Abstract

A qualitative empirical study of how higher education actors in Azerbaijan conceptualise excellence in teaching and how they promote it at different levels. The findings provide an original insight into how the concept of excellence is understood in the higher education of Azerbaijan. Intriguingly, there is no definition of teaching excellence nor an equivalent of it in the Azerbaijani language, let alone an existing policy on framing its standards. Furthermore, both socio-economic and cultural contributors make educational contexts different, thus affecting the conceptualisation of the phenomenon in focus. The article’s key findings indicate several serious barriers to achieving excellence, mainly associated with the apparent lack of a practical framework for defining the standards of excellence in teaching, measuring these and establishing a resources-enhanced system that can allow for continuity of the process.

Introduction

The Republic of Azerbaijan (hereafter Azerbaijan) is an emerging regional power that still has plenty of Soviet legacies to be found in different areas of being, including the country’s education system. Since regaining its independence in 1991, Azerbaijan adopted some measures to facilitate the integration of its educational frameworks with internationally accepted standards and procedures, nonetheless, one may argue, that those changes are slow in bringing long-lasting results (Isakhanli & Pashayeva, Citation2018). In 2009, the country adopted its Law on Education in a major reform intended to make these goals legally binding for all higher education institutions.

The law recognises both private and state institutions and requires them to maintain high standards of delivery in regard to quality assurance. While being understandable in its intentional essence, this legal imperative is one of the most debated topics in the field: the topic of excellence in teaching and its measurability in principle. A range of high-class research work confirms the difficulties that scholars and practitioners might face in determining the conceptual essence of ‘excellence’ and identifying criteria to measure excellence in teaching (Behari-Leak & Mckenna, Citation2017; Saunders & Blanco Ramírez, Citation2017; Wood & Su, Citation2017; Bartram et al., Citation2019; Matheson, Citation2019). Objectively, the process that can lead to achieving it is challenging in any region of the world and can vary from area to area, although this issue is more critical for the higher education systems of newly independent states or those that have regained independence after spending decades as non-sovereign entities.

Despite a series of higher education reforms delivered over several consecutive years in Azerbaijan the desired quality of teaching (and learning) is, arguably, far from being achieved (Isakhanli & Pashayeva, Citation2018). The reforms have been mainly related to quality assurance in its general sense and many policy level changes are being implemented at the institution level. Although many international projects, mainly supported by the European Commission and some specifically on teaching and learning, have contributed to the depth of the reforms, achieving excellence in teaching is still a challenge (Mammadova & Valiyev, Citation2020). On the normative side, a review of legal documents on education allows for stating that excellence in teaching is not framed as the core element of a separate strategy in Azerbaijani higher education. Arguably, in Azerbaijan, the complicated aspect of the situation is associated with the obvious lack of a precise definition, which might naturally have given some indication of how to measure it as well. A clear definition of excellence in teaching has been defined in the United Kingdom and elsewhere within a Teaching Excellence Framework policy document and it has encouraged higher education institutions to meet its expectations (Wood & Su, Citation2017). Moreover, the framework with its broad mechanisms has significantly affected the institutional conditions to improve the quality of teaching, if combined with new approaches to student-academic and leadership cooperation, although as highlighted by Brusoni et al. (Citation2014, p. 37) quality assurance agencies are probably challenged by being able to relate ‘the methods of quality assurance to excellence’. Having a clear frame of excellence in teaching is not considered to be a panacea, however, it is imperative that it is a component of a holistic reform process. In Azerbaijan, excellence in teaching is evidently a new notion, which makes its conceptualisation and promotion an even more complicated process. Locally, universities teach in a laissez-faire way rather than according to the excellence standards that are supposed to be regulated either by the institution itself, or the state, leading to preliminarily defined institutional or national recognition. This is all taking place despite a broad historic as well as fierce debate on how important the conceptual clarity for excellence in teaching is for the theory, as well as policymaking.

Indeed, when Glasner (Citation2003) underscored that a clear and universally-accepted definition of excellence in teaching could hardly be found, she was indirectly supported by Skelton (Citation2005, p. 21) who was insisting on the need to have a ‘conceptual clarity’ on the topic, at least at the level of where the phenomenon of excellence in teaching conceptually ‘resides’ (within the work of either students or teachers, or both, or within a particular discipline, an institution, an educational system). In a significant addition, there is an argument that excellence in teaching can be measured and controlled, and there can be a set of possibilities ‘crafted’ and employed to motivate teachers to meet the study objectives and learning criteria (Skelton, Citation2005). Nevertheless, as stated above, excellence in teaching has been studied in developed countries where socio-economic, cultural and educational contexts are different from Azerbaijan. This article also argues that with a set of identified clear-cut standards and balanced development programmes as well-created conditions, ‘excellence’ is possible to promote even in contextually different countries.

