For example, local civilians may fill positions related to the mission itself (translators, intelligence, security), maintaining households (security, domestic staff, gardening), or meeting leisure and recreation demands (hospitality industry, grocery staff, sex work and transactional sex).Footnote61

Following Congolese ethos of ‘débrouillardisme’ (understood as the ability to cope, including improvisational methods of survival),Footnote62 Congolese participants described the practice of reselling food and non-food items given to them by peacekeepers. This practice was mentioned in relation to starting an income generating business. Another manifestation of ‘débrouillardisme’ may be transactional sex.Footnote63 Transactional sex illustrates both the gendered dimension of informal peacekeeping economies and the ethos of ‘débrouillardisme’.

As studied outside of peacekeeping contexts,Footnote64 love and material exchange are entangled in post-colonial Africa. The habitual gift giving practices of men are associated with expectation (or hope) that sexual activity or love will follow. This material exchange entangled with sex and love characterize transactional relations that are a part of the broader landscape of informal economies in fragile settings. Given the wider feminization of poverty and the lack of opportunities for women and girls to attain paid employment in the formal sector, transactional sexual relationships present an opportunity for Congolese women and girls to attain resources for survival, upward social mobility, or modernity and luxury.Footnote65 However, employment through POs or peacekeepers was not without challenges. For example, women were expected to engage in sexual activity in order to secure employment and/or were expected to have sex as part of their employment. Further, some Congolese participants described feelings of animosity and envy toward community members who were able to secure employment related to UN peacekeeping given that formal employment opportunities were coveted but not equitably distributed.

While in Haiti similar practices of transactional sex exist, we observed that micro-narratives shared by Haitians were more multifaceted. For example, some micro-narratives merged both positive and negative perceptions of MINUSTAH:Footnote66 often micro-narratives mentioned peacekeeper-perpetrated abuses alongside improvements in security and law enforcement or positively perceived employment opportunities. Such micro-narratives reflect MINUSTAH’s documented achievements in neutralizing armed gangs,Footnote67 contrasted against abuses and misconduct including the Nepalese contingent introducing cholera, which resulted in an epidemic and significant mortality with few reparations.Footnote68 Misconduct also included six Uruguayan peacekeepers involved in sexually abusing an adolescent boy and three police peacekeepers from Pakistan who sexually abused an adolescent boy with a cognitive disability.Footnote69 Despite such documented human rights abuses, some Haitians participants did share positive experiences, describing how they benefited economically and professionally from formal employment with PO above and beyond what would have been possible in Haiti in the absence of the PO.

Further, micro-narratives also reflected tensions between Haitians and foreign actors. Since gaining independence from French Colonial rule in 1804, Haiti has experienced longstanding history of protest in parallel with communal collaboration, rooted in struggles for self-determination.Footnote70 For example, ethnographic research explored the Haitian practice of protest for change in parallel with konbit: the kinship relations grounded in an ethos if radical collaboration and democracy grounded in mutual aid and collective labour.Footnote71 We noted that participants described MINUSTAH’s focus on militarization and use of force as eroding the capacity for Haitians to practice konbit and peaceful protest. As noted by Doucet et al.,Footnote72 ‘Haitians are fully aware of the social issues that impact their lives … [and] are fully knowledgeable about the methods for handling such situations’; lasting change requires partnership not paternalism. Moreover, some Haitian participants perceived MINUSTAH to be an extension of the US marine occupation of Haiti (1915–1934), reflecting a geo-political context wherein foreign intervention in Haiti runs along the lines of US imperialism.Footnote73 As was referenced by one Haitian participant, ‘mulatto’ children are not new; US marines fathered children during the US occupation of Haiti and peacekeepers continued to father children during MINUSTAH.Footnote74

Perceptions of Who Initiated Interactions with Peacekeepers

The second key finding was that Congolese male participants were most likely to perceive UN personnel as the initiators of interactions with local women and girls, compared to Haitians and Congolese females, who were more likely to perceive local women and girls as the initiators. Micro-narratives shared by Congolese men mentioned the positionality of peacekeepers as formal/informal employers of women and girls, providers of material or financial resources used to ‘attract’ local women and girls, and the potential husbands/spouses of Congolese women. This perceived positionality not only reflects peacekeepers’ roles in ‘initiating’ interactions with local women and girls but also highlights tensions between Congolese men and MONUSCO peacekeepers regarding access to economic resources and masculinity norms.

