Abstract

Consociational power sharing has become one of the leading mechanisms of governance introduced in deeply divided post-conflict societies. When communal divisions seem intractable, it is seen as a way to use these very divisions to reach an agreement and form a post-conflict government. Using post-2003 Iraq as a case study, this article critically examines consociation in practice. It argues that consociational power sharing is extremely valuable to reach an agreement, mitigate conflict, and form a post-conflict government. However, in Iraq, consociational power sharing has failed to meet the governance needs of the population, and although governments are formed, they do not necessarily govern. In a post-conflict society like Iraq with considerable development needs, failure of consociational governance has substantial negative impacts on the population. What this teaches us about consociation in Iraq is that it has a shelf life, because the governance needs continuously grow as a repercussion of them not being met and eventually reach the level where they outweigh the conflict-mitigating benefits of consociation.

Introduction

Consociational power sharing has been one of the leading mechanisms of conflict mitigation and governance introduced (often by external actors) in deeply divided post-conflict societies within the liberal peace framework.Footnote1 When communal divisions become intractable and feed conflict, consociational power sharing is seen as a way to use these very divisions to reach an (often enforced) peace agreement and form a post-conflict government. In established debates about the value of consociation, proponents of consociational power sharing argue it is essential to reach an agreement in a deeply divided society;Footnote2 opponents argue it entrenches the very divides it is meant to reconcile and degenerates into the primacy of identity politics.Footnote3 The academic debate so far has been fairly polarized and characterized by a lack of willingness for compromise between the intellectual starting point of both proponents and opponents.Footnote4 Case studies are often used to back up existing positions rather than to inform these positions.

There can be little argument against the fact that consociationalism leads to the creation of governments and facilitates the drafting of peace agreements in post-conflict countries. Northern Ireland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lebanon, and Iraq, to name just a few, are evidence of this. It becomes more difficult to argue that consociationalism facilitates post-conflict governance, or more specifically, that it leads to a social contract between the consociational government and the population at large. Iraq and Lebanon are evidence of consociational power sharing being a hindrance to governance and a key source of corruption as demonstrated, among others, by repeated protests against it; Northern Ireland and Bosnia and Herzegovina demonstrate that external actors are key to ensuring governance continues and disagreements don’t destabilize the government; however, the latter two could also be used to demonstrate the lack of progress on key agendas.Footnote5 As Jarstad recognizes, while there is no definitive evidence that it works, consociational power sharing may have different outcomes when considering its goal, be it serving stability (conflict mitigation) or democratic governance.Footnote6

This article uses the Iraqi case study to, as suggested by McCulloch and McEvoy,Footnote7 explain “the variances we see in different places with different power‐sharing rules,” rather than to back up an argument for or against consociationalism. As a case study of consociationalism, Iraq, as this article recognizes, has its own specificities, ranging from the post-regime change origin of consociationalism; its development in parallel to a post-conflict state; the preponderant role of external actors in its inception; the exclusive elite bargain upon which it rests; and, among others, its close relationship with the rentier nature of the Iraqi state. Therefore, the case of post-2003 Iraq cannot be used to dismiss consociational power sharing altogether. Consociational power sharing is a complex phenomenon that has both advantages and disadvantages in any given context. It varies based on institutional and policy formulation and degree of implementation and is subject to contextual (domestic and international) constraints.Footnote8 By weighing the pros and cons of the particular consociational arrangement in any given circumstance, one can arrive at a value judgment of its desirability.

While the many issues that affect Iraq, from corruption to substandard service delivery and overall poor socio-economic track records, are not unique to Iraq and cannot be ascribed to consociational systems per se, how consociationalism facilitates their permanence, as well as the (lacking) response to them, still invites much needed research on the topic. In the case of Iraq, the form of consociational power sharing in place has deeply impacted the development of the Iraqi post-conflict state, both in its institutional forms and in its functions. While since its inception it has bridged the gap between competing political elites, in time, it has widened exponentially the gap between them and the population.

Using post-2003 Iraq as a case study, this article examines Iraq’s consociational system—muhasasa ta’ifia (ethnosectarian apportionment)—within the broader consociational theory. It first examines the Iraqi case from both sides of the argument, seeking to bring more nuance to the debate on consociation. By doing so, it shows that consociational power sharing has been extremely valuable to reach an agreement, mitigate conflict, and form a post-conflict government in Iraq. At the same time, however, consociational power sharing has failed to meet the governance needs of the population, and although governments are formed, they do not necessarily govern and respond to people’s needs. Second, it examines why consociational power sharing has failed to build an effective governance system in Iraq and the role that exogenous actors, federalism, and institutions (or lack thereof) play in this failure. Finally, this article examines the consociational shelf life in Iraq, the limbo period that this creates, and the exit dilemma. Overall, it argues that in a post-conflict society like Iraq with considerable development needs, failure of consociational governance has a substantial negative impact on the population. As governance needs—connected to long-term development—continuously grow as a repercussion of them not being met (as recent protests in Iraq demonstrate), they eventually reach the level where they outweigh the conflict-mitigating benefits of consociation.

Methods

From a methodological point of view, integrating and complementing other articles in this special issue that propose a reflection on the Iraqi state and its relationship with consociational power sharing,Footnote9 this article examines consociationalism in Iraq from the perspective of the relationship between the expectations of the population on the state and whether the consociational system can deliver on these. Using the expectations of society that the state provides “dignity” or the foundations “to live a dignified life” based on the provision of services, employment opportunities, and security,Footnote10 this article takes a functional understanding of the state and the contract the state has with society—what McCulloch treats as part of the “performance legitimacy” of the state.Footnote11 In comparing the cases for and against consociational power sharing and examining the extent to which its reform is possible, the article is concerned with the meaning that consociational power sharing plays in Iraqi everyday lives. Sitting between the contributions in this special issue by DodgeFootnote12 and Salloukh,Footnote13 on the one hand, and AlkhudaryFootnote14 and Halawi,Footnote15 on the other hand, the article seeks to analytically connect the two components upon which consociationalism is built upon, that is, elite politics and societal aspirations.

To create a better and deeper understanding of the state of consociation in Iraq in relation to the population, survey research with Iraqis has been used. More specifically, online surveys advertised through social media were used to probe the perception of the population toward the consociational power-sharing system. These surveys allowed us to gain a greater understanding of whether the population thinks that the political system is viable and meets their needs. As the surveys were conducted online, we decided to carry out shorter surveys to maintain participants’ attention. Thus, for this article, two surveys totaling 18 questions were used. The surveys were translated into Iraq’s four main languages: Arabic, Assyrian, Kurdish, and Turkmen. Google Forms was used to build the surveys, and links to the surveys were shared across the Facebook pages of three Iraqi influencers and two media organizations chosen for the relevance of their audiences.Footnote16 The surveys were available over six weeks from the third week of June to the end of July 2021. The demographics of the responses were monitored throughout the process. Targeted boosting of Facebook posts was used to generate a higher number of responses and to balance the demographics to ensure representation across gender, locality, and age. The first survey (on governance) had 8,786 respondents (60.0 percent men and 40.0 percent women), and the second survey (on bringing about change) had 6,100 respondents (63.4 percent men and 36.6 percent women).

