ABSTRACT

This study reports on how student teachers learn in the workplace. Data from 10 student teachers were collected by means of digital logs and in-depth interviews. By reconstructing data into stories and unravelling these stories, it became clear that the learning process of each student teacher was dominated by one specific theme, such as student-centred teaching or creating a positive learning climate. These themes could be typified as professional identity themes, because all appeared to be both personal and professional. Five student teachers experienced their workplace learning process as continuous: they integrated their teaching experiences relatively easily into their personal conceptual framework. The other five experienced their workplace learning process as discontinuous: they experienced tensions caused by frictions between personal and professional aspects of becoming a teacher. Both types of learning can stimulate and hinder student teachers’ professional development. The findings indicate that reconstructing data into stories and unravelling these stories is a useful technique for understanding student teacher workplace learning as a result of the interaction between personal and professional aspects of becoming a teacher.

Introduction

Learning to teach includes both personal and professional aspects. Who one is as a person strongly affects how one learns a profession (e.g. Kissling, Citation2014; Olsen, Citation2008). Research has shown how important the personal side of becoming a teacher is for student teachers. Many beginning teachers report having learnt the profession especially by exploring their personal visions and interests during teacher education (Brilhart, Citation2007). In the workplace (i.e. practice school/classroom), however, student teachers are strongly confronted with professional aspects, such as professional demands from the practice school. In addition, many teacher education programmes emphasise the importance of what student teachers should learn in terms of established professional standards (Pinnegar, Citation2005). From a professional identity perspective, becoming a teacher results from the interaction between personal beliefs, values, and norms on the one hand, and professional demands from teacher education institutes and schools, including broadly accepted values and standards about teaching, on the other hand (Beijaard, Meijer, & Verloop, Citation2004). It is a perspective that covers the complexity of the process of learning to teach and can be useful as a theoretical lens to study this process (Olsen, Citation2011). During the last two decades, much research has been done on the nature and characteristics (e.g. Rodgers & Scott, Citation2008) as well as the development of (student) teachers’ professional identity as the result of the interaction between personal and professional aspects of teaching (e.g. Flores & Day, Citation2006; Trent, Citation2011). Not much is known, however, how student teachers learn to teach as a result of this interaction.

This study aims at gaining a better understanding of how personal and professional aspects of learning to teach play a role in student teacher workplace learning. Since the rise of school-based teacher education programmes, workplace learning has been a substantial part of teacher education (e.g. Ball & Cohen, Citation1999; Hagger & McIntyre, Citation2006). As a result of this increasing focus on workplace learning, the complex character of (student) teacher learning becomes more apparent (Mutton, Burn, & Hagger, Citation2010). In the literature, increasingly attention is paid to the complex nature of (student) teacher learning (e.g. Opfer & Pedder, Citation2011; Webster-Wright, Citation2009). Research often focuses on one specific aspect, such as the influence of mentoring on learning, which does not do justice to the multidimensional, idiosyncratic, and context-specific nature of this type of learning (Mutton et al., Citation2010; Olsen, Citation2008). Although this research produces valuable information, it is incomplete. In reality, student teacher learning is a complex process of (a large number of) continuously interacting factors, such as knowledge, values, memories, beliefs, mentor feedback, and student behaviour in the classroom, including social, cultural, and organisational circumstances in which the student teacher is involved both as a person and as a professional (Beijaard et al., Citation2004; Olsen, Citation2008).

In our research, workplace learning is understood as a complex process in which student teachers both experience the practise of teaching and give meaning to their practical experiences (Leeferink, Koopman, Beijaard, & Ketelaar, Citation2015; Webster-Wright, Citation2009). This learning may be a continuous process in which student teachers integrate practical experiences and previous experiences relatively easily into their personal conceptual framework (Olsen, Citation2008). Workplace learning may also be a discontinuous process in which frictions arise between what student teachers personally desire and perceive as positive and the professional demands from the practice school; these frictions can lead to tensions in student teachers’ professional development that can both hinder or encourage their professional growth (e.g. Meijer, de Graaf, & Meirink, Citation2011; Pillen, Beijaard, & Den Brok, Citation2013). The central question in this study pertains to how student teacher workplace learning can be characterised as a result of the interaction between personal and professional aspects of becoming a teacher. Insight into what characterises this learning may have important implications for stimulating the professional development of student teachers and help teacher educators and mentors to understand and conceptualise the support student teachers need while learning in the workplace.

Theoretical framework

The personal and professional in becoming a teacher

Student teacher learning is strongly influenced by a variety of personal aspects, such as beliefs about teaching (Stenberg, Karlsson, Pitkaniemi, & Maaranen, Citation2014), values and convictions (McLean, Citation1999), and previous learning experiences (Meijer, Korthagen, & Vasalos, Citation2009). The process of becoming a teacher is also inextricably related to the personal lives of student teachers. Kissling (Citation2014), for example, found that student teachers learnt to teach not only during classroom moments but also in situations outside classrooms, across all times and places in their lives. Student teachers’ life experiences appeared to be strongly interwoven with their work as student teachers in the classroom. Olsen (Citation2008) came to a similar conclusion in his study on student teachers’ knowledge construction. He found, for example, that knowledge construction is a lifelong process of continuously interacting factors, such as childhood experiences, personal beliefs about teaching, and teacher education programmes.

A dominance of the personal in student teacher learning can lead to adherence to misguided practices by student teachers, such as uncritically reproducing self-experienced education as a student (e.g. Feiman-Nemser & Buchmann, Citation1985), but also to motivated and committed student teachers; many beginning teachers have reported on learning the teaching profession especially by exploring their personal visions and interests during teacher education, for example by working on a project based on a self-selected theme (Brilhart, Citation2007). However, according to Pinnegar (Citation2005), teacher educators often focus more on what student teachers should learn in terms of externally formulated professional standards, thus learning from ‘outside,’ than on what they personally desire and attach much value to, thus learning from ‘inside.’ It is generally known though that it is one’s identity—thus the perception of oneself as a teacher and the teacher one wishes to become—that fuels the behaviour and development of student teachers (Pinnegar, Citation2005; see also McLean, Citation1999). So, notwithstanding the relevance of professional standards for learning the teaching profession (Darling-Hammond, Citation2010), it is the personal in becoming a teacher (such as one’s own beliefs and previous learning experiences as a student) that seems to stimulate student teachers’ professional learning.

