Abstract

This paper grapples with the impact of the postwar consociational system in Lebanon on the articulation and organization of political opposition, focusing on the period between 2011 and Lebanon’s October 2019 protests. It argues that the articulation and organization of political opposition is limited by a deeply rooted sectarian episteme of politics as a result of decades of consociational politics and subsequently sectarian state–society relations. The paper shows how nonsectarian oppositional actors concede to the pervasiveness of sectarian identity by resorting to a very narrow or very broad articulation of demands, avoiding, in the process, confrontation with sectarian prejudice. The paper also shows how, conscious of the pervasiveness of sectarian identities, sectarian actors have continued to hold popular support and discredit narrow and broad demands by resorting to sectarian identities. Whilst there are many factors that help explain the weaknesses inflicting political opposition, this paper focuses on the question of identity, not as a mere analytical tool constructed by elites, but as a seemingly authentic articulation, which is initially generated through routine practices that, indeed, elites and the state play a defining part in structuring.

Introduction

This paper argues that postwar consociational power sharing in Lebanon, which has produced deeply sectarian social, economic and political life, has limited the articulation and practice of opposition to sectarianism and thus has undermined the prospects of any viable alternative despite ideal political circumstances. After decades of “sectarianization” at every level of social,Footnote1 political,Footnote2 economicFootnote3 and even sexual and gendered life,Footnote4 sectarian identities eventually assumed a degree of ideological authenticity, which, as this paper shows, impedes the emergence of alternative identities and, subsequently, radical political organization.

In this sense, sectarian identities are no longer an exclusively phenomenological symptom of elite-serving politics, as the sectarianization thesis argues.Footnote5 By now, the sectarian episteme has become embedded in the practices of opposing consociational power-sharing because it has had a monopoly over the epistemology of politics for decades.Footnote6 This paper shows how this episteme has limited the scope of ideas, ideologies and meanings being constructed within sites of opposition. Therefore, in these sites, sectarian identities are not merely analytical tools to make sense of the structures of consociational power sharing. They define the political episteme with which Lebanon’s political opposition grapples to form identities that can negate and withstand it. This perspective thus departs from the “sectarianization” thesis without, however, denying the latter’s empirical-historical grounds. On this view, then, the impact of sectarian identities and its phenomenological significance go beyond the structural acts of elite-serving “sectarianization.”

This is the identity factor that this paper examines in Lebanon’s post-2011 opposition: its underlying alternative identification vis-à-vis sectarian identities that seems to outlast, until further notice, the very political economy and consociational arrangement that sectarian elites relied on to produce and reproduce them in postwar Lebanon.Footnote7 To do so, it employs a conceptual framework borrowed from Charles Tilly’s work on identity making and actor constitution. Using an interactive approach to identity making and actor constitution, Tilly distinguishes between embedded identities, such as sectarian identities, and disjointed identity, which often emerge out of mobilization around mutual interest, rather than publicly recognized de facto belonging. So, the latter form of identities—founded primarily on social effort to realize common interest—requires more concerted effort to be noticeable than identities grounded on deeper and/or historical myths, which, in turn, are more imposing and noticeable. By identifying this distinction in conceptualizing identity, the paper can then speak directly to the pervasiveness of sectarian identities over interest-based and disjointed identities.

However, this paper does not assume that identity alone can explain the limitations of opposition. Alternative explanations relate this to a “global neoliberal logic of action,”Footnote8 or structural-institutional factors,Footnote9 especially the peculiar political economy in postwar Lebanon.Footnote10 Others in critical media studies relate this limitation to the internet age and social media.Footnote11 But the identity approach contributes to this wider conversation and does not necessarily contradict it, especially in the study of anti- and nonsectarian political phenomena. It acknowledges that the sectarian identities under study are historically constructed yet dominant precisely because of domestic and international power structures, be it local elites or broader neoliberal or modern structures, and, thus, accepts that sectarian identities are not fixed or objectively authentic markers of political phenomena. Nevertheless, this paper suggests that individuals subject to constructed identities are not always, if at all, conscious of its constructivist nature, nor that their closely held identities are conditional upon specific power relations. Instead, their identities become, at least to themselves, a kind of common sense, married unconditionally to one’s social and political life. So, studying the repercussions of this specific identity-related conclusion reaffirms the far-reaching impact of economic and political structures, domestic and international, which condition and materialize identities in the first place.

In the following sections, this paper reviews the different approaches to identity in the literature, highlighting how it departs from existing work on sectarianism and sectarian identities in Lebanon. Then, it will expand on its theoretical and methodological approaches before employing these approaches to examine the limits of identity making among the nascent political opposition to Lebanon’s consociational regime.

The identity factor: an analytical tool or a practice?

Naturally, foregrounding identity in the analysis is tantamount to stepping into an analytical and methodological minefield. Not only the concept itself is vehemently contested, but even its analytical utility takes strikingly different forms. In what concerns Lebanon, the critical debate on sectarianism and sectarian identities has been dominated by largely instrumentalist frameworks.Footnote12 For instrumentalists, sectarian identities are, at best, “categories of analysis,” borrowing from Pierre Bourdieu, in which their authenticity is assumed to be largely insignificant, and their analytic value rests on their explanatory potential for phenomena that are not directly identitarian, but, instead, material, symbolic or structural. This, for instance, is the case with the sectarianization thesis in the Middle East, which considers sectarian identities as primarily analytical categories that have more to say about elites and geopolitics, than about how people imagine their group identities as truly authentic and the implications of this perception.Footnote13 However, many studies pertaining to gender, race, and ethnicity, treat identities as discursive “categories of practice,” which define politics at every level, from the everyday interactions (and violence) of ordinary people to structures of political power.Footnote14 Identities are then considered the episteme of reality: the knowledge that individuals use to make sense of themselves, of their activities, of what they share and how they differ.

Identity thus tends to mean either too much or too little. In this ongoing debate, the stance one takes on the role of the state is crucial. Some believe that the state has a monopoly over not only legitimate physical force but also legitimate symbolic force.Footnote15 This manifests itself in the state’s authority to identify, categorize and define what is what and who is who. The state is thus a powerful “identifier,” not only because it has the capacity to create and promote specific identities, but also because it has the material and symbolic resources to “impose the categories and modes of social counting and accounting with which bureaucrats, judges, teachers, and doctors must work and to which non-state actors must refer.”Footnote16 But this “monopoly” is perpetually contested. The literature on social movements is rich in evidence on how movement leaders challenge official identifications and propose alternative ones.Footnote17 No less prevalent is the body of work based on Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony and counter-hegemony, which unpacks the cultural struggle over class consciousness underpinning political mobilization and revolutionary politics.Footnote18 Nevertheless, contestation is not only a feature of “social movements.” Challenging state-sponsored ‘categorization’ does happen in different (super)structures, such as families, schools, universities, the workplace, and even on the internet.

