Abstract

This article examines how university students assess the coordination of the courses their programmes contain and how course coordination affects how content they are with their studies. The study is based on survey data from more than 5700 students, collected through Lund University’s Student Barometer. The survey examines the students’ views on course coordination based on content, workload, administrative procedures and whether or not teachers of different courses provide coherent information. The analysis shows that the coordination of courses has a significant impact on how students experience their studies. The better the course coordination, the more satisfaction students will get from their studies; and the correlation remains stable when several other factors of importance for student satisfaction are included in the analysis. The conclusion of the study is thus that course coordination clearly contributes to explaining variations in students’ appreciation of their university studies.

Introduction

In 2017–2018, the Student Barometer survey was conducted at Lund University, a Swedish full-scale university with nine faculties and about 40,000 full-time students. The Student Barometer is a university-wide survey that examines students’ experiences of their studies from various perspectives. In a broader sense, the Student Barometer can be described as a form of procedural data collection that universities have carried out as part of their quality work for several decades (Harvey, Citation2003, Citation2011; Alderman et al., Citation2012).

The survey was answered by more than 5700 students and thus generated extensive data that highlight students’ views of their education from a range of different perspectives. All aspects were presented in a report that can be described as a compilation of a large number of bivariate analyses (Holmström, Citation2018). While summary statistics of this kind provide a general overview of how the respondents relate to the questions asked in the survey, a comprehensive dataset such as this also provides many interesting opportunities for in-depth studies and analyses. This has been an important starting point for work on this article.

One of the results that stood out was that the level of coordination between different courses of a programme seemed to co-vary with how satisfied the students were with their studies. The survey asked all programme students what they thought about the coordination of courses in their programmes: specifically, content, administration, workload and whether or not teachers of different courses provided coherent information. The data showed that students who emphasised that the courses in their programmes were well coordinated also reported a higher degree of satisfaction with their studies than other students. Course coordination, which is that courses are linked to each other in such a way that they provide students with an overall sense of context and coherence, thus appears to be a quality aspect of crucial importance in higher education. By this logic, teacher collaboration across course boundaries becomes essential and course coordinators (the teachers in charge of the various courses) and the programme director (the teacher in charge of the programme as a whole) become key actors. With this in mind, the purpose of this article is to deepen the understanding of how students experience course coordination and what impact course coordination has on how satisfied students are with their studies. The article attempts to answer the questions by both linking to the research literature in the field and engaging in more advanced statistical analyses. The article can thus be read also as an example of how results from student surveys, carried out within university quality work, can be developed further (Alderman et al., Citation2012).

The study’s empirical analyses are based on two overarching themes. First, the article explores how students experience various aspects of coordination (content, administrative procedures, workload and teacher coherence) and investigates which aspects of course coordination are generally perceived as well-functioning and which are not. Second, it focuses on the impact of course coordination on students’ experiences of their university studies and explores the importance of course coordination from a student perspective. Is it possible to determine the importance of course coordination in an empirical sense?

The article focuses on substantive, as well as formal and administrative, aspects of course coordination. This broader approach to course coordination is based on the premise that students in Swedish universities often change course coordinators several times each semester, and that this, due to the shifting priorities and preferences of different course coordinators and teachers, can lead to recurrent changes in the practical and administrative routines and instructions that frame the studies. From a coordination perspective, it may therefore be important to consider not only course content but also form. For reference, one might imagine a situation in working life where employees had to change managers several times every six months and consider how important it would be, in such a situation, that practical procedures, administrative routines and performance requirements did not change with every change of manager.

Knowledge development, study results and experience of stress prior to university studies are all examples of factors of possible relevance when studying how quality of course coordination affects student appraisal of university programmes. This article will focus on a more general level, by examining how course coordination influences students’ overall satisfaction with their studies. There is, however, much to suggest that overall satisfaction is of importance to students’ general well-being, knowledge progression and study results.

University programmes differ substantially from one another in, for example, programme objectives, duration and structure. This means that different programmes face different kinds of challenges when it comes to coordination. In light of this, it is important to note that the focus of this study is not on the analysis of different programme conditions or on comparing different programmes to each other. The main focus here is on how students, on a programme-wide level, experience course coordination and how this affects their overall level of satisfaction with their university studies.

