ABSTRACT

This article examines American Israeli relations since the establishment of the state in 1948 to the present. It presents a combination of historical and theoretical analysis. It uses the concept of ‘special relationship’ to analyse major issues in the evolution of bilateral relations including US support for Israel’s independence, Arab-Israeli wars, Palestinian terrorism, mediation, peace agreements, foreign aid, public opinion, attitudes of American Jews and a look at the future. The article reveals strong strategic ties between the two allies but also cracks that threaten to damage the special relationship, including the loss of bipartisanship support, new strategic priorities in US foreign policy, political polarisation, distancing among American Jews, demographic changes, and effects of the 2023 judicial reform in Israel.

In December 1962, President John F. Kennedy told Israeli Foreign Minister Gilda Meir: ‘The United States has a special relationship with Israel in the Middle East, really comparable only to that which it has with Britain over a wide range of world affairs’.Footnote1 The one with Britain is understandable but the one with Israel requires an explanation. It rests on a unique combination of ‘hard elements’, such as strategic interests, and ‘soft elements’, such as values.Footnote2 After World War II, the United States became a superpower with global strategic aspirations and interests, while those of Israel were limited and regional. The Cold War fostered strategic American interests in Israel when revolutionary Arab states like Egypt, Iraq, and Syria joined the Soviet Bloc while Israel aligned with the US-led Western bloc.Footnote3 This interest decreased after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in 1989, but within a decade other joint strategic interests developed in the face of a new global threat: radical Islam and terrorist Islamic organisations such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).Footnote4

The soft elements in the special relationship have included similar features in the history of the two nations. These ranged from the Judeo-Christian roots of American society, to nation building through immigration waves, to the pioneering spirit that beat in the hearts of the American and Israeli founding fathers, to conquest of frontiers and wilderness, to shared values such as liberal democracy, to significant support of the American Jewish community and Evangelical Christians, to supportive public opinion. Israel’s military might and strategic interests have changed over the years, while the soft elements have remained fairly constant. In practice, the special relationship meant American military and economic aid, trade benefits, supply of modern and advanced weapons, joint development of sophisticated weapons, intelligence sharing, deterrence against superior powers, defence at hostile international organisations such the United Nations and its agencies, and mediation to end the Arab-Israeli conflict. The special relationship has mostly preserved the closeness between the two states but has not prevented occasional disagreements and confrontations over such issues as Israeli communities in the West Bank and Gaza, or the nuclear deal that Washington and its European allies signed with Iran in 2015.Footnote5

Seeds of the special relationship emerged already prior to Israel’s establishment. After World War II and the Holocaust, the US strongly supported the November 1947 UN Partition Resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish and an Arab state in Mandatory Palestine. President Harry S. Truman extended de facto recognition to Israel immediately after its birth. His decision to support the establishment of Israel was exceptional and controversial. At the beginning of the Cold War, Washington collaborated with Moscow at the expense of its main ally, Britain, which wanted to preserve its mandatory rule over the area. Truman also ignored the negative advice of his secretaries of state and defence, George C. Marshall and James Forrestal, who opposed Jewish immigration to Palestine, the partition resolution, and recognition of Israel.Footnote6 Critics argued that Truman supported Israel only because he needed the ‘Jewish Vote’ in the 1946 congressional elections and the 1948 presidential elections. Yet Truman explained his policy in simple terms: if two national entities claim the same piece of land, to prevent conflict and war, partition into two states was the most logical solution.Footnote7

At times, Truman’s support for the establishment of Israel was not fully secured. Following the violent Arab response to the partition resolution, Washington imposed embargo on arms sales to the region. Paradoxically, during its entire war of independence (1948–9), Israel received arms from the Soviet Union via Czechoslovakia. Moreover, Warren Austin, the US Ambassador to the UN, stated in March 1948 that since Arab-Jewish violence would not allow peaceful implementation of the partition resolution, Washington would support a UN temporary trusteeship in Palestine. Apparently, Truman didn’t authorise this change in US policy. When Britain ended the mandate on midnight, 14 May 1948, and Israel declared independence, Truman offered the nascent Jewish state de facto recognition within minutes.

Wars and terrorism

Arab-Israeli wars tested the US-Israel special relationship. After Israel’s War of Independence, a serious test came in the 1956–7 Suez-Sinai crisis. Israel, Britain, and France attacked Egypt in the autumn of 1956 and Israel captured the Sinai Peninsula. The coordinated attack surprised the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He demanded from Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion to unconditionally withdraw from Sinai and threatened to remove tax credits American Jews could claim for donations to Israel. The pressure succeeded and Israel withdrew in return for an American commitment to guarantee the Red Sea freedom of navigation to Eilat. Washington forfeited an opportunity to exchange land for peace.

