ABSTRACT

Mandatory Aboriginal education units of study in teacher education programmes are often constrained by overcrowded curriculum, time and classroom-based learning which limit opportunities to engage with and learn from local Aboriginal people and communities. Recognising these issues, at an urban Australian university two of the authors introduced ‘Learning from Country’ (LFC) cultural immersion experiences led by local Aboriginal community-based educators. These LFC experiences are now integral in several Aboriginal education electives. Emerging from these experiences, we developed an organic, iterative conceptual framework to articulate and make visible what LFC looks, feels and sounds like. In this paper we explain the LFC framework and discuss how it can be used to support preservice teachers to incorporate LFC principles into their professional practice and become part of their personal and professional identities in order to affect change in Aboriginal education in the schools and classrooms in which they will work.

Introduction

Australian teacher education programmes are now required to demonstrate that graduate teachers have developed strategies for teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students (AITSLFootnote1 standard 1.4) and understand and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to promote reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (AITSL standard 2.4). Key areas demanding attention are how schools may build relationships with Aboriginal people and Country,Footnote2 and how teachers can be prepared to, with insight and understanding, embed Aboriginal Knowledges and perspectives into the curriculum. This paper describes the Learning from Country (LFC) Framework, an approach that can be used to support preservice teachers to incorporate LFC principles into their professional practice and become part of their personal and professional identities.

Universities have implemented mandatory Aboriginal/Indigenous education units of study in their initial teacher education [ITE] programmes to meet accreditation requirements. These units are designed to address a history of objectifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, cultures and histories; a highly problematic curricular history often presenting essentialized versions of Aboriginal life and positioning Indigenous knowledges as inferior to Western knowledges (Moodie, Citation2019). This discursive deficit positioning of Aboriginal peoples, cultures and histories does little to prepare future teachers for embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Knowledges and perspectives into the curriculum and promoting reconciliation as required by AITSL and the Australian Curriculum (AC). If attempts at including Aboriginal content are tokenistic it may result in more harm, particularly for Aboriginal students who can become disengaged by simplistic and deficit discourses ‘about’ Aboriginal peoples and cultures. The significance of this issue and the impacts on Aboriginal students has been identified as has the need for substantive change in education (Bishop & Durksen, Citation2020). Recognising these issues, this paper reports our long-term teaching and action research to develop Learning from Country in pre-service teacher education. Specifically, we discuss the work by two of the authors who introduced Aboriginal community-led ‘Learning from Country’ cultural immersion experiences into Aboriginal education electives. As we report, LFC is now integral in several Aboriginal education electives at an urban-based Australian university.

An increasing number of research studies on teacher education programmes (c/f Burridge et al., Citation2012; Mackinlay & Barney, Citation2010; Moodie, Citation2019; Phillips, Citation2011) identify key constraints for effective implementation of Indigenous education in ITE such as inflexible timetabling, discipline silos, overcrowded curriculum, time pressures, and financial limitations. This often results in short ‘typical’ lecture/tutorial style teaching often taught by non-Aboriginal lecturers. This is counter-intuitive to holistic, ‘hands on’, pragmatic and contextually situated Indigenous teaching and learning approaches where knowing occurs through doing, and knowledges, understandings and skills are connected to the real world through an epistemology of relationality (Keddie, Citation2014). Moreover, many experienced Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers and lecturers note that non-Aboriginal university student responses to Aboriginal content can be highly emotional and range from resistance, shock, guilt, confusion and hesitation fuelled by poor knowledge and a lack of confidence (Bishop, Citation2020) and racism (Bodkin-Andrews & Carlson, Citation2014). When teachers lack the confidence and feel ill-equipped to teach Indigenous content they often avoid it (Moodie, Citation2019) contributing to the already inadequate and superficial approach to embedding Aboriginal content in the Australian curriculum (Lowe & Yunkaporta, Citation2013).

To productively mediate the epistemological and ontological dissonance students tend to experience in mandatory Indigenous education courses, we developed a framework whereby Aboriginal community-based educatorsFootnote3 take preservice teachers out of the classroom and onto Country to experience Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing (Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003). This framework enourages preservice teachers to reflect upon their personal and cultural positioning and critically analyse curriculum and pedagogy that excludes Aboriginal Knowledges and Country-base learning in favour of Western hegemonic approaches that assimilate, marginalise and disempower (Thorpe et al., Citation2021).

The aim of this paper is to describe and unpack this framework as it emerged organically in response to Aboriginal community-based educators, preservice teachers and teacher educator experiences of Learning from Country (LFC). The framework is purposefully open-ended, fluid and flexible in order to adapt to diverse contexts and various levels of education. As we will discuss, we have drawn on published conceptual work, primarily from Aboriginal Education contexts in Australia, to support our articulation of these experiences. We use the term ‘Aboriginal’ to represent First Nations Australians as this is the preferred term in our local Aboriginal community. It is also used in our state (province) in government policy, curriculum and curriculum content. We work closely with local Aboriginal community-based educators through yarning circles which support ongoing and iterative conversations and reflections on the conceptual and practical aspects of the project (Thorpe et al., Citation2021). Yarning in Aboriginal research contexts is a conversational, deep listening approach located in a culturally safe place and based on respectful relationships to understand self and others (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010). It is relational and dialogic, supporting knowledge sharing, cultural humility and reflexivity, and we purposely model these protocols and processes to preservice teachers.

We begin by providing an overview of the LFC teaching and research project, followed by a detailed explanation of the conceptual underpinnings of the framework as it emerged from our experiences and analysis of the literature. Through Yunkaporta and Shillingsworth’s (Citation2020) relationally responsive standpoint, we explore the axiological (values and ethics), ontological (understanding of reality), epistemological (how we know that reality) and methodological (how we enact that reality) processes of the framework. We then demonstrate how this framework makes visible the highly complex and nuanced relationships between each process to reflect the complex socio-cultural, historical, political and ecological dimensions of Country. We further indicate how these can be enacted in teaching and learning contexts.