Different perspectives on the coordination of courses within a programme

An important starting point for this study is that all university programmes consist of a set of separate courses, each with their own content, design and intended learning outcomes. The fact that courses are regarded as the main teaching unit means that the programmes can be seen as a series of modules rather than as a ‘natural whole’. This puts course coordination at the centre of overall planning and implementation of university programmes, of student learning and of teacher cooperation (Hay & Strydom, Citation2000). Consequently, the importance of course coordination is also emphasised in various ways in the literature dealing with quality in higher education.

The idea of constructive alignment at programme level is based on the premise that university programmes consist of a series of separate courses. Against this backdrop, the overall programme objectives must be implemented in the intended learning outcomes for the various courses. This is important both to avoid programme objectives falling between the cracks and to avoid that certain teaching practices are repeated in an unreflective way (Biggs & Tang, Citation2011). From a more general perspective, the concepts of horizontal and vertical integration (mostly discussed in the context of medical education) are a reminder of the importance of cross-course integration, both with regard to the various theoretical courses within a programme and with regard to the theoretical and practical parts of a programme (Hammar et al., Citation1998). In course coordination practice, curriculum mapping is a method commonly used (Arafeh, Citation2014; Luckay, Citation2018; Herrmann & Leggett, Citation2019). A curriculum map can essentially be described as an array of rows and columns: the columns representing the programme objectives and the rows representing the courses offered within the programme. Such a map can be used to specify how different learning outcomes are handled in the different courses of a programme (Herrmann & Leggett, Citation2019).

Ensuring that a programme's various courses are linked to each other in a purposeful way is considered central to student knowledge development and progression. Since several different courses can cover the same programme objectives, it is important that courses are coordinated in such a way that different aspects of the objectives are covered and discussed in ever greater depth throughout the programme (Biggs & Tang, Citation2011). Furthermore, knowledge formation requires that students are provided with continuity and a holistic view and that the different parts of a course and programme are linked and relate to each other in such a way that they make up a meaningful whole (Hammar et al., Citation1998; Harden & Stamper, Citation1999; Toohey, Citation1999; Scherp & Uhnoo, Citation2018; Woodward, Citation2019). Student progression can also be an important aspect to take into account in curriculum mapping; and so-called backward mapping is an example of a mapping method focused on expected student outcomes (knowledge and skills) on completion of a programme (Herrmann & Leggett, Citation2019; Luckay, Citation2018). Similarly, student learning throughout the various courses of a programme can be planned and described in specific matrices that also display progression (Säfström, Citation2017; Andersson, Citation2018; Annerberg & Fändrik, Citation2018).

Successful course coordination, however, requires that teachers collaborate across course boundaries, discuss and take an interest in the programme as a whole, rather than regard it as a set of isolated subject modules. Programme teachers acting as a team when it comes to course coordination is important not only when establishing new programmes (Gerbic & Kranenburg, Citation2003) and in relation to the work carried out by the programme director (Weenink et al., Citation2022) but also in relation to the overall quality assurance of a programme (James & McInnis, Citation1997) and consequently in relation to programme evaluations (Hay & Strydom, Citation2000). Cross-course collaboration may also be discussed from the perspective of what Weaver et al. (Citation2009) refer to as collective rather than individual sense-making. From this perspective, teachers should aim to ensure that their sense-making of the programme is not limited to their own teaching and their own perspectives but also takes other teachers’ perspectives and teaching efforts into account. Such a notion of shared responsibility and collective ownership among programme teachers and course coordinators is also one of the crucial factors when it comes to enhancing a quality culture in higher education (Legemaate et al., Citation2022).

Teacher collaboration cannot, however, be taken for granted, and taking a holistic approach to the programme can be a challenging task for the programme director (Weenink et al., Citation2022). In academia, there is a built-in and ever-present tension between academic collegiality and academic autonomy that tends to complicate rather than facilitate collaboration (Gerbic & Kranenburg, Citation2003). In addition, the workload among university teachers is often high and finding the time to reflect on your own teaching in relation to the programme as a whole can be hard (Melin et al., Citation2014). As Roxå and Mårtensson’s research on academic microcultures further shows, university education is shaped and reshaped through social processes in a collegiate context and different contexts set different priorities (Mårtensson et al., Citation2012; Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2014, Citation2016; Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2015). How course coordination is developed or neglected can therefore be seen as a result of the interaction between teachers and other staff working with the programme in question.