Considering the above, this article builds on the fundamental approaches to identify how excellence in teaching is conceptualised in the Azerbaijani context and what can be done to promote excellence in teaching at different levels: individual, institutional, or system-wide. The ambition of the study is to add value to a multi-dimensional scholarly debate on excellence in teaching in educational, socio-economic and cross-cultural contexts. Therefore, the main research questions are as follows:

How is the notion of ‘excellence in teaching’ conceptualised in Azerbaijani in the higher education context?

What can be done to promote ‘excellence in teaching’ at different levels: individual, departmental, institutional, or system-wide?

The research questions are answered in the following way: first, a literature review on excellence in teaching was completed to see the gap in the empirical developments. A theoretical framework based on the fundamental approaches of Skelton (Citation2005) to detect how excellence in teaching is conceptualised in the Azerbaijani context and what can be implemented in the process of pushing for excellence in teaching at the individual, institutional and national levels. The empirical part of the study contains an analysis of the data collected through semi-structured interviews with 15 educational experts in Azerbaijan, working at state and private universities as well as state agencies and international organisations. The final section includes the discussion on the findings and conclusive remarks outlined as the three-staged interdependent framework of achieving excellence in teaching as it is conceptualised by the experts.

Contextualising in the literature

Skelton (Citation2005) described four ‘ideal-type’ understandings of excellence in teaching in higher education and then compared and contrasted these understandings to shed light on the confusion. The four are traditional, performative, psychologised and critical approaches. Traditional understandings of excellence in teaching dominated when there was consent regarding what ‘a university’ and ‘teaching excellence’ were (Skelton, Citation2005). Nevertheless, institutional evolutionary diversification made this approach disappear. Performative understandings of excellence in teaching have originated from countries’ desire to keep up with globalisation trends. Its features include contributing to national economic performance through teaching, attracting students to courses that compete in the global higher education marketplace and regulating teaching to maximise individual, institutional and system performance. A psychologised understanding of excellence in teaching is concerned with the interaction between teacher and student and how this cooperation leads to meaning construction by students to achieve desired learning outcomes. Finally, critical understandings of excellence in teaching are formulated by critical theories, such as feminism and anti-racism. Here, knowledge, the curriculum and teaching and learning practices within universities are constructed by current socio-political and social interests.

Discussions on concepts of teaching excellence are often related to two other understandings: the scholarship of teaching and expert teacher. Kreber (Citation2002) stated that defining excellence in teaching, teaching expertise and the scholarship of teaching in a more precise way would improve teacher evaluation practices. To understand what is being evaluated one should first analyse how knowledge is created for teaching excellence, teaching expertise and the scholarship of teaching. According to Kreber (Citation2002), excellence in teaching is often based on judgements made about performance. Expert teachers, on the other hand, are those in continuous search of opportunities to construct and advance their knowledge: ‘the difference is that experts are excellent teachers, but excellent teachers are not necessarily experts’ (Kreber, Citation2002, p. 13). She concluded her analysis by arguing that scholars of teaching are both excellent teachers and expert teachers but one distinctive characteristic of scholars of teaching is that they make their knowledge public so that it can be peer-reviewed.

As noted by Readings (Citation1996, p. 24), ‘Excellence is not a fixed standard of judgment, but a qualifier whose meaning is fixed in relation to something else’. Although a lot of literature attempts to distinguish between ‘quality’ and ‘excellence’, ‘excellence’ is only comprehendible after it has been operationalised and that operationalisation is contextual. The concept of excellence is often used interchangeably with the concept of quality (Ball, Citation1985), although excellence is just one way of defining quality. The understanding of ‘quality’ in higher education is unclear (Brockerhoff et al., Citation2015). Staff, students and employers have differences in understanding of what quality in higher education is, thus making it hard to align with perceived standards (Harvey, Citation2003; Dicker et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, policy-level frameworks of excellence in teaching are expected to play a key role in the positioning of the quality assurance process. Related to this, Skelton (Citation2007) stated that the promotion of excellence in teaching may raise the status of teaching and it is possible that teachers will be more motivated to meet the set criteria.