Researcher positionality

All authors are researchers on the project and two are also lecturers in LFC-based courses. As an Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal team, we share a commitment to reshaping power relationships through privileging Aboriginal voices to affect Aboriginal student learning outcomes, curriculum and community engagement. We acknowledge that Aboriginal sovereignty has never been ceded and as we work on GadigalFootnote4 Country, we believe that this ‘place’ should be the focus of our efforts to reshape power relations. Author one is a non-Aboriginal educator with more than 35 years in Aboriginal education and parent of Aboriginal children involved in local community sports. Author two is a Worimi (Aboriginal) postdoctoral research fellow who has taught Indigenous Studies in teacher education for over two decades. Author three is a non-Aboriginal researcher who comes from a background working in community-based family, domestic and sexual violence organisations and is currently learning from interactions with Aboriginal community members and Country. Author four is a non-Aboriginal Woman born on Kaurna Country (Adelaide) who has been a university educator of sociology of education for two decades at undergraduate and postgraduate level. She collaborates with Aboriginal colleagues and in Aboriginal led research projects where she lives and works.

The paper is structured into three sections. We begin by describing the place we are located and the context of our LFC work in teacher education. In section two, we outline the development of the LFC framework, followed by a detailed description of each of the interconnecting processes: (i) Country-centred relationships; (ii) Relating; (iii) Critical Engagement; and (iv) Mobilising. Finally, we propose that nurturing an axiological standpoint is central to the principles of LFC, and discuss the practical and knowledge implications that emerge.

The context—Learning from Country in an Urban university

This project is situated on Gadigal Country, a site in Eastern Australia of initial British invasion. The place is an urban hub where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across the nation continue to meet, live and work to seek opportunities for employment, education, health and other services more readily available in the city. For some, impacted by the repercussions of invasion and settlement in regional, rural or remote places in Australia, Gadigal land provides a sense of place with Aboriginal community. As the university is located in this densely populated, built environment we also refer to this project as Learning from Country in the City.

While over time this urban community became internationally respected as a key site of resistance, protest, activism, advocacy and resilience, stereotypes that romanticise and exoticise ‘real Aborigines’(sic) as those who live a ‘traditional’ lifestyle in the ‘outback’ or the ‘bush’Footnote5 (Fredericks, Citation2013; Thorpe et al., Citation2021) continue to undermine Aboriginal voice and identity. The resulting stereotype that urban-based Aboriginal people have ‘no culture’, is often reinforced through the media “which has considerable influence on public attitudes and observations and are not the result of or personal contact with Aboriginal people” (Dudgeon et al., Citation2014, p. 259). These representations ignore significant and enduring relationships such as kin and Country connections often identified through family name, language groups and the town/s and places where family come from. As these characteristics in general are not visible to the broader non-Aboriginal community, Aboriginal people are wrongly assumed to be ‘assimilated’ into Western society. Further, Aboriginal peoples’ experiences of everyday racism coupled with continually defending their Aboriginality, are ignored or trivialised (Bodkin-Andrews & Carlson, Citation2014). Porter’s (Citation2018) point that Country is everywhere is critical,

… all places in Australia, whether urban or otherwise, are Indigenous places. Every inch of glass, steel, concrete and tarmac is dug into and bolted onto Country … because most of us live in towns and cities – we appear unable and unwilling to grasp that this urban country is also urban Country. (p. 239)

Aboriginal peoples’ relationship with Country is resolute. In keeping with this unwavering relationship of Aboriginal peoples to Country, LFC acknowledges that Aboriginal peoples, their histories and cultures are enduring throughout the lands, skies and waters of Australia.

The impetus for developing a LFC framework that centres Country through Aboriginal voices, arose in part from the student feedback and teacher observations of the limitations of mandatory Aboriginal education units in Initial Teacher Education courses. With the introduction of Aboriginal education electives which embed LFC experiences, an accompanying research project was designed to analyse the effects of this approach (Thorpe et al., Citation2021) and this work contributes important insights into this LFC framework. Furthermore, key research studies such as the NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group (AECG) Connecting to Country programme (Burgess & Cavanagh, Citation2016), an Aboriginal cultural mentoring programme for non-Aboriginal teachers (Burgess et al., Citation2020) and similar projects across Australia (cf Fogarty, Citation2010; Harrison et al., Citation2016; Jackson-Barrett & Lee-Hammond, Citation2018; McKnight, Citation2016a; Schwab & Fogarty, Citation2015; Yunkaporta & McGinty, Citation2009) highlight the powerful and transformative impact of Aboriginal community members running professional learning for preservice and local teachers on Country. Researchers agree that walking with and listening to EldersFootnote6 and local Aboriginal educators is central to learning about the relational connections with and, responsibilities towards Country. They also note that understanding this is critical for delivering curriculum and pedagogy in Aboriginal contexts.

LFC is a series of structured teaching and learning experiences embedded in three Aboriginal education courses that preservice teachers can elect after completing the mandatory course. Here, local Aboriginal community-based educators are employed to take preservice teachers onto Country to walk with and listen to Aboriginal peoples’ narratives of place. These experiences occur alongside classroom-based theory, discussion and critical thinking, which are structured in ways to develop deep listening, cultural humility, respectful dialogue, and reflexivity (Thorpe et al., Citation2021). Opportunities to listen to a diverse range of Aboriginal community members, Elders and organisations, moves preservice teachers beyond essentialised versions of Aboriginality and clarifies the importance of listening to many voices rather than one voice speaking for all (Welsh & Burgess, Citation2021). This then prompts students to critically analyse stereotypes about Aboriginal peoples and cultures commonly presented in the media (Dudgeon et al., Citation2014). The conceptual framework presented in this paper acknowledges the importance of diversity in Aboriginal communities including traditional knowledge holders, and those who come from neighbouring or distant Aboriginal nations who also have deep personal, familial and professional connections to the local Aboriginal community.