Empirical studies of student perspectives on course coordination

Empirical data on how students experience their university studies are collected continuously at different levels (faculty, institution, programme, module) and using different methods (focus group conversations and ongoing informal conversations between student group and programme teachers) (Harvey, Citation2011). At many universities, course or module evaluations are the most common form of the follow-up survey. Those interested in data on student views of whole programmes and course coordination within programmes, however, will be looking at programme evaluations rather than course evaluations. In a Swedish university context, there are several examples of programme evaluations that touch on the subject of course coordination. These highlight both substantive and more formal aspects of course coordination. The results from a nursing programme evaluation, for example, emphasised how the level of requirements varied between different courses in the programme, the lack of consensus among teachers about central and recurring elements of knowledge, as well as how long it took for students to form a holistic view of the programme (Sonesson et al., Citation2015). In an evaluation of a teacher education programme, students reported wanting one of the most central elements of knowledge (pedagogical leadership) to be a recurring element in the programme, taught in greater depth the further they advanced in their studies (Faculty of Education and Society, Malmö University, Citation2016). The results from an evaluation of a medical education programme emphasised the importance of a holistic approach and integration not only within courses but also between courses. In an analysis of the results, Bonnevier and Henriksson (Citation2016) however concluded that the evaluation gave no clear indications of how integration should be achieved. In addition to programme evaluations, course coordination and issues concerning whole programmes can also be highlighted in data collected through the type of surveys that many universities carry out routinely at either university or faculty level, and of which the Student Barometer is an example (Harvey, Citation2003, Citation2011; Alderman et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, issues concerning course coordination can be addressed in different ways in national evaluations of higher education carried out within the framework or on behalf of higher education authorities (QILT, Citation2020; NOKUT, Citation2021).

While there is empirical data that focuses on student perspectives on course coordination and coordination of whole programmes, the issue has no given place in routine student follow-ups. Nor does course coordination and its significance for students seem to be a prioritised issue in more research-oriented empirical studies. In studies with a similar but significantly broader focus, several factors of importance for student satisfaction and well-being in general can be identified (Wiers-Jenssen et al., Citation2002; Zineldin et al., Citation2011). In addition, several studies serve as a reminder of how quality in higher education and student satisfaction is a complex issue comprising many interacting factors (James & McInnis, Citation1997; Wiers-Jenssen et al., Citation2002; Urwin et al., Citation2010; Hamshire et al., Citation2017). Well-defined empirical research studies that take a specific interest in student views on the quality of course coordination within programmes, and how course coordination is related to the overall experience of university studies, are hard to find.

In summary, the literature in the field describes the importance of course coordination from several different perspectives but empirical studies that focus on course coordination significance from a student point of view seem to be largely absent. In the literature, the importance of treating programmes as coherent entities and linking courses to each other when planning is emphasised through concepts such as constructive alignment and curriculum mapping. In addition, course coordination is described as important for student learning and for student knowledge progression in particular. Furthermore, teachers of different courses collaborating to ensure the quality of the programme as a whole is described as a crucial quality factor in higher education. At the same time, the workload among teachers is often high and the coordination of courses is hardly a priority issue within all university programmes. Against this background, it would be of interest to find out more about the importance of course coordination. Do planning and teacher efforts really make a difference to the students taking the programme? Is the work that academic staff put into course coordination rewarded in that it generates more positive student experiences? It is questions such as these that the study can hopefully contribute to answering.

Materials and method

The empirical material of the study was collected through Lund University’s Student Barometer, a survey targeting a sample of the university’s students which was conducted around the turn of the year 2017–2018. In November 2017, a Swedish and an English version of the survey was sent by e-mail to 20121 students, of which 5715 (28%) answered (Holmström, Citation2018).