Harvey and Green (Citation1993) identified two understandings of excellence in relation to quality. The first is excellence in relation to standards whereas the second is excellence as ‘zero defects’. In the first case, components of excellence are described, attainment of which is possible under exceptional circumstances. Institutions that possess superior resources and outstanding students can be considered excellent. According to Astin (Citation1990), the concept of excellence is usually ascribed to reputation and the level of institutional resources. In the case of ‘zero defects’, excellence is judged by conformance to the specifications. Harvey and Green (Citation1993, p. 15) stated that ‘a quality product or service is one which conforms exactly to specification and a quality producer or service provider is one whose output is consistently free of defects’. However, they posit that the purpose of higher education is not perfect conformity to specifications, rather it is supposed to reassure the critical and analytical development of students. As Ramsden and Moses (Citation1992) noted, the main aim of teaching is to make it possible for students to learn. However, there is still a gap in the evidence revealing the impact of excellence in teaching on student learning (Gunn & Fisk, Citation2013). Another criticism of excellence comes from Tomlinson et al. (Citation2020) who saw it as a feed to ‘neo-liberal market competition’. Some others (for example, Gourlay & Stevenson, Citation2017) declared that it is complicated to decrease the complexity and interconnectedness of excellence to fit the metrics of the framework. Yet, Bartram et al. (Citation2019) stated that although recognising, appreciating and rewarding excellent teaching is a good practice, the culture of measurement may impede genuine intentions.

It is important to have clear linkages between performance variances and incentives in any organisational setting and a higher education institution, as a social entity, is not an exception. In higher education rewards are granted as an incentive for excellence in teaching (McNaught & Anwyl, Citation1992; Warren & Plumb, Citation1999) or any other priorly determined achievements. Having such a reward system with clear metrics will allow educational institutions to compete with others, within or out of the industry, for access to funds and competitive staff members and provide the basis for their accountability (Strathern, Citation2000; Oravec, Citation2017). Moreover, much research suggests that the majority of teachers would want to be rewarded for their teaching (Gunn & Fisk, Citation2013). However, when designing such a system and developing metrics, it should not be based on the generic unit but rather on the discipline’s and institution’s specificity (Behari-Leak & McKenna, Citation2017).

Many scholars discuss caveats when designing award schemes. According to Gibbs (Citation2012), teaching awards may result in hostility between people at universities. Moreover, those who are not nominated may experience a decrease in their level of motivation (Madriaga & Morley, Citation2016). Studies indicate that constantly being pressed for excellence results in negative emotions, such as stress or anxiety (Stoeber & Rennert, Citation2008). The concept of excellence becomes a matter of survival and as such adds an emotional dimension to teachers’ professional lives (Bahia et al., Citation2017). Along with the negative outcomes stated in the literature, its positive outcomes are evident given the different educational, socio-economic, political and cultural contexts. Furthermore, research and national policies of excellence in teaching during the last decades have emphasised its importance and impacted on the quality of teaching.

All the studies reviewed above suggest that there is a gap in the conceptualisation of excellence in teaching as the majority of them have been conducted in developed or developing countries, which are contextually different from Azerbaijan. These variances are mainly rooted in the lack of resources and the conditions created for teaching staff for their continuous professional development since Azerbaijani higher education institutions are facing a shortage of funding (Silova, Citation2009; Moreno & Patrinos, Citation2019). The other factor is that excellence in teaching is not promoted at either institutional or policy levels. Providing excellence in teaching is a managerial task when seen through the lenses of the ‘theory of change’, which assumes how and why the initiative works and how the interventions were made in a particular context to witness the change. One of the assumptions is that if there is a clear-cut policy for making changes and planned inputs, then achieving outcomes is realistic, which means that the responsibility for the results lies mainly on the shoulders of leaders (Brockerhoff et al., Citation2014).

Methodology

The data for this study were drawn from representatives of eight different universities participating in the PETRA ERASMUS+ project and five independent higher education experts. In total, 15 experts were interviewed for the study, each interview varying approximately from 45 to 70 min. Methodologically, a ‘purposive sampling’ approach was engaged to single out a range of professionals who are already familiar with the notion and have experience of working with the project, otherwise based on the qualities the participants have (Etikan et al., Citation2016). Moreover, the interviewees are experts (denoted as E1–E15) in the field of education working for higher education institutions, or international organisations for more than 15 years (). The major assumption was that these participants would provide the study with more substantial (and empirically richer) data because of their experience within the project for three consecutive years, are familiar with the project-associated ideas and their implementation and are also aware of or are direct participants in the educational reforms in the country.