As for the role of the state as “powerful identifier,” this paper builds on existing work on the overlap between sectarian elites and the state in postwar Lebanon, not least because they operate on behalf—and through—the state.Footnote19 Sectarian elites have the material and symbolic resources to impose identification, categorization and even social counting and accounting, in a country that has not conducted a national census since 1932, to avoid upsetting consociational arrangements.Footnote20

Theoretical approach: the identity factor

Social identity, which is a common approach in social psychology, provides a relational understanding of group identification and mobilization, because it considers “othering” as a natural and indispensable aspect of identity formation. The prejudiced views against the “outer-groups” that accompany identities are necessary to exaggerate one’s in-group homogeneity and pride.Footnote21 Given this understanding of group identification, the viability of alternative nonsectarian forms of identification relies on the effectiveness of its own prejudices against sects. The emergence of such identification depends on consistent articulation of “the other,” in this case sectarian identities, which consequently invites claims of nonsectarian homogeneity upon which society can be re-ordered. In other words, nonsectarian identification requires coherent anti-sectarian imagination.

Tilly’s conceptualization follows directly from this understanding. According to Tilly, the very existence of a “political actor” in a phenomenologically consistent form relies to some degree on organizational-social effort into the construction of “coherent performances” which separate those involved in this effort from “other people.”Footnote22 This organizational effort produces, in practice, some visible signs of common membership—that is, public identity, upon which the actor is identified and identifies itself. But neither the organizational effort that invites identity making nor the nature of the performances that produce visible signs are the same across the spectrum of actor constitution. Some political actors are organized in seemingly more authentic forms, which are often traditional and inherited. These identities are more consistent in their articulation precisely because of their longevity, which assumes deep ideational roots and/or physical features that are well-recognized outside the group. Tilly refers to these identities as being “embedded,” given how “deep” they seem to be or, in other writings inspired by Harrison White, “catness,” given how stubborn their categorization is.Footnote23 An embedded identity as such contains people who recognize their common characteristic, and who everyone else recognizes as having that characteristic: they are all female, all Muslims, all residents of Tripoli, all American, and so on.Footnote24 They might not share the same socioeconomic interests as individuals, but their belonging to a shared and well-recognized articulation of ideas, values, experience, culture or geography justifies and, in some instances, incentivises a grouping based on this common articulation.

Other actors, meanwhile, are organized through more entrepreneurial performances, and, consequently, their public identity is “disjointed” by nature. They rely on coordinated effort of individuals to recognize specific mutual interest, rather than having embedded values or de facto belonging. In this case, their process of social construction includes grappling with lack of recognition outside their group, because their very grouping follows its own logic of association. For example, an animal rights group is a network of people who all care about animals. What brings them together is not an assumption of common roots or similar features but a perceived common interest. For instance, if these individuals are brought together in a protest, without holding any banners or making any claims, there is hardly any common characteristic that everyone recognizes. Their identity relies on organized effort that ensures the continuation of shared recognition of mutual interest. There is no overarching identity that defines them and gives meaning to their social and political surrounding. They do not necessarily share much in their everyday life, except, possibly, in the past example, their vegetarianism.

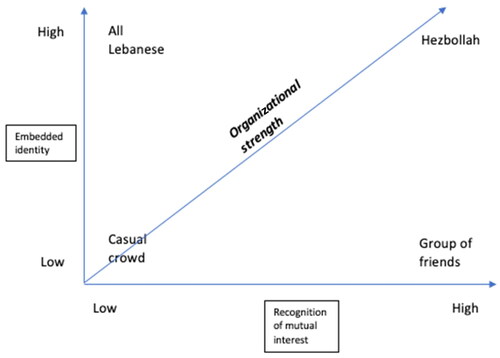

These two identities are therefore the product of “contrasting processes of social construction.”Footnote25 As discussed above, identities founded primarily on social effort to realize common interest require more concerted effort to be noticeable than identities grounded on deeper and/or historical myths, which, in turn, are more imposing and noticeable. The idea of organization follows directly from this conceptualization: the more organized the group, the more clearly articulated and recognized its common identity and the more strongly recognizable its mutual interest is.Footnote26 , below, shows a schematic example of analyzing four different groups of people based on the discussion of public identity above.

Figure 1. Example of the relationship between organizational strength, embeddedness of identity and recognition of mutual interest.

“All Lebanese” comprises a set of people only weakly linked by interpersonal networks of mutual interest but strongly identified by themselves and others as a separate category of people. In contrast, Hezbollah, which possesses a solid organization and a consistent articulation of its public identity, has both a distinct and compelling identity related to religious, ideological and inherent performances as well as extensive and absorbing interpersonal networks founded on recognition of many members of the Shi‘a sect of shared interest in this organization.

The value of this analytical framework is in the fact that it does not deny the agency of individuals in (re)imagining identities, while also acknowledging the defining nature of history and power, be it that of the state or the consociational power-sharing political system, on people’s identities and, consequently, on the forms of contentions in which they participate. In other words, this framework recognizes that “Lebaneseness” as embedded identity is the product of historical processes, and, today more than ever, the nationalism that it represents is the by-product of specific power relations. But despite its instrumental power-serving and power-constructed nature, this identity can claim a life of its own, irreducible to the traditional structures that perpetuated it for decades because of the long-lasting impact of its imagined authenticity or its deep influence on the episteme of politics. Therefore, such an identity not only defines how people mobilize, organize, belong and understand the world around them but, also, how far they can mobilize, organize, belong and understand the world around them differently—in some alternative form of identification. This applies to sectarian identities and their impact on the opposition.

Methodological approach and positionality

This paper relies on extensive fieldwork in Beirut through active participation and membership in several protest movements and oppositional political organizations over the entire time frame (2011–2019), as well as recorded observations and nine semi-structured interviews between 2019 and 2020 for the purpose of this research. Active participation provided years of candid experience and observation, which inform the critical approach of this paper. Through this experience, it became clear how the different movements and organizations that have emerged in this period were not entirely separate movements at any point in this time frame. They—or, may I say, we—were significantly influencing each other’s narrative, approaches, structures, strategic decisions and outcomes, to the extent that many organizations had fluid membership schemes that led to “double members” who oscillated between groups. This is why this paper does not start from a survey of different oppositional organizations, nor does it fixate on a specific event of protest as the site of opposition making. It is not concerned with the “number” or organizations or their genealogy. Instead, it weaves through different manifestations (including articulations) of identity by various actors in different settings, including official statements, speeches, slogans and banners, as well as political and organizational choices, to uncover, through these observations, a pattern of limitations in identity making indicative of the pervasiveness of sectarian identities.