Questions about course coordination were only put to students studying in programmes, which made up the majority of respondents (4796 students). In order to ensure that the views collected were based on a reasonable amount of experience, answers from students in their first semester of the programmes were excluded. A total of 2391 respondents have valid values of all variables included in the analyses (). More than 200 university programmes at nine different faculties are represented in the Student Barometer.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

The survey includes a question battery that highlights programme students’ views on four different aspects of the coordination of courses in their programmes. The students were asked: How would you rate the coordination of courses in your programme with regard to the following?

The programme consists of courses which are linked to each other in a good/reasonable/logical way.

Requirements and workload are approximately the same in the different courses.

Administrative procedures are the same for the different courses.

The information provided by teaching staff on the different courses is consistent.

The respondents were asked to rate all four aspects of coordination on a four-point scale that included the options: ‘very bad’, ‘quite bad’, ‘quite good’ and ‘very good’. Respondents could also choose to answer ‘do not know/no experience’. The four aspects together form the independent variable of the study.

In the analyses of the significance of course coordination for students’ satisfaction with their studies, the question ‘How content are you with your studies at Lund University?’ is used to measure general and overall satisfaction. Students were asked to rate their satisfaction on a four-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘very much’ (4). The question about how content the students are is thus the study’s dependent variable.

The analysis both examines each aspect of course coordination separately, and summarises the values for the four aspects of course coordination in an index. The purpose of the index is to create a broader and more reliable measure that captures different aspects of the phenomenon being studied (Spector, Citation1992, pp. 1–6). The index ranges from 0 (the respondent rates all four aspects of coordination as ‘very bad’) to 12 (the respondent rates all four aspects of coordination as ‘very good’). The internal consistency, evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, was more than satisfactory with a value of 0.73 (Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011).

Results

The following account of the study’s results explores how the students rate each of the four different aspects of course coordination. The students’ assessments of the different aspects are then summarised in a summated coordination index. This is followed by an examination of how the students’ overall assessment of the course coordination relates to their level of satisfaction with their studies in a bivariate analysis. Finally, a logistic regression analysis examines the importance of course coordination for overall student satisfaction, taking into account other explanatory variables.

Students’ views on course coordination

The vast majority of students report that courses in their programmes are linked in quite a good way (53%) or in a very good way (35%) (). The students have greater doubts when it comes to administrative procedures, coherent information aspects of course coordination and the workload. One in three students (33%) is critical of the coordination of administrative procedures and almost as many (28%) do not find that the information teachers of different courses provide is coherent. Half of the students rate the coordination of requirement and workload levels between courses as quite bad (37%) or very bad (13%).

Table 2. How students’ views on the four aspects of course coordination are distributed (percent).

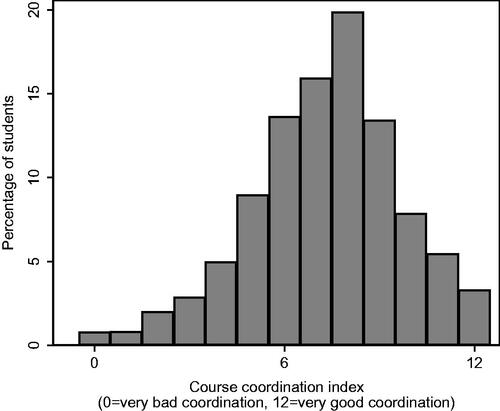

Summary of the four aspects of coordination generates an index of the students’ overall assessment of the course coordination. The index consists of 13 scale values where 6 is the middle value. A greater number of students can be found on the positive side (7–12) than on the negative side (0–5) of the middle value (). The average is 7.3 and the standard deviation is 2.4.

Figure 1. Summated index of students’ experiences of course coordination within their university programme (Percentage of students).

It is important to note that results are reported at an aggregate level and that results for different programmes may vary extensively. While in many programmes a majority of the students find their programme to be well-coordinated, the proportion of critical students is higher in others.