Consequently, the LFC framework will become the central principle in foundational units of a new Education Studies Major undertaken by all Initial Teacher Education students in 2022.

Developing the Learning from Country framework

In thinking about how to articulate and represent the processes and experiences of LFC, we turn to Aboriginal authors, Yunkaporta and Shillingsworth’s (Citation2020) relationally responsive standpoint to consider the LFC framework as a powerful decolonising tool that centres Indigenous ways of being, knowing and doing. Madden (Citation2015) notes that decolonisation has a range of definitions, however in teacher education contexts, we need to understand that decolonising pedagogies ‘(re)introduces teachers to Indigenous communities and knowledges through experiential storywork, … testimony, and revisionist histories of colonial productions that challenge stereotypical, appropriated, and/or censored (mis)representations’ (p. 9). By identifying metaphors for pedagogical processes, Yunkaporta and Shillingsworth outline an accessible, relatable and holistic framework that begins with respecting Aboriginal values, protocols and voice in contrast to Western processes that privilege an epistemological standpoint through a predetermined knowledge and research agenda. This suggests that inverting Western pedagogical processes by starting with respecting and valuing Indigenous processes, repositions power dynamics and centres Indigenous cultures, identities and communities in knowledge [re]production and practice. Yunkaporta and Shillingsworth (Citation2020, pp. 11–12) explain these processes, as follows,

1. The first step of Respect is aligned with values and protocols of introduction, setting rules and boundaries. This is the work of your spirit, your gut.

2. The second step, Connect, is about establishing strong relationships and routines of exchange that are equal for all involved. Your way of being is your way of relating, because all things only exist in relationship to other things. This is the work of your heart.

3. The third step, Reflect, is about thinking as part of the group and collectively establishing a shared body of knowledge to inform what you will do. This is the work of the head.

4. The final step, Direct, is about acting on that shared knowledge in ways that are negotiated by all. This is the work of the hands.

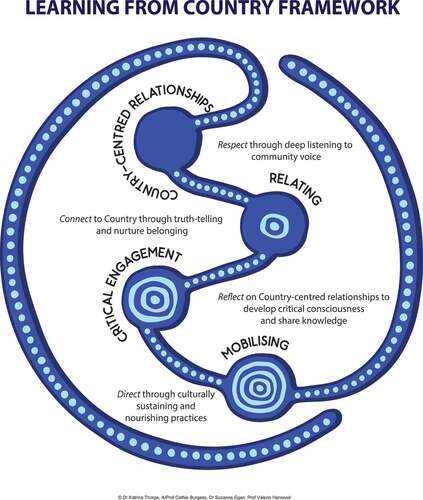

We visualise LFC in a similar way where the processes of learning are revealed by Country, and mobilised through relationship building via Country-centred relationships, relating, critical engagement and mobilising.

In describing the processes in , we acknowledge the non-linear, reflexive nature of Aboriginal Country-centred learning which links the past, present and future. Relationship-building through deep listening, respectful and reciprocal practices in a culturally safe place encourages understanding of self in relation to others and Country and contributes to emerging individual and collective narratives of place. The LFC Framework diagram depicts a metaphor of water, waterways are a life source that crisscross the Country in which our LFC experiences occur. As we explain (Burgess et al. Citation2022),

The dark blue acknowledges that Country is strong—it is ‘full’ of knowledge. The light blue circles represent the “activity” emanating and rippling throughout the Learning from Country processes which include deep listening to Aboriginal community voices and truth telling. There is a rippling of knowledge and relational connections that flow from one waterhole to the next. As each waterhole ripples with new knowledge and impacts on existing knowledge, it flows into the next waterhole. The connecting waterways between the waterholes represent the ebb and flow of knowledges and understandings that ripple through each waterhole … (p. 164)

These bodies of water are at times calm or choppy, rippling from the centre outwards, shifting everything in their path. Here the waterways remind us of the ebb and flow of the affective learning experiences (Harrison et al., Citation2017), and the growth and strengthening of relationships as we move through the processes of learning from Country.

The intersection and relationships between each of the processes is grounded in the notion of relationality, as depicted by Opaskwayak Cree scholar Shawn Wilson (Citation2001),

1. An Indigenous paradigm comes from the fundamental belief that knowledge is relational. Knowledge is shared with all creation.

2. It is not just interpersonal relationships, or just with the research subjects I may be working with, but it is a relationship with all of creation.

3. It is with the cosmos; it is with the animals, with the plants, with the earth that we share this knowledge.

4. It goes beyond the idea of individual knowledge to the concept of relational knowledge … [hence] you are answerable to all your relations when you are doing research. (p. 177)

The LFC framework combines three key practices; (i) connecting to and learning from Country, (ii) engaging with diverse Aboriginal experiences and views emerging from local cultures, identities, histories and communities and (iii) explicitly rejecting deficit discourses and challenging stereotypes, racism and the power structures that propagate these. Here we describe each of the four processes in the LFC Framework which facilitate these practices: (i) Country Centred Relationships; (ii) Relating; (iii) Critical Engagement; (iv) Mobilising.

Country-centred relationships

LFC begins with deep listening to and learning from Country, articulated through Aboriginal voices and community. This includes the individual and collective lived experiences of Country and Aboriginal people. This ethical stance positions and respects Country as teacher (McKnight, Citation2016a) and foregrounds accountability, reciprocity and obligation to Country and community. Respectful relationship building with Country is central to this endeavour and is the first key practice in activating this framework. We suggest the Western term ‘axiology’ can be harnessed to assist in emphasising and foregrounding the significance of ethical processes that are respectful to Country and people.