As for interviews, some interviews were made in-person and others were done over Skype, WhatsApp or Zoom. The interviewees are mostly active and some leading members in protest movements or political organizations. They were, in some instances, “comrades” in a movement and, in other instances, fellow organizers of protests or campaigns. Their input is anonymized for both ethical and security considerations.

Old and new opposition to sectarianism in Lebanon

Literature on Lebanon’s consociational power-sharing system largely presumes that the political field is exclusively sectarian, given that the consociational order has restricted forms of political life. Consequently, resistance to or contention with the consociational order has been strictly manifested in civil society organizations and occasional street outbursts.Footnote27 In other words, it reduces anti-sectarian or nonsectarian political phenomena to the absence, presence and frequency of protests, given that, to a large extent, political organization has been the privilege of sectarian parties. This might have been the case until recently, when most of these protest activists being studied and surveyed began to organize. But, apart from the debate on civil society and NGO-like organization,Footnote28 the complex and contentious processes which have recently culminated in the emergence of organized political opposition to sectarianism in Lebanon remain understudied.Footnote29

Although this opposition suffers from limitations, which this paper grapples with in relation to identity, it is nevertheless becoming increasingly recognized. Upon an official visit to Lebanon in May 2021, the French Foreign Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, invited all organized opposition groups to a meeting, signaling their growing political role in Lebanon. The most recent testament to this is their relative electoral success in the parliamentary elections in May 2022, when thirteen new MPs were elected under oppositional slogans for the first time in postwar history, this coming on the heels of the victory of the opposition anti-sectarian parties candidate in the Syndicate of Engineers and Architects, the largest syndicate in Lebanon.

This opposition includes established ideological parties such as the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) and the Nasserist Popular Organization. They hail from a specific understanding of their role during and after the civil war as well as leftist ideological grounds that explicitly distinguish them from sectarian actors.Footnote30 Yet their embedded identity is not as strong as it used to be because, much like most established leftist organizations elsewhere, their ideology has not been sufficiently adapted to, and identified against, the changing structures of modern capitalism.Footnote31 For example, the party did not offer an alternative policy programme to the financial crisis, as much as it condemned the financial elites and their practices and reiterated its criticism to global capitalism and the financialisation of the economy. It has also remained largely apologetic to Hezbollah despite its deeply anti-communist and sectarian project, under the pretense of Hezbollah’s military role in the liberation of South Lebanon and its successful military standoff against Israel. This, among other matters, has produced weaker and incoherent leftist identities. Moreover, these parties’ old guards have lost most of their margin of maneuver in the postwar sectarian system to sectarian parties; they have resorted to generous compromises with them to continue to exist in some form. This inevitably restricts the forms and margins of contention in which they participate.

In fact, in the case of the LCP, this combination of wearing leftist identity and partial collusion with sectarian parties at the leadership level has catalyzed an internal rift between a younger progressive generation and the old guards that long turned a blind eye to these problems. This rift has translated into an internal power struggle, especially after the October 2019 protests, in which the “communist youth” were visible and outspoken. One of the leading young figures in the party told the author in November 2021 that they were able to oust the “old leadership” of the party’s branch in Northern Lebanon and that they are building solidarity groups of unemployed young men across the impoverished north outside the “usual networks” of the party.Footnote32 These young cadres are also being introduced to communist ideas and their grievances are being channeled politically. This new “disjointed” identity making among the young communists has already taken contentious forms. My sources described how their group had several rounds of street fights with security forces and the army in an attempt to break away from what they believed is “state-sponsored pacification” of Tripoli’s revolutionary potential during the 2019 protests. Tripoli is one of the most impoverished and, consequently, most securitized cities in the country, whose residents have had to face the army every time they protested their living conditions. Dozens of its young men have been detained without trials and many others killed or tortured in the shadows. My interviewees insist that when Tripoli joined the nation-wide protests in 2019, “its [revolution] was intentionally turned into a carnival.”Footnote33 This diverges from the official party narrative, which, much like the liberal stance, celebrated the city’s “civilized” protest movement. Although the rebellious communist youth are far from attaining an embedded identity away from their party’s traditional line, their interactions and contentions, be it within their party or without it, are successfully developing their sense of shared interest. They are not only building networks amongst themselves and articulating their ideological positions in ways that differ from the established party line, they are also coordinating with other new opposition groups over specific common causes outside party lines.

At the same time, nascent opposition groups are building resourceful networks around shared interest while struggling to depart from the embeddedness of sectarian identities. A telling example of this predicament is independent MP Nehmat Frem’s “Watan al-Insan” movement, which aims to “build a country of freedom, sovereignty and of constructive coexistence in the service of the human beings.”Footnote34 Two observations from the event launching the movement reflect the embeddedness problematic at hand. First, Frem tried to frame the proposed “alternative” as the work of a group, a timid bid at nonsectarian grouping. But the interaction with the audience indicated that the invited guests and participants were defining this moment in terms of an already existing sectarian logic. Several guests articulated their belief in this alternative because Nehmat is “the son of the noble [read Maronite] politician George Frem.” Others highlighted the work Frem did “for his area”—his sectarian community. Secondly, the group behind Frem’s movement is all-Christian, except for one speaker, Hassan al-Hussaini, who started his pitch to the audience by referring to himself as “your brother Hassan.” Al-Hussaini’s upfront articulation of sectarian “tolerance” is indicative of the constraining sectarian identification and the limits of political imagination.

But many young, liberal and cosmopolitan activists deny being victims of implicit or embedded sectarianism. They mock the sectarian coexistence narrative as cliché and fake. For them, sectarianism stands in the way of merit-based categorization, in which their skills and education are recognized and rewarded for what they are. They take offense in sectarianism when it imposes its categories on them in some cultural occasion or social gathering in their hometown, for instance. But, in many instances, they remain at the mercy of the “sectarian ghost,”Footnote35 where sectarianism “pervades discourse” of their opposition to sectarianism. Their biases toward their sect or against it appear in the contestations they choose to participate in, the slogans they choose to carry and the narrative to which they choose to subscribe. For example, many activists born to Shi‘a families focus their contestation on Hezbollah, while others from the same background are apologetic toward Hezbollah. The same can be said about activists from other sects. This demonstrates the inherent limitations in claiming homogeneity outside the experiences of their own sect, which in turn limits the possibilities of a nonsectarian identity that organically encompasses all sects in its articulation of “the Other.”