Importance of course coordination

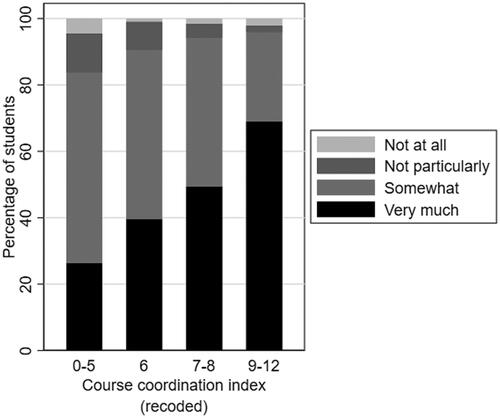

To enable analysis of how important course coordination is from a student perspective, the coordination index has been classified and related to how content students are with their studies. The classification is designed to reflect the variation in the students’ answers to a reasonable extent while ensuring that the number of observations in any given class is not too small. The class division is as follows: 0–5 (n=490), 6 (n=326), 7–8 (n=856) and 9–12 (n=719).

A clear pattern emerges from the analysis: the more content the students are with the coordination of courses in their programme, the more content they are with their studies (). In the group least satisfied with the course coordination in their programme (index value 0–5), only about a quarter (26%) of the students report that they are ‘very much’ content with their studies. The percentage of students who report the highest level of satisfaction with their studies then gradually increases as the course coordination gets better. In the group of students with index values 7–8, that is, students who have quite a positive experience of the course coordination in their programme, the proportion of students who are ‘very much’ content with their studies has almost doubled (49%) and in the group most satisfied with the course coordination, almost seven out of ten (69%) are also very satisfied with their studies. The relationship persists even if the coordination index is classified differently.

Figure 2. How content students are with their studies by how students rate the coordination of courses in their programmes (Percentage of students).

It should be noted that each of the four aspects of course coordination included in the index has been examined in relation to how content students are with their studies. Regardless of which aspect was examined, the same pattern as that in was visible in the analysis.

Multivariate results

The bivariate analysis points to a clear correlation between how well courses are coordinated and how satisfied students are with their studies. At the same time, there are of course factors and circumstances other than course coordination that affect how students experience their studies. A more precise examination of the impact of course coordination thus requires an in-depth multivariate analysis that takes into account other factors that affect student satisfaction. Does the correlation between course coordination and student satisfaction remain unchanged when results are controlled for other factors that may affect students’ experiences of their studies? Could it be that other factors are of such importance for students’ satisfaction that the quality of course coordination is of no significance if these factors are present?

The method chosen for the multivariate analysis is binary logistic regression analysis (Long & Freese, Citation2014). The analysis examines the relationship between how students rate the quality of course coordination and how content they are with their studies. The dependent variable is dichotomised so that one category consists of those students who are very much content with their studies, while the other category consists of all other students, that is, those who have responded somewhat, not particularly or not at all. To enable examination of the relationship, two logistic regression models have been estimated (). Model 1 is a bivariate regression where course coordination is the only independent variable. The multivariate analysis in model 2 examines whether the importance of course coordination remains when several other factors that may have an impact on how satisfied students are with their studies are taken into account. Examples of factors included in the analysis are background variables such as faculty, gender and parents’ level of education; but also factors such as students’ academic success and general well-being and teaching situation variables such as whether the students find the teaching stimulating and how they rate their lecturers from a pedagogical perspective. Average marginal effects are reported in order to facilitate the interpretation of the results of the logistic regression analysis (Long & Freese, Citation2014, pp. 162–63, 242–44; Williams, Citation2012, pp. 324–26).

Table 3. Predicted probability of being ‘very much’ content with studies.

As expected, the analysis shows that there are many different factors that influence how satisfied students are with their studies. From , it can be deduced, for example, that the probability of a student being ‘very much’ content with their studies is 0.30 higher if the student has responded ‘somewhat agree’ to the statement that ‘teaching is stimulating’, than if the student is in the reference category ‘strongly disagree’. The corresponding change in probability if the student responds ‘strongly agree’ amounts to 0.53. There are other factors that impact on student satisfaction. Completing the different courses of the programme within the set time is important. Likewise, students who enjoy better general well-being tend to be more content with their studies than other students.

However, the most significant result that arises from the question posed in this article is that the effect of course coordination also appears in model 2 and is highly statistically significant (). The importance of course coordination thus remains when results are controlled for several other factors of importance for students’ satisfaction with their studies.