Feelings of inferiority were also expressed by Congolese men who felt they could not financially compete with peacekeepers to attain the attention of local women and girls. Given that peacekeepers are well-paid in relation to the average local man, the influx of peacekeepers likely altered the existing informal economy of transactional sex in the DRC.Footnote75 For example, in our data participants spoke about MONUSCO peacekeepers having more disposable income to spend on transactional relationships and could financially ‘outcompete’ local Congolese men. This differential access to capital may lead to feelings of inferiority among Congolese men, within a context wherein the more economically successful a man is, the more likely he is able to secure multiple sexual partners. For example, scholarship has highlighted that some Congolese men seek multiple concurrent partners to display masculinity and that transactional encounters with women and girls may involve love, sex, and money, thereby meeting men’s perceived ‘need’ for sex and women’s perceived ‘need’ for money.Footnote76

Some micro-narratives shared by Congolese men highlighted the nuanced vulnerability of local women and girls regarding exploitative transactional sex. For example, some Congolese men mentioned that the wider context of internal displacement and food insecurity magnified power hierarchies between local women/girls and MONUSCO peacekeepers, creating a context wherein vulnerability to exploitation was magnified. Previous research conducted in Haiti also illustrated that internal displacement following natural disasters such as the 2010 earthquake and hurricane Matthew increased vulnerability to transactional sex and sexual exploitation perpetrated by peacekeepers, wherein humanitarian aid was exchanged for sexual activity.Footnote77 Domestic labour was connected to SEA in that peacekeepers leveraged informal, unregulated, and unsupervised employer-employee relationship to commit SEA.Footnote78 Adolescent Congolese males also benefited financially from transactional sex and SEA by acting as ‘intermediaries’ who recruited women and girls for MONUSCO peacekeepers.

Other Congolese men described specific ‘perks’ made available to women and girls who worked in a domestic capacity for peacekeepers. One advantage was immigration to the peacekeeper’s country of origin following marriage and payment of a dowry. While such cases of immigration or marriage between peacekeepers and local women occur and are referenced in UN documents,Footnote79 they are uncommon and potentially damaging given that they perpetuate a romanticization of transactional sex that can obscure power hierarchies, exploitation, and SEA reporting.Footnote80

Female Congolese participants were more likely to indicate that local women and girls had initiated interactions with peacekeepers. Unlike micro-narratives shared by male Congolese participants, some female Congolese participants included personal experiences of raising peacekeeper-fathered children. It is unclear whether participants indicated they (the woman or girl in the story) initiated the interaction because of the peacekeeper’s eventual abandonment and the subsequent single motherhood or whether they were experiencing internalized stigma. Other research conducted in both Haiti and the DRC illustrates that on account of the peacekeeper father’s repatriation and abandonment, raising a peacekeeper-fathered child is met with experiences of social stigma and discrimination due to the child’s mixed ethnicity, fatherlessness, perceived illegitimacy at birth, and lack of resources.Footnote81

Other female Congolese participants shared sentiments that may indicate varying degrees of victim blaming: devaluing and harmful acts that occur when victims of crimes (in this case SEA or paternal abandonment) are partially or entirely responsible.Footnote82 We noted some female Congolese participants felt local women and girls were described as wilful agents in ‘sinking their own lives’ by engaging in ‘harmful behaviors’ (i.e. transactional sex with peacekeepers) rather than attending school. Similarly, micro-narratives shared by Haitian participants also included victim blaming sentiments wherein local women and girls were described as ‘willfully’ seeking out foreign peacekeepers. Sometimes, this seemingly ‘deliberate’ choice was situated within the wider context of food insecurity.

Limitations

Our research has some limitations. First, due to the convenience sampling, findings are not nationally representative of Haiti or the DRC. However, given the recruitment strategy employed, the micro-narratives can be generalized to reflect the perspectives of Haitian and Congolese persons who are more likely to use public spaces that are located close to peacekeeping bases. Additionally, convenience sampling may have introduced sampling bias, thereby affecting the computed quantitative statistics. Differences in other demographic characteristics (i.e. region of data collection within Haiti/DRC or age) may have explained response patterns, above and beyond gender differences. Furthermore, our work examined experiences of SEA among women and girls and we acknowledge that the SEA experiences of men and boys, and indeed the communities perceptions of it, may differ. This is an area for future research. Lastly, the present analysis is a secondary analysis of an existing dataset; the original survey and recruitment strategy were not optimized to explore gender differences by country of data collection.