Continuous and discontinuous workplace learning

The interaction between personal and professional aspects of becoming a teacher may lead to various learning processes. Teacher learning is often characterised as a continuous process in which teachers integrate new professional experiences with existing experiences and knowledge into their personal conceptual framework (e.g. Beijaard et al., Citation2004; Webster-Wright, Citation2009). This also counts for student teacher learning. Olsen (Citation2008) concludes in his study on student teachers’ knowledge construction, for example, that a student teacher ‘draws on past experiences via personal constructs that organise understanding and assemble conceptions considered aligned with both past positionings and present context in order to navigate the future’ (p. 124). Student teacher learning is thus considered as a process in which concepts and experiences from different contexts and stages of life are continuously combined into (changing) personal knowledge structures.

This focus on continuous learning seems to suggest that student teacher learning is a steady process in which student teachers gradually develop as a teacher. Research on professional identity development of student teachers, however, shows both crises and tensions in student teacher learning (e.g. Alsup, Citation2006; Smagorinsky, Cook, Moore, Jackson, & Fry, Citation2004). From a study by Meijer et al. (Citation2011), it appears that many student teachers experience their professional development not as a steady process, but as a path with highs and lows that include transformative moments or periods. These transformative moments or periods are often accompanied by one or more crises caused by negative experiences of student teachers, such as unmotivated students, which may result in feelings of uncertainty or disillusionment. In many cases, crisis is followed by regained motivation for the teaching profession (Illeris, Citation2014). According to most of the student teachers in the study of Meijer et al. (Citation2011), this turning point is often the result of conversations with their mentors about their professional development.

Pillen et al. (Citation2013) found that frictions between personal desires and expectations and the professional demands from teacher education institutes and schools, can lead to (serious) tensions accompanied by (strong) feelings of frustration or anger. Student teachers who feel that their personal beliefs are under pressure and who are unable to deal with these tensions can stagnate in their learning or even quit teacher education (Alsup, Citation2006; Bronkhorst, Koster, Meijer, Woldman, & Vermunt, Citation2014). Based on studies like those mentioned above, it can be concluded that student teacher learning can also be a discontinuous process in which practical experiences conflict with personal desires and expectations.

This study takes a professional identity perspective as a lens to investigate the (dis)continuous character of student teacher workplace learning. The emphasis, therefore, will be on the form of workplace learning (continuous/discontinuous), but attention will also be paid to the content of this learning (student teachers’ focus during learning).

Method

A narrative approach was used in this study. In this approach, participants give meaning to their experiences by interpreting these experiences narratively, which means that they shape their professional understandings by stories of who they and others are. Stories are seen as portals through which experiences are interpreted and made personally meaningful (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006). According to Clandinin and Connelly (Citation2000), this process of meaning making through interpreting experiences narratively can be characterised as relational (experiences are both personal and social), temporal (experiences stem from other experiences and lead to new ones), and situational (experiences take place in situations). It might thus be assumed that the complexity of student teachers’ workplace learning is encapsulated in and can be understood by investigating student teachers’ stories (Goodson, Biesta, Tedder, & Adair, Citation2010; Polkinghorne, Citation1995). By examining student teachers’ stories about practical experiences, insight can be obtained into both the personal meaning of experiences for student teachers as well as the (dis)continuous character of learning (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000; Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, Citation1998).

According to Polkinghorne (Citation1995), a story is characterised by a plot. The plot is the narrative structure that connects events and activities in the data that contribute to a particular outcome (e.g. a learning experience) and shapes the context to understand the outcome. An example: ‘The king died. The prince cried.’ In isolation, these are two separated events, but by connecting them ‘a new level of relational significance appears’ (Polkinghorne, Citation1995, p. 7). This ‘relational significance’ is the result of the (narrative) meaning making operation of the plot: the prince’s crying appears as a response of his father’s dead. The story provides the context for understanding the crying (Polkinghorne, Citation1995).

In this study, data on student teacher workplace learning were collected and reconstructed into stories. Reconstructing data into stories is the process of emplotment. During this process, a plot is developed through which the events and activities in the data are linked together as contributors to a certain outcome and take on narrative meaning. By reconstructing data into stories, it became clear how events and activities in student teacher workplace learning were connected and how these aspects contributed to student teachers’ learning experiences; the relationships between the aspects came to the light in the stories (cf. Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000; Lieblich et al., Citation1998).

We based the reconstruction of these data into stories on the following two functions of a plot: (a) delimiting a temporal range which marks the beginning and end of the story, and (b) ordering events and activities within that range into a process culminating in a conclusion (Polkinghorne, Citation1995). A plot thus provides temporal structuring of a story and enables the selection of events and activities for their relevance in the story (Goodson et al., Citation2010). This selection of events and activities (narratively seen, the middle of the story) is only possible by taking into account the denouement of the story (Goodson et al., Citation2010). Narrative research especially aims the retrospective describing of events and activities; one can only really understand (causal linkages in) a story from the perspective of the end (Coulter & Smith, Citation2009). In this study, the active principles of this narrative structure (beginning, middle, end) were taken as starting point for reconstructing data on student teacher workplace learning into stories (see Appendix 1).

Participants and context

Ten student teachers from five teacher education institutes of universities of applied sciences in the Netherlands (bachelor degree/level) representing seven different disciplines participated in this study. Student teachers agreed to participate after the study was introduced and explained. To obtain a rich data set, participants who varied in gender, age, discipline, and year of study were selected (see ). All participants did their teaching practice in different schools for vocational education in the central and southern part of the Netherlands.

Table 1. General characteristics of the participants.