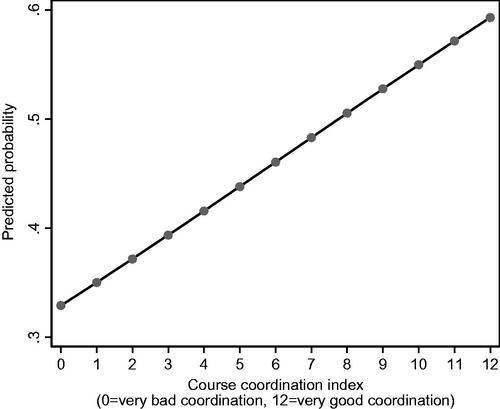

To further illustrate the results of the regression analysis (model 2), the predicted relationship between different values of the coordination index and the probability of students being ‘very much’ content with their studies has been plotted (Long & Freese, Citation2014). A clear pattern emerges from the graph: the better the course coordination is perceived to be, the higher the predicted probability that the students will be ‘very much’ content with their studies ().

Figure 3. Predicted probability of being ‘very much’ content with studies by how course coordination is rated.

It is quite possible for students to consider the course coordination in their programmes to be ‘bad’ and still be content with their studies. A student who is very dissatisfied with how the courses in the programme are coordinated (value 0 on the index) has a predicted probability of 0.33 of being ‘very much’ satisfied with their studies. However, as the analysis shows, the likelihood of students being ‘very much’ content with their studies gradually increases with an increasingly positive experience of the coordination of courses within their programme. Students who have a fairly positive experience of course coordination (value 6 on the index) have a predicted probability of 0.46 of being ‘very much’ content with their studies. For students who consider course coordination to be ‘very good’ (value 12 on the index), the predicted probability of being ‘very much’ content with studies is almost doubled to 0.59 ().

Conclusion

This study presents empirical evidence of course coordination having an impact on how satisfied and content students are with their studies. The better the students consider the coordination of courses in their programmes to be, the more content they are with their studies. This finding holds even when results are controlled for several other factors of importance for students’ satisfaction. The results are in line with and reinforced by research literature that in various ways underlines the importance of coordinating the courses in university programmes and of teachers collaborating across course boundaries. Drawing on concepts such as constructive alignment and curriculum mapping, the literature review underscores the importance of planning the coordination of university programme courses. Furthermore, the literature highlights the importance of course coordination for student learning, especially when it comes to student knowledge progression and students’ chances of acquiring a holistic understanding. This also draws attention to the importance of teachers collaborating across course boundaries.

Based on a broad view of course coordination, the analyses indicate that both substantive and formal aspects of course coordination have an impact on student satisfaction. This is evident when the overall importance of the various aspects is examined in a summated coordination index but also when each aspect is examined separately. When each aspect is isolated, it becomes clear that students are generally of the opinion that there is potential for improving the coordination of formal aspects such as administrative routines, workload and information between different courses. This is not to say that every course within a programme must be standardised and organised in exactly the same way. However, it raises several important questions. Which formal and administrative elements of university programmes and university teaching should be coordinated in such a way as to ensure continuity throughout the programme? Which student requirements should be recurring and which can vary from one course to another? Within which areas is it particularly important for teachers of different courses to provide coherent information?

In the operational efforts to coordinate courses, it is of course important to remember that each programme has its own specific conditions, for example when it comes to duration, complexity and objectives, and that challenges, difficulties and needs will therefore vary from one programme to another. Nevertheless, course coordination, with respect to both course content and course form, unequivocally appears to be of great importance to how students, regardless of programme, experience their studies. This does not mean that course coordination can be handled instrumentally and isolated from quality work on the programme as a whole. It should rather be regarded as an integral part of quality culture in higher education. Well-functioning course coordination is thus closely linked to a sense of shared responsibility for the programme as a whole among teachers. When such a notion of shared responsibility exists, course coordination is likely to work. Conversely, a lack of teacher communication and collaboration across course boundaries can lead to confusing divergences in content and form between the different courses in a programme. How well course coordination works is in turn of great importance to the students. This study clearly shows that well-coordinated courses have a positive impact on how students experience their studies, while the opposite is true of ill-coordinated courses.