The case for consociation

At the time of the 2003 United States (US)-led invasion of Iraq, the country was living under a brutal dictatorship that ruled over an ethnically diverse society. The fall of that dictatorship laid bare the tensions and diverging interests of the many political entities that came to negotiate the future of the Iraqi state project, even before the occupation occurred. Identity-oriented political parties formed in opposition to the former regime that largely represented the Shi‘a community were adamant that the new political system in Iraq would guarantee their prerogatives as the country’s majority. Kurds in the North, meanwhile, had been living under de-facto autonomy for over a decade; they needed incentives to join any Iraqi government, and their participation did not come at the cost of their autonomy.Footnote17 In contrast, many of the Sunni population, fueled by the broad process of de-Ba’athification, feared their complete political marginalization.Footnote18

Aided by an essentialist reading of the Iraqi society as composed of three distinct communities prevalent in Western capitals at the time of the invasion and occupation of Iraq,Footnote19 consociational power sharing appeared outside Iraq to be the approach that could both prevent the return of an authoritarian regime by instituting mechanisms resisting a centralization of power and facilitate the containment of a civil conflict that was already spiraling out of control.Footnote20 A system allowing representation and influence to all parties involved was considered a bulwark against a growing insurgency exploiting and exacerbating sectarian tensions. The US, on its part, was fresh from its involvement in “negotiating” consociational settlements in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Northern Ireland, whilst the Iraqi political elite in the diaspora had already been negotiating the sharing of power. Thus, consociational power sharing in Iraq served both the normative liberal aspiration of the US-led state-building intervention in the country and the state capture logic that some political parties and politicians had already exposed at the beginning of the Iraqi transition. The means through which it has been formulated and implemented on the ground resulted in the muhasasa ta’ifia system being born.

A key element of consociational power sharing is that it uses the very communal divisions to institutionalize a mechanism of governance.Footnote21 Given the legacy of the Ba’ath regime, these divides were significant. From genocide to mass imprisonments and disappearances, many Kurds and Shi‘a (among other communities) held significant grievances that they placed with the previous regime but also extended to the Sunni population at large. Sunnis were the main victims of a lustration process that significantly contributed to the view that the emerging political elite was trying to politically marginalize them,Footnote22 whilst the Kurdish political elite were seen as wanting to break up Iraq. Trust was generally low between elites from all communities as a whole, and there was little chance of governance arrangements crossing the ethnosectarian lines, at least in the short term. Consociational power sharing, by providing each community’s political entrepreneurs a stake in the future Iraqi state, was thus thought of as the glue to hold Iraq together and avoid any forms of partition that could have had disastrous effects, both within the country and regionally.

Arguments in favor of consociational power sharing, while endorsing the inevitability of such arrangements due to contextual factors, recognize the limits of consociationalism in Iraq in its policy formulation and implementation. McEvoy and Aboultaif argue that the Sunni boycott of the January 2005 elections and essentially of the constitution formation process, against which they voted in the referendum, has weakened consociationalism in Iraq, as Sunnis were not behind the process.Footnote23 Nonetheless, as Sunni boycotting centered on their representation as a group, greater Sunni involvement would have still led to consociational power sharing in Iraq, with Sunnis focusing on their representation within the system. Bogaards recognizes instead the limit of consociational power sharing in Iraq in its “incomplete, informal, and increasingly voluntary” nature, which prevented the institution of a stable framework.Footnote24 Both these perspectives endorse a “more and more formal consociationalism,” claiming that it is unlikely Iraq would be anything other than consociation as the parties involved would not agree on any system that would lessen their power or involve significant cooperation across ethnosectarian lines.

The case against consociation

In contrast to the argument in favor of more and more formal consociationalism, the most frequently cited criticism of consociationalism is that by using the very communal divisions to institutionalize a mechanism of governance, it entrenches them within the society.Footnote25 The crystallization of (conflictual) identity politics in Iraq reached its apex during the civil war (2005–2007), but it is also evident in the political project pursued by the Islamic State as well as in the continuous tensions between Baghdad and Erbil over territorial demarcation, budget and resource sharing, and governance responsibilities. However, it can be argued that the consequences of the same deep-seated crystallization of identity politics also triggered a novel trend in Iraq whereby such divides are losing their grip. At the political level, political elites instrumentally maintain such communal divisions while acting as a cohesive actor when their tenure is threatened. At the societal level, meanwhile, there is instead a genuine call for a move away from sectarian politics, which has gained strength over time. This is best reflected by the protest movement that arose in October 2019, known as the Tishreen Uprising. These protests were driven by demands against corruption, unemployment, and a lack of basic services as well as for the overhaul of the post-2003 system of governance. The sectarian power-sharing system in place was seen to facilitate the spread of corruption and to empower political elites to use public resources to serve their private interests and increase their influence.Footnote26

An additional criticism toward consociationalism is that although power sharing may contribute to stability initially, it leads to ineffective governance in the longer term,Footnote27 the “immobilism problem” introduced by HorowitzFootnote28 and unpacked by McCulloch.Footnote29 Consociation in Iraq, particularly post-election coalition formation, leads to a government process purely based on horse trading for positions and benefits that extends deeply into the public sector as described by Dodge in this special issue.Footnote30 It does not focus on policies and developing a shared political manifesto. In addition, the time-consuming government-formation process limits the time the government has to implement any meaningful reforms or changes. Governments do not begin on the same policy page, and addressing pressing issues involves lengthy negotiation processes and is often held up or prevented by some parties.Footnote31 As a result, governments rarely prioritize long-term planning and do not adequately address the fundamental issues the country faces. Infrastructure, electricity supply, water, corruption, security, and so on—all need long-term policy planning and a shared vision to be implemented, which the consociational system in place has continuously failed to deliver on.Footnote32

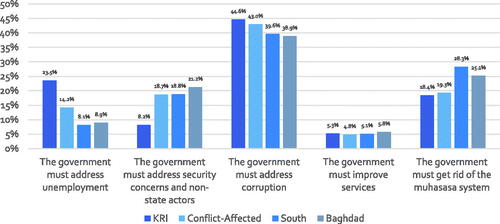

Connected to the above point, the current political system goes against what much of the population currently demands.Footnote33 If the initial development of consociational power sharing could rely on a broad convergence between political demand and offer (mostly driven by the precarious security situation in the country), societally, there has been a gradual move away from identity politics and toward the demand for issue-based politics (see ). Voter turnout decline—which reached its lowest level in the 2018 election at 44.5 percent,Footnote34 only to be lower again in the 2021 election at 41 percent, or 34 percent of the population over 18Footnote35—and the significant protest movement since October 2019 attest to this. In everyday life, consociational power sharing is experienced as the many forms that corruption takes in Iraq, from the grand political to the petty level. The frustration with the system, as well as the impact of corruption, is demonstrated in , where the government addressing corruption is the overriding factor in the population trusting the government, whilst a large proportion of those surveyed (average 23.7 percent) required the government to completely get rid of the muhasasa system for them to trust the government.