During their teaching practice periods, the student teachers were coached by a mentor from the practice school and visited once or twice in their practice school by a teacher educator from the teacher education institute. The student teachers also attended weekly meetings (ranging from 1 day to 4 days) at the teacher education institute, for example, for lectures, workshops, and intervision.

Data collection

During a period of two years of study, data were collected by means of digital logs and in-depth interviews. Combining the data collected with different instruments enables to develop a comprehensive view of a complex process like student teacher workplace learning (Meijer, Verloop, & Beijaard, Citation2002). The digital logs were used to collect stories about student teachers’ workplace learning experiences. The in-depth interviews were used to gain insight into the content (student teachers’ focus during learning) and form (continuous/discontinuous) of student teachers’ workplace learning. By using these two instruments, it was aimed to do justice to both the richness and uniqueness of the learning process of each student teacher (Lieblich et al., Citation1998).

Digital logs

During the research period, the student teachers wrote four to eight stories in their digital logs about how they learnt from their practical experiences. To help them considering different aspects that contributed to their learning experiences, they were asked to structure their stories around questions referring to the beginning, middle, and end of their learning process with regards to their experiences (see ).

Table 2. Questions to be answered about the reported learning experience.

During their teaching practice periods, the student teachers were contacted via email approximately once every 6 weeks and asked to describe a learning experience they had in the past 4 weeks. The email contained the questions to be answered about the learning experience (see ) and a deadline for sending in the report. When the researcher received a reported learning experience, a quick check was performed to see whether the story addressed all questions. Missing information was asked for, if necessary.

In-depth interviews

Each student teacher was interviewed four or five times about his or her workplace learning process: one biographical interview at the beginning of the research period, two or three learning process interviews during this period, and one story-line interview at the end. Six student teachers were interviewed five times; the other four student teachers were interviewed four times due to illness or lack of time. In total, 46 interviews were held. All interviews were audiotaped. The length of the interviews varied between 45 and 90 min.

To gain insight into the personal and professional backgrounds of the student teachers, one biographical interview was held with each student teacher (Kelchtermans, Citation1994). Student teachers were encouraged to articulate their personal and professional beliefs and life experiences on the basis of various themes, such as childhood, school career, and conceptions on teaching. Each theme was introduced with an open question, for example: ‘Can you tell something about the family in which you grew up?’; ‘How would you describe your school career?’; ‘What was important for you as a student?’; ‘Can you tell something about your teaching beliefs?’ During the interview follow-up questions were asked.

To gain understanding of how student teachers learnt from their practical experiences, two or three learning process interviews were held with each student teacher. The starting point for each interview was a story in the student teacher’s digital log that the student teacher had indicated as important. To refresh the student teacher’s memory, each student teacher was asked to read the story he or she had described in the digital log. The interviews were narrative in that the questions could differ per participant, but all were asked about the relational, temporal, and situational nature of their experiences, based on Clandinin and Connelly (Citation2000) as described before. Examples of questions are as follows: ‘In your digital log you have written that you learnt a lot from the conversation with your mentor. Can you tell something more about that?’ (relational); ‘You told me that you felt uncomfortable through the behaviour of a student. Can you describe what happened?’ (situational); ‘Last year you had a similar experience. What happened? What did you do? Do you do anything different now? If so, why? What has happened in the meantime?’ (temporal). When no new information was added to the participant’s story, the interview ended.

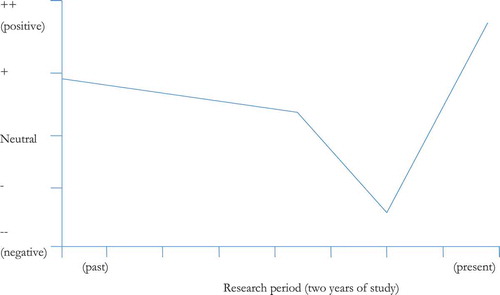

To gain insight into how student teachers perceived their own professional development, one story-line interview was held with each student teacher (Beijaard, van Driel, & Verloop, Citation1999). Student teachers were asked to look back on their professional development as the result of workplace learning during the research period. To this end, five topics were selected that the student teachers had indicated as important in their digital logs: (1) building professional self-image, (2) instructional behaviour, (3) classroom management, (4) student-centred teaching, and (5) focus on (outside) school context (i.e. activities outside the classroom, such as participating in meetings with colleagues or visiting internships of their students). The interview consisted of the following four steps. First, the topics were explained to the student teachers. Second, student teachers were asked how positive or negative they currently perceived themselves with regards to these topics. Third, for each topic, student teachers were asked to draw a line from the present to the past that represented their professional development on this topic (see for an example). Fourth, student teachers were asked to explain the possible highs and lows in the lines, and what relational, temporal, and situational experiences had contributed to these highs and lows (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000). With regards to the storyline in , for example, questions were asked such as: ‘What happened around the 18th month making you more positive about yourself as a student teacher?’ (situational) ‘You told me that you stimulate students to regulate their own learning. What did you do before? Why did you try something else? What has happened in the meantime?’ (temporal); ‘Students are positive about regulating their own learning. Can you tell something about that?’ (relational)

Figure 1. An example of a storyline ‘Building professional self-image.’ This storyline shows how the professional self-image of a student teacher changes during the research period: from quite positive at the beginning of this period to quite negative around the 18th month. From that moment, the student teacher’s professional self-image rapidly becomes more positive.

Data analysis

The data were analysed in two phases: (1) by reconstructing data into stories (narrative analysis), and (2) by unravelling these stories (holistic-content and holistic-form analysis). The aim of the first phase was to produce stories, based on all data. The focus was on constructing a narrative configuration of the data into a temporally organised whole. The aim of the second phase was to identify themes and patterns (continuous/discontinuous) in each student teacher’s story and compare themes and patterns across the stories.

