ABSTRACT

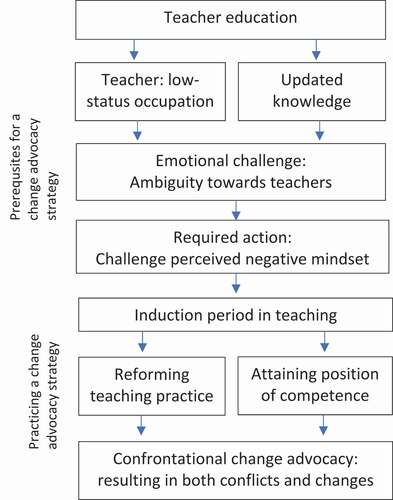

Beginning to teach after teacher education is commonly depicted as an emotionally challenging period. Beginning teachers deploy strategies to cope with the emotionally challenging transition from teacher education and starting a position as a teacher. One way of coping is trying change the origin of the challenges. The aim of the study was to investigate how teachers in their last year as student teachers and their first year as teachers make meaning of a change advocacy strategy to cope with challenging situations as teachers. A qualitative interview study was performed. Twenty-five participants were interviewed while studying in their last year of teacher education, and 20 were interviewed again after having worked as a teacher for a year. In between, 68 self-reports were collected. The material was analysed using constructivist grounded theory tools. The findings show that as student teachers the participants identified two prerequisites to be able to use the change advocacy strategy as beginning teachers: (1) establishing teacher ambiguity and (2) challenging the perceived negative mindset. When utilising a change advocacy strategy as beginning teachers, the participants tried to reform teaching practices and attain a position of competence.

The first years of teaching are a crucial period for professional development and career pathways (Voss et al., Citation2017). Starting to teach can result in a number of positive experiences, professional learning opportunities and positive emotions, such as increasing classroom management skills (Voss et al., Citation2017), enjoyment (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013; Jokikokko et al., Citation2017), positive relationships with students, and inspiring learning and teaching situations (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013). At the same time, the beginning phase of teaching has commonly been depicted as emotionally challenging (Le Maistre & Paré, Citation2010), and previous research has demonstrated a ‘reality shock’ experienced by novice teachers in their transfer from teacher training into the workplace (Caspersen & Raaen, Citation2014; Dicke et al., Citation2015).

Beginning teachers may experience unexpectedly high psychological task/job demands (Harmsen et al., Citation2018), classroom management difficulties (Çakmak et al., Citation2019; Dicke et al., Citation2015; Voss et al., Citation2017), student aggression and misbehaviour (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013; Çakmak et al., Citation2019), poor school climate and relationships with colleagues (Harmsen et al., Citation2018), professional identity tensions and dilemmas (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013; Jokikokko et al., Citation2017; Pillen et al., Citation2013), struggling with instruction (Çakmak et al., Citation2019), and difficulties in meeting students’ needs, including special needs (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013; Hyry-Beihammer et al., Citation2019). If they do not learn to deal with challenging and distressing situations in an effective way, these experiences might lead to teacher uncertainty (Caspersen & Raaen, Citation2014), feelings of helplessness (Pillen et al., Citation2013) and burnout (Harmsen et al., Citation2018; Sharplin et al., Citation2011; Voss et al., Citation2017), which, in turn, increase the risk of negative teaching behaviour and attrition (Harmsen et al., Citation2018).

Thus, although the first years of teaching include a lot of joy and other positive emotions as well as promising professional development, efforts and job satisfaction for many beginning teachers, these years can also encompass a range of emotionally challenging experiences, with negative outcomes. Therefore, there is a need to further explore student teachers’ and beginning teachers’ experiences of and ways of coping with emotional challenges in teacher education and starting to teach, which has been the focus in the current study. We have studied the transition into a teaching position by following the participants from the end of teacher education to their first teaching position.