In Australia, Country is an Aboriginal EnglishFootnote7 word that describes land as a ‘living entity’ (Bird-Rose, Citation1996, p. 7), as Bird-Rose (Citation1996) suggests, Aboriginal ‘People talk about country in the same way that they would talk about a person’ (p. 7). Aboriginal academic Bronwyn Fredericks (Citation2013), suggests that the term Country refers to specific Aboriginal nations, including the ‘knowledge, cultural norms, values, stories and resources within that particular area—that particular Indigenous place’ (p. 6). Country et al. (Citation2015), extend this idea by noting the need to understand the world relationally as ‘more than human being’ (p. 470), highlighting the temporal connections between the diverse living ecologies of Country that consist of the human and non-human.

While we use the term Country in our Australian context, the notion of ‘place’ or place-based learning is more globally recognised where location is at the centre and relationships with local lands, ecologies and habitats are integral to culture, history and identity. As Ruitenberg’s (Citation2005) suggests, ‘each place has a history, often a contested history, of the people who inhabited it in past times’ (p. 215) and significantly, this involves ‘ … a spatial configuration through which power and other socio-politico-cultural mechanism are at play’ (p. 215). This was evident in the place where we carried out Learning from Country, a place in a large city, a place that is at once: thousands of years of continuous living history, Gadigal Country; invaded and with impacts of colonisation; and a place to which Aboriginal people impacted by colonisation and invasion have been drawn to (Norman, Citation2021).

Building relationships through a collective biography of place is described by Davies and Gannon (Citation2011, p. 139) as a pedagogical strategy where teachers and learners share and listen closely to each other’s stories in the process of developing a sense of community based on reciprocity, responsibility and support. This approach transforms the theory of place into practice, and can be a starting foundation for teachers to use place-based education as a way to inspire ‘inquiry and action. This brings together educators [and students] working for social justice and those working for ecological sustainability’ (Gruenewald & Smith, Citation2008, p. 339).

Community is a critical concept in understanding Indigenous relational connections to Country. Community relationships connect Aboriginal peoples to their Country, as community voices articulate and mobilise these connections in everyday knowledges and practice. Community emerged as a key element of the LFC framework and so engagement with local Aboriginal communities became central to theory and practice.

In Aboriginal contexts, the notion of ‘community’ transcends ‘normative’ understandings of the term and reflects bonds developed through intergenerational shared historical, cultural, social and political experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Welsh & Burgess, Citation2021). Aboriginal community structures around kinship, Country and identity as well as the economic, social and geographical diversity of each community have always been recognised by Aboriginal people and this knowledge about Aboriginal people has gained increasing recognition in ‘mainstream’ contemporary Australia. Nyungar researcher Ted Wilkes defines community as follows:

The Aboriginal community can be interpreted as geographical, social and political. It places Aboriginal people as part of, but different from, the rest of Australian society. Aboriginal people identify themselves with the idea of being part of ‘community’; it gives us a sense of unity and strength (as cited in Dudgeon et al., Citation2014, p. 6)

In urban centres, such as the location of this project, communities are dynamic, flexible and include political, work-related, cultural and sporting networks as well as family and Country networks. The latter two networks may be located elsewhere, often as a result of Aboriginal families moving from rural areas (or their Country) to urban centres to access employment, education and health services. Here, community membership involves individual and collective responsibilities and obligations such as active commitment to and support for others to become involved in community activities, to share skills and resources, and be accountable to each other for personal actions (Dudgeon et al., Citation2014, p. 258). Consequently, Aboriginal communities are sites of survivance, resistance, resilience and belonging (Dudgeon et al., Citation2014) each with common and nuanced complex and layered protocols that can be difficult for ‘outsiders’ to understand and navigate. Community voices therefore became central to the framework, providing a vehicle to articulate and build relationships with Country. The significance of Aboriginal voices in recognising Aboriginal self-determination and sovereignty and finally the role of listening to diverse Aboriginal voices for preservice teacher learning was critical in the LFC teaching and learning experiences.

The notion of Aboriginal ‘voice’ focuses on creating the conditions that illuminate Aboriginal-led Knowledges as LFC recognises the intellectual sovereignty of local Aboriginal knowledge holders, Aboriginal people control knowledge [re]production on their own terms in the places that have meaning to them and the communities they represent. The relationship between Country and voice creates space through which it is possible to decolonise Western knowledges, and highlight and mobilise the resilience of Aboriginal narratives and connection to Country. LFC involves decentring humans as knowledge holders to develop relational connections to Country through deep listening and reflection. This is not a simple or minor task, but one that requires patience, non-judgemental observation and deference leading to ‘relationships of care where mutual recognition and communicative engagement were also being performed’’ (Emmanouil, Citation2017, p. 90). Awabakal, Gumaroi, Yuin man Anthony McKnight (Citation2016b) notes that centring Country provides opportunities for Aboriginal Knowledge to be ‘observed, felt and understood on a spiritual level of connectedness’ (p. 2).

Voice on its own has less effect if it is not accompanied by deep, purposeful listening. This is not just about hearing. This form of listening facilitates an ontological response demanding cultural humility, open mindedness and critical personal positioning (Emmanouil, Citation2017). Dadirri is an example of a respected deep listening practice for working with and for Aboriginal peoples and communities. It is described by Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann Elder and member of the Ngangiwumirr language group (Healing Foundation, Citation2014, p. 7):

A special quality. A unique gift of the Aboriginal people is inner deep listening and quiet still awareness. Dadirri recognises the deep spring that is inside us. It is something like what you call contemplation. The contemplative way of Dadirri spreads over our whole life. It renews us and brings us peace. It makes us feel whole again.