Figure 1. What is required to have (or regain) trust in your government? Note: This formed part of the first survey, which had 8,786 respondents.

With little legitimacy across society, or at least across the great portion of it that does not benefit from its maintenance, consociation in Iraq has become an object of growing popular criticism, however, one without institutional mechanisms set in place to end it, or valid, locally championed alternatives to replace it.Footnote36

Lastly, another contradiction of the consociational power-sharing system in Iraq, which speaks to the broader criticisms of consociationalism, connects to democratization and is best articulated by the extreme violence with which the 2019 protest movement has been met. Indeed, while consociational power sharing in post-conflict societies has been promoted as part of the democratization agenda,Footnote37 “power sharing itself is not inherently democratic. In fact, most elements of power sharing do not require democracy to function”.Footnote38 Despite consociational power sharing being seen as a constraint against the concentration of power, new scholarship is dissecting the relationship between consociational power sharing and forms of authoritarianism.Footnote39 In post-2003 Iraq, the formal institutional arrangements and the informal rules constitute an important obstacle to the risk of a relapse into an all-out form of authoritarianism. However, at the same time, consociational power sharing is one of the primary sources for the survival of authoritarian practices in the country, which enable the existing political elite to maintain the status quo and respond to any threats to the current regime, which is more regularly including violence.Footnote40 This emerging violence brings into question the conflict-mitigating element of consociation and raises the question of whether consociation has a shelf life, as discussed later in this article.

Principles of failure and reform

When discussing the principles of consociationalism, Lijphart argues that they “must be thought of as broad guidelines that can be implemented in a variety of ways—not all of the which, however, are of equal merit and can be equally recommended to divided societies”.Footnote41 Lijphart goes on to argue that “the biggest failures of power sharing systems […] must be attributed not to the lack of sufficient power sharing but to constitution writers’ choice of unsatisfactory rules and institutions”.Footnote42 What Lijphart suggests is, thus, to separate consociationalism, a broad theory with multiple options, from consociationalism as a particular consociational formula. Following this suggestion, the analysis below identifies those factors that influenced the development of consociational power sharing in Iraq as it appears nowadays. It focuses on three factors, which are identified as contributing to the failure of consociational power sharing in Iraq: the role of external actors; the contribution of federalism to consociational power sharing; and the role of consociational institutions in power sharing functioning.

Such analysis is conducive to see whether the system can be reformed.Footnote43 However, the extent to which eventual institutional changes would allow the consociational system to address some of the fundamental issues in the country and answer the population’s expectations of the state through good governance is a bigger question with more complex answers. As the literature on state building has vastly proved, a technical approach to institutions downplays the extent to which institutional change is plunged in power relations, contestation mechanisms, and prevailing imaginaries of the state.Footnote44 Power relations may change but only on paper as long as the prevailing imaginaries of the state continue to sustain the status quo. To assess the contribution of these factors to consociationalism in Iraq as a particular consociational formula, the article draws on the experiences of other post-conflict consociational arrangements.

External actors

In dealing with conflict-affected countries, and especially since the 1990s, the international community has been a key proponent of consociational power sharing as the preferred way to reach a peace agreement and favor the creation of a post-conflict government that could sanction the end of conflict. Beyond playing an important role in facilitating a consociational agreement, external actors are also essential in facilitating its implementation.Footnote45 For example, external actors can take roles that hold contention, therefore preventing conflict. Some examples of this include the overseeing of the implementation of police reform in Northern Ireland, which was done by Tom Constantine (US); and the Bosnian Supreme Court and Central Bank, which are presided over by external high representatives. External actors can also exert pressure when there is a lack of political compromise or when the executive is threatened.Footnote46 Northern Ireland is constantly heralded as a consociational success;Footnote47 however, it has active involvement from the British and Irish governments and the threat of direct rule by Westminster if the government fails.

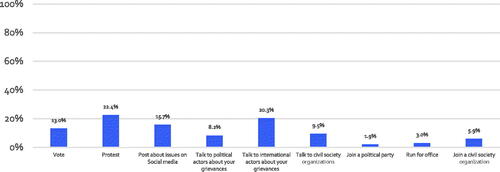

The role of external actors in promoting and sustaining power-sharing formulas is a matter of contention as they inevitably impinge on post-conflict countries’ legitimacy and/or sovereignty. Nevertheless, they represent a key variable in how consociational power sharing is designed, implemented, and perceived by local actors. In addition, a large footprint of external actors can also undermine the legitimacy of the government, as the population sees the solution with external actors rather than the government itself. This is demonstrated in below, where, after protest, those surveyed see talking to the international community as the most likely way to influence the political process—considerably higher than voting or talking to political actors.

Figure 2. The best way to influence the political process in Iraq. Note: This formed part of the second survey, which had 6,100 respondents.

In Iraq, the US was the main external actor ensuring the consociational arrangement was adhered to. It is no coincidence that the most authoritarian times of post-2003 Iraq happened after the US withdrawal in 2011.Footnote48 However, the US maintained an ambiguous position toward the policy formulation and implementation of power-sharing formulas. While the US exerted considerable pressure and influence on the constitution-making process, the 2005 Constitution contained little on the consociational structure of post-2003 Iraq, opening the way to the informal development of power sharing.Footnote49 In addition, the US did lack legitimacy with much of the population and political actors, which limited its role as an overseeing power and limited the period that it could legitimately remain to act as one.Footnote50 Moreover, as its influence waned, it was replaced by Iranian influence, which was more invested in having certain Shi‘a parties linked to its establishment controlling the state.

Iraq lacks (post-2011, but arguably earlier) a strong external proponent of consociation with the ability to pressure the political actors involved and enforce agreements when necessary. In the presence of recalcitrant domestic political elites exploiting consociational power sharing to maintain their positions and privileges at the expense of the common good, influential external actors may represent a check on the potential degeneration of consociational power sharing. However, they may also be a factor leading to such degeneration, when their objectives are not aligned with those of the population. This is what Lake calls the “statebuilder’s dilemma,” which is the tradeoff between building legitimate states in the eyes of the population and promoting a leadership loyal to the interests of external actors.Footnote51 When external actors are not willing, or do not have the legitimacy, to remain involved for the long term, consociationalism rests exclusively on domestic factors, thus placing a question mark over the arrangement once it is withdrawn. The withdrawal of external oversight and its timing are key; in Iraq, the US left too early (purely from a consociational arrangement standpoint) and left many constitutional arrangements yet to be finalized or agreed on by all actors.