Narrative analysis

In this first phase, one story was written for each student teacher about his or her workplace learning process during the research period. Each story was based on the data of the digital log and the in-depth interviews. A plot was developed that fit with the data and that was characterised by a structure that included a beginning, middle, and end (Cortazzi, Citation2014). The beginning consisted of a description of a goal or problem of the student teacher at the beginning of the internship (e.g. the question of how to create a positive learning climate for students), and the end contained a description of the student teacher’s comprehension concerning this goal or problem (e.g. the importance of giving positive feedback). The way of processing the middle can be characterised as hermeneutic (Josselson & Lieblich, Citation1999). By moving back and forth between the data and the plot in different phases and taking into account the denouement of the story, it became clear which story elements contributed to the student teacher’s learning process (see Appendix 1 for a more detailed description).

Holistic-content and holistic-form analysis

In this second phase, the content and form of each story were analysed (Lieblich et al., Citation1998). The content was analysed in three steps. First, personal and professional themes regarding learning the teaching profession were studied. Second, to determine the dominance of the themes, a number of criteria were used, such as the extent to which the theme returned in the story and the importance that the student teachers attached to the theme. It became clear that the workplace learning process of each student teacher was dominated by one specific theme. Third, because of the results of the second step, it was decided to study the emergence of the dominant theme in each student teacher’s story. To this end, the fragments were selected in which the theme was introduced and the aspects were identified that played a role in its introduction (e.g. personal live experiences or professional demands from the practice school).

The form was analysed in three steps. First, notes were made of the plot development in all stories. According to Gergen (Citation1988), stories can be characterised on the basis of the progression of the plot: in a progressive story, the plot develops gradually; in a regressive story, the plot is typified by relapse and deterioration; and in a stable story, nothing changes with respect to the plot. These are three ideal-typical plots. In reality, however, more complex stories usually consist of combinations of these plots (Beijaard, Citation1995; see for an example of a more complex story). According to Gergen (Citation1988), plot analyses always refer to a specific theme. In this study, plot analyses were focused on the development of the dominant themes in the student teachers’ stories. Therefore, various criteria were used, such as evaluative comments by student teachers about their learning process (for example, ‘I see my learning process as a roller coaster.’) and words that refer to the form of the plot, such as development, stagnation and turning point (for example, ‘Since then I’m positive about myself.’). Second, for each story, all notes from the first step were compared in which the value of the various comments and words were determined against the background of the whole story. Then, if possible, all stories were divided into phases, for instance, a phase of relapse or progress. Third, for each story, the aspects that contributed to two consecutive phases (for example, a phase of progress that follows a phase of relapse) were studied.

Reliability and validity

The following measures were undertaken to ensure the reliability and validity of the data analysis. First, all constructed stories were sent to the participants for a member check. They all recognised their learning processes in the stories and judged the reconstruction of their learning processes as accurate. Second, in line with an audit procedure (cf. Akkerman, Admiraal, Brekelmans, & Oost, Citation2006), another researcher received a process document in which the entire procedure for the collection and analysis of the data was documented. To check the justifiability and acceptability of the analyses, the raw data from the digital log and in-depth interviews, the story written by the researcher, and the holistic-content and holistic-form analyses of the story of one student teacher were also placed at the disposal of the auditor. The manner in which the data were gathered and analysed was judged accurate and acceptable. Third, the results were illustrated with representative quotes from both the digital logs and the interviews.

Narrative research is relational by nature: stories of participants are shaped in interaction with the researcher (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006). Multiple measures were undertaken to regulate the subjective impact of the researcher on both collecting and analysing data. First, digital log and interview protocols were used. Second, in the learning process interviews as well as in the story-line interviews relational, temporal, and situational characteristics of learning were used as checkpoints for collecting data. Third, data were collected on multiple moments (during a period of two years of study). Fourth, a standard procedure was developed for reconstructing data into stories (McCormack, Citation2004; see Appendix 1). Fifth, all stories were analysed using standardised procedures (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; see holistic-content and holistic-form analysis).

Results

Overarching themes in the stories of the student teachers

A diversity of themes was found in the stories of the student teachers, such as the focus on developing lessons, working together with colleagues, and dealing with students with special needs. Striking was that the workplace learning process of each student teacher seemed to be dominated by one specific theme that the student teacher attached great importance to, that was relevant for his or her professional development, that returned constantly in his or her story, and that was unique for the student teacher (see ).

Table 3. Dominant themes in the workplace learning processes of the student teachers.

The emergence of dominant themes in student teachers’ stories

The dominant themes in student teachers’ workplace learning emerged in two ways: (1) student teachers came to the practice school with a specific theme, or (2) the themes emerged as the result of frictions between personal goals, beliefs, values, and attitudes from student teachers on the one hand, and professional demands from the practice school on the other hand.

Four student teachers came with a particular theme to the workplace. Before Mohamed started his school practice period, for example, he knew that he wanted to learn to develop and conduct a series of workshops. ‘I deliberately chose this practice school. My specific goal was, as I stated in my internship application, that I wanted to conduct a series of lessons. Developing and conducting real workshops.’

The dominant themes of the other six student teachers emerged as the result of frictions between the personal and the professional at the beginning of their school practice period (five student teachers) or during this period (one student teacher). Kathy, for example, observed a mentor’s lesson in the first week of her school practice period. He encouraged students to think about the subject and he regularly asked questions. The students were motivated. She was pleasantly surprised. ‘I thought giving lectures was a kind of knowledge transmission. I went to the same school but the way of teaching was completely different then. Teachers were talking, students were listening.’ As a result of this friction between her personal expectations and past experiences on the one hand, and the professional performance of her mentor on the other, Kathy decided she wanted to learn to teach interactively.

It became clear that the friction between the personal and the professional also played an important role in the appearance of the themes of the student teachers who came to the practice school with a particular theme. During his first workshops, Mohamed discovered, for example, that he had incorrectly estimated the level of the students. The assignments were too many and too difficult. ‘The students told me that all these tasks demotivated them. It was not at all successful.’ However, Mohamed was not convinced of the difficulty of the tasks. His experiences as a student were different. In addition, he wanted to challenge the students. But he also thought it was important that students were motivated. During his school practice periods, Mohamed’s dominant theme became more specific as the result of the friction between his personal conceptions of teaching and experiences as a student on the one hand, and the student behaviour in the classroom on the other hand: he focused more and more on developing and conducting workshops that are both challenging and motivating for the students.