Aboriginal researcher, Judy Atkinson (Citation2002) suggests that Dadirri is more a way of life which means ‘listening to and observing the self as well as, and in relationship with, others’ (p. 19). Listening, in this practice, therefore requires the development of reciprocal, honest and trusting relationships through ongoing reflexivity and commitment to the process.

Relating

‘Relating’ is the next process in the framework and makes visible the relational processes involved in engaging with diverse Aboriginal communities, experiences and knowledges of local cultures, identities and histories. Aboriginal-led truth telling is at the heart of this process, and central to this is listening to, understanding and respecting Aboriginal peoples lived experiences of colonisation, resistance, resilience and the continuity of living cultures. In the Australian context, the notion of truth telling gained traction with the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart (https:// ulurustatement.org/the-statement).Footnote8 This is seen as critical in recording evidence of Australia’s violent colonial past, enshrining First Nations voices in parliament, treaty making and sharing culture, heritage and history with the broader community. Aboriginal people posit that empowerment and healing can occur when their voices are heard and the truth of history is shared and recorded on their own terms (Johnston & Forrest, Citation2020). Truth telling processes in LFC also encourage preservice teachers to challenge settler colonial histories and embrace new ways of seeing, relating to and experiencing ‘living Country’ (Thorpe et al., Citation2021). In our research, we observed that building relationships within and between Country and all participants became key to a deeper understanding of the learning as it happened. By understanding the interconnectedness and relationality between various elements, a sense of belonging is created among knowers and learners. This ontological process is at the heart of being (Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, Citation2020, p. 2) and these intersubjective spaces determine how people understand their worldview and therefore influences their understanding of what exists and vice-versa (Hart, Citation2010, p. 7). The connection between truth telling and belonging is therefore about honouring and learning from diverse Aboriginal worldviews, requiring an ontological openness and shift in how we conceive ‘place’ in order to experience and be with ‘living Country’ (Emmanouil, Citation2017, p. 93).

Aboriginal-led truth telling is possible when values and ethics emanate from an Indigenous worldview, respect is embedded through deep listening, and connections develop into relationships. LFC encourages preservice teachers to reflect on their world view after truth telling experiences with Aboriginal community-based educators. The process also requires reciprocity in terms of listening and reflexivity to build the deferential relationships needed to connect to Country. Aboriginal-led truth telling reveals the significance of storying and lived experience which evokes a sense of unceded knowledge of Country for the speaker and the potential for transformation for preservice teacher conscientisation. Furthermore, these processes are critical to decolonising educational contexts. It is important to acknowledge however, that due to the often ‘difficult’ knowledges arising from Aboriginal community narratives of tragedy and trauma, a number of preservice teachers experience discomfort, even distress, as the realisation of the harmful impacts of settler colonial forces are laid bare. This can lead to challenges to their identity and self-understanding and a perceived sense of loss of agency as preservice teachers consider their complicity in these processes, and work through what they should and can do to the address this (Harrison et al., Citation2020). The LFC emphasis on relating assists students in their experience of such challenges, so that they are not immobilised. This can inspire a commitment to Aboriginal education and to challenging the institutional structures that perpetuate colonisation (Thorpe et al., Citation2021).

The centring of Aboriginal community-based educators’ stories to illuminate the complex socio-cultural, political and historical forces at play in local Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal community interrelationships is significant in developing for the preservice teachers their individual and collective critical consciousness (Freire, Citation1970/2000). LFC fosters preservice teacher empathy and connection, engendering a shared commitment to decolonising education, as Yunkaporta and Shillingsworth (Citation2020) say, ‘This is the work of your heart’ (p. 11).

Critical Engagement

For critical engagement and thinking throughout LFC experiences, conscientisation and knowledge sharing are intellectual processes that support the development of a shared and collective epistemology. Country-inspired ways of knowing and the co-production of knowledge facilitate new imaginings, expectations, responsibilities, and possibilities.

The intellectual processes of knowledge [re]production and reflecting (Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, Citation2020, p. 3) raises the question of what counts as knowledge and who decides. In LFC, the epistemological space between Country, Aboriginal voice and community focuses on knowledge from Country as a means by which to challenge and decolonise Western knowledge production. Indigenous epistemology is a subjectively based process where ‘the context is the self in connection with happenings, and the findings from such experiences is knowledge’ (Hart, Citation2010, p. 8). Here, cultural metaphors, diverse narratives and experiences provide a path towards new/or reimagined knowledges.

Conscientisation is recognised by a number of researchers, including Alim et al., Citation2020), Freire (Citation1970/2000) and Gay and Kirkland (Citation2003), as a key process for understanding and problematising dominant ideologies and henceforth employing liberatory educational approaches to achieve social justice. As Hart (Citation2010) suggests, ‘learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions—developing a critical awareness—so that individuals can take action against the oppressive elements of reality’ (p. 35), reflects the third key practice of this framework, to explicitly reject deficit discourses and challenge the stereotypes, racism and the power structures that propagate these.

Deep and respectful listening to truth telling from Aboriginal community voices provides purposeful experiences for preservice teachers to activate critical thinking and engage with counternarratives to Western versions of settlement and progress (Burgess et al., Citation2020). These counternarratives challenge preservice teachers to reflect on their own social and cultural positioning and consider how these impacts on what and how they teach. Ongoing reflection is embedded in the place-based pedagogies employed, and so provide ‘a dynamic and reflexive approach to reading the world (text, media, audio, interactions) that strengthens one’s understanding of power, inequity, and injustice’ (Kohli et al., Citation2019, p. 25). Through cycles of action, reflection, theorising and change, (Arnold et al., Citation2012, p. 282) preservice teachers build their capacity for contemplation and a critical cultural consciousness (Gay & Kirkland, Citation2003).