Federalism

While it is argued that federalism is a key component for successful consociation, responding to the logic of guaranteeing segmental autonomy for the various communities,Footnote52 in Iraq, the form that federalism took has hampered consociationalism. The formation of only one federal region, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), with ambiguous prerogatives and contested responsibilities has hindered governance at the central level and negatively impacted development in the nonfederal governorates.Footnote53 In Iraq, federalism is enshrined in the 2005 Constitution, which allows for the governorates of Iraq to choose if they want to form a federal region with other governorates giving them territorial autonomy and powers with Baghdad having a special status as the center of the federal state.Footnote54

The literature is yet far from reaching an agreement on how federalism best serves consociationalism. McGarry and O'Leary argue that for a federal arrangement to work, there should ideally be three or more regions.Footnote55 They argue that having only two regions creates a win–lose situation in political negotiations at the center. Arguably so would only having one, as in Iraq. At the same time, Lijphart states that having too many segments in a power-sharing arrangement creates instability by lengthening the negotiation process, thus making three to four regions ideal.Footnote56 Erk and Anderson, meanwhile, argue in favor of having more than three regions in order to have more room for shifting alliances.Footnote57 Additionally, there should also not be a region of more than 50 percent of the population, as this leads to one region dominating the federation.Footnote58

In Iraq, only the KRI has managed to form a region, with others thus far failing to do so.Footnote59 Attempts at forming regions grew during the mandate of Nuri al-Maliki (2006–2014) to counter the increasing authoritarian centralization of power pursued by the former prime minister, but they were all blocked. The presence of only one region, strictly defined around the Kurdish identity, has harmed national governance, as Kurdish political parties have been more focused on using government formation and their place in the government to negotiate benefits for the KRI—creating a win–lose scenario in political negotiations.

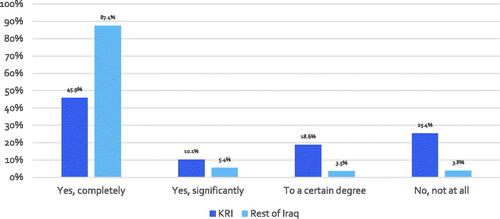

Despite the tremendous failures in instantiating a functioning democratic governance system, the governorates of Erbil, Duhok, Slemani, and Halabja have benefited greatly from having a federal region, thus placing them on a different footing. Within the Iraqi political system, the KRI has its own structure regulated by a regional constitution that establishes the competencies of the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches. The federal arrangement in parallel to informal mechanisms has granted the KRI ample room for segmental autonomy that in time has come closer to the form of a quasi-state, in addition to which the region has also developed its own source of legitimacy.Footnote60 Moreover, Kurds are less impacted by government failure in Baghdad but maintain the ability to contribute to its failure. Among other factors, the existence of one federal entity has contributed to the population’s thinking on whether ethnosectarian identity should be separated from politics, with a marked difference between those from within and without the federal region. As seen in , 45.9 percent of those surveyed in the KRI think ethnosectarian identity and politics should be completely separate, in comparison to 87.4 percent of the rest of Iraq.

Figure 3. Should politics and ethnosectarian identity be separate? Note: This formed part of the first survey, which had 8,786 respondents.

In a condition of remarkable state weakness, stronger regions may represent a way to counter inefficiencies from a purely governance and developmental perspective. However, while remaining open to the benefits that federalism can accrue to the regions, it would remain to be seen whether those same actors that have failed to address Iraq’s issues could formulate adequate policies at the central level in a more balanced federal system. The political economy of Iraq adds another concern when thinking about a federal solution, one with more than one region. This is likely to heighten already existing competition over resources such as hydrocarbons extracted in certain regions, much as it has done with the KRI. Finally, it can be questioned whether federalism would help address these developmental issues or simply lead to a mirrored system at the federal level, where power struggles are played at the regional level. The case of the KRI points toward the latter, whereby federalism has merely created smaller fiefdoms with the same problems related to governance issues.

(The lack of) consociational institutions

There are strong criticisms that power sharing in Iraq is voluntary and that it lacks institutional mechanisms to ensure power is shared and to elect the cabinet.Footnote61 However, this fails to acknowledge the permanence of this voluntary arrangementFootnote62 and how the idea of ethnosectarian division of power has a long history in Iraq,Footnote63 which is strongly anchored in informal institutions. Put simply, consociational power sharing is voluntary only in name and a government would not be formed without it. For example, in the 2014 government-formation process, Maliki felt the repercussions of going against the system and trying to centralize power around him in his previous term as PM, as despite winning the election he could not get support from other political groups, or international actors needed in the fight against the Islamic State, to form a government.Footnote64 Consociation is thus not as voluntarily and liberal as it is often purported to be, and many elements (mostly informal) follow corporate consociational principles, as certain factors, such as the division of top posts and deputies, are essentially decided before the elections. The mostly informal nature of consociational power sharing in Iraq lends support to both those who call for the introduction or reform of existing institutionsFootnote65 and those who instead attribute less importance to the formal level in producing a change.Footnote66 Nonetheless, given the dynamics that exist in Iraq, any formalization of consociation would be corporate in nature and thus further hinder change and the development away from the current system.

Starting from the government level, in Iraq, consociation relies on the formation of a government through negotiations over coalitions and government positions. This often results in a long-lasting political impasse over the formation of the government (a prime example of this is the 2010 Iraqi elections when government formation took nine months and the current 2021 government-formation process, which is still ongoing for over a year at the time of writing) or the instability of a government that can easily be dissolved if a large bloc chooses to withdraw (or more likely holds the government to ransom by threatening to withdraw). There are arguments that ministerial portfolios in Iraq should be allocated through sequential proportionality rules based on pre-election blocs,Footnote67 therefore forming coalitions and allocating the positions without having to negotiate and preventing blocs from withdrawing, or threatening to do so, as their positions will merely be allocated to those next in line. The Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland uses the d’Hondt system for this allocation, although McGarry and O’LearyFootnote68 favor the Sainte-Laguë method.Footnote69

In other contexts, notably Northern Ireland, these institutional arrangements have generally stabilized the government-formation process and provided the continuity of the government. Nonetheless, they have not prevented major issues from stalling the formation of the government. Furthermore, in the case of Iraq, there is no evidence that they alone could address the fundamental issue that no matter how the cabinet is formed, it is not based on a united manifesto but rather the result of a balancing act between competing political elites. With the immense developmental and structural issues that Iraq faces, this lack of a manifesto and long-term planning has significant negative impacts on the country and is the primary cause for the people’s rejection of the Iraqi political system altogether. Additionally, sequential proportionality rules would not necessarily mitigate the corruption that has marred the political process. It could be argued that selecting cabinet portfolios through sequential proportionality rules would allow smaller parties and those against sectarian politics a chance to join the cabinet, but it would not change the structures of governance, thus limiting the impact they could have.