Data Collection

Interview protocols were prepared based on the literature review on excellence in teaching. There were four main categories of questions (with sub-questions). First, how has the state of teaching and learning changed at universities after the learning experiences they had over the last three years. Second, respondents were asked about the existence of institutional guidance for providing excellence in teaching. Third, the research tried to identify how actors understand ‘excellence’ and how they define it. Fourth, what reward systems exist at each institution and how do respondents tie the lack of existence of such a scheme to the provision of excellence in teaching.

The interviews were conducted in the period from February to July of 2020. Each participant was contacted directly either by phone or via email, asking for a voluntary contribution. The interview-associated timeframe was agreed upon with the interviewee to fit the respondent’s schedule. Interviews were conducted through Skype and Zoom platforms and all the interviews were recorded with the permission of the interviewee. The interviews were conducted in Azerbaijani, with the exception of one interviewee who expressed a desire to be interviewed in English. The interviews were transcribed verbatim by research assistants and all data was kept strictly confidential.

Thematic analysis

The data were analysed in two stages first, the data were analysed using inductive methods, meanings were given to data, and then they were coded. Deductive methods were used to cluster the codes into categories. The first and second researchers categorised the data separately, then, after several discussions, the consensus was achieved and the joint analysis was presented. Where pertinent, extracts from these interviews are used to illustrate points made.

Analysis

The findings represent how the participants conceptualised excellence in higher education. Their concepts can be clustered into three themes; the excellence of teachers, the excellent institutions and the form of promotion and reward systems that recognised excellence in teaching where revealed. Then the barrier to how these three functions of excellence can be achieved is presented. From this data, a conceptual map of perceived excellence is created, which can facilitate further research and application for an individual’s professional development and institutional action.

Excellent teacher

The notion of the excellent teacher contains two core competencies: attributes of the teacher as a learning agent and personal dispositions. In the first, the key attributes were: knowledge of subject, pedagogical practice and technological use and were enriched by good communication and a second language to facilitate access to international research to improve the first set of attributes. These attributes are susceptible to training and improvement. For example, one participant suggested that:

Subject knowledge is critical, but it may not suffice alone. Along with having a good command of subject knowledge, an excellent teacher should also possess pedagogical skills to deliver the knowledge. (E12)

The excellent teacher's personal dispositions, as well as theory competencies were important and these included being open to innovation in their teaching practice and above all the high motivation of the teacher to help students to learn. Typical comments from the participants included:

One may provide teachings and share knowledge but one may not grow without being open to innovation. (E2)

Excellence is not just about providing education. Because excellence is not solely laid in teaching or in educational technology, it is more related to communication with students. (E3)

The teacher’s personality itself is an important factor that affects students during communication. (E3)

Excellent institution

The interviews highlighted the importance of excellent institutional policy, ethos, agency, resources and their use to support teaching development through teaching and learning centres. These were thematised into five themes.

The importance of an ethos of student-centred teaching and learning

The participants consider student-centred teaching and learning as crucial in an institution’s teaching and learning policy.

We should have students accustomed to going to libraries and doing research by themselves. They need to be free and not dependent on teachers. (E4)

Such a pedagogical directive was thought to have a positive impact on the motivation of both students and teachers.

In excellent universities…. Teachers should motivate and boost students during teamwork. (E6)

Pedagogical scholarship

Frequently mentioned was the importance of publishing in high-ranking journals as an indicator of excellence, both in subject areas and in pedagogical practice.

Excellent institutions should provide the resources of time and support to encourage this scholarly activity, as it enhances the reputation of the institution as well as that of the teacher.

Positive ethos

A supportive learning environment as a prerequisite for excellence was mentioned by many participants. This manifested itself in an environment where teachers felt supported, cared for and given autonomy, which are the primary conditions to develop themselves to reach excellence.

The key to successful academic career development does not lie in individuals but rather in the environment. Due to an insufficient favourable teaching environment, people are unable to tap into their true potential. (E10)

Responsive to the needs of the student in the academy and beyond

Participants mentioned that excellent institutions should have a constant analysis of market needs and expectations for and of their students and keep track of their alumni and how well they flourish in their careers. Data from such tracking could enhance the programmes they deliver through curriculum innovation.