In this context, the generosity of the Aboriginal community based educators in sharing their knowledge is critical to the process of working towards epistemic equity. As dominant Western knowledges are challenged for their central role in oppressing Aboriginal voices, Indigenous world views are made visible through a relationally responsive standpoint (Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, Citation2020) and become central and critical to knowledge sources for decolonising education.

Mobilising

The fourth process in the LFC framework enacts Country-inspired ways of valuing, being, and knowing. Through respecting, connecting and reflecting on Country-led learning in genuine and reciprocal relationships, the ‘doing’ can emerge. Here, as Country becomes visible, truth telling, belonging and knowledge-sharing occur, and culturally sustainable teaching and learning can evolve.

Culturally sustaining pedagogy has its roots in culturally responsive pedagogy which is well-recognised internationally (cf Alim et al., Citation2020; Ladson-Billings, Citation1995) as ground-breaking research that focuses on the cultures of ‘students of colour’ as assets for learning and the importance of challenging dominant power structures. However, in the Australian context, Morrison et al. (Citation2019) note that a limitation of culturally responsive education is its failure to acknowledge or account for Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty. Further Alim et al. (Citation2020) note that the culturally responsive pedagogy project has often fallen short of its original intent due to being co-opted by Whiteness. Recognition of the cultural and linguistic strengths and skills of ‘students of colour’ remain superficial, through assuming Whiteness as the default cultural norm.

Alim et al.’s (Citation2020) culturally sustaining pedagogical approach reinforces the centring of communities and voice in learning as dynamic, evolving and empowered. They further emphasise that these pedagogical practices must foster and sustain Indigenous identities, cultures, languages and histories, and as the LFC framework aims to do, create intersubjective ontological spaces for truth telling and Country-inspired narratives. We suggest that in the Australian context, a culturally sustaining pedagogical approach must acknowledge sovereignty and foreground Country-centred relationships. Explicitly naming Whiteness as a key source of structural oppression (Moreton-Robinson, Citation2004) is also key to culturally sustaining pedagogies where critical engagement through reflection, knowledge sharing and truth telling is essential for individual and collective conscientisation. Through the framework’s three relational processes of Country-centred relationships, relating and critical engagement, culturally sustaining practices are mobilised to decolonise education such that belonging, relationality and collaboration become the organising structures upon which to build a liberatory education system.

Concluding comments—The importance of nurturing an axiological standpoint

The LFC framework articulates a pedagogical approach that consists of purposeful, structured experiences for preservice teachers to learn first-hand from local Aboriginal community-based educators which generate understanding of ongoing activism, survival and resilience. These Country-centred experiences shape the significance of place-based learning as revealing and poignant as well as confronting in contesting Western versions of settlement and progress (Burgess et al., Citation2020). Here, preservice teachers’ ways of thinking about past and present relationships between Aboriginal peoples, lands, cultures, histories and communities as well as relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples, facilitates the development of their critical cultural consciousness (Gay & Kirkland, Citation2003).

This framework emerges from iterative, dialogic and relational experiences and practices in Aboriginal education university courses where learning from Aboriginal voices and Country is foundation and central to decolonising curriculum and mobilising relationally responsive and culturally sustaining pedagogies. Country-centred relationships enable preservice teachers to begin their journey from an axiological standpoint where relationally responsive practices focus on ethical processes. For educators, this means that understanding and engaging with local Aboriginal community values and protocols through deep listening, respect and reciprocity is critical in the LFC journey and so must be modelled to students as a lifelong learning process. The practical and knowledge implications of this standpoint is that ‘hands on’, pragmatic and contextually situated Country-based teaching and learning happens where knowing occurs through doing and an epistemology of relationality connects knowledges, understandings and skills to the real world (Keddie, Citation2014). The generosity, skill and knowledges of the Aboriginal community-based educators enables preservice teachers to experience an Indigenous onto-epistemological approach as ‘a fluid way of knowing derived from teachings transmitted from generation to generation by storytelling, where each story is alive with the storyteller’ (Hart, Citation2010, p. 8). It is an embodied way of knowing which requires an ontological openness developed through deep listening and contemplation to grapple with diverse world views (Emmanouil, Citation2017, p. 93).

Critical engagement with notions of Whiteness and the impact of power dynamics inherent in institutional structures along with the ongoing epistemic violence of assimilatory schooling practices on Aboriginal cultures and identities must occur for Country-inspired teaching and learning to benefit preservice teachers. If these oppressive structures and practices are not challenged, tokenism and Aboriginal people’s experiences of alienation within the education system will be reproduced (Bishop & Durksen, Citation2020) as teachers seek complacent comfort in what they know and can control. Mobilising culturally sustaining practices challenges this position as Whiteness is named and Aboriginal sovereign voices are centred.

Significantly, this is complex, contextual and nuanced work that does not happen neatly in linear, isolated or even logical ways. The processes —Country-centred relationships, relating, critical engagement and mobilising—are a relational, holistic and an intricate weaving together of ethical, relational, intellectual and operational processes (Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, Citation2020). It is dynamic, evolving and responsive to individual and collective dispositions and lived experiences. It cannot be done without respecting, valuing and centring local Aboriginal voices and Country and therefore requires a shifting of the power balance from the academy to the community. Relationship building weaves these processes together. That is, relationship building is a many faceted: it is an aim; a process; and an ongoing learning journey providing consistency, engagement, and purpose. Importantly, it keeps us grounded in the processes, cognisant of the importance of generosity, reciprocity, and integrity. This brings much needed spirit and heart to knowing and doing, reminding us of what is important and why.