How beginning teachers cope with emotional challenges

According to the transactional stress model (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), perception of stress is produced by a complex and subjective interplay (transaction) between situational demands and individual resources. When facing a stressful, threatening or challenging situation, individuals evaluate the situation, how it might affect their wellbeing, and whether they can deal with the situation. Coping strategies can be understood as individuals’ cognitive and behavioural efforts aimed at reducing and overcoming challenges (Chaaban & Du, Citation2017). Coping strategies can be categorised as direct-action strategies aimed at eliminating the sources of stress, and palliative strategies that focus on reducing stress by modifying internal/emotional reactions instead of eliminating the cause (Sharplin et al., Citation2011). This distinction is in line with the two types of coping strategies coined by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) as problem-focused and emotion-focused.

There is a growing body of research on teacher coping (e.g. Herman et al., Citation2020; Oplatka & Iglan, Citation2020; Pogere et al., Citation2019) but studies have focused little on the ways that beginning teachers cope with emotional challenges. In their study, Pillen et al. (Citation2013) found speaking to a significant other and searching for a solution oneself to be the two most reported coping strategies, followed by putting up with the situation among beginning teachers. Based on self-report data, Sharplin et al. (Citation2011) found that beginning teachers used three categories of coping strategies: (a) direct-action strategies (i.e. stress source elimination, e.g. getting information, seeking assistance from colleagues and establishing work boundaries), (b) palliative strategies (i.e. reducing stress by modifying internal/emotional reactions, e.g. positive self-talk, accepting, establishing psychological boundaries and use of humour), and (c) avoidance (e.g. ignoring, denying and psychological or physical withdrawal).

Thus, one way of coping as a beginning teacher involves the direct-action strategy of seeking support from colleagues. Even so, collegiality at schools might not always be a positive encounter (Löfgren & Karlsson, Citation2016). Conflicts with colleagues are in fact sometimes the source of emotional challenges (Lindqvist et al., Citation2019). When starting to teach, beginning teachers encounter different expectations which may not align with their own values (Flores & Day, Citation2006). This could result in emotional challenges and motivate them to use a direct-action (i.e. problem-focused) strategy that may alter the origin of the emotional challenges, here depicted as a change advocacy strategy (Lindqvist, Citation2019): efforts in changing the school to better fit with the beginning teacher’s values, ideals and expectations.

Change advocacy in a specific school setting

Every school is a specific arena due to the fact that all schools have teachers who are making sense of their practice. In this process, alliances and competition arise. Micro-political perspectives of relationships among professionals in a school and the influence used to exert power in a school could thus explain community-building as well as conflicts in teacher groups (Achinstein, Citation2002). In research, it is common for new teachers to be viewed as needing support (McCormack & Thomas, Citation2003). Ulvik and Langørgen (Citation2012), however, focus on the strengths of beginning teachers and find that there are numerous areas where established teachers can learn from beginning teachers, even though this rarely happens.

The focus of this study is change advocacy, since the core of acting for change involves influencing other teachers to do something different, using informal power, coalitions and collaborations, as well as cognitive conflict (Lima, Citation2001). Change advocacy is the main focus of the present study, building on a previous study (Lindqvist, Citation2019). It was found to be a feature among student teachers. In the current study, we wanted to investigate the development of this strategy among beginning teachers. Change advocacy is here defined as deliberate efforts to overcome adversity through strategies that involve acting for change in the school setting. Not letting beginning teachers influence school development might lead to attrition of beginning teachers, with schools losing expertise from former high-achieving student teachers (Johnson et al., Citation2019). They can be an active part in teachers’ collaborative efforts, but mainly if more high-status teachers create the space for beginning teachers to initiate discussions of problems that they experience in practice (Sutton & Shouse, Citation2019). Schools can be understood as micro-political settings where informal power, coalitions and conflicts arise between different actors working in the school (Ball, Citation1987). Both the coping strategy of change advocacy and a micro-political lens (Achinstein, Citation2002) have been used as sensitising concepts in the study.

The current study

The aim of the study was to investigate how teachers in their last year as student teachers and their first year as teachers make meaning of a change advocacy strategy to cope with challenging situations as teachers. In line with the ambition of understanding how beginning teachers cope with experienced emotional challenges, our research questions are: (1) how is the change advocacy strategy discussed by student teachers during teacher education, and (2) how is a change advocacy strategy deployed starting to teach?