Conclusion

This mixed-methods research explored nuanced perceptions of women and girls’ experiences with UN peacekeepers, from Haitian and Congolese beneficiaries of assistance. Community members from the DRC viewed peacekeepers as offering financial support, compared to being ‘in a position of authority’ or ‘able to offer protection’. In comparison to DRC, MINUSTAH’s role in improving security in Haiti was more recognized by Haitian community members although MINUSTAH peacekeepers were also perceived as offering financial support and being in a position of authority. Overall, both Haitian and Congolese perceived the peacekeepers as initiating interactions with local women/girls, with some gender differences: Compared to Haitians and Congolese females, Congolese men were more likely to view peacekeepers as having initiated interactions with local women/girls and they often perceived that they were not able to compete with foreign peacekeepers for female partners given that the peacekeepers had more money and resources. Regarding the discourse on the broader social impacts of POs, our research contributes a locally grounded understanding of how beneficiaries of assistance perceive PO and peacekeepers.

Ethical Approval Statement

Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Birmingham (protocol ERN_16-0950; ERN_18-0083; ERN_17-1715), by the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (protocol 6020398; 6019042), and the Congolese National Committee of Health Ethics (CNES001/DP-SK/119PM/2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants in Haiti and the DRC who shared their experiences. Moreover, we are indebted to the research teams from KOFAVIV, BAI, ETS, SOFEPADI, and MARAKUJA who collected the data for the support and guidance in implementing this work and supporting interpretation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset that was collected in Haiti and supports the conclusions of this article is available in Figshare, [https://figshare.com/s/896ed7d25a1fa1a4a09b]. The dataset that was collected in the DRC is available upon reasonable request by contacting Dr. Susan Bartels.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Luissa Vahedi

Luissa Vahedi is an MSc trained social epidemiologist. Luissa is interested in conducting mixed-methods research to understand complex global health disparities affecting sexual/reproductive health and gender-based violence as well as leading rapid evidence generation for the purpose of policy action in fragile and humanitarian settings.

Sabine Lee

Sabine Lee is Professor of Modern History at the University of Birmingham. She hold degrees in history, mathematics and philosophy from Düsseldorf University, an M.Phil in International Relations and a PhD in history from Cambridge University. Her research has spanned a range of themes from post- war diplomatic history and twentieth century science history in interdisciplinary research on conflict and security with particular emphasis on conflict-related sexual violence and children born of war. She has led several international and interdisciplinary research projects funded by AHRC, Royal Society, Well-come Trust, the EU (FP7 and EU-H2020) and she has published extensively in these research fields

Stephanie Etienne

Stephanie Etienne is a GBV specialist/trainer. She has led and collaborated on several gender-based violence GBV prevention projects with national and international actors as well as the Haitian government. As part of her experiences, she has also worked closely with civil society organizations, in particular women’s and feminist organizations, leading actions to fight GBV at the national level and contributing to the development of synergy and better coordination of actions. As a social entrepreneur, she works towards the capacity building of women and girls, the promotion of female leadership, and financial empowerment.

Sandrine Lusamba

Sandrine Lusamba has more than 7 years of professional experience in community protection and public health system strengthening in areas of displacement and return within North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. She has expertise in gender, Woman Peace and Security, project management and holistic response to gender-based violence, including, reproductive health, child protection and community resilience.

Ms. Sandrine Lusamba is a human rights activist and defender, particularly for women and girls. She has been the National Coordinator of the NGO SOFEPADI since July 2020, and has worked with this organization in different roles: programme assistant (2014–2016) and communications officer (2016–2020).

Susan A. Bartels

Susan A. Bartels is a Clinician-Scientist at Queen’s University and Canada Research Chair in Humanitarian Health Equity. In addition to practicing emergency medicine, she conducts global public health research focused on how women and children are impacted by humanitarian crises. Dr. Bartels is interested in using innovative methods to improve understanding of health-related topics in complex environments such as armed conflict and natural disasters.

Notes

1 Dorn, “Intelligence-Led Peacekeeping”; Hegre, Hultman, and Nygåard, “Evaluating the Conflict-Reducing Effect.”

2 Newman, Paris, and Richmond, New Perspectives on Liberal Peacebuilding; Belloni, “Stabilization Operations and Their Relationship.”

3 Giles, “Criminal Prosecution of Un Peacekeepers”; Vahedi, Bartels, and Lee, “His Future Will Not Be Bright”; Wagner et al., “If I Was with My Father Such Discrimination Wouldn’t Exist, I Could Be Happy like Other People.”