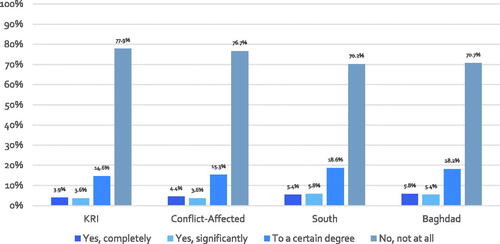

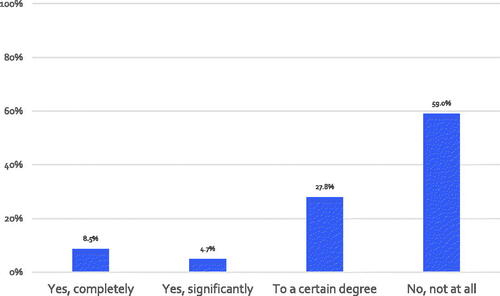

Similar conclusions can be reached on the impact of the newly approved electoral law on the functioning of consociational power sharing. The push toward changing the electoral law came from the streets and squares of Iraq, where protestors have voiced their opposition to the existing political system since October 2019. Following the resignation of prime minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi (2018–2020), protestors’ demands focused on the reform of the electoral law to secure a space for new political forces and actors. Among the requests were the abolition of the 18 provincial electoral districts to have instead a district for each electoral seat, adopting individual nomination procedures, lowering the minimum age (to 25) and educational requirements for being elected, and a reform of the Political Parties Law to reduce financial and bureaucratic barriers to form new parties.Footnote70 Although in the process of its ratification by the Parliament (5 November 2020) some of the proposed changes were watered down, the adoption of 83 electoral districts and the first-past-the-post voting procedure are a step toward enabling greater representation. However, this is far from having a significant impact on the informal power-sharing practice, and obstacles continue to prevent smaller or newly created political parties from entering the parliament (that is, the existing Political Parties Law, in addition to intimidation and attacks).Footnote71 As demonstrated in below, those surveyed largely think the political system does not offer representation to all societal groups, and despite the electoral changes, those surveyed did not think that the 2021 elections would lead to a strong and stable government (see ).

Figure 4. Does the current political system ensures equal representation to all societal groups? Note: This formed part of the first survey, which had 8,786 respondents.

Figure 5. Will the upcoming elections (2021) pave the way for a strong and stable government? Note: This formed part of the second survey, which had 6,100 respondents.

Beyond the government, broad representation of all communal groups is also important in the civil service. According to Lijphart this can be achieved

by instituting ethnic or religious quotas, but these do not necessarily have to be rigid. For example, […] a more flexible rule could specify a target of 15 to 25 percent. I have found, however, that such quotas are often unnecessary; it is sufficient to have an explicit constitutional provision in favor of the general objective of broad representation and to rely on the power sharing cabinet and the proportionally constituted parliament for the practical implementation of this goal.Footnote72

As well demonstrated in other articles in this special issue, in Iraq, employment in the civil service is connected to political parties and the election results, which only acts to feed corruption.Footnote73 This political division of civil service positions is often blamed on consociation.Footnote74 However, the broad representation of all communal groups in Iraq follows the logic of building and perpetuating a patronage system rather than ensuring equality and preventing discrimination. This applies also to the security apparatus in Iraq, with consequences that have been particularly profound for the country (that is, the collapse of the Iraqi army in front of the arrival of the Islamic State). Depoliticizing civil service appointees could have a significant impact on the civil service, by impacting the role it has on the patronage system; professionalizing it and thus helping to address its underperformance; and addressing the unnecessarily large number of people employed within it. This would be a longer-term process and would not address the political parties’ dominance of the portfolios the civil service fits within but would still have significant positive outcomes. In Northern Ireland, the “Civil Service Commissioners for Northern Ireland” was created to ensure equality and that selection is based on merit, as per Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.Footnote75 Thus rather than having a quota, in theory, broad representation is encouraged by avoiding discrimination in hiring.

Besides electoral politics, government formation, and the civil service, Iraq also has weak or non-existent institutions regulating the relationship between the federal government and the governorates. Their relationship has often been one of conflict rather than complementarity, with politicians shifting the blame from one level to the other to shield themselves from criticism. This occurred, for instance, in October 2019, when the Parliament suspended all provincial councils, against which the demonstrators directed much of their criticism for corruption and inefficiency.Footnote76 While Iraq still lacks the institute of a senate representing governorates and/or regions, which has never been implemented despite being mentioned in the constitution,Footnote77 the trajectory of the decentralization process has followed the ups and downs of Law 21 (Law of Provinces not incorporated into Regions), amended three times since its first ratification.

Decentralization is a measure upon which trust between federal and provincial authorities can be built, thus improving the chances for power sharing. However, the relationship between the federal government and the governorates (provincial councils and governors) is marred by the pervasiveness of the political struggle in the country, which is hardly contained by institutional mechanisms, as demonstrated by the continuous impasse over how to progress toward (or recede from) decentralization. This has profound implications for related policy areas, such as resource management and resource extraction in the country.Footnote78 Although decentralization has been on the agenda of the Iraqi transition since its inception and has received external international financial and political support, its implementation is still lagging. This has negative consequences on the capacity of the governorates to contribute to the performance legitimacy of the overall consociational power-sharing system in the country.

The exit dilemma: Iraq in limbo

The previous section has demonstrated some of the elements that could improve consociation in Iraq; however, put simply, these reforms are unlikely to be implemented by a political class empowered by the same system that they are called to reform. Nonetheless, even if implemented, it is questionable whether they would make the required impact at a stage when consociationalism has reached a “life of its own.” In theory, thus, the consociational system in Iraq has reached the end of its shelf life, having served a conflict-mitigating logic in its initial formulation and implementation but failing in its secondary goal of providing a ground for meeting societal needs. As governance and developmental needs continue to grow as a result of them not being met, they eventually reach the level where they outweigh the conflict-mitigating benefits of consociation. In the streets and squares of Iraq, large sections of the population have called for institutional change, whilst the political elites remain intransigent—leaving Iraq in limbo. As McCulloch highlights, there is an exit dilemma in consociational power sharing.Footnote79 Iraq lacks a sunset clause, and thus the mechanism of transition beyond consociationalism involves the very political elites that benefit from the system instigating the transition.

Sunset clauses grant the option of putting an end to consociationalism while promoting legal certainty by offering a clear timetable.Footnote80 Nonetheless, the provision of a sunset clause does not mean it would be without difficulties; it would still require political actors to willingly change the system. Moreover, it could also contribute to instability as with the deadline for political change on the horizon, political actors may become anxious about their place in the new governance system.Footnote81 However, it is also argued that sunset clauses can force the political elites to focus on addressing the issues at hand.Footnote82 The other two options put forward by McCulloch—judicial interventions and politically initiated reforms—are unlikely to be successful in Iraq.Footnote83 The judiciary has limited independence in Iraq and has thus far not played an active role in the country, whilst there is no role for international courts in the constitutional matters of Iraq. Politically initiated reforms suffer instead from the overarching opposition of existing political parties and actors.