Method

We adopted a constructivist grounded theory (GT) approach (Charmaz, Citation2014), because of our interest in social processes and participants’ meaning-making. Constructivist GT was well suited for the current study because we were interested in exploring the participants’ perspectives (Charmaz, Citation2014), as well as how they resolve emergent problems, commonly described as an objective connected to GT (Glaser, Citation1978).

Participants

A qualitative interview study was performed, interviewing the participants twice over a period of two years—once at the beginning of their last year in teacher education and once after having worked a year as a teacher, after teacher induction. The data set consists of 25 initial interviews, 20 follow-up interviews and 68 written self-reports. Twenty-five participants were interviewed at the start of their last year in teacher education and were asked to submit two self-reports in order to answer the first research question. To address the second research question, 20 of the participants were interviewed again after one year working as a teacher and submitted one self-report as beginning teachers. The participants are presented in .

Table 1. Participants

Data collection

The first interview focused on emotionally challenging situations in teacher education, field training and their concerns about working as a teacher in the future. In the second interview, expectations and concerns discussed in the initial interview and in self-reports were revisited. This allowed the participants to reflect on themes from the previous interview and self-reports. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. All names are fictional in the text. The interviews were carried out both in person and via a video conference service. The interviews varied from 30 to 90 minutes in length (M = 66.95; SD = 12.62). To increase the credibility and trustworthiness of the interview data, the first author, who conducted all the interviews, applied a non-judgemental and active listening approach, and confirmed with relevant follow-up questions (e.g. ‘Could you tell me more about … ?’, ‘What do you mean?’, ‘Tell me more’, ‘What do you think about that?’, and ‘Previously, you said … ’) (e.g. King, & Horrocks, Citation2010).

Between the initial and follow-up interviews, three waves of written self-reports were submitted by each participant as they progressed from student teachers to beginning teachers. 25 participants submitted the first self-report, 24 participants the second, and 19 participants the third self-report. There were different reasons for the reduced number of self-reports, for example, two participants were on maternity leave. The word count of the self-reports ranged from 101 to 2,546 words (M = 525.30, SD = 397.11). The first self-report included different questions for all participants, for example: ‘During the interview, you discussed inadequacy as not being certain of the effect your teaching will have. Is this something you discussed with other students or teachers at the university?’ The second self-report was collected at the end of the same term that the student teachers graduated and focused on anticipated challenges about starting to teach. The third self-report asked about experiences having worked for six months, with focus on challenges. Our ambition was to use the self-reports to describe the transition from teacher education to starting to teach and to use the self-reports when conducting the follow-up interviews.

Data analysis

The analysis involved coding, constant comparison, memo writing and memo sorting within the research process (Charmaz, Citation2014; Glaser, Citation1978; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Initial, focused and theoretical coding was performed. The initial coding was done word-by-word, sentence-by-sentence and segment-by-segment, with a focus on the actions of the participants (Charmaz, Citation2014). This process created a vast number of codes that were used in the focused coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). In the focused coding, iterative definitions of categories were constructed and elevated, and guided further data analysis and coding. More or less in parallel, theoretical coding was used when trying out relationships between the codes (Glaser, Citation1978). In line with informed grounded theory, theoretical agnosticism and theoretical pluralism were guiding principles (Thornberg, Citation2012). All the authors critically scrutinised our work, as such the trustworthiness of the coding was enhanced through critical dialogue procedures within the research group.

Ethical considerations

The study was given ethical approval by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2014/1088-31/5). The participants in the study were informed about the purpose of the study. Their rights as participants were discussed before data collection, and they gave informed consent to participate in the study. They were informed about how the data was to be used within the project, that their participation was voluntarily, that they could withdraw their participation at any time and that fictitious names would be used to ensure confidentiality.

Findings

The findings show that one way of dealing with emotional challenges that the participants encountered is to attempt to change the origin of the challenges. The findings further develop rationales and distinctions of an action-directed coping strategy that Lindqvist (Citation2019) terms change advocacy strategy. The change advocated was a part of the participants' ongoing process of sense-making, and what Kelchtermans (Citation2009) describes as their personal interpretative framework.