Acknowledgements

The 2017 Lund University Student Barometer was carried out by the Education Strategy Support (formerly Quality and Evaluation) at Lund University. We would like to thank all our former colleagues at the office for cooperation and support during the planning and implementation of the barometer. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alderman, L., Towers, A.S. & Bannah, S., 2012, ‘Student feedback systems in higher education: a focused literature review and environmental scan’, Quality in Higher Education, 18(3), pp. 261–80.

- Andersson, P., 2018, ‘Måluppfyllelse, progression och kvalitetsarbete’, paper presented at LTHs 10:e Pedagogiska Inspirationskonferens, Lund, Sweden, 6 December.

- Annerberg, A. & Fändrik, A.K., 2018, ‘Developing a scientific foundation in vocational teacher education: experiences from a Swedish project’, Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 8(3), pp. 124–40.

- Arafeh, S., 2014, ‘Curriculum mapping in higher education: a case study and proposed content scope and sequence mapping tool’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(5), pp. 585–611.

- Biggs, J. & Tang, C., 2011, Teaching for Quality Learning at University (Maidenhead, Open University Press).

- Bonnevier, A. & Henriksson, P., 2016, Kursutvärdering läkarprogrammet. Sammanfattning av läkarprogrammets kursvärderingar, kursutvärderingar och samtal med kursansvariga vt 2015. Enheten för utvärdering (Stockholm, Karolinska institutet).

- Faculty of Education and Society, Malmö University, 2016, Samtal med studenter i grundlärarutbildningen med inriktning mot arbete i förskoleklass och årskurserna 1–3 samt mot årskurserna 4–6.

- Gerbic, P. & Kranenburg, I., 2003, ‘The impact of external approval processes on programme development’, Quality in Higher Education, 9(2), pp. 169–77.

- Hammar, M., Brynhildsen, J., Fallsberg, M. & Rundqvist, I., 1998, ‘Integrera mera! Goda erfarenheter av horisontell och vertikal integration vid läkarutbildningen i Linköping’, Läkartidningen, 95(7), pp. 662–64.

- Hamshire, C., Forsyth, R., Bell, A., Benton, M., Kelly-Laubscher, R., Paxton, M. & Wolfgramm-Foliaki, E., 2017, ‘The potential of student narratives to enhance quality in higher education’, Quality in Higher Education, 23(1), pp. 50–64.

- Harden, M.R. & Stamper, N., 1999, ‘What is a spiral curriculum?’, Medical Teacher, 21(2), pp. 141–43.

- Harvey, L., 2003, ‘Student feedback’, Quality in Higher Education, 9(1), pp. 3–20.

- Harvey, L., 2011, ‘The nexus of feedback and improvement’, in Nair, C.S. & Mertova, P. (Eds.), 2011, Student Feedback: The cornerstone to an effective quality assurance system in higher education, pp. 3–26 (Oxford, Chandos).

- Hay, D. & Strydom, K., 2000, ‘Quality assessment considerations in programme policy formulation and implementation’, Quality in Higher Education, 6(3), pp. 209–18.

- Herrmann, T. & Leggett, T., 2019, ‘Curriculum mapping: aligning content and design’, Radiologic Technology, 90(5), pp. 530–33.

- Holmström, O., 2018, Studentbarometern 2017 (Lund University, Quality and Evaluation) (report).

- James, R. & McInnis, C., 1997, ‘Coursework masters degrees and quality assurance: implicit and explicit factors at programme level’, Quality in Higher Education, 3(2), pp. 101–12.

- Legemaate, M., Grol, R., Huisman, J., Oolbekkink-Marchand, M. & Nieuwenhuis, L., 2022, ‘Enhancing a quality culture in higher education from a socio-technical systems design perspective’, Quality in Higher Education, 28(3), pp. 345–59.

- Long, J.S. & Freese, J., 2014, Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, third edition (College Station, TX, Stata Press).

- Luckay, M.B., 2018, ‘The re-design of a fourth year Bachelor of Education programme using the constructive alignment approach’, Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 6(1), pp. 143–67.