This pattern of opposition began to surface as early as 2011, when, inspired by the Arab Spring, activists across the country took to the streets under the overarching slogan: al-sha‘b yurid isqat al-nizam al-ta’ifi (the people want the fall of the sectarian regime).Footnote36 But they did not agree on where the regime begins and where it ends. One of the organizers of these early protests in 2011 informed the author that some of the activists preparing for the protest brochure and slogan fought over whether late Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri was sectarian, given that he provided education for people “from different sects.”Footnote37 Others refused to consider Hezbollah’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah part of the consociational regime, given the common framing of Hezbollah as a resistance movement. At that time, not only political imagination was limited by sectarian identities, but also sectarian identities were imposing on activists to the extent that their objective was to find forms of contention, and forms of organization, that are not impeded by the all-imposing sectarian identification. Consequently, activists resorted to “exhibitionistic acts” and “symbolic victories” achieved through coordinated demand-based contentions.Footnote38 They managed the contradictions that the “sectarian ghost” brings to their organization by relying on what Carole Kerbage calls “politics by coincidence,” in which activists resort to “spontaneous organizational forms” with “emotional discourse” and “loose demands” for the sake of protesting.Footnote39 In so doing, they serve their motive to contest the system without however having to face acute and imposing sect-based biases and, subsequently, without substantial results. In practice, this meant that protests were called for without any shared political objective beyond voicing slogans against the consociational system and showing solidarity with other Arab uprisings at the time. It also meant that the vast majority of the 2011 protests took place in Beirut, with very few and less popular protests taking place in Byblos and other cities. When a significant event or incident in relation to revolutions took place in another country, Lebanon’s activists would capitalize on its “unifying solidarity” to call for another weekend protest. When asked about what gains were made from these protests, one of the leading organizers answered: “In one rainy march in Beirut [against the consociational system], we were able to attract more than 10,000 people.”Footnote40 Inevitably, several months of occasional weekend protests with loud revolutionary music accompanying hundreds of protesters who only agree broadly on the slogan of toppling the regime ended with no political alternative.

In a society where modes of mobilization and identification have been systematically reduced to sects,Footnote41 individuals struggle to formulate shared interests that can materialize outside sectarianism.Footnote42 And even when they do, they struggle to sustain this formulation in the absence of an alternative identity that is both a practice and a source of inspiration to make sense of the world around them. Instead, each of them interacts with a social world that sectarianism and sectarian power sharing has embedded—family relations,Footnote43 neighborhoods, urban spaces,Footnote44 public and private workplaces, media, among other structures and superstructures—which, as Mona Harb puts it, “lock them in.”Footnote45

The pervasiveness of sectarian identities and the limits of imagining a coherent alternative order are the result of the power of these structures. These clearly articulated and well-established identities are difficult to abandon without an alternative identification that can guide, and find alternative meaning, in a sectarian setting.Footnote46 Absent this alternative embedded identity, individuals, especially the youth, are increasingly joining newly and loosely formed organized opposition built around inconsistent performances of identity making but with a stronger sense of shared interest in an alternative political system that recognizes and rewards their academic and professional merits. Their weak nonsectarian public identity, however, still entails strategic concessions to the pervasiveness of sectarian identification to allow for a measure of mobilization without being divided.

In October 2019, this strategic concession manifested itself in the largest wave of protests in Lebanon’s postwar history. Activists promised to “topple the sectarian regime,” however under a new slogan: kilun ya‘ani kilun (all of them means all of them). The slogan was temporarily effective in responding to earlier contradictions amongst activists. It was an affirmative answer to all the malevolent “what about this sectarian leader?” questions that had divided activists and exposed their proximity to sectarian logic. The slogan was also effective for mobilizational purposes because it presented a kind of agreement (verbal contract) in which no one gets defensive over their respective “least-worst” sectarian leader, under the condition that everyone continuously and explicitly acknowledges that all six of them need to go: Saad Hariri, Walid Jumblatt, Samir Geagea, Michel Aoun, Nabih Berri and Hassan Nasrallah. Activists even made sure they printed and sprayed the six faces of the sectarian leaders across banners and walls. Some went further, complementing kilun ya‘ani kilun with wa za‘imi wahad mennon (and my [sect’s] leader is one of them). In practice, local protesters were reassured that their act of protesting against the consociational system was not indirectly serving “the other sect” in a game theory scenario, because they saw on television and social media how protesters in other regions (read: sects) were also protesting under the same slogan that excluded none of the sectarian pillars. In some areas, especially in Southern and Northern Lebanon, and perhaps for the first time in decades, protesters dared point fingers at their own sectarian leaders, confident in the knowledge that their counterparts from other sects were doing the same.Footnote47

When asked by reporters who they thought was responsible for the country’s problems, most protesters resorted to the pledged slogan of “all means all,” a veritable consociational slogan in and of itself, that represents all sects equally. Despite its effectiveness, this updated narrative of opposition did not break away from sectarian identities nor did it resolve earlier contradictions and offer a viable alternative identification through which people can belong and make sense of their surroundings. Instead, it did exactly the opposite. It underscored the exclusive pervasiveness and embeddedness of sectarian identities, even if only strategically. It allowed protesters, through this strategic concession, to effectively mobilize around a shared interest in socioeconomic demands.

It is thus not surprising that sectarian leaders were able to break this temporary pledge under which a broader opposition emerged, through textbook tactics of co-optation and coercion. The latter mostly manifested in two ways. First, protests witnessed some of the most violent forms of state repression of peaceful protests in postwar history, in which hundreds were injured and a handful died.Footnote48 Second, sectarian thugs were often sent in to provoke and instigate violence amongst the protesters, torch their tents and symbols, in a bid to demotivate “peaceful” activists, mostly the cosmopolitan youth, from organizing and many ordinary people from participating. Co-optation, on the other hand, involved capitalizing on the pervasiveness of sectarian identities and the fragility of “spontaneous organization.” Organized sectarian parties were able to use the credibility of nation-wide protests to push for their own messages. For instance, because many protests were called for without organized invitations, sectarian parties began using the same methods to call for anonymous protests that subtly make sect-related claims, exposing, in the process, the inconsistency of anti-sectarian performances.