Relations between personal life experiences and dominant themes

In eight of the ten stories, the analyses showed a strong relationship between the dominant theme and personal life experiences of the student teacher. Stephanie, for example, focused on developing self-confidence. She felt uncertain both as a teacher and as a person: she was afraid of asking stupid questions and was always nervous as she prepared her lessons. As a child, she was not uncertain at all. But after it became clear that her sister had anorexia, that changed. ‘From that moment on, all attention went to my sister. I was not even asked about my exams.’ As a result, she has become more reserved and unsure. In addition, her parents never really believed in her capacities. They thought she was incapable of becoming a teacher. ‘My parents often said: “Why don’t you quit? You are not a good student. Let it go.” Even after I had finished my first year of study.’ And because her parents paid for her education, she worked extra hard for it. ‘If I don’t become a teacher, then I have failed.’

This example shows how Stephanie’s dominant theme (developing self-confidence) is connected to her feelings of uncertainty, which she related to an experience from her childhood (the lack of interest her parents had shown towards her). More indirectly, her uncertainty seemed to arise from her fear of failure, which was fuelled by the limited confidence her parents had in her ability to succeed.

Workplace learning with respect to the dominant themes

Five student teachers experienced their workplace learning process as discontinuous, the other five as continuous.

Discontinuous learning

The learning process for five out of the ten student teachers could be described as follows: the friction between the personal and the professional led to a crisis and turning point in student teachers’ workplace learning. Two conditions were important for realising the turning point: an external stimulus (such as a project from the teacher education institute) and letting go personal convictions (such as the idea that teachers do not make mistakes). An example of this learning process:

Friction

George struggled with how he could make contact with his students without losing his personal and professional self-image (dominant theme). He had trouble with his students’ behaviour: they were restless, talked too much, and didn’t listen. He had expected that students would accept the authority of the teacher. At his previous practice school, students were much quieter and he himself was an obedient student. According to his mentor, this behaviour is part of the school culture. ‘My mentor said: “You should be more tolerant. It’s part of the culture. Maybe you should study this culture first.”’

Crisis

George looked for a way to connect with his students but he could not just set aside his own conceptions of and expectations about student behaviour. These are related to his own self-image: quiet and orderly. However, he himself was not able to behave that way: he shouted for order and constantly tried to correct the behaviour of his students. When he discussed the issue with his colleagues, they told him that he had to get used to it. He concluded that he was all alone with his problem. He did not know anymore what it meant to keep order, and felt compelled to adopt his colleagues’ standards. But that was not what he wanted. ‘That conflicts with who I am.’ He became unsure, and began to doubt to himself.

Turning point

A few months later, a solution was announced. After George had a conversation with a student, his mentor told him that he had to listen better: George interpreted too quickly and needed to learn to ask questions. George agreed, and practised this weekly. He tried to be restrained during conversations with his students, and he asked questions. He discovered listening was a way of connecting with his students. ‘Good listening and being open. I also asked students what kind of lessons they preferred. They wanted more action, interaction.’ He let go of his conceptions of and expectations about student behaviour, and his interactions with students improved slowly.

This example shows how the friction between the personal (George’s conceptions of and expectations about student behaviour, personal self-image) and the professional (student behaviour, conceptions and behaviour of his mentor and colleagues) resulted in a crisis (he did not know anymore what it meant to keep order, he became unsure, he began to doubt himself). The conditions that resulted in a turning point included feedback from his mentor (better listening to students) and letting go of personal convictions (conceptions and expectations).

The turning point did not always lead to better learning. Mary, for example, strongly believed in student-centred teaching but her mentors forced her to focus on transmitting knowledge to students. This friction led to a crisis (Mary struggled with motivation problems; she felt helpless and angry, and she even wanted to quit teacher education) and to a turning point in her learning process (to survive she accepted her mentors’ conceptions). This example shows that the turning point in Mary’s workplace learning was important for her welfare but not necessarily for her development as a teacher.

Continuous learning

The workplace learning process of the other five student teachers was a steady process in which the student teachers connected their practical experiences relatively easily with previous knowledge of and experiences with their dominant theme. Striking was that certain practical experiences constantly returned in these processes. Mike, for example, had trouble switching between his experience as a professional cook and his role supervising students in the kitchen. His expectations were much too high, an experience that returned again and again during his school practice periods. February 2010. Mike took over a student’s work because she worked too slow. ‘I said: “Let me just quickly do it, because we have to hurry up. Go work on something else. This is taking too long.”’ March 2010. Mike reprimanded a student because cleaning a cutting machine took too long. June 2010. Mike took over a student’s work because she operated awkwardly. December 2010. Mike explained to a student how she could calculate the relationship between a litre and a decilitre, but he did it much too fast. In all examples, Mike later realised that he took the standards of his experiences as a professional cook as starting point in guiding students. ‘In a professional kitchen, it’s all about the money. Once you have internalized that … That’s what stays with you.’

It seems that the recurring practical experience indicates a stagnation in Mike’s learning process. This applies, for instance, not for the learning of Mohamed. Throughout his learning process, Mohamed repeatedly became aware of the importance of adjusting his lessons to the level of the students. However, he seemed to develop as a teacher: one time, for example, he became aware of what students expect from his lessons, another time he realised that he must attune the content of his lessons to the internships of the students. ‘Students can recognize it more easily. That motivates them.’ Each time, Mohamed discovered a new aspect of the learning process of his students.