Prerequisites of change advocacy strategies

The participants’ use of change advocacy strategies was perceived to alleviate future emotional challenges anticipated from experiences during teacher education. The participants described their cultural-ideological interpretation as a basis for using the strategy. During teacher education an ambiguity towards teachers was established and influenced by the common discussion of teachers in Sweden as a low status occupation. (cf. OECD, Citation2015):

In the beginning I was afraid of telling people I was studying to become a teacher because people would say ‘are you going to be one of those people’. You know the complaining type. (Claire, interview 1)

The prerequisites of the emotional challenge of (1) establishing teacher ambiguity and preparing to (2) challenge the perceived negative mindset were the foundations for using change advocacy in the future.

Establishing teacher ambiguity

Established teacher ambiguity is defined as experiencing both admiration and disappointment from meeting teachers during teacher education. As described by Kelchtermans and Ballet (Citation2002) the participants’ cultural-ideological interests were made visible in regard to their ideas concerning the favourable conduct and professional practice of teachers. For example, Catrin reported an incident she interpreted as unethical teacher behaviour, further establishing her ambiguity against teachers.

I think the teacher crossed the line for what is acceptable. What the teacher said, and how he said it, I consider to be an abuse of authority and offensive conduct. When the teacher was done scolding, my old supervisor and I got what we came for and went back to our classroom./ … /When I was alone with my supervisor, I said I didn’t think that it was okay to act the way the teacher had done in the classroom. My supervisor agreed. (Self-report 1, Catrin)

The participants described a resistance to change in the school culture and among teachers, something that school consultants have also experienced and reported in other studies (e.g. Rubinson, Citation2002; Spratt et al., Citation2006; Thornberg, Citation2014). Linn, for instance, discussed a collision between what had been taught in teacher education (ideals, ethics, scientific theories and research-based knowledge) and what she experienced when entering the school (collegial taken-for-granted tacit knowledge and practice), associated with change resistance in the school culture.

Linn: Because when you come to a school you often hear ‘Well, you’ve been at university, but this is what works here’. It feels as if you’re opposed when you have another approach that we have learnt at university.

H: What are your thoughts about that?

Linn: I hope I will have the strength to stand my ground to do certain things, because during field training it was like ‘No, we don’t do that here’(Interview 1)

Linn encountered a school practice where she considered innovation hard to establish. These challenges added to ambiguity about future colleagues. Katarina noticed that refraining from enforcing school rules that she considered to be wrong could mean problems with colleagues.

It’s not discussed, whether we should question the rules, update them or discuss them. It’s not really done. It’s viewed as if the rules are as they are, and that you can’t change them basically (Interview 1, Katarina).

She interpreted the lack of discussion as an obstacle to changing the problem that emotionally challenged her. The rules in school were simply taken for granted in the school culture and not open for discussion, negotiation and revision, including the rules that were not aligned with her view of how to be a good teacher. In order to challenge the portrayal of recurrent negative interpretations by teachers they met, the participants thought they had to challenge the perceived negative mindset of teachers when beginning to teach.

Challenge the perceived negative mindset

The participants encountered negative teachers and anticipated meeting negative teachers again in the future. Claire discussed how she did not want to become like certain teachers, who refrained from intervening when something happened. She argued that these teachers had given up on what was important in teaching.

Of course, you don’t have time. But sometimes I’m like, how long does it take to ask, to say ‘Hi’ and ‘How are you’, ‘Why are you sitting here?’. How many minutes does that take? But you can sit and drink coffee for 20 minutes. In a way I might be naive because I’m new and haven’t gotten into everything yet, but then I want to be naive and not become like the older ones. (Interview 1, Claire)

Pia also described how she felt when she encountered a negative attitude. She came across teachers who talked about the negative aspects of teaching and said that such experiences drained her energy: ‘You can be like, you need a positive spark, like, “Yes it sucks today, but we’ll do it anyway”. Some of that attitude, not just negativity all the time’ (Interview 1, Pia). Maintaining idealism was viewed as important in order to be able to work for change, as portrayed by Lotta.