For the purpose of this paper, how sects capitalize on the embeddedness of sectarian identities is more important and telling. Two particular instances of such capitalization are worth highlighting. The first involves Nasrallah’s speeches and their aftermath days after the protests began. Nasrallah warned his followers of a foreign conspiracy behind the protests, invoking cases in the region as a warning and asking them to withdraw from the streets.Footnote49 In response, the majority of protesters in—or coming from—predominantly Shi‘a areas withdrew from the streets. Activists continue to reminisce this as a defining moment in the trajectory of the protest movement.Footnote50 One prominent nonsectarian activist who often is apologetic to Hezbollah calls Nasrallah’s notorious speech “Hezbollah’s Naksa speech,” in which it announced its allegiance to sectarian warlords against the people.Footnote51 The second is the reaction to former Prime Minister Saad Hariri’s resignation. Hariri framed his resignation as a response to the demands of the people. Of course, activists rushed to celebrate this as their first victory, demanding the resignation of others, particularly Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri and President Aoun. However, many protesters in Sunni-majority neighborhoods were shaken by Hariri’s resignation, lest their own sect be sacrificed and the rest hold their sectarian seats. Whilst the “all means all” contract was losing traction among many ordinary people for fear that one sectarian leader was scapegoated, other activists were desperately holding on to what they saw as a political victory against the regime, taking credit for Hariri’s resignation and hoping that it would have a domino effect on other sectarian leaders.

By early 2020, the protest momentum decreased significantly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the aforementioned tactics. But the magnitude of the initial protests and its increasingly political demands pushed aspiring political elites to organize themselves in what they hoped would become a recognized political opposition to the sectarian system. Hundreds of local groups emerged, including a handful of new political parties: LiHaqqi, Minteshreen, Lana and Taqaddom, among others.Footnote52 Their members often describe themselves as “born out of the October Revolution” and “based on the principle of all means all.” In presenting themselves this way, however, they, again, carry along the same initial limitations of these slogans in relation to sectarian identities and now struggle to appeal to people to make them identify differently. Absent this ideological breakthrough, new and old opposition groups are either going to be content with the limits of their opposition or gradually succumb to sectarian polarization. This is most evident with members of these groups who managed to win seats in parliament in 2022 under broad slogans of change and accountability.Footnote53

Conclusion: within and without the consociational parliament

Lebanon’s postwar sectarian elites have reached a defining moment, in which the very economic model they have relied on to secure political loyalties and sustain their patronage networks has all but collapsed. To be sure, Lebanon’s consociational power-sharing arrangement has experienced deep crises before, leading, for instance, to a protracted civil war between 1975 and 1990. The 1989 Taif Accord that recalibrated the sectarian balance of power was supposed to protect against such deep crises, however. Two factors make this crisis unprecedented and defining, and thus make the study of the possibilities for political alternatives more pressing. Firstly, since 2019, the country has witnessed one of the largest incidents of wealth destruction per capita in modern history through a combination of fiscal, currency, banking and economic crises.Footnote54 Secondly, despite the large-scale humanitarian tragedy that is consequently unfolding, Lebanon’s traditional external patrons, France and Saudi Arabia, are either unwilling or unable to save the day.Footnote55 Hence Lebanon’s sectarian elites have found themselves in a different geopolitical terrain: the same powers that previously ensured the reproduction of the country’s consociational power-sharing in internationally sponsored pacts have prioritized more strategic regional crises and potentially more rewarding diplomacy.Footnote56

In historical-comparative terms, this situation is a recipe for profound social and political transformation, especially given the consequences of these crises on the clientelist and disciplinary ensemble employed by sectarian leaders to maintain their grip on power and preempt the emergence of political alternatives beyond sectarian politics.Footnote57 Indeed, as this paper has shown, new political movements have emerged, with some receiving regional and international recognition. The aspirations for a “new Lebanon,” especially among the liberal and urban-educated youth, have never been more urgent. But these aspirations are, as this paper has contended, “locked in” an embedded sectarian identification that continues to impede the emergence of a popular and viable opposition. The outcome is precisely the “morbidity” that, for Antonio Gramsci,Footnote58 characterizes crises in historical transition. Despite deep and multi-layered crises tearing up Lebanon postwar consociational order, the alternative order is not yet envisioned by oppositional and aspiring elites, given that, as per this paper’s examination, sectarian identification and consociational logic continue to dominate political life. Decades of strictly sectarian social and political experiences, structured by the institutions of postwar consociationalism, have limited the articulation and practice of opposition to sectarianism and thus has undermined the prospects of imagining a viable alternative.

Established and newly formed political opposition struggles to recruit and mobilize beyond its own “network” of shared interest, as discussed in this paper, albeit they have gained some seats in parliament, and, subsequently, recognition from regional and international actors. This is why, as early as the first parliamentary session, the so-called “change-oriented bloc” gathering oppositional MPs explicitly suggested that its objective is primarily to stay as a bloc, to maintain a sense of unity, while acknowledging serious disagreements among its members on matters that can, directly or indirectly, drag them into sectarian polarization of strictly consociational parliament.Footnote59 This is not surprising, however, given the kind of politics practiced over the past decade, between broad and narrow demands, with which this paper has grappled. For what brings these oppositional MPs together is not a common political project per se but, instead, the need by members of oppositional groups with disjointed identities to project, even if only symbolically, a sense of unity that can, incrementally, inspire an alternative identity to that of embedded sectarianism.

In practice, this will drive the new parliamentarians to do exactly what their initial protest groups managed to do outside the consociational system: to adapt to their limitations by oscillating between narrow social demands and broad progressive slogans which, at the outset, seem to avoid the “sectarian ghost,” and thus often invites significant numbers to the streets. But, as this paper has shown, this kind of opposition time and again proves to be a concession to sectarianism, and, eventually, falls victim of its own limits. In identifying this recurring concession, this paper addresses the deep influence of embedded sectarian identities on the articulation and organization of opposition, and argues that this sectarian pervasiveness partly explains the contradictions and limitations of the opposition in its pursuit of “desectarianization.”Footnote60

Although the paper relies on the assumption that the current political and economic crisis is a recipe for political transformation, it does not assume that such transformation is inevitable, as if the recipe will “bake” itself. If anything, such extraordinary circumstances may invite even more stubborn affiliation with sectarian identities across social segments, because sectarian parties and affiliation will be the last support line for an increasingly vulnerable society with the erosion of the state. In that sense, the crisis can invite more sectarian identification rather than an incremental arrival at an embedded nonsectarian identity.