Three Arab-Israeli wars erupted between 1967 and 1973: the June 1967 Six-Day War, the 1969–70 War of Attrition, primarily with Egypt, and the October 1973 Yom Kippur War with Egypt and Syria.Footnote8 The Six-Day war was a major swift victory over Egypt and Syria, two staunch allies of Moscow, as well as Jordan (a US ally).Footnote9 It was also an achievement for the US in the context of the Cold War, because at the time it was fighting a losing war in Vietnam. The Soviet active participation alongside the Egyptian army in the War of Attrition was a dangerous challenge that could have led to a direct military confrontation between Washington and Moscow. A similar scenario occurred towards the end of the 1973 War, when Moscow threatened to intervene if Israel failed to honour the ceasefire agreement brokered by two superpowers. Soviet naval forces equipped with nuclear weapons crossed the Turkish straits into the Mediterranean, only to be met with an American nuclear alert. At that point, the sides – Israel, Egypt and Syria implemented a ceasefire agreement.

The coordinated surprise attack of Egypt and Syria on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar revealed two additional challenges to US-Israeli relations. The Arab states imposed an oil embargo on the US and its European allies that caused a sharp increase in the oil prices and economic recessions. Western governments and groups blamed the close US-Israel relationship for the embargo. The war lasted about three weeks (October 6–25), Israel’s losses in weapons were substantial and needed urgent American replenishment. The administration of President Richard Nixon debated how to airlift equipment. It finally did but due to Arab threats, Washington’s European allies refused landing and refuelling of American cargo planes. The war motivated Egypt and Israel to reach a historic peace agreement in 1979.

In subsequent years violence was more limited and became a subnational war between Israel and the Palestinians, who couldn’t rely any longer on the Arab states to destroy Israel and therefore intensified their terrorism. In 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon to evict the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that had built widespread terrorist infrastructure in the country, especially in South Lebanon, which it had used to attack Israeli towns and villages. The administration of President Ronald Reagan was concerned about civilian casualties and the occupation of parts of the capital Beirut and demanded to stop the war. An American peacekeeping force accompanied the departure of PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat and his men to Tunis, but on 23 October 1983, Hezbollah, a Lebanese Shiite terror organisation, sent a truck bomb to the US camp in Beirut killing 241 Americans. Reagan ordered the force to withdraw.

Palestinian terrorism has never stopped, but in the 21st century it became more institutional and intensive. From September 2000 to February 2005, the PLO-dominated Palestinian Authority (PA), established in 1994 as part of the PLO-Israel Oslo ‘peace’ process to rule the West Bank and Gaza Palestinian population that had hitherto been controlled by Israel, waged a major terrorist campaign against Israeli civilians (often euphemised as ‘al-Aqsa Intifada’, or the ‘Second Intifada’). They conducted suicide bombings in Israeli buses, malls, restaurants, nightclubs, schools, coffee shops, and hotels. Thousands of Israelis and Palestinians were killed and wounded.Footnote10 Washington severely criticised Arafat but failed to stop him. In September 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew its armed forces from Gaza and in June 2007 Hamas, an extreme Islamic terrorist organisation, took over the Strip from the PA by force. Hamas and the Islamic Jihad terrorist group have become Iranian proxies and turned Gaza into a base for terror attacks on Israel. In response, every few years Israel had to conduct limited military operations in Gaza to stop them. The US has justified Israel’s right to defend itself but was concerned with the consequences: casualties and damage, fear of triggering a regional war, weakening the PA, and preventing conflict resolution.

Mediation in the Arab-Israeli conflict

From the beginning of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the US invested substantial efforts in mediation between the two sides.Footnote11 The main reasons were the cost to Israel and the perception that support for Israel was causing crises and difficulties in US relations with the Arab world. The first attempt occurred in 1949 when the US jointly with France and Turkey was a member of the Palestine Reconciliation Commission. In 1953–55, Ambassador Eric Johnston offered a water-sharing plan to Israel, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon hoping it would pave the road to peace. These initial efforts failed because the Arab states were preparing for another war to destroy Israel, not for peace.

In the Six-Day War Israel conquered vast territories – the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. In November 1967, the US was instrumental in orchestrating UN Security Council Resolution 242 laying down principles for peace, notably Israel’s withdrawal from territories (rather than the territories) taken in the war in return for peace. But the PLO rejected the resolution as a ‘Zionist ploy’, as did most Arab states, which two months had endorsed the ‘Three No’s’ regarding Arab-Israeli reconciliation: no peace with Israel, no negotiations with Israel, and no recognition of Israel. In December 1969, during the Egyptian-initiated War of Attrition, Secretary of State William Rogers issued the first US detailed peace plan, based on Resolution 242. Both Israel and the Arabs, however, rejected the plan seeing only the concessions they had to make and not the gains they would receive in return. Despite this rejection and massive Soviet military involvement in Egypt, which expanded and intensified after the Six Day War, in August 1970, Rogers successfully mediated an end to the War of Attrition and laid the foundations for sole US mediation of the conflict in the coming years.