Finally, this framework is not a one-size-fits-all approach or the ‘answer’ to improving Aboriginal education or Aboriginal student outcomes. What it does set out to do is to contribute to the effort in Australian universities to improve preservice teacher education through Country-centred learning processes. We see this as a contribution where preservice teachers are supported to firstly, learn from Country during their initial teacher education, and secondly, to learn how to incorporate LFC principles into their pedagogical practices and into personal and professional identities. We propose that by making a positive impact on teacher personal and professional identities, LFC has the potential to affect change in Aboriginal education in the schools and classrooms in which they will work. In this way the LFC framework is an inclusive and empowering way in which to contribute to decolonising education, as Yunkaporta and Shillingsworth (Citation2020, p. 9) say, a way to ‘walk your talk’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cathie Burgess

Associate Professor Cathie Burgess coordinates and teaches undergraduate and postgraduate Aboriginal Studies, Aboriginal Community Engagement, Learning from Country and Leadership in Aboriginal Education courses in the Sydney School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney. Her research involves community-led initiatives centring Aboriginal voices and positioning Aboriginal community-based educators as leaders through projects such as Learning from Country in the City, Culturally Nourishing Schooling Project, and Sparking Imagination Education: Transforming Inequality in Schools.

Katrina Thorpe

Dr Katrina Thorpe (Worimi) is the inaugural Chancellors Postdoctoral Indigenous Research Fellow at the Centre for the Advancement of Indigenous Knowledges, University of Technology Sydney. Katrina has 25 years experience teaching mandatory Indigenous Studies to diverse student cohorts within the fields of education, social work, nursing, health and community development. Drawing on these diverse teaching experiences, Katrina’s research has engages the voices of pre-service teachers, Aboriginal community members and teacher educators to provide nuanced understandings of the experiences that support or inhibit student learning and development of a personal and professional commitment to Indigenous education.

Suzanne Egan

Suzanne Egan currently works in the School of Social Sciences, Western Sydney University Australia

Valerie Harwood

Valerie Harwood is a Professor of Sociology and Anthropology of Education in the Sydney School of Education and Social Work, The University of Sydney. Valerie’s research is centred on a social and cultural analysis of participation in educational futures. This work involves learning about collaborative approaches and in-depth fieldwork on educational justice with young people, families and communities.

Notes

1. AITSL Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership is the accrediting body and the name of the document is the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers.

2. Country is an Aboriginal English term that describes the relational connections Aboriginal people have with land, seas and the skies. Country is considered a holder of knowledge and the essence of Aboriginality.

3. After much discussion, the Aboriginal community members preferred to be referenced as Aboriginal community-based educators, rather than knowledge holders, Elders or cultural educators as an ethical accountability to their community. For further discussion please see,Thorpe et al. (Citation2021).

4. Gadigal is the Aboriginal word for our local area where LFC occurs

5. ‘Outback’ and ‘bush’ are colloquial Australian terms to describe rural and remote areas often enlisting stereotypes such as where ‘real’ Aboriginal people and culture can be ‘found’.

6. We do not offer a singular definition of Elder, rather we acknowledge that Aboriginal communities will have their own processes and practices for defining what Elder means. Generally, an Elder could be understood to be a respected senior Aboriginal person recognised for their cultural knowledge.

7. Aboriginal English is a dialect from of Australian English and words may differ in meaning to Standard Australian English.

8. The Uluru Statement from the Heart is a historic statement by Australian First Nations peoples calling for a First Nations voice to parliament to be enshrined in the constitution and for a Makarrata Commission to supervise Treaty processes and Truth-telling.

References

- Alim, H. S., Paris, D., & Wong, C. (2020). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A critical framework for centering communities. In N. Nasir, C. Lee, R. Pea, & M. McKinney de Royston (Eds.), Handbook of the cultural foundations of learning (pp. 261–276)). Routledge.

- Arnold, J., Edwards, T., Hooley, N., & Williams, J. (2012). Conceptualising teacher education and research as ‘critical praxis’. Critical Studies in Education, 53(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2012.703140

- Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails recreating song lines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Melbourne: Spinifex Press.

- Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

- Bird-Rose. (1996) . Nourishing terrains: Australian aboriginal views of landscape and wilderness. Australian Heritage Commission.

- Bishop, M. (2020). “I spoke about Dreamtime - I ticked a box”: Teachers say they lack confidence to teach indigenous perspectives. Science Education News, 69(2), 73–74. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.587497602397498.

- Bishop, M., & Durksen, T. (2020). What are the personal attributes a teacher needs to engage Indigenous students effectively in the learning process? Re-viewing the literature. Educational Research, 62(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1755334

- Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Carlson, B. (2014). The legacy of racism and indigenous Australian identity within education. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 19(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.969224. .

- Burgess, C., Bishop, M., & Lowe, K. (2020). Decolonising indigenous education. The case for cultural mentoring in supporting Indigenous knowledge reproduction. Discourse: The Cultural Politics of Education, 43(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1774513.

- Burgess, C., & Cavanagh, P. (2016). Cultural immersion: developing a community of practice of teachers and aboriginal community members. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 45(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2015.33

- Burgess, C., Thorpe, K., Egan, S., & Harwood, V. (2022). Developing an Aboriginal Curriculum Narrative. Curriculum Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-022-00164-w.

- Burridge, N., Chodkiewicz, A., & Whalan, F. (2012). A study of action learning and Aboriginal cultural education. In N. Burridge, F. Whalan, & K. Vaughn (Eds.), Indigenous education: A learning journey for teachers, schools and communities (pp. 33–46). Sense.