- Melin, M., Astvik, W. & Bernhard-Oettel, C., 2014, ‘New work demands in higher education. A study of the relationship between excessive workload, coping strategies and subsequent health among academic staff’, Quality in Higher Education, 20(3), pp. 290–308.

- Mårtensson, K. & Roxå, T., 2014, ‘Starka mikrokulturer – ett sociokulturellt perspektiv på högre utbildning’, in Johannsson, R. & Persson, A. (Eds.), 2014, Vetenskapliga perspektiv på lärande, undervisning och utbildning i olika institutionella sammanhang, pp. 381–90 (Lund, Department of Educational Sciences, Lund University).

- Mårtensson, K. & Roxå, T., 2016, ‘Peer engagement for teaching and learning: competence, autonomy, and social solidarity in academic microcultures’, Uniped, 39(2), pp. 131–43.

- Mårtensson, K., Roxå, T. & Stensaker, B., 2012, ‘From quality assurance to quality practices: an investigation of strong microcultures in teaching and learning’, Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), pp. 534–45.

- Nasjonalt organ for kvalitet i utdanningen (NOKUT), 2021, Studiebarometeret 2020 – Hovedtendenser (Norway, NOKUT). Available at https://www.nokut.no/ (accessed 7 February 2023).

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT), 2020, Student Experience Survey. Available at https://www.qilt.edu.au (accessed 7 February 2023).

- Roxå, T. & Mårtensson, K., 2015, ‘Microcultures and informal learning: a heuristic guiding analysis of conditions for informal learning in local higher education workplaces’, International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), pp. 193–205.

- Scherp, H.-Å. & Uhnoo, D., 2018, ‘Den vägledande pedagogiska helhetsidén’, in Scherp, H.-Å. & Uhnoo, D. (Eds.), 2018, Medskapande högskolepedagogik, pp. 133–52 (Lund, Studentlitteratur).

- Sonesson, A., Klingenfors, V., Thomé, B., Erici, S., Diehl, A. & Edgren, G., 2015, Utvärdering av sjuksköterskeprogrammet vid Lunds universitet: Höstterminen 2012 – vårterminen 2014. MedCUL:s rapportserie, vol. 26 (Lund, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University).

- Spector, P.E., 1992, Summated Rating Scale Construction. An introduction (Newbury Park, CA, Sage).

- Säfström, A.I., 2017, ‘Progression i högre utbildning’, Högre Utbildning, 7(1), pp. 56–75.

- Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R., 2011, ‘Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha’, International Journal of Medical Education, 2, pp. 53–55.

- Toohey, S., 1999, Designing Courses for Higher Education (Buckingham, Open University Press).

- Urwin, S., Stanley, R., Jones, M., Gallagher, A., Wainwright, P. & Perkins, A., 2010, ‘Understanding student nurse attrition: learning from the literature’, Nurse Education Today, 30(2), pp. 202–7.

- Weaver, L.D., Pifer, M.J. & Colbeck, C.L., 2009, ‘Janusian leadership: two profiles of power in a community of practice’, Innovative Higher Education, 34, pp. 307–20.

- Weenink, K., Aarts, N. & Jacobs, S., 2022, ‘“We’re stubborn enough to create our own world”: how programme directors frame higher education quality in interdependence’, Quality in Higher Education, 28(3), pp. 360–79.

- Wiers-Jenssen, J., Stensaker, B. & Jens B. Grøgaard J.B., 2002, ‘Student satisfaction: towards an empirical deconstruction of the concept’, Quality in Higher Education, 8(2), pp. 183–95.

- Williams, R., 2012, ‘Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects’, Stata Journal, 12(2), pp. 308–31.

- Woodward, R., 2019, ‘The spiral curriculum in higher education: analysis in pedagogic context and a business studies application’, e-Journal of Business Education & Scholarship of Teaching, 13(3), pp. 14–26.

- Zineldin, M., Akdag, H.C. & Vasicheva, V., 2011, ‘Assessing quality in higher education: new criteria for evaluating students’ satisfaction’, Quality in Higher Education, 17(2), pp. 231–43.