The 1973 War opened up new opportunities for serious US mediation. Israel and Egypt paid heavy prices that influenced their motivation and willingness to reach a settlement. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat moved Egypt from the Soviet to the American camp and thus increased the potential for US mediation. Since then, Washington has been the only party with good relations with both sides. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger mediated ceasefire and disengagement agreements in the wake of the war, and a major Egyptian-Israeli interim agreement two years later, which paved the way for the March 1979 Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty.Footnote12

The conflict’s two most significant peace processes – with Egypt and the PLO (the Oslo process) – began with secret direct talks between the parties with Washington out of the picture, but the American involvement was critical to finalise and implement the agreements. President Jimmy Carter, whose relations with Israel were tense and occasionally hostile, personally mediated between Sadat and PM Menachem Begin. In November 1977, they signed the Camp David Accords and in March 1979 a fully-fledged peace treaty. Israel agreed to withdraw from all of Sinai in return for recognition and genuine peace including open borders, diplomatic relations, tourism, and trade.

After PM Yitzhak Rabin and Arafat reached an agreement on mutual recognition in secret talks held in Oslo, in September 1993 President Bill Clinton sponsored an impressive signing ceremony on the White House lawn. In October 1994, he helped with the signing of a peace agreement between Jordan and Israel. Four years later, in October 1998, when the implementation of the Oslo process ran into difficulties, Clinton invited Arafat and PM Benjamin Netanyahu to a summit at Wye River where the two signed another interim agreement. In July 2000, the US president made another effort to mediate peace between Israel and the Palestinians and invited Israeli PM Ehud Barak and Arafat to Camp David. Barak and later Clinton himself proposed far-reaching concessions, only to be rejected by Arafat.

President George W. Bush formulated a Roadmap for Israeli-Palestinian Peace and convened a summit peace conference at Annapolis. He was the first US president to explicitly support a Palestinian state, but also ruled out Israel’s return to the June 1967 borders. In November 2007, Bush invited PM Ehud Olmert and PA Chairman Mahmoud Abbas to a summit in Annapolis. The summit did facilitate direct negotiations and produced another generous peace proposal, but Abbas did not respond and this effort also failed.

President Barak Obama was one of the most pro-Palestinian presidents in American history. He first tried to advance peace via special envoy George Mitchell and then via Secretary of State John Kerry. He pressured Netanyahu to publicly support the two-state solution – Israel, and a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip living side by side in peace – and to freeze construction activities in the West Bank. These were Abbas’s conditions for renewing negotiations with Israel. In June 2009, Netanyahu announced his support for the establishment of a Palestinian state (in the ‘Bar-Ilan Speech’), and in November froze settlement construction for a period of 10 months; yet Abbas refused to renew negotiations.

President Donald J. Trump made the last US attempt to reach Israeli-Palestinian peace in his ambitious ‘Deal of the Century’.Footnote13 The plan comprised two parts – economic and political. The economic part was presented at a workshop in Bahrain in June 2019 with the participation of businesspeople and politicians from around the world. The idea was to prepare a comprehensive package for economic development in the West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, and Egypt, with a proposed budget of $50 billion. The Palestinians boycotted the workshop and demanded that the Arab states not participate, claiming that the economic part was no more than a ploy to buy welfare at the expense of the Palestinian aspiration for independence. The political portion was released on 28 January 2020, and offered the Palestinians a state over 70% of the West Bank plus Gaza and a capital on the periphery of East Jerusalem. Israel accepted the plan in principle, but the Palestinians rejected it outright.

The Palestinian rejections of so many peace plans reaffirmed Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban’s famous quip that ‘they never missed an opportunity to miss peace’. They have never been interested in ending the conflict with Israel and even the Oslo process was designed to continue the conflict with Israel from improved strategic positions in the West Bank and Gaza.Footnote14 Detailed American peace plans such as those of Rogers and Trump proved stillborn. US mediation succeeded with Egypt and Jordan but failed with the Palestinians, partly because it had a far greater leverage over Israel and much less over the Palestinians.

Foreign aid

US aid to Israel consisted of economic and military components.Footnote15 The economic grants ended in 1959 and from then until 1985 aid consisted mostly of loans, which Israel repaid. Israel began buying American arms only in 1962. The amount of aid increased substantially after the 1973 War mainly to replenish empty depots, and after the signing of the peace agreement with Egypt. Since then, the aid’s amount and components have been determined by the Qualitative Military Edge formula (QME), codified in a 2008 law that committed the US to ensuring Israel’s ability ‘to counter and defeat any credible conventional military threat from any individual state or possible coalition of states or from non-state actors’.Footnote16 The formula has enabled Israel to receive the most modern and high-quality weapons that the US produces, such as F-35 fighter jets.

As shown in below, in 1946–2023 US aid to Israel amounted to some $159 billion, most of which was used to purchase weapons in the US. Starting in 1990, the amount and components of this aid have been set in memorandum of understanding (MOU) for ten-year periods. The idea was to set a basic continuing format without the need to have prolonged consultations and discussions each year. The last MOU was signed between the Obama administration and the Israeli government on 14 September 2016, and it provided for an overall framework of $38 billion for the decade between 2019 and 2028. shows that of this sum, each year, $3.3 billion were designated for military aid and half-a-billion for missile defence. The actual allocations still need annual Congressional approval, and the progressive branch of the Democratic Party may have reservations and conditions as it expressed in recent years.