The excellence of a university is directly related to the graduates that are offered to the labour market. If those graduates meet the standards, then the university can be considered excellent. (E1)

Institution readiness

If institutions were to embrace these aspects of excellence, they would need to be ready and provide the resources required. This was partially true and feasible if resources are made available for professional development, since encouragement must be thoroughly planned by the institutions if they want to achieve excellence.

Without the resources, the assurance of quality is impossible. The absence of the right conditions and the right resources, such as teaching in a classroom without access to modern technologies, will be obstacles in the way to excellence. (E9)

The third issue identified in this functional approach towards quality of teaching was the explicit support for excellence through promotion, policy and reward systems.

Promotion, policy and reward systems

Promoting excellence through a well-developed framework of continuous development and reward system should serve as a precondition for recognising and promoting teaching excellence in any given institution. These policies clearly need to be grounded in fairness and framing the approach to excellence is becoming a necessity.

To provide university academic staff with a clear concept of excellence in teaching, it is important to develop a framework of what this means in the institution. The framework should identify the expectations and standards, how the system will work and what it entails as academic staff fit into the standards. It is important that institutions provide a full range of development opportunities in a systematic way, rather than at random as is the case within many Azerbaijani higher education institutions.

Continuous, ceaseless, regular improvement of teachers; is one of the most important factors. (E11)

The participants considered that to provide such recognition, any reward system would be part of the excellence framework, as all of the experts mentioned. The system should identify the criteria and financial rewards, rewards for publishing, or promotion opportunities, as any given teacher is assessed as ‘excellent’.

….in return for the individual’s contribution, a proportionate reward should be identified. The reward does not necessarily need to be financial, rather, it may be a certificate of honour or a praising text about the individual in the university newspaper. This would make people feel that they are being valued. (E1)

Many participants mentioned that the existence of such a system can motivate and their jobs will become meaningful as differentiation in rewarding is applied. However, it is essential that the system developed must be transparent, fair and workable.

Unfortunately, such a system does not exist. We have 31 departments where the productivity of the heads of departments is not the same but they receive the same amount of salary. (E1)

Barriers to excellence

The participants also considered the wide range of barriers to the successful enactment of these ideas. The themes that emerged were: lack of resources, managerial capabilities, the attitude of educational actors.

Lack of resources, especially time provided to teachers and space for student teaching, lack of financial support which makes plans unworkable, lack of contemporary learning resources, such as electronic or databases and translated textbooks, as well as technically well-equipped classrooms for face-to-face teaching and technical resources for online learning. Finally, excessive workloads discourage educators from being engaged in self-development activities.

Managerial styles include micromanagement, which deprives both teachers and students of the opportunity to engage in creativity and innovation; the quality and lack of capability of educational management to devise strategic direction and implement strategic imperatives.

Teachers’ identity refers to the attitude of educational actors to change and self-development. Concerns explored here covered teacher and student motivation, the preparedness of teachers to embrace change and shift from Soviet to post-Soviet teaching ideologies and its impact on their self-image of academics as a teacher rather than the researcher. This would require a new attunement to scholarly pedagogy, student-centred learning and commitment to other aspects of institutional change in seeking to develop an excellent teaching ethos.

Summary of findings

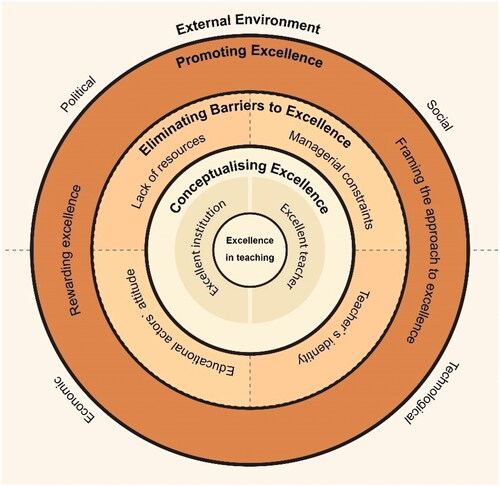

Based on the findings, the article proposes the following framework of excellence in teaching in similar contexts (). The framework has excellence in teaching in the centre. At first, one needs to understand the ‘why’ of excellence, which is the closest to the centre. While conceptualising excellence, academic staff refer to the framework that indicates the characteristics of excellence in teaching the standards and expectations, as well as the conditions and support offered by the university. Next, while conceptualising, the actors will realise some evident barriers to achieving the initiative, thus, it will help them to eliminate those barriers. The next circle, promoting excellence, one of the major concepts of the framework, is important to reinforce excellence. As it envisages that it needs to be framed with a clear-cut outcome-reward system. All of these do not happen in a vacuum, it works in interaction and interdependence with the external environment, such as political, socio-economic, cultural and technological.