I think that people, most of them anyway, reproduce what they hear and suddenly they start to think and question themselves, and I do too, and suddenly, ‘Wait a minute’ and change is achieved. Maybe not big changes, but some small change that could mean that the person you meet is treated better. Or at least I hope so. If I didn’t believe people could change, I wouldn’t have become a teacher, because then it’s completely pointless. (Interview 1, Lotta)

Efforts to change colleagues’ mindset were included in the use of a change advocacy strategy. In their position as beginning teachers, the participants emphasised that they wanted to contribute to school development, and not only be passive recipients in a socialisation process.

Change advocacy strategies practised when starting to teach

When asked about emotionally challenging situations in school, beginning teachers commonly depicted starting to teach as being full of conflicts with colleagues, school leaders and pupils (Lindqvist et al., Citation2019). To overcome such challenges beginning teachers wanted to alter the origin of the challenges using change advocacy strategies. The strategies involved reforming teaching practices and attaining a position of competence. As we followed the participants from the end of teacher education into their first year as teachers, we noted that their ambiguity towards teachers was both challenged and confirmed. Being in conflict with colleagues added to the ambiguity but coming into contact with supportive teachers challenged the ambiguity instead.

Reforming teaching practice

Another area to change included the teaching practices of the schools and focused on colleagues’ teaching. Linn explained:

Linn: Experience is more valued in a way, in terms of who will be able to influence the school and the environment and stuff like that, and it’s valued more./ … /Well, you make suggestions, and I think it’s discussed, but it’s like: ‘Yes but no, not like that. We’ve never worked like that before and we’re not doing that.’ (Interview 2)

Linn had experienced the challenges of working for change. In trying to understand why the school operated the way it did, she experienced teachers’ change resistance. Lena, on the other hand, discussed how she felt she had a lot of ideas regarding changing teaching practice using ICT.

Absolutely, I often come to new places with a lot of ideas and thoughts about change. But sometimes I have to stop myself a little./ … /I enter the workplace and feel competent, and I’m not shy or humble. I dare to oppose something if it’s wrong, even though I’m young and new. That’s the way I experienced it. (Interview 2, Lena)

Lena described how change advocacy was sometimes met with resistance from other teachers. When starting to teach, Tuva encountered teaching that she thought of as pointless and wanted to change it: ‘So, a lot of work is going on, and I feel that my thoughts and views are appreciated. So, it’s changing, and I think it’s getting better’ (Interview 2, Tuva). To drive changes in the teaching practice the participants saw their newly attained position in different ways, both as a challenge and an opportunity to overcome challenges.

Attaining a position of competence

Some beginning teachers sought to be appointed to positions of competence, in line with what Kelchtermans and Ballet (Citation2002) described as attaining social recognition. For example, Hannes thought his teacher education meant that his competence was more up to date than that of his colleagues. Hannes thought that this should be recognised.

I have an opinion on how things should operate according to my education, and those who did their education who’re in their sixties have a totally different opinion. Not in a big way, but you might have some different opinions, especially, I would say, about pupils with special needs. I think we’ve had a lot more education about those issues than they did. That can generate situations where the older ones think we make it unrealistically easy for pupils. (Interview 2, Hannes)

Hannes thought he had competence, but the resistance he implied from senior colleagues exemplified the need for social recognition among colleagues. It also exemplified tensions among new and beginning teachers, also found in Lassila and colleagues’ (2018) study. Social recognition has been shown to be a key working condition for beginning teachers (Kelchtermans & Ballet, Citation2002; Sutton & Shouse, Citation2019), as discussed by Pia.

I feel that my colleagues trust my competence and that I have as many work tasks as any experienced teacher. For example, I’m responsible for a graduation show, purchases for the teaching team and ICT. I turned the last offer down because I already have a lot of responsibilities. (Self-report 3, Pia)

Pia described having extra tasks as a way of feeling valued, and this helped her in terms of seeking support from colleagues, and this might be a result of the inclusive efforts of high-status teachers. Sutton and Shouse (Citation2019) showed inclusive efforts of high-status teachers to be influential in order for the beginning teachers to receive social recognition.