Table 1. Total US foreign aid obligations to Israel: 1946–2023 (Current, or non-inflation-adjusted, US dollars in millions).

Over the past two decades, Israel has been increasingly threatened by rockets and missiles, and consequently collaborated with the US on multi-layer missile defence, especially in the fields of joint development and manufacturing and technology transfer. The missile defence systems include Iron Dome for short range, David’s Sling for short and medium range, and three generations of Arrow missiles for long-range high trajectory interception. shows that so far, the total American investment in missile defence has reached $9.9 billion. As a lesson from the 1973 War, the US maintains depos with large amounts of equipment and munitions in Israel, including missiles, precision-guided munitions, and vehicles. These repositories are intended for emergency use by both allies. The two armies also carry out exercises intended to strengthen their fitness and capabilities.

Use of the term ‘aid’ in the context of US-Israeli defence relations is misleading. The more accurate and appropriate term would be ‘investment’ that provides enormous profits for both sides. First, most of the resources are invested in the American defence industries towards acquisition of advanced weapons, and not in Israel. Washington receives ongoing critical intelligence from Jerusalem of major value, combat experience that tests and improves the weapons, joint development of weapons that are among the most sophisticated in the world, original and innovative technologies, and proven combat doctrines. Israel also works with the US in the areas of cyber warfare and nuclear proliferation.

The scope of aid to Israel should be compared to US expenditure on defending its allies in other places in the world.Footnote17 The US maintains some 150,000 soldiers in various locations abroad, including some 50,000 in Japan, 30,000 in South Korea, and 40,000 in Germany. The annual expense of maintaining these forces ranges between $85 billion and $100 billion. Consequently, for example, the annual military aid to Japan costs some $27 billion, the aid to Germany some $21 billion, and to South Korea $15 billion. The defence of Europe costs some $36 billion. Added to these expenses are significant sums, usually annual joint manoeuvres with allies and regular and special operational activities such as naval patrols in the Persian Gulf, the South China Sea, the Baltic Sea, and the North Sea. In this respect, the value of military aid to Israel is much greater and contributes more to US national security than it seems.

Public opinion

Public opinion has always been a significant factor in the US-Israel special relationship because it influences policymakers and Congress members. American public has always viewed Israel favourably and supported its policies towards the Arab states and the Palestinians.Footnote18 In the last decade, however, there has been some erosion in these attitudes.

Analysis of long-term trends based on polling data refers to three major areas: views of Israel, sympathies with Israel vs. the Palestinians and socio-demographic distributions.

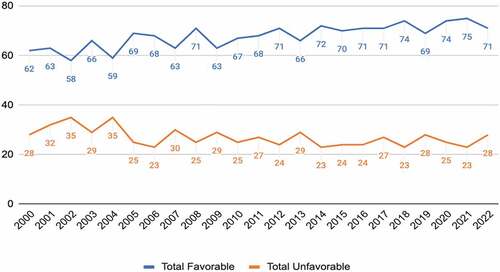

Americans have always held highly favourable views of Israel and long-term trends were mostly stable from 2000 to 2022. Substantial majorities of between two-thirds and three-quarters of respondents held favourable opinions of Israel, while between one-third and one-quarter held an unfavourable opinion. Favourability ratings of Israel increased from 62% in 2000 to 71% in 2022 (See below).

During the first decade of this century, the favourability scores were between 58% and 71% and the average was 64%. Since 2012, all but two results were over 70% and the average climbed to 68%. The highest favourable-to-unfavourable ratios, 74% to 23% and 74% to 25%, were respectively registered in 2018 and 2019 during Trump’s term, and probably reflected his warm and close ties with Israel. The unfavorability score in 2022 was identical to the one found in 2000. The highest unfavorability score, 35%, was registered twice, in 2002 and 2004 and probably reflected dissatisfaction with ‘al-Aqsa Intifada’.

Similar majorities of Americans have considered Israel a ‘close’ and ‘important US ally’ and thought the US support of Israel has been ‘adequate’ or ‘too little’. The data and analysis of the general long-term trends imply issue consistency. Those who held favourable views of Israel were also likely to consider Israel a close ally or a friend of the US and believed the US should strongly support Israel.