Absent any institutional mechanism for putting an end to consociationalism in Iraq, attempts to this end have occurred instead through contentious means. The Islamic State’s project of creating a caliphate violently challenged the consociational system by creating a state-like entity designed for representing the community of its believers. By far a different experience, the referendum for the independence of the KRI in 2017 similarly challenged the consociational system by intending to pave the way for the secession of the KRI through a newly created state.Footnote84 Both these events conflated the consociational system in Iraq with its territorial borders; thus by challenging it, they challenged the very system itself, both inviting hard international and regional reactions against any attempt at modifying the political geography of the region.

On the other hand, there is the yet contentious attempt at ending consociationalism in Iraq from the bottom up. The shelf life of consociationalism in Iraq is closely connected to the generational shift; the majority of the population has only known the consociational system and perceives it as dysfunctional. As the population of Iraq has been deprived of the institutional opportunity to assess the system, it has taken to the streets and squares of Iraq to voice its dissent. Although it has expressed through protest practices an alternative to the status quo (that is, how the protestors organized in the square), the protest movement has so far fallen short of elaborating one univocal alternative manifesto against consociationalism. While it is widely perceived as one of, or even perhaps the main cause of, Iraq’s problems, consociationalism has left Iraq in a limbo from where an exit is not easily found.

Conclusion

In post-2003 Iraq, a consociational arrangement was needed to bring multiple actors together in the government; however, it has since then failed in meeting people’s expectations of the state. Iraq thus supports the argument that consociational power sharing serves a conflict-mitigation logic but is instead wanting on the delivery of accountable and efficient governance. However, the specific policy formulation and implementation of consociational power sharing in Iraq advises against making Iraq a case for or against consociation in general. Consociation and the consociational system that exists in Iraq need to be separated. One should not throw the baby (consociation) out with the bath water (muhasasa ta’ifia). While the latter is deeply flawed and, as this article demonstrates, its reform may not be enough to address the negative impact it has had on the country, the specific forms it took in Iraq and the various factors influencing it advise against a generalization.

Nonetheless, Iraq serves as evidence to show the complexity and fragility of governance solutions in deeply divided societies. Importantly, consociationalism in Iraq can be improved at the formal level; however, although these improvements would stabilize some elements of governance, they would not necessarily allow the Iraqi political system to address the fundamental issues that Iraq faces. Iraq also highlights the importance of exogenous actors and their role in ensuring the functioning of the consociational process. The ambiguous position the US had toward the policy formulation and implementation of power-sharing formulas and the haste with which it withdrew due to the lack of legitimacy it had in the country left the system crippled.

On the domestic side, the post-2003 Iraqi political leadership, from being the major proponents of such a system, even before regime change, became the main actors responsible for its failure. The lack of both a sunset clause and an engaged external actor in Iraq means that consociationalism that does not meet the needs of the population will continue, as it benefits political elites. The deeply informal nature of consociationalism in Iraq also means that its end will have to be forced by the population rather than through constitutional or institutional mechanisms.

By tracing the lifecycle of consociation in Iraq, this article introduces the argument of a consociational shelf life while demonstrating the importance of developing the right consociational arrangement in the first place. This article has demonstrated the clear failings in the constitution-making process, which have culminated in Iraq currently being in a position where large sections of the population want the political system to change, but it is unlikely to. If we take the protest movement as an articulation of what the population wants, then they want to elect parties based on their country-wide political manifesto, not on identity or regional needs. If the parties and alliances that emerged from the protest movement are anything to go by, then this involves political parties that cross ethnosectarian and regional boundaries.

Ultimately, the creation of the consociational system in Iraq was a political experiment where external actors played a major role, one put into place whilst there was ongoing conflict and a boycott of the political process by some sections of the population. It addressed the needs at that particular point in time. Experiments need an end, a period of evaluation, and a decision on whether to continue or change. Almost 20 years later, consociationalism in Iraq is no longer necessary or favored by large sections of the population. It has sectarianized politics when the population wants to focus on pressing and escalating issues. These issues grow by the day as a sectarian version of politics continues. Eventually, these issues are likely to outweigh the conflict-mitigating aspects of the Iraqi consociational system, and something will have to give.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the “Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective” workshop at the LSE Middle East Centre for their feedback. Special thanks are owed to the organizers—Taif Alkhudary, Prof. Toby Dodge, and Prof. Bassel Salloukh—the editors of the special issue, and the two anonymous reviewers.

The surveys for this publication were made possible through support provided by the United Nation Development Programme (UNDP), Iraq. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNDP. The authors would like the thank Barbara-Anne Krijgsman and Zena Ali Ahmad from UNDP for their feedback on the wider research project, all errors and faults of course remain our own.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dylan O’Driscoll

Dylan O’Driscoll is an Associate Professor at the Center for Trust, Peace and Social Relations (CTPSR), Coventry University, where he leads the Peace and Conflict Research Theme. He is also Associate Senior Fellow at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

Irene Costantini

Irene Costantini is an Assistant Professor in International Relations at the University of Naples L’Orientale. Previosuly, she has been teaching and/or researching, among others, at the University of Bologna, the University of York, the Austrian Institute for International Affairs, and the Middle East Research Institute.

Notes

1 Allison McCulloch and Joanne McEvoy, “The International Mediation of Power-Sharing Settlements,” Cooperation and Conflict 53, no. 4 (2018): 467–85.

2 John McGarry and Brendan O’Leary, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005: Liberal Consociation as Political Prescription,” International Journal of Constitutional Law 5, no. 4 (2007): 670–98.

3 Donald Horowitz, “Constitutional Design: Proposals Versus Processes,” in The Architecture of Democracy, edited by A. Reynolds (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 15–36.

4 Rupert Taylor, ed., Consociational Theory: McGarry and O’Leary and the Northern Ireland Conflict (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009). Although Stefan Wolff does engage with both consociational and integrationist theories, in reality he lands firmly on the consociational side: Stefan Wolff, “Conflict Management in Divided Societies: The Many Uses of Territorial Self-Governance,” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 20, no. 1 (2013): 27–50.

5 Allison McCulloch, “Getting Things Done? Process, Performance, and Decision-Evasion in Consociational Systems” (paper presented at the Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective, LSE Middle East Centre, 2022).

6 Anna K. Jarstad, “Dilemmas of War-to-Democracy Transitions: Theories and Concepts,” in From War to Democracy: Dilemmas of Peacebuilding, edited by A. K. Jarstad and Timothy D. Sisk (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 17–36; A. K. Jarstad, “Sharing Power to Build States,” in Routledge Handbook of International Statebuilding, edited by David Chandler and T. D. Sisk (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2013), 246–56.

7 Allison McCulloch and Joanne McEvoy, “Understanding Power-Sharing Performance: A Lifecycle Approach,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 20, no. 2 (2020): 109–16, 6.

8 McCulloch, “Getting Things Done?”

9 See Taif Alkhudary, “From Muhasasa to Mawatana: Consociationalism and Identity Transformation in the Iraqi Protest Movement 2015-2019” (paper presented at the Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective, LSE Middle East Centre, 2022); Toby Dodge, “Iraq, Consociationalism and the Incoherence of the State” (paper presented at the Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective, LSE Middle East Centre, 2022); Maria Fantappie, “Inside Iraq’s Muhasasa: Adhering, Deserting or Transforming Consocionalism” (paper presented at the Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective, LSE Middle East Centre, 2022).