4 Cravioto et al., “Final Report of the Independent Panel.”

5 Berman, “The Provision of Lethal Military Equipment”; Henry, “Parades, Parties and Pests”; Higate and Henry, “Engendering (in)Security in Peace Support Operations.”

6 Dupuy, Haiti: From Revolutionary Slaves.

7 Pierre-Louis, “Earthquakes, Nongovernmental Organizations, and Governance in Haiti”; Mullings, Werner, and Peake, “Fear and Loathing in Haiti”; [“Bausman and Frederick”], The Seizure of Haiti by the United States.

8 Carey, “Militarization Without Civil War.”

9 Government of the Republic of Haiti, “Action Plan for National Recovery and Development of Haiti.”

10 Peacekeeping, “MINUJUSTH: United Nations Mission for Justice Support.”

11 United Nations, “Security Council Authorizes ‘Historic’ Support Mission in Haiti.”

12 Reybrouck, Congo: The Epic History of a Peoplele.

13 Tull, “Peacekeeping in the Democratic Republic of Congo.”

14 Reybrouck, Congo: The Epic History of a Peoplele.

15 Peacekeeping, “MONUSCO Fact Sheet.”

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Perito and Robert, “Haiti: Confronting the Gangs of Port-Au-Prince.”

19 FAO et al., “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World”; Russo, “Militarised Peacekeeping.”

20 Davies and Rushton, “Healing or Harming?.”

21 Kolbe, “It’s Not a Gift When It Comes with Price”; Lee and Bartels, “They Put a Few Coins in Your Hand to Drop a Baby in You”; Fraulin et al., “It Was with My Consent since He Was Providing Me with Money”; Vahedi et al., “Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions”; Vahedi, Bartels, and Lee, “His Future Will Not Be Bright”; Vahedi et al., “The Distribution and Consequences of Sexual Misconduct.”

22 Ndulo, “The United Nations Responses to the Sexual Abuse”; Bartels, King, and Lee, “When It’s a Girl, They Have a Chance to Have Sex with Them.”

23 Bartels et al., “Participant and Narrative Characteristics Associated with Host Community Members.”

24 Evangelista and Rosa, “You Must Have People to Make Business.”

25 Ibid.

26 Jennings, “Peacekeeping as Enterprise.”

27 Edu-Afful and Aning, “Peacekeeping Economies in a Sub-Regional Context”; Jennings, “Service, Sex, and Security”; Jennings, “Peacekeeping as Enterprise.”

28 Henry, “Peacexploitation? Interrogating Labor Hierarchies and Global Sisterhood”; Henry, “Keeping the Peace.”

29 KONAMAVID and OFARC, “On the Abuse and Sexual Exploitation of Women, Girls, and Young Men.”

30 Lee and Bartels, “They Put a Few Coins in Your Hand to Drop a Baby in You”; Vahedi et al., “The Distribution and Consequences of Sexual Misconduct”; Vahedi et al., “Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions.”

31 Fraulin et al., “It Was with My Consent since He was Providing Me with Money”; Bartels, Lusamba, and Lee, “Participant and Narrative Characteristics Associated with Host Community Members.”

32 Hub, “Using Sensemaker® to Understand Girls’ Lives”; Lynam and Fletcher, “Sensemaking: A Complexity Perspective.”

33 Hub, “Using Sensemaker® to Understand Girls’ Lives.”

34 Ibid.

35 Publique, “Politique Nationale de Recherche En Santé”; Department of Health and Services, “International Compilation of Human Research Protections.”

36 UNHCR and Save the Children, “Sexual Violence & Exploitation.”

37 Weir, “Studying Adolescents without Parents’ Consent.”

38 Fleming and Wallace, “How Not to Lie with Statistics”; DeLong, “Statistics in the Triad, Part I.”

39 DeLong, “Statistics in the Triad, Part I”; DeLong, “Statistics in the Triad, Part II.”

40 Fleming and Wallace, “How Not to Lie with Statistics”; DeLong, “Statistics in the Triad, Part I.”

41 Oldenburg, “The Politics of Love and Intimacy in Goma, Eastern DR Congo.”

42 Jennings, “Conditional Protection?”; Jennings, “Peacekeeping as Enterprise”; Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel. “Economies of Peace”; Vogel, “The Economic Local Turn in Peace and Conflict Studies.”

43 Kolbe, “It’s Not a Gift When It Comes with Price.”

44 Sabrow, “Local Perceptions of the Legitimacy of Peace Operations by the UN, Regional Organizations and Individual States.”