Additionally, in moments of group struggle, sectarian identities can draw in, through the dynamics of the struggle and shared narrative of victimhood, “emotionally charged identification” of honor in perceived group resilience.Footnote61 Calhoun considers honor to be “imperative in a way interests are not,”Footnote62 which is indicative of the limits of merit-based oppositional identities when sectarian identities are embedded. This can particularly be the case in extraordinary circumstances, which lead people to undertake extraordinary actions, “lest their core sense of self be radically undermined.”Footnote63 Such identification imperatively requires interest-threatening or even life-threatening action—which is very different from the calculated and interest-based logic of oppositional identification. Calhoun underscores the incommensurability between identity in ordinary times, or “the way people reconcile interests in everyday life,” and the imperative identity that mitigates human insecurity through ‘honor-driven sense of self’ that can enable or even require people to be “brave to the point of apparent foolishness.”Footnote64

Therefore, while some of the opposition’s aspiring elites look down at sectarian affiliation at times of social and economic crisis, wondering, from a position of privilege, “what more” should happen and how much deeper should the consociational system fail for people to give up their sects, many ordinary people, regardless of their circumstances, will continue to show pride in their respective sects. In a precise reflection of the exclusively sectarian imaginaire, many people imagine their source of deprivation in the midst of a crisis, and their perception of their difficulties, in relative terms to other sects. Speaking to ordinary people in Southern Lebanon today, for instance, many reiterated this relativity. They measure how much Hezbollah is “providing them” in terms of fuel and food, as well as other basic needs, compared to, for instance, Sunni-majority Tripoli, in which poverty is widespread and resources are much more scarce. This is indeed the limit of political imagination when sectarian identities are embedded. Of course, it is not as explicit and dominating among the opposition. But, it is the “ghost,” as AbiYaghi et al.Footnote65 describe it, that chases the imagination of aspirant elites, who, until the time of writing, have only successfully mobilized beyond their groups through either narrow demands or broad demands against the consociational arrangement, both of which were temporarily effective, as this paper argues, precisely because they avoided challenging sectarian identities, and, by avoiding it, conceded to its pervasiveness.

This presents a dangerous and cyclical paradox for Lebanon’s opposition. Absent a viable political project that allows people to re-imagine their differences and interests outside sectarianism, sectarian identities will outlast the very political-economic system it relied on after the war. Nonetheless, any serious attempt at forming alternative embedded identities will require a complete divorce from a consociational order that ensures there is a sectarian logic to every aspect of life, meaning the process of constructing a parallel set of values, meanings, ideas, culture and indeed social relations that would have to exist alongside the existing sectarian society, without interacting or relying on its economic activity. Then, oppositional political actors forge their new identities in practice, invite membership and organize based on newly articulated embedded identity. In practice, this has only ever existed when the opposition was sponsored by another state, which invests in a parallel society that adopts its embedded identity—for example, the Soviet Union’s relationship with numerous communist-nationalist opposition groups in the Global South, or when the opposition was in exile, hence socially and economically autonomous from the society it wants to change. Otherwise, the opposition in Lebanon will continue to rely on narrow or broad demands, both of which can yield cracks in the consociational system, but cannot override the identities that give meaning to this order. Hence the thirteen or so oppositional MPs made it through to a parliament run, and designed, in the service of consociationalism. A sense of possibility among the opposition is maintained, without arriving at a sense of viability.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ibrahim Halawi

Ibrahim Halawi is a Lecturer in International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. His current research focuses on political opposition, social movements, and states in the Middle East.

Notes

1 Max Weiss, “The Historiography of Sectarianism in Lebanon,” History Compass 7, no. 1 (2009): 141–54.

2 Bassel F. Salloukh, Rabie Barakat, Jinan S. Al-Habbal, Lara W. Khattab, and Shoghig Mikaelian, The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon (London: Pluto Press, 2015).

3 Bassel F. Salloukh, “Taif and the Lebanese State the Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 25, no. 1 (2019): 43–60.

4 John Nagle and Tamirace Fakhoury, Resisting Sextarianism: Queer Activism in Postwar Lebanon (London: Zed Books, 2021).

5 Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel, eds., Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

6 Bassel F. Salloukh, “The State of Consociationalism in Lebanon,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics (2023): 1–20.

7 See Sam Heller’s commentary (Sam Heller, “Economic Collapse–Not Elections–Will Shape Lebanon’s Future” (The Century Foundation, 2022), https://tcf.org/content/commentary/economic-collapse-not-elections-will-shape-lebanons-future/?agreed=1&agreed=1 (accessed 24 May 2022)) on the collapse of the economy and the persisting patterns of sectarian voting behaviour, which indeed manifested itself to a large extent in the outcome of the parliamentary elections in May 2022.

8 Asef Bayat, “The Arab Spring and Revolutionary Theory: An Intervention in a Debate,” Journal of Historical Sociology 34, no. 2 (2021): 393–400; Mona Khneisser, “The Marketing of Protest and Antinomies of Collective Organization in Lebanon,” Critical Sociology 45, no. 7–8 (2019): 1111–32.

9 Nadine Sika, “Civil Society and the Rise of Unconventional Modes of Youth Participation in the MENA,” Middle East Law and Governance 10, no. 3 (2018): 237–63.

10 Janine A. Clark and Bassel F. Salloukh, “Elite Strategies, Civil Society, and Sectarian Identities in Postwar Lebanon,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 45, no. 4 (2013): 731–49; Jamil Mouawad and Hannes Bauman, “In Search of the Lebanese State,” The Arab Studies Journal 25, no. 1 (2017): 60–5; Salloukh et al., The Politics of Sectarianism; Salloukh, “Taif and the Lebanese State.”

11 Ulises A. Mejias, “The Limits of Networks as Models for Organizing the Social,” New Media & Society 12, no. 4 (2010): 603–17; Jad Melki and Sarah Mallat, “Digital Activism: Efficacies and Burdens of Social Media for Civic Activism,” Arab Media & Society 19, no. Fall 2014 (2014): 1–15.