10 Dylan O’Driscoll, Shivan Fazil, Lucia Ardovini, Meray Maddah, and Amal Bourhrous, “Reimagining the Social Contract in Iraq” (UNDP Policy Paper, 2022). https://iraq.un.org/en/185826-reimagining-social-contract-iraq

11 McCulloch, “Getting Things Done?”

12 Dodge, “Iraq, Consociationalism and the Incoherence of the State.”

13 Bassel Salloukh, “The State of Consociationalism in Lebanon,” (paper presented at the Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective, LSE Middle East Centre, 2022).

14 Alkhudary, “From Muhasasa to Mawatana.”

15 Ibrahim Halawi, “Lebanon’s Political Opposition in Search for Identity: He Who Has No Sect among You Cast the First Stone” (paper presented at the Consociationalism and the State: Lebanon and Iraq in Comparative Perspective, LSE Middle East Centre, 2022).

16 Facebook is the leading social media platform; as of 31 March 2021, there were 25.5 million active Facebook subscribers in Iraq (see https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats5.htm).

17 Irene Costantini and Dylan O’Driscoll, “Party Politics in Quasi-States: Iraqi Kurdistan,” in Routledge Handbook on Political Parties in the Middle East and North Africa, edited by Francesco Cavatorta, Lise Storm, and Valerie Resta (London: Routledge, 2020), 218–28.

18 Dylan O’Driscoll, “Autonomy Impaired: Centralisation, Authoritarianism and the Failing Iraqi State,” Ethnopolitics 16, no. 4 (2017): 315–32.

19 Joseph R. Biden and Leslie H. Gelb, “Unity through Autonomy in Iraq,” The New York Times, 2006. http://nyti.ms/1rPuMIE; Peter W. Galbraith, “How to Get Out of Iraq,” New York Review of Books, 2004. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2004/05/13/how-to-get-out-of-iraq/; Leslie H. Gelb, “The Three-State Solution,” The New York Times, 2003. http://nyti.ms/1BF0HAb.

20 Irene Costantini, Statebuilding in the Middle East and North Africa: The Aftermath of Regime Change (London: Routledge, 2018).

21 McGarry and O’Leary, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005.”

22 Shamiran Mako, “Subverting Peace: The Origins and Legacies of de-Ba’athification in Iraq,” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 15, no. 4 (2021): 476–93.

23 Joanne McEvoy and Eduardo Wassim Aboultaif, “Power-Sharing Challenges: From Weak Adoptability to Dysfunction in Iraq,” Ethnopolitics 21, no. 3 (2020): 238–57.

24 Matthijs Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005: The Case against Consociationalism ‘Light,” Ethnopolitics 20, no. 2 (2021): 186–202.

25 Horowitz, “Constitutional Design”; Taylor, Consociational Theory.

26 Irene Costantini, “The Iraqi Protest Movement: social Mobilization Amidst Violence and Instability,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 48, no. 5 (2020): 832–49; Faleh Jabar, “The Iraqi Protest Movement: From Identity Politics to Issue Politics” (LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series, 2018). http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/88294/1/Faleh_Iraqi%20Protest%20Movement_Published_English.pdf; O’Driscoll et al., “Reimagining the Social Contract in Iraq.”

27 Donald Rothchild, “Reassuring Weaker Parties after Civil Wars: The Benefits and Costs of Executive Power-Sharing Systems in Africa,” Ethnopolitics 4, no. 3 (2005): 247–67.

28 Donald Horowitz, “Ethnic Power Sharing: Three Big Problems,” Journal of Democracy 25, no. 2 (2014): 5–20.

29 McCulloch, “Getting Things Done?”

30 Dodge, “Iraq, Consociationalism and the Incoherence of the State.”

31 Renad Mansour, “Iraq’s 2018 Government Formation: unpacking the Friction between Reform and the Status Quo” (LSE Middle East Centre Report, 2019), 1–21.

32 Amal Bourhrous, Shivan Fazil, Meray Maddah, and Dylan O’Driscoll, “Reform within the System: Governance in Iraq and Lebanon” (SIPRI Policy Paper, 61, 2021). https://www.sipri.org/publications/2021/sipri-policy-papers/reform-within-system-governance-iraq-and-lebanon.

33 Alkhudary, “From Muhasasa to Mawatana.”

34 Renad Mansour and Christine van den Toorn, “The 2018 Iraqi Federal Elections: A Population in Transition?” (LSE Middle East Centre Report, 2018). http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/89698/7/MEC_Iraqi-elections_Report_2018.pdf.

35 Taif Alkhudary, “Elections Usher in a New Wave of Political Opposition in Iraq,” AlAraby, 2021. https://english.alaraby.co.uk/opinion/elections-usher-new-wave-political-opposition-iraq.

36 Toby Dodge, “Iraq’s Informal Consociationalism and Its Problems,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 20, no. 2 (2020): 145–52; Maria Fantappie, “Widespread Protests Point to Iraq’s Cycle of Social Crisis” (International Crisis Group Commentary, 2019). https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iraq/widespread-protests-point-iraqs-cycle-social-crisis; O’Driscoll et al., “Reimagining the Social Contract in Iraq.”

37 Jarstad, “Dilemmas of War-to-Democracy Transitions”; Jarstad, “Sharing Power to Build States,” in Routledge Handbook of International Statebuilding.

38 Caroline A. Hartzell and Mathew Hoddie, “The Art of the Possible: Power Sharing and Post—Civil War Democracy,” World Politics 67no. 1 (2015): 37–71.

39 Paul Dixon, “Power-Sharing in Deeply Divided Societies: Consociationalism and Sectarian Authoritarianism,” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 20, no. 2 (2020): 117–27.

40 Irene Costantini, “Silencing Peaceful Voices: Practices of Control and Repression in Post-2003 Iraq,” in New Authoritarian Practices: State Control in the Middle East and North Africa, edited by Ozgun Topak, Merouan Mekouar, and Francesco Cavatorta (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022).

41 Arend Lijphart, Thinking About Democracy: Power Sharing and Majority Rule in Theory and Practice (London: Routledge, 2008), 66.

42 Ibid., 78.

43 See for example Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005”; A. McCulloch, “Consociational Settlements in Deeply Divided Societies: The Liberal-Corporate Distinction,” Democratization 21, no. 3 (2014): 501–18; McGarry and O’Leary, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005”; O’Driscoll, “Autonomy Impaired”; Dylan O’Driscoll, “The Costs of Inadequacy: Violence and Elections in Iraq,” Ethnopolitics Papers no. 27 (2014): 1–29. Retrieved from https://www.psa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/page-files/EPP027_0.pdf.