Discussion

Themes in workplace learning

The holistic-content analysis of the stories showed that although student teachers focused on various themes during workplace learning, one theme dominated the learning process of each student teacher. It concerned a theme to which the student teacher attached great importance, that was relevant for his or her professional development, and that constantly returned throughout his or her learning process. The themes differed per student teacher, ranging from student-centred teaching to developing and conducting workshops, and were almost always connected to personal life experiences. Literature on teachers’ professional identity has already mentioned the inextricable relationships between teachers’ lives and teaching experiences (e.g. Meijer et al., Citation2009). Kissling (Citation2014) has found the existence of what he calls ‘curricular currents’ within this set of experiences, ‘themes across a subset of the experiences of a person’s life’ (p. 83), such as overcoming adversity and cultivating care for others. According to him, these themes shape the learning and teaching of student teachers. Olsen (Citation2008) came to a similar conclusion in his study on student teachers’ knowledge construction and has called these themes ‘life themes.’ Olsen defines a life theme as ‘an intertwined set of biographical events and influences, understandings, and dispositions that acts as an interpretive pattern’ (p. 77). Because one’s life themes produce personal ways of interpreting experience, biographical and professional lives are inextricably related. Kissling and Olsen explain their findings by referring to the continuous character of learning: current themes in student teacher learning stem from previous life experiences of student teachers. This could also be an explanation for the existence of the dominant themes in student teachers’ workplace learning (see the example of Stephanie, whose dominant theme ‘developing self-confidence’ was connected to her feelings of uncertainty, which she related to the lack of interest her parents had shown towards her). Moreover, our research shows that the relationships between the personal and professional aspects of becoming a teacher result in one overarching theme that dominates the workplace learning process of the student teacher. Interesting is that frictions between personal goals, beliefs, values, and attitudes from student teachers on the one hand and professional demands from the practice school on the other hand played a role in the emergence of the dominant themes in the learning processes of all student teachers. In the light of the above, it could be that the dominant themes did not ‘emerge’ but were ‘discovered’ during workplace learning, uncovered by the frictions between the personal and professional of becoming a teacher. From this point of view, the student teachers’ dominant themes can be typified as professional identity themes because all themes appeared to be both personal and professional (Beijaard et al., Citation2004), and emerged—or were uncovered—in confrontation with the professional demands from the workplace.

Kissling (Citation2014) notes that curricular currents are ‘predicated on the fact that people’s lives are complex and messy, never definable by one overarching theme’ (p. 83). In this sense, he argues, a current is current, ‘it is in the present, unfolding in all its complexity, coinciding with all of the ongoing aspects of a person’s life’ (p. 83). Although our study shows that the learning process of each student teacher was dominated by one specific theme, it could be that such a theme changes during a teacher’s life, depending on changing relationships between the personal life stages of a teacher and the professional demands from the workplace. More (longitudinal) research on professional identity themes in workplace learning is needed to gain a better understanding of how personal life experiences (e.g. getting children, the death of a parent or a partner, a burn-out) influences the development and functioning of teachers during their professional careers (cf. Goodson, Citation2008).

Workplace learning with regards to the themes

The holistic-form analysis of the stories showed that half of the student teachers experienced their workplace learning as discontinuous, and the other half as continuous. The discontinuous learning process was a path in which frictions between the personal and the professional led to a crisis and turning point in student teachers’ workplace learning, which mainly is in line with the results of the study by Meijer et al. (Citation2011). They concluded that many of the student teachers experienced times of downward mobility followed by a period of growing optimism. The crisis in workplace learning was the result of the friction between the personal and the professional. Pillen et al. (Citation2013) have also found that such frictions can lead to real identity tensions for student teachers. Striking was that these frictions also played an important role in the emergence of the dominant themes in workplace learning of all the student teachers and fuelled this learning. Tensions, thus, seem inextricably related to the discontinuous workplace learning process.

The results indicate that an external stimulus and letting go of personal convictions were important conditions for realising the turning point in the discontinuous learning process. Personal convictions about teaching, such as the idea that students need to sit still and be quiet, seemed to hinder the learning process of student teachers. However, we need to be critical on the meaning of this finding; letting go of personal convictions is an important condition for realising a turning point in workplace learning, but it does not automatically result in better learning. It is possible, for example, that student teachers let their convictions go because that is required by their mentor. Rajuan, Beijaard, and Verloop (Citation2007) have found that student teachers and mentors often differ in their conceptions of teaching students. This can lead to internal tensions for student teachers (see the example of Mary). Furthermore, it is possible that student teachers do not have the ability to teach in accordance with their personal ideas. This can lead to feelings of failure or frustration (Meijer et al., Citation2011). The literature on professional identity often emphasises the importance of integrating or reconciling the personal and the professional of becoming and being a teacher (e.g. Brilhart, Citation2007; Lipka & Brinthaupt, Citation1999; Olsen, Citation2011). Our study implies that frictions between the personal and the professional can lead to tensions and frustrations, but also act as stimulators for student teachers’ workplace learning (see also Meijer, Citation2011). According to Illeris (Citation2009), transformative learning often occurs ‘as the result of a crisis-like situation caused by challenges experienced as urgent and unavoidable, making it necessary to change oneself to get any further’ (p. 14). Illeris argues that the personal side of identity usually is very stable due to a life-long socialisation process; it only changes when the learner is convinced of the need for it (cf. Illeris, Citation2014). The example of George regarding strong conceptions of and expectations about student behaviour showed that frictions between the personal and the professional led to a crisis that seemed necessary for letting go of his personal convictions. For stimulating student teacher development, it is important to consider both these possible effects of frictions on learning.

The discontinuous learning process of student teachers was also characterised by a certain degree of continuity. Despite the fact that this learning process was a path with highs and lows, student teachers continued to focus on their dominant themes during their learning. This finding is consistent with the previous discussion on the existence of ‘curricular currents’ or ‘life themes’ in student teacher learning; professional identity themes run like a thread through the learning processes of student teachers and ensure continuity in this learning. Akkerman and Meijer (Citation2011) argue in their paper on conceptualising teacher identity the necessity of experiencing continuity in identity: persons give meaning to their experiences by interpreting these experiences narratively, which means that they shape their understandings by stories of who they and others are. Persons not having a sense of personal continuity show psychological problems. Such persons are not able to position themselves in relation to a personal past and an anticipated future; they fall into a so-called ‘temporal flux of incoherence’ (Akkerman & Meijer, Citation2011, p. 313). From this point of view, professional identity themes as storied phenomena in student teachers’ workplace learning can be seen as portals through which professional experiences are interpreted and made personally meaningful (cf. Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2006).