A grounded theory of change advocacy

The participants thought that adopting a change advocacy strategy included a confrontation or a cognitive conflict (Lima, Citation2001). as the end result change advocacy strategy is confrontational. As shown in , among student teachers, two necessary social processes were involved in order to use a change advocacy strategy: (1) establishing teacher ambiguity and (2) challenging the perceived negative mindset. The analysis shows how the proposed change was thought of as important in order to challenge the teaching profession as a low status occupation in Sweden, and thus alleviate distress connected to feeling generally questioned for choosing a teaching profession. The participants understood the teaching profession as a low status profession from their own experiences and by their interactions with people who commented on their choice of profession in a negative way.

Beginning teachers who made use of a change advocacy strategy sometimes found themselves in conflict when trying to influence the practice of their school, which is corroborated by previous studies describing emotional challenges of beginning teachers connected to poor school climate and relationships with colleagues (Harmsen et al., Citation2018), as well as professional identity tensions and dilemmas (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013; Jokikokko et al., Citation2017; Pillen et al., Citation2013). The strategies involved with change advocacy were described as direct and confrontational and were seldom described as a subtle attempt to influence change and beginning teachers of the study encounter different expectations which may not align with their own values, also shown by Flores and Day (Citation2006). The grounded theory () shows the process of change advocacy strategy. A distinction of the model is that it exemplifies how the focus shifted from changing the micro-political setting of the whole school, into changing specific teachers. The participantsdescribed their change advocacy strategy as confrontational, and this is in line with what Lima (Citation2001) described as using a cognitive conflict to spark change.

The change advocacy strategy should not be considered to reflect an objectively better way of working at a school. One conclusion from the study is that the change advocacy strategy could be a valuable asset to a school organisation if it was paired with an understanding of the micro-political setting. This includes more than just informally changing teacher practice. For example, Tuva did set out to change practice, and Lena did find a way to hold workshops for colleagues regarding ICT. This could be the result of other high-status teachers initiating inclusive collaborative practices, similar to what Sutton and Shouse (Citation2019) described.

Discussion

When entering the school as a beginning teacher, teachers often have a lot of positive experiences, such as professional learning and mastering teaching skills (Voss et al., Citation2017), enjoyment (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013), positive relationships with students, and inspiring learning and teaching situations (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013). At the same time, beginning teachers may encounter emotionally challenging situations that interfere with their values, ideals and beliefs about good schools, teachers and teaching (e.g. Çakmak et al., Citation2019; Harmsen et al., Citation2018; Jokikokko et al., Citation2017; Pillen et al., Citation2013). Such challenges can, in turn, motivate them to engage in the direct-action strategy (Sharplin et al., Citation2011) of change advocacy (Lindqvist, Citation2019) as a way of dealing with their ‘reality shock’ (Caspersen & Raaen, Citation2014; Dicke et al., Citation2015) and maintaining their teacher ideals and standards. These efforts indicate that beginning teachers are not passive recipients but active agents in their teacher socialisation process at school.

However, beginning teachers rarely seem able to drive change at schools (Ulvik & Langørgen, Citation2012) due to the change resistance of the school culture (cf., Rubinson, Citation2002; Spratt et al., Citation2006; Thornberg, Citation2014) and their legitimacy loss. Thornberg (Citation2014) found that the professional collision between external consultants and teachers in school produced and reinforced self-serving social representations about ingroup and outgroup. Both teachers and consultants displayed ingroup favouritism and outgroup devaluation that protected their own ingroup and professional identity, very much in line with social identity theory (Hogg & Vaughan, Citation2018). These intergroup processes resulted in consultants’ legitimacy loss. Although beginning teachers are not outgroup members in relation to the teaching profession, as the external consultants in Thornberg’s (Citation2014) study are, they could be viewed as new members (‘rookies’ or novice teachers) rather than full members. There is evidence of arising conflicts when beginning teachers try to bring about change (Lindqvist et al., Citation2019).