Discussion and conclusion

The framework is developed based on the findings from this study. The results of this research work revealed how experts, who are also university teachers and decision-makers, understand excellence and how they conceptualise it at the individual, institutional and national levels. Concerning conceptualisation, the findings suggest that the respondents, while having some difficulties in providing a universal definition, managed to outline a range of factors that contribute to excellence. They indicated that excellence has multiple meanings and aspects. They have explained that excellence can be understood differently when viewed from different perspectives (Harvey & Green, Citation1993). Yet another reason the experts provided for difficulty defining excellence is that indicators for excellence are not stable; they change over time, which coincides with the ideas of Readings (Citation1996, p. 24) claiming that ‘excellence is not a fixed standard of judgment’. Numerous experts mentioned that excellence is a continuous process of development that coincides with the earlier study conducted by Wood and Su (Citation2017). However, for many it was hard to distinguish between the concepts of ‘quality’ and ‘excellence’, they used them interchangeably, similar to what Ball (Citation1985) stated, and E9 defines ‘excellence’ as an ongoing proliferation process, whereas ‘quality’ as a more constant state of the production. Nevertheless, some placed excellence higher than quality in the hierarchy where E7 states ‘excellence is highly dependent on the quality, excellence will be the peak point of a quality’. Thus, the existence of white or green paper stating the clear metrics of excellence in teaching, as well as a lack of standards within institutions, might have guided constituents of higher education in distinguishing between quality and excellence.

Another finding of the study is that at the individual level excellence was highly related to motivation. It is the most frequently mentioned element by experts, which is highlighted in the context of an excellent teacher and excellent institution. Moreover, lack of motivation is stated to be a barrier when reaching excellence in teaching. Concerning the teacher’s identity, the study experts frequently mentioned that command of subject knowledge is an indication of individual excellence similar to what Bain (Citation2004) found out in his study. Another aspect that the experts mentioned about teachers' identity was that excellent teachers should be open to communications with fellow teachers and students, must constantly improve their skills and make it possible for students to share, develop and improve their ideas (Bain, Citation2004).

Yet at the institutional level, the study revealed the importance of a reward system for achieving excellence in teaching. Experts highlighted the importance of rewarding excellence in the form of providing opportunities, financial rewards, or recognition. Creation of an evaluation system or mechanism with clearly defined indicators that will lead to a meaningful reward (Gunn & Fisk, Citation2013). All experts in the study were in favour of rewarding with a thorough belief that rewarding will lead to the desired performance. None of the experts mentioned undesired outcomes of the reward system that might create extra tensions among colleagues and bring more stress, emotional outbreaks and job burnouts (Stoeber & Rennert Citation2008; Gibbs, Citation2012). Nevertheless, because the majority of the studies have been conducted in developed countries, there is a major difference in the conceptualisation of the concept. When in western countries the research is talking about shortcomings of established Rewarding Schemes for Excellence (the UK Teaching Excellence Framework is an example), here the definition of ‘excellence in teaching’ and its ways of promotion are yet to be developed.

Following the conceptual framework () and binding it with the research findings, it is concluded that there is a possibility of achieving excellence in teaching at individual and institutional levels and some implications are offered by the authors.

Under the ‘Promoting Excellence’ scheme as part of this study, a predetermined number of training and development programmes for teachers is necessary, as Elton (Citation1998) argued unless the higher education institution has a specific professional development programme, excellence in teaching will be hard to achieve. These programmes should include topics covering a wide range of areas including content and pedagogical knowledge.

At the institutional level, it is worth introducing a series of changes. First, ‘excellence in teaching’, if it is at the core of the institutional aspirations, its incorporation into the institutional strategy with all the standards, requirements, expectations and rewards would yield greater results. It might also help to communicate it to teaching staff so that everyone is familiar with and willing to join the process to contribute to the development of a quality culture.

Second, along with all the requirements, the institution must materialise intention to make it possible by creating favourable conditions for staff's professional development. Given that there are no clear guidelines or framework for excellence in teaching, teachers are leading the way by independently taking care of their professional development, motivation and aspirations.

Third, education providers are carrying greater responsibility to make excellence in teaching possible (Brockerhoff et al., Citation2014). Excellence in teaching is viable to achieve once the actors are active participants and fulfill their responsibilities. Higher education institutions are responsible for creating an environment conducive to teaching and learning and providing possibilities for students and teachers to be better learners and teachers.