44 Shahar Hameiri, “Failed States or a Failed Paradigm? State Capacity and the Limits of Institutionalism,” Journal of International Relations and Development 10, no. 2 (2007): 122–49; Marina Ottaway, “Rebuilding State Institutions in Collapsed States,” Development and Change 33, no. 5 (2002): 1001–23.

45 Joanne McEvoy, “The Role of External Actors in Incentivizing Post-Conflict Power-Sharing,” Government and Opposition 49, no. 1 (2014): 47–69; John McGarry, “Classical Consociational Theory and Recent Consociational Performance,” Swiss Political Science Review 25, no. 4 (2019): 538–55; John McGarry and Brendan O’Leary, “Consociational Theory, Northern Ireland’s Conflict, and Its Agreement. Part 1: What Consociationalists Can Learn from Northern Ireland,” Government and Opposition 41, no. 1 (2006): 43–63; Dawn Walsh and John Doyle, “External Actors in Consociational Settlements: A Re-Examination of Lijphart’s Negative Assumptions,” Ethnopolitics 17, no. 1 (2018): 21–36.

46 McEvoy, “The Role of External Actors”; Walsh and Doyle, “External Actors in Consociational Settlements.”

47 McGarry, “Classical Consociational Theory.”

48 See for example Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005”; T. Dodge, “Can Iraq Be Saved?,” Survival 56, no. 5 (2014): 7–20; O’Driscoll, “Autonomy Impaired”; David Romano, “Iraq’s Descent into Civil War: A Constitutional Explanation,” The Middle East Journal 68, no. 4 (2014): 547–66.

49 Andew Arato, Constitution Making Under Occupation: The Politics of Imposed Revolution in Iraq (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009); Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005.”

50 In Northern Ireland, legitimacy was ensured by having both the Irish and British governments involved and on more or less the same page.

51 David A. Lake, The Statebuilder’s Dilemma: On the Limits of Foreign Intervention (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016).

52 Arend Lijphart, “The Wave of Power Sharing Democracy,” in The Architecture of Democracy, edited by A. Reynolds (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 37–54; O’Driscoll, “Autonomy Impaired”; Wolff, “Conflict Management in Divided Societies.”

53 This examination focuses purely on governance and long-term development and is separate from any debate as to whether autonomy leads to secession.

54 Iraqi Constitution, Iraqi Constitution (Baghdad: Ministry of Interior, 2005). http://www.iraqinationality.gov.iq/attach/iraqi_constitution.pdf.

55 John McGarry and Brendan O’Leary, “Must Pluri-National Federations Fail?,” Ethnopolitics 8, no. 1 (2009): 5–25.

56 Arend Lijphart, Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977).

57 Jan Erk and Lawrence Anderson, “The Paradox of Federalism: Does Self-Rule Accommodate or Exacerbate Ethnic Divisions?,” Regional & Federal Studies 19, no. 2 (2009): 191–202.

58 McGarry and O’Leary, “Must Pluri-National Federations Fail?.”

59 Benjamin Isakhan and Peter E. Mulherin, “Basra’s Bid for Autonomy: Peaceful Progress toward a Decentralized Iraq,” The Middle East Journal 72, no. 2 (2018): 267–85; O’Driscoll, “Autonomy Impaired.”

60 Dylan O’Driscoll, Irene Costantini, and Serhun Al, “Federal versus Unitary States: Ethnic Accommodation of Tamils and Kurds,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 26, no. 4 (2020): 351–68.

61 Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005”; McGarry and O’Leary, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005”; O’Driscoll, “The Costs of Inadequacy.”

62 Dodge, “Iraq’s Informal Consociationalism and Its Problems.”

63 Taif Alkhudary, “How Iraq’s Sectarian System Came to Be,” Al Jazeera, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/3/29/how-iraqs-sectarian-system-came-to-be/.

64 Hamzeh Hadad, “Path to Government Formation in Iraq,” Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2022. https://www.kas.de/en/web/syrien-irak/single-title/-/content/path-to-government-formation-in-iraq; O’Driscoll, “Autonomy Impaired.”

65 Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005.”

66 Fantappie, “Inside Iraq’s Muhasasa.”

67 O’Driscoll, “The Costs of Inadequacy.”

68 John McGarry and Brendan O’Leary, “Power Shared after the Deaths of Thousands,” in Consociational Theory: McGarry and O’Leary and the Northern Ireland Conflict, edited by R. Taylor (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009), 15–84.

69 Under the d’Hondt system, in each round, the party with the highest number of seats wins a position. The total number of seats that the party has is divided each time a position is won, following a sequence of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, etc., and transferred to the next round. The Sainte-Laguë method follows the same pattern as the d’Hondt method, however the divisor sequence is 3, 5, 7, 9, etc.

70 Omar al-Jaffal, “Iraq’s New Electoral Law: Old Powers Adapting to Change,” Arab Reform Initiative, 2021. https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/iraq-elections/.

71 Sajad Jiyad, “Protest Vote: Why Iraq’s Next Elections Are Unlikely to Be Game-Changers” (LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series 48, 2021). http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/110201/1/Protest_vote_iraq_elections_paper_48.pdf

72 Lijphart, Thinking About Democracy, 84.

73 Dodge, “Iraq, Consociationalism and the Incoherence of the State”; Toby Dodge and Renad Mansour, “Politically Sanctioned Corruption and Barriers to Reform in Iraq” (Chatham House Research Paper, 2021). https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/06/politically-sanctioned-corruption-and-barriers-reform-iraq; Fantappie, “Inside Iraq’s Muhasasa.

74 Dodge, “Iraq’s Informal Consociationalism and Its Problems.”

75 For more details on the work of the Civil Service Commissioners for Northern Ireland, see https://www.nicscommissioners.org/what-we-do.htm.

76 Ali Al-Mawlali and Sajad Jiyad, “Confusion and Contention: Understanding the Failings of Decentralization in Iraq” (LSE Middle LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series, 44, 2021). http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/108534/3/Confusion_and_Contention.pdf.

77 Bogaards, “Iraq’s Constitution of 2005.”

78 Mike Fleet, “Decentralisation and Its Discontents in Iraq” (Policy Paper 2019-18, 2019). https://www.mei.edu/publications/decentralization-and-its-discontents-iraq.

79 Allison McCulloch, “Pathways from Power-Sharing,” Civil Wars 19, no. 4 (2017): 405–24.

80 Antonios Kouroutakis, “The Virtues of Sunset Clauses in Relation to Constitutional Authority,” Statute Law Review 41, no. 1 (2020): 16–31.

81 McCulloch, “Pathways from Power-Sharing.”

82 A. Carl Le VAN, “Power Sharing and Inclusive Politics in Africa’s Uncertain Democracies,” Governance 24, no. 1 (2011): 31–53.

83 McCulloch, “Pathways from Power-Sharing.”

84 Dylan O’Driscoll and Bahar Baser, “Referendums as a Political Party Gamble: A Critical Analysis of the Kurdish Referendum for Independence,” International Political Science Review 41, no. 5 (2020): 652–66.