The continuous learning process was a path in which student teachers connected their practical experiences relatively easily with previous knowledge of and experiences with their dominant theme, and that was typified by a certain recurring practical experience. Mike, for example, repeatedly realised that he took his professional standards as a cook as starting point in guiding students. This might indicate the strong influence of outside-school contexts on student teachers’ workplace learning (Leeferink et al., Citation2015), but also a stagnation in this learning.

The continuous learning process also contained discontinuities, namely, the frictions between personal goals, beliefs, values, and attitudes of student teachers on the one hand, and professional demands of the practice schools on the other hand. The dominant themes in this learning process, for example, are the result of these frictions. These discontinuities did not lead to highs and lows in the continuous learning process of the student teachers; they should be seen rather as constructive frictions that initiate this process (cf. Meijer, Citation2011).

Limitations and suggestions for further research

A first limitation pertains to the generalisability of the results. Only a small group of student teachers participated in this study. Also, data were collected by means of digital logs and interviews, which strongly rely on self-reflection. In future research, it would be useful to rely on multi-method triangulation, and also collect data, for example, trough participant observation. By doing so, ‘telling stories’ about workplace learning are supplemented with ‘living stories’ (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990) whereby a more complete picture will be obtained of student teacher learning. Furthermore, this study focused on the development of personal themes during student teacher workplace learning but obtained no insight into the quality of this type of learning. Continuous workplace learning, for example, was typified in our study by a certain recurring practical experience. It remained unclear, however, to what extent this denotes stagnation in the student teacher’s learning process. It would be interesting therefore to investigate to what extent the continuous and discontinuous learning processes lead to professional development.

Implications for practice

Teacher educators and mentor teachers can help student teachers find ways to support insights into professional identity themes and how these develop during workplace learning, for example, by making use of stories. Stories are powerful tools for reflecting on learning processes and useful for helping student teachers themselves to make sense of what themes they focus on during learning (Lieblich et al., Citation1998) and how they learn (Goodson et al., Citation2010). By encouraging student teachers to tell and write stories about their workplace experiences over a longer period (for example, one year of study) and help them interpret the content and form of these stories, student teachers can obtain insight into the nature and development of their professional identity themes. Furthermore, teacher educators and mentors could consider the development of student teachers in the light of professional demands. The focus on professional identity themes can be advantageous for professional development, but can also confine it. Mentors can cause friction in workplace learning by confronting student teachers with themes they consciously or unconsciously avoid during their learning, but that are necessary to develop as a teacher. Mentors can also help student teachers cope with crises during workplace learning. Student teachers can experience tensions accompanied by negative feelings. Mentors can, for instance, provide student teachers with examples of frictions that have led to turning points in professional development (see the example of George described before).

Conclusion

Through reconstructing workplace learning processes of 10 student teachers into stories and unravelling these stories using a holistic-content and holistic-form approach, it can be concluded that the workplace learning process of each student teacher is dominated by one overarching professional identity theme. This theme seems rooted in the personal biography of the student teacher, runs like a thread through the student teacher’s workplace learning process, and emerges—or is uncovered—as the result of frictions between the personal and professional of becoming a teacher. The themes differ per student teacher; each theme is unique, resulting from interactions between personal and professional aspects of learning to teach.

Furthermore, from a professional identity perspective, student teacher workplace learning is both continuous (e.g. ongoing focus of student teachers on professional identity themes) and discontinuous (e.g. frictions between personal beliefs of student teachers and professional demands from the practice school). The continuous may indicate a process in which student teachers develop gradually by connecting new and previous knowledge and experiences (see the example of Mohamed) but it may also indicate stagnation because of the recurring practical experience of student teachers during this process (see the example of Mike). The discontinuous can both stimulate and hinder student teacher development. Frictions between the personal and the professional can initiate the student teacher’s learning process (see the example of George) but also frustrate it (see the example of Mary). Mentor teachers should pay attention to these different effects and fit their guidance to this learning, because the implications of continuities and discontinuities in workplace learning can differ per student teacher.

In this study, it was assumed that the complexity of student teachers’ workplace learning is encapsulated in and can be understood by investigating student teachers’ stories. The findings indicate that reconstructing data into stories and unravelling these stories is a useful technique for understanding student teacher workplace learning as a result of the interaction between personal and professional aspects of becoming a teacher.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Han Leeferink

Han Leeferink worked as a teacher educator at Fontys University of Applied Sciences and as a postdoctoral researcher at the Radboud Teachers Academy of the Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands. In 2016, he successfully defended his doctoral dissertation on student teacher workplace learning at the Eindhoven School of Education of the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands.

Maaike Koopman

Maaike Koopman is an assistant professor at Eindhoven School of Education, a department of Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. Her research focusses on the interplay between teaching - in terms of (student) teachers’ knowledge, conceptions and behaviour - and student learning, particularly in innovative learning environments.

Douwe Beijaard

Douwe Beijaard is a professor of education and former dean of the Eindhoven School of Education (ESoE) of the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands. His research interests particularly pertain to the professional development, identity and quality of (student) teachers.

Gonny, L. M. Schellings

Gonny Schellings is assistant professor at the Eindhoven School of Education of the Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands. Her research interests concern professional identity development of (beginning) teachers and professional learning of teacher educators. She received her PhD in 1995 on a study into learning strategies applied in order to learn from instructional texts. At the moment, she is a regional project leader of a national founded government project to support beginning teachers.

References

- Akkerman, S. F., Admiraal, W., Brekelmans, M., & Oost, H. (2006). Auditing quality of research in social sciences. Quality & Quantity, 42(2), 257–274.

- Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 308–319.

- Alsup, J. (2006). Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ball, D., & Cohen, D. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In L. Darling-Hammond & G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession (pp. 3–32). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Beijaard, D. (1995). Teachers’ prior experiences and actual perceptions of professional identity. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 1(2), 281–294.

- Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128.

- Beijaard, D., van Driel, J., & Verloop, N. (1999). Evaluation of story-line methodology in research on teachers’ practical knowledge. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 25, 46–62.