If schools want motivated teachers, who work according to their best ability in different stages of their careers (cf. Day, Citation2019), they should avoid paternalistic practices in mentoring of student teachers and in the professional socialisation of beginning teachers. Implications from this study suggest that school leaders could acknowledge and let beginning teachers influence their school’s professional development in a more systematic way (also corroborated by Ulvik & Langørgen, Citation2012). They could be valued as assets. Change advocacy as a coping strategy could serve several purposes: (1) engaging beginning teachers in a school development project related to teaching to facilitate innovation (Lee, Citation2013); (2) overt use of avoidance strategies is problematic (Gustems-Carnicer & Calderón, Citation2012) and a direct-action strategy such as change advocacy should be encouraged at all stages of a teacher’s career to promote resilience and commitment to teaching; and (3) encouraging schools to leave the deficit-model of finding the beginning teachers to be lacking skills and instead embrace expertise from high-achievers in teacher education as active agents in promoting school development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henrik Lindqvist

Henrik Lindqvist, PhD, is senior lecturer at Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linkoping University in Sweden. His research areas are (1) student teachers learning from, and coping with, emotionally challenging situations in teacher education, and (2) special education.

Robert Thornberg

Robert Thornberg, PhD, is Professor of Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linkoping University in Sweden. His main focuses are on (a) bullying and peer victimization among children and adolescents in school settings, (b) values education, rules, and social interactions in everyday school life, and (c) student teachers and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training

Maria Weurlander

Maria Weurlander, PhD, is associate professor and senior lecturer in Higher Education at the Department of Education at Stockholm University in Sweden. Her main research focuses are on student learning in higher education, and student teachers’ and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training.

Annika Wernerson

Annika Wernerson, PhD, MD, is professor in renal- and transplantation science at the depart- ment of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology (CLINTEC) at Karolinska Institutet, where she also is Dean of higher education. Her research areas in medical education focus on learning in higher education and medical students’ and student teachers ́ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training and early professional life.

References

- Achinstein, B. (2002). Conflict amid community: The micropolitics of teacher collaboration. Teachers College Record, 104(3), 421–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9620.00168

- Aspfors, J., & Bondas, T. (2013). Caring about caring: Newly qualified teachers’ experiences of their relationships within the school community. Teachers and Teaching, 19(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.754158

- Ball, S. (1987). The micro-politics of the school: Towards a theory of school organisation. Methuen.

- Çakmak, M., Gündüz, M., & Emstad, A. B. (2019). Challenging moments of novice teachers: Survival strategies developed through experiences. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2018.1476465

- Caspersen, J., & Raaen, F. D. (2014). Novice teachers and how they cope. Teachers and Teaching, 20(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.848570

- Chaaban, Y., & Du, X. (2017). Novice teachers’ job satisfaction and coping strategies: overcoming contextual challenges at qatari government schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 340–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.07.002

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Day, C. (2019). Quality retention and resilience in the middle and later years of teaching. In B. Johnson, A. Sullivan, & M. Simons (Eds.), Attracting and keeping the best teachers (pp. 193–210). Singapore.

- Dicke, T., Elling, J., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2015). Reducing reality chock: The effects of classroom management skills training on beginning teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.01.013

- Flores, M., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

- Gustems-Carnicer, J., & Calderón, C. (2012). Coping strategies and psychological well-being among teacher education students. Coping and well-being in students. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(4), 1127–1140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0158-x

- Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., & Van Veen, K. (2018). The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 626–643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1465404

- Herman, K. C., Prewett, S. L., Eddy, C. L., Savala, A., & Reinke, W. M. (2020). Profiles of middle school teacher stress and coping. Concurrent and prospective correlates. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 54–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.003

- Hogg, M. A., & Vaughan, G. M. (2018). Social psychology (8th ed.). Harlow.

- Hyry-Beihammer, E., Jokikokki, K., & Uitto, M. (2019). Emotions involved in encountering classroom diversity: Beginning teachers’ stories. British Educational Research Journal, 45(6), 1124–1139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3554

- Johnson, B., Sullivan, A., & Simons, M. (2019). Teacher retention: Some concluding thoughts. In B. Johnson, A. Sullivan, & M. Simons (Eds.), Attracting and keeping the best teachers (pp. 211–220). Singapore.