12 Hashemi and Postel, Sectarianization; Carmen Geha, Civil Society and Political Reform in Lebanon and Libya: Transition and Constraint (London: Routledge, 2016); Rima Majed, “For a Sociology of Sectarianism: Bridging the Disciplinary Gaps beyond the “Deeply Divided Societies” Paradigm,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of the Middle East, edited by A. Salvatore, S. Hanafi, and K. Obuse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

13 Hashemi and Postel, Sectarianization.

14 For example, K. Anthony Appiah and Amy Gutmann, Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996); Julie Bettie, Women Without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2014); Karen Gallas, Sometimes I Can Be Anything: Power, Gender, and Identity in a Primary Classroom (New York: Teachers College Press, 1997); Laura E. Hirshfield and Tiffany D. Joseph, “‘We Need a Woman, We Need a Black Woman’: Gender, Race, and Identity Taxation in the Academy,” Gender and Education 24, no. 2 (2012): 213–27; Awad El Karim M. Ibrahim, “Becoming Black: Rap and Hip-Hop, Race, Gender, Identity, and the Politics of ESL Learning,” TESOL Quarterly 33, no. 3 (1999): 349–69; Jane Kroger, “Gender and Identity: The Intersection of Structure, Content, and Context,” Sex Roles 36, no. 11/12 (1997): 747–70; Shompa Lahiri, Indians in Britain: Anglo-Indian Encounters, Race and Identity, 1880-1930 (London: F. Cass, 2000); Matthew D. O’Hara and Andrew B. Fisher. Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009); William S. Penn, As We Are Now: Mixblood Essays on Race and Identity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998); Laurajane Smith, “Heritage, Gender and Identity,” in The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, edited by Peter Howard and Brian Graham (London: Routledge, 2008), 159–78; Daniel A. Yon, Elusive Culture: Schooling, Race, and Identity in Global Times. SUNY Series, Identities in the Classroom (Ithaca: State University of New York Press, 2000); Joseph P. Helou and Marcello Mollica, “Inter-Communal Relations in the Context of a Sectarian Society: Communal Fear Spawns Everyday Practices and Coping Mechanisms among the Maronites of Lebanon,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 28, no. 4 (2022): 393–412.

15 Pierre Bourdieu, “Symbolic Power,” Critique of Anthropology 4, no. 13–14 (1979): 77–85.

16 Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, “Beyond “Identity,” Theory and Society 29, no. 1 (2000): 1–47.

17 Thomas Poell, Rasha Abdulla, Bernhard Rieder, Robbert Woltering, and Liesbeth Zack, “Protest Leadership in the Age of Social Media,” Information, Communication & Society 19, no. 7 (2016): 994–1014.

18 For example, Neil Burron, “Counter-Hegemony in Latin America? Understanding Emerging Multipolarity through a Gramscian Lens,” Revue Québécoise de Droit International 2014 (2020): 33–68; William Carroll, “Hegemony and Counter-Hegemony in a Global Field,” Studies in Social Justice 1, no. 1 (2007): 36–66; William K. Carroll and R. S. Ratner, “Between Leninism and Radical Pluralism: Gramscian Reflections on Counter-Hegemony and the New Social Movements,” Critical Sociology 20, no. 2 (1994): 3–26; William K. Carroll, and R. S. Ratner, “Social Movements and Counter-Hegemony: Lessons from the Field,” New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 4, no. 1 (2010): 7–22; William Todd Evans, “Counter-Hegemony at Work: Resistance, Contradiction and Emergent Culture inside a Worker-Occupied Hotel,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 51, (2007): 33–68; Hyug Baeg Im, “Hegemony and Counter-Hegemony in Gramsci,” Asian Perspective 15, no. 1 (1991): 123–56; Christian Karner, “Austrian Counter-Hegemony: Critiquing Ethnic Exclusion and Globalization,” Ethnicities 7, no. 1 (2007): 82–115; Lilian Miles and Richard Croucher, “Gramsci, Counter-Hegemony and Labour Union–Civil Society Organisation Coalitions in Malaysia,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 43, no. 3 (2013): 413–27; Adam David Morton, Unravelling Gramsci: Hegemony and Passive Revolution in the Global Political Economy (London: Pluto Press, 2007); Sanjay K. Ramesh, “Hegemony, Anti-Hegemony and Counter-Hegemony: Control, Resistance and Coups in Fiji” (PhD thesis submitted to the University of Technology, Sydney, 2008), https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/20249/2/Whole02.pdf (accessed 12 August 2021); Hernan Thomas, Lucas Becerra, and Santiago Garrido. “Socio-Technical Dynamics of Counter-Hegemony and Resistance,” in Critical Studies of Innovation, edited by Benoît Godin and Dominique Vinck (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), 182–200.

19 Melani Cammett, “Lebanon, the Sectarian Identity Test Lab” (The Century Foundation, 2019), https://tcf.org/content/report/lebanon-sectarian-identity-test-lab/ (accessed 16 January 2023); Salloukh et al., The Politics of Sectarianism.

20 Rania Maktabi, “The Lebanese Census of 1932 Revisited: Who Are the Lebanese?,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 26, no. 2 (1999): 219–41; Nagle and Fakhoury, Resisting Sextarianism.

21 Henri Tajfel and John Turner, “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict,” in Intergroup Relations: Essential Readings, Key Readings in Social Psychology (New York, NY: Psychology Press, 2001), 94–109; Melani Cammett, “Lebanon, the Sectarian Identity Test Lab” presents a good case for including this approach in the study of Lebanon’s sectarian politics.

22 Charles Tilly, “Armed Force, Regimes, and Contention in Europe since 1650,” Irregular Armed Forces and their Role in Politics and State Formation, edited by Diane E. Davis and Anthony W. Pereira (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003b), 37–81, 4; Krinsky John and Ann Mische, “Formations and Formalisms: Charles Tilly and the Paradox of the Actor,” Annual Review of Sociology 39, no. 1 (2013): 1–26.

23 Charles Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978); Tilly, “Armed Force, Regimes, and Contention.”

24 Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution, 3–17.

25 Tilly, “Armed Force, Regimes, and Contention,” 4.

26 Ibid., 3–18.

27 Ozlem Altan-Olcay and Ahmet Icduygu, “Mapping Civil Society in the Middle East: The Cases of Egypt, Lebanon and Turkey,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 39, no. 2 (2012): 157–79; Rosita Di Peri and Daniel Meier, eds., Lebanon Facing the Arab Uprisings (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017); Geha, Civil Society and Political Reform; Mona Harb, “Assessing Youth Exclusion through Discourse and Policy Analysis: The Case of Lebanon” (IAI Istituto Affari Internazionali, 2016), https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/assessing-youth-exclusion-through-discourse-and-policy-analysis-case-lebanon (accessed 8 July 2021); Fuad Musallam, “‘Failure in the Air’: Activist Narratives, in-Group Story-Telling, and Keeping Political Possibility Alive in Lebanon,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 26, no. 1 (2020): 30–47; Maha Yahya, “The Summer of Our Discontent: Sects and Citizens in Lebanon and Iraq” (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2017), https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Maha_Discontent_Final_Web.pdf (accessed 16 January 2023).

28 Altan-Olcay and Icduygu, “Mapping Civil Society”; Jessica Leigh Doyle, “Civil Society as Ideology in the Middle East: A Critical Perspective,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 43, no. 3 (2016): 403–22.