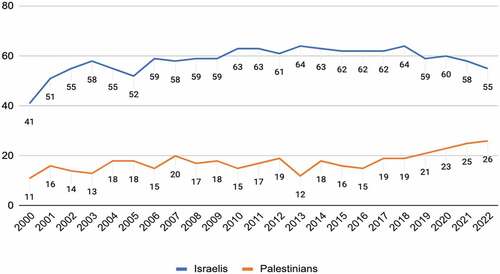

In 1947–77, Gallup polls were asking which side inspired more sympathy in the ‘Middle East situation’: Israelis or Arabs. In 1978, the question was changed by pitting Israelis against the ‘Palestinians’ instead of ‘Arabs’. The long-term trends reveal mild fluctuations overtime influenced mostly by violence and negotiations. During the 1967 War, the American public condemned the Arab aggression and was very concerned about Israel’s fate. The score that year was 56% for Israelis versus only 4% for the Arabs. The highest percentage was recorded during the 1990–91 Gulf crisis and war: 64% sympathised more with Israelis and only 7% with the Palestinians. The reasons for the new high were Saddam Hussein’s missile attacks on Israel and Palestinian enthusiastic support for his invasion and occupation of Kuwait.

shows sympathy distributions over the past 22 years. In 2013 and 2018, the results matched the previous high record of 64% in Israel’s favour. In 2022, a majority still sympathised more with Israel by a ratio of 2 to 1, but in the last four years, the trends showed gradual erosion in the Israeli scores and gradual increase in the Palestinian scores. The reason could have been the political polarisation in the US as the polls revealed considerable decrease in the scores of Democrats and liberals, who might have been alienated by the close relations between Netanyahu and Trump and the absence of a peace process with the Palestinians. Decreases were also found in the attitudes of young people, minorities, and even American Jews.

American Jewry

One major foundation of the special relationship has been the support of American Jews.Footnote19 Until recently, the American Jewish community was the largest in the world, and it is now the largest outside of Israel. After the Holocaust, American Jews were very involved in the events leading to the establishment of Israel, cared for its survival and wellbeing, and have strongly supported close US-Israeli ties. This was especially visible during the 1967 and 1973 wars, when Israel’s survival seemed to be at stake. Most American Jews were proud of their ancient homeland, admired its ability to survive in a very hostile region and its enormous achievements in a variety of areas such as agriculture, medicine, water desalination, solar energy, and digital technologies. In recent years, however, cracks have appeared in this relationship.

Two theories described the relations of US Jewry to Israel: ‘civil religion’ and ‘distancing’. The first said that to many secular Jews, attachment to Israel became the only way to express their Jewish identity.Footnote20 By raising and donating money, visiting Israel, following closely news from the state and the region, and participating in political activism in organisations such as the pro-Israel lobby American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), they felt connected to Judaism. ‘The distancing theory’ argued the opposite and raised questions about the depth of the American Jewish commitment to Israel. It said that Jews were increasingly distancing themselves from Israel, socially, culturally, ethnically, and emotionally and didn’t consider Israel any longer as a significant part of their Jewish identity.Footnote21 Distancing was originally applied to generational gaps between young and older Jews, and has been extended in recent years to older Jewish groups, especially to liberals and Democrats.

Two factors have influenced the negative changes in attitudes: levels of religiosity and political orientation. Those who are more Orthodox and more engaged with the Jewish community have been more pro-Israel than the other groups. The high level of mixed marriages and general decline in religion in the US have eroded attachment to Israel. There is a debate about the distancing of young American Jews from Israel. Graizbord suggested that young American Jews are accustomed to the American model of Jewish identity that centres on a very specific concept of religion.Footnote22 Israel and Zionism challenge that model. Sasson, Kadushin and Saxe argued that while the young are indeed more distant now there is a life-cycle element, and as Jews age they generally tend to become less distant from Israel.Footnote23 While Waxman claimed that American young adult Jews were more critical of Israeli government policies and felt more sympathetic towards the Palestinians than older American Jews.Footnote24 But all can agree that the young are much less religious and less engaged with the community, and consequently are less interested in Israel. Those who are interested, receive much of the information about Israel and the conflict with the Palestinians from distorted and questionable sources in the social media, and on campuses where they are brainwashed and intimidated by the anti-Israel Boycotts, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

For decades, Israel enjoyed bipartisanship support in the US Congress, with both Democrats and Republicans strongly and enthusiastically supporting the Jewish State.Footnote25 In the last fifteen years, however, the political polarisation in the US, the tilt to the left in the Democratic party, and certain policies of Netanyahu have damaged bipartisanship support. The political polarisation reduced bipartisanship in many areas of American society including attitudes towards Israel. The progressive branch in the Democratic Party under the leadership of Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren has been gaining more power and influence, has supported the BDS movement, cutting and conditioning military aid, and demanding pressure and sanctions on Israel to change its policies in the conflict with the Palestinians. Netanyahu supported Republican candidates for president, Mitt Romney in 2012 and Trump in 2016 and 2020, and created very close relationship with Trump. Netanyahu confronted Obama on the Iran nuclear deal and the peace process with the Palestinians. Since about 70% of American Jews are Democrats,Footnote26 the rift between Israel and the party has had a significant adverse influence on their attitudes towards Israel.Footnote27

Other recent developments may have contributed to erosion in US Jewry’s support for Israel. Political power in the US relies on voting turnout and effective lobby organisations. US Jewry suffered from a serious political split in its ranks as AIPAC has been increasingly challenged by a leftist Jewish lobby organisation, J Street, created in November 2007 to challenge AIPAC’s alleged ‘rightist orientation’. Anti-Zionism has been spreading inside and outside the Jewish community, preached and disseminated by such intellectuals as Peter Beinart and organisations such as ‘Jewish Voice for Peace’ and ‘IfNotNow’.