Further study is needed to shed light on a conceptualisation of excellence in teaching from student perspectives, through a posthuman lens which would make the suggested models much more inclusive (Little et al., Citation2007; Gravett & Kinchin, Citation2020). In a significant addition to the various perspectives offered above, looking at the ‘synergy between teaching, research and service’ would add to how excellence in teaching is conceptualised by academics (Zou et al., Citation2020). Yet another study on excellence in teaching would provide a comprehensive overview of how excellence in teaching is implemented at the national and institutional level in contexts similar to Azerbaijan. The concept’s wider dissemination remains crucial for system-wide changes. Developing a framework for excellence in teaching requires political and policy level conditions along with a clear content and measurement mechanism to be created to implement it at the institutional level (Gunn, Citation2018). Here, the higher education leaders need to consider the cultural and socio-political context of Azerbaijan. Excellence in teaching is a new notion in the Azerbaijani higher education context and the findings in this study should become a blueprint for leaders of higher education institutions willing to achieve excellence. This study will stimulate the other Azerbaijani scholars to explore excellence in teaching, which will create a fertile ground for the emergence of numerous other scholarly works in this area. Moreover, the views expressed in this study will be a starting point for how the academic staff perceives and promote excellence in teaching in Azerbaijan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Table 1. Description of participants

References

- Astin, A.W., 1990, Assessment as a Tool for Institutional Renewal and Reform (Washington, DC, AAHE).

- Bahia, S., Freire, I.P., Estrela, M.T., Amaral, A. & Espírito Santo, J.A., 2017, ‘The Bologna process and the search for excellence: Between rhetoric and reality, the emotional reactions of teachers’, Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), pp. 467–82.

- Bain, K., 2004, What the Best College Teachers Do (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

- Ball, C., 1985, ‘What the hell is quality’, in Ball, C.J.E. (Ed.), 1985, Fitness For Purpose: Essays in higher education, pp. 96–102 (Gildford, SRHE & NFER, Nelson).

- Bartram, B., Hathaway, T. & Rao, N., 2019, ‘Teaching excellence in higher education: a comparative study of English and Australian academics’ perspectives’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(9), pp. 1284–98.

- Behari-Leak, K. & McKenna, S., 2017, ‘Generic gold standard or contextualised public good? Teaching excellence awards in post-colonial South Africa’, Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), pp. 408–22.

- Brockerhoff, L., Huisman, J. & Laufer, M., 2015. Quality in Higher Education: A literature review (Ghent, Centre for Higher Education Governance).

- Brockerhoff, L., Stensaker, B. & Huisman, J., 2014, ‘Prescriptions and perceptions of teaching excellence: a study of the national ‘Wettbewerb Exzellente Lehre’ initiative in Germany’, Quality in Higher Education, 20(3), pp. 235–54.

- Brusoni, M., Damian, R., Sauri, J.G., Jackson, S., Kömürcügil, H., Malmedy, M., Matveeva, O., Motova, G., Pisarz, S., Pol, P., Rostlund, A., Soboleva, E., Tavares, O. & Zobel, L., 2014, The Concept of Excellence in Higher Education, European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, Occasional Paper, 20, pp. 1–44. Available at http://www.enqa.eu/index.php/publications/ (accessed 18 February 2022).

- Dicker, R., Garcia, M., Kelly, A. & Mulrooney, H., 2019, ‘What does quality in higher education mean? Perceptions of staff, students and employers’, Studies in Higher Education, 44(8), pp. 1425–41.

- Elton, L., 1998, ‘Dimensions of excellence in university teaching’, The International Journal for Academic Development, 3(1), pp. 3–11.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S.A. & Alkassim, R.S., 2016, ‘Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling’, American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), pp. 1–4.

- Gibbs, G., 2012, Implications of Dimensions of Quality in a Market Environment (York, Higher Education Academy).

- Glasner, A., 2003, ‘Can all teachers aspire to excellence’, Exchange, 5, p. 11.

- Gourlay, L. & Stevenson, J., 2017, ‘Teaching excellence in higher education: critical perspectives’, Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), pp. 391–95.

- Gravett, K. & Kinchin, I., 2020, ‘Revisiting ‘A “teaching excellence” for the times we live in’: posthuman possibilities’, Teaching in Higher Education, 25(8), pp. 1028–34.