29 Khneisser, “The Marketing of Protest”; Mona Khneisser, “The Specter of “Politics” and Ghosts of “Alternatives” past: Lebanese “Civil Society” and the Antinomies of Contemporary Politics,” Critical Sociology 46, no. 3 (2020): 359–77.

30 Rosa Velasco Muñoz, “The Lebanese Communist Party: Continuity against All Odds,” in Communist Parties in the Middle East: 100 Years of History, edited by Laura Feliu and Ferran Izquierdo Brichs. London: Routledge, 2019), 90–108.

31 Rana Farah, “The Decline of the Lebanese Communist Party in the Postwar Period (1990-2016)” (MA thesis submitted to the University of Balamand, 2019); for a novel and thoughtful take on the evolution of Lebanese communist identity and ideas through the work of one of its most influential figures, Ziad Rahbani, see Sune Haugbolle, “The Leftist, the Liberal, and the Space in between: Ziad Rahbani and Everyday Ideology,” The Arab Studies Journal 24, no. 1 (2016): 168–90.

32 Anonymous interview with a youth leader in the LCP, 5 August 2020, Beirut, Lebanon.

33 Anonymous gathering with three left-wing activists in Tripoli, 2 August 2020, one of whom is a member of the LCP.

34 See official website: https://projectwatan.com/index-en.php.

35 Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi, Myriam Catusse, and Miriam Younes, “From Isqat An-Nizam at-Ta’ifi to the Garbage Crisis Movement: Political Identities and Antisectarian Movements,” in Lebanon Facing the Arab Uprisings: Constraints and Adaptation, edited by Rosita Di Peri and Daniel Meier. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017), 73–91.

36 Tamirace Fakhoury, “Do Power-Sharing Systems Behave Differently amid Regional Uprisings? Lebanon in the Arab Protest Wave,” The Middle East Journal 68, no. 4 (2014): 505–20.

37 Anonymous interview with co-founder of the protest movement ‘Al-Sha‘ab Yurid Isqat al-Nizam’, 18 July 2020, via Skype.

38 Carole Kerbage, “Politics of Coincidence: The Harak Confronts Its ‘Peoples’” (The Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, 2016), https://www.kas.de/documents/252038/253252/7_dokument_dok_pdf_52386_2.pdf/677a44c5-684f-cdbc-c4ec-76399a18ae0a?version=1.0&t=1539647500399 (accessed 18 July 2021).

39 Ibid.

40 From the same interview with co-founder of the protest movement ‘Al-Sha‘ab Yurid Isqat al-Nizam’, 18 July 2020, via Skype.

41 Salloukh et al., The Politics of Sectarianism.

42 Elinor Bray-Collins, “Sectarianism from Below: Youth Politics in Post-War Lebanon” (PhD thesis submitted to the University of Toronto, 2016).

43 Lara Deeb, “Beyond Sectarianism: Intermarriage and Social Difference in Lebanon,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 52, no. 2 (2020): 215–28.

44 Hiba Bou Akr, For the War Yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).

45 Harb, “Assessing Youth Exclusion,” 15–6.

46 Charles Tilly, “Political Identities in Changing Polities,” Social Research: An International Quarterly 70, no. 2 (2003): 605–19 does a particularly good job at zooming in on how identity making is affected by ‘small-scale production of excuses, explanations, and apologies’ to make sense of larger issues and their impact on everyday life.

47 Ibrahim Halawi and Bassel F. Salloukh, “Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will after the 17 October Protests in Lebanon,” Middle East Law and Governance 12, no. 3 (2020): 322–34.

48 For context on repression and violence during the 2019 protests, see Bassem Mroue and Zeina Karam, “Lebanon Clashes Threaten to Crack Open Fault Lines,” Associated Press News, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/ap-top-news-united-nations-beirut-lebanon-middle-east-7aa5a45ff9464efda3066aaed729c322 (accessed 28 May 2022).

49 Bassel F. Salloukh, “The Sectarian Image Reversed: The Role of Geopolitics in Hezbollah’s Domestic Politics,” in Sectarianism and International Relations (POMEPS Studies 38, March 2020), https://pomeps.org/the-sectarian-image-reversed-the-role-of-geopolitics-in-hezbollahs-domestic-politics (accessed 16 January 2023).

50 Based on informal interviews with activists during protests, conducted in Beirut between 12 and 15 October 2019.

51 Anonymous interview, 6 August 2020, Beirut, Lebanon.

52 Lihaqqi’s official website: http://lihaqqi.org/, Minteshreen: https://minteshreen.com/en, Taqaddom: https://taqaddomlb.org/home.

53 For a comprehensive and early overview of the election results and what it means to the newcomers, see Paul Salem, Fadi Nassar, Carmen Geha, Bilal Saab, and Brian Katulis, “Special Briefing: Lebanese Elections Reshape Political Scene” (Middle East Institute, 2022), https://www.mei.edu/blog/special-briefing-lebanese-elections-reshape-political-scene (accessed 20 May 2022).

54 See the World Bank’s (2021) comprehensive report on the magnitude of the crisis: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/01/lebanon-sinking-into-one-of-the-most-severe-global-crises-episodes.

55 Michael Young, “Enemies of the Good” (Carnegie Middle East Center, 2021). https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/86028 (accessed 27 April 2022).

56 Hasan Alhasan and Layal Alghoozi, “The Fragile Diplomacy of Saudi–Iranian de-Escalation” IISS (2021), https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2021/12/the-fragile-diplomacy-of-saudi-iranian-de-escalation/ (accessed 23 February 2022).

57 Clark and Salloukh, “Elite Strategies, Civil Society”; Salloukh et al., The Politics of Sectarianism.

58 Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Goeffrey Nowell Smith (New York: International Publishers, 1971).

59 MP Halime Kaakour, one of the oppositional candidates elected to parliament, shared these sentiments in an interview on MTV on 31 May 2022, right after the first parliamentary session. This tweet from her personal account reiterates one of the key statements made in this interview: https://twitter.com/halime_el/status/1531626387018244096?s=20&t=15LWrifBRx7RLI35_dQogg.

60 Simon Mabon, “Desectarianization: Looking beyond the Sectarianization of Middle Eastern Politics,” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 17, no. 4 (2019): 23–35.

61 Craig Calhoun, “The Problem of Identity in Collective Action,” in Macro-Micro Linkages in Sociology. American Sociological Association Presidential Series: Notes on Nursing Theories (Vol. 6), edited by Joan Huber (California: Sage Publications, 1991), 51–75, 64.

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.

64 Ibid., 53, 68.

65 AbiYaghi et al., “From Isqat An-Nizam at-Ta’ifi to the Garbage Crisis Movement.”