- Jokikokko, K., Uitto, M., Deketelaere, A., & Estola, E. (2017). A beginning teacher in emotionally intensive micropolitical situations. International Journal of Educational Research, 81, 61–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.11.001

- Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: Self‐understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teachers and Teaching, 15(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875332

- Kelchtermans, G., & Ballet, K. (2002). Micropolitical literacy: Reconstructing a neglected dimension in teacher development. International Journal of Educational Research, 37(8), 755–767. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00069-7

- King, N., & Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in qualitative research. Sage.

- Lassila, E. T., Uitto, M., & Estola, E. (2018). You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t: The tension-filled relationships between Japanese beginning and senior teachers. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 26(3), 417–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2017.1412341

- Lazarus, S. R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer.

- Le Maistre, C., & Paré, A. (2010). Whatever it takes: How beginning teachers learn to survive. Teaching and teacher education, 26(3), 559–564.

- Lee, I. (2013). Becoming a writing teacher: Using ‘identity’ as an analytic lens to understand EFL writing teachers’ development. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2012.07.001

- Lima, J. A. (2001). Forgetting about friendship: Using conflict in teacher communities as a catalyst for school change. Journal of Educational Change, 2(2), 97–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017509325276

- Lindqvist, H. (2019). Student teachers’ use of strategies to cope with emotionally challenging situations in teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(5), 540–552. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2019.1674565

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2019). Conflicts viewed through the micro-political lens: Beginning teachers’ coping with emotionally challenging situations. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1633559.

- Löfgren, H., & Karlsson, M. (2016). Emotional aspects of teacher collegiality: A narrative approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 270–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.022

- McCormack, A. N. N., & Thomas, K. (2003). Is survival enough? Induction experiences of beginning teachers within a New South Wales context. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 31(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660301610

- OECD (2015). Improving schools in Sweden: An OECD perspective. OECD Punblishing. Retrived from http://www.oecd.org/education/school/improving- schools-in-sweden-an-oecd-perspective.htm (2019-02-23).

- Oplatka, I., & Iglan, D. (2020). The emotion of fear among schoolteachers: Sources and coping strategies. Educational Studies, 46(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2018.1536876

- Pillen, M., Beijaard, D., & Brok, P. D. (2013). Tensions in beginning teachers’ professional identity development, accompanying feelings and coping strategies. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 240–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.696192

- Pogere, E. F., López-Sangil, M. C., García-Señorán, M. M., & González, A. (2019). Teachers’ job stressors and coping strategies: Their structural relationships with emotional exhaustion and autonomy support. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 269–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.001

- Rubinson, F. (2002). Lessons learned from implementing problem-solving teams in urban high schools. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 13(3), 185–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532768XJEPC1303_03

- Sharplin, E., O’Neill, M., & Chapman, A. (2011). Coping strategies for adaptation to new teacher appointments: Intervention for retention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 136–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.010

- Spratt, J., Shucksmith, J., Philip, K., & Watson, C. (2006). Interprofessional support of mental well-being in schools: A Bourdieuan perspective. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 20(4), 391–402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820600845643

- Sutton, P. S., & Shouse, A. W. (2019). Investigating the role of social status in teacher collaborative groups. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(4), 347–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117751125

- Thornberg, R. (2012). Informed grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.581686

- Thornberg, R. (2014). Consultation barriers between teachers and external consultants: A grounded theory of change resistance in school consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 24(3), 183–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2013.846188

- Ulvik, M., & Langørgen, K. (2012). What can experienced teachers learn from newcomers? Newly qualified teachers as a resource in schools. Teachers and Teaching, 18(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.622553

- Voss, T., Wagner, W., Klusmann, U., Trautwein, U., & Kunter, M. (2017). Changers in beginning teachers’ classroom management knowledge and emotional exhaustion during the inductive phase. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 170–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.08.002