- Gunn, A., 2018, ‘The UK Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF): the development of a new transparency tool’, in Curaj, A., Deca, L. & Pricopie, R. (Eds), 2018, European Higher Education Area: The impact of past and future policies (Cham, Springer).

- Gunn, V. & Fisk, A., 2013, Considering Teaching Excellence in Higher Education: 2007–2013: A literature review since the CHERI report 2007 (York, Higher Education Academy).

- Harvey, L., 2003, ‘Student feedback’, Quality in Higher Education, 9(1), pp. 3–20.

- Harvey, L. & Green, D., 1993, ‘Defining quality’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(1), pp. 9–34.

- Isakhanli, H. & Pashayeva, A., 2018, ‘Higher education transformation, institutional diversity and typology of higher education institutions in Azerbaijan’, in Huisman, J., Smolentseva, A. & Froumin, I. (Eds.), 2018, 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries: Reform and continuity, pp. 97–121 (London, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Kreber, C., 2002, ‘Teaching excellence, teaching expertise, and the scholarship of teaching’, Innovative Higher Education, 27(1), pp. 5–23.

- Little, B., Locke, W., Parker, J. & Richardson, J., 2007, Excellence in Teaching and Learning: A review of the literature for the Higher Education Academy (York, Higher Education Academy).

- Macfarlane, B. 2007, ‘Beyond performance in teaching excellence’, in Skelton, A. (Ed.), 2007, International Perspectives on Teaching Excellence in Higher Education. Improving knowledge and practice, pp. 48–59 (Abingdon, Routledge).

- Madriaga, M. & Morley, K., 2016, ‘Awarding teaching excellence: ‘what is it supposed to achieve?’ Teacher perceptions of student-led awards’, Teaching in Higher Education, 21(2), pp. 166–74.

- Mammadova, L. & Valiyev, A., 2020, ‘Azerbaijan and European Higher Education Area: students’ involvement in Bologna reforms’, Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 5(4), pp. 1083–21.

- Matheson, R., 2019. ‘In pursuit of teaching excellence: outward and visible signs of inward and invisible grace’, Teaching in Higher Education, 25(8), pp. 1–17.

- McNaught, C. & Anwyl, I., 1992, ‘Awards for teaching excellence at Australian universities’, Higher Education Review, 25(1), pp. 31–44.

- Moreno, V.G. & Patrinos, H.A., 2019, ‘Returns to education in Azerbaijan: some new estimates’, Problems of Economic Transition, 61(6), pp. 411–25.

- Oravec, J.A., 2017, ‘The manipulation of scholarly rating and measurement systems: constructing excellence in an era of academic stardom’, Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), pp. 423–36.

- Ramsden, P. & Moses, I., 1992, ‘Associations between research and teaching in Australian higher education’, Higher Education, 23(3), pp. 273–95.

- Readings, B., 1996, The University in Ruins (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press).

- Saunders, D.B. & Blanco Ramírez, G., 2017, ‘Against ‘teaching excellence’: ideology, commodification, and enabling the neoliberalization of postsecondary education’, Teaching in Higher Education, 22 (4), pp. 396–407.

- Silova, I., 2009, ‘The crisis of the post-Soviet teaching profession in the Caucasus and Central Asia’ Research in Comparative and International Education, 4(4), pp. 366–83.

- Skelton, A., 2005, Understanding Teaching Excellence in Higher Education, Towards a Critical Approach, first edition (London, Routledge).

- Skelton, A., 2007, International Perspectives on Teaching Excellence in Higher Education (Abingdon, Routledge).

- Stoeber, J. & Rennert, D., 2008, ‘Perfectionism in school teachers: relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout’, Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21(1), pp. 37–53.

- Strathern, M. (Ed.), 2000, Audit Cultures: Anthropological studies in accountability, ethics, and the academy (London, Routledge).

- Tomlinson, M., Enders, J. & Naidoo, R., 2020, ‘The teaching excellence framework: symbolic violence and the measured market in higher education’, Critical Studies in Education, 61(5), pp. 627–42.

- Warren, R. & Plumb, E., 1999, ‘Survey of distinguished teacher award schemes in higher education’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 23(2), pp. 245–55.

- Wood, M. & Su, F., 2017, ‘What makes an excellent lecturer? Academics’ perspectives on the discourse of ‘teaching excellence in higher education’, Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), pp. 451–66.

- Zou, T.X., Harfitt, G., Carless, D. & Chiu, C.S., 2020, ‘Conceptions of excellent teaching: a phenomenographic study of winners of awards for teaching excellence’, Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), pp. 1–16.