45 Beber et al., “The Promise and Peril of Peacekeeping Economies.”

46 Kolbe, “It’s Not a Gift When It Comes with Price”; Jennings, “Peacekeeping as Enterprise”; Higate, Paul, and Marsha Henry. “Space, Performance and Everyday Security.”

47 Henry, “Keeping the Peace.”

48 Ibid.

49 Distler, Stavrevska, and Vogel, “Economies of Peace.”

50 Kolbe, “It’s Not a Gift When It Comes with Price”; Jennings, “Peacekeeping as Enterprise”; Jennings, “Conditional Protection?”

51 Beber et al., “The Promise and Peril of Peacekeeping Economies.”

52 Jennings, “Conditional Protection?”

53 Kolbe, “It’s Not a Gift When It Comes with Price.”

54 Ibid.

55 Henry, “Keeping the Peace.”

56 Jennings, “Conditional Protection?”; Jennings, “Peacekeeping as Enterprise.”

57 Vahedi et al. “It’s Because We are ‘Loose Girls’.”

58 Vahedi, Bartels, and Lee, “His Future will not be Bright.”

59 Murphy, “UN Peacekeeping in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.”

60 Edu-Afful and Aning, “Peacekeeping Economies in a Sub-Regional Context”; Jennings, “Service, Sex, and Security.”

61 Ibid.; Oldenburg, “The Politics of Love and Intimacy in Goma, Eastern DR Congo.”

62 Braun, “Débrouillez-Vous.”

63 Stoebenau et al., “Revisiting the Understanding of ‘Transactional Sex’ in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

64 Braun, “Débrouillez-Vous”; Zawu, “The Rise and Normalization of Blessee / Blesser Relationships in South Africa.”

65 Braun, “Débrouillez-Vous”; Stoebenau et al., “Revisiting the Understanding of ‘Transactional Sex’ in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

66 King et al., “MINUSTAH is Doing Positive Things Just as They Do Negative Things.”

67 Dorn, “Intelligence-Led Peacekeeping.”

68 Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, “Cholera 9 Years on … A ‘New Approach?’”; Bartels and Wisner, “Haiti’s Right to Remedy.”

69 Reiz and O’Lear, “Spaces of Violence and (In)Justice in Haiti.”

70 Dupuy, Haiti: From Revolutionary Slaves.

71 Elizabeth, “We Know How to Work Together.”

72 Doucet and Dublin, “Who Decides?”

73 Sommers, “The US Power Elite and the Political Economy of Haiti’s Occupation.”

74 Vahedi, Bartels, and Lee, “His Future Will Not Be Bright.”

75 Beber et al., “Peacekeeping, Compliance with International Norms.”

76 Lusey et al., “Conflicting Discourses of Church Youths.”

77 Vahedi, Bartels, and Lee, “Even Peacekeepers Expect Something in Return”; Luetke et al., “Hurricane Impact Associated with Transactional Sex.”

78 Vahedi et al., “The Distribution and Consequences of Sexual Misconduct.”

79 United Nations Secretariat, “Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation.”

80 Vahedi, Bartels, and Lee, “Even Peacekeepers Expect Something in Return”; Vahedi et al., “Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions.”

81 Vahedi et al., “It’s Because We Are ‘Loose Girls’.”; Wagner et al., “UNsupported: The Needs and Rights of Children”; Wagner et al., “If I was with My Father Such Discrimination Wouldn’t Exist.”

82 The Canadian Resource Centre, “Victim Blaming.”

References

- Bartels, Susan A., Carla King, and Sabine Lee. “When It’s a Girl, They Have a Chance to Have Sex With Them. When It’s a Boy … They Have Been Known to Rape Them”: Perceptions of United Nations Peacekeeper-Perpetrated Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Against Women/Girls Versus Men/Boys in Haiti.” Frontiers in Sociology 6 (2021): 173. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fsoc.2021.664294/full.

- Bartels, Susan Andrea, Sandrine Lusamba, and Sabine Lee. “Participant and Narrative Characteristics Associated with Host Community Members Sharing Experiences of Peacekeeper-Perpetrated Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” BMJ Global Health 6, no. 10 (2021): 1–12. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006631.

- Bartels, Susan A., and Sandra C. Wisner. “Haiti’s Right to Remedy and Health-an Urgent Call to Action.” The Lancet Regional Health - Americas (2022): 100236. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2022.100236.