- Brilhart, D. L. (2007). Teacher conceptualization of teaching: Integrating the personal and professional(Doctoral Dissertation). Ohio State University, Columbus.

- Bronkhorst, L. H., Koster, B., Meijer, P. C., Woldman, N., & Vermunt, J. D. (2014). Exploring student teachers’ resistance to teacher education pedagogies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 73–82.

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Clandinin, D. J., & Murphy, M. S. (2009). Relational ontological commitments in narrative research. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 598–602.

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. Green, G. Camilli, & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 375–385). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Connelly, F. M, & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2-14. doi:10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Cortazzi, M. (2014). Narrative analysis. London, England: Routledge.

- Coulter, C. A., & Smith, M. L. (2009). The construction zone: Literary elements in narrative research. Educational Researcher, 38(8), 577–590.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Evaluating teacher effectiveness: How teacher performance assessment can measure and improve teaching. Washington: Center for American Progress.

- Feiman-Nemser, S., & Buchmann, M. (1985). Pitfalls of experience in teacher preparation. Teacher College Record, 87(1), 53–65.

- Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 219–232.

- Gergen, M. M. (1988). Narrative structures in social explanation. In C. Antaki (Ed.), Analysing social explanation (pp. 94–112). London: Sage.

- Goodson, I. F. (2008). Investigating the teacher’s life and work. Rotterdam & Taipei: Sense.

- Goodson, I. F., Biesta, G. J. J., Tedder, M., & Adair, N. (2010). Narrative learning. London, England: Routledge.

- Hagger, H., & McIntyre, D. (2006). Learning teaching from teachers: Realizing the potential of school-based teacher education. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Illeris, K. (2009). A comprehensive understanding of human learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning (pp. 7–20). London/New York: Routledge.

- Illeris, K. (2014). Transformative learning and identity. London/New York: Routledge.

- Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (1999). Making meaning of narratives: The narrative study of lives (Vol. 6). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Kelchtermans, G. (1994). Biographical methods in the study of teachers’ professional development. In I. Carlgren, G. Handal, & S. Vaage (Eds.), Teachers’ minds and actions: Research on teachers’ thinking and practice (pp. 93–108). London, England: Routledge.

- Kissling, M. T. (2014). Now and then, in and out of the classroom: Teachers learning to teach through the experiences of their living curricula. Teaching and Teacher Education, 44, 81–91.

- Leeferink, H., Koopman, M., Beijaard, D., & Ketelaar, E. (2015). Unraveling the complexity of student teachers’ learning in and from the workplace. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(4), 334–348.

- Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Lipka, R. P., & Brinthaupt, T. M. (Eds.) (1999). The role of self in teacher development. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

- McCormack, C. (2004) Storying stories: A narrative approach to in-depth interview conversations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 7(3), 219–236.

- McLean, V. S. (1999). Becoming a teacher: The person in the process. In R. P. Lipka & T. M. Brinthaupt (Eds.), The role of self in teacher development (pp. 55–91). New York: State University of New York Press.

- Meijer, P. C. (2011). The role of crisis in the development of student teachers’ professional identity. In A. Lauriala, R. Rajala, H. Ruokamo, & O. Ylitapio-Mäntylä (Eds.), Navigating in educational contexts: Identity and cultures in dialogue (pp. 41–54). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Meijer, P. C., de Graaf, G., & Meirink, J. A. (2011). Key experiences in student teachers’ development. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(1), 115–129.

- Meijer, P. C., Korthagen, F. A. J., & Vasalos, A. (2009). Supporting presence in teacher education: The connection between the personal and professional aspects of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(2), 297–308.

- Meijer, P. C., Verloop, N., & Beijaard, D. (2002). Multimethod triangulation in a qualitative study on teachers’ practical knowledge: An attempt to increase internal validity. Quality and Quantity, 36, 145–167.

- Mutton, T., Burn, K., & Hagger, H. (2010). Making sense of learning to teach: Learners in context. Research Papers in Education, 25(1), 73–91.

- Olsen, B. (2008). Teaching what they learn, learning what they live: Professional identity development in beginning teachers. Boulder/London: Paradigm Publishers.

- Olsen, B. (2011). “I am large, I contain multitudes”: Teacher identity as a useful frame for research, practice, and diversity in teacher education. In A. F. Ball & C. A. Tyson (Eds.), Studying diversity in teacher education (pp.257–273). Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Opfer, D. V, & Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teaching and Teacher professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 81(3), 376–407.

- Pillen, M. T., Beijaard, D., & Den Brok, P. J. (2013). Professional identity tensions of beginning teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 19(6), 660–678.

- Pinnegar, S. (2005). Identity development, moral authority and the teacher educator. In G. F. Hoban (Ed.), The missing links in teacher education design (pp. 259–279). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Polkinghorne, D. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. In A. J. Hatch & R. Wisniewski (Eds.), Life history and narrative (pp. 5–23). London, England: Falmer Press.

- Rajuan, M., Beijaard, D., & Verloop, N. (2007). The role of the cooperating teacher: Bridging the gap between the expectations of cooperating teachers and student teachers. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 15(3), 223–242.

- Rodgers, C. R., & Scott, K. H. (2008). The development of the personal self and professional identity in learning to teach. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, & D. J. McIntyre (Eds.), Handbook of Research on teacher Education (pp. 732–755). New York: Macmillan.

- Smagorinsky, P., Cook, L. S., Moore, C., Jackson, A. Y., & Fry, P. G. (2004). Tensions in learning to teach: Accommodation and the development of a teaching identity. Journal of Teacher Education, 55 (1),8–24.

- Stenberg, K., Karlsson, L., Pitkaniemi, H., & Maaranen, K. (2014). Beginning student teachers’ teacher identities based on their practical theories. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37, 204–219.

- Trent, J. (2011). ‘Four years on, I’m ready to teach’: Teacher education and the construction of teacher identities. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(5), 529–543.

- Webster-Wright, A. W. (2009). Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 702–739.