- Country, B., Wright, S., Suchet-Pearson, S., Lloyd, K., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr-Stubbs, M., Ganambarr, B., & Maymuru, D. (2015). Working with and learning from Country: Decentring human authority. Cultural Geographies, 22(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014539248

- Davies, B., & Gannon, S. (2011). Collective biography as a pedagogical practice: Being and becoming in relation to place. In M. Somerville, B. Davies, K. Power, S. Gannon, & P. de Carteret (Eds.), Place pedagogy change (pp. 129–142). Sense Publishers.

- Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., & Walker, R. (2014). Working together: Aboriginal and torres strait islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Emmanouil, N. (2017). Ontological openness on the Lurujarri dreaming trail: A methodology for decolonising research. Learning Communities, 22, 82–97. https://doi.org/10.18793/LCJ2017.22.08. Special Issue: Decolonising Research Practices.

- Fogarty, W. (2010). Learning through Country: Competing knowledge systems and place-based pedagogy. Unpublished thesis, The Australian National University

- Fredericks, B. (2013). We don’t leave our identities at the city limits’: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in urban localities. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2013(1), 4–16. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/219606/.

- Freire, P. (19702000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th Anniversary) ed.). Continuum International.

- Gay, G., & Kirkland, K. (2003). Developing cultural critical consciousness and self-reflection in preservice teacher education. Theory into Practice, 42(3), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4203_3

- Gruenewald, D., & Smith, G. (Eds.). (2008). Place-based education in the global age: Local diversity. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Harrison, N., Bodkin, F., Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Mackinlay, E. (2017). Sensational pedagogies: Learning to be affected by country. Curriculum Inquiry, 47(5), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2017.1399257

- Harrison, N., Burke, J., & Clarke, I. (2020). Risky teaching: Developing a trauma-informed pedagogy for higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1786046

- Harrison, N., Page, S., & Tobin, L. (2016). Art has a place: Country as teacher in the city. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(13), 1321–1335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1111128

- Hart, M. (2010). Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: The development of an indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work, 1(1), 1–16. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/15117.

- Healing Foundation. (2014) . A Resource for Collective Healing for Members of the Stolen Generations. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation.

- Jackson-Barrett, E. M., & Lee-Hammond, L. (2018). Strengthening identities and involvement of aboriginal children through learning on country. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(6), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n6.6

- Johnston, M., & Forrest, S. (2020). Working two way: Stories of cross-Cultural collaboration from Nyoongar Country. Springer.

- Keddie, A. (2014). Indigenous representation and alternative schooling: Prioritising an epistemology of relationality. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.756949

- Kohli, R., Lin, Y., Ha, N., Jose, A., & Shini, C. (2019). A way of being: Women of color educators and their ongoing commitments to critical consciousness. Teaching and Teacher Education, 82(6), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.005

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

- Lowe, K., & Yunkaporta, T. (2013). The inclusion of aboriginal and torres strait Islander content in the Australian national curriculum: A cultural, cognitive and socio-political evaluation. Curriculum Perspectives, 33(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.223560.

- Mackinlay, E., & Barney, K. (2010). Transformative learning in first year indigenous Australian studies: Posing problems, asking questions and achieving change. A practice report. International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 1(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v1i1.27

- Madden, B. (2015). Pedagogical pathways for Indigenous education with/in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.005

- Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist re‐search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838.

- McKnight, A. (2016a). Preservice teachers’ learning with Yuin Country: Becoming respectful teachers in Aboriginal education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(2), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2015.1066491

- McKnight, A. (2016b). Meeting country and self to initiate an embodiment of knowledge: Embedding a process for aboriginal perspectives. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, FirstView, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2016.10

- Moodie, N. (2019). Learning about knowledge: Threshold concepts for Indigenous studies in education. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(5), 749–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00309-3

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen (Ed.) (2004). Whitening Race: Essays in social and cultural criticism in Australia.Aboriginal Studies Press, Australia, Canberra.

- Morrison, A., Rigney, L.-I., Hattam, R., & Diplock, A. (2019). Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-08/apo-nid262951.pdf

- Norman, H. (2021). Aboriginal Redfern “then and now”: Between the symbolic and the real. In. S. Huebner (Ed). Archiving First Nations media: the race to save community media and cultural collections. Australian Aboriginal Studies. pp. 22–35.

- Phillips, D. (2011). Resisting Contradictions: non-Indigenous pre-service teacher responses to critical Indigenous studies. (Doctoral Thesis). Queensland University of Technology.

- Porter, L. (2018). From an urban country to urban Country: Confronting the cult of denial in Australian cities. Australian Geographer, 49(2), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2018.1456301

- Ruitenberg, C. (2005). Deconstructing the experience of the local: Toward a radical pedagogy of place. In K. Howe (Ed.), Philosophy of education (pp. 212–220). Philosophy Education Society.

- Schwab, R., & Fogarty, B. (2015). Land, learning and identity: Toward a deeper understanding of Indigenous learning on country. UNESCO Observatory Multi-Disciplinary Journal in the Arts, 4(2), 2–16.

- Thorpe, K., Burgess, C., & Egan, S. (2021). Learning from country in the City: Innovative teacher education in practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.202v46n1.4

- Uluru Statement of the Heart. (2017). https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement

- Welsh, J., & Burgess, C. (2021). Trepidation, trust and time. Research with aboriginal communities. In J. Flexner, V. Rawlings, & L. Riley (Eds.), Community-Led research: Walking many paths together (pp. 147–168). Sydney University Press.

- Wilson, S. (2001). What is Indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 175–179. https://www.proquest.com/docview/230307399.

- Yunkaporta, T., & McGinty, S. (2009). Reclaiming Aboriginal knowledge at the cultural interface. Australian Educational Researcher, 36(2), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216899

- Yunkaporta, T., & Shillingsworth, D. (2020). Relationally responsive standpoint. Journal of Indigenous Research, 8(4). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/4