All in all, the attitudes of American Jews towards Israel were very supportive and favourable from the establishment of the Jewish State to the beginning of this century. They are still highly favourable but there are signs of cracks caused by dramatic political changes and severe political polarisation both in Israel and the US.Footnote28 Liberal American Jews have argued that Israel today has abandoned fundamentals of Judaism, while Israeli leaders responded by accusing American Jews of abandoning Israel. The two theories of ‘civil religion’ and ‘distancing’ are not mutually exclusive. Civil religion still works for many Jews, but many others have indeed been distancing themselves from Israel.

A forward look

The US-Israel special relationship is based on three principal foundations: strategic interests, joint values and ideals, and support of the Jewish community. Three major processes are currently threatening these foundations: American disengagement from the Middle East, compromising values in Israel, and demographic trends in the next 25 years. US strategic interests in the Middle East are changing. Washington doesn’t depend any longer on Arab oil for itself and its European allies. Three successive American presidents – Obama, Trump, and Biden – defined Asia as the most critical region for US foreign policy, and China as the No. 1 competitor for power and influence in this century.Footnote29 Obama called this strategy ‘Pivot Asia’, Trump declared a trade war against Beijing, and Biden established two strategic alliances to contain the Chinese ambitions in Asia: AUKUS consisting of Australia, Britain, and the US, and the ‘Quad’, consisting of the US, Australia, Japan, and India. Currently, Washington has also placed the Russian war in Ukraine high on its foreign policy agenda. The US is concerned with the Iranian nuclear programme but like the EU and NATO and unlike Israel does not deem it as imminent or important as the other global threats. This approach seems to diminish the strategic importance of Israel to the US.

Perceptions about the attempted judicial reform of the present Israeli government have eroded the joint values the two allies have cherished. Democracy expansion and retention has always been a major US foreign policy goal. American leaders have always praised Israel as the only democracy in the entire Middle East and described it as a major pillar of the special relationship. Democracy is maintained via clear separation between the three branches of government: the executive, legislative, and judicial. Like other parliamentary democracies, there has never been a real distinction between the executive and the legislative branches in Israel, with the government effectively controlling its Knesset members via stiff coalition disciplinary measures. Nor does Israel have a constitution, with relations among the branches traditionally developed and kept through common sense and mutual respect.

Established on 29 December 2022, the sixth Netanyahu government argued that the legal system, primarily the Supreme Court, has wielded excessive power over the other branches and proposed a major reform to fix it. The opposition swiftly accused the government of seeking nothing short of a regime change that would transform Israel into an autocracy, if not a dictatorship, with mass demonstrations and civil disobedience spreading across the country. President Biden and his senior officials were concerned with the plan and the protests and repeatedly told Netanyahu that US-Israeli relations are based on shared values and interests and that the proposed reform contradicts democratic values, must be carried out carefully and slowly, and win broad support among the opposition parties and the public.Footnote30 Initially, Netanyahu ignored the warnings, but the rapidly spreading turbulence forced him to freeze the plan and accept an invitation from President Yitzhak Herzog to negotiate with the opposition a plan that all can endorse. Even if the talks succeed, the crisis has already further alienated American liberals, Democrats and Jews.

The third threat is evolving from projected major changes in US demographic trends. Whites are losing considerable percentages of their share in the population while minorities, mostly Hispanics (Americans whose origins are in the Latin American countries), African Americans and Asians are increasing their share. Hispanics are the fastest growing minority group in the US: by 2030 they would reach 75 million or 21% of the total population, in 2040 the number would rise to 88 million or 24% of the population, and in 2050 it will grow to 100 million or 26% of the population.Footnote31

Hispanics have had mixed feelings about Israel due to a combination of national, ethnic, and religious factors. They are much less familiar with Israel and are more concerned with US relations with neighbouring Central and Latin American countries. They are also Catholics who usually support Israel less than other Christian denominations. Blacks are also identified with Israel less than other races in American society. Israel’s enemies in the US have been trying to win the hearts and minds of African Americans by comparing Israelis to American whites and the Palestinians to American blacks. Many pro-Palestinian groups have also brainwashed blacks to believe that Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and Israeli Arabs is like the Apartheid treatment of blacks in South Africa.

In the coming decade these demographic changes will have far-reaching effects on many areas of politics, society, and the economy in the US. By building coalitions and collaborating with each other, the minority groups could exercise significant influence on US politics and foreign policy. Traditionally, minority groups have supported the Democratic Party, which has been more attentive to their needs and much less supportive of Israel.

The US-Israel special relationship has evolved through decades of close collaboration and yielded many advantages to both allies. They will have to pursue continuing intensive efforts to keep it at the current level.Footnote32 The main requirement for future collaboration is listening. The two states will have to better understand the interests and limitations of each side. The three major processes described above require substantial Israeli and American efforts to stop the erosion and rebuild a new platform for close cooperation in the next several decades.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eytan Gilboa

Eytan Gilboa is Professor of International Communication Emeritus at Bar-Ilan University, Israel.

Notes

1. Gilboa, American Public Opinion, 1.

2. Safran, Israel: The Embattled Ally; Tal, The Making of an Alliance; and Ross, Doomed to Succeed.

3. Mart, Eye on Israel.

4. Gilboa and Inbar, US-Israeli Relations.

5. Ben-Zvi, The United States and Israel; Shalom, “The United States and the Israeli Settlements”; and Shalom, “Israel, the United States.”

6. Cohen, Truman and Israel.

7. Truman, Years of Trial and Hope, 184.

8. Herzog, The Arab-Israeli Wars.

9. Oren, Six Days of War.

10. Karsh, Arafat’s War.

11. This section is based on Quandt, Peace Process; and Ross, The Missing Peace.

12. Indyk, Master of the Game.

13. The White House, Peace to Prosperity.

14. Karsh, The Oslo Disaster; Hirschfeld, “Ten Ways The Palestinians Failed”; and Schwartz and Gilboa, “The False Readiness Theory.”

15. This section is based on Gilboa, “American Contributions,” 20–23; Sharp, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel; and Wu, “Interest or influence?”

16. Wunderle and Briere, U.S. Foreign Policy, 1.

17. Organski, The $36 Billion Bargain; Kirchick, “Quit Harping On U.S. Aid To Israel”; and Frisch, “Myth: Israel Is the Largest Beneficiary.”

18. This section is based on Gilboa, American Public Opinion Towards Israel; Gilboa, The American Public and Israel; Gilboa, “What Do Americans Think of Israel?”; and Gilboa, “Americans’ Shifting Views.”

19. Based on Gilboa, American Public Opinion Towards Israel, 68–80; and Gilboa and Bloch, “The Rift between American Jews and Israel.”

20. Cohen, American Modernity and Jewish Identity.

21. Heilman, “Editor’s Introduction to the Distancing Hypothesis”; and Cohen and Kelman, “Thinking About Distancing from Israel.”

22. Graizbord, The New Zionists.

23. Sasson, Kadushin, and Saxe, “Trends in American Jewish Attachment.”

24. Waxman, “Young American Jews and Israel.”

25. Cavari and Nyer, “From Bipartisanship to Dysergia”; and Kolander, America’s Israel.

26. Weisberg, The Politics of American Jews.

27. Rynhold, The Arab-Israeli Conflict.

28. Gordis, We Stand Divided; Kaplan, Our American Israel; Owen, 2016; Waxman, Trouble in the Tribe; and Sharansky and Troy, “Can American and Israeli Jews stay together.”

29. Warren and Bartley, US Foreign Policy and China.

30. Zakheim, “Netanyahu Is Playing With American Fire.”

31. Duffin, Forecast of the Hispanic Population.

32. Blackwill and Gordon, Repairing the U.S.-Israel relationship; and Waxman and Pressman, “The Rocky Future.”

Bibliography

- Ben-Zvi, A. The United States and Israel: The Limits of the Special Relationship. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Blackwill, R., and P. Gordon. Repairing the U.S.-Israel Relationship. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, 2016.

- Cavari, C., and N. Nyer. “From Bipartisanship to Dysergia: Trends in Congressional Actions toward Israel.” Israel Studies 19, no. 3 (2014): 1–28. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.19.3.1.

- Cohen, M. Truman and Israel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Cohen, S. American Modernity and Jewish Identity. New York: Tavistock, 1983.

- Cohen, S., and A. Y. Kelman. “Thinking about Distancing from Israel.” Contemporary Jewry 30, no. 2–3 (2010): 287–296. doi:10.1007/s12397-010-9053-4.

- Duffin, E. “Forecast of the Hispanic Population of the United States from 2016 to 2060.” Statista, October 5, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/251238/hispanic-population-of-the-us/

- Frisch, H. “Myth: Israel Is the Largest Beneficiary of US Military Aid.” BESA Center Perspectives, Paper no. 410, 2017. https://besacenter.org/perspectives-papers/dispelling-myth-israel-largest-beneficiary-us-military-aid/

- Gilboa, E. American Public Opinion toward Israel and the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1987.

- Gilboa, E. The American Public and Israel in the Twenty-First Century. Ramat-Gan: The BESA Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University, 2020a.

- Gilboa, E. “American Contributions to Israel’s National Security.” Strategic Assessment 23, no. 3 (2020b): 18–36.

- Gilboa, E. “What Do Americans Think of Israel? Long-Term Trends and Socio-Demographic Shifts.” In Currents, edited by L. Lavi, 1–10. Los Angeles: Nazarian Center for Israel Studies, UCLA, 2021a.

- Gilboa, E. “Americans’ Shifting Views on the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.” Middle East Quarterly 28, no. 4 (2021b): 1–12.

- Gilboa, E., and Y. Bloch-Elkon. “The Rift between American Jews and Israel.” In Palgrave International Handbook on Israel, edited by P. Kumaraswamy, 1–21. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-2717-0_71-1.

- Gilboa, E., and E. Inbar, eds. US-Israeli Relations in a New Era: Issues and Challenges after 9/11. London and New York: Routledge, 2009.

- Gordis, D. We Stand Divided: The Rift between American Jews and Israel. New York, NY: ECCO, HarperCollins, 2019.

- Graizbord, D. The New Zionists: Young American Jews, Jewish National Identity, and Israel. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2020.

- Heilman, S. “Editor’s Introduction to the Distancing Hypothesis Issue.” Contemporary Jewry 30, no. 2–3 (2010): 141–143. doi:10.1007/s12397-010-9057-0.

- Herzog, C. The Arab-Israeli Wars: War and Peace in the Middle East. New York: Vintage, 2005.

- Hirschfeld, Y. “Ten Ways The Palestinians Failed To Move Toward A State During Oslo.” Fathom Journal, June, 2019. https://fathomjournal.org/ten-ways-the-palestinians-failed-to-move-toward-a-state-during-oslo-yair-hirschfelds-critique-of-seth-anziskas-preventing-palestine/

- Indyk, M. Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022.

- Kaplan, A. Our American Israel: The Story of an Entangled Alliance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Karsh, E. Arafat’s War: The Man and His Battle for Israeli Conquest. New York, NY: Grove Press, 2004.

- Karsh, E. The Oslo Disaster. Ramat-Gan: BESA Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University, 2016.

- Kirchick, J. “Quit Harping on U.S. Aid to Israel: American Commitments to Asian and European Allies Require More Risk and Sacrifice.” The Atlantic, March 29, 2019. https://bit.ly/2AHa2lY

- Kolander, K. America’s Israel: The US Congress and American-Israeli Relations, 1967–1975. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2020.

- Mart, M. Eye on Israel: How America Came to View the Jewish State as an Ally. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006.

- Organski, A. F. K. The $36 Billion Bargain: Strategy and Politics in US Assistance to Israel. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

- Quandt, W. Peace Process. Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001.

- Ross, D. The Missing Peace: The inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004.

- Ross, D. Doomed to Succeed: The U.S.‐ Israel Relationship from Truman to Obama. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

- Rynhold, J. The Arab-Israeli Conflict in American Political Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Saad, L. “Americans Still Pro-Israel, Though Palestinians Gain Support.” The Gallup Poll, March 17, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/390737/americans-pro-israel-though-palestinians-gain-support.aspx

- Safran, N. Israel: The Embattled Ally. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

- Sasson, T., C. Kadushin, and L. Saxe. “Trends in American Jewish Attachment to Israel: An Assessment of the ‘Distancing’ Hypothesis.” Contemporary Jewry 30, no. 2–3 (2010): 297–319. doi:10.1007/s12397-010-9056-1.

- Schwartz, A., and E. Gilboa. “The False Readiness Theory: Explaining Failures to Negotiate Israeli-Palestinian Peace.” International Negotiation 28, no. 1 (2023): 126–154.

- Shalom, Z. “The United States and the Israeli Settlements: Time for a Change.” Strategic Assessment 15, no. 3 (2012): 73–84.

- Shalom, Z. “Israel, the United States, and the Nuclear Agreement with Iran: Insights and Implications.” Strategic Assessment 18, no. 4 (2016): 19–28.

- Sharansky, N., and G. Troy. “Can American and Israeli Jews Stay Together as on People?” Mosaic Magazine, July 9, 2018. Accessed January 12, 2019. https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/israel-zionism/2018/07/can-american-and-israeli-jews-stay-together-as-one-people/

- Sharp, P. U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2023.

- Tal, D. The Making of an Alliance: The Origins and Development of the US-Israel Relationship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Wang, Y. “Interest or Influence? An Empirical Study of U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel.” Israel Affairs 27, no. 4 (2021): 664–674. doi:10.1080/13537121.2021.1940553.

- Warren, A., and A. Bartley. US Foreign Policy and China: The Bush, Obama, Trump Administrations. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022.

- Waxman, D. Trouble in the Tribe: The American Jewish Conflict over Israel. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Waxman, D. “Young American Jews and Israel: Beyond Birthright and BDS.” Israel Studies 22, no. 3 (2017): 177–199. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.22.3.08.

- Waxman, D., and J. Pressman. “The Rocky Future of the US-Israeli Special Relationship.” The Washington Quarterly 44, no. 2 (2021): 75–93. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2021.1934999.

- Weisberg, H. The Politics of American Jews. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019.

- The White House. Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinians and the Israeli People. 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Peace-to-Prosperity-0120.pdf.

- Wunderle, W., and A. Briere. U.S. Foreign Policy and Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge. Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2008.

- Zakheim, D. S. “Netanyahu Is Playing With American Fire.” The Jerusalem Strategic Tribune, February, 2023. https://jstribune.com/zakheim-netanyahu-is-playing-with-american-fire/